IN a period of considerable generic experimentation, the essay stands out as a vehicle for early modern reading and writing practices. Francis Bacon, the most visible English exponent of the form, offers a typically concise summary of the nexus between reading, conversation, and reflection that is characteristic of the rationale for the early modern essay: ‘Reading maketh a full man; conference a readye man; And writing an exacte man’ (1597: 1).1 The early modern essay is the perfect example of self-conscious intertextuality, in part fuelled by its connections with the commonplace book. So it is not long before Bacon refers to the most famous of all Renaissance essayists: ‘And therefore Mountaigny saith prettily …’ (1625: 5). Montaigne balanced the essay’s reliance on commonplace knowledge with self-examination and introspection: ‘I am one of those that feele a very great conflict and power of imagination’ (i.40).2 Montaigne’s style of personal revelation leads him to offer a witty and ironic reflection on the way that, for him, the essay is less a repository, more a self-analysis: ‘These are but my fantasies, by which I endevour not to make things knowen, but my selfe … And if I be a man of some reading, yet I am a man of no remembring’ (ii.236).

Montaigne generates the feeling that his essays convey a kind of mediated autobiography, while Bacon typifies the English essayist who is assembling and negotiating a series of commonplaces, where the impression of an individual response is conveyed more through prose style than through personal revelation. In his searching and original analysis of the early modern essay, Scott Black stresses the nexus between a method of reading, and a method of writing, in which essays are ‘the tools with which readers negotiate a print culture composed of numerous other negotiations and negotiators’ (11).3 But within what might sound like a rather claustrophobic space, these negotiations produced works that are often striking in their aphoristic immediacy. When we read Bacon’s essays, we don’t feel that we ‘know’ him the way that we feel we know Montaigne, but we do feel that we have some access to Bacon’s distillation of his reading and thought, where reading, writing, and thought, in Scott Black’s terms, are inseparable.

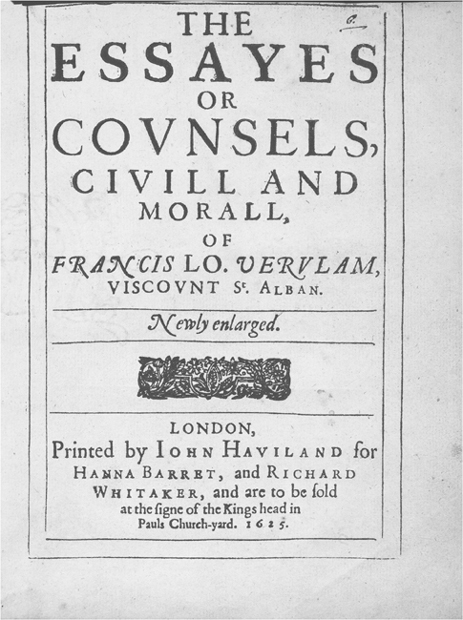

But if we begin with Bacon as the major, canonical example of the early modern English essay, we have to take into account the way his approach to the genre changed as he tinkered with his work over a period of some thirty years. This process was in part a shift from the brief, clipped, elliptical essays published in 1597, which clearly show their connections with the commonplace book, and the essays as they appeared in their 1625 printing, where they have not only increased dramatically in number (from ten to fifty-eight), but also each one has grown, and Bacon’s style breathes more easily and has become more self-reflective. While the essays in the 1597 volume seem to be purely occasional pieces, by 1625 they become a cumulative glimpse into Bacon’s cogitations, during which he does not simply incorporate past wisdom into his essays, but mingles his own wisdom with that of the ancients. This is most appropriate for an adherent to the cause of humanist notions of progress and advancement, and for the author of The Advancement of Learning. Bacon also used the essay form to distil the political experience he garnered during his slow rise to eventually become Lord Chancellor, and his rapid fall in 1621. The tiny 1597 volume was entitled Essayes. Religious Meditations. Places of perswasion and disswasion. In 1625, the title emphasizes the political wisdom being dispensed: The Essayes or Covnsels, Civill and Morall (Fig. 28.1). The essays that are ‘counsels’ provide not only a careful analysis of realpolitik, but also a glimpse into the nature of a man experienced in negotiating the slippery path to advancement, who provides a view from the top, and also from the bottom.

A good example is the essay that was entitled ‘Of Sutes’ in 1597. When the 1597 volume was published, Bacon was an ambitious, frustrated thirty-six-year-old, who had gained little from the efforts of his patron, the Earl of Essex, despite offering ample evidence of his legal and philosophical ability. In particular, Bacon had failed twice in suits to become attorney general, so it is scarcely surprising that ‘Of Sutes’ has a cynical tone throughout. The opening of the essay is a good example of how Bacon’s curt, aphoristic style arrests the reader’s attention: ‘Manie ill matters are vndertaken, and many good matters with ill mindes. Some embrace Suites which neuer meane to deal effectually in them. But if they see there may be life in the matter by some other meane, they will be content to winne a thanke or take a second reward’ (6). Some of this essay may read like a manual of instruction for suitors, but the penultimate sentence seems to reflect Bacon’s own experience of ill-judged timing: ‘But tyming of the Sutes is the principall, tyming I saye not onely in respect of the person that shoulde graunt it, but in respect of those which are like to crosse it’ (7).

By the time of the 1625 volume, where the title becomes ‘Of Sutours’ (as it was in the contents and running head for 1597), Bacon could look back on the success of his suits to King James (as opposed to Elizabeth), which led to him finally becoming attorney general in 1613, then lord chancellor in 1618, but losing everything following his impeachment in 1621. The reworked opening of the essay in 1625 offers a remark directed at public policy, rather than a reflection of private experience, and at the cost of losing the punchiness of the previous opening sentence with its balanced ‘ill matters’/‘ill mindes’: ‘Many ill Matters and projects are vndertaken; And Priuate Sutes doe Putrifie the Publique Good’ (288). The bitter tone is further enhanced by the stylistic avoidance of any balance at all (‘ill’ is replaced by ‘bad’): ‘Many Good Matters are vndertaken with Bad Mindes; I meane not only Corrupt Mindes, but Craftie Mindes, that intend not Performance’ (288). Given the considerable popularity of Bacon’s essays—they circulated in manuscript, as well as going through twelve editions (in various formats) prior to 1625—pronouncements about public policy and political expediency must have been read against the background of Bacon’s personal experiences, and the 1625 reflection on suits would have struck an ironic note with many. The 1597 essay ended with a wry reflection on how it must have felt to have pursued men of infl uence: ‘Nothing is thought so easie a request to a great person as his letter, and yet if it bee not in a good cause, it is so much out of his reputation’ (7). The 1625 version ends with a more expansive view expressed by someone who had by now moved from suitor to recipient of many suits, some of which were his undoing: ‘There are no worse Instruments, then these Generall Contriuers of Sutes: For they are but a Kinde of Poyson and Infection to Publique Proceedings’ (291).

FIGURE 28.1 Francis Bacon, Essays (1625), title page

The expanded collection contains many essays that could be classified as broadly political, covering topics such as ‘great place’, ‘seditions and troubles’, and ‘the true Greatnesse of Kingedoms and Estates’. Given that Bacon’s essays were so popular, these kinds of topics were taken up by other essayists, and the comparatively abstract political or social essay of reflection remained infl uential through to eighteenth-century essayists like Samuel Johnson. Bacon’s style may have expanded in the manner discussed above, but even the later style remains aphoristic and eminently quotable, sticking in people’s minds even today: ‘What is Truth; said jesting Pilate; And would not stay for an Answer’; ‘Men feare Death, as Children feare to goe in the darke’; ‘Revenge is a kinde of Wilde Justice’. This refl ects the interconnection between essay and commonplace book, and it illustrates how Bacon’s essays were political counsels and also, in Stanley Fish’s apt phrase, a ‘continuous attempt to make sense of things’.4 Yet, the Montaigne side of the essay equation has also crept into Bacon’s later volume, with a number of more personal refl ections on subjects that, if not entirely apolitical, are not exactly connected to public policy or individual political action. The most famous of these is the essay on gardens, which appeared for the first time in the 1625 volume. The opening of this essay neatly illustrates Bacon’s use of a more relaxed style: ‘God Almightie first Planted a Garden. And indeed, it is the Purest of Humane pleasures. It is the Greatest Refreshment to the Spirits of Man; Without which, Buildings and Pallaces are but Grosse Handy-works’ (266).

‘Of Gardens’ is not simply a philosophical musing, as it refl ects Bacon’s long-standing, practical interest in gardening and garden design. The detailed advice about, not merely design, but also planting, serves in the end to increase the reader’s sense of Bacon’s engagement and personality. Pleasure is taken in the very naming of the plants:

I like also little Heaps, in the nature of Mole-hils, (such as are in Wild Heaths) to be set, some with Wilde Thyme; Some with Pincks; Some with Germander, that gives a good Flower to the Eye; Some with Periwinckle; Some with Violets; Some with Strawberries; Some with Couslips; Some with Daisies; Some with Red-Roses; Some with Lilium Convallium; Some with Sweet-Williams Red; Some with Beares-Foot; And the like Low Flowers, being withal Sweet, and Sightly. (276)

The delight in specificity spills over into a cajoling tone quite unlike the curt, politic advice of the ‘counsels’: ‘For as for Shade, I would have you rest, upon the Alleys of the Side Grounds, there to walke, if you be Disposed, in the heat of the yeare, or day’ (278). The essay is carefully composed to induce the repose refl ecting a well-planned garden, as Bacon moves from the general structure to the variety of plantings, to the use, showing that nothing compares ‘to the true Pleasure of a Garden’ (145). The self-refl exive and, at times, almost whimsical tone of this essay perhaps indicates Montaigne’s infl uence, but the careful structure and the attention to detail is characteristic of Bacon and what might already be called an English essay style.

Bacon also wrote essays which move between cynical (or knowing) counsel and more expansive refl ection.5 Two interrelated essays move in this characteristic way between apparent autobiography and political counsel: ‘Of Parents and Children’ and ‘Of Marriage and Single Life’. In the first of these two essays, the childless Bacon seems especially self-revealing when he writes ‘the Noblest workes, and Foundations, haue proceeded from Childlesse Men; which haue sought to expresse the Images of their Minds; where those of their Bodies haue failed’ (32). Bacon goes on to consider the discord created by distinctions between siblings: ‘A Man shall see, where there is a House full of Children, one or two, of the Eldest, respected, and the Youngest made wantons; But in the middest, some that are, as it were forgotten, who, many times, neuerthelesse, proue the best’ (33). Bacon himself had an older brother, Anthony, three older half-brothers, and five sisters. Anthony was in some respects Francis’s shadowy friend, rival, and alter-ego, let down in the end by illness, which allowed Francis to secure some of Anthony’s political credit with the incoming King James.6 The essay concludes with a self-satisfied aside: ‘Younger Brothers are commonly Fortunate’ (35).

Francis Bacon did not marry until 1606 (he had courted Elizabeth Hatton unsuccessfully a decade earlier) and his views on marriage begin with an often-cited aphorism: ‘He that hath Wife and Children, hath giuen Hostages to Fortune, For they are Impediments, to great Enterprises’ (36). In this essay, Bacon seems to be having a dialogue with himself about the consequences of marriage and the relationship between great enterprise, and being unencumbered: ‘the best workes, and of greatest Merit for the Publike, haue proceeded from the vnmarried, or Childlesse Men’ (36). Once again, it is tempting to see some self-aggrandizement here. Yet, at the same time, Bacon muses that unmarried men may be ‘best Masters’, but they are not always best subjects because ‘they are light to runne away’. This essay, in particular, unfolds more as a meditation than as a series of commonplaces and it balances counter-arguments about personal versus state responsibility.

When most people today think of the early modern English essay (or perhaps one should say ‘if’ they do), Bacon is the only writer who comes to mind, but the popularity of the genre is attested to by numerous examples, many of which were extremely popular as printed books in the seventeenth century, and many of which circulated in manuscript. Indeed, the popularity of the printed essay collection in particular provoked a grumpy reflection from Ben Jonson on the ‘undigested’ nature of essays. Jonson finds fault with the idea that the essay collection infl ected by the commonplace book was worthy of public display; in his view, the essay was an example of a genre that made sense as a private study aid, rather than a public utterance (he makes this remark in his own commonplace/miniature essay collection, Timber, or Discoveries, which was, of course, only published posthumously, in 1641):

Some that turne over all bookes, and are equally searching in all papers, that write out of what they presently find or meet, without choice; by which meanes it happens, that what they have discredited, and impugned in one worke, they have before, or after extolled the same in another. Such are all Essayists, even their Master Mountaigne. These in all they write, confesse still what bookes they have read last; and therein their owne folly, so much, that they bring it to the Stake raw, and undigested: not that the place did need it neither; but that they thought themselves furnished, and would vent it.7

It is true that many early modern essay collections were refl ections of a fad and were not especially well digested. We would certainly now demur at the idea that Montaigne adds nothing to what he has read, but Jonson’s notion that the essay shades into a mere recapitulation hints at Scott Black’s analysis of the genre as being to do with how to read and the intertextuality of early modern thought in general. For Bacon, as we have seen, there was, in fact, an elaborate process of digestion that is refl ected in the constant revision of his essays, and is evident in their increasingly crafted nature. One can contrast Bacon with William Cornwallis, an essayist who is now comparatively obscure, but who might be seen as matched only by Bacon in his fascination with the way a commonplace could metamorphose into an essay. Indeed, Don Cameron Allen has argued that Cornwallis, rather than Bacon, was a pioneer of the essay form in England; he first published his collection in 1600 and it was very successful, if not quite as popular as Bacon’s, running to nine editions by 1632.8 Cornwallis is a less intellectual, but also less studied, essayist than Bacon; his casual style is more attuned to Montaigne, and the sense of autobiographical musing that seems immediate and attractive to us would have horrified Jonson.9 Like Montaigne (though less expansively), Cornwallis offers glimpses of an attractive personality musing about commonplace ideas in a less than entirely commonplace way. If you read through his essays consecutively you get a clear sense of Cornwallis’s personal history. Cornwallis also comments on broadly political or social ideas from the perspective of a comparatively modest gentleman, rather than being a political ‘player’ like Bacon. One can scarcely imagine Bacon frequenting an alehouse, let alone writing an essay on one as Cornwallis did. At the same time, Cornwallis shared a number of topics with Bacon, notably counsel, vainglory, fame, ambition, love, and friendship.

Cornwallis’s attractive personal tone is evident from the first essay in his collection, ‘Of Resolution’, which balances between a certain stoicism and a disarming admission of his humanity: ‘Me thinkes I am strong and able to encounter any affection; but hardly haue my thoughts made an ende of this gallant discourse, but in comes a wife or a friend, at whose sight my Armour of defence is broken, and I could weepe with them or be content to laugh at their triuiall sports’ (5). Even when Cornwallis offers a conventional account of the nature of his studies, he injects a personal note:

My steps are the steps of mortality, and I do stumble and stagger for company and crawle rather then goe; yet I desire to get further and to discouer the Land of light. To this end I reade and write, and by them would faine catch an vnderstanding more then I brought with me before decrepitenesse and death catch me. (34)

The search for enlightenment through study is made literal, and as we build up a picture of Cornwallis’s personality through the essays we see him as a modest and often self-deprecating man—again, this is in contrast to Bacon, who is not only an (impressively intelligent) egotist, but whose essays remain separate instances of contemplation and often of proselytizing for the cause of the author. In ‘Of Affection’, Cornwallis disarmingly argues himself towards a fairly typical stoical position, but on the way offers some poignant evocations of babies and parental engagement: ‘Euen that honest harmelesse Affection which possesseth parents towards their children, mee thinkes, whilst they are yet but lumpes of fl esh and things without all merit should not be so ardent and vehement. Pitty and commiseration fittes them better then loue, of which they are no way worthy’ (81). And yet, he goes on, how fortunate it is that logic does not prevail in this area: ‘But it is well that Nature hath cast the extremities of this disease vpon mothers’ (81). Cornwallis is, like all essayists, drawn to moral maxims and sage generalizations, but he tends to inject a personal note that moves his argument obliquely. Bacon and Cornwallis’s essays on vainglory further this comparison. Bacon begins with a maxim, leading to a confident assertion:

It was prettily Deuised of Aesope; The Fly sate vpon the Axle-tree of the Chariot wheele, and said, What a Dust doe I raise? So are there some Vaine Persons, that whatsoeuer goeth alone, or moueth vpon greater Means, if they haue neuer so little a Hand in it, they thinke it is they that carry it. They that are Glorious, must needs be Factious; For all Brauery stands vpon Comparisons. (1625: 308)

Bacon’s essay unfolds in this way through to a stern conclusion: ‘Glorious Men are the Scorne of Wise Men; the Admiration of Fooles; the Idols of Parasites; And the Slaues of their own Vaunts’ (311). As in most of Bacon’s ‘moral’ essays, memorable phrases are marshalled in order to offer general conclusions about human nature. Cornwallis veers between this style and something more idiosyncratic, or even eccentric. For Cornwallis, vainglory migrates from soldiers and statesmen to everyone, including the author: ‘Let vs thinke then of vaine-glory as it deserueth (and not of the name but nature) not with a disallowance in generall but particularly applying it, disallow so much of our selfe as is infected with it’ (186). Cornwallis always thinks of his essays as provisional in this way. As he notes in his essay on essays, unlike other ‘short writings’, even Montaigne’s, ‘mine are Essayes, who am but newly bound Prentise to the inquisition of knowledge and vse these papers as a painter’s boy a board, that is trying to bring his hand and his fancie acquainted’ (190). Cornwallis is devoted to the idea of the assay/essay that meanders: ‘Nor if they stray, doe I seeke to amende them; for I professe not method, neither will I chaine my selfe to the head of my Chapter’ (202). And yet, as with all such tropes, Cornwallis in fact exercises careful control over his supposed wanderings and tends to structure his essays through a combination of vivid image and self-refl ection, as indeed the essay from which I have been quoting concludes:

If there be any yet so ignorant as may profit by them, I am content; if vnderstandings of a higher reach dispise them, not discontent; for I moderate thinges pleasing vpon that condition, not to be touched with thinges displeasing. Who accounts them darke and obscure, let them not blame mee, for perhaps they goe about to reade them in darknesse without a light, and then the fault is not mine but the dimnesse of their owne vnderstanding. If there be any such, let them snuffe their light and looke where the fault of their failing restes. (202)

One of Cornwallis’s more endearing moments, for a modern reader, which for an early modern reader may well have been part of his persona as eccentric, is his defence of female education. This occurs in a wonderful essay on fear, which begins with a quirky dismantling of male self-confidence:

We heare from our nurses and olde women tales of Hobgoblins & deluding spirits that abuse trauellers and carry them out of their way. We heare this when wee are children and laugh at it when we are men, but that we laugh at it when wee are men, makes vs not men; for I see few men. Wee delight not perhaps in Iigges, but in as ridiculous thinges wee liue. (108)

Cornwallis segues into an analysis of why women might be fearful and decides that education will enable women to overcome any physical weakness: ‘wee leaue our women ignorant and so leaue them fearefull’ (108). Cornwallis stresses that all women lack is opportunity: ‘I do not think women are much more faultie in Nature’s abilities then men, but they faile in education; they are kept ignorant and so fearefull’ (109). He concludes that he ‘would haue them learned and experienced’ (109), and this will give them an equality with men that will counter fear and also enable women to participate in a wider range of experiences.

In his more fanciful vein, Cornwallis, as noted above, is able to produce a wonderful jeu d’esprit such as his essay on alehouses. This is, in part, another piece of self-deprecation, evident in the lively opening sentences:

I Write this in an Alehouse, into which I am driuen by night, which would not giue me leaue to finde out an honester harbour. I am without any company but Inke & Paper, & them I vse in stead of talking to my selfe. My Hoste hath already giuen me his knowledge, but I am little bettered; I am now trying whether my selfe be his better in discretion. (67)

Cornwallis then turns to a favourite theme: hypocrisy and degree. He notes that ‘every one speaks well & means naughtily’. This applies to all levels of society from ‘drunken Cobler’ to ‘hawking Gentleman’. Cornwallis is able to tie this neatly to his location, thereby moving from the clichéd notion of commonality to a more vivid and personalized meditation on degree:

I haue thus been seeking differences; and to distinguish of places, I am faine to fl y to the signe of an Ale-house and to the stately coming in of greater houses. For Men, Titles and Clothes, not their liues and Actions, helpe me. So were they all naked and banished from the Herald’s books, they are without any euidence of preheminence, and their soules cannot defend them from Community. (67)

This attraction to paradox led Cornwallis to publish a specific collection of essays demonstrating his wit and tapping into a growing interest in the intersection between paradox and satire. The enlarged edition, titled Essays of Certain Paradoxes, was published in 1617 and contains six paradoxical essays on topics such as ‘Good to be in debt’ and ‘The praise of Richard III’. These kinds of essay are in part infl uenced by the rhetorical dexterity practised through exercises that formed part of the repertoire of anyone with a grammar school education, but as written by Cornwallis, or Donne (who will be discussed below) the exercise becomes far more original and multi-faceted. Four unpublished paradoxes by Cornwallis exist, preserved in a single manuscript source (a commonplace book belonging to Sir Stephen Powle—a source which again underlines the link between essay and commonplace).10 The major published piece, on Richard III, is perhaps more of historical than literary interest, and lacks Cornwallis’s usual verve as he enumerates Richard’s ‘negative’ qualities and actions and justifies them.11 Indeed, Cornwallis may be aiming for paradox, but his defence of Richard’s legislative record anticipates modern assessments. The technique of recounting Richard’s dark deeds and then claiming they were politic or sensible or moral becomes rather repetitive after a while. The problem lies with the serious nature of the subject, and Cornwallis is more impressive tackling ‘The Praise of the French Pockes’, which is a free translation of an essay by the Spanish writer Gaspar Hidalgo, first published in 1605.12 In this essay, Cornwallis offers a witty narrative of overturned expectations, whereby ‘the noble and illustrious disease of the French Pockes’ is held to be in ‘reuerend estimation’. In part, Cornwallis opines, this is because the pox is a visible sign of transgression and therefore holy: ‘what greater token of holiness can there be in a man, then to haue a sense and feeling of his sinnes’ (D4v). The pox is also admired for being so well travelled and for choosing out those of a high social rank. Here Cornwallis does offer some social satire, but it is done with a light touch. The final essay in this brief volume is ‘That it is Good to be in Debt’. Here Cornwallis veers between amusing examples of the sensible nature of financial indebtedness and a rather more serious notion of indebtedness in the natural world (for example, the sun lends the stars light) and spiritual indebtedness. The essay, and accordingly the volume, concludes on a more sombre note than one might have expected from the earlier spirited witticisms: ‘I must resolue to liue in debt: in debt to GOD, for my being; in debt to CHRIST, for my well-being; in debt to Gods sanctifying SPIRIT, for my new being’ (F4v).

The four paradoxes that survive in manuscript are generally more light-hearted, but an earlier version of the debt paradox: ‘That it is a happiness to be in debt’, has a similarly spiritual and serious conclusion. It is difficult to determine their exact status, but stylistically these manuscript essays are not nearly as polished as those that Cornwallis published. The opening essay is the most comic: ‘That a great redd nose is an ornament to the face’. This includes the apercu ‘to haue a great Red nose is the true marke of a good witt’ (224). The other essays are in a similar vein: ‘That miserie is true Faelicity’ and ‘That Inconstancy is more commendable then Constancie’.

Paradoxical essays like Cornwallis’s were modish exercises and this is evident in those produced by John Donne. As Helen Peters notes, ‘Paradoxes were a fashionable feature of the Inns of Court Revels’ and this was part of the infl uence behind Donne, as well as the long Classical tradition of paradox that had its most famous Renaissance manifestation in Erasmus’s mock encomium Praise of Folly (Morae encomium, 1511, translated into English 1549).13 Donne’s ten paradoxes (and a number wrongly assigned to him) circulated quite widely in manuscript before their posthumous publication. They are generally shorter, and wittier, than Cornwallis’s, as one might expect from Donne. Donne makes little attempt to explore a potential argument, however paradoxical, but rather throws out as many twists as his imagination can encompass, with the resulting paradox taking on something of the style of an early Bacon essay. For example, in ‘That only Cowards dare dye’, Donne writes: ‘Truly this life is a tempest, and a warfare; and he that dares dye to escape the anguishes of it, seemes to me but so valiant, as he which dares hang himselfe, least he be prest to the warres’ (10).14 As one might expect, two of Donne’s paradoxes are directed at women: ‘That women ought to paint themselves’, which is reasonably benign, and ‘That it is possible to find some vertue in some women’, which reinforces a standard misogyny: ‘Necessity makes even bad things good, and prevayles also for them’ (22). Donne’s problems belong to an associated genre, which is aphoristic and again, traditionally a display of wit. A good example is ‘Why dye none for love now?’, which is brief enough to be quoted in full so that the sting in the tail might be enjoyed (and it provides yet another example of a misogyny taken for granted by gentlemen of wit at the time): ‘Because woemen are become easyer? Or because these later times have provided mankind of more new meanes for the destroying themselves and one another: Poxe, Gunpowder, young marriages and Controversyes in Religion? Or is there in truth no precedent or example of it? Or perchance some doe dye, but are therefore not worthy the remembering or speaking of’ (26). While the paradoxes and problems refl ect Donne’s fashionable engagement with what we might call Inns of Court literary display, Donne’s engagement with religion, leading to his career in the church, also produced variations on the essay form. The two main examples of this are the posthumously published Essays in Divinity and the considerably more famous Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, first published in 1624 and reprinted a number of times during Donne’s lifetime. In the former volume, Donne has a series of short essays taking as his starting point the first verse of Genesis for Book One and the first verse of Exodus for Book Two. The verse from Exodus, ‘Now these are the names of the Children of Israel which came into Egypt, &c.’, provokes a series of refl ections on the diversity of God’s creation, and it includes a moving statement of trust in the potential for a unified Christian faith: ‘Synagogue and Church is the same thing, and of the Church, Roman and Reformed, and all other distinctions of place, Discipline, or Person, but one Church, journeying to one Hierusalem, and directed by one guide, Christ Jesus.’15 The Devotions are specifically offered as meditations, rather than essays, but the two genres are related. The twenty-three devotions trace Donne’s experience of illness and accordingly offer a kind of autobiographical spiritual refl ection. As a whole, the sections offer a series of essayistic exercises, each also including a prayer and an expostulation. But there is a drama created by the sudden onset, duration, ebb and fl ow of illness, exemplified in the arresting opening: ‘Variable, and therefore miserable condition of Man, this minute I was well, and am ill, this minute.’

Devotions is famous for the passage that is one of literature’s most quoted refl ections; in context, it is part of Donne’s meditations on faith at a time of crisis, and in its provisional move from the individual to the world at large, as it connects one person with all people through a concentration on mortality, it resembles the idea of the essay as exploratory: ‘No Man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; euery man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod be washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends, or of thine owne were; Any Mans death diminishes me, because I am inuolued in Mankinde; And therefore neuer send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.’16 If Donne blurs the distinction between meditation, spiritual advice, and the essay, this is also evident in a number of other early modern writers, and the very blurring reminds us that most early modern genres are, in Rosalie Colie’s terms, ‘mixed’, and Colie herself noted that the essay was both a ‘new’ early modern genre and a particularly amorphous one.17 A good example is the collection of ‘resolves’, essays by Owen Felltham which, like Bacon’s essays, were a kind of public commonplace book that Felltham expanded from first publication in 1623, when he was only twenty-one, until the 1661 edition, which, handsomely published in folio, represents Felltham’s mature thoughts.18 Felltham’s essays were popular in all their versions and capture exactly the combination of didacticism and wit that carries on the renaissance ideal of sprezzatura (sprightly stylishness without pretension) that we have seen in Cornwallis, although Felltham is far more sober and spiritual in tone and subject matter than Cornwallis. In the 1623 volume (which I discuss here, given that Felltham’s final revised volume is well outside the boundary dates of this Companion) we see versions of the aphoristic style driven by a (perhaps precocious) Christian stoicism.19 For example, Felltham has a pithy account of the necessity to dwell upon mortality: ‘He that dyes dayly, seldome dyes dijectedly’ (20).20 The hundred ‘resolves’ can veer towards the cliché at times, but generally Felltham’s urbane tone carries the reader past any dull patches. Indeed, the evenness of tone makes Resolves a more coherent whole than many early modern essay collections—an effect enhanced by the fact that the individual essays are numbered, rather than named. Even on secular subjects like friendship, Felltham’s advice tends to be cautious and even somewhat dampening:

Euen between two faithfull friends, I thinke it not conuenient that all secrets be imparted; neither is it the part of a friend, to fish out that, which were better concealed. Yet I obserue some, of such insinuating dispositions, that there is nothing in their friends heart, that they would not themselues know with him; and this, if I may speake freely, I count as a fault. (111)

Felltham’s subtitle, ‘divine, moral, political’, points to the serious and often spiritual nature of his book, and it also echoes an earlier mixed genre text that, Kate Lilley has argued, indicates how women, so often excluded from canonical genres like the essay, were in fact also engaged with this fashionable form.21 Lilley specifically notes how the structure of Elizabeth Grymeston’s advice book, Miscelanea. Meditations. Memoratives (1604) ‘is modelled in style and structure on essay collections’.22 Grymeston’s advice is indeed decidedly essayistic, and relies on a series of commonplaces to guide her son towards a godly life: ‘What is the life of man but a continuall battel, and defiance with God? What haue our eies and eares beene, but open gates to send in loades of sinne into our minde?’ (C4). The volume as a whole is indeed miscellaneous, containing prayers and meditations, as well as essays of advice, in poetry and prose, and ends, as Lilley notes, with a series of aphoristic miniatures not unlike Bacon’s earliest essays, albeit even shorter.

There are many further examples of the essay blurring into other genres, and the essay as a form encouraged experimentation of all kinds. It stretched especially in the direction of biography and mock biography on the one hand, and in the direction of autobiography on the other. As potentially a form of biography, the essay has some links with the Character. The description of character ‘types’ has a long history, but in the early seventeenth century the collection of ‘Characters’ became extremely popular, beginning with the rather bland and didactic Characters of Virtues and Vices (1608) by the clergyman Joseph Hall, but fuelled by the publication of a series of Characters purportedly (but not actually) written by Thomas Overbury. Overbury had written a poem entitled ‘A Wife’, but after his scandalous death in the Tower in 1613 (this complicated situation involved the marriage of King James’s favourite Robert Carr to Frances Howard against the advice of Overbury, and, after the eclipse of Carr, an eventual charge of poisoning directed at Howard) the name of Overbury was enough to entice the publisher Lawrence Lisle to commission a series of prose characters which he published as being by Overbury.23 This volume, entitled A Wife Now the Widow of Sir Thomas Overbury (1614), contained twenty-two characters and was a runaway success, leading to successive expanded editions. The ‘Overbury’ Characters share some features with the essay, notably the witty, epigrammatic style and the aphoristic summing up of, in this case, the qualities of character types.

The scandal of the Carr/Howard marriage seems refl ected in the three Characters that follow Overbury’s idealizing ‘A Wife’ poem: ‘A good Woman’, ‘A very very Woman’, and ‘Her next part’. This sequence begins with further idealized qualities inherent in a good wife, with such succinct and stylish sentences as ‘She hath a content of her owne, and so seekes not a husband, but finds him’ (D2v).24 This is contrasted by the negative portrait of ‘a very very woman’, who embodies all the clichés of vanity: ‘She reads ouer her face euery morning, and sometimes blots out pale & writes red’ (D2v). Like many essays, these Characters are structured through accumulating observations, rather than a gathering argument, although they often reach a neat conclusion: ‘Her chiefe commendation is, shee brings a man to repentance’ (D3). The final Character in this trilogy continues the misogynistic theme: ‘Her Deuotion is good clothes, they carrie her to Church, expresse their stuffe and fashion, and are silent’ (D3v).

This sequence is followed by a collection of witty dissections of Jacobean types; for example: ‘A Puritane. Is a diseas’d peece of Apocrypha, binde him to the Bible, and hee corrupts the whole text’ (F). Virtually all of the Characters are satirical, though as well as scorned figures like ‘A Dissembler’, ‘A Flatterer’, ‘A Whore’, and ‘An ignorant glory-hunter’ there are ‘A Wise-man’ and ‘A Noble Spirit’, but the real verve lies in the satire.

John Earle’s collection of Characters, Microcosmographie (1628), was equally famous in its time and went through even more editions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than Overbury’s. Earle’s collection is more varied than the Overbury Characters and is less consistently satirical. Earle begins with the benign character of a child and it illustrates his urbane tone, which helps to move his Characters rather closer to the style of the essay. Earle’s many memorably phrased aphorisms build up a picture of the personality of the writer, rather than just delivering a series of quips to type-cast a character:

A Childe

Is a Man in a small Letter, yet the best Copie of Adam before hee tasted of Eve, or the Apple; and hee is happy whose small practice in the World can only write this Character…. His Soule is yet a white paper vnscribled with obseruations of the world, wherewith at length it becomes a blurr’d note booke …. Wee laugh at his foolish sports, but his game is our earnest: and his drums, rattles and hobby-horses, but the Emblems, & mocking of mans businesse. (B1–2)25

Earle is capable of sharp wit, but his generalized targets mean that the effect is usually benign, as with, for example, the clever opening sentence of ‘A selfe-conceited Man’: ‘Is one that knows himselfe so well, that he does not know himselfe’ (C3v). Perhaps inspired by Cornwallis’s essay on an alehouse, Earle includes the Character of a tavern, which is ‘a degree, or (if you will) a paire of stayres aboue an Alehouse’ (C4v). Earle’s Character is less personal than Cornwallis’s essay, but is nevertheless quirky and individual: ‘’Tis the best Theater of natures, where they are truly acted, not plaid’ (D). The essayistic nature of Earl’s volume is also enhanced by its range, as it covers some ingenious social types with refl ections upon them; for example, a shark (that is, someone who sponges off people), a blunt man, a critic, a reserved man, and a vulgar-spirited man ‘That comes to London to see it, and the pretty things in it, and the chiefe cause of his iourney the beares’ (J3v), as well as a number of places (‘Paul’s walk’, ‘a bowl-alley’).

It is perhaps this concrete particularity as a ground for wit that in the end marks out the Character as different to the essay. This can be illustrated by Nicholas Breton’s attempt to cash in on the popularity of both genres with Characters Upon Essays Moral and Divine (1615). Breton’s rather abject dedication to Bacon places him amongst those who followed Bacon’s lead, but the idea of ‘charactering’ the essays is both a glance at fashion and also a description of how the abstract topics of the essays are turned into something like a Character. Breton’s essays do, however, remain fairly abstract, lacking in general the detail of the true Character; this is evident from their topics: wisdom, learning, knowledge, practice, patience, love, peace, war, valour, resolution, honour, truth, time, death, faith, and fear. Indeed, Breton’s volume is really a fairly conventional essay collection that gestures towards the Character, presumably in order to increase sales. Breton’s rather abstract essays contrast nicely with a clever volume from a similarly prolific and popular author, Richard Brathwait. Brathwait’s Essays Upon the Five Senses (1620) neatly covers seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling. Brathwait’s tone is essentially moralizing and tends to undercut the more adventurous possibilities that might have arisen from the notion of each sense as an occasion for refl ection. There is a considerable amount of sermonizing, so that taste evokes Eve and sin, rather than sensuality: ‘No tempting delight shall feede my appetite.’26

Where the Character might point to the essay as biography, the essay as autobiography reaches perhaps its apogee in Henry Peacham’s The Truth of Our Times: revealed out of one man’s experience by way of essay (1638). Peacham combines his general refl ections—essays on such issues as schooling (he was himself a schoolmaster), opinion, or fashion—with a kind of discontinuous autobiographical narrative. In the section ‘Of making and publishing Bookes’, for example, Peacham offers a heartfelt account of the trials and tribulations of authors, noting ‘I have (I confesse) published things of mine owne heretofore, but I never gained one halfepenny by any Dedication that ever I made, save splendida promissa’ (39).27 Within a fairly conventional discussion of travel, Peacham enlivens his account with some anecdotes from his knowledge of the Netherlands and Germany. Similarly, when explaining why it is important to know one’s homeland as well as countries abroad, Peacham typically moves from the general to the particular (and personal): ‘here are many rarities in England, and our coast townes are worthy the view and the knowing, if it were but onely to satisfie strangers, who are many times inquisitive of the state of England, yea, and many times know it better than most of our home-borne gentlemen: herein Sir Robert Carr of Sleford in Lincoln-shire, a noble gentleman, and my worthy friend was much to be commended’ (144). Peacham’s whimsical refl ections anticipate the style and tone of the Augustan essayists like Addison, and might in some ways be seen as marking the bridge between the early modern essay and the second golden age of the genre in the early eighteenth century. Indeed, as with so many genres of early modern prose, the essay as practised by writers like Bacon, or Cornwallis, or numerous others, was new and experimental, and also formative.

In a fascinating discussion, Helen Deutsch traces the way that the essay dealt with the issue of disability, beginning with Montaigne’s ‘On Cripples’ and Bacon’s ‘On Deformity’, moving through William Hay’s 1754 essay exploring the connection between his own disability and subjectivity, to an early twentieth-century essay by Randolph Bourne.28 Deutsch is especially interested in the shifting nature of how a disability might be characterized, but she singles out the essay as a genre which, starting in the early seventeenth century, facilitates the combination of fl ickering self-examination with exemplarity. Bacon’s chameleon tone is illustrated by the careful placement in his 1625 volume of ‘Of Deformity’ after ‘Of Beauty’. ‘Of Beauty’ concludes somewhat darkly that ‘for the most part it makes a dissolute Youth, and an Age a little out of countenance: But yet certainly againe, if it light well, it maketh Vertues shine, and Vices blush’ (153). ‘Of Deformity’ moves from the balanced near paradox of its opening sentence—‘ Deformed Persons are commonly euen with Nature: For as Nature hath done ill by them; So doe they by Nature’ (154)—to a conclusion that consists of a roll-call of admirable examples culminating in Socrates.

After a period of neglect, we seem now to be experiencing a revival of interest in the essay as a vital literary genre, with contemporary practitioners being associated with a concurrent vogue for imaginative and experimental non-fiction writing of various kinds. The modern essay from Virginia Woolf through to Joan Didion or P. J. O’Rourke is a revitalized form that has gathered momentum and attention from the early twentieth century to the present day, when essay collections (along with short stories) have become viable again for publishers. From this perspective we are in a position to rescue the early modern essay from a period of, if not neglect, then under-appreciation.

Black, Scott. Of Essays and Reading in Early Modern Britain (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

Fish, Stanley. Self-Consuming Artefacts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972).

Hall, Michael. ‘The Emergence of the Essay and the Idea of Discovery’, in Alexander J. Butrym, ed., Essays on the Essay (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1989), 73–91.

Lilley, Kate. ‘Dedicated Thought: Montaigne, Bacon, and the English Renaissance Essay’, in Susannah Brietz Monta and Margaret W. Ferguson, eds., Teaching Early Modern Prose (New York: Modern Language Association, 2010), 95–112.

O’Neill, John. Essaying Montaigne: A Study of the Renaissance Institution of Writing and Reading (London: Routledge, 1982).

Pebworth, Ted Larry. ‘ “Real English Evidence”: Stoicism and the English Essay Tradition’, PMLA, 87 (1972): 101–2.

Vickers, Brian. Francis Bacon and Renaissance Prose (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968).