9 Secrets to Using Content Intelligence

Decide to become a content genius.

LIFE IS POKER, NOT CHESS.

—Annie Duke, Thinking in Bets

SIR, THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCCESSFULLY NAVIGATING AN ASTEROID FIELD IS APPROXIMATELY THREE THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND TWENTY TO ONE!

—C3P0

NEVER TELL ME THE ODDS.

—Han Solo

“Life comes down to decisions,” my mom said to me one Sunday afternoon at least a decade ago. I appreciated the comment at the time because I had watched my mom and dad navigate many tough decisions together. For example, they took a chance on my dad starting a company the same year they started a family—when I was born. Even chancier, the company focused on the relatively new field of industrial automation—using electrical controls to perform tasks and streamline processes in factories. As you can imagine, my parents made many, many other decisions from there. The company ultimately succeeded. (Hopefully, they think the family did too.)

But I didn’t fully appreciate my mom’s comment about decisions until now. Since my mom’s comment, the wealth of research about decisions that comes from economics, psychology, neuroscience, persuasion, management, sociology, and even law has become much more accessible. And I find it valuable for gaining insight and taking action in life as well as in content.

In this chapter, we’ll take some inspiration from decision-making experts to help you develop quality insights and take effective action based on your content intelligence. This chapter also provides tips and examples to jump-start your approach to insight and action. After all, if you collect and analyze content data but don’t use it to make content decisions, you might as well not have any data.

Content Is Poker, Not Chess

In the excellent book Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts, poker genius and former psychology PhD candidate Annie Duke asserts that most decisions in life are much more like playing a hand of poker than like playing a game of chess. Why? The difference is the amount of data available to inform your decision. In chess, all the information is available. You see the move your opponent makes, and you know all the possible moves you can make in response. However, in poker you know your cards. If you’re really dedicated, you might know the odds of your pair of 3s winning. In the course of a hand, more information—such as the house’s cards, your opponents’ betting behavior, and even some of your opponents’ cards—becomes revealed to you. But you never have all the information available to you. You are constantly deciding whether and how to bet with only partial data. Annie notes in the book that

Poker is a game of incomplete information. It is a game of decision-making under conditions of uncertainty over time. (Not coincidentally, that is close to the definition of game theory.) Valuable information remains hidden. There is also an element of luck in any outcome. You could make the best possible decision at every point and still lose the hand, because you don’t know what new cards will be dealt and revealed. Once the game is finished and you try to learn from the results, separating the quality of your decisions from the influence of luck is difficult.

In chess, outcomes correlate more tightly with decision quality. In poker, it is much easier to get lucky and win or get unlucky and lose. If life were like chess, nearly every time you ran a red light you would get in an accident (or at least receive a ticket). But life is more like poker. You could make the smartest, most careful decision in firing a company president and still have it blow up in your face. You could run a red light and get through the intersection safely—or follow all the traffic rules and signals and end up in an accident.

I agree with Duke about life decisions, and I also find that tennis decisions and content decisions are like poker. (I think this explains why even though I love poker, I don’t play often. My brain is spent from all those life, content, and tennis decisions!) Even with the most robust content analysis, you will never have all the information about your customers, context, or even your business (if it’s large) available. If a content expert tells you they know the exact formula to achieve success with your content, run away. That “expert” is crazy, an amateur, or both. Your content decisions are like poker bets, not chess formulas.

Critical Content Decisions to Make

Content involves myriad decisions as you source/create, distribute, and manage it. But just as key poker decisions come down to whether to bet and, if you do, how much, I find that content decisions come down to three types. Understanding these types of decisions will help you identify when such a decision is appropriate for your content situation.

Stay the Course, But Optimize or Scale

You find that your approach to content is working pretty well. But you wonder whether it could work even better. These decisions relate to whether to make changes that optimize or scale content that is already pretty effective. For example, after succeeding with House of Cards, Netflix has tried to repeat that success. Netflix reviewed intelligence about which content has been effective with which audiences and developed new content ranging from Daredevil (one of my faves) to The Crown to the prequel to Wet Hot American Summer. Much of this original content has succeeded in terms of critical and popular acclaim. Only Netflix knows the detailed performance numbers for its original content across markets, but the public data about Netflix shows that they keep adding subscribers around the world at an explosive rate.1

In another example, the home security company Blink created a set of content promoted by email to onboard new customers. Blink conducted analysis, such as surveying customers about their top questions when they signed up, to make that content effective. But Blink didn’t stop there; the team constantly tests different combinations of text and images for onboarding and more. Email manager Daniel Hinds notes, “I test things bracket style—the winner of one test goes up against something new the next time, and we see who lasts.”2

When tackling this type of decision, consider questions such as

What can we learn from the elements of this content that are working well?

Which elements of the content could be even more effective? In what way?

How could we repeat this success with these customers?

How could we repeat this success in another area of the business?

Fix a Problem

Your content’s impact falls short of your expectations. Or your content has caused or exacerbated another problem. For instance, I’ve seen credit monitoring companies obtusely offer content laden with marketing-ese to consumers who come to them for help repairing their credit after suffering identity theft. That approach causes a host of problems, including lost sales, brand/company hatred that leads to brand adversaries (instead of advocates), and more regulatory oversight of their communications to consumers.

As another example, the American Cancer Society discovered a content problem when reviewing their data from Google Analytics and ContentWRX. The content problem centered on Road to Recovery, a unique program that connects cancer patients who need rides to cancer treatment with volunteers who can drive them. These two different audiences sought answers to their questions from one web page. The data indicated that the web page was leaving both audiences with more questions than answers—and lots of frustration. So the American Cancer Society successfully reorganized the content and offered pages with content tailored to each audience: the patients and the volunteers.3

When facing this type of decision, think about questions such as

Were our expectations for this content reasonable? Did the content really fall short, or were our expectations unrealistic?

What is the cause or source of the problem?

Is it the content itself? If so, what limits its effectiveness?

Is it the way the content is promoted, delivered, presented, or organized?

Is it a lack of alignment between the content and customer needs or tastes?

To fix the problem, do we need to change the content or do we need to remove it or stop producing it altogether?

What have we learned from this shortfall or problem?

Innovate or Address a New Opportunity

You want to take your content to the next level or make the most of a new opportunity. Let’s return to our Netflix example. Netflix has sought aggressive expansion beyond the United States into international markets, taking great care to translate and localize content for those markets. Netflix has painstakingly tried to make every bit of content, from subtitles to marketing descriptions, resonate with each international market. This hard work is paying off, resulting in 5.46 million of its 7.1 million new subscribers residing outside the US in the first quarter of 2018. With the success of its original content and its international expansion, Netflix has decided to bet $10 million on more content, including the marketing of that content, and only $1.3 billion on technology in 2018.4

As a different example, the marketing automation company MailChimp recognized an opportunity to gain more empathy for its customers, many of whom run online retail stores. Instead of imagining what being in their customers’ shoes is like, MailChimp decided to sell shoes. That’s right, MailChimp created its own online retail store and sold products for charity. This effort, aptly named Project What’s in Store, allowed the MailChimp team to learn firsthand about the decisions many of its customers face, the tools they use, and much more. Project lead Melissa Metcalf calls this approach “Becoming the Customer.” Not only did MailChimp gain empathy and raise money for charity, but the company also created a wealth of new content explaining lessons learned during the project and built a new email list topping 1 million subscribers. What’s in Store now also showcases lessons that MailChimp customers share about succeeding in ecommerce. (Curious about this content? You can check it out at mailchimp.com.)

When facing this type of decision, consider questions such as

How can we learn more about and meet the new interests, needs, and expectations expressed by our customers?

How can we learn more about and meet the needs of new customers we did not expect?

How do we need to adjust our content to meet the needs of customers in new markets?

How could we package or deliver our content differently to make our products or services better?

How could we monetize our content more effectively?

How can content intelligence help you tackle these types of decisions? I’d like to offer four useful ways.

Ways to Inform Content Decisions with Content Intelligence

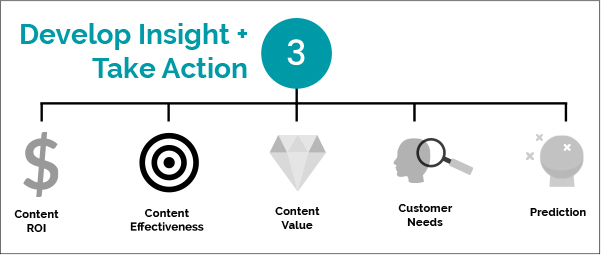

To get you started with using content intelligence, let’s review four handy approaches that are based on the Insight + Action element from our diagram of content intelligence (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1: The third element of content intelligence, Insight + Action

Assess Content Effectiveness

Understand what elements of your content are working well and what elements have an opportunity to be even more effective. This insight helps you identify elements you could optimize or elements that might be causing a problem. For instance, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) realized travelers were calling them with questions about vaccinations that their web content should have answered, the agency investigated and identified problems with their content’s findability, accuracy, and usefulness. The agency then worked on addressing those problems by changing the organization of the content, clarifying key points, removing less important content, and making the format easier to scan and use.

Calculate Content ROI or Value

Know whether the impact your content is making is worth the cost. CDC, for example, saved money on supporting travelers’ calls after making their web content more effective. As another example, in 2017 the Weather Channel launched new features and content in their mobile applications. The goal? To engage users in new ways. As mentioned earlier in this book, people turn to apps when the weather might be unfavorable or severe—not so much on sunny days. So content strategist Lindsay Howard worked with the team to think through sunny-day scenarios and develop ideas that would offer and promote relevant content. The results? Howard reports

Immediately, our “sunny day” efforts started seeing results. Since launching, we increased performance in double digits across all priority metrics, including visits per user, sponsorship traffic, total impressions, and retention. This is particularly significant in an app world, where every percentage point counts. International engagement, a key factor in global relevance and expansion, skyrocketed. A priority metric for content strategy, click-through rate, went up 23 percent in less than three months.5

The results were so valuable that the Weather Channel has committed to exploring other ways that the strategic planning of content can help their business.

Table 9.1 summarizes a few common ways to consider content ROI or value.

Think your company has to be big to get a return on content investment? Think again. In the book The Million-Dollar, One-Person Business, Elaine Pofeldt notes that one common type of such business is information provider, such as a business that charges a small fee for access to a newsletter or other content. Other types of small and successful businesses, such as niche online retailers who use platforms such as Shopify and email tools such as MailChimp, have found content invaluable for everything from sales to customer support. Content helps automate many of these functions, allowing the business to avoid adding overhead when increasing revenue.

Deepen Understanding of Customers

Learn more about who your customers are, what they need, and what they prefer from your content. For example, Kraft has used the insight they gained about their customers’ interests—gleaned from those customers’ interactions with their content—to make their advertising more effective. As another example, I have learned a tremendous amount about the topics and issues content professionals care about from the way they interact with Content Science Review. That insight has helped us develop new products, such as Content Science Academy, and more content for the magazine.

BUSINESS FUNCTION + CONTENT TYPE |

POTENTIAL CONTENT ROI OR VALUE |

|---|---|

Marketing |

|

Sales |

|

Customer Experience |

|

Service and Support |

|

Other Revenue/Value |

|

Predict the Impact of Changes

Explore different scenarios so that you make reasonable estimates instead of wild guesses. The more you understand the other elements, the better you can make such estimates. For instance, the Weather Channel gained enough insight from its “sunny day” launch to not only validate its success but also start predicting what impact that personalizing content even more—not just by weather but also by preferences such as content format (for example, video) and lifestyle—could have on its business.

The ability to predict the impact of changes can be especially useful for moving from a pilot to a larger-scale content effort. For example, I once worked with a niche online retailer of comfort shoes and lower-body health products to pilot offering educational content. We created a microsite on running and injury prevention that included quizzes and articles about running essentials and preventing and treating foot and lower-body health injuries. After reviewing the customer feedback and seeing some uptick in sales for the products featured, the retailer decided to develop a comprehensive set of educational content that ultimately led to a 36 percent increase in weekly sales. If the retailer had not evaluated the pilot and learned from it, the company would not have had enough intelligence to bet on expanding the educational content. And the retailer would have left millions of dollars on the table.

Content intelligence can help you close your information gap and improve the quality of your content decisions. Let’s talk more about the impact of quality content decisions.

Commit to Quality Content Decisions Over Time

One of my favorite movies, the critically acclaimed Casino Royale, centers on a poker game. The evil and mathematically inclined Le Chiffre arranges a high-rolling, multiday game to win back money he’d lost and now owes to many nefarious characters. In hopes of thwarting Le Chiffre, the British government backs James Bond to buy an entry stake and play the game under cover—a cover that Bond promptly and arrogantly blows. The tension rises over a long series of poker hands, interspersed with attempts to kill Bond on the breaks. (And we think we face decisions under pressure!)

The game has no shortage of entertaining ups and downs. Bond hangs with Le Chiffre at first, winning some hands and minimizing losses on others to amass a stack of chips. More and more players drop out. Bond uses the hands to learn more about Le Chiffre, commenting that the evil mastermind has a “tell.” Then, Le Chiffre starts betting even bigger on a particular hand. Bond suspects a bluff and calls it out, to the point that he goes all in on the last bet and shoves all his chips in the pot. Le Chiffre turns over a winning hand. Oops.

Furious, Bond’s team attributes his mistake to arrogance. But Bond does not give up. He focuses on what he learned. Le Chiffre faked a bluff, and Bond might have a tell of his own to keep under control. After fending off another attempt on his life, he secures backing from the American government to buy re-entry into the game. Ultimately, Bond wins it by making smarter decisions with the information he gained from the previous rounds and faking a bluff himself.

What does all this have to do with content? A lot, when it comes to making decisions.

Poker experts have criticized details of individual scenes in Casino Royale, and I have no doubt those experts are correct. However, what the movie gets right is the impact of trying to make quality decisions again and again (and again and again and again…) so that, over time, you win more than you lose. Casino Royale could have simply shown the final hand. But by showing several rounds and hands, the movie reminds us not to focus on winning one big hand. Focus on using the information you have at the start of the game and learning from the outcomes during the game so that when you do face a high-stakes hand, you’re more likely to win.

Winning the big hand is an outcome of consistently making quality decisions. Winning is never guaranteed because you cannot control the cards you are dealt and never have all the information available to you. But winning is much, much, much more likely when you focus on making the best decisions you can with the available intelligence—the information and insights that you have at the game’s start and, this is crucial, that are added while you’re playing the game.

The same goes for content. If you focus on making quality decisions with the content intelligence you have, over time you will be much more likely to get the outcomes you want. This focus has four implications that might surprise you:

Evaluate content decisions by decision quality, not outcome.

In many chapters throughout this book, I tout the importance of understanding the impact and performance of content, such as whether it reaches, engages, and influences the right customers. So you might be shocked for me to say that I don’t believe in judging content decisions purely by outcome—whether the content wins or loses. But judging decisions by quality is the only way to learn and acquire the intelligence that can make your future decisions even better.

Treat content intelligence as a system.

I’ve talked about content intelligence as a system because it is not a one-off project. It’s an ongoing effort. To inform your ongoing content decisions, you need a steady stream of content data and a regular process from which to glean insight.

Set expectations with stakeholders—the worthy ones will support you.

Manage the expectations of your boss and stakeholders by emphasizing the cumulative effect of quality content decisions. Never guarantee overnight results. With many content efforts, it will take at least a year to start seeing winning outcomes.

Track lessons learned in a center of content excellence.

You and your team might find it useful to capture lessons learned in a center of content excellence so you can easily consult them in future content decisions. I discuss a center of content excellence in Chapter 11.

Content Intelligence + Quality Decisions = Content Genius

A genius is someone who is exceptionally intelligent or creative in a particular capacity or field. As business relies more and more on content, we need more content geniuses in the world. You can become one by setting up a system of content intelligence, making quality decisions about content informed by that intelligence, and then learning from the outcomes as you reflect on the quality of the decision. If for some strange reason that sounds easy, it’s not. But the benefit is that, over time, content decisions will become easier and more successful for you.

To recap, the key secret to using content intelligence is committing to making quality content decisions over time. Content intelligence will not give you a formula that guarantees results. But when you make the best decisions you can with the content intelligence you have, you will become a content genius—and much more likely to win.

References

1 “Netflix Subscriber Growth Tops Expectations” www.wsj.com/articles/netflix-expands-growth-in-international-markets-1523911999

2 “How Blink Built Its Business with Email Automation” https://mailchimp.com/resources/marketing-automation-essentials/how-blink-built-its-business-with-email-automation/

3 “Content Intelligence: A Case Study with American Cancer Society,” Colleen Jones and Melinda Baker, Applied Marketing Analytics, Vol 2, 2 p152–161

4 “Netflix Subscriber Growth Tops Expectations” wsj.com/articles/netflix-expands-growth-in-international-markets-1523911999

5 “Forecasting What Mobile Users Want,” Content Science Review https://review.content-science.com/2017/08/forecasting-what-mobile-users-want-a-sunny-day-strategy-for-any-type-of-weather/