15.3 Barriers to Entry

Apple, ExxonMobil, and Walmart have all been around for decades. Each has substantial market power, and each makes enormous profits. Yet the forces of entry and exit appear not to have pushed their economic profits to zero. What gives?

The ongoing profitability of these businesses reflects barriers to entry—obstacles that make it difficult for new businesses to enter the market—and these barriers have prevented new entrants from competing away their profits.

It’s not just that these companies got lucky. They got strategic. Each devotes a lot of resources to preventing new rivals from entering their respective markets. The lesson from their success is that you shouldn’t think of these barriers to entry as naturally occurring defenses. Rather, the barriers to entering your market are also shaped by the strategic choices that you’ll make as a manager.

In order to remain profitable in the long run, you need to focus on the threat posed by potential new entrants and find ways to outcompete and deter them.

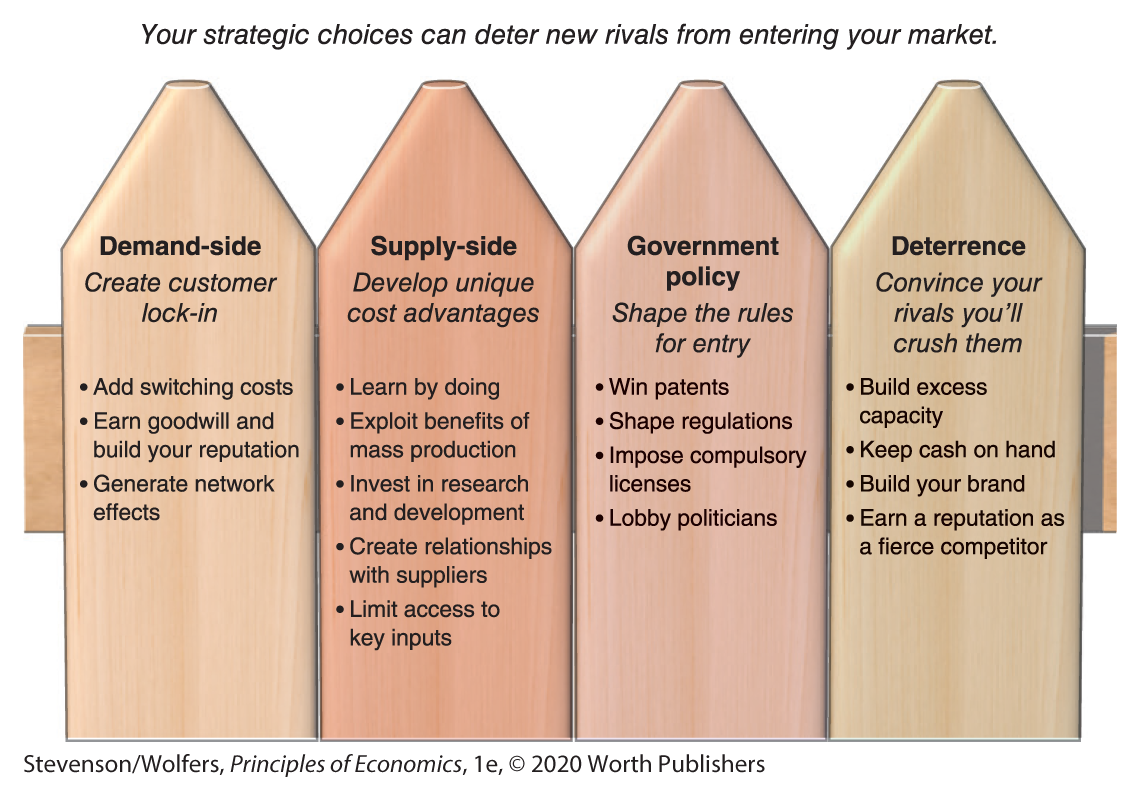

Different firms employ different strategies, but they all rely on four big ideas:

- Find ways to create customer lock-in (demand-side strategies).

- Develop unique cost advantages (supply-side strategies).

- Mobilize the government to prevent entry (regulatory strategies).

- Convince potential entrants you’ll crush them (deterrence strategies).

Let’s explore these strategies in greater detail.

Demand-Side Strategies: Create Customer Lock-In

One way to prevent new entrants from succeeding is to prevent them from winning over your existing customers. That’s why you want to create customer lock-in. Because customer-focused strategies shape the demand for your product (and that of your rivals), we refer to these ideas as demand-side strategies. Some key strategies include:

Switching costs lock your customers in.

Switching costs refer to any impediment that makes it difficult or costly for your customers to buy from another business instead. For instance, around three out of four iPhone owners who upgrade their phones stick with another iPhone. This isn’t just brand loyalty, it’s partly due to switching costs—if you switch to an Android phone, you’ll have to re-buy all of your favorite apps plus go through extra hassle transferring your data.

Savvy managers actively create switching costs to deter competitors. For instance, your bank probably gives you automatic bill-pay services. It’s not that your bank is trying to make your life easier, but rather it wants to lock you in. It knows that once you’ve set all your bills to autopay, you won’t want to do all that work again, and so you won’t switch to a competing bank. Similarly, when an airline gives you frequent flyer points, it makes it more rewarding to keep flying on that airline, effectively making it more costly to switch to a rival. And if you’ve ever tried to “cut the cable,” switching from your cable company to an online service like YouTube TV, you’ve probably experienced how cable companies try to make your switch as big of a hassle as they can. (You’ll have to return your cable box between 3 P.M. and 3:15 P.M. during a full moon at an office that’s miles away.)

In each of these cases, switching costs effectively lock in existing customers, making it harder for new entrants to succeed.

Reputation and goodwill keep your customers loyal.

The best reason to use this is because your friends do too.

A key reason that doctors, mechanics, plumbers, and electricians work to build a good reputation with their clients is that it helps lock in their customers. This goodwill gives incumbents a robust advantage over potential entrants who have yet to build those relationships.

Here’s the basic logic: Think about what you’ll do next time you’re sick. I bet you’re much more likely to visit the doctor who you’ve built a long-time relationship with, than to shop around to see if a new practice is offering a better deal. That loyalty makes it hard for a recent medical school graduate to successfully set up a rival practice.

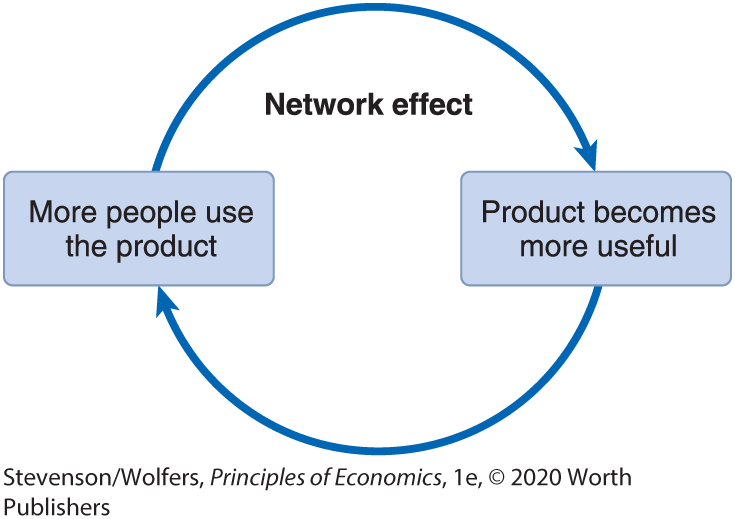

Network effects mean that your product becomes more useful the more people use it.

There are literally dozens of apps that allow you to communicate by text. But most have very few users, while WhatsApp is so popular that Facebook paid $19 billion to buy it (and many analysts think it’s worth billions more). Amazingly, it’s worth billions even though the technology just isn’t that complicated, and programmers could whip up an alternative—let’s call it WhatsUp—in just a few weeks. But a new entrant like WhatsUp couldn’t really compete, because what makes WhatsApp so useful is that your friends all use it. And so people keep using WhatsApp, because other people use it. The result is that it is virtually impossible for a new entrant like WhatsUp to beat the incumbent WhatsApp.

This is an example of a network effect, which occurs whenever a product becomes more useful when others also use it. Savvy managers work to create these network effects, because they make it harder for potential entrants to compete with them. For instance, when more people use Amazon’s website, it becomes more useful, because past customers write reviews that are helpful to future customers. As a result, Amazon is great for comparison shopping, and the millions of reviews on its site are an advantage that a new entrant can’t easily replicate.

Network effects aren’t just about high-tech products either. They’re critical to the ongoing success of the major car companies, like General Motors, Ford, and Toyota. Why? One reason to buy from a popular automaker is that millions of other people have done so too, and so there are thousands of repair shops with the spare parts in stock, and competent mechanics who can install them. By contrast, a new carmaker that lacks this network of repair shops will struggle to attract customers.

These network effects can be so powerful that they help even bad products succeed. Consider the Windows operating system, which millions of people have a love-hate relationship with. But even the haters keep using it, because there are so many useful programs available for it. Those programs are available because even programmers who despise Windows keep writing software for it, mainly because so many people use it. Despite all the complaints, no major competitor (except Apple) has entered the market, because no one will buy an operating system with few programs, and no one will write programs for an operating system that few people use.

Supply-Side Strategies: Develop Unique Cost Advantages

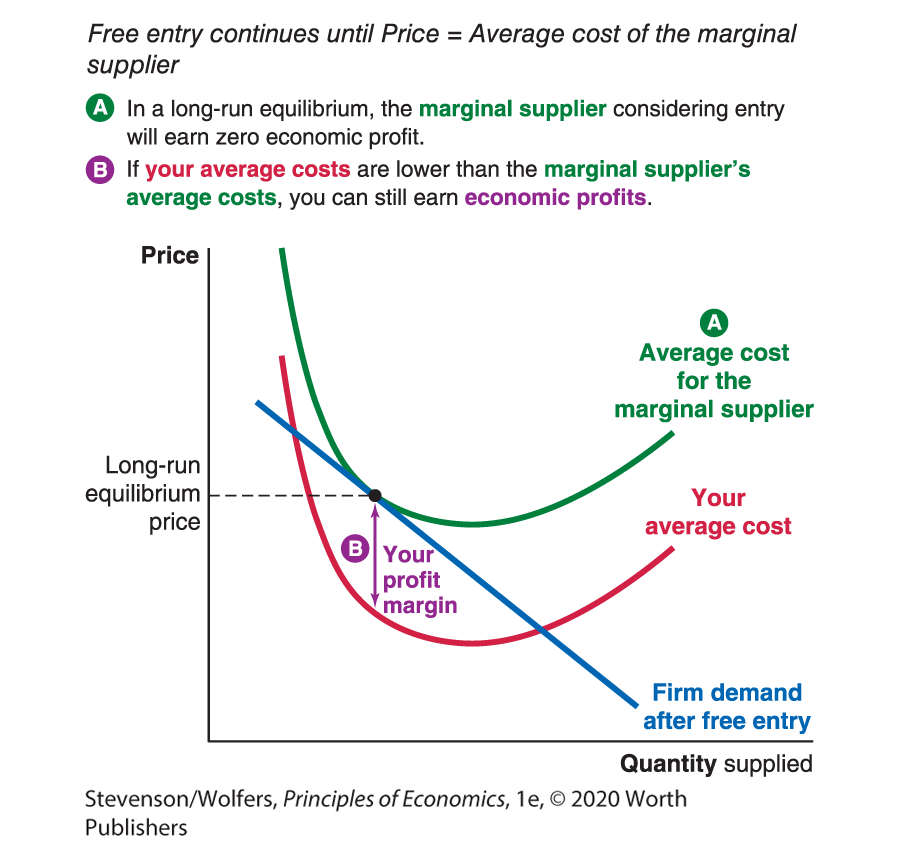

It’s also possible to deter the entry of new rivals by gaining cost advantages that newcomers cannot easily replicate. To see why, remember the key role that the marginal principle plays: New competitors will continue to enter a market until the last competitor that enters—the marginal supplier, which is the company that’s right on the cusp of entering or exiting—expects its economic profit to be zero.

But that doesn’t mean your economic profits will be zero. Figure 6 illustrates a long-run equilibrium, in which price is equal to the average cost of the marginal supplier, and so no more firms will enter. But if your firm has lower costs than that marginal supplier, then you’ll continue to earn economic profits, even if the marginal supplier is earning zero profit.

Figure 6 | Cost Advantages Generate Lasting Profits

Even better, if your cost advantages are large enough, they can effectively deter entry. After all, few entrepreneurs want to enter a market where they’ll have to compete with an incumbent with lower costs. Your lower costs signal that you’re more likely to survive a price war, as you can get by on a somewhat smaller profit margin for much longer than a rival can endure continuing losses.

Your long-run profitability depends on maintaining your cost advantage, and that’s only possible if your rivals can’t just copy the techniques that you’re using to lower your costs. This is why you must develop unique cost advantages that others can’t simply copy. Let’s dig into key strategies for developing unique cost advantages.

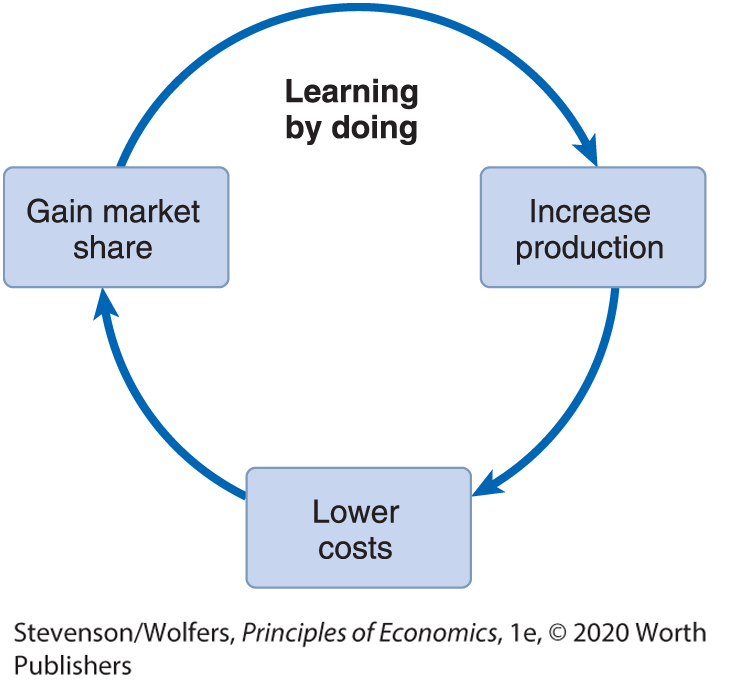

Learning by doing means that experience yields efficiency gains.

Many managers report that as they gain experience making a product, they learn how to streamline their operations, making them more efficient. Indeed, some consultants have estimated that every time a business doubles its accumulated production, it’ll learn enough to decrease its costs by around 20–30%. If you’re the incumbent, this process of learning by doing can yield a pretty robust advantage over newcomers whose inexperience means that they’re stuck with higher costs.

This insight also has strategic implications. It says to aggressively seek market leadership in order to gain a self-reinforcing advantage: If you’re the market leader, you produce the most, which gives you the most opportunities for learning by doing, which will lower your costs the most, further reinforcing your position as a market leader. And so it can be worth charging lower prices and forgoing profits in the short run, in order to set in chain this virtuous cycle.

The benefits of mass production can keep small firms from being competitive entrants.

Mass production can give you a competitive advantage.

Mass production is often more efficient than producing in small batches, although it often involves big fixed costs on machinery. These big upfront costs can make it difficult for new entrants to compete. In particular, if small businesses lack the funding to make these investments, they’ll operate at a substantial cost disadvantage relative to the large incumbent firms.

Take a quick look on Etsy, and you’ll see what I mean. You’ll discover an army of woodworkers who would love to devote their careers to making furniture. But building each individual table by hand is much less efficient than the giant production lines that churn out thousands of tables for Crate & Barrel. That’s why the hand-crafted furniture on Etsy is more costly to produce than the furniture at Crate & Barrel. And that cost disadvantage explains why these aspiring furniture makers aren’t really a serious threat to major furniture companies.

Research and development can create cost advantages.

Too often, executives think about research and development in terms of developing new products. But it can be at least as valuable to develop cheaper ways to make existing products, because it’ll give you a lasting cost advantage over potential entrants. In fact, much of the field of management science is about finding new ways of organizing the workplace to create cost savings. And there have been some stellar successes. Walmart, for instance, has developed an extraordinary logistics system, which means that it can stock its shelves more quickly, cheaply, and with less waste than its rivals. Toyota is famous for its innovative management practices, which means it can produce cars more cheaply than most of its potential competitors. And Amazon’s research into cloud computing means that it can manage its enormous website more effectively than rival e-tailers.

Relationships with suppliers can get you cheaper inputs.

Walmart can afford to sell at Everyday Low Prices because it has negotiated Everyday Even Lower Prices from its suppliers.

As you develop close relationships with your suppliers, you’ll become a valued business partner. As you grow, your business will become even more important to their success, making them invested in your success. You’ll be able to use your buying power to demand discounts on your raw materials, wholesale goods, and other inputs.

It’s a lesson that’s central to Walmart’s success, and it has used its relationships and buying power to great effect. Walmart is a huge player, and selling to Walmart can make or break even large suppliers. Walmart uses this leverage to negotiate ferociously. As a result, the wholesale prices that Walmart pays its suppliers are much lower than those available to any new entrant. In turn, that cost advantage makes Walmart a formidable competitor, and it has driven many rival stores out of business, and deterred countless others from ever entering.

Access to key inputs can freeze your competitors out.

If you’re a start-up founder, it’s going to be hard to compete with Facebook for top talent.

When U.S. Airways—which is now part of American Airlines—signed a 32-year lease on airport gates at Philadelphia International Airport, it not only provided long-term predictability for its business, it also effectively locked new airlines out of the market. It prevented budget airlines from entering the market, because they couldn’t get access to a gate, and so had no way to load and unload passengers.

The broader idea is that by tying up key inputs—often through long-term contracts—incumbents can make it difficult for new entrants to succeed. In some cases, these contracts run afoul of regulators. But in others, the effects are less direct. For instance, many Silicon Valley start-ups complain that their biggest problem is hiring software engineers, because most of the best ones are already working for the tech giants like Google or Facebook. By tying up key programming talent, the existing tech companies make it difficult for start-ups to compete.

Regulatory Strategy: Government Policy

The government can be a major force shaping whether new companies can enter your market. Sometimes the government regulates who can enter a market because it’s trying to counter some kind of market failure, and sometimes it does so in response to politicians being swayed by corporate lobbyists. Let’s explore some of these government-focused strategies.

Patents give you the right to be the only producer.

If you invent a new product, the government will grant you a patent, which means that no other company can use your idea without your permission. A patent effectively grants your company a monopoly. The government provides this right in order to provide an incentive for innovation.

This barrier to entry is the reason why Apple doesn’t worry about other companies making the iPhone. It’s why Merck doesn’t worry about other pharmaceutical companies selling their patented diabetes drug Januvia. And it’s why Toyota is not concerned that anyone else is trying to build a Prius. An alternative approach is to protect your invention by keeping it a secret, which is why Coke ensures that only a few senior executives know the recipe for Coca-Cola. And so even though some rivals make alternative colas, none can enter the market for the precise blend we know as Coca-Cola.

This patent describes Apple’s new invention.

Regulations make it difficult for new businesses to enter your market.

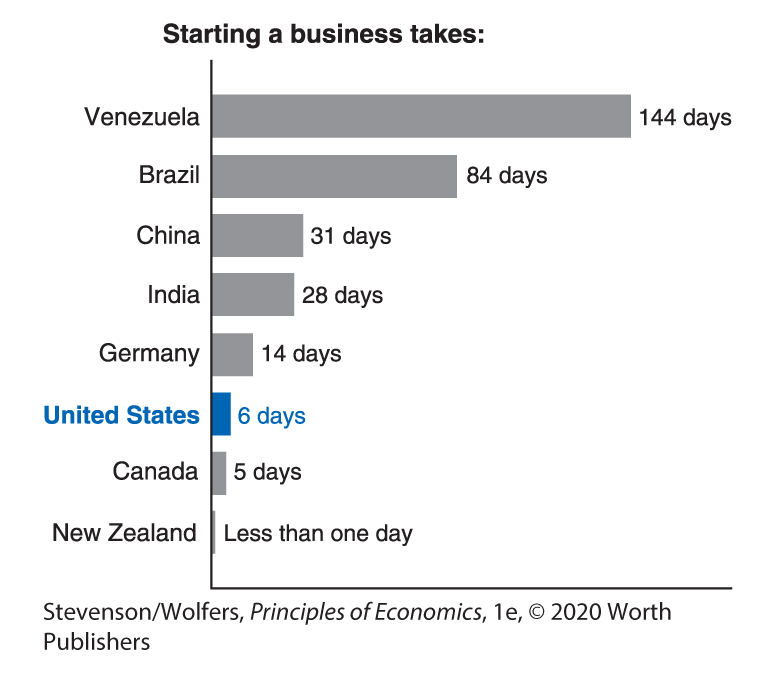

Data from: World Bank.

Government regulations can make it difficult to start a new business. For example, in some countries, it can take more than three months to step through the dozen or so separate procedures required to register a new business, and the associated fees can easily add up to more than a year’s income. In the United States, the barriers aren’t so high, as there are only half-a-dozen steps, and they can be completed within a week.

That said, there are some sectors of the U.S. economy that the government regulates closely—often for good reason. If you’re thinking about opening a child-care center, a hospital, a marijuana dispensary, or a charter school, you’ll quickly discover a regulatory burden that’s hefty enough to count as a substantial barrier to entry.

Compulsory licenses can limit competition.

The government directly regulates entry in some markets, and you’ll need a government-issued license to be allowed to do business. For instance, you can’t operate a radio or TV station without a license from the Federal Communications Commission. These licenses are both scarce and a hassle to obtain, which serves as a barrier to entry. While regulating the airwaves helps minimize static and interference, it also limits competition among radio stations. Sadly these barriers to entry are the reason there are so few stations playing interesting music.

Lobbying can create new regulatory barriers.

Many big businesses spend millions of dollars lobbying governments. Sometimes, they do this in ways that serve the common good—perhaps to persuade the government to fix outdated rules. But often it’s because they hope to convince the government to implement rules that will interfere with the plans of potential new entrants. You might be surprised to sometimes see incumbent firms arguing for more government regulations in their industry. It’s one of the oldest tricks in the lobbyist’s book. Look closer, and you’ll usually discover that these tighter regulations raise the costs on potential entrants by more than they raise the costs on incumbents. The incumbents are hoping that more intense regulation—while costly—will insulate them from competition.

Of course, business lobbyists never say it this way. They make their case by arguing that restricted entry or tighter regulation is somehow necessary to protect the public. And they’ll say this even though it prevents competition that would benefit the public by pushing prices down and providing options. But we know what really worries them: As new rivals enter their market, incumbents fear that their profitability will decline.

Politicians are often quite receptive to these arguments, because of an interesting political asymmetry. When a politician protects an incumbent business from competition, they’ll earn the gratitude of both the executives at that company, and the workers whose jobs they helped save. However, this comes at the cost of an unknown potential entrant that won’t enter the market and create new jobs. These costs are less politically salient, because no one holds those jobs yet, and so they don’t constitute an active lobby group.

Entry Deterrence Strategies: Convince Your Rivals You’ll Crush Them

Finally, entry deterrence strategies work by convincing potential rivals that if they do enter your market, you’ll respond so aggressively that they’ll wish they had never entered. Sure, your industry may be profitable now, but you want to convince potential entrants that if they enter, prices will fall by so much that they’ll never earn any profits themselves.

The challenge in pulling this off is that top managers will say that they’re planning to crush their rivals, whether it’s true or not. And because potential entrants understand this, they may not believe you. And so the goal of entry deterrence strategies is to make your threat credible—so that you can convince potential rivals that you really will destroy them if they decide to enter. That’s why the key to these effective deterrence strategies is to take concrete steps that commit your firm to compete aggressively. It’s the commitment to following through that makes your threats credible.

Let’s survey some specific strategies that savvy managers have used.

Build excess capacity so that your rivals expect fierce competition.

It’s worth considering building more production capacity than you actually need. This does three things. First, it makes it clear that you have the capacity to increase your production and cut prices if new rivals enter the market. Effectively you’re showing that you’ve invested in the infrastructure to start a price war, and win. Second, it’s especially useful to invest in excess capacity if it means incurring higher fixed costs today that will enable you to produce at a lower marginal cost in the future. Your lower marginal costs effectively commit your company to charging a low price if a new rival enters. As a result, your potential rivals should expect fierce competition if they do enter. And third, when this excess capacity takes the form of irreversible sunk costs, you’re effectively committing your company to stay in the market to fight potential rivals, because you can’t deploy those resources elsewhere. You’ve no choice but to compete, and compete vigorously, and any entrant should expect a bruising fight. For each these reasons, building excess capacity can convince potential rivals that entering your market is not going to end well for them.

Financial resources signal that you can survive a costly fight.

In mid-2018, Apple had an extraordinary $244 billion of cash on hand. That’s more cash than Microsoft, Google, and Amazon combined. Many financial analysts remain unsure why Apple doesn’t return the money to shareholders, invest it in new businesses, or do something more productive with it.

But business strategists see a reason: Apple’s mountain of cash is a signal to potential entrants. It’s a signal that Apple has the resources to survive a long and costly fight to maintain its market share. I don’t know about you, but if I were running a tech company, that mountain of cash would scare me. A well-stocked war chest can be a powerful signal to a potential entrant that perhaps they’re better off finding some other company to fight.

Brand proliferation can ensure there are no profitable niches for a rival to exploit.

Lots of choice, but few competitors.

Have you ever noticed that the breakfast cereal aisle at the supermarket is about a mile long, featuring dozens of varieties catering to just about every conceivable whim? It’s all about entry deterrence.

In reality, those dozens of different cereals are made by only a handful of companies. Their brand proliferation is a deliberate strategy to ensure that there’s almost no way for a new entrant to find a profitable niche. And it works—look closely next time you’re there, and you’ll see that new entrants haven’t really been able to break through.

Your reputation for fighting can be helpful, too.

When Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, learned about a new start-up called Diapers.com, he dispatched a senior vice president to have lunch with these new rivals, and to deliver the message that Amazon didn’t appreciate new competitors in the diaper market. Soon after, Amazon announced dramatic diaper discounts of up to 30%. The price war was on.

Executives at Diapers.com soon noticed that whenever they changed their prices, Amazon’s would immediately follow suit. Apparently Amazon set up its pricing bots to track Diapers.com’s prices, and then to undercut them. The discounts Amazon offered were so steep that it was estimated they would cost Amazon over $100 million over the next three months. These discounts were steep enough to stop Diapers.com in its tracks. As growth stalled at Diapers.com, its investors grew impatient at the prospect of further losses. Diapers.com eventually approached Amazon, asking for a buyout. Type “Diapers.com” into your browser, and it now redirects to Amazon.

Knowing this track record, would you be willing to follow in Diapers.com’s footsteps, and try to enter a market to compete against Amazon? If your answer is no, you’ve discovered the idea that underpins Amazon’s strategy: A company with a fierce enough reputation will scare potential competitors away. And that reputation is so valuable for Amazon that it’s worth fighting future battles to protect it. The price war with Diapers.com didn’t just destroy one rival, it deterred others from even trying.

Overcoming Barriers to Entry

At this point you’ve analyzed the four key types of barriers to entry summarized in Figure 7. Which tools you should use depends on the structure of your market, and the types of barriers that are easiest to impose. If you get your strategy right, you’ll be well placed to defy the odds and make consistently high profits.

Figure 7 | Barriers to Entry

So far, most of our analysis has focused on how managers of incumbent businesses create these entry barriers. But as an aspiring entrepreneur looking to break into a market, you’ll want to overcome these barriers to entry. The good news is that the understanding you’ve developed in this chapter will be just as useful as you develop strategies to break into new markets. Indeed, that’s a point that’s well illustrated by our final case study—the story of how one savvy entrepreneur overcame what appeared to be insurmountable barriers to entry in the automobile market.

Entrepreneurs need to overcome barriers to entry.

In recent years, electric car maker Tesla has become one of America’s most iconic brands, so much so that one analyst named the Tesla Model S the “Car of the Decade.” Before Tesla could become a household name, however, founder Elon Musk had to figure out how to break into the impenetrable automobile market. For years, industry analysts had thought that barriers to entry made it impossible for a start-up to compete with established automakers like Ford, Toyota, and Volkswagen. And so Elon Musk’s task then was not just to develop a new kind of electric car. It was also to combat the barriers to entry that had prevented others from even trying. Let’s see how he did it.

Demand-side strategies to combat customer lock-in.

One of the biggest hurdles Tesla faced in winning over car buyers was the network effects of traditional gasoline-powered vehicles. If you drive a gas-powered car, you probably take it for granted that there are thousands of gas stations where you can refuel. For Tesla’s potential customers, the absence of a similar network of places to recharge their cars would make owning an electric car a real headache. To overcome this lock-in, Tesla subsidized the installation of thousands of electric car chargers in parking lots, hotels, and restaurants.

But developing a nationwide network is a bigger problem than any individual company can solve, and so Musk invited other companies to use Tesla’s patented technology. That might sound odd, because this move made it easier for other electric car manufacturers to compete with Tesla. But Musk understood the value of building network effects. He figured that a thriving electric-car industry would lead to a vibrant network of charging stations and repair shops, and without this network, Tesla couldn’t succeed.

Supply-side strategies to overcoming cost disadvantages.

Previous generations of entrepreneurs had been intimidated by the cost advantages of incumbent automakers—particularly in research and development and manufacturing. But based on his experience in Silicon Valley, Musk realized he could spend a fraction of the research costs of major companies to bring Tesla’s cars to market. He did this by partnering with experienced British car manufacturer Lotus to reduce his up-front costs and by getting a low-volume luxury model (called the Roadster) to market quickly. Testing the waters with the roadster provided Tesla an opportunity for learning by doing, and the company was able to refine its technology and reduce its costs before trying to scale up with a less expensive model for the mass market.

Although Tesla only produced and sold 2,500 Roadsters in the company’s first four years, the company demonstrated that it could successfully build desirable electric cars. That early success convinced additional investors that Tesla was worth backing. Tesla used that infusion of funds to invest in research that created unique costs advantages, allowing it to produce lower-cost models that would eventually reach more customers.

Use regulatory strategies to your advantage.

Clean enough the government wants to subsidize it.

The automobile industry faces heavy safety and environmental regulations, and complying with these complicated rules could impose large up-front costs on new entrants. But Tesla saw the government’s concern with the environment as an opportunity. After all, electric cars are far kinder to the environment than gas-guzzlers. Tesla positioned itself to benefit from government policies to reduce emissions. It received a $465 million loan under an Energy Department program to boost fuel-efficient vehicles. Buyers of Tesla’s and other electric cars received federal subsidies of up to $7,500, plus some states chipped in further rebates of up to $5,000 as well as access to carpool lanes and cheaper electricity. Even though Tesla’s cars were expensive, these subsidies—and similar ones in foreign countries—made them more affordable. In recent years, Tesla has joined with other electric carmakers to lobby the government to continue these tax credits.

As a newcomer to the car market, Tesla held one more ace: It could decide where to locate its new factories, and it recognized that state governments would compete vigorously to become its new home. Before deciding where to build its battery factory, Musk negotiated with Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California, and finally settled on Nevada—but only after the state government offered $1.3 billion in tax breaks and other incentives.

Overcoming deterrence strategies to fight the big guys.

Ford, General Motors, and other leading automakers have huge war chests—often holding billions of dollars of cash on hand. Yet Musk did not let this stop him, even when he thought Tesla had a one-in-ten chance of succeeding. Admittedly, Musk had an advantage that not all entrepreneurs do: He had successfully founded and sold the online payment service Pay-Pal, so his deep pockets and strong connections to Silicon Valley investors provided Tesla with its own sizeable war chest to combat the established auto companies.

Look closely at Tesla’s story, and you can see that Elon Musk’s understanding of the economic ideas we’ve developed in this chapter—he majored in both physics and economics—helped him develop a successful strategy to overcome some pretty fearsome barriers to entry. The final chapter of this case study is yet to be written, as Tesla’s long-term success is not yet assured: Electric cars still represent only a tiny sliver of the market. But it has already made an impact. By 2018, Tesla was worth $62 billion, meaning that this brash upstart had risen to be worth more than either Ford or General Motors. Today, legacy automakers see themselves as playing catch-up in the electric car market, as they try to replicate the successes of innovative newcomer Tesla.