CHAPTER 13

PARADISE ON THE

OUTWASH PLAIN

When it’s nesting time in Flatbush,

We will take a little flat,

With welcome on the mat

Where there’s room to swing a cat.

I’ll hang up my hat, I’ll hang up my hat . . .

—JEROME KERN AND P. G. WODEHOUSE

When the six hundred warplanes of Douglas MacArthur’s aerial armada rounded the Narrows for Floyd Bennett Field on May 23, 1931, the pilots—future mayor Fiorello La Guardia among them—would have seen off to their left a landscape churned asunder by real estate development on a scale unprecedented in American history. Though stilled briefly by the Depression, a great tide of timber, brick, and mortar had inundated this land tilled since the 1640s, transforming fields of cabbage and corn into a tidy grid of middle-class homes. Much of this metamorphosis occurred in a single decade, and nearly all of it south of the terminal moraine. Housing the multitude, rich and poor, was nothing new for Brooklyn—known for much of its history as the City of Homes. That era effectively began on August 17, 1807, when an erstwhile painter and mechanical genius named Robert Fulton launched the first commercial steamboat. Fulton later established a regular ferry line across the East River from lower Manhattan, making Brooklyn easier to reach than almost any other part of town. The speedy, scheduled service encouraged real estate speculators to buy up the old farms on the heights across the river and subdivide them into lots for sale to prosperous merchants and entrepreneurs. One of them was a former trader and gin-distiller named Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, who laid out the street grid of Brooklyn Heights and fortified his investment by helping Fulton monopolize East River ferry operations. This, of course, also helped the competition, and there was plenty—Gabriel Furman, Henry Remsen, the brothers John and Jacob Middagh Hicks, all of whom modestly named streets after themselves and their families (or fruit, in the case of delightful Pineapple, Cranberry, and Orange Streets). By the 1830s, the pastoral bluff above the East River was fast becoming America’s first commuter enclave. The residential development of Brooklyn was under way. The pace of development jumped in the 1850s, an era of national prosperity fueled by the Gold Rush. Completion of Prospect Park in the early 1870s prompted another surge of development, led by Edwin Clark Litchfield, railroad magnate and dredger of Gowanus Canal whose Italianate mansion is today the Brooklyn headquarters of the New York City Parks Department. The 1883 opening of the Brooklyn Bridge and the long boom of America’s railroad age ignited Brooklyn’s greatest, most expansive period of development yet. Touring the city in 1886, Washington Post columnist Julian Ralph described Brooklyn’s growth as “the most amazing thing in this part of the world,” dwarfing even “all the tales with which the western borderland has nourished us during the past quarter of a century.” Riding the el, he saw “literally miles of dwellings in course of erection in slender rows, in solid squares, in detached units.”1

Many of these new homes were brownstones. Known to geologists as arkosic sandstone, brownstone is a sedimentary rock that formed in the Late Triassic period—some two hundred million years ago—from alluvial grains of silica, quartz, feldspar, and mica. Over time these particles were cemented together, hardened, and tinted pink by an iron oxide known as hematite. Brooklyn brownstone came first from quarries at Belleville and Newark, New Jersey, that mined the Passaic Formation, a belt of bedrock that arcs up from Pennsylvania across the tristate region. Another source was Portland, Connecticut, across the Connecticut River from Middletown, where as many as fifteen hundred men labored in vast quarry pits reminiscent of a Piranesi etching. Mined, cut, and dressed, the chocolate rock was loaded on river boats like the Brownstone bound for Red Hook and Gowanus Creek. The somber stone appealed to a nation in mourning, an era that Lewis Mumford memorably termed the “Brown Decades.” “The Civil War shook down the blossoms and blasted the promise of spring,” he wrote; “The colours of American civilization abruptly changed . . . browns had spread everywhere: mediocre drabs, dingy chocolate browns, sooty browns that merged into black. Autumn had come.” The brownstone townhouse was the archetypal dwelling of an era both melancholic and yet replete with new freedoms and national renewal—and heady economic growth. By 1868 the war-stilled economy roared to life again. New York’s population doubled between 1860 and 1890; Kings County’s tripled. The homes came in a variety of flavors following the rise and fall of architectural fashion—Greek revival, Italianate, Second Empire, Romanesque, even Gothic. Builders were mostly small and speculative, erecting homes in gangs of three or four, sometimes filling an entire block. Brownstones were expensive at first, but mass production soon brought costs down. Forged metalwork was replaced by cast iron poured into a variety of ornamental molds by manufacturers like G. W. Stilwell’s Phenix Iron Works. Terra-cotta replaced carved stone; handworked wood trim was cut instead by mechanized planers, routers, and lathes. Even the price of the namesake stone fell, as steam-powered derricks and saws reduced the labor needed to quarry and cut the rock. By the 1880s, a building material once associated with great wealth had moved within reach of a middle-class budget.2

Quarry walls, Portland, Connecticut, 2018. Most of Brooklyn’s brownstone came from this flooded mine on the Connecticut River, now the Brownstone Exploration and Discovery Park. Photograph by author.

One of the ironies of the Brooklyn brownstone is that, on nearly all such buildings, the celebrated rock is only skin deep—chocolate frosting on brick-and-timber cake. This was hardly meant to be deceptive, at least at first; references in the Brooklyn Eagle in the 1850s are almost always to “brown-stone-front houses.” Even the grandest such structures made no bones about their brick bodies. The plain side wall of Two Pierrepont Place in Brooklyn Heights—recently listed for $40 million, the highest ever for a Brooklyn house—can easily be seen from the street. But as brownstones slid down the economic food chain, class-fretful buyers needed their buildings to make ever more bold statements of status and upward mobility. Builders cranked up the aspirational quotient with motifs redolent of poshness and exclusivity—mammoth cornices, doors so massive they could crush a child’s skull, elephantine cast-iron railings, windows big enough to let all passersby see the tasteful appointments within. The fact of the cladding was itself muted. By the 1880s, references to brownstone as mere façade material become scarce. The earnest “brown-stone-front house” is dropped for a speedier shorthand—brownstone—a subterfuge of omission that effectively extended the prestigious stone to the entire building. Material had become metaphor. In both the Eagle and the New York Times, use of the solo “brownstone” was rare before 1890 but jumps afterward, while two-step “brown stone” largely disappears from the Times by 1885—just as the most frenzied period of brownstone construction gets under way. Of course, not everyone fell for all this posture and stagecraft. Once he hopped off the el for a closer look, Julian Ralph found Brooklyn’s brownstone row houses to be “deceptive, fraudulent, pretentious—mere shells—plated, so to speak, with a coating of brown stone in front and trimmed inside with cheap pine stained like mahogany, so that a poor man may boast a brownstone house . . . so that the clerk may live like the shadow of a millionaire.”3

Brooklyn’s long brownstone afternoon ended almost in the blink of an eye. The cause was a change in architectural tastes brought about by the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Its planner, Daniel Burnham (whom we met in chapter 10) handed nearly all the plum building jobs to an elite band of architects trained in the neo-classical manner at Harvard, MIT, and the École des Beaux-Arts. They built an ersatz Roman Forum so brightly illuminated by Edison’s new lightbulbs that its glow could be seen a hundred miles away (consuming three times the electricity of all Chicago each night). Burnham’s White City burned away Mumford’s shades, ending America’s long brown day of bereavement. In Brooklyn, very few brownstones were built after 1900. All the rage now were bowfront Renaissance-revival townhouses dressed in white limestone or yellow brick. Demand for the chocolate rock tumbled. The Portland quarries mined $575,000 worth of stone in 1890; by 1908 that figure had fallen to just $56,000. And the city was in the midst of a major building boom at the time! The Newark quarries were abandoned by 1913; those in Portland limped on until a storm-swollen Connecticut River flooded the two-hundred-foot-deep pits during the Great Hurricane of 1938 (the site is now the Brownstone Exploration and Discovery Park). Of course, the brownstone has roared back from the nethers of taste and fashion—a process that began in the 1960s as well-educated young progressives discovered in the soot and grime of old Brooklyn refuge from the anomie and consumerism of Cold War America. Today the Brooklyn brownstone is among the most cherished forms of habitat this side of the Atlantic, and a symbol of the borough as iconic as the Brooklyn Bridge or the parachute jump—perhaps more so. When Absolut Vodka sought a design for the Brooklyn edition of its popular city series, it passed over both landmarks for a brownstone façade (Big Ben was selected for London and the Golden Gate Bridge for San Francisco—not bad company for a house). And though the Brooklyn Bridge may have been sold many times, it’s never been the focus of a bidding war like those unleashed whenever a choice brownstone goes on the market.4

Gotham’s next big building boom got under way in 1903. By the time it ended in late 1916, some 400,000 units of housing in twenty-seven thousand apartment buildings had been added to the city—fully 40 percent of all the apartments in New York at the time. “The new construction,” writes historian Robert Fogelson, “was enough to house the population of every American city except Chicago”—and enough, more crucially, to accommodate the continuing surge of newcomers from afar and abroad. The population of Greater New York more than doubled in the thirty years from 1890 to 1920, rising by 72 percent between 1900 and 1910 and by another 85 percent over the subsequent decade. And yet apartments were plentiful—with enough vacancies in 1909 to house the entire District of Columbia. In Brooklyn, the great tide of brick and mortar had mounted the crest of the moraine and appeared poised to head down the other side. But construction slowed as the situation in Europe worsened and America was dragged into another global conflict. By the time the United States entered the war in April 1917, housing demand in New York was fast catching up with supply. The cost of building supplies had nearly doubled between 1914 and 1919 as material was diverted to the war effort, forcing an end to almost all new construction. Soon much of the city was facing a housing shortage. Things were especially bad in Brooklyn, where the Eagle predicted in August 1918 a coming “famine in apartments” and warned that “never before in the history of the real estate market has there been such a scarcity of dwellings for rent.” Renters who had had the pick of the litter just a few years before were increasingly at the mercy of rapacious landlords. With the war’s end building construction stirred to life, as expected; but the recovery was brief. In all of 1919, just sixty-two apartment houses were erected in all of Brooklyn. The Joint Legislative Committee on Housing, headed by Brooklyn’s own Senator Charles C. Lockwood, heard testimony that it had become “well nigh impossible to procure apartments at any price; that families were doubling up; that the health laws of the City of New York were being violated.” The cause was twofold: soaring materials and labor costs and a shortage of capital. Money “was very much in demand,” writes Fogelson, forcing housers “to compete for loans with other builders, who needed money to put up theaters and other commercial and industrial structures, as well as other businessmen, who needed money to manufacture automobiles and other consumer goods.” What loans banks and insurance companies did extend to real estate ventures were substantially less than in the 1903–1916 boom years—falling from 70 to 75 percent of construction costs before the war to just 50 or 60 percent less afterward.5

Map of lots in Park Slope west of Grand Army Plaza, c. 1868. Park Slope developed rapidly once construction on the great park got underway. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

With housing in such short supply, landlords could raise rents with impunity. Some did so rapaciously; most were themselves struggling to keep up with mounting inflation, taxes, and fuel and labor costs. Rent strikes became common. In the prewar years, these had been small and largely limited to the Lower East Side. Now they spread throughout the city. On February 22, 1919, riots erupted in Brownsville when several thousand people gathered to protest the eviction of rent strikers at 1576 Eastern Parkway—and to battle desperate home-seekers who had rushed in to secure the vacated units. Three months later a crowd of five thousand converged to prevent the city marshal and furniture movers from dispossessing three families from a tenement at 387 Williams Avenue. Some strikes were successful. That September, a five-week strike by three thousand tenants near the Navy Yard ended when the B.F.W. Realty Company agreed to reduce a scheduled rent hike and make needed improvements. Joyous renters filled the streets to celebrate as news of the victory spread; “The red-lettered ‘Rent Strike’ signs that have been posted in every window, and hung from the shoulders of virtually every occupant . . . were flung into the gutter.” Most strikes failed, however, as the majority of tenants were too fearful of eviction to partake. Moreover, sympathy for the strikers slackened as anarchist bombings spread and “Red Scare” fears intensified. A threatened May Day action “of overwhelming proportions” in 1920 fizzled after it was condemned by the Brooklyn Tenants Protective Union, which professed “no sympathy with radical Bolshevism” (a promise from Mayor John F. Hylan’s Committee on Rent Profiteering that “any show of violence would be promptly crushed by the police” also played a role). The severe housing shortfall did nothing to foster unity across ethnic and racial lines. In May 1919 the American-African Colonization Association of New York approached the Brownsville Landlords’ Protective Association with an offer “to place a colony of 5,000 colored people in the vacant homes of evicted Brownsville tenants,” so long as the families were charged “a fairly reasonable rent” and given a five-year lease (“Another color for the Joseph’s coat of Brownsville’s population,” snarked the Eagle). The following summer, landlord Jacob B. Felman made good on a threat “to sell his property to negroes” in order to punish striking tenants at 1876 Douglas Street (Strauss Street today). Purchased by a black cooperative, the long-vanished building was the first in Brownsville to be owned by African Americans.6

As the housing shortage worsened and rent-strike fever spread, urgent appeals were made to city and state officials for help. When the state legislature convened in January 1920, it was flooded by nearly a hundred housing bills to penalize rent profiteering, slow evictions, and generally give tenants greater protections. Only a dozen of these bills eventually made it to Governor Al Smith’s desk, where they were signed into law on April 1. They represented, all told, “the most thorough overhaul of New York’s landlord-tenant laws in well over half a century.” But Smith, like many legislators, was unconvinced that landlord-tenant laws alone would do much to ease the crisis in New York. “On more than one occasion,” writes Fogelson, “he had stressed that the only way to bring down rents was to build houses”—that far more serious than the rent-strike emergency “was the lack of suitable workingmen’s houses, a longstanding problem that would not be solved by regulating rents or punishing landlords.” The city desperately needed to get builders building again. In a special session of the legislature convened by Smith that September, another flood of housing bills was submitted. Ten eventually passed, only one of which—an enabling act known as chapter 949 of the Acts of 1920—was aimed at stimulating residential construction. “Enacted over the opposition of owners of prewar apartment houses,” Fogelson writes, “the statute allowed the cities, towns, villages, and counties to exempt new residential structures other than hotels from property taxes until January 1, 1932”—so long as construction was completed after April 1, 1920, or begun before April 1, 1922, and finished within two years (or, if currently under way, done by September 27, 1922). In New York City, a first-round chapter 949 ordinance was hotly contested and, despite Mayor Hylan’s backing, ultimately defeated by the Board of Aldermen. A revised version, reported out by the Committee on General Welfare, also faced a stormy hearing but fared better, passing by a vote of 42 to 27. Promptly signed by the mayor, the ordinance went to the Board of Estimate, where it faced little opposition and became law on February 25, 1921. The city had wisely added several tweaks to the legislation as it came down from Albany. It limited the amount of the tax exemption to $5,000 to discourage production of high-end homes for the wealthy. In addition, it allowed the exemption to be taken only on a per-room basis ($1,000 per room up to five rooms), not carte blanche for an entire building. City officials “were more interested in securing housing for families than in providing expensive small apartments for individuals,” explained Mary Conyngton in the Monthly Labor Review, “so they linked the exemption to the rooms, and made sure that no one should secure the maximum remission unless he put up houses or apartments suitable for family use.”7

Chapter 949 fell like rain upon a thirsty garden. As soon as the tax-exemption statute was enacted in Albany, builders in the city began filing for permits—even before the local tax-exemption ordinance was passed in New York. Once it became law, the housing industry magically jumped to life. Lending institutions that had refused building loans now “opened their coffers,” wrote Edward Polak, “and money poured into the mortgage money market.” Builders idled for years suddenly had all the work they could handle. Wages in the building trades shot up; labor was back in demand, putting thousands of newly arrived immigrants and African American migrants from the South to work. Skilled laborers and craftsmen began flocking to New York from all over the United States. Dormant quarries, lumber mills, cement plants, and brickyards stirred to life again. Just four weeks after the ordinance was passed, plans were filed for more than 1,000 apartment houses, compared to a mere 190 in the corresponding period the year before. By Christmas, it was clear that a major building boom was under way. More dwellings went up citywide in just the ten months of 1921 following passage of the law than in the previous three years combined, while total expenditures on housing rose from $76 million in 1920 to over $260 million in 1921—an increase of 242 percent. And that was just the start. Construction outlays citywide from 1921 to 1923 were seven times those of the three years prior to the tax exemption. In 1924, a record-breaking 55,000 dwelling units were added to the city—not including single- and two-family houses. Manhattan, where almost nothing could be built unless something was first torn down, was relatively unmoved by the building boom. The real action was in the city’s still-rural outer boroughs; and nowhere was the frenzy of home construction greater than in outwash Brooklyn. Here, the Cartesian grid of metropolis, perched for a decade on the terminal moraine, rolled down now to the sea.8

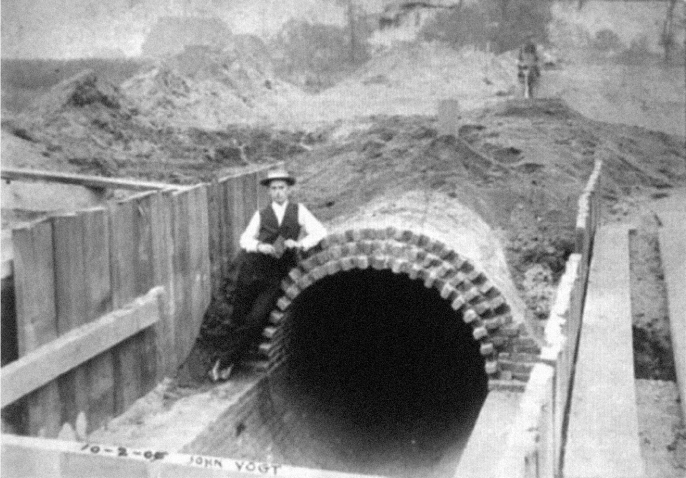

Land was plentiful and cheap in Brooklyn’s southern hemisphere, which was newly tapped into Gotham’s pale by extended gas, water, and sewer infrastructure—including a cloaca maxima across flood-prone Flatlands rumored to be the largest storm sewer in the world. The so-called Flatbush Relief Sewer was hailed “a triumph of engineering enterprise and skill” no less than the Holland Tunnel, then under construction. The big pipe was officially opened on June 9, 1926, by Mayor Walker in a ceremony at the intersection of Foster Avenue and East Twenty-First Street in Ditmas Park. Electricity set aglow a landscape long lit by candles and gaslight; when utility poles appeared on the southernmost reaches of Flatbush Avenue, the Eagle prognosticated “a brilliantly-lighted Broadway at night.” Dozens of trolleys and no fewer than four main subway lines—the West End, Culver, Sea Beach, and Brighton Beach—crossed the outwash plain, linking city to sea. Unlike Queens, Brooklyn was familiar ground to anyone who had been to Coney Island. Every year, millions of New Yorkers made their way over the outwash plain on day trips to the beach. Such warm familiarity—happy memories of outings with family and friends—only deepened the rosy glow of the City of Homes. As the boom got under way, the sleepy Bureau of Buildings—an all-Irish shop long stocked by Tammany Hall—was plunged into disarray. Architects awaiting permits or approvals railed against its “backward conditions” and “inability to cope with the growing number of building plans filed.” Bribes and hush money passed beneath tables, which might explain why superintendent Thomas P. Flanagan could afford to rent out the entire Orpheum Theater for a bureau staff bash in April 1923.9

Flatlands sewer main, c. 1905. James A. Kelly Local History Collection, Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

Builders could hardly keep up with demand, and suppliers were stretched to the limit. Kilns along the Hudson roared night and day to meet the incessant call for bricks. In mid-November 1924, some one hundred brick-laden barges appeared in Gotham’s waters, a terra-cotta armada that augured a wild building season to come (the brickmakers sent their wares downriver early to avoid being trapped by ice as the Hudson froze). All told, the fleet carried some forty million bricks—enough to cover 140 football fields or make it a fifth of the way around the equator if placed end to end.10 That year, construction outlays in the borough were $226 million—a figure that soared in 1925 to $258 million and to $286 million in 1926, the peak of the boom. By 1928, construction spending in the borough was down to $200 million, and shrank to a miserable $74 million in the year following the Wall Street catastrophe of October 1929. The scale and speed of homebuilding in the early 1920s was unlike anything the city had seen before, and drew inevitable comparisons to the speculative mania that gripped Florida at the time (“FLATLANDS SALES RIVAL MIAMI TALES,” cried the Eagle in 1925).11 But the Florida land rush was a bubble, burst by the 1926 Miami hurricane and leaving investors with little more than sandy building lots. For all its speculative fever, the Brooklyn housing boom left behind a vast legacy of well-built dwellings, homes for a generation of New Yorkers raised in the tenements of the Lower East Side and eager for a castle of their own.

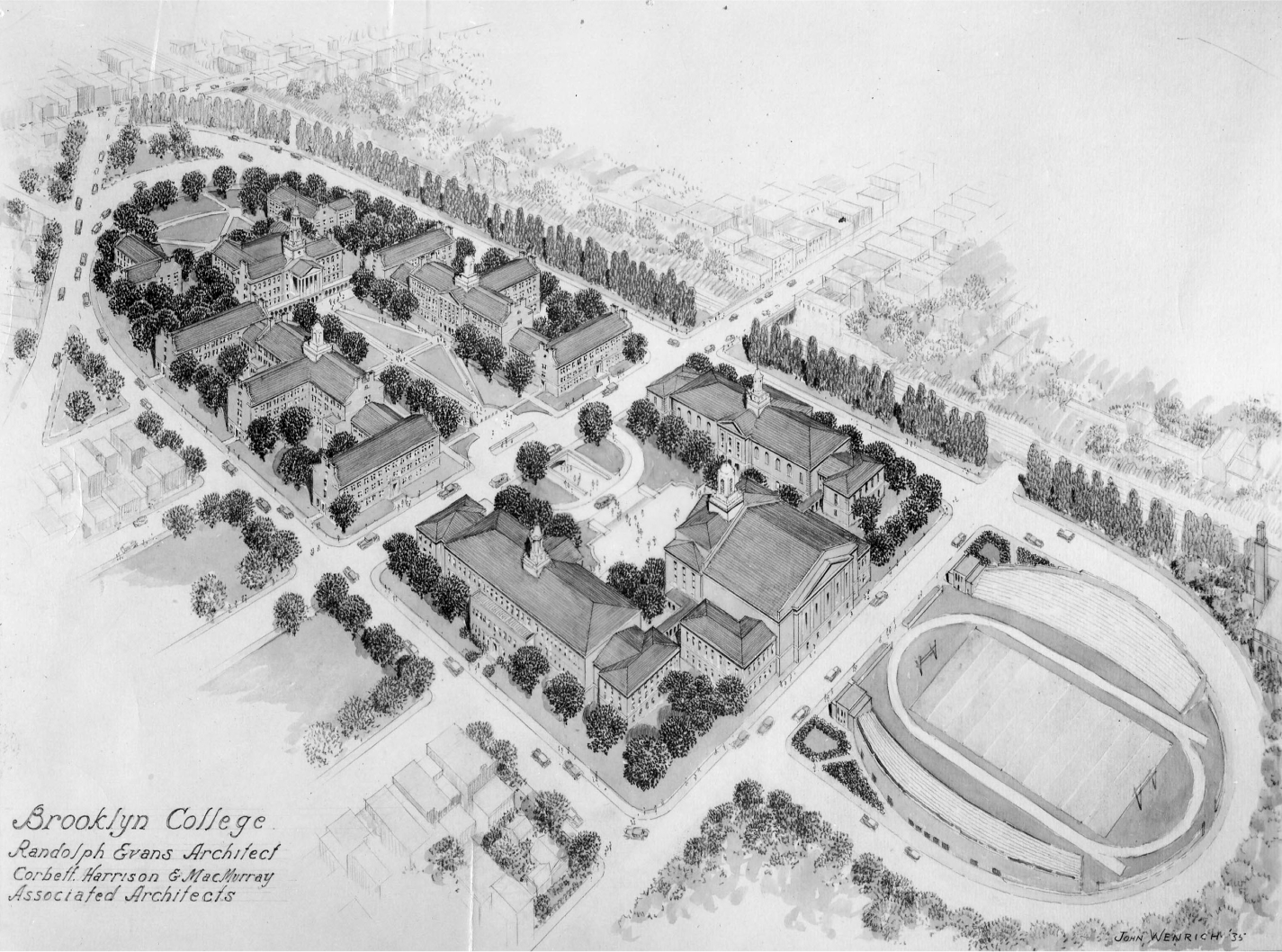

And castles of a sort they were. Buildings reify society’s yearnings as well as its fears, and the residential architecture of the 1920s did just that. The dominant styles then all harkened back to the colonial era or that putative motherland of America, Olde England. Gothic forms were slapped on everything from dormitories to skyscrapers. The neo-Georgian became a style of choice for civic buildings—the Museum of the City of New York and Brooklyn College, for example. A national craze for clapboard colonial-revival homes was set off by Colonial Williamsburg, itself dedicated to a carefully framed set of American traditions. Sears Roebuck marketed mail-order houses named the Lexington and the Jefferson, and was even commissioned to erect a full-scale replica of Mount Vernon above the lake in Prospect Park. Landscaped with boxwoods salvaged from Washington’s Hayfield, Virginia, estate (planted by the pater patriae himself), the reproduction Mount Vernon was an initiative of Sol Bloom’s Washington Bicentennial Commission. Thousands of Brooklyn school-children were dragged through the clapboard shrine until Robert Moses removed it in one of his first official acts as park commissioner.12 But the most popular style of residential architecture in 1920s New York City reached even further back in time than colonial America—to Tudor England and its medieval vestiges. The Tudor era ended in 1603, decades before the settlement of New Amsterdam. But its architectural traditions lingered on long enough to touch the New World shore, leaving us several extra-ordinary late-medieval examples on the Atlantic Seaboard—Bacon’s Castle in Virginia, for example, and the Judge Corwin and Fairbanks houses in Massachusetts.

Perspective rendering of replica Mount Vernon in Prospect Park, 1932; William Smedley, architect. The building was constructed under the auspices of Sol Bloom’s George Washington Bicentennial Commission. Brooklyn Daily Eagle photographs, Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

What led to all this rifling through the Anglo-architectural attic? As we saw in chapter 3, the country was changing, and many feared that its white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant charter culture was under siege. For all the progress of the 1920s, it was a conservative, even reactionary decade. The wholesale slaughter of the Great War was still a fresh scar; so too the flu pandemic of 1918. The Russian Revolution sparked fears of Bolshevism, and Prohibition took away the succor of drink. And then there was the matter of immigration. A great tide of newcomers—from Europe and Asia as well as the American South—was rapidly transforming the racial, ethnic, and religious composition of the nation’s cities. A hydra-headed nativist movement pushed back hard with violence and intimidation. The Ku Klux Klan was revived as a political force potent enough to hijack the 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City. Scarier still were pseudoscientific racists like Madison Grant, a Yale-schooled aristocrat and pioneering environmentalist who, like Newell Dwight Hillis, became a committed eugenicist. Grant’s 1916 paean to Nordic supremacy, The Passing of the Great Race, was a best seller that helped bring about the draconian immigration laws of the 1920s—including the National Origins and Asian Exclusion acts. Related fears of cultural diminution led Congress to establish the Washington Bicentennial Commission in 1924 (that its chair was a Jewish son of immigrants is a delightful irony). Nominally charged with planning a two-hundredth-birthday bash for George in 1932, the commission’s whispered mission was to help cleanse all those immigrants from Sicily and Galicia of unsavory political notions—to impart a bundle of American values to help them “come to understand our principles of liberty . . . our scheme of government.”13

John Wenrich, perspective rendering of Georgian-revival Brooklyn College campus, 1935; Randolph Evans with Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray, architects. Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

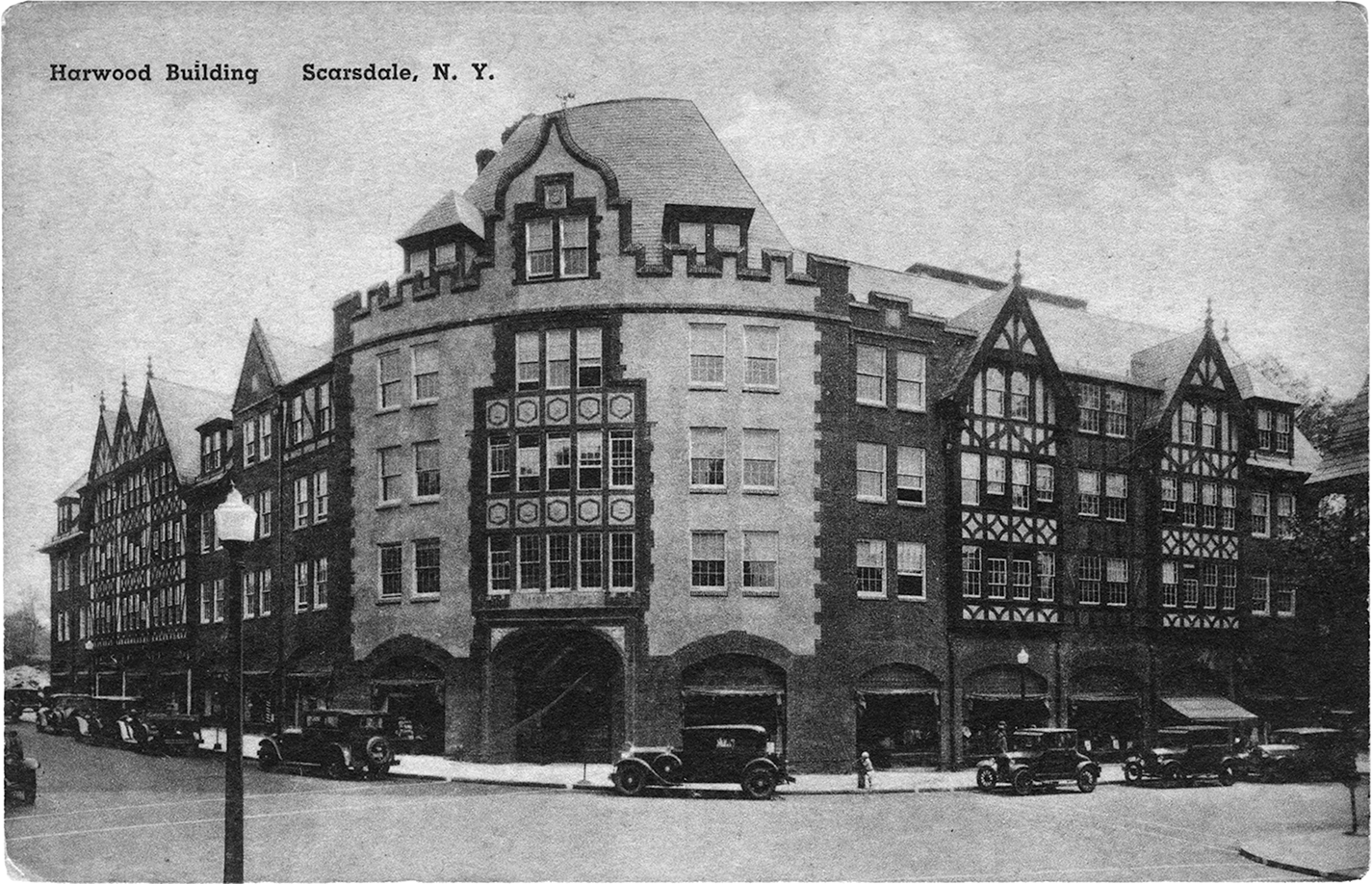

As with the colonial and Georgian styles, the Tudor revival—Tudorism for short—was likewise born of fears that America’s charter culture was weakening in the face of vast immigration. It was “a style for the WASP,” writes Gavin Townsend, “a fortress symbol of established Anglo-American lineage at a time when Poles, Slavs, Italians and other ‘undesirables’ were seemingly flooding the country.”14 Tudorism gained a first foothold in New York around 1910 and quickly became a popular style for single-family homes in the city’s posh, lily-white commuter suburbs—Forest Hills Gardens, Bronxville, Riverdale, Scarsdale, Tuxedo Park. It was thus perfectly positioned to spread far and wide with Gotham’s next building boom. And the development frenzy unleashed by the tax ordinance did exactly that—it transformed the still-rural landscapes of southern Brooklyn into a stage-set Camelot of steep gables and half-timbered walls, battlements, turrets, and jerkinhead roofs. By the end of the 1930s, the Tudor-revival row house had become as ubiquitous a feature of Brooklyn’s trollyburbs as the Victorian brownstone was of the nineteenth-century neighborhoods north of the moraine. But the politics of the style had changed. In Brooklyn and Queens, Tudorism was an architecture of aspiration, not revanchist yearning for some dewy Anglo past. A style born of xenophobia thus became popular with the very “undesirables”—Jews, Italians, Irish—whose coming helped spawn it in the first place. Trolleyburb strivers were drawn to the Tudor style because it signaled arrival, because it endowed working-class streets with a tiny bit of the polish and grace of Westchester. They were assimilation engines of a sort. The architects and builders of the homes—many of whom were themselves Jewish, Italian, Irish, or Polish—understood well this symbolism. They became expert at distilling the essence of a Riverdale or Bronxville Tudor mansion down to the scale of a small city lot, transforming, in the process, a style for the elite into one for the masses. Thus did “Banker’s Tudor” of Scarsdale and Tuxedo Park beget “Teller’s Tudor” of Bay Ridge, Flatbush, and Borough Park.

Postcard view, Tudor-revival Harwood Building, Scarsdale, c. 1928. Scarsdale Historical Society.

Erecting most of the new homes—single-family dwellings and apartment buildings alike—were scores of relatively small builders. A full accounting of these forgotten shapers of outer-borough New York would fill a telephone book. Louis H. Bossert erected five hundred houses at Utica Avenue and Avenue N; Samuel Bern-stein’s Lezbern Building Company built forty-two homes on East Twenty-First Street and Neck Road in Gravesend; the oddly named Endocardium Company was active in the vicinity of East Fifty-Second Street and Avenue M in Flatlands. Hyman Selkin built on Flatlands Avenue, Louis Carnadella in Bay Ridge, Louis R. Goldin at Foster Avenue and East Forty-Fifth Street, the Dahl Development Corporation at delightful Dahl Court in Gravesend, the Filloramo Brothers on Avenue D and East Forty-Eighth Street. E. H. Fritchman’s memorably named UONA Home Corporation erected dozens of gumdrop Dutch gable frame houses in Marine Park; the Tudor Homes Corporation focused on nearby Haring Street and Avenue U, and the Wengenroth Company at Avenue T at East Thirty-Sixth Street. Many of these builders slipped under the waves once the Depression got under way. One was Lawrence “Lorry” Rukeyser. Born in Milwaukee to a large family of Jewish immigrants from Liepāja, Latvia (then part of the Russian Empire), Rukeyser made—and lost—a fortune in the construction industry before delving into residential real estate. In 1918, he and partner Generoso Pope—future publisher of the Italian-language daily Il Progresso, who helped make Columbus Day a federal holiday—bought out their struggling employer, the Manhattan Sand Company, hit hard by the World War I building slump. Rebranded Colonial Sand and Stone, Rukeyser and Pope’s company rode the crest of the 1920s building boom. They supplied gravel, sand, and concrete to thousands of building sites throughout the metropolitan area, from apartment buildings on the Upper West Side to vast row-house projects in Brooklyn and Queens—even the foundation for Yankee Stadium and the runways of Floyd Bennett Field (Rukeyser’s daughter, poet and feminist icon Muriel Rukeyser, recalled sneaking up to the rooftops of her father’s unfinished Manhattan buildings with her childhood friend from the Ethical Culture School J. Robert Oppenheimer, who would hold forth on physics as they lay beneath the stars). But the partners began clashing, and Pope—long cozy with mobsters—forced Rukeyser out of the business sometime in 1928. With his vast knowledge and contacts in the building industry, Rukeyser was able to jump quickly into the real estate game on the Flatlands frontier. His Laurye (a portmanteau of his own name) Homes Corporation played its biggest hand in booming Marine Park, where, as we saw in chapter 11, a long-promised playground the size of Central and Prospect parks combined had seeded a frenzy of speculative residential development. Rukeyser had big plans for the Laurye venture, with more than 165 “English Tudor Homes” projected for the blocks in and around East Thirty-Third Street and Fillmore Avenue. The Brooklyn Eagle described it as “one of the largest developments of its kind in the history of Brooklyn.”15

Tudor-revival row houses on northeast corner of Avenue R at East Thirty-Third Street, 1929. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

To create his Tudor microcastles Rukeyser chose a Jewish immigrant named Philip Freshmen, whose family had fled the Pale of Settlement first for London and then East New York. Freshmen was by any measure a successful architect, hobnobbing with Irwin S. Chanin, the celebrated apartment designer. Freshmen’s commissions included apartment buildings and a hospital in the Bronx, the “perpendicular gothic” Insurance Building at Clinton and Joralemon Streets in Brooklyn Heights, and the original home of St. John’s College School of Law at 56 Court Street. But like many designers working the busy plains of outwash Brooklyn, Freshmen was quite literally on the margins of a patrician profession dominated by Ivy league elites. And though he did solid work for Rukeyser—Freshmen’s houses are among the most sought-after in Marine Park today—the builder’s luck ran out even as his bricks were being laid. Less than a year after Rukeyser struck out on his own came the stock market crash of October 1929. Home sales weakened in 1930 but picked up the following summer, a false dawn that encouraged Rukeyser to forge ahead with his Laurye Homes venture. And then came the fall. In September 1931 the Eagle reported an ominous “sharp decline” in plans filed at borough building departments. Home sales faltered and then plummeted as the Great Depression spiraled toward its 1933 nadir. Breadwinners lost their jobs; life savings vanished as more than ten thousand banks failed nationwide. By mid-October, foreclosures had become “so common,” reported the Eagle, “as to constitute a menace to a real estate world already lacking in confidence and a very real peril to a vast list of other securities.” Some 128 foreclosed properties in the city were sold in a single week that month, representing nearly $5 million in value. Desperate to sell his remaining Laurye Homes, Rukeyser contacted the Andrew Cone General Advertising Company, a prominent agency whose biggest account at the time was the Empire State Building. Cone ran a series of catchy ads for Rukeyser in the Brooklyn Eagle in the fall of 1931. It was money thrown to the wind: the houses failed to sell. He couldn’t pay his contractors and before long was being slapped with mechanic’s liens from roofers, masons, and carpenters; adman Cone, meanwhile, hauled Rukeyser into bankruptcy court for an unpaid $870 bill. The next year was worse. Homeowners who had purchased on credit before the crash began defaulting on loans from the New York Title and Mortgage Company, which Rukeyser had backed as a guarantor. By August 1932 the homebuilder had racked up more than $2.2 million in liabilities, a staggering sum for the Great Depression.16

A Colonial Sand and Stone Mack mixer on a building site, c. 1939. American Truck Historical Society.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle advertisement for Lawrence Rukeyser’s Tudor-revival “Laurye Homes” development, East Thirty-Third Street in Marine Park, 1931.

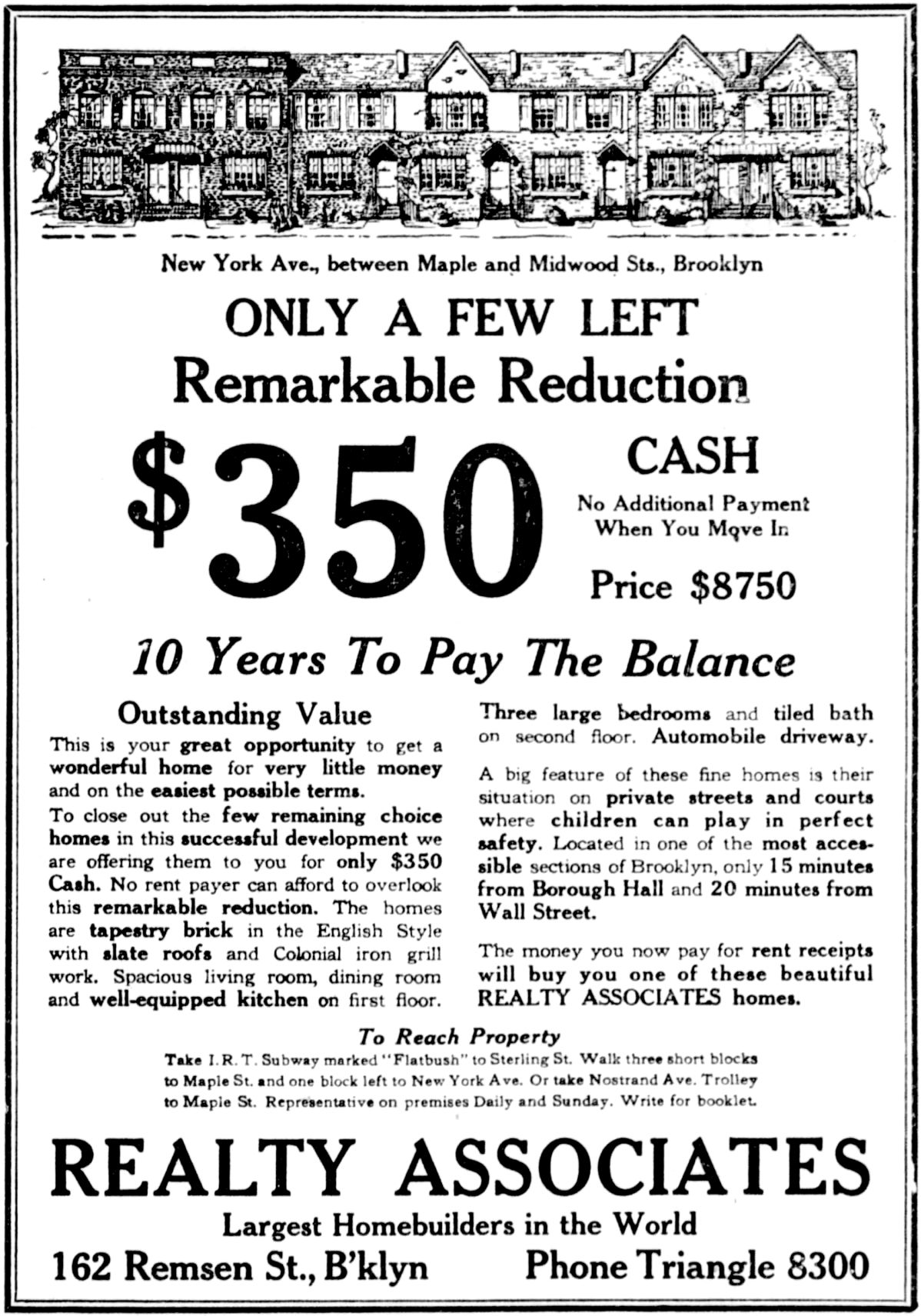

Rukeyser was, in the end, small potatoes compared to some players in Brooklyn real estate. One of the first and largest on the scene was Realty Associates, founded in 1901 “to deal in realty,” explained director Charles R. Henderson, “and to buy improved real estate in Greater New York on a considerable scale.” Unlike most builders in the 1920s, Realty had learned the trade in the previous building boom. Anticipating construction of the BMT Fourth Avenue subway, the company bought the old Backhouse farm in New Utrecht in 1905, laying out streets, installing sewer, water, and gas mains, and platting out some five hundred building parcels near today’s Maimonides Medical Center. They erected “semi-suburban” two-family row houses in Borough Park, glorious rows of bantam bowfront limestone and brownstone homes on Maple and Midwood streets in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens (for “families who want an entire dwelling without being under the necessity of keeping servants”), semidetached houses on Sullivan Place in Crown Heights and Vista Place in Bay Ridge, and a battery of tenements in Sunset Park for workers at Bush Terminal (which had already assumed “the character of an immense foreign colony,” fretted the Times, what with all those “Italians and Russian Jews”). By 1909 the company had some two thousand lots and six hundred buildings in its portfolio, with a rent roll of fifteen hundred tenants. Realty’s tactics were not always aboveboard. In 1916 it was accused of having “made it a practice for years to create sentiment in favor of the City of New York acquiring properties owned or controlled by them for one purpose or another.” That year, Realty director William M. Greve managed to convince the US Department of War to purchase a large parcel it had leased on Rockaway Point (from unlikely owner Southern Pacific Railroad) for a coastal defense installation—the future Fort Tilden. He would later be hauled before the Senate Finance Committee for shorting stocks via a barely concealed Italicized front called Greva Compagnia, and in 1938 caused a scandal by renouncing his American citizenship and emigrating to Liechtenstein, where his vast fortune was safe from the tax man.17

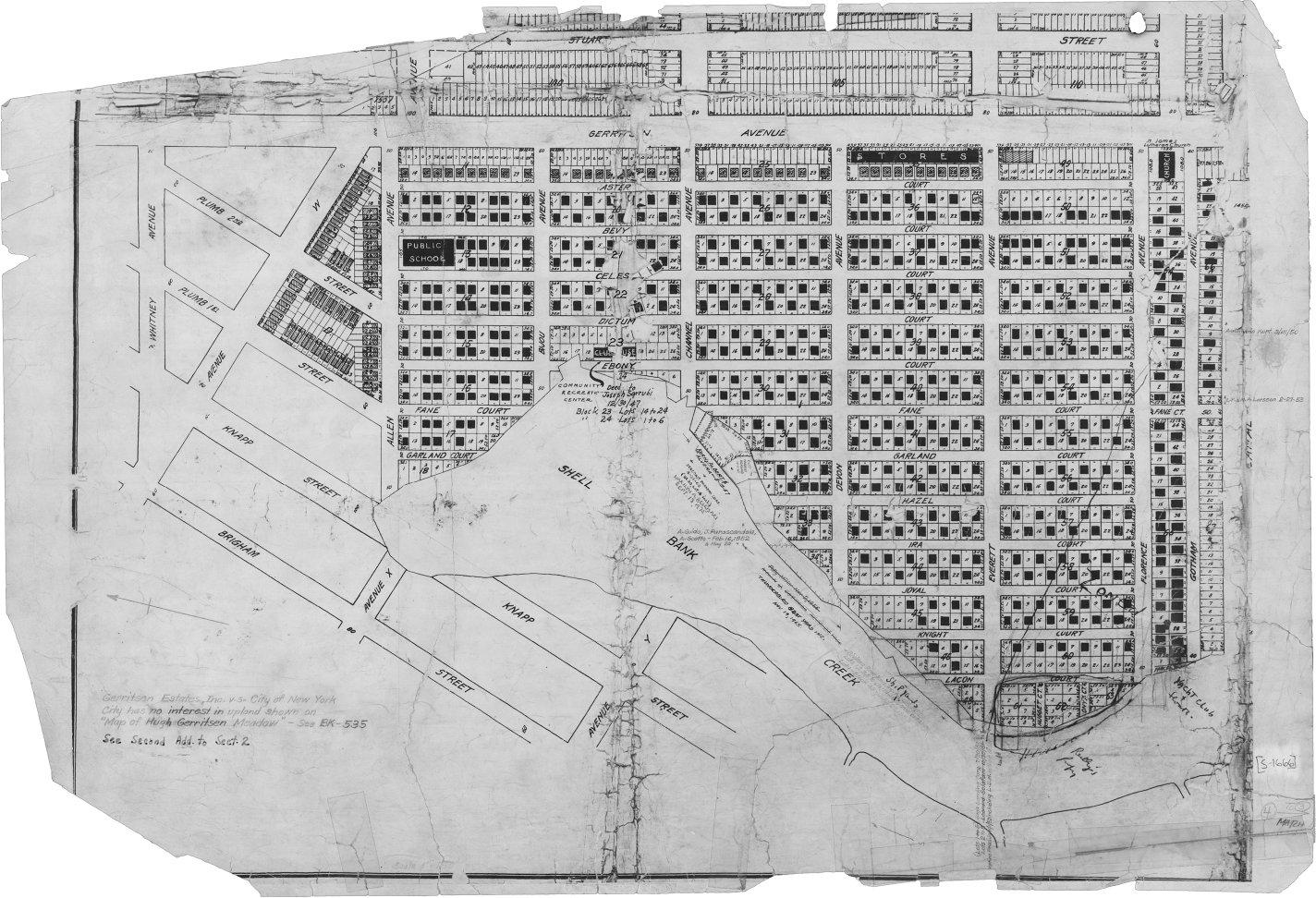

Plan of Gerritsen Estates, c. 1922. New York City Municipal Archives.

That wealth came largely from the thousands of single-family homes Greve erected as president of Realty Associates in the 1920s. His largest single project, launched in the fall of 1922, was a sprawling community of kitten-cute bungalows at Gerritsen Beach, on a spit of filled land along Shellbank Creek. Greve declared that the homes would be built “on the same principle that Henry Ford had developed his automobile—that is, on the basis of strictest economy through standardization of plans.” In this, Realty Associates may well have been the first firm in the United States to mass-produce homes, anticipating by a good twenty years an approach that William J. Levitt perfected at Levittown after World War II. Houses were trucked in from the old racetrack rail spur, “all in parts, sashed and ready to be erected over the concrete-cellared foundations.” A corps of five hundred laborers erected two dozen of the kit dwellings a month, and by September 1924 some six hundred houses were ready for occupancy at Gerritsen Beach—stick-built boxes on the shifting sand, set in twelve-packs on small blocks (about a third the size of those typical elsewhere in New York City). The houses came in five architectural flavors—all with roughly the same floor area and none costing more than $5,750 (a mere $80,500 today). To emphasize their affordability, Greve advertised the homes as “Ford Houses.” When Henry Ford found out about this, he threatened to sue Realty Associates for trademark infringement. Unfazed, Greve simply substituted his own name and kept on building. All told, some fifteen hundred “Greve Houses” were erected at Gerritsen Beach. The company offered its own financing, too; on a $4,950 house, buyers could close with a mere $350 down and a monthly installment of about $65—less than renting. The instant village shot from zero to five thousand residents in eighteen months. It had its own water plant, with 570-foot-deep wells, a 145,000-gallon storage tank, and five miles of water main; two churches—St. James and Resurrection; and a community clubhouse provided by Realty Associates (today the Tamaqua Bar and Marina). To meet the needs of its four hundred school-age children, the Board of Education hurriedly erected several portable school structures on Channel Avenue. All the buzz attracted other investors. By 1925, two dozen shops and stores were doing business on its main drag, while celebrated Brooklyn restaurateur Nicholas Satersen commissioned none other than William Van Alen—Brooklyn-born architect of the Chrysler Building—to design a fifteen-hundred-seat “moving picture theater and dance palace” for the corner of Cyrus and Gerritsen avenues. A victim of the Depression, it was never built.18

Long before Levittown: William Greve’s “Ford Houses” at Gerritsen Estates, 1924. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Isolated on the remote margins of the metropolis, linked for years to the rest of town by a single bus line, Gerritsen Beach developed a social fabric as tightly knit as its streets. It had an active civic association, its own chamber of commerce, a Lily of the Valley Garden Club that held annual contests, even its own elected “unofficials”—mayor and cabinet, park commissioner, and commissioner of public welfare. When the city claimed it had no money to deal with a massive sewage backup in Shellbank Creek, the community organized a “pick and shovel army” to cut a six-foot channel across the Plum Island sandbar to Rockaway Inlet, allowing tidal action to flush the waters. Of course, insularity also encouraged illicit deeds; a tight-lipped community with streets dead-ended at the waterfront attracted rumrunners during Prohibition. After a shootout with bootleggers at the foot of Devon Avenue in August 1931, police seized a load of thirty-five hundred bottles of whiskey (twelve hundred promptly vanished as the cops helped themselves to the loot). But the people of Gerritsen Beach took care of their own, forming a Citizens Protective Committee, agitating for emergency milk deliveries during the Depression, and raising money for neighbors in need. Though badly battered by Hurricane Sandy and spoiled by teardowns and mammoth additions, Gerritsen Beach has retained much of its original scale and charm, with perhaps the most picturesque street names in all New York—Melba, Ebony, Dare, Opal, Joval, Dictum, Just. As late as the 1980s there were still commercial trawlers working out of Shellbank Creek, and chickens and horses on one street. Guarded by Brooklyn’s last volunteer fire department, Gerritsen Beach remains an extraordinary urban village, a dash of working-class Hibernia on the edge of Gotham.19

Aerial view of Shellbank Creek and Gerritsen Beach, looking north from Rockaway Inlet, c. 1929. The Belt Parkway runs along the isthmus in lower half of photo (Plum Beach). Photograph by Air Map Corporation of America. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

Greve kept refining his copyrighted Gerritsen Beach model houses and in the summer of 1925 rolled out a larger version—the “Greve S” type—a dwelling “suitable for standardized construction in great quantities.” Realty erected a test batch of sixteen on the 3700 block of Quentin Road before building the houses en masse at its Stewart Manor community in Garden City. That December, as work on Gerritsen Beach neared completion, Greve clinched a $3 million deal to buy Brooklyn’s last working agricultural landscape—the Flatlands spread settled more than two centuries earlier by Johannes H. Lott. The land was still in the same family, sold to Greve by Jennie M. Suydam—Lott’s great-great-great-granddaughter—who retained only a small plot for the Hendrick I. Lott house itself. A once-vast plantation was now down to less than three-quarters of an acre. Ella Suydam, Jennie’s daughter, would live in the house until her death in 1989, and the property remained in the Suydam family until purchased by the Historic House Trust on behalf of the New York City Parks Department in 2002.20 All told, the Lotts and their descendants owned their land for almost 285 years. Where Hendrick’s slaves once hoed beans and corn, Realty Associates conjured forth a vast crop of houses. The company graded in miles of cinder streets, laid in a full complement of utilities, and subdivided the new blocks into thousands of lots. Greve christened the new community “Flatbush Centre,” and began erecting yet another variant on the “Greve” series, six- and seven-room “duplex and simplex” dwellings that sold for as little as $5,500. Still known in the area as “Realtys,” the modest little houses have been spared the teardown tide sweeping across Midwood and other neighborhoods—for now, at least. They remain among Brooklyn’s most affordable houses, home now to three generations of New Yorkers and blighted only by the unfortunate conversion of most front yards into carports. Over the next few years, Greve built Realty Associates into a booming conglomerate. The company broke its own sales records in 1925 and again in 1926, selling more than two thousand homes in two years (at one point brokers were moving ten houses a day). Not one for understatement, Greve began billing his company as the “Largest Homebuilders in the World.” He may very well have been right.21

Realty Associates advertisement for row houses with “tapestry brick in the English Style” on New York Avenue in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens. From Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 1926.

Another major Brooklyn builder in the interwar period was the man who gave us daylight saving time and divided the nation into standard time zones—US Senator William M. Calder. Scots-Irish son and grandson of carpenters, Calder grew up on Thirteenth Street in Park Slope and got his start in the building trade working alongside his father as a teenager. He took evening classes in architecture and engineering at Cooper Union and by the 1890s was erecting substantial homes in Williamsburg and Park Slope.22 Drawn to politics at an early age, Calder became active with the Young Men’s Democratic Club and the South Brooklyn Board of Trade, serving on its Committee on Streets and Paving. In 1900 he helped incorporate the Republican Club of Brooklyn’s Twelfth Assembly District and one year later was appointed superintendent of buildings by Brooklyn Borough president J. Edward Swanstrom. Cheering the choice, the Eagle described Calder as “an experienced builder, an honorable citizen, a man of excellent judgment.” When Calder reported to his new office, he found his desk buried under floral tributes from bureau employees worried about their jobs, including an immense horseshoe of roses from the building inspectors. As feared, he promptly began whipping the bumbling bureau into shape. Flowers notwithstanding, Calder fired five inspectors in the first week—part of his plan to “drop undesirable material from the payrolls.” He admonished staffers to be “polite and courteous in your treatment of the public,” but jealous in the pursuit of compliance and the law. There were new rules for them, too: “Drunkenness will not be tolerated,” Calder warned; “To enter a saloon in uniform I will consider a gross breach of the rules. I want you to come here mornings cleanly shaven, shoes shined and with your uniforms carefully brushed.” Fire safety was of particular concern to Calder; he banned smoking in the bureau offices, beefed up fire codes for theaters, upgraded tenement fire escapes, and inspected the ruins of a disastrous fire in Atlantic City in April 1902.23

His diligence averted at least one tragedy at Coney Island. Shortly before Calder took over as chief, the buildings department had issued entrepreneur Herman O. Moritz a permit for an “aerial coaster” at the Bowery and Kensington Walk. Calder refused to allow Moritz to operate his ride until several safety improvements were put in place. On June 12, 1902, with Coney’s summer season wide open, Calder’s inspectors arrived to check the ride for approval. After running the empty cars around the track several times, the inspectors boarded to make sure the structure could handle a live load. The car was being winched to the top of a steep incline when the clutch on a sprocket chain gave way, sending the vehicle hurtling down and into Moritz, who was thrown from the track and killed. Coincidentally, Calder played a signal role in bringing a boardwalk to Coney Island. Such an amenity—a “board sidewalk like Atlantic City’s”—had been proposed for the beach as early as 1893. A Coney Island Board Walk Association, formed in 1900 by George C. Tilyou and others, tried to build the improvement privately but was opposed by property owners who refused to grant the necessary easements. Edward Marshall Grout—Brooklyn’s first borough president and champion of the ill-fated Jamaica Bay port scheme—took up the issue as a way the city might reclaim a waterfront “almost entirely usurped by private parties.” But he, too, was defeated by amusement operators expected to help pay for the improvement. The breakthrough came in early 1903, when Calder discovered on topographic maps a long-forgotten street created by the old town of Gravesend, just south of and parallel to Surf Avenue. He proposed that this “Atlantic Avenue” right-of-way be used to construct “a board walk along the ocean front,” and to extend to it all streets “now terminating at Surf Avenue”—precisely the configuration eventually realized some twenty years later.24

Calder’s term as Brooklyn’s top building official ended in December 1903, allowing him to get back to his business of brick and mortar. Working on a huge tract on the western edge of Prospect Park, Calder ultimately erected some nine hundred homes in Windsor Terrace, described by the Eagle as “one of the most successful home communities in the country,” and referred to as Calderville into the 1970s. Many of the homes, such as the bowfront Renaissance-revival row houses at 159–189 Windsor Place, were designed by architect Thomas Bennett, a friend of Calder’s who had served as his deputy superintendent at the Department of Building. But politics kept calling. In November 1904 Calder was elected to the US Congress from the Sixth Congressional District; he served for a decade before seeking nomination to the US Senate. Defeated in his first bid, Calder succeeded in 1916, besting his Democratic opponent by 250,000 votes. Calder’s senatorial term would hardly be remembered today but for a wartime bill drafted by the National Daylight Saving Association (NDSA). The idea of moving the clocks ahead in spring and back again in fall to make better use of daylight was an old one, and had already been adopted in England and Europe. Benjamin Franklin is generally credited with having first hit on the idea in 1784 while in Paris. Coordinating the workday with the sun, he reasoned, would dramatically reduce the need for artificial light. He rather wildly estimated that Parisians could save sixty-four million pounds of wax, simply “by the economy of using sunshine instead of candles”! But the United States was slow to adopt the idea and struggled even to create standardized time zones (the railroads had established a four-zone system in 1880s, but it was never officially adopted). Led by the NDSA, a national daylight saving movement gathered as the United States entered the Great War. Advocates argued that the added hours of natural light would not only reduce coal consumption, but make more time for healthful recreation and increase food production by giving home gardeners an estimated nine hundred million additional hours nationwide to weed and hoe. Calder and Representative William Borland, a Democrat from Kansas City, took up the cudgel, introducing to Congress the Calder-Borland bill. It was promptly passed by the Senate, approved by the House with amendments, and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on March 19 as the Standard Time Act of 1918. At two o’clock in the morning of March 31, the day the new law took effect nationwide, Brooklyn’s “champion of daylight saving” was handed the honor of setting forward the big clock below the cupola of Borough Hall.25

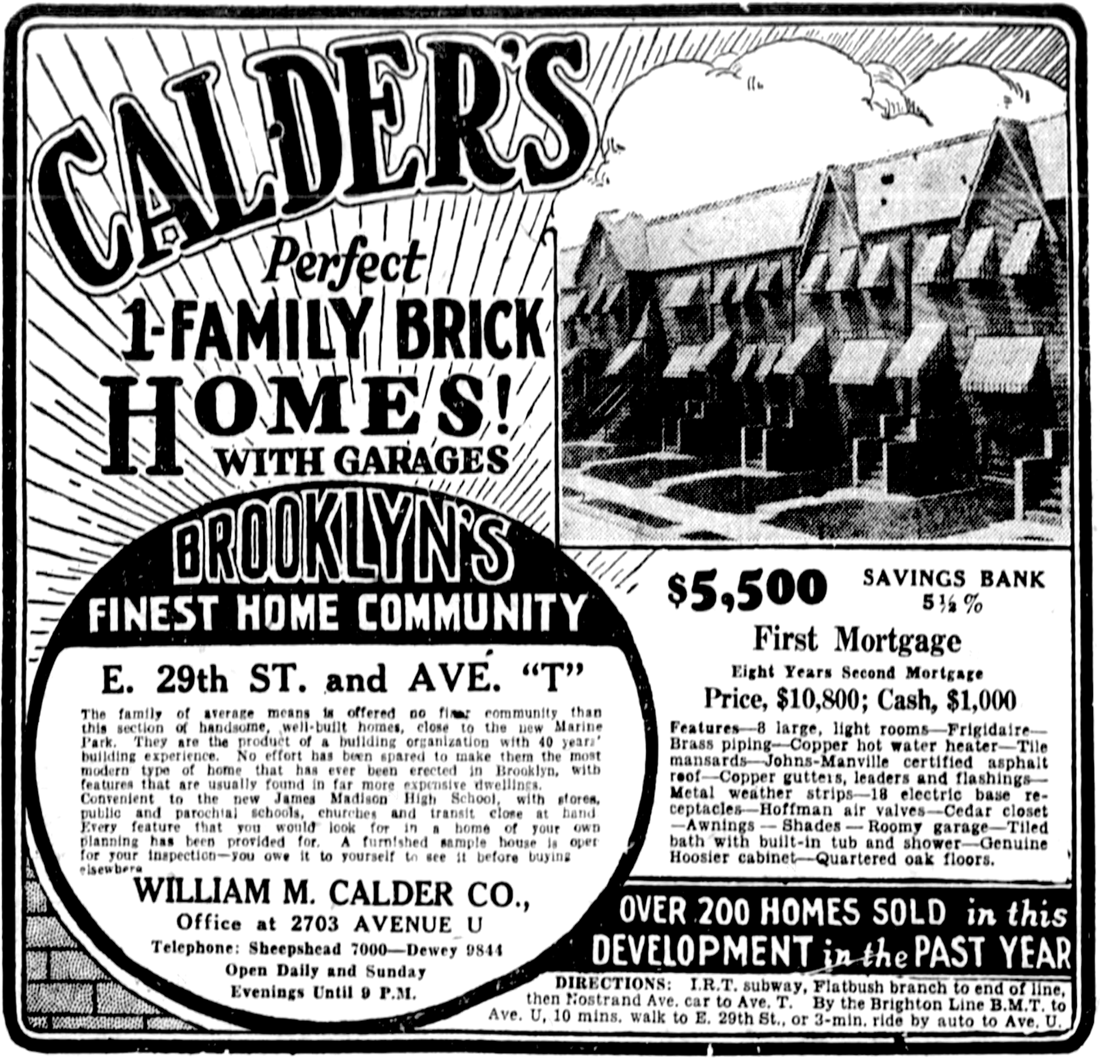

Calder’s timing was flawless. He was elected to the Senate just as the building sector crashed in New York, and—defeated for reelection by a homeopathic physician named Royal S. Copeland in 1922—got back to building just as Brooklyn’s greatest real estate boom got under way. Moving his office to Beverley Road, he focused on the borough’s newest development frontier—Flatbush and points south on long-rural outwash plain. By 1925 he had erected a phalanx of two dozen apartment buildings on Nostrand Avenue at Beverley Road, all the brick row houses on adjacent East Twenty-Ninth Street, and dozens more on Brooklyn Avenue, East Thirty-Fourth, and East Thirty-Fifth streets at Cortelyou Road. Moving south with the tide, Calder snapped up fifty lots on both sides of East Nineteenth between avenues Y and Z in Sheepshead Bay, working with architect J. A. Boyle to “duplicate as near as possible the Calderville development” at Windsor Terrace. By the time the market crashed in October 1929, Calder was the most prolific builder in Brooklyn, having erected some thirty-eight hundred homes across the borough. A deep reserve of cash enabled him to keep going through the Depression—for a while. “Stocks and bonds may go up and down,” he saged, “but a well built home and the soil beneath it remain to endure for generations.” Calder now turned to land just west of long-delayed Marine Park: “I feel confident,” he told a reporter in 1933, “that the completion of Marine Park will mean to Brooklyn what Central Park means to Manhattan.” Walking the talk, he rolled out here his most ambitious venture yet, relocating his office to 2703 Avenue U and building a colony of several hundred gable-spiked Tudor row houses—“Calder’s Perfect Homes”—on blocks in and around Avenue T just west of Nostrand Avenue. Designed by Calder himself with interior appointments by his wife, Katherine Harloe Calder, they included basement apartment suites, electric iceboxes, and gas-fired automatic furnaces (“Just think of the house,” he regaled, “where the heating plant is controlled by a thermostat”). The homes sported an even more seminal accessory: garages. By now, New Yorkers were falling fast for the automobile, especially in far-flung outer neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens beyond the reach of rapid transit and where trolleys were increasingly sluggish and overcrowded. Nationwide, passenger car registrations more than tripled between 1919 and 1929, from 6.8 million to 23 million. In Gotham, Brooklyn led the way, its busy Motor Vehicle Dealers Association holding annual motorcar shows at the Twenty-Third Regiment Armory in Crown Heights, which—as one Eagle wag put it—invariably triggered an outbreak of “Motorcargitis” in the borough. There were 150,687 automobiles registered in Brooklyn in 1927, highest of any borough (Manhattan had 106,723, followed by Queens with 96,799).26

US Senate sergeant at arms Charles Higgins turns the historic Ohio Clock forward an hour for the first Daylight Saving Time, March 1918. William Calder, sponsor of time-change bill, is at left. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Advertisement for William Calder’s “Perfect 1-Family Brick Homes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 1928.

Accommodating the motorcar, in a discrete way beneficial to the urbanism of the street, was the hallmark of Brooklyn’s last great builder of the interwar era—Fred C. Trump, father of the contentious forty-fifth president of the United States. Born to Bavarian immigrants in an old-law tenement by the Third Avenue el, Trump—like Calder—knew he wanted to build at a young age. He worked alongside his mother, Elizabeth, to improve a handful of Queens Village building lots left by his father after his death in 1918. He learned all he could apprenticing with local carpenters, took night-school and correspondence courses in drafting and the building trades, and later studied construction management and engineering at Pratt Institute. Trump finished high school in 1923, just in time to grab the tail of the 1920s building boom. The very next year, Elizabeth was advertising homes built by her son on 212th Street in Queens Village, and by 1926 Trump had erected nineteen “beautiful English type homes” of his own design on 199th Street in nearby Hollis (“Be King and Queen in a TRUMP home,” shouted his newspaper ads). He contrived a precarious method to finance construction, selling a half-built house to bankroll its completion and start the next one. Because he was not yet twenty-one years old, his mother had to sign for him at his first closing. By 1929, Trump had luxed his operation, erecting upscale stucco-and-stone Tudor homes on rolling, park-like acreage in Jamaica Estates—a setting “so like the aristocratic estates of Old England,” gushed the builder in a Herald ad, where one could enjoy “the quiet and sturdiness of country—and yet be right in New York City.”27

With the building industry slowed by the faltering economy, Trump was forced to cool his heels running a supermarket he opened on Jamaica Avenue in Woodhaven—one of the first in New York City (later acquired by the King Kullen chain of Long Island). But the Depression brought new opportunities and opened the door to the neighboring borough. Trump got into Brooklyn real estate by buying up the assets of a failed mortgage and title colossus known as the House of Lehrenkrauss. A German American banking and insurance conglomerate founded in 1878, the firm began trading in what were known as “certificated” mortgages during the great 1920s building boom. “To pay for the residential properties going up all over New York City,” writes Trump family chronicler Gwenda Blair, “mortgage banks and title companies began to ‘certificate’ mortgages—that is, to divide them into shares that were then sold to the general public like so many bonds.” The Lehrenkrauss certificates were popular with small investors and continued to pay a respectable return despite the Depression. Then, in early December 1933, the House of Lehren-krauss became a house of cards. The venerable firm, it was discovered, “had been running a deficit operation for years,” writes Blair, “covering expenses and salaries with a haphazard assortment of schemes that included issuing watered stock, writing up mortgages based on either inflated or nonexistent evaluations, selling mortgage certificates worth more than the mortgages they represented, and taking out bank loans against mortgages that had already been certificated.” With the Depression holding down its cash flow, the House of Lehrenkrauss soon found itself underwater. To pay its furious creditors, the company’s shrinking assets were put on the auction block. Trump and a partner, both outsiders from the wilds of Queens, prevailed against well-heeled, politically well-connected Brooklyn bidders to secure the mortgage-servicing department of the company, which managed a large portfolio of properties on which it held mortgages. One of the Lehrenkrauss assets now controlled by Trump was the Tudor-manse colony of Laurye Homes that Lawrence Rukeyser had begun building in Marine Park. When Rukeyser’s operation went belly-up in 1932, his unfinished dwellings were acquired by the Raemore Realty Company, with mortgages guaranteed by the House of Lehrenkrauss. Raemore managed to complete and sell a handful of the homes in spring of 1932. But sales petered out by summer; and when Lehrenkrauss slipped beneath the waves in 1933, Raemore went under with it. Trump lost no time completing the half-built houses; by the end of May 1935 he had sold three properties. Thus was Brooklyn’s greatest real estate empire launched at the far-flung corner of East Thirty-Third Street and Fillmore Avenue, on land farmed since the time of Cromwell and Milton.28

Trump next built a battery of sixty-five attached “brick bungalow” row houses on a site just north of Kings Highway at Schenectady Avenue in East Flatbush, the first of what would become a Trump staple in the years before World War II. The bungalows made for good urbanism, creating delightfully scaled streetscapes that only improved with time as street trees—nearly always London planes—reached maturity. The typical prewar Trump row house sported a roofline punctuated by gables, black steel-frame casement windows with an occasional pane of leaded glass, a small porch, and “a beach-towel-size swatch of front lawn” raised just enough above the ground-plane to inhibit casual trespass.29 And, in a departure from the design of the cheaper Realty Associates homes, Trump wisely relegated cars to a common alley behind the dwellings. This not only contributed to the architectural unity of the street, but made on-street parking more plentiful by eliminating that bane of the outer boroughs—driveway curb cuts and the inevitable conversion of front lawns into parking pads. In April 1936 Trump purchased a large parcel from Realty Associates at Cortelyou Road and Albany Avenue, campsite of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus that spring. By the Fourth of July, he had four hundred men digging foundations where elephants and camels had trod just months before, and soon erected the first batch of 450 brick bungalows. What sped this and subsequent Trump projects along was a stimulus program initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s new Federal Housing Administration to jump-start the housing sector. In June 1934 Congress passed the National Housing Act, Title II of which authorized the federal government to serve as guarantor of last resort to banks making mortgage loans, thereby assuming much of the risk in a volatile real estate market. Banks could now lend up to 80 percent of the value of a property, up to a limit of $12,800, while the interest rate could not exceed 5 percent. With Uncle Sam thus watching their backs, bankers could “turn on the fiscal spigots, and construction could resume.” To assure that it was not backing junk, the FHA issued the first nationwide standards for appraising real estate and assessing the creditworthiness of borrowers, as well as strict guidelines for building design and construction. “Because many areas lacked building codes,” writes Blair, “the FHA put together its own minimal standards for key elements like indoor plumbing, fire protection, sewage disposal, lot size and subdivision planning.” Trump soon mastered these standards, winning favor with the FHA state director for New York, a Bay Ridge lawyer and Democratic machine operative named Thomas Grace. Impressed by the young man and his plans—and by Trump’s expanding network of political friends—Grace authorized $750,000 in mortgage insurance for the circus-ground venture, enabling Trump to take out the huge construction loans necessary to erect the 450 homes.30

Thus sheltered under the FHA’s big tent, Trump followed the circus—literally. In May 1937 he began erecting a colony of 400 homes at Clarendon and Ralph avenues, with a crew of 350 men working day and night with the aid of floodlights. A year later he had another venture under way closer to Kings Highway, adding 300 more homes to his portfolio. By the spring of 1939, Trump had sold some 700 houses in Flatlands; he was just thirty-four years old. He now set his sights on a large parcel of vacant land near the junction of Utica, Remsen, and East New York avenues in Brownsville. This land, too, had been used—in 1938 and 1939—for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Here Trump rolled out his largest FHA-backed venture yet, speedily erecting 400 homes. By now he was using principles of mass production similar to those that Greve had pioneered a decade earlier at Gerritsen Beach, earning him the sobriquet “the Henry Ford of housing.” By 1940, Fred Trump was the biggest builder in Brooklyn. He erected another 300 homes on East Thirty-Ninth Street and Foster Avenue by Paerdegat Park in East Flatbush, then turned south to Brighton Beach, where he built 200 deluxe dwellings at Corbin Place and Neptune Avenue—this time without FHA backing. And Trump was as ingenious at marketing his homes as he was in constructing and financing them. He set up an elaborate billboard at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, seen by hundreds of thousands of visitors, and even took to the sea to sell his wares—in a sixty-five-foot cabin cruiser with TRUMP HOMES spelled out in ten-foot-tall letters on twin hoardings. The Trump Show Boat first worked the thronged Coney Island strand on July 8, 1939. With the city in the midst of a heat wave, beaches were packed. As the captain drew near the surf, loudspeakers came alive with music, and crewmen began tossing hundreds of inflatable swordfish into the water. Each was stamped with TRUMP HOMES and a figure, from $25 to $250, indicating its value toward a down payment. Like a riot of gulls trailing a laden trawler, swimmers raced into the ship’s wake for the bobbing fish. The music was so loud it could be heard a mile off. Hundreds stood at attention when “The Star-Spangled Banner” played; others rushed to the water when the boat began broadcasting “lessons in ‘aquacading’ or graceful swimming to music.” Not everyone was pleased—park commissioner Robert Moses, for example. A hater of carnies, hawkers, and shrills, Moses had a police boat stop the craft and issue the captain tickets for operating in a bathing area, advertising without a license, and violating noise ordinances. Trump suggested Moses join him on board. The Show Boat was back out the next day, cruising the beach while Trump and his buddies fished from the stern—their ears presumably plugged. “Twenty fluke, porgies and weakfish were caught, all while the music was playing,” Trump exulted; “When the music stopped playing the fish stopped biting.” Moses and Trump played a waterborne game of cat and mouse all that summer and the next, the TRUMP HOMES message reaching countless New Yorkers in the process. At a hearing in September 1940, Judge Jeanette Goodman Brill—first female magistrate in Brooklyn—issued Trump a perfunctory fine before inquiring, sotto voce, whether he still had homes for sale in Flatbush.31

Brick-bungalow row houses by Fred C. Trump, Fillmore Avenue, Marine Park. Photograph by author.

“Going South! Wish I could afford to.” This 1938 Williamsburgh Savings Bank advertisement refers not to the American South, but to the booming streetcar suburbs of Flatbush and Flatlands. From Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 7, 1938.

Fred Trump went on to erect more than two thousand homes in Brooklyn between 1935 and 1942. Like Greve, Calder, and the long-forgotten scores of small builders before him, Trump helped weave much of the fabric of outer-borough New York City, creating a vast tapestry of bedroom communities far from the centers of commerce and industry. Here were the homes of the great multitude that flocked to Brooklyn all through the interwar years. The decade between 1920 and 1930, the very years of the tax holiday legislation, was the most rapid period of growth in Brooklyn history. The borough’s population soared by 577,598 people in those years—more than Washington, New Orleans, or Kansas City at the time. As with Levittown a generation later, the cognoscenti had great fun mocking the mock-Tudor home-scapes of Brooklyn and Queens. George Bowling—protagonist in George Orwell’s Coming Up for Air (1939)—could well have been returning to once-rural Flatlands when he cringed at the “houses, houses everywhere, little raw red houses . . . semi-detached torture-chambers where the poor little five-to-ten pound-a-weekers quake and shiver . . . with the boss twisting his tail and the wife riding him like the nightmare and the kids sucking his blood like leeches.” Critics rightly questioned the suitability of an Old World style like the Tudor for an age of airplanes and penicillin. As Russell Whitehead put it, the Tudor was just “a delicious piece of stage scenery,” no different from “the peasant village Marie Antoinette caused to be erected in the Trianon Gardens.” Lewis Mumford fretted that whenever “a sophisticated age attempts to reproduce the forms of a simple one . . . the result is bound to be ephemeral.” But Mumford was wrong; if anything the Tudorvilles of outwash Brooklyn have endured, still affordable and remarkably resistant to all but the most egregious lapses of homeowner taste: stainless-steel railings in place of wrought iron; peach-pink stucco slapped atop perfectly good brick; corrugated awnings from the 1970s, now blackened with mold; black-steel casement windows torn out for cheap double-hung, double-paned vinyl replacements. However inept, these are yet marks of a place suffused with the funk and pulse of life unmediated by the pieties of Historical Significance, far from the Midas of gentrification, undiscovered by the merchants of twee.32

The most piercing account of outwash Brooklyn was penned the same year as Orwell’s Coming Up for Air by brilliant, doomed James Agee, the Tennessee-born, Harvard-dipped wordsmith alcoholic who famously expired in a taxicab on the anniversary of his father’s death forty years earlier. In 1939, Agee was commissioned by Fortune to write an article about Brooklyn for a special issue of the magazine on New York City. But the essay he delivered to his editor, “Southeast of the Island: Travel Notes,” was deemed “too strong to print” and remained unpublished for nearly thirty years. Agee spent two months at 179 St. James Place in Clinton Hill writing the piece, a smugly merciless portrayal of life and culture in the trolleyburbs of deep-south Brooklyn. No Whitmanic paean to the brotherhood of man, Agee’s essay begins by Othering the Brooklynite, as if crossing the East River put him in a foreign land. Here, “in the trolleys, or along the inexhaustible reduplications of the streets of their small tradings and their sleep,” wrote Agee, “one comes to notice . . . a curious quality in the eyes and at the corners of the mouths, relative to what is seen on Manhattan Island: a kind of drugged softness or narcotic relaxation.” It was the same look seen in shell-shocked soldiers or “in monasteries and in the lawns of sanitariums.” Each action, each building seemed there bound by “a deep taproot of stasis.” Brooklyn’s storied provincialism—its “absorption in home, the casualness of the measuredly undistinguished . . . is profoundly domesticated, docile and ‘stable’ a population as one could conceive of, outside England”—was a function of its fateful proximity to Manhattan, whose “mad magnetic energy” sucks the borough of “most of what a city’s vital organs are.” Brooklyn was thus like no other American city; for “though it has perhaps a ‘center,’ and hands, and eyes, and feet, it is chiefly no whole or recognizable animal but an exorbitant pulsing mass of scarcely discriminable cellular jellies and tissues; a place where people merely ‘live.’” Into the somnolent mass ventured the sanctimonious scribe:

One of Philip Freshmen’s “English Tudor Homes” on East Thirty-Third Street. Photograph by author.

I leave the trolley and walk up a residential street: I have not gone a block before I recognize a silence so powerful and so specialized it has almost a fragrance of its own: it is the silence of having left a street of the open world and of having entered an empty church . . . and there is in the silence an almost Brahmin tranquility, weakening to the senses, and a subtly terrifying quality of suffocation and of the sacrosanct: and in a moment more, standing between these rows of neat homes, I know what this special sanctitude is: that this world is totally dedicated to tame marriages in their first ten years of youth, and that during the sweep of each working day these streets are yielded over to housewives and to young children and infants so entirely, that those who stroll these walks and sit in the sun are cloistral nuns, vestals, made fecund though they are, and govern a world in which returning men are made womanly in an odor of cherished floors, clean cloths, nationally advertised cosmetics, and the sharp stench of babies.

But more than anything it was the sheer scale of Brooklyn that awed Agee, with “continuities so astronomically vast as Paris alone or the suburbs south of Chicago could match.” From his morainal perch, the writer peered down upon “a vista of low buildings and side streets of glanded living sufficient to paralyze all conjecture.” There seemed, then as now, “simply, far as the eye can strain, no end of Brooklyn,” rolling south and forever to the sea-lapped shore.33