The major wars fought by the Romans in Italy and throughout the Mediterranean region during the time of the Republic resulted in a tremendous expansion of Roman territory. This creation of a territorial empire—control over lands previously ruled by others—had enormous consequences for Roman society. Many historians use the label “imperialism” to characterize Rome’s expansion of its power through war. That word comes from the Latin term imperium, the power to compel obedience, to command and to punish. The negative meaning attached to imperialism today comes primarily from criticism of the history of modern European states in establishing colonial empires in Africa and Asia. To decide how—or whether—this term is a fair description of Rome’s expansion requires us to try to understand what motivated the Romans in this process. As we will see, it is a controversial question to what extent Rome’s wars and conquest during the Republic were the result of a desire to profit from dominating others, or of the belief that preemptive wars to weaken or absorb perceived enemies were the best defense against attacks by others. Therefore, the most debated question about Roman expansion through war under the Republic concerns the intentions motivating it.

What is clear is that the great expansion of Rome’s territory and international power brought major changes to Roman society and culture. Rome’s overseas wars meant long-term contacts with new peoples that produced unexpected and often controversial influences on Roman life. To give one major example, increased interaction with Greeks led to the creation of the first Roman literature written in Latin. A different kind of change came from the effects on Roman values of the stupendous wealth and personal power that Rome’s upper-class leaders acquired as their rewards in the wars of conquest under the Republic. On the other hand, Rome’s expansion also meant that many of Italy’s small farmers, the main source of manpower for the army, fell into poverty that contributed to social instability. Rome’s political leaders disagreed fiercely about how, or even whether, to help their impoverished fellow citizens. The disagreements became so bitter that in the end they created a violent divide in the upper class, destroying any hope for preserving the Republic.

499: The Romans defeat their neighbors in Latium.

396: The Romans achieve final victory over the Etruscan town of Veii, doubling their territory through the conquest.

387: Invading Gauls (Celts) attack and sack Rome.

300: As many as 150,000 people now live in the city of Rome.

280–275: The Romans fight and defeat the mercenary general Pyrrhus commanding the forces of the Greek cities in south Italy.

264–241: The Romans defeat the Carthaginians in the First Punic War, with great losses on both sides.

Late third century: Livius Andronicus composes the first Roman literature in Latin, an adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey.

227: The Romans make provinces out of Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia, beginning their territorial empire.

220: After centuries of war, the Romans now control the entire Italian peninsula south of the Po River.

218–201: The Romans defeat the Carthaginians in the Second Punic War despite Hannibal’s invasion of Italy.

196: The Roman general Flamininus proclaims the freedom of the Greeks at Corinth.

149–146: The Romans defeat the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War, converting Carthage and its territory into a province.

146: The Roman general Mummius destroys Corinth; Greece and Macedonia are made into a Roman province.

133: Attalus III, King of Pergamum, leaves his kingdom to the Romans in his will.

Late 130s and late 120s: Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus as consuls stir up violent political conflict and are murdered by their opponents from the Senate.

Rome’s first wars were fought near its own borders, in central Italy. Soon after the establishment of the Republic, the Romans won a victory over their Latin neighbors in 499 B.C. They then spent the next hundred years fighting the Etruscan town of Veii situated a few miles north of the Tiber River. As a consequence of their eventual victory in 396 B.C., the Romans doubled their territory. The ancient sources present this first stage of expansion as a justified extension of Rome’s defensive perimeter rather than as the result of premeditated wars of conquest. However, these accounts were written in a much later period and may be offering a justification for early Rome’s expansion that created a historical precedent for what their authors thought should be the moral basis for Roman foreign policy in their own time.

Whatever the truth is about the Romans’ motives for fighting their neighbors in the fifth century B.C., by the fourth century B.C. the Roman army had surpassed all other Mediterranean-area forces as an effective weapon of war. The success of the Roman army stemmed from the organization of its fighting units, which was designed to provide tactical flexibility and maneuverability in the field. The largest unit was the legion, which by later in the Republic numbered five thousand infantry soldiers. Each legion was supplemented with three hundred cavalry troops and various engineers to do construction and other support duties. Roman legions were also customarily accompanied by significant numbers of allied troops, and sometimes even mercenaries, especially to serve as archers. The legion’s internal subdivision into many smaller units under experienced leaders, called centurions, gave it greater mobility to react swiftly to new situations in the heat of battle. Since the foot soldiers were drawn up in battle formation with space left between them, they could stand behind their large shields to make effective use of their throwing spears to disrupt the enemy line, and then move in with their swords drawn for hand-to-hand combat. Roman infantrymen’s swords were specially designed for cutting and thrusting from close range, and men underwent harsh training to be able to withstand the shock and fear that this emphasis on close combat generated not only in the enemy but also in the Roman troops who had to carry it out. Above all, Romans never stopped fighting. Even a devastating sack of Rome in 387 B.C. by marauding Gauls (a Celtic group) from the distant north failed to end the state’s military success in the long run. By around 220 B.C., the Romans had brought all of Italy south of the Po River under their control.

The conduct of these wars in Italy was often brutal. The Romans sometimes enslaved large numbers of the defeated. Even if they left their conquered enemies free, they forced them to give up large parcels of their land. Equally significant for evaluating Roman imperialism, however, is that the Romans also regularly extended peace terms to former enemies. To some defeated Italians they immediately gave Roman citizenship; to others they gave the protections of citizenship, though without the right to vote in Rome’s assemblies; still other communities received treaties of alliance and protection. No conquered Italian peoples had to pay taxes to Rome. They did, however, have to render military aid to the Romans in subsequent wars. These new allies then received a share of the booty, chiefly slaves and land, that Rome and its allied armies won on successful campaigns against a new crop of enemies. In other words, the Romans co-opted their former opponents by making them partners in the spoils of conquest, an arrangement that in turn enhanced Rome’s wealth and authority. All these arrangements corresponded to the Romans’ original policy of incorporating others into their community to make it larger and stronger. Roman imperialism, in short, was inclusive, not exclusive.

To increase the security of Italy, the Romans planted colonies of citizens and constructed a network of roads up and down the peninsula. These roads aided the gradual merging of the diverse cultures of Italy into a more unified whole dominated by Rome, in which Latin came to be the common language. But the Romans, too, were deeply influenced by the cross-cultural contacts that expansion brought. In southern Italy, the Romans found a second home, as it were, in long-established Greek cities such as Naples. These Greek communities, too weak to resist Roman armies, nevertheless introduced their conquerors to Greek traditions in art, music, theater, literature, and philosophy, thereby providing models for later Roman cultural developments. When in the late third century B.C. Roman authors began to write history for the first time, for example, they imitated Greek forms and aimed at Greek readers with their accounts of early Rome, even to the point of writing in Greek.

Rome’s urban population grew tremendously during the period of expansion in Italy. By around 300 B.C., as many as 150,000 people lived within the city’s fortification wall. Long aqueducts were built to bring fresh water to this growing population, and the plunder from the successful wars financed a massive building program inside the city. Outside the city, 750,000 free Roman citizens inhabited various parts of Italy on land taken from the local peoples. For reasons that are uncertain, this rural population encountered increasing economic difficulties over time, whether from a rise in the birth rate leading to an inability to support larger families, or from the difficulties of keeping a farm productive when many men were away on long military campaigns, or perhaps from some combination of these factors. It is clear that a large amount of conquered territory was declared public land, supposedly open to any Roman to use for grazing flocks. Many rich landowners, however, managed to secure control of huge parcels of this public land for their own, private use. This illegal monopolization of public land contributed to bitter feelings between rich and poor Romans.

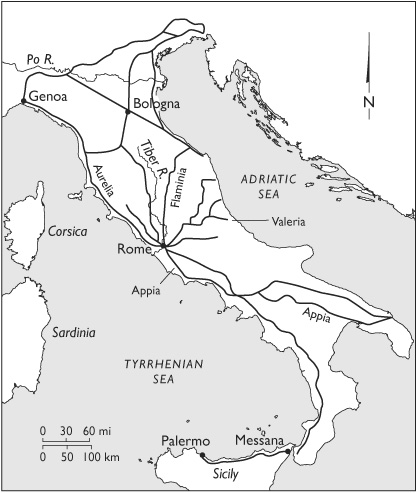

Map 4. Major Roman Roads under the Republic

The ranks of the rich by now included both patricians and plebeians; both these orders included “nobles.” In fact, the tensions of the Struggle of the Orders were so far in the past by the third century B.C. that the wealthy and politically successful patricians and plebeians saw their interests as similar rather than as conflicting and competing. Their agreement on issues of politics and state finance amounted to a new definition of the upper class, making the old division of the “orders” obsolete for all practical purposes. The members of the upper class derived their wealth mainly from agricultural land, as in the past, but now they could also increase their riches from plunder gained as officers in successful military expeditions against foreign enemies. The Roman state had no regular income or inheritance taxes, so financially prudent families could pass this wealth down from generation to generation.

After their military success in Italy, the most pressing issues for Romans continued to be decisions about war. When the mercenary general Pyrrhus brought an army equipped with war elephants from Greece to fight for the Greek city of Tarentum against Roman expansion in southern Italy, Rome’s leaders convinced the assemblies to vote to face this frightening threat. From 280 to 275 B.C. the Romans battled Pyrrhus in a seesaw struggle, until finally they forced him to abandon the war and return to Greece. With this hard-earned victory, Rome gained effective control of Italy in the south all the way to the shores of the Mediterranean at the end of the peninsula.

This expansion southward brought the Romans to the edge of the region dominated by Carthage, a prosperous state located across the Mediterranean Sea in western North Africa (today Tunisia). Phoenicians, Semitic explorers from the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, had colonized Carthage around 800 B.C. on a favorable location for conducting trade by sea and controlling fertile agricultural areas inland. The Carthaginians had expanded their commercial interests all over the western Mediterranean, including the large island of Sicily, located across a narrow strip of sea from the toe of the Italian peninsula. Their centuries of experience at sea meant that the Carthaginians completely outstripped the Romans in naval capability; the Romans in the third century B.C. had almost no knowledge of the technology needed to build warships or the organization required to field a powerful navy. The two states were alike politically, however, because Carthage, like Rome, was governed as a republic dominated by a social elite.

Since the Romans were no rivals for the Carthaginians in overseas trade and had never conducted a military campaign at sea or even on land outside of Italy, the two states could have gone on indefinitely without becoming enemies. As it happened, however, a seemingly insignificant episode created by third parties under the control of neither Rome nor Carthage drew these two powers into what became a century of destructive wars that changed the power structure of the Mediterranean world—the Punic Wars, so called from Punici (“Phoenicians”), the Roman name for the Carthaginians. In 264 B.C., a band of mercenaries in the city of Messana at Sicily’s northeastern tip close to Italy found themselves in great danger of their lives, after the military service for which they had been hired ended in failure. In desperation, the mercenaries appealed for help to Rome and Carthage simultaneously. There was no obvious reason for either to respond, except geography: Sicily was located precisely on the edge between the two powers’ spheres of control in the region. In short, Messana was perfectly positioned to become a flashpoint for conflict between Roman and Carthaginian ambitions and fears.

Figure 10. On a painted plate, a war elephant carries warriors in a tower on its back, followed by its calf. The Romans first faced these beasts on the battlefield in the third century B.C., but, like the Greeks, they learned to disrupt their attacks by placing spiked traps in their way to injure the behemoths’ soft feet. Scala/ArtResource, NY.

The Senate could not agree about what to do about the mercenaries’ request to be rescued, but a patrician consul, Appius Claudius Caudex, persuaded the people to vote to send an army to Sicily by promising them rich plunder. In this way, sending troops to Messana became Rome’s first military expedition outside Italy. When Carthage also sent soldiers to Messana, a battle erupted between the forces of the two competing powers. The result was the First Punic War, which lasted a generation (264 B.C.–241 B.C.). This decades-long conflict revealed why the Romans were so consistently successful in conquest: they were prepared to sacrifice as many lives, to spend as much money, and to keep fighting as long as necessary. Staying loyal to their traditional values, they never gave up, whatever the cost. The Romans and their allies persevered in the First Punic War despite losing 250,000 men and more than 500 warships from their newly built navy. The Greek historian Polybius, writing a century later, regarded the First Punic War as “the greatest war in history in its length, intensity, and scale of operations” (Histories 1.13.10–13).

The need to fight at sea against an experienced naval power spurred the Romans to develop a navy from scratch. They overcame their inferiority in naval warfare with an ingenious technical innovation, outfitting the prows of their newly built warships with a beam fitted with a long spike at its outer end. In battle, they snared enemy ships by dropping these spiked beams, called ravens because of their resemblance to the sharp-beaked bird, onto the enemy’s deck. Roman troops then boarded the enemy ship to fight hand-to-hand, their specialty. So successful were the Romans in learning and applying naval technology that they lost very few major battles at sea in the First Punic War. One famous loss in 249 B.C. they explained as divine punishment for the consul Claudius Pulcher’s sacrilege before the battle. To meet the religious requirement that a commander take the auspices before beginning battle, he had sacred chickens on board ship. Before sending his force into action, a commander had to see the birds feeding energetically as a sign of good fortune. When his chickens, probably seasick, refused to eat, Claudius hurled them overboard in a rage, sputtering, “Well, then, let them drink!” (Cicero, The Nature of the Gods 2.7). He began battle anyway and lost 93 of his 123 ships in a spectacular naval defeat. The Romans later punished him for his arrogant defiance of tradition.

The Romans’ victory in the First Punic War made them the masters of Sicily, whose ports and fields had brought prosperity to the island’s diverse settlements of Greeks, Carthaginians, and indigenous peoples. The income from taxes that the Romans received from Sicily proved so profitable that in 238 B.C. the Romans also seized the nearby islands of Sardinia and Corsica from the Carthaginians. In 227 B.C., the Romans officially converted Sicily into one overseas province and Sardinia and Corsica into a second. These actions created the Roman provincial system, in which Romans served as the governors of conquered territories (“provinces”) to oversee taxation, the administration of justice, and the protection of Roman interests. Unlike many of the peoples defeated and absorbed by Rome in Italy, the inhabitants of the new provinces did not become Roman citizens. They were designated “provincials,” who retained their local political organization but also paid direct taxes, which Roman citizens did not.

The number of praetors was increased to fill the need for Roman officials to serve as governors, whose duties were to keep the provinces paying taxes, free of rebels, and out of enemy hands. Whenever possible, Roman provincial administration made use of local administrative arrangements already in place. In Sicily, for instance, the Romans collected the same taxes that the earlier Greek states there had collected. Over time, the taxes paid by provincials provided income for subsidies to the Roman poor, as well as opportunities for personal enrichment to the upper-class Romans who served in high offices in the provincial administration of the Republic.

Following the First Punic War, the Romans made alliances with communities in eastern Spain to block Carthaginian power there. Despite a Roman pledge in 226 B.C. not to interfere south of the Ebro River, the region where Carthage dominated, the Carthaginians were alarmed by this move by their enemy. They feared for their important commercial interests in Spain’s mineral and agricultural resources. When Saguntum, a city located south of the river in the Carthaginian-dominated part of the Spanish peninsula, appealed to Rome for help against Carthage, the Senate responded favorably, ignoring their previous pledge. Worries about the injustice of breaking their word were perhaps offset by the Roman view that the Carthaginians were barbarians of lesser moral status. The Romans condemned the Carthaginians for what they (correctly) believed was the Punic practice of sacrificing infants and children in national emergencies to try to regain the favor of the gods.

When Saguntum fell to a Carthaginian siege, the Romans launched the Second Punic War (218 B.C.–201 B.C.). This second long war put even greater stress on Rome than the first because the innovative Carthaginian general Hannibal, hardened by years of warfare in Spain, shocked the Romans by marching a force of troops and elephants through the snow-covered passes in the Alps to invade Italy. The shock turned to terror when Hannibal killed more than thirty thousand Romans in a single day at the battle of Cannae in 216 B.C. The Carthaginian general’s strategy was to try to provoke widespread revolts in the Italian cities allied to Rome. His alliance with King Philip V of Macedonia in 215 B.C. forced the Romans to fight in Greece as well to protect their eastern flank, but they refused to crack under the pressure. Hannibal made their lives miserable by marching up and down Italy for fifteen more years, ravaging Roman territory and even threatening to capture the capital itself. The best the Romans could do militarily was to engage in stalling tactics, made famous by the general Fabius Maximus, called “the Delayer.” Disastrously for Hannibal, however, most of the Italians remained loyal to Rome. In the end Hannibal had to abandon his guerrilla campaign in Italy to rush back to North Africa with his army in 203 B.C., when the Romans, under their general Scipio, daringly launched an attack on Carthage itself.

Map 5. Roman Expansion During the Republic

Home at last after thirty-four years in the field in Spain and Italy, Hannibal was defeated at the battle of Zama in 202 B.C. by Scipio. He received the title Africanus to celebrate his outstanding victory over such a formidable enemy. The Romans imposed a punishing peace settlement on the Carthaginians, forcing them to scuttle their navy, pay huge war indemnities scheduled to last for fifty years, and relinquish their territories in Spain. The Romans subsequently had to fight a long series of wars with the indigenous Spanish peoples for control of the area, but the enormous profits to be made there, especially from Spain’s mineral resources, made the effort worthwhile. The revenues from Spain’s silver mines were so great that they financed expensive public building projects in Rome.

The Romans’ success against Carthage allowed them to continue efforts to defeat the Gauls in northern Italy, who inhabited the rich plain north of the Po River. Remembering the sack of Rome by marauding Gauls in 387, a success that not even Hannibal had achieved, the Romans feared another invasion. The Romans therefore believed their wars against these Celtic peoples were just because they were, in Roman eyes, a preemptive defense. By the end of the third century B.C., Rome controlled the Po valley and thus all of Italy up to the Alps.

Expansion eastward followed Rome’s military successes in the western Mediterranean. In the aftermath of the Second Punic War, the Senate in 200 B.C. advised that Roman forces should be sent abroad across the Adriatic Sea to attack Philip V, king of Macedonia in the Balkans. Philip’s alliance with Hannibal had forced the Romans to open a second front in that difficult war, but the Macedonians then made peace with Rome on favorable terms in 205 B.C., when the Romans had their hands full dealing with Carthage. Now, the senators responded to a call from the Greek states of Pergamum and Rhodes to prevent an alliance between the kingdom of Macedonia and that of the Seleucids, the family of a general of Alexander the Great who had founded a new monarchy in southwestern Asia in the tumultuous aftermath of Alexander’s conquests. These smaller powers feared they would be overcome, and the senators took the invitation to help these faraway places as a reason to extend Roman power into a new area. Their motives were probably mixed. Most likely they both wanted to punish Philip for his treachery and also demonstrate that Rome could protect itself from any threat to Italy from that direction.

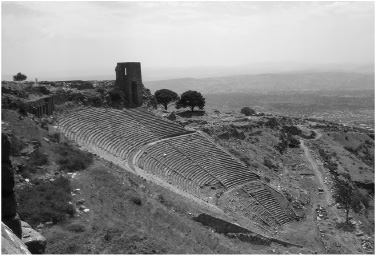

Figure 11. This Greek-style theater seated thousands of spectators in Pergamum, the capital of the Attalid kingdom in Asia Minor (today Turkey). Used for theatrical performances and festival shows, its size testifies to the popularity of large-scale entertainments in the Greco-Roman world. Erika Praefcke/Wikimedia Commons.

After defeating Philip, the Roman commander Flamininus in 196 B.C. traveled to a popular and well-attended international athletic festival near Corinth in southern Greece to proclaim the freedom of the Greeks. The locals were surprised and confused by this announcement. It certainly was not obvious to them why, or with what right, this foreigner was telling them that they were free. They assumed that freedom was their natural condition. Despite their puzzlement at the circumstances, the long-established cities and federal leagues of Greece certainly believed that the proclamation meant that they, the Greeks, were free to direct their own affairs just as they liked, so far as the Romans were concerned. After all, the Greeks thought, the Romans have now said we are their friends.

Unfortunately for them, the Greeks had misunderstood the message. The Romans meant that they had fulfilled the role of a patron by doing the Greeks the kindness of fighting a war on their behalf and then proclaiming their freedom, instead of asking for any kind of submission or even compensation for their losses in war. Therefore, in Roman eyes, their actions had made them the patrons of the liberated Greeks, who should then behave as respectful Roman clients, not as equals. The Greeks were their friends only in the special sense that patrons and clients were friends. They were politically and legally free, certainly, but that status did not liberate them from their moral obligation to behave as clients and therefore respect their patrons’ wishes.

Since the Greeks’ customs included nothing comparable, they failed to understand the seriousness of the obligations, and the differences in the kinds of obligations, between superiors and inferiors that Romans attributed to the patron-client relationship. As can happen in international diplomacy, trouble developed because the two sides failed to realize that common and familiar terms such as “freedom” and “friendship” could carry significantly different meanings and implications in different societies. The Greeks, taking the Roman proclamation of freedom literally and therefore thinking that they were free to manage their political affairs as they wished, resisted subsequent Roman efforts to intervene in the local disputes that continued to disrupt the peace in Greece and Macedonia after the proclamation of 196 B.C. The Romans, by contrast, regarded this refusal to follow their recommendations as a betrayal of the client’s duty to respect the patron’s wishes.

The Romans were especially upset by the military support that certain Greeks requested from King Antiochus III, the ruler of the Seleucid Kingdom, who invaded Greece after the Roman forces returned to Italy in 194 B.C. The Romans therefore fought against Antiochus and his allies from 192 to 188 B.C. in what is called the Syrian War. Again victorious, they parceled out Antiochus’s territories in Asia Minor (today Turkey) to friendly states in the region and once more withdrew to Italy. When the expansionist activities of the Macedonian king Perseus led King Eumenes of Pergamum to appeal to Rome to return to Greece to stop Macedonian aggression, the Romans responded by sending an army that defeated Perseus over the course of 171 to 168 B.C. Not even this victory settled matters in Greece, and it took yet another twenty years before Rome could decisively restore peace there for the benefit of its friends and supporters in Greece and Macedonia. Finally, after winning yet another Macedonian war in 148 B.C.–146 B.C., the Romans ended Greek freedom by beginning to bring Macedonia and Greece into the system of Rome’s provinces. In 146 B.C., the Roman commander Mummius destroyed the historic and wealthy city of Corinth as a calculated act of terror to show what continued resistance to Roman domination would mean for the other Greeks.

The year 146 B.C. also saw the annihilation of Carthage at the end of the Third Punic War (149 B.C.–146 B.C.). This war had begun when the Carthaginians, who had once again revived economically after paying the indemnities imposed by Rome following the Second Punic War, retaliated against their neighbor the Numidian king Masinissa, a Roman ally who had been aggressively provoking them for some time. Carthage finally fell before the blockade of Scipio Aemilianus, the adopted grandson of Scipio Africanus. The city was then destroyed and its territory converted into a Roman province. This disaster did not obliterate Punic social and cultural ways, however, and later under the Roman Empire this part of North Africa was distinguished for its economic and intellectual vitality, which emerged from a synthesis of Roman and Punic traditions.

The destruction of Carthage as an independent state corresponded to the wish of the famously plainspoken Roman senator Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder. For several years before 146 B.C., Cato had taken every opportunity in debates in the Senate to demand: “Carthage must be destroyed!” (Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder 27). Cato presumably had two reasons for his order. One was the fear that a newly strong Carthage would once again threaten Rome. Another was a desire to eliminate Carthage as a rival for the riches and glory that Cato and his fellow nobles hoped to accumulate as a result of the expansion of Roman power throughout the Mediterranean region.

The Romans won every war they fought in the first four hundred years of the Republic, although usually only after years of fierce battles, terrible losses of life, and enormous expense. These hard-won victories had both intended and unintended consequences for Rome and the values of Roman society. By 100 B.C., the Romans had intentionally established their control of an amount of territory more vast than any one nation had conquered since the time of the Persian Empire in the sixth century B.C. But as said at the start of this section, even experts disagree concerning to what extent the Romans originally intended to fight wars of conquest, as opposed to attacking enemies for self-defense in a hostile and aggressive world.

Roman expansion was never a constant or uniform process, and Roman imperialism under the Republic cannot be explained as the result of any single principle or motivation. The Romans exercised considerable flexibility in dealing with different peoples in different locations. In Italy, the Romans initially fought to protect themselves against neighbors they found threatening. In the western Mediterranean and western North Africa, the Romans followed their conquests by imposing direct rule and maintaining a permanent military presence. In Greece and Macedonia, they for a long time preferred to rule indirectly, through alliances and compliant local governments. Roman leaders befriended their counterparts in the social elite in Greece to promote their common interests in keeping the peace. Following the destruction of Carthage and Corinth in 146 B.C., Rome’s direct rule now extended across two-thirds the length of the Mediterranean, from Spain to Greece. And then in 133 B.C. the king of Pergamum, Attalus III, increased Roman power yet further with an astonishing gift: in his will he left his kingdom in Asia Minor as a bequest to the Romans. They were now the unrivaled masters of their world.

In sum, it seems fair to explain Roman imperialism as the combined result of (1) a concern for the security of Rome and its territory leading the Senate and the Assemblies to agree on preemptive strikes against those states perceived as enemies; (2) the desire of both the Roman upper class and of the Roman people in general to benefit financially from the rewards of wars of conquest, including booty, land in Italy, and tax revenue from provinces; and (3) the traditional drive to achieve glory, both among men of the upper class for personal gratification but also among Romans in general for the reputation of their state. Power was respected and honored in the world in which the Romans lived, and conquest was therefore not automatically regarded as a dirty word. At the same time, the Romans were always careful to insist—and sincere in believing—that they were not the aggressors but were fighting in defense of their safety or to preserve and enhance their honor. Whether we today should criticize them as more insincere or mistaken than modern imperialists is a question that readers must answer for themselves, while being careful to avoid the arrogance in judgment that modernity sometimes ignorantly assumes in comparing the contemporary world’s moral scorecard of good and evil to that of the ancient world.

The Romans’ military and diplomatic activity in southern Italy, Sicily, Greece, and Asia Minor intensified their contact with Greek culture, which deeply influenced the development of art, architecture, and literature in Roman culture. When Roman artists began creating paintings, they found inspiration in Greek art, whose models they adapted to their own taste and needs, and the same was true of sculpture. Painting was perhaps the most popular art, but very little has survived, except for frescoes (paintings on plaster) decorating the walls of buildings. Similarly, relatively few Roman statues are preserved from the period of the Republic. The first temple to be built of marble in Rome, erected in honor of Jupiter in 146 B.C., echoed the Greek tradition of using that shining stone for magnificent public architecture. A victorious general, Caecilius Metellus, paid for it to display his success and piety in the service of the Roman people. This temple became famous for starting a trend of expensive magnificence in the architecture and construction of Roman public buildings.

Roman literature also grew from Greek models. In fact, when the first Roman history was written about 200 B.C., it was written in Greek. The earliest literature written in Latin was a long poem, written sometime after the First Punic War (264 B.C.–241 B.C.), that was an adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey. The diversity that was driving Roman cultural development is shown by the fact this first author to write in Latin was not a Roman at all, but rather a Greek from Tarentum in southern Italy, Livius Andronicus. Taken captive and enslaved, he lived in Rome after being freed and taking his master’s name. Indeed, many of the most famous early Latin authors were not native Romans. They came from a wide geographic range: the poet Naevius (d. 201 B.C.) from Campania, south of Rome; the poet Ennius (d. 169 B.C.) from even farther south in Calabria; the comic playwright Plautus (d. 184 B.C.) from north of Rome, in Umbria; his fellow comedy writer Terence (190 B.C.–159 B.C.) from North Africa.

Early Roman literature therefore shows clearly that Roman culture found strength and vitality by combining the foreign and the familiar, just as the population had grown by bringing together Romans and immigrants. Plautus and Terence, for example, wrote their famous comedies in Latin for Roman audiences, but they adapted their plots from Greek comedies. They displayed their particular genius by keeping the settings of their comedies Greek, while creating unforgettable characters that were unmistakably Roman in their outlook and behavior. The comic figure of the braggart warrior, for one, mocked the pretensions of Romans who claimed elevated social status on the basis of the number of enemies they had slaughtered. These plays have proved enduring in their appeal. Shakespeare based The Comedy of Errors (A.D. c. 1594) on a comedy of Plautus; so, too, the hit Broadway musical and later film (A.D. 1966), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, took its inspiration from the bawdy humor of Plautus’s The Braggart Warrior.

Figure 12. An actor or author of the kind of Greek comedies that inspired Roman ones inspects the masks that comic actors wore on stage. The masks’ broad features helped spectators tell one character from another when viewing shows in giant theaters such as the one pictured in Figure 11. David C. Hill/Wikimedia Commons.

Not all Romans found Greek influence a good thing. Cato, although he studied Greek himself, repeatedly thundered against the corrupting effect that he believed the weakling Greeks were having on the sturdy Romans. He established Latin as a proper language for writing prose with the publication of his treatise on running a large farm, On Agriculture (published about 160 B.C.), and his history of Rome, The Origins (which he began writing in 168 B.C. and was still working on at his death in 149 B.C.). Cato glumly predicted that if the Romans became thoroughly infected with Greek literature, they would lose their power. In fact, early Latin literature reflected traditional Roman values despite its debt to Greek literature. Ennius, for example, was inspired by Greek epic poetry to compose his path-breaking epic, Annals, in Latin. Its subject, however, was a poetic version of Roman history from the beginnings to Ennius’s time. Its contents were anything but subversive of ancestral tradition, as a famous line demonstrates: “On the ways and the men of old rests the Roman commonwealth” (preserved in Augustine, City of God 2.21; Warm-ington vol. 1, pp. 174–175, frag. 467). This was Ennius’s poetic restatement of the traditional guide to proper conduct for Romans, the “way of the elders.”

The unanticipated social and economic changes brought about by Roman imperialism were far more destabilizing to Roman society than was Greek influence on literature. Rome’s upper class gained extraordinary financial rewards from Roman imperialism in the third and second centuries B.C. The increased need for commanders to lead military campaigns abroad meant more opportunities for successful men to enrich themselves from booty. By using their gains to finance public buildings, they could then enhance their social status by benefiting the general population. Building new temples, for instance, was thought to increase everyone’s security because the Romans believed their gods to be pleased by having more shrines in their honor. Moreover, some festivals associated with temples provided benefits to the general population because their animal sacrifices meant that meat could be distributed to people who could not afford it otherwise.

The creation of the provinces created a need for an increased number of military and political leaders that could not be provided by the traditional number of elected officials. More and more officials therefore had their powers prolonged to command armies and administer provinces. Because a provincial governor ruled by martial law, no one in the province could curb a greedy governor’s appetite for graft, extortion, and plunder. Not all Roman provincial officials were corrupt, of course, but some did use their unsupervised power to exploit the provincials to the maximum. Dishonest provincial officials only rarely faced punishment; the notorious Verres, prosecuted by Cicero in 70 B.C. for his crimes as an administrator in Sicily, was a rare exception. Enormous and luxurious country villas became a favorite symbol of wealth for men who had grown rich as provincial administrators. The new taste for a lavish lifestyle stirred up controversy because it contradicted Roman ideals, which emphasized moderation and frugality in one’s private life. Cato, for instance, made his ideal Roman the military hero Manius Curius (d. 270 B.C.), legendary for his simple meals of turnips boiled in his humble hut. The new opportunities for extravagance financed by the financial rewards of expansion abroad fatally undermined this tradition among the Roman elite of valuing a modest, even austere life.

The economic basis of the Republic remained farming. For hundreds of years, farmers working modest-sized plots in the Italian countryside had been the backbone of Roman agricultural production. These property owners also constituted the principal source of soldiers for the Roman army; only men who owned property could serve. As a result, the Republic encountered grave economic, social, and military difficulties when the successful wars of the third and second centuries B.C. turned out to be disastrous for many family farms throughout Italy.

Before the First Punic War, Roman warfare had followed the normal Mediterranean pattern of short military campaigns timed not to interfere with the fluctuating labor needs of agriculture. This seasonal warfare allowed men to remain at home during the times of the year when they needed to sow and harvest their crops and oversee mating and culling of their flocks of animals. The long campaigns of the First Punic War, prolonged year after year, disrupted this pattern by keeping soldiers away from their land for long periods. The women in farming families, like those in urban families, had previously worked in and around the house, not in the fields. A farmer absent on military campaigns therefore either had to rely on hired hands or slaves to raise his crops and animals, or have his wife try to take on what was traditionally man’s work. This heavy labor came on top of her already full day’s work of bringing water, weaving cloth, storing and preparing food, and caring for the family’s children and slaves. The load was crushing.

The story of the consul Marcus Atilius Regulus, who commanded a victorious Roman army in Africa in 256 B.C., reveals the severe problems a man’s absence could cause. When the man who was managing Regulus’s four-acre farm died while the consul was away fighting Carthage, a hired hand ran off with all the farm’s livestock and tools. Regulus therefore begged the Senate to send another general to replace him, so he could return home to prevent his wife and children from starving on his derelict farm. The senators provided support to save Regulus’s family and property from ruin because they wanted to keep Regulus as a commander on the battlefield (Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings 4.4.6). Ordinary rank-and-file soldiers could expect no such special aid. Women and children in the same sorry plight as Regulus’s family faced disaster because they had no marketable skills if they moved to a city in search of work. Even unskilled jobs were largely unavailable because slaves were used for domestic service, while manufacturing took place in small-scale businesses run by families through the labor of their own members. Many rural women, displaced from their farms and reduced to desperate poverty by their husbands’ absence or death in war, could earn money only by becoming prostitutes in the cities of Italy. The new pattern of warfare thus had the unintended consequence of disrupting the traditional forms of life of ordinary people in the Roman countryside, the base of Rome’s agricultural economy. At the same time, women in the propertied classes gained further wealth through dowry and inheritance, as the men in their families, who filled the elite positions in the army, brought home the greater share of booty to which their high rank entitled them under the Roman system of distributing the spoils of war.

The farmers’ troubles continued with Hannibal’s decade-long stay in Italy at the end of the third century B.C. during the Second Punic War. The constant presence of a Carthaginian army made it impossible for farmers to keep up a regular schedule of planting and harvesting in the regions that he terrorized, and the Roman general Fabius’s tactics of delay and attrition made their losses worse. Farm families’ troubles were compounded in the second century B.C. when many men had to spend year after year away from their fields while serving in Rome’s nearly constant military expeditions abroad. More than 50 percent of Roman adult males spent at least seven years in military service during this period, leaving their wives and children to cope as best they could for long periods. Many farm families fell into debt and had to sell their land. Rich landowners could then buy up these plots to create large estates. Landowners further increased their holdings by illegally occupying public land that Rome had originally confiscated from defeated peoples in Italy. In this way, the rich gained vast estates, called latifundia, worked by slaves as well as free laborers. The rich had a ready supply of slaves to work on their mega-farms because of the great numbers of captives taken in the same wars that had promoted the displacement of Italy’s small farmers.

Not all regions of Italy suffered as severely as others, and some impoverished farmers and their families in the badly affected areas managed to remain in their native countrysides by working as day laborers. Many displaced people, however, immigrated to Rome, where the men would look for work as menial laborers and women might hope for some piecework making cloth. It has recently been suggested that part of the reason that there were so many people on the move is that, for unknown reasons, there had been a surge in the birth rate that led to pockets of over-population in the countryside, with too many people to be supported by local resources. Whatever the reasons, the traditional stability of rural life had been terribly disrupted.

The influx of desperate people to Rome swelled the poverty-level population in the capital. The ongoing difficulty that these now landless urban poor experienced in supporting themselves from day to day in the closely packed city made them a potentially explosive element in Roman politics. They were willing to support with their votes any politician promising to address their needs. They had to be fed somehow if food riots in the city were to be averted. Like Athens before it in the fifth century B.C., Rome by the late second century B.C. needed to import grain to feed its swollen urban population. The Senate supervised the market in grain to prevent speculation in the provision of the basic food supply of Rome and to ensure wide distribution in times of shortage. Some of Rome’s leaders believed that the only possible solution to the problem of the starving poor was for the state to supply low-priced and, eventually, free grain to the masses at public expense. Others vehemently disagreed, though without an alternative solution to propose. So, distributions of subsidized food became standard government policy. Over time, the list of the poor entitled to these subsidies grew to tens and tens of thousands of people. Whether to continue this massive expenditure of state revenue became one of the most contentious issues in the politics of the late Republic.

The damaging effect of Roman expansion on poor farm families became an issue heightening the conflict for status that had always existed among Rome’s elite political leaders. The situation exploded into murderous violence in the careers of the brothers Tiberius Gracchus (d. 133 B.C.) and Gaius Gracchus (d. 121 B.C.). They came from one of Rome’s most distinguished upper-class families: their prominent mother Cornelia was the daughter of the famed general Scipio Africanus. Tiberius won election to the office of plebeian tribune in 133 B.C. He promptly outraged the Senate by having the Tribal Assembly of the Plebeians adopt reform laws designed to redistribute public land to landless Romans without the senators’ approval, a formally legal but highly nontraditional maneuver in Roman politics. Tiberius further outraged tradition by ignoring the will of the Senate on the question of financing this agrarian reform. Before the Senate could render an opinion on whether to accept the bequest of his kingdom made to Rome by the recently deceased Attalus III of Pergamum, Tiberius moved that the gift be used to equip the new farms that were supposed to be established on the redistributed land.

Tiberius’s reforms to help dispossessed farmers certainly had a political motive, as he had a score to settle with political rivals and expected to become popular with the people by serving as their champion. It would be overly cynical, however, to deny that he sympathized with his homeless fellow citizens. He famously said, “The wild beasts that roam over Italy have their dens.… But the men who fight and die for Italy enjoy nothing but the air and light; without house or home they wander about with their wives and children.… They fight and die to protect the wealth and luxury of others; they are styled masters of the world, and have not a clod of earth they can call their own” (Plutarch, Life of Tiberius Gracchus 9).

Just as unprecedented as his agrarian reforms was Tiberius’s persuasion of the Assembly to throw another tribune out of office: he had been vetoing Tiberius’s proposals for new laws. He then violated another longstanding prohibition of the “Roman constitution” when he announced his intention to stand for reelection as tribune for the following year; consecutive terms in office were regarded as “unconstitutional.” Even some of his supporters now abandoned him for disregarding the “way of the elders.”

What happened next signaled the beginning of the end for the political health of the Republic. An ex-consul named Scipio Nasica instigated a surprise attack on his cousin, Tiberius, by a group of senators and their clients. This upper-class mob clubbed Tiberius and some of his companions to death on the Capitoline Hill in late 133 B.C. In this bloody way began the sad history of violence and murder as a political tactic in the late Republic.

Gaius Gracchus, elected tribune in 123 B.C., and then again in 122 B.C. despite the traditional term limit, also initiated reforms that threatened the Roman elite. Gaius kept alive his brother’s agrarian reforms and introduced laws to assure grain to Rome’s citizens at subsidized prices. He also pushed through public works projects throughout Italy to provide employment for the poor and the foundation of colonies abroad to give citizens new opportunities for farming and trade. Most revolutionary of all were his proposals to give Roman citizenship to some Italians and to establish jury trials for senators accused of corruption as provincial governors. The citizenship proposal failed, but the creation of a new court system to prosecute senators became an intensely controversial issue because it threatened the power of the Senate to protect its own members and their families from punishment for their crimes.

The new juries were to be manned not by senators, but instead by members of the social class called equites, meaning “equestrians” or “knights.” These were wealthy men who mainly came from the landed upper class with family origins and connections outside Rome proper. In the earliest Republic, the equestrians had been what the word suggests—men rich enough to provide their own horses for cavalry service. By this time, however, they had become a kind of second level of the upper class tending to concentrate more on business than on politics. Equestrians with ambitions for political office were often blocked by the dominant members of the Senate. Senators drew a status distinction between themselves and equestrians by insisting that it was improper for a senator to dirty his hands with commerce. A law passed by the tribune Claudius in 218 B.C., for instance, made it illegal for senators and their sons to own large-capacity cargo ships. Despite their public condemnation of profit-seeking activities, senators often did involve themselves in business in private. They masked their income from commerce by secretly employing intermediaries or favored slaves to do the work while passing on the profits.

Gaius’s proposal to have equestrians serve on juries trying senators accused of extortion in the provinces marked the emergence of the equestrians as a political force in Roman politics. This threat to its power infuriated the Senate. Gaius then assembled a bodyguard to try to protect himself against the violence he feared from his senatorial enemies. The senators in 121 B.C. responded by issuing for the first time what is called an Ultimate Decree: a vote of the Senate advising the consuls to “take care that the Republic suffer no damage” (Julius Caesar, Civil War 1.5.7; Cicero, Oration Against Catiline 1.2). This extraordinary measure authorized the consul Opimius to use military force inside the city of Rome, where even officials possessing imperium traditionally had no such power. To escape arrest and execution, Gaius ordered one of his slaves to cut his throat for him.

The murder of Tiberius Gracchus and the forced suicide of Gaius Gracchus set in motion the final disintegration of the political solidarity of the Roman upper class. That both the brothers and their enemies came from that class revealed its inability to continue to govern through a consensus protecting its own unified interests as a group. From now on, members of the upper class increasingly saw themselves divided into either supporters of the populares, who sought political power by promoting the interests of the common people (populus), or as members of the optimates, the so-called “best people,” meaning the traditional upper class, especially the nobles. Some political leaders identified with one side or the other out of genuine allegiance to the policies that it proclaimed. Others simply found it convenient to promote their personal political careers by pretending to be sincere proponents of the interests of one side or the other. In any case, this division within the Roman upper class persisted as a source of political unrest and murderous violence in the late Republic.