Any study of the prose of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments faces a number of challenges, not least the fact that Foxe did not write much of his book. Contemporaries were well aware that the Acts and Monuments (A&M) consists to a large extent of extracts from other works, often reprinted verbatim.1 Indeed, as with Foxe’s incorporation of Marian martyrs’ letters previously edited by Henry Bull, Foxe sometimes repeated not only the text, but also the marginal notes of earlier works.2 Not surprisingly, any discussion of the style and authorship of the ‘Book of Martyrs’ is necessarily and vastly complicated by its textual and generic multiplicities.3 Nevertheless, John Foxe’s book made him an instant literary celebrity. By 1570, a handful of English writers, notably Geoffrey Chaucer, William Langland, and Thomas More, had gained fame for their writings. Yet, none of these figures attained the immediate and widespread popular acclaim that Foxe did as author of the ‘Book of Martyrs’. Although Foxe was a prolific author who wrote many works, including a highly regarded and influential commentary on Revelation, his other literary achievements were completely overshadowed by the Acts and Monuments. He became instantly identified with the ‘Book of Martyrs’ and his reputation utterly intertwined with it. As Patrick Collinson observed, ‘There are few instances in English literary history of a more complete fusion of author and text.’4

This situation is profoundly paradoxical since by most modern understandings of the term, Foxe was not an ‘author’ at all. Today, an author is popularly understood to be the person who composes a particular work; an author’s discourse is commonly valued for its originality, its reflections of its author’s particularities. By contrast, in the early modern period imitation of classical models, or imitatio, was highly regarded. While imitatio may encompass an admittedly wide spectrum of practices, ranging from what we might today consider loose translation to freely ranging transformations of one’s originals, it remains generally true that a writer’s claim to the status of ‘author’ was often built upon his or her imitation of authoritative texts such as Virgil’s Aeneid.5 Given the high esteem in which imitatio was held, originality—especially in matters pertaining to religion—was often suspect. Thus, the Catholic polemicist Robert Parsons criticized Foxe for questioning ancient authors and traditional authorities.6 In such a culture, the function of the author’s name is much more complicated than an indication of single, original authorship, as Marcy North’s work has shown.7 A name may authorize (in the sense of ratify or empower) a particular text; it may indicate strong and mutually beneficial associations between author and text; it may (as in the case of the popular editions of pseudo-Augustinian prayers published by Foxe’s printer, John Day) suggest traditional, but spurious, or even simply hopeful, linkages. The name of the early modern author, then, signifies in a number of ways other than a simple, straightforward claim to original composition.

Problems attendant upon the study of conceptualizations of authorship and stylistic imitation in the period are present a fortiori in the case of Foxe’s book. In a text that essentially deconstructs itself, it is not easy to discuss authorship, and it is futile to do so on the basis of prose style. But a study of the prose in the A&M may nevertheless shed light both on the work itself and on the early modern period’s complex understandings of authorship. Despite the fact that contemporaries knew Foxe had not originated much of his book’s material, beginning with the second edition of the ‘Book of Martyrs’, published in 1570, the title page proclaimed that the book was the work of ‘the Author Ihon Foxe’.8 This claim was reiterated in all subsequent unabridged editions of the A&M, occasionally emphasized in rubricated letters or large type. Traditionally, scholars have also stressed Foxe’s authorship of the A&M. Indeed, the standard biography of Foxe (in a striking demonstration of how closely its subject is identified with the ‘Book of Martyrs’) is titled John Foxe and his Book.9 In recent years, however, as appreciation for the work’s textual complexity has increased, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction and scholars are muting or minimizing assertions of Foxe’s authorship. But such approaches may inadvertently suppress the extent to which Foxe exerted editorial control over his materials. Throughout his recent monograph on Foxe, for example, John King refers to him, not as the author of the A&M, but as its ‘author-compiler’ or ‘compiler’.10 There is much to be said for this terminology, particularly since King is careful to state that Foxe ‘stood at the center’ of the project which created the ‘Book of Martyrs’ and that he ‘shaped the collection through the provision of prefaces, introductions to particular sections, transitions, marginal glosses, and varied forms of commentary and paratext’.11 Still, characterizing Foxe as a compiler runs the risk of circumscribing his role and obscuring our understanding of how the A&M was written.

King’s assertion that ‘we may best think of Foxe as an “author-compiler” in the manner of Raphael Holinshed’ epitomizes this danger, for the comparison is both instructive and misleading.12 The second of the two editions of Holinshed’s Chronicles was printed after Holinshed’s death and extensively revised by Abraham Fleming, a forward Protestant. But even in the first edition, Holinshed had to accommodate the editorial views of contributors such as John Stow, a religious conservative. As a result, Holinshed’s Chronicles are characterized by a pronounced multivocality, not least on religious topics and English church history.13 In contrast—despite factual inconsistencies, often chaotic chronology, and organizational lapses—all unabridged editions of the A&M speak with a single editorial voice, particularly on religious topics, that admits no doubts or qualifications. That editorial voice belongs to John Foxe. The legitimacy of his claim to authorize the ‘Book of Martyrs’ rests on the fact that the millions of words in it, despite their being written by authors across the centuries and the religious spectrum, support his viewpoint.

In what follows, we examine Foxe’s own bids for authority as articulated in the prefaces he wrote for the Acts and Monuments. We also consider the complexities of early modern authorship in a case such as that of Foxe’s book, so much of which was not written by him, but which nevertheless reflects his religious viewpoints quite precisely. Indeed, religious polemical purposes drive the prefaces’ assertions of a deferred and collective authority, as well as Foxe’s meticulous editorial labours. Throughout his book, the hand of a careful rhetorician is at work, a rhetorician who in early modern terms could claim the quite flexible label of ‘Author’.

Foxe’s prefaces to the A&M establish the book’s polemical, historical, and rhetorical goals. They also contain Foxe’s most explicit discussions of authorship. Perhaps the most apparent feature of these prefaces is simply their bulk. The A&M is announced with tremendous fanfare. Its multiple prefatory addresses resemble the ‘extensive supplemental material’ published in humanist editions of classical Latin texts.14 Foxe carefully revised, rearranged, added, and excised prefaces over each of the four editions published during his lifetime (in 1563, 1570, 1576, and 1583). His careful attention to this material bespeaks its importance to him. Like early modern prefaces more generally, Foxe’s prefaces stake claims to authority both for Foxe and for his book.15 In his prefaces, Foxe exercises careful rhetorical control and gives extended attention to writerly concerns such as the status of rhetoric, the importance of decorum (suiting style to matter), and the dangers of sophistry. He also makes precise use of rhetorical figures and tropes both to structure and to illustrate his work’s claims. Finally, the prefaces reveal Foxe’s concern with authorship, conceived primarily not as the origination of discourse, but as the rhetorical ability to present the matter at hand in the most effective and affecting way. As Foxe articulates and justifies the purposes behind his book, he is concerned with questions of style and specifically with decorum: how ought martyrs to be honoured in his printed work? How may their stories be set forth to godly purposes? Foxe’s English prefaces wrestle with the proper uses of rhetoric in ecclesiastical history and labour to establish a deferred and collective form of authorship, one in which Foxe himself is meant to recede behind the authority of the various materials and voices he presents, even as that recession itself is a carefully managed rhetorical feat.16

Foxe’s preface, titled in 1563, ‘A declaration concerning the utilitie and profite of thys history’, and in 1583, simply ‘The utilitie of this story’, has been discussed with respect to the shifting genres Foxe imagines for his book.17 But it is also important to note the rhetorical categories in the preface’s shifting titles. Foxe’s preface claims authority for his work on the basis of its utility and profit; eloquence emerges as a secondary matter—not a matter of secondary importance, but one that follows and derives from the importance of the material being discussed. The preface’s stance on style shares some similarities with that in the fourth book of Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana. There, Augustine classifies the styles of particular biblical passages and selections from patristic figures according to the purpose a passage seems to have—whether it be teaching (plain style), praising or blaming (middle), and exhortation (grand)—and not according to stylistic features primarily. For Augustine, purpose and function are primary concerns; while for Cicero, the grand style is the queen of styles, for Augustine, the plain style often takes pride of place because of its teaching purpose. Similarly, the widely influential reformer Philip Melanchthon defended appropriate eloquence while insisting that style should be firmly in the service of clear instruction.18

Foxe’s preface, too, insists that style should emerge from, be subordinate to, and work in harmony with instructional purposes. The many revisions he makes to this preface between 1563 and 1570, often stylistic improvements on the original, indicate that its discussion of style, eloquence, and decorum was important to Foxe. In the 1563 and 1570 prefaces, Foxe begins in a style heavily reliant on pairs, balanced phrases, and careful qualifications. These features resemble both those of classical Latin’s middle style and William Tyndale’s heavy use of binarisms in his translations of scripture.19 For example, in 1563 Foxe writes that he fears he may seem to have in hand matter ‘superfluous and needeles’, and that given the contemporary glut of printed books, ‘manye good men doo both perceive, and inwardlye bewayle this insatiable gredines of wryting and printing’.20 The preface then claims that ‘ornaments of wyt and eloquence’ ought to be applied to the worthiest subjects—martyrs for the true faith.21 By the preface’s end, Foxe’s style approaches the grand style of the peroratio, the rousing climax to a classical oration. The preface thus both considers and models different stylistic registers, establishing Foxe’s firm preference that style follow function while endorsing and demonstrating appropriate eloquence.

Foxe’s preface begins by worrying over the excessive number of books in the world. His opening is an ethical bid, a captatio benevolentiae (capture of the readers’ good will): he, like ‘manye good men’ (1570: ‘many’) perceives and regrets the excesses of print. The burden of authorship seems heavy, as he worries over how he might be censured for presuming to take on the persona of a ‘writer’. Here is the 1563 text:

I perceyved well how learned this age of ours was, and I could not tell what the secrete and close judgementes of the Readers would determine, if sodaynly one should prease in with other, taking upon hym the person of a wryter in the syght of al men, which were not sufficiently furnished with such ornamentes and graces as are requisite to the accomplishing of so waighty an endevour, which could not utter some matter excellent and synguler, and joyning thinges together not onely great, but also necessarye for the condition of the tyme with lyke gift of utterance satisfie and encrease the industry of the learners, the utility of the studious, and the delight of the learned. Which vertues the more I perceived to be wanting in me, the lesse I durst be bold to become a writer.22

The role of ‘writer’ is imagined as a ‘person’, a persona one may inhabit, or be inadequate to take up, as the case may be. In an instance of the humility topos, a common feature of Renaissance prefaces, Foxe writes that he lacks what is needed for such a role: the ability to teach and delight, to suit eloquent ‘utterance’ to the ‘matter’ at hand. In the 1570 preface, his humility is asserted more strongly and with more style in carefully balanced phrasing: ‘neither could I tell what the secrete judgements of readers wold conceave, to see so weake a thing, to set upon such a weyghty enterprise’.23 This humble beginning is itself what Cicero advises in De inventione for the openings of speeches: the orator should claim authority through apparent modesty and seemingly spontaneous eloquence (as exhibited in the 1570 preface’s figure of parison: the use of corresponding structures in a series of phrases or clauses). The preface will go on to justify Foxe’s act of writing explicitly, using the utility and profit of reading about martyrs to embolden authorship.

Foxe defends his work’s promulgation using religious and rhetorical arguments. Specifically, Foxe slightly modifies classical rhetoric’s understanding of the functions of the plain, middle, and grand styles. For Cicero, and for the author of the Rhetorica ad Herennium, the three classical styles were generally associated with three purposes: to teach (plain style), to delight (middle style), and to move (grand style).24 In Foxe’s 1563 list of purposes for his work (to satisfy and increase learners’ industry, the utility of the studious, and the delight of the learned), teaching occupies two spots in the list and delight only one. He tips the balance towards the instructional (plain), downplays the delightful (middle), and seemingly omits anything that would correspond to the grand style. In the 1570 edition, Foxe combines the first two instructional purposes: he feels he is insufficient ‘to serve the utility of the studious, and the delight of the learned’.25 His beautifully balanced revision states that he lacks the literary skills for either teaching (plain style) or delight (middle).

The grand style is not without place, however, nor is Foxe’s purported humility entirely ingenuous. In the 1570 preface, Foxe inserts a phrase lamenting his inadequacy to the matter at hand: he is ‘not sufficiently furnished with such ornamentes able to satisfie the perfection of so great a story’.26 Foxe will build towards the highest rhetorical goal—that of moving the listener or reader to virtue, or to right judgement or decision—within the next page, after teaching has been firmly established as the basis of all he does, and after the ‘perfection of so great a story’ has been shown to merit eloquent treatment. What seems to overcome Foxe’s stated fear is the profit and utility of the matter discussed. In 1563, Foxe writes that if we are willing to ‘decke, trym, and set … out with the ornamentes of wyt and eloquence’ worldly or secular affairs, how much more should we ‘accept and embrace’ the lives and doings of martyrs; in 1570, acceptance and embracing give way to conserving ‘in remembrance’.27 Martyrs’ words and actions don’t ‘delight the eare’ so much as ‘garnish the lyfe’ (1563 and 1570); they give examples and instruction, beyond mere literary pleasure.28 Foxe’s preface reorients rhetorical goals: delight, the motive often associated with the middle style, is defined, not as merely stylistic delight, but as moral reform, even moral beauty. What is most appropriately decked, trimmed, or garnished is the reader’s ‘lyfe’ itself, not just the writer’s style. The 1570 preface stresses the martyrs’ affective power even more strongly: rather than the ability to ‘enstruct’ (1563) men in godliness, for example, stories of martyrs ‘encourage’ men to godliness.29 The grand style’s function of moving the reader appears in this revision, as does a hint of Foxe’s affinity for what Janel Mueller has called a Tyndalian affective rhetoric. Simply writing history (for Foxe) or translating scripture (for Tyndale) is not enough: a translator’s or author’s style must also inspire affective readerly responses.30

For Foxe, eloquence has a place, provided that the subjects upon which it is lavished are deserving. Foxe finds precedent for his work in the hymns and songs of Prudentius and St Gregory of Nazianzene, superior in Foxe’s judgement to Pindar’s odes precisely because of their sacred matter. Similarly, in 1563 Foxe insists upon the eloquence of ancient orations on martyrs: ‘What availeth here to make rehersal of the eloquent orations of the most eloquent men, Ciprian, Chrisostome, Ambrose, and Hierome, and never more eloquent, then when they fell into the commendations of the godly Martyrs?’31 Anderson has recently discussed this preface’s worry over the inundation of books in the context of the work’s anxiety over print, arguing that the work uses print against itself, to give the illusion of unmediated access to archival materials.32 What is striking in this preface, however, is that Foxe’s ostensible anxieties about print are resolved through a turn to orality: Foxe likens his work to that of classical rhetorical orations and adapts classical rhetorical purposes to suit his own—namely, to move people towards godliness through the exempla of the martyrs. Foxe will himself embrace the eloquence he praises in patristic orations by the preface’s end, where the elevation of his style articulates a call to imitation, collective remembrance, and the publishing of martyrs’ lives. This is grand-style exhortation (movere—that is, to move) in Foxean terms.

Over the course of this preface, Foxe establishes his subject’s worthiness and moves from ostensible fear over assuming a writer’s ‘persona’ towards a cooperative form of authorship, or at least a call for the reader to begin a cooperative effort with the ‘writer’, garnishing his/her life so that martyrology may yield the proper fruit. Fittingly, the first-person singular pronoun of the preface’s opening expands to a first-person plural in a passage that remains stable from 1563 to 1570: ‘let us not faile then in publishing and setting fourth their doinges, least in that point we seme more unkinde to them, then the writers of the primitive church were unto theirs’.33 By the preface’s end, Foxe reveals the fruit and utility to be taken from the martyrs’ stories as he urges his readers, along with himself (‘us’), to learn from their examples to suffer patiently, forgive, behave charitably, neglect worldly things, and be willing to suffer should we be called to do so. Here, then, is the ‘utility and fruit to be taken of this history’ that justify the name of ‘writer’ for Foxe himself, the matter that both deserves all the ornamentation eloquence can offer and subordinates the mere ‘delight’ of eloquence to godly profit.

In Foxe’s other prefaces, he maintains something of this first-person plural, so to speak, as he claims authority for his text in ways that deflect attention from Foxe himself. That is, Foxe presents his work as authoritative precisely because it is not original. Two prefaces added to the 1570 edition, for example, list ‘The Names of the Authors alleged in this Booke, besides many and sondry other Authors whose names are unknowen, and also besides divers Recordes of Parlament, and also other matters found out in Registers of sondry Byshops of this Realme’, as well as ‘The names of the Martyrs in this booke conteined’, from the time of John the Baptist to the present. These lists were added after Foxe’s 1563 edition had come under fire from Catholic polemicists such as Thomas Stapleton and Nicholas Harpsfield for what they deemed heretical departures from the true church’s history and authoritative teachings; Foxe counters that his book speaks with and for ‘Authors’ and martyrs whose historically continuous testimony is to be trusted, claiming collective authorship under the sign of his name.34

Because Foxe’s work labours to disclose divine patterns behind history’s particularities, one of his greatest authorizing claims is historical precedent: that the martyrs whom he commemorates are early Christian martyrs’ worthy successors. In the 1563 preface ‘A declaration concerning the utilitie and profite of thys history’, Foxe uses anaphora (the beginning of successive sentences or phrases with similar or identical words or phrases) to mark this continuity:

Those standing in the foreward of the battell, did receive the first encountre and violence of their enemies, and taught us by that meanes to overcome such tiranny. But these as spedely, lyke olde beaten soldiours did winne the field in the reward of the battaile. Those did, like famous husband men of the world, sow the fields of the church, that first lay unmanured and waste. And these with the fatnes of their bloude did cause it to battell and fructifie.35

Here, and in the lists of ‘Authors’ and ‘martyrs’ whose voices are added to Foxe’s own, lies evidence of Foxe’s fundamental conservatism: Protestants represent continuity with ancient Christian tradition, while Catholics innovate and presume upon the idiosyncrasies of particular episcopal authorities. Consider, for example, Foxe’s criticism of Innocent III’s papal reign in his preface ‘To the true and faithfull congregation of Christes universall Church’: ‘Whatsoever the Byshop of Rome denounced, that stode for an oracle, of all men to be received without opposition or contradiction: whatsoever was contrary ipso facto it was heresy.’36 Foxe’s deferral of authority has rhetorical purpose: it is to move him out of centre stage, to eliminate the perception of originality, and to gain authority precisely from his deference to other authorities.

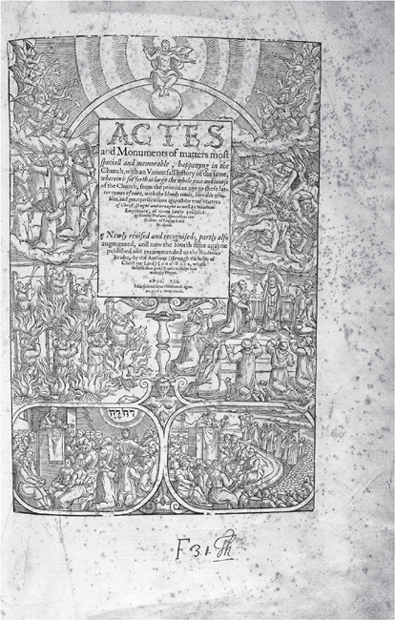

The greatest textual authority for Foxe’s culture was, of course, the Bible. For Foxe, as for John Bale, scripture, and especially the Book of Revelation, illuminates history.37 Indeed, the A&M may be read as an extended commentary on the Bible and on Revelation in particular, an ecclesiastical historical companion to and development of Bale’s The Image of Two Churches (Fig. 31.1). Foxe’s prefaces make clear his indebtedness to the Bible, as well as his belief that his book is an historical dilation upon biblical themes. Like a medieval commentator, Foxe’s authority in the preface, entitled, ‘To all the professed frendes and folowers of the Popes procedynges: Foure Questions propounded’ (added in 1570), stems from that of the sacred text upon which his preface expands. The preface links Foxe’s book to scriptural authority, as each of its four questions is derived from a particular biblical passage. For example, Foxe’s first question, whether the church of Rome is like Mount Sion, is clearly to be answered negatively. For Foxe, the Roman church has none of Mount Sion’s qualities, as outlined in Isaiah 11: ‘The wolfe shall dwell with the Lambe, and the Leopard with the Kid: The calfe, the Lyon, and the Sheepe shall feede together, and a young child shall rule them. The Cow also and the Beare shall abyde together, with their young ones, and the Lyon shall eate chaffe and foder lyke the Oxe.’38 Foxe argues that Rome is not this church with a sentence whose content and structure shape the biblical passage’s relevance to the history he narrates: ‘in the sayd Church of Rome is, & hath bene now so many yeares such killyng and slaying, such crueltie & tyranny shewed, such burnyng and spoylyng of Christen bloud, such malice and mischeif wrought, as in readyng these histories may to all the world appeare’.39 In place of Isaiah’s discordia concors, its pairs of reconciled opposites—wolves and lambs, leopards and kids—Foxe uses pairs that merely iterate discord: killing and slaying, and burning and spoiling. Foxe’s history is presented as if it acted neutrally, without any one person’s explicit design, as in the last clause, which curiously lacks an explicit agent: ‘as in readyng these histories may to all the world appeare’. Yet, his rhetorical knowledge and care are everywhere present and indeed, often flaunted. In a preface added in 1570, ‘To the True and Faithfull Congregation of Christes universall Church’, Foxe intertwines biblical language with rhetorical precedent, the Reformation with the Renaissance, so to speak, as he protests against adversaries like Harpsfield: ‘such accusers must beware they play not the dogge, of whom Cicero in his Oration speaketh, which beyng set in Capitolio to fray away theeves by night, left the theeves and fell to barke at true men walkyng in the day … to carpe where no cause is … to swallow camels, and to strayne gnattes: to oppresse truth with lyes, and to set up lyes for truth’.40 Foxe uses the resources of classical rhetoric (Cicero’s oration) and biblical allusion (Matthew 23:24: ‘Ye blind guides, which straine out a gnat, and swallowe a camell’) to defend his book with the most authoritative works he can muster.

FIGURE 31.1 John Foxe, Actes and Monuments of the Christian Church (1570), title page. The title page of the A&M pictures and contrasts the True and the False Churches, illustrating Foxe’s indebtedness to John Bale’s The Image of Two Churches.

In his preface to the Queen, which undergoes radical changes between the 1563 and 1570 printings, Foxe’s rhetoric again indicates both his care in shaping his claims to authority and his boldness in asserting his book’s place just beneath that of scripture. In 1563, the preface develops elaborate parallels between Constantine, the first Christian emperor and patron of the ecclesiastical historian Eusebius, and Elizabeth I, the new Protestant Queen of England and dedicatee of the ecclesiastical historian John Foxe. Foxe uses corresponding verbal structures (parison) to create order and pattern both within the historical example of Constantine and Eusebius’s relationship and between Constantinian days and his own. Surveying Constantine’s era, for example, Foxe writes that he does not know whom to praise the most, ‘the good Emperour, or the godly Byshoppe: the one for his Princely proferre, the other for his godly and sincere praise to God for the marvelous workes and syncere peticion. The Emperour for his rare and syngular affection in favouring and furtherynge the Lordes churche, or the Byshoppe in zealyng the publique business of the Lorde.’41 Similarly, Foxe uses parison to draw Elizabeth and Constantine together: ‘I could not enter mention of the one [Constantine], but must nedes wryte of the other [Elizabeth].’42 Foxe’s rhetoric performs his desire ‘to compare tyme with tyme, and place with place’, and not, incidentally, to hint that his history ought to be accepted and honoured as were Eusebius’s labours.

The 1570 preface’s rhetoric proclaims its very different purpose. Gone are the carefully balanced sentences, gone the heavy use of parison. Instead, cumulative sentences pile phrases upon phrases, mimicking and (Foxe hopes) exposing the furious assaults his work has suffered. Notoriously, the ornamental ‘C’ at the preface’s opening no longer begins the word ‘Constantine’, but rather, ‘Christ’, whose precepts Foxe hopes Elizabeth will follow a bit more energetically than she has to date (Fig. 31.2). Foxe’s attitude towards rhetoric, like his attitude towards his queen, seems to have darkened slightly. Foxe heatedly accuses Catholics of using sophistry and tries to separate proper rhetoric from sophistry. His Catholic detractors have spared ‘no cost of hyperbolicall phrases’, attacking his book with

the like sort of impudencie as sophisters use somtymes in their sophismes to do (and some times is used also in Rhethoricke) that when an Argument commeth against them which they can not well resolve in dede, they have a rule to shift of the matter with stout words and tragicall admiration, wherby to dash the opponent out of countenaunce, bearing the hearers in hand, the same to be the weakest and slendrest argument that ever was heard, not worthy to be aunswered, but utterly to be hissed out of the scholes.43

In danger of overlapping sophistry and rhetoric (‘sometimes is used also in Rhethoricke’), Foxe’s sentence, by the end, dismisses sophistry from learned consideration (‘hissed out of the scholes’) in balanced verbal phrases (‘not worthy to be aunswered, but utterly to be hissed’).

Still, parison dominates only at the preface’s end, and in a way that both indicates Foxe’s recovered balance and pushes his godly agenda. Foxe offers a sideways rebuke of Elizabeth, writing that he has heard of Elizabeth’s ‘zeale’ to ‘furnish all quarters and countreyes of this your Realme with the voyce of Christes Gospell, and faithfull preachyng of his word’. But he notes in parentheses—‘(speedely I trust)’—that her reputed zeal has not yet produced much fruit. Foxe reintroduces parallel structure in order to present his work as driving the dissemination of the gospel he so desires: ‘like as by the one [scripture] the people may learne the rules and preceptes of doctrine: so by the other [the ‘Book of Martyrs’] they may have examples of Gods mighty working in his church, to the confirmation of their faith, and the edification of Christian life’.44 Foxe’s work—the second part of the parison—complements Elizabeth’s stated aims, but given the qualification Foxe inserts just prior (‘speedely I trust’), the logic of the sentence is driven by the parison’s second half: the dissemination of martyrs’ examples is to push the Queen to disseminate the gospel.

FIGURE 31.2 John Foxe, Actes and Monuments of the Christian Church (1570), image of Elizabeth as Constantine (p. 1). This famous woodcut displays an enthroned Elizabeth within an ornate capital ‘C’. In the first edition of the A&M, this was the beginning of the word ‘Constantine’, in the preface to the Queen, and linked the two sovereigns together. In the second edition, the capital ‘C’ was retained at the beginning of the preface, but now it began the word ‘Christ’, as Foxe had quietly discarded the comparison of Elizabeth to the first Christian emperor.

The preface’s penultimate sentence uses structured repetition in the form of a chiasmus to similar ends. The two examples of chiasmus (a figure that takes the shape of an ‘x’: A:B, B:A) are highlighted below. Foxe writes that ‘observing and notyng’ the ‘excellent workes of the Lord’ in ‘historyes, minister[s] to the readers thereof wholesome admonitions of lyfe, with experience and wisedome, bothe to knowe God in his woorkes, and to worke the thyng that is godly: especially to seke unto the sonne of God for their salvation, and in his fayth onely to finde that they seeke for, and in no other meanes’.45 Foxe’s theology is carefully woven into his prose: human knowledge and action are drawn to and circumscribed by God. Faith in Christ is the fulcrum of the second, looser, chiasmus, framed by a seeking whose target and origin is the centre of the chiasm (itself a Christic figure, by virtue of its ‘x’ or cross shape). The order of the chiastic figures may also be significant: through studying Foxe’s ecclesiastical history, readers will know God in his (historical) work, and thereby learn the heart of the gospel: to seek salvation sola fide. Whether Elizabeth’s zeal ever manifests itself as it should, Foxe’s history will push towards godly evangelization.

Given the function of these chiastic figures—which both proclaim Foxe’s rhetorical skill and defer authority to Christ, upon whom the second chiasmus turns—the slight revision of the 1583 title page’s proclamation of Foxe’s authorship is fitting. The 1583 title page claims that the book is revised and augmented ‘by the Authour (through the helpe of Christ our Lord) John Foxe, which desireth thee good Reader to helpe him with thy Prayer’. The parenthetical assertion offers a deferral of authority that seems characteristic of the assertions made in Foxe’s prefatory material: Foxe is ostensibly the author, but importantly, not the originator of the history he structures and presents. The bid for collectivity—‘good Reader … helpe him with thy Prayer’—also reflects the claims Foxe’s prefaces have staked: he does not stand alone, a solitary originator of discourse, but instead, as a ‘writer’ authorized by the truths he perceives in the histories he shapes.

We also see Foxe the rhetorician in his careful construction of the work, whose ideological and intellectual uniformity was achieved through close editing. Foxe frequently emended texts before incorporating them in his book, a proclivity manifested in his Latin martyrologies, precursors of the A&M. For example, when Foxe reprinted, in his Commentarii, a list of John Wiclif’s responses to questions from Richard II and his councillors, he deleted passages in which Wiclif declared his belief in purgatory.46 Foxe employed a similar discretion throughout the first edition of the ‘Book of Martyrs’, as when one Lollard’s denial of Christ’s Resurrection and another’s denial of his Incarnation were both airbrushed out of Foxe’s version of their interrogations.47 Foxe occasionally rewrote unguarded utterances of those whom he regarded as proto-Protestants. Margery Baxter’s claim, made in 1429, that the Lollard leader William White was a great saint in heaven and a most holy doctor, was altered to the assertion that he was ‘a good and holye man’.48 Foxe also modified Thomas Butler’s declaration, in 1488, that Christ’s death saved all sinners from eternal punishment to read instead that ‘no faithfull man should abide any payne after the death of Christ for any sinne because Christ died for our sinnes’.49 From the start, Foxe not only compiled documents, but also closely read them and shaped them to suit his purposes.

This close editing was greatly intensified in the second edition, whose title page, significantly, was the first to identify Foxe as the work’s author. Catholic writers’ attacks upon the first edition prompted Foxe’s almost obsessively painstaking editorial oversight.50 Perhaps surprisingly, Foxe was stunned and (less surprisingly) bitter about the vehemence and ubiquity of these criticisms. He mordantly commented in the second edition’s dedication that

A man would have thought Christ to have bene new borne agayne and that Herode with all the Citie of Jerusalem had bene in uproare. Such blustering and styrring was then against that poor book through all the quarters of England, even to the gates of Louvaine: so that no English papist in all the Realm thought him selfe a perfect Catholike unlesse he had cast out some word or other to give that book a blow.51

Foxe took these attacks both personally and seriously. Considerable sections of the second edition were devoted to direct rebuttals of his Catholic critics.52 Researchers were pressed into service to supply Foxe with manuscript evidence to counter attacks on his work.53 As the ramparts were being extended, vulnerable points were fortified and cracks in the walls filled. Material reprinted from the first edition or introduced to the second was rigorously edited to remove errors.

Foxe went to considerable lengths to correct factual mistakes. For instance, the text of the second edition stated that the villages of Merindol and Cabrieres, where terrible massacres of Waldensians had taken place, were in ‘the valley of Angrone’. Someone had conflated the sites of different atrocities inflicted on separate groups of Waldensians: Merindol and Cabrieres are in Provence, while the Angrogna valley is in Piedmont. However, Foxe soon noticed the mistake. The erroneous words ‘in the valley of Angrone’ were crossed out with a pen-stroke in every copy of the second edition.54 Moreover, eleven pages later, Foxe mentioned the earlier mistake and assured readers that it had been ‘rased out with pen’.55 This incident underscores Foxe’s determination to eliminate demonstrable inaccuracies. It also reveals how closely he proofread the 1570 edition’s text. In order to catch the mistake within eleven pages of its first having been printed, Foxe must have been reading the copy soon after it came off the press. (As a rough calculation, a single press could print about two pages of a book a day; since three presses were used simultaneously to print the second edition, the mistake was detected and corrected within, at most, a week, and very probably, a few days.56)

Foxe’s editorial zeal meant that material reprinted from the first edition was fine-combed for mistakes. In 1563 a compositor apparently had problems reading a transcription of the examinations of John Fortune, a Marian martyr. In the first edition, Fortune is quoted as saying (in reference to the Great Schism) that the popes were ‘spiritual men for in xvi days ther wer thre popes’. In the second edition, this passage was silently corrected: the popes were ‘spitefull men for in xvii monethes there were three popes’.57 At times, these corrections were minute enough to border on the pedantic. The first edition records that the Marian martyr Robert Ferrar was burned in the city of Carmarthen; the second edition states that Ferrar was burned in the town of Carmarthen.58

This meticulous editing was not driven by an abstract desire for accuracy and exactitude, but by polemical exigencies, primarily the need to appear completely accurate and thus deprive confessional opponents of any foothold when they attacked the book’s veracity. In the A&M accuracy is the servant of confessional polemic and Foxe’s painstaking emendations are often intended to conceal inconvenient facts. As we have seen, this was Foxe’s practice in the Latin martyrologies and in his first edition. But in the second edition, in response to the confessional attacks on his first edition, Foxe’s ‘corrections’ were far more thorough.

The examinations of the Marian martyr John Careless provide an excellent example. Foxe printed them in his first edition, but their frequent references to doctrinal disputes among Marian Protestants validated Catholic charges of Protestant divisiveness. In the second edition, after informing the reader that he was omitting ‘nedeless matter’, Foxe cut over three pages describing the disputes among Marian Protestants over predestination.59 All told, Foxe’s strategic omissions reduced the original examination’s six pages to two.60 Foxe’s emendations also operated at a more detailed level. Repeating an account printed in his first edition of a book burning that took place in 1557, Foxe, in his second edition, omitted a passage in which Marian authorities compared their actions to the orthodox emperors Theodosius and Valentinian burning heretical books.61

Foxe was particularly concerned about some of the material that had been translated from Latin for his first edition. These translations were not Foxe’s, but the work of anonymous translators; sometimes, perhaps because of the haste with which the first edition was printed, they contained careless errors that demanded correction. Misled by the same verbal similarity that inspired Gregory the Great’s famous pun, one translator rendered the phrase ‘potestate angelus altiori’ as a ‘higher power unto England’. In the second edition, this was corrected to ‘a power higher than aungels’.62 Often, the earlier Latin translations were emended to remove passages that Catholic critics could use against Foxe. For example, the translation of Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini’s account of the Council of Basel in the first edition was, if anything, too faithful to the original to suit Foxe, who wanted to present the council’s anti-papal faction in the best possible light. Thus, St Augustine’s famous dictum, that he did not believe what was in scripture unless it was vouched for by the authority of the church, was quoted by the anti-papalists at the Council in support of their arguments. This embarrassing text—a favourite among Counter-Reformation Catholics—was included in the first edition, but unobtrusively dropped from the second.63 The translator had been alert enough to omit Piccolomini’s description of Louis d’Aleman, Archbishop of Arles (the leader of the anti-papal faction), collecting relics of saints and bringing them to the Council in a moment of crisis. In the second edition, Foxe added a sentence stating that d’Aleman ordered members of the Council to pray; he simply did not mention that they were praying to the saints for their intercession.64 Foxe’s meticulous, almost finicky, attention to detail ensured that his role in the volume went beyond that of a mere compiler.

Foxe’s precise editing extended beyond deleting passages to rewriting them. The second of three articles charged against the Lollard William Taylor stated that he believed that ‘Christ must not be worshipped because of his humanity.’65 Foxe retained the passage, but tendentiously changed it to ‘No humaine person is to be worshipped by reason of his humanity.’66 This rewriting could be done systematically, yet unobtrusively, as Foxe carefully altered key passages within a text he reprinted.67 Sometimes, however, Foxe’s rewriting of a text transformed it almost beyond recognition. For example, when Foxe reprinted Patrick’s Places, a translation of the Scottish evangelical Patrick Hamilton’s Loci communes, first printed in 1531, the original text underwent a sea change. Foxe made the work more explicitly predestinarian. He also recast much of the text into syllogisms, giving the theological arguments a more formal structure. Above all, Foxe inserted his own commentary—as long as the original text itself—into the version which appeared in the ‘Book of Martyrs’.68 Readers of the A&M may have thought that they were reading a piece by Patrick Hamilton, but Foxe was as much the author of the version of Patrick’s Places that appeared in the ‘Book of Martyrs’ as the Scottish evangelical had been.

Many of Foxe’s revisions paid as much attention to style as content. His oversight of material translated from his Latin martyrologies sometimes involved detailed changes in wording to express the same essential thought in more felicitous language. In the Rerum, Thomas Cromwell, who would become one of the A&M’s heroes, was described as ‘vir obscuro loco natus’. In the first edition, this was rather harshly translated as ‘a man but of base stock and house’. The second edition transforms the statement into ‘of simple parentage and house obscure’.69 Foxe also cast an eagle eye over material sent to him by informants. Although Foxe frequently seems to have passed material to the printing house verbatim, his pen always hovered over the arriving texts. An account of a Marian persecutor’s sudden death—John Williams, the chancellor of the diocese of Gloucester—was sent to Foxe, headed ‘The straunge and hasty death of Doctour Wyllyams’. Foxe passed it along to the printers, only pausing—in order to heighten the sense that this death was God’s judgement—to replace the word ‘hasty’ with ‘fearful’.70

While the second edition was being printed, Foxe was particularly concerned to moderate some of the caustic language used against Catholics in his first edition. Paradoxically, this was also a response to the Catholic barrage against his work. Foxe was aware that polemic, like revenge, is best served cold: in order to rebut these attacks successfully, he needed to maintain the appearance of calm, dispassionate accuracy. To this end, Foxe systematically toned down passages that were egregiously inflammatory or abusive. Thus, the first edition’s disparaging of Bishop Bonner’s ‘doggs eloquence’ became a criticism merely of his ‘rhetoricall repetition’.71 Similarly, a description of Bonner bearing ‘great envy and malice’ towards Cranmer was amended to his bearing ‘no great good will’ towards the archbishop.72 And a declaration that some Marian martyrs were ‘brought unto the bloudy seate of the Consistorye’ was changed to ‘brought to the open Consistory’.73

These changes not only demonstrate Foxe’s thorough, indeed, microscopically close, editing, but also his sensitivity to prose style. The most extreme examples of this sensitivity are passages that were inventions of Foxe and others. Such inventions were infrequent and more likely to occur in Foxe’s Latin martyrologies than in the A&M. One startling example is Foxe’s claim, first made in his first Latin martyrology, but repeated in all editions of the A&M, that Reginald Pecock, a prominent anti-Lollard writer, declared that Christ’s body was not present in the sacrament. All of the evidence suggests that this surprising statement is entirely Foxe’s invention.74 Foxe also composed a speech for the martyr William Gardiner to deliver to the King of Portugal, justifying his iconoclasm.75 In these cases, it is clear that the passages were Foxe’s invention. In other cases, where demonstrably fictitious material was presented—such as Latimer’s celebrated last words, the last words of the martyr James Bainham, and even an account of a shipwreck putatively suffered by William Tyndale—biblical and hagiographical tropes were borrowed and adapted to glorify Protestant martyrs.76 Whether Foxe invented these incidents or simply repeated, with willing credulity, what others told him is uncertain.

Rewriting passages was the most obvious way Foxe shaped the ‘Book of Martyrs’, but it was not the only one. Foxe wrote the marginal notes for the A&M himself, providing direct commentary on the text.77 Thus, Foxe’s book was mediated for its readers through several interpretative levels involving both direct commentary and unobtrusive emendation. The number of marginal notes vastly increased between the first and second editions as Foxe responded to his critics. For instance, seven marginal notes accompanied the story of William Tyndale in the first edition; in the second edition there were 102.78 Foxe’s account of John Hooper required only twelve marginal notes in the first edition; in the second edition it had 114.79 And the life and martyrdom of Thomas Cranmer was garnished with eighty-five marginal notes in the first edition; seven years later, there were 380 marginal notes.80

Perhaps the most important, yet least obvious, way in which Foxe shaped the ‘Book of Martyrs’ was through his arrangement of its contents. The first edition has a truly chaotic structure resulting, in large part, from the disruption of its chronological narrative by the insertion of material that arrived while the book was being printed.81 In the second edition, relative order was imposed on the book’s contents, but it was not a strictly chronological one. Instead, Foxe follows a loose chronological format, but rearranges stories and episodes for a variety of reasons. One of these was to make the A&M more readable by interposing episodes of comic relief amidst the grim tales of suffering and death. For example, in the first edition, Foxe introduces a story of a panic created by a false alarm of fire in a crowded building: ‘Hitherto gentle Reader, we have remembered a great number of lamentable and bloody tragedies of such as have been slayne through extreme crueltie. Nowe I will here set before thee againe a mery and comycal spectacle, wherat thou mayest now lawgh and refresh thy selfe.’82 Similarly, Foxe prefaced a story of Bishop Bonner losing his temper during an episcopal visitation with the explanation that he included it ‘although it touch no matter of religion’ because ‘it may refresh the reader weried percase with other dolefull storyes’.83

Foxe organized his book’s material for thematic, as well as stylistic, reasons. As a case in point, the lives of the popes were often constructed so that a particular pope would personify particular vices or crimes. In his second edition, Foxe carefully arranged anecdotes about Sixtus IV to present a pattern in which pimping and prostitution progressed to the sale of indulgences (in Foxe’s eyes, spiritual prostitution), and then, with a story about Sixtus granting an indulgence absolving sodomy, Foxe intertwined the twin themes.84 We might also consider Foxe’s treatment of the final years of Henry VIII’s reign. In the first edition, the rather chaotic arrangement of this material reflected both haste and the haphazard acquisition of information. In the second edition, this material was presented out of chronological sequence, but carefully arranged nonetheless, in order to highlight the themes of unjust persecution, evil counsellors, and royal failure to reform the church.85

These examples of Foxe’s editing are taken from the first two editions, and largely from the second because Foxe exercised the tightest editorial control over the second edition. Foxe was only minimally involved in preparing the third edition, which essentially reprinted the second edition’s text without change.86 Foxe participated more extensively in editing the fourth edition; although the haste with which it was prepared meant that he could not edit it as closely as he had the second, Foxe did closely supervise the material he added to the fourth edition.87 The fourth edition, printed in 1583, was the last printed during Foxe’s lifetime. There would be a further five unabridged editions printed until the ninth edition was printed in 1684. Additions were made to these editions, but the core text, so painstakingly edited by Foxe, remained unchanged throughout.

As we have seen, Foxe’s editing of this core text was so thorough and systematic that his role is much closer to that of an author—understood as one who shapes and disseminates a body of text—than a compiler—one who assembles texts mostly by simple accretion. Perhaps the analogy which best describes Foxe’s relationship to the text of the ‘Book of Martyrs’ would be that of a conductor who also arranges and orchestrates the work of the composers he is conducting. While not the creator of the score, he dictates the ways in which it is heard.

There is no single prose style in the ‘Book of Martyrs’. Not only is the text of the work written by scores, if not hundreds, of people, but, more fundamentally, the writings incorporated into the martyrology came from a wide variety of genres. Nevertheless, we believe that it is valid to discuss both the authorship and the prose of the ‘Book of Martyrs’. Revisions within the Acts and Monuments were not haphazard; instead, from the second edition onward, the work was carefully arranged and edited for the purposes of edifying readers, countering polemical opponents, and even, on occasion, entertaining those who perused its pages. A gifted rhetorician, Foxe was alert both to the importance of style and to the varied ways in which multiple concepts of authorship might signify in the early modern period, as his prefaces clearly demonstrate. Taking pains to shape the prose content of the ‘Book of Martyrs’ to serve his didactic and polemical purposes, Foxe emended the texts he gathered or acquired with remarkable attention to detail, with the result that a huge compilation was, nevertheless, astonishingly uniform and unambiguous in the messages it presented to generations of readers. Foxe certainly did not work alone, but drew on the research of a battalion of collaborators and writings of an army of sources. Still, the themes of the book and the vision of the church and its history that it presented came from the mind of John Foxe. In this crucial sense, it was, without question, Foxe’s book of martyrs.

Adamson, Sylvia, Gavin Alexander, and Katrin Ettenbruner, eds. Renaissance Figures of Speech (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Anderson, Benedict. ‘Neither Acts Nor Monuments’, English Literary Renaissance, 41 (2011): 3–30.

Evenden, Elizabeth, and Thomas S. Freeman. Religion and the Book in Early Modern England: The Making of John Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

King, John N. Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’ and Early Modern Print Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Knott, John R. Discourses of Martyrdom in English Literature, 1563–1694 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Lander, Jesse M. Inventing Polemic: Religion, Print and Literary Culture in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Mack, Peter. A History of Renaissance Rhetoric, 1380–1620 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

——— Elizabethan Rhetoric: Theory and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Monta, Susannah B. Martyrdom and Literature in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Mueller, Janel. The Native Tongue and the Word: Developments in English Prose Style, 1380–1580 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

North, Marcy. The Anonymous Renaissance: Cultures of Discretion in Tudor-Stuart England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Shuger, Debora. Sacred Rhetoric: The Christian Grand Style in the English Renaissance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

Woolf, Daniel R. ‘The Rhetoric of Martyrdom: Generic Contradiction and Narrative Strategy in John Foxe’s Acts and Monements’, in Thomas F. Mayer and Daniel R. Woolf, eds., Rhetorics of Life-Writing in Early Modern Europe: Forms of Biography from Cassandra Fedele to Louis XIV (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995), 243–82.