WRITING his haughty and occasionally blistering review of Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, the philosopher Kenelm Digby weighs up its amorphous subject matter: ‘This gentlemans intended Theame; as I conceive’, he concludes, is ‘the scope and finall period of True religion’, by way of which, Browne goes ‘wading so deep in sciences’ that he finds himself lost in digressive circles on the science of the soul, of resurrection and revivification, the ‘abstracted subtilties’ of eternity and flux.1 Digby considers, with not a little snobbery, that a physician ‘whose hands are inured to the cutting up & eies to the inspection of anatomized bodyes’ is not naturally suited to the contemplation of ‘a Separated and unbodyed Soule’. This is not, however, too rigorous a separation: although practical anatomy may dim the mind to such matters, knowledge of the soul and its fate in eternity still requires ‘a totall Survey of the whole science of Bodyes’.2 That the ‘whole science of Bodyes’ happened also to be the subject of Digby’s forthcoming magnus opus has made Browne scholars deeply suspicious. It has been treated, by and large, as a criticism designed to protect Digby’s own intellectual turf, if not a grandiose piece of self-puffery.3 That there was a physics (as well as a theology) of resurrection, however, would be neither alien nor anathema to Browne, whose conception of religion was wholly imbricated with his understanding of natural philosophy. Indeed, Digby’s comment might be seen as a proper entry point upon a work which, though a labyrinthine mixture of the personal, the theological, and the scientific, deals continually and capaciously with the soul and its philosophical relation to the ‘elemental composition’ of body, ‘these walls of flesh, wherein the soul doth seem to be immured before the resurrection’.4 From the bodies of angels, to the predestinate soul, to the fate of material atoms in the resurrection, Religio Medici brushes close to the theological materialism that so preoccupies early modern philosophy. Browne made rapid pre-publication peace with Digby, in part by implying his own work was the mere hackery of his youth, dashed off as Digby’s reply so evidently was, and the two texts went forth as awkward conjoined twins over subsequent decades, prompting Samuel Johnson’s acerbic comment: ‘The reciprocal civility of authors is one of the most risible scenes in the farce of life.’5

Religio Medici remains a perplexing amalgam, with its wandering subject matter and its rhetorical silkiness. Its uppermost level is a meditation on religion, though even within such a category, it is a slippery entity, at one moment confessional and irenic, capaciously tolerant and gentle on heresies, while the next it is fastidious and captious about the radical presence in England. It is by turns a rhapsody on Laudian ceremony, a miscellany of scriptural curiosa troubling the categories of faith and reason, and a disquisition on spirit, soul, and body.6 Rhetorically and perhaps philosophically, this is a full-scale lecture on indirection. Quite often, in recent decades at least, it has been treated as an autobiography, again, perhaps, following Digby, who comments: ‘What should I say of his making so particular a narration of personall things, and privat thoughts of his owne, the knowledge whereof can not much conduce to any mans betterment (which I make account is the chiefe end of his writing this discourse)?’ Oscillating between admiration and exasperation, as so many of Browne’s subsequent readers have done, Digby heaps praise upon him ‘our authors æquanimity and … magnanimity … the owner of a solid head and of a strong generous heart’, though he tempers that praise too. He is, Digby puts it with winning pomposity: ‘a very fine ingenious Gentleman: but for how deepe a Scholler, I leave unto them to judge, that are abler than I’.7 If Religio Medici does qualify as autobiography, it is not because there is any great quantity of personal Browne-life in the text, but rather, because, through its delirious range of topics, the work revels in its own authorial tone, shifting between a conversational diffidence—whose modesty would concede each point it makes upon the proffering of any better argument—and full oratorical grandeur. It is, or it might seem to be, tone, rather than substance, that is the unifying centre of the work, that the personal is identifiably present in the voice and the stylistic singularity. This inimitable prose strategy will be central to the ensuing discussion of Religio Medici, but it is also an important proviso that, for his contemporaries, the work was ‘about’ something—it was philosophically and theologically engaged, and the second half of the essay returns to Browne’s extensive poetics of the embodied and the unembodied soul.

The distinctive prose idiom of Religio Medici has been the basis of Browne’s enduring reputation. It is one of the few works of prose from the seventeenth century that has rarely, if ever, been out of print and it has attracted consistent critical attention. Lionized by an impressive line-up of writers, from Charles Lamb to Coleridge, from Poe, Emerson, and Melville to, more curiously, Bram Stoker in preparing Dracula, Browne has an illustrious history of admirers.8 Borges and Sebald have responded to the lost and labyrinthine qualities of his writing, while Tony Kushner reconstitutes a misanthropic miserly Browne for the stage, characterizing his prose as an ‘ornate jewelled swooniness’.9 A heady twentieth-century effort went into identifying the quality of the prosody, its metre, cadence, and scansion, or attempting to locate its essential pulse, whether in its ‘Hebraic symmetry’, its relentlessly duplet-phrasing, or its putative relations to Baroque, Asiatic, Ciceronian, or Senecan characteristics.10 ‘Is Browne among the cadenced?’ asks Austen Warren, in terms that might as easily be asking whether he is among the predestinate and the elect.11

Prose as a disembodied subject of analysis, divorced from the thick histories and context in which texts might be seen, has or had fallen out of literary favour, though the tide may be turning. But it is not returning unchanged. This chapter makes the probably uncontentious case that prose style is tightly wound up in its subject matter, though this is not to say that there is any deterministic relationship between what is said and how, particularly in a work whose subject is quite so indeterminable. If English Literature has largely forgone analysis of prose over the past few decades, however, the history of science has taken up the subject with some gusto. Much has been written, for example, on the rhetorical strategies by which scientific communities formed and authorized themselves, the idioms of ‘gentlemanly’ address by which the natural philosopher distinguished himself from the artisan gatherer of knowledge. Scientific discourse was unambiguous in the importance it placed on rhetorical courtesy and frumperies, rarely enough allowing mere expertise to trump refined manners.12 This recent history of reading prose rhetoric as a part of the social fabric in which texts are enfolded is not the same, of course, as reading for the stylistic panache that Browne demonstrates. Although he was reckoned and recognized as a natural philosopher, Browne’s prose is quite distinct from his scientific contemporaries, and usefully complicates any attempt to define what scientific prose looked like. It is further complicated by the amalgam of subject matter that constitutes Religio Medici. The same idiom that explores Laudian ceremony also engages the ontology of angels, baffles itself in scriptural minutiae, and asks what chemical processes might be at play in the bodily resurrection of the apocalypse.

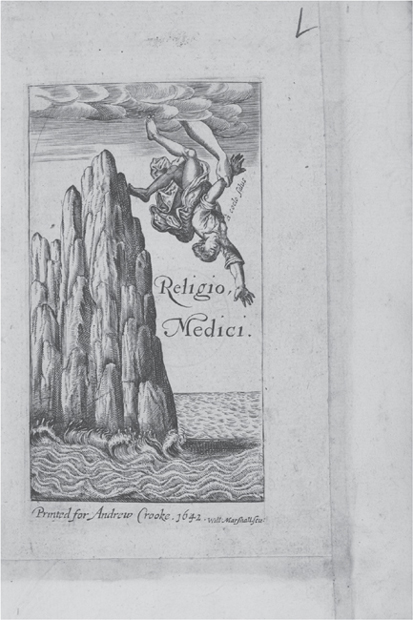

Browne’s writing responds to a broad set of philosophical and religious contexts, scientific and political upheavals, while maintaining, it might be said, its idiosyncratic distance as well. Religio Medici appeared in 1642/3 (Fig. 39.1), a time of unparalleled upheaval, and his subsequent body of writing—Pseudodoxia Epidemica in 1646, Hydriotaphia, or Urn Burial, and The Garden of Cyrus in 1658—appeared over the era of the Civil War, regicide, and interregnum, with its turmoil and displacement. A number of posthumous tracts, a large volume of letters from after 1660, and a collection of working notes and experimental problemata make for a more hefty corpus, however. If there is a defining tone that characterizes Browne across his works, it is what has been described by Claire Preston as a contingent, provisional, and uncertain habit of statement, a willingness to hold competing explanations in play without resolution.13 And yet, this provisionality and reticence is delivered with such booming oratorical panache as to admit no objection. Browne’s statements of belief or his investigations of fact generally allow that he might be wrong, that he is not at all to be taken as authoritative, and yet, to dispute mere fact, in the presence of a voice so rotund, so intoned and homiletic, is to appear sniping and picky. The fate of readers who pick thus—from Alexander Ross, Browne’s contemporary and stock pedant of early modern England, to Stanley Fish, the critical theorist who, in the 1970s, made a set of sometimes bizarre moral-poetic accusations against Religio Medici—is to be counted a reader who cannot hear the oceanic in Browne’s writing, the greater swell of his rhetoric.14 This is Browne’s wonderful rhetorical trick, to insist on his openness to contradiction in a voice whose majestic torrent brooks no interruption, that is softly and flexibly incontrovertible, a voice that has, at times, perhaps naïvely, been seen as an irenic and tolerant disposition, but which is both fastidious and relentlessly creedal.

FIGURE 39.1 Thomas Browne, Religio Medici (1642)

Religio Medici is all about what Browne does not know, plumbing fabulous depths of ignorance. This begins as the lulling, if not the confounding of reason, although it does not end there. He quotes Tertullian’s dictum from De Carne Christi on the incarnation and bodily resurrection ‘Certum est quia impossibile est’—‘It is certain because impossible’.15 What is provable remains mundane; ‘ordinary and visible objects’ yield ‘not faith but perswasion’. Browne will have his paradoxes run rings around ocular proof as much as reason. He is, he tells us, ‘thankefull that I lived not in the dayes of miracles, that I never saw Christ nor his Disciples’. A Christian who denies he would have willingly seen Christ may border on paradox, but underlies an epistemology that revels in its insufficiencies. To know is one thing, but Religio Medici is more interested in the faulty tools of knowing, the fractures in reason, and how such a flawed instrument forces us to recalibrate the limits of knowledge: ‘acquainting our reason how unable it is to display the visible and obvious effect of nature’.16 ‘It is impossible’, he explains, that ‘to the weaknesse of our apprehensions, there should not appear irregularities, contradictions and antinomies’.17 The work employs a sometimes Pauline, sometimes Platonic attempt to comprehend the invisible—which is the real object of knowledge, be it form or faith—through a transposition of the visible, ‘that universall and public Manuscript that lies expans’d unto the eyes of all’, in which the ‘common Hieroglyphicks’ of nature, the signatory presence of God in creation, may be discerned.18 This rhapsodic supposition that the natural world will yield its dividend of theology may, of course, cover a degree of tension, described by Brook Conti as less a marriage of faith and reason, than an amicable ‘divorce settlement’ in which ‘each faculty gets custody of the issues proper to it’.19 This is, however, a very messy divorce. If Browne seeks an obfuscation and humbling of reason, it is less often to elevate doctrine, than for the almost sensual pleasure of bafflement.

Time is a topic whose paradoxes Browne indulges in fully; and though time may present its puzzles, he insists that it remains within the remit of ordinary philosophy, a mere bagatelle of a mystery in comparison with eternity, which is more exquisitely opaque: ‘Time we may comprehend, ’tis but five days elder then our selves and hath the same Horoscope with the world.’ From the panache of this claim, that time, created on the first day, is hardly older than humanity created on the sixth, he asserts that eternity constitutes an altogether more delightful ‘extasie’ to ‘confound my understanding’:

but in eternity there is no distinction of tenses, and therefore that terrible terme Predestination, which hath troubled so many weake heads to conceive, and the wisest to explaine, is in respect to God no prescious determination of our estates to come, but a definitive blast of his will already fulfilled, and at the instant that he first decreed it.20

Browne’s plunging himself into obfuscation is the major rhetorical dynamic of Religio Medici, but there is another keynote at play here. In one of his many rhetorical swivels, he sallies out with what seems a forthright attack on ‘that terrible terme’ Predestination, with all its political freight, but pulls back from the brink of controversy. Though it seems initially blunt and unequivocal, predestination—still doctrinally orthodox into the 1630s—emerges relatively unscathed: the ‘definitive blast’ of God’s will remains in place, but outside of time and, more significantly, beyond the realm of the knowable. It turns out only to be an attack on the ‘weake heads’ of his political adversaries, an ill-defined non-Arminian wing of the church.21 While Browne appears at times irenic, and while he depicts himself as above theological hair-splitting, he rarely fails to make it plain which side of the split hair he is on.

William Hazlitt, writing in 1820, describes Browne’s insistent pushing towards ‘the utmost verge of conjecture’ and that any topic is considered only to ‘bewilder his understanding in the universality of its nature and the inscrutableness of its origin’. It is a prose constructed in ‘the intricate folds and swelling drapery of dark sayings and impenetrable riddles’.22 Hazlitt suggests—and it is the experience of many of Browne’s readers—that the philosophical content of such arguments is enwrought in its prose form, that the ‘swelling drapery of dark sayings’ constitutes its mystery and theology. Not every reader, however, responds so effusively to the idiosyncratic prose. Noah Webster, the dictionary compiler, complained that his lexographic predecessor, Samuel Johnson, had paid far too much attention to seventeenth-century writers who ‘had neither taste nor a correct knowledge of English’, in particular, Browne, of whom Webster says, ‘the style of Sir Thomas Browne is not English’. It was, he supposed, ‘astonishing that a man attempting to give the world a standard of the English language should have ever mentioned his name, but with a reprobation of his style and use of words’, chiding, in particular, Browne’s Latinate vocabulary and giving examples of the mangled syntactical forms that Browne so routinely intrudes into his prose.23 Hazlitt and Webster are closer in their estimation than might appear. Both suppose that unintelligibility is not incidental, but the very signature tune of Browne.

Reason crumples in its effort to encompass the enormity and complexity of nature, itself providing only a mere glimmer of the ineffable beyond. Philosophy or theology can offer only a shadowy engagement with the real. Browne, however, performs a sleight of hand, in rendering this incomprehensibility, producing his own version of that collapse of reason in the marrow of his prose. Religio Medici skews its syntax as an object lesson in abasement and humility in the face of the inexplicable. ‘To difference my self nearer, & draw into a lesser circle, There is no Church whose every part so squares unto my conscience’, he tells us, early on.24 Aside from his deft squaring of a circle in the course of the phrase, aside too from his noun, where a verb should be, the ostensible meaning is to clarify or to particularize his position, which he does first by ‘differencing’ himself, which should imply moving apart, rather than moving ‘neerer’. In both local phrase and wider theme, Browne has his grammar work at the outer parameters of coherence. He manages to profound as a verb, meaning to drill down and plumb mysteries: ‘There is no danger to profound these mysteries, no Sanctum sanctorum in Philosophy.’25

The apocalypse, for Browne, is the moment ‘when all things shall confesse their ashes’, making the word ‘confess’ do things it has surely never before or since had to do—the expected collocation of confessing sins or crimes is wrought into the entirely more demanding instance of every object admitting the general dissolution of the self in death and handing back its ashes.26 The context here is ostensibly the perishability of books, of the ‘leaves of Solomon’, of burnt libraries and laws—only the scriptures being ‘a worke too hard for the teeth of time’.27 The ashes of the eschaton in Religio Medici belongs to a philosophic-theology that I will return to. At issue, here, is the conscious and continual collapse of grammar; a syntax awry and frequently a semi-tone off-key; collocations that are only fleetingly and poetically logical; a carefully wrought imprecision in, as Tony Kushner has put it, a ‘style of such voluptuous baroquosity it melts the straight lines and tight angles of the Euclidean universe’.28 This is most evident in the subterranean effects of Browne’s sentence structures, the length and weighting of which, with their balanced or ill-balanced clausal swell, produces an unfathomable polyphony.29 Brownean single-sentence paragraphs perform an elaborate tracery of ideas, though editing sometimes obscures this intricacy.

Early modern prose is, it might be said, quite proud of the labyrinthine dimensions of its pauseless sentences, its rhetorical theory consummately aware of both the architecture of texts and the interior design of its sentences. If Browne disobeys every rule of inventio, the process of selecting, unfolding, and sticking to one’s topic—his is a fireworks display of subject matter, rather than a single explosion—he might be following the very prototype of the individual ‘period’ given in a 1665 work, The mysterie of rhetorique unveil’ d, in which John Smith assessed the aesthetic design and balance of sentences:

That period is the most excellent, which is performed with two Colons (and sometimes Commas) or four parts of a sentence, as that which suspends the mind, and satisfies the ears … Herein beware that the Period be not shorter then the ear expects, nor longer then the strength and breath of the Speaker or Reader may bear, and that it finish its course in a handsome and full comprehension.30

This describes, though dryly, something of the style of Religio Medici and yet, we are right to suppose that Browne does more than follow the (not-yet-written) manual. Such analysis may describe the scaffold of a sentence, but not what it does once it becomes live and independent. For Browne, the individual sentence, in its complexity, works to replicate the disjointedness of the world.

If Religio Medici revels in the unintelligible nature of nature, the crumple of reason that the mind experiences as it tries to comprehend the infinite, it is particularly adamant that the processes of nature should not be ascribed to nature itself—it being a kind of intellectual hubris to suppose that ‘nature’ is thus independent. To do so is ‘to devolve the honor of the principall agent upon the instrument’, to nature instead of God: ‘Then let our hammers rise up and boast they have built our houses, and our pens receive the honour of our writings.’ Such a rebellion of the tools is, for Browne, an unthinkable arrogating of the honour that belongs properly to the divine. Being mildly jealous of his creation, God will not, however, allow too great a degree of presumption, and though his practice may be to transcribe the world in perfect circles of natural regularity, according to the ‘forelaid principles of his art’, occasionally too he will include sheer oddities, ‘hee doth sometimes pervert, to acquaint the world with his prerogative, lest the arrogancy of our reason should question his power, and conclude he could not’.31 God, it seems, launches prevenient strikes against regularity, lest we suppose our minds sufficient to grasp the enormities of scale on which nature is etched. Irregularity in the world, as in grammar, serves to baffle our certainties and presumptions about its workings.

It would be wrongly formulating the issue, however, to suppose that Religio Medici is in any straightforward way about reason and faith. Browne is interested in the essential unintelligibility of the world, not because he has abnegated reason and passed the buck to faith, if by that we were to mean accepting theological truths cordoned off from philosophical or scientific investigation. On the contrary, Browne announces his rigorous intention to marry science to his contemplation of God. In fact, nature will have to do so entirely, God being otherwise unknowable, ‘for we behold him but asquint upon reflex or shadow; our understanding is dimmer than Moses eye, we are ignorant of the back-parts, or lower side of his divinity’, he explains, with passing reference to God’s jaunty refusal in Exodus to allow Moses to see his enigmatic backparts.32 The point is more that when we look, as Paul has it, through a glass darkly, the very distortion of paradox acts as a corrective to our naturally skewed perspectives.33 Whether it is the soul in man or the heaven beyond the outer crystalline sphere that we aim to discern, ‘we must suspend the rules of our philosophy, and make all good by a more absolute piece of opticks’.34 Paradox depends on momentarily assenting to what cannot, more logically, be true, a comprehension that functions only asquint, with reason rectified by a ‘more absolute piece of opticks’.

Browne is aware, he tells us, that he spends his time, ‘raking into the bowells of the deceased’ and that the ‘continuall sight of anatomies, skeletons, or cadaverous reliques’ might make us suppose him insensitive to death, or, as Digby suggests, insensitive to soul.35 But this, he argues, makes him all the more aware of the delicate conditionality of the self at the cusp of life, before, during, and after, which he terms our ‘being and life in three distinct worlds’. The first world has the not-yet-born child apparently biding time, yet to encounter enough objects to have formed itself into full being: ‘in that obscure world and wombe of our mother, our time is short, computed by the moone; yet longer than the dayes of many creatures that behold the sunne, our selves being not yet without life, sense, and reason, though for the manifestation of its actions, it awaits the opportunity of objects’.36 The unborn child patiently waits for the stimulation of objects, to prompt ‘sense and reason’ into life, less a Lacanian moment than a child greedy for toys or an ambitious courtier waiting for a place. Browne’s midwifery gives way, however, to theology, and just as a new-born will leave behind it the ‘secondine’ or afterbirth, so at death the body becomes the disposable portion of the self: ‘till we have once more cast our secondine, that is, this slough of flesh, and are delivered into the last world, that is, that ineffable place of Paul, that proper ubi of spirits’.37

Though momentarily seeming so, this is no ascetic repudiation of body, which, in all its physicality, is the crucial, though fragile, conduit to knowledge of the soul. ‘[I] have examined the parts of man’, Browne explains, ‘and know upon what tender filaments that fabric hangs … considering the thousand doors that lead to death’.38 This is the physician of the title speaking, a figure who has often been lost in critical discussion of Religio Medici, focused on the politics of Laudianism and ceremony that occupy the opening parts of the work.39 But fully half of the first part of Religio Medici deals in one way or another with spirit and soul and their relation to body, first, how angels might be said to subsist as material beings, together with the nature of Platonic and diabolic spirits (29–36), the subject of so much early modern speculation.40 Browne the vivisectionist seems to emerge, momentarily, in his discussion of an imagined quasi-chemical process of spiritual liposuction: ‘Do but extract from the corpulency of bodies, or resolve things beyond their first matter and you discover the habitation of angels.’41 When one syringes away all the material of angels, in the nothing and the no-place (or the ubiquity) that is left, we can discover their native habitat. Though this may be a rhetorical, rather than a laboratory experiment, the same cannot be said of his efforts to locate the soul in humans. If it is too early for him to be responding to Descartes’s positioning of the soul in the pineal gland, via a process of anatomical observation and haphazard elimination, Browne nevertheless probes the material body for signs of the soul, worrying that there is no organ where it might be located: every ‘crany’ of the brain seems to be the same in beasts: ‘this is a sensible and no inconsiderable argument of the inorganity of the soule’.42 From here on to the end of first book, death is the chief topic of Religio Medici, from its encompassing Adamic legacy to fear of, or as Browne will have it, embarrassment at death (37–45), moving on to his treatment of the last judgement, the afterlife, and the constitution of hell and, most oddly, the physics or, at times, the chemistry of resurrection, it being hard to say to what modern science we should attribute the natural philosophy of the soul in the apocalypse (47–60).

‘How shall the dead arise?’ Browne asks, but this is not a theological question. The tools that address this are philosophical and the analogies by which such a resurrection can be comprehended are scientific—the action of mercury and the experimental palingenesis of plants. The oddness in this is the supposition that such a central theological tenet—the rising of the dead—might and must be understood in terms of its physics. The Browne who seemed to insist on the productive unintelligibility of the world, who revels in what is unknowable, chooses to think out the mechanisms by which the dispersed self might return to its proper shape. It is important to Religio Medici, rhetorically and structurally, that even at such quasi-scientific moments, it is attended by creedal statements, that even while the text wrestles with a set of physical processes, the motion of matter on the last day, its rhetorical form is one of abnegating the need for explanation: ‘I beleeve that our estranged and divided ashes shall unite againe, that our separated dust after so many pilgrimages and transformations into the parts of mineralls, plants, animals, elements, shall at the voyce of God returne into their primitive shapes; and joyne againe to make up their primary and predestinate forms.’43 In the whirlwind of the eschaton, the dust out of which we were formed will remember its origin and return to its proper owner. Browne imagines the course of the world, from creation to apocalypse, as an exhalation of matter into its distinct and individual forms and its further individuation over time, till at the apocalypse, they will retreat through all their processes of dissolution and return to their pristine condition:

As at the creation of the world, all the distinct species that we behold, lay involved in one masse, till the fruitfull voyce of God separated this united multitude into its severall species: so at the last day, when these corrupted reliques shall be scattered in the wildernesse of formes, and seeme to have forgot their proper habits, God by a powerfull voyce shall command them backe into their proper shapes, and call them out by their single individuals.44

In what borders on the philosophically comic, Browne parallels the dissolution of matter that occurs in death and decay with the sperm of Adam dividing and subdividing into the entire human race: ‘Then shall appeare the fertilitie of Adam, and the magicke of that sperme that hath dilated into so many millions.’ But any such dispersal of matter will be rectified and reversed, just as mercury does on the laboratory table: in its silvery liquidity being perhaps the most incongruous model of resurrection to be found: ‘I have often beheld as a miracle, that artificiall resurrection and revivification of Mercury, how being mortified into thousand shapes, it assumes againe its owne, and returns into its numericall selfe.’45 Just as quicksilver can miraculously revivify itself in ‘artificiall resurrection’, plants too are models of the reconstitution of the body at the apocalypse. Explaining the process of palingenesis, bringing a plant back to life from its burnt and ashy leaves, Browne insists that he is wearing the garb of a philosopher, though no scholastic or ‘schoole philosopher’. Rather, he characterizes himself as ‘a sensible artist’, meaning an artist of experience and the sensible or bodily realm, in order to figure forth what God will accomplish, not metaphorically, but in ‘ocular’ fashion. This is a passage worth quoting at some length, for its rhetorical panache and disciplinary breadth:

Let us speake naturally, and like philosophers, the formes of alterable bodies in these sensible corruptions perish not; nor, as we imagine, wholly quit their mansions, but retire and contract themselves into their secret and unaccessible parts, where they may best protect themselves from the action of their antagonist. A plant or vegetable consumed to ashes, to a contemplative and schoole philosopher seemes utterly destroyed, and the forme to have taken his leave for ever: but to a sensible artist the formes are not perished, but withdrawne into their incombustible part, where they lie secure from the action of that devouring element. This is made good by experience, which can from the ashes of a plant revive the plant, and from its cinders recall it into its stalk and leaves againe. What the art of man can doe in these inferiour pieces, what blasphemy is it to affirme the finger of God cannot doe in these more perfect and sensible structures? This is that mysticall philosophy, from whence no true scholler becomes an atheist, but from the visible effects of nature, growes up a reall divine, and beholds not in a dreame, as Ezekiel, but in an ocular and visible object the types of his resurrection.46

The pulverized matter and dust of being, in such an account, does not altogether forget its origin or ‘wholly quit’ its mansion, but rather, contracted into its ‘secret and unaccessible’ atomic or Platonic form, awaits a revivification. Burning does not destroy, but only rehouses the form and memory of its original, ‘withdrawne into their incombustible part’.47 Thomas Bartholin, the Danish physician, writing in his anatomy on the qualities of teeth, how their hardness gives them the ability to withstand fire, notes that Tertullian supposed they might, on these grounds, be the durable seedling of the self, ‘that in them is the Seed of our future Resurrection’.48 Matter, it seems, contains an innate homing instinct. At one moment philosophical, the next mystical, Browne incorporates both experiment and patristics, until he shifts to an insistence that the resurrection, as conducted by the finger of God, must have its ‘types’ and models in nature, and these be the ocular and experimental correlates he finds in his science.

Browne’s is only a brush with natural philosophy, it might be said, as, earlier on, it was only a brush with Laudian ceremony—this is his essayistic strategy and not necessarily any penetrating contribution to early modern science. But seventeenth-century Europe was thoroughly wrapped up in just such questions of theological materialism, the nature of body, its relation to soul, and the curious memory of matter. Joseph Glanville, in the Vanity of Dogmatizing (1661), explores the tendency of matter, the leaf of a herb in this instance, to leave its tracery intact in its surrounding environment, the frosted water of a winter’s night being imprinted with the memory of leaves that had lodged there earlier. Glanville comments:

Now these airy Vegetables are presumed to have been made, by the reliques of these plantal emissions whose avolation was prevented by the condensed inclosure. And therefore playing up and down for a while within their liquid prison, they at last settle together in their natural order, and the Atomes of each part finding out their proper place, at length rest in their methodical Situation.49

Atoms here are almost wilful and animate in the resumption of their form, Glanville going on to address this in terms of palingenesis directly, ‘the artificial resurrection of Plants from their ashes, which Chymists are so well acquainted with’.

Robert Boyle, perhaps the foremost proponent of experimental and mechanical philosophy, is still closer to Browne, discussing the body in the resurrection by reference to alteration and physical identity, how water turned into ice retains the same corporeal identity, how the leaven of bread permits of change within stability, noting too ‘those Chymical Experiment by which Kircherus … and others, are affirmed to have by a gentle heat been able to reproduce in well-closed Vials the perfect Idea’s of Plants destroyed by the fire’. He notes also his own experience of some ‘alcalisate ashes’ of burnt poppy revivifying ‘which seems to argue, that in the saline and earthy, i.e. the fix’d Particle of a Vegetable, that has been dissipated and destroyed by the violence of the fire, there may remain a Plastick Power inabling them to contrive disposed Matter, so as to reproduce such a Body as was formerly destroyed’.50 Such plastic power is, he posits, the animating mechanism for deriving Eve from Adam’s rib and the raising of Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones.51

If the chemistry of resurrection is a viable subject, this does not, of course, obviate theological controversy. Guy Holland, writing his attack on mortalist ideas that the soul dies with the body, engages Religio Medici as an authority on the soul, though less to condemn Browne’s recounting of his brief flirtation with ‘the Arabian Heresy’, than to enlist Browne in proving the indestructibility of matter, despite the continual mutation it may be subject to:

Naturall and materiall forms themselves also do not perish at their parting from their matters, but onely are dissolved and dissipated, lying after that separation in their scatted atomes within the bosome of nature … so that the entity of their form remains still unperished after corruption, though not in the essence and formality of a form, or totally and compleatly. Thus teacheth the learned Authour of Religio Medici.52

Holland, a Jesuit, will not entirely have Browne as an ally, but as he proves useful, will borrow from him. Peter Heylyn, discussing the nature of resurrection in Theologia veterum (1654), similarly supposes that the coming together of dispersed pieces of dissolved and attenuated matter speaks to theological questions: ‘For it is found by those who do trade in Chymistry, that the forms of things are kept invisibly in store, though the materials of the same be altered from what first they were’, reporting on the experiment of reproducing a plant from its macerated atoms and the ashy salt extracted from a vigorous pummelling of its parts, remarking how ‘The ingenuous Author of the Book called Religio Medici, doth also touch upon this rarity.’53 Heylyn, it is true, is no scientist, but Robert Boyle, Henry Power, Kenelm Digby, and Henry More all provide impressive attempts to have physical phenomena yield eschatological conclusions, all supposing that physics, experimental and philosophical, should naturally lead to theology.

There were also exasperated responses to such physico-theology. Writing his critique of Henry More’s millennial physics, An explanation of the grand mystery of godliness (1660), Joseph Beaumont takes the philosopher to task for his providing an account of the mechanisms by which the resurrected body with its ‘Terrestrial consistency of Flesh and Blood’ might find the celestial spheres too ‘subtile’ and incongruous an element to subsist in. ‘Could Dr More forget’, asks Beaumont, ‘that both the Resurrection, and Ascension and residence of Bodies in Heaven, are not atchieved by any natural ways or means, but solely by the supernatural Power of God?’54 It is perhaps strange that Browne, so insistent that he revels in things beyond the human ken, should not agree. Of all the mysteries and theological arcana that might provide juice for paradox, bodily translation to heaven in the apocalypse might seem high on the list. Yet, Browne insists that this is an area for the natural, rather than the contemplative, philosopher to take over.

Browne’s chemical resurrection cannot entirely be rescued from itself by reference to the history of ideas, that that was how they thought back then. On the contrary, it was very much a cutting-edge concatenation of disciplines, and if few enough (if eminent) scientists had engaged in such topics, fewer still did so in the luscious language out of which Browne sculpts his concoctions of physico-theology. Having Boyle for a colleague in ideas on the material action of the last day may be some mitigation, but Browne is not Boyle, by any stretch of the mechanical imagination; Browne’s is a poetics of the physics of the resurrection (bringing a third incompatible term to the table). We should not shy away too much from the implication that it is a ‘poetics’ of the topic insofar as it is incoherent and incomplete as either a piece of natural philosophy or as a piece of theology. But this is an incoherence with (almost) a theological basis. Religio Medici toys with and is content with the beautiful half-theory, and the mere glimpse of the world’s inner workings, because the world is endued with the character and unknowability of God: science magnifies one’s capacity for ignorance. Nature, down to its most microcosmic and microscopic miniature forms, even when studied, anatomized, and searched as far as it will go, always results in metaphor. It tells us something only obliquely and aslant about God. When Browne considers again the chemistry of last things, his theology in the laboratory prompts him to note that things burnt to their utmost vitrify, or turn glaseous:

Philosophers that opinioned the worlds destruction by fire, did never dreame of annihilation, which is beyond the power of sublunary causes; for the last and proper action of that element is but vitrification or a reduction of a body into glasse; and therefore some of our chymicks facetiously affirm, that at the last fire all shall be crystallized and reverberated into glasse, which is the utmost action of that element.55

Few moments in the history of eschatology can surpass the poetics of this, when Browne suggests that the final conflagration would not lead to the destruction of the world, as such, because fire does not ultimately annihilate. Rather, the last stage of firing ‘vitrifies’, or renders the material glass. Thus, the world, in its final burning, may turn into a glass model globe of itself. This is a beautiful apocalypse. Browne shifts, with little sense of discordance, from the quotidian action of the laboratory to the divine action of the eschaton, and though attached to the sometimes pejorative ‘chymicks’, the word ‘facetiously’ may here bear the sense of polished and ‘elegantly’, rather than flippant or jokingly. The idea works for Browne, not because he is a card-carrying and committed member of the glass-apocalypse school of physics, but because it permits a passingly lovely glimpse of how to square divine benevolence with divine wrath. Who the philosophers and chymics are, I have yet to discover, though the royalist soldier, James Howell, suggests it to have a certain currency. Considering his sight of the Venetian glass-works, he writes in a letter to his brother, in a work published in 1645: ‘Surely, that grand Universal-fire, which shall happen at the day of judgment, may by its violent-ardor vitrifie and turn to one lump of Crystal, the whole Body of the Earth’, adding ‘nor am I the first that fell upon this conceit’.56

Browne has shifted from the quasi-embodied soul of angels, through to the resurrection of the individual body and on, finally, to the apocalypse. If the dissolved individual can be saved, there is no such biblical promise of the preservation of nature, but Browne dismisses the possibility of absolute annihilation, by, it might be said, another sleight of hand. If one individual survives, who, in their microcosm, reiterates the entirety of the cosmos, then the whole world survives with them: ‘Nor need we fear this term “annihilation” or wonder that God will destroy the workes of his creation: for man subsisting, who is, and will then truely appeare a microcosme, the world cannot bee said to be destroyed.’57 He continues with a passage in which resurrected bodies will be able to see the totality of the world in, as William Blake might have it, a grain of sand, to discern a microcosm in the seed of a plant:

For the eyes of God, and perhaps also of our glorified selves, shall as really behold and contemplate the world in its epitome or contracted essence, as now it doth at large and in its dilated substance. In the seed of a plant to the eyes of God, and to the understanding of man, there exists, though in an invisible way, the perfect leaves, flowers, and fruit thereof: (for things that are in posse to the sense, are actually existent to the understanding.) Thus God beholds all things, who contemplates as fully his workes in their epitome, as in their full volume, and beheld as amply the whole world in that little compendium of the sixth day, as in the scattered and dilated pieces of those five before.58

Religio Medici, in its butterfly way, does not settle for very long on any topic, from its opening doctrinal tease to his innocent brushes with heresy and on to his labyrinthine dealings with nature and the borderlands of science. The work occupies a perplexing terrain, with its admixture of the personal, the theological, and the scientific. Its style continually overwhelms, if indeed it does not become, its subject matter. It is prose which, in its rhetorical curvature, in what may be its theology of language, dazzles like few other writers, a prose which is rich, thick, and clogs the arteries.

Barbour, Reid, and Claire Preston, eds. Sir Thomas Browne: The World Proposed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Croll, Morris. Style, Rhetoric, and Rhythm (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966).

Cunningham, Andrew. ‘Sir Thomas Browne and his Religio Medici: Reason, Nature and Religion’, in Ole Peter Grell and Andrew Cunningham, eds., Religio Medici, Medicine and Religion in Seventeenth Century England (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996).

Dear, Peter, ed. The Literary Structure of Scientific Argument: Historical Studies (Philadephia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991).

Fish, Stanley. Self-Consuming Artifacts: The Experience of Seventeenth-Century Literature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972).

Killeen, Kevin. Biblical Scholarship, Science and Politics in Early Modern England: Thomas Browne and the Thorny Place of Knowledge (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009).

Murphy, Kathryn, and Richard Todd, eds. ‘A man very well studyed’: New Contexts for Thomas Browne (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

Osler, Margaret J., ed. Rethinking the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Preston, Claire. Thomas Browne and the Writing of Early Modern Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Shapin, Steven. A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).