The Primal Endurance approach offers a refreshing alternative to the sugar-dependent, overly stressful “chronic” approach to endurance training. The typical workout pattern of doing workouts that are slightly too hard, too frequently, with insufficient rest between them, coupled with a pro-inflammatory high-carb diet and hectic lifestyle practices, leads to burnout, elevated disease risk, and accelerated aging.

The Primal Endurance approach focuses on comfortably paced aerobic workouts to build an endurance base over a period of weeks or months without the stress of moderate- to high-intensity workouts. Aerobic workouts and training periods entail exercising at or below your maximum aerobic heart rate, as determined by Dr. Phil Maffetone’s simple calculation: 180 – age = maximum aerobic heart rate (with some adjustment factors). Be disciplined to avoid drifting above this very comfortable intensity level and entering the so-called “black hole,” where aerobic development and recovery are compromised by workouts that are slightly too stressful. Aerobic development has been a hallmark of every elite performer in every endurance sport for more than fifty years.

The seven habits of highly effective Primal Endurance athletes are: getting adequate sleep, expertly balancing stress and rest (in workout patterns and in life), implementing an intuitive and personalized approach to training, emphasizing aerobic development, carefully structuring high-intensity workouts and training blocks, engaging in complementary movement and mobility practices, and following an annual periodization program.

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM ABOUT endurance training has long emphasized more, more, more: a firm belief that more raw mileage and hourly volume equates with more competitive success. Over the past several decades, world record holders and Olympic gold medal winners fed this beast by attributing their success to the prodigious workloads they performed in training. With no better options pondered, the masses fell in line and doggedly tried to complete as much volume of work as possible in the name of peak performance. What resulted over decades of trial and error was a harsh realization that elite athletes are elite for a reason, and that the training schedule of a champion has little relevance to the optimal approach for an amateur competitor balancing endurance goals with real-life responsibilities and stressors.

The pure mileage fad faded as the road-weary endurance community came to the realization that it’s not as simple as filling the logbook and then setting records on the race course. As endurance training and racing became a pop culture phenomenon, a much wider audience joined the old war horses on the marathon, triathlon, and ultra run starting lines. Slick magazines and books appeared everywhere, filled with all manner of “expert” training advice. As an evolution from the flawed linear assumption that mileage is king, the catch-all phrase “quality over quantity” rose to prominence. On the surface, this sounds great. How can you argue with an adjective like “quality” to describe your training program?

Imagine: slowing down, having more fun (in workouts and in life), and going faster too!

Unfortunately, the practical application of this maxim was essentially to speed up workout pace into the high-stress, sugar-burning intensity ranges and generate, yet again, burnout, illness, and injury. Indeed, there are many roads that lead to burnout, and the endurance movement seems to have found every single one over the years. What’s more frustrating is that we seem to continue down the burnout highway even when confronted with huge caution signs all along the way.

Okay, perhaps it’s not fair to say we blatantly ignore the warning signs of the chronic approach, because they are often nuanced and easy to misunderstand. It feels good to elevate your heart rate into a zone where you are breathing hard, sweating, and feeling a sense of accomplishment from making a respectable exercise effort. It feels good to enter those impressive figures into your online database or handwritten training journal. Also, we mustn’t forget the chemical “endorphin” high that occurs after a sustained vigorous effort.

When we experience a stressful event, whether it’s a tempo run, a road rage incident, or an important sales presentation in the conference room, the fight-or-flight response is triggered in the body. Our bloodstream becomes flooded with feel-good hormones and neurotransmitters like cortisol, dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, and the function of all of our senses is heightened.

This so-called “adrenalin rush” is part of our ancient hardwiring. When we faced the life or death environmental stressors of primal times, these feel-good chemicals interacted with opiate receptors in the brain, flooding the space between nerve cells and inhibiting neurons from firing. This masked sensations of pain and fatigue, inspiring our ancestors to continue to run away from the lion that was trying to eat them—literally—rather than give up. The same chemicals help today’s marathon runners get their depleted bodies through those final miles to the finish line.

After the chase—the stressful event—is over, these chemicals linger in the bloodstream and we experience a blissful state that today’s endurance athletes call the endorphin high, buzz, or rush. The term endorphin literally means “endogenous (internally manufactured) morphine.” In this chemical state, messages of pain and exhaustion are not fully appreciated and you feel surprisingly chill, even (or especially) after pushing your body to a maximum effort. The high you obtain validates you doing this crazy extreme endurance stuff, while your ordinary neighbors just shake their heads and wonder why.

Today, the demand for life or death physical efforts are rare, but our brains and bodies don’t know the difference between the ancient lion chase and the modern triathlon starting line. And we tend to engage in the latter more than the former, abusing this delicate hormonal process that was designed for life or death matters only. Those of us who take satisfaction in conducting tough workouts are literally addicted to the chemical high that comes as a consequence of these efforts.

We realize that “addicted” is not a complementary term, but it’s important to recognize the chemical payoff you enjoy when you push your body through challenging individual sessions, training blocks, or even crazy six-month pushes to get your startup company to IPO day. Then you can sit back and utilize your higher reasoning skills to conclude that you might not want to abuse this fight-or-flight, endorphin-high programming, because your body will eventually become exhausted if you do it too frequently. Certainly you can relate times when you have become overtrained and fried your central nervous system to the extent that instead of a pleasant endorphin buzz after a vigorous session, you feel like taking a nap…and not waking up for fourteen hours!

So, we have some major influences conspiring to repeatedly plunge us into chronic patterns. First, we have the cultural influences, the prevailing philosophy that encourages “chronic” training, macho-ing out on mileage totals, never missing a workout, or always leading the group down the trail or up the mountain. We also have our own highly motivated, goal-oriented mindsets—really our ego demands—that mandate we do something productive and impressive toward our fitness goals and high standards every single day.

Finally, we have that chemical stuff going on, that compelling, hardwired desire to seek pleasure and dull pain through the release of adaptive fight-or-flight hormones. Well-meaning and enthusiastic as we may be to become fitness pillars in our community, the chronic patterns we engage in destroy health, compromise performance, and lock us into a sugar-burning, fat-storing metabolic state.

Chronic cardio is a sustained pattern of overly stressful endurance workouts: sessions that are a bit too long, a bit too hard, and conducted too frequently with insufficient rest in between. A chronic approach will lead to poor competitive performance, lingering fatigue, suppressed immune function, persistent stiffness and soreness, increased injury risk, failed weight loss efforts, and finally—when your fight-or-flight resources become exhausted from chronic stimulation—burnout.

It’s bad news for your race results, but the news is worse deep inside. When you live a life of chronic stress, you develop serious hormonal abnormalities that impede cognitive function, sexual performance, and immune function. Your cardiovascular system is especially vulnerable to chronically stressful, pro-inflammatory diet, exercise, and lifestyle patterns. Strange as it may seem, your misguided fitness efforts trigger the development of oxidation and inflammation in your arteries, setting the stage for heart disease.

Dr. Peter Attia is a physician, endurance swimmer and cyclist, blogger (eatingacademy.com), and president and co-founder (with Gary Taubes) of the non-profit Nutrition Science Initiative (NuSI). He is fond of performing extreme metabolic “human guinea pig” experiments on himself, and is one of the leading advocates for the health and performance benefits of doing fat-adapted endurance training. Attia explains how heavy training can potentially damage your heart, as long bouts of exhausting cardiovascular exercise actually create a stretch in the heart.

“When we engage in an extreme effort like an all-out time trial,” says Attia, “we increase both heart rate and stroke volume [amount of blood pumped out per beat of the heart], by stretching the heart larger to pump more blood per beat. This amazing organ can quickly go from pumping three to five liters of blood around our body per minute at rest to thirty liters per minute during very intense exercise. Unfortunately, the right side of the heart, which pumps only against the low-resistance lungs, and is far less muscular than the left ventricle, is more vulnerable to damage from chronic amounts of high cardiac output training. So while short bouts of this intensity don’t appear to cause lasting damage on the heart, prolonged activity does—at least in susceptible individuals. The so-called chronic cardio patterns can cause the right ventricle to become scarred from excessive use and insufficient recovery. This scarring can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation, and even sudden death in athletes who have no evidence of atherosclerosis.”

Something called the “excessive endurance exercise hypothesis” is gaining traction in scientific circles. One of the leading voices is Dr. James O’Keefe, a sports cardiologist in Kansas City (look up his TED talk titled “Run For Your Life—at a comfortable pace, and not too far”) and co-author of four bestselling books, including The Forever Young Diet & Lifestyle. O’Keefe mentions how seasoned marathon runners, sporting good bodyweight and blood profiles, nevertheless show increased scarring, thickening, and literal searing of the arterial walls from chronic inflammation. Their heart and entire cardiovascular system are aging at an accelerated rate. They have markedly elevated levels of calcified and non-calcified arterial plaque compared to a control group of sedentary folks. An adverse coronary artery calcium value, known as the Agatson score (after South Beach Diet author Dr. Arthur Agatson), is linked to higher future mortality rates. Some of the medical folks deeply involved in this disturbing issue are using the sobering nickname of “Pheidippides cardiovascular disease.”

Keep in mind that the heart is damaged not by vigorous exercise, but from chronically excessive vigorous exercise. Dr. O’Keefe explains in his TED talk that after you do something extreme like a marathon, the micro tears occur in the arteries and your heart becomes inflamed and burned—just like any other muscle challenged through extreme use. This is why you may have heard that if a marathon finisher strolled into an emergency room and had some blood panels run, he or she would have levels of inflammation markers like troponin and C-reactive protein high enough to diagnose acute myocar-dial infarction—a heart attack. Thankfully, the heart and arteries are good at healing up and the damage heals in a couple days. However, if you engage in chronic exercise patterns, you get stiff, thickened, scarred, calcified arteries; your heart becomes prematurely aged as a direct consequence of your running.

Dr. O’Keefe’s firm conclusion is that moderate exercise patterns are healthier than extreme ones. “The fitness patterns for conferring longevity and robust lifelong cardiovascular health are distinctly different from the patterns that develop peak performance and marathon or superhuman endurance. Extreme endurance training and racing can take a toll on your long-term cardiovascular health. For the daily workout, it may be best to have more fun and endure less suffering in order to attain ideal heart health,” he explains in his talk.

While being able to break the hour barrier for 10K might get you laughed out of age-group contention, O’Keefe suggests that reaching such a modest fitness capability makes you “bulletproof” when it comes to disease risk. “We’re not born to run. We’re born to walk, and to move more in general,” O’Keefe tells his TED audience. He goes on to make a specific recommendation that running two to five days per week for a total of ten to fifteen miles, at around a ten-minute-per-mile pace, is ideal for bulletproof cardiovascular health. The vaunted Copenhagen heart study concurs, saying two to three runs per week for a total of 1 to 2.5 hours gives you a 44 percent reduction in mortality compared to sedentary folks. O’Keefe and the Copenhagen study and many other experts assert that when you go beyond these modest standards, you start to compromise the many extraordinary health benefits of moderate exercise. The secret is out, and into mainstream media—such as the Wall Street Journal’s 2012 article “One Running Shoe In The Grave.”

Most of you might be cringing by this point, and it’s interesting to note that both Dr. O’Keefe and Dr. Attia report taking some heat from naysayers who challenge the assumptions that extreme exercise is unhealthy. But we must all take a step back and admit that this laundry list of cardiovascular lousiness absolutely should not be happening in a community of the fittest, most energetic, most accomplished modern humans. And it doesn’t have to. Contrary to what you might believe after spending however many years in the game, struggling to attain your mileage goals and consistent workout patterns, you do not have to struggle or suffer or constantly straddle the red line between race-ready and broken down in order to succeed in endurance sports. You can pursue even the most extreme competitive goals in a manner that supports your health, or at least doesn’t out-and-out destroy it every step of the way. Interestingly, Attia says he somewhat ignores his own moderation advice because he gets tremendous enjoyment from his endurance cycling pursuits, which extend far beyond moderate. Acknowledging the health risks associated with chronic exercise instead of being cavalier about them can be extremely helpful when you face the nuanced daily training decisions of when to back off and when to push on.

Metabolically, chronic cardio workouts are slightly too strenuous to emphasize fat as a fuel source, and instead emphasize glucose burning. While this makes the workout more difficult and generates more fatigue and sugar cravings right afterward, the truly damaging effects of chronic workout patterns occur around the clock. Workouts elevate metabolic function multiples higher than your resting metabolic function. This is measured by a figure called “Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET).” For example, an all-out sprint workout can go up to an amazing 30 MET—you are generating energy at thirty times your resting rate. Running a steady pace (e.g., 7m:30 per mile) is 13.5 MET, while even a casual bike ride (10–16 mph), easy swim, or vigorous hike will still elevate the function of the various body systems up to between 6–10 MET. So when you are pumping blood and processing oxygen and fuel to the tune of ten, twenty, or thirty times your resting rate, you send a powerful signal to your genes for how to regulate metabolic function for many hours after the workout.

Dr. Phil Maffetone, the godfather of aerobic training, and balancing health in pursuit of fitness. Legendary exercise physiologist Dr. Tim Noakes says, “I’m clever, but Phil Maffetone is a genius. He saw through this [carbohydrate paradigm endurance training and eating] stuff 30 years ago.”

Dr. Phil Maffetone reports than an anaerobic workout—even a slightly anaerobic workout where your heart rate drifts out of the aerobic zone going up hills or sprinting for city limit signs—accelerates sugar burning at rest for up to seventy-two hours after the session. That’s just enough time to recover and bang out another anaerobic workout and get round-the-clock service for sugar burning, sugar cravings, excess insulin production, suppressed immune function, and fat storage. If your goal is to perform well in endurance events, get leaner, be healthier, and delay the aging process, it’s quite possible that your training sessions are promoting the exact opposite results of your goals.

The most immediate triage response to escape the sugar-burning, fat-storing pattern is to slow down your workout pace into a heart rate zone that is predominantly aerobic, with little to no stimulation of the anaerobic system. When you hike, walk, jog, or pedal at a comfortable pace, you burn mostly fat for fuel. And since oxygen is required to burn fat, your comfortably paced training stimulates the development of additional mitochondria in your cells. These are the energy-producing “powerhouses” located in each cell that take in oxygen, along with fat, protein, and glucose, and convert them into energy in the form of ATP that fuels many cellular functions. Having mitochondrial density not only boosts performance in both endurance and explosive efforts, it supports general health by protecting you from stress-induced free radical damage.

Interestingly, your mitochondria have their own DNA, distinct from your cellular DNA. Mitochondrial DNA is inherited exclusively from your mother, which has made it valuable in tracing human ancestry and evolution. We know from the study of mitochondrial DNA that the first appearance of the genetically identical modern Homo sapiens was in East Africa around 160,000 years ago. This also means that whatever endurance gifts you have were inherited just from your mother (thanks, Mom!), not your father.

Science in this field from pioneers like physiologist John Holloszy in the 1960s showed that exercising aerobically for a long duration helped build more mitochondria. This helped validate the popularity of extreme long, slow distance training in those days. Science in the 1980s revealed that high-intensity workouts were also very effective in building more and better mitochondria.

THE HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE BENEFITS OF MITOCHONDRIAL BIOGENESIS

Aerobic workouts have a significant impact on your metabolic function at rest, so comfortable training sessions up-regulate your fat-burning genes and down-regulate your sugar-burning genes around the clock. Slowing down your workouts helps stabilize mood, energy, and appetite throughout the day, optimizes your health, speeds recovery, and makes fat loss virtually effortless when you implement a primal-style eating pattern.

What’s too hard? How much slower do you need to go? The answer is to conduct the vast majority of your endurance training sessions at or below what Dr. Maffetone calls your “maximum aerobic heart rate.” This is defined as the point where maximum aerobic benefits occur with a minimum amount of anaerobic stimulation. At this intensity, best measured by heart rate, you are burning predominantly fat, feeling comfortable at all times, able to converse without running out of breath, and not stimulating significant stress hormone production or lactic acid accumulation in the muscles.

In attempting to refine the Primal Blueprint position on this critically important heart rate value, we’ve reviewed plenty of studies and come to the conclusion that determining your maximum aerobic heart rate is not an exact science. Dr. Maffetone concurs with this, and touts his non-scientific but extremely well-field-tested “180 – age” formula—one with an assortment of subjective revision factors—as the best way to calculate your numbers.

Some endurance experts refer to this critical distinction point as the ventilatory threshold (VT), the point where an increase in effort would result in labored breathing and insufficient oxygen to perform comfortably. Exceeding this threshold causes ventilation rates to spike in a non-linear manner. You can identify your VT in a lab test, as it is believed to correspond with recruitment oxidative fast-twitch muscle fibers (known as Type IIa fast-twitch fibers; Type IIb fibers are glycolytic—reserved for maximum power efforts; Type I muscle fibers are slow-twitch and used for low intensity endurance efforts). Type IIa fibers are recruited when intensity switches from low (predominantly Type I slow-twitch fibers) to moderate and higher intensities, and is also correlated with an activation of different brain cells connected to Type IIa fast-twitch muscle fiber use.

We want to deliver a comprehensive presentation of this matter here, so we’ll also mention a couple of useful subjective tests to estimate where you transition from predominantly aerobic into anaerobic. Carl Foster, PhD, an exercise scientist at the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse, and Stephen Seiler, an American exercise scientist teaching at Agder University College in Kristiansand, Norway, have co-authored several research studies on the effects of aerobic versus anaerobic exercise. Foster promotes a “talk test” that suggests that you can converse comfortably below your aerobic limit, but where an increase in pace would soon make reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, or telling a tall tale to your training partner, difficult to do without gasping.

Also helpful is an Eastern-philosophy-influenced suggestion detailed in John Douillard’s book Body, Mind, and Sport that recommends breathing only through your nose to minimize the stress of a workout. If you are exercising in the aerobic heart rate zone, you should be able to obtain sufficient oxygen using only your nose, but you’ll know you’re exceeding that aerobic limit if you need to draw air through your mouth.

Furthermore, Douillard details how keeping your mouth closed facilitates taking deep diaphragmatic breaths, where you engage the oxygen-rich lower lobes of the lungs for maximum respiratory efficiency. Running or cycling along while taking deep, nose-only diaphragmatic breaths will reduce the stress level of your workout by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system (calming, relaxing influence) as opposed to the more common stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight response) that occurs when you conduct even a moderately difficult workout.

Nose breathing also helps you filter pollutant particles, something of particular concern for urban athletes getting an unfiltered dose of car or industrial fumes through the mouth. Furthermore, nitric oxide—a potent vasodilator—is produced in the sinus cavity, so nose breathing increases nitric oxide levels, improving bloodflow and oxygen exchange throughout your cardiovascular system.

Nose breathing during a workout is simply taking a fundamental principle of yoga, meditation, Ayurvedic medicine, and other Eastern disciplines and applying it to a rah-rah Western pursuit of endurance training. It’s true that pulling huge breaths through your nose during your workout is not the most natural or even fun thing to do, but it’s a great thing to experiment with when you really want a relaxing, rejuvenating, low-stress workout. If you tend to be stuffy or get annoyed by mucus interference, try applying a nasal strip, or just inflate your upper lip, your moustache area, and keep it puffed out. This helps the nostrils execute smoother inhalations and exhalations.

When it’s time to conduct a true recovery workout, where you don’t exceed 65 percent of your maximum heart rate, nose breathing is an excellent technique to commit to for the duration of the session. Another excellent subjective marker is that you should finish aerobic workouts with a stable energy level, mood, and appetite, and bounce back the next day without any lingering soreness or fatigue.

It’s critical to be conservative and highly disciplined about staying aerobic. Using a heart rate monitor with an identified number as your aerobic maximum and setting a limit alarm is mandatory to ensure your success with aerobic training. It’s just too difficult to maintain that level of concentration and focus on your intensity level during a casual session where your mind, and your pace, can easily wander. Besides, when we are presented with a hill, a headwind, an enthusiastic training partner increasing pace a bit, or a natural decline in efficiency that happens in the latter stages of any ordinary training session, our natural tendency is to just hang in there and allow our metabolic functions to adjust to the increased demands. That includes pulling even more aggressive breaths from your nose and achieving an undesirable acceleration in effort while still playing by the rules!

When you respect the importance of emphasizing aerobic development, workouts transition from a succession of mini-competitions (with your usual time on the route, with your training partners’ pace, whatever) to actual training sessions with a specific metabolic focus that promotes your long-term development and protects your health. Instead of sticking to arbitrary and irrelevant goals like maintaining a certain pace per mile throughout the workout, you honor irrefutable biofeedback to keep your effort level consistent and get in the habit of slowing down in the latter stages of workouts. You also get into the habit of generally training at a much slower pace than usual. No doubt about it—it can get more than a little frustrating to stick with the aerobic program, but the dividends are enormous and completely quantifiable by results in a simple, repeatable sub-max performance test known as the MAF (Maximum Aerobic Function) test.

For many athletes, it’s time to have a heart-to-heart (pun intended) in front of the mirror and consider how your daily behavior patterns align with your stated long-term goals. If you can’t muster the focus or discipline to conduct a proper aerobic training session (because some wanker on a cruiser bike blew past you on the bike path and you just had to give chase, because your annoying training partner is subtly increasing the pace on every hill, or because of whatever superficial stimulation you react to), you should admit that you are behaving in a manner incongruent with any peak-performance-related goals—or, in the case of chronic or OCD training patterns, incongruent with your health. In summary, it’s time to put aside your ego demands, set that beeper, and honor it by slowing down!

There is an assortment of opinions about what exactly constitutes that heart rate where maximum aerobic benefits occur with a minimum amount of anaerobic stimulation, but where an increase in effort would cause a non-linear spike in ventilation, glucose metabolism, lactate accumulation, fight-or-flight hormones, activation of Type IIa muscle fibers and associated brain function, and so forth. Ventilatory threshold studies suggest that in well-trained athletes, VT is around 77 percent of maximum heart rate. However, it is believed that VT arrives at a lower percentage of max heart rate in unfit individuals. While attaching VT to aerobic max is encouraging, it implies that you have an accurate maximum heart rate value. This is no easy task to determine, as it’s difficult to perform an effective test outside the lab, and the estimate calculations—while getting better than the dated and oversimplified “220 – [age]”—can still be imprecise.

Primal Endurance recommends that you use Dr. Maffetone’s “180 – age” formula to establish your maximum aerobic heart rate. If you have a techie bent, know your maximum heart rate, and want to go by a percentage of maximum heart rate, we’ll present the details on this calculation process too. Using either Maffetone or a percentage of maximum heart rate, you should get very similar numbers. If the numbers are disparate, we urge you to train at the lower of the two numbers!

Dr. Maffetone’s formula entails subtracting your age from 180 and then using that number as your maximum aerobic heart rate. Or, add or subtract five beats according to Maffetone’s adjustment factors relating to one’s level of health and fitness (details below). Maffetone has time-tested this formula over decades of hands-on work (including, interestingly, a change in running gait that Maffetone believes tips your hand that you are drifting above aerobic maximum) and detailed recordkeeping with his clients.

Whatever number you adhere to, make a sincere effort to integrate subjective factors into your analysis. You should be able to converse comfortably or breathe through your nose only (okay, with a bit of practice to get used to it) at your designated aerobic max number. You should finish aerobic workouts feeling refreshed and energized, not slightly foggy, depleted, or craving calories. If things don’t fall into place and you experience fatigue or sugar cravings in the hours after aerobic workouts, lower your numbers!

Maffetone 180 – age Formula Adjustment Factors: Here are the adjustment factors Dr. Maffetone offers in The Big Book of Endurance Training and Racing. Take 180 minus your age as your baseline number, and then adjust it accordingly if appropriate:

1. Subtract 10: Recovering from illness, surgery, disease, or taking regular medication.

2. Subtract 5: Recent injury or regression in training, get more than two colds/flu annually, allergies, asthma, inconsistent training, or recently returning to training.

3. No Adjustment: Training consistently (4x/week) for two years, free from aforementioned problems.

4. Add 5: Successful training for two years or more, success in competition.

Let’s do some comparisons to validate the Maffetone formula against percentage of max heart rate calculations. First, let’s take a forty-year-old who has had decent fitness progress in recent years. The new gold standard for estimating max heart rate is 208 – (.7 x age), giving a forty-year-old an estimated max of 180. Hitting VT at 77 percent of max would be 139 for an aerobic max. Using the Maffetone formula, the athlete would generate a result of 140—good matchup here. An unfit forty-year-old athlete (or one who has struggled a bit with injuries and illness) might hit VT at 75 percent of estimated max, or 135. Using the Maffetone formula, this athlete would take 140 and subtract 5 beats to get 135—again a good matchup. On the other hand, some athletes perform calculations where the numbers are significantly disparate. See sidebar “Ageless Wonder” for details.

As far as the confusing assortment of training “zones” out there are concerned, we’ll tell you right now they are of minimal concern. All you need to worry about is staying below your maximum aerobic heart rate during aerobic workouts. Of course, if you are exercising below 55 percent of max heart rate or so, you aren’t getting much of a training effect, but you’re still moving! As we’ll discuss further in Chapter 8, we need to become better about blurring the lines between training and sitting on our butts all day congratulating ourselves because we have a workout on the books.

All forms of movement, including five-minute breaks from your work desk and leisurely twenty-minute strolls around the block with the dog, contribute to your aerobic development, and deliver an assortment of immune, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular benefits that can make a significant contribution to your fitness goals and greatly improve your overall health and well-being. But let’s call a proper aerobic training session something that lands between 55 percent of max heart rate and your “180 – [age]” calculation upper limit.

When you drift above maximum aerobic heart rate, glucose burning accelerates and fat burning gets pushed aside accordingly. Stress hormone production increases and a bit of lactic acid starts to accumulate in the muscles. Type IIa muscle fibers and brain cells start to kick into gear and get you into a bit of an intensity mode instead of an extremely comfortable aerobic mode. None of these metabolic shifts are easily discernable or at all debilitating. In fact, you may still feel quite comfortable as you extend your effort well beyond aerobic maximum heart rate. Psychologically, you might even gain a greater sense of satisfaction that you are actually “getting a workout” because of your slightly labored breathing pattern, elevated perspiration, and elevated perceived exertion in the brain.

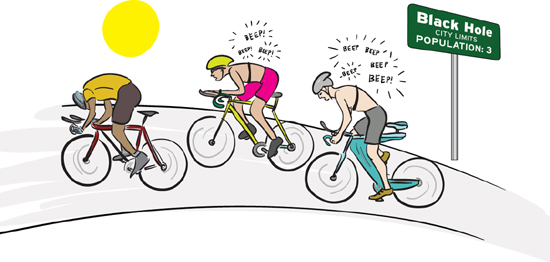

Dr. Seiler coined the term “black hole” to describe the training zone just outside aerobic maximum and up to the anaerobic threshold. Anaerobic threshold (AT) is the intensity level where lactic acid is accumulating in the bloodstream faster than you can buffer it; hence the characterization of AT as the “burn” or the “red-line” pace. Obviously, you are not going to drift a routine training session into AT range without feeling the burn and slowing down.

On the other hand, the black hole has been confirmed by numerous studies as the default landing area for people relying solely upon perceived exertion to govern intensity level. It’s a pace you can maintain for long duration without falling apart, feel like you are focused and working intently like a real athlete, and feel a sense of exhilaration and euphoria (from stress hormone production, a.k.a. the “endorphin buzz”) after the session. “Vigorous” is a good word to describe a black-hole workout. Not “brutal,” but certainly not entirely comfortable and nose-breathable like a proper aerobic session either.

While studying the training habits of elite endurance athletes in Nordic skiing, rowing, running, cycling, and triathlon, Seiler’s team discovered that elite athletes spent around 80 percent of the time training at aerobic heart rates, and only 20 percent of workout time doing high-intensity workouts. With respected follow-up studies to strengthen the initial observations, Seiler and others observed that elite performers in a variety of endurance sports either go really easy (aerobic base training) or really hard with proper interval or other high-performance sessions.

Seiler says the reason that the black hole is an ineffective middle zone is that it’s too slow to make you better, and too fast to allow for sufficient recovery. An astronomy buff, Seiler said that athletes drifting into this intensity level by default is akin to the gravitational pull caused by a black hole in space. Unfortunately, other studies have revealed that the average recreational competitor spends at least half of his or her total training time above the aerobic maximum and into black hole, anaerobic threshold, or maximum intensity heart rate zones. Fine-tuning the DumbCar!

As we consider different training philosophies, including diametrically opposing views, and try to make some sense of everything to dial in our own approach, please stay focused on the big picture. For example, one book referencing Seiler’s research called 80/20 Running promotes training aerobically 80 percent of the time and going fast 20 percent of the time. The book asserts that 80/20 models the habits of elite athletes across many endurance sports and has great science to back it up. It’s surely a lot safer and more sensible than defaulting to a 50/50 pattern like most exercisers, but it’s still making a blanket conclusion where none is warranted.

Every bit of training strategy you are exposed to requires personal experimentation and fine-tuning. It’s not as simple as following a magic formula, even one proven by elite athletes and respected studies. Furthermore, your training patterns and intensity ratios will vary widely over the course of a year with a periodized approach. During an aerobic base building period, you have to be in the aerobic zone 100 percent of the time. Going 80/20 during an aerobic period represents a dismal failure. During a high-intensity training period, you focus on maximum-effort sprints and strength-training sessions, and getting tons of rest between these explosive workouts. You drastically reduce aerobic training volume with lots of short, slow recovery workouts and far more rest days. Why worry at all about your ratios at those times?

Phil Maffetone elaborates on the metabolic consequences of training in the black hole: “When you move out of the pure aerobics system, where 90 to 95 percent of an endurance athlete’s energy comes from fat, to a black hole pace that burns more sugar, the first big downside is that you run out of fuel faster. The other is a big rise in your stress hormone levels. The black hole is really the first stage of overtraining—and it comes on fast. I’ve seen athletes train just a couple of heartbeats too high, and over time they become overtrained.” Dr. Foster adds that, “We think there’s a physiological tripwire. Slip into the black hole for a few minutes—or do an interval or two—and the body reads the whole workout as hard. It cancels the [aerobic session’s] recovery effect.”

Of course, it doesn’t hurt to occasionally open up the throttle a bit and have some fun climbing a tough mountain or completing a group training run with faster folks. You can leave the heart watch at home for these sessions, as a similar training effect has been observed when you exercise anywhere from 10 percent below AT (black hole territory) to a couple of percentage points above AT. Whatever you want to call these sessions—tempo, fartlek, hill repeats, intervals, time trials—they should be considered breakthrough workouts that approximate competitive challenges and stimulate fitness improvement.

When you eat right and sleep like a primal champ, your body does a good job recovering and getting stronger from bouts of appropriate stress like an occasional tough workout. Indeed, that’s what the fight-or-flight response is designed for—to briefly elevate your physical and cognitive function to deliver a peak performance effort, then settle back into a stress-balanced routine.

The problem comes when black-hole workouts become a pattern. The super hardcore competitors jamming through the streets in their pace-lines or meeting at the track to drop the hammer every Tuesday evening are guilty of these chronic patterns, but so are the routine gym goers who show up to aerobic, Zumba, or Spinning classes several times per week and rock out to the blasting music. Invariably, these group workouts include lots of time spent above aerobic maximum for everyone in the class, except perhaps a super fit instructor. Ditto for group training programs like Team In Training or even a high school cross country team. When a training group of disparate abilities gathers for a long run intended to be aerobic, it’s typically only aerobic for the select few folks at the front of the pack, like the top few runners on the varsity. For the majority of participants, it can easily turn into a destructive black-hole session.

Because it’s so easy to drift above aerobic maximum into the black hole, we must repeat that using a wireless heart rate monitor to constrain your intensity inside the aerobic zone is absolutely mandatory. You don’t necessarily need to pull a home equity loan for the latest $400 GPS or wattage meter gizmo, unless you are inspired and motivated by the techie elements of training. For proper aerobic base building, you simply need a monitor that will beep when you set a limit alarm. And you need to slow down when you hear the alarm. Training by perceived exertion alone just won’t cut it. We know a few pros who claim they can train effectively by feel, but they’re pros!

Get a simple heart rate monitor like a Polar FT1 (approximately $70) or another reliable brand, and use it every single time you train. Notice how your max aerobic heart rate correlates with maxing out on nose breathing, or losing your wind on the Pledge of Allegiance or in conversation with a training partner. Notice how easy it is to get pulled into the beeping zone by a small hill, an energetic song in your earbuds, or a wanker passing you on the bike trail, or just see your rate drift a bit higher at the same pace during the latter stages of the workout due to fatigue.

By the way, it’s also really important to warm up gradually to avoid black-hole risks. When your body goes from a resting state into a workout too abruptly, this can kick you into a stress response and glucose metabolism that is hard to recalibrate into calm, fat-burning mode even when you maintain a disciplined aerobic pace. Spend the first five to ten minutes of your training sessions moving very slowly, to allow blood to transfer smoothly from your internal organs to your extremities. Ditto for a gradual cooldown to minimize the stress effects of going from active to sedentary too abruptly.

If you’ve spent many hours in a sedentary position before a training session, it makes sense to start out with just a walk for a few minutes, then break into light jog for a few more minutes (apply something comparative for whatever sport you are doing) before commencing a proper training session at or near maximum aerobic heart rate. You’ll know you are fully warmed up when your skin becomes warm and moist, and your joints feel lubricated and fluid.

Regardless of your fitness level, your exercise intensity as a percentage of maximum heart rate has a similar metabolic effect on your body. In the aerobic zone, the effort feels easy, plenty of oxygen is available, and fat metabolism is emphasized. If you are an elite professional, you can run (relatively) incredibly fast at this comfortable heart rate, while a less fit person might have to alternate between slow jogging and walking to maintain aerobic heart rate levels.

Become skilled at staying comfortable during your entire workout and building upon this momentum over time with a natural increase in the pace you can sustain while still feeling comfortable. In essence, you are taking a sure-fire, low-risk approach to improvement, by methodically getting stronger and more efficient without interruption from setbacks caused by high-risk, chronic training in the black hole.

Yes, it can be quite frustrating to your competitive nature to have to slow way down during your workouts in the name of getting leaner and fitter, but it’s the absolute truth that this is the path to endurance greatness. This has been proven true by every elite athlete in every endurance sport for over fifty years, starting with the phenomenal success that New Zealand distance runners had under legendary coach Arthur Lydiard in the late 1950s.

Lydiard was the first coach to introduce overdistance training and periodization for middle- and long-distance runners. Prior to his era, distance runners essentially trained by running intervals around the track at high speeds until they collapsed. For example, Roger Bannister reported that he only trained for thirty minutes per day in preparation for the Olympics and his four-minute mile in 1954. Lydiard’s revolutionary insight was that distance runners didn’t need to develop more speed as much as they needed to develop more endurance to maintain a winning pace for as long as possible. He experimented on himself, running insane mileage (up to 240 miles per week!) and becoming the top Kiwi marathon runner in the late 1950s.

Lydiard rose to international prominence as a coach at the 1960 Olympics in Rome. He wasn’t even part of the official New Zealand coaching staff, but two of his runners won gold: Peter Snell at 800 meters and Murray Hallberg at 5000 meters. Snell, who today is a respected human performance physiologist in Dallas, TX, is a remarkable example of the importance of aerobic development in even high-speed track events. Prior to bursting onto the world scene, Snell jogged comfortably for months and months in the sand dunes of New Zealand, building endurance, strength, and aerobic capacity—without interruption from injury or burnout so common with high-intensity track training (Lydiard was also big on scheduling flexibility and personalization of individual athletes’ workloads and recovery times—what he called “feeling-based” training).

In 1962, Snell leveraged his hundred-mile training weeks and twenty-two-mile-long runs to shatter the world record at 800 meters with a time of 1m:44. This time is still world class today, and would have qualified him for every single Olympic and World Championship final since 1962. Amazingly, contention still exists about the value of aerobic development for middle-distance athletes. Even endurance and ultra-endurance athletes are captivated by increasing their “speed” through track workouts, hill repeats, and strenuous swimming interval sessions, when in reality the aerobic system is supplying almost all of the energy during competitive efforts. In a 2003 interview, Snell revealed his exasperation—here are some choice excerpts:

Even in New Zealand the feeling today is that Lydiard’s ideas are passé. I can’t believe it! I still hold the New Zealand 800 meter record—it’s [53!] years old. Most physiologists are trained on the idea of specificity and simply can’t understand that slow training makes you faster. I attended a USA Track and Field conference where the sentiment was, “We’re disturbed about the fact that we’re not getting any medals in middle-distance and distance running at the Olympics, and why is this?” And someone concluded, when they looked at the Olympics, American runners are getting buried in the last lap. Therefore, we need to teach them how to sprint. So that’s unbelievable. [laughs] There’s not a lack of speed—they’re just running out of gas, and so everyone else is cruising because of the superior endurance, is what that boils down to.

Just about every scientist I know cannot understand why slow running works. It just doesn’t seem to fit their—I suppose they’re brought up on the concept of specificity—if you’re going to be a middle-distance runner, you need to be doing something that’s related to the demands of your event. These are sort of cornerstones of coaching and so on. And then, why would you run slowly? And I’ve seen some very derogatory statements by scientists about long, slow running. Very derogatory. And I’m trying to be equally derogatory back.

The reason that emphasizing aerobic training works and that chronic cardio sucks is as follows: When workout intensity drifts out of the aerobic zone, you start burning an ever-greater percentage of glucose (the preferred fuel choice when oxygen is insufficient) and stimulate the release of stress hormones and lactic acid into your bloodstream. While it’s beneficial to simulate high-intensity competitive efforts in training once in a while, it’s destructive to simulate scaled-down competitive efforts all the time. When you drift above your aerobic max and into the black hole at 82, 85, or 90 percent of max heart rate, it’s not as hard as an all-out race, but it’s hard enough to compromise your fitness progress and challenge your health.

Lydiard’s legacy has been honored by astute modern-day coaches like Maffetone, who was the first guy to bring aerobic training into the limelight through his association with the 80s- and 90s-era top triathletes Mark Allen, Mike Pigg, and Tim DeBoom. Allen’s story is particularly compelling because we are talking about a guy who, early in his career, earned the nickname “Grip,” as in Grip of Death. This referred to how one held the handlebars when trying to hang with Allen on training rides, as he was known for pushing brutally hard virtually every time out in his early years in the sport. As many swimmers schooled in high-volume, high-intensity training patterns have discovered, this all-out, all the time approach didn’t work very well out of the water. Allen was forced to reconsider his strategy and rein in his competitive intensity due to recurring injuries in his early years on the circuit.

Mark Allen, “The Grip,” the greatest triathlete in history and an early adopter of aerobic heart rate training, climbs the infamous “Beast” on St. Croix, a 1,000’ ascent in one mile. He remained aerobic for the entire climb…NOT!

In consultation with Maffetone, Allen addressed his metabolic condition of aerobic deficiency and anaerobic excess by patiently conducting all workouts at or below his maximum aerobic heart rate of 150 beats per minute for several months. At first, the experience was almost laughable. Allen had trained at such a high intensity for so long that he found he had to slow to a walk during routine training runs to avoid the dreaded beeping of the watch.

Grip was a fine-tuned, world champion anaerobic machine, but he could not even break eight minutes per mile pace when training aerobically. Allen stayed the course and built the biggest, most efficient engine ever seen in the triathlon world. His aerobic pace, measured in regular Maximum Aerobic Function (MAF) tests we’ll describe shortly, steadily dropped from the eights down to a phenomenal 5m:10 per mile for a five-mile test at the same heart rate—150 beats per minute.

Naturally, Allen’s progress came without the injury, illness, and burnout land mines that come from an anaerobic-based program, and dramatically improved his performance in the ultradistance events where the ability to burn fat and spare glycogen is even more relevant than in a two-hour Olympic distance triathlon. In Allen’s famed “Ironwar” duel with Dave Scott at the 1989 Hawaii Ironman, he recorded an astounding 2h:40 marathon split en route to his first of six victories. This is after swimming 2.4 miles, cycling 112 miles, and then running in the oppressive afternoon heat of the lava fields of Kona. Allen’s marathon split remains the race record a quarter of a century later.

Because Allen was able to preserve his health with a lower stress aerobic-style training approach, he was able to extend his career and go out on top at age thirty-seven. In his very last race, the 1995 Ironman, Allen came back from 13.5 minutes behind on the marathon, the biggest deficit in Ironman history, to beat twenty-six-year-old German rival Thomas Hellriegel for his sixth Hawaii world title.

Here, at a glance, are seven key elements that summarize the Primal Endurance approach:

1. Sleep: Yes, sleep is number one—the next frontier of performance breakthroughs in all sports, especially endurance sports. Your athletic pursuits require you to sleep significantly more than if you weren’t training. Reject conventional wisdom’s “eight hours” recommendation and individualize your approach, honoring these two maxims: minimize artificial light and digital stimulation after dark; and awaken each morning, without an alarm, refreshed and energized. If you are training more, sleep more. If you can’t honor the aforementioned maxims, stop training until you can. If you fall short of optimal sleep one day, take a nap the following day—instead of your workout! More on this topic in Chapter 8.

2. Stress/Rest Balance: Primal-style endurance training allows you to reach for higher highs (breakthrough workouts) and observe lower lows (more rest, shorter, easier recovery workouts, and staying below aerobic maximum heart rate at the vast majority of workouts). This appeals to your competitive intensity by focusing on peak performance and recovery, instead of focusing on the flawed notion of “consistency” in this context. Furthermore, realize that virtually all athletes, from novice to elite, do too much training and not enough rest. Consider backing off on both your mileage and your intensity, and adding more sleep, recovery, and complementary practices.

3. Intuitive and Personalized: Your training schedule is sensible, intuitive, flexible, and even spontaneous instead of regimented and pre-ordained. Respect your daily life circumstances, motivation levels, stress levels, energy levels, immune function, and moods. This means backing off when tired, but also pursuing breakthrough workouts when you feel great! Experimentation is necessary to dial in the best approach that works for you, and entails some trial and error. Also, what worked for you last year may not work in the future, so be open to flexibility. The top priority is to enjoy your program and feel confident that it works well for you.

4. Aerobic Emphasis: Endurance success is primarily dependent on aerobic efficiency. Aerobic base building delivers by far your best return on investment, and is best achieved by strictly limiting heart rate to aerobic max or lower during defined aerobic workouts and training periods. Stay out of the black hole, and don’t venture into high-intensity training blocks before you have a strong base.

5. Intensity Structure: Intensity can deliver exceptional results for endurance athletes, when a strong base is present, when workouts are brief in duration and really intense, when they are conducted only when you are highly motivated and energized, and during defined periods that are short in duration and always followed by a rest period and preceded by an aerobic period.

6. Complementary practices: Increased general daily movement, spontaneous, unstructured play sessions, mobility work such as technique drills and dynamic stretching, movement practices like yoga and Pilates, and high-intensity strength training are essential for success, because we live sedentary lives of extreme physical ease. Remember, in endurance competitions, you have to “endure.” Cranking out your daily hour-long workout and then sitting at a desk, in a car, and on a couch the rest of the day is not preparing you to endure anything except perhaps a beatdown on the race course at the hands of a more well-rounded athlete! Expand your perspective to embrace total fitness and an active, energetic lifestyle.

7. Periodization: An annual program always commences with an aerobic base period (minimum eight weeks). With success, high-intensity periods can follow, with a maximum duration of four weeks. Intensity periods are followed by micro periods of rest, followed by aerobic, followed by a return to intensity/competition. The annual program always ends with an extended rest period or off-season, followed by a new macro aerobic base period to commence a new annual program. This overview offers plenty of flexibility, but you have to respect the need to engage in blocks of specific training focus as an immutable law of endurance training.