Selling the Wolf: The Massive Sales Campaign and Its Fallacies

By Ted B. Lyon

“Environmental battles are not between good guys and bad guys but between beliefs, and the real villain is ignorance.”

—Alston Chase1

Photo credit: Stayer/Shutterstock.com

The Wolf: From Bad Guy to Poster Child

In 1985, Yale sociologist Dr. Stephen Kellert conducted a national survey of public opinion about wildlife. He found that wolves were the least liked of all animals in North America. Fifty-five percent of the people said they were neutral toward wolves or disliked them.2 Since then, wolves have been reintroduced into the Northern Rockies, the Pacific Northwest, the Southwest, and the Southeast. The wolf populations in the Upper Midwest and New England have grown; wolf populations in Alaska and Canada have increased. Some wolf advocates have set a goal of wild wolves thriving in all fifty states. Similar programs are underway in Europe and Russia. The wolf has gone from bad guy to a poster child for conservation in less than thirty years.

The unprecedented wolf repopulation program brought sixty-six wolves from Canada to the Northern Rockies in 1995 and 1996 and has since sheltered them, allowing the population to skyrocket to at least ten times the number called for in the original plan. This could only have been accomplished with a massive, multi-faceted promotional sales campaign, for as you will learn, one introducing wolves into a modern social landscape is like “Jurassic Park”—the intentions may be honorable, but the results can be catastrophic.

The purpose of this book is two-fold: first, to expose the myths about wolves that have been sold to people in North America and abroad, falsehoods that have resulted in a war of words and seemingly endless courtroom battles, as well as a war in the woods; and, second, to set the record straight so people on all levels can understand the real issues about living with wolves in modern times, and make responsible decisions about the future of our uneasy relationship with Canis lupus, the gray wolf.

In Sun Zu’s masterful treatise on winning in conflict, The Art of War, he insists that to win you must understand your enemy. The sad truth is that the “Save the Wolf” campaign is largely based on romantic half-truths, exaggerations, and distortions, mixed with negative stereotyping, stigmatizing, and even intimidation of anyone who questions the wolf restoration program. But it has been extremely successful. So, let’s see how and why this is so.

A Brief History of Public Opinion aboutWolves in the United States

The ancestors of the modern gray wolf, the largest living member of the wild dog family Canidae, trace back to the Pleistocene era, perhaps as far back as 4.75 million years ago. The gray wolf was once the most widely distributed large mammal on Earth. Everywhere where wolves and people are found together, there is a history of respect, distrust, and mutual predation. This is a primary reason why wolves are not as common today as they once were.

When European settlers arrived in the United States, they found wolves, as their ancestors had known for thousands of years. Native Americans lived with wolves, which were integrated into their spirituality, mythology, and rituals, but Native Americans also trapped and killed wolves, using their skins for clothing and costumes. Eating them was considered a delicacy. While there were no newspapers or written records of wolves in those days, there are many tales of people being attacked, killed, and eaten by wolves. In the 1800s, as the buffalo were nearly exterminated by market hunters and a planned military strategy to drive Indians onto reservations, elk and deer were killed in large numbers by market hunters and the natural habitat declined dramatically due to logging and farming. In response to the lack of prey, wolves switched their predation to livestock. This triggered a war on wolves—bounties, trapping, hunting, and poisons—that was supported by the US government. This was the first wolf educational campaign—get rid of them—and Congress supported it.

In 1914, the US Congress passed legislation calling for the elimination of predators from all public lands, including National Parks, as wolves and other predators kept down the numbers of elk, deer, moose, and antelope, which were major attractions for tourists as well as game for hunters.3

Aided by modern weapons, traps, and poisons, by 1930 wolves were all but gone from the Lower 48, except for small numbers in the Northern Rockies and northern Minnesota, and a handful of Mexican wolves in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. Remaining wolves in Canada and Alaska became very wary of man, and were seldom seen, except in the far north. This was the second wolf educational campaign, again backed by the US Congress.

The use of poison baits (which were heavily used on coyotes after the wolves were nearly eliminated) was not banned until 1972, in large part due to Earth Day 1970, when banning the 1080 poison (sodium fluoroacetate) was a hot issue at teach-ins across the United States.

With an absence of wolves and diminished numbers of bears and mountain lions, as well as habitat conservation programs supported by many conservation groups, by the 1960s elk, deer, moose, and antelope numbers in Yellowstone National Park and elsewhere across the United States mushroomed to record high numbers. In some cases they exceeded the carrying capacity of the land. The wild game restoration campaign was spearheaded by conservation and sportsmen organizations with support from state and federal resource agencies. Increased hunting was considered to be the most popular way to control game animals.

The concept of restoring wolves to the lower forty-eight as a way to control big-game herds was first introduced to Congress in 1966 by biologists.4 Support for this strategy came from years of study of wolves on Mount McKinley in Alaska by Adolph Murie, and studies of wolves and moose on Isle Royale in Lake Superior by Purdue University wildlife biologist Durward Allen and his students, including David Mech and Rolf Peterson.5 This research concluded that wolves are shy creatures of the wilderness that do not attack people or seriously reduce large ungulate populations; and that wolves are nature’s sanitarians, attacking only the old, the lame, and diseased animals. That perspective became the gospel in wildlife management for decades. The problem is, as you will soon learn, wolves are very adaptable, and in other situations they behave very differently. The research kicked off another wave of wolf education, for the first time in favor of wolves.

The “harmless wolf” research was woven into the 1963 “Leopold Report,” otherwise known as “Wildlife Management in the National Parks,” written by Aldo Leopold’s son, Starker, a renowned wildlife biologist in his own right.6 The Leopold Report called for active management of wildlife to ensure that “a reasonable illusion of primitive America (what things looked like when white men first arrived there) . . . should be the objective of every national park and monument.”7

Following Earth Day 1970, support for restoring wolves began rising. “Wolfism” joined racism, sexism, ageism, and pollution as another form of oppression. Riding on the wave of the first Earth Day, the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973. One year later the gray wolf was added to the list of endangered species in the lower forty-eight states. Saving the wolf became a growing rallying cause for environmentalists, who were joined by animal rights groups, resulting in a “Save the Wolf” movement. But, as the Kellert study found, even by 1985, the general public was still not too keen on wolves. To bring back the wolf, an unprecedented massive public education program was needed to change the prevailing negative opinions of wolves.

With the only wolves found in zoos or remote areas, media became the new sense organs of urban Americans, as a swarm of books, articles, lecture tours, exhibits, public meetings, films, toys, and TV shows in support of wolf restoration exploded. “Wolf experts” were suddenly everywhere. The wolf became a symbol of green ecological action, along with stopping pollution, recycling, sustainability, and fighting global warming. Wolf restoration was also supported by animal rights groups: wolves not only were a species to restore, but a way to reduce big-game herds that supported hunting.

The new wild wolf emerged as a romantic mythic image of wilderness that urbanized Americans, clustered in concrete, steel, plastic, and wood canyons, longed for in their soul. Reviewing thirty-eight quantitative surveys conducted between 1972 and 2000, Williams, Ericsson, and Heberlein find that attitudes toward wolves consistently show that the farther one lives from wolves, the more likely public opinion is in favor of wolf restoration.8

Williams, Ericsson, and Heberlein also found, as did Kellert, that people who have the most first-hand contact with wild wolves—ranchers, farmers, outfitters, and hunters—held the most negative views of wolves, and despite the pro-wolf campaign, positive attitudes about wolf restoration have not continued to increase over time. In the United States, they found that 55.3 percent overall were favorable to wolf restoration. In Europe, where wolves have a history of contact with people, attitudes about wolves are less favorable—37 percent are favorable to wolves in Western Europe and 43 percent are favorable in Scandinavia.

While one result of the “Save the Wolf”” movement has been wolf restoration programs, a second consequence is growing antagonism between pro- and anti-wolf groups and advocates. Unfortunately, in the flood of wolf media, there has been very little accurate information about the problems associated with wolf restoration. Setting the record straight is a major goal of this book.

Owning the Truth about Wolves

There are at least four major problems with the “Save the Wolf” movement’s educational campaign. The first is that wolf behavior around people is heavily influenced by human behavior. Wolves are intelligent and adaptable, as well as unpredictable. In localities in Europe and Asia where people are commonly armed, as they are in North America, wolves are shy and reclusive. Where the populace is not heavily armed, wolves adapt, become habituated, and act much more boldly, preying on livestock, venturing into towns to attack pets and feed on garbage and attack people. The chapter by ethologist Dr. Valerius Geist shows a predictable behavior pattern of habituation that happens when wolves contact people and meet little or no opposition.

A second major problem is that the “Save the Wolf” campaign also has largely avoided reporting that in addition to rabies, wolves may carry over fifty diseases, some of which can be fatal to humans and livestock, such as hydatidosis. That we have little record of these diseases in the United States is simply due to the previous absence of wolves, and in some cases a lack of reporting of wolf-borne diseases. Warnings about such diseases are at best a footnote in the many “Save the Wolf” messages. It is bad for business. You will learn more about this in a later chapter.

A third major problem is that the economic benefits of a wolf restoration on a large scale are far outweighed by the costs, but the costs are not given anywhere near full coverage.

A fourth major problem is that the pro-wolf media has not only sold us a harmless wolf, but for the first time ever, it has sought to discredit as pure superstition the rich legacy of myths, fables, folklore, and fairy tales about wolves that originates from Europe and Asia. This campaign fails to understand how and why these tales came about, for they represent the earliest wolf educational campaign.

A fifth major problem is that wolves in the wild can and do interbreed with dogs and coyotes. This is already happening, especially in areas where wolf numbers are still small, and as it does the question of what is a “real wolf” to protect becomes more difficult. And, as canid hybridization increases, the behavior of these new hybrids will change.

Fairy Tales, Mythology, and Folklore about Wolves

Fables, folklore, and mythology of Europe and Asia were the first wolf educational campaign; most all teach that the wolf is dangerous. Far from being wrong, in Europe and Asia for thousands of years wolves have attacked and killed big game, livestock, pets, and people. From centuries of study in Europe and Asia, it’s known that wolves are adaptable and intelligent predators, both mysterious and unpredictable. Unlike most other predators, occasionally wolves run amok and engage in mass spree killings for sheer joy, such as the pack of wolves that killed 120 sheep on one August 2009 night in Dillon, Montana, or another pack that killed nineteen elk in March of 2016 in Wyoming, eating little or nothing. Put those qualities together with distinctive haunting vocalizations, and the possibility of a rabid wolf, you have an animal that in the right situations people should fear, and with good reason.

The Moral of the Story

After reviewing the history of man-wolf relations, in his award-winning book, Of Wolves and Men, Barry Holston Lopez arrives at the conclusion that: “No one—not biologists, not Eskimos, not backwoods hunters, not naturalist writers—knows why wolves do what they do.”9 That is a very good reason why folklore about wolves carries warnings. If an animal is unpredictable and carnivorous, you have a suspicious demon. This is why a terrorist acting alone is often called “a lone wolf.”

It’s understandable then that in cultures where a significant number of people do not own firearms, and where children may venture into areas where wolves are present, fairy tales and folklore such as Aesop’s fables, “Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Three Little Pigs,” Shakespeare, Grimm’s fairy tales, as well as holy books including the Bible, the Rig-Veda, and the like cast Canis lupus in a negative light. These stories are warnings, especially to children and shepherds, to keep people alive.

We know the wolf on a subconscious level, too, as it may visit us in our dreams. From a psychological standpoint, animals that appear in our dreams are symbols of instincts in the unconscious roots of the psyche—in other words, archetypes. The wolf is an archetypal symbol of pure wildness, both in nature and human nature; and a reminder of one’s own inner wolf-like qualities—positive in terms of being a skillful hunter and a family protector, and the wolf’s dark shadow side of lust, violence, greed, killing, unpredictability, etc.—that can make a wolf seem like a sociopath. The reality is that wolves are unpredictable, which is why stories of the danger of wolves were created in the first place.

Wolves reproduce rapidly; little wonder that the wolf is a symbol associated with lust. The call of the rogue male out on the prowl for chicks is the “wolf whistle.” This is why calling a person a “wolf” means they are not trustworthy and can be dangerous.

The universal belief in half-human and half-wolf creatures—the werewolf—and the rare mental disease of lycanthropy, where a person goes berserk with almost superhuman strength, howling, making wolf-like sounds, and may attack people as if they are prey, all speak of our fear of raw human instinctual emotions that make people behave like wolves.10 Among the Navajo, the word mai-coh means both wolf and witch, which the Navajo see as a werewolf, a person who is most likely to perform evil acts during twilight or at night while wearing a wolf skin.

Referring to the Wolf

The meanings of “wolf” are many. In medieval times, famine was called “a wolf.” Werewolves were a principal target of the Inquisition. In Dante’s Inferno, the wolf presides over the eighth circle of hell where punishment is meted out to those who have committed the “sins of the wolf” in their lives—religious and political hypocrites, magicians, thieves, and seducers. In the fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood” the wolf uses trickery to try to lure a young girl into his clutches. Ostensibly he is going to eat her, but implicit sexual connotations are also obvious.

In the myth and magic of earlier times, wolves have a strong association with the supernatural. Wolves prowl at night and twilight, a time for the imagination to grow larger. Latin for “dawn” is interlupum et canum, which translates as “the time between the wolf and the dog.”

There are thirteen references to wolves in the Bible, almost all as metaphors for destructiveness and greed. It should not be surprising then that the Book of Beasts, a medieval bestiary derived from a chain of Christian monks adapting earlier natural histories that date to Pliny and Aristotle, states: “The devil bears the similitude of a wolf: he who is always looking over the human race with his evil eye, and darkly prowling round the sheepfolds of the faithful so that he may afflict and ruin their souls. . . . Because a wolf is never able to turn its neck backward, except with movement of the whole body, it means that the Devil never turns back to lay hold on repentance.”11

In his early days, Adolph Hitler referred to himself as “Herr Wolf” and referred to his sister as “Frau Wolf.” The name “Adolf” itself is a derivative of “Athalwolf,” meaning “Nobel Wolf.” He called his retreat in Prussia “The Wolf’s Lair,” and he named three of his military headquarters Wolfsschanze, Wolfsschlucht, and Werwolf. His favorite dogs were wolfshunde, and he referred to his SS as “my pack of wolves.” Little wonder then that journalists spoke of groups of German submarines patrolling the North Atlantic as “wolf packs.”

There are exceptions to the negative wolf mythology, as in Roman mythology when a she-wolf, or Lupa, raises Romulus and Remus after their mother, Rhea Silvia, was forced to abandon the twins.

In Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, the boy Mowgli is adopted by wolves, and there have been a few cases where something like this may have happened in India. Japanese farmers once left offerings to the wolf kami (spirit) to ask his help in protecting their fields from deer and wild pigs. However, the two species of wolves that once inhabited Japan have been extinct for over a century. The Honshu wolf (Canis lupus hodophilax) is said to have become extinct in 1905 due to an epidemic of rabies. The Ezo wolf (Canis lupus hattai) of the island of Hokkaido, died out in the Meiji period (1868–1912) when, with the establishment of American-style horse and cattle ranches in the area, wolves came to be viewed as a serious threat to the livestock and strychnine-poisoned bait was used to reduce wolf numbers. By 1889 the Hokkaido wolf had disappeared.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that in Asia wolves attack and kill children far more often than they adopt them, and in European history there are many cases of fatal wolf attacks. This is why myths, folklore, and fairy tales almost always portray wolves in a negative light abroad.

Many Native American tribes respect the wolf’s prowess as a mighty hunter, and they too have many legends, rituals, and myths about wolves, but Native Americans and Inuits still kill wolves for their fur, for food, and in self-defense. Author Barry Lopez writes: “It is popularly believed that there is no written record of a healthy wolf ever having killed a person in North America. Those making the claim ignore Eskimos and Indians who have been killed.”12

Psychologist James Hillman found that in the dreams of most modern people, animals are pursuing us or we are trying to kill them.13 Hillman interpreted this as the result of suppression of our own primal instincts, which Hillman and many others believe is a primary cause of the epidemic of anxiety that inflicts our age. In the same vein, psychologist Aneila Jaffe observes: “Primitive man must tame the animal in himself and make it his helpful companion; civilized man must heal the animal in himself and make it his friend.”14

Clarissa Pinkola Estes’s bestselling book about the wild woman archetype, Women Who Run with the Wolves, is an example of the power of a symbolic association with wolves. People who live far from wild wolves have an unconscious desire to reconnect with nature, more than conserving the actual wild wolf, which few have even seen. Her book is really not about wolves at all but rather the need to restore our psychological connection with nature as a way to increase health.

The point simply is that to discredit the rich legacy of wolf folklore and mythology is denying human nature and nature itself. The modern myth of the “harmless wolf” is not only inaccurate but may have contributed to attacks and deaths by wolves in recent years.

As this book is being written, hungry wolves are starting to show up in broad daylight in the city limits of towns including: Sun Valley, Idaho; Jackson Hole, Wyoming; Anchorage, Alaska; Juneau, Alaska; Ironwood, Michigan; Toronto, Ontario; Reserve, New Mexico; Duluth, Minnesota; and Kalispell, Montana, hunting for garbage, killing pets, and testing humans. We know of three people in North America in the last decade, who were unarmed, that were killed by wolves, and many others have been attacked; some attacks were reported, and others not. We will list some of those attacks shortly.

People need to distinguish fact from fiction, and appreciate wolves for what they really are. Save the fairy tales and you save lives.

“He’s mad that trusts in the tameness of a wolf, a horse’s health, a boy’s love, or a whore’s oath.”

—William Shakespeare, King Lear (III, vi, 19–21)

The Wolf as a Cash Cow

“Every great cause begins as a movement, becomes a business, and ends up as a racket.”

—Eric Hoffer, The Temper of Our Time

The leader of the pack of environmental and animal rights groups promoting saving the wolf is Defenders of Wildlife, which idolizes wolves so much that the wolf is their logo. Founded in 1947 as Defenders of Furbearers, their initial target was banning steel-jaw leg hold traps and poisons. They began with one staff person and fifteen hundred members. Today, Defenders’ mission statement is to promote “science-based, results-oriented wildlife conservation,” and “saving imperiled wildlife and championing the Endangered Species Act.”

They do this with a staff of 150 and, they say, over one million members.15 According to Charity Navigator, in fiscal year 2010, Defenders of Wildlife had an annual budget of $32,595,000 and its president received an annual salary of $295,641.16 Much of this is due to their “Save the Wolf” campaign.

The American Institute of Philanthropy gives Defenders of Wildlife a “D” for the percentage of its budget spent on charitable purposes—43 percent—noting that the organization sends out ten to twelve million pieces of direct mail each year to draw in about $25.6 million.17

This USPS tidal wave hardly seems “green.” Appeal letters are written by special direct mail and telemarketing firms—who crank out the same kinds of letters for all kinds of causes—using focus groups to determine the most emotionally engaging pitch. Sometimes the science behind such appeals is questionable, or wrong, but what you read is crafted to have the greatest potential for drawing in donations. For example, a common emotional hook is a crisis—fear that if you don’t give, something terrible will surely happen. The opening line for the 2012 Defenders “Campaign to Save America’s Wolves” on their website is: “America’s Wolves Need Our Help!” and it is followed by: “America’s wolves were nearly eradicated in the 20th century. Now, after a remarkable recovery in parts of the country, our wolves are once again in serious danger.”18

Of course, if something bad does occur, then they can make another appeal based on guilt—if you had donated more this would not have happened.

Another popular appeal is sentimentality, such as Defenders’ “Won’t you please adopt a furry little pup like “Hope”? Hope is cuddly brown wolf . . . Hope was triumphantly born in Yellowstone.”

For the record, the US Fish and Wildlife Service does not name wolves. They give them numbers. Nonetheless, the World Wildlife Fund also offers donors the chance to “Adopt a Wolf.”19

Another popular appeal is to identify a dastardly, cruel enemy, who if not stopped will surely cause great damage or extinction of a species, or already is doing so. The American Farm Bureau has been a favorite target. If a magazine, radio, or TV show does not report full support for uncontrolled wolf restoration, it also may become a target for hate mail. In short, from a psychological standpoint, the organization must operate as a crisis addict to keep itself in business, for the new wolf is a cash cow.

To Defenders’ credit, they initially had a Wolf Compensation Fund to pay ranchers for livestock lost to wolves. However, on August 20, 2010, Defenders announced cancellation of their wolf compensation fund so states and tribes could take over the cost while they worked with farmers and ranchers on non-lethal means of wolf control.20 This has placed a heavy burden on states, diverting funds that could have served more critical wildlife needs. Should environmental groups that have supported wolf restoration in excess of US Fish and Wildlife Service projected population of sustainable numbers of wolves be held responsible for damages that the excess populations of wolves cause?

Ranchers and farmers additionally complain that the compensation was paid only for confirmed kills, not lost animals or kills that several species—bears, coyotes, mountain lions, eagles, ravens, foxes—feed on before it can be determined which killed the cow or sheep in the first place. (See the chapter “Collateral Damage” on why compensation claims so often go unsupported.)

Pro-Wolf Organizations

A Google search for “Save The Wolves” today comes up with 128,000,000 results as many organizations and petitions have joined the pack when they saw that wolves were cash cows. In addition to Defenders of Wildlife, some of the best-known “Save the Wolf” groups that use both “educational” campaigns and litigation include: The Center for Biological Diversity, EarthJustice, Friends of Animals, Humane Society of the United States, the Natural Resources Defense Council, WildEarth Guardians, World Wildlife Fund, and the Sierra Club.

A major theme running through “Save the Wolves” appeals is that wolves are in danger of extinction. This, of course, is false. There may be as many as one hundred thousand wolves in the wild in North America, and despite USDA Wildlife Services, USFWS, United States Park Service, and state natural resources and agricultural agencies removing problem wolves, roadkill, natural mortality, and legal and illegal hunting, the North American wolf population is growing appreciably and spreading. Add to this the at least three hundred thousand (possibly five hundred thousand) wolves and wolf-dogs that are living in wolf sanctuaries, zoos, and education centers, running loose in the wild with packs of feral hybrid canines, or being kept as pets in North America.

Defenders of Wildlife also uses public opinion polls to support their advocacy, but not the same polls that unbiased researchers conduct. For example, on the Defenders’ website, they report that in response to an NBC Dateline segment on wolves, more than fifteen hundred viewers responded, with less than 11 percent saying they are opposed to wolf reintroduction.21 They go on to selectively draw on a few surveys to show that people everywhere favor wolves, although they acknowledge that people in rural areas are more likely to feel negatively about wolves.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, who funds “wolf advocates” in the field, states that “Persistent intolerance among humans . . . is one of the two greatest threats to wolves, the other being loss of habitat.”22 On their website,23 NRDC says:

The howling wolf is the very icon of wilderness in the American West. Once all but extinct, today some 1,700 wolves roam the Northern Rockies. Despite this magnificent comeback, the future of wolves is once again in jeopardy. Congress has stripped them of their endangered species protection, leaving wolves at the mercy of states planning to kill hundreds of them.

And of course they add, “DONATE.”

Another online NRDC pitch for wolf donations wants people to be outraged and donate to help them defend Wyoming’s wolves:

I am outraged that Wyoming allows wolves to be shot on sight across some 85 percent of the state. I want to help NRDC fight to end the slaughter and restore Wyoming’s wolves to the endangered species list, where they belong right now. Please use my tax-deductible gift to save the wolves and defend our environment in the most effective way possible.24

Wolf advocates often launch attacks in the media to discredit and attack those people who want wolves managed, portraying them as intolerant, fearful, uninformed, naive, somehow inferior and mentally unsound and/or unethical, and even a threat to society. If someone targeted does lose their temper, it only helps the pro-wolf advocate organizations raise money as they can say, “See, I told you so.”

This is an example of how wolf advocates can take on the personality of the “big, bad wolf” who may attack anyone who is not part of their pack without warning at any time.

The Humane Society of the United States, the nation’s largest animal rights group, says on their website as of November, 2011—“Social, family-oriented, and highly adaptable—wolves have a lot in common with humans. And while there’s no record of a healthy, wild wolf ever attacking a person in the United States, old myths and fears plus competition for land and prey threaten the survival of this wild canine.”25 (We will discuss wolf attacks on people in a later chapter.)

The April/May 2012 issue of Charity Watch, Charity Rating Guide and Watchdog Report gave HSUS a “D” unsatisfactory rating for the second year in a row based how much money it spends to raise money. In contrast, PETA gets a “C+” and the American Red Cross and the Wildlife Conservation Society get an “A.”26

Earthjustice’s website’s wolf page is entitled “Wolves in Danger,” and proclaims: “For the past decade, Earthjustice was instrumental in protecting the gray wolves in court. Our work is now shifting to Congress where there have been legislative attempts to derail wolf recovery and push these animals to the brink of extinction.” This is far from accurate.

The Sierra Club uses the slogan “Those faithful shepherds” on their wolf campaign page. The Sierra Club states that they “Educate the public about wolves and their biology to dispel negative stereotypes.”27 However, the Sierra Club calls the wolf a “Species at Risk,” when in reality wolves are plentiful in many parts of North America, and abroad, and several times as many wolves and wolf hybrids are in captivity.

In response to the 2012 arrival in California of one wolf from Oregon, the Center for Biological Diversity sent out an email message that begins: “Wolves are smart, fast, curious and strong. It was inevitable that they’d find their way to California. It is not inevitable, though, that they’ll survive. The livestock industry has already vowed to kill any wolf it sees and is gearing up its lobbying machine to keep them out of the state . . . Make a generous gift to support our California Wolf Fund,” ends the message.28 A perfect example of negative stereotyping and polarization.

It’s also true that a new pack of wolves was sighted in northern California in 2015—a family of two adults and five pups. One of the parents is dark, and most of the pups are dark also. Black or very dark fur is a sign of wolves hybridizing with dogs.

Wild wolves are one thing, but APHIS trappers in northern CA have seen and trapped a number of wolves and/or wolf-dogs for the last decade. Some are raised by people and purposefully released into the wild or escaped, and often wolf-dogs are used by illegal marijuana growers to guard gardens, APHIS agents report.

None of the major pro-wolf groups say much about wolves also representing a danger to people and livestock due to up to fifty diseases they may carry.

“Save the Wolf” messages ultimately are picked up by the general media, which further inflames polarization as advocates are paid to dramatize situations to help raise money for their salaries.29 “Save the Wolf” in many cases actually means “Save my salary.”

Often the messages of the wolf advocates are misleading or simply wrong. For example, a common campaign message of many pro-wolf groups is that browsing elk are destroying aspens in Yellowstone National Park. Introducing wolves, they say, is the best way to restore the aspens, establishing a “landscape of fear,” that keeps elk away from aspens, which results in habitat improvement that benefits many other species.

Fifteen years after wolves were released into Yellowstone, in the September of 2010 issue of Science Daily, USGS scientist Matthew Kauffman reports that elk are continuing to browse on aspens, regardless of wolves. Kauffman states: “This study not only confirms that elk are responsible for the decline of aspen in Yellowstone beginning in the 1890s, but also that none of the aspen groves studied after wolf restoration appear to be regenerating, even in areas risky to elk.”30

US Fish and Wildlife Service

There could be no successful campaign to bring back wolves without the support of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which has jurisdiction as wolves are an endangered species. Since the l980s USFWS has promoted wolf recovery programs all around the United States through news media, public hearings, interviews, websites, exhibits, and personal appearances.

One of the most visible parts of this program was the widespread public review of Environmental Impact Statement that led up to the 1995–96 relocation of Canadian wolves into the Northern Rockies. Ten years after the relocation took place, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department did a review of the predictions made by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in that EIS. This is what they found:

Despite research findings in Idaho and the Greater Yellowstone Area, and monitoring evidence in Wyoming that indicate wolf predation is having an impact on ungulate populations that will reduce hunter opportunity if the current impact levels persist, the Service continues to rigidly deny wolf predation is a problem.

The 1994 EIS predicted that presence of wolves would result in a 5 to 10 percent increase in annual visitation to Yellowstone National Park. On this basis, the EIS forecast wolves in the region would generate $20 million in revenue to the states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. WG&F reports that annual park visitation has remained essentially unchanged after wolf introduction. A later chapter will examine in detail the real economics of the wolf reintroduction.

WG&F states: “Wolf presence can be ecologically compatible in the GYA only to the extent that the distribution and numbers of wolves are controlled and maintained at approximately the levels originally predicted by the 1994 EIS –100 wolves and 10 breeding pairs.” USFWS . . . “has a permanent, legal obligation to manage wolves at the levels on which the wolf recovery program was originally predicated, the levels described by the impact analysis in the 1994 EIS.”31

In a September 2010 interview with the Bozeman Daily Chronicle, two leading federal wolf biologists, Ed Bangs of the US Fish and Wildlife Service and Doug Smith of the US National Park Service,32 state that from the beginning their long-term goal has been to delist wolves so they can be managed, which would mean controlled hunting.33

A number of wildlife biologists, including Dr. L. David Mech, Chair of the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Wolf Specialist Group, support that goal.34

Nonetheless, a lot of the general public believes any hunting of wolves is wrong, largely because of the way that wolves have been sold by wolf advocates. For example, a 1999 poll in Minnesota showed that while people favored wolf management, they preferred non-lethal methods.35 A 2004 poll in Ontario, which does have a native wolf population but not near any population centers, found that 70 percent of the public opposed hunting wolves, 88 percent oppose sport hunting of wolves, and 82 percent do not support killing wolves for their pelts.36 Such opposition also holds today for Scandinavia, where a 2003 study found that while a majority supported hunting wolves if livestock were being harmed, or wolves were entering cities, they did not favor a general wolf hunt.37

The problem is that nonlethal wolf controls seldom work, and if they do, it is short-term and costly. Issuing wolf sport hunting licenses is one way for state agencies to try to pay for the economic burden of wolf management, which is considerable; however, when this happens it raises the hackles of anti-hunting groups, who attack the agencies, forcing them to pay for their defense in court and in the political area.

Ohio State University researcher Jeremy Bruskotter reported in Bioscience in December of 2010, that the US Fish and Wildlife Service is essentially supporting the wolf advocates by suppressing research on the real and potential negative consequences of wolf populations, and this is contributing to the polarization of public opinion about wolves as well as misleading people about the negative consequences of expanding wolf populations.38

Selling Wolves to the General Public

Exhibits

In 1986, writer Rene Askins launched a traveling exhibit, the Wolf Fund, whose primary purpose was promoting the releasing of wolves into Yellowstone. To her credit, Atkins closed the Wolf Fund when the first wolf was released into Yellowstone.39

Defenders of Wildlife at one time also had a traveling wolf exhibit that was the largest such wildlife exhibit in the United States.

Many parks in the United States and Canada have educational exhibits about wolves, especially Yellowstone National Park and Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, where they also feature “howl-ins.” The same is true for US Fish and Wildlife refuges where wolves are found. Visiting a park and howling with wolves is a much different experience than living with them day to day.

Wolf Education Centers

In the United States and Canada there are at least seventy “Wolf Education Centers” where people may see wolves in captivity, and be exposed to exhibits and educational programs about wolves. Some of the most popular centers include: Wolf Park in Battle Ground, Indiana40; Wolf Education Research Center in Winchester, Idaho41; Colorado Wolf and Wildlife Center, Divide, Colorado42; Wolf Song of Alaska Education Center, Eagle River, Arkansas43; Wolf Conservation Center, South Salem, New York44; and Northern Lights Wolf Center-Golden, British Columbia.45

One of the most professional and popular wolf education centers is the International Wolf Center in Ely, Minnesota, which is located in the center of the Minnesota wolf population and was launched in 1989 by Dr. L. David Mech, one of the world’s most respected wildlife biologists who study wolves. Mech was once a firm believer in wolves in North America not attacking people, but he has reversed his position and has made Mark McNay’s landmark study on attacks available on his website, has sponsored a conference on attacks in Europe and Asia, and supports managing wolf populations with hunting.46

The International Wolf Center serves about fifty thousand visitors a year and conducts classes, workshops, and lectures in the United States and Canada. Such a facility located near Yellowstone National Park might enable visitors to see wolves and learn about them without the need to try to keep large packs of wolves running free in the park, especially near the highway where they can become habituated or spill over into nearby areas, thus reducing elk and moose populations, and/or attacking pets and eating roadkill and garbage. It would also increase the chances of preserving the existence of purebred wolves, for as you will learn in later chapters, wolves can and do mate with coyotes and dogs. Larger wolf populations that result in wolves interacting more with people will definitely increase the disappearance of purebred wolves and result in wolf-dog-coyote hybrids becoming the only “wild wolves.”

Books

There have been hundreds of books written about wolves since the first Earth Day in 1970.47 Here we will spotlight a few of the best-known wolf books, which have gained recognition and contain misleading information.

Following Jack London’s very successful novel, Call of the Wild, about a domestic dog that returns back to a wild state, his 1906 novel White Fang is about a wild three-quarters-wolf wolf-dog that becomes domesticated. Following its publication, Theodore Roosevelt declared that London was a “nature faker” and that some of the scenes in White Fang were “the sublimity of absurdity.”48 Nonetheless, White Fang has been made into several films, including a 1991 adaptation starring Ethan Hawke.

When he was just out of college and working in the Southwest for the US Forest Service, Aldo Leopold believed that predators—bobcats, wolves, cougars, and black and grizzly bears—should be removed from special areas so that big-game populations like deer and elk could build up those reserves and spill over into adjacent lands, increasing recreational opportunities for hunters and wildlife watchers. Teddy Roosevelt supported Leopold, as did ranchers, farmers, and hunters. The Kaibab Plateau, adjacent to the Grand Canyon, was chosen as a place to implement Leopold’s plan. When predators were eliminated at the Kaibab Plateau, the resident deer population exploded from less than ten thousand to nearly a hundred thousand. But the deer stayed on the reserve and ultimately ate out all the food, leading to massive starvation, a horrific crash in the deer population, and destruction of habitat that lasted for years after. That incident changed Aldo’s attitude toward predators.

One of the most commonly quoted pro-wolf passages appears in Leopold’s masterful treatise on man and nature, A Sand County Almanac (published in 1949), where he recounts an incident in 1909 when he shot a female wolf, but didn’t immediately kill her. Approaching the wounded animal to administer the final shot, he looked at the old she-wolf and watched “a green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known to her and the mountain.”49

This story is moving and fits perfectly with the mindset of “Save the Wolf” people, but it would be a mistake to think that Aldo Leopold believed that predatory animals like bears, cougars, wolves, bobcats, and coyotes shouldn’t be managed. In 1933, Aldo Leopold, the nation’s first professor of wildlife management, teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote in his textbook, Game Management (the first college wildlife management text that remains in use by many colleges today), in the chapter on predator control:

Predatory animals directly affect four kinds of people: 1. agriculturists; 2. game managers and sportsmen; 3. students of natural history; and 4. the fur industry. There is a certain degree of natural and inevitable conflict of interest among these groups. Each tends to assume that its interest is paramount. Some students of natural history want no predator control at all, while many hunters and farmers want as much as they can get up to complete eradication. Both extremes are biologically unsound and economically impossible. The real question is one of determining and practicing such kind and degree of control as comes nearest to the interests of all four groups in the long run.50

Additionally, in 1944, according to his biographer Curt Meine, the same year that Aldo Leopold wrote Thinking Like a Mountain, which contained his famous description of the “fierce green fire” in the eyes of a dying she-wolf, Leopold also wrote in a manuscript on predator management in Wisconsin:

No one seriously advocates more than a small sprinkling of wolves. When they reach a certain level they will certainly have to be held down to it. . . . In thickly settled counties we cannot have wolves, but in parts of the north we can and should.51

Aldo Leopold and his entire family were lifelong avid hunters. Estella, his wife, was the Wisconsin state women’s archery champion. In the Aldo Leopold Archives at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, there is a photo of Aldo’s son, Starker (who became a very prominent wildlife biologist and university professor, and who edited A Sand County Almanac after his father’s death), proudly standing beside a Mexican wolf that he shot in New Mexico in 1948.52

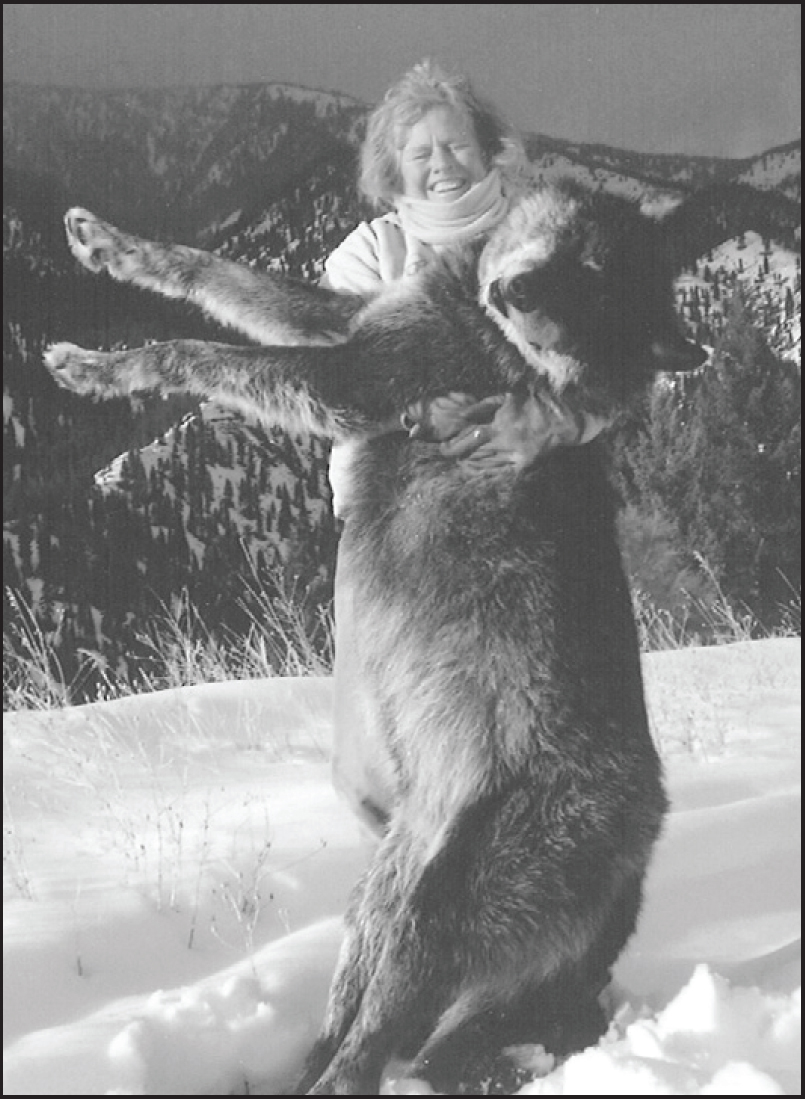

When this wolf was legally shot on February 15, 2010, it weighed 127 pounds and was approximately eight years old. The wolf had been collared in 2006 by Idaho Fish and Game, at which time he weighed 127 pounds, and they estimated he was four years old. The largest wolf weighed by Douglas W. Smith, wolf biologist for Yellowstone National Park, weighed 148 pounds. For reference, the woman in the photo is five feet, four inches tall; a signed affidavit from the woman in the photo is on file.

Naturalist, artist, writer, and predator bounty hunter Ernest Thompson Seton was an early pioneer of the modern school of animal fiction writing. His most popular work, Wild Animals I Have Known (published in 1898), contains the story of his killing of a renegade Mexican wolf named Lobo—“The King of the Currumpaw.” Seton later became involved in a literary controversy about writers who fictionalized natural history and distort wildlife biology and behavior—“nature fakers” as Teddy Roosevelt called them. In a 1903 article in the Atlantic Monthly, John Burroughs charged Seton with purposefully deceiving people with his writing. The controversy lasted four years involving many important American environmental and political figures of the day, including Teddy Roosevelt, who negotiated a deal with Seton to clean up his act.53 More about this in the section on the documentary film made about Seton’s wolfish tale, “The Wolf That Changed America.”54

Never Cry Wolf is Farley Mowat’s 1963 account of a young government biologist who in 1958 is flown to the tundra plains of Northern Canada to study the area’s wolf population and gather proof of the ongoing destruction of caribou herds by wolves. After locating them on the remote tundra, the biologist contacts wolves as he discovers a den with pups and devoted protectors of their young. And in the absence of caribou, the wolves happily feed on mice and lemmings. The biologist meets two Inuit who tell him their own stories about the wolves. As he learns more and more about the wolf, he comes to fear the onslaught of hunters out to kill the wolves for their pelts. Ultimately, he runs naked with the wolves as they chase a herd of caribou. The book was made into a popular Walt Disney feature film called Never Cry Wolf in which all the wolves seen on camera were tame. The film was nominated for one Academy Award (Best Sound), and it won several other awards for “Best Cinematography.” Posters advertised the movie as “based on a true story.”

While the book is supposedly based on a real-life experience, Inuits refer to Mowat as “Hardly Know It.” Scientists agree. Writing a review in Canadian Field-Naturalist in 1964, Canadian Wildlife Federation officer Alexander William Francis Banfield, who supervised Mowat’s field work, accused Mowat of blatantly lying, as Mowat was part of a team of three biologists, and was never alone. Banfield also pointed out that a lot of what was written in Never Cry Wolf was not derived from Mowat’s first-hand observations, but were lifted from Banfield’s own works, as well as those of Adolph Murie’s studies of wolves on Mount McKinley. Ultimately, he compared Never Cry Wolf to “Little Red Riding Hood,” stating that “both stories have about the same factual content.”55

Wolf biologist L. David Mech writes about the book: “Whereas the other books and articles were based strictly on facts and the experiences of the author, Mowat’s seems to be basically fiction founded somewhat on facts.”56 Ethologist, Dr. Geist, calls Never Cry Wolf “a brilliant, literary prank.”

Written before Mark McNay’s documentation on wolf attacks and the deadly wolf attacks of 2005 and 2010, Barry Holston Lopez’s Of Wolves and Men (published in 1978) explores many aspects of the relationship between people and wolves through history, and clearly states that wolves can and do kill people, but he does not acknowledge any attacks on white people in North America in the twentieth century. He says that while most Native American tribes consider wolves to be very important spiritually, seeing wolves as the ancestors of man, in the majority of Native American tribes, wolves were killed for body parts used in rituals, fur for clothing, to stop them raiding food caches, and wolf pups were considered a delicacy.

After surveying literature, mythology, and folklore from around the world, and trying to raise two red wolves, in the “Epilogue” of Of Wolves and Men, Lopez concludes: “Wolves don’t belong living with people. It’s as simple as that.”57

An Associate Professor of History at Notre Dame, Jon T. Coleman admits at the outset of his 2004 book Vicious: Men and Wolves in America that he is an “animal person.” Vicious begins with a description of John James Audubon watching an Ohio farmer catch three wolves in a pit trap and then slowly kill them. He explains the farmer’s behavior as an example of “theriophobia”—an excessive fear of wild animals, saying, “Oblivious to the actual behavior of wolves, anti-wolf people based their hatred on ‘myths, tales, and legends.’”58 To generalize all people who do not like wolves as being the same is engaging in cheap stereotyping, which is hardly scholarly or accurate. Coleman fails to say if the farmer had lost livestock, pets, or even friends to wolves prior to this time, which would mean the farmer was simply very angry and seeking revenge.

On the same page, Coleman states, “There is no record of a non-rabid wolf killing a human in North America since the arrival of the Europeans.” The irony is that Audubon personally investigated and confirmed the death of a man by three wolves in 1830.60

Two problems with finding information about wolf attacks is that until very recently there was no reliable recording system, you have to look for newspaper reports. And, when people are lost in the woods and are never found, or their remains are found later, confirming if they were killed by wolves or not is very difficult or impossible. When Young and Goldman looked for records of wolf attacks on humans before 1900 in North America, they found thirty accounts of attacks, and six possible human kills.60

Coleman’s book came out in 2004, two years after Mark McNay’s report on wolf attacks, yet he gives no mention of this research. Could the wolf attack deaths of Kenton Carnegie in 2005, and Candice Berger in 2010 have been averted if people like Coleman were not spreading misinformation about potential dangers of wolves? None of these three young people were carrying firearms or even pepper spray when they were attacked.

On page fourteen, Coleman states, “In 1995 the Fish and Wildlife Service set fourteen wolves from Alberta, Canada, loose in Yellowstone. Nine years later the population had grown to 148 predators, and packs of ‘non-essential’ gray and Mexican wolves loped in Idaho, Arizona, and New Mexico.”

Actually, a total of sixty-six Canadian wolves were released into Yellowstone and Idaho by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, establishing “experimental, non-essential” populations according to article 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act. In 2005, the wolf population of the Greater Yellowstone area alone was estimated at a minimum of 325 wolves, not 148. Adding together the wolves in Idaho with those in the Yellowstone area and those in Montana, some of which were already living in the state before the 1995–96 releases, results in at least fifteen hundred wolves in the Northern Rockies, some say the number is at least three thousand.

In March 1998, the US Fish and Wildlife Service released three packs of Mexican wolves, bred in captivity, into the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in Arizona, and eleven wolves into the Blue Range Wilderness Area of western New Mexico. There are currently approximately ninety-seven Mexican wolves in the wild in both Arizona and New Mexico. (More about Mexican wolves later.)

Coleman goes at great length to deride the negative mythology, folklore and fairy tales that originated from Europe, failing to report the numerous well-documented attacks and killings of people by wolves throughout Eurasia, and the importance of folk tales, fables, and fairy tales in educating children to avoid becoming victims.61

Despite the bias of the author, the many inaccuracies of the work and his lack of understanding of psychology, folklore, and mythology, Vicious won awards from the American Historical Association and the Western Historical Association. A falsehood often repeated does not make it true.

Magazine Articles

There have been thousands of articles about wolves in major national magazines and newspapers, including National Geographic, The New York Times, Audubon, Sierra, Newsweek, Wall Street Journal, etc., as well local newspapers and magazines. The majority of these favor wolf restoration, and most are written by journalists parroting what they are told by wolf advocates from environmental groups and federal and state agencies charged with wolf management.

An article worth noting, “Cry Wolf: How A Campaign of Fear and Intimidation Led to The Gray Wolf’s Removal from the Endangered Species List” by James William Gibson that appeared in Earth Island Journal, Summer 2011, illustrates one way the “Save the Wolf” campaign has often used self-righteousness to create enemies to hate.62

Gibson, a professor of sociology at California State University at Long Beach, claims that “an extreme right-wing culture that celebrates the image of man as ‘warrior,’ recognizes only local and state governance as legitimate, and advocates resistance—even armed resistance—against the federal government . . . built around some shared myths that focus on the evils of wolves in general and the Rockies’ wolves specifically” is engaging in “fear-driven demagoguery” targeting pro-wolf groups and individuals, and this is the real reason why wolves were delisted, and not biology. In a December 8, 2011, op-ed article in the Los Angeles Times, Gibson describes proponents of hunting wolves to manage their population as “paramilitary militia advocates.”

“Afraid for their lives and their families, regional wolf advocates stopped participating in public hearings held by fish and game agencies and legislative committees and retreated to the relative safety of the Internet to spread their message,” Gibson says. He charges that “a dysfunctional political system in which fear—both irrational fear and fear harnessed for political gain—determines policy.”

“In the entire twentieth century, wolves attacked about fifteen people in North America, killing none,” Gibson claims. He does admit, “In 2010, wolves did kill a woman jogging on the outskirts of her Alaskan town,” but he makes no mention of other attacks and fatalities that you will soon learn more about.

Little or no mention is made of the numerous professional wildlife biologists, and many present and former state and US Fish and Wildlife Service biologists, who support wolf management and controlled hunts—none of which belongs to right-wing paramilitary organizations. (Nor do any of the contributors to this book.)

This is not to say that some ranchers, hunters, and others have not written or said negative things about wolf supporters. Gibson, however, makes no mention of the swarm of threats in electronic media and direct personal attacks that have been made by wolf advocates to anyone who differs with their view. He fails to acknowledge how the whole situation is made worse by “wolf advocates” who are paid to carry on campaigns against anyone who questions their agenda, keep controversies going, and fuel crises that can be used by their employers to raise money. (See the five-part series “Environment Inc.” by Pulitzer Prize–winning Sacramento Bee investigative journalist Thomas Knudsen, documenting how large environmental groups use inflammatory articles, exaggeration, and even purposeful lying to keep themselves visible and money flowing in.)63

An important book about the politics of the wolf wars of the Northern Rockies is Yellowstone Wolves: A Chronicle of the Animal, the People and the Politics by Cat Urbigkit.64 Urbigkit, a Wyoming journalist and sheepherder, traces the history of wolves in the Yellowstone area, clearly showing that while hunting, trapping, and poisoning wolves knocked the population down in the mid-1900s, wolves never were eradicated from that area. She traces the history of groups, especially Defenders of Wildlife, who began sending out Action Alerts as early as 1992, and the federal government, who declared at public meetings about wolf reintroduction in the early 1990s, “As the wolf population grows, support can grow along with it . . .” Urbigkit’s story of how she and her husband filed suit to block the USFWS wolf relocation program as wolves were already present in the Northern Rockies is a true example of heroism.

In response to Gibson’s inflammatory negative stereotyping, Urbigkit quotes a January 1999 editorial in the national newsletter of American Farm Bureau by AFB President Dean Kleckner that describes what happened when the AFB filed a lawsuit to have introduced Canadian wolves removed from the Northern Rockies and returned to Canada:

Defenders of Wildlife launched a nationwide campaign against Farm Bureau in the press, television, radio and Internet, falsely describing our organization and our lawsuit. [AFB did not call for killing off wolves. It simply wanted them removed from the area.]

Wolf stocking advocates, incited by Defenders of Wildlife, organized a campaign of harassment and intimidation against the Bureau with the aim of forcing us to abandon our own farmer-written policies and drop the lawsuit. We have received several bomb threats and threats against the lives of Farm Bureau officers and their families. Even a federal judge’s life was threatened. [The judge found that wolves could be captured humanely and returned to Canada.]

Working Assets (in support of Defenders of Wildlife) brags about sending us 34,000 letters and calls. . . . Defenders of Wildlife and Working Assets crossed a line when they intended to shut down our phone system and encouraged callers to harass us into dropping our case against the Department of Interior’s illegal program.

The American Farm Bureau filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission and the FBI regarding the threats they had been subjected to, which is how such pressures should be handled.

Films

There are many documentaries and feature films about wolves.65 Nearly all support the “Save the Wolf” movement, and many have inaccuracies, such as Wild Wolves on PBS NOVA, which includes an interview with USFWS wolf biologist Ed Bangs, where Bangs states:

The studies that we’ve done and that other people have done indicate that wolves normally kill less than one-tenth of one percent of the livestock available to them. To date, in the past fifteen years in the northern Rocky Mountains, we’ve lost an average of about five cattle and five sheep per year to wolf depredations.

Those statistics do not represent what is actually happening. For example in 2010, wolves killed sixty-five livestock (thirty-seven cattle and thirty-three sheep), three horses, and one dog in Wyoming alone.66 Bangs continues:

You know when you teach your dog to not go out of the yard or not go in the flower bed—and your dog learns that for the rest of its life? It’s just something it won’t do? That’s the same reason that wolves never attack people. Behaviorally, they just don’t recognize people as anything they want to screw with. And they live their entire lives without ever trying it.67

That statement will also be corrected shortly.

In 1990, naturalist, cinematographer, director, and author Jim Dutcher purchased wolf pups born in captivity and was allowed a permit to set up a twenty-five-acre wolf observation camp in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho, where he stayed, later joined by his wife, Jamie. The pups were first raised in captivity and then released in the larger pen. Dutchers lived in the enclosure until 1996, raising and documenting the captive pack of wolves and their socializing behavior. The wolves, which became known as the “Sawtooth Pack,” then became property of the Wolf Education and Research Center (a non-profit organization he founded) in conjunction with the Nez Perce and moved to northern Idaho. The Dutchers made a documentary film, Wolves at Our Door,” which won a Primetime Emmy.

The wolves were allowed to roam freely in the twenty-five-acre enclosure, but these wolves were raised by the Dutchers, making them habituated. While the film may have made people feel less afraid of wolves, it also may have helped promote people buying and raising wolves as pets.

According to Rick Hobson, who once worked for the Dutchers, much of the film is not at all based on what actually happened. Hobson says, “The film gives the impression that the Sawtooth Pack was given to the Nez Pierce in Idaho, but this isn’t the case . . . The wolves were sold for tens of thousands of dollars to a non-profit organization hastily created to save the wolves, after Dutcher had commented that euthanizing the wolves was an option he was considering. The wolves came with a restrictive agreement which gave most photographic rights to Dutcher. The non-profit group couldn’t even use images of the wolves on merchandise in order to support itself or the wolves.”68

In feature films, we generally find a more balanced coverage of wolves. A good example is Never Cry Wolf based on Farley Mowat’s 1963 bestselling book, adapted for the big screen in 1983 by Carroll Ballard. However, in the May 1996 issue of the popular Canadian magazine Saturday Night, John Goddard wrote a heavily researched review article entitled “A Real Whopper,” in which he poked many holes in Mowat’s claim that the book was non-fictional. Goddard also reported that Mowat told him, “I never let the facts get in the way of the truth.” While Mowat called Goddard’s article “bullshit, pure and simple,” he refused to refute Goddard’s main claims.69 This is an example of misrepresenting the facts with emotion. Films often, like books, distort the behavior and tendencies of wolves in order to romanticize them, which do injustice to the perception of wolves, and consequently do injustice to the people who have to live with wolves.

In 2011, a feature film The Grey, a wilderness survival story written and produced by Joel Carnahan and starring Liam Neeson, describes a plane loaded with Alaskan oil field workers crashing in the dead of winter in a snowy area. The oilmen were subsequently attacked by hungry wolves. As expected, many wolf advocates howled about this film, nonetheless The Grey made more than three times its production costs at the box office, and continues to be popular on streaming services.

Could such a thing happen? Some wolf advocates adamantly assert “NO!,” however as you will learn later, there is a long history of wolves attacking people in Europe and Asia during times when food was short.

Hope for the Future

As the federal government seeks to turn wolf management over to states, and habitat conservation organizations seek to have the wolf delisted and managed by hunting, pro-wolf groups counter with a seemingly endless escalating barrage of legal challenges accompanied by huge mass mailings and other propaganda. These legal attacks slow down and impede management of wolves as it forces agencies to spend money on legal costs, rather than put it to use in research and field work.

People do want to hear the truth about wolves. In the following pages, you will learn more about what that is. Between 2010 and 2014, three different lawsuits were filed challenging Wyoming’s plan to manage wolves, one in federal court in Colorado and two in federal courts in Washington, DC, and there are legal challenges to nearly every wolf population in the lower forty-eight states. For wolf advocates, wolves clearly are cash cows in wolf fur.

“Environmentalists routinely exaggerate problems so as to alarm people and get support for their agendas.”

—John Naisbitt, Mind Set! 70

Endnotes:

1. Chase, Alston. In a Dark Wood: The Fight Over Forests and the Rising Tyranny of Ecology. (NY, NY: Houghton-Mifflin, 1995), xiii.

2. Kellert, R.S. “Public Perceptions of Predators, Particularly the Wolf and Coyote,” Biological Conservation 31 (1985), 167–189.

3. Urbigkit, Cat. Yellowstone Wolves: A Chronicle of the Animal, the People, and the Politics. (Ohio: McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company, 2008), 28.

4. Ibid.

5. Murie, Adolph. The Wolves of Mount McKinley. (University of Washington Press, 1985).

6. Allen, Durwood and L. David Mech. “Wolves Versus Moose on Isle Royale,” National Geographic, (Feb. 1963), 200–219.

7. Leopold, A. Starker, et al. “Wildlife Management in the National Parks.” (National Park Service, 1963).

8. Williams, CW, Gordan Ericsson, and Thomas Herbelein. “A Quantitative Summary of Attitudes Toward Wolves and Their Reintroduction (1972–2000),” Wildlife Society Bulletin, 30 (2002), 1–10.

9. Lopez, Barry Holston. Of Wolves and Men. (Scribners, 1978), 4.

10. http://www.livescience.com/44875-werewolves-in-psychiatry.html

11. White, T.H. The Book of Beasts. (New York, NY: Putnam, 1954), 59.

12. Lopez, Barry. Ibid.

13. White, Johnathan. Talking on the Water: Conversations About Nature and Creativity (Sierra Club Books, 1994), 121–136.

14. Jaffe, Aniela. “Symbolism In The Visual Arts,” in Man and His Symbols, ed. Carl Jung. (New York, NY: Dell, l968), 266.

15. http://www.defenders.org/about_us/history/index.php

16. http://www.charitynavigator.org/index.cfm?bay=search.summary&orgid=3605

17. http://www.charitywatch.org/articles/defendersofwildlife.html

18. http://action.defenders.org/site/PageServer?pagename=savewolves_homepage

19. http://www.worldwildlife.org/gift-center/gifts/Species-Adoptions/Gray-Wolf.aspx?gid=13&sc=AWY1000WCGP1&searchen=google&gclid=CLzrv6rKw6ACFR6kiQodFmSybA

20. http://www.defenders.org/programs_and_policy/wildlife_conservation/solutions/wolf_compnsation_trust

21. http://www.defenders.org/programs_and_policy/wildlife_conservation/imperiled_species/wolves/america_votes_yes!_for_wolves.php

22. http://www.nrdc.org/wildlife/habitat/esa/rockies02.asp

23. https://www.nrdc.org/resources/ensure-thriving-populations-wolves

24. https://secure.nrdconline.org/site/Donation2?df_id=8040&8040.donation=form1

25. http://www.humanesociety.org/animals/wolves

26. http://humanewatch.org/index.php/site/post/hsus_earns_some_detention

27. http://www.sierraclub.org/lewisandclark/species/wolf.asp

28. http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/publications/earthonline/endangered-earth-onlineno605.html

29. http://www.pbs.org/now/shows/609/index.html

30. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/09/100901111636.htm

31. http://www.pinedaleonline.com/wolf/wolfimpacts.htm

32. http://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/article_32c72a40-3c5b-11df-91e5-001cc4c002e0.html

33. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1040&context=vpc16

34. http://www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/scientific/challenge_mech.asp

35. http://www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/intermed/inter_human/survey_shows.asp

36. http://www.wolvesontario.org/wolves/Full%20Wolf%20Poll%20March%2011%202004%20revised.pdf

37. http://www.wildlifebiology.com/Downloads/Article/477/En/10_4_ericsson.pdf

38. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/12/101206093703.html; http://bruskotter.wordpress.com/

39. http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,20108666,00.html.38;

41. http://www.wolfcenter.org/default.aspx

42. http://www.wolfeducation.org

43. http://www.wolfsongalaska.org/education_center_tour.html

45. http://www.northernlightswildlife.com

46. http://www.wolf.org/wolves/index.asp

47. http://www.inetdesign.com/wolfdunn/wolfbooks

48. Carson, Gerald. “T.R. and the ‘Nature Fakers,” American Heritage (February 1971), 22.

49. Leopold, Aldo. “Thinking Like a Mountain. A Sand County Almanac. (Oxford University Press, 1949), 130.

50. Leopold, Aldo. Game Management. (University of Wisconsin Press, 1933), 230.

51. Meine, Curt. Aldo Leopold, His Life and Work, (1988). University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI, pg. 458.

52. A. Starker Leopold with wolf, July 1948, Aldo Leopold Papers, series 3/1, box 85, folder 7. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/AldoLeopold

53. Carson, Gerald. Op. Cit.

54. http://factoidz.com/lobo-king-of-the-currumpaw/

55. Banfield, A.W.F. “Never Cry Wolf.” Canadian Field Naturalist 78, (January-March 1964), 52–54.

56. Mech, L. David. The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. Natural History Press (Doubleday Publishing Co., N.Y, 1978), 389.

57. Lopez, Barry Holston. Of Wolves and Men. (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978), 280.

58. Coleman, Jon T. Vicious: Men and Wolves in America (Yale University Press, 2004), 3.

59. Audubon, J.J., and J. Bachman. The Quadrupeds of North America. (New York: Wellfleet Press, 1851–1854).

60. Young, S. and E. Goldman. Wolves of North America, Vol. 1 and 2. (Dover, 1944).

61. Von Franz, Marie-Louise. Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales. (Shambala, Boston: 1995).

62. http://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/eij/article/cry_wolf

63. http://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/eij/article/cry_wolf

64. Urbigkit, Cat. Yellowstone Wolves: A Chronicle of the Animal, the People, and the Politics. (McDonald and Wordwood, 2008).

65. http://www.bullfrogfilms.com/catalog/wolf.html

66. http://wolves.biginterest2u.com/docs.html

67. http://www.pinedaleonline.com/news/2012/02/Wyomingwolfpopulatio.htm

68. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/wolves

69. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0326413/reviews

70. http://www.salon.com/1999/05/11/mowat/singleton

71. John Naisbitt, Mind Set!: Eleven Ways to Change the Way You See—and Create—the Future. HarperBusiness; Reprint edition (December, 2008).

Photo credit: Dennis Donahue/Shutterstock.com