Every person should get a checkup with a primary care physician at least once a year. It may be while you are having one of these annual checkups that your doctor discovers that you are at risk for kidney disease or that you already have kidney disease. Although kidney disease usually has no symptoms, like fatigue or pain, a physical examination can determine whether you have high blood pressure, blood in the urine, or decreased kidney function. A thorough medical history helps your doctor know whether you have a predisposition to kidney disease or a family history of diseases that can lead to kidney disease, like diabetes, high blood pressure, or polycystic kidney disease (PKD).

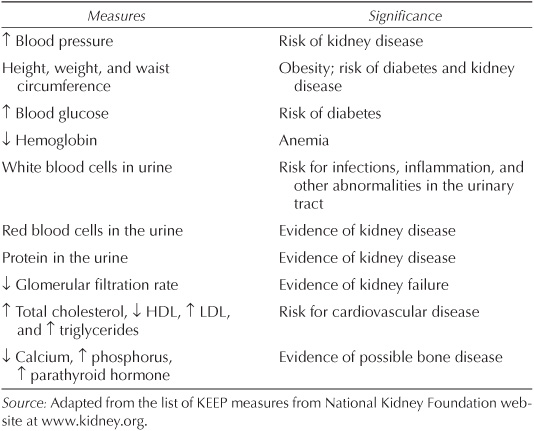

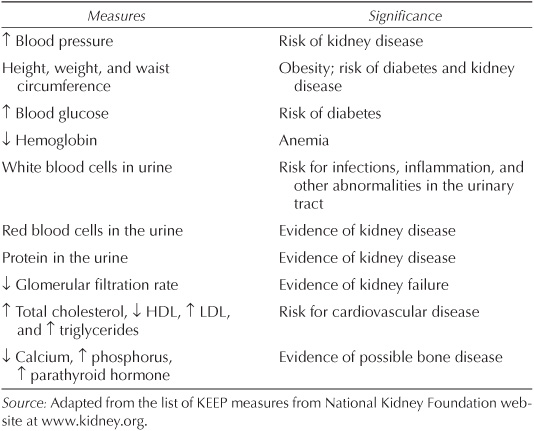

If you have one or more of these risk factors, your doctor may order additional screening tests. The National Kidney Foundation (NKF) has developed a screening program for risk of developing kidney disease called the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Your doctor may use certain measures to assess your risk and to find any evidence of kidney disease and whether it has progressed. Table 4.1 lists the measures of assessing risk. Screening typically consists of urinalysis (looking for protein or blood in the urine) and measuring creatinine or other factors in the blood. With a measure of blood creatinine, your doctor will calculate your glomerular filtration rate, a measure of the ability of your kidneys to filter toxins from your blood. The results of these tests may cause your doctor to suspect that you have kidney disease. A definite plus is that the results of the tests may provide an early warning, so your doctor can help you protect your kidneys from further damage and educate you about treatment options or changes in lifestyle. For example, your doctor may recommend that you lose weight, stop smoking, or control your blood pressure.

Table 4.1

Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Screening Measures

Being diagnosed with any disease can be terrifying. If you are diagnosed with kidney disease, gather as much information as you can about your condition and medical care, find ways to reduce the progression of kidney disease, and plan your future. Take an active role in your care. It will go a long way toward helping you feel more in control. This chapter covers some of the diagnostic tools and treatments involved with your medical care.

Doctors monitor kidney function in their patients by measuring substances in the blood and urine using several laboratory tests: blood urea nitrogen (BUN), or just urea, creatinine, creatinine clearance, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). To perform these tests, your health care provider will draw small amounts of blood and will ask you for a urine sample.

Urea and creatinine in the blood are measures of the main products of protein metabolism. How concentrated these substances are in the blood indicates how effectively your kidneys remove waste products. Normal concentrations of these substances are 15 to 25 mg/dl for BUN and 0.5 to 1.3 mg/dl for creatinine (mg/dl [milligrams per deciliter] refers to the amount of a substance in a bit more than 3 ounces of blood). Values higher than that range for either measurement mean that kidney function is declining.

A blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test measures the quantity of nitrogen in your blood that comes from the waste product urea. A BUN is performed to see how well your kidneys are functioning. If your kidneys can’t remove urea from the blood, your BUN level will rise.

Measuring creatinine clearance can determine how much creatinine your kidneys remove from your body as well as how well your kidneys are functioning. Creatinine clearance is a more precise measure of kidney function than relying on blood measurements alone. To perform a creatinine clearance test, your doctor will ask you to collect your urine over a twenty-four-hour period in a large container. A laboratory will then analyze your urine for creatinine. In addition to a urinalysis, a small amount of your blood will be analyzed for creatinine. Your calculated creatinine clearance is expressed as the volume of blood your kidneys completely clear of creatinine per minute. A normal creatinine clearance ranges from 90 to 130 ml/minute. As kidney function declines, creatinine clearance also drops.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR), the preferred method for assessing kidney function, is a test similar to creatinine clearance. Your doctor or a laboratory can estimate GFR from blood creatinine—taking into account age, gender, race, and body mass—using the GFR calculator provided by the National Kidney Foundation (http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator.cfm; or go to www.kidney.org and link to the calculator from there). Like creatinine clearance, GFR provides more accurate information about kidney function than blood creatinine alone does. Normal values are 80 to 120 ml/minute/1.73m2. From the value obtained, your doctor can determine the stage of your kidney disease and can easily monitor its progression without having to obtain a twenty-four-hour urine collection from you each time your blood creatinine is measured. In addition, she can use this information to plan your treatment.

Once kidney failure has been revealed through one of the tests described above, your doctor may refer you to a nephrologist. The National Kidney Foundation’s guidelines suggest that patients be referred to a nephrologist when their GFR is less than 30. Your doctor may also refer you to a nephrologist if he is not able to perform all the appropriate diagnostic, treatment, and management recommendations for kidney failure.

If you are happy with your doctor, then her recommended nephrologist will probably be someone you come to trust as well. But personal interactions are subjective, and different patients may view the same doctor differently, for all kinds of reasons. If you sense that you are not getting the nephrologist’s full attention, or if the nephrologist will not explain terms, concepts, or the medical care being recommended, or if you feel that your condition is not being properly managed, you may want to consider getting a second opinion from another nephrologist. It may be that you will want to switch doctors, or the second opinion may reinforce your confidence in your current nephrologist.

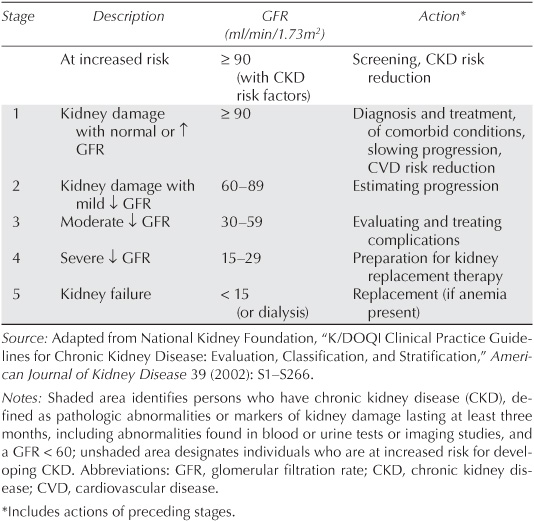

Table 4.2 displays the stages of kidney disease and outlines a general action plan that your doctor may use for each stage. Stage 1 is defined as the stage when GFR is 90 or higher but there are markers of kidney damage, like protein in the urine or kidney cysts in people who have PKD. Your nephrologist will check your heart’s health and will look for any other cardiovascular issues. At Stage 1 your nephrologist will concentrate on finding the cause of your kidney failure and on treating any underlying disease, like diabetes.

Stage 2 is classified by a GFR of 60 to 89. In addition to giving you a diagnosis of your stage, and treating you, your nephrologist will try to slow the decline of your kidney function, perhaps prescribing medications to control your blood pressure or to help treat other underlying diseases. During Stages 1 and 2, you must follow your doctor’s recommendations, even if you don’t feel sick. By doing so, you have the greatest chance of postponing the complete loss of kidney function, perhaps indefinitely. In addition, you may have no symptoms of kidney disease and you may feel well enough to live a normal life.

At Stage 3, with a GFR of 30 to 59, there are more evident complications of chronic kidney disease. For example, you may become anemic, show evidence of bone disease, or have a poor nutritional status. Although it may be years before your kidneys completely fail, if at all, your nephrologist will discuss with you the treatment options for kidney failure, including dialysis and transplantation.

Table 4.2

Sample Clinical Action Plan for Chronic Kidney Disease

If you reach Stage 4, with a GFR of 15 to 29, your nephrologist will prepare you for dialysis by explaining the process and will have you evaluated for a kidney transplant (see chapters 6 and 7). He will explain the drawbacks and benefits of these treatments and help you decide which one is best for you and your lifestyle. It’s a painful fact that a transplant may not be available for years, if you don’t have a donor. Your doctor can help you plan how to integrate these treatments into your life to make them as unobtrusive as possible.

Stage 5, when GFR is less than 15, means that you must have dialysis or transplantation to live.

Serum creatinine levels are a useful gauge of kidney function, but by themselves they are not a reliable indication of disease. Assessing the degree of kidney decline solely from these levels can be very misleading. When followed over time, they may appear to rise rapidly. However, calculating the GFRs for these values can provide a different picture. Changes in serum creatinine from 1 to 2 in the normal range represent much larger percentage changes in GFR than when they rise from 3 to 4. While on the surface it would seem that a change in the higher levels (3 and 4) would cause more concern than an increase from 1 to 2, we have to consider that a 100 percent change (from 1 to 2) is larger than a 33 percent change (from 3 to 4). It could be many years before you will need dialysis or transplantation. Thus, it is not that kidney function has declined faster, it just seems that way because you are only looking at creatinine, not GFR. In other words, your kidney function is not declining as fast as you may fear it is.

Your doctor will also determine whether you are anemic (see chapter 2). Red blood cells, hemoglobin, and hematocrit are all factors in diagnosing anemia. Hemoglobin is a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. Normal hemoglobin concentrations are between 14.0 g/dl and 18.0 g/dl. Hematocrit measures the percentage of blood volume occupied by red blood cells. Normal hematocrit values are 40 to 54 percent for men and 37 to 47 percent for women. Low hemoglobin or hematocrit values may mean you have anemia, a condition that is common in more advanced stages of kidney disease.

Once you have been referred to a nephrologist, he will become your primary care provider, even though your family physician will continue to be involved in your general care. Your nephrologist may be one of several doctors providing your health care, depending on the underlying disease causing your kidney failure. For example, if you have heart disease, a cardiologist may be monitoring your cardiac health; if you have diabetes, an endocrinologist may be managing your blood sugar; if you have lupus, a rheumatologist may be treating inflammation. Ideally, all of your doctors will work together as a team and will communicate closely with you and with one another.

The stage of kidney disease and the cause of kidney disease determine the recommended treatment. Many people do not see a nephrologist until their kidney disease is fairly advanced, because they do not know they have kidney disease until it reaches a later stage. But if you do see a nephrologist at an early stage, he can focus on the underlying cause and possibly intervene to reduce the progression of kidney failure as well as manage any signs and symptoms you may have.

A first visit to the nephrologist will include a thorough examination of your medical records, as well as assessments of your kidney function, urine, or any diagnosed kidney disease. If you have no diagnosed disease, your nephrologist will begin by identifying the primary cause of your declining kidney function. In addition, assuming that the nephrologist has ruled out acute or short-term kidney failure, she will want to know your stage of chronic kidney disease. With a diagnosis, the nephrologist can work to decrease the rate of loss of kidney function, to control your blood pressure, and, depending on the stage of kidney disease, to manage any complications. (Complications typically begin when your GFR is below 60.) Your nephrologist may also recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of your kidneys to measure their size or to locate cysts or stones. A kidney biopsy may be necessary to make a diagnosis and to help determine the best way to treat you.

Ask your nephrologist any questions you have about your disease. She should help you understand kidney failure and your long-term prognosis. Your nephrologist can also educate you about new treatments and the latest research that may ultimately lead to slowing the progression of kidney disease.

The information your nephrologist shares with you during your first visit depends on the underlying cause of your kidney failure. If you have diabetes and excrete protein in your urine, your nephrologist will advise you to control your blood sugar and blood pressure with diet and medications. If applicable, your nephrologist will recommend that you lose weight, stop smoking, and take measures to lower your cholesterol.

If you have PKD, you may be newly diagnosed and in the early stages of the disease, with only a few cysts in your kidneys. It could be many years before there is a need for dialysis or a transplant. Moreover, if you are newly diagnosed and in your fifties, you may never need dialysis or transplantation, especially if you have only a few cysts. The discussion of dialysis and transplantation varies greatly, depending on many factors.

By Stage 3, however, you may have lost half of your kidney function. At Stage 3, your nephrologist will probably advise you that you will need dialysis or a transplant in the future.

It is important that you understand the difference between stability of kidney function and level of kidney function. For example, your nephrologist may be satisfied if your creatinine remains at 3.0. However, he might not always remind you that you have lost more than half of your kidney function, and that being stable with poor kidney function is not normal. GFR almost never improves. Remember, your nephrologist wants to be reassuring at the same time that he wants you to take care of you. If it has been a while since you discussed your prognosis with your nephrologist, ask him to discuss your future with you.

As you read earlier in this chapter, you may encounter a number of consequences involving other organs and processes in your body as your kidney function declines. Although these problems can be worrisome, your nephrologist can help you manage them.

Kidney disease is a primary risk factor for heart disease—including heart attacks—just like smoking and high cholesterol are. As a result, your nephrologist will encourage you to manage your blood pressure and to live a healthy lifestyle. Living a healthy lifestyle is one aspect of your care over which you have total control. You can manage your diet more than almost any other aspect of your life. As your kidneys lose their ability to work properly, eating a heart-healthy diet is essential—along with managing your blood pressure and lowering your cholesterol. If you are obese, lose weight and begin an exercise program. If you smoke tobacco, stop smoking. Get help with weight loss and smoking cessation if you need to.

Depending on the stage of kidney disease, your nephrologist may recommend that you eat a low-salt diet, especially if you have high blood pressure. Failing kidneys cannot eliminate the excess salt intake, and so the soft tissues of the body begin to accumulate fluid. This accumulated fluid, called edema, can be uncomfortable, especially if it collects in the legs and ankles. Fluid accumulating in the lungs restricts the airway and can impair breathing. Prescription diuretics can help control your edema as long as you can still pass adequate amounts of urine. Occasionally excessive fluid in the lungs is a medical emergency, requiring hospitalization for removal. Tell your doctor immediately if you have any trouble breathing.

Your nephrologist will recommend a modest restriction of protein in your diet, because a lower-protein diet may slow the progression of kidney disease, especially if you have protein in your urine. You should eat a heart-healthy, high-fiber, low-fat, low-cholesterol diet. You can find more information about diet in chapter 5.

As we learned in chapter 2, kidneys do more than just filter waste products out of the blood. Kidneys also control blood pressure, regulate red blood cell production, maintain the proper acidity in the blood, control potassium and phosphate levels, and activate vitamin D to help build and maintain strong bones. When kidney function deteriorates, complications with the functions described above (and described in more detail below) may arise and may require medical treatment.

Low levels of red blood cells, or anemia, is one of the complications of chronic kidney disease. As kidney function declines, the amount of the hormone erythropoietin available to regulate red blood cell production decreases, leading to anemia. People with anemia feel tired, even with adequate sleep. Synthetic, injectable hormone treatments like Epogen, Procrit, or Aranesp (Darbepoetin) may help treat anemia. A health care provider can inject the medication for you or teach you how to do it yourself.

Prescription hormone treatment for anemia is most effective for people with hematocrit ranges from 30 to 33. If your hematocrit is much higher than these levels, hormone treatment may be unsafe, potentially causing heart problems and blood clots. Your nephrologist will carefully monitor your hematocrit to determine whether hormone treatment is right for you.

When kidneys can no longer regulate blood acidity, acid builds up, causing acidosis. If you have acidosis, your nephrologist will prescribe sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), which neutralizes the excess acid. You can use either regular baking soda that you find in the grocery store, sodium bicarbonate tablets, or sodium citrate liquid, which the body converts into bicarbonate.

Potassium and phosphate levels in the blood may rise with progressing kidney disease. High potassium and phosphate levels typically occur at Stages 4 and 5. Normal kidneys regulate the amount of potassium in the blood by excreting excess amounts. As kidney function declines, however, the kidneys may lose this ability and blood potassium can increase, sometimes to dangerous levels. If high enough, potassium can cause a heart attack. Although you can help lower potassium levels by managing your diet, in some cases, your doctor may prescribe sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) or a diuretic like furosemide (Lasix) to treat excess potassium. A dietitian can help you choose the right kinds of foods to avoid high potassium levels. Your nephrologist will recommend a consultation with a dietician if needed. Most dialysis centers have dieticians available.

Phosphorus in the form of phosphate is important in the production of energy from consumed food. However, the body does not use all of the phosphate ingested and must remove the excess amounts. Normally, the kidneys do that job. As kidney function deteriorates, the kidney cannot eliminate the excess phosphate, so it accumulates and lowers calcium in the blood. In people on or nearing the start of dialysis (see chapters 2 and 6), these deposits can, in the extreme, remove calcium from the bones and lead to osteoporosis. People with high phosphorus may also experience itching. People with high phosphorus levels must reduce phosphate intake (see chapter 6) and may need to take medications to bind ingested phosphate before it can be absorbed. Over-the-counter calcium carbonate tablets like Tums or prescribed drugs like calcium acetate (Phos-Lo) and sevelamer (Renagel) can help control high phosphorus levels.

As you lose kidney function, your body may not make enough kidney-activated vitamin D to maintain sufficient calcium levels to keep your bones strong. In addition, parathyroid hormone levels can rise, leaching calcium out of your bones. In reverse to what happens with excess phosphate in the blood, inadequate levels of calcium can make your bones brittle, causing them to break more easily or begin to hurt. Your nephrologist can treat vitamin D deficiency with several drugs, like paricalcitol (Zemplar) or calcitriol (Rocaltrol), synthetic forms that bypass the need for your kidneys to activate inactive forms of vitamin D (see chapter 2).

When our kidneys are working normally, we may be unaware of their great ability to cleanse our bodies of the toxins that accumulate after we digest our food. Urination is the only overt sign that our kidneys work at all. And when our kidneys slowly begin to fail, we can detect, at first, only subtle changes in how we feel. Here are a few of my experiences with kidney failure and a description of how my nephrologist helped me.

During the first three stages of kidney disease, I felt fine. The only health issue I faced during that period was high blood pressure and a kidney infection. My first symptom of kidney failure was fatigue. My fatigue occurred slowly, so initially I did not notice anything unusual. I just assumed I was working too hard or was not getting enough sleep. In time, fatigue became noticeable. By this point I had reached Stage 4 kidney failure.

During the two or three years before I began dialysis, I was so tired that I had difficulty getting up for work every morning, no matter how much sleep I got. Finally, after telling my nephrologist about my fatigue, tests showed that I had become very anemic. With fewer red blood cells carrying oxygen throughout my body, my muscles could no longer do what they needed to do for very long without my feeling debilitated.

My red blood cell count was very low, because I had lost so much of my own erythropoietin (EPO). As a result, my nephrologist prescribed an injectable form of the hormone to produce more red blood cells. Injecting it into my own body was similar to what people with diabetes do—injecting themselves with insulin to normalize their blood sugar. With practice, I found it easy to inject myself with EPO. Besides, I had to do it only once a week, rather than the twice-a-day injections of insulin. After several weeks of injections, I started feeling normal again. In the end, the fatigue I experienced confirmed what my increasing creatinine levels were already telling me: my kidneys were failing and dialysis or transplantation was inevitable.

A year later, my fatigue returned and I began to feel increasingly nauseated and was vomiting frequently. By then, I was approaching Stage 5. Nausea and vomiting were the worst symptoms that I had. To help, my doctor prescribed ondansetron (Zofran), which is used to treat nausea and vomiting in people with cancer who are receiving chemotherapy or radiation treatments. Even this heavy-duty drug could not completely treat my symptoms. I had to tough it out until I could start dialysis or receive a transplant.

In addition to nausea and vomiting, I needed more EPO to keep my anemia under control. Moreover, I required additional medication to control my blood pressure. All of this attention to treatment combined with symptoms sapped my energy, making it difficult for me to do anything. As my kidney failure accelerated, I had to decide, with the help of my nephrologist, when I would start dialysis, because I did not have a kidney donor.

The decision whether to start dialysis or to receive a kidney transplant, if a donor kidney is available, is both a medical and a personal decision. Medically, people usually cannot start dialysis until their GFR is below 15. Medicare will not pay for dialysis or transplantation until GFR is 15 or less, except when your doctor has documented other reasons, like fluid overload, high potassium, or acidosis that cannot be corrected with fluid restriction or medications.

For me, the decision to start dialysis depended mostly on how badly I felt and on knowing that dialysis would require a significant change in my lifestyle. I talked to some people who thought they had waited too long. Although it can take some time, many people feel better after starting dialysis. The decision to get a transplant is usually an easy one, unless you are not medically fit for one. When my kidneys failed, I really had no choice. I had to do something if I wanted to continue living. When I finally faced that decision, I started dialysis. As it turned out, it was not the end of the world. It saved my life.

I do not tell my story to scare you but to make the point that there are many ways to minimize the consequences of kidney disease. You should learn how to prevent or slow the progression of your declining kidney function. This knowledge can extend your healthy time before you have to make life-altering decisions about dialysis or transplantation. Chapter 5 explores the various ways you can change your behavior and various treatments to keep your kidneys working as long as possible.