CHAPTER 5

WHIP, SPUR,

AND SADDLE

After the race was over,

After Diablo won,

After your pockets were empty

You by the bookmakers stung . . .

—DITTY FROM BROOKLYN HANDICAP OF 1893

Just a few blocks east of Ocean Parkway at Avenue W, where Olmsted’s grand avenue bends for its final run to the sea, there is a church whose congregants believe, like Lady Moody, that only mindful adults should be let into the kingdom of God. The First Baptist Church of Sheepshead Bay, founded in 1901, is set midblock amidst a hodgepodge of homes, an ashlar stone edifice with steeple tower and courtyard close. It is one of four very different houses of worship on East Fifteenth Street between Gravesend Neck Road and Avenue X, a homey strip of urban turf tucked beneath the embankment of the old Brighton Beach Line. The neighborhood is a rainbow of diversity, where elderly Italians and Sephardic Jews mix with recent immigrants from south China, Pakistan, Central America, and the former Soviet Union. Century-old row houses and wooden bungalows linger next to new Chinese infill condos, with their stainless-steel railings and telltale potted squash vines. Across the street and just below First Baptist is the Pentecostal Mission Rey de los Reyes. Closer to the Neck Road subway station is a handsome modernist building—the Brooklyn Chinese Christian Church, led by a youthful minister who claims his father invented orange beef. Between is the Burmese Masoeyein Sāsanajotika Buddhist Temple, whose saffron-robed monks are often seen in the produce section of the Stop & Shop around the corner. From their modest sanctuary—a wood-frame bungalow behind a chain-link fence—comes the ethereal lilt of chanted sutras, drifting into the street to mingle with birdsong and rumbling trucks.

It’s hard to say whether it is the Baptists or the Burmese Buddhists who are the greater anomaly in this part of town. There are only a handful of Buddhist temples in all Brooklyn—the Dorje Ling Buddhist Center on Gold Street, with its alarming ketchup-and-eggs paint job; West Temple on Eighth Avenue in Sunset Park. And while Baptist churches are plentiful, most—both the storefront sort and those in grand old edifices—are in neighborhoods far north of Gravesend. Indeed, mapping the Baptist churches in Brooklyn yields an accurate spatial portrait of the borough’s African American community. The Baptist Church in America is largely a Southern institution, where it is far and away the largest Protestant denomination. A northern faction split off in 1845 over slavery, which white Southern Baptists overwhelmingly supported. Even today, the Southern Baptist Convention is 94 percent white. Black Baptists in the South formed their own churches and, as many moved north after Reconstruction, established new congregations in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, and New York. In New York City even today, the Baptist church is a black institution; most congregations are in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, Brownsville, and East Flatbush. What, then, explains the presence—and for nearly 120 years—of the First Baptist Church of Sheepshead Bay, its flock so far from the main pastures of African American culture in New York City?

First Baptist Church of Sheepshead Bay. Photograph by author, 2014.

As discussed in chapter 1, the black presence in Kings County dates back to the very earliest days of New Netherland. Africans lived in Gravesend, too, since at least 1651, when its English founding fathers petitioned Dutch authorities to allow them to charter “some ships in Holland” to bring in more settlers, especially indentured servants. Failing that, would the good directors consent to sell them “-Negroes or Blacks” to answer the manpower shortage? The men—Deborah Moody’s name is conspicuously absent, one hopes because of the good woman’s moral objection to slavery—pointed out that doing so would bring the company “double profits . . . from what we shall pay for those Negroes.”1 But the African Americans who built First Baptist had little to do with this far-off past. They came instead with horses, thorough-bred horses, to be exact, and the long-vanished tracks on which they ran—an infrastructure that once made southern Brooklyn synonymous with horse racing around the world. Washboard-flat agricultural land is the stuff of equine dreams, and Long Island had this in spades on its vast outwash plain. Racing thorough-breds is quintessential English sport, and among the first things the British did once Peter Stuyvesant signed over his colony was build a racetrack—the Newmarket course at Salisbury, about where the Garden City Hotel stands today in Nassau County. Opened in 1665 on the Hempstead Plains, it was the first such track in America (Long Island hasn’t been without one since). Racing came early to Kings County, too, with matches and foxhunts at Ascot Heath on the Flatlands plains. It provided a range of diversions for New York’s colonial masters, including races for women with prizes—“a Holland smock and chintz gown, full-trimmed”—going to the winners. A tavern nearby, Charles Loosley’s King’s Head, provided “Breakfasting and Relishes”—and plenty of ale—to huntsmen and punters.2 The Union course, America’s first earthen track (Ascot Heath was turf) opened in Queens in 1821, followed by the nearby Eclipse and Fashion tracks (where baseball’s first all-star game was played in 1858). After the Civil War, the Long Island racing scene moved to Jerome Park in the Bronx before settling, as we will see, in deep-south Brooklyn.3

In the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the beaches east of Coney Island became a favored playground of the Gotham elite. Three grand resort hotels—the Manhattan Beach, Brighton Beach, and Oriental—opened there by 1880, connected to the rest of the city by rail and streetcar lines. At these sumptuous places guests feasted on Long Island duckling, baked bluefish, and Jamaica Bay oysters; enjoyed light opera; and danced to the music of John Philip Sousa, Patrick Gil-more, and Carlo Cappa. Scores of the city’s wealthiest families summered there, and exclusive clubs like the University and the Union League made it their seasonal home. The first, largest, and most resplendent of the great hotels—by some accounts the most elegant hotel in the United States—was the Manhattan Beach, a towered, turreted, veranda-wrapped pile that opened in the summer of 1877. Designed by J. Pickering Putnam—a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts—the Manhattan was a breathtaking sight on a bright summer day, sprawling splendidly over six hundred feet of beachfront, its banks of windows bedecked and aflutter with striped canvas. It was all the brainchild of Austin Corbin, the brilliant, ruthless tycoon and Harvard Law graduate who created the modern Long Island Rail Road and was described in 1889 as belonging to “that tribe of human monsters who prey upon poor men, who combine the natures of hog and shark . . . who are never more pleased than when they are bleeding those who are brought within reach of their ‘devil-fish’ grasp.” When he wasn’t fleecing farmers or immigrants (in one extraordinary scheme, he convinced the mayor of Rome to send Italian peasants to sharecrop a plantation he wrangled from the family of South Carolina secessionist senator John C. Calhoun), Corbin busied himself hating Jews—banning them from his hotels and founding, in 1879, the American Society for the Suppression of the Jews. What irony that his namesake street today—Corbin Place in the Manhattan Beach neighborhood—is home largely to Russian and Sephardic Jews, most of whom frankly couldn’t care less about Corbin and his grim society. In typically pragmatic New Yorker fashion, the residents rejected an initiative some years ago to change the street name; it was simply not worth all the hassle and expense.4

The Brighton Beach Hotel, 1903. Detroit Publishing Company Photographic Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

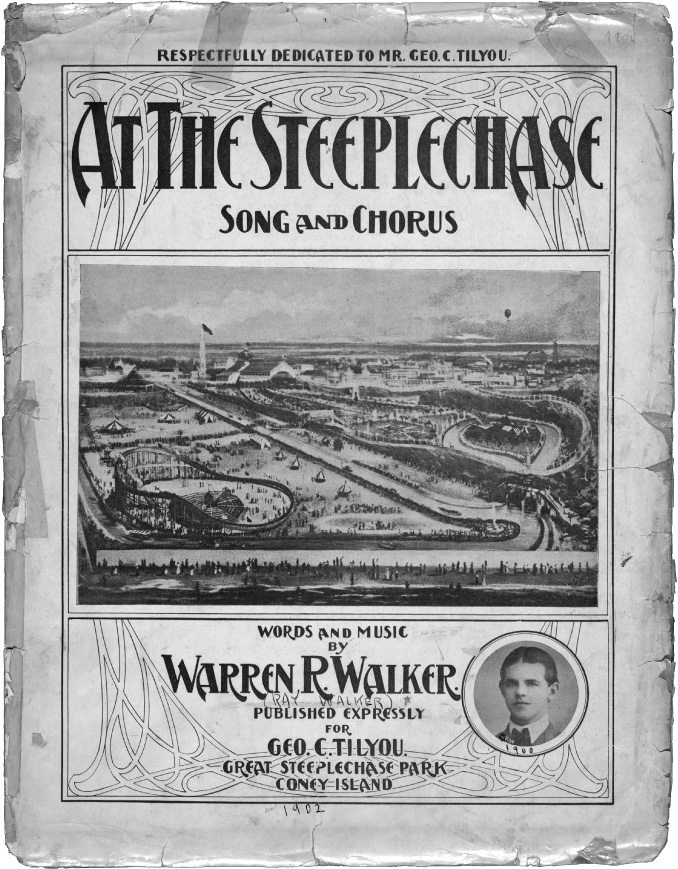

Such a great gathering of wealth in a horse-powered age meant a ready market for the Sport of Kings. Impromptu horse races were already being run on Sundays along Ocean Parkway. Entrepreneurs soon stepped up to meet demand. The first of several racetracks to open in Brooklyn was the Brighton Beach, established in 1879 by William A. Engeman. This was followed by a world-class track at Sheepshead Bay, developed by the posh Coney Island Jockey Club. Six years later a third establishment was opened at Gravesend by the Brooklyn Jockey Club. The three courses drew vast crowds of New Yorkers to the Brooklyn shore, rich as well as poor. The influx helped fuel a building boom in Coney Island, culminating in the 1897 opening of Steeplechase Park, where the chief attraction—appropriately enough—was a gravity-powered “coaster” ride known as the Steeplechase Horses. The relationship between the tracks and the hotels was especially symbiotic; on a big race day “more than 10,000 people would crowd the verandas and walks” of the Manhattan Beach Hotel alone, “either to celebrate their winnings or to dissipate regret for their losses.” This vortex of leisure and recreation soon transformed southernmost Brooklyn into America’s paramount playground—or, as the Brooklyn Eagle put it with characteristic restraint in 1880, the “grandest watering place on the face of the earth.”5

Warren R. Walker, “At the Steeplechase,” 1902, which the songwriter dedicated to George C. Tilyou. Music Division, The New York Public Library.

William Engeman brought racing to the New York masses. Engeman was a colorful character, born in New York City in 1841 to German immigrant parents. As a teenager he worked as a newsboy and shipwright before striking out for the West, where he crewed a Mississippi lumber raft, brokered cattle in Texas, led wagon trains over the Sierra as a government scout (befriending Buffalo Bill Cody along the way), and sold mules to the Union army during the Civil War. He returned to New York in 1868 a rich man, opening a restaurant in downtown Brooklyn followed by the Ocean Hotel in Coney Island, complete with a pier—Coney’s first—to receive excursion boats from Manhattan. It was as a guest at the Ocean that Austin Corbin was inspired to build the Manhattan Beach Hotel on a site just east. Not to be outdone, Engeman erected a vast bathing pavilion the very next year, aiming to exploit the new popularity of saltwater bathing among the city’s middle classes. Drawing on his Mississippi experience—and having observed how “the sad waves hurled all sorts of debris on the beach”—Engeman floated lumber from Gowanus Canal on old Erie barges, cutting them loose on an incoming tide. The waves dashed the boats to pieces, but the payload washed up on his beach right where it was needed. Engeman’s stick-built palace, four hundred feet long with accommodations for twelve hundred bathers, was begun on May 9, 1878, and completed a mere seven weeks later.6

Engeman later sold half his ocean property to a group of investors who erected there Brooklyn’s second great beachfront resort, the Brighton Beach Hotel (Corbin would build the last of the trio in 1880, the grand, Moorish-themed Oriental Hotel). Three stories high with 174 rooms, the Brighton Beach boasted flush toilets and a sewage system with tanks to filter wastewater before it was discharged into Coney Island Creek—ostensibly “free from any offensive odor, and pure.” The settled-out solid waste was periodically removed in blocks and sold to local farmers as manure. In time, beach erosion threatened to wash the immense complex into the sea, and in April 1888 the entire structure—all six thousand tons of timber and trim—was jacked up, set on rails, and tugged six hundred feet inland by a team of locomotives. “Simultaneously six throttles were thrown open—first gradually, then to their full,” reported a New York World correspondent; “The music of the guy ropes and tackle was weird and Wagnerian; then the tug of war began.” The great throng of spectators held its collective breath as the locomotives strained against the load. “For a moment, and a moment only, they tugged in vain, their immense drive wheels revolved with perceptible swiftness; then, as if with a mighty effort, they forged ahead.” It was the largest building moved in nineteenth-century America, and without breaking a single window pane or mirror.7

Engeman, too, moved inland, trading surf for turf and founding—in 1879—the Brighton Beach Racing Association. On a large plot just north of the Ocean Hotel that year he unveiled his greatest project yet—a racetrack known as the Brighton Beach Fair Grounds. The track was built even faster than his bathhouse; an army of some five hundred construction workers completed the project in a mere thirty days. But Engeman clearly had his doubts about the viability of the venture, and “built the grandstand,” writes sports historian Steven Riess, “so it could easily be converted into a row of cottages if his investment failed.” Of one thing he was sure—getting to the track would be easy; for no fewer than six railways, including predecessors of the Culver, Sea Beach, and Brighton lines—today’s F, N, and B/Q trains—connected it to the rest of Brooklyn and New York, as did Ocean Parkway and an assortment of steamboats and ferries. While not as posh as Jerome Park—then New York City’s premier track, home of the American Jockey Club—Brighton Beach had a faster and more spacious course (the Jerome track had an odd goggle shape). Its simple twin grandstands could accommodate thirteen thousand spectators, with room for an additional thirty thousand standees.8

The 174-room Brighton Beach Hotel, set on twenty railroad tracks, is pulled from the shore by a team of locomotives, April 1888. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In short order, Brighton Beach was running more events than any other track in the nation, earning Engeman well over $100,000 a year. His trick was simply to service a neglected market of working-class bettors and racing enthusiasts—something most other tracks, especially Jerome Park, eschewed. Brighton Beach was the “-people’s track,” and from the start it drew a large and remarkably polyglot crowd. A snarky Detroit Journal correspondent described it as made up of “Negro stablemen, Irish saloonkeepers, French barbers, German tailors, Scandinavian boarding house runners . . . canal boatmen, waiters, hackmen, bootblacks [and] English visitors.” The teeming crowd was peppered with “crooks of every variety” and full of men “elbowing their way in and out, smoking cheap cigars, drinking quantities of beer and betting all they are worth on every race.” There were women too. These were hardly the posh ladies of Jerome Park, but rather “a strange lot” opined the Journal reporter, now putting his very life at risk; “hard-featured, coarse and repulsive creatures dressed in gorgeous red or blue satin gowns, with their slim fingers loaded with showy rings, and their hair bleached to a sickening shade of yellow.”9 The New York Times found the plebian crowd’s enthusiasm for gambling more abhorrent than the women. A sanctimonious 1885 editorial described Brighton Beach as “the pesthole of race-track gambling in this neighborhood.” There, “the clerks and cashiers and office boys of the city are drawn into the fever of betting on races, and many a petty theft and serious embezzlement may be traced directly to the demoralizing influence of that track and its evil surroundings.”10 Nor was the populist attraction a particularly accommodating place for horses. In its inaugural season, an average of two horses were killed weekly in accidents at Brighton Beach, prompting a sobriquet for the course—the Coney Island Slaughter House. The Times called it “The Track to Kill a Horse.” In a five-day period in September 1879, three steeds had to be put down after breaking legs and shoulder bones at the track—including an old campaigner named Egypt whose injury was so sickening that “the most hardened in the crowd . . . turned away.” A police officer put the unfortunate beast out of its misery, firing “a friendly bullet into his brain.”11

But the racing elite also had its eyes on deep-south Brooklyn, especially as one of its brightest lights, Leonard W. Jerome, lost management control of the Bronx track he had built and named. Just a week after the Brighton Beach Fair Grounds opened, Jerome and a group of youthful, fabulously wealthy racing enthusiasts founded the Coney Island Jockey Club. In addition to Jerome—the “King of Wall Street” and grandfather of a five-year-old boy named Winston Churchill—the investors included August Belmont, Jr., financier and founder of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company; railroad magnate William K. Vanderbilt; Alexander Cassatt, soon to be president of the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad; tobacco heir Pierre Lorillard IV; and Wall Street stock mogul James R. Keene. This was a gathering of souls with the power and money to quite literally move mountains, and they meant to build a temple to their sport that would be the envy of the racing world. When Engeman reneged on his offer to sell them his Brighton Beach track, Jerome built a new one instead on a forested 112-acre site nearby—between Ocean Parkway and Gerritsen Creek. In late January 1880 an army of workers, led by Jerome’s brother Lawrence, began clearing the old-growth hickory, oak, and elm. “Hundreds of trees were felled,” reported the Eagle, “hundreds of stumps . . . drawn from the ground and burned.” The dark woods were rent open to the sunlight, looking “as if Aladdin had been around with his genii and his wonderful lamp.”12

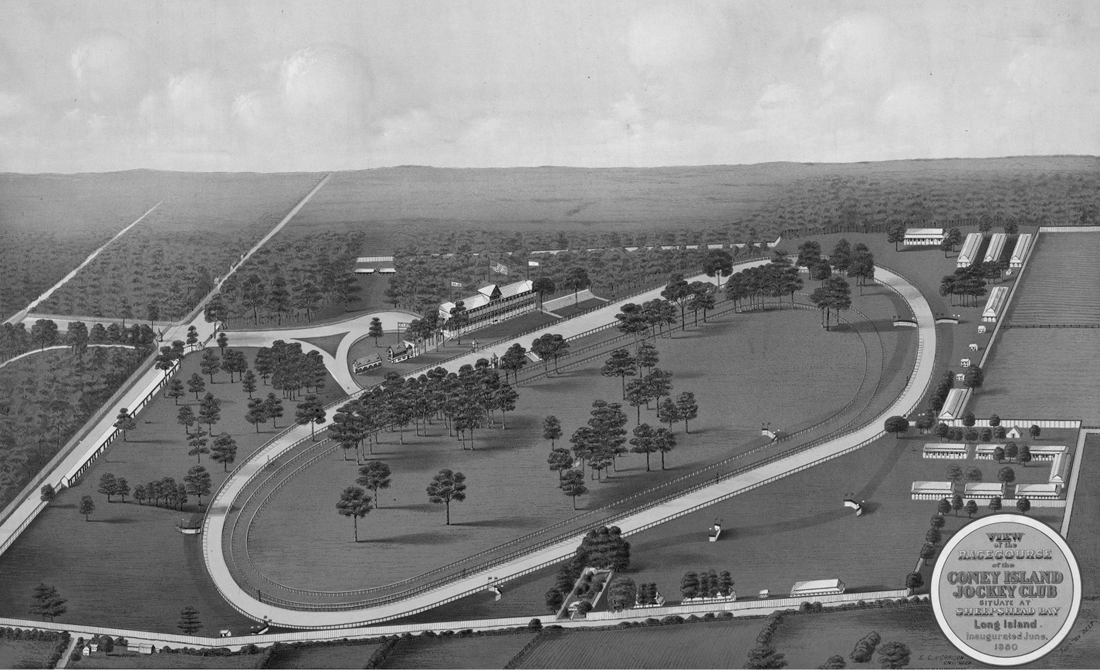

The Coney Island Jockey Club’s Sheepshead Bay Racetrack opened to the public in early June 1880. Built on the deep sandy loam of Brooklyn’s outwash plain, it was “the pearl of New York racing” and the best track yet in the United States. The course was fast, laid out as “a splendid ellipse, so constructed as to give a long and easy sweep on the turns,” and a vast improvement over the contorted Jerome Park course. The new grandstand was a spectacle in itself, two stories tall and made of brick and iron, with a large central pavilion and lesser ones at each end. It gave patrons a broad view of the Atlantic while shielding them from the glare of the sun during races. And Sheepshead Bay only got better with time, its wealthy owners plowing nearly all profits back into the increasingly large and lavish facility. From the initial 112 acres, the complex expanded to 200 acres in 1884, when the main track was extended to a mile and a furlong—the longest in North America. By 1902 the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack had grown to 500 acres. It was hailed the “American Ascot,” and considered the only course in the United States equal to the celebrated tracks of England and Europe—Newmarket, Ascot, Longchamp in Paris, Frendenauer in Vienna—turf itself soon vanquished by the Coney Island Jockey Club when Lorillard’s Iroquois won two major British races and Keene’s Foxhall won the Grand Prix de Paris in 1881. To the somewhat biased Brooklyn Eagle, Sheepshead Bay eclipsed “anything of its kind in the United States” and was very likely “the finest race course of the world.” It was also the nation’s richest racetrack, grossing more than any other New York course at the turn of the century and in 1907 becoming the first in America to rake in over $1 million.13

View of the racecourse of the Coney Island Jockey Club, Hatch Lithographic Company, 1880. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

By the 1900s, major race days at Sheepshead Bay attracted crowds of fifty thousand people, far more than what Ebbets Field would see a generation later. It was an upmarket crowd, with the price of grandstand admission more than double that at Brighton Beach. The new track became a favorite with society women, who often attended in parties—dressed to the nines and joyously unaccompanied by men. They appreciated the splendor of Sheepshead Bay, a track so exquisite that “no such place as these beautiful grounds,” opined the racing periodical Spirit of the Times, “were ever even dreamed of by Ponce De Leon.” The women also liked the order and discipline of the crowd, a quality attributed to the presence of “argus-eyed detectives” from the fabled Pinkerton agency. In 1884 the Coney Island Jockey Club inaugurated the Suburban Handicap, the first of several annual races for which Sheepshead Bay would become renowned. Run in early June, the “Great Suburban” marked the opening of the Sheepshead Bay racing season. It was a major event on the New York society calendar, drawing scores of Gotham’s power brokers and “best families” to the wilds of Brooklyn, many of whom delayed their summer leave-taking to the mountains or sea until the race was run. The Suburban even set style standards for the city. “The costumes on the grand stand,” observed the Tribune, “create the particular edicts of fashion which are to be followed by the elect for the season.”14

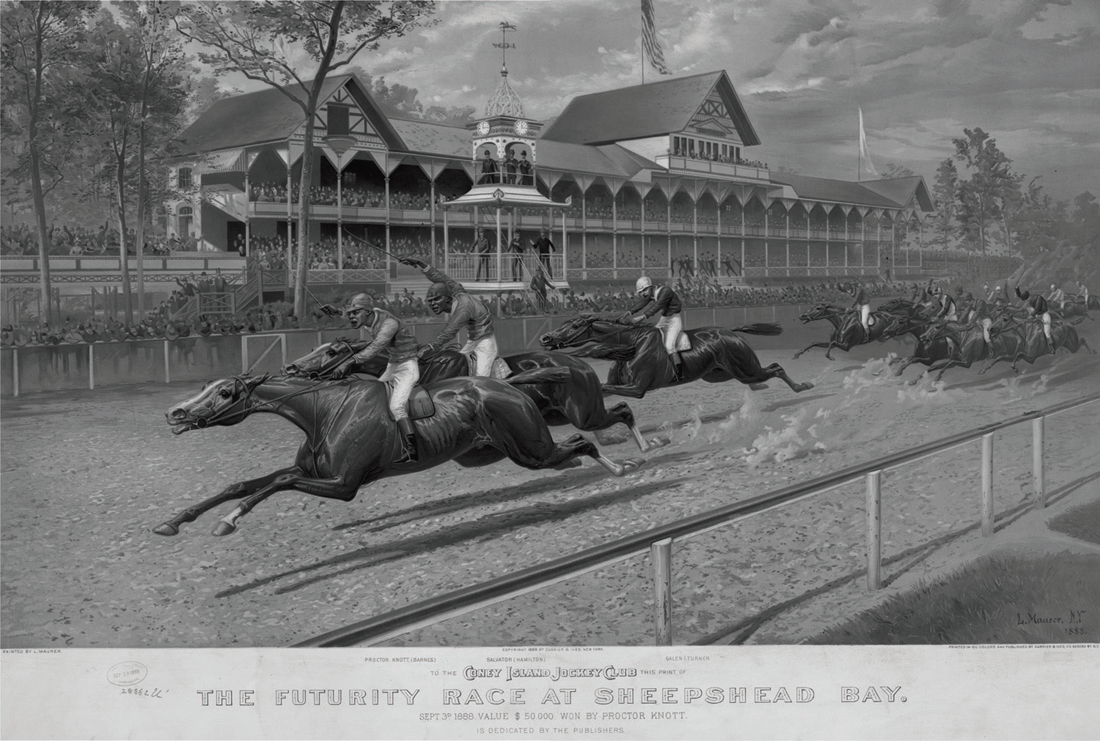

The Futurity Stakes, first run on Labor Day 1888, was the highlight of autumn at Sheepshead Bay and heralded the end of racing season. So named because the competing two-year-old steeds were nominated at birth or even before, the Futurity was the biggest prize in American sports and awarded some of the largest racing purses of the nineteeenth century. The inaugural Futurity broke all club attendance records, thronged by a “surging, noisy, good-natured” crowd that hailed from every quarter of the city. The wellborn mixed with the low, men who ran Wall Street with those who swept it. “Millionaires and beggars, touts and dudes,” observed the New York Times, were all briefly equalized by the thunder of hooves. There were drawling horsemen from the “great breeding States” of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee on hand to see the horses they bred compete. And there were women, too, the Times estimating as much as one-quarter of the crowd. The doyennes of New York society basked in the gaze of men bewitched and bothered by their silk-and-satin finery, their faces “bronzed and burned” from the summer’s sojourns. No one thought to count the heads, but catering records reveal that a great repast was consumed. The feast included 500 gallons of clam chowder, 12,000 pounds of lobster, 600 soft-shell crabs, 25 spring lambs and 50 racks of ribs, 960 chickens and 500 squabs—all that and the kitchen still fell short of demand. From the bars and taps, meanwhile, poured forth a great river of drink: 250 kegs of lager, 380 cases of champagne, 5 barrels and 40 cases of whiskey, 30 barrels of ginger ale, and 600 boxes of soda water and sarsaparilla. The first Futurity was worth almost $40,900, and the 1890 race had a purse of nearly $70,000, prompting the Los Angeles Herald to call it “the most valuable event run for in this country . . . probably in the world.” The Sheepshead Bay Racetrack, along with those at Brighton Beach and Gravesend, made Brooklyn the racing capital of the United States for a generation. This is how Brooklyn gave New York City its greatest nickname. If the Old South was the wellspring of thoroughbred racing, New York City was its biggest trophy; or, as a long-forgotten African American stable hand once put it, the “big apple.” The reference, invoking a favorite treat of horses, was overheard by a turf scribe named John J. FitzGerald, whose Morning Telegraph racing column eventually made the “Big Apple” a beloved moniker for New York City, even if its very core—then as now—was Brooklyn.15

Of course, all this play was also work. An immense labor force was needed to run the great hotels, bathing pavilions, restaurants, beer gardens, dance halls, saloons, and betting parlors. Thousands of waiters, cooks, cleaners, footmen, drivers, and musicians found employment between surf and turf, especially in summer months, not to mention the vast army of card sharks, whores, and hustlers that preyed on the summer crowds. The Manhattan Beach Hotel alone employed some five hundred workers at peak season. The racetracks relied on a particularly skilled and specialized array of workers—grooms, trainers, farriers, hotwalkers, stable hands, and stall cleaners. With each new racetrack the population of the surrounding areas swelled; Gravesend alone grew from fewer than twenty-two hundred residents in 1870 to nearly seven thousand in 1890. The Sheepshead Bay track had a race-season worker population of more than a thousand by 1902. Many lived on-site and found employment among the sixty-odd stables in and around the complex. These were not city people, for the most part, but men and women from the horse country of the American South—Virginia and the Carolinas, Kentucky, Tennessee. And unlike the majority of others employed around Coney Island, most were African American. They were former slaves and the sons and daughters of slaves. Far from Harlem, the heart of African American life in New York City at the time, they formed an especially tight community of their own, turning a handful of streets in Gravesend and Sheepshead Bay into a little Southern town. It was a town full of soul, but had no place to sing or pray. That changed in 1899, when a black Virginian named Maria J. Fisher appealed to William Engeman’s son and heir for a parcel of land nearby on which to erect a house of worship. Fisher made a living selling baked goods at the Brighton Beach track, and her request moved the Engeman family to donate a pair of parcels on East Fifteenth Street. There Mother Fisher erected what would become the soul of Sheepshead Bay’s African American community. For a builder she had no choice but to hire the kid brother of notorious John Y. McKane, a ward boss who ran Gravesend like a feudal estate. The Concord Baptist Church on Duffield Street in downtown Brooklyn, founded by abolitionists and still one of the foremost African American congregations in New York, sent pastor George O. Dixon to lead the new flock. Thus did Mother Fisher’s First Baptist Church of Sheepshead Bay become the first black house of worship south of Prospect Park, and one of the first and few churches in all New York to have an integrated congregation.16

But African Americans did more than just groom and clean horses; they also rode them—and fast. Long before the Civil War, black jockeys gained renown for their skill and daring in front of audiences both black and white, from New Orleans to Virginia. As the war ended thoroughbred racing throughout much of the Deep South, the sport retreated to the bluegrass country of Kentucky, then occupied by federal troops. Kentucky became the epicenter of thoroughbred racing and breeding in the United States, and by the 1880s its horses and jockeys—many of whom were African American—were winning on tracks up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Black jockeys from the Bluegrass State dominated the thoroughbred scene for a generation. They helped usher in the golden age of racing in America, the nation’s first great spectator sport. Racing drew far larger crowds at the time than even baseball, and the highest-paid athlete in the United States in the 1870s was an African American jockey from Lexington named Ike Murphy. At the first Kentucky Derby in 1875, nearly all the jockeys at the starting gate were African American, and black riders won more than half of the first twenty-eight derbies. Murphy himself won the Kentucky Derby three times—in 1884, 1890, and 1891—and was earning $20,000 a year a mere decade after Emancipation. The winner of the Coney Island Jockey Club’s inaugural Futurity in 1888—one of the greatest races of the nineteenth century—was jockeyed by an African American named Shelby “Pike” Barnes, while the second-place horse was under the command of another black jockey, Tony Hamilton. So celebrated was the race that Currier and Ives issued a print of Barnes and Hamilton charging toward the finish line, possibly the earliest depiction of black athletes in American media.17

Mother Maria J. Fisher with Fanny Brown and Bertha Greene, 1927. Collection of Donald Brown.

Of course, the prominent role of African Americans in racing was hardly due to some lost gene of racial tolerance in society at large. Blacks became illustrious jockeys because they were highly skilled athletes, but also because the job of jockey-ing defaulted to them. The prevailing belief for many years was that thoroughbred horses effectively “rode themselves,” and that the jockey was just along for the ride. In other words, the jockey didn’t matter. Jockeying was also dangerous, and like most dangerous work in nineteenth-century America, it was left for blacks to do. As David Wiggins has argued, jockeying was known as “nigger work,” which was more than enough to keep whites away. Not until well after the Civil War, as racing became more sophisticated, was the jockey’s vital role in a race recognized. The rising stock value of jockeying soon made it a well-paid line of work; and in no time black riders were battling to stay in the saddle. A year after being feted for winning the lucrative 1890 Futurity, Tony Hamilton was vilified as an opium-addled drunk and a “muckle-headed negro.” The best black jockeys held their own, for a time. Then came the Panic of 1893 and the series of recessions it triggered. “As the economy collapsed and American racing shrank,” writes Ed Hotaling, “the fight for the dwindling number of jobs turned more vicious, and blacks were pushed out at an accelerated rate.”18

By the turn of the nineteenth century, African American jockeys had effectively been purged from a sport they helped make a national pastime. As the New York Times observed, “the decline of the negro jockey has been so apparent since the season of 1900 opened that even the casual racegoer has had an opportunity to comment upon it.” While many racing fans assumed that black jockeys had disappeared simply because “old-time favorites of African blood had outgrown their skill,” the real reason was a deliberate campaign to shut them out. White riders have simply “drawn the color line,” reasoned the Times, “and wish to free the jockeys’ room from the presence of the blacks.” Track gossip suggested that the jockeys were not alone in this chicanery—that they were “upheld and advised” by influential turfmen and horse owners, possibly even the powerful Jockey Club itself, formed in 1894 to set national standards for the sport. If a stable or owner ran a black jockey in defiance of the unspoken ban, “concerted action by all the white boys” would assure the defeat of his horse. This often involved violence. As Charles B. Parmer writes, white jockeys “literally ran the black boys off the tracks.” Typically, they would surround a black rider and force him to slow down and lose a race, or gang up against him on the rails, where he could be lashed with a whip and even thrown off his mount. The last great black American jockey was Jimmy Winkfield. “Wink,” as he was known, won the Kentucky Derby in 1901 and 1902, but left the country after jumping contract at the rain-soaked 1903 Futurity. The prominent stable owner he double-crossed vowed at Sheepshead Bay that Wink would never ride again in the United States. The Lexington, Kentucky, native left for Europe soon after and by the next spring was in czarist Russia, home to a third of the world’s equine population at the time. Before long, the self-exiled black American was winning races in Budapest, Hamburg, Vienna, Warsaw, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. Wink became the toast of Russia, gaining celebrity and wealth until the Bolshevik Revolution forced him to seek refuge in France. He returned to the United States when the Nazis seized his stables, finding work on a WPA road gang. He returned to France after the war, and stayed the rest of his life.19

By the time Winkfield left for Russia, American racing itself was increasingly under siege, subjected to a purge that threatened not only jockeys but the entire racing establishment in New York State. The target was not horse racing per se, but betting on the outcome of races, a ubiquitous feature of racing since the earliest days of the sport. Gambling was the purr in the race-day cat, and a track without betting was like a bar without drinks. In due time both fell into the gun sights of moral reformers, with consequences as unfortunate as they were unforeseen. Oddly, organized efforts to abolish horse-race gambling in the United States began with the hotly contested 1876 presidential race between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden, in which immense sums were wagered on the vote. Betting on elections was common at the time, but because the outcome of the Hayes-Tilden race was not settled for months, it played havoc with the gambling market. This led the next session of the New York State Legislature to ban “pool-selling,” collecting bets in a common fund to be divided among the winners. The result was the Anti–Pool Room Law of 1877. Like the temperance movement that led to the Eighteenth Amendment and Prohibition, the Anti-Pool Law was championed by progressive elites, clergymen, and establishment institutions like the New York Times, a strident advocate of “public morals and public decency.”20

Predictably, the new law slashed attendance at racecourses—Jerome Park, especially, where turnout for the 1877 season was the lowest in its history. But it was unevenly enforced at tracks and off. In Saratoga the new regulations were honored mostly in the breach, and of course any ban in New York was a great boon for New Jersey, where Hoboken’s notorious poolrooms were especially busy taking bets on seemingly any competitive event. Even in New York City, poolrooms downtown and in “Gambler’s Paradise” near Madison Square continued with only occasional, well-announced raids by reluctant police. With the perpetual threat of a real crackdown looming and tired of losing millions to outside wagering, the American and Coney Island Jockey clubs lobbied hard for a law that would allow betting at tracks but not off. The result was the Ives Act of 1887, which permitted gambling only at authorized tracks between May and October; anywhere else, pool selling or bookmaking was a felony. But shielded by Tammany Hall and allies in the police force and local courts, the poolrooms continued to flourish, despite increased raids by police and Pinkerton agents hired by racetracks. In 1899 a vast poolroom trust was uncovered that implicated the city’s top cop, William “Big Bill” Devery, the man who later helped bring the Yankees to New York. Even the city’s mayor at the time, Robert Van Wyck, was in on it.21

The futurity race at Sheepshead Bay (1888), Currier & Ives, 1889. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Given the severe moral tone of America in the late nineteenth century, it was perhaps inevitable that an outright ban on horse-race gambling, on course or off, would eventually come. To crusaders like mutton-chopped Anthony Comstock—founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and self-proclaimed “weeder in God’s garden”—gambling in any form imperiled the character and well-being of young, working-class men, the backbone of urban industrial society. A ban on wagering, they argued, was for the good of both hearth and nation. Many Americans agreed. In 1893 racetrack gambling was criminalized in New Jersey, effectively banishing racing from the Garden State for fifty years. In Chicago, the Washington Park and Hawthorne tracks closed by 1896, victims of an antigambling campaign led by Mayor Hempstead Washburne. Though both would later open again, racing was effectively banned statewide in Illinois in 1905. That same year racetrack gambling was criminalized in Missouri by Governor “Holy Joe” Folk, closing tracks in St. Louis and Kansas City and spurring the rise of baseball as the dominant spectator sport. Nationwide, antigambling legislation devastated the thoroughbred racing industry; of the 314 tracks in the United States in 1897, only 20 were still operating by 1908.22

That year the bell tolled, too, for the turfmen of New York and Kings County. Until then, Brooklyn had repelled the best efforts of reformers to end gambling there. Unlike the patrician New York Times, its paper of record—the Brooklyn Eagle—initially supported racetrack betting, arguing that grown men “ought to be free to amuse themselves in any way they see fit,” so long as they did not hurt others. Graves-end’s notorious political boss, John McKane, had only tepid interest in enforcing New York gambling laws at the three tracks in his jurisdiction. The tracks themselves applied all manner of creative maneuvering to circumvent gambling laws, leading police and prosecutors in a great game of cat and mouse. In 1885, for example, the Coney Island Jockey Club introduced a scheme in which punters made a monetary “contribution” to owners of the finest, fastest horses; the cash was then pooled and divided among the winners as before. But even tough and scrappy Brooklyn and its trio of tracks proved no match for a crusading constitutionalist from the Adirondacks named Charles Evans Hughes. Born in Glens Falls in 1862, Hughes studied law at Columbia and, after a decade of practice in New York, joined the Cornell law faculty at the tender age of twenty-nine. In 1906 he ran as a Republican for the governorship of New York State, defeating publisher William Randolph Hearst on a platform of progressive social reform. As New York’s chief executive, he pushed for voting reform and workmen’s compensation, passed legislation to limit campaign contributions and increase the powers of the state’s public service commissions, and won passage of the Moreland Act, which armed his office to investigate any state board or agency. Hughes famously rejected an appeal to commute the death sentence of Chester Gillette, whose 1906 murder of his pregnant lover on an Adirondack lake was fictionalized by Theodore Dreiser in An American Tragedy.23

But the biggest fight of his governorship was against gambling and the racing industry. By any reckoning, it should not have been a struggle at all. In 1895 New York voters had amended the state constitution to include an all-out ban on “pool selling, bookmaking, or any other kind of gambling.” But a loophole had been created, largely at the behest of the state’s powerful, politically connected racing interests. This was the Percy-Gray Law, which created a state racing commission—the first in American sports—but effectively neutered the constitutional prohibition on gambling by threatening nothing more than a wrist-slap for most track violations. The only penalty for placing a bet was forfeiture of the wagered amount, to be recovered through civil action, and so long as there was no written record of the bet—no “exchange, delivery or transfer of a record, registry, memorandum, token, paper, or document of any kind”—criminal penalties could not be imposed. Within months of taking office, Governor Hughes charged aides to study the constitutionality of Percy-Gray, and in January 1908 introduced a package of antigambling legislation to impose criminal penalties—including stiff prison sentences—for gambling on or off the track. The legislation was named for the two Republicans who introduced it on the governor’s behalf, Senator George Bliss Agnew and Assemblyman Merwin K. Hart. Hughes then launched a campaign to get the legislation passed, backed by a broad coalition of church and civic groups and the Citizens’ Anti–Race Track Gambling League. Even the seventy-thousand-member Grange lent its weight, persuaded by a $250,000 appropriation to state agricultural societies that Hughes had cleverly written into the bill. The racing crowd fought back mightily. Jockey clubs and bookmakers ponied up $500,000 in secret funds to defeat the bill. Leading turfmen—Whitney, Keene, Belmont—traveled to Albany to testify against Agnew-Hart, arguing that an industry employing thousands would be destroyed if the bill were approved. After months of acrimonious debate, the legislation passed easily in the assembly but was defeated by a razor’s margin in the senate.24

Charles Evans Hughes walking to his office from Union Station, Washington, DC, c. 1913. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Hughes was not finished, however. But before introducing his legislation again, he called a special election to fill a vacant senate seat he knew would be won by a Republican. With the narrowest of margins now his, he called the legislators back into session. The Agnew-Hart bill again passed the assembly and came to the senate floor on June 10. Moments before the vote was called, legislators were stunned to see the chamber doors open and Brooklyn senator Otto G. Foelker wheeled, semi-conscious, to his desk by two men. Foelker had just undergone surgery for appendicitis and was roused out of bed to make the vote, against the pleas of his wife and doctor. Hughes had ordered an express train from New York to stop specifically for him at Staatsburg, where he was recuperating. Foelker was so ill he collapsed upon arrival at Albany. But he cast the deciding vote all the same, delivering a great victory for Hughes, who lauded Foelker’s actions as “most heroic and worthy of the same praise that we give to distinguished service on the battlefield.” Boston minister Adolf A. Berle of the Shawmut Congregational Church was more effusive. “What a spectacle is this for Americans!” he gushed; “A poor son of Germany, an immigrant . . . a baker’s apprentice, who by hard work and self-denial gains an education and place in the state government, and who while the money princes of New York and the whole race track fraternity of gamblers and corrupters hold out prizes . . . risks life and all that life means to be carried to the state capitol to help save the honor of a sovereign state and maintain the majesty of the law.”25

Foelker probably cringed at this eruption of purple prose. As a Brooklyn resident—he lived on Bedford Avenue in today’s Clinton Hill—he certainly had reason to steer clear of Coney Island for a while. For nowhere was the impact of the new antigambling legislation more immediate or devastating than at Brooklyn’s trinity of racetracks. When the law went into effect on June 12, 1908, it wasn’t clear at first how strenuously it would be enforced, or whether there were loopholes to exploit. Because the law was aimed at professional gamblers and required written record of a wager for conviction, oral bets and private betting by individuals were allowed, so long as these used credit rather than cash. Gamblers, amateur and professional, were certainly present when the various tracks opened for the season, but oral betting proved cumbersome; what wagering took place was furtive and the atmosphere generally tense and edgy. The city’s ironfisted police commissioner, Theodore A. Bingham, instructed his men to break up groups of two or more persons, even if they were just talking about the weather. On opening day at Sheepshead Bay on June 19, the Coney Island Jockey Club obtained an injunction to keep Bingham from harassing its elite patrons. He sent an army of three hundred men to hover menacingly nonetheless, worrying the punters like wolves watching sheep. Once the bookmakers learned of Agnew-Hart’s permeability, they “took corresponding liberty,” observed the Times, “but with police keenly alert for offenses that would come under the interpretation of the law.”26

Of course, the constant threat of arrest spoiled the festive air of meets and ravaged track attendance. Race enthusiasts who liked to pepper the day’s outing with a harmless bet or two now risked arrest, while professional bookmakers simply stayed in town to ply their trade under the table. Track crowds were substantial enough in the spring of 1908, but that autumn it became clear that Agnew-Hart was taking a toll. William A. Engeman, Jr., who was arrested in July for letting bookies operate at Brighton Beach, canceled outright the fall meet and put the entire property on the market the very next month. Sheepshead Bay was drawing only a thousand or so spectators to races by the end of September. The Coney Island Jockey Club posted a staggering loss of $350,000 that season, when normally it would turn a profit of $400,000 from just its Suburban and Futurity races. Then, in early 1910, a suite of legislation known as the Agnew-Perkins bills passed in Albany to tighten the screws on racetrack gambling, closing the oral betting loophole and—in an especially draconian move—making track management and trustees personally responsible for bookmaking on the premises. This kicked the threat of arrest and prison upstairs into the executive suite. Now the industry had its back against the wall.27

On Independence Day that year, just weeks after Agnew-Perkins became law, a surprisingly large crowd turned out for the Lawrence Realization Stakes, closing event of the Coney Island Jockey Club’s season. It was a cool summer day and the gala atmosphere in the grandstands “put the regulars in mind of conditions four or five years ago,” before crusader Hughes clouded race-day skies. In the steeplechase feature, a horse named Bird of Flight hit the fourth jump and fell to the track crumpled and twitching, so badly injured that it had to be shot in full view of the crowd. It was an omen of sorts, for that day would be the very last of horse racing at Sheepshead Bay—crown jewel of New York tracks, the plumpest and most succulent big apple of all. By early September 1910 all three of Brooklyn’s great thoroughbred courses had closed. They would never open again. The defenders of moral order prevailed, but their victory was a costly one. Thousands of employees lost their jobs. Trades and businesses that provided the racing industry’s vast support infrastructure took a blow, sending shock waves through the state economy. Not even rural New York was immune, as the numerous agricultural societies throughout the state were now deprived of a major revenue stream from a special tax on track profits. With so few affluent New Yorkers trekking to the Brooklyn shore, the area quickly lost its upmarket cachet. One after another, the great seaside hotels closed—the Manhattan Beach in 1911, the Oriental in 1916, with the Brighton Beach lingering until 1924. On the world map of track and turf, a bright American light flickered and went dark; Brooklyn’s brief, bountiful age of bridle leather was over.28

The Brighton Beach Hotel being demolished, July 1924. Photograph by Eugene L. Armbruster. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.