The cortisol showerhead has an assortment of settings to support your peak performance and longevity goals.

As you pursue endurance goals in hectic modern life, it might be helpful for you to envision a reservoir residing in your body that stores the precious fight-or-flight hormone cortisol. You were born with this tank, and your genetics have a big influence on the size of your tank, how easily it is depleted, and how efficiently it is refilled. However, like other genetic attributes influenced by environmental signals, you have tremendous control on how you spend, save, or squander this precious resource that gives you heightened physical and cognitive performance on demand.

Imagine the cortisol is dispensed though one of those super-deluxe showerheads with numerous adjustment options. You have everything from the full-blast power setting down to a fine mist. Just like with a real shower dispensing energized negative ion air particles and invigorating the nervous system, you get a pleasant boost of energy every time you turn on the nozzle. This cortisol showerhead analogy summarizes everything Mark and Brad have bantered about for the past twenty-seven years related to balancing training with recovery, balancing health while you pursue ambitious fitness goals, and, perhaps most profoundly, balancing peak performance ambitions with longevity.

A FAVORITE PRIMAL BLUEPRINT TAG LINE for weight-loss enthusiasts is that when you go primal, losing weight is as simple as having your hand on a dial. Dial back your total dietary insulin production, and you reduce body fat quickly. In this discussion, instead of a dial, your hand is on the showerhead, ready to adjust your spray option any time. How are you going to handle the tremendous power and responsibility that comes from controlling your showerhead? There are no right or wrong answers here. The NFL and NBA guys who play hard by day, club hard by night, and earn a lifetime fortune in a seven-year career probably wouldn’t have it any other way. Even many of the aged, crippled, cognitively declined football warhorses assert that their journey was worth it.

The desire to seize the day and pursue the limit of your human potential can be all-consuming, and it’s a gift to have a goal so compelling that you give your heart and soul to the effort every day for years and years. The elite Ironman triathletes training for six hours a day and jetting around the globe to drop the hammer for eight hours in competition might have a vague notion that they’re compromising their long-term health and longevity, but that doesn’t stop them from fulfilling their destiny. Ditto for the roadie going on an eleven-year run with Pearl Jam, or the associate at an elite law firm grinding for seventy-five hours a week to ascend to partner one day. Strike when the iron is hot, leverage years of methodical preparation, and unleash the highest expression of your talents during your peak years of productivity. This is the essence of the continued progress of humanity in every peak performance arena.

Most of us are presented with less extreme life path options than the all-consuming and health-challenging careers mentioned, but the question of how to best dispense the cortisol coming out of our show-erhead is no less relevant. There are many well-meaning folks who enter the world of endurance sports, become intoxicated by the low-hanging fruit (the endorphin buzz after vigorous workouts, the satisfaction of the finisher medal), and proceed with all manner of wickedly imbalanced, ill-advised approaches. What happens at first, due to the dynamics of how the spray nozzle affects your body, is they succeed. They might have a two-year ride, or a five-year ride, but eventually the repercussions of an imbalanced, overly stressful approach start to accumulate. It seems that the endurance scene today is booming like crazy, and is manifesting a very high attrition rate; one that will continue to climb unless the masses radically change their approach to get the spray nozzle moderated. Perhaps not many people care about attrition risks. The people who traffic in event production, energy gels, running shoes, or triathlon wetsuits are happy to lure fresh blood into the game each year, and it’s certainly not their obligation to advocate for the long-term best interests of their customers.

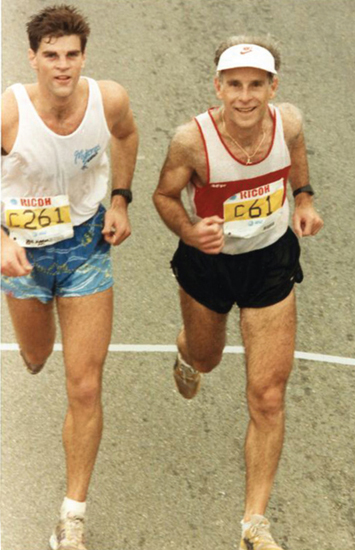

After discovering running later in life, “Runlike” Ron Kobrine completed thirty consecutive Boston marathons, spanning from 1980 to 2010. His best time in the string was 2h:54. He’s pictured here in 2004, surrounded by family members each adorned with a commemorative Ron Kobrine 25th Boston Marathon T-shirt.

If you care about your longevity in endurance sports, and longevity on the planet, you’ll want to do the best possible job managing your spray nozzle. This will enable both the actualization of your potential with challenging, appealing, and appropriate life goals, as well as the preservation of your health and longevity through the judicious balancing of stress and rest. Along those lines, it’s important to recognize that there are significant differences among individuals in work capacity, stress tolerance, athletic potential, and preferences for just how much stimulus and excitement one wants to take on over the course of life. It’s critical to spend a little time figuring out where you stand on the spectrum, and honor your particulars with your lifestyle decisions.

What athletic challenges are most appealing to you, and fit most conveniently with your other lifestyle circumstances? Set yourself up for success before you even think about workout particulars or race strategy. Get your attitude straight so you don’t get unnecessarily stressed about your results, peer pressure, or adhering to a consistent regimented workload.

Take inspiration from athletes who manage their spray settings expertly, enjoying not only peak performance but comprehensive, long-lasting health and happiness. For example, let’s meet Brad’s high school running mentor, “Runlike” Ron Kobrine, a father of his star teammate Steven, who set the tone with a tremendous work ethic on the road, while leading a balanced life as a finance executive and father of five. Among many distinctions, Ron completed the Boston marathon thirty years in a row, a longevity record that seems unfathomable in today’s age of epidemic running injuries and burnout.

Unlike many who pursue longevity streaks for the sake of the streak, Ron’s approach was from the opposite angle. “The Boston streak was something that just happened; I didn’t plan it. I enjoy running and the social connections of running, and things just became habit after a while. The Boston Marathon is a beautiful race in a beautiful city, so of course I signed up every year,” explains Ron.

Ron finishing the Los Angeles marathon with his son “Doctor” Dave, a former UCLA basketball player and Hawaii Iron-man finisher who inspired Brad to pursue triathlon, instead of basketball.

Indeed, the social aspects were central to Ron’s motivation and enjoyment. His son Eric accompanied to him to Boston each year (Eric has a twenty-year Boston finishing streak going himself!), and his other children frequently joined him to watch or run Boston over the years. He was surprised by a knock on his hotel room door the night before his twenty-fifth Boston Marathon, in 2004—it was his daughter and three other sons. Ostensibly, they where there to cheer him on, but he learned otherwise while watching a television interview where Steven informed Boston viewers that each Kobrine had secretly trained and qualified over the previous year to gain official entry into the race.

Social and unstructured as he was, Ron did not fool around on the racecourse. He was good for a ballpark three-hour performance for the first fifteen or twenty years (with a best of 2h:54), before finally allowing himself to gradually get slower in the latter years. After all, he didn’t discover running until his early forties, so his Boston performances came between the ages of forty-three and seventy-three.

Ron is nonchalant about his running accomplishments; everything is framed as ordinary and routine. He doesn’t keep any records and didn’t much care about the details at the time, either. Remember, his career predated the modern hyped era of endurance. There are no Boston marathon tattoos on his body, no “BSTN 30” vanity plates on his ride, and no Facebook posts to his fan base during the streak. His motivating force was personal satisfaction, and the camaraderie of a small, close-knit group of training partners and family members.

He even explains away his high-caliber performances with a shrug: “Running fast was just part of the culture in that day. The qualifying standards at Boston were so rigorous [3h:10 as a forty-plus runner from 1980 to 1990; then they adjusted up five minutes for every five-year age bracket] that you were compelled to run fast if you wanted a place on the start line. If ten of my training buddies and I [Ron was part of a large and notorious pack of 5:30 a.m. runners in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles] went to a 10K, we would all break forty minutes. But I didn’t train with any methodical plan or strategy. If I felt great, I’d go long and hard. If I felt tired or sore, I’d take it easy. It wasn’t a complex approach. I remember I was interviewed once by Boston television and they asked, ‘How long does it take you to get ready for a marathon?’ I didn’t even understand the question!”

Make no mistake, Ron relished the competitive aspect of his journey, but his tangible performance goals were never put before the purity of the experience. This is likely why he never missed the Boston starting line due to injury or illness. Ron simply followed his passion where it led, rather than forcing the issue. If it’s possible to convey this to you with a straight face, Ron took a “low stress” approach to running thirty consecutive Boston marathons, and set himself up gracefully for future decades of robust health, gentler exercise habits, and more modest fitness goals. The distinction is critical because we get so wrapped up in the importance of our goals, or in comparisons to others (he’s called Runlike Ron because no one else can…) that we apply an overly stressful approach and bomb out.

Today, at seventy-eight, Ron has gracefully transitioned to walking as his main exercise, and he enjoys lengthy daily walks along the beach near his home in Northern California. No drama here: after battling a couple of health problems a few years back, he emerged from convalescence walking instead of running, and just never felt the inclination to return to running. Ron explains, “Upon reflection, I realize that my life in retirement is much simpler and calmer, so I don’t need the running like I did when life was busier. Running was a form of meditation for me; it helped me clear my head and balance the assorted stresses of building a business, raising a family, and managing the faster-paced life in my younger years.”

Ron’s approach and perspective seem healthy and balanced, but the fact remains that running over a hundred marathons—the vast majority of them fast marathons!—requires a tremendous commitment to decades of extremely hard training—a significant amount of spray coming out of the tank. However, Ron’s healthy perspective and process-oriented approach clearly helped ease the stress impact of his thirty years of phenomenal dedication to fitness. It’s reasonable to speculate that he likely didn’t need as much spray as an amped-up, results-obsessed competitor trying to achieve the same feats.

While thirty years of Boston is a fine example of managing one’s spray settings deftly, how does an eighty-year athletic career sound? Let’s meet Brad’s father, ninety-three-year-old Dr. Walter Kearns. Dr. Kearns has played amateur golf at the elite level for over eighty years and continues to go strong as the premier golfer in the world over the age of ninety.

Since he’s still active at ninety-three, Walter has obviously had a life of exceptional health, enjoying many other sports and fitness activities in addition to golf. While he was never tempted to try anything extreme like a marathon, he dropped a handful of 10Ks back in the running boom days, coached his kids’ sports teams, and has kept himself tournament-sharp for decades. He was captain of the Princeton golf team as a youth, and qualified for the 1941 U.S. Amateur at age nineteen, and the U.S. Senior Amateur (ages fifty and up) at the age of sixty-seven in 1989. This forty-eight-year gap is believed to be unmatched in the history of national championship qualification.

Walter out for a quick few holes in the evening, with Gail, Quincy the ballfinder, and grandson Jack

Starting in 1989, when he shot a four-under 66 at age sixty-seven, he’s shot his age over eleven hundred times and counting (basically every time out in case disaster strikes; don’t smirk as you envision a ninety-three-year-old lamenting a miserable 94 on the scorecard). While no official rankings are kept in the ninety-plus category, it is very unlikely there are similar aged golfers in his stratosphere anywhere on the planet. Any challengers would be well advised to bring cash to the course. Walter can be counted on for a low 80s score any day, and will frequently post rounds in the 70s. On three occasions he has shot a stunning sixteen strokes under his age: a 71 at the age of eighty-seven, a 75 at age ninety-one, and a 76 at ninety-two (Guinness Book of World Records lists two folks shooting seventeen below as the record.) Oh, and he’s had eleven holes-in-one, including a barrage of seven in five years once he turned eighty.

At a recent round, Walter was complaining to his playing partners about his declining vision making it hard to follow his shots. One of them fired back, “Walter, the reason you can’t see your shots is because you hit the ball too damn far! Most ninety-three-year-olds see their shots just fine—ten feet off the ground.” Walter is referred to by everyone he encounters out on the course and elsewhere in life as a physical marvel or genetic freak. Obviously these sentiments are delivered as compliments, but the truth is not so simple. He’s made the most of his genetics for sure, having a lifelong devotion to healthy eating and exercise habits inspired by his career as a physician. But there are some additional critical insights in this story of longevity, pacing, and peak performance.

Walter is a very chill guy, period. He does not get emotional, harried, overstressed, negative, angry, or overexcited. He’s level and calm in the face of everything that’s come down his path in ninety-three years. Mark even tried to rattle his cage a bit by challenging his lifelong beliefs relating to conventional wisdom’s lipid hypothesis of heart disease. Walter played an important role in helping get the presentation about cholesterol in the Primal Blueprint book completely tight and medically verifiable. He was open to hearing an opposing view, and methodically did the reading and evaluations necessary to rethink his position and approve the message in the book.

Walter is all about pacing and balance. These characterizations are preferable to “moderation,” which can easily be misconstrued as, or used as license for, mediocrity. Shooting in the 70s at the championship-caliber Braemar Country Club is not a moderate golf round. Walter faithfully gets adequate sleep and downtime each day, however much he needs, no matter what. That’s a consistent nine to ten hours a night and a leisurely afternoon period of napping/reading quietly in a darkened room that ranges from at least ninety minutes up to three hours after a busy morning or a hot day on the golf course.

Walter takes the long, long walk to another bombed tee shot. Yep, lugging his own sticks in a junior bag. “Carts are for old guys,” says Walter.

Walter loves his golf outings, as you can imagine, but he’s careful not to overdo it. He’ll stay home if the temperature is below 50°F, or above 95°F. He’s perfectly content to play nine holes instead of eighteen these days, especially if the weather is less than ideal. He often makes this snap decision at the turn (the halfway point of the golf course) if he’s tired, hot, cold, or hungry… even if he’s standing at one over par—really!

Walter takes a Pilates class once a week with his super-high-energy wife, Gail, seventy-eight, a part-timer at Primal Blueprint who prepares the written summaries of our podcast shows, does book editing and metric conversions, and was enlisted at PrimalCon to push her Prius through the parking lot as part of a Primal Play workshop (search YouTube for “76-year-old lady pushes car”). Sometimes Gail is concerned that the Pilates teacher is pushing Walter too hard for his age, but extending yourself a bit once a week and allowing for full recovery seems like a savvy anti-aging strategy. Jack LaLanne’s fitness legacy was validated when he lived to the ripe old age of ninety-eight, and it’s possible that he could have gone much longer had he not pushed himself so hard his whole life with excessive exercise—seriously!

Again, there is no right or wrong way to use your showerhead. What we are talking about here is a trade-off between peak performance and seizing the day (the turbo-pulsating-massage setting) on one side, and longevity (the fine-mist setting) on the other side. If you do things the right way—pursue your endurance goals with a primal-aligned, stress-balanced approach—these two goals don’t have to be diametrically opposed. Energy is a renewable resource in the body, so an active, exciting, adventurous lifestyle can beget more energy and vibrant health. However, when your approach is flawed—either logistically or psychologically—peak performance and longevity can indeed be diametrically opposed. You are indiscriminately blasting the showerhead, enjoying the short-term peak performance boost from the all-powerful fight-or-flight response, but draining the tank—one you’ll be needing for a lifetime—irresponsibly.

Sometimes severely abusing the spray nozzle causes it to jam up and shut off without warning, as discussed with the “Running on Empty” ultrarunners in Chapter 9. Article author Meaghen Brown reports that a pattern appears among the athletes studied: a steady progression to the top lasting around two years, followed by a sudden crash, with an assortment of disturbing symptoms that thoroughly confuse even the most informed physicians.

Hopefully you can keep the image of the spray nozzle in the back of your mind as you plot your future course as an athlete, and as a healthy person in general. As with the ultrarunners and many other extreme performers, you can crank up the intensity of the spray whenever you want and demand great achievements from your body, imbalanced as your approach may be. But be mindful that you are under the influence of this magic spray that has the capability to mask fatigue and distort your decision-making abilities in the process.

In conclusion, Primal Endurance gives you the go-ahead to go sign up for those ambitious goals of yours, whether it’s a 70.3, a fifty-kilometer trail run, or a bike tour down the west coast of the USA. But try to adopt a chill approach, like Ron or Walter, and don’t get too worked up when things go wrong, or when they go well. When you ask the maximum from your mind and body for athletic excellence, understand the consequences of your performance demands. Notice the times when you are cranking up the spray nozzle to the turbo settings, and resolve to include the necessary downtime to balance extreme peak performance demands. This might mean implementing a pattern of skipping a year of competition after two or three consecutive years.

Brad’s friend “Mellow C” likes to unplug and retreat to this tiny lake-side cabin for a spell when life gets a little hectic. Departing from one’s training routine, even briefly, is a novel concept for many endurance athletes—what with the ever-present fears of getting out of shape or losing the feel for the water.

If an endurance enthusiast landed at such a cabin by chance, their initial thoughts might be, “Open water swim!” or “Any trails around?” Have the courage and the confidence to trust the natural process of fitness, and the tremendous contribution that rest and balance offer to the equation.

Perish the thought of missing out on something, but a year away from the race course, or at least a year pursuing an alternate, perhaps less encompassing, goal, will surely recharge your batteries; provide relief from competitive pressures; give you a chance to emphasize complementary movement, mobility, and lifestyle practices that often get pushed aside in favor of bread-and-butter mileage obligations; rekindle your enthusiasm and appreciation for core competitions when you return to the race course; and finally, give your cortisol tank a chance to refill a bit.

In the academic world, they call this a sabbatical, a tradition that exists for a very important reason. Sabbaticals give educators a chance to broaden their horizons and bring more energy and excitement back to their students and their research. Ditto for those in other fields requiring creativity, innovation, enthusiasm, and clear thinking—which covers just about everyone. In Mosaic law, a sabbatical, or Sabbath, was mandated every seventh year, where normal activity was ceased and “the land was to remain untilled and all debtors and slaves were to be released.” This edict is thousands of years old, but any farmer today knows that leaving land untilled for a year allows it to rest and rejuve-nate, and any endurance athlete knows that being a slave to the training log is no fun. So try leaving your land untilled and give the spray nozzle a break now and then. A sabbatical year is a great idea for a serious, long-term competitor, but you can take sabbaticals of a week or month any time you want with great benefit.