THEOPHILUS Wodenote, writing what he terms ‘a sequestered divine his aphorisms’ in 1654, extols in rhapsodic terms both the pith of biblical idiom and its adaptability as a language of analysis:

How ragged are mens expressions? How poor the pithiness of their discourses? In sight of the sacred Scriptures, their most accomplished Treatises are not so much as the light of a candle to the glorious brightness of the Sun in his chiefest splendour: In Gods book every particle hath his poise, every tittle is useful; every syllable is sententious; every word is wonderful.1

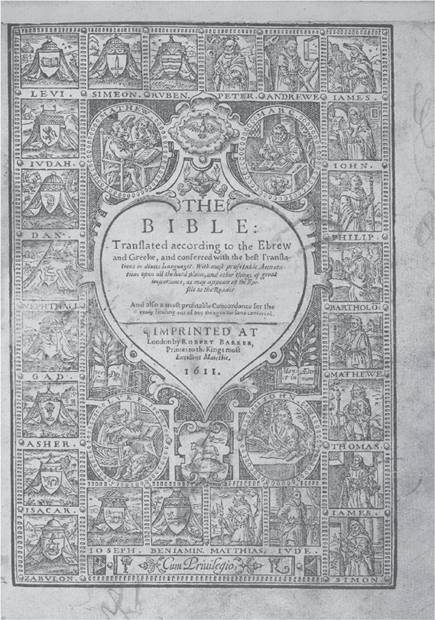

The biblical Word attracted a degree of astonishment that it penetrated so accurately, so astutely through time to refract the present. Its diamond edge and ability to cut to the quick did not necessarily indicate, however, an unalloyed appreciation of its eloquence. The English Bible was not deemed a work of consummate style. Indeed, comment was often made on the rough edges of the text, the discordance between books, its difficulty and internal contradictions, and, according to seventeenth-century standards, its stylistic crudity: rather than a polished gem, it was a whetstone for its readers. Robert Boyle sums up the complaints: ‘For some of them are pleased to say that Book is too obscure, others, that ’tis immethodical, others, that it is contradictory to it self, others, that the neighbouring parts of it are incoherent, others, that ’tis unadorned, others, that it is flat and unaffecting, others, that it abounds with things that are either trivial or impertinent, and also with useless Repetitions.’2 Where subsequent centuries have found in the Bible, or at least the 1611 Authorized Version (Fig. 30.1), the quintessence of English prose, its contemporaries were more ambivalent, and a certain embarrassment about the quality of writing in the scriptures is evident throughout the era.

Thomas Wilson, writing one of the numerous aids to biblical reading that poured from the early modern press, cautions: ‘We may not be offended with the simplicity and plainness of stile and matter, which wee find in scripture.’3 Other texts similarly worry over or seek to mitigate the plainness: ‘although we find not in sacred scriptures the idle or delicate itch of Words, that external sweetness or allurement’, says Benjamn Keach, we find instead ‘a Grave and Masculine Eloquence’. Such readers explained that the Bible needed to be accommodated to the varying capacities of both its original and modern-day audience: ‘Because the multitude of readers is promiscuous, it was needful that it should be understood by all.’4 The unfortunately comprehensive remit of the Bible—needing to descend to the meanest capacities—had, it was plain, obliged the Holy Spirit to compromise stylistically, to resist the Ciceronian, Attic, or Asiatic eloquence and indeed the sophistication of thought it might otherwise have tended to. Among the many who voiced this as an unfortunate and primal instance of dumbing down, James Fergusson in 1659 notes of the penmen of scriptures that, perhaps with some reluctance, they ‘would affect great plainnesse of speech, dimitting themselves, so far as is possible, unto the capacity of the meanest’.5 John Wilson, some years after, similarly concludes, ‘they are Written for all sorts and ranks of Men to make use of … therefore they are for the most part drawn in a vulgar condescending style’.6 In part, this is the product of the Bible’s own rough-hewn theatrics, when, for instance, ‘the Lord sayd to Hosea, Goe, take unto thee a wife of whoredomes and children of whoredoms: for the land hath committed great whoredom, departing from the Lord’. The God who enjoins his prophet to marry a prostitute and threatens then to strip naked and thrash Israel is not the God of delicate sensibility, nor was the prosody that rendered these warnings, with its crudity and repetitious vigour, deemed decorous or intrinsically literary to early modern tastes.7

Even amongst those who thought the Bible perfectly pitched to its task, few saw that task as involving an aesthetic experience. Edward Lane, a colonel in the New Model Army, thought that the political subject matter of the text precluded civility as unsuitable to God’s exasperation with the recalcitrance of the nation, that this was a prose and theatre of God’s Word, which, by any standards of decorum, demanded rigour and roughness. He noted in 1654 how the prophets of the Bible were not only conspicuously theatrical, but necessarily disrespectful in forcing their attentions upon a polity who would rather not listen:

FIGURE 30.1 King James Bible (1611), title page

An Isaiah must go naked, an Ezekiel must pourtray a city on a tyle, raise forts against it, lay siege to it, lie on his side and eat dung; a Hosea must take a common harlot to wife; an Amos must be call’d from among the herds-men, gathering sycamore-fruit: others much be taken from their Publicans seat (in the Custom-house) and fishing trade. And the Truth must be delivered in a dark uncouth maner.8

The Bible’s uncouth truth, so to speak, its blunt manner and exposure of social hypocrisy, was a touchstone for its more radical deployment: ‘For if there come unto your assembly’, as the Epistle of James has it, ‘a man with a gold ring in goodly apparel and there come in also a poore man, in vile raiment, and ye have respect to him that weareth the gay clothing, and say unto him, sit thou here in a good place and say to the poore, stand thou there’, then, as James goes on bluntly, ‘if ye have respect to persons, ye commit sinne’.9 The prose that bore such stark and unadorned matter was unlikely to receive much attention on the grounds of its parallelism and syncresis—indeed, the reader doing so might be missing the point, though we could note also that frankness was itself a literary trope. David Colclough, writing on the trope of parrhesia—blunt outspokenness—in biblical rhetoric, notes the early modern admiration of bold style against the mincing subterfuges of compromised everyday speech, taking Jesus’s as a rhetorical exemplar of the fearless, if inelegant, Word.10

This essay will explore both the embarrassment at the text that runs through the era and the countervailing argument that the Bible did indeed measure up a set of responses, the bulk of which appeared in the Restoration period, which attempted to laud a biblical aesthetic and to characterize it in terms of the sublime or majestic vehemence. However, noting such aesthetic responses, the many instances in which the Bible was acclaimed or carped at, risks at least a kind of anachronism. The Bible was less often assessed for its style than for its efficacy, its personal and political turning of men and women to God’s providential purposes. While the pen-men of scripture, from its poets to its gruff prophets, might be more or less able to turn a phrase neatly, and while in ineffable manner they might be the prophetic channel for the Holy Spirit, they remained human and their texts remained ephemeral, material, and subject to decay and tampering. Theophilus Wodenote, quoted earlier, might enthuse how ‘In Gods book every particle hath his poise’; however, the opposite of finding the Bible to be the beautiful and replete Word of God was not for everybody an aesthetic ranking of the scriptures in relation to the behemoths of classical style. Rather, to see the human flaws in the text, its breakages in transmission, and its dependence on the meagre resources of human language, led in a curious, but long-running, tradition to an almost outright anti-biblicism, in which the reader was required to filter the prose away, to be left with its wordless core. This is not, by any means, a step towards philosophical scepticism and secularism, though it was usually temperamentally sceptical and often anticlerical. On the contrary, it constituted one of major strands of radical Protestant thought on the nature of grace and spirit. To ask whether the style of the Bible was reckoned fine in the seventeenth century, in the way it so evidently was in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, is to interpose an aesthetic question which, while no doubt present, was not in the period divorced from the issue of how prose worked the soul up to the state of grace it was seen to promise. Thus, the latter half, of the essay, the antiphon to the discussion of biblical prose presented in the first half, is a series of texts that seek to make the language of the Bible fade to transparency. This, it seems to me, is an important and neglected aspect of the subject of biblical prose that has tended to see its major vectors in the discussion of ‘influence’ of the Bible (in subsequent centuries) and assessment of the often told story of the English translation.11 These two issues—influence and translation—demand prefatory attention, but neither is quite the central matter they have seemed to be.

There is much early modern prose—from the luxurious and learned to the relatively plain—that incorporates biblical phrasing into its fibre. The half-reference and the implied citation were, in an era that knew its Bible so thoroughly, a deeply rooted verbal habit. However, the flow and prosody of early modern literature, if we can generalize such a thing, bears surprisingly little resemblance to any biblical style. Sermon literature, for example, a field that produced some of the most brilliant prose of the era, owed many stylistic debts—to classical oratorical traditions, to Ramist habits of explication, and to traditions of moral exhortation—but it rarely aims to mimic the measure and rhythms of scriptural prose. Characterized in rhetorical terms, most notably by Debora Shuger, the English sermon, florid and ornate, lofty or plain, bore only a peripheral resemblance to its source material.12 Moreover, when writers produced ‘defences’ of biblical style—against the usually unspecific and whispered attacks on its eloquence—they tended to focus on its rich use of tropes and figures. But this is hardly what we mean by prosody, the texture and feel of a piece of writing, which can only be hinted at by an analysis of rhetorical ornament: early modern humanist habits of prose do not, in general, absorb the rhythms or copy the grain of the biblical.

Neither is the issue of translation a defining one in ascertaining the reception of biblical prose. While translation is of course important in other respects—battles raged over fidelity to and nuance of meaning, over the way doctrine was rendered, or how custom and culture might be seen as the context for action—comment is not frequently made on the scriptures being stylistically superior in the original. The Bible, as much in Hebrew or Greek as in its English rendering, was seen as an unprepossessing document and the English Bible was by no means thought of as stylistically detached from its origins. The desideratum that the Bible be read in the original tongues did not mean that it was considered any more elegant in those languages, even if it was closer to the primal Word. Complaints over translations tended to centre on theological and ecclesiastical, rather than aesthetic issues. And while a barbarous Latin, or Anglicization of Latin, might irk and rouse the inner pedant in the most mild-mannered humanist, in relation to the Bible, fidelity to the text, rather than aesthetics, was always the governing principle of translation. Accurate and scholarly rendering of phrase, rather than eloquence, was the chief criterion in the translation of the Bible.13

A further caveat to any discussion of biblical style is that there is, in fact, no such thing, there being no single biblical language, and the Bible being a hotchpotch of books. But early modern responses—while recognizing this—did have a sense of there being a typical Hebrew prose metre, which was identifiable still in translation. Francis Roberts, whose Clavis Bibliorum (1648) comments on and compares the styles of various biblical books, considers Luke as the most scholarly of the gospel writers: ‘By the very stile, which seems notably to indigitate Luke unto us, partly it being compleat and polished Greek becomming Luke an accurate Grecian.’ Nevertheless, there was, in Roberts’s view, a definite seepage of Hebrew style into Luke’s narrative: ‘it being replenished with Hebraismes, suitable to Luke’s native Genius, being by country a Syrian of Antioch, (the Syrian language being one of the Hebrew dialects)’.14 Robert Boyle notes similarly, ‘though the New Testament be not written in Hebrew, yet its Writers being Hebrews, have chiefly conform’d themselves to the Style of the Translators of the Old Testament’.15 This sense of a text that was both generically diverse and yet thematically unified is pervasive and the stylistic dynamics of the Hebraic idiom were deemed to be still at work when it came to the English reading experience. Naomi Tadmor has noted Tyndale’s working on the supposition that the Hebraic idiom transposed neatly into English and how English developed, in a complex reciprocity with its understanding of scriptural terms, over the seventeenth century.16

The existence of the Bible in English, for all that it was the rallying cry of the Reformation, remained something of a sop to the unlearned. Nathaniel Ingelo in 1658 offered a somewhat backhanded comment on the English scriptures, arguing that as a prince is content to engage in diplomacy that must travel via interpreters, so those short of the requisite Hebrew and Aramaic should be satisfied that they do in fact receive ‘the same mind of God’ as the educated:

And herein God shewed his care of the unlearned, who are the greater part of the world; for though they cannot read the Originall; yet having a Translation, which, in that it is a Translation, agrees with the Original, they receive the same mind of God that the Learned do. Why should any man be unsatisfied with this way of delivery, whereas Princes and States, in matters which they esteem the greatest, receive the Proposals of Ambassadours by an Interpreter?17

This is not an entirely ringing endorsement of the ability of the vernacular to act as conduit of the Word of God, but it is typical of the ambivalence about the scriptures, a text that indulged such dubious genres as parables, and whose status in classical rhetoric was particularly low, bordering on the Aesopian and childish. It was also, however, the form in which Jesus frequently spoke to his disciples, to the not infrequent embarrassment of expositors. Ingelo ventures the idea in 1658 that plainness in the Bible is itself a veil, a stylistic distraction, though he concedes that attempts to discover the complex pith were not always successful: ‘many that pretended to be great enquirers into profound mysteries, could not perceive any wisdome in them [parables] … nor discern truth, unlesse it were hid a little more under Philosophical shadowes’.18 John Lightfoot explains that this was a Jewish cultural matter, evident (if not entirely excusable, aesthetically speaking) across their sacred, profane, and exegetical writings: ‘Christs speaking of Parables, which he doth so exceeding much through the Gospel, was according to the stile and manner of that Nation, which were exceedingly accustomed to this manner of Rhetorick. The Talmuds are abundantly full of this kinde of oratory, and so are generally all their ancient writers.’19

The Bible’s multi-generic composition served, usefully enough, as a way of excusing and mitigating the parts deemed unsophisticated. Indeed, it allowed them to play their part in the spiritual and aesthetic crescendos of the encyclopaedic whole. However, praise of scriptural variety often sought to deny that it was prompted by any such concerns. John Barton’s The Art of Rhetorick (1634), ‘fitted to the capacities of such as have had a smatch of learning’, aims to laud the rhetorical breadth of the Bible, while insisting it barely deigns to notice such matters. The Bible must be seen as ‘altogether eschewing, and utterly condemning the impertinent use of frothie criticismes’, but was nevertheless written ‘in beautifull varietie, majesticall style, and gracefull order, infinitely and incomparably transcend[ing] the most pithie and pleasing strains of humane Eloquence’.20 In such accounts, the encyclopaedic range of the Bible was part of its quality, and the stylistic mish-mash became, in itself, an aspect of scriptural eloquence. The prose of the Old Testament prophets may have little in common with the narrative impulses and prosody of the New. Yet, however much their styles differ, there was a presumption that they formed a coherent whole, a hermeneutic unity, which created in its wake a sense of at least incipient stylistic integrity. Jeremy Taylor, in his Antiquitates christianae, argues that the dictating spirit conceived a conscious variation in prosody to embody the shift by which the Old Testament was enfolded into the new: ‘with a new style, with a quill taken from the wings of the holy Dove; the Spirit of God was to be the great Engraver and the Scribe of the New Covenant’.21

Characterizing the styles of individual books served to explain, in part, their purpose and utility. Francis Roberts in 1648 notes of Revelation that its idiom, though obscure, is by its sheer stylistic resonance able to pierce through even the most resolute ambivalence or stupidity: ‘The stile is stately and sublime, and may wonderfully take the highest notion; The expressions quick, piercing and patheticall, and may pleasingly penetrate the dullest affection.’22 Indeed, this capacity to go where other prose could not reach was the most characteristic defence of the scriptural aesthetic, that its adoption of rough and smooth, plain and majestic, served purposes of spiritual alchemy difficult to characterize, but evident in effect and, moreover, efficacious across a span of audience; ‘Whether we read David, Isaiah, or others whose stile is more sweet, pleasant and rhetorical’, explains Edward Leigh in 1654 ‘or Amos, Zachary and Jeremiah, whose stile is more rude, every where the Majesty of the Spirit is apparent’.23

There was general agreement that the different books of the Bible worked on different kinds of intellect. John Williams, in a sermon preached late in the seventeenth century, sums up a set of class-conscious distinctions that existed widely around the rude and unlearned status of many biblical writers: ‘But now though all the Parts of Scripture are not equally alike, but like the Inspired Writers themselves, of whom some were bred up in the Nurseries of Learning, and others fetch’d from the Fishery and the Sheepfold; yet are they all plain in the same essential Doctrine, and in which the Salvation of Mankind is concerned.’24 The social origins of the pen-men of scripture run deep in their assessment of and rumbling embarrassment at the nature of biblical rhetoric, with the proviso that the scriptures, seen in the round, approach the encyclopaedic, and what they lack in finesse, they make up for in the universality of their design:

He makes use of the Poetical Vein in David, the Oratory of an Isaiah, the Rusticity of an Amos, the Elegancy of a Luke, the Plainness of a Peter, the Profoundness of a Paul, to serve the common Design of instructing Mankind in the knowledge of God, and their Duty to him, without that Artificial Method which the Learned Part of the World expect to find, and think fit to observe.25

This deeply embedded presumption, that the Bible was coarse and troublingly plebeian, might also prompt a more bullish insistence that its rhetoric was unparalleled. Henry Lukin in 1669 argues that, in Isaiah at least, the nature of scriptural rhetoric trumps its classical correlates: ‘although there is nothing Pedantick in it, there is such a mixture of loftiness and gravity … that the flower and master-piece of Grecian Oratory is not to be compared with Eloquence of the Prophet Isaiah’.26 James Ussher insists it is written with ‘great simplicity of words, and plainnesse and easinesse of style, which neverthelesse more affected the hearts of the hearers, then all the painted eloquence and lofty style of Rhetoricians and Oratours’.27 Annotating the ‘poetic’ books—Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon—Arthur Jackson notes their inclination to mystery and complexity, a style that is intrinsically enwrought and filigree: ‘the stile and expressions of these Poeticall Books are farre more dark and difficult, and fuller of many knotty intricacies’.28

Such analysis often ascribed to the scriptures a set of qualities around its splendour, majesty, and, in particular, its sublimity, that it was a writing suited to the enormity of its subject matter, its sweep, and all-encompassing encyclopaedism of time, government, and spirit. The primary point of reference in such defences was Dionysius Longinus, the first-century Greek theorist of the sublime, who made passing reference to the ‘law-giver of the Jews’, Moses, as supposed author of the Pentateuch, whose account of the creation in Genesis was set in admiring contrast to the inadequacies of Homer and Hesiod.29 Sublimity works for Longinus by a rhetoric that does not so much persuade, as transport its audience by its emotional heft, an explanation that might easily be wrought to how the Bible worked its spiritual effects on readers, less by logic than by an irresistible magnetism. A related and much-quoted classical salve to the inferiority complex of a culture that felt itself bound more closely to the biblical, though more admiring of the Greek and Roman legacy, was Amelius the Platonist, a contributor to a third-century Neoplatonic revival around Plotinus, who attributed the ‘Wisdom of a Philosopher’ to St John, while still describing him as a Barbarian.30

Embarrassment with biblical style crescendos in the Restoration period, not coincidentally alongside the various ‘Augustinian’ redefinitions of taste that the period underwent. One of the most formative and extensive biblical defences did not, however, come from a dedicated literary or biblical theorist, but rather, from the natural philosopher Robert Boyle, whose Some Considerations touching the Style of the Holy Scriptures (1661) was both admired and influential.31 Boyle addresses a set of ‘cavillers’, whom he describes as ‘divers witty men who freely acknowledge the Authority of the Scripture [but] take exceptions at its Style … giving men injurious and irreverent thoughts of it’.32 While their complaints seemed to have floated widely in the intellectual and aesthetic aether, these cavillers have anonymity as almost a defining trait and (like the elusive early modern atheist) tended to make it into print only in refutation form. Boyle takes it upon himself to collect and dismiss a range of such criticisms, noting, for example, objections to the triviality of the Bible, exemplified in Jesus’s habit of answering different questions from those he was asked. Such intriguing complaints, be they Boyle’s own internal dialogue or part of some more ill-defined conversation, receive an answer, but rarely any attribution: ‘His oratory took a shorter Way than Ours can follow it in’, his parables designed to pass straight into hearers’ hearts, bypassing the need for reasoned dialogue.33

Among his defence strategies, Boyle throws rich metaphors back at the cavillers and ‘querulous readers’, noting, for example, that one ‘should remember that our Saviour could successfully imploy even clay and spittle to illuminate blind eyes’, in which analogy, the clay and spittle of biblical style, might not be gentile medicine, but nevertheless work upon the congenital human blindness.34 Answering the objection that the Bible was a work exhibiting a ‘disjoynted Method’—that it was, generically, rhetorically, or methodologically incoherent—Boyle answers with an analogy of a treasure banked in small coins, not being worth less, for being in such unsorted currency: ‘sure we should Judge that Man a very Captious Creature, that should take Exceptions at a Profer’d sum, onely because the Half Crowns, Shillings and Six pences, were not sorted in Distinct Heaps, but huddled into One’.35 Such a reply no doubt comes very close to conceding the disjointedness it seeks to defend against, and such concessions are very much a part of the strategy he adopts.

Addressing the stylistic deficit from another angle, Boyle notes that large portions of scripture have quite functional purposes, such as the delivery of the law, and that clarity at such moments demands that the work abstain from cloudiness and rhetorical dressing:

It will not be thought necessary that such parts of Scripture should be eloquently written, that the Supreme Legislator of the World, who reckons the greatest Kings amongst his Subjects, should in giving Lawes tye himself to those of Rhetoric, the scrupulous observation of which would much derogate from those two qualities so considerable in Lawes, Clearness and Majesty.36

There is in such a response exasperation that critics of the text would task God with more ornament. Boyle goes on to note that in our quotidian reading of ‘human’ works with similarly particularized functions—not only the law, but chemistry too—we do not ask for such embellishment:

How many of us can dwell on Lawyers, Physicians and Chymists Books, though oftentimes written in Terms as harsh and as uncourtly, as if those Rudenesses were their Design? And yet we can Neglect and scorn the Scripture, because in some Passages we there find the Mysteries and other Matters of Religion, deliver’d in a Proper and Theological style.37

He includes a quasi-anthropological account of stylistic deficiency, ‘that as to many passages of Scripture accus’d of not appearing Eloquent to European Judges, it might be justly represented, That the Eastern Eloquence differs widely from the Western’ with their ‘Dark and Involved Sentences … their Abrupt and Maimed way of expressing themselves’.38 Similar defences, tracing shifts in aesthetic styles across time, are not encountered too frequently, in a culture very much attuned to its own fine taste, but are met on occasion, as for instance in the controversial writing of Robert Ferguson in 1675, who likewise admits that what appeals to the seventeenth century may be relative:

If that which even among our selves is accounted Eloquence in one Age, ceaseth to be held so in another, why might not the Scripture stile have admirably suited the Genius of those times it was first calculated for, though it do not accord to our western Rules of Oratory? And who knows but that our Europaean Stile may be as little relished by the Asiaticks, as theirs is by us.39

Robert Ferguson, paired here with Boyle, appears initially to be another in a queue of defences of scriptural style, but he is, in fact, defending something different—the dissenter’s relationship to the Bible. This relationship was often deemed to be half-hearted, at best, and there was a rich and ambivalent tradition which viewed the Bible in its all too human prose as being simultaneously conduit to and obstacle to the spirit. Dissenters, separatists, and nonconformists are not noted for their engagement with aesthetics, which tends rather to be a response to classicisms, but such radicals, of various hues, do offer alternative and, at times, startling understandings of biblical prose, and it is to these responses that the last section of this essay turns. They do not (with Ferguson as the exception) attend to stylistic criticism of the Bible as such, but are nevertheless very much part of what the early modern period considered the problem of biblical prose.

Ferguson engages conspicuously with scriptural aesthetics, insisting that the Bible exhibited an enviable and inimitable pairing of form and function: ‘The Stile of the Scripture doth plainly breath of God. With what Brevity without Darkness; with what Simplicity without Corruption; with what Gravity without Affectation; with what Eloquence without Meretricious Ornaments; with what Plainness without Flatness or Sordidness; with what Condescensions to our Capacities, without Unsuitableness to the Subject Matter, is the Scripture written?’40 Occasionally, he concedes, the meaning may not be clear, but that, in turn, is either down to the subject matter being beyond our capacities or, in effect, the lack of good footnotes:

If there be at any time Obscurity in the Scripture-Stile, it is either from the Sublimity of the Matter declared, which no Words though never so easie in themselves, can help us to adequate Notions of: Or it is from some Reference to ancient Customs and Stories, which made the Expressions easie to the Age and Persons first concerned in them, though they may be Dark to us.41

Obscurity in an ancient text might demand that scholarship rectify the gaps in context, but it should not be deemed an intrinsic flaw. Ferguson insists that a reconfigured taste is necessary to appreciate the scriptures: ‘The pretence of want of Eloquence in the stile of the Scripture is a groundless, as well as a false calumny. And it ariseth first from a mistake of the Nature of True Eloquence, as supposing it to consist in a flourish of painted Words, or a smooth structure of periods.’42

In one regard, Ferguson could hardly be more measured in his defence of biblical style, but, nonconformist and occasional conspirator that he was, his writing attracted fierce attacks from some who saw it as a mere camouflage of orthodoxy, covering up the dissenters’ putative disdain for reason as a tool of religious belief.43 Ferguson does not intend to avoid entirely the nonconformist position that grace precedes understanding, that reading, even of the scriptures, does not offer a conduit to knowledge, so much as a reformulation into words of an ineffable spiritual infusion: ‘Grace both helps us to use Reason aright for the discovering the true meaning of Scripture Enunciations; and furnisheth us with a holy Sagacity of smelling out, what is right and true, and what is false and perverse.’44 Such a habit of smelling out the intricate meanings of the Word adds a curious, but perhaps still aesthetic, element to encounters with the Bible, as part of a hermeneutic arsenal that revels in the multi-dimensionality of the scriptural experience he expects:

There are no empty frigid phraseologies in the Bible, but where the expressions are most splendid, and lofty, there are Notions and things enough to fill them out. God did not design to endite the Scripture in a pompous tumid stile, to amuse our fancies, or meerly strike to our Imaginations with the greater force, but to instruct us in a calm and sedate way; and therefore under the most stately dress of words, there always lyes a richer quarry of things and Truths, Words being invented to express natural things and humane thoughts, the utmost signification they can possibly bear, proves but scanty and narrow, when they are apply’d to the manifesting Spiritual and celestial Objects.45

There is, in such a formulation, a disparity between what words—though in most stately dress—can express and the corresponding ‘spiritual and celestial Objects’. In such apparently inoffensive claims, that words were weak and might push only so far, to ‘the utmost signification they can possibly bear’, Ferguson was, in the estimation of his opponents, revealing his true anti-scriptural colours, part of a long-running dispute over the degree to which the human hand in the scriptures was grounds for suspicion.

The Holy Ghost, as is appropriate, employed ghost-writers—illustrious, inspired, occasionally stylish, but still human. They were not ‘authors’ in the emergent senses that were current in early modern understandings of the role. They were more routinely described as ‘pen-men’ of the text. These were, in some sense, scribes or conduits of the Word, but it seemed clear to early modern thinkers that their human roles, social status, and professions had a role in the texts they produced. If, in the writers cited earlier, this was a cue for discussing the literary qualities of their texts, for others it was evidence that the Bible itself had its ephemeral, or non-divine, aspects. The Independent, John Goodwin, in a late 1640s dispute with William Jenkin, argued that the human variables in penman, translator, and material production were such that a work liable to mutability, which could be torn and rent and mistranslated, could not be the immutable Word of God, nor even the foundation of religion: ‘every Bible, in what language soever, whether printed, or transcribed, whether consisting of paper, parchment, or other like materiall, was built and form’d, and made into a book by men. There is no point, letter, syllable, or word, in any of them, but is the workmanship of some mans hand, or other’, adding that he might defer to him if he could produce an angelic Bible, that if Jenkin had ‘a Bible that fell out of heaven, written, or printed without hands, he is desired to produce it for the accommodation of the world’.46 The Word of God is a wordless matter, according to Goodwin, not subject to the vicissitudes of Ink and Paper, but rather, the more impalpable workings of spirit. This argument involves distinguishing between a matter and substance that are substantially different from style: ‘though I willingly acknowledge … that the manner of the phrase and style of the Scriptures, is a rich character of their Divinity’, the Word subsists independently of any ‘gracious and super-added advantage of any thing in the Scriptures’.47

Such a claim is intricate, to put it kindly. The Bible, in phrase and style, contains something of the character of Divinity, he argues—it is, after a fashion, the diffusion of God on earth, but it remains an object like other objects, subject to the same decay. For some, its grandeur made it all the more liable to idolatry. This is an aspect of dissenting thought that runs deep, that reading the prose that contained the Word of God might be a distraction from the Word. In a trick by which the Bible was made to disappear, a strand of seventeenth-century thinking held that the biblical only served its purpose when it had become entirely transparent, a prose that had turned to scent and retained none of its material distraction.

The best example of such thought comes earlier in the seventeenth century when a dispute arose between Henry Ainsworth, who would become a formidable biblical commentator, and John Smyth, fellow separatists in the exile community in Holland.48 They engaged in a wrangle over whether ‘reading’, including reading the Bible during prayer, was a practice that might itself be sacrilegious. The argument centred on whether the Word, holy though it may be, might induce an idolatrous adoration of the book as object and whether this, in turn, might be as pernicious as image worship. Smyth issues a series of ‘objections for bookworship’, suggesting that the allure of the book was a will-o’-the-wisp. In treating the book reverentially, the reader was likely, he asserts, to misplace their spiritual focus from God to object, in the same way that gazing at a stained glass window, the beholder was liable to idolatry, in the opinion of many early modern Protestants. Translations, constituting a form of commentary, are no more than ‘apocrapha’ and have no sacred status. Smyth objects, moreover, to the ways in which the act of reading is itself a kind of ceremony—along with such hated acts as genuflecting before crucifixes: ‘books or writings are in the nature of pictures or images, and therfore in the nature of ceremonies, and so by consequent reading in a book is ceremonial’.49 This is a remarkable claim for a Protestant, seemingly rejecting the central reformation axiom that the Bible constituted the central focus of reformed religion and should be available in the vulgar tongue of the people.

Smyth’s idiosyncratic, if not unfathomable, argument aims, on the authority of the Bible, to keep the Bible away from any act of ‘spiritual worship’. He argues that the New Testament abolition of the law is supported by a precise set of injunctions against reading. When, for example, it is said of Christ in the temple that ‘he closed the book and he handed it to the minister and sat down’ (Luke 4:20), for Smyth, in this action, reading itself, ‘the ceremonie of book worship or the Ministerie of the letter’, is abolished. The apostles, we discover, had no books between Pentecost and the writing of the books of the New Testament, ‘7, 10 or 20 yeeres after Christs death’.50 Among his reasons, he states sarcastically, we must suppose ‘Bicause upon the day of Pentecost fyerie cloven tongs did appeare, not fiery cloven books.’51 Ainsworth, answering Smyth, defends the scriptures by collating the instances from the Bible in which reading is depicted positively, such as Moses’s command for a seven-yearly recitation of the law before the people. For Ainsworth, Smyth’s laudable concern to avoid idolatry has preposterous consequences: ‘so all reading must be abolished out of the Church; and that would the Divil faine bring to pass’.52

There is something wonderfully involuted in a scriptural argument against reading the scriptures, though many of Smyth’s arguments are sophisticated enough, centring on the instability of human languages in translation. For Smyth, it is not the sanctity of the original languages per se that is at stake, but rather, the need for a prophetic revivification of the gospel in any act of prayer and a sense that the Bible as object intrudes on this process, inhibiting the ethereal channels of prayer. The book itself, in the ideal reading act, would have to be a transparent medium of communication with God, with a catalytic purity, and this, for Smyth, can never be the case. With the merest psychological slippage of attention, idolatry—worship of an object other than God—was liable to occur.

At times, what seems to be a fierce anti-biblical rhetoric can be a hermeneutic manoeuvre, insisting on one or other mode of interpretation as being faulty or partisan, this being particularly the case when discussion of enthusiasm or idolatry comes into play. Jacob Bauthumley, shoemaker and Ranter, seems at points to be undermining any biblical foundations to religiosity with his insistence in The light and dark sides of God (1650) that the biblical text is no different from any other writing, going so far as to claim that ‘I must not build my Faith upon it.’ However, the fuller context of such statements is not anti-scriptural, but embodies the not infrequent inversion whereby the spirit infuses the Word with God’s meaning, rather than the Word itself—bare, empty, and carnal until awoken with spirit—being primary:

for take Scripture as it is in the History, it hath no more power in the inward man, then any other writings of good men, nor is it in that sense a discerner of the secrets … I must not build my Faith upon it or any saying of it, because such and such men writ or speak so and so, but from that divine manifestation of my own spirit … I do not go to the letter of Scripture, to know the mind of God, but I having the mind of God within, I am able to see it witnessed and made out in the Letter.53

Bauthumley’s rather beautiful text earned him fierce censure and punishment—he had his tongue burnt through with a hot iron—and is part of a longer strain of radicalism suspicious of the scriptures not in themselves, but insofar as they were liable to be turned into an idol: ‘neither is the fault in the Book, but in mens carnall conception of it; and seeing men make an Idoll out of it’, says Bauthumley:

and yet this is no detracting from the glory or authority of Scripture; because the Scripture is within and spirituall, and the Law being writ in my spirit, I care not much for beholding it in the Letter … that is the true Bible, the other is but a shadow or counterpart of it.54

We might not customarily suppose such writing to belong to the realm of aesthetics or that it has much to do with the history of prose. But such an idea—that the Word that turns to shadow upon being read properly—is not a great distance from the sublime language which, rather than persuade, manages to transport its readers out of themselves, and produces its vehement emotion by a strange aesthetic alchemy. The effect that the English of the Bible had on the literature of the seventeenth century is incalculable, intangible, and vast, and occurs almost despite itself. Neither the measure of the biblical sentence with its idiosyncratic cadences—as they were rendered in English—nor the hypnotic throb of its formulae and repetitions, nor indeed the archaic, oracular echo in its voice, were particularly amenable to seventeenth-century tastes and understanding of eloquence. Nevertheless, it was an era that theorized the emotional and affective workings of the Bible extensively, and whose grappling with scriptural prose tells us a good deal about its wider aesthetic conceptions.

Campbell, Gordon. Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611–2011 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Daniell, David. The Bible in English (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

Hamlin, Hannibal, and Norman W. Jones, eds. The King James Bible after Four Hundred Years: Literary, Linguistic, and Cultural Influences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Hessayon, Ariel, and Nicholas Keene, eds. Scripture and Scholarship in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006).

Hill, Christopher. The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution (London: Penguin 1993).

McCullough, Peter, Hugh Adlington, and Emma Rhatigan, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Early Modern Sermon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Norton, David. A History of the Bible as Literature, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Shuger, Deborah. The Renaissance Bible: Scholarship, Sacrifice and Subjectivity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

——— Sacred Rhetoric: The Christian Grand Style in the English Renaissance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

Tadmor, Naomi. The Social Universe of the English Bible: Scripture, Society and Culture in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).