4

The Female Brain as Empathizer:

The Evidence

Styles of Play

Even at a very early age, children demonstrate gender differences in their abilities to empathize. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than when they are at play. Indeed, children as young as nineteen months tend to prefer a playmate of the same sex, which is believed by some people to reflect the different social styles of the two sexes: children may be selecting a partner whose social style meshes most easily with their own.1

Little boys are more physical when they want something than are little girls. Consider this example: when a group of children is given a toy movie player to play with, boys tend to get more than their fair share of looking down its eyepiece. They will just shoulder the girls out of the way: they have less empathy and are more self-centered.2 If you put girls together with the same toy, the girl who ends up with more than her fair share gets there not by using such obvious physical tactics, but rather by verbal skills. She will bargain and persuade rather than push. This example demonstrates that, on average, young girls show more concern for fairness than boys do, and that even when a young girl’s self-interest drives her, she will use mindreading to manipulate the other person into giving her what she wants.

Here’s another example, which may strike many parents as familiar. Leave out some of those big plastic cars that children can ride on. You will soon see that young boys tend to play the ramming game: they deliberately drive the vehicle into another child. The young girls ride around more carefully (when they can get their hands on the vehicles—the boys tend to hog them), avoiding the other children as much as they can.3

American psychologist Eleanor Maccoby calls the boys’ behavior “roughhousing,” a term that includes wrestling and mock fighting. I am sure you will recognize this description of four-year-old boys horsing around:

They bump, wrestle, and fall on to one another. One child pushes another back and forth in playful tussles . . . making machine gun sounds, and chasing one another around with space guns and spray bottles . . . Boys put clay into one another’s hair . . . pretend to shoot one another, fall dead and roll on the floor.

Maccoby explains that all this rough stuff is not simply a sign that boys are more active: girls are just as active when there are other kinds of toys to play with, such as trampolines and skipping ropes. She also makes it clear that rough-housing is not aggression; instead it is a good-natured trying out of each other’s toughness. This male style of play could be a lot of fun if you are a boy who enjoys the same thing. Moreover, if a playful component hurts or is intrusive, it needs lower empathizing in order to carry it out. Girls tend to react very differently. If it happens once, she may take it in good spirit. But if it happens repeatedly, the horsing around can feel insensitive.4

Of course, mock fighting is not always just playful. Sometimes it can be agonistic—not full-blown aggression, but fairly close to it, such as threatening others, or getting into conflict. On average, boys produce much more agonistic behavior, and shockingly, you can see these differences from as early as two years old.

As we saw earlier, little boys also tend to have more trouble learning to share toys. In one study, young boys showed fifty times more competition, while girls showed twenty times more turn-taking. These are everyday examples of large sex differences in empathizing.5

Antisocial Conduct Disorder

A small number of boys end up in the clinics of child psychiatrists where they are diagnosed with “conduct disorder.” What a wonderful Victorian word: conduct. But this word masks the fact that these children do not merely have a problem with the niceties of the rules of etiquette, such as which fork to use at a posh dinner party. Sometimes such children are described as “hard to manage,” which may be a more accurate description. Such children tend to get into a lot of fights. They tend to perceive others as treating them in a hostile or aggressive way, even when to the reasonable observer there was no definite sign of hostility intended. This is an example of inaccurate empathizing: the child misjudges another person’s intentions and emotions. Such misattribution of hostile intent is more common in boys.6

Concern and Comforting

Baby girls, as young as twelve months old, respond more empathically to the distress of other people, showing greater concern for others through more sad looks, sympathetic vocalizations, and comforting behavior. Interestingly, this echoes what you find at the other end of the age range, where far more women than men report that they frequently share the emotional distress of their friends. Women also show more comforting behavior, even of strangers, than men do.7

Theory of Mind

A number of studies suggest that by the age of three young girls are already ahead of boys in their ability to infer what people might be thinking or intending—that is, in using a “theory of mind.” This is the cognitive component of empathy that I described in Chapter 3. For example, if you ask children to judge how a character in a story might be feeling on the inside, compared to the emotion that the character is showing on the outside, you will find that girls score more highly than boys. Or when asked how someone should look in different situations, for example if someone gives you a present that you don’t like, girls are better at judging when it would be better to suppress showing an emotion, so as not to hurt the other person’s feelings. Or when asked to judge when someone might have said something that was inappropriate—when someone committed a faux pas—girls from the age of seven score more highly than boys, which again indicates that females are better at empathizing.8

Judging Emotion

Women are more sensitive to facial expressions. They are better at decoding non-verbal communication, picking up subtle nuances in tone of voice or facial expression, and using them to judge a person’s character.

The most well-known test of sensitivity to non-verbal cues of emotion is called the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (PONS). On this test, women are more accurate in identifying the emotion of an actor. This sex difference holds up in countries as varied as New Guinea, Israel, Australia, and North America.9

Sally Wheelwright and I developed a test of empathizing in which the person is presented with photographs of facial expressions of emotions— but only the section of the face around the eyes. We call it the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. (Have a look at this, as it is reprinted in Appendix 1.) The task is to pick which word, from the four words that surround each photo, best describes what the person is thinking or feeling. Clearly, all you have to go on is the information around the eyes. We designed it in this way to make it a challenging test and to bring out the range of individual differences in empathizing. People are very good at the test, even though they believe they are going to find it really tough. It is a “forced choice” test, so even if you are unsure which word is correct, you are encouraged to guess. And as you may have anticipated, women are more accurate on this task.10

Relationships

We all value social relationships, but are there differences in what each sex values about other people? Women tend to value the development of altruistic, reciprocal relationships. Such relationships require good empathizing skills. In contrast, men tend to value power, politics, and competition. This pattern is found across widely different cultures and historical periods, and is even found among chimpanzees.11

A similar pattern is found among children, too. Girls are more likely to endorse cooperative items on a questionnaire (“I like to learn by working with other students”) and to rate the establishment of intimacy as more important than the establishment of dominance. Boys are more likely than girls to endorse competitive items (“I like to do better work than my friends”) and to rate social status as more important than intimacy. When three- to five-year-olds are asked how money should be distributed, more girls suggest sharing it out equally. This suggests that, on average, males value affirmation of their social status (their place in the social hierarchy system), while females value the supportive experience (empathy) that derives from being in an equal relationship.12

Sally Wheelwright and I put together the Friendship and Relationship Questionnaire (FQ) as a further way of testing this sex difference. We wanted to discover whether, in social relationships, men and women focused on the other person’s feelings, or simply on the shared activity. Only the former involves empathizing. We found that, on average, women are more likely to value empathizing in friendships, while men are more likely to value shared interests. Other studies have reported similar results.13

Jealousy and Fantasies

If you ask men and women what their partner would have to do to trigger jealousy, you find that the triggers are very different for the two sexes. Men report relatively more subjective distress (and show more physiological distress) to a partner’s imagined sexual infidelity. In contrast, women tend to report that imagining their partner becoming emotionally involved with someone else is what would trigger them to feel jealous. These differences seem to suggest that women focus more on the emotional aspects of relationships.

If you ask people about their sexual fantasies, these too reveal how the two sexes think differently about relationships. Women tend to think about the personal and emotional qualities of their fantasy partner, which suggests that they are unable to turn off their empathizing abilities even when they are thinking about sex. In contrast, men tend to focus on the physical characteristics of their partner. Empathizing may or may not figure in their fantasies, which suggests that it is something that they can turn off to varying degrees.14

Rape

The fact that some men are capable of sexual pleasure during rape, which by definition involves treating a person with zero empathy, demonstrates that for some men sex is entirely independent from an intimate, reciprocal emotional relationship. Consider the phenomenon of “drug rape,” where a man poisons a woman’s drink with an odorless, tasteless, colorless drug that renders her comatose for up to six hours, so that he can have sex with her as an object. Or consider that in Norway, during the Second World War, there were children raised in orphanages who were the product of sex between Nazi soldiers and Norwegian women. These children were deliberately bred for the sole purpose of spreading Aryan genes. There was no emotional relationship between the soldiers and the women they impregnated. The way these male soldiers thought about these women is sobering evidence for the theory that there are sex differences in empathy. Even more relevant is the fact that Norwegian men queued up for hours to bribe the guards of the orphanage with liquor to let them have sex with these children. Can men’s sex drive really lead them to simply ignore people’s feelings? Apparently so.

Fortunately, most men are not so lacking in empathy that they could hurt someone to this degree. But the existence of male rape suggests a sex difference in empathy at the extremes. Lower empathy is obviously not the only cause of rape, but it is likely to be a significant factor contributing to its occurrence.

Psychopathic Personality Disorder

Let’s consider some seriously unpleasant people, those diagnosed in adulthood as psychopaths. These are people that you really do not want to have as your next-door neighbor. They are the ones who do really nasty things, like holding someone hostage and then cutting them up, or conning an old lady into handing over her life savings. Such people tend to be male. It is presumably uncontroversial that such individuals are low in the affective component of empathy. However, some studies suggest that they have no difficulty with the cognitive kind of empathy, which is why they can lie without feeling any guilt.15

Aggression

Let’s go back to the ordinary person. Aggression, even in normal quantities, can only occur because of reduced empathizing. You just can’t set out to hurt someone if you care about how they feel. If you feel angry, or jealous, however, these emotions can lower your empathy. In some circumstances your empathy is lowered for long enough to fail to inhibit aggression. Good empathy acts as a brake on aggression, but without it, aggression can occur. During aggression you are focused on how you feel, more than on how the other person feels.

Both sexes of course show aggression, and as such both are capable of reduced empathy at times. But you find a sex difference in how aggression is shown. Males tend to show far more direct aggression (pushing, hitting, punching, and so on). Females tend to show more indirect (or relational, covert) aggression. This occurs between people without them touching each other, or behind people’s backs, and it includes things like gossip, exclusion, and bitchy remarks. Indirect aggression is, of course, still aggression. However, it could be said that to punch someone in the face or to wound them physically (the more male style of aggression) requires an even lower level of empathy than a verbal snipe (the more female style of aggression).16

Even if you disagree with this rather simplistic distinction—after all, some people think that subtle verbal attacks can hurt as much as sticks and stones—it is still the case that indirect aggression (the more female kind) needs better mindreading skills than does direct aggression (the more male kind). This is because its impact is strategic: you hurt person A by saying something negative about them to person B. Indirect aggression also involves deception: the aggressor can deny any malicious intent if challenged.17

Murder

Let’s talk murder now, the ultimate in lack of empathy. It is a shocking statistic that in pre-industrial societies one in three young men is killed in a fight, between men. They tend to be men who feel that their reputation has been disrespected. In order that such “loss of face” does not lead to a loss of social status, they stand up for themselves. They send out the signal “Don’t f*** with me.” And how better to signal that you are a man of action, and not just words, than to kill someone. If you kill someone in a competitive fight, your social status goes rocketing up. Whereas in the developed world a murderer is considered to be a vicious person who should be locked up, in pre-industrial societies a murderer (following the provocation outlined above) is someone who gains respect.

Regarding sex differences in murder, Daly and Wilson wrote, “There is no known human society in which the level of lethal violence among women even approaches that among men.”18 They analyzed homicide records dating back over 700 years, from a range of different societies. They found that male-on-male homicide was thirty to forty times more frequent than female-on-female homicide. Studies show that in a range of different societies, two-thirds of male homicides do not occur during a crime but simply when there is a social conflict, in which the man feels he has been “dissed” (disrespected). Such homicides are carried out to save face and retain status.19

This sex difference in aggression and murder could be interpreted as a marker showing that empathizing is lower in males. Of course, the increased rates of physical aggression and homicide among males could reflect several other factors (such as differences in risk-taking), but reduced empathy may be one of the contributing factors. Equally, the male preoccupation with social status may be a useful marker of a higher systemizing drive in males. After all, social hierarchies are systems.

Let’s have a closer look at what goes on in these social hierarchies.

Establishing Dominance Hierarchies

In a group, boys are quick to establish a “dominance hierarchy.” This might reflect their lower empathizing and their higher systemizing skills, because typically a hierarchy is established by one person pushing others around, uncaringly, in order to become the leader.

It is not dissimilar to the way our male non-human primate relatives behave. For example, in a troop of monkeys or apes, males rapidly recognize their place in the system. When two males come across something valuable—food, shelter, or a mate—each male immediately knows whether to go for it, or whether to defer to the other male. How does each monkey know if they are above or below another monkey in the social group? Social hierarchies are not established in any mysterious way. They are not established by God on high handing down a ticket with a number on it, from one to a hundred. Hierarchies are established in a far more straightforward way: by competition. Two male primates (human or non-human) who have both seen a desirable object will face each other. Sometimes it will be clear from the outset that one defers to the other. If not, the indirect combat starts. They act tough, and make threatening gestures. They may do “the walk” (walking back and forth, eyeing and sizing each other up), until one of them backs down. Rarely does it become direct combat, but it will accelerate to this if the agonistic behaviors do not cause one of the primates to retreat.

This indirect confrontation, however ritualized, does not need to happen between every pair of males in the group. Other members of the group observing a few such interactions rapidly learn that, in any dispute between A and B, A is superior because B backs down. When the combat is between B and C, the observers learn that B is superior because C backs down. Then the primate uses the inexorable logic of transitive inference. (You may be amazed to discover that even a monkey can compute this logic.) It goes like this: if A is superior to B, and B is superior to C, then A is superior to C. As clear as night follows day, such logic ripples right through the group. This “if-then” rule-based logic is an instance of systemizing (which we look at in detail in the next two chapters). When one sees the same thing going on in humans and monkeys, one realizes that such behavior must have an evolutionary past. More on that in Chapter 9. Let’s get back to sex differences in human social hierarchies.

Even among young children in nursery schools, there are more boys at the top of these dominance hierarchies. They are pushier, and they back down less often. In addition, the hierarchies are better established among the boys. The boys spend more time monitoring and maintaining the hierarchy. It seems to matter more to them.

You can test this. Ask a class of children who, of child A or B, determines what happens (who gets the toy, who gets to choose the game, who gets to choose where to sit, who picks the team, and so on). You will find there is better agreement among the boys. This suggests that they notice social rank, that it means a lot to them. Even in pre-school, little boys feel it is important not to appear weak, so as not to lose rank. They care about their own feelings and image more than someone else’s, even if this means leaving the other person feeling hurt.

So here we see a trade-off between empathizing and systemizing. To be too empathic would be to let others walk all over you, and you would sink in the social system. To assert your rank, or even try to climb in the system, is to gain in status, often at the expense of someone else. Boys seem more willing to pay the price of putting themselves first, for the obvious personal benefits.

Young girls also establish social rank, but more often this is based on other qualities than simply acting tough. All of this is very relevant to empathizing, of course, since to insist on being right and putting someone else down is to care first and foremost about yourself, not about the other person.

Once again, boys seem to be less empathic than girls.20

Summer Camp

If I tell you about anthropologist Ritch Savin-Williams’s remarkable study of a teenage summer camp, you will see this sex difference under a magnifying lens. When you read the next few passages, memories of your childhood that you might wish were forgotten could come back to you. It certainly reminds me of my days as a summer camp counselor at Lake Wabikon, in North Bay, Ontario.21

The teenagers arrived in the camp, and were put into single-sex cabins with strangers of the same age. As you might imagine, in the cabins dominance hierarchies were established. Some of the tactics used to achieve this were similar in the boys’ and in the girls’ groups. These tactics included ridiculing someone in the cabin, name-calling, and gossiping. This nasty behavior had an important pay-off: those who ended up higher in the dominance hierarchy also ended up with more control over the group.

So the depressing but realistic conclusion is that nastiness (or lower empathy) gets you higher socially, and gets you more control or power. For example, the teenagers who emerged as natural group leaders had more influence over which activities the group pursued, and got first choice on where they wanted to sleep. They even got offered seconds of food before anyone else.

But regarding the tactics used to climb the social hierarchy, that was as far as the similarities between the sexes went. In contrast, the differences between the sexes were quite startling.

Let’s first have a peek into the boys’ cabins. Put your eye to the keyhole to see the male mind at work. In some of the boys’ groups, there were some boys who made their bid for social dominance within hours of arriving in the cabin. No point in wasting time, you might think. Here is how they did it: they would pick on someone in the cabin, not only by ridiculing them but also by picking on them physically, and in full view of the others.

Imagine a child who is just unpacking his rucksack and who is already feeling a bit homesick. He is reading a sweet little card his mother slipped in with his wash bag. Out of the blue, some boy jumps on him, gives him a push and calls him an insulting name. From the perspective of the boy who pushes his weight around in this way, a clear message is sent out to the whole cabin that he is boss. From our perspective of spying through the keyhole, it would be reasonable to wonder if this bully is down a few points in empathy.

In the cabin I supervised at summer camp, the poor child who was picked on was called Stuart. He was a sweet child, scapegoated because he was a bit overweight. Poor old Stuart. As soon as my back was turned, the self-appointed leader of the cabin reverted to planning nasty tricks to play on him. You no doubt remember the kinds of pranks from your own summer camp or school days. Poor Stuart was subjected to that awful trick where other children put his hand in a bowl of water while he was asleep at night, since the local folklore was that this guaranteed that he would urinate in his bed. Were they thinking about Stuart’s feelings of embarrassment and victimization, or just their own tough humor, when they did that?

On another occasion, they did the unthinkable. They put a hood over Stuart’s head, so that he was unable to see at all. Then they lifted him up and told him they were putting him on a chair. They put a rope around his neck that he was able to feel. They told him that the rope was tied to the ceiling, and that if he attempted to step off the chair he would hang himself. Unknown to poor blindfolded Stuart, he had not been put on a chair at all. They had simply lifted him up and put him back down on the floor. And unknown to Stuart, the rope was not attached to the ceiling but was simply loosely draped around his neck. But that did not stop Stuart feeling terrified at the prospect that if he did not do what they said—namely, stand there on the “chair” in his hooded state—he would hang himself. The boys who had done this nasty trick then left him there, and there he stood, paralyzed with fear and misery at this bullying, until I came into the cabin and found him, some hours later. Knowing afterwards that he had all along simply been standing safely on the floor, in no danger of dying at all, did nothing to reduce the trauma of this experience.

Now let’s get back to the experiment and spy through the half-drawn curtains of the girls’ cabins, to see the female mind at work. The girls tended to wait at least a week before starting to assert dominance. For them, being nice initially, which helped build friendships, was an equally important priority. Even when some girls did start to hint that they were in control, they mostly did this through subtle strategies—the odd put-down (in words), or the withholding of verbal communication or eye contact. It was rare for a girl to use physical force.

For example, a dominant girl would simply ignore a lower-status girl’s suggestions or comments. She might even act as if the lower-status girl was not there, by not looking at her. Eye contact or social exclusion are powerful ways of exerting social control. By dishing out a little or no attention, you can make someone feel invisible, or even of no importance. I am sure that you recognize these tactics.

The girls’ verbal means for establishing dominance were usually indirect. In one example, one girl suggested to another that she “take her napkin and clean a piece of food off her face.” This apparently caring attitude actually draws attention to the other girl’s clumsiness. A boy would simply call the other boy a slob, and invite the other boys to join in a group-ridiculing session of the victim. Both tactics may have the same effect, but the girls’ method is more sophisticated.

Such tactics happen so fast that you can hardly pin down how it is that one girl can end up looking superior, and the other looking stupid. Girls more often use tactics such as saying “I won’t be your friend any more” or they more often spread negative gossip about a girl—so-called “social alienation.” They use more subtle verbal persuasion or even misinformationbased strategies. They are using a “theory of mind” even if they are not fully empathizing. Boys, in contrast, more often use a direct means of aggression: yelling, fighting, and calling each other blatantly offensive names.

You might say that the boys’ method is more like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. A boy in the same situation is more likely to go for the immediate goal, knowing that the net effect will work out in his favor (he rises in the group, while the other child sinks), even if he makes an immediate enemy in the process. But when a girl decides to “put someone else down,” she thinks of how this could be done almost invisibly, so as not to risk acquiring the reputation of being a bully. If confronted, the girl can always say that the comment was not intended to be offensive, or that the lack of eye contact was unintended. In this way, she can preserve her reputation of being a nice person even when she has been a touch nasty.

As we saw in the study using the Friendship and Relationship Questionnaire (FQ), girls value intimacy. So this female strategy fulfills both aims: achieving social status without jeopardizing intimacy in her other relationships. Who wants to be intimate with someone who has a reputation for being nasty? The nastiness has to be covert, fleeting, and hard to pin down. In the boy’s case, it is clear that that punch is intended. The signal value of the physical force is unambiguous, and the message conveyed is that the aggressor does not much care if the victim feels hurt and offended, nor if it is at the cost of intimacy in other relationships. The overriding aim is control, power, and the access to resources that this brings: reduced empathizing again. (In Chapter 9 we discuss why males and females might have such different priorities in their social lives.)

In the summer camp study they found that, once a boy was put down in this rather blunt way, other (lower-status) boys in the cabin jumped in to cement this victim’s even-lower status. This was a means of establishing their own dominance over him. This reminds us that dominance hierarchies are dynamic, and that boys tend to be more often on the watch for opportunities to climb socially. So much for empathizing with the victim. More like, kick a guy when he is down. This was true from the lowest to the highest member of the social group.

The girls were also sensitive to opportunities to gain rank, but again the tactics were different. Girls tended to explicitly acknowledge the leadership of another girl, “sucking up” to the dominant girl. They would use flattery, charm, appreciation, and respect. For example, a less dominant girl would ask a more dominant one for advice and support. Or the less dominant one would offer to brush and arrange the dominant one’s hair. (If these were non-human primates, consolidating their position in the social group, we would call it “grooming.”)

Another difference is that the boys’ dominance hierarchies tended to last the whole summer, whereas the girls’ groups typically split up much sooner. The result of this was that fairly soon the girls would spend more time in groups of two or three, chatting together in a less rivalrous way, or getting intimate with their “best friend.” The boys instead remained largely involved in group-competitive activities against other groups, with the leader directing them.

I have spent a long time on this summer camp experiment because there are obviously a lot of parallels we can draw out for many social situations: the classroom, the office, the committee, the playground. All of these social groupings develop their leaders, and leaders often need “fall guys” to stay on top. It is instructive to look at the role of increased mindreading among females and lower empathizing among males in determining a person’s ascent up the social ladder, even if it is a bit depressing.

The other conclusion to emerge from this is that boys are far less reticent about making someone feel less equal than them. They will not lose sleep over the feelings of the poor boy at the bottom of the pile. They even enjoy their higher status. They are also more ready to physically hurt someone, or explicitly hurt their feelings, to increase their status.

Breaking Into a Group of Strangers

Two other ways to reveal a person’s empathizing skill are to see how they (as a newcomer) join a group of strangers, and to see how they (as a host) react to a new person joining their group. This has been cleverly investigated in children by introducing a new boy or girl to a group who are already playing together.

Let’s start with observing the newcomer. If the newcomer is female, she is more likely to stand and watch for a while in order to find out what is going on, and then try to fit in with the ongoing activity, for example by making helpful suggestions or comments. This usually leads to the newcomer being readily accepted into the group. It shows sensitivity, a desire not just to barge in and interrupt when this might not be wanted: female empathizing.

What happens if the newcomer is a boy? He is more likely to hijack the game by trying to change it, directing everyone’s attention on to him. This is less successful than the female style. Children who use this more male style are less likely to be welcomed by the group (unsurprisingly). I mean, would you want someone who you did not yet know to just walk in and take over? Boys tend to act as if they care less about whether others think they are nice, and care more about whether others think they are tough. This fits with the male agenda of climbing the social hierarchy. This newcomer style in males reveals their lower empathizing and higher systemizing.

Now let’s switch perspective and look at the children who are already part of the group. How do they react as hosts to the stranger who is trying to join in? It turns out that even by the age of six, girls are better at being hosts. They are more attentive to the newcomer. Boys often just ignore the newcomer’s attempt to join in. They are more likely to carry on with what they were already doing, perhaps preoccupied by their own interests, or their own self-importance.

Now let’s put these two findings together. The natural consequence of both the newcomer’s and the host’s strategies is that, if you are a girl, it is easier to join an all-girls group. Girls as hosts show higher levels of emotional sensitivity to the newcomer’s predicament. And girls as newcomers show higher levels of emotional sensitivity to the host. Boys, in contrast, do not appear to care at all about the newcomer’s or the host’s feelings. As Eleanor Maccoby observes, no wonder boys and girls spontaneously segregate into same-sex peer groups: their social styles are so different.22

Intimacy and Group Size

Recall that on the Friendship and Relationship Questionnaire (FQ), the two sexes have different agendas in relationships. The female agenda seems to be to enjoy an intimate, one-to-one relationship. Young girls, on average, are reported to show more pleasure in one-to-one interaction. They are more likely to want reciprocal friendships, and to express intimacy. For example, girls are more likely to say sweet things to one another (things you hardly ever hear between boys), or caress or arrange each other’s hair, or sit close to or touch the other person. Girls are more likely to have their arm around the other person, and to make direct eye contact.

Another difference is the concern that girls show about the current status of their friendships, and about what would happen if their friendship broke up. And breaking up is more often used as the ultimate threat: “If you don’t do this, you won’t be my friend.” Girls, on average, are more concerned about the potential loss of an intimate friendship.

Girls in later childhood spend a lot of time talking about who is whose best friend, and get very emotional if they are excluded from relationships in the playground. Sulking is not uncommon. For girls, just as it is for many women, the important thing is to spend time communicating and nurturing their close relationships, without any necessary focus on an activity.

Girls also tend to spend more time cementing the closeness of their relationships by disclosing secrets, and by confessing their fears and weaknesses. Boys, in contrast, reveal their weaknesses less often, and in some cases never. Paradoxically, although increased self-disclosure between girls leads to closer relationships, it also leaves them more open to gossip—there is more fuel for gossip, as it were. Girls seem to be more willing to take this gamble, however, since the pay-off of self-disclosure is intimacy. The upshot of all this is that relationships between girls, and their break ups, are more emotional.23

Most boys in late childhood have relationships based on the game that they want to play. So if the game is soccer, they select one group to play with; if the game is skateboarding, they may select another group of friends. This is not so different for many men, who may play poker with one set of friends, and golf with another set.

This difference in styles of play between girls and boys suggests that girls tend to be more preoccupied with the emotional aspects of relationships, either to become close to someone, or to exclude others from getting between them and their “best friend.” In contrast, boys are more preoccupied with the activity itself and its competitive aspects.

The flip side of the coin is that boys’ friendships, on average, are less intimate. There is less mutual self-disclosure, less eye contact, and less physical closeness. By the age of eight or so, if boys touch each other at all, it tends to be with an affectionate punch, or to give each other a “high five.” While the female agenda is more often directed toward intimacy, the male one is more often directed toward coordinated group activity, based on mutual interests. For example, the boys who enjoy sport, or rock music, or computers magnetically find each other and form themselves into groups. Boys’ main priority seems to be to join a group based on a shared activity. Once inside a group, there is a further priority to establish their individual rank in the dominance hierarchy that will emerge.

An impressive way of climbing in rank, as a welcome alternative to being nasty, is simply to be good at an activity: to be expert, knowledgeable, and skilled at a particular system. This earns the respect of the others, and it cements your place in the group activity by being a valued, even indispensable, member of the group. It means that when competition becomes an issue—that is, when there are only a fixed number of places in the group or on the team—you will guarantee yourself a place, and remain in the safety of the group. The less-skilled losers, as it were, by definition end up as outsiders, with all that this brings (less access to resources and support). Both of the male strategies used to acquire social status—the impressive route and the aggressive route—share the same underlying feature: being competitive.

These different social agendas between the sexes have implications for group size, and for degrees of intimacy and empathy. Males may spend their time in larger groups, depending on the nature of the activity. Females may network more, but tend to devote more time to intimacy with a small number of people. The male social agenda is more self-centered in relation to the group, with all the benefits this can bring, and it protects one’s status within this social system. The female agenda is more centered on another person’s emotional state (establishing a mutually satisfying and intimate friendship).

Such statements are, of course, open to misunderstanding. Males also have good friends, and these are often close and confiding. We are only talking about differences in degree, not absolute differences. And as with all of these psychological studies, we are only talking about group averages, rather than individuals.24

Pretend Play

We have already looked through a few windows into sex differences in empathizing, but do these differences in play continue as children grow older? Boys tend to play group games (such as soccer and baseball) much more than girls do. This is partly a sign of the importance of group membership to boys, and partly a reflection of their interest in rule-based activities. (Just think of how rule-based a system baseball is, both in terms of the rules of the technique and the rules governing play.) And an astonishing 99 percent of girls play with dolls at age six, compared with just 17 percent of boys. Playing with dolls is typically the opposite of rule-based activity, the themes being open-ended and usually involving an enactment of caring, emotional relationships.

When children engage in pretence during play, this is an even more specific window into empathizing. For example, in social pretence, one must imagine what another person is imagining. This is a big leap. When a child watches mommy soothing a doll, the child has to keep track that this is all just in mommy’s mind and that mommy is imagining the doll’s mind. In reality, dolls do not need soothing. This is a double level of empathizing: imbuing the doll with feelings, in mommy’s mind. Girls seem to be more prone to this than are boys.

The content of children’s pretend play is also relevant here. Girls’ pretence tends to involve more cooperative role-taking. They say things like, “I’ll be the mommy, you be the child,” and they show more reciprocity (“Now it’s your turn”). It is as if, within the pretence, they are making space for another person, sensitively adjusting their behavior to accommodate the other person.

In this way they are showing sensitivity to how the other person will feel if they are being included or excluded, being controlled or free, being dominated or treated as an equal. Girls also tend to ensure that the other person understands where the imaginative pursuit is leading. All very empathic.

In contrast, boys show more solitary pretence. Even if it is social, their pretence often involves a lone superhero (for example, Batman, Robin Hood, Superman, or Harry Potter) engaging in combat. Mortal combat. Such play typically involves guns, swords, or magical weapons with seriously destructive powers. As any parent knows, if toy guns or swords are not available then boys will use anything as a substitute for them. But the aim of the pretence is to eliminate the other person, the deadly enemy, not to worry about his feelings.

There is the victor, and there is the vanquished. This is certainly evidence of an ability to pretend, but the focus is on the imagined self ’s strength and power, rather than on being empathic. This male preoccupation with power and strength again suggests that males are less concerned with a sharing of minds and more interested in social rank. Who will win and who will lose. You see the same thing when children tell make-believe stories. In their narratives, boys focus more on lone characters in conflict. In contrast, girls’ stories focus more on social and family relationships.25

Communication

Listening to people chat is another rich source of evidence for empathy skills. The following section is quite long because there is a lot of evidence for sex differences in communication, across a large number of settings and age ranges.

Girls’ speech has been described as more cooperative, more reciprocal, and more collaborative. In concrete terms, this is also reflected in girls being able to keep a conversational exchange with a partner going for longer. It is not to do with how long the conversation is overall, since the conversation of young girls might be quite fragmented. Rather, it is to do with how long an exchange continues, in which the speaker takes turns and maintains a joint theme. Girls, on average, use more of certain kinds of language devices. For example, they use “extending statements” (such as “Oh, you mean x”) and “relevant turns” (such as “Oh, that’s interesting . . . ”), which serve to build on something the other person has just said.

Girls often extend dialogue by expressing agreement with the other person’s suggestions. When they disagree, they are more likely to soften the blow by expressing their opinion in the form of a question, rather than an assertion. This comes across as less dominating, less confrontational, and less humiliating for the other person. For example: “You may be right, but could it also be that . . . ?” or “Oh. I’m sure you’re right, but I saw it a bit differently.” In these examples, the speaker makes space for the other’s point of view, and makes it easier for the other person to save face because they feel that their point has been accepted, respecting a difference in opinion.26

The male style is more likely to go along these lines: “I’m sorry, but you’re wrong,” showing no respect for the other person’s different opinion Or they may be even more blunt: “You’re wrong.” Indeed, what in a female exchange might be seen as a difference of opinion is more likely to be interpreted by males as a matter of fact, where there can only be one correct answer—the speaker’s. If the other person makes a suggestion, boys are more likely to reject it out of hand by saying, “Rubbish,” or “No, it’s not,” or more rudely, “That’s stupid.” It is as if the more male style is to assume that there is an objective picture of reality, which happens to be their version of the facts; that if their beliefs are true then there can only be one version of the truth. The more female approach seems to be to assume from the outset that there might be subjectivity in the world. Therefore, they make room for multiple interpretations, each of which might have an equal claim to being a valid viewpoint.

Women are much more prepared to say when they feel hurt or offended by the other person in the conversation, and will also talk to each other when they feel offended by somebody else. Men are more likely to simply note an offense and withdraw contact, rather than working at repairing the relationship through conversation.

Girls express their anger less directly, and propose compromises more often. And in their talk, they are more likely to attempt to clarify the feelings and intentions of the other person. They also make softer claims, and use more polite forms of speech, avoiding the blunter forms of powerassertion such as yelling or shouting. In contrast, boys in middle childhood and adolescence produce more challenges in a direct assertion of power. When there are disagreements, boys are less likely to give a reason for their argument, and instead simply to assert it.27

Imperatives (direct commands, such as “Do this” or “Give that to me”) or prohibitions (“Stop it” or “Don’t DO that”) are more common in boys’ speech. These sorts of “domineering exchanges” are also more likely to end up in conflict. A good empathizer would worry that to order someone to do something is likely to make them feel inferior and devalued, and would avoid such speech styles. Girls are more likely to say, “Would you mind not doing that? It’s just that I don’t really like it,” referring to the other person’s feelings while at the same time clarifying their own.

Boys in early childhood are also more likely to do what psychologist Eleanor Maccoby calls “grandstanding”—in other words, giving a running commentary on their own actions, while ignoring what the other person is doing. It has been suggested that boys’ talk tends to be “single-voiced discourse.” By this it is meant that the speaker presents their own perspective alone. When two boys do this, conflict is likely to escalate.

In contrast, it is suggested that female speech style tends to be “doublevoiced discourse.” The idea is that while little girls still pursue their own objectives, each also spends more time negotiating with the other person, trying to take the other person’s wishes into account. Look at this example: “I know you feel x, but have you thought of y? I realize you might wish that z, but what if . . .” This female speech style reveals clear empathizing at work in conversation. The “facts” of x, y, and z are all prefaced by mentalstate words (feel, think, wish) that immediately set those facts in a multipleinterpretation framework, and make space for both viewpoints. All of these differences in conversational style are seen even more dramatically in middle childhood and in the teenage years.

Boys are also more “egocentric” in their speech, by which I do not mean the “single-voiced discourse” mentioned earlier. I mean that they are more likely to brag, dare each other, taunt, threaten, override the other person’s attempt to speak, and ignore the other person’s suggestion. They are also less willing to give up the floor to the other speaker.

Males more often use language to assert their social dominance, to display their social status, especially when there are other males around. Here’s how Eleanor Maccoby puts it:

Boys in their groups are more likely than girls in all-girl groups to interrupt one another; use commands, threats, or boasts of authority; refuse to comply with another child’s command; give information; heckle a speaker; . . . top someone else’s story; or call another child names.28

Girls, on the other hand, are said to show “socially enabling” language more frequently. Socially enabling language is speech that is used to ensure that all members of the group talk, and express their views and feelings, encouraging differences in perspective to emerge.29 Maccoby writes that girls in all-girl groups

are more likely than boys to express agreement with what another speaker has just said, pause to give another girl a chance to speak, or when starting a speaking turn, acknowledge a point previously made by another speaker . . . Among girls, conversation is a more socially binding process.

Men spend more time using language to demonstrate their knowledge, skill, and status. They are more likely to show off or try to impress. This leads to more interruptions by men in order to give their opinion, and to their showing less interest in the opinion of the other person. For women, language functions in a different way: it is used to develop and maintain intimate, reciprocal relationships, especially with other females. Women spend more time using language to negotiate understandings, to develop a relationship, and to make people feel listened to. Women’s talk often affirms the other person, expressing positive feelings for their friendship, whereas men shy away from telling each other how important they are to each other.30

Women in conversation will often include personal reference to each other’s appearance (their hair, their jewelry, their clothes) so as to praise the other’s looks. It is astonishing how rapidly this will happen, often within seconds of first meeting. Let’s say a husband and wife are visiting another couple. One of the women may open a conversation with her female friend by saying something like this:

Oh, I love your dress. You must tell me where you got it. You look so pretty in it. It really goes well with your bag.

Why do women do this, while men hardly ever do so? One view is that in this way women signal their feelings for the other person, again something that men do much less frequently. For example, the compliment can be taken as implicitly saying “I like you,” or “I think you’re pretty,” or “I think you’ve got good taste,” thus affirming the relationship itself. Another equally positive view is that women implicitly build each other up through mutual compliments, rather than putting each other down. Evidence for this positive view often comes in the reply from the person receiving the compliment, which might go like this:

Oh, thank you. You must come shopping with me to this new shop I’ve found in Covent Garden, where they have such beautiful new material and designs. You’d love the summer dresses. They’d suit your tan so well.

I have often commented to my male friends how stark this particular sex difference is. That is, that women will not only talk about each other’s appearances (men do this occasionally, too) but will actually follow through this chat by going shopping together, and even going into the same changing room to try on new clothes. When was the last time that you heard of two men going shopping together, getting into the same little booth, undressing in front of each other and asking each other whether this new shirt suited them? Homophobia may be what leads men to avoid such talk or avoid issuing such invitations to each other. But between women there is no suggestion of any sexual interest in such talk or in such shopping sprees. The shopping is often described as simple fun, and a chance to spend time together in a close way.

So this exchange of compliments could be taken as signaling a desire to get closer in the friendship, or to remain close, and it involves a fairly explicit removal of barriers between the two women (verbally undressing each other, as it were).

A less rosy view of this compliment exchange, however, is that women are drawing attention to appearances, reminding each other, and any observers, that appearances matter in the competition between women. This view is corroborated when compliments are laced with a fleeting but razorsharp aside, such as:

Oh, that dress makes you look so thin, I hate you! Look at how fat my butt is in this dress!

The reference to “hate” is typically delivered with jokey or affectionate intonation, but nevertheless might be revealing a touch of rivalry, jealousy, and competitiveness. Yet one thing is clear: often within seconds of a reunification with a woman friend, women talk about personal, even intimate, things (the size of body parts, and their dissatisfaction with their shape, etc.), and this demonstrates that women waste no time on impersonal dialog but immediately move the conversation on to the point where they can share personal feelings and closeness.

Women’s conversation also involves much more talk about feelings and relationships than men’s, while men’s conversation with each other tends to be more object-focused, such as discussion of sports, cars, routes, and new acquisitions. Let’s go back to my example of a husband and wife visiting another couple. While the women have quickly started to compliment each other and are talking about personal appearances, the two men’s opening gambit might go something like this:

How was the traffic on the M11? I usually find going up the A1M through Royston and Baldock can save a lot of time. Especially now they have the roadworks just beyond Stansted.

Male talk about traffic and routes is of course a clear example of talk about systems, but more on that in Chapter 6.

A study of the stories told by two-year-old children found that people were the focus in the vast majority of the stories told by girls but were the focus in only a small minority of the stories told by boys. By four years of age, every story told by girls was people-centered, but still only about half of the boys’ stories were. Girls seem to be far more people-centered than boys.

A well-substantiated sex difference in language content is found in selfdisclosure and intimacy. Whereas men and women do not differ in their willingness to self-disclose to a female conversation partner, men use far less intimate language when talking to another man. This mirrors the finding that I discussed in relation to girls’ and boys’ styles of relationships, and may reflect the pressure that men feel to appear in control. It is of interest that even when men are in conversation with a woman, and are talking intimately, they offer less supportive communication when the woman takes her turn to talk intimately. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to respond with words conveying that they have understood what the other person has said, offering sympathy spontaneously.31

Men tend to refer less frequently to their relationships, tending to live them through joint activities rather than talking about them. These sorts of conversational differences mirror the differences we saw between the sexes on the Friendship and Relationship Questionnaire (FQ).

Deborah Tannen documents the differences in how men and women talk with each other. In her book You Just Don’t Understand she wrote about her studies in the context of couples’ interactions. In Talking 9 to 5 she dealt with talk in the workplace. Her key finding is that there is a lot more informal chatting in the office among women, chat that is not work-related. She argues that this forms and reinforces social bonds. These in turn keep communication channels open so that any tensions that arise are then easier to defuse.32

Amusingly, Tannen finds that in the workplace men more often talk to each other about systems: technology (such as their latest power-tools, or computer, or music system), cars (such as the differences between one model and another: their engine capacity, fuel consumption, speed, or accessories), and sport (such as the best places to windsurf, or soccer rankings, or the big game last night, or their new golf clubs). Women talk to each other more often about social themes: clothes, hairstyles, social gatherings, relationships, domestic concerns and children. (Just like the magazines that men and women tend to buy at the newsstand, reflecting their different interests or what matters to them.) These differences are referred to as “guy talk” and “girl talk.” Not surprisingly, people find it easier to get to know someone if they are a member of the same sex, arguably because it is easier to establish an informal topic of mutual interest. It may also be because male and female humor differs, in the office at least: male humor tends to involve more teasing and pretend hostility, while female humor tends to involve more self-mockery.

These differences also affect how management operates at work. Female managers tend to soften the blow tactfully when delivering criticism, while male managers tend to be more willing to deliver direct criticism without sugar-coating the pill. Female management-style also tends to be more consultative and inclusive, ensuring that no one feels left out, while men’s management-style tends to be more directive and task-oriented. A final difference in women’s style of talk in the workplace is women’s use of “we” in describing work as a collaboration, while men will more often talk about “I” or “my,” acknowledging less often the role that others have played.

It seems reasonable to conclude this section as follows: differences in speech styles suggest that there are key differences in how self- and othercentered each sex is. The speech styles of each sex suggest that there are sex differences in how much speakers set aside their own desires to consider sensitively someone else’s. Empathy again.

Parenting Styles

Parenting style is another good place to test if women are more empathic than men. Here again, sex differences are found. Fathers are less likely than mothers to hold their infant in a face-to-face position. One consequence of this is that there is less exchange of emotional information via the face between fathers and infants. Mothers are more likely to follow through the child’s choice of topic in play, while fathers are more likely to impose their own topic.

Moreover, mothers fine-tune their speech more often to match what the child can understand. For example, a mother’s mean length of utterance tends to correlate with her child’s comprehension level, while fathers tend to use unfamiliar or difficult words more often. Finally, when a father and child are talking, they take turns less often. These examples from parenting again suggest that women are better at empathizing than men.

An experimental demonstration of this is seen in a study by Eleanor Maccoby and her colleagues. They used a communication task in which a parent and his or her six-year-old child were given four ambiguous pictures. The parent described the picture and the child was asked to pick out which of the four pictures was being described. Mother-child pairs were more successful than father-child pairs at identifying the intended picture, presumably because of women’s greater communicative clarity.33

Eye Contact and Face Perception

Do babies show sex differences in how people-centered and how objectcentered they are? There are claims that from birth, female infants look longer at faces, and particularly at people’s eyes, while male infants are more likely to look at inanimate objects.34 Interestingly, when you try to track down an original study to test this claim it is very hard to put your hands on any concrete data. I was fortunate enough to work with a talented Ph.D. student, Svetlana Lutchmaya, who tested this claim with one-year-olds.

Svetlana invited the infants into our lab, and filmed them while they played on the floor, and their mothers sat in a chair nearby. She then painstakingly coded all of the videotapes to ascertain how many times the infants looked up at their mother’s face during a twenty-minute period. She found that the girls looked up significantly more often than the boys did. And when she gave them a choice of a film of a face to watch, or a film of cars, the boys looked for longer at the cars and the girls looked for longer at the face.35

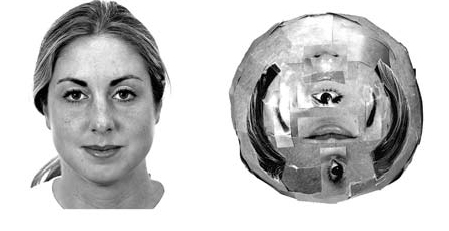

The face and mobile presented to newborns

fig 4.

Two other enterprising students of mine, Jennifer Connellan and Anna Ba’tki, decided to take this question a little further. They videotaped over 100 babies who were just one day old, in the Rosie Maternity Hospital in Cambridge, England. Little did these babies know what lay in store for them. No sooner had they emerged from the womb than they were recruited into this scientific study. The babies were shown Jennifer’s tanned Californian face, smiling over their crib. Her face moved in the natural way that faces do. They were also shown a mobile. But this mobile was no ordinary mobile. It was made from a ball the same size as Jennifer’s head, with the same coloring (tanned), but with her features rearranged, so that the overall impression was no longer face-like. Around the lab we called it The Alien. To make it look more mechanical, we hung some material from it that moved every time the larger mobile moved. In this way, we could compare the baby’s interest in a social object (a face) and a mechanical object (a mobile). Finally, in order for the experimenters to remain unbiased, mothers were asked not to tell the researchers the sex of her baby. This in- formation was only checked after the videotapes had been coded for how long each baby looked at each type of object.

So the question was, would babies look longer at Jennifer’s face, or at the mobile? When we analyzed the videotapes, we found that girls looked for longer at the face, and that boys looked for longer at the mobile. And this sex difference in social interest was on the first day of life.36

This difference at birth echoes a pattern we have seen right across the human lifespan. For example, on average, women engage in more “consistent” social smiling and “maintained” eye contact than does the average man. The fact that this difference is present at birth strongly suggests that biology plays a role. We return to examine this possibility in Chapter 8.37

The Empathy Quotient (EQ)

There are a number of questionnaires that purport to measure empathy. Many of these find that women score higher than men. My research team and I developed a measure in this area, called the Empathy Quotient (or EQ; have a look at it in Appendix 2), which also found that women score higher than men.38 We developed our test because of a worry that earlier tests were not “pure” tests of empathy, since they included items in their questionnaires that involved self-control or fantasy. If you take a look at the EQ you will see that the questions are intended to measure how easily you can pick up on other people’s feelings, and also how strongly you are affected by other people’s feelings. Figure 5 shows a schematic of the results we found on the EQ, for men and women.

As you can see, the female scores are positioned toward the right, and are higher up the scale than the male scores, which provides strong evidence that females are better empathizers. Note, though, that this test only collects information from self-reports, so the higher scores may just reflect that women are less modest. We think this is unlikely, since when we ask someone to fill out the questionnaire on behalf of another person that they know very well, we find that reports by others correlate very closely with self-reports. However, as this chapter indicates, to test the idea that females are better at empathizing it is important to look at a range of indicators to see if they provide converging evidence for this conclusion.

Male and female scores in empathizing

fig 5.

Language Ability:

An Alternative View of the Female Brain?

Females are clearly better than males at empathizing. But perhaps they are better not just at communication but at all aspects of language. When you look at even low-level language tests, females are superior in many of these, too. Before closing this chapter, we look at whether this is necessarily a problem for the empathizing theory.

But first, what is the evidence for sex differences in language? On average, women produce more words in a given period, fewer speech errors (such as using the wrong word), and perform better in the ability to discriminate speech sounds (such as consonants and vowels) than do men. Their average sentences are also longer, and their utterances show standard grammatical structure and correct pronunciation more often. They also find it easier to articulate words, and do this faster than men. Women can also recall words more easily. Most men have more pauses in their speech. And at the clinical level of severity, males are at least two times more likely to develop language disorders, such as stuttering.39

In addition, girls start talking earlier than boys, by about one month, and their vocabulary size is greater. It is not clear whether receptive vocabulary size (how many words a child understands) differs between the sexes, but it seems that girls use language more at an earlier age. For example, they initiate talk more often with their parents, with other children, and with teachers. This greater use of language by girls may not be seen when in the company of boys, whose effect is usually to render girls quieter or more inhibited.

Girls are also better spellers and readers. Boys tend to be faster at repeating a single syllable (e.g., ba-ba-ba), while girls tend to produce more syllables when the task is to repeat a sequence of different sounds (e.g., ba-da-ga). Girls are also better on tests of verbal memory, or recall of words. This female superiority is seen in older women, too, including those who are well into their eighties. The female advantage is even seen when the task is to recall a string of numbers spoken aloud (the Digit Span Test). Women are not better at the spatial equivalent of this test—where one is asked to tap a long series of blocks into the same irregular sequence as the experimenter.

Women taking medical school entrance exams do better on an assessment called “Learning Facts,” which you could think of as a verbal memory test. And women, given a lot of words read aloud, learn them more easily. Women also tend to cluster the words reported into meaningful categories, while men tend to report them in the order in which they were presented. Women are better at recalling the meaning of a paragraph, and this has been found in widely differing cultures—for example, in South Africa, America, and Japan. On a control test of recalling irregular nonsense shapes, where the shapes cannot be named, no sex difference is seen.40

In a landmark study that sparked a lot of interest, Bennett Shaywitz and his colleagues at Yale University found that certain regions of the prefrontal cortex of the brain, including Broca’s area, were activated differently in men and women during a language task. The subject was asked to decide if a pair of written nonsense words rhymed or not. About half of the women showed activation of Broca’s area in both the right and left frontal lobes, while the men only showed left hemisphere activation. The same research group has replicated its own work, finding a similar effect even if the task is simply to listen to speech sounds (though this has not been found in all studies).41

This short detour into differences in language competence tells us that the female brain may not only be a natural empathizer but also have a flair for language. Is this a problem for the characterization of the female brain in terms of superior empathizing? My view is that it need not be, for several reasons.

It is noteworthy that the very idea that females have better language skills has been questioned,42 whereas the idea that females have better empathy remains unchallenged. But let us accept it as true that they also have better language skills. First, it is possible that a female superiority in all these broader language skills may be part and parcel of developing good empathizing skills. Language skills (including good verbal memory) are essential in seamless chatting and establishing intimacy, to make the interaction smooth, fluent, and socially binding. Long pauses in conversation do not help partners to feel connected or in tune with one another.

Second, some measures of language, such as reading comprehension, may actually reflect empathizing ability. For example, girls tend to perform better than boys on reading achievement tests overall, but this is because they are particularly better at understanding social storylines, compared to non-social ones.43

Third, the greater emotional sensitivity in females is unlikely to be just a by-product of their better language skills, because we all know people who have excellent language skills but poor social sensitivity, or vice versa. I’m sure you can think of some people who are verbally fluent, but who won’t stop talking. The fact that you can’t get a word in edgewise suggests that their turntaking and empathy skills are at a lower level compared to their verbal skills.

Equally, you can probably think of someone who is a patient and sensitive listener, who responds very warmly and empathically to other people’s problems, but who is a person of few words. So good language ability need have nothing to do with good communication ability, or good empathy.

Indeed, a Darwinian view might be that rather than good empathy stemming from good language skills, it is the other way around. Females may have evolved better language systems because their survival depended on a more empathic, rapid, tactful, and strategic use of language.

But the safest conclusion at this point is that females are both better empathizers and better in many aspects of language use, and that the relationship between these two skills is likely to have been complex and two-way, both in ontogeny (development) and phylogeny (evolution): good language could promote good empathy (since the drive to communicate would bring one more social experience), and good empathy could promote good language (since social sensitivity would make the pragmatics of communication easier). But as domains, language and empathy are likely to be independent of each other.

So our main conclusion still stands: when you look at different aspects of social behavior and communication, a large body of evidence points to females being better empathizers. But what about the other main claim of this book? Are males better systemizers?