CHAPTER 10

THE MINISTRY OF

IMPROVEMENT

And I saw the holy city . . . coming down from God out of Heaven.

—REVELATION 21:2

Not all who gazed into Brooklyn’s crystal ball saw either steel-ribbed globes or a future of seaports and industry. Some hoped instead that it would remain a quiet retreat from the fevered rush of Mammon, a leafy bedroom city with a skyline spiked by steeples and spires—so many that Brooklyn was long known as the City of Churches. It was in one of these good houses in 1899 that a youthful Chicagoan named Newell Dwight Hillis stepped up to the most famous pulpit in America. The church was the Plymouth on Orange Street in Brooklyn Heights, and like its namesake it was the rock upon which Brooklyn’s progressive elite built their house. Plymouth Church had become legendary a generation earlier for its mighty—and mightily flawed—founding pastor, the “Great Divine” Henry Ward Beecher. Though eventually brought down by a sex scandal—the biggest in nineteenth-century America (earning him more headlines than the Civil War)—Beecher at his height was among the most celebrated public figures in the world. So many pilgrims came to hear his thunderous oratory that Sunday ferries from Manhattan were known as “Beecher Boats.”

Despite his Calvinist roots, Beecher was a fire-breathing abolitionist who practiced what he preached, turning Plymouth Church into the “Grand Central Depot” of the Underground Railroad by hiding fugitive slaves in its tunneled cellar. He also staged one of the great publicity stunts of the abolition era—mock auctions in which congregants could purchase the freedom of an actual slave. The most famous of these involved Sally Maria “Pinky” Diggs, an enslaved nine-year-old girl from Washington described as “nearly white” by the Brooklyn Eagle, “having only one sixteenth of negro blood” (sale of this “interesting chattel,” the paper reported, brought $900).1 Beecher shared his pulpit with many luminaries of the day—Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and Mark Twain (whose best-selling Innocents Abroad satirized an 1867 grand tour by a group of Plymouth congregants). It was as Beecher’s guest at Cooper Union on February 27, 1860, that Abraham Lincoln delivered the speech—a powerful denunciation of slavery and secession—that gained him the Republican nomination and eventually the presidency. Plymouth would remain the only church in New York City that Lincoln ever attended. Beecher still lords over the Orange Street courtyard of Plymouth Church, in a bronze likeness by Gutzon Borglum, sculptor of Mount Rushmore.

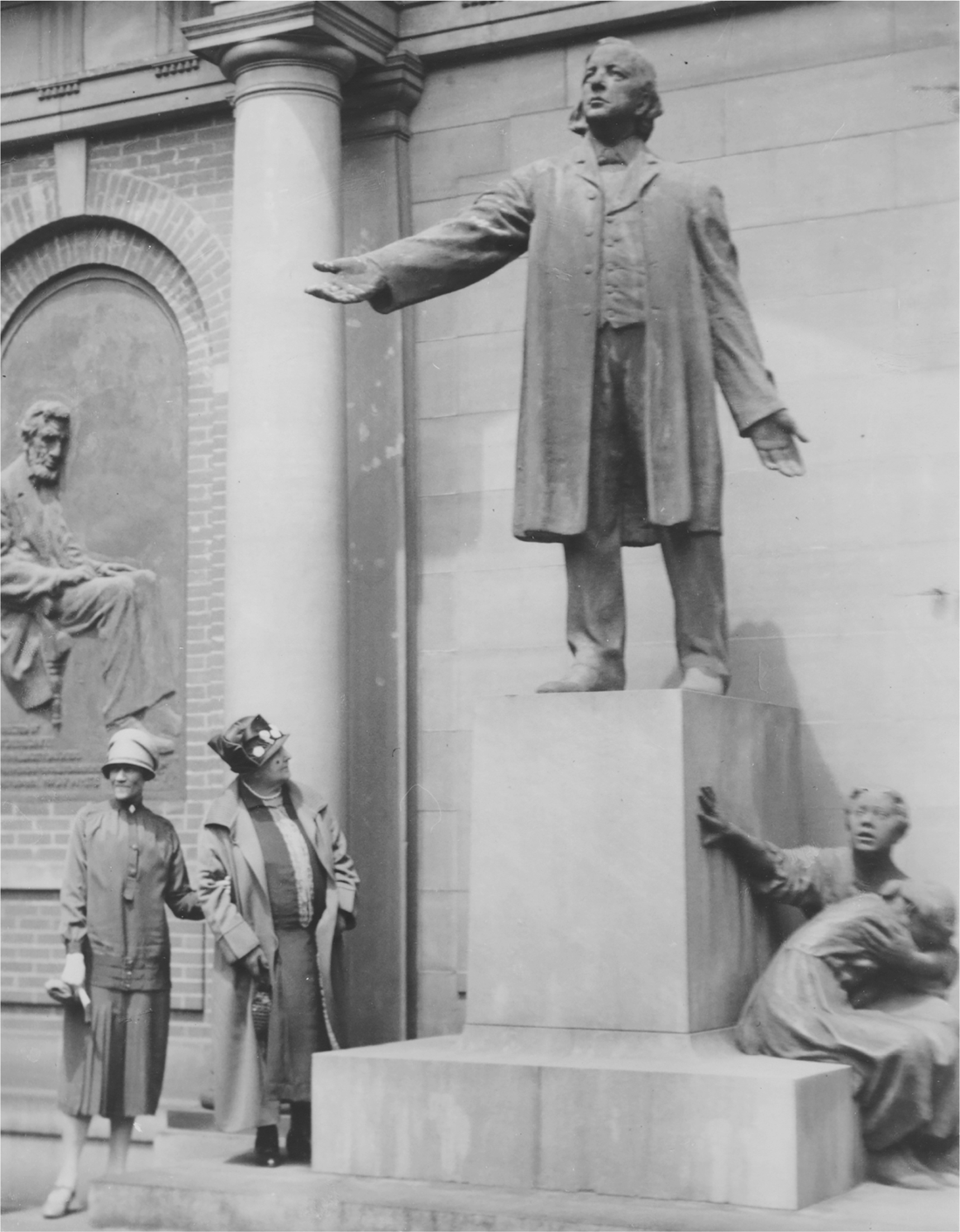

Hattie Clarke Smith (left) and Rose Ward Hunt at the Henry Ward Beecher monument, Plymouth Church, 1927. Hunt, formerly Sally Maria “Pinky” Diggs, was the enslaved child whom Beecher “sold” to freedom in a mock auction at the church in February 1860. Smith was in the congregation that day with her father, and the two girls became fast friends. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

The Reverend Newell Dwight Hillis thus had outsized shoes to fill upon becoming Plymouth’s pastor in the winter of 1899. But he quickly filled them, proving himself a worthy heir to both Beecher and his scholarly and controversial immediate successor, Lyman Abbott. It might seem odd that an institution with such Yankee roots—Beecher and Abbott were both New Englanders, as was most of the original congregation—would choose the son of a small Midwestern town to shepherd its flock. Hillis was born in Magnolia, Iowa, in 1858 and raised on a Nebraska farm; he spent summers preaching to miners in Wyoming and studied theology at Chicago’s McCormick Theological Seminary. But Hillis had a pedigree that made him attractive to the Plymouth elect. He was of Puritan stock—“American from core to cuticle”—and the son of the deacon of the Litchfield, Connecticut, church headed by Henry’s father, Lyman Beecher, firebrand of the Second Great Awakening (whose granddaughter, Emily Baldwin Perkins, was briefly engaged to Frederick Law Olmsted). Moreover, Hillis was a gifted orator in his own right. His sermons drew ever larger crowds at each of his early church posts—Peoria, Evanston, Chicago. Tall, thatched with a lordly mane of silver hair, Hillis filled the Plymouth tabernacle with a presence that rivaled that of his revered predecessor. One admirer called him “the most irresistible creature that ever lived.” Hillis had a keen intellect, a mind “quicker than chain lightning,” and a personality both charming and magnetic—reaching toward men “as the charged steel toward scattered needles.” He was already a well-published author; his command of theology, history, and the classics made his sermons as erudite as they were spiritual. One of his most ardent devotees, Theodore Roosevelt, called Hillis “the greatest forensic orator in America.”2

He was not, however, Beecher reheated. Beecher stirred the passions; Hillis appealed to the intellect. The former’s oratory was “a mighty battle of the elements,” after which came a “glorious calm and the still, small voice of God.” Hillis’s voice, on the other hand, “never booms,” wrote Peter MacFarlane in a 1912 Collier’s profile. It crackled instead like electricity, setting off sparks and moving “swiftly on, lighting the gloom, kindling the intelligence.” If Beecher delivered a punch to the “solar plexus of the soul,” Hillis “put a steam-hot towel on the face of conscience,” gently opening the pores of “man’s moral nature.” But Hillis was also a man of action. Within a year of assuming the Plymouth pastorate he picked an Oedipal fight with the Presbyterian clerisy that had trained him. At issue was a core tenet of Calvinism—the doctrine of predestination, specifically a grim passage in the Westminster Confession of Faith holding that while “some men and angels are predestinated unto everlasting life,” others are “foreordained to everlasting death.” Hillis took exception, declaring, “I would rather shake my fist in the face of the Eternal” than accept the “frightful view” of a cruel and vindictive God. This so outraged his elders at McCormick Seminary that they threatened to try him for heresy. But his Brooklyn Congregational flock backed him fully—one suspects with glee that their brave David had taken on the corn-fed Philistines. Hillis refused to back down. Instead, he resigned from the Chicago Presbytery and demitted himself from the Presbyterian Church—roughly equivalent to giving up tenure. It is no surprise that Hillis would find the notion of “infant damnation,” as predestination was often called, so repulsive; he was a reformer at heart, a crusader with steadfast faith in man’s capacity to improve—not just his body and soul, but his earthly home. Hillis yearned to make straight the crooked path, to better the city around him, to make Brooklyn a place of beauty, grace, and order.3

His first Goliath was Tammany Hall. The fabled political machine had resurrected itself from Boss Tweed infamy in 1897, when Tammany stalwart Robert A. Van Wyck ran against Seth Low for the mayor’s office. Van Wyck gave not a single campaign speech but won nonetheless to become the first mayor of consolidated Greater New York. His administration was a circus of corruption and incompetence, though it did succeed in awarding the city’s first subway contract. Routinely denounced as a dictator, Van Wyck presided over “probably more administrative scandals,” pronounced the New York Times, “than any Mayor in the city’s history.” The Tammany revival stirred reformers to take back City Hall in the fall of 1901, a political cataract into which Hillis jumped a week before the election. His Sunday sermon on October 27 blasted Tammany for making New York “a blot on the world map,” dragging the great metropolis into the gutter and leaving “a stench in the nostrils of the other great cities of the world.” For Hillis the election was not about jobs or the economy; it was a struggle between darkness and light. What the people needed was moral leadership. Would a future citizen lifted above the city “behold the webwork of government,” he asked, “bright with the glow of manhood and integrity?” Or would that airborne judge see instead “a veritable devil’s web in which all the threads run out as so many channels along which iniquity can thrill and throb?”4

Hillis avowed that there could be no fellowship with Tammany Hall. “Reconciliation of iniquity with virtue,” he lectured, “does not ask for the methods of a lawyer; it asks for the methods of a soldier.” This was a swipe at Edward Morse Shepard, the respected Brooklyn attorney and reformer who had accepted the Tammany nomination hoping to reform the Democratic Party from within. Many felt, like Hillis, that the dapper blueblood was naive and would be eaten alive by the Tammany tiger (a Harper’s Weekly cartoon—“A Marriage of Convenience”—showed Shepard at the altar with a veiled tiger bride). Hillis chose his words carefully—Shepard was powerful and a Brooklyn Heights neighbor—but pulled no punches. “If the water in the well is full of typhoid germs,” he asked, “can you purify it by putting in a pump painted in soft and esthetic [sic] colors?” Comparing Tammany boss Richard Croker to Beelzebub (“with apologies to Beelzebub”), Hillis concluded that an election victory for Shepard would enthrone “a vicious band of men who have . . . made it impossible for the great lawyer to reform them.” Alas, there could be no conciliation here, for “vice and virtue cannot be compromised.” Shepard’s main rival was fusion candidate Seth Low, then president of Columbia University and a former two-term mayor of Brooklyn. At a Broadway campaign rally for Low, Mark Twain compared Shepard to the edible end of an otherwise rotten banana. The race was close, but enough New Yorkers concurred with Twain to hand Shepard a five-point defeat.5

Hillis also extended Henry Ward Beecher’s legacy of racial justice into the new century, moved to speak out by comments on the “race problem” by his immediate predecessor at Plymouth, Lyman Abbott. At the time, Abbott was editing the Outlook—a popular national news and opinion weekly—and had been lecturing around the country on how blacks and whites “might live together amicably . . . in a community permeated by the democratic spirit.” The union he envisioned, however, was hardly an equal one. At a 1901 banquet of the Get-Together Club, Abbott sympathized with the South and commended “the work it has undertaken for the negro.” He reminded his audience that if Southern attitudes seemed harsh, Northerners would likely act the same way or worse if the shoes were switched. “Let us get away from the thought that all men have an equal right to vote, to a place in society,” he counseled; for it was “a mistaken impression” to regard “the black man as good as the white man.” Abbott ended on a “hopeful” note: “We haven’t been able to turn the mongrel into the full-blooded collie in a century,” he said, “but let us have patience.”6

Abbott later spoke at a 1903 benefit for Tuskegee Institute at Madison Square Garden, sharing the platform with Booker T. Washington, Seth Low, and the presidents of Columbia and New York universities. In the audience were some of the wealthiest men in America, including Jacob H. Schiff and Andrew Carnegie, who made a large gift to Tuskegee afterward. The keynote speaker was former president Grover Cleveland, who delivered a tough-love soliloquy on “the vexatious negro problem at the South” prefaced by the requisite claim that he was “a sincere friend” of the black race. Cleveland lamented the “racial and slavery-bred imperfections and deficiencies” of African Americans, which neither freedom nor the rights of citizenship “any more purged them of” than it “changed the color of their skin.” White Southerners were forced to “stagger under the weight of the white man’s burden,” he claimed, before echoing Washington’s Atlanta Compromise—arguing that blacks “who fit themselves for useful occupations and service” would find “willing and cheerful patronage . . . among their white neighbors” (for it was “at the bottom of life we must begin and not at the top”). Abbott followed Cleveland on the stage, likewise counseling against putting the cart of suffrage before the horse of culture and improvement. “We have tried the experiment of giving to the negro suffrage first and education afterward,” he related, “and bitterly had the country suffered from our blunder.” The implication was that the right to vote, despite the Fifteenth Amendment, should be withdrawn until some charmed stage of cultural attainment was reached.7

In a blistering sermon several weeks later, Hillis reproached Abbott and Cleveland for having “closed the door of hope in the negro’s face,” arguing that “our fathers founded the Republic upon liberty and equality.” Of course, Hillis omitted the inconvenient fact that many of those fathers were slaveholders, and that African Americans were not even legal citizens of the United States after the 1857 Dred Scott decision. He submitted that if ignorance or illiteracy were to cost blacks suffrage, then plenty of white Americans—“the foreign races—Italian, Bohemian, Pole, and Greek”—should also lose the right to vote. Hillis hoped that in their struggle for freedom, Booker T. Washington and other black leaders would not guide themselves by such fickle lodestars as Abbott or Cleveland, whom he likened to “tin weathercocks on the neighboring barns.” In the end, the problem of the South was an industrial and economic one, Hillis stressed, “not a political problem to be settled by a political method.” Around this time, a chambermaid at an Indianapolis hotel refused to tend to Washington’s room, claiming no white woman should have to clean up after a black man. She was summarily fired but received an outpouring of donations, job offers, and even marriage proposals from across the South. The episode made national headlines, to which Hillis added by declaring that if Washington were to visit Brooklyn Heights, he would gladly make up his bed.8

But the Plymouth pastor’s greatest passion was more grounded, literally, than politics or even matters of the soul. He developed a keen public interest in city planning, joining a raging transit debate in March 1902 with an eager homespun proposal to solve the problem of traffic congestion on the Brooklyn Bridge—a great hoop tunnel linking downtown Brooklyn and lower Manhattan like a wedding band. His “little underground circular railroad” would run trains in both directions and tap the main streetcar and elevated lines of both boroughs. Clockwise from City Hall, the tunnel would pass under the Lower East Side and the East River to the industrial quarter known as Dumbo today, arc southwest toward Borough Hall and downtown Brooklyn, cross Atlantic Avenue near Clinton Street and on to Red Hook. At the foot of Hamilton Avenue it would turn back north to cross the harbor just east of Governors Island, reaching Manhattan at the Battery—precisely the alignment, ironically, that Robert Moses would use decades later for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Explaining to a Brooklyn Eagle reporter that he knew nothing about tunnel work and might well be joining “that company of fools who rush in where engineers fear to tread,” Hillis nonetheless plunged into an elaborate exegesis of his scheme, pointing up its elegant simplicity and explaining how it “diffuses and distributes constantly, and makes congestion impossible.”9

Congestion to Hillis was a sin on the urban soul; it stirred his priestly passions and even led to poetry. On a Sunday afternoon in May 1903 the minister’s trolley got stuck in a major jam on the Brooklyn Bridge, causing him to miss a train to a Connecticut speaking engagement. After raging at the empty platform, he sat down and composed a mordant piece of doggerel—“To Hades on a Brooklyn Car.” The New York Herald praised it and printed it in full. The Evening Telegram was less impressed, describing the minister’s lines as “a bit off their feet, as if they had been clinging to a strap” and noting that, in any case, Brooklynites needed no trolleys to get to hell—they’d go a faster way. Hillis was also among the many prominent Brooklyn men who spoke out in favor of city bridge commissioner James W. Stevenson’s proposal to eliminate the “bridge crush” in Brooklyn by building an elevated loop across the Lower East Side connecting the Manhattan ends of the Brooklyn and Williamsburg bridges. The plan was controversial from the start, pitching long-suffering Lower East Siders against a well-organized array of Brooklyn civic organizations and business interests backed by the Brooklyn Eagle’s partisan editorial board. “Loop agitation” reached a fever pitch in 1906, with broadsides flying back and forth across the river. As the New York Times weighed it, each side claimed “humanitarian motives, and accused the other of shortsightedness, bad judgment, unpracticality, sectionalism, and other unneighborly qualities.” Charles Bunstein Stover, then head of the East Side Civic Club, called the proposal “a brazen and amazing attack on the east side by the people of Brooklyn” that would plunge the Bowery into noise and darkness. Meant to be a temporary fix until the Manhattan Bridge opened, the scheme was voted down by the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners in favor of the now-defunct Centre Street Loop Subway. But Brooklyn clamored still for the el, well aware it would be years before the new subway and bridge were completed. At a commission hearing in January 1907 a rambunctious crowd of three hundred Brooklynites—chanting “Loop! Loop! Loop!”—were nearly ejected for their hoots and catcalls. Two weeks later, Hillis and a Brooklyn lawyer with a burgeoning interest in city planning—Edward Murray Bassett—led a rally on Fulton Street to denounce the heartless Rapid Transit Commission. Hillis likened Brooklyn’s patience to that of Job, remarking that if he were a cartoonist, he’d draw the borough “as a man trying to swim the East River with a millstone tied about his neck.” That spring, the tide seemed to turn briefly when the Dowling Elevated Loop Bill passed the senate before being killed in the assembly, thus putting the whole weary matter finally to rest.10

For Hillis, however, this was just the start. In April 1908 the minister spoke at the opening of the Congestion of Population exhibit at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. The brainchild of social reformer Benjamin C. Marsh, the exhibit called attention to the evils—real and imagined—of rapid population growth. At the time, American cities were expanding at an unprecedented pace. Between 1860 and 1910, the urban population of the United States increased sevenfold, with some nine million immigrants arriving from abroad in the first decade of the twentieth century alone. Hillis focused on humanitarian matters, emphasizing the great need for playgrounds and warning that congestion in New York had caused such a surge in the death rate that it would soon match that of the recent San Francisco earthquake and fire. By May, city-planning fever was in the air. That month, Marsh and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., held the landmark First National Conference on City Planning in Washington—an event Hillis almost certainly attended. The same weekend the Brooklyn Eagle ran a front-page story on a proposed “Grand Gateway to Brooklyn,” featuring a great circular “Bridge Plaza” on Flatbush Avenue at about Tillary Street—the imagined junction of the extended Brooklyn and Manhattan bridge alignments. It was meant to give Brooklyn a formal entrance, alleviate the old “bridge crush” problem, and create a symbolic link to Manhattan by opening up views straight up both bridges—consolidation of a visual sort. Designed by Whitney Warren, a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts who later designed Grand Central Terminal, the scheme was first proposed by the New York City Improvement Commission in its 1907 Report to Mayor George B. McClellan. From the extravagant colonnaded space—a Parisian sampler for a gritty town—thoroughfares would radiate traffic across the borough like spokes in a great baroque cartwheel. Flatbush Avenue was extended to the Manhattan Bridge, while new thoroughfares would lead north to the Brooklyn Bridge and east and west to the New York Naval Shipyard and Borough Hall. The Eagle praised the commission proposal and “the moral effect of such public works on a community. They excite public pride and an increase of public spirit follows as a consequence.” It was a theme Hillis would take up powerfully now from his pulpit.11

That following Sunday, Hillis delivered possibly the most eloquent paean to the city ever to shake the rafters of an American church. The first of several sermons he would deliver on the subject, Hillis’s oration began with a haunting passage from the book of Revelation—“And I saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of Heaven.” Hillis interpreted the text not as idle prophecy but as a mandate for the urban present. The pastoral time of Genesis was over; upon us now was an urban age, a time “when the very word of civilization means the manner of life of men who dwell in cities.” The countryside may feed us, but it is the city that draws the generation’s brightest souls, tugging at “the heartstrings of a gifted youth as an oasis draws the birds of paradise in from the Sahara with its stifling dust and heat.” To Hillis, the metropolis was the great storehouse “into which all the sons of genius bring their treasure.” It was the foundry where laws are forged and justice bestowed, the “granary for all the sheaves of intellect, the museum that holds the achievements of artists, investors and travelers . . . the home of music, art and eloquence.” And as goes the city, the minister avowed, so goes civilization. “Linger long in the streets of the great capital . . . and there you will find the seeds that will ripen harvests of prosperity, or days of disaster and retribution. What is the future of France? Read that open page named Paris . . . Madrid is making Spain. St. Petersburg is shaping Siberia. As goes New York, so will go the republic.”12

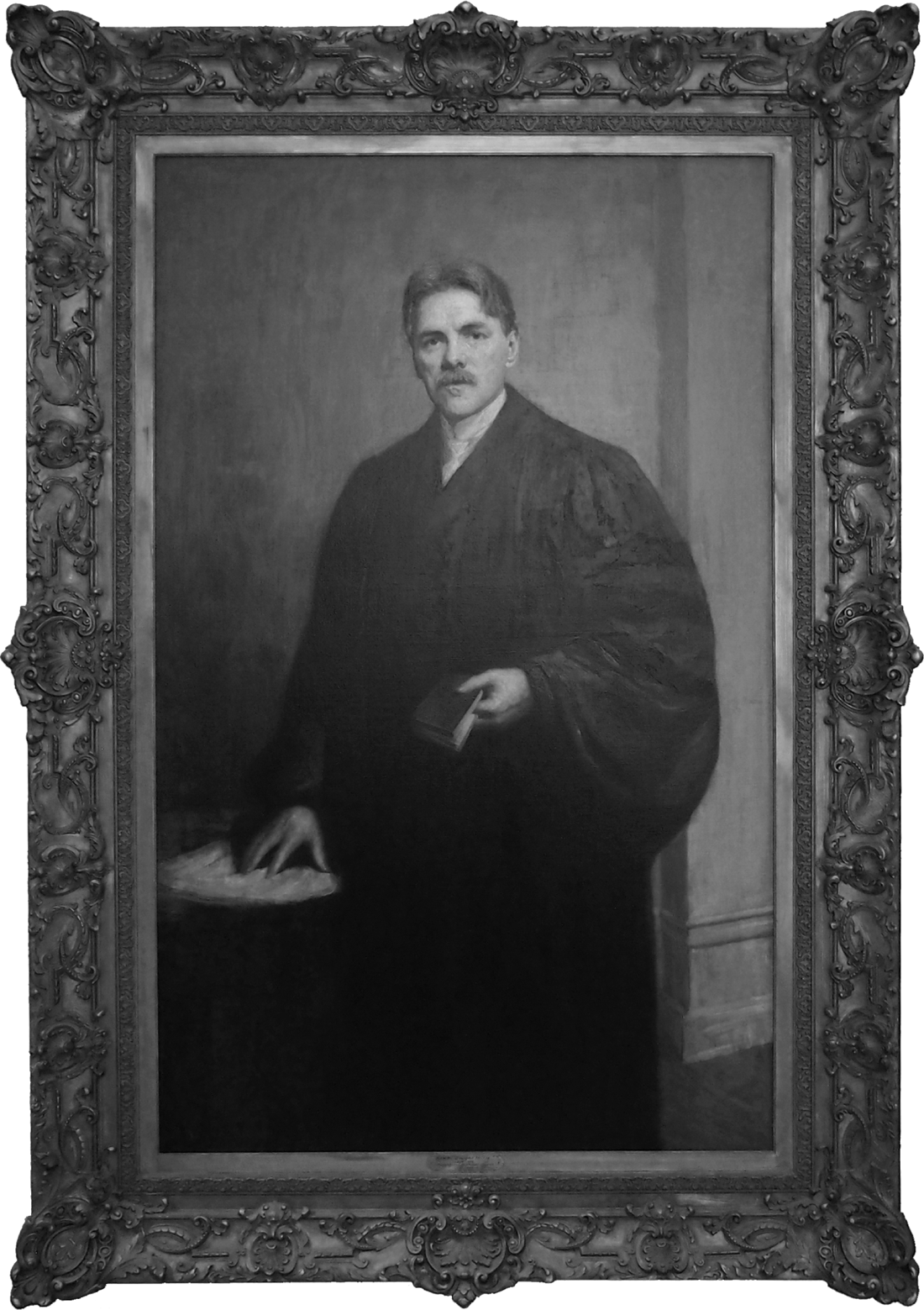

Portrait of Newell Dwight Hillis at Plymouth Church, c. 1910. Photograph by author.

Hillis soared on the subject of Gotham, which he considered the heart, mind, and soul of America. “Cherishing for our beloved city all the enthusiasm that Dr. Johnson and Charles Lamb cherished for London,” he pressed, “let us strengthen our confidence that free institutions will finally burst into their finest flower and fruit in this great metropolis, that will ultimately become the city of beauty, the city of art, architecture and learning, and perhaps, under God, the greatest as well as the most influential city in the world.” In a sermon that September—“Life in the Great City”—he described New York as the polestar metropolis of the West. “All the steamships from all the world converge toward this harbor; all the trains . . . run like spokes toward this central spot.” Writers might extoll the splendors of world’s fairs or expositions; but New York “is a perpetual world’s fair, assembling treasures that never could be brought together in an exposition in Paris or Chicago or St. Louis.” He also recognized, at a time when nativist sentiment was rising throughout America, that the wellspring of Gotham’s genius and vitality was immigration. To the great city came the self-gleaned best and brightest, from both countryside and abroad—women and men who, “like Saul, stood head and shoulders above their fellows in the old home town.” The singular truth that immigrants “dared transplanting and think themselves equal to the keen rivalries of the city,” argued Hillis, “is in itself an unconscious revelation of their power.” New York must always welcome these daughters and sons of ambition; “We need their strength; they have power to found and genius to adorn an empire. We need their enthusiasm; they will freshen our jaded hearts and inspire our worn lives.” And all this was symbiotic; for the immigrant, too, “needs the city’s wisdom, needs the city’s gold, the city’s commerce, the city’s art, the city’s religion.”13

Gotham was hardly beyond reproach, of course; for just as genius thrives in a great metropolis, so do stupidity, vice, and evil—drawn to its streets as surely as a granary draws vermin. Not for nothing, Hillis reminded his congregants, did Genesis make the first city—Enoch, in the Land of Nod—the domain of fratricidal Cain. It is in the city, Hillis related, “that sin puts on enticing garments, appearing as an angel of light,” that mansions are built by greed, whose avenues are “lined with houses that represent avarice and cruel selfishness.” Poverty in the city was both a moral and a physical hazard. Hillis reminded his well-heeled listeners that Brooklyn’s poorest, most congested district—the old Fifth Ward—lay but a stone’s throw from Plymouth Church. He imagined a time when leading citizens would no longer abide such privation in their midst. A rising generation, he predicted, would make a better, more beautiful city. It would condemn sundry private yards and make instead a “common flower garden,” transform the empty lots of downtown Brooklyn “into little bowers of beauty”—perhaps even create a grand gateway to the borough at the Brooklyn Bridge. And he looked to a day “when some great architect and artist . . . will plow an avenue 600 feet wide, with a great open esplanade looking upon Wall street, straight to yonder flower-crowned height, Prospect Park, and make it as broad and beautiful as . . . the Champs Elysees.” For all its swagger, this was hardly idle rhetoric; Hillis meant to take his message to the streets.14

In February 1910 Hillis rallied a large gathering of Heights residents to demand better transit service and a station on a projected subway route that was to pass directly beneath Brooklyn Heights—an extension of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company’s West Side line. Comparing the Heights to “a baby with a hemp rope about its neck . . . slowly being strangled to death,” he asserted that the community was ignored by City Hall because it had been too mannerly and gracious; now it was time to “get up and do some shouting.” They voted to found an advocacy group—the Brooklyn Heights Association—and elected Hillis one of its officers. Soon enough the association wrangled a promise from the city that the Heights would get a subway station all its own—the Clark Street IRT stop below the Hotel St. George, opened in April 1919 and still the deepest station in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Heights Association would go on to become one of New York’s most fabled civic organizations, credited with defeating plans to route the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway through the community in the 1950s and establishing the city’s first historic district in 1965. But the minister’s vision of improvement ranged well beyond his own neighborhood. In April 1911 Hillis spoke on “The Brooklyn of the Future” at an annual gathering of the Brooklyn League, an event that brought together many of the borough’s leading men. Citing trends as alarming as they were inaccurate, Hillis made a number of extraordinary predictions—among others, that the population of Manhattan would reach 12 million by the 1970s, and that of the United States a staggering 800 million. Brooklyn, too, would rank among the world’s largest cities by then—at some 10 million residents. Geography, Hillis claimed, made all this possible; for in Brooklyn, “the great ocean takes the tides out twice each day, carrying all filth with it, and pours back the pure, life-giving flood.” But getting through the straits of rapid growth called for thorough preparation. “What we need at once,” Hillis counseled, “is a great working plan for a city of 10,000,000 people.” He imagined a commission of leading men to guide the work, with citizens rallied to the cause by drawings “put on slides and carried through the stereopticon into every ward.”15

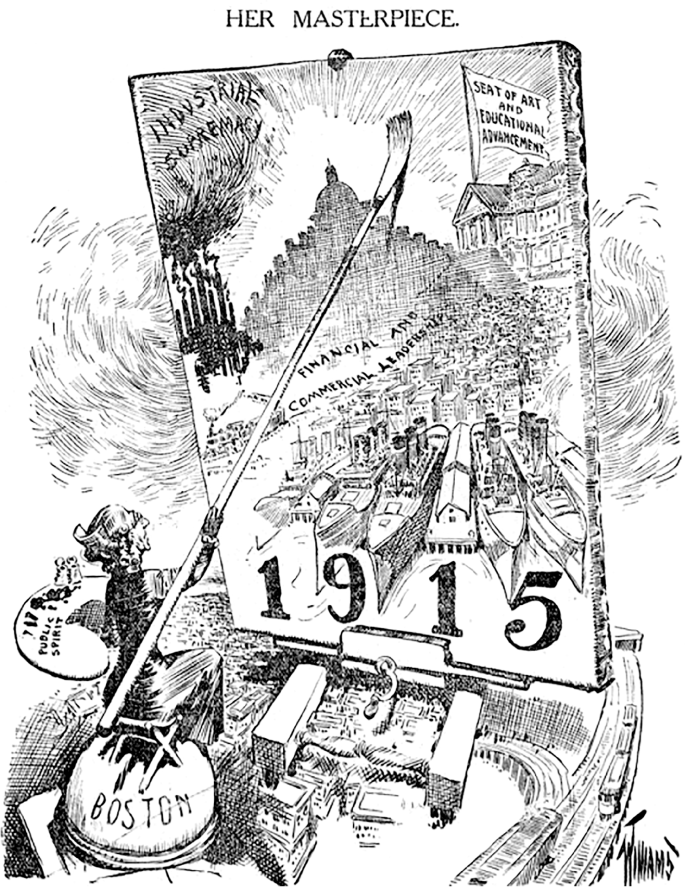

Editorial cartoon on the Boston 1915 Movement. From Boston Sunday Herald, April 4, 1909.

That summer, Hillis set off across the Atlantic with his family to visit the Holy Land. During a brief stay in Paris he met a delegation of some eighty men and women from Boston. They were part of an ambitious campaign spearheaded by future Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, retail magnate Edward A. Filene, and banker James J. Storrow. The “Boston 1915” movement, as it became known, was inspired by the 1909 Chicago “City Beautiful” plan and sought to establish a metropolitan planning commission for the Boston area. The group was in Paris on a study tour of European cities in advance of two major conferences in Boston the next year—on city planning in April and global trade and commerce in September. The enthusiasm of the Bostonians—especially delegation leader John H. Fahey, whom Hillis later invited to Brooklyn—was infectious; for the minister soon canceled his Holy Land tour to explore Paris and Europe with Fahey’s group. It was a conversion on the road to Damascus, for Hillis’s pilgrim interest in cities now became an obsession. Returning to Brooklyn with more than twenty books on architecture and city planning, he immersed himself in study. That fall, Hillis launched a series of evening lectures on city planning at Plymouth Church, beginning with an address on England and the Liverpool transport strike of August 1911. In it, Hillis railed against the English factory system and the “industrial feeblings” it was producing—men so frail they could hardly hold a rifle. How very different from Germany! There, Hillis found the youth ruddy cheeked and strapping, their arteries “gorged with red blood.” He recoiled at the thought of depleted English workers reproducing, burdening society with “degenerate” offspring and “third and fourth-rate children.” Indeed, the “physically unfit,” Hillis ventured, “have no right to reproduce.” It was an ominous foreshadowing of things to come, as we shall see.16

The minister’s topic on the evening of October 29 was “What Our People Can Learn from Paris and France.” He began mildly enough, praising Parisians for their beaux arts culture: “The great contribution of France to modern society,” he remarked, “is the diffusion of the beautiful, until the common life is made increasingly to minister to taste and imagination.” He extolled Napoleon III for having the gumption to unleash his brilliant prefect of the Seine—Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann—on a great campaign of creative destruction that made Paris the envy of the world. Hillis struggled to convey the vast scale of Parisian modernization. “Imagine every building from Columbia Heights on the west, between Orange street and Atlantic Avenue on to the corner of Flatbush and Fulton, leveled to the ground tomorrow.”

And then imagine other houses and stores on one side of Flatbush avenue razed to the ground to make an avenue 1,200 feet wide, until the man who stands on MacMonnies’ arch at the entrance of Prospect Park, could look straight down a splendid driveway . . . with noble buildings flanking either side, until the eye rested upon a central arch, crowning the Heights, and looking out on Manhattan island.17

Haussmann’s wrecking ball kicked up a terrific squall of dust, of course. The poor were made homeless, merchants lost custom, and the populace feared that taxes would rise to Mansart’s famous roofs. But in time a great dividend began to flow. Paris boomed, the poor found work, the parks and boulevards thronged with people. And all this, Hillis told his audience—bending the truth again—was accomplished without factories, foundries, or “chimneys belching smoke.” The Parisians had created a vast work of art, a metropolis that “lay like Venus upon the bank of the river.” Millions had been spent on the city; billions were now harvested as the world came to savor its delights—“visitors from all nations of the earth, who wish to forget the roar and din and dirt of their own capitals, and rest in the sunshine of the accumulated loveliness and beauty of Paris.” Hillis further explained that in France, property rights yield to the greater good; plans for public amenities and improvements were not held hostage by private interests. He then tossed a little bomb at Tammany Hall, claiming it was full of idiots who were tone-deaf to art or beauty. But “stupidity, thank God, cannot live forever,” he sighed, hopeful that “apoplexy and diabetes” would soon whisk away to Green-Wood Cemetery such “obstacles to progress and the beautiful.”18

As the helmsman of one of America’s most influential churches, Hillis had a powerful platform from which to preach his city-beautiful gospel. But he also realized that an improvement campaign of the magnitude he envisioned would require expertise well beyond his own. And he had just the person in mind. A week before his Paris sermon, Hillis wrote to an old friend in Chicago, one Daniel Hudson Burnham, master planner of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and arguably the most influential architect in the United States at the time. As the exposition’s director of works, Burnham had brought in an exclusive cohort of East Coast architects, all practitioners of beaux arts neoclassicism, to design its main buildings—dealing a crippling blow to the pioneering Chicago school, crucible of the modern skyscraper, that Burnham himself had helped found. The aesthetic and visual unity of the “White City” was meant to impart a sanctioned message of civic idealism to a nation swelling with immigrants on the verge of precipitous change. The enormous popularity of the Columbian Exposition—twenty-seven million visitors over a six-month period—helped make academic classicism the style of choice for American civic and institutional buildings for a generation. Burnham’s practice boomed as a “City Beautiful” movement swept the nation in the wake of the fair, his firm landing plum jobs like the Flatiron Building in New York and Washington’s Union Station. Burnham was in even greater demand as an urban planner. In 1901 he was appointed to the Senate Park Commission, along with Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and two colleagues from the World’s Fair—Charles Follen McKim and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The “McMillan Commission,” as it became known, applied City Beautiful ideals to draft a plan for Washington and its monumental core, faithful to L’Enfant’s original vision for the capital. In 1903, Burnham and his young acolyte, Edward H. Bennett, were hired by a committee of citizens to guide the growth of San Francisco, and—three years later—by the Commercial Club of Chicago to develop a comprehensive plan for that city and its surrounding region.

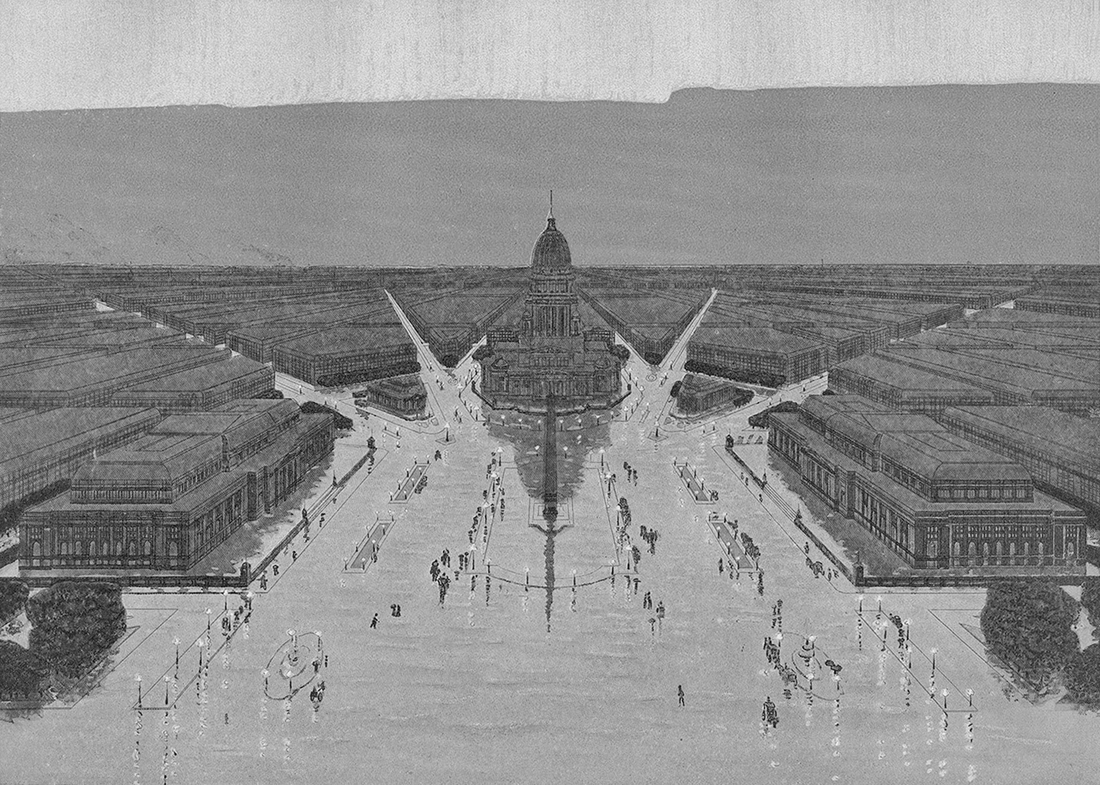

Hillis and Burnham had been part of the same social circles in Chicago (Central Church, where Hillis was pastor in the 1890s, was later demolished to make way for a Burnham building—the great Marshall Field flagship store). The minister wrote Burnham with great enthusiasm, hopeful that with some professional direction “even in ugly Brooklyn beauty may yet be born.”19 Burnham immediately posted Hillis a copy of his 1909 Plan of Chicago, along with a set of lantern slides and notes for a lecture. With these, the minister would introduce New York to the man who turned the hog-butchering, wheat-stacking Windy City into a palace of art and culture. On Sunday, November 5, 1911, Hillis told his congregants that an urban revolution was under way, a “revolt against . . . ugliness and unhealthiness” sweeping the world’s cities with “all the power and majesty of a mighty wave, and the beauty of a summer’s day.” In its wake there was “scarcely a great capital whose rulers are not asking how to arrest the evil within the walls.” He described efforts in Paris and London to eliminate “old rookeries and tenements,” and then lifted a great folio above the pulpit like a latter-day Moses. “This large book of plates that I hold in my hand,” he announced, “represents the work of the most distinguished city builder now living, and perhaps that has ever lived—Daniel H. Burnham.” He praised the Chicagoan’s earlier leadership of the Senate Park Commission in drafting a new plan for Washington. “Study that plan as you would study a snow-crystal,” he counseled, for the city it promised would be “as perfect as a pod plucked from the Tree of Life.” It should be distributed throughout the land, “framed and hung on the walls of every public school building in the United States.” For this was no mere schema for bureaucrats, but an inspired diagram that “fills the eye and satisfies the imagination,” gushed Hillis, “giving one a foretaste and hint of what the new city of God is to be when its walls of jasper and gates of amethyst and pearl ravish the adoring eyes of the pilgrim.”20 Having duly established city planning as God’s work—and Burnham as his angel—Hillis outlined a vision for Brooklyn that would have made even the great Chicago planner proud.

Jules Guerin, View, looking west, of the proposed Civic Center plaza and buildings. From Plan of Chicago (1909).

While Manhattan was undeniably “the most striking exhibition of what the genius of man can do in two centuries,” Hillis cautioned that it was yet an island, with fixed boundaries that put severe limits on development. However mighty, New York was but a little “cherry stone . . . carved ever so delicately”; Brooklyn was a vast tableau whose natural endowments gave it nearly boundless growth potential. It had all the ingredients for urban greatness. “Modern city building means scope, horizon, distant elevations, high ground in the center, sloping plains, variegated shore lines,” Hillis argued, “so that the landscape artist or architect can stand off like an archangel and draw freehand, with room for the elbows.” The glacier had blessed Brooklyn with high ground at Columbia Heights and above the Narrows in Bay Ridge, and at the north end of Prospect Park and Grand Army Plaza—where, from the top of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch, a panorama unfolded from Manhattan to Coney Island. And whereas undeveloped land was virtually nonexistent in Manhattan, much of Brooklyn at the time was still farmland. It was not too late to secure extensive land for a park system that would be the envy of the world. To start, Hillis asked people to imagine a great public promenade overlooking the harbor a stone’s throw from Plymouth Church at Columbia Heights. At the time, nearly all the property on the bluff above Furman Street was in private hands; public access to the sweeping vista was limited to a tiny space no more than sixty feet wide at the foot of Montague Street. Proposals to condemn properties overlooking the harbor for a public park had come and gone, handily defeated by the wealth and power of the residents. Hillis had another idea, one that may sound familiar to anyone who’s been to Brooklyn Heights. “Suppose we take Furman Street,” he ventured, “and build with steel and Portland cement a boulevard one hundred feet wide, on the level of the gardens in the rear of the Columbia Heights houses. Carry that boulevard from Joralemon Street north to a street even with the entrance to the two bridges; let the boulevard sweep to the right down this street to the entrance of the old Brooklyn Bridge, on to the entrance of the new Manhattan Bridge.” This extraordinary proposal presaged the Brooklyn-Queen Expressway and Brooklyn Heights Promenade by more than forty years.21

And the preacher was just getting started. He then proposed a new civic center at the junction of Flatbush Avenue and Fulton Street, set in a great circular open space—a Parisian rond-point like a second Grand Army Plaza. Whatever expense the city incurred in this work would be compensated by the sale of the newly valuable frontage to developers. Next he suggested drawing a great boulevard across Brooklyn’s broad chest by running Kings Highway through Bensonhurst and Dyker Heights to join Fort Hamilton Parkway. Fourth Avenue would become a tree-lined parkway, and Shore Road would extend from the Narrows to Coney Island as a grand “ocean boulevard” at water’s edge—a route first discussed in the 1890s that Moses would eventually build as the Belt Parkway. A system of parks and open spaces should be established in southern Brooklyn, extending those laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted a generation earlier. And ancient Gravesend Neck Road could be transformed into yet another grand thoroughfare, joining Avenue U on the east and Cropsey Avenue to meet up with Shore Road along Gravesend Bay. Here he suggested that Brooklyn emulate—and of course outdo—what Chicago had proposed for its lakefront by laying out “a system of islands and lagoons” from Bensonhurst to Sea Gate, “protected from surf and storm.” This blizzard of ideas begged illustration, and the Brooklyn Eagle was more than willing to help. Like many American newspapers at the time, it published the Sunday sermons of leading local ministers. But the minister’s exegesis on Brooklyn’s future was so exhilarating that the editors gave Hillis the front page, too, with a heavily illustrated feature titled “As Brooklyn Would Look under Dr. Hillis’ Improvement.”22

The Preacher of City Planning envisions an early version of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade—“a boulevard one hundred feet wide, on the level of the gardens in the rear of the Columbia Heights houses.” From Brooklyn Daily Eagle Development Series, April 26, 1912. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Of course, in the end all this urban designing was but a means to an end: improving the physical city to improve the people within—especially the poor and working classes. This was the Progressive Era, after all. “The new time in city building has come,” Hillis avowed; “let us get rid of the tenements, the dark alleys, the parkless wards. We ought ourselves to live to see the time when there shall be playgrounds within walking distance of all our poor children, parks close at hand for the people of every ward, a chance at body building for the little girls who are to be the mothers of our future Brooklyn.” Hillis clearly had great empathy for the unfortunate in society. But he cared, too, for society, and was resolute in exposing what he believed to be the costs of doing nothing—a city whose social infrastructure and tax base would be weighed down by “incompetents, intellectual and physical weaklings . . . invalidism, pauperism and insanity.” A penny spent now would save dollars and lives later. “We do not want asylums and hospitals for children we have ruined in the end,” he expounded; “we want parks, playgrounds, squares, gardens and lagoons, that shall build boys and girls at the beginning.” Hillis’s sermon, and the generous press coverage it received, launched what quickly became known as the “Brooklyn Beautiful” movement. Borough president Alfred E. Steers had been in the audience and was “almost boyishly enthusiastic” over Hillis’s ideas, vowing “to take steps immediately” to make them real. Though he had at his back Brooklyn’s most illustrious citizens, Hillis knew that for any of this to happen, it would need the sanction of a respected design professional—Daniel Burnham, for example. In fact, Hillis had vision for Brooklyn enough to spare, but he well knew that Burnham’s blessing would immediately grant the whole venture gravitas and legitimacy. The architect was formally invited to Brooklyn two weeks after the Hillis sermon, by a committee of “best men” chaired by Frederic B. Pratt, president of Pratt Institute and the son of its founder. Hillis himself wrote the Chicagoan, coaxing him to accept and apprising him of the groundswell of interest in the borough’s future. “What we all want is an opportunity to have you see Brooklyn,” Hillis wrote on November 29, “in the hope of impressing our conviction upon you that [it] . . . will offer you the greatest opportunity in the world to build a proper entrance to this American house.”23

Daniel Hudson Burnham arrived in Brooklyn on Saturday, December 16, 1911, a lion in winter with but six months to live. On the other side of the globe in India it was the last day of the great Coronation Durbar of George V, at which the regent laid the foundation stone for a new imperial capital—New Delhi, the ultimate manifestation of both the British Raj and Burnham’s City Beautiful ideals.24 In Brooklyn it was a dreary, wet day and the Chicagoan was tired—he had arrived late the night before from a meeting of the Fine Arts Commission in Washington. He was greeted at Borough Hall and then bundled off on a lengthy motor tour of the borough. Hillis, Pratt, Alfred T. White, borough president Steers, and park commissioner Michael J. Kennedy accompanied Burnham in the lead car, while following behind were three other automobiles carrying members of the press and the Citizens’ Committee that had invited him to the city. Burnham did not even get out of the car at its first stop, indicating only that the elevated rail structure between Tillary and Fulton Streets should be removed to open up views to the Brooklyn Bridge. He was taken to Wallabout Market, expressed disappointment in how the entrance to the Williamsburg Bridge was executed, and was unimpressed by work then under way on a plaza at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge. But he slowly began to revive as the motorcade made its way to East New York, where Burnham showed special interest in Highland Park. They came through Brownsville via Eastern Parkway, which the Chicagoan advised should have been more densely planted with trees—Olmsted’s elms having been set out too far apart for an effective sense of enclosure or canopy. The motorcade then headed down Kings Highway to Jamaica Bay and on to Bath Beach and Gravesend Bay. They made a dozen stops in all on the three-hour tour, capped by a climb to the roof of the Brooklyn Museum for a panoramic view of the surroundings.25

After the outing came a formal luncheon at the Hamilton Club, Brooklyn’s oldest and most august, where nearly two hundred guests had gathered to hear Burnham speak. Those expecting grand prophetic insight may well have been disappointed. Burnham made some remarks on urban improvement generally, avowing that “the bell has rung for a great race in city planning,” and then turned to a retrospective on his work and career, illustrated by stereopticon views. He said little about a Brooklyn plan beyond counseling that its scope should comprise not just the borough but—as we saw in chapter 4—all of Long Island. He also advised that a permanent committee be formed to lead the effort, composed of “the big men of the borough,” with a “big and broad man for your president,” and that—however inspired—a plan would sink fast if the public were not rallied to support it. It was Hillis, in a long and reverential tribute to the great planner, who truly roused the audience with a call “to make Brooklyn the City Useful . . . the City Convenient . . . the City Beautiful.” Doing so would not only be a good investment, but would “stop the movement of some of our best families to the suburbs.” Brooklyn would become the very entrance hall to America—“doorway to the republic . . . portico to the national house”—an urban Cinderella transformed into a city so beautiful “that men might turn their steps thither, as birds may turn toward the fountain and the garden.” The Brooklyn press treated Burnham like a prophet, the Eagle dedicating four full pages in two sections to his visit and city-planning matters in its Sunday, December 17, edition. On Monday, in place of the usual Sunday sermon, the Eagle reprinted Hillis’s full Hamilton Club address—“Brooklyn as an Opportunity in City Building.” It was no secret that Hillis and the Citizen’s Committee wanted to hire Burnham to plan the borough, “to do for Brooklyn,” as Hillis had put it in a letter, “what you are doing for Chicago.” On December 30, Hillis, Pratt, and Alfred Tredway White met with Burnham in Philadelphia and asked him to prepare “a large and comprehensive plan for Brooklyn and Long Island.” Burnham admitted that the opportunity was “attractive and even seductive,” but declined—he was too busy. He urged the men to hire instead his trusted understudy, Edward Bennett.26

A native of Bristol, England, who had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Bennett was recruited by Burnham to help with a competition for expanding the United States Military Academy at West Point. They worked closely on the San Francisco plan, and soon Burnham came to see the young Englishman as his heir. Though he had little of Burnham’s room-filling presence or propensity for self-promotion, Bennett was brilliant in his own right. It was also Bennett, more so than Burnham, who managed the daily work of the great Chicago plan. Burnham told the Brooklyn delegation that their offices were just a floor apart in the Railway Exchange Building, and he often advised Bennett on his work; the elder urbanist would have Bennett’s back, in other words. With Burnham’s endorsement—and virtual guarantee—Bennett was given the job.27 He would have to slog through political swamps as extensive as those in Chicago; for Brooklyn, then as now, was not known for easy agreement and mannerly discourse. Burnham had hardly left town when the name-calling began. By Christmas the New-York Tribune was gleefully reporting that the Borough Beautiful movement already had “the elements of a fine, all-around rough and tumble fight.” Controversy erupted over the siting of key public buildings—a new courthouse, library, police and fire headquarters, municipal offices—mainstays of the civic centers that anchored nearly all City Beautiful plans. The real problem was that several projects had been launched prior to any master plan. Two big New York firms—McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin; and Lord, Hewlett & Tallant—were already warring over the municipal building commission. Property owners clashed with the city and the American Institute of Architects over the best site for a new courthouse. So did justices of the Kings County Supreme Court, whose first-choice spot for the judicial complex—two blocks of brownstones bounded by Court, State, Clinton, and Livingston streets—was fortunately rejected by the Board of Estimate. McKim, Mead & White’s commanding Brooklyn Museum had opened on Eastern Parkway, though only a quarter of the original plan. The nearby Central Library project was also embroiled in controversy. Raymond F. Almirall had just completed a beaux arts design for Grand Army Plaza when an effort was made to move the library to a site opposite the Brooklyn Museum. Almirall’s half-built structure languished on Flatbush Avenue for decades until it was razed in 1937 for the present Brooklyn Public Library building.28

All this squabbling bored Hillis, eroding his passion for the movement he had fathered. For all his interest in human affairs, the minister had little patience for political infighting or the tumult of the public forum. And, like many brilliant souls, Hillis was better at hatching ideas than seeing them through to implementation. For a time he persevered. In late May 1912 Hillis attended the Fourth National Conference on City Planning in Boston. Speaking at a Boston City Club banquet on its last night—and following Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, progenitor of the Kennedy clan, to the podium—Hillis repeated his well-honed exegesis on civic beauty and the deterministic function of the built environment. But he argued, too, that beauty was only an outward expression of internal order—an “exterior revelation of soundness and obedience to law on the inside.” It was disobedience to the same, he stressed, that bred “ugliness and decay.” For much of his speech, Hillis dwelled not on the city proper, but on the moral and physical fitness of its citizens. He admitted being worried about the “physical constitution of the American people, our health, our bodily building up and our mental and spiritual life,” and reminded his audience of how the English working classes had “gone all to pieces,” rendering them unfit for not only physical labor but “fine thinking.” As evidence of America’s own degenerating stock of citizens, Hillis pointed to the large number of institutions that had opened for the care of the weak, ill, and insane—asylums and hospitals for “feeble-minded children, for epileptics, for the blind, deaf, lame and halt.”29 Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, another conference was being planned—this one focused on improving not the habitats of man, but his genes. The First International Eugenics Congress opened on July 24, 1912, at the University of London, chaired by Charles Darwin’s son, Leonard, and attended by more than eight hundred delegates—including Winston Churchill, Lord Balfour, and Italian statistician Corrado Gini (of the Gini coefficient). Hillis was not present, but he might as well have been; for not long afterward he began focusing his considerable energies on the stewardship and enhancement of human genetic stock. The minister of improvement had found a new muse.

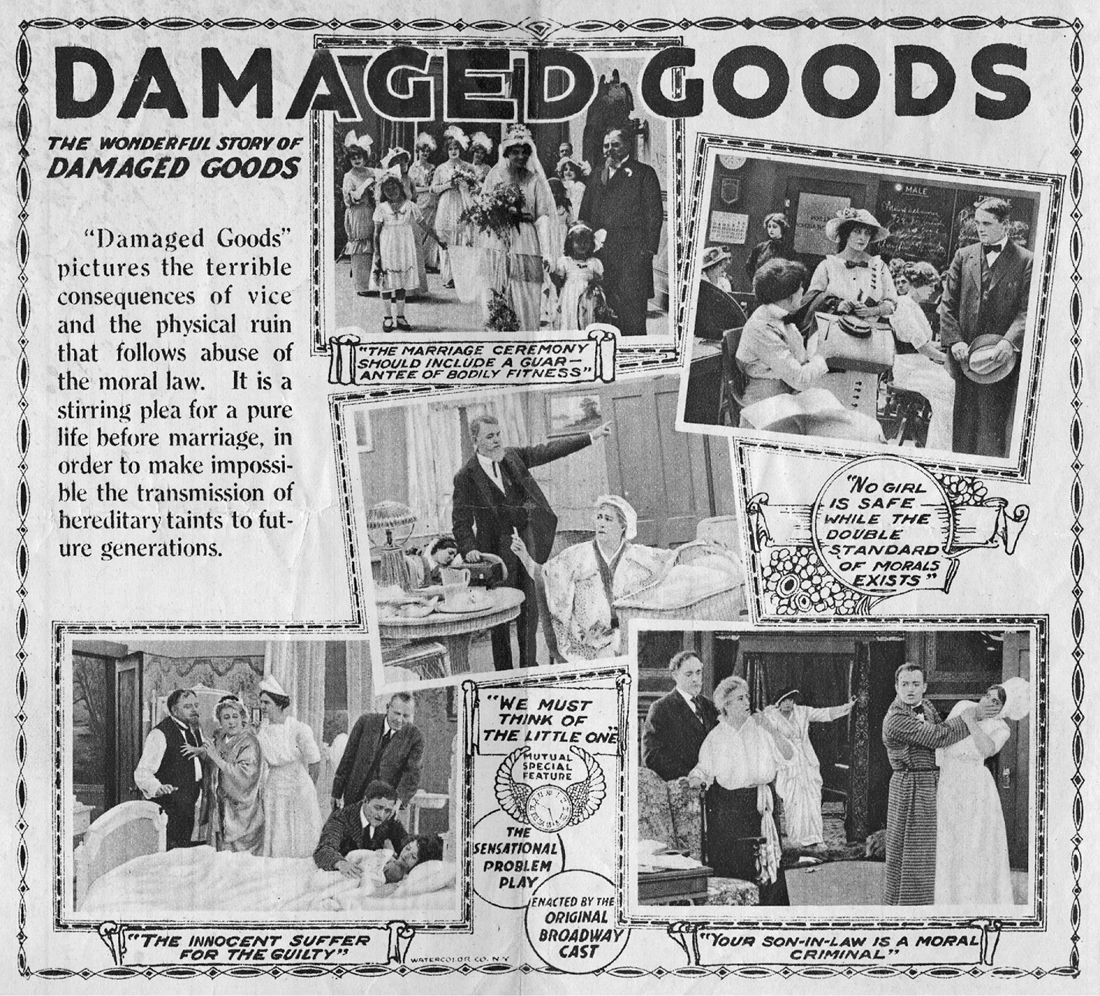

Herald for the silent-film version of Damaged Goods, starring Richard Bennett, 1914. American Film Manufacturing Company.

Hillis was almost certainly at the Fulton Theater on the rainy afternoon of March 14, 1913, the American premier of the Eugène Brieux play, Les Avariés. Novelized by Upton Sinclair as Damaged Goods, it was a morality tale about a young couple at the outset of married life. The husband learns from his doctor that he has syphilis, contracted in a tryst, but fails to refrain from sexual congress with his wife. Ignorant of her husband’s condition, she too is infected and, soon pregnant, gives birth to a syphilitic child who in turn infects his wet nurse. Praised by the New York Times as “a highly engrossing and impressive affair,” the play—celebrated Broadway actor Richard Bennett played the lead—ended with a lecture on the need for regulating marriage in the interest of public health, its basic message that individual freedom should be subordinate to the interests and welfare of society at large. Damaged Goods brought the taboo subjects of sex and venereal disease out of the shadows, generating enormous interest in eugenics—especially among clergy, who approved a lion’s share of marriages. In June, Hillis announced that he would lay aside other work to “push the eugenics campaign.” He appeared with Richard Bennett at a eugenics forum that month, and invited the actor to speak at Plymouth Church in the fall. He began addressing the subject in lectures and sermons. At the West Side YMCA just before Thanksgiving, Hillis argued that eugenic marriage laws—prohibiting the union of those deemed unfit to reproduce, including criminals, the insane, and “nervous feeblings”—would make America home to “the finest types of humanity the world has ever seen.” As enthusiastic now about eugenics as he had been about the City Beautiful, Hillis looked up another old Midwest acquaintance, John Harvey Kellogg, a medical doctor who ran an institute for holistic healing in Battle Creek, Michigan.30

Kellogg was as complex as he was controversial. A macrobiotic vegetarian who enjoyed yogurt enemas, he and his brother had developed a breakfast cereal—by forcing boiled dough between steel rollers and toasting the “flakes”—that brought both men enormous wealth. Kellogg believed that unregulated sexuality was the cause of all human vice and suffering. He waged a relentless campaign against the passions of the human body, treating chronic masturbators with genital cages, spiked penis rings, and carbolic acid applied to the clitoris. He and his wife were themselves celibate; their eleven children were all adopted, two from Mexico.31 This notwithstanding—and despite having personally treated Sojourner Truth, using skin grafts from his own leg—Kellogg was a committed segregationist who believed the nation’s future depended on a comprehensive program of “racial hygiene.” In 1906 he established the Race Betterment Foundation with zoologist Charles B. Davenport and the brilliant Yale economist Irving Fisher. How Hillis and Kellogg first met is unknown, but they clearly admired one another (the latter named his youngest son Newell after the minister, and Hillis’s daughter, Nathalie, later married a Kellogg). In the summer of 1913, Hillis proposed organizing a national conference on race and breeding—what would become the First National Conference on Race Betterment. He and Kellogg formed its executive committee, along with Fisher, crusading journalist Jacob A. Riis, and Anglo-Irish unionist and member of Parliament Sir Horace Plunkett. Held in Battle Creek in January 1914, the conference tackled questions at the very core of human existence—“race questions, biologic questions . . . whose branches cast their shadows over every phase of human life.” Its official mission was as simple as it was disconcerting—“to assemble evidence as to the extent to which degenerative tendencies are actively at work in America.”32

Despite the presence of many distinguished guests—Booker T. Washington, former Harvard president Charles W. Eliot, conservationist Gifford Pinchot, Melvil Dewey of the Dewey decimal system, educator and suffragist Caroline Bartlett Crane—there was an air of bumpkin artlessness to the conference, like a gaggle of farmhands trying to breed a better human goat. Indeed, as Kellogg put it in his opening address, “We have wonderful new races of horses, cows and pigs. Why should we not have a new and improved race of men?” Topics included the benefits of segregation, raising “better babies,” the alarming fecundity of recent immigrants, moral deterioration of women, and the perils of smoke and drink. There were lectures titled “Prostitution and the Cigarette,” “The Function of the Dentist in Race Betterment,” and “America’s Oriental Problem.” The most popular talks dealt with conjugal health tests to prevent “vicious selection in marriage.” Hillis spoke on “the deterioration of our factory classes,” warning that the dissolution of old Puritan bloodlines and the rising tide of immigration meant race extinction—“a Niagara of muddy waters fouling the pure springs of American life.” Blacks, he reasoned, should avoid the urban north for their own good. They did well enough “so long as they live on the Southern plantations,” he surmised; but “bring them into the great city, put them into competition with the white race, and they suffer beyond all words.” But he blamed affluent whites for the general shredding of America’s moral fabric—especially the triumph of “that diseased hag named Lust, that has so long masqueraded as an angel of light.” The minister remained hopeful nonetheless, for with new laws and concerted effort, “an elect group, an aristocracy of health” might emerge from the muck, breeding up a new stock of Americans—“taller, stronger, healthier, handsomer.”33

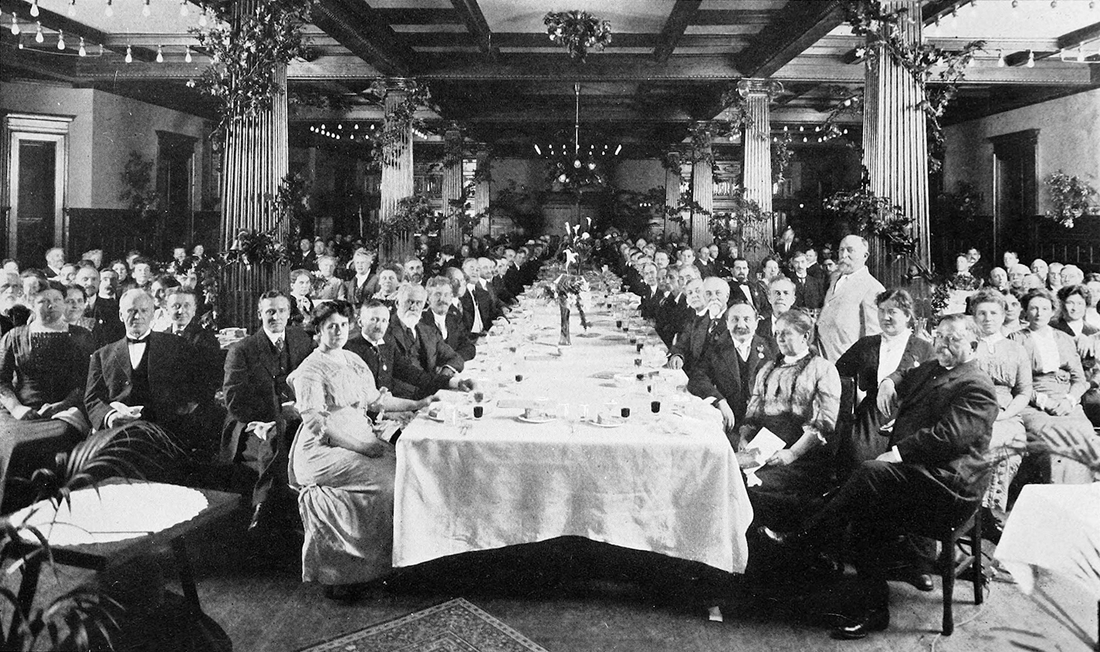

Banquet at the First National Conference on Race Betterment, Battle Creek, Michigan, which Newell Dwight Hillis conceived and organized with John Harvey Kellogg of breakfast-cereal fame. From Proceedings of the First National Conference on Race Betterment (1914).

The Race Betterment conference was a huge success, drawing more than two thousand people to some sessions.34 Its message reached far beyond Battle Creek, carried by newspapers across the country and to Europe by Pathé Frères. In Brooklyn, the Eagle dedicated a two-page spread in its January 19 issue to the conference. In the lead article, Hillis reiterated his call for marriage laws to “eliminate the defectives,” and warned that despite the many young sprouts at its base, the mighty elm of nationhood “was dying at the top.” The movement Hillis helped launch gathered force in the 1920s, leading to antimiscegenation and compulsory sterilization laws in dozens of states. By the end of the decade eugenics had become widely accepted as a means of dealing with what Margaret Sanger called “the most urgent problem today . . . how to limit and discourage the over fertility of the mentally and physically defective.” The Germans heartily concurred; there, the American eugenics movement became the model for systematic Nazi efforts to create an Aryan master race. The 1933 German sterilization law, enacted six months after Hitler became chancellor, virtually duplicated a program to eliminate “degenerate stock” that Harry Hamilton Laughlin—a close friend of Kellogg’s and author of Eugenical Sterilization in the United States—had presented at Battle Creek, and that was the template for racial hygiene laws in more than thirty states. Laughlin was so revered by the Germans that the University of Heidelberg granted him an honorary doctorate in 1936. And the admiration was mutual. In 1934, the editors of the august New England Journal of Medicine praised Germany as “perhaps the most progressive nation in restricting fecundity among the unfit.’’35

Hillis did not live to see any of this, certainly not the terrible finale of eugenics in the 1940s. Felled by a stroke just before Christmas 1928, he lingered in a coma for nine weeks before dying peacefully on February 25. Hillis had stepped down from the Plymouth pastorate five years earlier, after a quarter century as one of America’s most powerful clergymen. In that time he wrote a thousand sermons, delivered thirty-five hundred lectures, and authored more than two dozen books, with a total circulation of a million in 1929. In fact, Hillis had begun to die in spirit years before, a unofficial casualty of the Great War. Hillis was nearly sixty when the United States entered the war in 1917, too old for the front. He offered to serve instead as chaplain for a volunteer fighting force that his old admirer Theodore Roosevelt was recruiting to fight in France—a venture Woodrow Wilson ultimately terminated. That summer Hillis toured the battlefields of France and Belgium, experiencing firsthand the ravages of war. He came back a shell of the radiant and hopeful crusader he once was, a “permanently saddened man.” He had journeyed to Europe desperate to disprove the terrible stories of German atrocities, as if his very faith in God and man depended on it. Instead he found a trail of horrors worse than anything he could have imagined, inflicted by a people he had long admired as standard-bearers of Western civilization. Germany! That mighty fountainhead of science, music, and literature, home of Kant, Goethe, and Brahms. “The cold catalogue of German atrocities,” he wrote, “makes up the most sickening page in history.” Hillis pored over war records in Belgium and France, toured ruined villages in Alsace and Lorraine, saw bombed schools and hospitals, burned cathedrals, orchards with every tree felled. He was left “nauseated, physically and mentally ill.” The campaign of devastation had been carried out with the ruthless efficiency of a machine. “For the first time in history,” wrote Hillis, “the German has reduced savagery to a science.” It would not, of course, be the last.36

And thus Newell Dwight Hillis—the unflinching improver who would build the City of God and purge from its realm the poisoned seed of thugs and villains—faced the ultimate test of his creed. Would he now advocate the sterilization of an entire race, of noble Christian Nordics, no less? And his answer was yes. Alone now in a Gethsemane of his own making, Hillis wrote one last book, a long and bitter jeremiad brimming with moral outrage. It was titled The Blot on the Kaiser’s ’Scutcheon, a two-hundred-page tract on the duplicity and barbarism of Germany—that “Judas among nations.” His publisher posted a caveat in the front of the book, distancing itself from its pages, cautioning that they were “sparks struck . . . from the anvil of events,” penned in haste “on trains, in hotels, in the intervals between public addresses.” Its most explosive chapter avowed that the German race must be eliminated. “Society has organized itself against the rattlesnake and the yellow fever,” wrote Hillis; “The Boards of Health are planning to wipe out typhoid, cholera and the Black Plague. Not otherwise, lovers of their fellow man have finally become perfectly hopeless with reference to the German people.” He cited Tacitus, who wrote of Germanic barbarism two thousand years earlier, and asserted that nothing had changed but the efficacy of their predations. “The rattlesnake is larger,” he wrote, “and has more poison in the sac; the German wolf has increased in size, and where once he tore the throat of two sheep, now he can rend ten.” He turned to a plan, a draft of which was on his desk as he wrote, calling simply for the extinction of the German people. Grounded in legislation inspired by the state of Indiana’s trailblazing 1907 sterilization law, the proposal called for a world conference “to consider the sterilization of the ten million German soldiers, and the segregation of their women.” Hillis cheered this final solution; for “when this generation of Germans goes, civilized cities, states and races may be rid of this awful cancer that must be cut clean out of the body of society.” It was a grim agenda for a humanist and man of God, but one that—in a terrible twist of irony—might well have spared humanity the horrors of Dachau, Buchenwald, and Auschwitz.37