CHAPTER 12

GRAND CENTRAL

OF THE AIR

Not all of Jamaica Bay was as resistant to human will as Gerritsen Creek. At Barren Island just a mile to the east lay an estuarine landscape subjected to seventy-five years of abuse at the hand of man only to be obliterated by one of the largest landfill operations in city history. Even as plans to make the bay a great world harbor fell apart, Barren Island was chosen to become a port of a different sort—for vessels not of the high seas, but of the air. Here on the southernmost edge of the city, New York would build its first municipal airport. Just as the impending opening of the Panama Canal spurred a feverish campaign to maintain the city’s primacy as a seaport, it was an event of global significance that helped kick the Big Apple into the air age—Charles Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in May 1927. Lindbergh’s flight was an American triumph, but one that vexed many New Yorkers. This was because Lucky Lindy’s so-called New York–Paris flight into history was launched not from the mighty metropolis, but from an airfield on Long Island. It should more accurately have been called the Garden City–Paris flight. Lindbergh had nothing against Gotham, of course; it’s just that there was no place in New York City proper to take off from. No place dry, that is. The very first crossing of the Atlantic by an aircraft—nearly a decade before Lindbergh’s—set out from the waters of Jamaica Bay in the spring of 1919 (and included a young naval officer named Richard E. Byrd, whom we shall meet later). This was no stirring “lone eagle” adventure, but a massive naval expedition involving several planes, fifty ships, and hundreds of men. Three Curtiss NC flying boats departed Naval Air Station Rockaway (about where Jacob Riis Park is today) on May 8, making stops on Cape Cod, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland before heading out over the Atlantic—guided by not only navigational charts but a chain of twenty-two well-lighted navy warships riding at anchor all along the flight path. Only one craft, NC-4, made it to the Azores, and from there to Lisbon and—eventually—Plymouth, England, where the flying boat was met with tremendous fanfare. The aerial crossing was cheered by the London press as “the opening achievement in a new era of transpontine travel.” The NC-4’s six-man crew, commanded by Albert Cushing Read, was feted on both sides of the Atlantic—and promptly forgotten once Lindbergh made his solo flight.1

But the future of aviation was in airports, not flying boats. And that America’s largest, most powerful metropolis had no airport to call its own in 1927 was an embarrassment to citizens and civic leaders alike. This was no longer the rude dawn of aviation, when fliers like Kay Stinson and Cal Rodgers could trundle stick-built craft over pasture and sand (their favored field at the Sheepshead Bay Speedway was itself gone, in any case). There were more than four thousand federally sanctioned airfields in the United States by now, and yet none within the limits of the nation’s greatest city. Despite Gotham’s titanic power, complained Brooklyn, “airplane landings must now be made at isolated aviation fields far out from the city on Long Island and the New Jersey meadows.” Clearly something had to be done. Even before the Spirit of St. Louis had rolled to a stop at Le Bourget, New Yorkers had begun clamoring for an airfield worthy of their city. And in the weeks and months after Lindbergh’s flight, dozens of sites all over town were proposed for the inaugural airfield, ranging in fitness from the ideal to perfectly absurd. Jamaica Bay was consistently in the press for a number of possible sites—all, ironically, on land that was to be created as part of the World Harbor scheme. Governors Island was an early contender, favored by several prominent aviators. It certainly had pedigree: the island had been the launch point for the first airplane flights in New York City—Wilbur Wright’s jaunts around the Statue of Liberty and Grant’s Tomb during the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909. In a fit of generosity, the Flatbush Chamber of Commerce even suggested “landing places” in each of the boroughs, lorded over—of course—by “one large and completely equipped field” in Brooklyn. The Regional Plan Association suggested no fewer than thirty-two airports for the New York metropolitan area!2

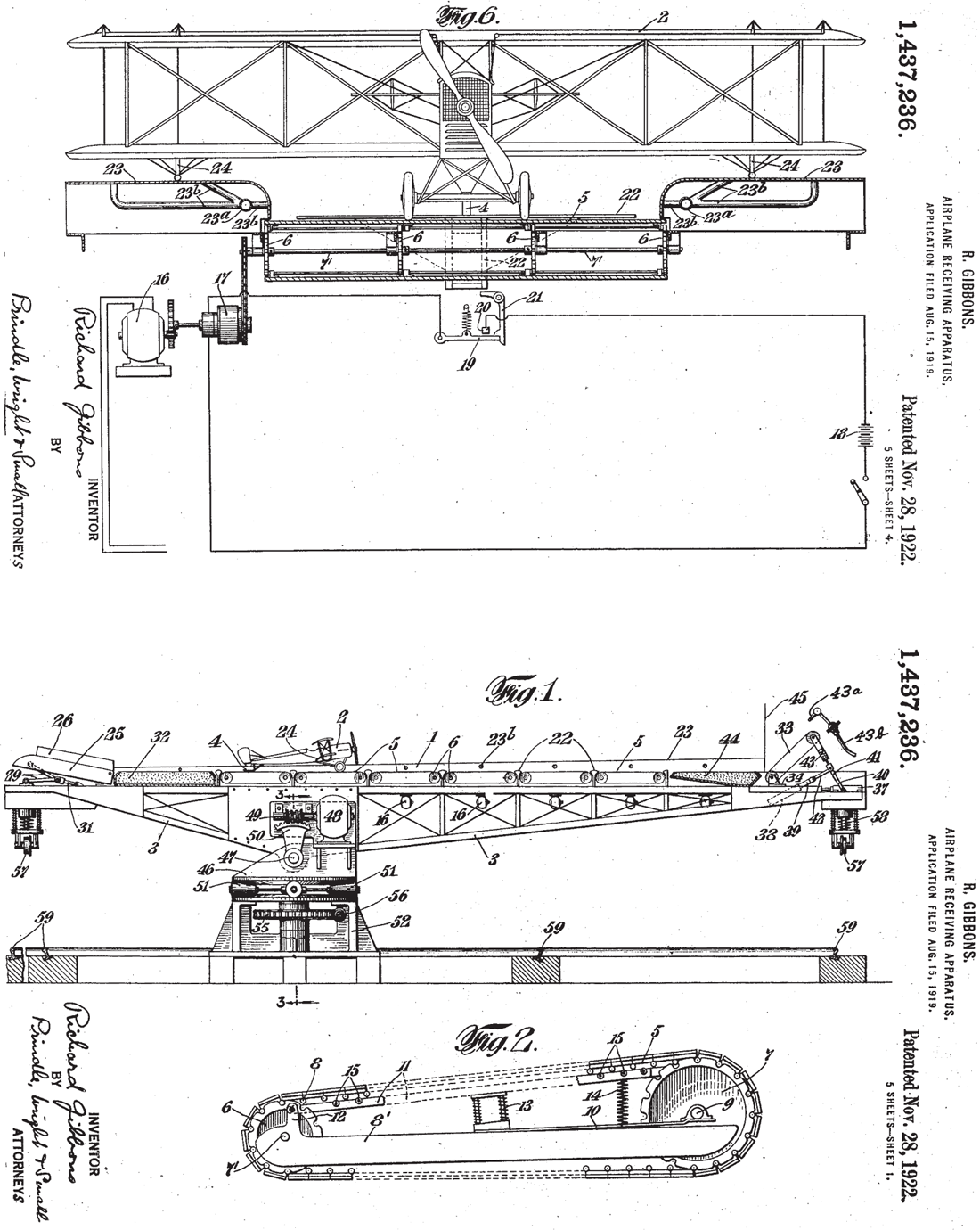

Brooklyn’s boosters were loud and effective campaigners for an airfield on their turf. Aviation was all bright and soaring promise, offering redemption of a sort from tenement grit and industrial grime. Here was a chance for Brooklyn to step boldly out from Manhattan’s shadow and stake a claim on the future itself. The borough certainly had the land for a modern airfield and could make a lot more at its marshy margins. The ever-ambitious Marine Park Civic Association was first in line, launching a campaign for “Lindbergh Field” on that perennial field of dreams, Marine Park (the “playground” portion between Fillmore Avenue and Avenue U, erstwhile site of Knute Rockne stadium). The old Dreamland site in Coney Island was proposed, vacant ever since a catastrophic 1911 fire. A 116-acre parcel on Gowanus Bay was suggested by star Curtiss airplane designer Harvey C. Mummert, while a “Bay Ridge Airport” was proposed in the Narrows off Shore Road, set on an enormous island of fill stretching from Ninety-Second Street north past the Brooklyn Army Terminal. A similar proposal was made for Gravesend Bay, with runways laid out on a trapezoid of new land between Sea Gate and Bath Beach. Others suggested Stilwell Basin in Coney Island (site of the New York City Transit rail yards) and the east end of Manhattan Beach, today the campus of Kingsborough Community College. But not all Brooklyn airport boosters had their eyes on terra firma: Brooklyn manufacturer Richard Gibbons looked instead to the city’s rooftops, proposing that landing accommodations be fixed atop buildings using air rights purchased from owners. He designed an extraordinary articulated steel platform—two hundred feet long and sixty feet wide—that could be rotated into wind and pitched up or down to help launch or land a plane. The deck was equipped with a reversible fan system to “blow away snow in Winter, or as a source of suction to keep a landing plane from bounding after it hits the runway.” Gibbons had filed a patent for this “Airplane Receiving Apparatus” years before—in August 1919—and fabricated a scale model at his Columbia Street factory in Red Hook (itself equipped with a “platform for aeros” on the roof). Nine years later he was still at it, aided by a team of engineers (including Harvey Mummert) and testing a prototype in wind tunnels at New York University’s short-lived Guggenheim School of Aeronautics.3

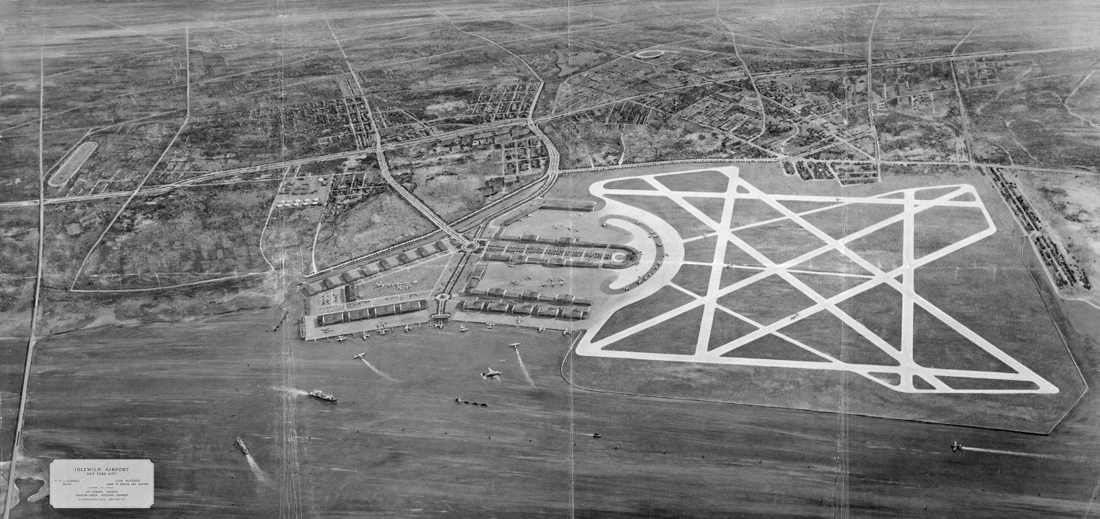

Of course, choosing a site for New York City’s first airport—a vital piece of urban infrastructure—could not be left up to boosters and visionaries, let alone armchair inventors. Even before Lindbergh’s flight, the Board of Estimate had asked city engineer Arthur S. Tuttle to evaluate promising airport sites in New York. Tuttle was a highly respected figure in the city, having helped design Brooklyn’s waterworks years earlier. He urged officials to think well ahead of present needs, warning that most of the best sites, including Marine Park, were already hemmed in by residential development and offered little capacity for future growth. “A commercial flying field in a city like New York,” he cautioned, “is certain to become the most crowded aviation center in the whole United States.” Tuttle determined that the most advantageous site in the long run was East Island in Jamaica Bay, the artificial island that was to be created out of the JoCo and Silver Hole marshes as part of the Great Port plan. Tuttle’s airport, laid out as a 640-acre square, would have been located just off the southern tip of runway 4L-22R at today’s John F. Kennedy Airport. But Mayor Walker, rumored to fear flying, was slow to make a municipal airport a priority of his colorfully corrupt administration. Secretary of commerce Herbert Hoover, convinced that a modern airfield in New York City was vital to the nation’s economic health, made it a federal case. He appointed a blue-ribbon board to determine the best site—the Fact-Finding Committee on Suitable Airport Facilities for the New York Metropolitan District. Its location subcommittee, chaired by philanthropist-aviator Harry F. Guggenheim, cast a wide net, soliciting input from business, professional, and civic groups and the public at large. In all, some seventy-two sites across the region were considered. The committee’s findings were publicized just before Christmas at a Hotel Astor luncheon, to which Mayor Walker arrived predictably late. Hoover’s team divided the city into six “localities,” recommending specific airport sites for each. Unobstructed flight paths, availability and cost of land, favorable meteorology, road and rail access, and expansion potential were among the many factors considered. Though it endorsed a total of ten locations (six first- and four second-choice sites), the committee clearly favored building New York’s municipal airport in Queens—on still-rural land in Juniper Valley that was nonetheless well served by public transit (the Myrtle Avenue Elevated to the south, Long Island Rail Road to the north). It also commended the city of Newark’s recent decision to construct an airfield of its own on Newark Bay—eventually the cause of much grief for partisans of Brooklyn, as we shall see.4

Richard Gibbons, illustration for an “Airplane Receiving Apparatus,” 1919. United States Patent Office.

But the Hoover committee was advisory only and had no teeth to force its findings; it was up to the Board of Estimate and the mayor’s office to make the final decision. Mayor Walker, ambivalent about the whole flying-field matter from the start, refused to set foot in an airplane and ordered his loyal assistant, Charles F. Kerrigan, to look over the sites by air. Ultimately, the decision came down to cost. Building an airport at all but two of the Hoover sites would require purchasing vast holdings from private owners or the federal government—a very expensive proposition. Jamaica Bay, already mostly in municipal hands, moved two sites—East Island and Barren Island—into the pole position. Recall that in 1927 the Great Port of Jamaica Bay was not yet cold in the grave. To make an airport out of either of these wet spots would mean a tremendous amount of fill. Dredging channels for the long-envisioned port was the obvious source. The skyport could help make the seaport, thus killing two infrastructural birds with the proverbial single stone (or clump of sand). Linkage between the schemes also helps explain why responsibility for building and operating the airport was handed not to some glamorous new ministry of aviation, but to the plodding, old Department of Docks—the very agency that had long sought to make Jamaica Bay the greatest port on the seven seas. But just as Jamaica Bay made little sense for a deepwater harbor, it was also far from ideal for an airport. Both locations were a long haul from lower Manhattan, far from rail or subway connections. East Island did not even yet exist and—once created—would require bridging a thousand-foot channel to join it to the city.5

Barren Island was hardly close to town either, but at least it was above water. There, some three hundred acres of level city-owned land were ready to go. Another five hundred could easily be filled, and all of it was already joined to the city by the recent extension of Flatbush Avenue. Kerrigan’s air tour had convinced him that Barren Island was indeed the best site, and he pointed out that an airport there would terminate the new “bee-line automobile route” that ran through the heart of Brooklyn along Flatbush Avenue, connecting to Canal Street over the Manhattan Bridge and the rest of America via the newly opened Holland Tunnel. It was also not beyond the reach of rail and rapid transit; trolleys ran to Avenue U, and as early as 1910 plans had been made to extend the Utica Avenue subway to Flatbush Avenue and Jamaica Bay as part of the port project, while the Long Island Rail Road began looking at a Barren Island spur from its New York Connecting Railroad. And as was not the case at any of the other contending sites, airplanes were already taking off and landing at Barren Island. A twenty-three-year-old self-taught Brooklyn flyer named Paul Rizzo had begun flying an Epps monoplane from a sandy strip of private land along Flatbush Avenue in 1928. He named it, ambitiously, Barren Island Airport. Rizzo gave airplane rides and took news photographers up over the city. Within a couple of years he had a stable of six aircraft, including a Waco 10 biplane that pioneer wing-walker Ova Kinney often performed on. He was soon joined by a competitor, Charles Krohn, who used a shorter parallel runway and often had to “borrow” a bit of Rizzo’s at the last minute to get airborne (leading to a “spite fence” and a lawsuit). On February 2, 1928, the Board of Estimate held a final public hearing on the airport matter. Proponents of the various sites pressed their cases. At one point the room was darkened, and aerial footage of the contending sites was screened. When the camera panned briefly to a clutch of Manhattan skyscrapers, the mayor cackled, “Is that a landing field?” To Brooklyn boosters, the airport was no joke. The borough desperately wanted the city’s first municipal airfield. The powerful Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce was on hand, along with representatives from booming Flatbush and Flatlands. They were joined by a flotilla of ninety-eight community groups from every corner of the borough. By meeting’s end the prized bird was in hand: Barren Island was chosen, by a unanimous vote of the Board of Estimate, to be the city’s first official airfield. Brooklynites danced in the street. The Eagle joyously proclaimed that the new airport would shape the future of New York City, much the way the Brooklyn Bridge had fifty years earlier. Lord Manahatta would now have to come to lowly Brooklyn to see the future—and to Barren Island, no less! The long-suffering isle of bone broth and stink, the Hades of horsedom, dumped on literally by all of Gotham—Barren Island would now be no less than “New York City’s Grand Central of the Air.”6

Paul Rizzo with his Waco 220 biplane at Floyd Bennett Field, c. 1931. Rizzo laid out the first earthen runway at what would later become New York City’s first municipal airport. Rudy Arnold Photo Collection, Archives Division, National Air and Space Museum.

The man in charge of this metamorphosis was Clarence D. Chamberlin, appointed the city’s aeronautic engineer in June 1928. Chamberlin, largely forgotten today, was one of the most celebrated aviators in the world at the time. He was every bit as skilled a pilot as Charles Lindbergh, who beat him to Paris for the Orteig Prize the year before. Chamberlin held the world flight endurance record—a fifty-one-hour, forty-one-hundred-mile schlep back and forth over Long Island to train himself for the transatlantic flight—and would very likely have beat Lindbergh were it not for the meddling of his airplane’s owner, wealthy Brooklyn scrap-metal man Charles A. Levine. Shortly before Chamberlin and his trusted copilot, Lloyd W. Bertaud, were to take off for Paris, Levine attempted to bump Bertaud and copilot the Miss Columbia himself. Bertaud sued; an injunction was issued and the aircraft grounded under police guard at Roosevelt Field. By the time Levine got the order lifted, Lindbergh was well on his way toward Paris and the history books. Chamberlin and Levine finally got airborne two weeks later, landing just short of Berlin after sixty hours of flying in rather grim silence (the two were barely on speaking terms). Chamberlin thus gained the sapless honor of being second to fly across the Atlantic, but the first to fly a passenger—an oddly appropriate distinction for a man chosen to build New York’s inaugural civilian airfield. Airport planning and design was a nascent field in 1928. Chamberlin toured Europe to learn what he could from its state-of-the-art airports—Le Bourget in Paris, Berlin’s Templehof, and Croydon in South London, first in the world to use air traffic control. Working with a team of Dock Department engineers, Chamberlin drafted plans for the new flying field and personally tested potential sites for its floatplane landing base. He requested $2.75 million to build the airport, to include a series of hangars along Flatbush Avenue, a central administration building with control tower, offices, and passenger hall, two concrete runways—one thirty-one hundred feet and the other four thousand feet long—even grandstands to accommodate up to ten thousand air show spectators.7

Clarence D. Chamberlin, c. 1927. Leslie Jones Collection, Boston Public Library.

Sand slurry being pumped from Rockaway Inlet to create Floyd Bennett Field. This photo was taken at the commencement of work on the airfield in June 1928. Cora Bennett, Floyd Bennett’s widow, is in group on right. Vehicles in background are on Flatbush Avenue. Henry Meyer Collection, Othmar Library, Brooklyn Historical Society.

Even before Chamberlin’s plans were finalized, land making for the airport had begun at Barren Island. Preparing a level platform for the airfield required pumping a mammoth quantity of sand—from Mill Basin and the main shipping channel in Jamaica Bay—to fill the creeks and marsh and raise the ground sixteen feet above mean high tide. By Christmas of 1929, nearly four hundred acres of new land had been made, then covered with clay and topsoil. In a rare and early instance of concern for the natural environment, the New York Times ran an article on how construction of the airfield was destroying one of the last great havens on the Atlantic Seaboard for the ancient horseshoe crab. As the dredges pumped sand slurry into the marshes and creeks, “burying beyond escape thousands of little ones . . . hiding in the soft mud,” the crabs began an extraordinary mass exodus from Barren Island, moving across the bay bottom in the thousands “like an army of miniature wartime tanks.” Atop the new land were stretched two runways, set at right angles and fifty feet wide, doubled to one hundred feet even before the airport opened in a bid for the coveted “A1A” airport rating from the Department of Commerce. The concrete had hardly cured when the first scheduled airline began operations—an hourly New York–Washington run launched in August 1930 with a fleet of three-engined, ten-passenger Stinson Airliners. The Administration Building, which included the airport’s control tower, was, oddly, the last major building to go up. Designed in the Georgian revival style popular at the time for institutional buildings, it included a telegraph office, barbershop, newsstand, press and radio rooms, a US Weather Bureau chart room, a dormitory for pilots, and a terraced lounge and restaurant for two hundred patrons. The building was erected by the Longacre Engineering and Construction Company of New York, whose earlier work included Chicago’s famed Apollo Theater, the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, and the Ford Motor Company headquarters at Broadway and Fifty-Fourth Street, designed by Albert Kahn. But the Brooklyn airport job was peanuts next to Longacre’s biggest project at the time—in the Soviet Union, of all places, where it had won a $25 million contract to erect a series of modern apartment blocks and school buildings around Moscow. Crowds of spellbound Muscovites gathered to watch as Longacre crews broke ground with American steam shovels, tractors, and other equipment. The new airport’s improbable Soviet connection curiously foreshadowed a controversy some years later during the Depression involving murals commissioned by the Federal Art Project of the WPA for the Administration Building passenger hall. The Armenian émigré Arshile Gorky had originally been contacted to execute the artwork, and a preparatory gouache for his highly abstract mural—based on collages of photographs taken at the airfield by Wyatt Davis—was exhibited at the Federal Art Gallery in December 1935.8

But for reasons unclear, Gorky’s work was redirected to Newark Airport, and the Brooklyn commission handed instead to August Henkel and his assistant Eugene Chodorow. The pair labored for three years on the murals—each six feet tall and thirty feet long—which were draped from the second-floor balcony above the lobby. But some saw dark and troubling things on Henkel’s canvases: a figure thought to bear a uncanny resemblance to Josef Stalin (it was in fact the French parachutist Franz Reichelt); a Soviet airplane that had made a record-breaking flight from Moscow to California (it was actually an American Vultee); a red star on a navy hangar (that one “slipped by,” Henkel admitted). The Wright brothers were depicted in Soviet peasant garb, according to some. Joseph Rosmarin, a local flight instructor who had flown against Franco’s forces during the Spanish Civil War, was painted in nearby. Jessie A. Chamberlin of the Women’s International Association of Aeronautics called the murals “outrageous things.” “Looks like Russian stuff,” grumbled another. The WPA overlord for New York City, Colonel Brehon B. Somervell, came to look and immediately ordered Henkel’s murals yanked down and destroyed (three were burned; the fourth was spared but remains lost). When Henkel later refused to sign a mandatory affidavit stating that he was not a Communist or a Nazi, Somervell dismissed him from the Federal Art Project. Henkel fired back with a lawsuit, claiming defamation of character and asserting that he refused to sign only because the demand was a violation of his constitutional rights as an American; “My politics are my own affair,” he angrily asserted, “and I do not need to disclose them to any Government agency any more than I would need to tell how I vote in an election.” Henkel freely admitted he had leftist sympathies; he had twice campaigned for elected office in Queens as a Socialist candidate. Matters got worse when the New York Times revealed that Henkel had once been arrested for his part in an ill-considered ceremony at Bouck White’s Church of the Social Revolution, in which the flags of nations were burned in a gesture of universal brotherhood. Henkel burned the American flag, an act that landed him a thirty-day sentence in the city workhouse. Now he received death threats and asked for police protection at his Queens Village home. Rockwell Kent was one of the many artists who came to Henkel’s defense, rebuking Somervell’s “irresponsible dictatorship” and “wanton destruction of the people’s property.”9

Federal Art Project artists August Henkel and Eugene Chodorow working on their doomed murals for the Floyd Bennett Field Administration Building, 1939. Photograph by Sidney M. Friend. Federal Art Project, Photographic Division Collection, Archives of American Art.

Floyd Bennett in April 1925, about a year before his historic flight to the North Pole with Richard E. Byrd. US Naval History and Heritage Command.

New York City’s first municipal airfield would be named for pioneering naval aviator Floyd Bennett. Raised on a hardscrabble farm outside Warrensburg, New York, Bennett picked blackberries as a boy, worked in lumber camps, and trained as an automobile mechanic before opening his own garage in Ticonderoga, New York. With war clouds massing over Europe, Bennett enlisted in the navy at Burlington, Vermont, initially training as a landsman mechanic. He later learned to pilot a Curtiss flying boat at the new air station in Pensacola, Florida, and graduated with the navy’s very first class of aviators. In 1925 he was selected by Richard E. Byrd to join a naval aviation detachment with the MacMillan Polar Expedition. Byrd and Bennett were an unlikely pair. A highborn Virginian whose forebears founded the city of Richmond, Byrd was a graduate of the United States Naval Academy with a penchant for bravado. The taciturn Bennett, raised in Adirondack poverty with only an eighth-grade education, was the perfect foil to the impetuous Southerner. Weather in Greenland limited flying on the MacMillan expedition, and its real triumph was demonstrating the utility of shortwave radio for long-range communication (Eugene MacDonald, a naval reservist and founder of Zenith, helped lead the trip). The following year, Byrd organized a polar journey of his own, with backing from Edsel Ford, John D. Rockefeller, and Vincent Astor. A master at self-promotion, he also negotiated lucrative media and publicity contracts, including with Pathé News. He tapped Bennett to fly the expedition’s trimotor Fokker F-VII, the Josephine Ford, named for Henry Ford’s only granddaughter. The airplane would catapult both men to world fame, though not without controversy.10

The Byrd Expedition got under way from Brooklyn, where—on April 5, 1926—an enthusiastic crowd of well-wishers gathered at the Navy Yard to see the USS Chantier off. The Josephine Ford and a smaller chase plane had been disassembled and loaded aboard the repurposed warship, which set sail for Spitzbergen, Norway, shortly after lunch (escorted through the Narrows by Astor’s steam yacht, Nourmahal). On board was enough coal for a fifteen-thousand-mile journey, six thousand gallons of gasoline for the airplanes, $25,000 worth of navigation instruments, and several tons of expedition supplies—including bulky fur flying parkas each valued at more than $1,000. Fifty men crewed the ship, nearly all volunteers, backed by enough food stores to sustain them for six months at sea. They reached Spitzbergen three weeks later, where the Fokker was reassembled and readied for flight to the North Pole. Just after midnight on May 9—the plane’s wooden skis performed better when the ice was frozen hard—Bennett gunned the Fokker’s three Wright Whirlwind motors, and the Josephine Ford rumbled off into the arctic dark. With Byrd navigating and Bennett at the ship’s controls, the men made their way over the ice, communicating against the roar of the motors by hand signals and passed notes. At two minutes after nine o’clock that morning, the men crossed the pole, or very near to it. They limped back to Spitzbergen on two engines, returning exhausted but triumphant some sixteen hours after their departure. Bennett demonstrated extraordinary courage, piloting in conditions that would challenge flyers even today. With an unheated cabin, temperatures plunged to –50°F, making the simplest tasks a torturous challenge. Equally remarkable was Byrd’s navigating the tiny craft over six hundred miles of trackless ice. The men returned to Brooklyn as national heroes, feted with that gold standard of American hero worship—a ticker-tape parade down Broadway.11

For Bennett, it was the high point of a very short life. In the triumphal aftermath of the polar flight, he and Byrd planned to cross the Atlantic in a bid for the Orteig Prize. Department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker, who had a keen interest in aviation, provided financial backing. But the first flight of their custom-built Fokker F-VII ended badly when the test pilot—the plane’s designer, Anthony G. Fokker—crashed the ship in a botched landing. Bennett, a passenger at the time, was seriously injured and never fully recovered. A year later he volunteered to fly an exceedingly hazardous route to bring aid to the German-Irish crew of the Bremen, stranded on Greenly Island, Quebec, after becoming the first airplane to cross the Atlantic from east to west. Despite already suffering a fever, he and copilot Bernt Balchen departed from Detroit in a Ford Trimotor. At a supply stop near Murray Bay, he finally yielded the yoke. Balchen pushed on to the Bremen; Bennett, now gravely ill with pneumonia, was rushed back to Quebec. Charles Lindbergh flew through a snowstorm to deliver a special serum from New York. But it was too late: the arctic flyer succumbed on April 28, 1928. He was all of thirty-eight.12 Byrd, who was paraded up Broadway a second time in July 1927 for a transatlantic flight with Balchen, would go on to make several more polar expeditions in coming years, all to the Antarctic. The most celebrated was launched just months after Bennett’s death, this time with four ships, three airplanes, nearly a hundred dogs, and 650 tons of supplies. The little fleet was led by the City of New York, a repurposed nineteenth-century Norwegian barquentine sealer formerly known as the Samson and long suspected—incorrectly—of being the “mystery ship” that failed to aid the stricken RMS Titanic in 1912 because it had been hunting illegally off the Grand Banks. Byrd was a Jazz Age blogger; from his expedition base on the Ross Ice Shelf—named “Little America”—he broadcast radio updates to eager fans tuning in across the United States. On November 29, he and Balchen became the first men to fly over the South Pole—in a Ford Trimotor named the Floyd Bennett. Returning to New York on June 19, 1930, Byrd was given yet another hero’s welcome, with an honorary degree from New York University and an unprecedented (and still unmatched) third ticker-tape parade up Broadway. The following week he presided over a ceremony at Barren Island in which the city’s inaugural airfield was named for “the realest man I ever knew”—a man who quite literally propelled Admiral Byrd to world fame. Throngs lined the route of Byrd’s motorcade from the Manhattan Bridge to Borough Hall and all along Flatbush Avenue to the airfield, including some 500,000 children given the day off from school for “Brooklyn Aviation Day.”13

Floyd Bennett Field in 1933, showing original runway layout. The chimney of the old New-York Sanitary Utilization Company plant at Barren Island is in upper right; Dead Horse Bay to lower right. Photograph by Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc. Collection of the author.

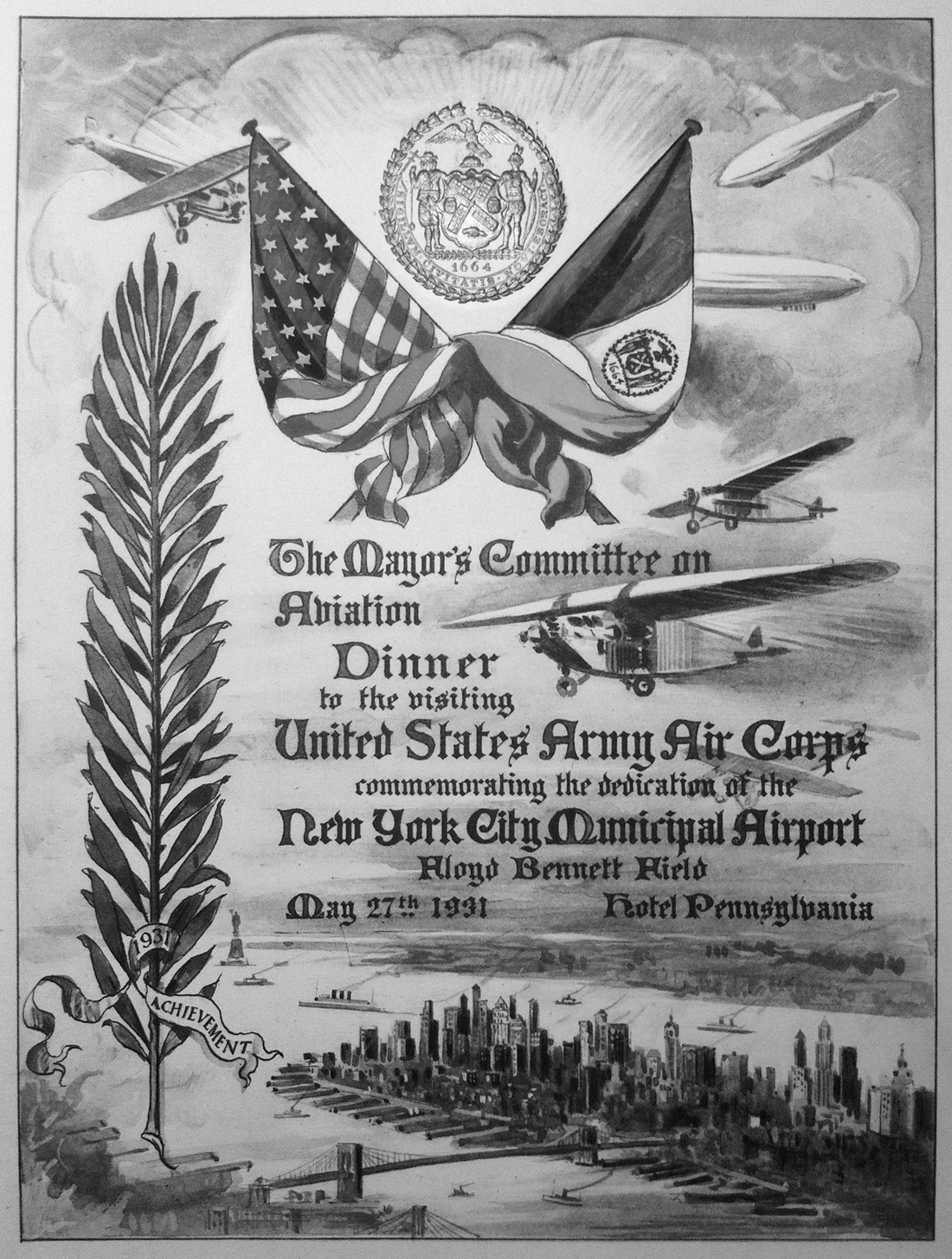

Mayor’s Committee on Aviation invitation to banquet celebrating the dedication of Gotham’s first municipal airport, May 27, 1931. Henry Meyer Collection, Othmar Library, Brooklyn Historical Society.

The official opening of Floyd Bennett Field, one year later, was marked by perhaps the greatest spectacle ever staged over New York City. At about 5:45 a.m. on wet and blustery May 23, 1931, a drone of distant motors was heard coming from the north. Tiny specks soon peppered the clouds, as a massive “aerial armada”—the entire First Air Division of the US Army Air Corps—made its way down the Hudson. Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers assembled in parks and on piers and tenement rooftops to see the mighty show—“the greatest fleet of fighting airplanes,” reported the Times, “ever gathered under a single command.” At the Battery alone, some fifty thousand people craned their necks to see the mighty flying force. First came a lumbering vanguard of bombers, led by a faster plane trailing a plume of white smoke. As these disappeared over the Narrows, many assumed that the show was over. But then the air slowly filled again with the choral roar of radial engines as an extraordinary formation of nearly six hundred aircraft—the largest ever assembled over North America—motored past the city. The planes came in wave after wave for what seemed an eternity—nimble Curtiss pursuit planes, tiny scout planes and observation craft, muscular Boeing fighters, hulking Keystone bombers that skimmed low over the water. Their yellow wings were jewel-like against the mercurial sky, glinting as “long bars of light from the shrouded sun broke through for a minute or so.” The Air Corps fleet, drawn from units across the country and crewed by fourteen hundred men, had been launched in phases from several airfields on Long Island, flying across the Sound to Ridgefield, Connecticut, before turning west and staging over Ossining, New York, in a great rotating pinwheel. Once the last planes joined in, groups began peeling off for the run down the Hudson, stacked at interval altitudes “like broad stairs,” wrote the Times, to save “those in the rear from the propeller wash of comrades just ahead.” The entire formation stretched twenty miles long and took a full twenty-two minutes to pass a given point along the route; Charles Lindbergh brought up the rear with the 110th Observation Squadron, his old unit of the Missouri National Guard. From the Battery—where a mock battle was called off owing to squalls and the low ceiling—the planes flew through the Narrows, around Coney Island, and out to sea. The pilots then turned sharply north to make a long low pass over Floyd Bennett Field, roaring “like a swarm of insects out of the mist and clouds over the sea.” Remarkably, there was only one mishap the entire day, when an observation plane from the 104th Flying Group was forced to ditch in the Narrows near Owl’s Head Park; the pilot and his passenger—Daily News photographer E. J. Dowling—were unhurt and quickly rescued.14

Not everyone was pleased with the mammoth war game, which cost taxpayers a cool $2 million. Pacifists held maneuvers of their own that day, staging a “Peace Parade” and a series of well-attended lectures at the Battery, where members gathered thousands of petition signatures for the advancement of world peace. Writing in the Militant, weekly organ of the Communist League of America, George Clarke warned that the world was heading fast toward another war, and that the airplane would be its chief instrument—not the “obsolete and antiquated battleships” haggled over in disarmament conferences. He blasted the air show as capitalist warmongering in the form of bread-and-circus entertainment, and accused even the pacifists of collusion—offering little more than “soft and soothing music that lulls the working class into a state of drowsy security.” Of course, the armada was emphatically meant to signal to the world America’s commitment to building a first-rate air force, even if officials passed it off as a training exercise. The War Department insisted that it was meant “to test and improve tactical theories of the army with respect to aerial defense of our coast line.” Army chief of staff Douglas MacArthur contended that the great air rally was no “circus” but a “test of the preparedness of the air branch for warfare” and an “exhibition of the potential resources of the United States as an air power,” which must aim to be “too strong in military aviation to be attacked.” MacArthur needed political support for the army’s planned doubling of its aerial arsenal, which explains why the exercises were broadcast live not just locally but to a vast national audience. New Yorkers could hear the action on WNYC, WOR, and WABC, while a nationwide network of 150 radio stations carried the transmission coast to coast. Announcers positioned throughout the city handed off the play-by-play as the formations passed overhead, their reports mixed in with bursts of radio traffic between the pilots and ground command.15

Illustration of the “sham battle over New York” that marked the dedication of Floyd Bennett Field. From Modern Mechanics and Inventions, July 1931.

Curtiss O2C-1 Helldivers from Floyd Bennett Field attacking King Kong, 1933. The Naval Reserve pilots were paid $10 each to “jazz the Empire State Building” and had no idea they would actually be starring in one of Hollywood’s greatest films. Pictorial Press Limited / Alamy Stock Photograph.

Those who missed the show got a glimpse of war birds over Gotham two years later in the Hollywood blockbuster King Kong. The film’s epic final scene, in which darting, diving biplanes attack Kong atop the Empire State Building, was inspired by the 1931 aerial maneuvers over the city. Herb Hirst, location manager for RKO Studios, initially wanted to use navy attack planes based in Long Beach, California, but his request was denied. The studio then contacted the commanding officer of a squadron based at Floyd Bennett Field, leapfrogging the entire naval chain of command. Hirst struck a sweet deal with the unit—in exchange for a measly $100 donation to the Officers’ Mess Fund and $10 to each pilot, he got the squadron to fly four Curtiss O2C-1 Helldiver attack planes dangerously close to the world’s tallest building. The pilots had little idea what kind of mission they were on, or for whom, and were told only to go up and “jazz the Empire State Building.” Sharp-eyed movie fans will spot the Brooklyn squadron’s whimsical fuselage insignia in some frames—Mickey Mouse riding a bomb-laden goose past the Statue of Liberty. The final footage was intercut with shots of another squadron of aircraft—Boeing P-12 fighters—along with close-ups of a rather poorly made scale model.16

Naval Reserve Air Squadron Curtiss O2C-1 aircraft readied for takeoff, c. 1934. The squadron’s insignia featured Mickey Mouse riding a bomb-laden goose past the Statue of Liberty. US Naval History and Heritage Command.

Floyd Bennett Field was the most advanced airport in the world when it opened. Its runways were the world’s longest, constructed of steel-reinforced concrete eight inches thick and capable of supporting the heaviest aircraft then in existence. Seaplanes and flying boats had ready access to the water via a ramp on Jamaica Bay, next to the city’s old garbage pier, with buoy-marked “runways” in the channel. Floyd Bennett was equipped with the most sophisticated navigation and lighting technology then available, including a floodlight system, installed by Brooklyn’s own Sperry Gyroscope Company, and General Electric’s mammoth illuminated “NYC” sign and arrow on a hangar rooftop. A 240-foot-long tunnel from the taxiway enabled passengers to disembark and walk directly into the Administration Building. And it was immediately a busy place. By the end of 1931, just seven months after opening, nearly eighteen thousand passengers passed through Floyd Bennett in 25,000 landings. Two years on, landings at the airfield had more than doubled to 51,828. Only Oakland Airport in California was busier, and not by much. But the surging numbers hid an ominous trend. Most of the passengers moving through Floyd Bennett were carried not by scheduled airlines, but rather by private and military craft. Three years after the grand opening, none of the major commercial carriers were offering daily passenger service at Floyd Bennett—nor would any until 1937, when American Airlines began daily flights to Boston (which lasted all of a year). Most commercial passenger traffic was going instead through Newark Airport, because Newark had an ace-of-spades advantage over the Brooklyn airfield—one that New York officials would struggle mightily to win to the city. Floyd Bennett might be the best airfield in the world, but Newark moved the mails.17

Newark Airport began operating in October 1928 and by 1930 was already served by several passenger airlines. This was because it had been designated the official eastern airmail terminus by the United States Post Office Department. Between the end of World War I and 1927, the Post Office operated its own fleet of aircraft, after which it began contracting with commercial operators to carry the nation’s airmail. The object was to encourage the development of civilian airlines, as passenger traffic alone was insufficient to keep an operator in business. Transporting airmail subsidized the infant airlines, and so those airports endorsed by the Post Office Department were also the ones that developed the first regular scheduled passenger service. The Department of Commerce had very rigorous standards for airports handling the nation’s mail, and Newark Airport had been planned with just these standards in mind. New York, on the other hand, had overlooked them—city officials were so certain their state-of-the-art field in Brooklyn would automatically be made the region’s new airmail terminal that they failed to take the Commerce standards seriously. As a result—and for all its modern technology—Floyd Bennett fell short on a number of counts and failed to win the essential Class A1A rating. There was also that little matter of geography. The Brooklyn airport was actually closer by several miles to lower Manhattan than was Newark. But Floyd Bennett was stuck in New York City’s deep rural south, where even water and sewer service had only just arrived. Getting the mail there from Manhattan meant a long slow haul by truck across the East River and down the full length of Flatbush Avenue—Brooklyn’s ancient, heavily congested Main Street (the Gowanus Expressway and Belt Parkway would not be built for another decade). Skeptics had repeatedly warned of this, to no avail. After the final Board of Estimate vote for Barren Island, the New York Times moaned that “as a terminal for air mails Barren Island will hardly be satisfactory.” Newark Airport, despite being separated from the city by the Hudson and Newark Bay, was easier to get to and from by both rail and road. Trains had been crossing the Hudson River for twenty years by now, and the North River Tunnels provided a swift rail connection between Newark and Pennsylvania Station and the central post office on Eighth Avenue. In inclement weather, mail at Newark could be easily transferred to trains for delivery by rail—an advantage Floyd Bennett Field wholly lacked. Even more importantly, Newark Airport enjoyed easy motor vehicle access to Manhattan via the Pulaski Skyway and Holland Tunnel.18

A variety of increasingly desperate schemes were proposed to overcome the Brooklyn airfield’s accessibility handicap and make it easier to reach for both passengers and—crucially—the mails. Some suggested that autogiros could be used to fly parcels directly to the rooftops of Manhattan buildings. An aerial taxi service was launched at Floyd Bennett Field in 1931, running between Jamaica Bay and seaplane docks at West Thirty-First Street and at the foot of Wall Street. There was Richard Gibbons’s rooftop landing fields, discussed earlier, which might handle “small ships taxiing cargoes from giant air transports at the airports to the heart of the city.” In 1934 a dubious “air train” scheme was tested, city officials hoping it would quite literally put Floyd Bennett Field on Post Office Department maps. It was the brainchild of pilot-entrepreneur J. K. O’Meara, aeronautical engineer Roswell E. Franklin of the University of Michigan, and a Bronx-born haberdasher named Elias Lustig, who made a fortune in men’s hats. The Lustig Sky Train, as it was known, consisted of a single “locomotive” airplane towing several Franklin PS-2 glider “cars” filled with sacks of mail (including twelve thousand commemorative cachets for philatelists). The plan was to take off from Brooklyn, gain altitude (and publicity) circling the city, and then head south for the nation’s capital. The third and last glider in the train would cut loose over Philadelphia to land at Camden Airport; the second over Baltimore, bound for Logan Field; and the third over Washington, where—incredibly—it was to “land in the Ellipse between the White House and the new Postoffice Building.” The Lustig Sky Train took to the air at Floyd Bennett on the morning of August 2, each glider car loaded with a hundred pounds of mail trucked over from the Newark post office. All went well at first. The Eaglerock locomotive plane “roared down the runway,” wrote the Eagle; “the three gliders, balancing each on a single wheel and spaced about 200 feet apart, trailed after like the tail of a kite.” The crazy train was sighted over Philadelphia just before one o’clock. But headwinds were fierce, forcing the tow plane to land there for more fuel. After the train took off a second time (minus the Philly-bound glider, piloted by Professor Franklin himself), it ran into a massive thunderstorm over Chester, which drove it back to the ground again. The trip was rescheduled for the following day, but press and public alike had already lost interest in what was clearly a bad way to transport either the mail or—as O’Meara had planned—living, breathing passengers. It hardly helped that the whole thing was a Soviet innovation, first tested that May by Russian airmen piloting a three-glider air train eight hundred miles from Moscow to Koktebel in the Crimea. When the Brooklyn air train got back to Floyd Bennett on August 5, hardly anyone was on hand to welcome the pilots home.19

Perhaps the most workable—if unusual—solution to the Floyd Bennett mail access problem was Clarence Chamberlin’s proposal to construct an underground pneumatic tube that would convey parcels from the airfield to the Brooklyn General Post Office on Tillary Street in all of ten minutes. Such a system had been in use in Manhattan since the 1890s, and later extended over the Brooklyn Bridge. Letters and parcels were placed in large cylindrical canisters, breech-loaded into a launch cannon by “Rocketeers,” and sent on their way at an average speed of thirty-five miles per hour. To celebrate the system’s opening in October 1897, a cat was coaxed into a canister and sent on a short, harrowing ride to the post office at City Hall (leading some to dub the mail tube system the “cat subway”). To demonstrate just how effective a pneumatic system could be for Floyd Bennett Field, Chamberlin staged a “parcel race” from a building on Varick Street to the old Custom House. The package sent by tube arrived in just over four minutes; the one sent by taxi took twenty-five minutes. In the end, the most obvious solution to the airfield access dilemma would have been by simply extending subway service down Utica Avenue or—better yet—from the Flatbush Avenue terminus of the Nostrand Avenue Line (today’s 2 and 5 lines, neither of which makes it past Brooklyn College even now). Doing so would have not only made New York’s new airport functionally part of the city’s transportation network, but brought subway service to the entire southeast quadrant of Brooklyn—long (and still) underserved by rapid transit. An express track along this route would likely have made it possible to get from Floyd Bennett Field to Wall Street in under thirty minutes—a whole lot better than a forty-five-minute, $60 cab ride from Kennedy.20

Cora Bennett and Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia with pilot Jack O’Meara at Floyd Bennett Field, August 2, 1934, as the Lustig Sky Train prepares for its first (and only) flight. Times Wide World Photo / New York Times.

The fight for Brooklyn’s airfield was kicked up several registers by the city’s new mayor, Fiorello H. La Guardia. An experienced aviator himself, La Guardia served in the Army Air Corps with the American Expeditionary Forces in Italy during the First World War, and—as a congressman from East Harlem—had piloted one of the six hundred warplanes that flew over the city in the 1931 aerial armada. Elected mayor on a fusion ticket in 1933, La Guardia refused to accept that Gotham’s flagship airfield would be located not in New York City but in the bogs of New Jersey. The mayor was on hand for the launch of the Lustig Sky Train in August 1934, cheering it airborne alongside Floyd Bennett’s widow, Cora. Cocksure from his electoral victory, he pushed for the airfield most memorably on a flight back from Panama with his wife on November 24. As the TWA airliner rolled to a stop, La Guardia refused to disembark, pointing out that the destination on his ticket read New York City, not Newark. A parade of airline officials pleaded with him to conform, but he remained in his seat. Eventually the big engines were cranked up and the aircraft—empty but for Fiorello and Marie—took off for Brooklyn, where La Guardia disembarked victoriously.21 Over the next several years, La Guardia put the full-court press on the issue, calling favors in from Washington and directing every Brooklyn lawmaker to write to the Post Office Department detailing Floyd Bennett Field’s advantages over Newark. But unfortunately for the Little Flower, the newly appointed postmaster general of the United States, James A. Farley, was no shrinking violet himself. Farley was a kingmaker with friends in very high places, with a temperament every bit as tenacious and forceful as La Guardia’s. He had helped Alfred E. Smith win the governorship in 1918 and played a major role in getting Franklin D. Roosevelt elected president; the postmastership was his reward. It was going to take more than airport antics to convince Farley to pull the airmail rug out from under Newark—where the airlines had made substantial investments in terminals and hangars.

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, an experienced pilot, sits hopefully in the cockpit of a TWA DC-1 mail plane at Floyd Bennett Field, November 1934—one of his many ploys to sway the postmaster general to designate Floyd Bennett Field the airmail hub of greater New York City. La Guardia and Wagner Archives.

Farley played fair, however, and gave La Guardia more than ample opportunity to make his case for Floyd Bennett Field. In early 1935 he directed his staff to study the situation. Newark officials, led by mayor Meyer C. Ellenstein, held their breath, well aware that New York had the might and money for a long fight. The airlines, meanwhile, delighted in this big row for their hand in marriage; “bargaining with the fears of each of the municipalities,” wrote Herbert Kaufman, “the airlines were in a position to extract the most favorable terms from both.” On August 24 the verdict came down; the Post Office Department had determined that Newark Airport simply offered “superior advantages” over Floyd Bennett Field, which presented “no . . . substantial saving in the time of handling the mails between the airport and the General Post Office in New York City.” New Jersey had won. But La Guardia was not yet ready to accept defeat. He marshaled his forces to attack the issue again, appointing a Committee on Airport Development to lobby Washington (chaired by the inimitable Grover A. Whalen), and announced $3 million in improvements for the Brooklyn airfield. Two new runways were built using funds from the Works Progress Administration; a rotating beacon was erected; the looming hazard of the old New-York Sanitary Utilization Company chimney was felled (see chapter 6); special mail-hauling subway cars were promised for the Nostrand Avenue Line. La Guardia was no fool, of course: even as he continued to fight for Floyd Bennett Field, he also quietly arranged for the city to exercise its option on North Beach Airport in Queens—what would one day become La Guardia Airport. And a good thing, too; for this time Farley himself issued the verdict: Floyd Bennett Field would never be the region’s airmail terminus. The Brooklyn dream of a “Grand Central of the Air” thus vanished like ground fog in the sun. It was the biggest public-works defeat of La Guardia’s career.22

But the very factor that caused Floyd Bennett to fail as a commercial airfield—its remote location on the edge of the sea—made it ideal for experimental aviation. All through the 1930s it served as the launch place and landing pad for an extraordinary number of record-breaking flights. Many of the most celebrated figures in the Golden Age of Aviation were regulars at the Brooklyn field—Wiley Post, Roscoe Turner, Amelia Earhart, Hubert Julian, Laura Ingalls, Jimmy Doolittle, Howard Hughes, Douglas “Wrong Way” Corrigan. Two months after its opening, Hugh Herndon, Jr., and Clyde Pangborn took off from Floyd Bennett Field for Wales in a potbellied Bellanca Skyrocket—the Miss Veedol—on a round-the-world journey they hoped would land them the $25,000 prize offered by the Asahi Shimbum newspaper for the first nonstop flight across the Pacific. They were an unlikely pair and quarreled all the way—Herndon was the moneyed son of an oil heiress, a Princeton dropout who could hardly read a compass; Pangborn was a seasoned barnstormer and former mining engineer from the West Coast. Somehow they managed to get across all of Europe and Asia without killing each other, stopping in London, Berlin, Moscow, a small village in what they thought was China (it was Mongolia), and eventually Khabarovsk, Siberia. From there they made the short hop to Tokyo, where they were promptly arrested for lacking visas. Locked up for weeks as suspected spies, they were given a single chance to leave Japan in the Miss Veedol. If that failed, the aircraft would be confiscated, and the pair would be sent home on a very long boat ride. They spent their internment productively—planning the transoceanic flight home—only to have their navigation charts stolen by the ultranationalist Kokuryūkai (Black Dragon Society), who wanted a Japanese to win the prize. Herndon and Pangborn finally got airborne again from a beach at Misawa in Aomori Prefecture. The plane was so overloaded with fuel that Pangborn was forced to dump seat cushions and survival gear, and he devised a means to jettison the plane’s landing gear after takeoff to reduce weight and drag. Thus humbled, Miss Veedol waddled back forty-five hundred miles to the United States. It belly flopped to a stop on the outskirts of Wenatchee, Washington, three days later, making Herndon and Pangborn the first to fly an airplane across the mighty Pacific. The epic journey came to a close when they landed back in Brooklyn on October 18—this time smoothly on a new set of wheels.23

A TWA DC-1 refuels at Floyd Bennett Field en route to Los Angeles on a record-breaking flight, May 16, 1935. Rudy Arnold Photo Collection, Archives Division, National Air and Space Museum.

Wiley Post (left) and Harold Gatty with the Winnie Mae shortly after their record-breaking flight around the world in July 1931. Post repeated the flight solo two years later. Leslie Jones Collection, Boston Public Library.

On November 14, 1932, a swaggering speed demon named Roscoe Turner roared into the Brooklyn sky on a record-breaking dash to California, making the trip in just under thirteen hours. A Mississippi farm boy, Turner drove an ambulance in World War I and later learned to fly, barnstorming across the country and gaining fame as a Hollywood stunt flyer and air racer. Like many aviators of the time, he had a flair for style, sporting a waxed mustache and often flying with a lion cub named Gilmore (after his oil-company sponsor). An even more colorful denizen of the Brooklyn tarmac was Hubert Fauntleroy Julian, the self-styled “Black Eagle of Harlem.” With a clipped Oxford accent and a proclivity for exaggeration, Julian was an adventurer whose life story is a magnificent mash-up of fact and fantasy. Born to a family of cocoa planters in Trinidad, Julian emigrated to Canada as a teenager, where he claimed to have flown for the Canadian Medical Services during World War I. He moved to Harlem in his twenties, appearing one afternoon at Clarence Chamberlin’s landing strip in New Jersey. Claiming to be a professional parachutist, he convinced the flyer to take him up for several trial jumps. When he refused to climb out of the open cockpit, Chamberlin suggested jumping off the wing. Back up at altitude, the youth still wouldn’t jump; he had borrowed a new type of pack chute and didn’t trust it would open. Chamberlin circled and circled, increasingly annoyed at the fuel he was wasting. Finally the flyer waggled the plane and shook his rider free. Julian never did let go of the wing strut, however, which had broken off; now the plane’s wings were flapping dangerously loose. When Chamberlin finally landed, Julian was already on the ground—tangled in his cords but smiling, wing strut still in hand. The men became fast friends.24

On April 29, 1923, Julian made what was probably the first parachute jump within New York City limits, leaping high over Harlem from an airplane piloted by another African American, Edison McVey. The streets were filled with spectators, for just before jumping the men had tossed a pair of noise bombs overboard to get attention. Julian floated down dressed in crimson tights and tunic “such as Mephistopheles wears,” the Times elaborated—aiming for St. Nicholas Park, but landing instead on a tenement roof at 301 West 140th Street (now P.S. 123). He was handed a summons for disorderly conduct but carried triumphantly off by the crowd to Marcus Garvey’s Liberty Hall. There he gave a speech urging citizens to support a nearby black-owned department store before it fell into the hands of whites—and, incidentally, “to patronize the eye doctor whose card he carried on his shirt front.” Julian made several more jumps over the next six months, selling each to a local merchant whose advertising banner he would display prominently on descent. In September he made a five-thousand-foot jump at the Police Games in Jamaica, Queens, before an audience that included boxer Jack Dempsey and Governor Al Smith. The fun and games ended in November, when another Harlem jump with Chamberlin left him dangling precariously from a police station rooftop. He was hauled in by two patrolmen through a second-floor window. Julian then took up flying, trained by Chamberlin and McVey (there is no evidence he had piloted anything more than his imagination in Canada). Soon he was buzzing Harlem rooftops and parades of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. In 1924 he began soliciting funds for a flight to Liberia, which he advertised by placing the seaplane Chamberlin sold him—the Ethiopia I—on the corner of Lenox Avenue and 139th Street. Julian kept putting off the expedition until a federal agent explained that he would be charged with felony mail fraud if he didn’t at least try.25

Hubert Julian with his Packard-Bellanca J-2 Special Abyssinia holding a press conference at Floyd Bennett Field, September 1933. Rudy Arnold Photo Collection, Archives Division, National Air and Space Museum.

So on July 4, with hundreds of spectators cheering, the Black Eagle roared mightily down the Harlem River in an aircraft he had never flown before. A pontoon tore off, followed by the other; the plane lurched upward and within minutes plunged into Flushing Bay. It vanished for a moment, but then “bobbed up to float with sudden peacefulness”—words that well described the buoyant and irrepressible Julian. Not long afterward, the flyer was spirited off to Africa by imperial edict—literally—when agents of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie recruited him to fly in a coronation extravaganza. The regent was so impressed by the black American that he granted him command of the infant Ethiopian air force. But then Julian flew Selassie’s cherished de Havilland Gipsy Moth into a tree, and was promptly expelled. Back in New York and finally a licensed pilot, he began plotting treks across the country or around the world that usually never left the ground. His handsome black diesel-powered Packard-Bellanca J-2 Special, the Abyssinian—which he planned to fly to India—became a Floyd Bennett fixture. After Italy invaded Ethiopia, Julian returned to fight the colonial aggressors. He was soon booted again, this time for romancing one of Selassie’s daughters. In retaliation he began lecturing on Ethiopian atrocities (as Huberto Juliano) but was revealed to be receiving payments to do so from Italian agents. Ever resilient, Julian later flew Morane-Saulnier fighters for the Finnish air force, and produced at least one “race movie”—Lying Lips, released in 1939 and starring James Earl Jones’s father, Robert.26

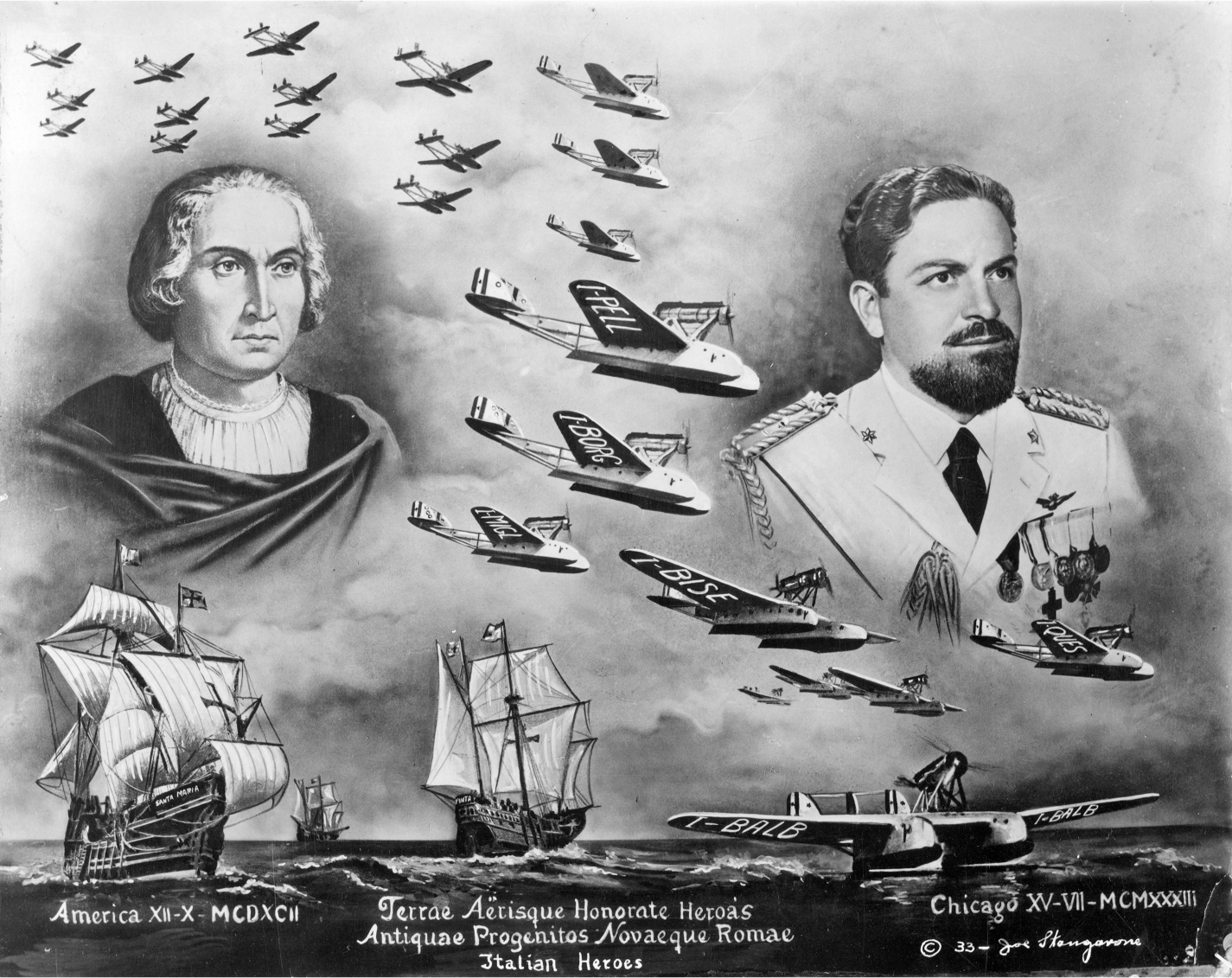

The summer of 1933 was an especially busy one at Floyd Bennett Field. At the crack of dawn on July 15, Wiley Post took off on a solo round-the-world flight that would make him one of the most celebrated pilots of his generation. Son of Texas cotton farmers with little formal schooling and a rap sheet for highway robbery, Post leveraged a near tragedy into a successful flying career. When he lost his left eye in an oil-field accident, he donned an eye patch and used the settlement money to buy an airplane. He shot to fame several years later by winning a major air race from Los Angeles to Chicago. In 1931 he circumnavigated the globe with Australian Harold Gatty. Now he would do it alone. From Brooklyn he flew to Berlin in record time, piloted his way across northern Europe to Moscow, over the Ural Mountains (passing some peaks that were higher than he was able to climb), across Siberia and the Bering Sea, and on to Fairbanks, Edmonton, and—seven days, eighteen hours, and forty-nine minutes later—New York City. When his Lockheed Vega—the Winnie Mae—landed back in Brooklyn at midnight on July 22, Post was greeted by seventy-five thousand people, many of whom rushed toward the plane and its spinning propeller. A unit of fifty mounted police had to drive back the crowd, which nonetheless mobbed the weary flyer.27 The airfield had hardly been quiet while he was away. On the sultry afternoon of July 19, two dozen Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boats slowly circled Jamaica Bay and, over the next nineteen minutes, landed like Neptune’s tridents in groups of three on Clarence Chamberlin’s mile-long seaplane runaway. The twin-engined, double-hulled craft had left Italy two weeks before on an international tour. Leading in a ship marked I-BALB was the aristocratic Italian air minister and self-styled Garibaldini, Italo Balbo. An erudite Ferrarese with a penchant for Virgil, he nonetheless came of political age cracking the skulls of labor organizers and socialists in and around Bologna as a young fascist squad leader, and helped organize Mussolini’s 1922 March on Rome. For many, the brilliant, charismatic Balbo was the very essence of the “New Italy.” So was aviation, which had inspired the Italian futurists and which Mussolini long yearned to link with fascism.

Hubert Julian with his wife, Essie Marie Gittens, December 1935. New York Daily News / Getty Images.

Balbo was a competent enough pilot, but his real genius lay in public relations and political organizing. Appointed air minister by Mussolini in 1926 (largely to keep this potentially dangerous rival occupied), Balbo set about planning the regime’s greatest publicity stunt—a series of international “aerial cruises” to strengthen diplomatic ties and showcase Italian air power. He would personally lead them all. The first was a neighborhood stroll around the Mediterranean; the second a disastrous flight down the African coast to Bolama, Guinea-Bissau (where two planes and five men were lost), and across the Atlantic to Brazil. The third expedition—dubbed Crociera Aerea del Decennale to celebrate ten years of Italian fascist rule—was the longest and most symbolic; for it brought Balbo back to the very place that had inspired the expeditions years earlier. It was the sight of the Manhattan skyline seen from an ocean liner in 1928—“the bizarre, colossal outlines of the chaotic metropolis, wrapped in epic curtains of smoke and fog”—that first seized Balbo with the vision of a triumphant flight of Italian airplanes to America. His fleet departed the Italian coastal town of Orbetello on July 1, crossing the Alps “in a majestic formation,” wrote biographer Claudio Segré, “that was widely reproduced in photographs, on postcards . . . even on a book jacket.” From Amsterdam, the men made landings at Londonerry, Ireland, and Reykjavik, Iceland, before crossing the north Atlantic to Canada. After a stop in Montreal, they headed to Chicago, escorted by a formation of American warplanes that spelled out ITALY in the sky. At Chicago, Balbo was feted with a five-thousand-plate banquet, named “Chief Flying Eagle” by a contingent of Sioux Indians, and granted an honorary degree by Loyola University. One million Chicagoans gathered to bid him farewell several days later as his flying boats roared skyward from Lake Michigan for the thousand-mile trip to New York. Seven hours later they soared down the Hudson in a large V-formation—“like so many great water birds flocking southerward in the autumn,” gushed a reporter from the Chicago Tribune. A battery of guns on Governors Island fired a nineteen-volley salute as the fleet passed overhead on its way to Jamaica Bay. There, as Balbo made landfall on a barge, a Brooklyn girl named Grace Mastelloni swam out to greet him; clambering on board and dripping wet, she stood erect and hailed him with the fascist salute.28

As in Chicago, Balbo and his company of a hundred handsome flying men were the darlings of the city for most of a week, honored with banquets and dinners and one of the largest ticker-tape parades yet staged in New York. For the city’s many citizens of Italian stock, the Balbo visit was a moment of cultural triumph that came in the darkest year of the Great Depression. It is easy to censure retrospectively the Italian American community for so enthusiastically receiving the Italian aviator. But with the full horrors of fascism as yet unrevealed and World War II still years away, it made sense that Balbo would be regarded as a symbol of hope and resilience to a struggling immigrant people. Until World War II, Italians in America were known mostly as ragpickers and organ-grinders, swarthy aliens with garlic breath and a penchant for crime—a place in society not unlike that of undocumented Latin American immigrants today. When Balbo stepped ashore at Floyd Bennett Field—with the beard of an Assyrian king and resplendent in his starched whites, onto the very same dock where a generation of Mezzogiorno immigrants had sorted through the city’s garbage—it was a victory not only for the Ferrarese aviator but for tens of thousands of New Yorkers of Italian heritage. Balbo understood this well. At a Madison Square Garden welcome rally, one of the high points of his life, he exhorted the Italians of America to be proud of their heritage—Mussolini, he asserted, had “ended the period of humiliations.” Balbo had spent two full years planning the North American expedition, and the investment paid off handsomely. The voyage was a political and logistical triumph, and made Balbo’s a household name on both sides of the Atlantic. He and his men were hailed like gods when they finally returned to Rome. But it also brought about his demise. Balbo and Mussolini had a tense relationship, clashing over racial laws and Italy’s alliance with Nazi Germany. Balbo considered the union with Hitler a strategic blunder, and he vehemently opposed the regime’s campaign against the Jews. “Surely,” he implored, “we’re not going to imitate the Germans!” Paranoid that the popular aviator would one day stage a coup, Mussolini gave him a velvet exit, installing him as governor general of Libya, then an Italian colony. It was there, on a flight back to Tobruk in June 1940, that he was killed when the aircraft he was piloting was shot out of the sky by friendly fire. Many still believe, despite considerable evidence to the contrary, that Mussolini had ordered his death.29

Columbus and Balbo, problematic heros. Portrait photograph by Joseph Stangarone, 1933. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Balbo’s fleet of twenty-four Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boats over the Hudson en route to Jamaica Bay, July 19, 1933. Collection of the author.

Balbo may have been the first fascist flier to cast a shadow on Brooklyn, but he would not be the last. On April 25, 1934, a Brooklyn fly girl named Laura Houghtaling Ingalls touched down at Floyd Bennett Field after an extraordinary seventeen-thousand-mile flight across Central and South America—from Mexico down the coast to Chile, over the Andes to Rio de Janeiro, up to Cuba, and on to New York. It remains the longest solo flight ever made by a woman. Ingalls was the first woman to fly solo across the United States—an accomplishment routinely attributed to Amelia Earhart—and in September 1935 broke Earhart’s transcontinental speed record, piloting a Lockheed Orion from Burbank to Brooklyn in thirteen hours, thirty-five minutes. Ingalls was a quixotic figure who flew with a six-shooter, lived in airport hotels, and signed her name with the Roman symbol for Jupiter. Born to a well-off family with a palatial brownstone at 321 Clinton Avenue, she studied music in Paris and Vienna, trained as a nurse, and danced briefly with the troupe of famous Sevillan Maria Montero before following her passion for flight. Recognized as one of the boldest stunt pilots of the era, Ingalls garnered more transcontinental speed records than any other woman. But her moment in the limelight was brief, brought to an end by a shadowy series of events as war loomed again in Europe. Like many Americans in the 1930s, Ingalls was opposed to American military intervention in Europe and—like Charles Lindbergh—became active in the isolationist America First Committee. In September 1939, she was arrested for flying into restricted airspace to “bomb” the White House with peace pamphlets on behalf of the Women’s National Committee to Keep the United States Out of War. A bright blip on J. Edgar Hoover’s radar, Ingalls was arrested in 1941 by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and charged with being an agent of the German Reich. She had been recruited to infiltrate the American antiwar movement to spread Nazi propaganda by Baron Ulrich von Gienanth, a high official with the German Embassy and a covert Gestapo officer. The celebrated aviatrix, it turned out, was an eager Nazi sympathizer who admired Hitler, read Mein Kampf, and—according to her New York plastic surgeon—even wore a swastika pendant. Ingalls was convicted of being a spy and locked up for most of a year at the federal women’s prison in Alderson, West Virginia. Her flying career over, she lived out the rest of her life in a secluded California canyon home.30

By 1938, Floyd Bennett Field had only about a year left as Gotham’s official airport; work on its North Beach replacement was by then well under way. That summer Howard Hughes and a crew of four set off from Brooklyn to circumnavigate the globe in a twin-engine Lockheed, mainly to test new radio and navigation instruments. They ended up setting a new round-the-world record, besting Wiley Post’s time by four days. Just days later, a youthful Californian named Douglas Corrigan captured the hearts of millions with one of the most improbable and celebrated flights of the twentieth century. On the morning of July 17, Corrigan ambled off from Floyd Bennett in an aged Curtiss Robin, its door held shut by baling wire. He had filed a flight plan to the West Coast but headed out to sea instead. Some twenty-eight hours later he touched down at an airfield in Dublin, Ireland, claiming to an astonished crowd of airport personnel that he had meant to fly to California. In fact, Corrigan had petitioned federal authorities several times for permission to fly to Ireland but was rejected because his airplane was deemed too rickety. When he returned to New York—by ship this time—an estimated one million New Yorkers cheered “Wrong Way” Corrigan in a ticker-tape parade that eclipsed even the one staged a decade earlier for Charles Lindbergh. “My compass must have been wrong,” he ventured, with a winning grin and a twinkle in his eye.31

Early rendering of Idlewild Airport, 1945, what would eventually become John F. Kennedy International Airport. New York City Municipal Archives.