CHAPTER 11

SALT MARSH OF

SUNKEN DREAMS

Versailles? That is, indeed, a thought . . .

—EDWARD ALDEN JEWELL

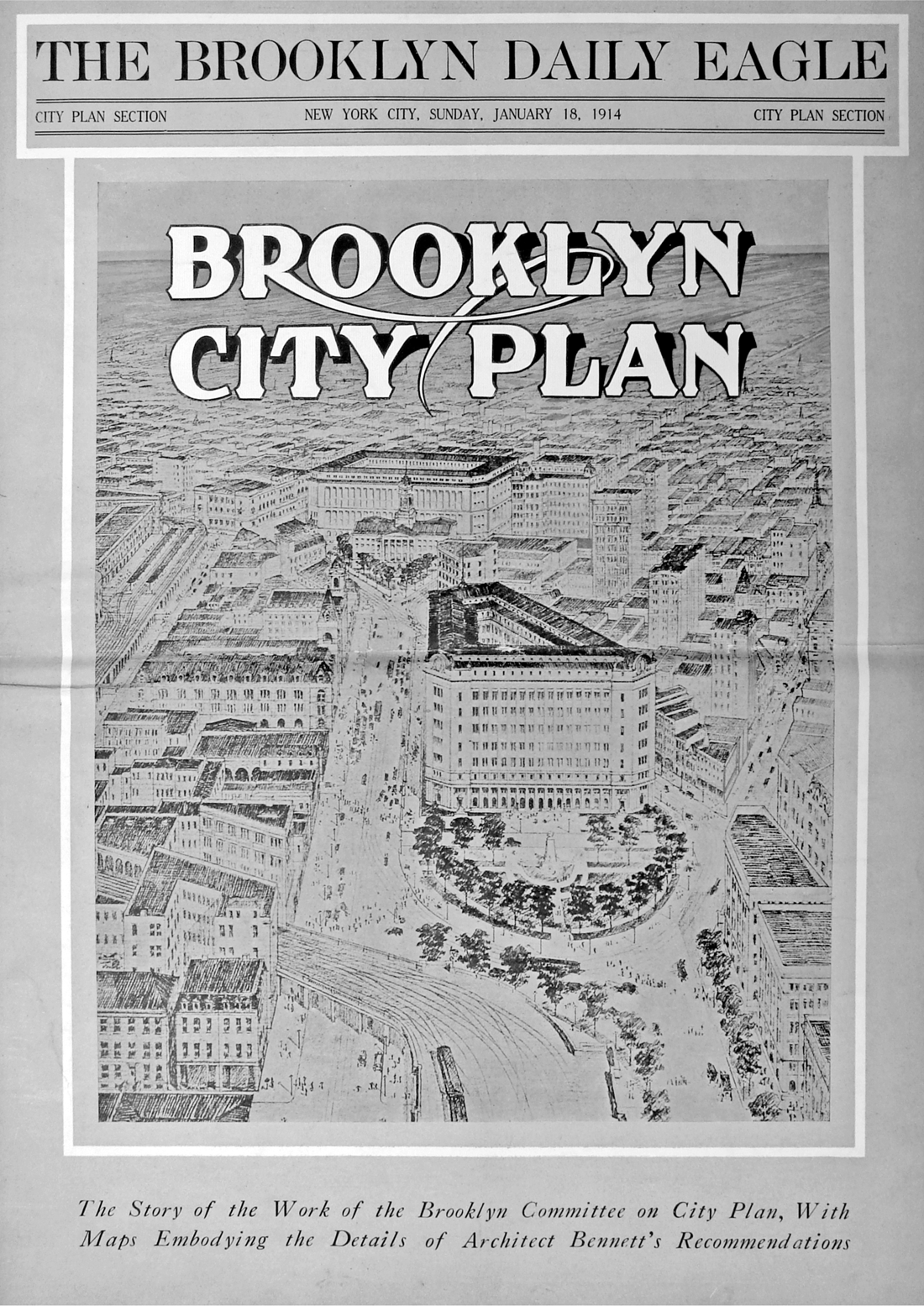

It was at the other end of town, far from the lofty Heights, that the Brooklyn Beautiful movement achieved its greatest victory. Edward Bennett presented his plan at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on December 12, 1913, two years to the day after the celebrated visit of his late partner, Daniel H. Burnham. The report’s maps and diagrams were displayed for the public at 180 Montague Street and published in a January 1914 special “City Plan” supplement of the Brooklyn Eagle. Though skillful enough, Bennett’s plan lacked the originality and grandeur of the Chicago project he and Burnham had collaborated on five years earlier. Some of its key elements—a new civic center in downtown Brooklyn, an institutional complex at Grand Army Plaza, extending Shore Road from Bay Ridge around Gravesend Bay to Coney Island—had been proposed by the Reverend Hillis or others before him. Bennett recommended extending Olmsted’s parkway plan, too, by widening several existing thoroughfares, adding medians and multiple rows of trees—Fourth Avenue, Sixty-Fifth Street through Bensonhurst, Kings Highway, Avenue P, and a short section of Nostrand Avenue. From there, a new parkway would run south into the one real diamond of the Brooklyn City Plan—a seventeen-hundred-acre littoral counterpart to Prospect Park. Identified simply as “the marine park,” it alone made Bennett’s pallid scheme worth the expense.1

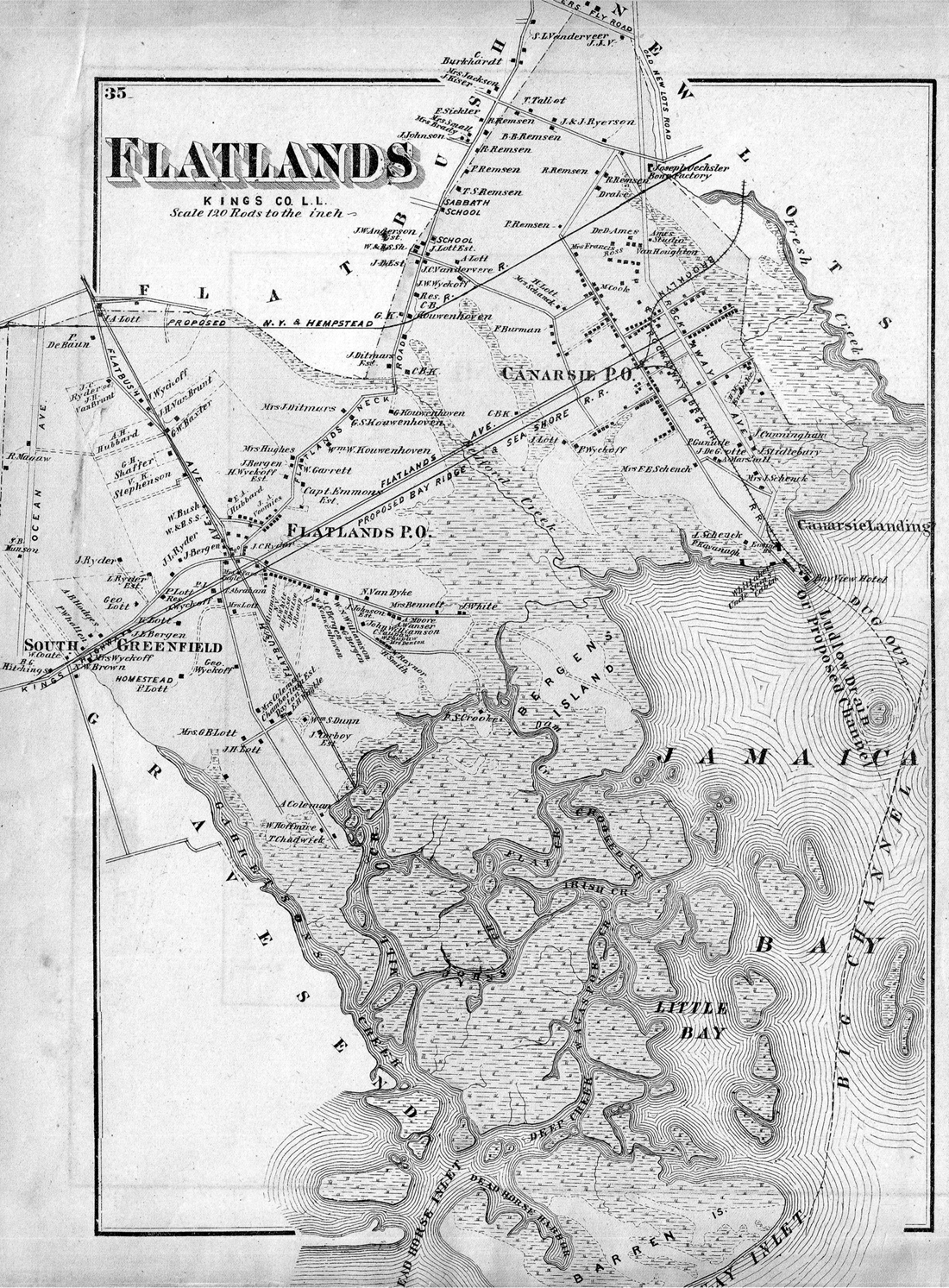

Bennett did not design the park itself. He showed it only as a green zone stretched across a plexus of radiating avenues, anchored by three baroque ronds-points. One was on Flatbush Avenue at the projected crossing of Ralph Avenue; a second at the intersection of Avenue W and Madison Place; and a third at the foot of Knapp Street on Sheepshead Bay, where Sixty-Fifth Street—pushed south from its Avenue P terminus—would meet the Shore Road extension. The marine park would clamp his borough-wide open space system firmly to the shore, achieving at last what Olmsted had attempted a generation earlier with Ocean Parkway at Coney Island. The centerpiece of the new park was the old Strome Kill, whose waters the Gerritsen clan had dammed to power their gristmill two hundred years before. For all its rich history—and notwithstanding the counsel of America’s most admired city planners—the storied littoral would almost certainly have been churned into street grid were it not for the two philanthropists who helped bring Burnham and Bennett to Brooklyn: Frederic B. Pratt and Alfred Tredway White. Pratt and White were among Brooklyn’s leading men, deeply committed to progressive causes and civic improvement: the former was president of Pratt Institute and the son of its founder; the latter built some of the earliest worker housing in New York City (including the delightful Workingman’s Cottages at Warren Place in Cobble Hill and the Home, Tower, and Riverside apartments in Brooklyn Heights). Beginning in 1912, the men began quietly acquiring parcels of land around Gerritsen Creek, eventually accumulating more than 120 acres. In 1920 they attempted to donate their holdings to the city for a park, along with $72,000 in funds to acquire additional land, including the old mill, and to extinguish ancient rights-of-way to the shore.2

“Brooklyn City Plan,” special supplement to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 18, 1914. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Incredibly, Mayor John F. Hylan refused to accept the gift, despite a unanimous vote in support by the Board of Estimate. The city ostensibly feared it could not afford the cost of filling the marshy tract in order to make it a functional park, which the shortsighted Hylan, a Tammany drone, was not convinced was even needed in such a thinly settled, still-rural part of the city. Moreover, city officials suspected that Pratt and White had donated the land on behalf of friends in the real estate business. Hylan himself claimed the bequest came with “strings,” while commissioner of accounts David Hirshfield bluntly called it “a scheme for enhancing the value of private real estate holdings at the expense of the city.” His criticism was not wholly off mark. Much like the Commercial Club of Chicago (which commissioned the Plan of Chicago), the Brooklyn Committee on City Plan was dominated by businessmen committed to the borough’s steady growth. One of its most influential members was William M. Calder, a prolific Brooklyn builder who won a seat in the US Senate in 1916 (where he sponsored, among other things, the legislation that created daylight savings time). Calder was a major developer in the southern half of Brooklyn, erecting thousands of homes in Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Flatbush, and Sheepshead Bay (more on him in chapter 13). Calder had large holdings adjacent to the Pratt and White land, and was among the first to build homes in the Marine Park area. “It is an axiom,” he wrote in a leaflet promoting his two-family homes at Coyle Street and Avenue T, “that the building of a park is certain to increase the value of the area adjacent to it.” He promised that one day the environs around Gerritsen Creek would be “one of the choicest residential sections of Greater New York.”3

But the real reason the Pratt-White bequest was refused was politics. The park was gifted to Mayor Hylan’s anti-Tammany predecessor and rival, “Boy Mayor” John Purroy Mitchel, whom he defeated in 1917. Mitchel, the city’s youngest chief executive, was immortalized eight months later when he fell out of his army plane during a flight-training maneuver in Louisiana. Despite appeals by the press, the Board of Estimate, and Brooklyn borough president Edward J. Riegelmann, it was not until March 1925—Hylan’s last few months in office—that the Pratt-White bequest was finally, fully consummated by the city. The mayor had allowed a political rivalry to keep a major open space from the people of New York City for most of a decade. What finally sprang Hylan into action was fear that his long delay would cost him the Brooklyn vote in the next election. Additional properties were now purchased around the estuary with Pratt-White funds, bringing the park total to 147 acres—a 12 percent increase of open space for park-poor Brooklyn. And this was just the start. Strategic acquisitions at Plum Beach and along Flatbush Avenue fused this land to vast acreage at Barren Island already owned by the city; overnight, the future park grew to over a thousand acres. Suddenly bigger than either Central or Prospect Park, it could become the “greatest Marine Park in the world,” shouted the Brooklyn Eagle. George Murray Hulbert, president of the city’s Board of Aldermen, made a trip to Detroit’s Belle Isle Park—one of the few American public parks designed in a formal Italianate style—and came back convinced that “Gerritsen Park . . . could be made a duplicate of Belle Isle and go it one better.” As the 1925 Democratic primary neared, Hylan’s promises for the city’s newest park grew ever more extravagant—it would be “the most varied and delightful playground for the city’s populations,” a veritable “Garden of Eden for the use of New York’s inhabitants in their hours of leisure.” But it came too late for Hylan, whose seven years of foot-dragging earned him the distrust and enmity of Brooklyn’s well-organized civic groups. The mayor was defeated by Jimmy “Beau James” Walker for the Democratic nomination, losing the borough by just 4,857 votes.4

One of the properties acquired in Hylan’s rush was the Gerritsen mill and the estate it had been part of for decades—the Brooklyn retreat of William C. Whitney, one of America’s wealthiest and most powerful men. A descendant of Puritan settlers, Whitney was educated at Yale and admitted to the New York bar in 1865. He married Flora Payne, daughter of Oliver Hazard Payne and—coincidentally—a distant relative of intrepid airman Calbraith Perry Rodgers. Whitney was later appointed secretary of the navy by President Grover Cleveland, and built immense fortunes in real estate, street railroads, steel, and coal. A man of enormous energy and ambition, Whitney had two great passions in his later life—land and racehorses; and he owned more of each than almost anyone else in the United States. He collected estates up and down the Eastern Seaboard, including a sixty-eight-thousand-acre preserve in the Adirondacks where Gifford Pinchot carried out some of the first experiments in scientific forestry in the United States (much of the land is today the William C. Whitney Wilderness Area around Little Tupper Lake). In his later years, Whitney circled back to New York City, where he built a palatial residence at 871 Fifth Avenue and, in 1899, acquired the Gerritsen spread for breeding thorough-bred horses close to Brooklyn’s three great racetracks. Its crown jewel was a palatial Greek-revival manor house that lorded it over the west shore of Gerritsen Creek, like something from the antebellum South that floated in on a proxigean tide. Known as “the finest country house in Kings County,” it had been built decades earlier by Stephen H. Herriman—a founder of the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railway Company who had married into the Gerritsen family. Whitney gutted the place to make it his own, seeking solace there after the tragic death of his young second wife, Edith Randolph Whitney. The house was used mainly as a man cave for the Sheepshead Bay racing season. But neither the house nor Whitney’s many horses provided succor; a broken man, William Whitney died soon after. Whitney’s children—including Harry Payne Whitney, whose immense inheritance helped create the Whitney Museum of American Art (founded in 1931 by Harry’s wife, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney)—built estates of their own on the fashionable north shore of Long Island. By the time Pratt and White began buying up Gerritsen Creek for the future park, the Whitney land was being used as a children’s summer camp by the Brooklyn Tuberculosis Committee. Tragically, in 1937 the city demolished both the Harriman mansion and the Dutch-colonial Gerritsen house nearby, wiping out in a single day three centuries of New York history. The only trace of Whitney’s tenure on the estuary today is the population of ring-necked pheasants, descended from his game birds, that still nest among the reeds and native marsh birds.5

The city’s long-delayed acquisition of the Gerritsen estuary came not a moment too soon; for now a great tide of residential construction—one of the biggest building booms in American history (subject of chapter 13)—swept down Brooklyn to engulf much of the uplands around Gerritsen Creek. Fields cultivated since the 1630s now brought forth a vast crop of mock-Tudor homes. There was one last holdout—an Italian immigrant truck farmer named Frank Buzzio who plowed (alas illegally) the land around Gerritsen Creek with four compatriots and a team of horses. Buzzio and his boys were Brooklyn’s last agrarians, at least before the hipster-locavore revolution of recent years. All five were hauled before the authorities for farming public property. Buzzio—“a son of sunny Italy,” as one reporter called him—claimed the land was ragweed choked and collecting junk before he plowed it. When it was learned that three of the men were veterans of the Great War, they were not only allowed to continue but commended for making the idle land bear fruit—or at least potatoes and cabbage. But they wouldn’t have much longer. Jimmy Walker went on to win the 1925 general election and was sworn into office the following January. Beau James was a parks man, and he understood that Marine Park might make his legacy; he envisioned there the “greatest of a great chain of parks in New York City.”6

But now a seductive future grabbed the headlines. It came from the fruitful mind of promoter, impresario, and serial entrepreneur Sol Bloom. Bloom was an American original. The self-made son of Jewish immigrants, he amassed a fortune in the music industry while still a teenager. In 1891, just twenty-one years old, he moved to Chicago to take a position as entertainment director for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. For a salary of $1,000 a week he was to supervise planning and development of the Midway Plaisance. Daniel Burnham was his boss. He liked the ambitious young man: “You are in complete charge of the Midway,” he told Bloom; “Good luck.” Bloom was a funhouse-mirror Burnham, his Midway the antithesis of everything the latter’s didactic White City stood for—order, unity, civic virtue. It was a mile-long sideshow full of hucksters and oddities, anchored by the first Ferris wheel and lined with scandalous displays of ethnic “types” from Asia and Africa. Bloom’s biggest hit was “A Street in Cairo,” with snake charmers and fettered camels and a salacious act that introduced Americans to the belly dance. Burnham allowed the Midway as a concession to popular taste and because it would pay the bills; he placed it as far as possible from his Court of Honor—literally on the other side of the Illinois Central tracks. Yet the people came—more, in fact, than toured the White City’s free exhibits. Bloom’s Midway was the most popular attraction of the fair. Bloom later moved to New York to make another fortune, selling sheet music and the Victrola phonograph (he coined the slogan “His Master’s Voice”). In 1922 he was talked into running on the Tammany ticket in a special election for the Nineteenth Congressional District. He narrowly won a seat. Two years later, President Coolidge appointed him to the Washington Bicentennial Commission, formed to prepare for the two hundredth anniversary, in 1932, of George Washington’s birth. Before long he was chairing the commission. Bloom threw himself into the work: he read books on Washington, visited his ancestral home in England, pored over documents in the British Museum. Bloom bombarded the commission with ideas—plays and theatricals about the great man; Washington busts for every classroom; a full-scale replica of Mount Vernon for Prospect Park; broadcasts of Washingtonia from an antenna—where else?—atop the Washington Monument. One Bloom initiative lives on in our pockets and purses even now—the ubiquitous Washington quarter. But all this was spare change to Bloom’s pièce de résistance: a great jubilee to honor Washington, bigger than the Columbian Exposition.7

Flatlands, 1873. From F. W. Beers Atlas of Long Island, New York. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

The Washington Bicentennial Exposition of 1932, as he called it, would be staged in Brooklyn—“hallowed theater of his first exploits in the name of liberty”—and on the very acreage that was supposed to become Marine Park. With the élan of a master showman, Bloom outlined a vision for the great fair that captured the imagination of press and public alike. It would be the grandest ever held, with pavilions for forty-six nations, a channel deep enough to accommodate naval ships, and a football stadium for 200,000 spectators—more capacious than any stadium in the world even today. There would be a great skyport to receive flying dignitaries. The fair’s parking lot alone—to accommodate a staggering 100,000 automobiles—would require an area the size of Prospect Park. High overhead would be a structure “taller and greater,” insisted the Brooklyn Eagle, “than either the Woolworth Building or the Eiffel Tower,” topped with a searchlight bright enough to be seen in Detroit or Quebec. An “international aviation tour,” led by famed pilot Clarence D. Chamberlin—would circle the globe to seed interest among foreign governments. More than 25 million people attended the Columbian Exposition; Bloom promised 100 million in just the first six months—nearly 90 percent of the American population in 1925. The press swooned. The Brooklyn Eagle gave Bloom’s Washington Expo plan the entire Sunday edition front page on November 8, 1925, while the New York Times hailed his proposal “to build a magical city . . . with all the splendor of the Court of Honor at Chicago,” and predicted that soon “the structural beauty of Washington Fair by day and its brilliant constellation by night will gleam across the lower bay and far out on the Atlantic” (after all, the writer allowed, “our architects lead the world . . . especially in this matter of dream cities”). Nor would all this be a flash in the pan. Bloom wanted a permanent exposition—“a perpetual monument to Washington’s memory.” And since Washington was an entrepreneur before he was a statesman, his bicentennial fair would also earn its keep. Bloom pitched it as an entrepôt to advance global commerce and industry, the World Trade Center fifty years before its time. He even envisioned a future Brooklyn Institute of Technology for the site.8

As Bloom’s Washington Exposition bill went before Congress, Brooklyn’s numerous, well-organized civic associations began lobbying on his behalf. An International Exposition Company was formed, with offices at 154 Nassau Street. Former secretary of the World’s Columbian Commission John Tilghman Dickinson became an adviser. The president of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler, lent his support, as did the mayor of Miami Beach, Louis Snedigar. The Board of Education was urged to have all city pupils sign a supporting petition, to be flown to Washington by Charles Lindbergh. But the campaign soon fell apart. Backers began squabbling. Bloom’s Washington Exposition bill languished in committee. The financial failure of the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia quelled the enthusiasm of investors. Two of the fair’s most ardent promoters—Lawson H. Brown and Charles Bang—began soliciting funds even as Bloom’s bill was before Congress. When word of this got to Washington, Bloom was forced to sever ties with the very campaign he had inspired. Then Chicago jumped into the fray, announcing plans to mount a Washington Exposition of its own. By now, New Yorkers beyond Brooklyn had bought into the idea of a 1932 fair somewhere in the city. Mayor Walker formed a Greater New York World’s Fair Committee, chaired by police commissioner Grover Whalen. The disgraced Brooklyn faction was not invited. Brown and Bang cried foul, accusing Whalen of stealing what had been a Brooklyn idea. But it was not yet Gotham’s time, either; Chicago won the round, staging the Century of Progress Exposition in 1933. Despite the worsening Depression, New York forged ahead with plans of its own for a fair—still being called the Washington Exposition as late as October 1935.9

Sol Bloom and his daughter Vera aboard ship, 1925. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

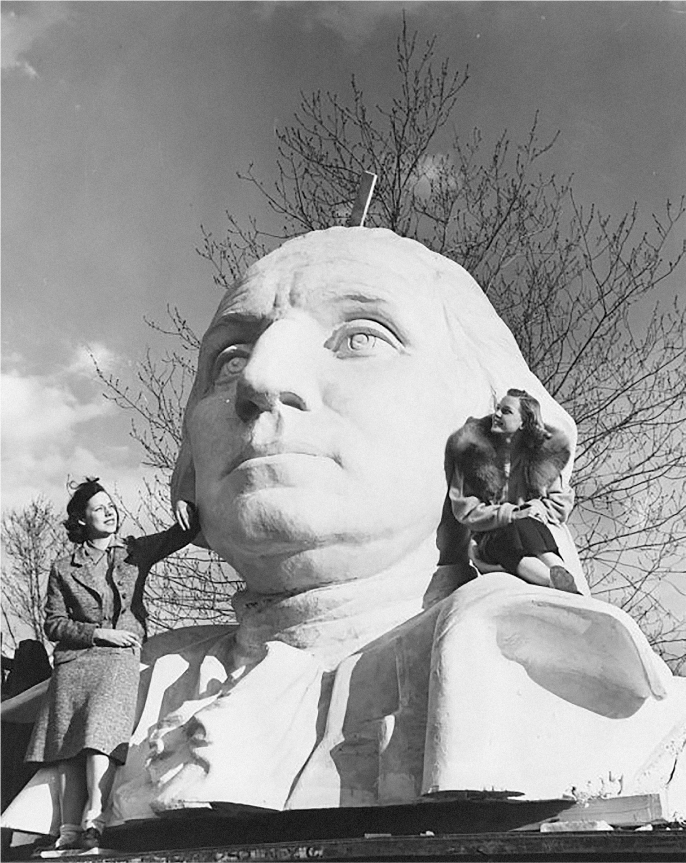

It would not, however, be held in Marine Park. A powerful new player was on the scene—Robert Moses, first commissioner of the city’s unified parks system. Moses was agnostic about the fair but understood it could help fund his dream of transforming one of the city’s most blighted landscapes—Flushing’s “valley of ashes,” invoked by F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby. Moses moved mountains, of trash at least, to bring the Washington expo to Flushing. No other city site stood a chance—including Marine Park, despite its many advantages. In the end, it was poetic justice of a sort that Queens should win over Brooklyn: the Corona dumps had been filled mostly with the latter’s junk—as Moses himself put it, with “thirty years of the offscourings, the cans, cast-off baby carriages and umbrellas of Brooklyn.”10 When the New York World’s Fair finally opened, its centerpiece was not Washington but a pair of abstract forms. But George was there nonetheless. Not for nothing had Sol Bloom served as a director of the World’s Fair Corporation and a member of the United States World’s Fair Commission. The impresario may have failed to build his “perpetual monument” in Marine Park, but he made sure that his hero was all over Flushing—there in James Earle Fraser’s monumental statue of Washington, sixty-five feet tall and wrapped in a great cape, staring down the fair’s Central Mall at the Trylon and Perisphere; there on Julio Kilenyi’s official fair medal, with its likeness of the general floating in a cloud. And Bloom made sure, too, that this event otherwise dedicated to “The World of Tomorrow” opened on the 150th anniversary of Washington’s inauguration at Federal Hall.

James Earle Fraser’s monumental sculpture of George Washington, prior to installation on the Central Mall of 1939 New York World’s Fair. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

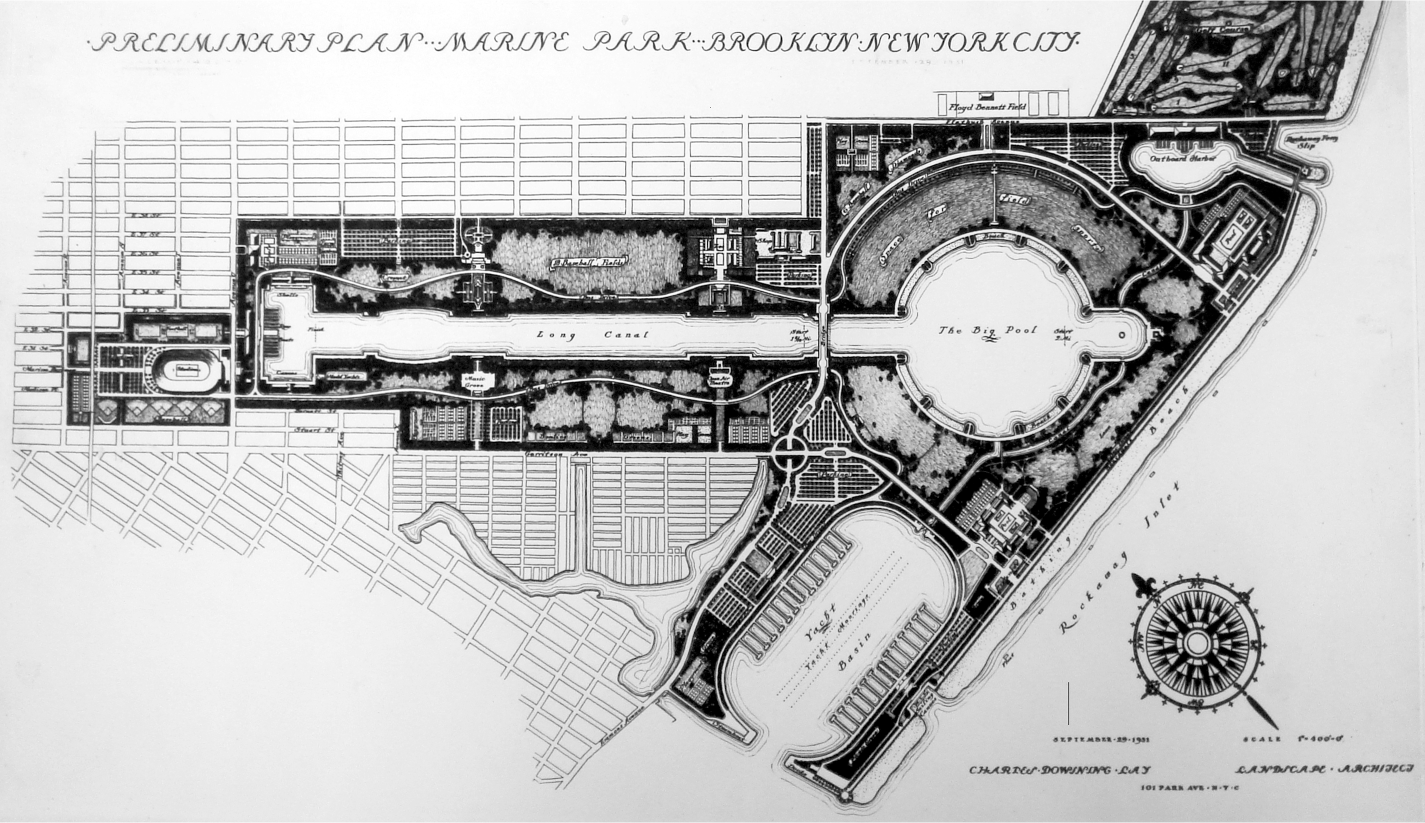

As hope faded for a Washington Exposition in Marine Park, attention turned once again to making it a great urban playground. On January 1, 1928, Brooklyn park commissioner James J. Browne revealed a preliminary plan for Marine Park, promising to banish the “straggling, irregular waterways and swamps abounding in the area,” reported the Eagle, and build in their place “the finest park and playground in the Nation.” The scheme itself was hardly fit for such exalted terms—little more than a golf course and a series of tidal lagoons lashed together with a spaghetti-spill of paths and roads. It had been prepared “under stress and hurry” by department landscape architect Julius V. Burgevin, a former florist from Kingston, New York, who also redesigned Union Square Park and landscaped the Park Avenue Malls. At Pratt-White Field, the portion of Marine Park north of Avenue U, landfilling was well under way along appropriately named Fillmore Avenue, using detritus hauled across Brooklyn from excavation for the Fulton Street subway. A first playground and baseball diamond opened to the public there in August 1930. At the dedication, Walker spoke of Marine Park as one day becoming “the strongest link in the greatest chain of parks in the greatest city in the world.” He hoped those in the gathered crowd would “live long enough” to see this dream come true—“I probably won’t,” he confessed (accurately); “It’s a short life for the Mayor, politically and otherwise.” That fall, Browne announced plans for a design competition that would draw “the best architects of the country” to design the vast balance of Marine Park. It would be staged in cooperation with the American Society of Landscape Architects and the influential Park Association of New York City. A “special inducement” of $20,000 would be awarded the winning scheme. Bremer W. Pond, a professor of landscape architecture at Harvard University, agreed to supervise it and draft the competition brief. A youthful Gilmore D. Clarke was the society’s choice as adviser. Just thirty-nine, Clarke had gained national attention for the innovative motor parkways he was planning in Westchester County, among the first modern highways in the world. But the dilettante mayor—distracted by showgirls and speakeasies, his administration beset with corruption charges—did little to make real his vaunted “chain of parks.” By the spring of 1931 the press was getting restless; “Seven Years Pass for Marine Park,” pushed the Eagle, “but Where Is It?” The competition was on hold because Walker never referred the proposal to the Board of Estimate for approval. With months lost and suspecting that the mayor might well indeed have a short political life, Browne did what any good Tammany commissioner might do—he offered the job of designing Marine Park to a neighbor.11

To be fair, Charles Downing Lay was supremely qualified for the job. No other landscape architect in America knew Brooklyn as well, nor possessed his extensive knowledge of Flatlands and the Gerritsen site. Born in Newburgh, New York, in 1877, Lay initially trained as an architect at Columbia University. But he had landscape in his blood—he was a distant relative of the Victorian landscape designer and “apostle of taste” whom we met in chapter 4, Andrew Jackson Downing. Following this muse, Lay quit Columbia for Harvard, where he studied landscape architecture with Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and was granted one of the first formal degrees in the field. He practiced in New York with Robert Wheelwright and Henry Vincent Hubbard, and in 1911 won a coveted appointment as consultant to the Parks Department. But Lay was quickly overwhelmed by a lack of staff, equipment, and even base maps of the city’s parks. He clashed with the city’s eccentric park commissioner, Charles Bunstein Stover—renowned for mysterious vanishing acts—and soon resigned to return to the relative sanctuary of private practice. By the 1920s Lay was one of the deans of the New York landscape profession, with a busy office in the old Architect’s Building at 101 Park Avenue. Despite his Hudson valley childhood, he was a committed urbanist with a profound love of cities. In 1926 Lay authored a forgotten classic on the richness and vitality of urban life, The Freedom of the City. In it he argued that “the great merit of the city” came from precisely that thing city planners were constantly fretting over—density, crowding, “the immense congregation of people in one small spot.” Lay deplored the perennial American urge to make cities more like the country; “A hint of country pleasures may be possible in the city,” he wrote, “but they cannot be allowed to interfere with the essential quality of the city, which is congestion.”12

Marine Park under construction, 1931. Flatbush Avenue and Floyd Bennett Field can be seen at upper left. The vast field of white at top is freshly dredged sand for the Gerritsen Avenue ball fields. Photograph by Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc. Collection of the author.

In its place, Lay loved nature and possessed an especially deep appreciation for the estuarine landscape. “Of the beauty of tidal marshes,” he wrote in a 1912 article for Landscape Architecture, “no one who has lived near them and watched their changing color with the advance of the seasons can speak too enthusiastically. They come to have a place in the heart which mountain scenery, with all its grandeur and fearfulness, cannot equal. Nowhere except at sea does the sky become so much a part of one’s life, and nowhere is there greater beauty of line than in their curving creeks and irregular pools.” Unlike most of his contemporaries, Lay also understood the ecological complexity of wetlands. “The tidal marsh,” he wrote, “is a delicately balanced organism. It has a flora and fauna of its own, and it depends for its life upon the recurring tides, which bring soil and fertility and moisture for the plants at home there. Equally important . . . is the effect which continual flooding with salt water has in restricting the varieties of plants which grow there; for the grasses and sedges only can endure such hard conditions.” Nonetheless, Lay’s nuanced appreciation of the marsh landscape never eclipsed his Calvinist sense of utility. The task incumbent on the landscape architect—especially this one, charged with creating a great city park—was “to make the marsh more usable, and at the same time preserve its beauty, or at least give it beauty of another type.”13

Doing so would not be easy. For one, Browne’s sudden job offer enmeshed the genteel Lay in a firestorm of controversy. Nathan Straus, Jr.—heir to the Macy’s fortune and head of the Park Association—led the charge, rising from his sickbed to proclaim that such a “makeshift” approach to planning Marine Park was “nothing short of criminal.” He called Lay, unfairly, an “inconspicuous man with no outstanding park achievements to his credit.” In an open letter to Browne published in the New York Times, Straus insisted that a competition was “the only right way to develop the great Marine Park”—the only way to find a designer with the genius and vision to give New York the Marine Park it deserved. That person, he emphasized, “will as surely be revealed by the prize contest for the Marine Park as was Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. by the prize contest for Central Park.” Straus implored Browne to reverse his decision. “Every friend of the parks, every friend of a better city,” he wrote, “is looking to you to throw open the design contest to a fair field with no favor.” But Browne would not budge. Lay was his man, and the mayor—anxious to give work to the city’s swelling phalanx of unemployed—agreed. Moreover, reasoned Walker, “We can’t expect some man from Kalamazoo to take any genuine interest in Marine Park.” Only a local would do, and a diehard at that. “In my opinion,” the mayor stated, “one of the requisites must be that the man hired loves New York City.” Even Straus could not deny Lay that qualification. For his part, Lay betrayed no qualms about transforming the Gerritsen marshes into a great urban playground, even if he had never taken on a commission of such vast scale. “I believe in the greatness of New York,” he wrote, “in its people and in its future, and it is my ambition to design a park worthy of New York.”14

The press cheered. New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell swooned over the scale and possibility of Marine Park, praising Lay for having “undertaken the task of supplying a picture for one of the biggest frames in the history of art.” Moved by his Freedom of the City, Jewell surmised that all who have read Lay’s “wise and delightful little book . . . must agree that the Marine Park assignment has come into able hands.” Jewell, unlike Lay, saw nothing of value in marshland; to him it was simply a “clean slate” upon which almost any design might be projected. He compared Lay’s task to that of creating Central Park, arguing that Marine Park posed the greater challenge. For while Olmsted and Vaux had on-site a surfeit of “plastic materials . . . all at hand,” Lay faced the topographic equivalent of a blank sheet of paper—“a flat stretch of land and strand, of marsh and bayou and lagoon.” Order and beauty would have “literally to be manufactured,” a Herculean task in which “pumps and steam shovels become the artist’s brushes.” Given this, Jewell speculated, it was unlikely that the architect would “attempt to paint into his picture any ambitious hills and valleys. We need not expect even a hint of the grandiose clipped melodrama of Tivoli’s Villa d’Este, the picturesque Baroque of Frascati, Como or Isola Bella. Here will bloom no fabulous Babylonian hanging garden. Versailles? That is, indeed, a thought . . .” Lay evidently leaked his parti to Jewell, who reasoned that the French mode—that “stately and charming artificiality that supplied warp and woof for the landscape loom of the Roi Soleil”—was indeed perfect for the “flat country” of Flatlands, even if such a courtly lexicon “might not meet with unqualified favor along the shores of Sheepshead Bay.”15

Lay submitted his plans to City Hall in October 1931. Months passed before Walker even looked at them; by now Beau James had more urgent matters on his mind. The Seabury Commission was closing in on his police department and law courts, both of which had become Augean stables of corruption on his watch. However enthusiastic the mayor had been about Marine Park, it took a backseat now to political survival. It was not until late February 1932 that Walker finally signed off on Lay’s plans and released them to the public. Expectations for Marine Park were sky-high by now, but Lay handily met them all. Everything about his scheme was Brobdingnagian in scale—starting with the plan itself, rendered by Lay in oil on a sweeping nine-by-five-foot canvas. Swelled now to 1,840 acres, the vast pleasure ground would be larger than Central and Prospect parks combined, with room for more than two million people at any one time—most of the population of Brooklyn in 1930. It would feature bowling greens, archery butts, bocce pitches, picnic groves, lacrosse and croquet fields, two hundred tennis courts, eighty baseball diamonds, and three outdoor swimming and wading pools. There would be a skating rink, a zoo, an eighteen-hole golf course, thirty restaurants and cafeterias, a thousand-seat casino with formal gardens, and an open-air theater and a music grove that, together, could accommodate thirty thousand patrons. Public transit access would be via the long-proposed Utica Avenue subway extension, a key part of the so-called Second System. Emerging near Crown Street, the new line was to run down Utica Avenue and hook south at Flatbush Avenue, running from there above Avenue S and ultimately connecting with a similar extension of the Nostrand Avenue line (a later version swung down Flatbush instead to serve Floyd Bennett Field). Circulation within the vast site would be facilitated by thirty miles of walkways and nine miles of road served by circulator buses.16

The vast space was organized about a great central armature formed by what had been Gerritsen Creek, now bulkheaded and piled into an extended artificial waterway. Two miles from end to end and shaped like a giant banjo, the Long Canal and Big Pool were to accommodate a recreational flotilla including model yachts, racing shells, and the sailing canoes that had become popular in the 1920s. Lay hoped that the canal would be used for Olympic rowing trials, and even secured a tentative commitment from Columbia University to move its crew team there. To the east of the Big Pool was an Outboard Harbor; to the west—just off today’s Plumb Beach park—a boat basin with slips and moorings for hundreds of yachts. At the southern-most edge of Marine Park was the sea itself, where a two-mile stretch of new beach on Rockaway Inlet would be anchored by cavernous bathing pavilions—each large enough to handle twelve thousand bathers. Some thirty thousand trees would be planted throughout Marine Park, including quadruple rows of American elms flanking the Long Canal. To better compete with the spectacle of Coney Island, Marine would also be New York’s first park fully illuminated by electric lights, and thus open well into the night. Lay personally looked forward to nocturnal “carnivals or pageants on the water” that might be staged there. Walker’s plum was across Avenue U, in Lay’s “Playground.” There, the largest football stadium in America was to be erected, with seating for 125,000 spectators—twice the capacity of Yankee Stadium at the time. A proud Irishman, Walker pledged to name the colossus for celebrated Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne, who had recently died in a Kansas plane crash. “Not only will the principal football games of the country be held there,” promised Commissioner Browne, “but it will provide a fitting place for the Olympic Games the next time they come to the United States.”17

Charles D. Lay, Preliminary Plan for Marine Park, Brooklyn, 1931. Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University.

This was, all told, no place for idle lounging or the vita contemplativa. Marine Park would be a mighty exercise yard for Gotham’s teeming masses, a sprawling landscape of athletics, gamesmanship, and competitive sport. It was the grand culmination of a movement that began in New York in 1906 with the formation of the Playground Association of America. Searching for new ways to fortify immigrant youth against everything from “pauperism” and radical politics to exaggerated sexuality, reformers like Jane Addams, Jacob Riis, Luther Halsey Gulick, and Charles B. Stover came to see “scientific play” as the solution to a gamut of urban ills. As Dominick Cavallo has written, these progressives considered highly structured forms of recreation “a vital medium for shaping the moral and cognitive development of young people.” They believed such activities would not only strengthen bodies but—more importantly—impart a sense of moral and civic responsibility by exposing youth to “ideals of cooperation, group loyalty, and the subordination of self.” Socialization of this sort was also deemed vital to state and society, for team sports and structured play—especially for adolescents—were considered “an ideal means,” writes Cavallo, “of integrating the young into the work rhythms and social demands of a dynamic and complex urban-industrial civilization.” The playground movement eventually yielded a whole new form of American open space—what architect-sociologist Galen Cranz has called the Reform Park. In the early years of the twentieth century, parks came to be seen as instruments by which the working classes could be inculcated with democratic values, molded into upstanding American citizens. This was a radical departure from the ideals of the previous generation. The great pleasure grounds of Olmsted and Vaux—Central and Prospect parks—emphasized leisurely promenade and the passive contemplation of nature as elixirs for the ills of urban life. Banned were the very kinds of structured sport and recreation that reformers now deemed essential for citizen building. An ersatz rural landscape in the midst of the city—the old rus-in-urbe model—might have fortified Victorians against the presumed moral hazards of the city, but it would never do in a metropolis threatened by “the evils,” as Charles W. Eliot put it, “which have arisen from congestion of population.” Nor did it seem likely that the poor would be edified and uplifted by mere passing contact with their social betters in the park, as Olmsted had hoped. Parks would now have to deliver a public service, as efficiently as any other infrastructure or utility. As Cranz put it, the urban working classes—men, especially, whom reformers routinely likened to naughty children—were now seen as effectively “incapable of undertaking their own recreation.” Men’s play must now be as structured and supervised as work in the industrial city. “Deliberate, organized sports,” writes Cranz, “would ensure their exposure to a full complement of human experience, acutely needed since office and factory work was perceived as routine and dull.”18

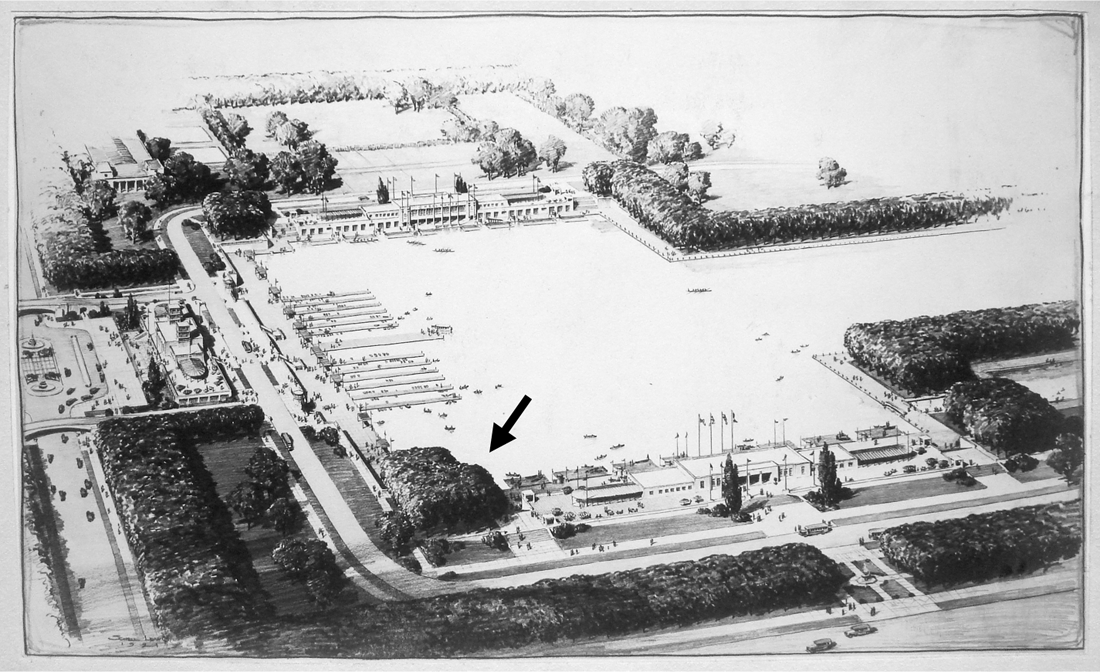

Charles D. Lay, aerial perspective of Canoe Harbor at Avenue U, Marine Park, 1931. Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University.

There were, of course, clear design implications in all this. As the ultimate expression of the reform-era park, Marine Park was as spatially disciplined as the Victorian park was languid and informal. It employed few of the spatial tricks used by Olmsted and Vaux at Prospect Park to cast an illusion of rustic removal from the city—the artful masking of views to surrounding city blocks, gradual revelation of spaces to foster a sense of mystery, provision of a variety of spatial types, from intimate rambles to open meadows, to create a kinesthetic experience of the landscape. Such sleights of hand gave way now to a spatial imperative emphasizing probity and pragmatism; the sensuous curves of Olmsted’s Anglo-romantic aesthetic yielded to one of formal architectonics and axial symmetry. Lay’s own ideal for playgrounds, outlined in a 1912 Landscape Architecture article, foretold of his Marine Park scheme. In it he called for a design “without elaborate detail and with no naturalesque planting” and striving for “a sense of beauty through . . . symmetry and order.” Likewise, Lay chose for his great people’s park a stripped-down version of Renaissance formalism straight out of Versailles. This was spatial machinery that might transform even the roughest immigrant stock into vigorous American citizens. As the Eagle approvingly editorialized in March 1932, edifying the masses called for an aesthetic of greater authority and restraint than the languorous informality of Central or Prospect Park. “It is the discipline of the plan, the fact that it isn’t hit or miss, which Mr. Lay believes will induce a sense of responsibility in those who use it—a respect for order and decency that is conspicuously absent in the habitués of public amusement parks and beaches.” Indeed, the more proximate target of Marine Park’s reformist zeal was Coney Island, ground zero of just the sort of moral mayhem and carnality that kept social reformers up at night.19

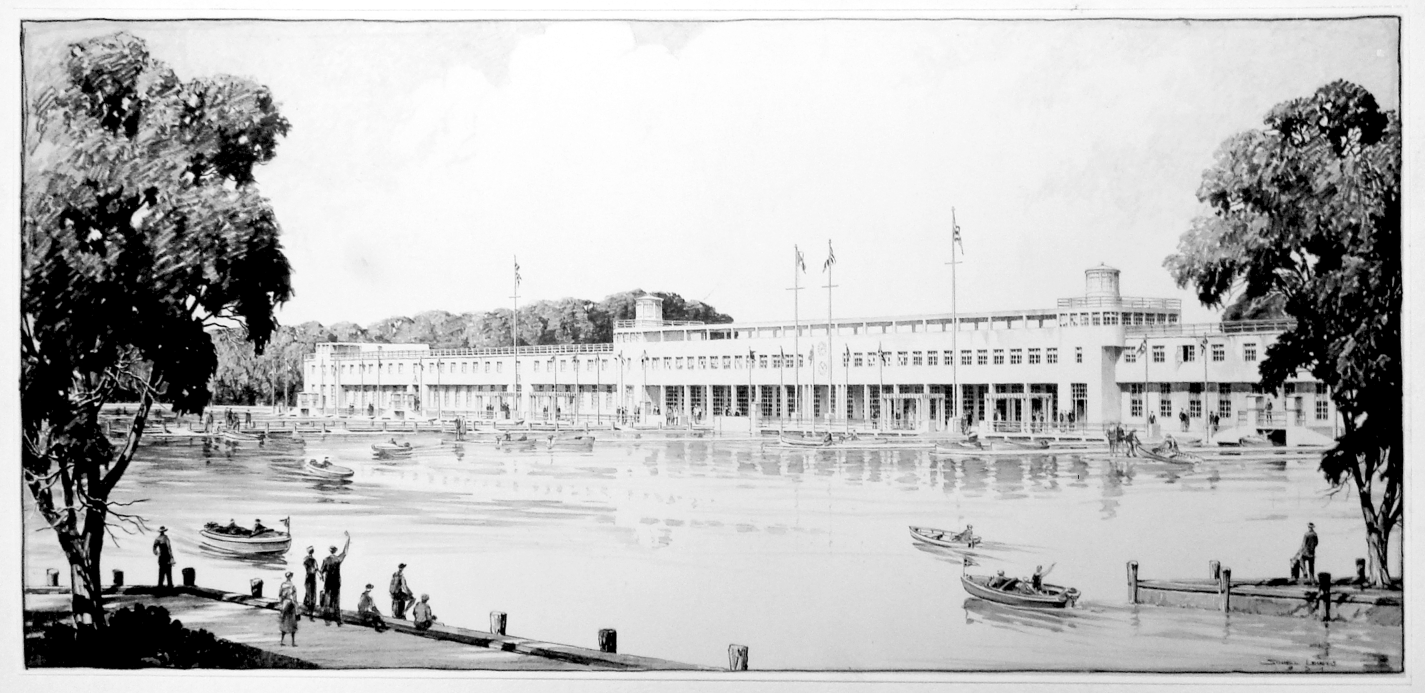

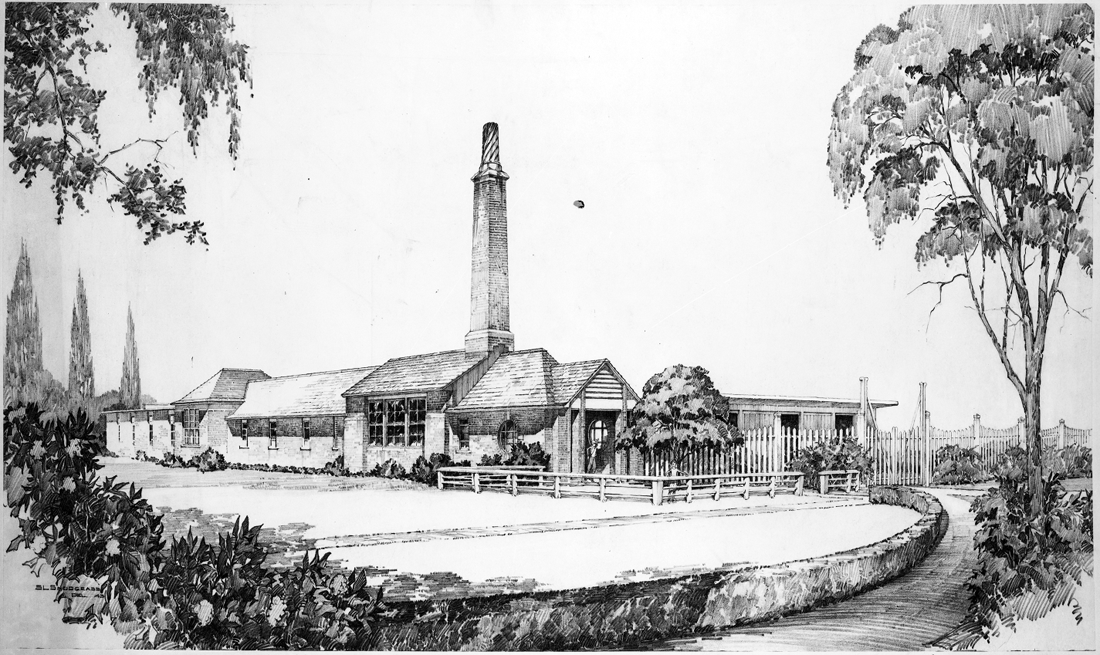

Charles D. Lay, view of Boathouse, Marine Park, 1931. Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University.

Site work on the great park commenced in the summer of 1931. From July to November, the “curving creeks and irregular pools” that Lay so admired in the estuarine landscape were smothered with up to fourteen feet of sand dredged from the bottom of nearby Rockaway Inlet. The business end of this land-making effort was the mighty Lake Fithian, largest and most powerful hydraulic dredge in the world at the time. Converted in 1927 from a cargo vessel built for the Great War, it was used to dredge flood-control cutoffs on the lower Mississippi River and to deepen the Norfolk ship channel before being towed to New York. Essentially a giant sea-vacuum, the dredge’s impeller was driven by a three-thousand-horsepower steam engine; an elephantine snout tipped with whirling cutters grubbed about the bottom like a primeval sea monster. Anchored by a pair of “spuds,” the crew of fifty-five men swung the colossal bottom-feeder back and forth through a great arc, its snout sucking up slurry and pumping it out at a velocity of twenty feet per second over more than a mile of a segmented pipeline, thirty inches in diameter and floating on pontoons. At the other end, an unholy pancake formed as the mud rushed out over the salt grasses and toward the perimeter dike. Overhead, a wheeling, shrieking cloud of gulls gathered to feast on the ejecta, which teemed with upchurned sea life. And then came the snipe—tens of thousands of them, long bills probing the mud for the rich horde below missed by the gulls. The birds were “so thick,” reported one old-timer, “that you close your eyes, fire a gun into their midst and bag about 50 . . . It’s just too bad that we can’t take our shotguns and have a little sport.” At night, the Lake Fithian could be seen by the glow of its boiler fires, a flat-water Pequod reversing the order of sea bottom and salt marsh. The snorting beast worked the bay bottom for four months, twenty-four hours day and night. All told it pumped a total of 2.7 million cubic yards of fill—enough sand to cover 422 football fields three feet deep, fill 828 Olympic-size swimming pools, or make twenty thousand children happy with a sandbox all their own.20

The Lake Fithian dredging shoals on the Hooghly River near Calcutta (Kolkata) c. 1959, shortly before its tragic capsizing. Collection of the author.

It was on a frigid Friday in 1933, six months after corruption finally forced Jimmy Walker out of office (and off to Europe, a Ziegfeld showgirl on his arm), that work finally began on New York’s first great park “keynoted to modern recreation needs.” Officials at the February 18 groundbreaking at the Whitney mansion included Lay, Commissioner Browne, and Major L. B. Roberts of the Emergency Work Bureau—a military engineer who had led surveying expeditions to central Asia and the Sudan. Shortly after two o’clock, Commissioner Browne climbed aboard a pile driver and shifted a lever to drop the hammer on the first of twelve hundred piles for the bulkhead around Lay’s canoe harbor. A great cheer went up from the six hundred workers gathered along the shore, all of whom had recently been unemployed. They were soon be joined by several thousand more. But the New Deal in New York prior to 1934 was plagued by mismanagement, poor planning, and supply shortages. By the end of the year, a lack of building material and machinery had idled two thousand Civil Works Administration laborers at Marine Park alone. But a new fusion administration took the city’s helm in January, led by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. In one of his first official acts, La Guardia appointed Robert Moses commissioner of the newly unified Parks Department. Moses lost no time getting to work, swinging like a wrecking ball through an agency calcified by years of scandal, corruption, and political favoritism. Insofar as it was the largest parks project in the city, Moses was especially concerned about the situation at Marine Park. There, not surprisingly, his staff found workers milling about campfires, playing dice, and passing around bottles of wine. They had barely enough clothes to ward off the cold wind. Robert Caro described the scene at Gerritsen Creek as “more reminiscent of a French bivouac during the Retreat from Moscow than a park reclamation project.” Moses ordered scores of men fired.21

Sewer line construction on Gerritsen Avenue, December 1932, showing vast plain of dredged sand in Marine Park. Photograph by Edgar E. Rutter. Courtesy of Paul Link.

It is a public-works axiom that projects inherited from a previous administration live short and bitter lives. If Moses had no tolerance for shovel-leaning laborers, he had less still for the patrician designer whose extravagant scheme they were building. Moses and Lay, it turns out, had a “past.” A decade earlier, the landscape architect had opposed Moses’s park and parkway plans on Long Island. Lay helped wealthy estate owners force Moses to build a long and costly diversion of the Northern State Parkway around the Wheatley Hills. Lay further alienated Moses by arguing that parkways—the very ligature of the Moses regional vision—were obsolete and “ill adapted to present needs”; for “the chief end of the motorist,” he stressed (with prescience, as anyone who’s driven the Northern State today well knows), “is to get to his destination . . . he is little interested in the scenery on the way.” More fatally still, Lay convinced voters in the town of Hempstead to defeat Moses’s first attempt to build Jones Beach, arguing that the oceanfront real estate was far too valuable to be donated to the state of New York—a “princely gift” for which Hempstead would get “nothing at all.” Thus it was a very bad turn of luck for Lay that his old nemesis was suddenly in a position of absolute authority over his Marine Park masterpiece. Moses delighted in ridiculing “Landscaper Lay” and his “preposterously formal” Marine Park scheme, boasting that “one of the first things I did was toss this ridiculous plan into the wastebasket and get rid of whatever associations there were with the landscape architect in question.” With equal contempt Moses scrapped the Knute Rockne football stadium, dismissing it as an “imitation Roman coliseum.” Moses was certain the whole Marine Park saga had been hatched by Senator Calder’s real estate cabal, starting with the Pratt and White gift—“widely heralded as a tremendous piece of philanthropy,” Moses snarked, but really just “bait to persuade the city to acquire all the surrounding property.” At the same time, he was adamant about defending Jamaica Bay, and among his many forgotten environmental victories was ending Sanitation Department plans to use its waters for dumping the city’s refuse. He also recognized that Marine Park was a vital part of the citywide park system, and assigned its replanning to his most experienced design consultants—Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano.22

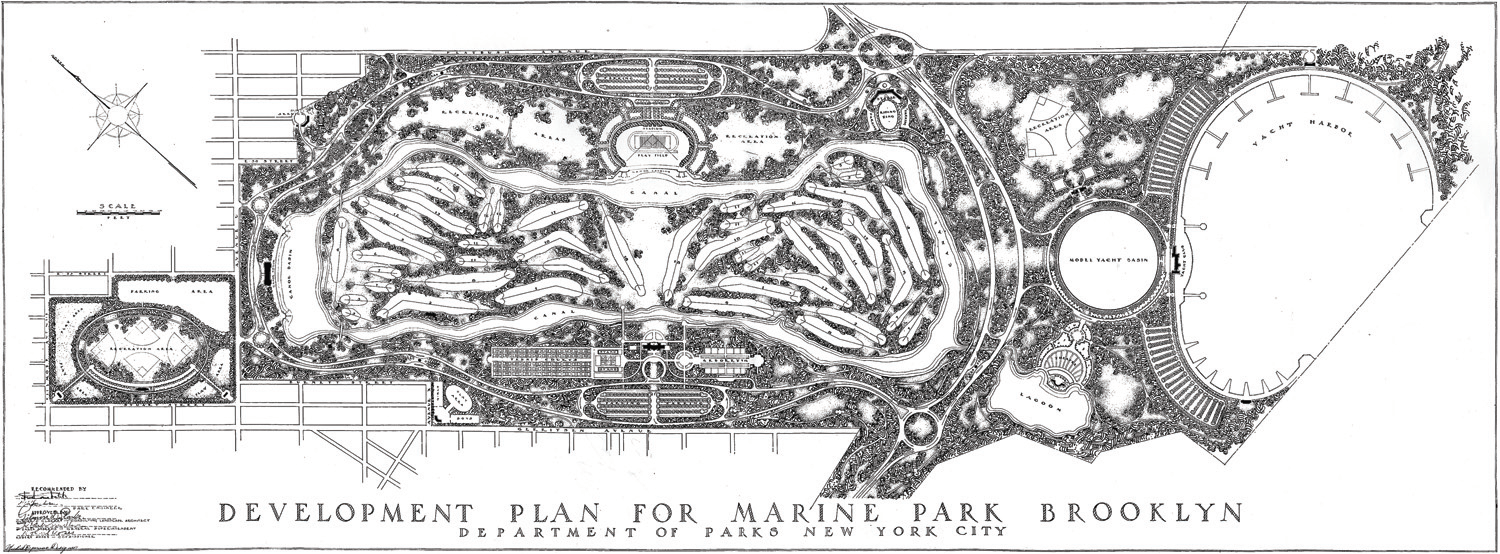

Clarke, who worked briefly for Lay after graduating from Cornell in 1913, was of course familiar with Marine Park from the Park Association kerfuffle years before. Now responsible for park design throughout the five boroughs, Clarke delegated the Marine Park job to his acolyte, Michael Rapuano. By September 1934 Rapuano had a new plan ready. Moses and Clarke presented it to a packed auditorium at James Madison High School in early September. The Rapuano plan proposed far less draconian alteration of the existing site, and even introduced some of the flowing, romantic forms wholly absent from Lay’s disciplined, formal scheme. Ironically, the new plan embraced a strategy of marshland improvement that Lay himself had advocated twenty-five years earlier but abandoned. In his 1912 Landscape Architecture essay on tidal marshes, Lay concluded that “complete filling is the most expensive way to treat a marsh, and the least satisfactory”—for both engineering and environmental reasons. He proposed instead “a compromise . . . between filling and draining, by excavating part of the marsh to make ponds or creeks, or lagoons with islands, and filling over the remainder of the marsh with the excavated material. We might call this picturesque ditching.”23 Clarke and Rapuano did precisely this, thus requiring far less bulkheading or landfilling than the earlier scheme. Lay’s grand canal was reconfigured into a sinuous waterway cleaved around an island with two golf courses. Much of the tidal marsh ecosystem would remain; so would the old Gerritsen mill, to be restored now as a museum. Other features included an arboretum of native plants and trees and a parkway loop that would enable motorists to drive themselves anywhere in the park; a second and larger motorway—what would later become the Belt Parkway—crossed the site from north to south. Not surprisingly, Knute Rockne stadium was eliminated, leaving only a ghostly impression of itself in an elliptical bicycle and running track north of Avenue U. The two-mile beach Lay had proposed was also dropped; the waters of Rockaway Inlet, Moses argued, were far too polluted for bathing.

Michael Rapuano, Development Plan for Marine Park Brooklyn, 1935. Collection of Marga Rogers Rapuano.

Moses also made Marine Park part of his administrative empire, quietly placing it under the auspices of the Marine Parkway Authority (MPA), which—like the Triborough Bridge Authority and the Long Island State Park Commission—he largely controlled. The MPA also included Jacob Riis Park—the city’s only true oceanfront park—and a magnificent art-deco lift-span bridge designed by Othmar Ammann to carry Flatbush Avenue over Rockaway Channel. Moses favored these more glamorous projects over the park he had inherited. Both beach and bridge opened in the summer of 1937, well ahead of Marine Park. Riis Park and the Marine Parkway Bridge so depleted MPA funds that Moses was forced yet again to scale back plans for Marine Park. Now even Clarke and Rapuano’s “economy scheme” proved too costly to build. “It is as clear as crystal to me now,” Moses wrote in an August 1936 staff memo, “that the plan which we announced in good faith cannot be carried out within any reasonable time, that it is far too expensive and also that its merits . . . are extremely dubious.” He even mocked his most trusted landscape architect, whose “academic” plan for Marine Park was “just another case where we were too much influenced by pretty pictures drawn by Gilmore Clarke and some of the other boys.” He now directed his more pliant staff designers—Frances Cormier, Allyn Jennings, and Clarence C. Combs (principal designer of Jones Beach)—to come up with yet another scheme for Marine Park. The new plan was as reductive of the Clarke and Rapuano scheme as that one had been of Lay’s. Moses instructed his men to simply finish the playing fields north of Avenue U, create a small boat basin by Plum Beach, and lay out a chain of “border developments”—playgrounds, ball fields, basketball courts—along Gerritsen Avenue. “For the rest,” he concluded, “I am satisfied that Marine Park should be left largely as it is.” Even the golf course would go—for it, too, was “impractical and could not possibly justify the enormous cost of fill and the destruction of a naturally attractive area.” Thus after twenty-five years of ambitious plans, the salt marsh prevailed, saved by the otherwise most ruthless builder in American history.24

Robert Moses (in white) explains plans for Marine Park to (left to right) Queens borough president George U. Harvey, Brooklyn borough president Raymond V. Ingersoll, and Federal Works Administration supervisor John M. Carmody, 1939. Brooklyn Collection, Brooklyn Public Library.

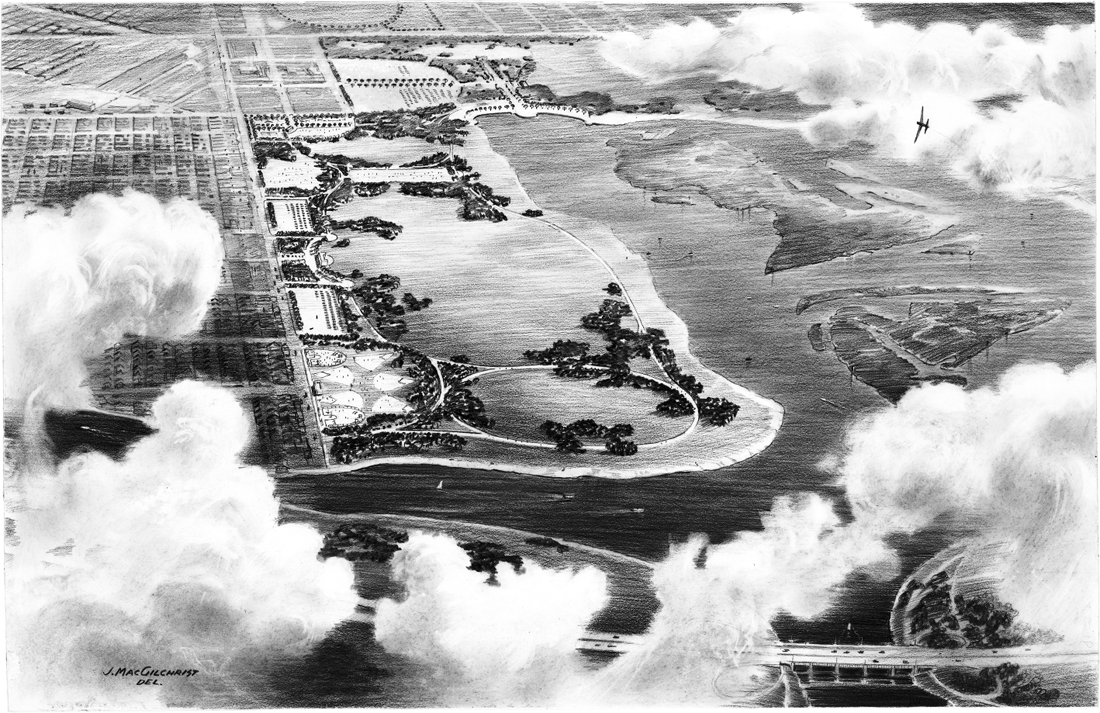

Perspective rendering of Marine Park by J. MacGilchrist, c. 1940. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Marine Park Fieldhouse, 1943, by Herbert Magoon and S. L. Snodgrass. This building was to replace a drab temporary structure on Fillmore Avenue that stood until 2008. Magoon had designed bathhouses at Jones Beach State Park, Sunset Pool, and the Crotona Play Center. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Charles Downing Lay never forgave Robert Moses for scuttling his masterpiece and did his level best to make trouble for the headstrong builder in years to come. Among other things, he helped organize opposition to Moses’s ill-conceived plans for a suspension bridge between the Battery and Brooklyn (a crossing eventually realized as the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel). Lay would never see another commission on the scale of Marine Park, but he got a nice consolation prize for all his labor—a silver medal in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Jesse Owens might have been the most celebrated participant in the infamous “Hitler games,” but it was “Landscape Lay”—not the great track star—who was the first American awarded a medal. Until 1948, art was an official class of competition in the summer Olympiad, and “Designs for Town Planning” was one of several subcategories that also included sculpture, painting, music, and literature (“Lyric,” “Dramatic,” or “Epic”). Of course, there had to be some reference to sport and athletics; this was the Olympics, after all. As the 1936 Art Section entry form put it, “Only works relating to sport will be admitted,” while those “representing a human body at rest, without apparent sport character . . . will be excluded.” A sprawling monument to fitness and competitive sport, Lay’s Marine Park plan certainly met those Olympian standards.25

By the 1970s Gerritsen Creek had become a scruffy and scofflaw place, overrun by dirt bikers and scattered with the rusting hulks of stolen cars. There were brush fires almost weekly, set by local teenagers, which the fire department dutifully attempted to quell at great taxpayer cost. The landscape seemed to mirror the city’s own bleak chaos and decline in those years. And yet despite its use as an urban dumping ground, the salt marsh retained a certain austere majesty. On autumn after-noons, the teal-blue waters of the tidal inlet would stretch to the horizon, framed by hillocks bearing a tawny mane of Phragmites australis—an enterprising invasive species that colonized the nutrient-poor fill dumped on the site over the decades, excluding most native flora and fauna and dramatically altering the natural ecosystem. At high tide, not a trace of Charles Downing Lay’s titanic playground can be seen; but come back when the moon has sucked low the seawater, and rows of mussel-encrusted pilings emerge revealing the bulkhead line of his canoe harbor and grand canal. On the shores above, time and space appear to be moving in reverse; for in recent years the Corps of Engineers and the New York City Parks Department have reversed a century of environmental degradation by scraping away both the phragmites and the fill they’ve colonized—a exercise in ecological restoration much like a great weeding operation. Tucked beneath a fresh layer of topsoil and planted with native marsh grasses, the Gerritsen estuary is today one of fifty-one Forever Wild nature preserves throughout New York City, anchored by the pleasing, low-slung contours of the Salt Marsh Nature Center. In good time, this marginal place will again resemble the pristine landscape that Danckaerts and Sluyter once roamed; that sustained the Leni Lenape for a thousand years before them; that has outlasted the quondam schemes of dreamers and visionaries alike.

Silver medal of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. Cadbury Research Library—Special Collections, University of Birmingham.

Concrete bulkheading for Charles D. Lay’s Long Canal stacked on the east side of Gerritsen Creek in 1988. They were removed a decade later when the Salt Marsh Nature Center was built. Photograph by author.

Gerritsen Creek from the Salt Marsh Nature Center, November 2012. Taken a month after Hurricane Sandy; debris in tree at right indicates high point of storm surge. The taller pilings in back outline the eastern corner of Lay’s canoe harbor. Photograph by author.