Tying It Together

You now know quite precisely what GDP is, how it’s measured, and how to interpret it. This is a vital skill, because GDP will be a consistent theme through the rest of your study of macroeconomics. That’s because GDP is a useful measure of material living standards, and a key goal of macroeconomics is to find ways for people to live better lives.

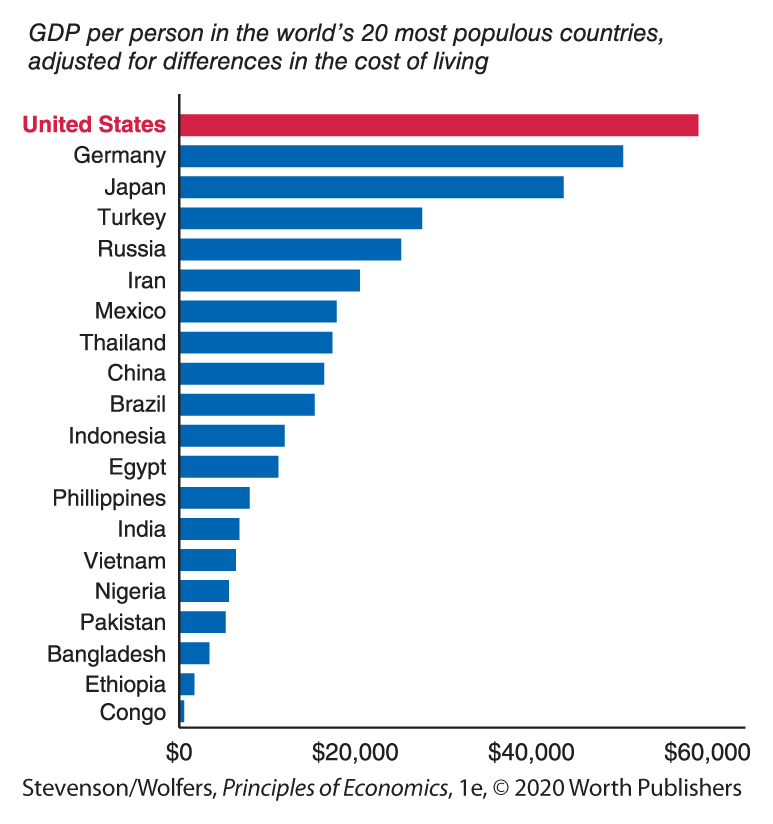

You can use GDP per person to assess differences in average income across countries. Figure 13 reveals some striking disparities. GDP per person is $62,600 in the United States compared to only $900 per person in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Much of the world’s population lives in India, where GDP per person is $7,800, or in China, where it’s $18,200. These differences in GDP per person have enormous implications for child mortality, life expectancy, and happiness. Finding a way to raise these countries’ GDP per capita to the level of the United States would have astounding consequences for human welfare. That’s why the next chapter analyzes the long-run determinants of economic growth, providing a framework that you can use to assess why GDP per person is so much lower in the Congo than in the United States, and the types of institutions and policies that can spur greater economic development.

Figure 13 | The United States Is One of the World’s Richest Countries

2018 Data from: World Bank.

The subsequent two chapters continue our tour of important macroeconomic indicators, focusing on unemployment and inflation. Unemployment and GDP are intricately linked because when people aren’t working they’re not producing, earning income, or spending much. Unemployment not only robs people of their purpose, it also leads the economy to produce less GDP than it potentially could. The subsequent chapter focuses on inflation, building upon what you’ve already learned about the distinction between real and nominal GDP. We’ll assess the extent to which higher rates of inflation can disrupt the economy, reducing GDP.

The subsequent set of chapters dig into the “microfoundations” of macroeconomics, analyzing the individual choices that add up to GDP. If you remember that

The next group of chapters focus on the year-to-year fluctuations in GDP and other economic indicators. These short-term fluctuations are called the business cycle, and they can be incredibly disruptive as output, unemployment, and inflation rise and fall. Over a series of several chapters, we’ll explore the role of spending, financial, and supply shocks in creating these fluctuations.

The last two chapters will turn to the macroeconomic policies that governments pursue both to boost GDP and to reduce its year-to-year fluctuations. The chapter on monetary policy explores how the Federal Reserve adjusts interest rates in order to influence economic activity, while the chapter on fiscal policy assesses how the government shapes the economy through its tax and spending decisions.

At the end of all this, you might think that economists are obsessed with GDP. We’re not. Economists and policy makers focus on GDP because it is a useful measure of material living standards. When you boost GDP, you boost the resources that a society has to pursue what’s important to its citizens and often that means that they are able to live richer, fuller, and happier lives. That’s what really matters.