The political fate of the Roman Empire altered forever in the fourth century A.D. First, Constantine shifted the center of imperial government and power from Italy to the eastern sector of the empire. Then, at the end of the fourth century A.D., the empire was split permanently into two geographic divisions, forming a western empire and an eastern empire. In the west, migrations of Germanic peoples subsequently transformed the region socially, culturally, and politically by replacing Roman provincial government with their own new kingdoms. These new inhabitants inside the empire’s borders lived side by side with Romans, the different groups keeping some of their traditions intact but merging other parts of their cultures. The growing strength of these new regimes in the western section of the empire and the consequent weakening of Roman authority there in the fifth century A.D. led many historians to refer to these events as the “Fall of the Roman Empire.”

More recently, however, scholars have reevaluated these developments as a political and social transformation that provided the deep background for important national divisions that came to characterize Europe in much later times. Largely avoiding the disruptions caused by the movements of the barbarians, the eastern empire had a different fate: ruling a traditionally diverse population speaking many different languages, it continued to exist for another thousand years as the self-identified descendant of ancient Rome, preserving the literature that would help preserve the traditions of classical antiquity and allow future generations to continue to learn from that past.

Late fourth century: The Roman Empire is divided into eastern and western sections, each ruled by a separate emperor; the Huns’ attacks terrorize central Europe.

376: The Visigoths beg the eastern emperor Valens for permission to enter the Roman Empire to escape the Huns.

378: The Visigoths defeat Emperor Valens at the battle of Adrianople (today in European Turkey).

404: Honorius, emperor in the west, makes Ravenna in Italy the western capital instead of Rome.

406: The Vandals break into the Roman Empire in Gaul (today France) and force their way to Spain.

410: The Visigoths under their commander Alaric capture and loot Rome.

418: The western empire allows the Visigoths to establish a kingdom in Gaul.

429: The Vandals seize Roman North Africa.

455: The Vandals attack and plunder Rome.

476: Romulus Augustulus, the last Roman emperor in the west, is deposed by the barbarian Odoacer.

527–565: Justinian rules as eastern Roman emperor and wages war against the Germanic kingdoms in western Europe to try to reunite the old empire.

529: Plato’s Academy in Athens closes after a thousand years.

532: Empress Theodora convinces Justinian not to run away during the Nika Riot in Constantinople.

538: Justinian opens the church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople.

540s: An epidemic kills a third of the population in Justinian’s empire.

Diocletian’s tetrarchy did not last, but the principle of dividing imperial rule persisted. Constantine had fought a long civil war at the beginning of his reign to seize unified rule for himself, and he abolished the tetrarchy because he feared disloyal “partners” outside his own family. By the end of his reign, however, he reluctantly conceded that the empire required more than one ruler. Therefore, he designated his three sons as joint successors, hoping that they could share power to preserve the stability that Diocletian’s reforms had achieved. A gory rivalry among the brothers ruined any chance of maintaining a unified empire. Their forces took up positions roughly splitting the empire on a north-south line along the western edge of the Balkan Peninsula and Greece. By the end of the fourth century A.D., the empire was finally formally divided in two sections, each with an emperor. On the surface these rulers cooperated, but in reality the empire’s western and eastern halves were now launched on separate histories.

The halves’ separateness was made clear by each having its own capital city. Constantinople (“City of Constantine”), located near the mouth of the Black Sea, became the capital of the eastern empire after Constantine in A.D. 324 “refounded” the ancient Greek city of Byzantium as “New Rome.” He chose the city for its military and commercial possibilities: it lay on an easily fortified peninsula astride principal routes for trade and troop movements. To recall the glory of Rome and thus claim the political legitimacy bestowed by the memory of the old capital, Constantine graced his refounded city with a forum, an imperial palace, a hippodrome for chariot races, and numerous statues of the traditional gods. The eastern emperors inherited Constantine’s “new” city as their seat.

Geography determined the site of the capital of the western empire, too. In A.D. 404, the emperor Honorius (ruled 395–423) made Ravenna, a port on Italy’s northeastern coast, the permanent western capital. Its walls and marshes protected it from attack by land, while its access to the sea kept it from being starved out in a siege. Ravenna’s new status led to great churches with dazzling multicolored mosaics being built there, but as a city it never rivaled Constantinople in size or splendor. Rome itself was now on a long decline that would eventually reduce it almost to the condition of the impoverished village in which the ancient home of the Romans had begun so many centuries before.

Fear as well as poverty motivated the migrations into the Roman Empire of northern “barbarians” (as they seemed to Romans because of their different language, clothing, and customs). Some historians decline to call these movements “migrations,” reserving that term to designate organized, large-scale movements of peoples who see themselves as ethnically united groups. The Germanic barbarians of the fourth century A.D. living beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire were certainly ethnically diverse and fluid in their political and social groupings, but nevertheless it seems reasonable to refer to the permanent transfer of these groups of people from one region to another as “migrations.” These peoples first migrated into Roman territory as refugees terrified into relocating by the relentless attacks of the Huns. Eager to improve their lives by sharing in the empire’s relative prosperity, they wanted to live in the comparative safety and comfort that they saw prevailing in the Roman provinces across the frontiers from their own lands. By the late fourth century A.D., however, the influx of barbarians had swollen to a near flood, at least in the eyes of the imperial administration.

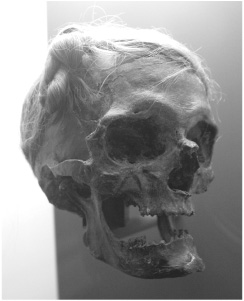

Figure 28. The skull of a Germanic barbarian preserves the topknot hairstyle that served as a marker of identity for his band. In ancient society just as today, how people dressed and kept their hair was as important as clothing in making a statement about their social status. Bullenwächter/Wikimedia Commons.

The Roman emperors unintentionally helped provoke the barbarian migrations into imperial territory by heavily recruiting northern warriors to fill out the reduced ranks of the Roman army in response to the third-century A.D. crisis. By the later fourth century, a large number of women and children joined these men in their migrations. They came not in carefully planned invasions but rather fleeing for their lives. Raids by the Huns had forced these Germanic people from their traditional homelands in what is now eastern Europe north of the Danube River. Bands of men, women, and children crossed the Roman frontier into the empire as hordes of squatters. Their prospects for survival were grim because they had no political or military unity, no clear plan of what to do, and not even a shared sense of identity. Loosely organized at best, the only possible tie they (or at least some of them) had in common was the Germanic origin of their diverse languages.

All these peoples felt terror at the coming of the Huns. These famously fierce warriors first appeared in history several centuries earlier as marauders raiding widely over central Asia. Scholars today are uncertain whether, as once thought, the later Huns were descended from the raiding groups called the Xiongnu that disturbed the frontiers of the Chinese Empire for many years before they were finally driven away westward (Sima Qian, Shiji 110). Wherever exactly the Huns may have originated, by the mid-fourth century A.D. they had arrived in the region of central Europe north of the Danube and east of the Rhine rivers. Moving deeper into the Hungarian plain by the 390s, they began raiding southward into the Balkans. The Huns excelled as nomadic warriors on horseback, launching cavalry attacks far and wide. Their skill as horsemen made them legendary. They could shoot their powerful bows while riding full tilt, and they could also stay mounted for days, sleeping atop their horses and carrying raw meat snacks between their thighs and the animals’ backs. Hunnic warriors’ appearance terrified their enemies: skulls elongated from having been bound between boards in infancy, faces grooved with decorative scars, and arms crawling with elaborate tattoos.

The eastern emperors paid the Huns large bribes to spare their territories. The nomads then decided to change their wandering way of life. They turned themselves into landlords, cooperating to create an empire outside of Roman territory north of the Danube. They subjected local farmers there and siphoned off their agricultural surplus. The Huns’ most ambitious leader, Attila (ruled A.D. 440–453), extended his domains from the Alps to the Caspian Sea. In A.D. 452, Attila led his forces all the way to the gates of Rome before Pope Leo I ransomed the city. At Attila’s death in A.D. 453, the Huns lost their fragile political cohesiveness and soon faded from history as a recognizable state. By this time, however, the damage had long been done: they had set in motion the barbarian migrations that transformed the Western Roman Empire.

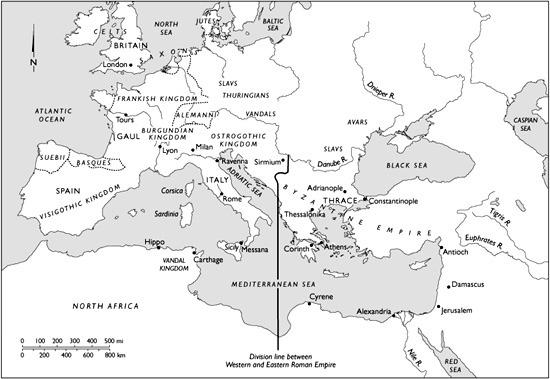

Map 12. Germanic Migrations and Invasions, Fourth and Fifth Centuries A.D.

The first Germanic barbarians to flee across the frontier into the Roman Empire came to be called the Visigoths (“West Goths”). Shredded by the Huns’ raids, in A.D. 376 they begged the eastern emperor, Valens (ruled A.D. 364–378), to allow them to migrate into the Balkans. The Visigoths received permission on condition that their warriors enlist in the Roman army to defend against the Huns. When greedy and incompetent Roman officers charged with helping the refugees instead exploited them for profit, the barbarians were reduced to starving. The officials even forced them to sell some of their own people into slavery in return for dogs to eat. Pushed beyond their limits of endurance, the Visigoths rebelled. In A.D. 378 they defeated and killed Valens at Adrianople (today in European Turkey). They killed two-thirds of the Roman force, including the emperor, whose body was never found among the giant mounds of corpses. Valens’s successor, the eastern emperor Theodosius I (ruled A.D. 379–395), then had to renegotiate the deal with the Visigoths. His concessions established the terms that other migrating bands would seek for themselves in the future: permission to settle permanently inside the empire, freedom to establish a kingdom under their own laws, large annual payments from the imperial treasury, and—so that the emperors could save face—a designation as “federates” (allies) pledged to help protect the empire.

Soon realizing they could not afford to pay the costs of this agreement, the eastern emperors decided to save themselves by forcing the newcomers westward. This became the eastern empire’s enduring strategy: push the barbarians into the western empire. The eastern emperors therefore cut off subsidies to the refugees and threatened full-scale war unless they moved on. The angry Visigoths complied, and neither the western empire nor the Visigoths would ever be the same. In A.D. 410, these barbarians stunned the world by capturing Rome itself. They terrorized the population. When the Visigoths’ commander Alaric demanded the city’s gold, silver, movable property, and foreign slaves, the Romans asked, “What will be left to us?” “Your lives,” the barbarian general replied (Zosimus, New History 5.40).

Too weak to defeat these invaders, the western imperial government in A.D. 418 reluctantly agreed to settle them in southwestern Gaul (present-day France), again saving the emperor’s pride by calling them federates. There, to adapt to their new circumstances, they did what no Germanic group had done before: organize a state. The Visigoths gradually transformed themselves from a loosely democratic and ethnically diverse tribal society of raiders and small farmers into an organized kingdom occupying former Roman territory but with its own sense of distinctive identity, written laws, and diverse economy. The political model they followed was the only one available, namely that of the government of the Roman Empire: monarchy emphasizing mutually beneficial relations with the social elite. The Visigoths financed their new state by taking over the tax revenue that Roman government had previously collected. They also forced landowners in Gaul to pay rent on their own property. Finding the new arrangements profitable, within a century the Visigoths had expanded into Spain.

Figure 29. Emperor Theodosius had himself depicted on this column among his fellow members of the elite being supplicated by cringing barbarians below. Like the cameo shown in figure 17, this monument expressed the emperor’s exalted status and the power over foreigners that he claimed for his fellow Romans. Marsyas/Wikimedia Commons.

Romans could be members of the Visigothic elite, though they had to show respect for their barbarian patrons. Sidonius Apollinaris, for example, a noble from the city of Lyon (A.D. 430–479), once purposely lost a backgammon game to the Visigothic king as a way of getting him to grant a favor. The Visigoths’ contact with Romans helped the barbarians develop a stronger sense of their own separate ethnic identity. As usual in assertions of identity, clothing and cosmetics promoted this goal: Visigoths wore pants and dressed their hair with aromatic dressings made from animal fat to differentiate themselves from Romans wearing tunics and using olive oil lotions.

The western empire’s concessions to the Visigoths emboldened other barbarian groups to use force in seizing Roman territory and create new identities for themselves. The most violent of these episodes began in A.D. 406 when the band known as the Vandals, who were also fleeing the Huns, crossed the Rhine River into Roman territory. This large group cut a swath through Gaul all the way to the Spanish coast. (The modern word vandal, meaning “destroyer of property,” perpetuates the memory of their destructiveness.) In A.D. 429, eighty thousand Vandals sailed to North Africa, where they captured the Roman province, breaking their agreement to remain federates. The Vandals caused tremendous hardship for local Africans by confiscating property, rather than allowing its original owners to pay regular rent and keep working their properties. They further weakened the western emperors by seizing North Africa’s tax payments in grain and vegetable oil to the central government. In A.D. 455 they destroyed the central symbol of the past glory of the western empire by plundering Rome. The Vandals also weakened the eastern empire when they manned a navy to disrupt Mediterranean trade, especially in food supplies.

Small groups took advantage of the disruption that the bigger bands caused to seize pieces of the crippled western empire. A significant small band for later European history was the Anglo-Saxons. Composed of Angles from what is now Denmark and Saxons from northwestern Germany, this group invaded Britain in the A.D. 440s after the Roman army had been recalled to defend Italy against the Visigoths. They established a kingdom in Britain by wresting territory away from the indigenous Celtic peoples and the remaining Roman inhabitants. Gradually, Anglo-Saxon culture replaced the local traditions of the island’s eastern regions. The Celts in this part of the island lost most of their language and Christianity, which survived only in Wales and Ireland.

When the Ostrogoths (“East Goths”) established a kingdom in Italy in the late fifth century A.D., this completed the process by which new Germanic regimes divided up the former western empire. The western emperors’ failure in leadership helped the Ostrogoths take over Italy. The emperors in the early fifth century A.D., like their predecessors, hired numerous Germanic army commanders to support the defense of the Roman heartland. By the middle of the fifth century, Germanic generals, taking advantage of struggles for power among the Romans competing to be emperor, became power brokers in deciding who would serve as emperor. Since they made the emperor, they could unmake him, too, reducing the western emperor to a puppet under their control. The last such unfortunate Roman on the throne of the western empire was a boy called Romulus Augustulus, whose name eerily recalled both Rome’s founder and its first emperor. In A.D. 476, after a dispute over pay, the Germanic commander Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus but, pitying his youth, gave him a pension to live in exile near Naples. Odoacer then appointed himself an independent king, formally ending the western empire’s five-century-long run of ethnic Roman emperors. The (Western) Roman Empire had therefore finally “fallen,” in the political sense. Nevertheless, Odoacer cultivated Rome’s still-existent Senate and consuls to show his love for tradition and hope for prestige. In the same spirit, he sent an embassy to Constantinople to acknowledge his respect for the eastern emperor and willingness to cooperate. Suspecting a sham, the eastern emperor hired the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great to suppress Odoacer. After murdering the usurper, Theodoric betrayed his employer by creating his own Germanic kingdom in Italy, directing his Ostrogothic regime from the by now traditional western capital at Ravenna until his death in A.D. 526.

Like Odoacer, Theodoric and his Ostrogothic nobles wanted to enjoy the luxurious life of the empire’s social elite, not destroy it. Although the eastern empire refused to accept Theodoric’s kingdom, he, like other Germanic rulers, nevertheless tried to appropriate the Roman past in support of his own rule. He wanted to preserve the empire’s prestigious traditions to give status to his new kingdom. The Senate and the office of consul therefore remained intact. Himself an Arian Christian, Theodoric followed Constantine’s example by following a policy of religious toleration, despite his strong disagreement with those of another religion, in this case Jews in the Italian city of Genoa: “I certainly grant you permission [to repair your synagogue], but, to my praise, I condemn the prayers of erring men. I cannot command your faith, for no one is forced to believe against his will” (Cassiodorus, Variae 2.27).

The replacement of western imperial government by barbarian kingdoms—which amounted to the political transformation of Europe—generated equally significant social and cultural transformations. The barbarian newcomers and the former Roman provincials created new ways of life based on a combination of their traditions. Some of the changes happened unexpectedly, but others were intentional. The Visigoth king Athaulf (ruled A.D. 410–415), for one, married a Roman noblewoman and explicitly stated his goal of integrating their diverse traditions:

At the start I wanted to erase the Romans’ name and turn their land into a Gothic empire, doing myself what Augustus had done. But I have learned that the Goths’ freewheeling wildness will never accept the rule of law, and that a state with no law is no state. Thus, I have more wisely chosen another path to glory: reviving the Roman name with Gothic vigor. I pray that future generations will remember me as the founder of a Roman restoration (Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans 7.43.4–6).

As the case of the Visigoths showed, the newcomers had to develop a more tightly structured society to be able to govern their new lands and subjects. The social and cultural traditions they originally brought with them from their homelands in northeastern Europe had ill prepared them for ruling others. There, they had lived in small settlements whose economies depended on farming tiny plots, herding, and iron working. They had no experience directing kingdoms. In their original society, lines of authority and identity were only loosely defined beyond those of the patriarchal household. Households were grouped into clans on kinship lines based on maternal as well as paternal descent. The members of a clan were supposed to keep peace among themselves; violence against a fellow clan member was the worst possible offense. Clans in turn grouped themselves into larger tribes, and then into yet larger but very loose and fluctuating multiethnic confederations, which non-Germans could also join. Different groups identified themselves primarily by their clothing, hairstyles, jewelry, weapons, religious cults, and oral stories.

Assemblies of free male warriors provided the barbarians’ only traditional form of political organization. Their leaders’ functions were restricted mostly to religious and military duties. Clans, tribes, and confederations often suffered internal conflicts and also frequently feuded violently with one another. Rejecting these organizational traditions, Germanic groups managed to create kingdoms with a hierarchical structure and a functioning administration because they followed Roman models in ordering their new regimes. In the end, however, none of these barbarian kingdoms ever rivaled the scope or services of earlier Roman provincial government in the Golden Age of the empire. The Germanic kingdoms remained much smaller and more local, and much territory in the former Roman provinces remained outside their control, or that of any other central authority.

Roman law was the most influential precedent for the Germanic kings in their efforts to construct stable societies. In their previous existence outside Roman territory, the barbarians had never developed written laws. Now that they had transformed themselves into monarchies ruling Romans as well as themselves, their rulers created legal codes for a system of justice to help keep order. The Visigothic kings developed the first written law code in Germanic history. Written in Latin and heavily influenced by Roman legal traditions, it made fines and compensation the primary method for resolving disputes.

A major step in developing barbarian law codes came when the Franks took over Gaul by overthrowing the Visigoths. Frankish warriors had been serving in the Roman army ever since the early fourth century A.D., when the imperial government had settled this group in a rough northern border area (now in the Netherlands). Their king Clovis (ruled A.D. 485–511) overthrew the Visigothic king in A.D. 507 with support from the eastern Roman emperor, who named Clovis an honorary consul. Clovis made his kingdom stable by following Roman models. He carefully fostered good relations with Gaul’s Roman elite and bishops to serve as the regime’s intermediaries with the population. He also emphasized written law. His code, published in Latin, promoted social order through clear penalties for specific crimes. In particular, he formalized a system of fines intended to defuse feuds and vendettas between individuals and clans.

The most prominent component of this system was Wergild, the payment a murderer had to make as compensation for his crime. Most of the money was paid to the victim’s kin, but the king received around one-third of the amount. The differing compensations imposed reveal the relative values of different categories of people in the kingdom of the Franks. The murder of a woman of childbearing age, a boy under twelve, or a man in the king’s inner circle brought a massive fine of 600 gold coins, enough to buy 600 cattle. A woman past childbearing age (specified as sixty years old), a young girl, or a freeborn man was valued at 200 coins. Ordinary slaves rated 35 coins.

Clovis’s new state, which historians call the Merovingian Kingdom in memory of Merovech, the legendary ancestor of the Franks, foreshadowed the kingdom that would emerge much later as the forerunner of modern France. The dynasty endured for another two hundred years, far longer than most other Germanic kingdoms in the west. The Merovingians survived so long because they created a workable combination of Germanic military might and Roman social and legal traditions.

The migrations that transformed the western empire politically and culturally also transformed its economy, but in ways that failed to strengthen it. The Vandals’ violent sweep severely damaged many towns in Gaul, and the urban communities there shriveled. Economic activity increasingly shifted to the countryside, becoming more isolated in the process. Wealthy Romans there built sprawling villas on extensive estates, staffed by tenants bound to the land like slaves. These estates aimed to operate as self-sufficient units by producing all they needed, defending themselves against raids, and keeping their distance from any authorities. Craving isolation, the owners shunned service in municipal office and tax collection, the public services by the social elite that had supplied the traditional lifeblood of Roman administration. When the last traces of Roman provincial administration disappeared, the new kingdoms never developed sufficiently to replace its internal structures of government and services fully.

The situation only grew rougher as the effects of these changes multiplied one another. The infrastructure of trade—roads and bridges—fell into disrepair with no public-spirited elite to pay to maintain them. Self-sufficient nobles holed up on their estates no longer had an interest in helping the central authority, Roman or Germanic, by paying or collecting taxes. They could take care of themselves and their fortress-like households because they could be astonishingly rich. The very wealthiest boasted an annual income rivaling that of an entire region in the old western empire. Naturally they faced great dangers, as they were obvious targets for raiders. Some failed, some survived for generations. It was to be another five hundred years, however, before western Europe would once again develop a civilization based on cities linked by trade. That fact alone reveals how significant the transformations were in that half of the Roman Empire.

The Eastern Roman Empire avoided the massive transformations that reshaped the western half. It continued to be economically sound and politically united for much longer than the west. Modern historians sometimes refer to the eastern empire as the Byzantine Empire, a term derived from the ancient name of its capital, Constantinople, but contemporaries never used that name. Shrewdly employing force, diplomacy, and bribery, the emperors in Constantinople deflected the Germanic migrations westward away from their territories and also blocked the aggression of the Sasanian kingdom in Persia to their east, employing the Gassanid Arabs as federates defending the vast areas from the Euphrates River to the Sinai Peninsula and protecting the east-west caravan routes of the Spice Road along which constant long-distance trade took place. In this way, the rulers of the eastern empire largely maintained their region’s ancient traditions and population. Beginning in the seventh century, its emperors lost great expanses of territory to the onslaught of Islamic armies, but they ruled in the eastern capital for eight hundred fifty years more.

The eastern emperors confidently saw themselves as the continuators of the original Roman Empire and the guardians of its culture against barbarian customs. Over time they increasingly spoke Greek as their first language, but they nevertheless continued to refer to themselves and their subjects explicitly as “Romans.” The sixth-century A.D. eastern empire enjoyed an economic vitality that had vanished in the west. Its social elite spent freely on luxury goods imported from East Asia on camel caravans and ocean-going ships: silk, precious stones, and prized spices such as pepper. The markets of its large cities, such as Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria, teemed with merchants from east and west. Soaring churches testified to its self-confidence in its devotion to God, its divine protector. As their predecessors had done in the earlier Roman Empire, the eastern emperors sponsored religious festivals and entertainments on a massive scale to rally public support for their rule. Rich and poor alike crowded city squares and filled amphitheaters to bursting on these spirited occasions. Chariot racing aroused the hottest passions. Constantinople’s residents, for instance, divided themselves into competitive factions called Blues and Greens after the racing colors of their favorite charioteers. It has even been thought that these high-energy fans fueled their disputes by mixing in religious disagreements with their sports rivalry, with Blues favoring orthodox Christian doctrines and Greens supporting Monophysite beliefs.

The eastern emperors ardently believed they had to maintain tradition to support the health and longevity of Roman civilization. They therefore did everything they could to preserve “Romanness,” fearing in particular that contact with Germanic peoples would “barbarize” their empire, just as it had the western empire. Like the western emperors, they hired many Germanic and Hunnic mercenaries, but they tried to keep these warriors’ customs from influencing the empire’s residents. Styles of dress figured prominently in this struggle to maintain ethnic identity. Therefore, imperial regulations banned the capital’s residents from wearing Germanic-style clothing (pants, heavy boots, and clothing made from animal furs) instead of traditional Roman garb (bare legs, sandals or light shoes, and robes).

Preserving any sort of unitary “Romanness” was in reality a hopeless quest because the eastern empire was thoroughly multilingual and multiethnic, as that part of the Mediterranean world had always been. Travelers in the eastern empire heard many different languages, observed many styles of dress, and encountered various ethnic groups. The everyday common language for this diverse region was Greek, but Latin continued to be used in government documents and military communication. Many Byzantine subjects retained their original local customs, but some also refashioned their ethnic identities. The Arabs of the Gassanid clan, for example, became fervent Monophysite Christians, drank wine at symposia like the ancient Greeks, and dressed their soldiers in Roman military style, while retaining their ancient customs of horse parades, feasts, and poetry recitals.

“Romanness” definitely included Christianity, but frequent and bitter controversies over doctrine continued to divide Christians and disrupt society. The emperors joined forces with church officials in trying to impose orthodoxy, with only limited success. In some cases, nonorthodox believers fled oppression by leaving the empire. Emperors preferred words to swords when possible in convincing heretics to return to orthodox theology and the hierarchy of the church, but they routinely applied violence when persuasion failed. They had to resort to such extreme measures, they believed, to save lost souls and preserve the empire’s religious purity and divine goodwill. The persecution of Christian subjects by Christian emperors symbolized the disturbing consequences that the drive for a unitary identity could cause.

Society in the eastern empire continued to exhibit the characteristic patriarchy of Romans in the west, with some additional traditions stemming from eastern Mediterranean ways. Most women minimized contact with men outside their households. Law barred them from fulfilling many public functions, such as witnessing wills. Subject to the authority of their fathers and husbands, women veiled their heads (though not their faces) to show modesty. Since Christian theologians generally went beyond Roman tradition in restricting sexuality and reproduction, divorce became more difficult, and remarriage was frowned on even for widows. Stiffer legal penalties for sexual offenses also became normal. Nevertheless, female prostitutes, usually poor women desperate for income, continued to abound in the streets and inns of eastern cities, just as in earlier days. They had to break the law or starve.

Women in the royal family were the exception to the rule: they could sometimes achieve a prominence unattainable for their poorer contemporaries. Theodora, wife of the emperor Justinian, dramatically showed the influence women could achieve in the ruling dynasty. Uninhibited by her humble origins (she was the daughter of a bear trainer and had been an actress with a scandalous reputation), she came to rival anyone in influence and wealth. A contemporary who knew her well judged her to be “superior in intelligence to anyone whatsoever of her contemporaries” (John the Lydian, On the Magistracies of the Roman Constitution 3.69).

Until her untimely death in A.D. 548, Theodora apparently had a hand in every aspect of her husband’s rule, from determining government policy to stiffening his courage at time of crisis. Her prominence and influence upset tradition-minded men, above all the imperial official and historian Procopius. He penned the controversial work today called The Secret History in part to accuse her of outrageous behavior, from promiscuity to sexual exhibitionism on stage as a paid performer; the truth of his claims is unrecoverable. Blaming her (in addition to Justinian) for what he saw as the cruelty and injustice of their reign, Procopius’s scorching account of alleged misdeeds and scandalous personal behavior by the government’s highest officials has provoked lively disputes about its accuracy that persist to this day.

The eastern empire’s government worsened social divisions between rich and poor because it provided services according to people’s wealth. Its complicated hierarchy required reams of paperwork and fees for countless aspects of daily life, from commercial permits to legal grievances. Getting something done required official permission; obtaining that permission required catching the ear of the right official. People with money and status found this process easy: they relied on their social connections to get a hearing and on their wealth to pay tips to move matters along quickly. Whether seeking preferential treatment or just spurring administrators to do what they were supposed to do, the rich could make the system work.

Those with limited funds, by contrast, found their poverty put them at a grave disadvantage because they had difficulty paying the generous tips that government officials routinely expected to motivate them to carry out their duties. Without tipping, nothing got done. Because interest rates were high, people could incur heavy debt trying to raise the cash to pay high officials to act on important matters. This system existed because it saved the emperors money to spend on their own projects. They could pay their civil servants pitifully low salaries because the public supplemented their incomes under this recognized system of extortion. The sixth-century administrator John the Lydian, for instance, reported that he earned thirty times his annual salary in payments from petitioners during his first year in office. To keep the system from destroying itself through unlimited greed, the emperors published an official list of the maximum tips that their employees could exact. Overall, however, this approach to government service generated hostility among poorer subjects and did nothing to encourage public support for the emperors’ ambitious plans in pursuit of conquest and glory.

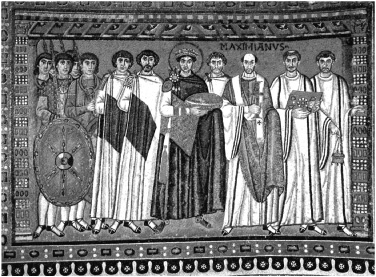

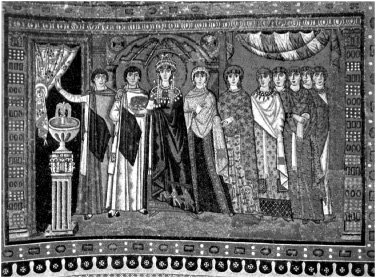

Figure 30. Brightly shining mosaics show Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora attended by their courts as they make offerings to God. Placed high on the walls of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, these images emphasized that the royal family was supremely rich and also supremely generous in worshiping God in thanks for his protection of the Romans. Wikimedia Commons.

The last emperor to try to resurrect the old empire was Justinian (c. 482–565), the most famous eastern emperor above all for the scholarly work he sponsored to organize and document Roman law and for the magnificent buildings that he had constructed in Constantinople. Born to a Latin-speaking family in a small Balkan town, he rose rapidly in imperial service until in A.D. 527 he succeeded his uncle as emperor. During his reign, Justinian launched military expeditions to try to suppress the west’s Germanic kingdoms and resurrect the old empire as it had been in the time of Augustus. His goal above all was to win fame by reversing the tide of history and recapturing former Roman territory in the west. Like Augustus, Justinian longed to “restore” Roman power and glory. He also hoped to recapture the Germanic kingdoms’ tax revenues and revive the seaborne shipments of food to the eastern empire that the Vandal navy had interrupted from its bases in North Africa. In the beginning he tried to make the reconquest happen with a smaller and cheaper force, but by the latter part of his reign he was financing a substantial military effort in the west. His commanders eventually recaptured Italy, the Dalmatian coast, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, part of southern Spain, and western North Africa from their barbarian occupiers. These victories indeed did temporarily reunite the majority of old imperial territory. (Most of Spain and Gaul remained under barbarian control.) Justinian’s territory stretched from the Atlantic Ocean eastward as far inland as the border of Mesopotamia.

Unfortunately, Justinian’s military victories turned out to be disastrous in the long run: they seriously damaged the western empire’s infrastructure and population, and their cost emptied the eastern empire’s treasury. Italy endured the most damage. The war there against the Goths spread death and destruction on a massive scale. The east suffered because Justinian squeezed even more taxes out of his already overburdened population to finance the western wars, and to bribe the Sasanians in Mesopotamia not to attack while his home defenses were depleted. The tax burden crippled the economy, leading to constant banditry in the countryside. Crowds poured into the capital from rural areas, seeking relief from poverty and robbers.

These stresses combined to provoke social violence. So heavy and so unpopular were the regime’s taxes and so notorious was the ruthlessness with which officials collected them that a major riot broke out in the capital in A.D. 532. The nine days of the Nika Riot (so called from the crowd’s shouts in Greek of “Win!”) saw constant street battles and looting that left much of Constantinople in ashes. The catastrophe panicked Justinian, who prepared to flee the city and abandon his rule. Just as he was about to leave, Theodora (according to Procopius) sternly rebuked him along these lines: “Once born, no one can escape dying, but for one who has held imperial power it would be unbearable to be a fugitive. May I never take off my imperial robes of purple, and not live to see the day when those who meet me will not address me as their master” (Procopius, History of the Wars 1.24.36). Shamed by his wife’s words, Justinian halted his flight and ordered troops into the streets. They ended the rampage by slaughtering thirty thousand rioters that they trapped in the racetrack.

Natural disaster compounded the Byzantine Empire’s troubles in this period. In the A.D. 540s, a horrific epidemic spread by flea bites killed a third of its people. A quarter of a million died in Constantinople alone, half the capital’s population. The loss of so many people created a shortage of army recruits, requiring the hiring of expensive mercenaries. It also left countless farms vacant, reducing the food supply and tax revenues. This combination of demographic and financial disaster greatly weakened the empire in the long run. Later Byzantine emperors lacked the resources to hold on to Justinian’s conquests, new Germanic kingdoms emerged in the west, and the old Roman Empire was divided for the last time.

The financial pressure on the population in Justinian’s reign contributed to social unrest. The emperor therefore imposed legal and religious reforms with the same aims as his polytheist and Christian predecessors on the imperial throne: to defend social order based on hierarchy and regain divine favor for himself and his subjects. The many problems threatening his regime made Justinian crave stability, and in response he increased the openly autocratic nature of his rule and emphasized his closeness to God. To promote the former goal, for example, he made senators kneel to kiss his shoe, and Theodora’s, when they came before the rulers. To promote the latter goal, he had imperial artists brilliantly recast the symbols of stable rule in a Christian context. A gleaming mosaic in his church at San Vitale in Ravenna, for instance, displayed a dramatic vision of the emperor’s role: Justinian standing at the center of the cosmos shoulder to shoulder with mosaics of the ancient Hebrew patriarch Abraham and Christ. Moreover, Justinian proclaimed the emperor the “living law,” reviving a philosophy of law that went back to the kingdoms of the region before the arrival of the Romans.

Justinian’s building program in the capital concretely communicated an image of his overpowering supremacy and religiosity. Most spectacular of all was his magnificent reconstruction of Constantine’s Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia). Facing the palace, the church’s location announced Justinian’s interlacing of imperial and Christian authority. Creating a new design for churches, his architects erected a huge building on a square plan capped by a dome 107 feet across and soaring 160 feet above the floor below. Its interior walls glowed like the sun from the light reflecting off their four acres of gold mosaics. Imported marble of every color added to the sparkling effect. According to later tradition, when Justinian first entered his masterpiece, dedicated in A.D. 538, he announced, “Glory to God, who thought me worthy to complete such a work. I have conquered you, Solomon!” (Anonymi Narratio de aedificatione Templi S. Sophiae 28). The emperor was claiming to have surpassed the splendor of the temple in Jerusalem built by that famous ancient king of the Hebrews. His building program became the most visible reminder to later ages of the glory that Justinian strove so hard to win.

The increased autocracy of the central government more and more concentrated attention on the capital to the detriment of the provinces. Most seriously, it reduced the autonomy of the empire’s cities. Their local councils ceased to govern. Imperial officials took over instead. Provincial elites still had to assure full payment of their areas’ taxes, but they lost the compensating reward of deciding local matters. Now the imperial government determined all aspects of decision-making and social status. Men of property from the provinces who aspired to power and prestige knew they could only satisfy their ambitions by joining the imperial administration at the center.

To further solidify his authority, Justinian had the laws of the empire codified to bring greater uniformity to the often-confusing jumble of legal decisions that earlier emperors had enacted over the centuries. A team of scholars condensed millions of words of regulations to produce the Digest. This collection of laws influenced European legal scholars for centuries. His experts also compiled a textbook for students, the Institutes, which continued to appear in law school reading lists until modern times. Justinian’s support for the production of these works of legal scholarship on both the principles and the statutes of law proved to be his most enduring legacy in western Europe.

Map 13. Peoples and Kingdoms in the Roman World, Early Sixth Century A.D.

To fulfill his sacred duty to secure the welfare of the empire, Justinian acted to guarantee its religious purity. Like the polytheist and Christian emperors before him, he believed his world could not flourish if the divine power protecting it became angered by the presence of religious offenders. As emperor, Justinian decided who the offenders were. Zealously enforcing laws against pagans, he compelled them to be baptized or forfeit their lands and official positions. Most energetically of all, he strictly purged Christians whom he could not reconcile to his version of orthodoxy. In further pursuit of purity, his laws made male homosexual relations illegal for the first time in Roman history and enforced the penalty of burning at the stake for those who did not repent and change their ways. Homosexual marriage, which may not have been unknown earlier, had been officially prohibited in A.D. 342, but civil sanctions had never before been imposed on men engaging in homosexual activity. All the previous emperors had simply taxed male prostitutes. The legal status of homosexual activity between women is less clear. It probably counted as adultery when married women were involved and was therefore a crime for that reason.

The use of legal sanctions and force against pagans, Christian heretics, and people convicted of homosexual relations expressed the emperor’s official devotion to God and his concern for his future reputation as a pious and successful ruler. This motivation had roots extending far back in ancient history, but one unintended effect was further to erode popular feelings of unity. Still, emperors after Justinian fought on to maintain what they saw as Rome’s mission to seek “empire without limit.” They simply lacked the resources to succeed. When in the seventh and eighth centuries A.D. another new faith, Islam, motivated armies to seek a similar goal, the Eastern Roman Empire began to lose territory to the attackers that it could in the end never recover.

As it turned out, the eastern empire’s most enduring contribution to the future did not come from its attempt to revive the old Roman Empire territorially. Instead, that contribution came from its preservation for much later times of the knowledge of literature from much earlier times, and of many of the physical texts on which continuing that knowledge depended. Whether intended or not, the effect of these actions was long-lasting.

The Christianization of the empire put the survival of classical Greek literature—from plays and histories to philosophical works and novels—at risk because this literature was pagan. The danger stemmed not as much from active censorship as from potential neglect. As Christians became authors, which they did copiously and with a passion, their works displaced the ancient texts of Greece and Rome as the most important literature of the age. Under these circumstances, one central reason encouraging the survival of classical texts was that elite Christian education and literature followed distinguished pagan models, Latin as well as Greek. In the eastern empire, the region’s original Greek culture remained the dominant influence, but Latin literature continued to be read because the administration was bilingual, with official documents and laws published in Rome’s ancient tongue (along with Greek translations). Emperor Constantius II, the son of Constantine, had decreed that any man seeking a job in the government had to be well educated in classical literature. This requirement for a comfortable position in the civil service induced families to have their sons study famous ancient pagan authors as early as possible in their education: in the village of Nessana in the Negev desert (today in Israel near the Egyptian border), archaeologists have unearthed a copy of a student’s Latin vocabulary list for Vergil’s Aeneid. It probably belonged to a local Arab boy who aimed at qualifying for a job in Roman government in the eastern empire.

Latin scholarship in the east received a boost when Justinian’s Italian wars impelled Latin-speaking scholars to flee for safety to Constantinople. Their work there helped to conserve many works that might otherwise have disappeared, because conditions in the west were hardly conducive to preserving ancient learning, except in such rare instances as that of Cassiodorus (A.D. 490–585). He supported monks in Italy in the task of copying manuscripts to keep their contents alive as old ones disinte-grated. His own book Institutions encapsulated the respect for tradition that kept classical learning alive: in prescribing the works a person of superior education should read, Cassiodorus’s guide included ancient secular texts, as well as scripture and Christian literature.

Much of the classical literature available today survived because it served as schoolwork for educated Christians. They received at least a rudimentary knowledge of some pre-Christian classics as a requirement for a good career in government service, the goal of every ambitious student. In the words of an imperial decree dating back to A.D. 360, “No person shall obtain a post of the first rank unless it shall be shown that he excels in long practice of liberal studies, and that he is so polished in literary matters that words flow from his pen faultlessly” (Theodosian Code 14.1). Another factor promoting the preservation of knowledge of classical literature was that the principles of classical rhetoric provided the guidelines for the most effective presentation of Christian theology. When Ambrose, a bishop of Milan in the later fourth century A.D., composed the first systematic description of Christian ethics for young priests, he consciously imitated the great classical orator Cicero. Theologians employed the dialogue form pioneered by Plato to refute heretical Christian doctrines, and pagan traditions of laudatory biography survived in the wildly popular field of saints’ lives. Similarly, Christian artists incorporated pagan traditions in communicating their beliefs and emotions in paintings, mosaics, and carved reliefs. A famous mosaic of Christ with a sunburst surrounding his head, for example, took its inspiration from pagan depictions of the radiant Sun as a god (see Figure 22, p. 153).

The explosion of Christian literature fostered a technological innovation whose effects also helped in the physical preservation of classical texts. Scribes had traditionally written books on sheets made of thin animal skin, or of paper made from papyrus reeds. They then glued the sheets together and attached rods at both ends to form scrolls. Readers faced a cumbersome task in unrolling them to read. For ease of use, Christians tended to follow a growing trend to produce their texts in the form of the codex—a book with bound pages. Eventually the codex became the standard form of book production in the Roman world. Because it was less susceptible to damage and could contain large texts more efficiently than scrolls, which were cumbersome for reading long works, the codex aided the preservation of literature. This technological innovation greatly increased the chances of survival of classical texts that were copied over into this more efficient form.

Despite the continuing importance of classical Greek and Latin texts for education and rhetorical training under the eastern empire, the survival of this knowledge from the past remained in danger in a war-torn world. Knowledge of Greek in the violence-plagued west faded so drastically that almost no one any longer had the knowledge to read the original versions of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey—for centuries and centuries the traditional foundations of a superior literary education. Classical Latin fared better, and scholars such as Augustine and Jerome knew ancient Latin literature extremely well. But they also saw the Greek and Latin classics of literature as potentially too seductive for a pious Christian. Jerome in fact once had a nightmare of being condemned on Judgment Day for having been a Ciceronian instead of a Christian.

The closing in A.D. 529 of the Academy originally founded in Athens by Plato a thousand years earlier vividly demonstrated the dangers for the survival of classical learning at this point. It is unclear whether Justinian was directly responsible for shutting down the Academy, which taught ideas from Neoplatonic philosophy that some Christians found intriguing and helpful. It is certain, however, that the emperor was outraged by the remarks of its virulently anti-Christian head, Damascius, and drove him into temporary exile in Persia. It could be dangerous to seem too connected to the pre-Christian past of the old Roman Empire.

As always, enforcement of imperial policy—though “policy” is perhaps too grand a characterization of what boiled down to the wishes of the emperor—was irregular in different regions of the empire. No action was taken against the Neoplatonist school at Alexandria. It perhaps mattered that the head of that institution of higher education, John Philoponus (“Lover of Work”), was a Christian. Nevertheless, ideas from the pagan past remained central to the school’s work: Philoponus wrote commentaries on the works of Aristotle as well as works on Christian theology. Some of Philoponus’s ideas on the concept of space and perspective anticipated those of Galileo a thousand years later. With his intellectual research, Philoponus achieved the kind of synthesis of old and new that was one of the fruitful possibilities in the ferment of the late Roman world: he was a Christian subject of the Roman Empire in Egypt in the sixth-century A.D., heading a school founded long before by pagans, studying the works of an ancient Greek philosopher as the inspiration for forward-looking scholarship. Philoponus’s example provides a fitting end to this overview of ancient Roman history because it makes clear the value—to say nothing of the personal satisfaction—that can be added in any time and place by learning from the knowledge encoded in the past of human experience.