CHAPTER 6

THE ISLE OF OFFAL

AND BONES

Waft, waft, ye summer breezes,

Barren Island’s fearful smell . . .

—BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, SEPTEMBER 1, 1897

In September 1887 the famed thoroughbred Lucky B was stricken by equine meningitis at the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack. Its grieving owner—millionaire California developer Elias “Lucky” Baldwin—revealed that his namesake steed would be buried in the Coney Island Jockey Club’s equestrian cemetery, where the steed’s remains would mingle with those of several other turf luminaries—the $29,000 filly Dew Drop, felled by stomach cancer; Vera, star of the stable of R. Porter Ashe (scion of the founding family of Asheville, North Carolina), whose neck was snapped in a fall. The fate of these priceless thoroughbreds was far kinder than what awaited Gotham’s vast army of workhorse nags, the lowly beasts of burden that were the city’s primary source of motive power well into the 1920s. The destiny of these and other creatures lost and spent was a remote corner of New York City known as Barren Island. Many miles and a world away from the centers of metropolitan life, the shifting sea-swept isle was a realm of literal fire and brimstone—the setting of dark tales that made children hug tight their dogs and elders bring in the cat. Each year there, tons of slaughterhouse offal and tens of thousands of horses and other animals—rats and cats and dogs, cows, goats, even an executed circus elephant—were cut, boiled, pressed, and burned into the afterlife, in a grim and sprawling tryworks that eventually became the largest waste-processing and “reduction” complex in the world. It was Golgotha by the Sea, smelled long before seen, the “Place of Awful Stenches.”1

Barren Island was called equan-tah-ohke by the Canarsee Indians—“broken lands”—Anglicized as Equendito. It was conveyed to Samuel Spicer and John Tilton in May 1664 by two Canarsee tribesmen—Wawamatt Tappa and Kacha-washke—in exchange for a kettle, coats and shirts, a gun, powder and lead, and “a quantity of Brandie wine, already paid,” and excepting “one half of all such whale-fish that shall by wind and storms be cast upon the said Island.” On early maps, the island appears as a roughly triangular spit of sand on the southwest edge of Jamaica Bay. Its uplands were originally forested with Atlantic white cedar, but before 1820 the island was apparently “destitute of trees, producing only sedge, affording coarse pasture”—a state that no doubt helped mutate the Dutch ’t Beeren Eylandt (Bearn Island) into Barren Island, which itself appears on maps as early as 1731. It was fringed to the north by creek-carved salt marshes and exposed to the Atlantic on the south—a place known as Hoopaninak by the Canarsee and later named Pelican Beach. It wasn’t until about 1890 that natural sand deposition had extended Rockaway Peninsula to the west past Barren Island, shielding it from the sea and creating the present geography of Jamaica Bay. The diurnal action of strong tides flushing the vast bay had carved a deep channel along the island’s east bank; an 1844 coastal survey indicates depths of up to forty feet a stone’s throw from shore. This allowed relatively large vessels to dock right up against the island, the only one so accessible in the area.2

Barren Island was used by Native Americans for hunting and fishing, but no evidence has ever been found of permanent settlement. Nor did its succession of early European owners use it for more than grazing livestock and harvesting salt hay. It was not until the end of the eighteenth century that the first substantial structure appeared—a “rude house at the east end,” according to antiquarian chronicler Anson Dubois, “where fishermen and sportsmen were entertained.” Constructed by Nicholas Dooley, self-styled “King of the Island,” the building stood as late as the 1880s. Lost souls and flotsam were often brought to Dooley’s door. In 1807 a fisherman found a little girl wandering the marsh, a piece of fat pork in one hand, a sea biscuit in the other. Like the “whale-fish” that would wash up on the beach, she had no name, no identification. The child was taken to the house and eventually became part of the Dooley family, raised as Julia Ann. Years later the woman was reunited with her mother, who recognized her daughter by a half-moon birthmark on her leg. Julia Ann, it turns out, had been kidnapped and left on the beach by a sailor her father, a prominent New York businessman, had double-crossed. Smugglers and pirates came to Barren Island, too, with the requisite buried treasure. In 1830, a Philadelphia-bound brig from New Orleans carrying cotton, sugar, and $54,000 in Mexican silver was commandeered by its crew. The mutineers killed the captain and mate and set sail for Long Island. Nearing the shore, they scuttled the ship and made way to land in two rowboats. One sank; the other reached Pelican Beach, where the surviving men buried their loot. They were soon caught, two of them later tried and hanged on Bedloes Island. The story, embellished over the years, was revived in the 1870s when the Times reported that a fisherman attempting to retrieve a lost anchor off Barren Island snagged a sailor’s chest bound with iron straps and filled with nearly $5,000 in coins so firmly fused together by time and tide that “hammer and chisel had to be used to separate them.”3

The remoteness and isolation of Barren Island—hinterland of a hinterland—made it a natural candidate for the city’s official quarantine station, and even led to its designation in 1867 as a temporary post for patients arriving via “cholera vessels, or others infected with epidemic diseases.” Plans for a permanent hospital complex on the island were scuttled, however, after health commissioners learned firsthand on a field trip just how inaccessible the place was; “the surf, it would appear, only permits of the approach of small boats in exceptionally fine weather.” Paradoxically, it was this inaccessibility and isolation that led to the island’s industrial development, attracting processes too noisome or polluting to be tolerated in the city proper. The opening of the first such plant brought this far-off wild place into the pale of metropolis. It was Lefferts R. Cornell, a distant relative of the founder of Cornell University, who launched this formative chapter in the island’s history, securing in 1855 a contract to collect and dispose of “all the night-soil, garbage, and dead animals” from the streets of New York and Brooklyn. Cornell erected a small plant on the island’s east bank, where carcasses were processed into a fertilizer ingredient he shipped to his London investor—the Nitro-Phosphate Company, whose “Patent Blood Manure” offered farmers an alternative to rapidly diminishing supplies of Peruvian guano. The product was “composed of Bones dissolved with sulfuric acid,” described a contemporary advertisement, “to which is added about 1,500 lbs. of pure Blood to every ton of the Manure.” The Agricultural Gazette praised Nitro-Phosphate’s artificial manure “as nearly perfect, whether for roots or corn.” It won accolades at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, where—coincidentally—Charles Babbage introduced his “analytical machine,” progenitor of the modern computer. But Cornell soon had competition. William B. Reynolds opened a similar plant a year or so after Cornell, whose city contracts he eventually bought out. He and his two partners—including Charles Pratt, founder of Pratt Institute and one of John D. Rockefeller’s original Standard Oil trustees—shipped their fertilizers as far away as Prussia, where they were prized by vintners in the Rhine valley. Thus, perhaps, did the souls of New York’s nameless nags and curs return home in bottles of Spätburgunder and Riesling.4

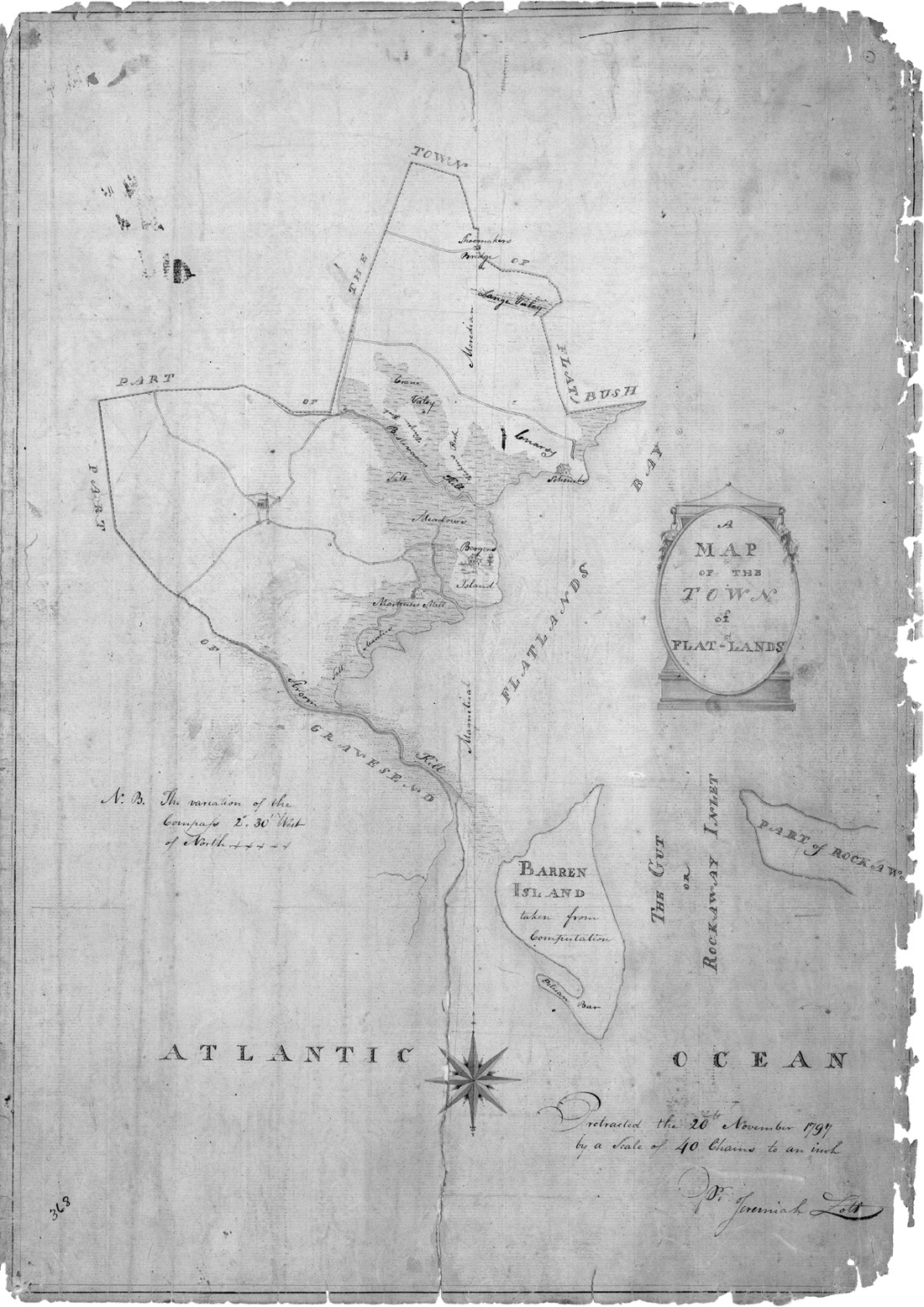

A Map of the Town of Flat-Lands, 1797, showing Barren Island and Pelican Bar in lower-right quadrant. New York State Archives—Survey maps of lands in New York State, 1711–1913 (Series A0273–78, Map #368).

Many of these creatures—dogs, especially—had been spirited off well before their time. Until the mid-nineteenth century, dogs in New York City roamed the streets with complete freedom, often biting people and causing nightly mayhem with their howls and barking. Eventually public outrage grew to the point that laws were passed requiring dogs to be muzzled and authorizing the capture and dispatch of any left unrestrained on the street. Driving the new legislation was fear of rabies, known then as hydrophobia; for “no animal-borne illness,” writes historian Jessica Wang, “struck a greater sense of terror in humans.” The disease was thought to be most prevalent in summer months, and “ordinances authorizing the collection and disposal of unmuzzled dogs eventually became an annual summer ritual.” In Brooklyn, citizens were authorized to kill any unmuzzled dog running free on the street. Broadsides would go up toward the end of June, “announcing to the boys that the season has come again when stealing dogs may be legitimately reckoned as the largest source of income.” With a fifty-cent reward on their heads, it was “profitable to steal and indeed raise pups for the New-York market.” Some found grim humor in this annual rite of canine catching. In August 1855 the New York Times lampooned a “Distressed Widow” who appeared at the newspaper’s offices one day seeking help in finding a lost King Charles spaniel. Mrs. Sob-easy, as the columnist called her, was advised to visit the new city pound. There, a worker confessed to the widow and her escort that with “lard . . . so high now and venison scarce,” dogs had become prized for more than companionship. Thousands of Rovers, Spots, and Fidos had already been turned in for cash that summer by heartless, enterprising urchins. Some were retrieved by their owners—for a fee, of course. Others were given a one-way ride to Jamaica Bay; for the real money was in selling the animals to tryworks operators like Cornell and Reynolds. Of some thirty-six hundred dogs collected by the city pound that summer, only four hundred were redeemed. The rest? “We put them in a big box,” explained the pound man, “and let on the Croton water till they are drownded . . . I tell you, ladies, it’s very doleful to hear ’em howl out of their box when the water’s comin’ in, all in different voices so.” He tried to spare the distraught pair further details; but the widow was persistent: “You spoke of Barren Island, my good man; I suppose that is the Cemetery where they are buried? Is there any ferry to the place?” Alas there was not, he allowed, but then assured her “that it was a very romantic place for a dog to rest in, after his life’s labors were ended . . . the ocean is always performing a dirge.”5

However numerous, city dogs were small and scrawny. The real prize in the “reduction” trade was the horse. With the urban horse today relegated to the occasional police mount or pulling contested Central Park carriages, it is difficult to picture the mammoth role this living machine played in the economy and daily life of American cities prior to 1920. By the end of the nineteenth century there were some 130,000 horses in Manhattan alone, with tens of thousands more in Brooklyn and Queens. Horses hauled much of the city’s passenger traffic and nearly all of its freight (an 1885 study revealed that nearly eight thousand horse-drawn vehicles passed the corner of Broadway and Pine Street in lower Manhattan on a typical day). The animals supported a vast network of trades, including blacksmith shops, wheelwrights, and saddle makers. With the introduction of the “horsecar” in the 1830s, they even helped expand the footprint of the city. Essentially a carriage on rails, the horsecar might not seem like revolutionary technology, but the minimal friction of steel on steel enabled a fourfold increase in a horse’s pulling power. This allowed operators to carry a larger payload per animal and thus charge lower fares, which increased ridership and led companies to expand their systems. Because these lines required a costly up-front investment in track, routes were “sticky” and not easily changed. To real estate developers, this was a bankable asset. Wherever the horsecar lines went, houses followed, driving residential development outward from the city center along corridors served by the new mode of transit.6

W. A. Rogers, At the Dog Pound—The Rescue of a Pet. From Harper’s Weekly, June 16, 1883.

The urban horse produced an avalanche of waste—an average of 50 pounds of manure per animal every day (about 7 tons a year). New York’s horses thus churned out an astonishing 1.8 billion pounds of dung annually, the equivalent in weight of twenty Iowa-class battleships. Manure was a rich source of fertilizer, of course, and local farmers carted off much of it. But it was heavy, consisting mostly of water, and difficult to move in quantity. As farms were forced farther out by the spreading city, and with lighter, more potent fertilizers increasingly available—like those manufactured at Barren Island—city stables couldn’t give the stuff away. It was simply not worth moving, and thus often piled up on streets and empty lots, bathing blocks in barnyard stench, attracting rats, and breeding biblical clouds of flies. The deluge created a public health menace that became one of the most fretted-over city-planning issues at the time. Horses also aged, sickened, and died in large numbers every year—especially when a deadly contagion tore through the horse population, such as the Great Epizootic of 1872, an outbreak of equine influenza that ground transportation to a halt throughout the northeastern states. The dead were collected from street and stable, hauled to a Hudson River pier, and loaded for Barren Island on scows or an aged schooner known as the “horse boat.” There the animals would render their last service to humankind through a process of reduction that began as soon as the boat docked. The carcasses were lifted from the deck, skinned, and gutted, and the flesh was cut off and carted to a boiler house. As the Brooklyn Eagle described it in 1861, the carrion was then “placed in large boilers, and boiled until every particle of fat is taken from it.” As anyone who has made bone broth or chicken stock knows, heat breaks down fat molecules, which rise to the surface. Skimmed off and congealed, the horse fat was sold to chandlers to make soaps and candles (Gotham’s horses, in death, helped illuminate the very shops and homes they trotted past in life). Bones were carved into buttons, combs, and knife handles or burned to make “bone black,” used as a pigment and as a filter in the sugar-refining process. Hides were salted down and sold to tanners; hooves were rendered for glue. To paraphrase Chicago meatpacking magnate Gustavus Swift, everything of the horse but its snort was put to good use.7

The Close of a Career in New York, c. 1900. Detroit Publishing Company Photographic Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In theory, at least. The early Barren Island carcass processors used crude equipment in hastily built structures, and were not very efficient extractors of value from the city’s expired animals. Bad weather, shipping delays, worker shortages, and market fluctuations played havoc with operations—especially those on fixed city contracts. If there was a glut on the island, or if demand for products fell, carcasses would simply be dumped en route, fouling the shores of the upper and lower bay and forcing those seeking the delights of the water’s edge “to give up the pleasure,” noted the Times, “because of the hideous objects that floated on the waves.” Barren Island itself was strewn with the detritus of death. In May 1866 Jackson S. Schultz, head of the newly formed Metropolitan Board of Health—the first such municipal authority in the United States—made an inspection tour of the island in response to complaints about horrific odors voiced by the residents of Gravesend, two miles distant. He discovered there “thousands of dead animals lying under the sun . . . sending forth a highly offensive stench.” He also learned that these creatures, though dead, had yet a disconcerting ability to wander; for the carcasses were “washed away by every high tide, and . . . becoming bladders, float up and down along the shore.” Wind and waves would push the grim flotsam into a small cove on the west side of Barren Island, which still carries the doleful name Dead Horse Bay. In an era before municipal consolidation, multiple parties would often be paid to remove the same wandering carcass that New Yorkers had already paid a contractor to dispose of. Washed up at Bay Ridge, the animal would be carted afresh to a Brooklyn collection pier only to be dumped again and surface next perhaps on Staten Island. “As a general rule, one funeral is deemed sufficient for a human being,” clowned the New York Times, “but when a New-York horse ‘shuffles off’ . . . three of the most enlightened counties in the state give him each a separate funeral, and spend money ad libitum to do honor to his remains.” Indeed, “no death in the Republic causes more trouble or anguish than that of the New-York horse.”8

Other creatures, too, were made part of Barren Island’s baleful menagerie. In 1880 alone, more than 8,000 dogs ended their days on the isle, in the process destroying “more intelligence, more faithfulness and more common sense,” lamented the Times, “than ever bothered some of their persecutors.” Nine years later, the vast rendering and fertilizer works of P. White and Sons—heir to the Cornell operation—processed a staggering 23,765 cats and dogs, along with more than 7,000 horses, 2,565 cows and calves, 699 sheep, 171 goats, 26 hogs and pigs, 461 barrels of poultry, and 125 barrels of rabbits. Also boiled off that year were three deer, a bear and an alligator. But the most unusual creature rendered to its essence on Barren Island was a thirty-year-old Asian elephant named Pilot. Captured in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) around 1870, the animal was acquired by a London investor, but sold after stomping his keeper “into an unrecognizable and shapeless mass.” The elephant’s buyer was American circus pioneer P. T. Barnum, who shipped the beast with his trunk chained to his belly and his legs so tightly fettered that he could move only inches at a time. Once in the United States, the elephant manifested still worse behavior—especially, it seems, after being upstaged by the beloved gentle giant, Jumbo, largest circus elephant in American history. Pilot bruised attendants, killed dogs, broke loose in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and struck a keeper unconscious with his trunk at Madison Square Garden. Brutally shackled and beaten after yet another incident, the animal became crazed with rage, battering down a chimney and bellowing so loudly that he could be heard for blocks around Madison Square. Barnum’s partner, James A. Bailey, ordered the elephant killed—an extraordinary move given his value. It took three shots of a .48 caliber navy revolver to get the job done. A team of twenty “white-aproned and bloody-armed butchers” then descended on the carcass, and “before midnight proud Pilot was in small pieces” (the animal’s stall mate, Gipsey, was so traumatized by the butchery that she refused to eat for days afterward). A leg was claimed by a veterinary college, the tusks turned into billiard balls; but most of Pilot was loaded on Charon’s boat for Barren Island, “to be rendered into glue, buttons and other substances.” This was an especially harsh fate for a circus elephant, even a murderous one. When another Barnum and Bailey killer pachyderm, Albert, was executed by a New Hampshire firing squad for crushing his keeper, his remains were sent to the Smithsonian. But Pilot’s “long career of wickedness,” as one reporter put it, was deemed deserving of exile to the dreaded isle.9

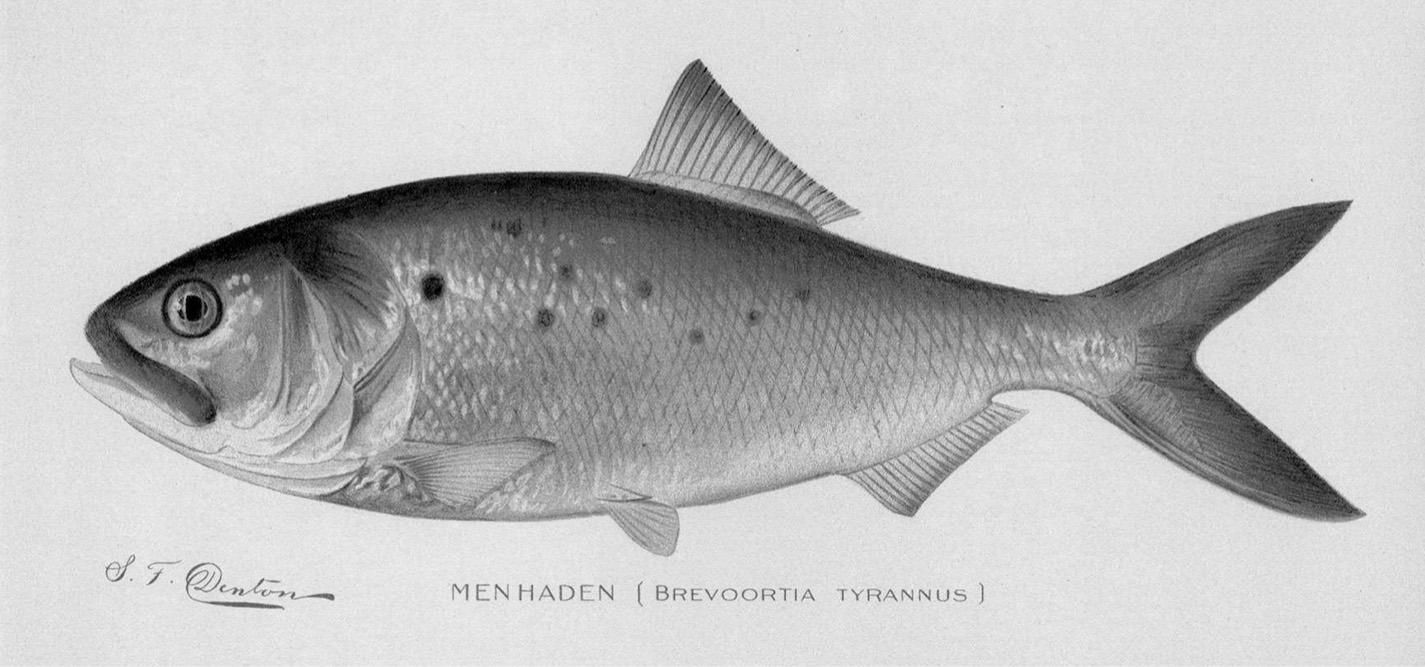

Fish, by the tens of millions, were also rendered more useful to humanity on Barren Island, which became a major processing center for Atlantic menhaden in the decade following the Civil War. The oily, nutrient-rich fish had been used by Native Americans for centuries as a fertilizer for maize, a practice adopted by early New England colonists. In his 1637 New English Canaan, Thomas Morton noted that a thousand fish were used to fertilize a single acre of land, which “thus dressed will produce and yeald so much corne as 3 acres without fish.” The name menhaden was in fact derived from the Narragansett munnawhatteaûg, which meant “that which manures.” In New York, the fish was more commonly known as mossbunker, from the Dutch marsbanker (maasbanker), a species of Atlantic mackerel it resembled. Oddly, the silvery pelagic was first described for science in 1799 by one of America’s first great architects, Benjamin Henry Latrobe. An English émigré, Latrobe supervised construction of the US Capitol and—among many other commissions—designed the east and west colonnades at the White House. He was also an accomplished amateur naturalist who researched digger wasps and the geology of Virginia. Latrobe gave the toothless plankton-eater a delightfully menacing name—Brevoortia tyrannus—because of a small parasitic isopod or fish louse often found in its mouth. The louse, which Latrobe named Oniscus praegustator, “fares sumptuously every day,” he observed, though he couldn’t quite tell whether the freeloader was there “by force, or by favor.” A good patriot, he chose the former: “The oniscus resembles the minion of a tyrant,” wrote Latrobe; “for he is not without those who suck him.” The architect thus named his hapless autocrat tyrannus.10

By whatever name, the fish was as numerous as the stars of heaven—a pelagic passenger pigeon that darkened the seas the way great flocks of the doomed bird once blacked out American skies. The physician-naturalist Samuel L. Mitchill described the “prodigious numbers” of menhaden in New York waters in 1814: “From the high banks of Montock” [sic], he wrote, “I have seen acres of them purpling the waters.” In 1819 a Newport sea captain sailed through a single school off New England that stretched two miles wide and a staggering forty miles long. Unlike the passenger pigeon, which market hunters blasted toward extinction, the titanic menhaden shoals were unmolested by man as they migrated up the coast each spring. Relatively flavorless and full of bones, the fish was seldom eaten, and after the colonial era its utility as a fertilizer was largely forgotten. It was rising demand for oil, for lighting and lubricating America’s Industrial Revolution, that led to a rediscovery of the species—this time as little silver oil wells. The high oil content of menhaden transformed Brevoortia tyrannus from a runt of the sea into one of its most profitable resources. By the 1880s, nearly five hundred million pounds of menhaden were being harvested every year—more than all other fish species combined, including cod, mackerel, salmon, herring, shad, and Great Lakes whitefish. Boiled, skimmed, and pressed from the fish, the oil was favored by coal miners as headlamp fuel, and used to manufacture rope, mix paint, and curry leather. The inexpensive fish oil was used to cut more costly lubricants, such as linseed oil, and in its purest form was even marketed for cooking as olive oil. Menhaden might be mere foodstuff for a sperm whale, but it soon beat out its predator in the American marketplace. The oil extracted from the annual menhaden haul in the 1870s exceeded by some 200,000 gallons that harvested from whales. Indeed, Latrobe’s little tyrant helped finish off the dying whaling industry and thus may well have helped save its colossal nemesis from extinction. By the end of the century, prey had usurped predator; for what was often sold as whale oil for lamps and lubricant was mostly menhaden oil.11

It was certainly a lot easier to get oil from a small fish than from a fifty-ton cetacean. On Barren Island at least four plants were engaged in this malodorous and messy work by the 1880s, including Barren Island Menhaden, the E. Frank Coe Company, and the Hawkins Brothers Fish Oil and Guano Company of Jamesport—the largest processor in the state. Each had its own fleet of fishing boats that would use purse seines to harvest fish in the New York bight. Once the boats docked, the menhaden would be bailed out of the hold in buckets. They would be chopped up and dumped into great wooden vats partially filled with water, steamed hard for an hour, then “punched and broken up” and simmered for five hours. The water and oil would then be drawn off and the broken fish or “residuum” drained and cooled for many hours more. It would then be placed in perforated iron vessels and run under hydraulic presses to wring out every last drop of water and oil. The remaining “cheese” was moved to dry in the sun on wooden platforms covering two or three acres, then packaged for sale as “fish guano.” The Barren Island plants would run twenty-four hours a day in summer, boiling through some two million menhaden every week. In the fall, when the fish were fattest, as much as six gallons of oil could be extracted per thousand fish. Though not as valuable as the oil, menhaden guano was rich in phosphates and nitrogen. It was widely used to amend the stony, depleted soils of New England and those of sandy Long Island, enabling farmers to keep productivity in step with soaring demand from the region’s growing cities.12

Sherman Foote Denton, Menhaden (Brevoortia Tyrannus). From Denton, John L. Ridgway, and Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Fish and Game of the State of New York (1901).

The Barren Island workforce consisted of a polyglot mix of mostly single men—black and white, immigrant and native born. African Americans from Virginia and Delaware worked the fish plants, while Prussians, Swedes, and English, Irish, and Swiss immigrants dominated the rendering works. Most lived in company boarding-houses, some with only ship hammocks for sleep. They only rarely left the island in warmer months, and travel in winter was almost impossible. With no bridge or causeway to the mainland, it took most of a day to get to Manhattan from Barren Island. The trip involved taking a boat (which ran only in summer) to Canarsie Landing, a railcar to East New York, and a train across Brooklyn to Fulton Ferry. The heady essence of Barren Island industry often went along for the ride. When several employees of the Edward Clark offal works attempted to board a Broadway Railroad car in 1878, the conductor informed them of a rule banning anyone reeking of rendered flesh. But the men were “strong in numbers as well as smells” and boarded the train anyway, giving the poor conductor “a sick and sorrowful time” until he flagged a policeman and had them all arrested. One worker, Thomas Murphy, sued the railroad but lost his case on appeal when the court ruled that the constitutional obligations of a common carrier did not extend to “the transportation of smells.” More or less banished from the city they served, Barren Island’s workers developed a self-contained community of their own. With ten women and twice as many hogs as men, Barren Island was hardly known for its gentility and grace. A staff writer from the Brooklyn Eagle visiting in August 1877 was received like an interloper from another galaxy. A crowd of dogs and children gathered around him as he walked the island’s sandy “Main Street,” and men so covered in filth that their faces were obscured reached out to feel his clothing. “If the reporter had dropped from the clouds,” he wrote, “he could not have created a greater sensation.”13

Far from the wardens of state, Barren Island also bred lawlessness and anarchy. In early 1874, Frank Swift, who ran the old Reynolds plant on a big city contract, was discovered to be distilling more than horseflesh. At first light on February 9, agents from the new US Bureau of Internal Revenue—tasked with enforcing an 1862 liquor tax to help pay for the Civil War—stormed the island with 120 federal troops. In one of Swift’s buildings, windows covered by horse hides, they found “an extensive distillery in full operation,” complete with immense vats filled with some fifty thousand gallons of sour mash and molasses. It was one of the largest moonshine operations uncovered in New York City during the “Whiskey Wars” of the 1870s. The agents also boarded an old schooner riding at anchor offshore, which was found to be loaded with kegs. Swift had teamed up with the notorious Brady brothers—barons of the Gotham moonshine trade—and was using the derelict two-master to haul his potent sour mash whiskey from Barren Island to a gin mill at Gold and John streets in the heavily Irish Fifth Ward, Brooklyn’s roughest neighborhood (Vinegar Hill today). Clandestine activity of this sort required discouraging the curious visitor to Barren Island, who—upon making landfall—would often be forced back to his boat by members of the notorious Bone Gang that ruled the isle before a permanent police presence was established. At the very least, he would be met by a pack of snarling dogs, animals none too trusting of man (and for good reason; most were escapees from the offal boats). By the 1880s, Barren Island’s population had doubled, but its reputation as a closed and clannish, even dangerous place only got stronger. That image was hardly eased by lurid accounts of bodies washed up on the shore. One of these bodies was that of the beautiful, doomed Fanny McKnight, daughter of a wealthy merchant who dropped out of Claverack College on the Hudson to plumb the pleasures of Gotham, where “she appears,” sniffed the New York Times, “to have led a wild life.” On July 26, 1880, McKnight boarded the excursion steamer Kill Von Kull for Coney Island but jumped overboard before the vessel reached the Iron Pier—at least according to police. The diamond rings and a large amount of cash she was carrying were never recovered, nor was the gentleman identified whom she was seen talking to just before taking leave of the deck, leading many to conclude that the wayward collegian had been robbed and thrown from the boat.14

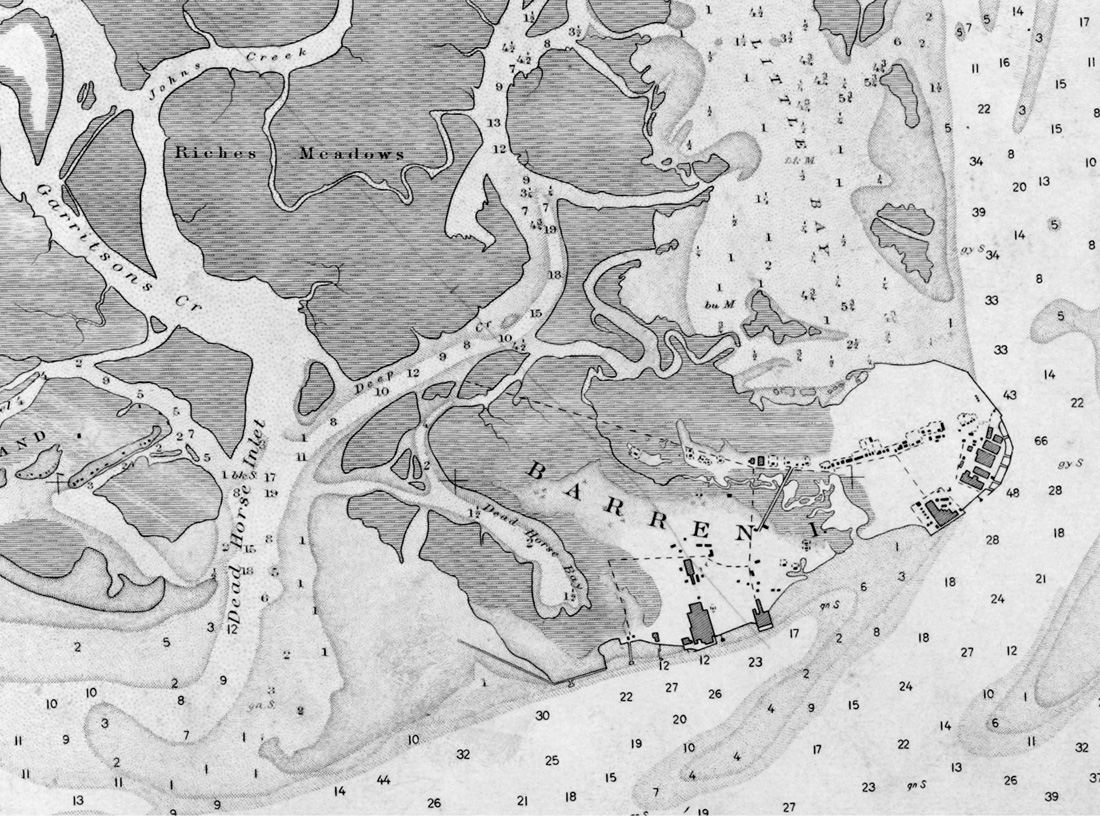

Detail from Jamaica Bay and Rockaway Inlet showing the waste treatment and rendering plants and village of Barren Island (center-right), United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1911. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

But what most outraged New Yorkers about Barren Island was not lawlessness or animal cruelty, but fearsome odors—the smell of industrial death. We can only imagine just how bad this must have been, as the olfactory dimension of the urban past is as irretrievably lost as the people who once walked the city’s streets. One account from the Civil War era described the vapors of Barren Island as “like nothing on earth,” so offensive that “if Jeff Davis would entrench himself behind a line guarded by such effluvia, his position would be impregnable.” Another favorably likened the milk-curdling breath of a homeless drunk to “the wind that blows over Barren island.” Which of the island’s rendering plants committed the most egregious crimes against the nose was hard to say. Many reported several distinctive odors, emanating—in turn—from the rendering plants, the fertilizer works, and the fish-oil factories. Putrefying horseflesh and fish-cheese drying in the sun seemed to produce the most revolting smells of all. These “foul and sickening vapors . . . carried by the wind” became an increasingly fractious political issue as nearby beaches evolved into popular summer resorts, and—especially—as residential development extended south into Flatbush and Flatlands after the city expanded sewer service to the area. The earliest objections came from Gravesend and from seasonal residents of the Rockaways, where the smells were often “so powerful that it is impossible to keep the doors or windows of dwelling houses open.”15

It was the infamous anti-Semite of Manhattan Beach, Austin Corbin, who organized the first legal battle against the olfactory scourge of Barren Island. In August 1888 his Manhattan Beach Improvement Company brought suit in Brooklyn’s supreme court, seeking damages and an injunction against each of the island’s principal rendering plants for inflicting grievous harm on the health and welfare of the public. But liberal application of that “popular tranquilizer of politicians, well known as ‘palm oil,’” assured that nothing was done to shut down the well-connected contractors. Corbin then called upon his own arsenal of political connections, firing back with a “monster petition” that went straight to Albany and the desk of his buddy Governor David B. Hill. Hill was a conservationist—he signed the legislation establishing what eventually became Adirondack Park—and immediately ordered an investigation into the Barren Island nuisance issue. Testimony was taken from scores of men and women in a hearing before the State Board of Health on November 6, 1890. Counsel for the offal processors did all they could to trip up those testifying, but were “unable to shake the witnesses on one point—that Barren Island and its foul odors was the burden of their lives.” Under oath, Charles H. Shelley, manager of Corbin’s Oriental Hotel, described the reeking medley of smells carried in the east wind—one “pungent, nauseating,” the other so violently offensive that “I have seen all the ladies on the piazza of an evening,” he related, “leave us in consequence.” The smells were so fearful in the summer of 1886, Shelley recalled, that hotel guests circulated a petition in protest. Another witness—Philip P. Simmons, who summered at Rockaway Park right in the path of winds from Barren Island—testified that “exceedingly pungent” stenches often made his wife and daughters nauseated, and one August night the fumes were so noxious that “every member of my family was waked up by the smell.” Fenwick Bergen blamed his “malarial fever” on the island’s ill winds and told of being “sick at the stomach” from a reeking cocktail of phosphates mixed with “rotten dead fish . . . rotten animals.” Others testified of smelling the island as far away as downtown Brooklyn and the Five Towns.16

The governor’s committee charged with investigating the mess proposed appointing an inspector to make biweekly reports on sanitary conditions at the rendering plants, and outlined a number of remedies for the island’s olfactory ills—covering fish kettles, sealing storage buildings, mounting fans to drive noxious vapors into disinfectant baths or back into the furnaces to be burned away. All proved ineffective; for five years later, Corbin was threatening another round of legal action after the dreadful plume from Barren Island had his guests heaving again on the verandas of the Oriental and Manhattan Beach hotels. What finally quieted the much-loathed Corbin was not remedial action but a carriage accident on his New Hampshire estate—one that dashed his brains out on a stone wall. He was thus spared knowing that matters of the nose were about to get even worse back in Brooklyn. The very summer of Corbin’s death in 1896, Colonel George E. Waring, newly appointed commissioner of the Department of Street-Cleaning—forerunner of the Sanitation Department—proposed to solve New York’s growing “garbage problem” by rendering it into soap grease and fertilizer on Barren Island. Son of a wealthy Westchester manufacturer, Waring studied agricultural engineering in college. He later managed Horace Greeley’s experimental farm, led the Thirty-Ninth New York Volunteers (the Garibaldi Hussars) in the Civil War, and helped drive Confederate forces from Missouri with General John C. Frémont. Just before the war he assisted the brilliant, irascible General Egbert L. Viele on the initial grading and drainage work for Central Park, which led to the job that made his career—helping Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux implement their competition-winning “Greensward Plan” (Waring was especially proud of having planted the iconic American elms on the Central Park Mall). Waring later designed a municipal wastewater system for Memphis, Tennessee, following a terrible outbreak of yellow fever, the first system in the nation to separate storm water runoff from sewage. He was doing similar work in New Orleans when Mayor William L. Strong tapped him to clean filth-strewn New York.17

Cleaning this Augean stable of a city was a Herculean task indeed. Waring whipped the patronage-bloated Department of Street-Cleaning into shape, giving his troops crisp white canvas uniforms, new brooms, and nifty wheeled trash bins designed by his wife. He ended the practice of dumping all the city’s refuse in the harbor, where it clogged shipping channels and befouled shores. Now only ashes and street sweepings would sleep with the fishes; dry light refuse—rags, paper, boxes, barrels, and assorted other junk—would be picked clean of usables (tin cans, for example, were melted to make window sash weights) by an army of Italian immigrant “scow trimmers” and incinerated in a Colwell furnace. Organic waste such as kitchen scraps and cast-off food—that “most troublesome element of city refuse . . . known as garbage”—Waring meant to render on Barren Island. There he would have it pressed for marketable grease and oil, or what the New York Times later called “unspeakable fats, for uses which it is a delight not to know or even imagine.” All this required, of course, that city residents separate trash into three receptacles—one for ashes, another for dry waste, and a third for garbage (a practice recently reintroduced by the Department of Sanitation). The new law was honored mostly in the breach, however, prompting an editorial in the New York Times upbraiding the “enemies of civic cleanliness” whose “inveterate habits of slovenliness and negligence” would keep the city steeped in filth. After a bidding war and backroom deals, Waring’s big garbage contract was awarded to the New-York Sanitary Utilization Company, based in Philadelphia but backed by a consortium of investors led by the same White family that had operated reduction works on Barren Island for decades (among the backers were infamous Philadelphia boss Dave Martin and Brooklyn politico Patrick H. McCarren, namesake of McCarren Park in Williamsburg). The company began construction at Barren Island in the fall of 1896—not a moment too soon for island residents. Most of the fish works had shut down by this time owing to a crash in the menhaden population. The new plant would not only solve Gotham’s garbage problem but employ Barren Island’s idled workers.18

The twin, side-by-side plants of the New-York Sanitary Utilization Company (the second one was erected to handle a subsequent Brooklyn contract) made it the largest waste-processing works in the world, capable of churning through fifteen hundred tons of garbage a day. It was designed around a state-of-the-art reduction system known as the “Arnold Process.” Garbage arriving by scow would be conveyed upward and dropped through chutes into a bank of forty-eight digesters—“perpendicular cooking tanks” each five feet wide and fifteen feet tall and capable of holding ten tons of material. Once full, these would be sealed tight and pumped with steam to cook the garbage for several hours, to break it down and neutralize bacteria. “No offensive odors can escape from the tanks,” the company promised, “and unpleasant gases will be conveyed through pipes and thrown in the form of spray upon the fires in the furnaces,” thus scrubbing the plant’s exhaust and—in theory, at least—rendering it wholly inoffensive to the nose. The contents of the digesters would then be emptied into sheet-iron receiving tanks, the liquids drained off and sent back into the boilers. The waste was then loaded into a series of Boomer & Boschert screw presses and put under several tons of pressure to squeeze out the oil and grease, which was sold for lubricants or soap making. It was next carted by tramcars to the drying room, where a “masticating machine” fed a series of cylindrical, steam-jacketed dryers, each sixteen feet long and equipped with revolving shafts armed with paddles to stir up the detritus. Once dry, the “tankage” or “oil cake” was released into hoppers, and screened, bagged, and marketed as a fertilizer ingredient. A motor room (with two big Corliss engines), pump house, office, storage facilities, and a dining hall for workers rounded out the complex, which struck observers as the very essence of efficient modernity. The Barren Island works, subject of an adoring five-page spread in Engineering News—seemed to share little with the ancient and unsavory business of waste, but rather “can only be regarded,” wrote engineer William W. Locke, “as a large chemical engineering business requiring the best scientific intelligence for its operation.”19

Had the writer consulted the plant’s operators, another picture would have emerged—of working conditions as infernal as they were hazardous. When the digester tanks were emptied, for example, the hot swill “gushed out with great force, splattering the operators and the floor until the former were hardly recognizable.” In 1898 a twenty-four-year-old African American named Robert Wedlock slipped on a wet rail and tumbled headfirst into a cart full of boiled mush as it moved into position beneath a press. Teetering on the edge, Wedlock’s shoulder blade was crushed by the descending plate before the operator could shut down the machine. A moment more, reported the Eagle, and “his head would have been severed from his body.” The worst accident occurred when an overloaded digester exploded, blowing a ten-foot hole in the roof and destroying much of the plant. The massive blast broke windows in nearly every building on Barren Island and echoed across the city. Workers—nearly all blacks and immigrant Poles and Russians—were enveloped in a violent gush of steam and boiling juice, blinding and scalding them and forcing some to leap to safety from third-floor windows. One, Antonio Carditz, was killed by a flying cast-iron boiler door; others were crushed beneath falling timbers and debris. The parboiled victims were saved only when harbor police made two five-mile motorboat dashes across Jamaica Bay to get them to hospital.20

The vast Sanitary Utilization facility also looked a whole lot better than it smelled. The effluent that was supposed to be boiled off—a noxious red-brown liquor—was in fact drained to Jamaica Bay, where it helped poison the most famous oyster beds in the United States. Windows meant to be kept closed in plant buildings were opened by workers desperate to ventilate rooms where the temperature soared to “that of a Turkish bath.” The critical scrubbing technology was either never installed or simply didn’t work, for soon the odors emanating from Barren Island—“pungent, penetrating and sickening”—were worse than ever. Even admiring engineer Locke admitted that the strange burnt-caramel odor from the Barren Island complex was “capable of a range . . . and penetration equal to that of our modern coast defense rifles.” And there were more people than ever now in the line of fire—in rapidly developing communities around Jamaica Bay like Bergen Beach, the Rockaways, even Richmond Hill. Complaints came in from communities twelve miles from Barren Island, suggesting an odorshed that took in lower Manhattan, all of Brooklyn, and points as far east as Forest Hills, Rockville Center, and Long Beach. Outrage over the new pollutants was fast and fierce, but not without moments of poetic wit. As a woman named “Kate” versified in a letter to the Eagle,

Waft, waft, ye summer breezes,

Barren Island’s fearful smell;

If the officials don’t soon stop it,

We’ll wish them safe in Hell.21

Others got straight to the point, dismissing the city’s argument “that smells are a part of civilization and that the world would have to return to the savage state and live in the woods to avoid the nuisance.” Civic groups denounced the garbage plant’s gut-wrenching emanations, reportedly capable of producing a “headache in three minutes.” Dr. Samuel Kohn of Arverne in the Rockaways caused mirth at a state Board of Health inquiry by describing the garbage smell as “awfully offal,” telling how residents in his community would “suddenly be awakened from a sound sleep with a suffocating, irritating feeling in the throat” and quickly become “seized with nausea.” When the flummoxed chairman of the inquiry asked Kohn to recommend a better place for the city’s garbage, he suggested—what else?—New Jersey. Waring also testified before the panel, ridiculing complainants as misguided “victims of lively imaginations.” He asserted that his pet reduction plant produced no odors offensive “in the proper sense of the word,” and described the only smell there as “one like boiling cabbage”—so unobjectionable that “only a supersensitive stomach would be effected even at the factory.”22

For the next twenty years, the city fought a running battle with state authorities and an increasingly powerful array of civic groups and real estate interests over Barren Island pollution. In 1898 Governor Frank S. Black issued a toothless proclamation ordering an end to the nuisance. The New York State Board of Health threatened to shut operations down if abatement measures were not implemented. The following year, Senator Joseph Wagner and George W. Doughty, a state assemblyman from Queens, introduced a bill on behalf of the Anti–Barren Island League “to remedy the suffering of a great number of residents whose health was alone impaired, but who also suffered financially . . . because of the stenches coming from Barren Island.” When word came from Albany on April 26, 1899, that the bill had passed—over an attempted block by Mayor Van Wyck—the Rockaways erupted in jubilation. Newly elected governor Theodore Roosevelt, citing “hundreds of letters begging me to sign,” promised to act; “I shall sign the bill,” he declared, “no matter what action the Mayor may take.” But Roosevelt did not sign the bill. In the interregnum, he was convinced to allow the city time to find an alternative to disposal at Barren Island lest it have a public health crisis on its hands. Roosevelt visited the rendering works himself in July 1899, which convinced him afresh that “the Barren Island nuisance must go.” He gave the city a year to find an alternative and instructed Dr. Alvah H. Doty of the Port of New York to explore options. Doty toured Europe searching for a solution and returned convinced that the city needed to build a “public crematory” in which to burn all its trash. He suggested that New York follow Hamburg’s lead, where mixed trash was cremated in a sealed furnace, the smoke condensed in water and the clinkers raked out for use in concrete for foundations and street paving. Doty reasoned that several such plants, odorless and inoffensive, could be built at points along the city’s waterfront. But the deadline came and went; Roosevelt failed to win reelection, and in March 1901 Doughty quietly withdrew his bill altogether, explaining that he hadn’t realized its broad language would put factories out of business all over the city. Around this time, a proposal was made by Brooklyn legislator Jacob D. Remsen to move the Kings County Penitentiary from its aging Crown Heights facility to Barren Island, thereby giving New York a kind of sandy Alcatraz a generation before Rikers became the city’s isle of crime and punishment. Remsen’s bill passed in Albany but was vetoed by Mayor Robert Van Wyck, partly because it was really the brainchild of a real estate concern—the Prospect Park Improvement Company—trying to boost its position by removing an “incubus upon all the property of the neighborhood.” All this time, six scows daily were being towed out from the harbor to dump the city’s garbage at sea, much of it driven right back to shore by wind and waves. Without a better solution in hand, the city reluctantly renewed Sanitary Utilization’s contract, which of course “found itself in a position of such advantage” that it now demanded a much higher fee and a minimum five-year tenure.23

Picnicking among the ruins of the New-York Sanitary Utilization Company plant, 1931. The great chimney can be seen in the background. Photograph by Percy Loomis Sperr. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

And so it was a red-letter day for the long-suffering victims of Barren Island when, on May 20, 1906, the Sanitary Utilization Company’s sixteen-acre complex burned to the ground. The fire began in the digester building, quickly engulfing the entire plant and torching twenty thousand bags of fertilizer. Only a small fireboat, the Seth Low, was on hand to fight the blaze, the plant’s own firefighting equipment having been consumed by the flames. As the fire spread, panic broke out among island residents who feared the wind-whipped blaze would soon burn their homes. A Times correspondent mocked the immigrant families as they rushed to a hodgepodge evacuation flotilla in the bay, piling “pellmell into the boats, carrying all sorts of household articles with them . . . some of them even took their carpets.” In the chaos, several people fell into the water, including a woman “carrying a parrot and a marble clock” who was quickly “dragged out by her husband, who scolded her in Bohemian,” forcing her to let the parrot go and drop the clock off the pier. The parrot was rescued by a boy in a rowboat. The dunked woman was soon back, triumphantly dry now and supervising her husband as he fished for her marble heirloom with a hook and sinker. News of the demise of the great odor engine was—quite literally—a breath of fresh air to those downwind, to whom the plant’s destruction “seemed like a retributive act of divine Providence.” Unfortunately, the Sanitary Utilization Company proved resilient. When the plant burned, the city had no choice but to begin dumping its garbage at sea once again—at least fifty miles out this time (scows would have to round an anchored “stakeboat” before they could release their payload). But fifty miles was not enough—if in fact the tugs were taking the barges that far; for within days, Rockaway residents were howling about the tons of trash fouling the beach at Arverne. Though at least one elected official suggested that Barren Island, cleansed now by fire, be used for a seaside park and convalescent home for the poor, the city had no choice but to implore Sanitary Utilization to rebuild as fast as possible. Within months, a new complex rose phoenix-like from the ashes—bigger, better, and hungrier than ever for Gotham’s trash. And now, city residents could point to where their garbage went; for the plant was anchored on the skyline by a tremendous chimney meant to loft noxious exhalations to some distant place beyond city limits, like Nassau County. At 225 feet, it was one of the tallest structures in the United States at the time, and the loftiest on Long Island until the Williamsburg Savings Bank building was completed in 1929. The belching chimney, visible many miles at sea, was used as a navigation aid by mariners and greeted immigrant eyes long before Lady Liberty’s torch. The massive concrete cylinder was ugly, lacking even an entasis; but it was a beacon of opportunity nonetheless. If the Mother of Exiles welcomed the newcomers, the chimney put them to work; some headed straight to Barren Island after landing and rarely—if ever—set foot on mainland America.24

By the 1900s, Barren Island was home to one of the most polyglot communities on the Eastern Seaboard, with a mostly immigrant population of some fourteen hundred Poles, Italians, African Americans, eastern European Jews, Germans, Irish, and a smattering of native-born Americans. Almost wholly unserved by the city it so vitally cleansed, the island was a throwback to another century. It boasted a hotel and boardinghouses, two churches, a school, dance hall, several bars, a grocery store, butcher, and baker. But Barren Island’s streets were unpaved and flooded by spring tides. There was no permanent police presence on the island until 1897, no fire protection, and—ironically—no trash collection; rubbish was simply tossed in the streets for the pigs and gulls. Fruit was scarce, vegetables meager, and meat (often horse) poor in quality. The well water tasted like fish oil and was later found to be so laden with toxins that residents were forced to subsist on collected rain-water. Flies were ferocious and legion; food left unattended for more than a minute would be black with the insects. There were pig wallows and pools of stagnant water that bred clouds of mosquitoes and caused frequent outbreaks of malaria, typhoid, and diphtheria (which residents fought by wrapping their throats with a compress of salt pork and flannel). Infant mortality on Barren Island was twice the city average. Children rummaging through the island’s great trash heap—known as “The Klondike”—punctured and cut their feet on rusty nails and tin cans. Industrial accidents averaged two a week and were often catastrophic. And yet there was no hospital, infirmary, doctor, or nurse on the island. Worker cottages were terribly overcrowded, with families often taking in a half dozen boarders to make ends meet. The little hovels—many adorned with desperate gardens struggling in the sand—were arrayed along the island’s Main Street, “like a convict settlement,” wrote one unsympathetic observer, “or the outdoor wards of a pesthouse.” Many island residents and most of its children had never been to the mainland, for not until 1905 was there regular ferry service to Canarsie—and even then only in warmer months. Ice in Jamaica Bay made it difficult for ships to reach the settlement in winter, delaying delivery of mail and often leaving residents critically short of food and medicine.25

Barren Island’s catalog of ills made it a target of social reformers. The North American Civic League for Immigrants, founded by crusading progressive Frances A. Kellor, carried out some of its earliest programs there, sending operatives on “friendly visiting” sorties into the homes of immigrant laborers to convey “American social ideals . . . American standards of living and in general an understanding of the principles behind them.” The ministrations were largely altruistic, but not without a political edge. Aiding the isle’s workers in this way might well keep them from being exploited by labor agitators or foreign propagandists; for “wretched housing, overcrowding, extortion and lack of water supply and health protection,” wrote Kellor, then chief investigator for the New York State Department of Labor, “provide the groundwork for rebellion and sedition” (and “Barren Island,” she emphasized, “is a rather strategic point in our coast defenses”). Whatever her ultimate aim, Kellor helped bring a plethora of improvements to Barren Island. An infirmary and milk-and-ice station for mothers was opened under the auspices of the Department of Health, staffed by a trained nurse. A Little Mothers’ League was organized to educate girls about child rearing; evening classes were offered on citizenship and home economics; a playground and ball field were constructed to provide children an alternative to rummaging in the dump; youth clubs were launched to counter the pull of saloons. But even before these, Barren Island was not without its richness and beauty. Life blossomed with weed-like vigor amidst the sand and garbage, and nowhere more fully so than at the handsome gray-and-white Public School 120, erected in 1901 and alive with “bright, active little people, in love with nature and the sea by which they are surrounded.” And life flourished there in ways scarcely imaginable at the time elsewhere in New York. Not only was Barren Island one of the city’s most ethnically diverse communities; it was among the earliest to be racially integrated. A 1901 Brooklyn Eagle article about its new school was accompanied by a photograph—captioned “Two of the Scholars”—that epitomized racial optimism in America. In it, two adorable kindergarten girls—one black, the other white—beam for the camera with their arms around each other. Racism spoiled the Eagle piece nonetheless, as its author related with salacious censure how “young white women frequently choose negro partners” at the weekly Barren Island dance—and how “the children look on and drink in . . . the seamy side of Barren Island society.” Blacks and whites also engaged in collective action, striking against the New-York Sanitary Utilization Company plant in April 1913. Press and engine room operators walked off the job when company officials balked at a requested pay raise, and were soon joined by most of the plant’s “500 Polacks and fifty negroes.” The facility remained closed for nearly two weeks, until the company brought in two hundred strikebreakers on May 16. The day shift went forward without incident, but it was a Friday—payday—and there was, yet again, nothing for the strikers. Enraged by the scabs and “inflamed by Barren Island liquor,” they attacked the arriving night-shift workers, firing revolvers, hurling bricks, and clubbing and kicking them. The seven policemen on-site at the time were quickly overwhelmed. Dozens of workers were injured, and one striker shot by the time the riot was quelled by police called in from the mainland.26

Catholic church, Barren Island, 1931. Photograph by Percy Loomis Sperr. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

The rubbish of the modern world came to Barren Island by the scow-load, while its wonders arrived only in fits of happenstance. It was a brutally cold winter that brought the first motor vehicle to the remote community, nearly a decade before Barren Island was finally joined to the mainland by road. In January 1918 oysterman Harold Rohde drove a one-ton Maxwell truck over miles of ice to reach the clam cribs he stored on the island. There he was greeted by “droves of wild-eyed children” who begged for a ride and “persisted in hooking their sleds on behind, riding all the way to Canarsie shore.” Rohde’s Maxwell was burdened with twenty-three hundred pounds of clams on the return trip, making it a wonder indeed that he did not break through the weak sea ice and commit sledders and bivalves alike to the bay bottom. Six months later, Barren Island was blessed by the arrival of another female redeemer, one who brought more joy to the long-scorned isle than a diamond ring pulled from the trash. Jane F. Shaw, a farm girl raised on the edge of the Adirondacks, was already an experienced teacher when the Board of Education tapped her to head P.S. 120. She had taught for many years in city schools—most recently near the Henry Street Settlement in lower Manhattan. To Shaw, Barren Island was anything but. She quickly took command of her new station, staying on-site all week and returning for the weekend to the home she shared in Williamsburg with two sisters—both also educators. Within months of her arrival Barren Island began showing signs of metamorphosis. Well aware that children with chaotic home lives were in no condition to learn, Shaw extended her reach well beyond the classroom, making it her business “not only to teach the children . . . but to go into their homes and help their parents.” She had the Red Cross send milk daily during the great influenza pandemic, her boys meeting the police boat at the dock and pushing carts loaded with bottles through heavy sand to the homes of the sick. Trained by a navy physician stationed in Jamaica Bay, Shaw became the island’s de facto doctor. Disease became rare, and the rowdiness and disorder long associated with Barren Island vanished as saloons were closed by Prohibition. At the end of the year Shaw would invite her eighth-grade class to tea at her Marcy Avenue home. Many of Shaw’s pupils went on to high school, enduring long mainland commutes by foot, trolley, and subway. A decade later, Barren Island had been transformed from the butt of jokes into a model town, the “richest spot on earth,” Shaw called it, with a post office and a stigma-free new name: South Flatlands. When the city balked at building a plank road in from Flatbush Avenue, Shaw organized the islanders to construct one themselves. She taught cooking classes in her kitchen, encouraged residents to grow vegetables and raise chickens, ducks, and cows, and turned P.S. 120 into a community center—persuading the Board of Education to outfit it with a radio and movie projector and using her own money to buy a piano.27

The New-York Sanitary Utilization Company finally closed its Barren Island plant in 1920, demolishing all but the great chimney a year later. With hundreds of jobs now gone, the island’s population plunged. And yet life carried on nearly two decades more, clinging to this spit of sand as the world swirled in change all around it. Flatbush Avenue was extended across Barren Island in 1923, ending the island’s isolation and filling many of the salt meadows and creeks with sand dredged from Rockaway channel. A small airstrip was constructed in 1927 by an enterprising young pilot named Paul Rizzo; four years later, New York City would open at Barren Island its first municipal airport (see chapter 12). Then, in March 1936, agents of the city’s powerful and ambitious new parks commissioner, Robert Moses, trudged through the sand to deliver eviction notices to the island’s four hundred-odd remaining residents, some of whom had lived on Barren Island for forty years. Now they had fourteen days to pack up and leave, to make way for what was planned to be the largest urban playground in the world. “Lady Jane” Shaw knew every one of these men, women, and children; she had attended their every christening, wedding, and funeral; she was their “counselor, dictator, friend and champion.” And now she rendered one last service—imploring Moses and other city officials to give her benighted Barren Islanders a reprieve long enough to see her last class graduate. In a letter to Brooklyn borough president Raymond V. Ingersoll, Shaw told of the panic and plight among her flock, invoking the “Exile of the Acadians” popularized by Longfellow’s epic poem Evangeline. Moved by the plea, Moses granted her request, postponing the deadline to June 30, graduation day. The old school was boarded up the very next morning. The symbolic end of Barren Island came a year later, on March 20, 1937, when the great smokestack of the Sanitary Utilization plant was toppled by dynamite. However handy a landmark for ships and fishermen, it had become a menace to aviators at Floyd Bennett Field. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, the short-lived airport’s biggest booster, set off the charge personally in front of an enormous crowd of spectators. There was a boom and a wisp of smoke, followed by silence. The crowd murmured with confusion. And then, with a gathering roar, the old stack leaned into a fall, crashing onto the sand like a mighty tree trunk. It had been hoped that the chimney’s four platinum-plated lightning arrestors—said to be worth thousands of dollars—might be a last gift to the island’s Depression-poor residents; but the rods had been removed long before. Jane Shaw was not among those gathered; for the “guardian angel of Barren Island” had bid farewell to her beloved isle three years before, still mourning the loss of the community she loved.28

End of an island, November 1924: sand slurry being pumped from Jamaica Bay to extend Flatbush Avenue from Avenue U to Rockaway Inlet, joining Barren Island to the rest of Brooklyn. Edgar E. Rutter photograph collection, Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Public School 120, Barren Island, 1931, Board of Education of the City of New York. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.