CHAPTER 1

THE NATAL SHORE

There is toward the sea a large piece of low flat land . . .

overflowed at every tide.

—JASPER DANCKAERTS AND PETER SLUYTER, 1679

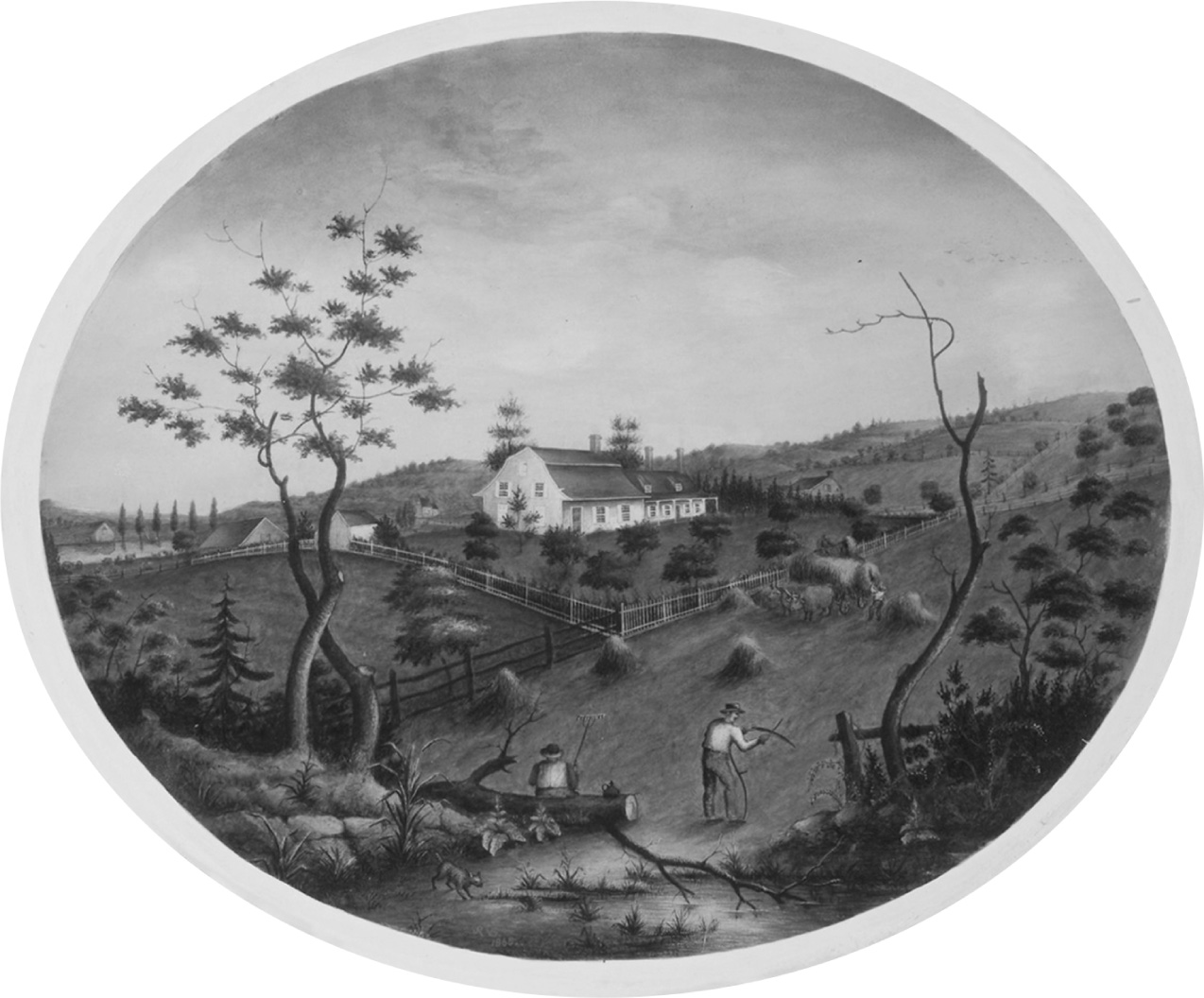

Amidst the leafy quietude of East Thirty-Fifth Street in Marine Park, far from the hipsters or the merchants of twee, there is a spectacle as unique and unlikely as a Hollywood stage set. The Hendrick I. Lott house is one of New York City’s most extraordinary survivors, a virtually unaltered keepsake from Gotham’s distant past that sits among its upstart neighbors like an old cat sleeping in the sun. The house occupies a spacious lot, but it once commanded an empire of earth that swept south and west from Kings Highway to Jamaica Bay. Canted a few degrees off the street grid as if in protest of municipal edict, the Lott house is among the oldest homes in New York and a superlative example of Dutch American vernacular architecture that—unlike most other colonial holdouts in the city—has sat on the same foundation for over two hundred years. Incredibly, the Lott house was occupied by the same family until 1989—the longest tenure of any in New York City history. I remember well its elderly last occupant, Ella Suydam, a librarian at Eramus Hall High School, who would wave to us boys as we gaped, wide-eyed, at the “country house” in the middle of town. Suydam, a neighborhood character who swept her porch in a 1930s fur coat, was—incredibly—the great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Johannes Lott, who built the east section of the house in 1719, the year my favorite childhood book was published, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

The long-rural southern hemisphere of Brooklyn was brought into Gotham’s pale in the 1920s, as the city grew south and east in its most exuberant era of expansion. Municipal water and sewer infrastructure had only just been extended to this part of town—service that, combined with a roaring economy and a ten-year tax holiday, stoked an unprecedented frenzy of residential development. Fields first plowed in the seventeenth century now brought forth a last great crop of mock-Tudor homes. This remarkable metamorphosis—from countryside to cityscape almost overnight (subject of chapter 13)—is well documented thanks to a twenty-six-year-old aviation entrepreneur named Sherman Fairchild, whose fledgling Fairchild Aerial Survey Company had photographed every inch of Manhattan in 1922 with a fast new camera of his own design. The images were tiled together to produce a map twenty inches wide and more than eight feet long. The following year, Fairchild was commissioned by city engineer Arthur S. Tuttle to do the same for all of New York. By the summer of 1924 his camera plane had flown nearly three thousand miles back and forth over the city, snapping some twenty-nine hundred images of the five boroughs from an altitude of ten thousand feet. These were assembled into a great mosaic to produce an eight-by-twelve-foot aerial portrait of the Big Apple—the first comprehensive photographic map of any city in the world. It revealed, among other things, the hungry grid of metropolis about to consume the old Lott farm—Brooklyn’s last rural landscape. Fairchild’s camera planes came not a moment too soon; for the very next year—1925—was the last that Johannes Lott’s rustic spread would be tilled. Sherman Fairchild’s photomosaic thus captured in the wink of a mechanical eye a two-hundred-year-old pastoral realm at the very end of its days.1

The Hendrick I. Lott House, c. 1720. Photograph by Alyssa Loorya, 2017.

Lott was a pioneer, to be sure, but hardly the first European in this vernal corner of the New World. Flatlands had been colonized for close to a century by now, and had been home to Native Americans for untold centuries before that. At the northern boundary of Lott’s land was an old Indian crossroads, the present-day junction of Flatbush Avenue and Kings Highway. Heavily trafficked thoroughfares today, they still roughly follow ancient alignments, which explains why both roads look like random rips in the urban fabric on a map of the city. At the juncture of these trade routes was once the Canarsee Indian settlement of Keskaechqueren or Keskachauge (Keskachoque in “modern Long Island nomenclature”), a principal council site of the tribes of western Long Island and possibly the seat of Penhawitz, a powerful, peaceable sachem and friend of the Dutch. One of several chieftaincies scattered across Long Island at the time of European contact, the Canarsee lived in semipermanent settlements made up of small matrilineal family groups. They drew sustenance from land and water—gathering chestnuts, fishing, hunting, and harvesting shellfish; cultivating maize, beans, pumpkins, and squash. They were part of the Leni Lenape Nation of Algonquian peoples that once occupied much of the northeast coast, and whose place-names—Gowanus, Hackensack, Manhattan, Passaic, Rockaway, Weehawken—are the toponymy of daily life in metropolitan New York.2

Brooklyn’s last rural landscape on the verge of urbanization, 1924. From a citywide photomosaic map produced by the Fairchild Aerial Camera Corporation for city engineer Arthur S. Tuttle. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

Keskachauge was on the edge of a broad expanse known as the “Plains” or the “Great Flats,” which extended north to about where Brooklyn College is today. It was the largest of three such plains in the area that were among the few natural prairies east of the Allegheny Mountains.3 These long-vanished grasslands were surrounded by woods, but treeless except for an occasional ancient oak or pine tree. In places, they were planted to maize by the Canarsee. They were formed in part by the centuries of periodic burning by Native Americans to facilitate travel, clear underbrush for camps and cultivation, kill off ticks and fleas, and increase the forest-edge habitat favored by game animals—turkey, grouse, quail, deer, rabbits.4 We recall these miniature prairies today in the name given this part of Long Island by the English—Flatlands. Something of their character may be gleaned from a description by Timothy Dwight of the larger Hempstead Plain, farther east on Long Island (a tiny fragment of which may still be seen between Nassau Coliseum and the Meadowbrook Parkway). Then serving a grueling term as president of Yale College, Dwight took a series of extended autumn journeys through New York and New England in the 1790s, one of which covered the length of Long Island. Dwight found the Hempstead Plain to be “absolutely barren” in some places, but elsewhere covered by “a long, coarse wild grass” or thinly forested with pine or shrubby oaks (“the most shrivelled and puny that I ever met with”). Except for peninsular intrusions of forest into the plain, the terrain was relieved only by occasional clusters of trees such as the Isle of Pines—which “at a distance,” he noted, “resembles not a little a real island.”5

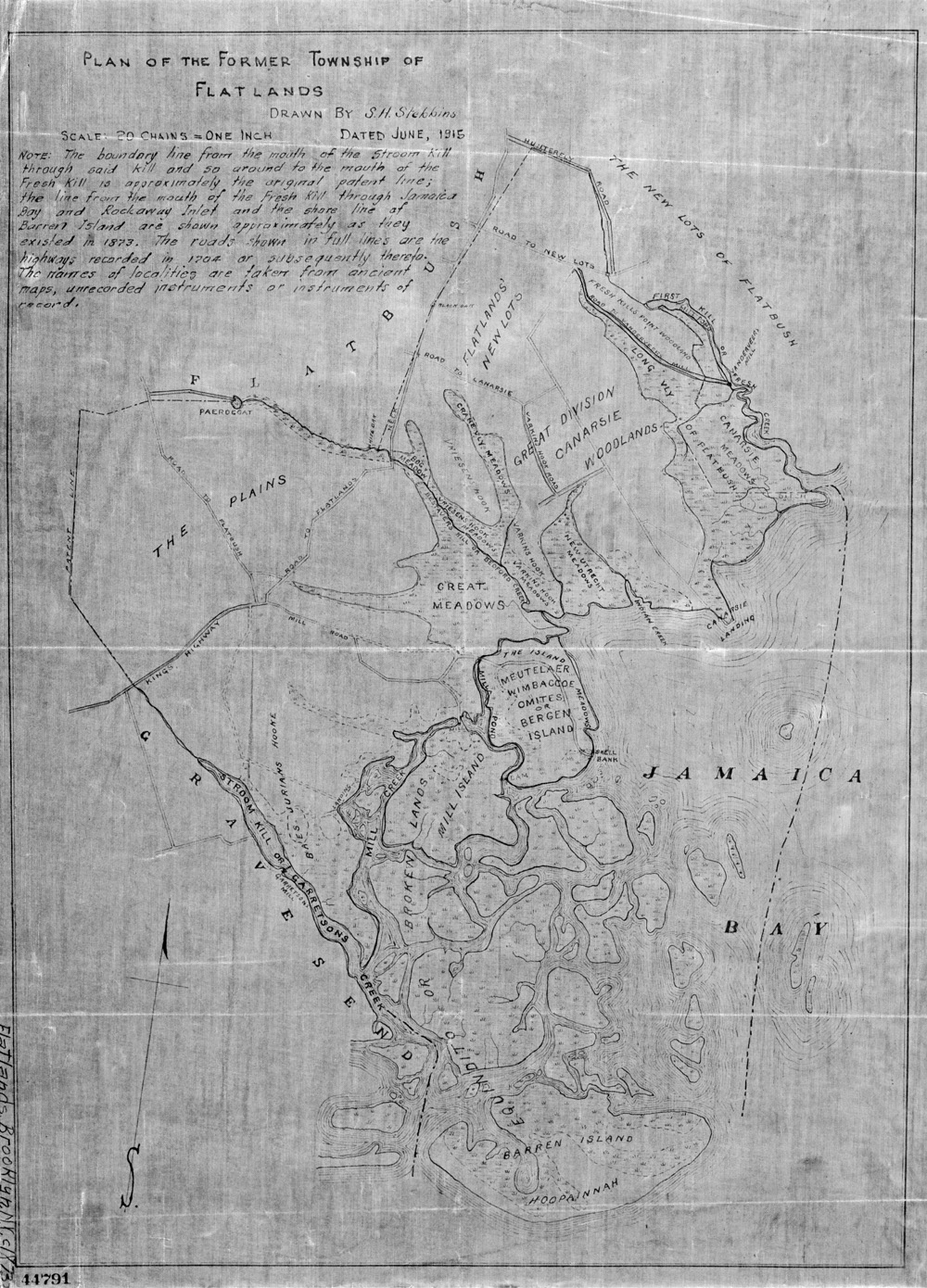

Plan of the former township of Flatlands showing the plains or Great Flats, Baes Jurians Hooke, and the “Stroom Kill or Garretsons Creek.” Drawn in 1873 by S. H. Stebbins using early records. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

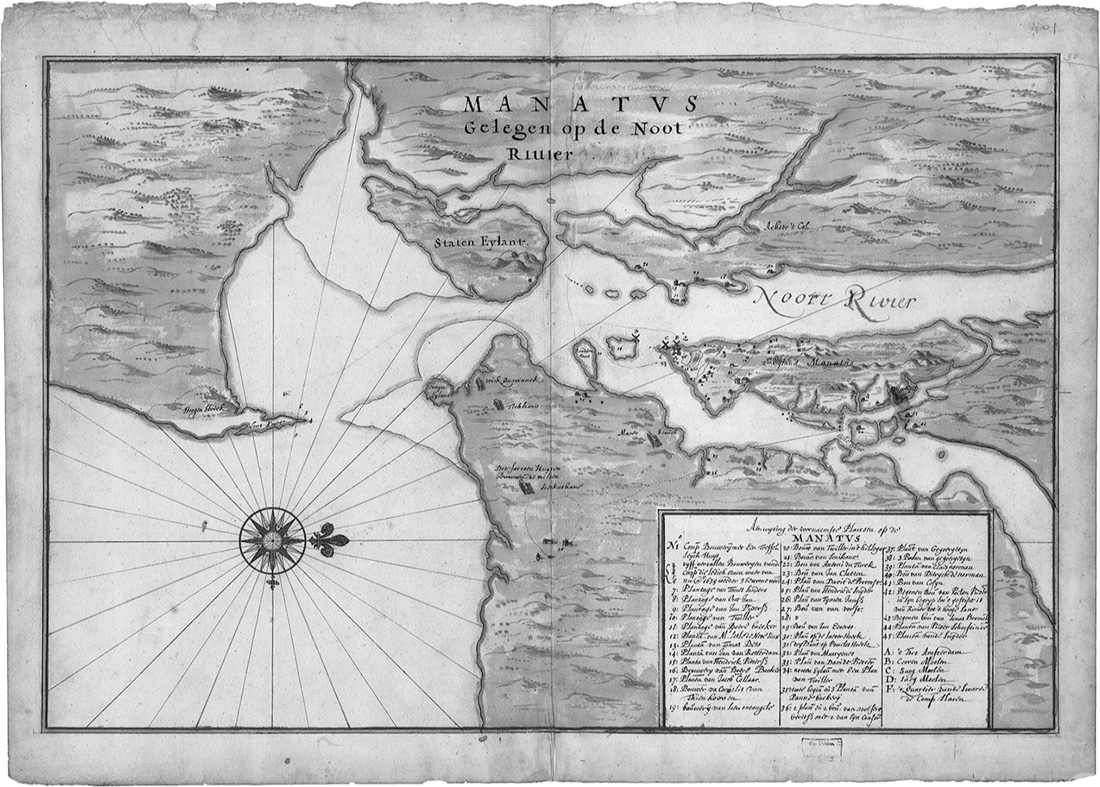

Keskachauge appears on the earliest surviving map of New Netherland—the remarkable Manatus Map of 1639. The document—produced by either the Dutch cartographer Johannes Vingboons or colonial surveyor Andries Hudde—was found hanging on a wall at the Villa Castello near Florence and later moved to Michelangelo’s Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. The nearly identical “Harrisse Copy”—a detail of which is reproduced here—is held by the Library of Congress.6 On the map, Keskachauge is shown just east of “Conyné Eylant,” marked by a longhouse noted as the habitation typical of “de Wilden Keskachaue”—the “savages” of Keskachauge.7 We don’t know what this structure looked like, but it was likely similar to an Indian longhouse several miles to the west at Nieuw Utrecht described in a remarkable document discovered in an Amsterdam bookshop in 1864—a travel journal by two visiting missionaries from Friesland, Jasper Danckaerts and Peter Sluyter. While riding along the marshy shore near today’s Fort Hamilton, the pair heard the sound of pounding, and discovered nearby an elderly Indian woman “beating Turkish beans [maize] out of the pods by means of a stick.”

Manatvs gelegen op de Noot Riuier (Manatus Map), 1639. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

We went from thence to her habitation, where we found the whole troop together, consisting of seven or eight families . . . Their house low and long, about sixty feet long and fourteen or fifteen feet wide. The bottom was earth, the sides and roof were made of reed and the bark of chestnut trees; the posts, or columns, were limbs of trees stuck in the ground, and all fastened together.

The roof ridge of the longhouse was left open half a foot the entire length of the structure, allowing smoke to escape from cooking fires below. These were built “in the middle of the floor,” noted the men, “according to the number of families which live in it, so that from one end to the other each of them boils its own pot, and eats when it likes.” The Keskachauge longhouse was probably located at the headwaters of “a certaine Kill or Creeke coming out of the Sea”—a tidal estuary of Jamaica Bay known as Weywitsprittner to the Indians, the Strome Kill to the Dutch, and Gerritsen Creek today.8

The Strome Kill is Brooklyn’s natal stream. Once extending as far north as Kings Highway, it was the longest of the many tidal inlets that scored the outwash plain above Jamaica Bay, so cleaving the landscape that the Dutch called it breukelen—“the fractured lands.” As Daniel Denton observed in 1670, such “Christal streams” on Long Island’s south shore not only teemed with fish—“Sheeps-heads, Place, Pearch, Trouts, Eels, Turttles”—but ran “so swift, that they purge themselves of such stinking mud and filth” and were thus unlikely to harbor “fevers and other distempers.”9 The cultural history of the Strome Kill may date back some fifteen hundred years, when post–Ice Age sea levels stabilized and the modern coastline of Long Island began to take form. As Frederick Van Wyck speculated in 1924, the tidal estuary “probably contains more undisturbed traces of the Indians than are to be found in any other part of Brooklyn, possibly in any other part of the city of New York.” It was on the western shore of the Strome Kill that a Canarsee Indian village and wampum works known as Shanscomacoke once stood. Evidence of long occupation of this place by Native Americans came to light slowly in the nineteenth century. Farmers found arrowheads on the beach; vast shell banks or “middens” were revealed by tides and erosion. When Avenue U was constructed at the turn of the nineteenth century, human skeletons were unearthed in graves filled with still-sealed oyster shells—meant, perhaps, as sustenance in the afterlife.10

“Ryder’s Pond and Old Cedar,” 1899. This photograph by Daniel Berry Austin was taken from the west bank of Gerritsen Creek below present-day Whitney Avenue. Daniel Berry Austin photograph collection, Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

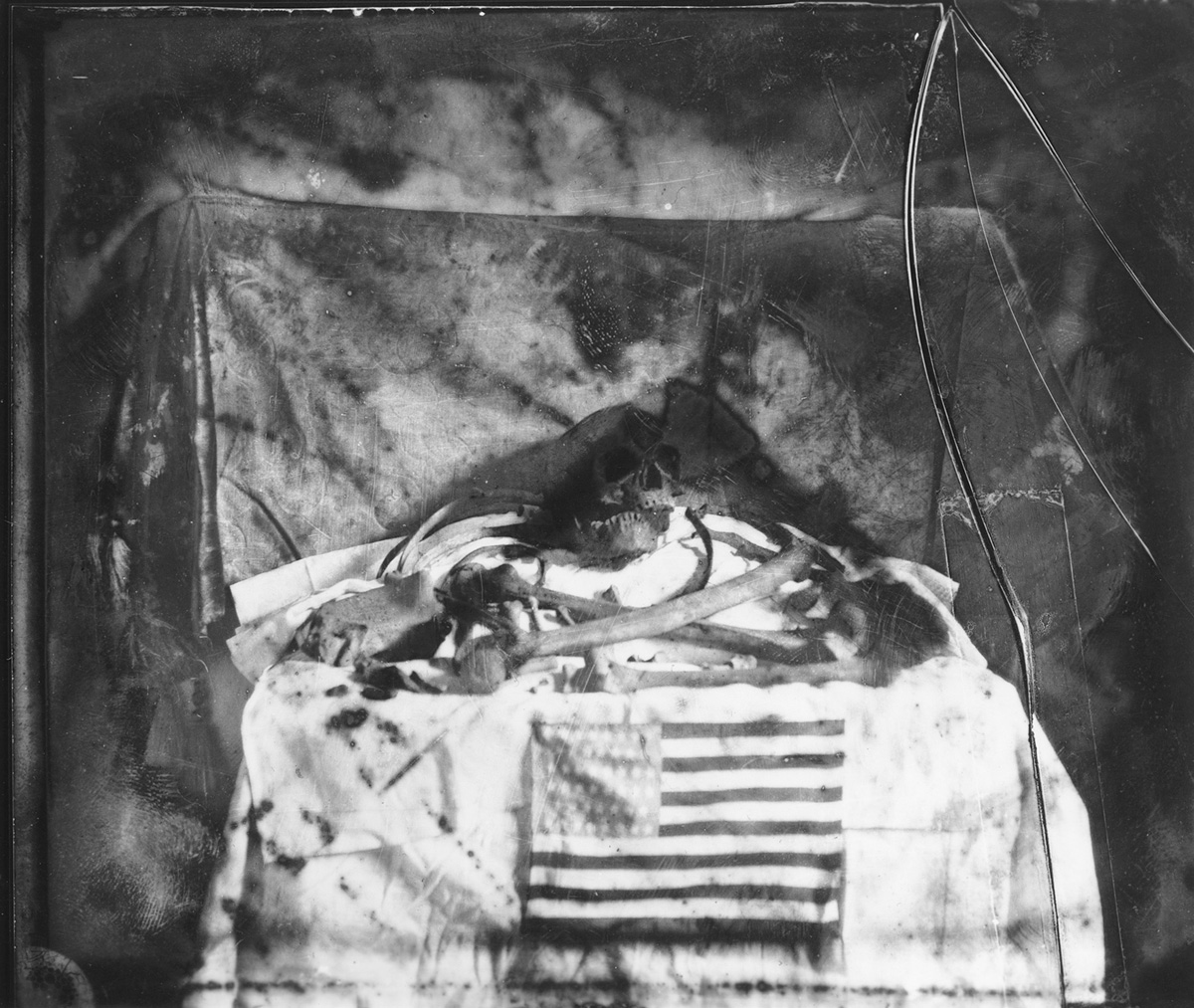

It was around this time that an amateur archaeologist named Daniel Berry Austin began digging at Gerritsen Creek. Austin was an accomplished photographer with a day job at Standard Oil, but his real passion was the indigenous history of Long Island. Equal parts hoarder and scientist, Austin amassed a breathtaking collection of artifacts over his lifetime. He crammed more than ten thousand items into his modest home on East Fourteenth Street in Midwood, some fifteen hundred of which were from sites in Brooklyn alone. This included several skeletons stored—quite literally—in his closet. One of these probably came from the vicinity of Avenue U and Burnett Street, where Austin discovered a dozen graves each spaced thirty-five feet apart from one another. Sometime later, just to the north, Austin and his two young sons stumbled upon perhaps the most extensive prehistoric site ever unearthed in New York City. They dug up hundreds of arrowheads, stone tools, pottery shards, and animal bones later determined to date mostly from the Late Woodland period—a period that ended a thousand years ago. But Austin excavated carelessly, failing to note relative depth or location of artifacts and thus scrambling forever the archaeological record. Still, if not for him, knowledge of Shanscomacoke might have been lost altogether. For in the 1930s, the entire site north of Avenue U was buried under many feet of sand and soil. What remains of this ancient place today lies beneath the ball fields and turf of Marine Park, especially its western half, south of Fillmore Avenue and Junior High School 278. Austin’s hoard was scattered to the winds after he died. Fortunately, some of it passed to a prominent Long Island naturalist named Roy Latham, who later gifted the artifacts to the tiny Southold Indian Museum. They remain there today, across the road from an astronomical observatory named, oddly enough, for the grandniece of Indian fighter George Armstrong Custer.11

Austin was not the only one bewitched by this spectral corner of the city. So, too, was Frederick Van Wyck, a New Yorker of old Dutch stock whose cousin was the bumbling first mayor of Greater New York, Robert A. Van Wyck (whom we’ll meet in chapter 10). A broker by trade, Van Wyck had the time and money to indulge a lifelong passion for history and the arts. Several of his books were illustrated by his wife, Matilda Browne, a landscape painter who had studied with Thomas Moran. Like many men of his generation, Van Wyck was dismayed by the decline of Anglo-Dutch New York and the churning Babel that his city was becoming. Each wave of immigrants from Ellis Island seemed to send him on ever-deeper recovery missions into the past. A man literally out of time, Van Wyck came to dwell “mentally and physically in the New York of a bygone era,” engrossed in the creation narrative of his city and social class—a real-life Diedrich Knickerbocker, narrator of Washington Irving’s satirical History of New-York. But obsessions of the creative sort often bear prized fruit. In 1924, Van Wyck published an extraordinary treatise on Brooklyn’s earliest history, entitled Keskachauge. Nearly eight hundred pages long, it is one of the most voluminous and assiduously researched works of local history ever published in the United States. In it, Van Wyck argued that the Strome Kill and its uplands—a peninsula called Baes Jurians Hooke, heart of the Marine Park neighborhood today—might well have been Gotham’s Plymouth Rock.

Austin’s macabre display of human skeletal remains exhumed from the west side of Gerritsen Creek c. 1900, close to present intersection of Avenue U and Burnett Street. Daniel Berry Austin photograph collection, Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

First contact, in Van Wyck’s view, may have taken place as early as 1609. On September 3 that year, Henry Hudson and the crew of the Half Moon swung up the coast around Sandy Hook and “came to three great Rivers.” One of these was Raritan Bay, the other the Narrows, and the third Rockaway Inlet (then much farther east than it is today). A journal kept by Hudson’s mate, Robert Juet, indeed tells of an attempt to enter the “Northermost” of these “rivers,” but that shoals and sandbars and “ten foot water” forced the ship back. As Van Wyck saw it, “Hudson’s first intention on the afternoon of September third was to go into Jamaica Bay.” This meant that, however briefly, the Half Moon “probably came head on in the direction of Flatlands,” and that its crew could well have ended up making landfall at the mouth of the Strome Kill. He imagined that “every member of the tribe . . . must have seen the strange object that loomed up on the horizon about three o’clock that afternoon, headed straight for the entrance to the bay. These Indians and their chiefs would have been more than mortal if they had not followed with the closest scrutiny every move the stranger made that afternoon until darkness came.”12 Van Wyck also argued that crew members left behind by Dutch trading ships in 1614 and 1615 to dispose of goods might have “wintered at Keskaechqueren, under the protection of the great chief Penhawitz”—thus making Flatlands possibly “the oldest place of white abode in Greater New York.” Van Wyck further conjectured that the Strome Kill was the haven where Cornelius Hendricksen and the crew of the Onrust wintered in 1616. The Onrust (Restless) was the first ship built in the Americas, whose modest draft allowed it to navigate waters too shallow for the Half Moon. Hendrickson—and Adrian Block before him—used the craft to explore much of the Connecticut and Long Island coastlines, leading some to call it America’s first research vessel.13

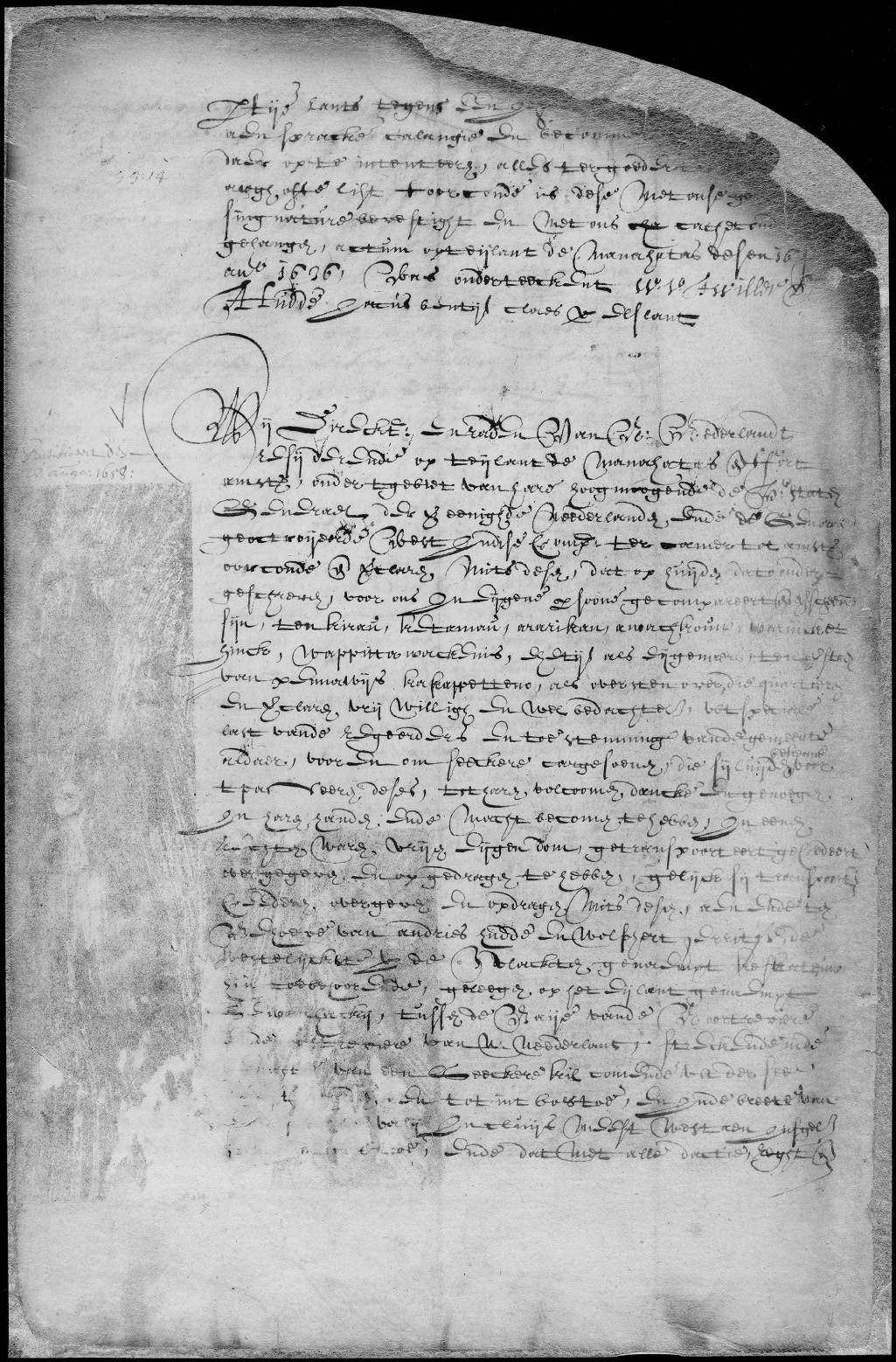

Even if Van Wyck was wrong about all this—about Hudson and wintering traders and the hunkered crew of the Onrust—Keskachauge was certainly settled by 1636, a full decade before the village of Breuckelen on the waterfront at Fulton Street. It was thus among the first permanent settlements in New Netherland and the earliest place colonized by Europeans on Long Island. That summer, several major land conveyances were made to the Dutch by a delegation of Canarsee led by chiefs Penhawitz and Kakapetteyno—in exchange for “certain merchandise” and purportedly with the blessing and “consent of the community.” The first was made to Wolphert Gerritsen and Andries Hudde for “the westernmost of the flats called Kestateuw.”14 The smaller middle and eastern prairies (known, respectively, as Castuteeuw and Casteteuw) were conveyed to two Dutch West India Company agents still in their twenties—Jacobus van Corlaer, first commissary of wares; and Wouter van Twiller, who had replaced Pieter Minuit as director general of New Netherland three years earlier.15 Hudde was a surveyor from Amsterdam; Gerritsen had been a baker in the Utrecht town of Amersfoort before sailing to New Netherland in 1625. A forebear of the Roosevelt clan, he was recruited to run a farm in lower Manhattan before striking out for Keskachauge. All told, some thirty-six hundred acres were conveyed by Penhawitz and Kakapetteyno, who almost certainly did not realize that the transactions would forever alienate their people from the land. For the eager and ambitious Van Twiller—satirized as corpulent, bumbling “Walter the Doubter” by Washington Irving (who confused the youth with his father)—the Casteteuw land grant was just another investment in an impressive portfolio that included most of Red Hook, a tobacco plantation in Greenwich Village, and the islands known today as Wards, Randalls, Roosevelt, and Governors (the last a reference to Van Twiller himself). Though he had no interest in homesteading, he seems to have “caused” several structures to be erected on his land at Casteteuw.16

Patent of Andries Hudde and Wolphert Gerritsen van Couwenhoven for a tract of land on Long Island, June 16, 1636. The deed conveys to the colonists the “westernmost of the flats called Keskateuw . . . on the island called Sewanhacky [Long Island].” New York State Archives—Dutch colonial patents and deeds, 1630–1664 (Series A1880, Volume GG).

One of these has miraculously survived to the present—the Pieter Claesen Wyck-off House at Ralph Avenue and Clarendon Road. With its medieval massing and steep-sloped roof, the Wyckoff house is a true envoy from Gotham’s deepest past—the oldest building in New York City, one of two or three oldest structures in all New York State and the very first building designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission when it was founded in 1965. Across the street from a car wash, a salvage yard, and a geriatric diaper supplier called Elderwear (which Google Maps shows, incorrectly but appropriately nonetheless, as occupying the Wyckoff House itself), the building hovered on the edge of destruction for decades, and was known locally in the 1980s as America’s oldest crack house. It is today a lovingly managed house museum, thronged by schoolchildren on field trips. Wolphert Gerritsen, the oldest and most experienced of the group, was the only one to take the whole settlement business seriously. He erected a house and barn at the northeast corner of Flatbush and Kings Highway and called his spread the “Bouwery of Achterveldt”—literally the farm beyond the plains. Hudde, too, erected a number of buildings, including a tobacco barn and what may have been the old “Sand Hole House,” razed in 1889, that stood on the north side of Kings Highway at East Thirty-Fifth Street. Gerritsen’s Achterveldt appears on the Manatus Map, placed just north of an inlet—in all likelihood Gerritsen Creek—and keyed to an index by the number 36. Just below and to the left of this is a small building that is likely the Pieter Claesen Wyckoff house, which would have been about a year old by the time the map was drawn. Though Hudde left for New Amsterdam in 1638 to become the colony’s first surveyor general, he held on to his farm, leasing it in 1642 for an annual rent of “two hundred lbs. of well cured tobacco.” Gerritsen remained at Achterveldt for the rest of his life. By the 1660s, it had become a vibrant rural village named Nieuw Amersfoort, after Gerritsen’s Old World hometown. With the ascendence of English rule in 1664, Nieuw Amersfoort became the town of Flatlands.17

What made this place so vital to the Dutch was not good soil but mollusk shells, or—more precisely—the tiny tubular beads drilled by the Indians from quahogs, whelks, and periwinkles known as wampum. Wampum had long been used for ceremonial purposes by the coastal Algonquians, but with the arrival of trade-obsessed Europeans, it gained a powerful new role as legal tender—and not only for trade with the Indians. Town records indicate that “wampum was exchanged for a wide range of goods and services between 1647 and 1660,” writes Lynn Ceci, and “wages in wampum were paid to cowherders and carpenters, and to a schoolteacher or laborer.”18 As the specie’s value soared, Canarsee Indian settlements at Narriock (Sheepshead Bay), Massabarkem (Gravesend), Muskyttehool (Paerdegat Basin), Equendito (Barren Island), Shanscomacoke, and—especially—Winnipague (Bergen Beach) became the leading wampum production centers on Long Island. Located at the headwaters of the Strome Kill and linked by trade routes to the East River and Long Island, Keskachauge became a busy entrepôt—the “Wall Street of the Indians,” as Van Wyck called it—especially after the fur trade was thrown open by the Dutch in 1639. Wampum was “the source and mother of the beaver trade,” the precious lucre that both Dutch and English bartered a range of goods for—cloth, tools, guns, spirits, tobacco—and then carried north to exchange for beaver pelts from the Mahican and Mohawk peoples. The fur was ultimately shipped to Europe and sold at great profit, mostly to be pressed into felt for men’s hats. Scholars have hypothesized that it was wampum—not agriculture or town founding—that led to the initial acquisition of coastal sites like Keskachauge and the Strome Kill by the Dutch; these were, after all, the mints of the coin of the New World realm. This countered orders by the Dutch West India Company to find productive farm and pasture lands to sustain the colony, which was experiencing frequent food shortages and “near starvation” by 1633.19

Pieter Claesen Wyckoff House, c. 1652. Historic American Buildings Survey photograph by E. P. Mac-Farland, 1934. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Wolphert Gerritsen was involved in just such wampum speculating. He had been deputized in January 1630 to help an Amsterdam pearl and diamond merchant named Kiliaen van Rensselaer build a New World empire trading wampum and pelts. Van Rensselaer was a founder of the West India Company, but it seems his real ambition was fattening his larder at company expense. He also happened to be Director General Wouter van Twiller’s uncle. Several months after hiring Gerritsen, Van Rensselaer secured a vast patroonship on the upper Hudson River, a thousand-square-mile domain anchored by Fort Orange and the fur-trade boomtown of Beverwijck—literally “beaver district” (later named Albany). With the Strome Kill at one end and Beverwijck at the other, Van Rensselaer had his hands in two of the three fur-trade cookie jars. These machinations made him fabulously rich. They also got many of his cronies in trouble. In a March 1651 letter to Peter Stuyvesant, West India Company directors blasted Van Rensselaer’s minions and ordered the new director general to guard against unauthorized landgrabs like those at Keskachauge—where “very few improvements in regard to settling, cultivating, tilling or planting have been made.” They called out Van Twiller for having greedily “stretched out his hand for the two flats on Long Island,” and castigated Gerritsen and Hudde for not settling “the fiftieth part” of their expansive tract.20 The following year, in July 1652, an ordinance was passed prohibiting men “covetous and greedy of land” from “directly or indirectly . . . buying or attempting to obtain any Lands from the Natives.” Keeping such valuable land locked up prevented the “Planting of Boweries” and thus “delayed and retarded” the fruitful peopling of New Netherland. They also voided all previous acquisitions of land, including “both the small Flats on Long Island claimed by the former Director Wouter van Twiller” and “the Great Flat . . . with the lands adjacent claimed by Wolphert Gerritsen and Andries Hudde.”21 This annulment would cast a three-hundred-year cloud of doubt over the actual ownership of all this land. The Gerritsen-Hudde tract, especially, was the focus of a running legal battle that eventually pitted descendants of both families against Robert Moses and the city of New York—a latter-day Jarndyce versus Jarndyce that the Brooklyn Eagle described as “the most intricate trial in the annals of the Brooklyn Supreme Court.”22

Beaver pelts and wampum belts became lodestars of Indian life, too, but with far more malevolent effects. With their intimate knowledge of the coast and its shellfisheries, the Canarsee were well positioned to exploit the rising value of wampum. But it was a Faustian bargain. Prior to European contact, the Algonquian peoples led a peripatetic existence—living “rudely and rovingly,” as one observer put it, “shifting from place to place.”23 Even coastal tribes like the Canarsee stayed only part of the year at the shore, typically in summer. As fall approached, they moved inland where there was plentiful wood for fires and game animals to provide meat, fat, and furs for warmth. With the new system of trade, life became more sedentary; seasonal shore camps like Shanscomacoke became permanent or semipermanent villages, a change revealed to archaeologists by dramatic increases in shell detritus and more extensive burial grounds. Ancient patterns of life were scuttled for wampum, and a once proudly self-sufficient society gradually sank into a state of almost total dependence on Dutch and English trade.24 And then the whole rodent-based economy collapsed: overhunting caused beaver populations throughout the Northeast to crash, bringing the entire trade triangle down with it (wampum lingered; it was manufactured on Long Island into the 1870s to seal treaties with Indians on the Western frontier). Twilight came fast for the Canarsee, their long day ending with dispossession and death from war and “raging mortal Disease.” Keskachauge was deserted as early as 1640, at the outbreak of the bloody Governor Kieft War. These first people of the American land quietly vanished “as noiselessly as the morning mists,” wrote J. Thomas Scharf, “disappear before the advancing day.” In 1670 Daniel Denton eulogized: “To say something of the Indians, there is now but few upon the Island . . . how strangely they have decreast by the Hand of God.” The last Canarsee Indian was said to have died in 1832, buried in a shroud sewn by an old Dutch friend.25

Detail of beaver and wampum in the Seal of New Netherlands, 1623. Cast iron roundel by Rene Paul Chambellan, 1931, one of five designs he created for the West Side Elevated Highway. Photograph by author.

Our earliest eyewitness account of the Strome Kill uplands was penned in 1679 by Danckaerts and Sluyter, and describes a landscape strikingly similar to Holland. “There is toward the sea a large piece of low flat land,” they wrote, “which is overflowed at every tide . . . mirry and muddy at the bottom, and which produces a species of hard salt grass or reed grass.” This was mown for hay, they noted, “which cattle would rather eat than fresh hay.” The men were delighted to find the uplands around the Gerritsen estuary “entirely covered with clover in blossom, which diffused a sweet odor in the air for a great distance.” They described the region as “low and level without the least elevation,” but indented with waterways “navigable and very serviceable for fisheries.”26 On the Strome Kill itself they came upon a “grist-mill driven by the water which they dam up in the creek.” This structure, one of the earliest industrial buildings on the Eastern Seaboard, was erected by the Gerritsen clan between 1670 and 1686, when it appears in the Dongan Patent. Rebuilt several times, it was the very essence of sustainability: water penned back at high tide behind a rockpile dam was discharged as needed through a sluiceway, turning a drive wheel that powered the millstones via wooden gears and shafts and leather beltings. The plant produced flour for Washington’s army and was pressed into similar service by Lord Cornwallis to feed his men before the Battle of Brooklyn, until Samuel Gerritsen—perhaps tired of being miller-in-the-middle—disabled it by contriving to “lose” the millstones, at least according to local lore. Operating into the 1890s, the faded red mill was a local landmark—a picturesque ruin, its big wheel motionless yet still “giving forth a musical swish as the water boils below.” Tragically, it burned to the ground on the night of September 4, 1935. A night watchman and police patrolman on-site the night the mill burned claimed to have seen nothing. The mill was being restored by the Parks Department at the time, and plans for a total restoration as a working mill museum by architects Aymar Embury II and H. B. Guillan had just been completed. Though nothing remains of the mill except for a pair of stone posts that held the sluice gate, the tidal dam can still be seen at low tide just below Burnett Street at Avenue V.27

Cord-marked pottery shard, Late Woodland period (500–1000 CE), from west bank of Gerritsen Creek. Recovered in a 1979 excavation by the Brooklyn College Archeological Field School. Photograph by Frederick A. Winter.

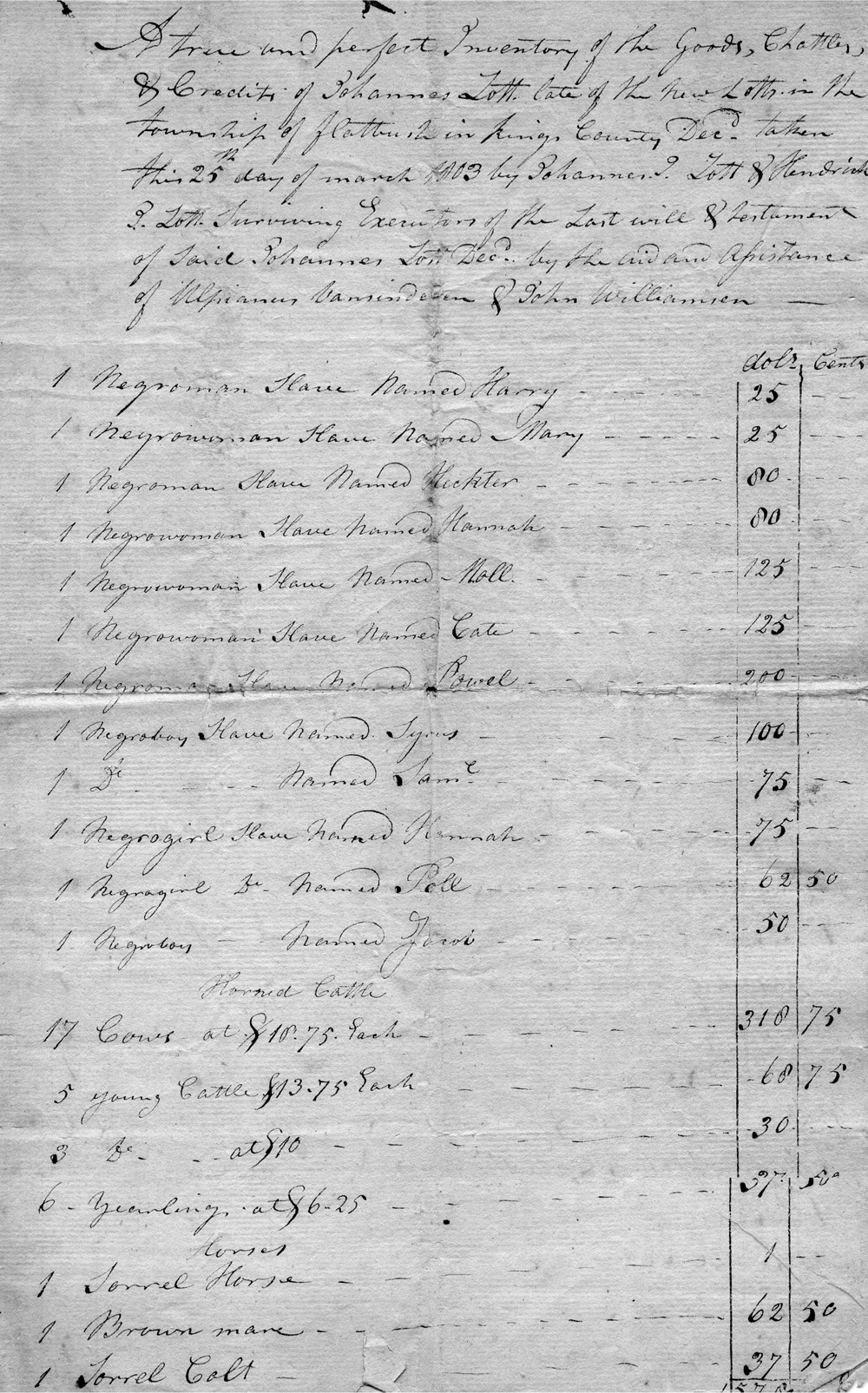

Samuel Gerritsen’s daughter, Elizabeth, married into the Lott family in 1799. That year, Hendrick I. Lott, Johannes’s grandson and heir to the plantation, was busy erecting a substantial addition to the 1720 house. He had plenty of help. A 1792 inventory of the Lott farm lists no fewer than twelve enslaved African Americans—six men and six women—who undoubtedly helped construct the magnificent Dutch-Federal house on what is today East Thirty-Sixth Street. Slavery was an essential element of New York life in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As historian Shane White writes, New York was “the center of the heaviest slaveholding region north of the Mason-Dixon line.” Only Charleston, South Carolina, surpassed New York in the total number of enslaved residents. And no place in the state had more slaves per capita than Kings County, where one in three residents was in bonded servitude—“a ratio that would not have been out of place in the South.” This was especially the case in Dutch towns like New Utrecht, where 75 percent of white households owned slaves, or Midwout (Flatbush), where African Americans constituted 41 percent of the population in 1790. By this time, Kings County was supplying a lion’s share of meat, vegetables, grains, fruits, and other farm products consumed by the surging city across the river. Proximity to urban markets made many Dutch families prosperous, fertilizing their fortunes as the manure they hauled from Gotham’s streets and stables fertilized their fields. Kings County became a land of lush and verdant bounty. “I remember no spot,” recalled Timothy Dwight, “where the produce of so many kinds appeared so well . . . the wheat, winter barley, flax, and oats, are remarkably fine.” Indeed, “wherever the country was cultivated,” he observed, “its face resembled a rich garden.” But Dwight ignored a vital aspect of the scene. However thorough a portrait his Travels are of New York and Long Island two hundred years ago—pages of meticulous observations on the manners and customs of Long Island folk, and the geography, flora, and fauna of the region—he says nothing about the system of human bondage that created the pastoral scenes he so admired, about the forgotten souls who tilled the soil and helped feed the rising metropolis through its long childhood and adolescence.28

Gerritsen tide mill, 1914. Photograph by George S. Ogden. Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Archaeologist Alyssa Loorya photographing a channeled stone pier that held the sluice gate of Gerritsen tide mill, Marine Park. Photograph by author, 2016.

Dwight was not the only one to gloss over this aspect of Kings County life and labor. Most nineteenth-century accounts of Brooklyn’s past depict slavery in a warmly nostalgic light, pruning it carefully from uglier manifestations of slavery elsewhere in the world. “This race for more than a century and a half,” wrote Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt of African Americans in 1899, “formed part of the family of every Dutch inhabitant of Kings County. Speaking the same language, brought up to the same habits and customs, with many cares and interests in common, there existed a sympathy with and an affection between them and the white members of the household such as could scarcely be felt toward the strangers who now perform the same labor under such different circumstances.” To Vanderbilt and her circle, slavery in early New York was “fundamentally different, and better,” writes Craig Steven Wilder, “than slavery in the Southern colonies”—so much so that they effectively “recast the Knickerbocker-Yankee enslavement of Africans as the single kindest act that one group of people ever visited upon another.” Yet documentary evidence does suggest that the lot of slaves in New Netherland was not as cruel or repressive as in the West Indies or on the plantations of the South, that the position of free blacks was better there than perhaps anywhere else in the New World. As Edgar MacManus has argued in A History of Negro Slavery in New York, the Dutch had little interest in creating a racialized caste system of the sort that would develop in the West Indies or the American South; for “neither the West India Company nor the settlers,” he writes, “endorsed the specious theories of Negro inferiority used in other places to justify the system.” The liberties enjoyed by free blacks in New Netherland bear this out. They could own property and serve in the militia (Jews could do neither); they could own white servants and intermarry with whites, and “were accepted or rejected by the community on their own merits as individuals.” Enslaved blacks had the same standing as whites in a court of law, and with a system of “half-freedom” that allowed conditional release, bondage in the colony was often like a severe form of indentured servitude. There were indeed no slave uprisings in New Netherland, and the fact that the Dutch armed their bondsmen to fight enemies indicates a certain degree of trust. All told, MacManus concludes, “master-slave relations were good . . . and generally free of the corrosive hatred which in other colonies helped to create brutal systems of repression.” It was only later, after the institution of harsher English controls over slaves—including a separate judicial system and legal code for bondspeople—that slavery in the city and its hinterlands began to take on its more egregious aspects.29

Kindly or not, Brooklyn’s Dutch settlers practiced chattel slavery and prospered at the expense of men and women squeezed for their labor and deprived of freedom. They had the greatest need for labor in the preindustrial city, and thus became New York’s “largest and most dedicated slave owners”—more deeply engaged in extracting labor from bound Africans than any other ethnic group in the city’s past.30 Even if later anti-Dutch sentiment greatly exaggerated their sins (so avaricious were the Knickerbockers, opined a visiting Frenchman in the 1790s, that “they almost starve themselves, and treat their slaves miserably”), the truth remains that the pious Calvinists of Kings County not only “owned Africans,” writes Wilder, but “advertised for runaways, auctioned human beings, and exhibited the violence, hypocrisy, and immorality that people who systematically exploit other people eventually must display.” These “Little Masters,” as Wilder calls them, practiced an intimate form of slavery, but one no less morally repugnant than those of greater scale and brutality elsewhere. Many of these men would become vocal opponents of abolition and emancipation. They formed a Southern planter class in miniature—less systematically violent than their Virginia brethren, perhaps, but just as “committed to a way of life premised upon the domination of other people.”31 Those who excused slavery in Kings County vis-à-vis the industrial-scale enslavement of Africans in the plantation South failed to see that scattering the population of bondspeople so thinly “impaired black family development, increased the possibility of sale of kinfolk, and exacerbated conditions for escape among isolated young men and women.” And scores of men and women did indeed become “blacks who stole themselves.” One of these was a sixteen-year-old boy named Jack who ran away in July 1783 from Jeromus Lott, who posted “5 Guineas Reward” for his return. Johannes H. Lott’s youngest son, he was not a kindly soul. A loyalist during the Revolution and “notorious for his cruelty to our prisoners,” Lott and two of his slaves were kidnapped by a band of New Jersey patriots in 1781, who hustled the trio to a whaleboat waiting in the Gerritsen marshes. The men were taken to New Brunswick, where Lott was “compelled . . . to ransom his negroes.” Jack escaped from Lott again in May 1784. That he bore an iron collar around his neck marked with the initials “JL” tells of a darker truth than what Gertrude Vanderbilt and her fellow gentry allowed to flow from their treacle-dipped pens.32

James Ryder van Brunt, Van Brunt Homested, c. 1865. Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Miriam Godofsky.

Kings County in the eighteenth century was among the least free places in New York State, its enslaved population quadrupling between 1703 and 1790. The heavily agricultural towns south of the terminal moraine—Flatbush, Flatlands, Gravesend, and New Utrecht—were akin to the coastal-plain counties of Virginia and North Carolina, where most of the big slaveholding plantations of those states were located. While the Lotts owned a mere fraction of the slaves that worked a typical Virginia plantation at the time, they were nonetheless among the largest slaveholders in Kings County. As noted earlier, Hendrick Lott owned a dozen bonded men and women in 1792. And then, sometime before 1810, all of Lott’s slaves were freed. As it is unlikely that so large a group of enslaved men and women would have been able to buy their freedom all at once, Lott almost certainly chose to emancipate his slaves. Federal census records indicate that he then hired most back as paid laborers; some would remain in his employ into the 1840s. Only an elderly woman, for reasons unknown, was kept on in bondage. Why Lott would choose to suddenly free his bondspeople is a puzzle—he left no diary or letters to explain himself. Voluntary manumission was not unknown among slaveholders at this time. In fact, while the slave population of both New York and Kings County increased steadily all through the eighteenth century, census returns show a sudden drop in both places between 1800 and 1820. In Kings County, the number of enslaved residents fell by almost half—from 1,506 to 879. Manumissions were also up sharply: in New York City there were a mere 36 recorded manumissions between 1791 and 1800, and 260 between 1801 and 1810. This was due not to a sudden outbreak of goodwill among slaveholders, but to a piece of legislation—the Gradual Manumission Act of 1799. It stipulated that all children of slave women born after July 4 that year were to be free, though they must remain indentured to their masters until the age of twenty-five (for women) and twenty-eight (for men). As Shane White writes, it was not until 1810 that “the full impact of the act was felt in the city,” with the number of New York slaveholders falling by more than 25 percent from 1800—“the lowest number recorded in the city in any of the first three federal censuses.” However extraordinary Lott’s decision appears to us, it was fully in step with the evolving state of slavery at the time.33

The Gradual Manumission Act clearly signaled the coming of emancipation. While some slave owners would hold on to their chattel to the bitter end, others saw the writing on the wall and set their slaves free. Such decisions likely also involved agency and action on the part of the bondspeople themselves. As White has put it, “Once it was certain slavery would eventually end, slave owners became more susceptible to pressure from their slaves and often agreed to arrangements whereby slaves were liberated in consideration of a number of years of trouble-free service or cash or both.”34 Indeed, Lott’s manumitted slaves stayed and worked for the family long after being granted freedom—a fact typically attributed to loyalty and affection, but that was more likely simply part of the deal. And yet manumission literally involved letting go of an investment. Such an action—the willful reduction of one’s own capital—begs an explanation. Lott no doubt surmised that full emancipation was on the horizon, but he could not have known it would happen in 1827, the year slavery was abolished in New York State. In other words, freeing his slaves circa 1810 deprived his three children of a substantial inheritance. So it is possible, at least, that other factors account for Lott’s action—that perhaps he manumitted his slaves because he believed it was the right thing to do. Indeed, Lott family lore suggests that Hendrick might have been an early abolitionist. The evidence is thin. We know that he was a member of the Flatlands Dutch Reformed Church, buried in its churchyard at East Fortieth Street and Overbaugh Place; and that manumission was considered “a meritorious act in the eyes of God.” But it is unclear whether Lott was pious enough to let faith overrule financial interest.35

“A true and perfect Inventory of the Goods, Chattles [sic], & Credits of Johannes Lott,” 1792, beginning with a list of his twelve slaves, five of whom—Syrus, Sam, Hannah, Poll, and Jacob—were children. Collection of Robert Billard.

Moreover, faith of the Dutch Reformed sort did not imply charity on the racial front. The Dutch Reformed Church was perhaps the least progressive of the Protestant sects in New York and long vacillated on whether to allow Africans into its fold. The learned and popular minister Henricus Selyns, who served congregations in New Amsterdam and Long Island, instructed enslaved Africans in the faith, but would not baptize a baby if he suspected its parents “wanted nothing else than to deliver their children from bodily slavery, without striving for piety and Christian virtues.” Indeed, baptism of the bonded became a matter of great controversy. Some ministers came down forcefully on the side of the angels. Godefridus Udemans, writing in 1638, argued that a Christian was faith bound to free any slaves who converted to his faith; for if they were willing “to submit themselves to the lovely yoke of our Lord Jesus Christ . . . Christian love requires that they be discharged from the yoke of human slavery.” But colonial empires are built on greed and grim expedience, not Christian kindness. Slave owners in seventeenth-century New Netherland, fearful of the losses conversion might entail (not to mention that it might “give the Negroes ideas about liberty and freedom”), discouraged missionary work among their slaves. The matter was eventually settled in 1706, out of church and not by the Dutch, but by the English colonial legislature of New York, which made it completely legal, if not moral, for a Christian to be enslaved. All told, “there was little to admire,” writes church historian Gerald De Jong, “regarding the attitude of the Dutch Reformed Church toward slavery in colonial America.”36

Manumission of the Lott slaves has seeded stories that Hendrick’s house provided refuge for runaway slaves—that it was, in other words, a way station or depot on the Underground Railroad. Lott descendants alive today recall hearing stories as children that fugitives were given sanctuary on the farm—“that ships came quietly in the night to shore,” recalls one family member, “and the people who were part of the Underground Railroad would shepherd the slaves into the house.” Of course, tales like this envelope nearly every antebellum house, church, and tavern this side of the Mason-Dixon line. Were a nickel set aside for each property rumored to be part of the Underground Railroad, the federal debt could be paid off in a day. It is not surprising that many would claim connection to this heroic chapter in American history, for reasons of collective sin cleansing if nothing else. The Underground Railroad is an epic part of our national mythology, as hopeful as it is hopelessly misunderstood. Only in recent years has the traditional narrative of the Railroad as the infrastructure of white magnanimity given way to a more nuanced view of its fractal-like complexity—and greater agency accorded freedom-seekers themselves in its actual operation. The very nature of the Underground Railroad—secretive, spontaneous, always in the shadows—makes it a notoriously difficult subject to research. It is virtually impossible to test the veracity of claims like those of the Lott family. The best we can do is expose them to the light of analysis, marshaling evidence from geography, historical context, and archaeology. Is it possible that the Lotts helped spirit enslaved African Americans to freedom? In a word, yes. To start, there is no question that Kings County played a central role in helping move escaped slaves north in the nineteenth century—especially after the draconian Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights—a topic of chapter 10—was widely hailed as the “Grand Central Depot” of the Underground Railroad. Though he was hardly blameless himself, Beecher’s thunderous oratory did as much for American abolitionism as did his sister Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Kings County was also home to Willis Augustus Hodges, a free black Virginian who ran an antislavery newspaper in Williamsburg, and abolitionist orator James W. C. Pennington sought refuge in Brooklyn after escaping bondage in Maryland. The latter went on to become the first African American to study at Yale, and later helped integrate streetcar lines in both Brooklyn and New York City.37

The rural southern half of Kings County was a far less tolerant place. And yet there were exceptions. During the Draft Riots of 1863, blacks fleeing mob violence in Brooklyn and across the East River were hidden in an ancient windmill on the John C. Vanderveer farm, between Canarsie Lane and the long-vanished Paerdegat pond. It was a good place to take refuge. Built in 1804, the mill was a fortress of strength, with a stone foundation and oak timbers twenty-eight feet high and nearly three feet thick. It was being used as a barn at the time, the great sails having been wrecked in a storm decades earlier. Like the Gerritsen tide mill, the Vanderveer plant was also lost to fire, burning on the night of March 4, 1879, in a spectacle of destruction that sent up “showers of sparks . . . like gold-dust sprinkled on a cloth of blue.” The geography of the outwash plain may itself have aided bids for freedom. The marshy shore of Jamaica Bay, with its reed-choked serpentine estuaries, would have offered a hidden backdoor entry into Brooklyn and New York City for fugitives coming by boat from New Jersey and points south. The Lott farm included most of the secluded north bank of Gerritsen Creek, the largest tidal estuary on the bay and navigable by ships as far as the mill dam (Van Wyck recalled “sloops of twenty-four tons burden, and in one case thirty tons” making trips in the 1870s between the Gerritsen mill and New York City, “before either Mill Creek or the Strom Kill had been dredged”). At the east end of the dam was Kimball Landing, from which an old Indian path—known as Lott’s Lane or the Strome Kill trail—led to Flatlands village, literally passing between the Lott house and its stone kitchen building. In other words, freedom-seekers could have been ushered to the house in swift and total secrecy. We know that tidal estuaries similar to Gerritsen Creek were used for just such purposes farther out on Long Island, where a network of sympathetic Quaker Meetings offered sanctuary to runaways. One was the Jerusalem River, known today as Bellmore Creek, which led to a settlement of free blacks near present-day Wantagh known as The Brush. This place, nestled amidst the larger Quaker community of Jerusalem, was also a waypoint and destination for freedom-seekers coming out of New York and Brooklyn. By the 1830s there was an African Free School there and later an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. In its burial ground nearby—itself now buried in a Levitt subdivision at about 1460 Oakfield Avenue—were interred the remains of several men who fought in the Civil War with the Twentieth and Twenty-Sixth regiments of the United States Colored Troops.38

But Gerritsen Creek and the Lott house led to an even greater prize—Weeksville, one of the largest free black communities in the United States. Just four miles to the north, Weeksville developed in the 1830s on the northernmost lands of the old Gerritsen landgrab and soon became a major destination for those escaping bondage from the South. Nearly 45 percent of Weeksville adult residents in 1850 were born below the Mason-Dixon line, many of whom—perhaps most—were former slaves. “Weeksville’s proportion of southern-born African Americans,” writes Judith Wellman in Brooklyn’s Promised Land, “was one of the highest of any city in the United States.” Only Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and Cincinnati—all major gateways to freedom—had higher proportions of African Americans born in the South. While many of these people came to Weeksville via New York and Brooklyn, it is very likely that others came up from Flatlands just to the south. Weeksville would have been about an hour’s walk or a twenty-minute wagon ride from the Lott house via Flatlands Neck Road and Hunterfly Road (from the Dutch Aander fly, or “over to the marshes”). One of Weeksville’s earliest residents was himself a former Lott slave, Samuel Anderson, born into bondage in 1810. Anderson’s master was Jeremiah Lott, who clearly did not agree that those baptized into the Christian flock deserved emancipation. A devout man and later a preacher himself, Anderson was baptized as a youth and attended services at the Flatbush Dutch Reformed Church, where blacks were required to sit apart from whites in an upstairs gallery—“the men on one side,” he recalled, “the women on the other.”39

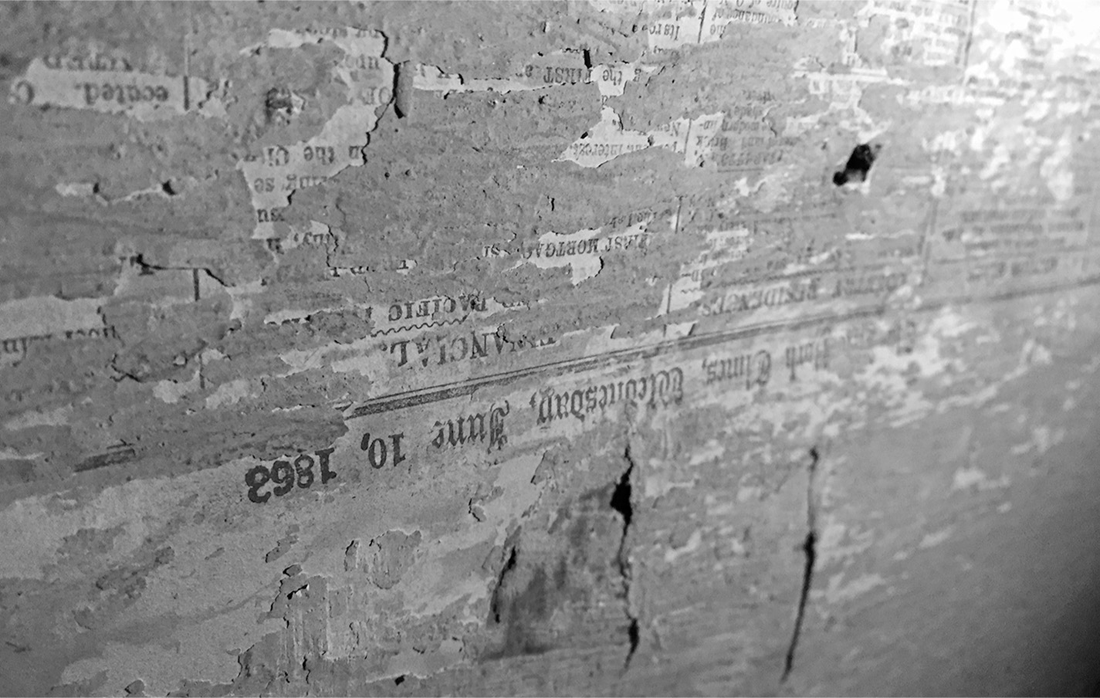

Newsprint papered over passageway to hidden attic room, Hendrick I. Lott House. This page, from the New York Times, is dated June 10, 1863, about three weeks before the Battle of Gettysburg. Photograph by author, 2013.

The most telling bit of evidence that the Lotts may well have offered sanctuary to fugitive slaves is in the building itself. As a child in the 1960s, Catherine Lott Divis—a direct descendant of Hendrick Lott whose father grew up in the East Thirty-Sixth Street house—was told in hushed tones by her elderly aunts about a secret hiding place on the second floor. “They took me upstairs with great fanfare and solemn tones and showed me the Room,” she told the New York Times in 2002. At the back of a large closet, behind hatboxes and a rack of clothes, was a small, low door papered over with newsprint from 1862. Behind it was a tiny hidden room; there, Divis was told, fugitive slaves smuggled in by boat would be hidden before continuing on to freedom. “I was not to breathe a word of it,” she said; for by her family’s unspoken code “if something was a secret in the 1800’s it was always a secret.” The house had other tales to tell, coaxed into the light by a team of Brooklyn College archaeologists who began studying the house in 1998. Led by Christopher Ricciardi and Alyssa Loorya, the students dug more than seventy trenches on the site, patiently sifting through several tons of excavate. They uncovered the foundations of the old plastered-brick kitchen house, razed around 1927 to make way for East Thirty-Sixth Street, and over the four-year project period unearthed thousands of pottery shards, glass and ceramic fragments, pipe stems, toys (including several haunting doll heads), clam and oyster shells, and other faunal remains—the detritus of long and prosperous habitation by scores of women, men, and children.40

Corncob talisman discovered beneath the floorboards of Lott House garret room. Photograph by Alyssa Loorya, 1999.

Yet the most extraordinary discovery at the Lott house was not underground but overhead. One afternoon, a project assistant bumped her head on the ceiling in the eighteenth-century lean-to addition close to East Thirty-Sixth Street. The ceiling appeared to give way. Loorya and Ricciardi grabbed a ladder and flashlights. In the ceiling they found a covered hatch, behind which were the truncated remains of a staircase. The stairs apparently once continued to the ground and led to the second floor of the 1720 house, where a door had long ago been sealed off. Climbing up, the pair discovered twin garret rooms in the attic space on either side of the stairs. The rooms were low and small, about ten feet square and at most four feet high. The doors to the garret rooms had been removed but lay close by. Centuries-old candlewax was splattered all about. When Loorya and Ricciardi took up some floorboards, they discovered something truly astonishing—an assortment of objects that had been placed carefully beneath each entrance before the floorboards were nailed down. On the north side was a pelvis bone from a sheep or goat, an oyster shell, a small pouch tied with hemp, and an eighteenth-century child’s shoe. On the south side were several corncobs—one whole, the other snapped in half and set at right angles above and below the first in the form of a cross. What Loorya and Ricciardi had come upon were arrays of religious talismans clearly African in origin. They had discovered the living quarters of at least some of the Lott family slaves. Caches of objects like these were previously known only in the South; never before had anything like this been seen in New York. As Loorya explains, “the objects were meant as defensive talismans against certain malevolent spirits, to create a kind of protective spell for the occupants,” and were usually placed “near doors and fireplaces, where spirits were thought to come and go.” The crossed corncobs were themselves likely a microcosm of the universe itself, a Bakongo cosmogram in which the horizontal plane—the unbroken cob—was meant to “symbolize separation,” says Loorya, “of the world of the living from the realm of the dead.” Through the dark of two centuries, visited only by spiders and mice, the crossed cobs consecrate still a small, fraught corner of the world, a simple act of faith by a people far from home.41

Ruins of the eighteenth-century Johannes Lott barn near present intersection of Avenue R and East Thirty-Fifth Street in Marine Park. Photograph by Eugene L. Armbruster, 1922. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.