31.1 Three Inflationary Forces

Let’s begin with a brief sketch of the road ahead. Our goal is to understand what drives inflation, and how it responds to economic conditions. That’ll require understanding the three causes of inflation. I’ll introduce those causes to you here, and then we’ll dig deeper into each of them in the following sections.

Inflationary Force One: Inflation Expectations

Before Outback Steakhouse prints its new menus, its executives have to decide whether to raise their prices for next year, and by how much. This is where inflation expectations—the rate at which average prices are anticipated to rise next year—become relevant. If Outback’s top managers expect inflation to be 2% next year, then they’ll probably follow suit and raise next year’s prices by 2% to keep up. After all, if average prices across the whole economy will rise by 2%, then it’s likely that the prices of their key inputs—beef, energy, and rent—will also rise by 2%. The only way for Outback to maintain its profit margin will be to raise prices in line with this rate of expected inflation.

When other managers across the economy make similar calculations they’ll make similar choices, each raising their prices in line with their inflation expectations. As a result, inflation expectations create inflation. We’ll return to this inflationary force in greater detail later in this chapter in the section called “Inflation Expectations.”

Inflationary Force Two: Demand-Pull Inflation

When business is good, it can take over an hour to get a table at some Outback Steakhouse locations, as the demand for Aussie “tucker” (that’s Aussie-speak for food) outstrips the restaurant’s capacity. In the long run, this will lead Outback’s managers to consider opening new restaurants. But in the short run Outback can’t increase its supply of meals, so its best bet is to raise its prices.

When there’s a line of people waiting, it’s time to raise your prices.

Now consider what happens when the whole economy booms, so that actual output exceeds potential output. Millions of businesses are in the same situation as Outback Steakhouse, with demand outstripping their productive capacity. Just as Outback raised its prices, so will they. These widespread price increases create demand-pull inflation, which arises when demand exceeds the economy’s productive capacity, pulling prices up. Alternatively, when demand falls short of productive capacity so that the output gap is negative, businesses are likely to moderate their price increases, leading to lower inflation. We’ll dig deeper into this link between the output gap and inflation when we introduce a framework for analyzing it called the Phillips curve.

Inflationary Force Three: Supply Shocks and Cost-Push Inflation

Turmoil in the Middle East drives oil prices—and lots of other prices.

The interdependence principle emphasizes the importance of linkages between markets, and it’s especially relevant to understanding how geopolitical tensions in the Middle East pushed up the price of Aussie tucker in the United States. Those tensions led to cutbacks in oil production, which pushed up oil prices, setting off a chain reaction. Initially, products made from oil—like gasoline, heating oil, and propane—become more expensive. These higher energy prices raised the production costs of many businesses, including Aussie-themed restaurants. It cost more to truck ingredients across the country; it was more expensive to heat a restaurant; and the energy costs required to run a commercial kitchen rose. Eventually, these higher marginal costs forced Outback Steakhouse to raise its prices.

A similar story played out across many sectors of the economy, as businesses discovered that higher oil prices led to higher prices for a range of oil-based inputs—including plastics, fertilizers, and rubber. Just as higher marginal costs led Outback Steakhouse to raise its prices, millions of other businesses raise their prices when their marginal costs rise. These widespread price increases create inflation. This is an example of cost-push inflation, which occurs when prices rise in response to an unexpected rise in production costs. The original catalyst of all this was a supply shock, which is why we’ll analyze cost-push inflation in more detail under the heading “Supply Shocks.”

Understanding Inflation

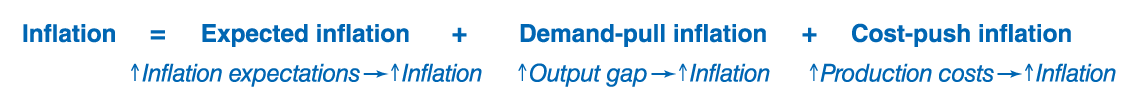

Put all the pieces together, and we’ve sketched out the three causes of inflation (and given you a preview of the chapter ahead): It’s the result of expected inflation, demand-pull inflation, and cost-push inflation:

Okay, that’s our brief sketch. We’ll spend the rest of this chapter digging into each of these inflationary forces in more detail. Let’s start with inflation expectations.