Christophe Jaffrelot

It is the start of something new. Our countries have had our misunderstandings and disagreements in the past and there are sure to be more disagreements in the future, as there are between any friends or, frankly, any family members.

HILLARY CLINTON, 2010

We acknowledge to ourselves privately that Pakistan is a client state of the U.S. But on the other hand, the U.S. is acting against Muslim interests globally. A sort of self-loathing came out.

PERVEZ HOODBOY, 2010

The U.S.–Pakistan relations that have developed with ups and downs over the last six and an half decades can probably be best characterized as a security- (or military-) related form of clientelism.1 French political scientist Jean-François Médard defines clientelism as “a relationship of dependence … based on a reciprocal exchange of favours between two people, the patron and the client, whose control of resources are unequal.”2 A clientelistic relationship does not imply any ideological sympathy but is purely instrumental.3 Despite the mutual dependence it establishes, its asymmetric nature gives the patron a clear advantage—up to a point. The patron is in a position to get things done by the client, the client paying allegiance to the patron in exchange for benefits, including protection.4

During the Cold War and the anti-Soviet war in Afghanistan, Pakistan played the role of client state of the United States: in exchange for considerable civil and military aid, the country participated in the containment of communists in Asia. But already at the time the terms of the countries’ cooperation were clearly circumscribed from two standpoints: first, Pakistan—as a sovereign state—wanted to maintain substantial room for maneuver; and second, each time the United States demonstrated too close an alliance with India, the Land of the Pure behaved less as Uncle Sam’s obedient intermediary than as a pivotal state using its geopolitical position to further its national interests by partnering with other powers. The second war in Afghanistan, which began after the September 11, 2001, attacks, although at first it looked like it would repeat the scenario played out in the combat against the Soviets, in fact marked a turning point. Barack Obama’s policy on Pakistan, the focus of this chapter, far from bringing the two countries closer together again after they had drifted apart toward the end of the Bush years, has not been able to fully defuse bilateral tensions.

A CYCLICAL CLIENTELISTIC RELATIONSHIP

The U.S.–Pakistan relations that crystallized in the 1950s were not based on deep political, economic, or societal affinities and ties: Pakistan has been governed by the army more often than not, something Washington at times found embarrassing; there were no intense economic relations between both countries, nor were there any person-to-person relations, partly because the Pakistani diaspora in the United States was very small and not very well integrated.

Geopolitical considerations and strategic mutual interests were the main reasons the United States and Pakistan became “friends.” As early as 1947, Karachi (the then capital of the country) asked the United States for support in order to cope with the so-called Indian threat. In December, Pakistan asked the United States for a $2 billion five-year loan for economic development and security purposes.5 President Truman, who was as yet unsure whether the United States should get closer to India or Pakistan, committed to a much smaller amount—$10 million—and invited Nehru to Washington. Liaquat Ali Khan immediately announced that he would pay a visit to Moscow shortly thereafter. Truman invited him to the United States as well. Nehru’s visit to the United States in October 1949 was not a success from Washington’s point of view, given the Indian prime minister’s rejection of the polarization of world politics along two blocs. Liaquat Ali Khan—who did not go to Moscow—visited Washington in May 1950. He solicited the United States on two related fronts: arms procurements and $510 million in aid for development and military purposes. Truman remained noncommittal.

Things changed soon afterward in the context of the deepening of the Cold War and the hot episode of the Korean War—which started one month after Khan’s visit—and definitely after Eisenhower took over power in Washington in 1953. The United States then decided to use Pakistan to counter Soviet expansion in the region. Karachi was prepared to play this new version of the “Great Game” so long as this strategy was useful against its archenemy, India.6

On the one hand, Pakistan joined both the Central Treaty Organization and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization and in 1957 gave the Americans access to an air base from which U2s could spy on the USSR.7 On the other hand, the United States was prepared to give Pakistan very substantial aid and to sell the country millions of dollars in arms so that it would be better equipped than India. Pakistan became a client state as much from a developmental point of view as from a security perspective. Only 25 percent of the nearly $2 billion it received in American assistance between 1953 and 1961 was in military aid.8 As Akbar Zaidi points out: “By 1964, overall aid and assistance to Pakistan was around 5% of its GDP and was arguably critical in spurring Pakistani industrialization and development, with GDP growth rates rising to as much as 7 percent per annum.”9 At that time, few countries were supported by the United States to such an extent.10

However, the security dimension of this relationship largely explains why military coups have never presented a problem for the world’s oldest democracy. In fact, to have generals at the helm made things easier for the United States in the 1950s, as evident from the personal equation between Eisenhower—an ex-army man himself—and Ayub Khan, who described Pakistan as the United States’ “most allied ally.”11

INTEREST-BASED AND (THEREFORE) UNSTABLE U.S.–PAK RELATIONS

A BONE OF CONTENTION, INDIA; AND A NEWCOMER ON STAGE, CHINA

U.S.–Pakistan relations were clearly built on a quid pro quo that both countries decided to cultivate. Whereas the United States relied on Pakistan against the USSR—and, increasingly, China—not worrying about the lack of amity with India,12 Pakistan looked to America for help against India and was not averse to aligning against the USSR as well as against China until the Sino-Soviet split.

But the fact that both countries did not have exactly the same enemies made their relations inevitably complicated. A bone of contention that was bound to recur was the nature of relations between the United States and India—that country overdetermining Pakistan’s worldview. In the early 1960s, President John Kennedy came to office “determined to pursue closer relations between the U.S. and India, a country he viewed as pivotal in the struggle between East and West, without undermining the alliance between the U.S. and Pakistan.”13 He approved a two-year commitment of up to $1 billion in support of India’s economic development in 1961,14 which complicated U.S.–Pakistan relations—all the more so as the U.S.-led consortium that was supposed to mobilize resources in favor of this country could not raise much money. Although in 1961, the United States delivered twelve F-104 jet fighters to Pakistan in the framework of an agreement signed the year before, one year after, Washington sold arms to India during the 1962 war initiated by China.

That was an important episode for the U.S.–Pakistan relations. When Nehru turned to Kennedy for help after the Chinese attack, the prompt, positive response he received was all the more disturbing for Pakistan as Islamabad was not informed in advance of the latter’s decision to provide arms to the former (something that allegedly contravened a secret bilateral deal signed in 1959). Considering that America pursued a policy “based on opportunism and … devoid of morality,”15 Ayub Khan (and his new foreign minister, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto) turned more decisively to China—a clear indication of the need for a patron that Pakistan always felt was necessary to cope with India and of both the importance of the Indian factor and the interaction between U.S.–Pakistan relations on the one hand and Pakistan–China relations on the other. In 1964, Ayub Khan invited Chou En Lai to Pakistan, a visit that was to be followed by many others. Playing the game of a pivotal state, Ayub Khan declared in 1965 that he now knew “how to live peacefully among the lions by setting one lion against another.”16

And 1965 also marked the next step in the souring of relations between Washington and Islamabad, as the United States did not intervene on Pakistan’s side in the war with India and—even worse—cut off aid to both sides (which hurt Pakistan more than India). Afterward, the United States kept aid shut off until Nixon made a “one-time exception” to supply arms in 1969.

However, the U.S.–Pakistan partnership experienced a tactical renaissance because of its very clientelistic quality. In the early 1970s, Islamabad became a key intermediary between Washington and Beijing when Nixon and Kissinger wanted to make an overture to the Chinese. Nixon, in exchange, resisted the U.S. Congress condemnation of the savage repression of the Bangladeshi movement—and the correlative demand for the suspension of American aid.

But the Indian factor resurfaced soon after. First, the United States did not help Pakistan during its war against India, which resulted in the traumatic birth of Bangladesh, except by sending the aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal. Second, Jimmy Carter—a Democratic president like Kennedy—not only was particularly concerned by Pakistan’s nuclear program (as evident from the sanctions he imposed on the country in accordance with the Glenn and Symington amendments), but he promoted a new—short-lived—U.S.–India rapprochement that was perceived by many Pakistani leaders as directed against them. Indeed, in January 1978, Carter was the first American president not to visit Pakistan before or after a visit to India, a decision naturally related to his boycotting of the new master of Pakistan, General Zia, who had deposed Bhutto the year before. In 1979, Carter suspended American aid as a response to what the United States considered Pakistan’s covert construction of a uranium enrichment facility.

FROM AFGHANISTAN TO AFGHANISTAN

President Carter discarded most of his reservations vis-à-vis Pakistan the moment the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. Pakistan was immediately selected as the frontline state that the United States would use in the old military-clientelistic perspective. Carter suggested that the 1959 security agreement that was the brainchild of Eisenhower and Ayub Khan should be reactivated, and he cleared the sale of military aircraft to Pakistan.

While Carter’s initiative remained limited, his successor, Ronald Reagan, considerably amplified this change. Not only did he not object to the development of Pakistan’s nuclear program as much he could have done despite the Pressler amendment,17 but the United States gave Pakistan about $4 billion in 1981–1986 (half for military purposes and half for civilian purposes) and sold sophisticated weapons to its military. In 1987, Reagan and Zia negotiated another new six-year aid budget of $4 billion, in which 43 percent of the expenditures were to be security related, mostly earmarked for the Pakistani army. Reagan’s successor, George Bush Sr., routinized this security-centered clientelistic relationship.

The war against the Soviets, however, gave a new flavor to the old clientelistic equation. When the United States subcontracted the war to Pakistan, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) was given a great deal of autonomy to select which groups of mujahideen were to fight in Afghanistan. Shaping the jihad, the ISI channeled the aid flows to the groups it favored, and in fact the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was asked to help these groups in such a way that the patron lost some of its authority.

A security-oriented clientelistic relationship is neither value based nor rooted in economic ties or in societal affinities and is therefore less stable. U.S. attention and “interest” in Pakistan rose recurrently in times of crisis when Pakistan could help the United States combat the USSR. But it was bound to sink below the active-engagement level each time diplomacy-by-the-rule-book took over, relegating Pakistan to an unimportant position again, as attested by the less-than-first-rank diplomats posted there as well as the studied inattention it received after the Soviets were defeated in Afghanistan.

In the late 1980s, after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the United States lost interest in Pakistan—or more exactly, the interest that Pakistan represented for the United States diminished and considerations based on values and other interests filled this vacuum. The nuclear proliferation issue suddenly gained new prominence, resulting in some American sanctions:18 $300 million in aid was cut and the United States announced that the F-16s that Pakistan had already paid for in 1989 would not be delivered—but Pakistan was allowed to buy other material at market price (Islamabad disbursed $120 million for military equipment in 1991–1992).19

Bill Clinton maintained this line of conduct in the mid-1990s, softening the sanctions in two different ways. First, civil aid reached $2 billion in 1995. Second, in 1996, $368 million worth of military equipment, the delivery of which had been frozen by virtue of the Pressler amendment, was shipped to Pakistan, and $120 million was refunded for prepaid material that the United States refused to sell. If U.S.–Pakistan relations remained on a (rather low) plateau until the late 1990s, the Pakistani 1998 nuclear tests (like the Indian ones) resulted in new sanctions. A few months later, the Al Qaeda attacks on the U.S. embassies of Dar Es Salaam and Nairobi led to more acrimony, all the more so as the missiles that the American fleet in the Indian Ocean fired on Al Qaeda camps in Afghanistan killed militants among whom were Pakistanis. The following year, the Clinton administration attributed the Kargil war in Jammu and Kashmir to Pakistani military adventurism. On July 4, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif went to the White House, where he was requested to order “his” generals to withdraw behind the Line of Control. Only months afterward, as a sequel to this fiasco, Chief of Army Staff General Musharraf orchestrated a military coup, which persuaded the United States to impose additional sanctions on Pakistan. The U.S. attitude was all the more resented in Islamabad as Washington at the same time was forming closer ties with New Delhi. In March 2000, this divergence was caricatured in the contrast between the Clintons’ festive five-day visit to India and Bill Clinton’s five-hour stopover in Islamabad—during which he spent most of his time lecturing the Pakistanis on television and asking Musharraf to spare the life of Nawaz Sharif.20

A year and a half later, in the wake of 9/11, Washington turned to Islamabad—where Musharraf was ready to play the military-clientelistic game. For George Bush, Pakistan was once again the frontline country par excellence. It could provide military logistic bases to fight this new Afghan war and share intelligence. Musharraf, who had to convince the army cadres to join hands with the United States against the Taliban whom they had supported so far, argued in favor of including Pakistan in “the coalition of the willing” that Washington was putting together for the “global war on terror.” First, Bush had told him that if Pakistan was not “with” the United States, it would be considered as being “against” the United States. Second, Musharraf believed that the war would not annihilate the Taliban’s influence and that Pakistan would be able to maintain some relationship with them. Third, India was asking to be a U.S. partner as well—and Pakistan could only lag behind its arch-enemy at its own risk. And last but not least, Pakistan was not in a position to refuse, even if Bush had been less pushy, given the country’s diplomatic isolation and its economic situation.

Focus is warranted on this last aspect that is so important for the clientelistic dimension of U.S.–Pakistan relations. Pakistan’s lost decade—the 1990s—ensnared the country in a spiral of debt. In only five years, between 1995–1996 and 1999–2000, total debt had risen from Rs 1,877 billion to Rs 3,096 billion, with service of the debt reaching 45 percent of budget spending and 63 percent of receipts in 2000. At the same time, the army still needed a huge amount of money. Military expenditure represented 21 percent of the budget spending in 2001–2002—despite an artificial reduction due to the transfer of military pensions under the heading of “general administration.”

By joining hands with the U.S.-led coalition against terror, Pakistan killed two birds with one stone. First, it was reintegrated with the concert of nations. Musharraf made a tour that took him to Tehran, Istanbul, Paris, London, and New York, where he had his hour of glory while addressing the United Nations on November 12, by George Bush’s side, as the two men issued a joint statement emphasizing the friendship uniting both countries “for fifty years.”21 Second, Pakistan received preferential treatment in terms of aid, the United States paving the way for other countries. Washington lifted all sanctions connected with the nuclear issue (from the 1978 Symington amendment to the 1985 Pressler amendment and the Glenn amendment of 1998) and those that had been decided in the wake of Musharraf’s military coup22—which allowed the country to obtain loans from the United States and send officers there for military training, neither of which had been possible since 1990.

THE BUSH–MUSHARRAF AXIS AND ITS LIMITS

Musharraf was in a position to repeat Zia’s achievements during the previous Afghan war. He could persuade the United States to legitimize his military rule, extract funds from them, and acquire American weapons.

THE “MOST ALLIED ALLY” PATTERN REVISITED?

In the 1980s, Zia had asked one of his generals to tell Secretary of State Haig that “we would not like to hear from you the type of government we should have.”23 Haig had responded: “General, your internal situation is your problem.”24 History was repeating itself a dozen years later. Although in late 2001 Musharraf committed to holding elections the following year, he pointed out, in New York, on November 13, that he would remain in office regardless of the results. The American media had prepared the ground for this kind of declaration. Newsweek, for instance, commented on Musharraf’s rule in explicit terms: “We should certainly be happy that Pakistan is run by a military dictator friendly towards us, rather than that the country try to be a democracy that could have been hostile.”25 Hence the bitterness of progressive Pakistani editorialists. Zaffar Abbas lamented in the Herald, “The problems of democracy and human rights have very clearly been relegated to a lower level while the U.S.A. returns to the cold war philosophy according to which ‘our dictator is a good dictator.’”26

The United States developed an increasingly benevolent attitude vis-à-vis Musharraf in the early 2000s for two main reasons. First, he facilitated their war in Afghanistan. Pakistan allowed the United States to use its airspace and fly sorties from the south; it gave U.S. troops access to some of its military bases (for nonoffensive operations only); Pakistani soldiers ensured the protection of these troops and of some American ships in the Indian Ocean; in terms of logistics, Pakistan not only provided vital components such as fuel for the fighters, but it also gave access to its ports (including Karachi) and roads (including the Indus Highway, which became a jugular vein) for the delivery of most of the supplies North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces required in Afghanistan; last but not least, “Islamabad provided Washington with access to Pakistani intelligence assets in Afghanistan and Pakistan.”27

Second, Musharraf to some extent delivered in the fight against Al Qaeda. The capture of Abu Zubeida in Faisalabad on April 6, 2002, of Sheikh Ahmed Saleem in Karachi in July, of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, one of bin Laden’s lieutenants who had been the architect of 9/11, in Rawalpindi on March 1, 2003, and of Tanzanian Al Qaeda leader Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani—one of the chief accused in the blast of the American embassies in Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam in 1998—on July 27, 2004, in Gujrat was very much appreciated in Washington.28 By 2004, about 700 Al Qaeda suspects had been killed or captured in Pakistan according to a report prepared for Congress.29

In addition to his fight against Al Qaeda, Musharraf seemed prepared to fight against all Islamist organizations, as suggested in his January 12, 2002, speech propounding what became known as “enlightened moderation” and the subsequent ban of several Islamist groups. In exchange, the United States was rather complacent over the nonproliferation issue and resumed its aid on an unprecedented scale. Washington denounced Pakistan transfer of nuclear technology to North Korea in October 2002, but nothing happened until late 2003, when the matter became public. Even then, the United States seemed to take it rather lightly. In December 2003 and January 2004, nuclear scientists from Kahuta Laboratory suspected of having sold nuclear technology to foreign countries were detained and interrogated by the police. On January 31, A. Q. Khan himself, founder of the Kahuta Laboratory and father of the Pakistani bomb, was accused of similar acts regarding Iran, North Korea, Iraq, and Libya. While under house arrest, he admitted on television, in February 2004, that he had organized such exchanges in an individual capacity, and his supporters immediately mobilized in great numbers.30 Musharraf pardoned A. Q. Khan straightaway, feting him as a national hero.31 Interestingly, the U.S. administration offered no protest whatsoever: Washington obviously needed Pakistan so badly that on March 18, 2004, it declared Pakistan one of its non-NATO allies.

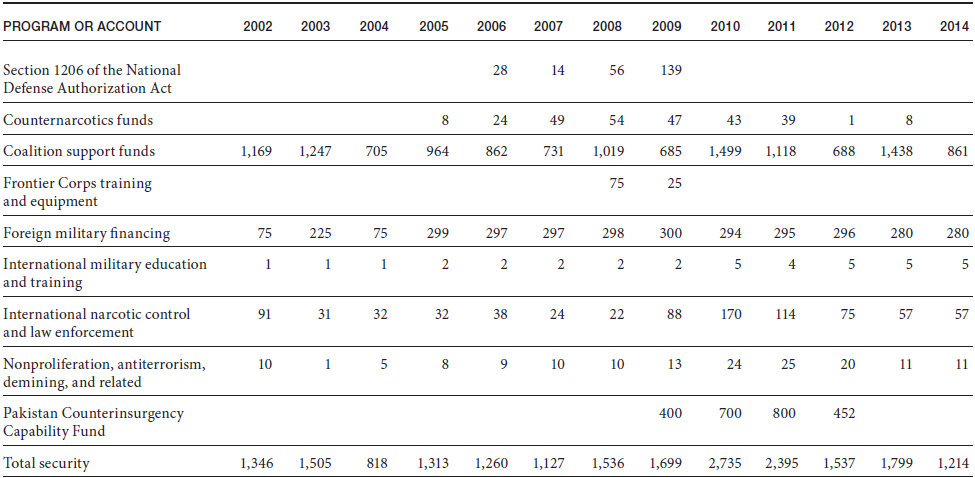

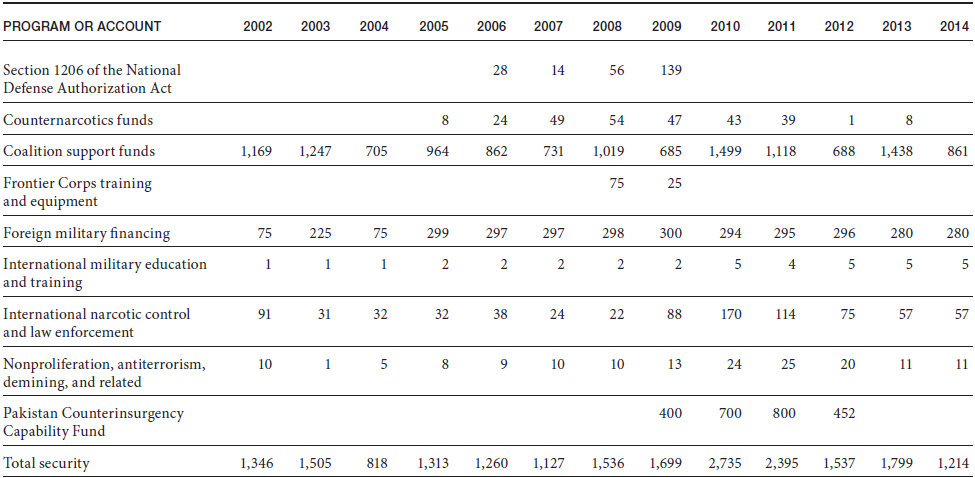

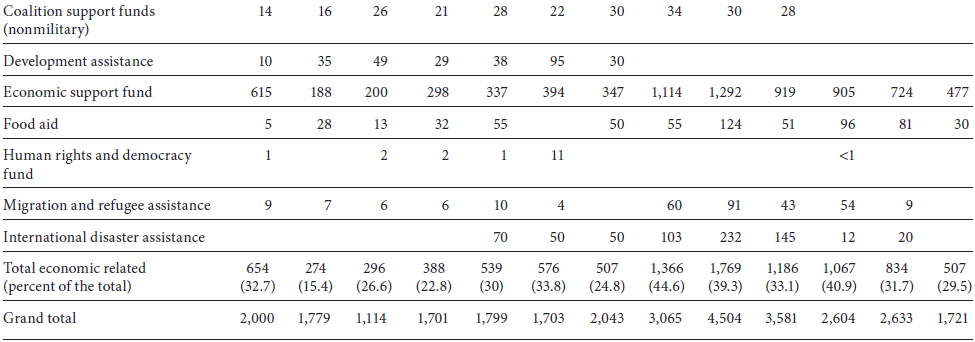

More important, in August 2004, Pakistan received the first of three yearly installments of the $3 billion the United States had promised Musharraf during his June 2003 visit to America.32 Out of these $600 million, $300 million was earmarked for military procurement and the other $300 million for development and civil expenditure. In addition, in 2007 the U.S. government granted an additional $750 million as the first disbursement of a five-year plan for the development of the Federally Administered Tribal Agencies (FATA). The United States gave $12 billion in aid and military reimbursements to Pakistan between 2002 and 2008—out of which $8.8 billion was security related (table 8.1). The Pakistan army received about $1 billion a year for seven years—in other words, roughly a quarter of the country’s yearly defense budget in the mid-2000s.33 The ISI depended even more on American financial support. The CIA’s contribution to the agency’s budget allegedly amounted to one-third of the total.34

YET ANOTHER DISENCHANTMENT: WHO IS THE BOSS AFTER ALL?

By the end of Bush’s second term, the U.S. administration had realized that Musharraf and the Pakistani army had not been fully reliable allies and Congress became even more critical of the president’s strategy.

First, not only was it clear in 2008 that no Al Qaeda leader had been either caught or killed since 2004, but in September of that year, the United States was alerted that “Pakistan’s top internal security official conceded that Al Qaeda operatives moved freely in this country.”35 Second, the United States noted that the FATA had become a major safe haven for militants who were striking the NATO troops in Afghanistan—one-third of the attacks they faced were coming from that side36—and the Afghan Taliban had apparently found another sanctuary in Quetta where their Shura (Council) could meet safely.37 Third, “by the close of 2007, U.S. intelligence analysts had amassed considerable evidence that Islamabad’s truces with religious militants in the FATA had given Taliban, Al Qaeda, and other Islamist extremists space in which to rebuild their networks.”38

The “FATA issue,” therefore, was bound to dominate U.S.–Pakistan relations. As mentioned above, the Taliban and Al Qaeda operatives had found there a safe haven during the 2001 Afghan war. Since then, the U.S. administration had put pressure on the Pakistani army for it to deploy troops in this area. In 2002, the army launched Operation Meezan, “thus entering FATA for the first time since the country’s independence in 1947.”39 About 24,000 military and paramilitary troops were deployed. A second operation, code-named Kalusha, took place in March 2004. Both failed. Not only were the tribes hostile to these military incursions and the well-trained militants were heavily armed, but the Pakistani army, lacking basic expertise in counterinsurgency techniques, further alienated the tribal leaders by causing collateral casualties while resorting to indiscriminate bombing. They decided to negotiate peace deals with the militants.

TABLE 8.1 OVERT U.S. AID AND MILITARY REIMBURSEMENTS TO PAKISTAN (2002–2014) (ROUNDED TO THE NEAREST MILLION DOLLARS)

SOURCES: FOR 2002–2006, SUSAN B. EPSTEIN AND K. ALAN KRONSTADT, PAKISTAN: U.S. FOREIGN ASSISTANCE, CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE, CRS REPORT FOR CONGRESS, OCTOBER 4, 2012, HTTPS://WWW.FAS.ORG/SGP/CRS/ROW/R41856.PDF. FOR 2006–2009, U.S. DEPARTMENTS OF STATE, DEFENSE, AND AGRICULTURE; U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT; HTTP://FPC.STATE.GOV/DOCUMENTS/ORGANIZATION/196189.PDF. FOR 2010–2014, “DIRECT OVERT U.S. AID APPROPRIATIONS FOR AND MILITARY REIMBURSEMENTS TO PAKISTAN, FY2002–FY2015: PREPARED BY THE CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SER VICE FOR DISTRIBUTION TO MULTIPLE CONGRESSIONAL OFFICES, DECEMBER 22, 2014,” WWW.FAS.ORG/SGP/CRS/ROW/PAKAID.PDF.

The first one was signed with Wazir tribesman Nek Muhammad, the most popular—and even charismatic—fighter, in Shakai, South Waziristan. This agreement, in exchange for the militants’ commitment to abstain from fighting the Pakistani government and NATO forces in Afghanistan, made provisions for the release of 163 prisoners, financial compensations to the victims of military operations, and the safety of the foreign mujahideen who were allowed to stay in the FATA, provided they were registered. This last clause was a bone of contention that resulted in the relaunching of military operations in June 2004. Negotiations took place again, and another agreement was signed in February 2005 between the Pakistani authorities and Baitullah Mehsud (who had somewhat taken over from Nek Muhammad, killed in 2004, and was to become the first chief of the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan). It again stipulated that the militants should neither attack Pakistani civil servants or property nor support foreign fighters. In exchange, the army pledged not to take action against Mehsud and his companions because of their previous activities. Mehsud scrapped the deal in August 2007 “in reaction to increased patrols by Pakistan’s army.”40 A similar deal had been made in North Waziristan in September 2006. It also collapsed in 2007.41

Last but not least, the United States had to admit, again in 2007, that it had relied far too exclusively on Musharraf and his army. In fact, the personal equation that Bush and the Pakistani president had developed had become a liability. With the rise of anti-Americanism that followed the U.S.-led 2001 war (which the Pashtuns were not the only Pakistanis to resent), the United States had given Musharraf a bad name (literally speaking, since he was often called “Busharraf”).42 Musharraf in turn had damaged his image in the United States by his growing authoritarianism, manifest in the hijacking of elections, repression of the judiciary, and, eventually, declaration of the state of emergency in November 2007. The State Department’s Country Report on Human Rights Practices released in March 2008 emphasized that Pakistan’s record in this domain had worsened because of the increasing number of extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and cases of torture.43 As Hussain Haqqani, who was to become Pakistan’s ambassador in Washington, stated before the House Armed Services Committee on October 10, 2007,

The United States made a critical mistake in putting faith in one man—General Pervez Musharraf—and one institution—the Pakistani army—as instruments of the U.S. policy to eliminate terrorism and bring stability to the Southwest and South Asia. A robust U.S. policy of engagement with Pakistan that helps in building civilian institutions, including law enforcement capability, and eventually results in reverting Pakistan’s military to its security functions would be a more effective way to strengthening Pakistan and protecting United States policy interests there.44

Bush policy was well in tune with the traditional security-centered clientelistic relationship that the United States and Pakistan had cultivated with occasional hiatuses since the 1950s. But it was time for review, since this strategy was clearly not delivering. Alternative voices could now not only speak up but also be heard. Experts such as Bruce Riedel and Teresita Schaffer as well as members of Congress regretted more vehemently than ever before that the Bush administration did not make any significant effort to promote democracy in Pakistan or to alienate President Musharraf.45 This approach could no longer be ignored after elections were held in Pakistan in February 2008, putting a civilian government back at the helm of Pakistan.

It is in this context that in July 2008 Senators Joe Biden and Dick Lugar introduced the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Bill (S. 3263) in order to break with what they called the “transactional”—I would say clientelistic—perspective and to promote “a sustained, long term, multifaceted relationship with Pakistan.”46 Such an agenda implied a tripling of nonmilitary American assistance to $1.5 billion per year over the 2009–2013 period. Simultaneously, military aid and arms transfers would be conditional on two developments: first, the army should show that it made “concerted efforts” in its fight against Islamist groups; and, second, it should not interfere with political and judicial processes. While the overtone of the bill was critical of the army, it also reflected a sense of introspection. Biden and Lugar wanted to “reverse a pervasive Pakistani sentiment that the United States is not a reliable ally.”47 This feeling, which originated in the way the United States had left the region after the withdrawal of the Soviets from Afghanistan, was shared not only by Musharraf—who said publicly in January 2008 that Pakistanis felt that they had been “used and ditched”48—but also by his successor, President Zardari, who was elected democratically in September 2008. In a January 2009 op-ed in the Washington Post, Zardari wrote, “Frankly, the abandonment of Afghanistan and Pakistan after the defeat of the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s set the stage for the era of terrorism that we are enduring”49—a very personal reading of history.

Barack Obama took office at almost the same time as Zardari, and he was to pursue the nascent attempt at breaking with the old pattern of security-centered clientelism while capitalizing on the new civilian rule in Pakistan.

WHAT HAS CHANGED WITH OBAMA?

During the 2008 election campaign, Obama emphasized the need to look at the Afghan issue in a larger perspective. He was convinced that the problem of Kashmir and the FATA should be dealt with simultaneously and that the relaxation of Indo-Pakistani tensions would prepare the ground for Islamabad to transfer more troops to positions along the Afghan border. In December 2008, after being elected, he said, “we can’t continue to look at Afghanistan in isolation. We have to see it as a part of a regional problem that includes Pakistan, includes India, includes Kashmir, includes Iran.”50 Such statements caused so much protest in India that he immediately gave up the idea of addressing the Kashmir issue. But the “AfPak” concept remained after Obama took office.

PAKISTAN AS A LONG-TERM PRIORITY: THE AFPAK NOTION AND THE KERRY-LUGAR-BERMAN ACT

Introducing the “AfPak” concept, Obama bracketed together Afghanistan and Pakistan because, for him, Afghanistan could not be “solved” without “solving Pakistan.” That move was made explicit with the appointment of Richard Holbrooke as the president’s special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan. The idea was not only to use Pakistan vis-à-vis Afghanistan but to highlight the fact that the Islamist problem lay in Pakistan—something the Bush administration had not been unaware of but did not pay much attention to either. Obama considered that Pakistan was as important as Afghanistan, if not more so, for American strategy and interests. When he said that the “cancer”51 that destabilized the whole region was in Pakistan, one wondered whether he was not even shifting from AfPak to PakAf.

One year after his 2008 election, Obama continued to think in these terms. In his December 2009 West Point address, when he announced “the surge,” the sending of 30,000 additional American troops to Afghanistan, he made it clear that “an effective partnership with Pakistan” was one of the “core elements” of the U.S. strategy. But he did not want to view this partnership in the narrow, security-centered, and clientelistic perspective of the past:

In the past we too often defined our relationship with Pakistan narrowly. Those days are over. Moving forward, we are committed to a partnership with Pakistan that is built on a foundation of mutual interest, mutual respect, and mutual trust. We will strengthen Pakistan’s capacity to target those groups that threaten our countries, and have made it clear that we cannot tolerate a safe haven for terrorists whose location is known and whose intentions are clear. America is also providing substantial resources to support Pakistan’s democracy and development. We are the largest international supporter for those Pakistanis displaced by the fighting. And going forward, the Pakistan people must know America will remain a strong supporter of Pakistan’s security and prosperity long after the guns have fallen silent, so that the great potential of its people is unleashed.52

Stressing America’s long-term, non-security-related commitment to Pakistan, Obama was evidently eager to dispel the pervasive impression among Pakistanis that the United States was unreliable and would let them down, just as it had let them down after the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, as soon as they won (or claimed to have won) their global war against terrorism. To that end, Obama wanted to work with the democratically elected governments in Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight the Islamist groups that were posing a threat to them as much as to the United States. As president-elect, he had declared:

What I want to do is to create the kind of effective, strategic partnership with Pakistan that allows us, in concert, to assure that terrorists are not setting up safe havens in some of these border regions between Pakistan and Afghanistan. So far President Zardari has sent the right signals. He’s indicated that he recognizes this is not just a threat to the United States, but it is a threat to Pakistan as well. … I think this democratically-elected government understands that threat and I hope that in the coming months we’re going to be able to establish the kind of close, effective, working relationship that makes both countries safer.53

The Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act was passed in this context to move away from a military-centric relationship. Initiated by Senators Biden and Lugar, it was taken up by John Kerry and Lugar after Biden became vice president—hence its initial name, the “Kerry-Lugar Bill.” This piece of legislation was passed in 2009. The first three articles of the “Statement of Principles” section are worth quoting:

1. Pakistan is a critical friend and ally to the United States, both in times of strife and in times of peace, and the two countries share many common goals, including combating terrorism and violent radicalism, solidifying democracy and rule of law in Pakistan, and promoting the social and economic development of Pakistan.

2. United States assistance to Pakistan is intended to supplement, not supplant, Pakistan’s own efforts in building a stable, secure, and prosperous Pakistan.

3. The United States requires a balanced, integrated, countrywide strategy for Pakistan that provides assistance throughout the country and does not disproportionately focus on security-related assistance or one particular area or province.54

The Kerry-Lugar Bill was intended “to promote sustainable long-term development and infrastructure projects, including in healthcare, education, water management, and energy programs.”55 Supporting a bill that was passed unanimously by the Senate in September 2009, Senator Lugar dwelled on the fact that its objective was to shift from a security-centric to a development-oriented paradigm: “We should make clear to the people of Pakistan that our interests are focused on democracy, pluralism, stability, and the fight against terrorism. These are values supported by a large majority of the Pakistani people.”56

The aid that Washington committed to giving in the framework of this act amounted to $1.5 billion a year over the 2010–2014 period. The United States was no longer trying to pay (or equip) Pakistan so that the country would implement a certain security-related policy, but it was prepared to pay for Pakistan to make development a priority.

This approach was also different because it reflected a longer-term perspective—which was badly needed to correct the (not-so-wrong) impression prevalent among many Pakistanis that Washington was not a reliable partner because it was inconsistent. They had become a “disenchanted ally” (to paraphrase the title of Dennis Kux’s book) of the United States after they were let down by Washington in the 1990s, once the Soviets had left Afghanistan.

But the new American policy was a long-term one for another reason as well. The Obama administration considered that Pakistan was “the most dangerous country in the world.” This formula—which was first used by Bruce Riedel, a Brookings expert—was taken up several times during the 2008 presidential campaign by Joe Biden, the vice presidential candidate.57 What was at stake was not only nuclear proliferation, military expenditure, and adventurism but also the related issue of the rise of Islamism, something only a long-term effort to educate Pakistanis and make them richer could defuse. While the Bush administration—including his neoconservative hawks—had tried to fight terrorism by democratizing the Greater Middle East, Obama’s team concentrated on the country that mattered the most according to them and tried to support the democratization process by a special aid package.

One must not underestimate the affinities between the Bush administration and the Obama administration on that front. In both cases, there was a realization—resulting to a large extent from 9/11—that the real enemy was the Islamists. Holbrooke, in a Huntingtonian perspective, said about the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Al Qaeda, and the Taliban: “Their long-term objective is to destroy the Western civilization.”58 In Obama’s Wars, Bob Woodward cites James L. Jones saying similarly: “It’s certainly a clash of civilizations. It’s a clash of religions. It’s a clash of almost concepts of how to live.”59 But in contrast to the Bush administration, Obama wanted to combine short-United States become term security objectives with long-term support for the development of a democratic civil society in Pakistan.

In the Kerry-Lugar Bill, emphasis on the nonmilitary dimension of the U.S.–Pakistan relations to be promoted found its clearest expression in the last page of the bill where it was stressed that the allocation of the funds were conditional on the submission to Congress of a Semi-Annual Monitoring Report comprising “an assessment of the extent to which the Government of Pakistan exercises effective civilian control of the military, including a description of the extent to which civilian executive leaders and parliament exercise oversight and approval of military budgets, the chain of command, the process of promotion for senior military leaders, civilian involvement in strategic guidance and planning, and military involvement in civil administration.”60

This provision was unacceptable to the Pakistani generals who protested that the bill encroached on the country’s sovereignty.61 Other Pakistanis reacted more positively, even though many comments reflected a deep trust deficit.62 For many, it could be interpreted as a return to “colonial governance.”63 Daniel Markey attributes these reactions to the manner in which the bill had been rewritten by Representative Howard Berman for the bill to be passed in the House of Representatives—hence its abbreviation “KLB,” for “Kerry-Lugar-Breman.”64 For Markey, “the KLB rollout was a diplomatic disaster that hurt the U.S. effort to build ties with Pakistan.”65 It was, indeed, a failure but mostly because the United States was in a position neither to deliver civilian aid nor to reduce the security dimension of their collaboration.

THE MORE IT CHANGES … : THE RESILIENCE OF THE SECURITY PARADIGM (2009–2011)

Obama’s Pakistani policy immediately ran into a major contradiction: while it was apparently intended to focus more on development, it remained security oriented. The Pakistani army continued to be the main interlocutor of the United States—by default, given the weakness of the civilian authorities, but also by design, as security issues remained a priority.

IGNORING WEAK CIVILIAN LEADERS—AND MAKING THEM EVEN WEAKER

The Pakistani leaders, whom Obama had singled out as partners to build this new relationship, have been ineffective. Zardari—to whom Obama had sent a long letter offering that Pakistan and the United States become “long-term strategic partners”66 in November 2009—quickly lost most of his credibility due to his reputation for corruption and nepotism as well as his inability to relate to the Pakistani people, a problem partly resulting from his lifestyle and partly because of his fear of being killed by Islamists, which has transformed him into a recluse. According to a Pew Center survey, only 11 percent of interviewees had a favorable view of Zardari in 2011, compared with 20 percent in 2010, 32 percent in 2009, and 64 percent in 2008.67

But even when Zardari still enjoyed some degree of popularity, he was unable to prevail over the military. He did not manage to bring the ISI under civilian jurisdiction; he was not able to twist the arm of the army after he had offered to share intelligence with India about the 2008 Mumbai attacks—something the military bluntly refused; and he was unable to resist the demand of the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), Pervez Kayani, the successor of Musharraf, to obtain a three-year extension. Civilians were in office, but the army continued to rule—at least in key domains such as Pakistani policy toward Afghanistan, India, and nuclear weapons, all of which had major implications. As early as 2009, Hillary Clinton, the then secretary of state, “supported democracy in Pakistan but found the civilian government adrift,”68 an impression that was reinforced by the way with which “Zardari answered Obama with a wandering letter that the White House concluded must have been composed by a committee dominated by the Pakistani military and ISI.”69 Zardari spoke more and more like the military anyway.70

In any case, Hussain Haqqani had come to the conclusion that “On issues that mattered to the Americans, the civilians were simply unable to deliver.”71 What were these matters? All were security related, especially after the failed Times Square bomb blast on May 1, 2010, to which we shall return below.

Retrospectively, we may think that Washington should have resisted the temptation to adjust to the balance of power resulting from the growing assertiveness of the military at the expense of the civilians. But it did not happen and gradually, civilians (Richard Holbrooke, Hillary Clinton, Robert Gates, and Joe Biden) started talking to General Kayani—even when civilians were sitting at the table—and this practice precipitated the decline of civilian authority in the U.S.–Pakistan relations (and beyond). This attitude reflected the need for the Obama administration to deal with effective Pakistani leaders, but it was also an indication of the strong links between the Pakistani army and the Pentagon, which have always played a major role in this bilateral relation. These affinities were evident from the frequent—and apparently friendly—meetings between Kayani and Admiral Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 2007 to 2011. They both met twenty-six times.

NEGOTIATING WITH THE PAKISTANI ARMY

The weakness of the Pakistani civilian government made the paradoxical character of Obama’s strategy even more obvious, but there was anyway an intrinsic contradiction in this strategy. On the one hand, the Obama administration aspired to build a civil society that would sustain a more democratic regime in the long term. But its short-term priorities were of a completely different nature: like his predecessor, he wanted first to capture bin Laden and dismantle Al Qaeda and second to protect American troops fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan from attacks originating in Pakistan. To achieve these objectives, the Obama administration needed to rely on the Pakistani army, which was well trained in the art of bargaining with the United States about scores of issues to get “its due.”72

During the first year of his administration, Obama realized that the peace deals that the Pakistani army was making with militants in the FATA and adjacent areas did not offer any solution but gave these militants much needed respite to regroup before launching new offensives. The Pakistani army admitted that such an assessment was correct in 2009 when militants took over the Swat Valley. This time it reacted on a large scale and regained the upper hand in the valley.73 Then it launched an operation in South Waziristan, where it deployed about 28,000 soldiers, partly under American pressure, in late October 2009. The ratio to take on about 10,000 militants was so low that Richard Holbrooke wondered whether the Pakistani army wanted to “disperse” or “destroy” the enemy.74

Although the United States appreciated the military operations the Pakistan army launched in Swat and to a lesser extent in South Waziristan, it urged army leaders to do the same thing in North Waziristan, where they believed not only Al Qaeda leaders but also Taliban and the Haqqani Network were now based, sometimes after fleeing South Waziristan. These groups—especially the Haqqani Network—were allegedly planning not only strikes against NATO forces in Afghanistan but also terrorist attacks in the West as well—including on U.S. soil. The American military commander in Afghanistan, General Stanley McChrystal, exerted additional pressure on the Pakistani army in May 2010 after American investigators discovered that the failed bomb attack in Times Square had been plotted in the FATA.75

The Pakistani army, which had already lost thousands of soldiers in the FATA, was still reluctant to act. First, the Pakistani army and paramilitary were probably not in a position to fight successfully in a very difficult terrain—where civilians had already suffered considerably, giving the Pakistani state a bad name in the region. Second, the Pakistani army and the ISI were not willing to attack groups they considered useful allies to regain their lost influence in Afghanistan after the NATO forces would leave—especially since December 2009, when Obama announced not only the troop surge but that withdrawal of American troops would start in July 2011. Pakistan thus had to prepare for the Afghan transition, and groups such as the Haqqani would at that time be useful to reinstall the Taliban in Kabul to keep India at bay. Third, army operations in the FATA were widely considered the main reason for retaliation in the form of terrorist attacks in the main cities of Pakistan—where suicide attacks had never been as frequent as in the years 2009–2010.

As a result, the United States gradually came to the conclusion that they should ask the Pakistanis to let them handle the job themselves, with as much Pakistani support as possible. The American administration longed for the Pakistanis to allow them to undertake hot pursuit in the tribal area. They were rebuked by Islamabad, whose leaders—civilian as well as military—considered that such moves would encroach on the country’s sovereignty. But the United States obtained significant concessions in 2009–2010.

According to cables released by WikiLeaks and published in 2011 by the Karachi-based newspaper Dawn, as early as May 2009, the American ambassador in Islamabad, Anne Patterson, wrote to the State Department that the United States had “created Intelligence Fusion cells with embedded U.S. Special Forces with both SSG [Special Services Group] and Frontier Corps (Bala Hisar, Peshawar) with the Rover equipment ready to deploy. Through these embeds, we are assisting the Pakistanis to collect and coordinate existing intelligence assets. We have not been given Pakistani military permission to accompany the Pakistani forces on deployments as yet.”76 But by September, joint intelligence activities had been expanded to include army headquarters: “Pakistan,” Patterson said, “has begun to accept intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support from the U.S. military for COIN [counterinsurgency]. In addition ‘intelligence fusion centers’ had been established ‘at the headquarters of Frontier Corps and the 11th Corps and we expect at additional sites, including GHQ and the 12th Corps in Baluchistan.’”

In addition to these developments regarding intelligence sharing, in the late 2000s the United States obtained what it had dearly wished for: an intensification of drone strikes (a key point to which I’ll return below). The Pakistan army did not authorize the United States to strike on its territory explicitly and did not share intelligence in any open, unambiguous, and constant manner. On the contrary, in the spirit of a true client state, it extracted as much compensation as it could in terms of financial support and arms.

Arms delivery was an important concern to the Pakistani generals, at a time when the military collaboration between Islamabad and New Delhi was increasing. To have access to American weapons was a key component of their country’s credibility vis-à-vis India, and it was a prestige issue. Many deals were finalized under George W. Bush, but naturally, they spilled over into Obama’s first term. According to a congressional report, “in 2002, the United States began allowing commercial sales that enabled Pakistan to refurbish at least part of its fleet of American-made F-16 fighter aircraft and, three years later, Washington announced that it would resume sales of new F-16 fighters to Pakistan after a 16-year hiatus.”77 But F-16s were only the most symbolic items on the Pakistani shopping list. According to the Pentagon, sales agreements between both countries amounted to $4.55 billion over the years 2002–2007, the F-16s and related equipment representing a large fraction of this. In fact, the F-16 deal could be broken down into three components: eighteen new F-16C/D block 50/52 combat aircrafts with an option for eighteen more, amounting to $1.43 billion; about sixty midlife updated kits for F-16A/B, representing $891 million; F-16 armaments (including 500 air-to-air missiles and 1,450 2,000-pound bombs), representing $667 million. Other major defense supplies included eight P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircrafts and their refurbishment (worth $474 million), 100 Harpoon anti-ship missiles (worth $298 million), six C-130E transport aircraft, and twenty AH-IF Cobra attack helicopters (worth $163 million). The State Department had to justify these sales when they were paid for using American aid in the form of foreign military financing, on the grounds that they were “solely for counterterrorism efforts, broadly defined.”78

Members of Congress were skeptical about such arguments.79 In June 2006, the Pentagon notified Congress of arm sales worth up to $5.1 billion, including the eighteen newly built F-16s mentioned above. Members of Congress objected that these aircraft “were better suited to fighting India than to combating terrorists”80—to no avail. Two years later, a congressman belonging to the Indian caucus, Gary Ackerman, protested again that F-16s could hardly be used as counterinsurgency weapons—all the more so as some of these F-16s had been refitted to carry nuclear bombs).81 The State Department official who responded argued that this aircraft has become “an iconic symbol” of U.S.–Pakistan relations.82 Indeed, as Craig Cohen and Derek Chollet have rightly pointed out, “Although foreign military financing is often justified to Congress as playing a critical role in the war on terrorism, in reality the weapons systems are often prestige items to help Pakistan in the event of war with India.”83 This means that U.S.–Pakistan relations are again (or rather still) structured around forms of military cooperation intended, from Islamabad’s point of view, to cope with India.84 When the first batch of F-16 jets arrived in Pakistan in July 2010, one of the officials receiving them commented upon this delivery in unambiguous terms, “Look at the rival [India]. How many fighter jets they are purchasing?”85

Although the Obama administration would have probably been less inclined to sell as many arms as its predecessor did, especially given Congress’s growing objections, it delivered them—in early 2010, the United States approved the delivery of twelve Lockheed Martin F-16Cs and six F-16Ds—and finalized other agreements that the Pakistani army greatly appreciated. For the Pakistani generals, in addition to military equipment, the fact that some of their officers could receive training in the United States was very much valued. In 2009–2010, eight Pakistani air force members spent ten months in Arizona to be trained to fly the new F-16s.86 These pilots were the first Pakistani officers to receive training in the United States since 1983.

When Washington showed reluctance and when the growing pervasiveness of anti-Americanism in Pakistan further complicated army collaboration with the United States, Islamabad hardened its attitude. In October 2010, it claimed that the country’s sovereignty had been violated by a NATO helicopter that had crossed the Durand Line and killed two Pakistani soldiers and one paramilitary in Kurram,87 and it decided to stop the flow of supplies to NATO forces in Afghanistan through the Torkham area. This move was clearly intended to remind the United States of its vulnerable position as regards its troop supply lines—all the more so as convoys attempting to use an alternative route were attacked.88

This “incident” and the growing tensions between the United States and Pakistan (Islamabad was then resentful of Obama’s decision to visit India and not Pakistan the following month) precipitated the organization of a strategic dialogue. By holding such a meeting in Washington, the U.S. government recognized that the Pakistani generals had to be its main interlocutors for all security matters it regarded as a priority. The Pakistani army came away with a $2 billion military aid package. This amount was similar to the $1.5 billion in security-related aid the United States already granted Pakistan every year, but it was “a multiyear security pact,” which, according to an American official, meant a lot to the Pakistani army: “This is designed to make our military and security assistance to Pakistan predictable and to signal to them that they can count on us.”89 The new security pact comprised three parts: the sale of American military equipment to Pakistan, a program to allow Pakistani officers to study at American war colleges, and counterinsurgency assistance to Pakistani troops.

This $2 billion package came at a time when money had become an issue between the Pakistani army and the United States. Until 2007, most of the annual bills submitted to the United States for an amount of about $1 billion were paid without question. The rejection rate was only 1.5 percent in 2005. It rose to about one-third in 2007 and jumped to 38 percent in 2008 and 44 percent in 2009. What was at stake were “the claims submitted by Pakistan as compensation for military gear, food, water, troop housing and other expenses.”90 The 2010 $2 billion package was clearly intended to restore some measure of trust between the Pakistani army and the Obama administration. This deal was important because at that time more than before, it seemed, according to Hussain Haqqani, that “for Pakistanis, the money was never enough. Every now and then, Pakistani officers showed up with charts to illustrate the presumed economic loss the country suffered because of terrorism and the war against it.”91

To sum up: one year after the Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act was passed, the Obama administration was conforming to the old pattern defined above as a security-oriented form of clientelism. The emphasis remained on military cooperation. The April 2011 White House quarterly report on Afghanistan and Pakistan devoted more space to the military agreement than to civilian projects.92 The paragraph regarding the agreement signed during the October 2010 U.S.–Pakistan Strategic Dialogue is worth citing in extenso:

The [U.S.] commitment includes a request to the Congress for $2 billion in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and $29 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET) funding over a 5-year period (Fiscal year 2012–2016). FMF provides the foundation for Pakistan’s long-term defense modernization. In addition, the IMET commitment will allow Pakistani military personnel the opportunity to train alongside their U.S. counterparts, which will help create deepened personal relationships and enhance our strategic partnership. IMET funding was suspended along with other security assistance during the decade-long period of Pressler Sanctions, depriving a generation of Pakistani officers of an opportunity to attend courses in the United States that impart our values for civilian control of the military, human rights, military organization, and operational planning, among other things.93

The emphasis on long-term collaboration, which until then had applied to civilians, here concerns the military, with a goal of modernizing the Pakistani army—never officially mentioned before—and providing training. Ironically, the report suggests that human rights protection will be enhanced by U.S.-trained army officers. In contrast, the report admits that the civilian dimension of the U.S.–Pakistan relations is lagging behind: while the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act provided for the spending of $1.5 billion a year for civilian projects, “the United States Agency for International Development [USAID] has disbursed $877.9 million in civilian assistance since the passage of Kerry-Lugar-Berman legislation in fall 2009, not including humanitarian assistance. While some new programs are underway, it will take time for other projects, particularly large infrastructure projects, to be fully implemented.”94 Ambassador Robin Raphel, who had been appointed “coordinator for nonmilitary assistance in Pakistan” in 2009, admitted two years later that “it was unrealistic to think we could spend such a large amount of money so quickly.”95 Daniel Markey attributes this failure not only to the fact that USAID was not able any more to handle such a sum but also to the tensions between this institution and Holbrooke, until his untimely death in December 2010.

The contrast between the financial effort in favor of the military and the civilian sector is obvious in table 8.1. The nonmilitary component of U.S. assistance to Pakistan represented only 33.8 percent of the total in 2007 by the end of the second term of George W. Bush, whereas it has reached about 45 percent in 2009 and about 40 percent in 2010. And with $2.735 billion in 2010, the military component was almost the double of what it was, as an average, during the second term of George W. Bush.

On the top of it, the Obama administration overlooked the conditionalities that were supposed to be part of the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act. This act required the secretary of state to certify that Pakistan fulfilled certain criteria regarding noninterference with the civilian processes, sharing of intelligence with the United States regarding Islamist networks, cessation of any form of support to the Afghan Taliban, and so on. The secretary of state had to provide certification every year for the money to be disbursed. When she occupied this post, Hillary Clinton delayed the assessment exercise and, eventually, gave her certification on March 18, 2010, considering that Pakistan was in compliance with all the conditionalities—something senior American officers themselves contradicted privately, especially after the Pakistani authorities’ actions taken against CIA staff members and their demand for a drastic reduction of the Special Forces (see below). The Obama administration preferred to look the other way so as not to alienate the Pakistani generals.

“MASTERS, NOT FRIENDS”? THE CRISIS OF U.S.–PAK RELATIONS (2011–2013)

The standard clientelistic model was based on a form of subcontracting: the American patron paid the Pakistani authorities in exchange for the performance of certain tasks. In this exchange, Pakistan retained a certain degree of autonomy. The country’s sovereignty was admittedly encroached upon in the 1950s–1960s with the installation of U-2 bases to which Pakistani officials themselves were denied access. But Ayub Khan made sure that the Americans behaved as “friends, not masters”—a phrase he used for the title of his autobiography, which significantly devoted considerable space to U.S.–Pakistani relations.96 As a result, after Russia identified Pakistan as the country from which the U-2s were coming, the lease granted by Islamabad for the base in Badaber was not renewed—and the base was shut down in 1968. More important in the 1980s, the golden age of U.S.–Pakistan cooperation, Islamabad had been given considerable leeway, enabling it to promote the groups of Afghan mujahideen it considered with favor. In the 2001–2008 period, the Bush administration also gave Musharraf a degree of latitude and tried to balance out the India–U.S. rapprochement by cozying up to Pakistan. Obama has behaved differently. Not only has he choked the Pakistanis by conflating them with the Afghans (at best perceived as good mujahideen but rustic tribals by the Punjabi establishment) in the expression “AfPak”—and Pakistanis resented the trilateral summits the United States hosted with Pakistan and a pro-India Afghanistan under Karzai—but furthermore, he has made no secret of his preference for India as strategic partner in South Asia and attached little importance to Pakistan’s sovereignty as evident from his intensive use of drones.

DRONE ATTACKS

For many Pakistanis, the drone attacks have become a symbol of the way the United States has disregarded their country’s sovereignty. These attacks had already started under the Bush administration. In fact, the WikiLeaks cables show that as early as January 2008, Kayani was asking the United States for some Predator coverage in South Waziristan while his army conducted operations against militants. According to K. Alan Kronstadt, a specialist in South Asian affairs at the Congressional Research Service, in April 2008, three Predators were “deployed at a secret Pakistani airbase and can be launched without specific permission from the Islamabad government.”97 Although the drone strikes increased in 2008, they were ramped up dramatically under President Obama. In fact, “in its first eighteen months, the Obama administration authorized more drone attacks in Pakistan than its predecessor did over two terms.”98 In 2010, these attacks focused on North Waziristan, where militants had regrouped after the South Waziristan operation the year before. The number of drone strikes in this region rose from 22 in 2009 to 104 in 2010.99 The London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism estimated that less than one-third (714) of the 2,400 to 3,888 persons killed by the 405 drone attacks in Pakistan from 2004 to December 2014 have been identified.100 Indeed, most of the official American figures leave civilian casualties unrecorded.101 According to the New America Foundation’s drone database, considered the most accurate source, the number of drone strikes increased from 9 over the years 2004–2007 to 33 in 2008, 53 in 2009, 118 in 2010, and 70 in 2011. For the Foundation, “the 310 reported drone strikes in northwest Pakistan, including 27 in 2012, from 2004 to the present have killed approximately between 1,870 and 2,873 individuals, of whom around 1,577 to 2,402 were described as militants in reliable press accounts. Thus, the true non-militant fatality rate since 2004 according to our analysis is approximately 16 percent. In 2011, it was more like eleven percent.”102 Steve Coll gives similar figures so far as the civilian casualties are concerned: “In Obama’s first year in office, the figure was twenty percent—still very high. By 2012, it was five per cent.” But major blunders were still committed (forty-one tribal elders taking part in a jirga were killed by mistake in 2011, for instance). And this is one of the reasons why, by mid-2012, Obama had ordered John Brennan (the deputy national security advisor for homeland security and counterterrorism and assistant to the president) to reassess the drone policy. The number of drone strikes diminished and was further reduced after Brennan became chief of the CIA in 2013.103 According to the New America Foundation, the number of strikes has fallen from seventy-three in 2011 to forty-eight in 2012, twenty-seven in 2013, and twenty-one in 2014, and the number of casualties has followed the same trend: 849 in 2010, 517 in 2011, 306 in 2012, 153 in 2013, and 138 in 2014.

Targeted killings were the chosen method for decimating the Islamist network—and remained so to some extent. Already in June 2004, Nek Mohammad was killed by a missile launched from a Predator. Baitullah Mehsud met the same fate in August 2009. But many civilians—and even Pakistani soldiers—died, too,104 and civilian casualties were one of the reasons for the American unpopularity among the Pakistani people.105 This is why the Pakistani army made a point of systematically voicing vehement protest against drone operations.

THE RETALIATION–COUNTERRETALIATION CYCLE

In addition to drone strikes, the presence of American agents on Pakistani territory has increasingly been perceived as attacks against the sovereignty of Pakistan by Islamabad and Rawalpindi. The Pakistani authorities sent a signal to the United States by leaking to the media the name of the Islamabad-based CIA station chief in December 2010. The agent immediately received death threats and left the country. CIA contractors presented an even bigger problem. The Obama administration had authorized a considerable number of CIA agents to be sent to Pakistan,106 many of them as “contractors,” dispensing Washington from having to reveal their true mission to the government in Islamabad. And Pakistan apparently issued hundreds of work visas without realizing that it was granting residency permits to American spies. (Besides CIA agents, contractors of Xe (formerly Blackwater)—a private security firm [in]famous for its role in Iraq—was active in Pakistan. In 2009 a former U.S. official revealed that Blackwater people worked on a CIA base in Baluchistan.)107

In January 2011, one of these CIA contractors, Raymond Davis, killed two Pakistanis who, according to him, were trying to steal something from him while he was driving in Lahore. He was arrested and the Pakistani authorities refused to release him for one month in spite of intense pressure from the American ambassador, who argued that he was protected by diplomatic immunity. He was eventually freed and allowed to return to his country, probably in exchange for financial compensation to the victims’ families (even though the American authorities denied any payment) and for the American promise of reducing the number of Special Forces and CIA agents/contractors.108

THE OSAMA BIN LADEN RAID

On May 2, 2011, the raid in Abbottabad that ended in the killing of bin Laden showed that the Americans continued to conduct a number of activities in Pakistan that encroached on the country’s sovereignty. First, it would not have been possible to locate bin Laden’s residence in Abbottabad without intense activity on the part of U.S. intelligence agents that the Pakistani authorities were apparently unaware of. Above and beyond that, the CIA could secretly approach and recruit a health official, the surgeon general in Khyber Agency, Shakil Afridi, to scout out the location under cover of a vaccination campaign.109

Second, the operation code-named “Geronimo”—involving twenty-three Navy SEALs from the Naval Special Warfare Development Group and a half-dozen helicopters (including two MH-60 Black Hawks)—apparently left from the American base in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, and crossed the Pakistani border in secret. Certain Pakistani officials, such as the ambassador to London110 and ISI officers,111 claimed that their country had been involved in the operation in which bin Laden was killed, but others, higher ranked, starting with President Zardari—all too eager to seize an opportunity to criticize the army (at least for incompetence)—said they had not been informed of the operation,112 which thus constituted a violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty. Their denials can doubtless be explained by the unpopularity of such an operation in public opinion. But several American sources “confirmed” that the United States did not want to let the Pakistanis in on the secret.113 Hillary Clinton and, more cautiously, Barack Obama, were careful not to offend the Pakistanis by suggesting that they had helped the United States to locate bin Laden,114 but Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Michael Mullen apparently did not let Kayani in on the whole operation until three o’clock in the morning of May 2.115 An Obama advisor even told the New Yorker: “There was a real lack of confidence that the Pakistanis could keep this secret for more than a nanosecond.”116 As for Leon Panetta, chief of the CIA, he clearly stated that the Pakistanis had been kept in the dark in surprisingly explicit terms: “Any effort to work with the Pakistanis could jeopardize the mission. They might alert the targets.”117

The Pakistani authorities—who had first suggested that this operation had been jointly organized by both countries—protested against the unilateral incursion of American helicopters from Afghanistan without any official clearance,118 claiming that it was a violation of national sovereignty. In a short communiqué, “the chief of army staff made it very clear that any similar action, violating the sovereignty of Pakistan, will warrant a review on the level of military/intelligence co-operation with the U.S.”119

The Pakistani army reacted particularly badly to Operation Geronimo for three reasons. First, the presence of bin Laden in a city only 75 miles from Islamabad, which houses a military academy and where several retired officers reside, fueled suspicions as to possible complicity as well as allegations of incompetence: either the general staff knew and was guilty of collusion, or it did not know and doubts about its professionalism were thus warranted. Second, the civil authorities, starting with President Zardari and one of his close associates, Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington, Hussain Haqqani, stood to gain from this military’s fiasco (as the “Memogate” episode will show below), while pointedly congratulating the Americans.120 Third, Operation Geronimo, if conducted as reported above, attested to the ease with which the Americans penetrated Pakistani territory, again in disregard for the country’s sovereignty.

In reaction, the army arrested five Pakistanis who helped the Americans plan Operation Geronimo, including Dr. Afridi, who has been sentenced to jail for thirty-three years for high treason—the ISI wanting to make an example out of him. Pakistan also asked the United States to vacate the Shamsi Air Base in the Baluchistan desert, although it was an important location for the drone operations in the tribal area.121

“HOT PURSUIT” AND “FRIENDLY FIRE”

Back in the early 2000s, NATO troops wanted to pursue assailants in Afghanistan who took refuge across the Pakistani border after their attacks. The Pakistani authorities denied them permission for such “hot pursuit” actions, as they are known, because Pakistan wanted to avoid foreign military presence on its soil and to monitor on its own a border that was already extremely sensitive given Afghanistan’s refusal to recognize the Durand Line. Although incursions were rare, blunders were less so. U.S. soldiers pursuing Islamists to the “border” or merely patrolling along this imaginary line—more imaginary in this case than any frontier—have mistaken their target a number of times and opened fire on Pakistani soldiers. Each incidence of such “friendly fire” has given rise to reactions of public opinion. In the month of June 2007, opposition members walked out of the National Assembly to protest against an incursion of American troops on Pakistani soil that left thirty-two dead.

In June 2008, eleven Pakistani soldiers were killed by American “friendly fire,” and in September an even more deadly operation took place in Angoor Ada, South Waziristan, where three helicopters searching for terrorists killed nearly two dozen people—including women and children—among whom there was not a single Islamist. In retaliation, Pakistan blocked convoys supplying NATO troops with gasoline for an unlimited period, which turned out to be fairly short.

Two years later, in another blunder, two Pakistani soldiers were killed. But the most serious incident took place in Salala in November 2011. This Mohmand Agency checkpoint in the FATA on the Afghan border was the target of strikes from helicopters and fighter planes that lasted several hours and left twenty-four Pakistani soldiers dead.122 This time, the Pakistani authorities appointed a commission of inquiry and closed all NATO supply lines between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

All of the above-mentioned factors—from drone strikes to “friendly fire”—are largely responsible for the growing unpopularity of the United States in Pakistani public opinion in recent years.123 According to a Pew Research Center study published in July 2010, 59 percent of the Pakistanis interviewed described the United States as an enemy and only 11 percent as a partner. Only 8 percent expressed confidence in Obama—a record figure, as none of the other twenty-one countries included in the opinion survey had such a poor image of the American president.124 This anti-Americanism partly explains the rising influence of the party led by Imran Khan, former national cricket team captain turned political leader, whose opposition to the United States is his hobby horse. The common denominator for all these factors for Pakistan’s rejection of the United States lies in the fear of compromising the country’s sovereignty. This dread—shared by a large number of Pakistanis, even among Westernized elites—has led some of them to reconsider the Kerry-Lugar-Berman Bill in this light. Thus, the South Asia Strategic Stability Institute, a think tank with ties to the military establishment (and the ISI) came out in favor of rejecting it, not only because it limited the army’s margin for maneuver, but also because it would allegedly prevent the country from defending itself. Considering that according to the terms of this law, “Pakistan is not allowed to buy any defense articles without the due approval of the President of the United States, Secretary of State or the Secretary of Defense of U.S.,” accepting the bill would amount to a “freeze on the nuclear weapons program and will result in the Pakistani nuclear deterrence as irrelevant for all future conflicts.”125 The distrust of not only the hawks in the security apparatus toward Americans but many Pakistanis in general is rooted in the prevalent view that the reason for the U.S. presence in their country is less the fight against Islamist terrorism than supervision of their leaders, starting with Zardari, and even the takeover of their nuclear arsenal.

THE INDIAN FACTOR

Although the bin Laden raid, the Raymond Davis episode, and the Salala “friendly fire” badly affected U.S.–Pakistani relations in 2011, they had started to deteriorate in late 2010. At that time, one of the factors of this evolution was India related. For decades, Islamabad considered Washington as one of its key supporters in its competition with its big neighbor, but it realized in the post-9/11 context that the United States would, in fact, contribute more to the widening of the gap between India and Pakistan, instead of promoting “parity” (a key word of the Pakistani vocabulary). That conclusion became particularly clear in November 2010, during Obama’s official visit to India, at a time when, according to the annual Pew survey, 53 percent of interviewed Pakistanis considered that India posed the greatest threat to their country—compared with 23 percent who said the same about the Taliban. Indeed, Pakistan was particularly antagonized by the Indo-U.S. rapprochement, which had already resulted in the 123 Nuclear Agreement (2008). The military in particular viewed “the U.S. operations in Afghanistan with suspicion, not least because they perceive the post-2002 government in Kabul as being overly friendly towards New Delhi.”126