CHAPTER 4

YANKEE WAYS

A system of grounds . . . designed for the recreation of the

whole people of the metropolis.

—FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED AND CALVERT VAUX, 1866

If Brooklyn gave New York its first de facto urban park in Green-Wood Cemetery, it had to wait another generation for a great, truly public playground of its own. Prospect Park was not the first large urban park of nineteenth-century America—Manhattan got that, of course—but it was the finest of its age, the crowning achievement of the same creative polymath who gave us Central Park. Frederick Law Olmsted was a wanderlusting Yale dropout from Hartford who, before the age of forty, had sailed to China, apprenticed with farmers in Connecticut and upstate New York, run an experimental spread of his own that his father bought for him on Staten Island, Tosomock Farm, edited Putnam’s, and published three books of his own—one of which, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States (1856), galvanized the abolitionist movement and thus helped change the course of history. Restless and churning with ambition, Olmsted was the product of a patrician lineage—reaching back to the Puritans and filled with Revolutionary heroes (including one who died on a prison ship in Wallabout Bay)—that augured distinction in some profession, if not greatness. That this would come in a field of his own making, landscape architecture, few could have presaged before 1855. Olmsted had no formal degree in architecture or the design arts, knew little about plants beyond those he farmed, and studied engineering only briefly with a Massachusetts divinity student who taught surveying to pay the rent. Olmsted knew only that he wanted to do something, and something good. “I want to make myself useful in the world,” he confided to classmate Frederick Kingsbury in 1846, “to make others happy.”1

Olmsted’s formal education may have been haphazard, but the peripatetic youth read voraciously, devouring Emerson, Ruskin, Lowell, Timothy Dwight’s Travels in New-England and New-York, William Gilpin’s Forest Scenery, and An Essay on the Picturesque by Uvedale Price—the latter two of which he would later force on all who came to work in the Olmsted office, to be read “seriously, as a student of law would read Blackstone.”2 And before even books was the landscape itself. Olmsted developed a keen and probing eye, tutored on long childhood jaunts through field and forest with his parents—“really tours,” he later wrote, “in search of the picturesque” that took him to some of the most scenic places in New England and New York. “I had been driven over most of the charming roads of the Connecticut Valley and its confluents,” he recalled of his boyhood years, “through the White Hills and along most of the New England coast.” Olmsted became a critical observer of place and landscape, absorbing lessons that no school could have provided at the time (there were no landscape architecture programs then; the first, at Harvard, would be founded by his son in 1900). “I took more interest than most travelers do in the arrangement and aspect of homesteads,” he wrote, “and generally in what may be called the sceneric character of what came before me.”3

Olmsted eventually gained the confidence to make “modest practical applications” of the lessons he absorbed over the years—“applications . . . to the choice of a neighborhood, of the position and aspect of the homestead, the placing, grouping and relationships with the dwelling of barns, stables and minor outbuildings.” He found that even the humblest rural compound could gain from wise spatial planning—“that even in frontier log cabins,” he wrote, “a good deal was lost or gained of pleasure according to the ingenuity and judgment used in such matters.” There were also, Olmsted reasoned, “lines of outlook and of in-look,” the shaping of views by adding or removing plant material, the importance of “unity of foreground, middle ground and back ground” and the choreography of overall scenic effect—both from without and “within the field of actual operations.” Trees, too, were muses from earliest youth. One of Olmsted’s fondest childhood memories was seeing a towering column of American elms that his elderly grandfather, Benjamin Olmsted, had planted as a child in the 1760s. Marveling at how once-scrawny whips could become such giants, the boy yearned to set out elms of his own. “I wanted my father to let me help him plant trees and he did,” Olmsted wrote, “but they were not placed with sufficient forecast and have since all been cut down.”4

Forecast—not merely sufficient, but prescient, even prophetic—would be the leitmotif of Olmsted’s long and fruitful career. It began in earnest in September 1857, when he applied for the superintendent job to build a “central park” in the middle of Manhattan. Apprised of the political nature of the project and its Board of Commissioners, Olmsted pulled all the strings he could, fortifying his application with “a number of weighty signatures”—including those of Peter Cooper and Washington Irving. Even so, he barely made the grade. The project engineer, a gifted but jinxed West Point graduate named Egbert Ludovicus Viele, took an immediate dislike to the wellborn Yankee. When Olmsted called to present his qualifications, Viele made him wait most of an afternoon before trying to dodge out of the office. The tenacious Olmsted followed Viele to his streetcar, finally having a chance to plead his case in front of the weary commuters—only to have Viele tell him he preferred to hire a “practical man.” Nor was the board much swayed by Olmsted, who won its approval by just a single vote—cast by a commissioner opposed to the candidate but impressed nonetheless with his endorsement from the great fabulist. With Viele as his boss, Olmsted gradually shaped the park’s army of laborers—all of whom owed their jobs to graft and were accustomed to doing little work—into an effective field force. Thus far, the vast project had been guided by Viele’s survey and site plan. But the Viele plan was a holdover from the first Central Park Commission, a body appointed by Mayor Fernando Wood and subsequently dissolved. The present commission, answering to the governor, chose to wipe the slate clean. They were quietly encouraged in this by a young English architect named Calvert Vaux, who had worked with the Hudson Valley landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing until the latter’s tragic death in 1852. Downing had spent years advocating for a great New York park, and Vaux felt duty bound to make sure its design met his late friend’s high standards. He was fiercely critical of the Viele plan, pointing out that it would be “a disgrace to the City and to the memory of Mr. Downing to have this plan carried out.” Vaux’s campaign was successful: in October 1857 the commissioners tossed the Viele plan and announced a competition for a new park design. Vaux, keen on entering the contest himself but unfamiliar with the site, wisely sought to partner with Olmsted, whom he had met through Downing. Olmsted initially declined the invitation out of respect for Viele, who was enraged that his plan—prepared at his own expense—had been unceremoniously scuttled (he later sued the city and was awarded damages). Olmsted changed his mind only after Viele “took occasion to express, rather contemptuously, complete indifference as to whether Mr. Olmsted entered the competition or not.” Thus did the hapless Viele help make himself the Salieri to Olmsted’s Mozart.5

Olmsted and Vaux worked nights and weekends on their entry at Vaux’s Gramercy Park home, where family and friends were enlisted to help with the drawing. That Olmsted knew the rocky site so well proved invaluable, for he was able to clarify details of topography missing from the survey maps provided to competitors. To further inform their proposal, Olmsted and Vaux would rove the vast site “together by moonlight to discuss features of the plan, with the land before them.” Their proposal, the “Greensward,” was completed just hours before the deadline, the last entry to be submitted. Olmsted and Vaux won the competition, of course, their plan selected from a field of more than thirty submissions. Its genius was its unity, conceived as a whole and orchestrated like a symphony. “The Park throughout,” wrote Olmsted and Vaux, “is a single work of art, and as such subject to the primary law of every work of art, namely, that it shall be framed upon a single, noble motive, to which the design of all its parts, in some more or less subtle way, shall be confluent and helpful.” Their park was charged with a simple twofold purpose: to boost the physical health of city dwellers—especially the poor and working classes—with “pure and wholesome air, to act through the lungs”; and to inoculate New Yorkers against the presumed moral ills of urban life by treating them with a distillate of nature, a concentrated dose of rural landscape. It would work by providing “objects of vision” that countervailed “those of the streets and houses,” bringing remedial relief “by impressions on the mind and suggestions to the imagination.” As Olmsted explained, the prevailing purpose of the park was

to supply to the hundreds of thousands of tired workers, who have no opportunity to spend their summers in the country, a specimen of God’s handiwork that shall be to them, inexpensively, what a month or two in the White Mountains or the Adirondacks is, at great cost, to those in easier circumstances.

And the need for such a prophylaxis would only increase; for “the time will come,” Olmsted foretold, “when New York will be built up, when all the grading and filling will be done, and when the picturesquely-varied, rocky formations of the Island will have been converted into formations for rows of monotonous straight streets, and piles of erect buildings.” Only then, with the city grown up all around Central Park, surrounding it with “an artificial wall, twice as high as the Great Wall of China,” would its role as a mighty green antidote to the metropolis be fulfilled.6

This notion that cities are best paired with nature, that the artifice of urbs should be annealed by rus, is one of the founding principles of American urbanism. Its roots run deep, to the Founders themselves. Most were literate, landed gentlemen, well tutored in the classics, who looked to Europe as the arbiter of all things civilized but nonetheless regarded its great cities as something best kept away from America’s vernal shores. They believed that cities were antithetical to the American democratic experiment, that the new republic would flourish best if its citizens lived close to the land, each peaceably tilling his own soil. As John Adams explained in 1786, “a people living chiefly by agriculture, in small numbers, sprinkled over large tracts of land . . . are not subject to those panics and transports, those contagions of madness and folly, which are seen in countries where large numbers live in small places.” Urbanism of the Old World sort—especially of industrializing London and Manchester, with their grim factories and exploited workers—must be avoided at all costs. No one made this case more forcefully than that Lord of Monticello, Thomas Jefferson, to whom farmers were angels in overalls. “Those who labour in the earth,” he wrote in Notes on Virginia, “are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people.” To Jefferson, agrarians kept alive the moral flame of civilization. “The mobs of great cities,” on the other hand, “add just so much to the support of pure government,” he wrote, “as sores do to the strength of the human body.”7

In the Jacksonian era, a hefty dose of nationalism was added to this mix. In its wild beauty and seeming infinite abundance, American nature came to be regarded as a defining element of national identity—a possession at least equal in value to the Old World’s vast legacy of cultural achievement. “If we have neither old castles nor old associations,” wrote Downing, “we have at least, here and there, old trees that can teach us lessons of antiquity, not less instructive and poetical than the ruins of a past age.” By now, American cities were growing—Jefferson and Adams notwithstanding—like weeds in a field of manure, making it more urgent than ever that hallowed “rural values” be sustained in the face of urbanization, that the chimera of “Nature’s Nation” be sustained. New strategies were contrived to bring town and country into harmonious union, to temper the city with a tincture of nature. Nothing seemed to accomplish this more effectively than planting forest trees on city streets—and not just any tree, but that fast-growing denizen of the lowland woods, the American elm. The tree, Ulmus americana, had long been a presence in the New England landscape, and was planted in rows on roads and lanes in the Connecticut River valley as early as the 1780s. But it wasn’t until the 1840s, as a “new craving for spatial beauty” swept across the region, that the practice of planting street elms became institutionalized and spread throughout New England.8

The drivers of this movement were improvement societies founded by civic-minded townsfolk to carry out a variety of betterment and beautification projects. They were inspired by the same romanticism that gave us the rural cemeteries, and fortified by popular writing on horticulture and landscape improvement by Downing and others. But the village and town improvers were also responding to something darker—the effects of economic decline. With the region’s rocky soils and harsh winters, farming in New England was never easy. After the Erie Canal opened in 1825, its agriculturalists were suddenly competing with upstate New York and eastern Ohio, fertile regions now plugged in to New York City. Eastern markets were soon flooded with cheap produce, sending New England’s rural economy into a tailspin. Many Yankee farmers headed west themselves, while the best and brightest youth of its towns and villages left for the region’s booming cities. “What is it that is coming over our New England villages, that looks like deterioration and running down?” asked Berkshire minister Orville Dewey; “Is our life going out of us to enrich the great West?” Perhaps, the improvers reasoned, the youth might stay if the townscape were made newly appealing. The village improved and enhanced might “instill in the youth that love of beauty and morality which would enable him to withstand the attraction of urban wealth and vice.” Spatial beauty, in other words, could be weaponized to counter the toxic effects of a failing economy.9

The almost universal activity of the early village improvement societies was planting elms, a fact attested to by the name of the first such group in New England—the Elm Tree Association of Sheffield, Massachusetts. Yankee improvers chose the elm for a number of reasons: it was easily obtained in any lowland forest, transplanted easily, grew like a rocket, and was tough as nails—at least in an age before asphalt, buried utilities, and Dutch elm disease. But more than anything, it was the extraordinary beauty of the American elm that made it such a universal favorite, endowed with formal and aesthetic properties—a high spreading crown, a fountain-spray tumble of branches and limbs, small leaves that allow dappled sunlight to reach the ground—that made it ideal for street and city use. These qualities were identified early on by European botanical explorers. The Milanese botanist Luigi Castiglioni, who traveled extensively in North America in the 1780s, described the American elm as “remarkable for the beauty of its branches, which are numerous, very wide-spreading and pendant”—features that made it “preferable to the European for . . . avenues and other ornamental plantings.” A French contemporary, François André Michaux, admired the elm’s “long, flexible, pendulous branches, bending into regular arches and floating lightly in the air.” He allowed that while the sycamore might exceed it in girth and “amplitude of its head,” the elm possessed “a more majestic appearance . . . owing to its great elevation, to the disposition of its principal limbs, and to the extreme elegance of its summit.” This, wrote Michaux, was “the most magnificent vegetable of the temperate zone.”10

An immense American elm on the Elmwood Farm in Conway, New Hampshire, 1930. The tree was planted as a one-inch whip by Leavitt Hill in 1780, and was for many years the largest in New England. Photograph by Ernest Henry Wilson. Photographic Archives of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University.

The New England of Olmsted’s youth was a paradise of elms. The tree was so extensively planted throughout the region, so celebrated in its literature and art, that it had become an abiding symbol of New England—a sylvan counterpoint to the whitewashed church steeple. “In no other part of the country,” wrote Charles Sprague Sargent of the Arnold Arboretum, “is there a tree which occupies the same position in the affection of the people as the Elm does in that of the inhabitants of New England.” Brooklyn’s Henry Ward Beecher, firebrand minister of Plymouth Church, was a lot more effusive: “The Elms of New England! They are as much a part of her beauty as the columns of the Parthenon were the glory of its architecture.” To him, elms were “tabernacles of the air” that consecrated the profanest street. “We had rather walk beneath an avenue of elms,” he confessed, “than inspect the noblest cathedral that art ever accomplished.” The queen of New England’s elm-tossed towns was New Haven. By the 1850s it had become as famous for its trees as for Yale College, exemplary of a uniquely American kind of city—a city in harmony with nature, where rus and urbs were one. Its pièce de résistance was Temple Street, on the New Haven Green. Though the thoroughfare was named for its three houses of worship, its cloistral elms ultimately stole the show—overshadowing the churches both literally and figuratively. As the trees matured to form a great vaulted roof overhead, the street became a temple itself—“a temple not built with hands, fairer than any minster.” New Haven was a must-see stop on the American grand tour. Emmeline Wortely, a visiting Englishwoman, noted that the “profusion of its stately elms” made New Haven “not only one of the most charming, but one of the most ‘unique’ cities I ever beheld.” Charles Dickens visited New Haven on his celebrated 1842 tour of the United States. He praised the city’s “rows of grand old elm-trees,” which seemed “to bring about a kind of compromise between town and country; as if each had met the other half-way, and shaken hands upon it.”11

Temple Street, New Haven, c. 1865. New Haven Colony Historical Society.

Elm Street was a Yankee invention, but it hardly stayed put. It was sped afield by the same “westward transit of New England culture,” in the words of Whitney Cross, that diffused so many Yankee traditions—from jack-o’-lanterns and Thanksgiving to the Cape Cod house.12 The spread of the urban elm forest tracked closely that of the New England diaspora. Upstate New York was directly in its path, and by the late nineteenth century its principal cities—Albany, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo—were as heavily elmed as those in New England. So too hundreds of towns and cities across the Midwestern states. New York City, with its Dutch heritage and polyglot culture, proved more resistant. Certainly Ulmus americana could be found in the city’s parks, but the tree never quite entered the cultural bloodstream the way it had in New England. There is but a single “Elm Street” within the bounds of New York City today—hidden on the north shore of Staten Island—while two others were long ago lost to name changes. A mile-long Elm Street once ran through the Bushwick section of Brooklyn but was made an extension of Hart Street sometime before 1898. Another Elm Street extended from Chambers Street to Broome Street in Manhattan, most of which was renamed Lafayette Street around 1900. Only a tiny (treeless) fragment survived near City Hall, but even that was later rubbed out—rechristened Elk Street by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to honor his fraternal lodge. Queens has Elmhurst, of course—contrived by a real estate developer in 1897—while Elm Avenue in Flushing was not laid out until the 1920s. There is a short Elm Place in the Fordham section of the Bronx, and an even shorter one in Brooklyn (all of 370 feet long). Historically, the greatest concentration of street elms on Long Island was in those Anglo east-end towns—Bridgehampton, Sag Harbor, East Hampton—originally settled by Yankees and closer in spirit to New England than to New York.

Species aside, both New York and Brooklyn lagged behind New England in planting public trees—and in taking up the causes of betterment and beautification generally. As late as 1891, the enchantingly named Tree Planting and Fountain Society of Brooklyn could describe that city’s sylva as “creatures of chance, with little taste in selection and less care in planting.” On the other hand, what trees New Yorkers did set out in parks and public ways suggests a more catholic attitude about species relative to New England, with its single-minded passion for the native elm. Indeed, one of the most popular street trees in nineteenth-century New York was a Chinese species, the ailanthus or Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima). Frederick Van Wyck, chronicler of Keskachauge whom we met in chapter 1, recalled fifty-foot-tall ailanthus trees on “all the residential side streets, and also up Fifth Avenue” in Chelsea in the 1860s.13 In Greenwich Village, ailanthus trees “formed the principal umbrage” of Washington Square Park, as related by the narrator in the 1880 Henry James novel Washington Square. Its day in the sun was short, however; for the very plantsmen who popularized the ailanthus were soon demonizing it as a foul-smelling alien. The denunciations could be meanly racist: Andrew Jackson Downing called the ailanthus a “petted Chinaman” with the “fair outside and the treacherous heart of the Asiatics.”14 It was our Connecticut Yankee, Frederick Law Olmsted, who made the American elm part of the New York scene. A more fitting emissary could hardly be found; for not only was Olmsted a child of the Connecticut River valley—birthplace of “Elm Street” in America—but he had elms in his blood, so to speak. The name Olmsted, which first appears in the Domesday Book of the County of Essex in 1086, is a variant of Elmsted, a parish in the Hundred of Tendring from which the Olmsted clan hailed. As explained in a 1912 genealogy on the Olmsted family, Elmsted is a Saxon name that literally means “the place of Elms,” evidently because the landscape there was once “remarkable for the growth of trees of that kind.” In New York, Olmsted would re-create New Haven’s Temple Street—“grandest arch of trees on the globe”—in the Central Park Mall. And in Brooklyn, as we will see, he would lay out the longest elm-lined streets in America.15

The man who lured Olmsted and Vaux across the East River is one of the unsung heroes of New York’s urban landscape—James S. T. Stranahan. Stranahan is to Brooklyn what Andrew Haswell Green was to Manhattan. Green, whom we met in the introduction, drafted the 1897 consolidation plan that created the Greater City of New York—an initiative that had Stranahan’s full backing. As comptroller of the Central Park Commission, Green had authority over the entire park project. He was a deeply principled public servant who defended the park from plunder at the hands of “political harpies ready to pounce on it at the slightest relaxation of vigilance.” But Green was also obstinate and humorless, intolerant of dissent, and unable to “delegate plenary powers to subordinates . . . and refrain from dictatorial interference in the details of their work.” First among his victims were Olmsted and Vaux, whose constant quarrels with Green ultimately led both men to sever ties with the project. Brooklyn was a very different story. The political culture there was, if anything, even more crooked than New York’s. But in Stranahan, Olmsted and Vaux found both a public official with the mettle to keep graft at bay and a patron who understood the importance of artistic freedom. From the start, their relationship was one of mutual esteem and admiration. To Stranahan, Olmsted and Vaux were “the ablest landscape architects in this or any other country.”16

James S. T. Stranahan monument, Prospect Park, 1891. Sculpted by Frederick William MacMonnies on a pedestal by Stanford White. Photograph by author, 2018.

A native of Peterboro, New York, Stranahan moved to Brooklyn in 1845 to find his fortune with the Atlantic Dock Company, developer of Brooklyn’s first deepwater port (in present-day Red Hook). He subsequently served as an alderman and was elected to Congress in 1855. Four years later, legislation passed in Albany authorizing “the selection and location of certain grounds for Public Parks” in the city of Brooklyn. After a lengthy process in which citizens were “invited to submit their opinions,” three principal sites were chosen by a commission—one on the Queens line in Ridgewood that included a reservoir then used for Brooklyn’s water supply (today’s Highland Park); a second in Bay Ridge that afforded “magnificent views of the bay” (now Dyker Beach Park and Golf Course); and a third on the moraine near Flatbush known as Prospect Hill, where much of the Battle of Brooklyn took place. The commissioners pointed out that parks at these three locations, chained together by a “grand drive or carriage road,” would create an amenity far greater than the sum of its parts—“a public attraction unsurpassed . . . in the world.” This, as far as I am aware, is the very first mention of a system of parks and open space in the United States—an idea Olmsted himself would run with first in Brooklyn, as we will see, and later in Buffalo (1868) and Boston (1878).17

Though not their official charge, the 1859 commissioners were clearly also searching for a single major site for a park like the one then under way in Manhattan. And while “no single location for a great central park, suitable both to the present state and future growth of the city, presented itself,” the commissioners concurred with public opinion that Prospect Hill—with its rolling meadows, old-growth woods, and “commanding views of Brooklyn, New York, Jamaica Bay, and the Ocean beyond”—would do well for the purpose. On April 17, 1860, an act was passed in Albany “to lay out a Public Park and a Parade Ground for the city of Brooklyn.” A second commission was appointed, with Stranahan as its president. Its charge was to give Brooklyn a great landscaped park like the one in Manhattan—“a public place to be known as Prospect Park.” This is, of course, a wonderful example of bantam-weight Brooklyn jabbing at its mighty next-door neighbor—Gotham’s second city eagerly straining to upstage the first. What no one anticipated, least of all Stranahan and the Board of Commissioners of Prospect Park, was that the Brooklyn project would end up the greater of the two parks—indeed the finest and most visionary work Olmsted and Vaux would ever create. But they were not, alas, the first to be hired for the job. In a redux of the drama that had played out earlier in Manhattan, it was the ubiquitous Egbert Ludovicus Viele whom Stranahan first brought on to execute both a survey and a ground plan for the vast Brooklyn site.18

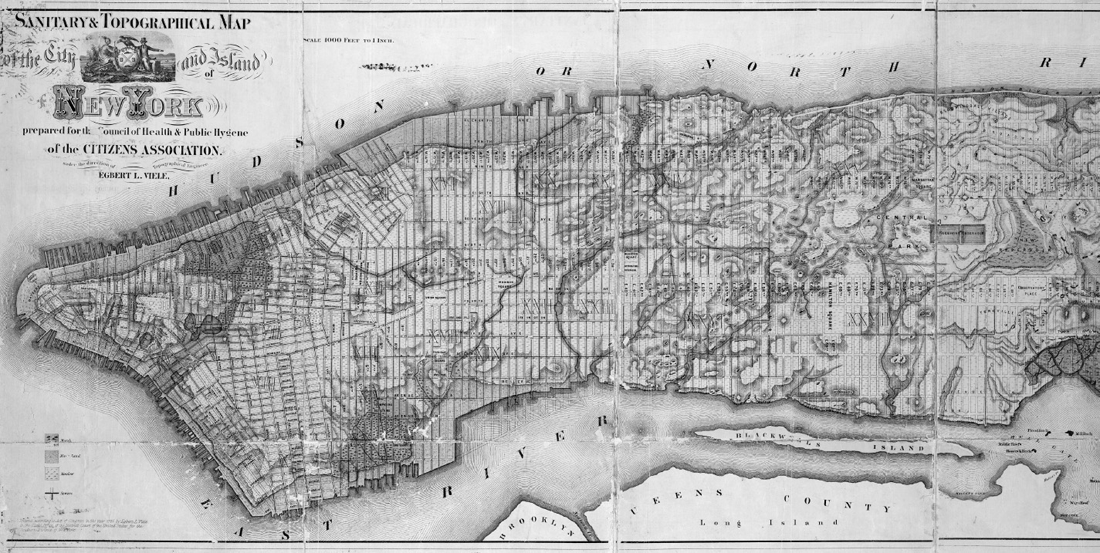

But Viele once again failed to rise to the occasion, producing an artless and uninspired piece of work. Ostensibly looking to the site’s “natural topographical features” as a basis for improvement, he applied “the skillful hand of UNPERCEIVED ART” to make nature’s “blended beauties . . . more harmonious.” This meant, Viele lectured, “the cautious pruning of trees, the nice distribution of flowers and plants of tender growth, the introduction of the green slope of velvet lawn.” Ever the engineer, Viele spent six pages discussing drainage details, and another five on “theories of manuring.” But his real flaw was accepting the park site as given, with hundred-foot-wide Flatbush Avenue piercing its heart, instead of recognizing that it would be fatal to his very own declaration of the park’s purpose—“as a rural resort, where the people of all classes, escaping from the glare, and glitter, and turmoil of the city, might find relief for the mind.” Split like Solomon’s baby, Viele’s Prospect Park would have in reality been two middling parks forever divided by a busy urban thoroughfare. It’s not clear whether Viele simply lacked the vision to anticipate that Flatbush might be more than a country lane, or if—soldier before all—he was just following orders. Viele was a complicated soul, a man of old Dutch stock proud of his trace Iroquois ancestry, despite having eagerly fought in the Indian Wars. Ironically, he was Olm-stedian in many ways—a politically astute sanitary reformer who helped create New York’s first Board of Health; a naturalist who could write lyrically about spiders and moths (“little messengers of the night”); a proficient engineer who conceived the Harlem Ship Canal. Viele’s spectacular 1865 Sanitary and topographical map of the City and Island of New York is still consulted on major building projects. But as Viele himself often put it, he was a “practical man” who approached the world as an engineering problem and lacked “the springing imagination,” as M. M. Graff put it, “that distinguishes an artist from an artisan.” He had minimal knowledge of aesthetics, and his plans for both the New York and Brooklyn parks lacked any sense of spatial structure, hierarchy, or sequence—elements vital to a large urban landscape.19

Detail of Egbert L. Viele, Sanitary and topographical map of the City and Island of New York, 1865. The New York Public Library.

Thankfully Brooklyn was spared a Viele park, this time by the winds of history. The Civil War began three months after Viele submitted his Prospect Park plan. He answered the first call for volunteers, tendering his resignation to the Board of Commissioners to take command of Company K of the Seventh New York Militia. Viele’s war service was distinguished. He helped open the Potomac River to Washington, served as military governor of Norfolk, Virginia, and participated in the siege of Fort Pulaski on the Georgia coast—defended, ironically, by a distant Southern kinsman of his Central Park nemesis, Confederate colonel Charles Hart Olmstead.20 Viele returned to Brooklyn after the war only to find that Calvert Vaux had been there already. Stranahan had been unsatisfied with Viele’s plan and reached out to Vaux; the men met in early January 1865. Vaux immediately began lobbying Olmsted—who had taken an ill-starred job in California managing the land holdings of the Mariposa Mining Company—to join him back in New York for this exciting new commission. He delivered a preliminary report to Stranahan and the park commissioners in February, and was hired that June to draft a new plan for the park. Begged, cajoled, and bullied by Vaux, Olmsted returned from the West Coast that November. Their Prospect Park report was delivered in January 1866.

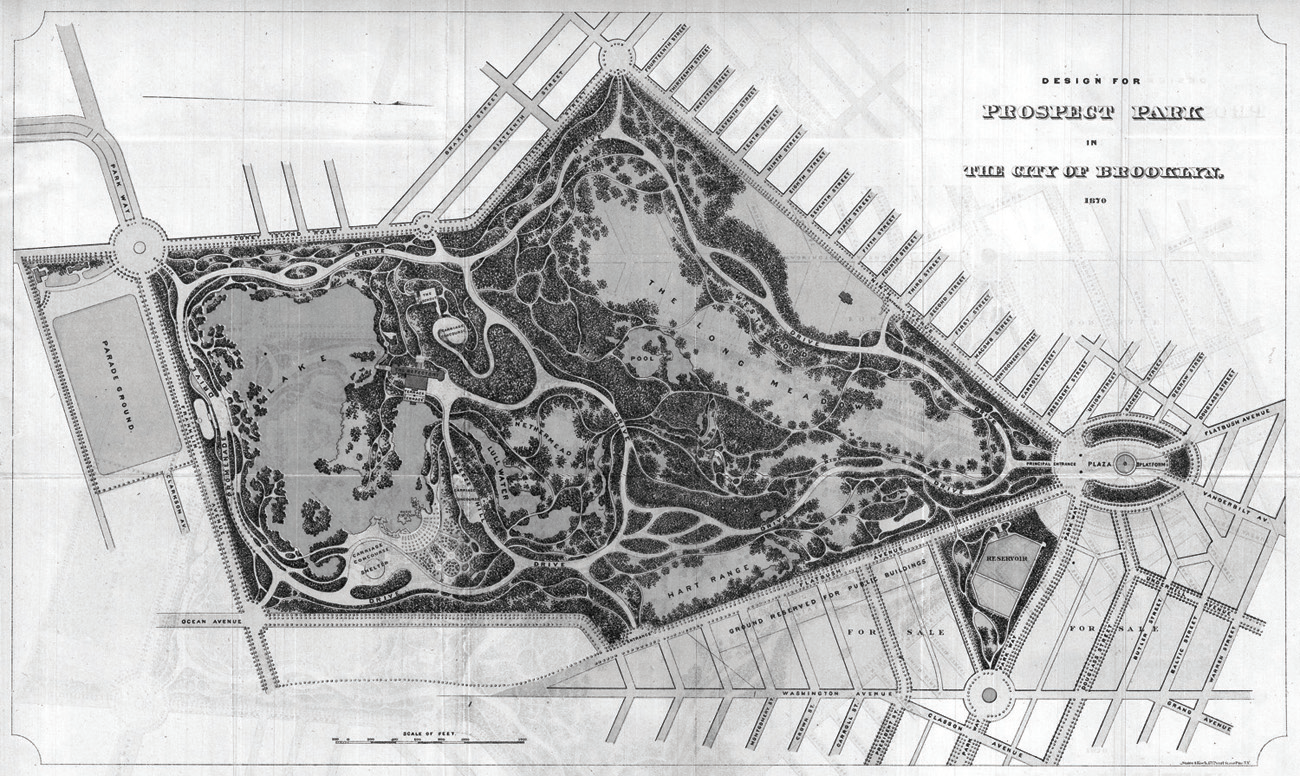

Contrary to Viele’s approach, their very first point was that the “inconvenient shape” of the site—particularly its “complete bisection . . . by a broad and conspicuous thoroughfare”—effectively made a great park impossible. “It is obvious that this division,” they wrote, “must seriously interfere with the impressions of amplitude and continuous extent” vital to any urban parkscape. Their first recommendation, then, was that the entire site east of Flatbush Avenue—the area today encompassing the Botanic Garden, Brooklyn Museum, and Brooklyn Public Library—“be abandoned for park purposes.” They then urged the commissioners to extend the park by acquiring additional lands south of the original site—a “broad plain, overlooked on the park side by the highest ground in the vicinity” that they suggested would be ideal for a lake. Turning to the park’s internal design, the partners sketched out a theoretical basis for their proposal. “A scene in nature is made up of various parts,” they explained, each with an “individual character and its possible ideal.” Mere imitation of nature would never suffice, nor could chance alone be relied upon to gather in harmony “the best possible ideals of each separate part.” Design, however, could very well bring it about. “It is evident,” they asserted, “that an attempt to accomplish this artificially is not impossible,” so long as it was predicated on “a proper study of the circumstances.” “The result,” they added, “would be a work of art.” All this predictably set off the volcanic Viele more, who accused Olmsted and Vaux of once more copying his work and attempting “to defraud me of the credit due for the first conception of the Park and its plan of improvement.”21

Unlike the rocky, soil-bare Central Park site, the three-hundred-acre spread in Brooklyn needed little coaxing to become a lush pastoral landscape. Their objective again was to create a place that provided a sense of escape from the “cramped, confined and controlling circumstances of the streets of the town”—that conveyed to the city dweller “a sense of enlarged freedom.” The park would deliver recuperative benefits for both body and mind—giving the lungs “a bath of pure sunny air” while granting the mind “rest from the devouring eagerness and intellectual strife of town life.” Pulling this off required scenery of “tranquilizing and poetic character,” which Olmsted and Vaux created using the same tripartite arrangement of space employed at Central Park—“three grand elements of pastural [sic] landscape.” These included a hilly district “shaded with trees and made picturesque with shrubs” and reminiscent of mountain scenery (like the Ramble in Central Park); a lake district on the low plain south of the original site boundary; and, most importantly, a meadow district with a broad expanse of turf configured by grading and the judicious addition or removal of trees to conceal its full extent from immediate view. This, reasoned the designers, would impel the visitor forward by appealing to that natural desire to discover what lies just beyond the bend. “The observer, resting for a moment to enjoy the scene . . . cannot but hope for still greater space than is obvious before him,” Olmsted and Vaux explained; “The imagination of the visitor is thus led instinctively to form the idea that a broad expanse is opening before him.” The keen awareness of space and sequence, wholly lacking in Viele’s work, is what truly distinguishes the Olmsted and Vaux scheme for Prospect Park. Their spatial genius is nowhere more powerfully evident than at the approach to the park from Grand Army Plaza. The idea was Vaux’s, clearly noted—“Principal natural entrance from Brooklyn”—on a rough sketch sent to Olmsted in California. From the street one is delivered into the park via a narrowing path to Vaux’s Endale Arch. Its vaulted brick tunnel, dark and close, creates a palpable—and unsettling—sense of compression. But it is fleeting: at the far end is a window of daylight; one spies a glimpse of green. As you hasten through Vaux’s venturi, the floodlit opening progressively dilates, until you are delivered with a sudden, almost orgasmic sense of release into the Long Meadow. The vast space unspools before you, peopled with strollers and picnickers, curving seductively out of sight and beckoning you forward into its full embrace.22

Future site of Prospect Park lake, c. 1866. Photographer unknown / Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.14264.

This deployment of landscape as an elixir for the harried city dweller was, of course, decades premature for Brooklyn. The vast majority of Kings County in the 1860s was agricultural hinterland, and would remain so for years to come. It took no little vision to anticipate a day when Brooklyn would be thickly settled urban terrain. Of this Olmsted and Vaux had little doubt: Brooklyn would ultimately need Prospect Park to serve the same check-valve functions that Central Park did for New York. “We regard Brooklyn,” they wrote, “as an integral part of what to-day is the metropolis of the nation, and in the future will be the centre of exchanges for the world.” Until then, however, Brooklyn’s civic leaders needed their new park to perform an almost opposite set of duties. If Central Park tempered urbanism with a dose of the rural, Prospect Park was meant—initially at least—to introduce a note of urban spatial order and sophistication to an anarchic rural hinterland. It would help make Brooklyn more civilized, more urbane; more like Manhattan. Just like its New York equivalent, Prospect Park would cultivate “cheerful obedience to law” among the people, while advancing their “health, strength, comfort, morality, and future wealth.” But it would also prevent Brooklyn from “sinking into the character of a second-rate suburb of the greater city.” The great park would boost Brooklyn’s stock value, offering—in Stranahan’s words—“strong inducements to the affluent to remain in our city, who are now too often induced to change their residences by the seductive influences of the New York park.”23

Prospect Park is a masterpiece of landscape design that would never have happened without Calvert Vaux. But it was Olmsted who looked past the park to see it as the engine of something greater still. Vaux makes no mention of extending the park’s civilizing reach in his early plans or correspondence with Stranahan. Only after Olmsted returns from his California junket do we begin to see the park described in terms of planning the larger metropolis. Unlike Central Park, a capsule of rusticity locked in the city grid, Olmsted saw Prospect Park as the core of an open space system whose green tendrils would reach across Brooklyn and Queens and even back over the East River to Central Park—a “system of grounds . . . designed for the recreation of the whole people of the metropolis and their customers and guests from all parts of the world for centuries to come.” The idea was first sketched out in Olmsted and Vaux’s 1866 report to the Prospect Park commissioners. On the accompanying plan, they show a road stubbed out from the park’s southern entrance—the start of a “shaded pleasure drive,” picturesque in character and free of commercial “embarrassments.” Olmsted did not specify the route of this drive, except to say that its destination should “unquestionably be the ocean beach.” And that was not all. “It has occurred to us,” he added, that “a similar road may be demanded in the future which shall be carried through the rich country lying back of Brooklyn, until it can be turned . . . so as to approach the East River, and finally reach the shore at or near Ravenswood.” Olmsted is even more vague as to where this “grand municipal promenade” would start, except that it would branch off the first drive somewhere south of the park. The most logical place for this—which Olmsted almost certainly had in mind—is Kings Highway, the ancient Indian trading path that played such a crucial role in the Battle of Brooklyn. In any case, at Ravenswood—just east of Roosevelt Island in Long Island City—the drive could “be thrown” via bridge or ferry over the East River to hook up with “one of the broad streets leading directly into the Central Park.” The twenty-mile loop would allow a carriage to be “driven on the half of a summer’s day,” wrote Olmsted, “through the most interesting parts both of the cities of Brooklyn and New York [and] through their most attractive and characteristic suburbs.” The Eagle was more expansive, noting that Olmsted’s “grand highway of intercourse”—from Prospect Park to East New York and then “over a suspension bridge at Blackwell’s Island into Central Park”—would “unite in one common interest the two finest parks on the American continent.”24

Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, Design for Prospect Park in the City of Brooklyn, 1870. From William G. Bishop, Manual of the Common Council of the City of Brooklyn (1871).

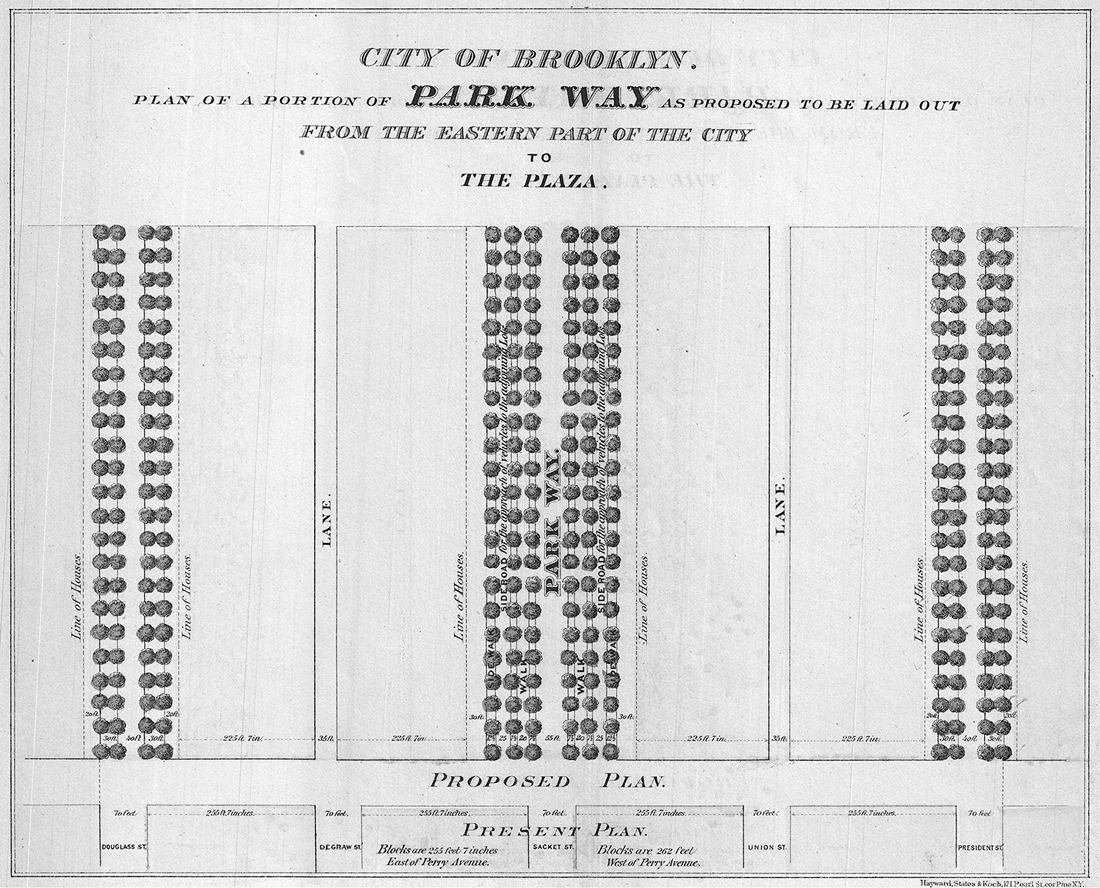

Over the next two years, Olmsted’s ideas on Prospect Park’s “suburban connections” evolved into no less than a treatise on the future of Brooklyn. This was presented to Stranahan and the commissioners in January 1868, and published two months later with a typically long-winded Victorian title—Observations on the Progress of Improvements in Street Plans . . . with Special Reference to The Park-Way Proposed to be Laid Out in Brooklyn. Prefaced by a fourteen-page discourse on the history of urban form, Olmsted’s exposition argued that Brooklyn could seize its future by planning for the vast population growth that would invariably come its way. Manhattan, waterbound and thus “in the condition of a walled town,” would soon run out of land to build on. “Brooklyn is New York outside the walls,” wrote Olmsted, where there was “ample room for an extension of the habitation part of the metropolis upon a plan fully adapted to the most intelligent requirements of modern town life.” The key to bringing this about was those shaded pleasure drives first discussed in 1866—what Olmsted now termed parkways. Extrusions of the park itself, the parkways would “extend its attractions” across new terrain while also serving as structural elements to guide street layout and residential development. The scenic thoroughfares—upon which “driving, riding, and walking can be conveniently pursued in association with pleasant people”—would create, like freshets in the desert, valuable real estate wherever they ran. “The further the process can be carried, the more will Brooklyn, as a whole, become desirable as a place of residence.”25

For all his inventive genius, the parkway was not sui generis Olmsted, but rather an idea he adapted from Continental precedents. Olmsted had been sent to Europe by the Board of Commissioners of Central Park in September 1859, and spent the next two months touring parks and public works in Liverpool, London, Paris, Brussels, and Dublin. Olmsted was most impressed by what he saw in Paris, where his host was Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand, the brilliant engineer who had helped Georges-Eugène Haussmann transform Paris under Napoleon III. Introduced to Alphand by a former Central Park commissioner who had retired to France, Olmsted spent ten days in Paris “examining as carefully as practicable . . . all its pleasure-grounds and promenades.” The visit “opened his eyes,” writes Elizabeth Macdonald, “to the prospect of landscape architects acting as city planners, and he brought this vision to Brooklyn.” Olmsted visited the Bois de Vincennes and the gardens of Versailles, and made no fewer than eight trips to the Bois de Boulogne. He also toured the Avenue de l’Impératrice (today’s Avenue Foch), which had opened five years earlier to connect the Bois de Boulogne to the Place de l’Étoile. The commodious avenue was 430 feet wide, with separated bridle paths, carriage drives, and walkways in the center, and bordered by hundred-foot landscaped strips and service roads on either side. This road, and Unter den Linden in Berlin—with its central carriageway and twin pedestrian malls—were examples of what Olmsted termed the “fourth stage of street arrangements.” They were both source and departure point for Olmsted’s next, presumably ultimate stage of street design—the parkway—to consist of a “central road-way, prepared with express reference to pleasure-riding and driving,” flanked on the inner sides by “ample public walks” and, beyond those, “ordinary paved, traffic road-ways” along which villas and homes would be built. The twin pedestrian malls would be planted with triple rows of “trees . . . of the most stately character.”26

Vue de l’Avenue du bois de Boulogne, c. 1854. State Library Victoria, Australia.

Olmsted envisioned three great parkways radiating outward from Prospect Park—one running east toward Queens before turning north to the East River at Ravenswood; one extending southwest to Bay Ridge and Fort Hamilton; and one running straight south to Coney Island. This infrastructure would not only make for long pleasure drives, but unlock Brooklyn’s urban future by irrigating a vast field for residential development of the choicest sort—a “continuous neighborhood . . . of a more than usually open, elegant, and healthy character.” This would give Brooklyn something its island-bound rival was unlikely to get anytime soon; for, as Olmsted pointed out, Andrew Green had already dismissed the idea of laying out “fanciful” avenues north of Central Park. The parkways would give Brooklyn “special advantages as a place of residence,” wrote Olmsted, “to that portion of our more wealthy and influential citizens, whose temperament, taste or education leads them to seek . . . a certain amount of rural satisfaction in connection with their city homes.” As the Eagle predicted, the parkway neighborhoods would “enjoy every advantage of city life . . . and yet be isolated from city traffic, surrounded by luxuriant foliage and enjoy all the pleasures and felicities of rural retirement. They will be in short, a perfect rus in urbe.” Olmsted’s parkway plan was the most ambitious open space system yet proposed for an American city, and “represented,” writes Elizabeth Macdonald, “a city-planning vision of a type and scale never before imagined.” Though based on a European model, the vast scale and reach of Olmsted’s parkways, their function as scaffolding for orderly urban growth—even the idea of joining scattered parks and open spaces into a single metropolitan system—were all unprecedented and “formed a wholly new urban design vision.”27

The plan gathered little dust. Legislative authority for constructing Olmsted’s parkways was secured within several years, and—despite legal challenges from affected landowners—construction on the first drive was well under way by the end of 1872. Variously called Sackett Street Boulevard, Jamaica Park Way, East Parkway, and ultimately Eastern Parkway—it was created by widening Sackett Street to 210 feet and running it over the rural countryside east of Prospect Park toward the Queens boundary. A first short segment opened in March 1874, from Grand Army Plaza to Washington Avenue, and by December the drive was complete to Ralph Avenue in Brownsville. That month, the commissioners announced the sale of hundreds of prime building lots—“elegant sites for private residences”—fronting the new drive. Then, after just two miles, Olmsted’s projected twenty-mile metropolitan loop petered out, for years ending abruptly “on the brow of a forbidding hill.” And while it was later extended—first to Stone Avenue (Mother Gaston Boulevard) and ultimately to Bushwick Avenue at the Cemetery of the Evergreens—the parkway east of Ralph Avenue hardly deserves the name. It was built simply as a wide urban thoroughfare, with few of the landscape amenities that so distinguished the Olmsted original. Ironically, truncated Eastern Parkway would be effectively extended a generation later as a new form of parkway—a motor parkway that would put Brooklyn within easy reach, not of Manhattan, but of the sandy pleasures of Long Island.28

Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, plan view of a portion of Eastern Parkway. From William G. Bishop, Manual of the Common Council of the City of Brooklyn (1868).

It was another giant of American urbanism, Daniel H. Burnham, who urged that Eastern Parkway be extended across the morainal backbone of Long Island all the way to Montauk Point. As we’ll see in chapter 10, Burnham visited New York as a guest of the Brooklyn Committee on City Plan in December 1911, just months before his death. “If you are going to inaugurate city planning in Brooklyn,” he said at the time to Eagle correspondent Frederick Boyd Stevenson, “you ought to include all Long Island from the East River to Montauk Point.” Burnham envisioned “fine streets and boulevards . . . running the entire length and breadth of your beautiful island.” As if to conjure Robert Moses, still years away from the start of his legendary career as New York’s master builder, Burnham advised that “one man should have all these plans in charge, so they would dovetail one into another and form a perfect, a continuous whole.” Burnham’s words fell not on dry sand. Within months, an All Long Island Planning Movement was launched, complete with a slogan—“All for One and One for All”—and chock-full of committees of “representative men” from Brooklyn, Queens, and a dozen Long Island towns. Though it was preoccupied with building a “Central Island Boulevard” from Brooklyn to the South Fork—a “splendid and continuous thoroughfare without a break”—the All Long Island Planning Movement remains the first step toward coordinated regional planning in metropolitan New York. An extension of Eastern Parkway through the Cemetery of the Evergreens—designed by Andrew Jackson Downing and Brooklyn’s second rural cemetery—was approved in 1908 by the state legislature, but there was no money for moving hundreds of bodies from the path of the road. In 1913, the Topographical Bureau of Queens presented a “Grand Central Boulevard” running from Brooklyn across Cypress Hills Cemetery and Forest Park to join William Vanderbilt’s Long Island Motor Parkway at the Nassau County line. It was designed with twin thirty-six-foot carriageways separated by a forty-two-foot median and configured in a series of curves “to fit the topography of the country.” Though World War I put an end to these plans, the idea of extending Eastern Parkway across Long Island was revived in the 1920s and eventually realized as the Interboro (Jackie Robinson), Grand Central, and Northern State parkways—all built by Burnham’s “one man,” Robert Moses.29

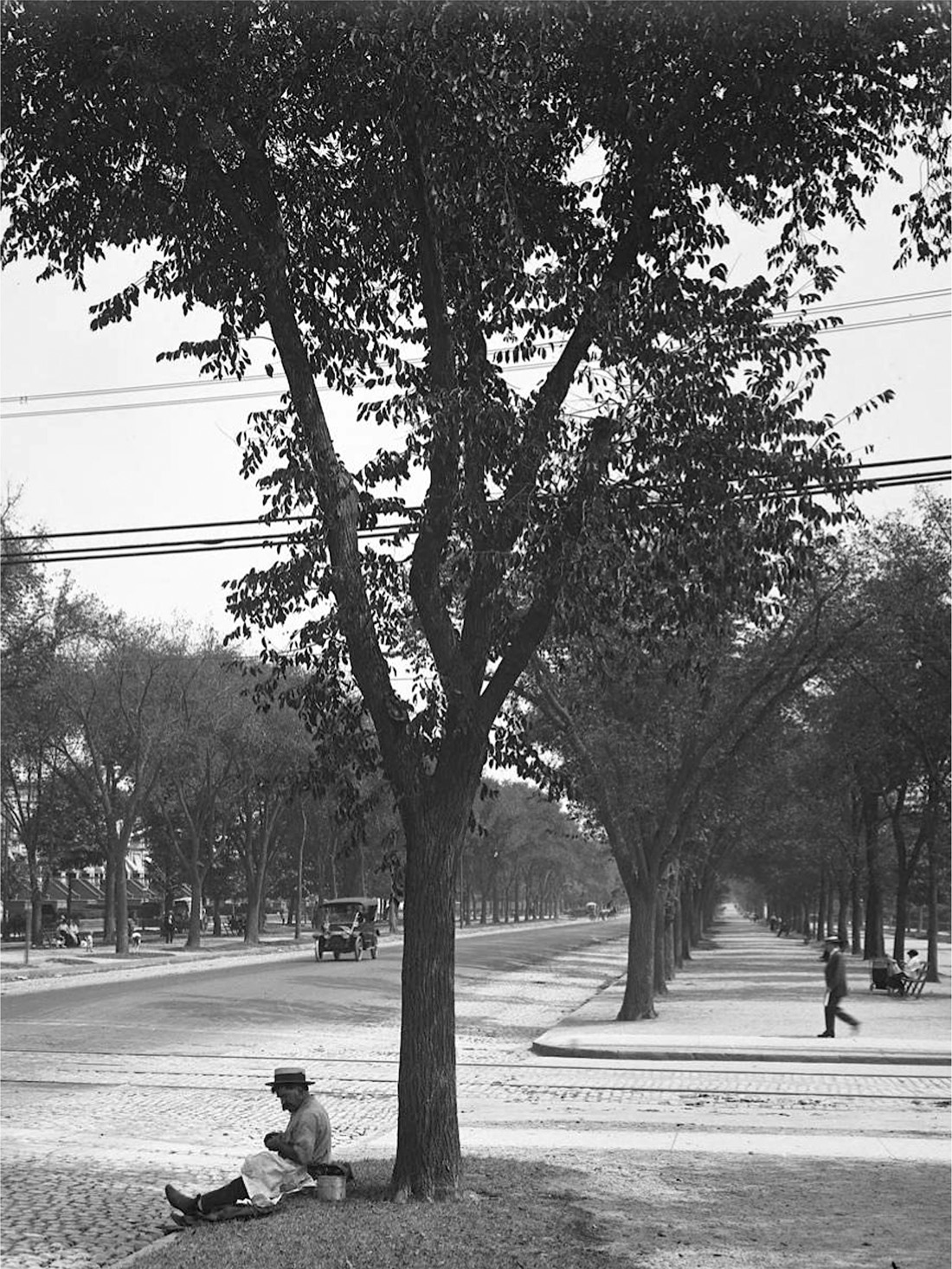

Yankee elms on Eastern Parkway at Nostrand Avenue, 1914. William D. Hassler Photograph Collection, New-York Historical Society.

“Gateway to America”: Eastern Parkway claims Long Island on behalf of Imperial Brooklyn. From Brooklyn Daily Eagle Development Series, April 26, 1912. The three trunk roads cartooned here foreshadowed the Northern State Parkway, Long Island Expressway, and Southern State Parkway. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

If Eastern Parkway barely made it to the Queens line, at least it was built. The parkway Olmsted projected from Prospect Park to the Narrows would never see the light of day—at least not in the magnificent form he had in mind. Fort Hamilton Parkway would begin from the southern entrance of the park, today’s Machate Circle, and run southwest through the town of New Utrecht. At Seventy-Eighth Street, the south end of Kathy Reilly Triangle today, a second drive would split off, running west along Bennett’s or Van Brunt’s Lane (Seventy-Ninth Street) to meet the bay at Van Brunt’s dock, near the present Seventy-Ninth Street playground on Shore Road. The main road would continue south for its namesake fort, where Olmsted advised that land be secured “for a small Marine Promenade . . . overlooking the Narrows and the Bay.” Joining the points was Shore Road, which ran south from the ferry pier at Bay Ridge Avenue around Fort Hamilton to the Dyker marshes. A bill to authorize construction of Fort Hamilton Parkway was introduced at Albany by Senator Henry C. Murphy on March 25, 1869. Though no immediate action was taken, by 1872 Franklin Avenue—which ran along the southern boundary of Prospect Park (Parkside Avenue today)—had been renamed Fort Hamilton Avenue and extended west as Olmsted had suggested. The new road became a parkway by executive fiat—and in name only—in August 1892. This was a wishful christening; for the “parkway,” a mere one hundred feet wide between building faces, was not even close to the expansive boulevard Olmsted had in mind, with a carriageway flanked by tree-lined malls and service roads. Now under the jurisdiction of the Parks Department, Fort Hamilton Parkway yet languished; in 1895 it was described as little more than a “mud slough through nearly its entire extent.” The following year, however, it was finally upgraded from the park to Sixtieth Street, and to Seventy-Ninth Street by late 1897. And though the Eagle now called it a “splendid boulevard,” it still hardly deserved the title parkway.30

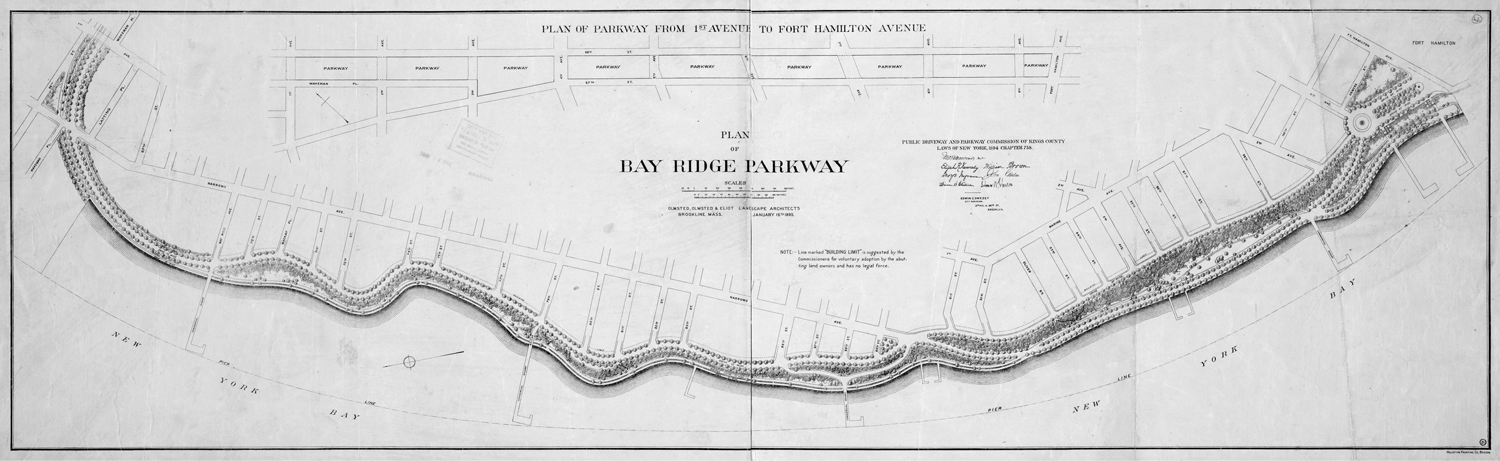

By this time, an exciting new possibility had arisen: to connect Fort Hamilton Parkway to the shore via not Seventy-Ninth Street but a new parkway running between Sixty-Sixth and Sixty-Seventh streets. This landscaped drive—initially called Bay Ridge Parkway (a confusing choice, as a thoroughfare of that name had already been approved to replace Seventy-Fifth Street)—would swing south around the bluff where Owl’s Head Park is today, improving the old shoreline route to Fort Hamilton and—foreshadowing the Belt Parkway by a generation—possibly on to Coney Island. Shore Road, dating back to the early eighteenth century, was a diamond in the rough—unpaved with steep grades and washed-out gullies, but affording splendid views of the harbor, Staten Island, and lower Manhattan. Given proper “artistic treatment,” opined the New-York Tribune, it might well become “one of the finest drives in the world,” a scenic perch looking out upon “a constantly changing sea-picture.” A parkway in place of Shore Road had first been advocated by James Stranahan, so it was only appropriate that the man tapped to create it was Stranahan’s old friend and colleague Frederick Law Olmsted. In June 1892 the aging landscape architect was engaged by the Public Driveway and Parkway Commission of Kings County, chaired by former Brooklyn park commissioner Elijah R. Kennedy. Olmsted visited the Bay Ridge site with his son, John Charles, in late December that year. He came to regard the Bay Ridge Parkway as one of the most important projects in the office. The final plan was delivered in January 1895, just months before Olmsted, his mental state deteriorating rapidly, was forced to retire from active practice. It was Olmsted’s last parkway, and among the very last projects he personally oversaw.31

Kennedy hoped the pleasure drive would be “a broad, splendid avenue down close to the water” like London’s Victoria Embankment on the Thames, or “such as Paris, Pisa, Florence, Rome, Naples and other cities have built down closer to their water sides.” Closer to home, he predicted that Bay Ridge Parkway “would easily surpass New York’s Riverside Drive.” Indeed, Olmsted’s drive was laced with planting beds, with a tree-lined carriageway, a sixteen-foot pedestrian mall, and a twenty-foot-wide bicycle path. Sweeping from high bluffs to the shore, it was “a waterside boulevard,” the New-York Tribune opined, “such as . . . no other city in the world can boast of.” Construction was well along by the end of 1897. Beyond the scope of Olmsted’s commission but essential to connecting Bay Ridge Parkway to Prospect Park was a nine-block run from Owl’s Head to Fort Hamilton Parkway. Title to the required land was in city hands by 1902, and by August the first section—from Fourth Avenue to Colonial Road—had opened. Set in a wide reservation, the drive wound downhill toward Olmsted’s road, passing under two “substantial and not wholly inartistic stone bridges” carrying Third Avenue and Ridge Boulevard overhead. Brooklyn’s great chain of parkways was nearly complete, and the Bay Ridge drive would be its pièce de résistance—“one of the most notable landscape features of Greater New York” and an attraction “worth a trip,” effused the Eagle, “across the continent to see.” But a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and for the Bay Ridge Parkway that link was a painfully short last extent of unbuilt road from Fourth Avenue to Fort Hamilton Parkway. By 1897 the commission was out of cash and canceled plans to cover these last few blocks. Enthusiasm for the project waned after Consolidation; then came the world war. The land sat idle for twenty years. By the 1920s, Bay Ridge was home to a large, politically engaged Norwegian community. Keen on securing its vote for the 1925 election, Mayor John F. Hylan directed the Parks Department to use the idled parkway corridor for a memorial to Norse explorer Leif Ericson and “the hardy race of Northmen who . . . fearlessly sailed the Atlantic.” Improved in the Moses era, Leif Ericson Park is today a centerpiece of Brooklyn’s fast-growing Chinese community. At its western end, the old Bay Ridge Parkway—Shore Road Drive—emerges from a lush green trough to melt back into the street grid.32

If Eastern Parkway was only partially realized according to Olmsted’s plan, and Fort Hamilton Parkway botched altogether—today “a major pedal-to-the-metal truck route,” as Forgotten New York’s Kevin Walsh calls it—Ocean Parkway was built almost precisely as the Connecticut Yankee envisioned it in 1868. The five-and-a-half-mile drive was constructed in two sections: from the park to the so-called Prospect Park Fair Grounds at Kings Highway, an early amusement ground and racetrack; and from Kings Highway to Coney Island. Work on the latter ended in 1876, and that November the parkway’s full five-mile length was opened to the public, “by whom it was quickly appreciated,” reported Stranahan and his commissioners, “and utilized as a delightful, convenient and substantial thoroughfare to the ocean.” Ocean Parkway made Brooklyn “the first American city,” wrote an admiring critic, “to establish a recreative route between the interior and the sea.” Running between the city and the great seaside playground of Coney Island, Ocean Parkway was popular from the start—almost too popular. The center roadway, seventy feet wide, was paved with twelve inches of fine gravel “from which all stones of large size were excluded,” its surface “carefully shaped and rolled until a proper bond was secured.” This smooth surface allowed for the fastest operation of carriages—Phaetons, Demi-Landaus, Rockaways—anywhere in New York. The traffic, which thronged the road on a fine summer weekend, moved according to unwritten rules, at least at first. There was no dividing line; drivers kept to the right, then as now, though the travel lanes expanded or contracted according to traffic volume—a vernacular, swarm-source form of zipper-lane or “barrier transfer” technology used on major commuter routes today. “In the mornings and early afternoons, when most carriages were heading toward Coney Island,” writes Macdonald, “the southward flow took up much of the roadway,” while in evenings, with the great throng heading home, “the northward flow predominated.” From the start, farmers and teamsters were also tempted to use Ocean Parkway’s fine carriageway, though most stayed on the side roads. Pleasure drivers were incensed by the heavy commercial vehicles, which rutted the pavement and vexed their good nostrils with the smell of cow shit and coal dust. Prohibiting such traffic from the central road—“business wagons of every kind, whether heavy or light, including trucks”—was first suggested in 1884 and made law by 1896. This practice was extended into the automobile age: the motor parkways of the 1920s and 1930s in Westchester and Long Island all similarly banned trucks and buses, and still do today.33

Plan of Bay Ridge Parkway, Olmsted, Olmsted and Elliot, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1895. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

Ocean Parkway also gave us the very first dedicated bicycle lane in America. By 1890, bicyclists—or “wheelmen,” as they were known at the time—had become so numerous on the parkway that the Brooklyn Park Commission required riders to register at the superintendent’s office at the Litchfield Villa and wear a conspicuous numbered badge on their left breast. Bicycling was an elite pastime, and the city’s many wheelmen clubs supported these codes not only to promote their sport as a respectable activity but to filter out the riffraff. “Requiring bicyclists to register,” writes Macdonald, “was an effective way of discouraging lower-class people . . . from riding on the parkways.” Then, in 1894, park commissioner Frank Squier consented to a petition from Brooklyn’s well-organized bicycling clubs to create a special bike lane along the parkway’s western mall. The Parks Department provided the labor to build the track, and the wheelmen raised the $3,500 needed to purchase the finely crushed bluestone for its surface. The Ocean Parkway bicycle path opened on a perfect summer day in June 1895, with a three-division parade organized by the Good Roads Association. The procession began at Eastern Parkway and Bedford Avenue, led by a military escort from the Thirteenth and Twenty-Third infantry regiments and followed by a bicycle division of the Brooklyn Police Department—the first bike-mounted police unit in the country. They wound around Grand Army Plaza and into Prospect Park before heading down Ocean Parkway for Coney Island. Some ten thousand “wheelmen and women” rode past the reviewing stand at Newkirk Avenue, representing fifty-eight bicycle clubs and unions—from the Whirling Dervishes to the Harlem Wheelmen (with their “very jaunty air”). Carriages, horses, and even pedestrians were prohibited from the new path. Bicyclists were forbidden to coast, had to keep below twelve miles per hour—“scorchers” would be arrested—and had to “keep their feet upon the pedals . . . at all times.” The bike path was too popular. The more fanatical wheelmen—forebears of the Lycra-clad jackasses who slap tourists on the Brooklyn Bridge today—complained of women and children clogging the path, which turned into a “mudway” after the smallest thunderstorm. They demanded that the rule banning wheelmen from the main carriageway—“a very ungraceful attempt to discriminate”—be rescinded. Instead, a second bike path—on the east side of Ocean Parkway—was opened the following summer to even greater fanfare. The New York Times estimated the spectators at more than 100,000—“stretching along the entire length of the boulevard . . . a fat line of enthusiastic people, five deep on either side.”34

The next time you find yourself traffic bound in an Uber on Ocean or Eastern parkways, recall that these arterials were conceived not just as transportation infrastructure, but as instruments of urban order projected across the countryside. Essential to their civilizing mission was to inject into the “chaos” of rustic space a perfected, idealized symbol of American nature. As we’ve seen, the regimented rows of forest trees that lined Olmsted’s parkways were not merely ornamental but a vaccination against the presumed enervating effects of the impending metropolis—the great wave of urban development that, by 1930, had swamped Brooklyn’s last working farms in a flood tide of brick and mortar. To both ruralize the cities and urbanize the country was, paradoxical as it seems, the double lodestar of Olm-sted’s long career—“the supreme desiderata,” as Putnam’s Monthly put it, “of a higher civilization.” Olmsted’s Brooklyn parkways, planted six trees across, were veritable forest corridors. Some eight thousand trees were set out on Ocean and Eastern parkways by 1880, almost certainly the single largest coordinated street tree-planting campaign in nineteenth-century America. They included a robust mix of native and introduced species, even occasional “exotics” like weeping willow, which was used on Ocean Parkway near the sea owing to its reputed tolerance for salt. But far and away the most numerous species was the American elm. Requests for proposals made in the fall of 1872 for Eastern Parkway called for 550 sugar maples (Acer saccharum); 550 box elder trees (Acer negundo); 245 Norway maples (Acer platanoides); 245 European elms (Ulmus campestris); 232 European lindens (Tilia x europaea); 192 tulip trees (Liriodendron tulipifera); and nearly 2,500 American elms—significantly more, in other words, than all the other species combined. Olmsted appears to have used the maples and lindens for the outermost row of trees, along the service lanes. For the main carriageway and malls he used only American elms, as nearly every old photograph clearly shows. Thus did this Connecticut Yankee, child of a land of elms, give Brooklyn the mightiest Elm Street of all.35

Opening day parade, Coney Island cycle path, Ocean Parkway, 1896. Edgar S. Thomson photograph collection, Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.