TRAVEL and travel texts have a habit of surfacing everywhere in early modern English writing. Take Euphues and his England (1580), John Lyly’s sequel to his trend-setting Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578), for instance. As the bright and often annoyingly self-satisfied Athenian hero of Lyly’s fiction sails towards his destination, he does all that a conscientious traveller could be expected to do. Euphues spends his time reading an account of Britain, plans to write a report of his own observations, and bores his companion with his lengthy discourse. But his long-suffering friend, Philautus, is hardly grateful for the lecture:

Philautus, not accustomed to these narrow seas, was more ready to tell what wood the ship was made of than to answer to Euphues’ discourse; yet, between waking and winking as, one half sicke and somewhat sleepy, it came in his brains, answered thus:

‘In faith, Euphues, thou hast told a long tale. The beginning I have forgotten, the middle I understand not, and the end hangeth not together. Therefore I cannot repeat it as I would, nor delight in it as I ought; yet if at our arrival thou wilt renew thy tale, I will rub my memory. In the mean season, would I were either again in Italy, or now in England. I cannot brook these Seas, which provoke my stomach sore.’1

Lyly’s quiet joke here is obviously at the expense of Euphues, the seasoned humanist scholar and traveller. The information that he has gleaned so studiously from Caesar’s Gallic Wars, although not quite the outright lies as travellers’ tales were generally reputed to be, is useless for visitors to Elizabethan England. And if the knowledge associated with the reading of travel is in question, the experience of it hardly fares any better. From Jerome Turler’s Traveiler (1575) to Francis Bacon’s essay ‘Of Travel’ (1612, 1625), the enormous body of travel advice literature that flourished throughout this period might praise the benefits of travel for the individual as well as the state, but Philautus fails to offer a convincing illustration of either. Seasick and sleep-deprived, it is obvious that he likes everything about travel apart from the travelling itself. At the end of Lyly’s story he will refuse to follow the example of Odysseus and return home with the fruits of his experience like all good travellers were advised to do, happily choosing to settle abroad instead.

That travel finds its way into Lyly’s prose fiction is not surprising in itself. Travelling and lying went together in popular perception, and travellers’ tales were traditionally associated as much with the writing of fiction as with the narratives of facts in history and geography. What is notable here, however, is the way in which Lyly’s fiction plays with the disjunction between the experience of travel and the reading of it, and how that encounter with contemporary travel brings with it something that is quite different from the glamour that surrounds a knight’s quest or a pilgrim’s progress. In its attention to the details of the experience of travel, its emphasis on the gathering of heterogeneous data that threaten to slip out of the grasps of Euphues and Philautus even as they are presented, it introduces something of the everyday and the prosaic, which marks a change both in English fiction and in Lyly’s characteristic and instantly recognizable, highly fraught rhetorical style. That moment in Euphues and his England offers us an unexpected way into the actual writing of travel in England in the period and into the book that forms the subject of this chapter, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, compiled a decade after Lyly’s Euphues by his fellow Oxford scholar, Richard Hakluyt.2

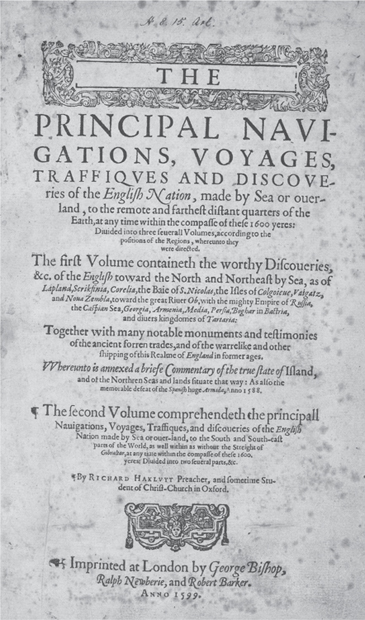

Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations is the single most significant collection of travel literature ever to be published in English. First printed in 1589, and running to over 1,760,000 words in three folio volumes by the time the second edition is printed in 1598–1600 (Fig. 18.1), it is also one of our largest collections of Renaissance English prose, intimately connected with both its predecessors and successors in the field of travel writing. Admittedly, readers may often find themselves sharing Philautus’s confused exhaustion when faced with the seemingly endless assembly of texts in Hakluyt’s collection, and those who laugh at Euphues’s antiquated travel information may be puzzled equally by the space that Hakluyt affords to ancient documents. At a more fundamental level, however, the understanding of the epistemic gap between the reading and practice of travel that lies at the heart of Lyly’s joke also shapes Hakluyt’s massive text. The writing of travel, of all the genres of narrative writing in the early modern period, was one of the most problematic when it came to the relationship between theory and practice, text and action. Why does one go about capturing the experience of travel through words, and how? If Philip Sidney, in his Defence of Poetry, had claimed that ‘it is not gnosis but praxis must be the fruit’ of literature, rhetorically moving the reader from ‘well-knowing’ to ‘well-doing’, then what was the status of travel writing, where the novelty and the messiness of the experience of travel demanded written order and therefore invited widespread scepticism about their truth-content, where text constantly threatened to substitute for action, and action undermined the text’s efforts to record its essential nature with any degree of accuracy?3 Hakluyt’s attempts to tackle those questions in The Principal Navigations would have significant implications both for English travel writing and for English prose itself.

FIGURE 18.1 Richard Hakluyt, Principal Navigations (1599), title page.

For Hakluyt, the answer to the initial ‘why’—the rationale for capturing the praxis of travel through words in the first place—is clear. His contribution came in an age when travel and exploration was rapidly changing the visible world, but English participation in that process was belated and disorganized. Italian-born John Cabot, authorized to venture on behalf of the English king Henry VII, had reached Newfoundland in 1498, and there had been other scattered attempts since then. Voyages in search of a north-east passage to China had opened up trade with Russia; others ventured west towards Brazil and the Caribbean, as well as Africa and the Middle East. By the 1580s, England was catching up with countries like Spain and Portugal, thanks to the efforts of people like John Hawkins, Martin Frobisher, Humphrey Gilbert, Francis Drake, and Walter Ralegh. Yet, compared to the explorations and voyages undertaken by their continental rivals, these were unsystematic initiatives, underwritten mostly by individuals or groups of merchants, rather than the product of any concerted English imperial effort. When Hakluyt came to print his very first collection of travel texts, Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America (1582), and addressed his dedicatory epistle to Philip Sidney, this is the first thing he mentions. Rather than beginning with the marvels of the New World, as one might have expected him to do, ‘I marvaile not a little’, he writes, ‘that since the first discoverie of America (which is nowe full fourescore and tenne yeeres) after so great conquests and plantings of the Spaniards and Portingales there, that wee of England could never have the grace to set fast footing in such fertile and temperate places, as are left as yet unpossessed of them’ (sig. ¶r). When The Principal Navigations is printed in the general wave of English optimism after the defeat of the Spanish Armada seven years later, therefore, his focus on the recording of English travels is both an exhortation and a defence. This time the dedicatory letter to Sidney’s father-in-law and Elizabeth I’s Principal Secretary, Sir Francis Walsingham, notes how Hakluyt has ‘both heard in speech, and read in books other nations miraculously extolled for their discoveries and notable enterprises by sea, but the English of all others for their sluggish security, and continuall neglect of the like attempts [ … ] either ignominiously reported, or exceedingly condemned’.4 His response to this ‘obloquie of our nation’ is to ‘speake a word of that just commendation which our nation doe indeed deserve’. ‘[I]t can not be denied,’ he asserts:

but as in all former ages, they have been men full of activity, stirrers abroad, and searchers of the remote parts of the world, so in this most famous and peerlesse governement of her most excellent Majesty, her subjects through the speciall assistance, and blessing of God, in searching the most opposite corners and quarters of the world, and to speake plainly, in compassing the vaste globe of the earth more th[a]n once, have excelled all the nations and people of the earth. (PN1, sig. *2v)

By the time Hakluyt published the massively expanded second edition of The Principal Navigations in 1598–1600, thanks to his editorial enterprise, that claim would be fairly impossible to deny. When the Victorian historian James A. Froude famously called The Principal Navigations ‘the prose epic of the modern English Nation’, it was the pioneering status of this strong nationalistic impetus which his description acknowledged. In subsequent years, Hakluyt’s nationalism and the role of The Principal Navigations in the construction of the idea of English nationhood have never been in doubt; indeed, they have become the implicit focus of our questioning of Hakluyt’s complicity in English projects of colonialism and imperialism.5

Over and above that nationalistic drive which provides its rationale, however, the significance of The Principal Navigations rests in its response to its second challenge: the ‘how’ beyond the ‘why’. How can a text bridge the gap between the experience and the representation of travel? How does it convince its readers that what they read offers an accurate representation of the experience itself? And what happens to both words and texts in the process? Hakluyt would have known how his predecessors had approached this task. There were those, for instance, whom The Principal Navigations describes disparagingly as the makers of ‘wearie volumes bearing the titles of universall Cosmographie’ (PN1, sig. *3v). Johann Boemus, whose Omnium gentium mores (1520) attempted to provide an all-encompassing account of the cultures of Asia, Africa, and Europe, and was translated in part into English as a Fardle of Facions in 1555, would count as one of them. More recently, Sebastian Münster’s Universal Cosmography had been published in German in 1544 and Latin in 1550, as well as being translated and adapted in countless versions, including in English in 1561 and 1572. And even as Hakluyt was collecting his own material, a so-called ‘guerre des cosmographes’ had broken out between André Thevet and François de Belleforest, when both published their own volumes of Cosmographie universelle in Paris in 1575.6 Encyclopaedic in scope and heavily influenced by the classical examples of Ptolemy’s Geography and Pliny’s Natural History, the focus of the texts produced by writers such as Boemus and Münster was on comprehensiveness. Their descriptions rarely distinguish between ancient and modern authorities, using both instead to synthesize a global model centred on Christian doctrine. That structure is crucial: the time-bound individual voice of contemporary travellers, bringing in new facts and data that so often defy the existing framework, is subsumed within its boundaries.

For Hakluyt, as for the immediate predecessors with whom his links are the closest, such historiographic recastings of the world could never offer an accurate representation of either the gnosis or praxis of travel. The alternative that he offers, namely that the recording of contemporary history of travel (peregrinationis historia) was the only true means to ‘certayne and full discoverie of the world’ (PN1, sig. *3v), has its roots in the existing European travel collections of Francanzano da Montalboddo and Giovanni Battista Ramusio. Hakluyt makes multiple references on several occasions to Ramusio’s immense three-volume collection of travel accounts, Delle Navigationi et viaggi (1550–9), for instance, and would later dedicate his own 1587 Latin edition of Peter Martyr d’Anghiera’s De Orbe Novo Decades (Alcála, 1516) to Sir Walter Ralegh, in the hope that ‘other maritime races, and in particular our own island race, perceiving how the Spaniards began and how they progressed, might be inspired to a like emulation of courage’.7 Among the English, Hakluyt mentions Richard Eden, whose Decades of the New World (1555) consists of translated excerpts and summaries of the travel accounts of a number of continental writers, from Münster to Ramusio, Peter Martyr, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, and Antonio Pigafetta. Along with its much-expanded adaptation by Richard Willes in his A History of Travayle in the West and East Indies (1577), Eden’s text was the closest predecessor to Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations, although Hakluyt’s emphasis on English voyages would give the latter a distinctive edge over its competitors. Irrespective of their national focus, however, collections of peregrinationis historia of this kind depended far more on first-hand accounts (although often through translation and summary), rather than the second-hand redactions of the old cosmographies. More responsive to the rapid expansion of geographical knowledge and alterations in political climate, their form was cumulative and changeable. It was possible for Peter Martyr, for example, to add new reports as the Decades were published in multiple editions, as Michael Brennan has shown, while Eden and Hakluyt would both reinterpret its representation of Spanish imperialism in very different ways when preparing their own editions of the Decades in the reigns of Mary Tudor and Elizabeth I respectively.8

Hakluyt’s third group of predecessors were even more sensitive to the demands of time and more clearly aligned with contemporary travel experience. These were the individual travel texts, accounts of recent travels by voyagers and explorers, the eyewitness reports. Their motives and quality of writing are variable, and their writers cover the entire range that William Sherman has identified in his typology of travel writers in this period, from pilgrims, knights, merchants, explorers, and colonizers, to diplomatic and political travellers, captives and castaways, pirates and scientific enquirers.9 A significant number of these were derived from continental sources. In 1580, for example, even as John Lyly’s Euphues was reading the antiquated account of Caesar’s travels to Britain, Hakluyt asked a possible common acquaintance at Magdalen College, Oxford, the linguist John Florio, to translate the rather more up-to-date accounts of Jacques Cartier’s voyages to Canada from Ramusio’s collection as Two Navigations to New France.10 Among English initiatives, the first major voyage to be reported in print independently was an account of John Hawkins’s third voyage, A true declaration of the troublesome voyadge of M. J. Haukins to the parties of Guynea and the west Indies in the yeares of our Lord 1567 and 1568 (1569). Others followed, such as the account by Dionyse Settle of Frobisher’s second voyage seeking a north-west passage, A true reporte of the last voyage … by Capteine Frobisher (1577), and George Best’s True discourse of the late voyages of discoverie for the finding of a passage to Cathaya (1578). As Thomas Nicolls’s description of the Canary Islands, which Hakluyt would later include in his Principal Navigations, demonstrates, the authority of such texts lay in their immediacy and closeness to the point of origin of the travel experience. Nicolls begins by opposing his own account based on seven years’ travel against the ‘great untruthes, in a booke called The New found world Antarctike, set out by a French man called Andrew Thevet’. ‘It appeareth by the said booke that he had read the works of sundry Philosophers, Astronomers, and Cosmographers, whose opinions he gathered together’, he notes, ‘[b]ut touching his owne travaile which he affirmeth, I referre to the judgement of the experient in our daies, and therefore for mine owne part I write of these Canaria Ilandes, as time hath taught me in manie yeares’.11 In addition to these printed texts, a large body of documents circulated in private correspondence and in the papers of the trading companies. A storehouse of both foreign and English voices, they consist of texts such as the permit of safe conduct given to Anthony Jenkinson by the Turkish Sultan in 1553, which Hakluyt includes with the note: ‘The very originall hereof was delivered me Rich. Hakl. by Master Jenkinson in the Turkish and French tongues’ (PN1, 82–3). Richard Staper is thanked profusely in Hakluyt’s 1589 epistle to the reader for giving him ‘divers things touching the trade of Turkie, and other places in the East’, which probably came from the archives of the Levant and Barbary Companies (PN1, sig. *4v). Others included in Hakluyt’s collection, such as the letters describing the first English voyage to India by John Newbery and Ralph Fitch in 1583, form the essential pre-history of the East India Company.

The presentation of these permits and letters in The Principal Navigations shows us how intensely Hakluyt’s own approach tries to strike a balance between old authority and new experience, the encyclopaedic ambitions of the old cosmographies and the constantly evolving immediacy of the new peregrinationis historia. Despite his contempt for the universal cosmographies, the attempt to outline an overarching narrative continues to define the shape of Hakluyt’s collection. In the epistle to the reader in the 1598–1600 edition, for instance, he writes eloquently of his self-imposed task to ‘incorporate into one body the torne and scattered limmes of our ancient and late Navigations by Sea, our voyages by land, and traffiques of merchandise by both’ (PN2, sig. *4v), and as Matthew Day has shown, for contemporaries like the Oxford scholar Gabriel Harvey too, it was the printing of ‘sundry’ accounts ‘in one volume’ that made Hakluyt’s text ‘a worke of importance’.12 Accordingly, the 1589 edition follows Ramusio’s method of covering the known world. Within its pages, Hakluyt’s documents are arranged in chronological and spatial order, starting with the earliest English voyages, focusing on the east and south-east, followed by the northern and western travels. Hakluyt broke with that pattern in the 1598–1600 edition by beginning with the northern voyages, but that rearrangement could be seen to establish yet more firmly what critics like David Harris Sacks have seen as a providential teleology, since now the collection could cover English travels from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account of King Arthur’s conquests of Iceland, Denmark, and Norway in 517 AD, to the western successes of Hakluyt’s own contemporaries in accounts of the recent English voyages to the West Indies in the 1580s.13 Hakluyt’s professed approach here performs a double duty, providing a narrative alternative to England’s undeniable belatedness on the global stage, as well as the means to its correction; historical failure in the actual practice of travel, in Mary Fuller’s words, is ‘recuperated by rhetoric’.14 If contemporary English exploration was a fragmented enterprise, reading through the ordered collection of travel reports and ancillary documents in Hakluyt’s text at least afforded an overview of progress across time, which could then invite imitation by subsequent travellers.

Yet, even as Hakluyt organizes the immense and disparate collection of material into a single entity, he keeps the contours of individual texts visible. He makes it a point to underline how hard it has been to achieve that overview, presenting the volume undeniably as a conglomeration of disparate accounts, brought together at great cost and ‘travail’. As the striking opening passage of the Epistle to the Reader in the second edition exclaims:

For the bringing of which into this homely and rough-hewen shape, which here thou seest; what restlesse nights, what painefull dayes, what heat, what cold I have indured; how many long & chargeable journeys I have traveiled; how many famous libraries I have searched into; what varietie of ancient and moderne writers I have perused; what a number of old records, patents, privileges, letters, &c. I have redeemed from obscuritie and perishing. (PN2, sig. *4v)

Hakluyt’s editorial approach to the texts in question itself corroborates this understanding, since it has the merit of adopting a concept with which his readers would have been deeply familiar. The citation of textual authority, as humanist pedagogy habitually taught its students, served to engender trust, enrich one’s argument, and display one’s scholarly labour. Pedagogues from Erasmus to Roger Ascham and every schoolmaster in between taught their students to draw on the testimony of pre-existing texts to amplify and elaborate their argument, allowing other writers—both ancient and modern—to bear ‘witness’ to their facts. At its most extreme, it is a habit that generated that classical and Renaissance oddity, the genre of the cento compiled almost entirely of quotations and extracts from other writers, which Richard Burton would praise in his Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). At its most familiar, its form is that which we saw Thomas Nicolls criticize in André Thevet’s habit of subsuming personal experience under ‘works of sundry Philosophers, Astronomers, and Cosmographers’. Hakluyt does not deny its power. As with the works of so many of his humanist contemporaries, while the texts he compiles often challenge the knowledge of earlier authorities, it does not preclude them from calling on the supporting voices of the ancients whenever necessary. But Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations, more than any other travel collection of the period, naturalizes and extends that trope. It makes the citation of witnesses the central narrative principle of his monumental compendium and gives it a unique turn through an overwhelming valorization of the witnessing of praxis. Hakluyt’s advertised aim, as he declares in his preface, is not only to allow ‘those men which were the paynefull and personall travellers [to] reape that good opinion, and just commendation which they have deserved’, but also to ascribe to them an unprecedented degree of personal responsibility. ‘[A]nd further that every man might answere for himselfe, justifie his reports, and stand accountable for his owne doings’, Hakluyt asserts, ‘I have referred every voyage to his Author, which both in person hath performed, and in writing hath left the same.’ ‘Whatsoever testimonie I have found in any author of authoritie appertaining to my argument, either stranger or naturall’, he notes, ‘I have recorded the same word for word, with his particular name and page of booke where it is extant.’ And while he promises to ‘meddle in this worke with the Navigations onely of our owne nation’, he admits that he has occasionally introduced ‘some strangers as witnesses of the things done yet are they none but such as either faithfully remember, or sufficiently confirme the travels of our owne people’ (PN1, sig. *3v).

He would have occasion to adapt and elaborate on that editorial principle. As he explains in his dedicatory letter to Walsingham’s successor, Sir Robert Cecil, in the final volume of the 1598–1600 edition:

Now where any country hath bene but seldome hanted, or any extraordinary or chiefe action occureth, if I finde one voyage well written by two severall persons, sometimes I make no difficultie to set downe both those journals, as finding divers things of good moment observed in the one, which are quite omitted in the other. For commonly a souldier observeth one thing, and a mariner another, and as your honour knoweth, Plus vident oculi, quam oculus [‘several eyes see more than only one’]. (PN2, sig. A2v)

What this means for travel writing in general, and for Hakluyt’s readers in particular, is significant. Hakluyt’s method brings together textual witnessing and the witnessing of praxis, and he makes the conjunction work hard, at multiple levels. He does not claim that subjective records of reality can ever express reality completely through textual means: we know that things observed by one person, after all, are often ‘quite omitted’ by another, and one man’s account may require to be filled in by that of others. It is an assumption emphasized by the organizing principal he adopts, based on the ‘double order of time and place’ (PN2, sig. A2v), grouping multiple documents within each geographical section in chronological order. But Hakluyt goes even further, by also listing them in the contents to the volumes under two separate headings: the ‘Voyages’ themselves, and the ‘Ambassages, Treatises, Priviledges, Letters and observations’ pertaining to those voyages, which supplement, interrogate, and occasionally contradict the stories told in the narratives that accompany them. In the sections on Anthony Jenkinson’s voyages to Russia, for example, that principle of organization opens up lacunae precisely through the sheer abundance of material. For each of the four voyages, Hakluyt gives at least one account from Jenkinson’s own ship, as well as supporting documents from other voyagers, both English and foreign, as well as official documentation of their travels. Jenkinson’s own account of the first voyage in 1557 is thus juxtaposed with the report of the returning Russian ambassador, Osep Napea, as well as the privileges and charters of the Muscovy Company. Each text fills in the gaps of another: the Muscovy Company documents give us the circumstances of the voyages, but not the details; elements of the journey ignored in Napea’s text are covered in Jenkinson’s; while the latter’s account of the Tsar’s displeasure at English lack of respect in the fourth voyage is prefaced by the careful description of Russian diplomatic protocol by the former. By presenting such partial observations in one volume, allowing readers to witness for themselves the imperfections, the fault lines, and the gaps as much as the matter itself, The Principal Navigations places itself at the heart of that crucial interchange between the gnosis and praxis of travel with which we started. The ‘travailes’ of both Hakluyt and the reader, to use a familiar Elizabethan pun, mingle with the ‘travels’ of the voyager and the transmission of the scattered pages of his fragile written testimony. In tracing the Jenkinson voyages, as in numerous other instances within Hakluyt’s volumes, the act of reading itself turns into a form of praxis, a virtual witnessing of those travels newly ‘incorporated’ into the volume in the reader’s hands. That process of active textual observation stimulates ‘real’ action in its own turn. New knowledge and new witness testimonies are produced in the wake of such action, again to be woven by Hakluyt and his successors into the story of travel.

* * *

Why is that emphasis on witnessing necessary? Commenting on the style of Renaissance English travel writing, William Sherman has noted the ‘complex rhetorical strategies’ that writers needed to adopt:

Its authors had to balance the known and the unknown, the traditional imperatives of persuasion and entertainment, and their individual interests with those of their patrons, employers, and monarchs. Given such diverse purposes, early modern travel writers were often torn between giving pleasure and providing practical guidance, between logging and narrating, between describing what happened and suggesting what could have happened. These rhetorical challenges, along with the novelty of their experiences, left travel writers with acute problems of authenticity and credibility.15

What made matters worse, of course, is that fiction often used the same rhetorical strategies to establish the authenticity of its own narratives. From the fantastic voyage at the heart of Lucian’s second century True Story, to the later narratives at least partially inspired by it, like Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), the name of whose traveller, Raphael Hythlodaeus, means ‘expert in nonsense’, Joseph Hall’s Mundus alter et idem (1605), Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1624, 1627), and Henry Neville’s Isle of Pines (1668), prose fiction had imitated the testimony of travellers frequently enough for its status to be for ever in doubt.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the rhetorical demonstration of personal responsibility remained a standard way of vouchsafing the truth-content of travel accounts. Reporting his journey to China in 1330, in an account which Hakluyt includes both in Latin and in English translation in the 1598–1600 edition, Friar Beatus Odoricus concludes with a sworn statement about the veracity of his narrative:

I frier Odoricus of Friuli [ … ] do testifie and beare witnesse unto the reverend father Guidotus minister of the province of S. Anthony, in the marquesate of Treuiso (being by him required upon mine obedience so to doe) that all the premisses above written, either I saw with mine owne eyes, or heard the same reported by credible and substantiall persons. (PN2, II, 66)

Partial vision, as we have seen Hakluyt point out already, is a trade-off that such witnessing has to accept. One man’s sight is liable to be subjective and incomplete; as Odoricus confesses, ‘[m]any other things I have omitted, because I beheld them not with mine owne eyes’ (PN2, II, 66). Yet, it is the closest that text can get to the experience of travel, to regenerating the gnosis that travel promises its practitioners. Writing a ‘discourse on trade’ to Michael Lok in 1569, Gaspar Campion asserts, ‘I write not this by heare say of other men, but of mine own experience, for I have traded in the countrey above this 30 yeres, and have bene maried in the towne of Chio full 24 yeres, so that you may assure yourselfe that I will write nothing but truth’ (PN2, II, 127). Hakluyt himself follows a similar practice in his own writing. The account of Thomas Butts regarding the English voyage to Newfoundland in 1536 is one of the few in The Principal Navigations reported by Hakluyt himself, but summing up Butt’s journey with the story of a recognition scene that would not have been out of place in the Odyssey, Hakluyt hastens to add the stamp of truth to it:

M. Buts was so changed in the voyage with hunger and miserie, that Sir William his father and my Lady his mother knew him not to be their sonne, untill they found a secret marke which was a wart upon one of his knees, as hee told me Richard Hakluyt of Oxford himselfe, to whom I rode 200. miles onely to learne the whole trueth of this voyage from his own mouth, as being the onely man now alive that was in this discoverie. (PN2, III, 131)

Even if the very nature of Hakluyt’s collection would seem to make a unified discussion of its prose something of an impossibility, such an emphasis on testimony and witnessing inevitably has both stylistic and social implications for English travel writing. Take style first. In his overview of Tudor travel literature in The Hakluyt Handbook, G. B. Parks described Hakluyt’s documents as the writings of ‘non-professional writers of only accidental skill’, but the rhetoric of plainness that they embrace is familiar.16 It is part of a discursive tradition that we remember Shakespeare’s consummate traveller, Othello, adopting when he asserted how his rude speech could only deliver a ‘round unvarnish’d tale’ (Act I scene iii), or that Montaigne writes about in his essay ‘Of Cannibals’, when he recommends receiving the news of far-off lands through ‘a most sincere Reporter or a man so simple that he may have no invention to build upon and to give a true likelihood unto false devices’.17 A practical focus on facts and what has been called a functional ‘plain’ style were recognized ways of establishing the veracity of one’s account. Thus, John Davis’s records from the 1587 voyage in search of a north-west passage simply notes on 13 August that ‘[t]his day seeking for our ships that went to fish, we strooke on a rocke, being among many iles, and had a great leake’ and follows it with the entry for 14 August, ‘[t]his day we stopped our leake in a storme’: the dry enumeration of facts, date, and circumstance replacing the dramatic and narrative potential of the situation (PN2, III, 118). On other occasions, even in the few literary documents that Hakluyt includes, the plainness of language is brought to the defence of the genre and authorial voice. So praising the writer of the fifteenth-century Libell of English Pollicie, a discourse on trade written in verse, Hakluyt explains that ‘notwithstanding (as I said) his stile be unpolished, and his phrases somewhat out of use; yet, so neere as the written copies would give me leave, I have most religiously without alteration observed the same: thinking it farre more convenient that himselfe should speake, then that I should bee his spokesman; and that the Readers should enjoy his true verses, then mine or any other mans fained prose’ (PN2, *6v). That advertised ‘plainness’ and transparency is the counterpart to travel writing’s familiar tropes of wonder and inexpressibility. It had existed before Hakluyt, of course: we saw its insistent display of the prosaics of everyday life—the length and the many inconveniences of the journey, details of food, weather, and customs—leaching into Lyly’s fiction at the beginning of this chapter, transforming his Euphuistic prose from the inside. But the sheer weight of examples in Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations would make it the stylistic norm for English travel writing. Perhaps more importantly, however, its use in Hakluyt’s volumes introduces English narrative prose to a very specific way of apprehending and communicating reality through text. His insistence on ‘plaine’ accounts and ‘homely stile’ focuses on an amalgamation of empirical details, on the apparently objective and transparent recording and precise measurements of facts. But as we have also seen, Hakluyt himself repeatedly reminds us that what the reader receives is partial and imperfect; in fact, that such partial nature and imperfections are what ties the text to the realities of praxis, what necessitates the praxis of editor and reader alike in its own turn. For numerous writers after Hakluyt, from Thomas Nashe to Lawrence Sterne, that productive tension, between an attempt to reflect reality through text and the use of the inevitable lacunae in such efforts as marks of authenticity in themselves, would become a site of creative engagement.

One consequence of that dependence on linguistic and stylistic transparency, as Stephen Greenblatt has argued, is that authority in early travel writing often derives ‘not from an appeal to higher wisdom or social superiority but from a miming, by the elite, of the simple, direct, unfigured language of perception Montaigne and others attribute to servants’.18 But even the social implications of linguistic plainness aside, Hakluyt’s insistence on the plainness of his own editorial ‘travails’, as well as his tendency to cast the reader in the role of witness to these apparently unmediated voices, effects a different, yet equally destabilizing ‘miming’ of the travel experience. The sheer range of texts that The Principal Navigations harbours is as volatile and as prone to confusing social norms and boundaries as travel and exploration themselves were accused of being by their critics and detractors. If in 1594, Thomas Nashe’s The Unfortunate Traveller could make his irreverent, acutely pragmatic page-boy hero Jack Wilton a fictional fellow-traveller of the aristocratic Earl of Surrey, then that dissolution of social boundaries is bookended by the 1589 and 1598 editions of Hakluyt. They are volumes dedicated as much to powerful patrons like Francis Walsingham and Robert Cecil as to the ordinary readers who might be inspired actually to turn reading into praxis, Sidneian ‘well-knowing’ into Hakluyt’s desired ‘well-doing’. Within their pages, the royal letters exchanged between Elizabeth I and the Ottoman Sultans Murad III and Mehmed III share a textual space with instructions prepared by Hakluyt’s cousin and mentor, Richard Hakluyt the lawyer, for English merchants in Turkey about ‘our Clothing and Dying’; scholarly exchanges between the cartographer Gerald Mercator and Hakluyt himself about the north-east passage are juxtaposed with Hugh Smith’s stolidly workmanlike account of the 1580s Pet-Jackman voyage in search of the same. Even the translation of the Latin texts in Hakluyt’s collection makes a telling point. As Peter Mancall points out, if Elizabeth and her policy-makers were the only targets of Hakluyt’s accounts, he could have simply printed the Latin originals; ‘[t]he fact of translation itself was proof of Hakluyt’s desired audience’.19

There is a reason why witnessing takes this curious turn for traveller and reader alike in Hakluyt’s collection, shaping both their prose and the nature of the company they keep. Recent historical and literary scholarship has revealed how central the ideas of witnessing and testimony were to a wide range of disciplines in the early modern period, and how developments in their conceptualization resonated far beyond their home turf in the practice of law. One prominent aspect of Barbara Shapiro’s work on the epistemological status of ‘matters of fact’, for instance, takes issue with Steven Shapin’s claim that the criteria determining the credibility of a witness in the scientific revolution were borrowed from early modern elite codes of honour and civility. As Shapiro has shown, throughout the early modern period, the issue of ‘who was deemed trustworthy depended in part on circumstances’, not simply on social status or birth.20 At the same time, English legal practice and the social composition of the English petty jury, which was traditionally charged with determining ‘fact’ (as opposed to determining ‘law’, a responsibility assigned to judges), ensured that the assessment of credibility too was gradually freed of its association with the elite. One can see how such a legal perception might have shaped Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations, where ‘plainness’, relevance, and immediacy of contact allow merchants to take their place next to monarchs, and seamen’s logbooks claim equal importance as scholarly redactions of knowledge.

It also allows us to see some of the most debated features of Hakluyt’s collection, like his decision to excise Mandeville’s travels from the second edition, in a new light altogether. Andrea Frisch’s argument about social changes in early modern France, where the medieval interpretation of testimony as the communal corroboration of the reputation and social standing of disputants slowly begins to lose ground, is equally valid for early modern England.21 Frisch argues that in circumstances where it was increasingly becoming the practice for witnesses to testify before strangers who could not easily evaluate their moral stance or draw on a communal understanding of their dependability, first-hand accounts and written depositions that recorded experiential knowledge and, in essence, allowed the court to ‘observe’ a sequence of events or action for themselves, became especially important. The ‘epistemic witnessing’ of events, in other words, begin to take precedence over the forms of ‘ethical’ witnessing which formed the cornerstone of medieval legal systems, and the written deposition, capturing and fixing knowledge or gnosis and, at the same time, capable of acting as a credible witness of praxis for its reader, takes on an epistemological import of its own. For Frisch, the medieval text of Mandeville’s incredible Travels offer a perfect case study of the earlier form of ‘ethical witnessing’, with its credibility resting on Mandeville’s readers’ readiness to believe in his reputation and status as a Christian knight, rather than purely on the style or content of his account. It is no surprise, then, that the document which replaces Mandeville in Hakluyt’s 1598–1600 edition is the account of Friar Odoricus, which we have seen before: a document whose evidentiary status, confirmed by the signed and attested statement that accompanies it, we can witness for ourselves.

The written accounts of travels are invested with a unique authority within such a system. While their credibility depends on their links with the actions of individual travellers (allowing every man might ‘answere for himselfe’), as written texts, they are, at the same time, clearly separable from their writers. Like the document that Hakluyt reports being found after the capture of the Portuguese ship, the Madre de Deus, in 1592, ‘enclosed in a case of sweet Cedar wood, and lapped up almost an hundredfold in fine calicut-cloth, as though it had been some incomparable jewel’ (PN2, II, sig. *4r), The Principal Navigations repeatedly emphasizes the identity of its documents as material objects. They act as evidence as well as testimony, capable of being passed hand to hand, of being exchanged, examined, collected, and valued. If Walter Ralegh’s Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana in 1596 had begun by apologizing to his investors that his ventures in the New World had failed to return their money and instead ‘only returned promises; and nowe for answere of both your adventures, I have sent you a bundle of papers’ (sig. A2r–v), Hakluyt’s endeavour would turn such bundles of papers into ‘treasures’, comparable to any of the other material returns of the actual travel itself.

By the time Richard Hakluyt died in 1616, the material he had collected from various sources themselves had become objects to be gathered and valued. By the mid-seventeenth century, The Principal Navigations was carried on board as a standard reference by the ships of the East India Company, and Hakluyt’s influence would continue to shape the writings of those who followed. Its most notable impact, expectedly, is on the genre of the travel collection itself. The material Hakluyt had continued to accumulate in the intervening years since the publication of The Principal Navigations would find its way ultimately into the second great early modern English compendium of travel texts: the four folio volumes of Samuel Purchas’s Hakluytus posthumous or Purchas his pilgrims (1625). Purchas’s handling of these texts has been the subject of much critical attention and his more interventionist editing has led to the characterization of Hakluyt as the ideal editor—discreet, tactful, and restrained—even though Hakluyt, we know, was far from the transparent conduit of textual records of travel that his readers have credited him with being.22 But both the astounding popularity of Purchas’s collections and our continued acknowledgement of The Principal Navigations’s place in the construction of England’s identity as nation and empire underline Hakluyt’s single most significant contribution, his ability to make a virtue of that range of disparate material, of the many different voices that his collection accommodates. It is a lesson which he perhaps learned from the trading companies for whom he worked frequently as a consultant, where financial ‘incorporation’, the gathering of multiple individual investments into a single entity significantly greater than the sum of its parts, had always provided the basis of the risky new long-distance trading ventures. It is not simply a coincidence, after all, that the most active years of his endeavour coincided with the rapid proliferation of English trading companies and joint-stock ventures, from the Eastland Company, with its interests in the Baltic trade route in 1579 and the Turkey Company in 1581, to the East India Company in 1600 and the Virginia Company in 1606. What has often been seen as Purchas’s more heavy-handed editing of travel texts, as Ralph Bauer has argued, would continue to show a similar sensitivity to the changing face of mercantilism in the seventeenth century under Stuart rule, enfolding both editor and texts within the processes of knowledge and profit production in a new age.23

Beyond the travel collection, Hakluyt’s engagement with that central disjunction between the experience and representation of travel, and the social and linguistic implications whose traces we have followed throughout this chapter, would continue to develop in travel accounts as different in style and tone as Thomas Coryat’s whimsical Crudities hastily gobbled up in Five Months Travels in France, Italy, &c (1611) and Greetings from the Court of the Great Mogul (1616), and Captain John Smith’s General Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (1624). The reports that Coryat, the son of a Somersetshire rector, produced of his journeys through Europe, the Middle East, and India offer a relentless collection of the material evidence of individual experience. From incongruously detailed meditations on the size of German beer barrels to self-portraits on the backs of Indian elephants, from reproductions of letters and speeches written, to poems and greetings received, his volumes are in many ways a carnivalization both of that permanent sense of impending slippage between text and experience which drove Hakluyt’s collection forward, and of its acute understanding of the granularity of lived experience itself. But they are also examples of that ordinary individual testimony which The Principal Navigation had valorized and invited, as is the familiar note with which John Smith begins his History, when he asserts at the outset that ‘[t]his history might and ought to have beene clad in better robes then my rude military hand can cut out in Paper Ornaments’, but ‘of the most things therein, I am no Compiler by hearsay, but have been a reall Actor’.24 The truth-content of Smith’s account is much debated, but it is undeniable that as a vindication of his actions in the Virginia colony against the alleged opposition of his aristocratic competitors, it significantly opens up a space for a personal, subjective voice in a deeply ideologically and politically inflected arena.

In fiction, too, the ‘witnessing’ which the Principal Navigations had celebrated, and the radically unstable discourse of experience that necessitated it, would leave their mark. Behind the multiplying lists of criminal jargon in Robert Greene’s cony-catching pamphlets, for instance, one can see the traces of Hakluyt’s word-lists of foreign languages: from Jacque Cartier’s Huron vocabulary and John Davis’s Eskimo word-list, to the lists of Guinean, Algonquian, and Javanese dialects. There had always been a fascination with the so-called ‘canting terms’ of the criminal underworld in Elizabethan literature, but the word-lists in Greene’s immensely popular ‘discoveries’ of that alternative society bring something of the strange and the foreign back home to roost in Elizabethan London. If the gaps they open up in one’s view of the known, and the tension they constantly evoke between text and experience, order and fragmentation, identification and estrangement, are early signs of novelistic plurality and the centrifugal pull of lived experience, touches of Bakhtinian heteroglossia and ‘prosaicism’ in early modern prose, then they are shaped implicitly by Hakluyt’s compendium. Elsewhere, as Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe illustrates, the emphasis on ‘plainness’ and the prosaic, on empirical detail and observation, which Hakluyt’s example had also established as an expected narrative turn in travel writing, would continue to be adopted by imaginative fiction as it negotiated its central relationships, both with the individual voice and the world beyond.

Admittedly, such brief examples can show us only glimpses of the inflections that Hakluyt’s collection helped to introduce into English travel writing, and of the number of discourses in which it appears both directly and indirectly as participant, interlocutor, and influence. Heterogeneity is their defining feature. The voices of Hakluyt’s ‘witnesses’, as we have seen, are varied and irregular; the picture of early modern English travels that emerges from their pages is an amalgamation of interests, perspectives, and knowledge. Yet, in that very range that it both displays and contains, The Principal Navigations stands testimony to the sheer range of early modern English travel writing and the multiplicity of English perspectives on the rapidly expanding world which generated that textual engagement in the first place.

Campbell, M. B. The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400–1600 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988).

Carey, Daniel and Claire Jowitt, eds. Richard Hakluyt and Travel Writing in Early Modern Europe (Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012).

Day, M. ‘Hakluyt, Harvey, Nashe: The Material Text and Early Modern Nationalism’, Studies in Philology, 104.3 (2007): 281–305.

Fuller, Mary. Voyages in Print: English Travel to America, 1576–1624 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Hadfield, Andrew. Literature, Travel, and Colonial Writing in the English Renaissance, 1545–1625 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

Hakluyt, Richard. The Principall Navigations, Voyages and Discovries of the English Nation, made by Sea or Ouer Land, to the Most Remote and Farthest Distant Quarters of the Earth, at any Time within the Compasse of these 1500 yeres: Divided into Three Severall Parts, According to the Positions of the Regions, whereunto they were Directed (London, 1589).

——— The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discovries of the English Nation, made by Sea or Ouerland, to the Remote and Farthest Distant Quarters of the Earth, at any Time within the Compasse of these 1600 yeres: Divided into Three Severall Volumes, According to the Positions of the Regions, whereunto they were Directed (London, 1598–1600).

Helgerson, R. Forms of Nationhood: The Elizabethan Writing of England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Maccrossan, Colm. ‘New Journeys through Old Voyages: Literary Approaches to Richard Hakluyt and Early Modern Travel Writing’, Literature Compass, 6.1 (2009): 97–112.

Mancall, Peter C. Hakluyt’s Promise: An Elizabethan’s Obsession for an English America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

Parker, J. Books to Build an Empire: A Bibliographical History of English Overseas Interest to 1620 (Amsterdam: N. Israel, 1965).

Parks, G. B. Richard Hakluyt and the English Voyages (New York: American Geographical Society, 1928).

Payne, A. Richard Hakluyt: A Guide to His Books and to Those Associated with Him, 1580–1625 (London: Quaritch, 2008).

Quinn, D. B., ed. The Hakluyt Handbook (London: Hakluyt Society, 1974).

Rubiés, Juan-Pau. Travellers and Cosmographers: Studies in the History of Early Modern Travel and Ethnology (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007).

Sherman, William. ‘Stirrings and Searchings (1500–1720)’, in Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 17–36.