7 Make Your Content Influential

Is your content compelling for your customers?

INFLUENCE IS THE NEW POWER—IF YOU HAVE INFLUENCE, YOU CAN CREATE A BRAND.

—Michelle Phan, YouTube personality

THE FORCE WILL BE WITH YOU. ALWAYS.

—Obi-Wan Kenobi

When you make your content effective, you earn the opportunity to influence your customers. Your content becomes like the Force in Star Wars. If you master it wisely, you can have a powerful positive impact. How can you make the most of that opportunity? Principles from rhetoric and psychology can help. Let’s walk through these principles and techniques to apply them to your content.

Rhetoric: The Study of Influence

Despite its practical value, rhetoric is a lost art. We don’t learn it in school, especially in the United States. (I didn’t come across the topic much until graduate school.) Even worse, rhetoric is sometimes mistaken for a dark art. Politicians abuse it by making empty promises or hijacking our attention. Let’s move forward by looking back at what the ancient Greeks (and other smart rhetoricians) actually had in mind.

The philosopher Aristotle defined rhetoric as figuring out the best way to persuade in a situation. Today, Andrea Lunsford, a respected professor at Stanford University, defines rhetoric as “the art, practice, and study of human communication.”1 Over thousands of years, smart scholars and practitioners have debated the theory and scope of rhetoric. I’ve distilled many of the useful ideas from that debate into two principles for content.

NOTE: For even more principles, check out Appendix A.

The Tried-and-True Three Appeals

What’s the number-one principle of rhetoric? Aristotle would say it’s not one but three: the persuasive appeals. He introduced them in Rhetoric as ethos (credibility), logos (logic), and pathos (emotion).2 This trio has shaped notions of persuasion ever since.

Aristotle insisted on always combining these appeals. First, let’s turn to credibility.

Credibility: Why Customers Should Listen to You

Speak when the wise Yoda does, listen people do. (See what I did there?) Yoda has not only a distinct style but also credibility. This appeal focuses on why people should trust and listen to you or your organization. Typical points of credibility include

Experience: You have a lot of it, or your experience is specialized.

Success: You’ve achieved something important or are having success now.

Reputation: People in the community know you as having a certain characteristic, expertise, or offering.

Endorsement/association: A credible brand or person says you are credible or connects with you in a credible way.

Certification: You have earned a certain security or achievement level.

Longevity: You’ve been around for a while.

Similarity: You have a lot in common with the users.

The less people know about you, the more you need to prove your credibility. In turn, when you’re established, sometimes you need to prove that your credibility is still relevant. The trick is to convey your credibility without making people yawn or think you’re boasting. So let’s look at how content can show your credibility in today’s digital world.

Quality Content Over Time + Signature Content Types

You’ll build a reputation as a trusted resource if you publish consistently good content over time. It’s like being the person who reliably says something useful. What’s even better? Becoming known for a particular approach to content.

Reviews, awards, and other recognition: Focus on useful praise from sources your customers know and value.

Quotes: Pick quotes from people your users respect and can relate to. If you’re not a media property, business partnerships or alliances serve a similar purpose.

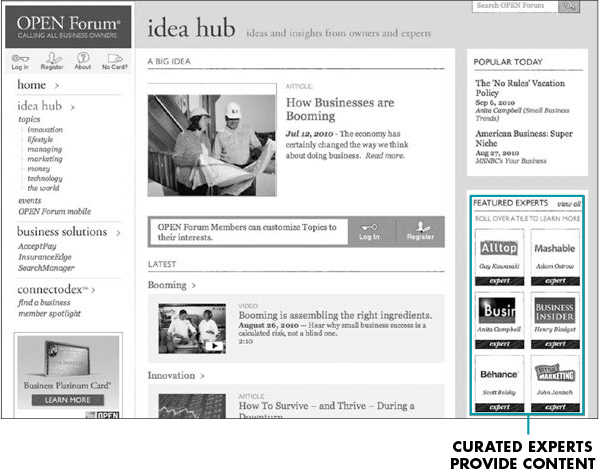

Expert contributions: If a respected expert contributes content to your website, you gain credibility. In turn, if you’re invited to be the expert contributor, you gain credibility. American Express Open Forum, a knowledge center for small businesses, offers content from their own experts as well as from outside thought leaders.

Curated content from credible sources: Curating content is showcasing good content in a unique way. When you curate content from credible sources, you enhance your own credibility.

References: When you ground your facts with references, you not only ensure you’re telling the truth but also align with credible sources.

Brand, organization, or product history: Sometimes, your organization or product has a rich and relevant history. The original Mini Cooper, for example, was designed to offer less expensive and more efficient transportation in the 1960s. Mini Cooper’s website makes that story pertinent to today’s environmental concerns.

Security and privacy cues: When you ask people to share personal information, you need to show that your website is safe by displaying lock icons, security certifications, or similar cues. Provide easy access to your privacy policy or terms and put them in plain language.

Now let’s turn to the second appeal, logic.

Logic: Your Argument

It’s whether your reasoning is formed well (also known as being valid). If logic were a Star Wars character, it would be the matter-of-fact C3P0. At a minimum, good reasoning comprises these key elements:

Claim: What you assert to be true, such as a value proposition.

Evidence: What supports your claim, such as facts, statistics, and testimonials.

Warrant: Why you can make the claim based on the evidence, or your “leap in logic.” Sometimes, the warrant is implied because it is an assumption (or a set of assumptions).

Your argument generally is good if

Your claim is likely true when your evidence is true.

Customers can understand the warrant quickly.

As a simple example, REI claims it is the first US-based travel company to become 100 percent carbon neutral. The evidence is that REI buys credits to support renewable energy (such as solar and wind). The warrant is that the renewable energy work neutralizes carbon emissions, so buying those credits compensates for REI’s emissions.

Even if you form solid logic, your customers make or break it. Users must accept your evidence as good evidence. For example, REI emphasizes that it buys energy credits from the respected Bonneville Environmental Foundation. Your customers must also have enough in common with you to understand the assumptions. In the case of REI, their customers tend to care about the environment, and people who care about the environment are likely familiar with carbon credits.

Often, the more you ask of people’s time or money, the more evidence you’ll need to offer. Many people spend more time researching to buy a car than they do to buy driving gloves, for instance. That’s why AutoTrader.com offers not only car advertisements but also a wealth of content with which to research features, performance, expert opinion, and more.

While most web content involves at least some reasoning, certain content types lend themselves more to articulating an argument:

Blog posts

Media articles or editorials

Expert reviews

Product or service descriptions

White papers, fact sheets, or reports

Interviews

In addition, certain content types make good evidence to support an argument:

Charts, graphs, and data visualizations

Testimonials, case studies, and similar stories

Avoid These Argument Mistakes

For airtight arguments, don’t let these mistakes (also called fallacies) bubble up in your reasoning:

Generalizing hastily, or drawing a conclusion based on an odd example (edge case) or a very small set of examples. Example: Search engine optimization (SEO) will double all companies’ website traffic because SEO doubled one company’s website traffic.

Distracting with a red herring, or making an emotionally charged point that isn’t relevant. Example: We should spend half of our interactive budget on SEO, unless we want our competitors to trample us like they did on that customer satisfaction survey.

Confusing cause with correlation, or claiming that one event caused another only because the events happened at (or close to) the same time. Example: My company hired an SEO expert, and the next day my dog died. Hiring the SEO expert killed my dog.

Of course, identifying correlations can be valuable, as we have found in our research of content effectiveness. It’s helpful in planning your content approach to know that if customers have trouble finding your content, the content will not be as effective, even if we do not yet know the detailed, scientific cause for this correlation. The danger is in overstating correlation in a way that leads to faulty conclusions.

Sliding down the slippery slope, or exaggerating that a situation will lead to a catastrophic chain of events. Example: If you don’t spend lots of money on SEO, then you’ll lose all of your prospective customers, and then your sales will plummet, and then the global economy will weaken, and then we will have political unrest that leads to nuclear war.

Jumping on the bandwagon, or relying only on the evidence that other people are doing it. Example: Your competitors are spending lots of money on SEO. You should too.

The first two appeals address mostly our head. Now, let’s address the heart with the appeal to emotion.

Emotion: Keeping Interest and Motivating Action

The emotional appeal is how you tap into people’s emotions to hold their interest, gain their sympathies, or motivate them to act. If this appeal were a Star Wars character, it would be Jar Jar Binks. Kidding. It could be a number of characters, but Princess Leia stands out with her hologrammed, passionate plea to Obi-Wan Kenobi for help.

Appealing to emotion involves these related elements:

Tone: The mood conveyed through your words, images, and other content.

Style: Vivid word choice or imagery that’s charged with emotion.

Let’s look at a simple yet clever example from MailChimp. Instead of a typical name, MailChimp calls one of its email plans “Growing Business” (Figure 7.1). What entrepreneur doesn’t aspire to grow?

Figure 7.1: MailChimp taps into emotion with the plan name “Growing Business.”

Content offers many opportunities to charm your customers’ emotions.

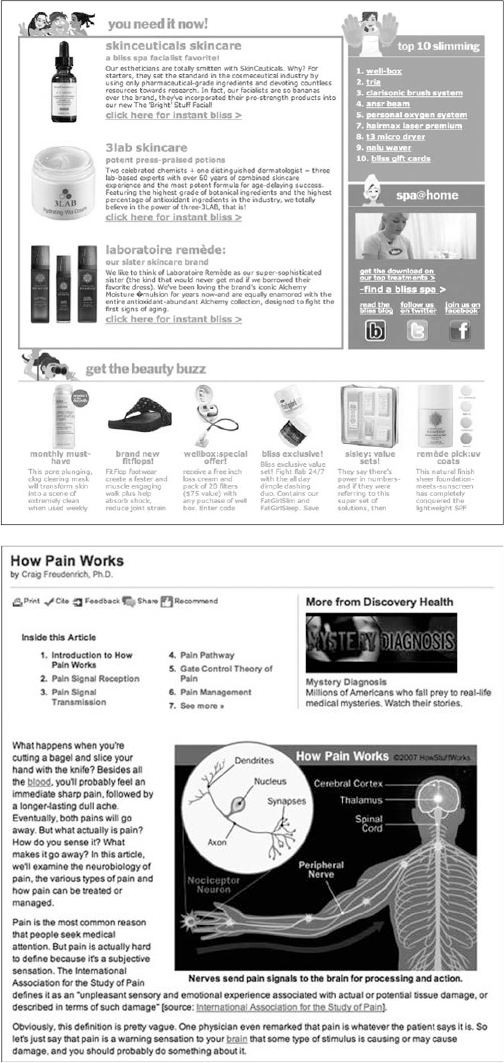

Voice

The personality or feel of your content. Two very different examples are Bliss and HowStuffWorks.com. Bliss is sassy, whereas HowStuffWorks is dissecting (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2: Bliss has a sassy voice, and HowStuffWorks has an analytical voice.

Sensory Detail

When you portray how things look, sound, smell, taste, or feel, you trigger people’s gut reactions. Lindt, for instance, describes how wonderfully chocolate engages all five senses, tempting a chocoholic like me (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3: Lindt uses sensory detail to evoke emotion.

Associations with Words and Images

Beyond their literal meanings, words and images stir up feelings (also called connotations). MailChimp tapped into this positive association with the word growing in one of its email plan names.

Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices are tools that enhance content emotionally. Following are some text examples, but you can apply many of these devices to images, video, or audio.

Hyperbole, or over-the-top exaggeration, usually meant to be funny. Example: I love quality content so much that I want to marry it.

Irony, or when the literal and intended meanings are out of sync; often intended to be funny. Example: You should publish the blog post that you paid someone $10 to write for you.

Simile, or comparing unlike things. Example: This stagnant content is like a cesspool.

Rhetorical question, or a question that creates a dramatic effect rather than asks for a literal answer. Example: Do we really want to keep creating terrible content?

Personification, or adding personality or human qualities to a concept or object. Example: The website regurgitated content from 1999 at me.

The principle of the three appeals will take you far in making your content influential. But you can make your content even more influential with the principle of identification.

Irresistible Identification

Identification is overcoming our differences to find common ground. It’s the key principle for helping you attract the right people. Rhetorician Kenneth Burke defined identification as “any of the wide variety of means by which an author may establish a shared sense of values, attitudes, and interests with his [or her] readers [users].”3 When users identify with you, they’re more likely to be drawn to you.

Identify on the Right Level

We connect with people who are like us on superficial and deep levels. We can identify quickly with people who appear to be just like us. People connect more intensely to people in a similar role or with like values, interests, and beliefs. Not everyone will identify with you or your company’s brand, and that’s okay.

To attract the right people, content can help in many ways.

Persona/Character/Spokesperson

It’s representing your organization with a person or character (or two or three) who relates well to your users. For example, HowStuffWorks offers a collection of podcasts hosted by relevant personalities. The most popular is Stuff You Should Know. On this podcast, self-proclaimed geeks Josh and Chuck banter about, well, stuff they think other geeks should know (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4: Josh and Chuck represent geekdom for HowStuffWorks.

User-Generated Content

Your users can represent you well. How? Through comments and content they contribute to your social networking space. The right potential customers will identify with your current customers. The trick is to facilitate the discussion so that it stays true to your brand and your users.

Cause Content

Another approach is to create content around a cause. Research from the public relations firm Edelman has found that supporting a cause could even inspire users to switch brands.4 Select a cause that fits your brand values and your users’ values. For example, REI devotes much content to environmental concerns (Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.5: The environment is a cause close to the hearts of many REI users and relates to REI’s brand as an outdoor outfitter.

In the United States, REI even turned the day after Thanksgiving, Black Friday, into a cause with the #optoutside campaign. Black Friday is now as much about being thankful for the outdoors as it is about shopping.

Story Content

Still another approach to identification is telling a story, or narrative. A story allows you to bring values to life in a memorable, even entertaining, way.5 Because a story often involves credibility, logic, and emotion, it makes a strong, influential impact. You can find a story in almost anything, but I find two types work well for practical purposes.

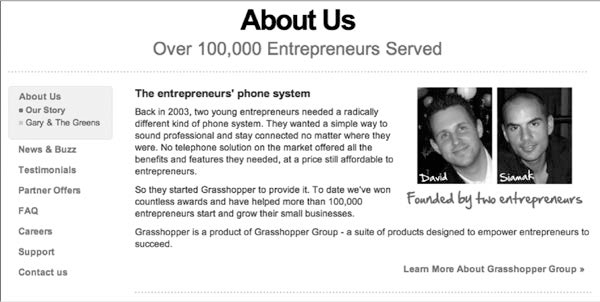

Brand/organization story: If you’re a startup, tell the tale of solving a tough problem or making a big change to help people. Grasshopper, for example, offers the concise but compelling story of its founding (Figure 7.6). If you’re more established, explore your history or the story of an innovation or accomplishment.

Figure 7.6: Grasshopper tells the tale of its entrepreneurial roots.

Client/customer case study: Case studies recount how you help your users. One approach is dramatization.

A different approach is to present actual customer stories. A series of iPhone videos, for instance, showcase real users explaining how the iPhone saved the day. In one, a pilot recalls how he looked up the weather on the iPhone to help his flight avoid a three-hour delay (Figure 7.7).

Figure 7.7: A pilot explains how the iPhone helped him.

Although Burke defined identification in the 1950s, I wonder whether he had a crystal ball that let him glimpse the 21st century. He felt that identification could happen within a short paragraph, in a long series of communications over time, and in everything in between. Every bit of content is an opportunity to strengthen identification. Now let’s turn to some principles from psychology.

Psychology: The Science of Influence

Scientific research tells us a lot about how we’re influenced. But we don’t learn about it in Psychology 101. The field’s piles of research, however, offer a wealth of insight into what influences our minds. For this chapter, I’ve selected two principles to feature.

NOTE: For more principles, check out Appendix A.

If I had to name a theme for these principles, I’d say it’s shortcuts. People don’t have the time and energy to research and think exhaustively about every little decision, even if they’d like to do so. Often without realizing it, people rely on these principles as timesavers.

Framing: Guiding Attention

A frame is a set of expectations, values, and assumptions that acts like a filtering lens. It leads us to see certain details and not others. As a simple example, let’s say we’re working with a project manager and a creative director. We have certain expectations for each role. If the project manager didn’t create a project timeline, we’d notice and probably complain. If a creative director didn’t create a project timeline, however, we probably wouldn’t notice.

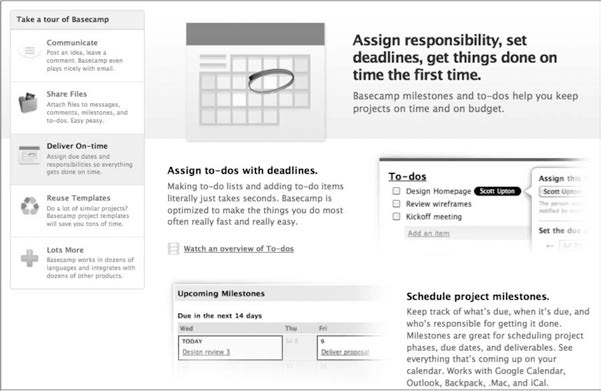

Framing is packaging an idea, issue, or choice in terms of the frame. Framing can lead people to understand a concept quickly and even favorably. For example, if we describe an idea to a project manager, we might stress that it saves time, avoids rework, and increases efficiency. In fact, that’s exactly how 37signals talks about its project management software, Basecamp (Figure 7.8).

Figure 7.8: Basecamp taps into a project manager’s frame of reference.

People will respond to the same choice differently when it is framed in different terms. Research suggests that a negative frame, especially describing a “loss,” prompts a powerful emotional reaction in people.6 It’s so strong that people will even make a risky choice to avoid feeling the loss. The book How We Decide, by Jonah Lehrer, describes it this way:

This human foible is known as the framing effect… the effect helps explain why people are much more likely to buy meat when it’s labeled 85 percent lean instead of 15 percent fat. And why twice as many patients opt for surgery when told there’s an 80 percent chance of their surviving instead of a 20 percent chance of their dying.”7

Negative frames aren’t always bad. They simply spark a lot of emotional brain activity, so they’re like playing with fire. Consider these statements:

If you improve your SEO, you will gain 5000 new customers each year.

If you do not improve your SEO, your company will lose 5000 new customers each year.

From a framing perspective, the second statement is more explosive. So be extra careful with negative frames. Save them for points that deserve urgent attention and a strong response.

Related to framing, priming is another subtle way to get people’s attention. It means introducing words, images, or ideas now to influence people’s choices a little later. For example, asking people the day before an election whether they intend to vote can increase the chance they’ll vote by up to 25 percent.8 The reason priming works is that we tend to act on what we remember easily.

To kick priming up a notch, you can address how to act on the choice. In the voting example, if you also showed people a map pointing out where they should go to vote, you’d further boost the chance they’ll vote. As Richard H. Thaler says in Nudge, “Often we can do more to facilitate good behavior by removing some small obstacle than by trying to shove people in a certain direction.”9

Let’s look at some specific ways to apply framing to content.

Theme/Key Messages

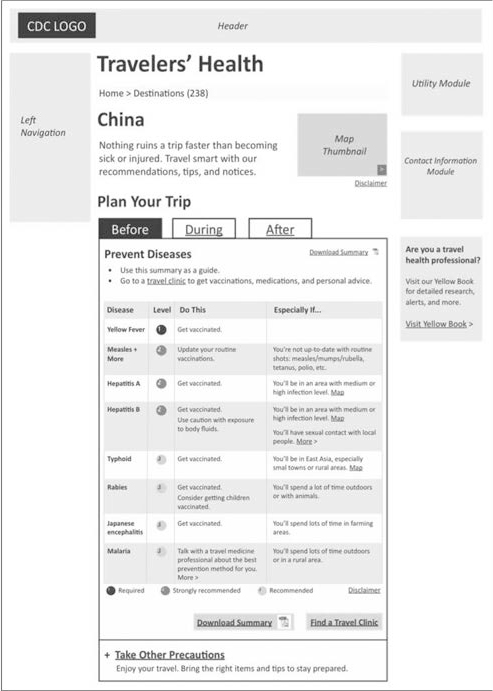

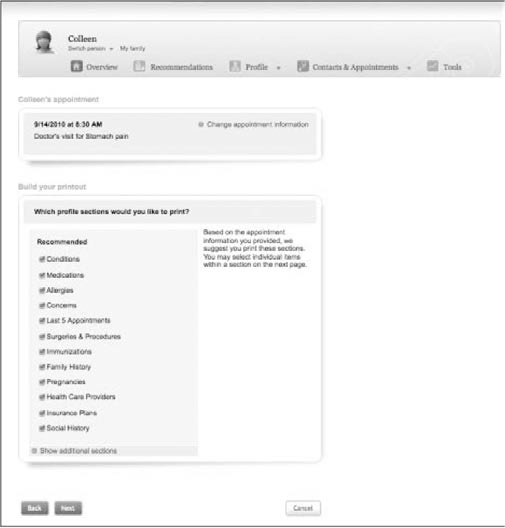

When Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) decided to redesign its Travelers’ Health website (mentioned in Chapter 4), I advised on an approach to the content. CDC wanted to convey the risk that travelers face so that they take the right precautions—but not to the point that people fear traveling. One recommendation I made was to frame the travel precautions as smart planning to ensure that business remains productive and that vacations stay fun. You can see a rough concept of this approach in Figure 7.9.

Figure 7.9: Positive key messages convey that travel precautions are important but not scary.

Curation

For years, Starbucks has curated music that reflects its brand and cultural perspective. Starbucks created its unique frame of the musical world, and the frame resonated with customers. Starbucks even released its own successful CDs and sponsored a satellite radio channel. Now that Starbucks offers free wireless internet access to customers, the coffee brand has released its own digital network. On it, Starbucks curates exclusive content from the New York Times, Apple, and other select publishers.10 This network is Starbuck’s frame of the digital world.

OPEN Forum by American Express uses curation to frame the digital world for small businesses. Specifically, the Idea Hub features content from select business owners and industry experts about pertinent topics (Figure 7.10).

Figure 7.10: American Express curates quality content for small businesses.

Claim and Evidence

The way you state a claim and the evidence you choose to support the claim is an opportunity to use framing. For example, the website for the personal genomics and biotechnology company 23andMe frames sharing your DNA results with researchers as an opportunity to be a part of something bigger. The company supports this claim with a range of compelling evidence that illustrates just how big in scope, meaning, and impact. This positive framing of the claim and evidence has convinced thousands of people to opt into sharing their DNA information with the 23andMe research network.

Reminder and Instruction

Is your body mass index healthy? Is it time for your kids’ shots? When did you last visit the dentist? What does your insurance cover? Your family’s health information adds up to a lot of content to manage. Electronic health records (EHRs) have potential to get it under control. Imagine Mint.com for your health.

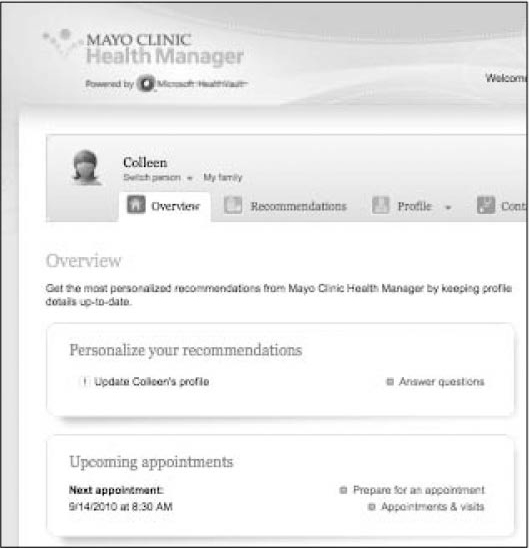

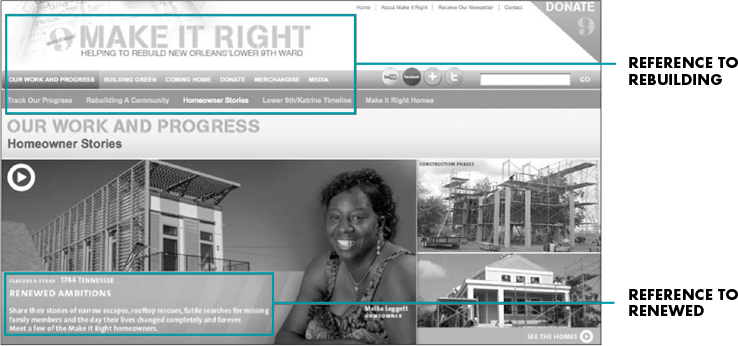

One benefit of EHRs is that they remind us to keep up with healthy behaviors, such as keeping our checkup appointments. Although no longer available, I will always like the way Mayo Clinic Health Manager highlighted upcoming medical visits on its dashboard. What would make this reminder even better is an option to receive it via email or text (Figure 7.11).

Figure 7.11: An EHR reminds me of an upcoming medical appointment.

And the Mayo Clinic Health Manager offered a wizard to guide you through preparing for a medical appointment. One of its features is that it compiles relevant sections of your personal health content so that you can bring it or send it to the doctor (Figure 7.12).

Figure 7.12: An EHR helps me get ready for the medical appointment.

And of course, other great examples of reminders and instruction have emerged in health and financial services. The Fitbit mobile application provides excellent examples of status updates, reminders, and instructions. The Capital One mobile application offers succinct and pertinent instructions and reminders for managing a credit card and more.

Reminder and instruction matter beyond electronic health records too. In the Travelers’ Health project I mentioned, we paid close attention to instruction. Research had shown that travelers were confused about where to get travel immunizations. The best place to get them is a travel health clinic, not a personal physician. My content recommendations stressed going to the travel health clinic and suggested ways to make finding travel clinics easier. This approach tested well with users11 (Figure 7.13).

Figure 7.13: In this concept for the Travelers’ Health website, I planned for better instruction to prepare travelers for getting vaccines.

Clearly, framing is a powerful and versatile principle for making your content influential. I’d like to share one more principle to consider for your content.

Metaphor: A Tie that Binds

Metaphor isn’t just that pretty language that makes a comparison, such as “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”12 It’s more, as psychologists and linguists have learned. Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker says, “Metaphor really is a key to explaining thought and language.”13 More specifically, consumer psychology experts Gerald Zaltman and Lindsay Zaltman say that metaphors are “basic categories of patterned thinking and decision making.”14 Metaphors are the way we think and talk about our world. The Zaltmans even think that metaphors resonate more deeply than archetypes, a staple of marketing strategy (see the following sidebar).

Tactically, metaphor often connects new or abstract ideas to something people already know. This connection helps people understand the ideas faster. That’s especially helpful for technology, which changes quickly. Interaction design expert Dan Saffer has even said, “Everything one says about the computer is metaphor.”15 For example, when internet use spread in the late 1990s, the term “web page” described a website screen in terms of something familiar—a paper page. It’s not really a page, though, so academics wanted to call a website screen a “node.” Which term caught on?

Use Metaphors Sparingly

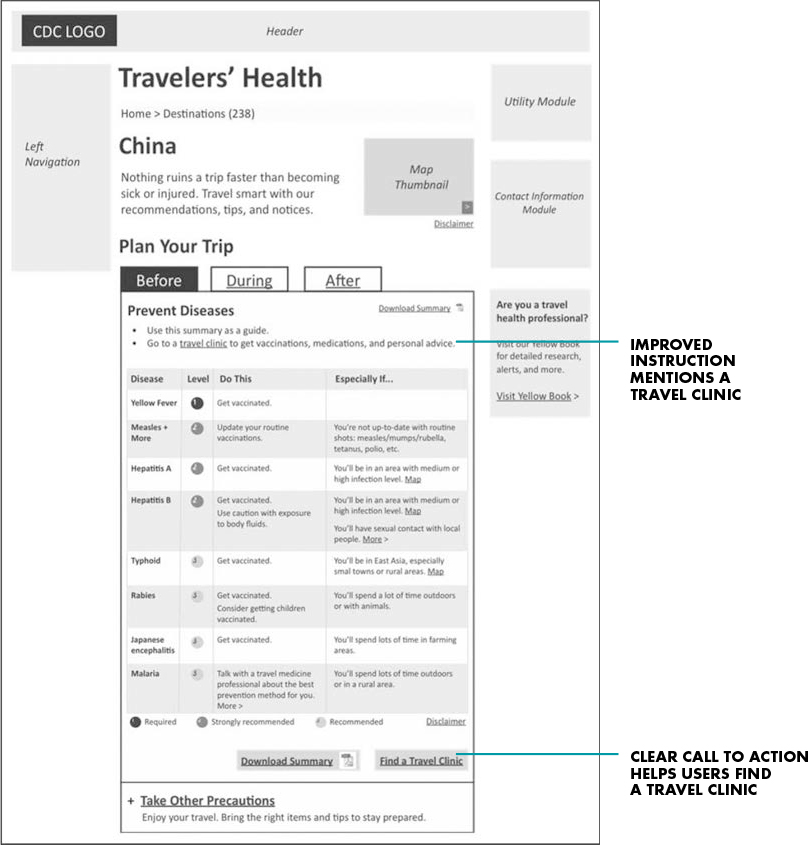

Psychologists and English professors agree that less is more. If you use too many metaphors, you risk confusing people. Focus more on selecting the right metaphor and reinforcing it in different ways. For example, the name Make It Right for a foundation suggests restoring or returning to balance. The website’s references to rebuilding and renewal subtly support the metaphor (Figure 7.14).

Figure 7.14: The Make It Right Foundation uses metaphor subtly but effectively.

Build on Metaphors People Already Use

Metaphors are vital to how we think and talk, and your users use them to describe their needs and your industry. As you research and communicate with your current users—or with the users you want to attract—take note of the words and phrases they use. When it comes to the complexities of finance, for example, people might feel “stuck” or eager to “turn over a new leaf” or ready for a “fresh start.” The personal finance service Mint.com taps into that metaphorical language brilliantly with its name alone, which suggests

Herbal leaf known for its fresh smell and taste

Source of new money

The name also happens to be short for the original name, Money Intelligence. (We should all be so lucky with our abbreviations.)

Apply Metaphor to Content

We can use the mighty metaphor almost anywhere in our web content to make us memorable and likable. Here are a few examples.

Name, Message, Call to Action

As the name implies, Designzillas humorously compares its web design agency to the Japanese monster (and sometimes hero) Godzilla. The agency sticks to this single metaphor throughout the concise site with copy and graphics (Figure 7.15).

Figure 7.15: Designzillas draws on one metaphor consistently.

This metaphor will make you laugh with messages and calls to action such as

Is your website stuck in the stone age?

We keep our clients on top of the food chain.

Our agency has evolved into fire-breathing web designers.

We are black belts in web-kwon-do.

Call us today! We don’t bite.

While funny and creative, this metaphor also positions Designzillas as a supernatural hero ready to rescue a client in need. That positioning taps into a deeper metaphor of transformation (see the sidebar “Research-Proven Metaphors”).

Organization Story

Heroic metaphor is also prominent in the story of Adam and Eric, the founders of Method home care products. The story compares the founders to accidental superheroes (Figure 7.16).

Figure 7.16: Metaphor equates Adam and Eric to superheroes.

The founders are quick to tell you that they’re no heroes. And that’s true. They’re SUPERheroes. And like every great superhero, they gained their powers after being exposed to toxic ingredients. Cleaning supplies, to be precise. But rather than turning them green or granting them the ability to talk to fish, Eric’s and Adam’s toxic exposure gave them something even better. An idea.

“Eric knew people wanted cleaning products they didn’t have to hide under their sinks. And Adam knew how to make them without any dirty ingredients. Their powers combined, they set out to save the world and create an entire line of home care products that were more powerful than a bottle of sodium hypochlorite. Gentler than a thousand puppy licks. Able to detox tall homes in a single afternoon.”

By now, you might have a lot of ideas for creating and curating effective, influential content. You’re ready to make your content a force for good. Now is the perfect time to figure out how you will assess whether your content is working. That means it’s time to plan content intelligence.

References

1 Andrea Lunsford, stanford.edu/dept/english/courses/sites/lunsford/pages/defs.htm

2 Aristotle, Rhetoric

3 Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives (University of California Press, 1969)

4 “The 2017 Earned Brand Study,” edelman.com/earned-brand

5 Colleen Jones, “Become an Interactive Storyteller” imediaconnection.com/content/18041.imc

6 Jonah Lehrer, How We Decide (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009)

7 Jonah Lehrer, How We Decide (Hougton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009)

8 Richard H. Thaler, Nudge (Yale University Press, 2008)

9 Richard H. Thaler, Nudge (Yale University Press, 2008)

10 Jennifer Van Grove, “How Starbucks Plans to Capitalize on Free Wi-Fi” http://mashable.com/2010/08/12/starbucks-digital-network/

11 Colleen Jones, Kevin O’Connor, “Testing Content” IA Summit

12 Shakespeare, Sonnet 18

13 Steven Pinker, The Stuff of Thought (Viking, 2007)

14 Gerald Zaltman, Lindsay Zaltman, Marketing Metaphoria (Harvard Business School Press, 2008)

15 Dan Saffer, “The Role of Metaphor in Interaction Design” slideshare.net/dansaffer/the-role-of-metaphor-in-interaction-design