Farah Jan and Serge Granger

Pakistan’s foreign policy from the onset was formulated along the lines of its (in)security concerns, and relations with China are framed under the same rubric. These two states share a unique relationship that has remained consistent over the years, despite variations across time and issues. In Pakistan, the perception of China is of an unfaltering “all-weather friend” and a reliable ally, regardless of regional and global circumstances. Similarly, for China, Pakistan is a “permanent friend.”1 Many scholars2 have argued that Pakistan–China relations are inspired by their mutual rivalry with India, and more recently the argument has revolved around containing India. This chapter attempts to expand on the existing literature by arguing that Pakistan, since the very beginning, has looked to a stronger partner for protection. In the process, it has oscillated between the United States and China. Thus, two questions come to the fore in regards to this relationship: First, keeping Pakistan’s security concerns in mind, why did Pakistan alternate between the two great powers, and for what kind of gain? Second, is the Pakistan–China relationship a pragmatic expression of containing India to foster China’s regional supremacy?

In international politics, states with significant external threats either balance against the threatening power to deter it from attacking or bandwagon by aligning with the threatening state, in order to appease it.3 This chapter seeks to address the above questions by situating Pakistan’s alignment behavior in this literature. When reviewing Pakistan and China relations, we would be remiss to overlook the India nexus in this alliance. India plays an important role in the strategic defense aspect of this relationship.

JOINING HANDS AGAINST INDIA

From a historical standpoint, China’s partnership with Pakistan emerged at a time when it was looking for support on the global stage; this partnership intensified in the 1960s during the Sino-Indian War and since then has continued to thrive even after the Sino-Indian rapprochement.4 The vitality and durability of this relationship is what perplexes scholars and prompts us to explore the depth of this partnership. As noted by John Garver, “China’s partnership with other countries, both large (USSR and US) and small (Albania, Vietnam, Algeria, and North Korea) have waxed and then waned, but with Pakistan it is indeed a remarkably durable relationship.”5 Similarly, for Pakistan, friendship with China is considered one of the cornerstones of its foreign policy. The foundation of this alliance is further grounded in economic, defense, geostrategic, and people-to-people relations between the two states. This bond is continuously cultivated by means of bilateral trade and cooperation; military-to-military exchanges and transfer of critical defense technology; and support and development of conventional weapons and other major Chinese investments in Pakistan. Despite the absence of cultural similarities and common values, this alliance has remained strong, as noted by Andrew Small: “Sino-Pakistani ties have proved remarkably resilient. … Across the last few decades they have survived China’s transition from Maoism to market economy, the rise of Islamic militancy in the region, and the shifting cross currents of the two sides’ relationship with India and the United States.”6

It is important to highlight that it was India and not Pakistan that initially warmed up to China following the establishment of the communist regime in 1949. India, like Pakistan, had gained independence in 1947 and was emerging on the global stage. The newly established states were foraging for international support, whether that included economic, military, or diplomatic blessings. The contrast between the two states was that Pakistan was quick at latching on to the West, and India adopted a policy of nonalignment. It is at this point in history that we start seeing Pakistan looking for a strong partner to ease its security concerns. It was under these conditions that Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited China. He was mindful of China’s rise: as he cautioned, “A new China is rising, rooted in her culture, but shedding the lethargy and weakness of ages, strong and united.”7 Nehru’s prophecy encompassed a sense of warning, which was later affirmed by the assertions of India’s China expert K. M. Panikkar. Panikkar was perturbed by the new developments in China, and he noted an apparent arrogance and ruthlessness in the new masters of China.8 Hence, in his opinion, it was important for India to extend cordial relations toward China. India, aware of its rivalry on its western border with Pakistan, aspired for friendly ties with a powerful neighbor on its northern periphery and thus hoped for an India–China axis in South Asia to pacify its own insecurities.

To appease China, the Indian delegate to the United Nations in September 1950 advocated admitting communist China’s representation to the United Nations.9 This measure had a twofold strategy: first, it aimed to strengthen India’s ties with China, and second, it hoped that this maneuver would gain Chinese support in regard to Kashmir. During this period, India backed China’s position on Taiwan, but China maintained an equivocal position on Kashmir.10 The Kashmir conflict raised four concerns for Beijing. First, the conflict destabilized the border and could spark unrest in Xinjiang. Second, an Indian victory in Kashmir enhanced Indian power, which had interests in Tibet, confirmed by Nehru’s intention to provide asylum to the Dalai Lama. Third, Indian pretentions on Kashmir included Aksai-Chin, a region considered essential for the Chinese who began constructing the Xinjiang–Tibet border road. Finally, an Indian victory would sever a Chinese–Pakistani land border, instrumental in putting military pressure on India.

THE PAKISTAN–CHINA–U.S. TRIANGLE—AND THE INDIA NEXUS

To explicate the variations in Pakistan–U.S. and Pakistan–China relations, Pakistan’s foreign policy could be viewed in two phases: from independence until 1971 and a post-1971 era. Pakistan’s alignment pattern from the very beginning has been to align with a stronger partner—alternating between the United States and China. After the postwar years, at the time of Pakistan’s birth, the United States emerged as the sole superpower—albeit for a short while. Pakistan’s foreign policy orientation at that time was toward England. As pointed out by a retired Pakistani ambassador, “England’s orientation at that point was towards the U.S. Hence, the existing Pakistan army establishment at that point was British trained, and they were simply toeing the line.”11 One of the reasons for this pro-British attitude was the background of the policymakers. The political elites of the time were not only British educated but also served in the British government.12 The British influence along with the security search pushed Pakistan to align itself with the West, particularly with the United States, which emerged as an indomitable power after World War II.

Ties with China were established in January 1950, when Pakistan became the third noncommunist state to recognize the People’s Republic of China. Diplomatic links followed a year later, and one can argue that the first ten years of this relationship were insignificant in comparison to the later years. Pakistan in the 1950s had ascribed to the Western logic of “godless communists” and considered communism the “biggest potential danger to democracy in the region.”13 China’s response was subdued, hopeful that Pakistan would follow principles of peaceful coexistence.14 Premier Chou-En Lai put these principles forward, in 1955, at the Bandung Summit. It should be remembered that when the Five Principles of China’s regional policy were institutionalized, the United States at that point was engaged in its containment policy. For China, this was a pragmatic approach to give its neighbors the impression that its policy was based on principles, whereas others were driven by self-interest.15 China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (Panchsheel) are mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity; mutual nonaggression; mutual noninterference in internal and external affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence.

It is important to take into account the Cold War dynamic that dominated the world stage at that time. The U.S. anticommunist coalition in Asia and the Middle East was at full throttle. It was in the 1950s that Pakistan was espoused by the United States as its ally in this mission. For Pakistan, this was an opportunity it could not turn down, considering future military gains and benefits. Accordingly, these aspirations were fulfilled when Pakistan requested assistance and President Eisenhower in 1954 extended the much needed aid.16 Thereafter, Pakistan and the United States signed multiple bilateral defense agreements, and Pakistan joined the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization and the Central Treaty Organization. India viewed Pakistan’s alignment with the West and its military fortification as a threat. China had a similar perspective on Pakistan’s association with the West: Pakistan’s military agreements were considered to be a threat to China, India, and the region. For Beijing, responding to the 1959 Pakistan–U.S. bilateral defense agreement, this was Washington’s iniquitous design of encroachment on the region. Despite bilateral agreements, China had a sense of assurance in regards to Pakistan and did not fear aggression from Pakistan; instead, it was apprehensive of U.S. motives.17 Furthermore, China was mindful of Pakistan’s insecurity vis-à-vis India and considered Pakistan’s alignment with the United States a measure to ease its anxieties in regards to its military weakness in contrast with India.

The United States in the early days of the Cold War had a political stake in the stability of both India and Pakistan, because it did not want either of these countries to come under communist influence. The United States feared worldwide repercussions and even alluded to it in the National Security Council Report in 1959: “Seriously increased political instability in either or both of these large nations could significantly increase Communist influence in the area, or alternatively, might lead to hostilities in South Asia. Either turn of events could engage great power interests to the point of threatening world peace.”18 The shift in Pakistan–U.S. relations came in 1959 when Senator John F. Kennedy advocated support toward India’s development in order to balance power relations in South Asia against China. India’s neutral stance was defended with parallels drawn with nineteenth-century America during its formative days.19 This attitude was disconcerting for Pakistan and created a breach of trust with the United States. From this point onward, decision makers in Pakistan changed directions from the West to the East—from the United States and its Western allies, to China, a trustworthy guarantor.

As the decade came to an end, India–China relations deteriorated and Pakistan systematically warmed up to China. Since the early 1960s, Pakistan–China ties have remained strong and cordial, irrespective of regional and international circumstances. The isolation of China in the 1950s and 1960s nurtured a foreign policy aimed at securing allies, which would outnumber those who recognized Taiwan at the United Nations. With the movement of decolonization unrolling, ties with Pakistan became an exemplar of Chinese dialogue with new independent Muslim countries that had just obtained their independence and were en route to self-government. China was in need of diplomatic recognition to enter the United Nations and would gather more support from newly independent countries. Afghanistan recognized China in 1955; Egypt, Syria, and North Yemen did so the following year. By the late 1950s, Iraq, Morocco, Algeria, Sudan, and Guinea had also normalized relations with Beijing. Somalia, Tunisia, and South Yemen followed in the 1960s, while Iran and Turkey joined in days before the entrance of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations. China would find in Pakistan a worthy partner in vindicating it to other Muslim countries that friendly relations were possible with a communist, agnostic China, notwithstanding its rocky relationship with Indonesia, the most populous Muslim country in the world.

China’s border negotiation with Pakistan was on a relatively small borderline of 310 miles, and Pakistan gained much from border negotiations. China recognized Pakistani control over parts of Kashmir, therefore thwarting India’s claim on the land. Conversely, border disputes with India initiated in 1958 contributed to the Sino-Indian War of 1962. China refused to accept the boundary line drawn by the British and argued that “no treaty on the boundary has ever been concluded between the Chinese central government and the Indian government.”20 On October 20, 1962, China launched an offensive strike, which took the Indian army by surprise. Prime Minister Nehru announced in a radio broadcast a series of defeats in the battle against China. This in the view of many scholars was a cruel awakening for the newly established state well cognizant of foreign domination. After its first defeat, India asked for military help from Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union. The United States and Britain offered and provided immediate assistance. By November 1962, Nehru publicly conceded, and a unilateral withdrawal was made on the condition that India would accept the neutralized zone delineated by China, and furthermore India was prohibited to reestablish any military posts in the Ladakh region. For Pakistan, this was a golden opportunity to condemn India, but at the same time it felt betrayed by the United States and its Western allies who provided immediate support to India. President Ayub Khan blamed the Indian government for being aggressive and not conciliatory in regards to its border dispute with China. From his perspective, the Indian ambition of becoming the great power in Asia forced the Chinese to humble them.21 It is this critical juncture of 1962 that is considered to have set the trajectory for Pakistan–China relations for years to come.

Since the independence of Pakistan and India, South Asian history has continuously been overshadowed by the Indo-Pakistan rivalry, hence affecting regional and international policies and alliances. Whereas India fought a war with China over a border dispute, Pakistan decided to negotiate an agreement on the border between China’s Xinjiang Province and Pakistan’s Gilgit and Hunza areas.22 Many Western analysts argued that the Chinese were generous in their border dispute with Pakistan, in order to “woo the Pakistanis from their Western commitments and above all to prove to the Indians how much they are missing by not coming to terms.”23 While Sino-Indian relations diverged, Sino-Pakistan relations were transformed and turned into a special alliance.

Beyond the goodwill and collective interest of both China and Pakistan, the two states also inked substantive agreements starting from 1963 onward. Border issues were settled, and Pakistan was the first noncommunist state to sign a trade agreement with China. The landmark air agreement, in which landing permission for Pakistan International Airlines was granted without conditions, was considered a major triumph for Pakistan.24 The air agreement further contributed to strained relations between the United States and Pakistan; it was a measure against the isolation of China that the United States tried to promote.

During the Sino-Indian War of 1962, Pakistan–U.S. relations tailed off, after the United States expeditiously honored the Indian request for military assistance.25 For Pakistan, this was a betrayal of its position as a Western-aligned state, whereas India had maintained a nonaligned status all through the Cold War. Relations with the United States were further damaged during the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965, during which Washington halted all military aid to Islamabad and New Delhi. China during this time frame patiently watched this relationship wax and wane. The aphorism “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” applies fairly to this case.

It is important to highlight China’s stance in the two major events ensuing after the Sino-Indian War: the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 and the disintegration of East Pakistan in 1971. Both in 1965 and in 1971, China backed Pakistan’s position over India’s. In the 1965 war, China considered India to be the aggressor and held it solely responsible for the conflict. Beijing denounced and condemned the Indian attack as an “act of naked aggression.”26 China played a major role in the cease-fire dialogue between the two rivals and maintained a degree of military pressure on its borders of Sikkim, Bhutan, and the Northeast Frontier Agency for several months following the cease-fire. This measure by the Chinese was seen by many as furnishing Pakistan with a strong negotiating position vis-à-vis India.27 The Chinese assistance during the Indo-Pakistan War symbolized a new beginning for this friendship, in which China further proved its dependability and consistency. These were the attributes that the United States failed to demonstrate, and thus it led to the divergence of paths of “the most allied allies.”

The 1971 civil war situated the Chinese in a twofold predicament in which they disagreed with General Yahya Khan’s brutal military actions in East Pakistan as well as with the East Pakistani rebel’s ties with India. China’s response to the 1971 disintegration of Pakistan was much weaker than its support in the earlier war with India. Publicly China concentrated on condemning India for “open interference in the internal matters of Pakistan.” In a statement issued in April 1971, the Chinese government assured its “support for Pakistan and its people in their just struggle to safeguard state sovereignty and national independence.”28 But privately, they were very uncomfortable with the situation in East Pakistan. As John Garver noted, the Chinese were critical of the ruthless measures exercised to deal with the rebels of East Pakistan; on a public level, they did not endorse Pakistan’s actions but directed critical opprobrium toward India’s direct involvement and infiltration in Pakistan’s Eastern Wing.29

China’s response in 1971, compared with 1965, differed in its degree but not in its position toward Pakistan. This still leaves open the question of what led to the variation in the Chinese position. As Andrew Small noted, the 1971 episode made it clear that “China would not pull Pakistan out of the holes it insisted on digging for itself.”30 In addition, China at that point was worn out by its cultural revolution and was focused on its economic development along with a rapprochement with the United States. Although China did not militarily assist Pakistan, Beijing nevertheless provided diplomatic support at the UN Security Council by vetoing Bangladesh’s application for UN membership until Pakistani prisoners of war had been returned and Indian troops had withdrawn.31

In response to Pakistan’s serious efforts toward Sino-American détente and its role as an intermediary in the Sino-American dialogue that led to President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, China provided support to Pakistan during the post-Bangladesh crisis. The statement issued in the joint U.S.–China Communiqué of 1972 expressed “firm support for the government and people of Pakistan in their struggle to preserve their independence and sovereignty, and the people of Jammu and Kashmir in their struggle for the right of self determination.”32 This statement on the surface translates into Beijing’s continued support of Pakistan’s interests, but talk is cheap and actions are costly. China’s lackluster support for Pakistan during the 1971 crisis set the precedent for future expectations that Beijing would not militarily intervene on behalf of Pakistan.

Pakistan’s reaction to China’s response was politely stated by Z. A. Bhutto during an interview: “We have not lost confidence in China’s friendship, nor in China’s word.”33 Bhutto was aware of the long-term gain from the Pakistan–China relationship, in which China had shown interest in Pakistan’s security and respected Pakistan’s domestic political situation.34 China had become the most reliable suppliers of military equipment and also aided Pakistan’s defense industry. Even during the Bangladesh crisis, China provided Pakistan with large shipments of arms in East Pakistan, along with $100 million in assistance.35 The Russian invasion of Afghanistan would bring back American aid to Pakistan, but it would disappear once more after the Soviets had retreated and suspicion rose about Pakistan’s nuclear plans involving China. During the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, China and the United States cooperated in opposing the Soviets, but China’s support was based on two reasons: the Soviets were looking for expansion in Beijing’s backyard, and Soviet troops were seen primarily as a threat to Pakistani security. At that point, the policies and stances of China and Pakistan were coordinated to such an extent that General Zia declared on his visit to Beijing in 1980 that “Pakistan and China have a perfect understanding in all fields.”36

By “all fields,” Zia alluded to the greatest possible military relationship: Pakistan and China’s nuclear agreement. China’s involvement in Pakistan’s nuclear program was crucial and “one of the most heavily guarded secrets.”37 Yet it was not Zia but Z. A Bhutto who secured the remarkable nuclear deal with Mao in 1976, when China agreed to transfers 50 kilograms of uranium to Pakistan. As Bhutto in his final days wrote, “My single most important achievement … is the agreement … concluded in July 1976, [which] will perhaps be my greatest achievement and contribution to the survival of our people and our nation.”38 After India’s nuclear test in 1974, China began transferring technology and uranium to the Kahuta plant, preparing Pakistan’s nuclear capacity. Although information on Pakistan’s nuclear program is highly confidential and restricted, A. Q. Khan in a crestfallen state revealed that China had initially supplied highly enriched uranium along with a weapon design.39 It has even been claimed that China tested for Pakistan its first bomb in 1990 and that this was one of the reasons for Pakistan’s swift response to the Indian nuclear test in 1998.40 After the 1998 tests, Pakistan’s nuclear capacity became a fait accompli, which in turn secured Chinese interest in balancing India’s dominance of South Asia.

Pakistan plays a dual role for China: it contributes in keeping India engaged on its western border and provides access to the Arabian Sea via the Gawader port along with future pipelines, rail, and road networks. This in turn furthers China’s transition to being a global power. For India, a Sino-Pakistan military alliance represents a belligerent potential; as noted by K. Alan Kronstadt, Chinese support for Pakistan is considered part of Beijing’s policy of “encirclement of India.” In the words of former Pakistani ambassador to the United States Hussain Haqqani, “For China, Pakistan is a low-cost secondary deterrent to India, and for Pakistan, China is a high value guarantor of security against India.”41 Indeed, China has demonstrated itself to be a consistent and reliable “guarantor” for Pakistan. Since the 1960s, Beijing has unceasingly strengthened Pakistan’s military capabilities, unlike the arbitrary U.S. military aid. The military dimension of this relation was added after the 1965 Indo-Pakistan War, when China supplied much needed bombers and tanks to Pakistan, including MiG-15s, IL-28 bombers, and T-59 medium-range tanks.42

China and Pakistan have a long history of military ties; more recently, this includes joint-venture projects that have produced the K-8 trainer, FC-1/JF-17 combat aircrafts,43 and Al-Khalid tanks. From 2005 to 2009, China was the largest arms supplier to Pakistan, accounting for 37 percent of Pakistan’s imports, whereas the United States accounted for 35 percent.44 China continues to provide Pakistan with advanced air defense equipment as well as fighter jets, regardless of Indian protests that the Chinese measures affect the strategic defense balance. It is relevant to mention India’s emerging political, economic, and military strength in the region, and the question that concerns us is, Could strong Indian opposition to Chinese policies vis-à-vis Pakistan prevent China’s historic role as Pakistan’s “unfaltering ally”? The answer depends on how Pakistan handles the challenge of Islamist proxies. Nevertheless, for the time being, Beijing seems to be publicly standing by Islamabad. This was evident in May 2011, when during an official state visit to Beijing, the Pakistani prime minister was promised an urgent batch of fifty advanced multirole JF-17 Thunder jets by China, despite strong Indian protests.45 The relevance of this measure is crucial due to the fact that it came at a time when the Pakistan military establishment’s credibility was at its lowest point after the bin Laden discovery by the United States. Chinese encouragement in the form of military provision to Pakistan speaks for Beijing’s unrelenting support for its strategic partner and neighbor.

Historically, the Sino-Pakistan military collaboration was to strengthen Pakistan against India, but after the 1990s and particularly after the U.S. sanctions on Pakistan, China became the leading arms supplier, and the balance of interest tilted more in Pakistan’s favor. Since 2004, the two countries have conducted four joint military exercises called YOUYI, meaning friendship.46 In the YOUYI exercises, special forces along with senior military leadership from both sides have participated. Similarly, the U.S.–India joint military exercises commenced in 2004 were known as YUDH ABHYAS, which translates into “training for war.” The November 2011 U.S. Department of Defense Report to Congress on U.S.–India Security Cooperation47 emphasized that the defense trade relationship would enable transfer of advance technologies to India. Pakistan’s insecurities are rooted in the arms race with India. As pointed out by international relations scholars, state policies that are intended to increase one state’s security inadvertently decrease the security of other states.48 Thus, the prospect of India gaining a military edge with U.S. support automatically decreases Pakistan’s security (heightening existing insecurities) and further deepens the breach of trust between Pakistan and the United States.

PAKISTAN AS A PIVOTAL STATE

Pakistan is a pivotal state for both the United States and China, on the grounds of its capacity to affect regional and systemic stability. Robert Chase, who coined the term “pivotal states,” would identify a pivot on the grounds of its large population and important geographic location. Hence, a collapse of such a state would “spell transboundary mayhem: migration, communal violence, pollution, disease and so on.”49 Linking it back to the traditional security concerns, one would argue that Pakistan’s security is not just a matter of Pakistani concern but also the concern of the major power players of the region, and China appears to be aware of this aspect. The stability of Pakistan is more important to China than it would be for the United States. For example, Chinese security interests in Xinjiang can be directly threatened from South Asia. A stable Pakistan diminishes the possibility of a threat from the subcontinent. Similarly, the United States is not ignorant of Pakistan’s importance and that the stability of Pakistan and the region is intertwined with its security interests.

The historical narrative of Pakistan–China and Pakistan–U.S. relations shows a pattern in which relations are formed in pursuit of (greater) security. At each critical juncture, Pakistan has oscillated between the United States and China for defensive security capabilities as well as armed offensive capacity.50 The events following September 11, 2001, changed the regional dynamics, and once again Pakistan was at the focal point for the United States. For China, this carefully devised Pakistan–U.S. nuptial presented an opportunity to further strengthen Pakistan’s economic and military position (at the expense of the United States) vis-à-vis India. The following section will explore the Pakistani public perception of China, the United States, and India.

PUBLIC PERCEPTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS

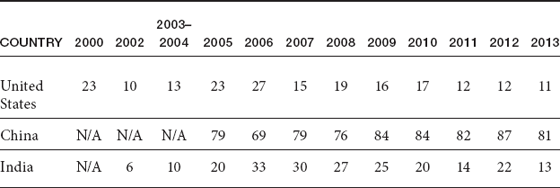

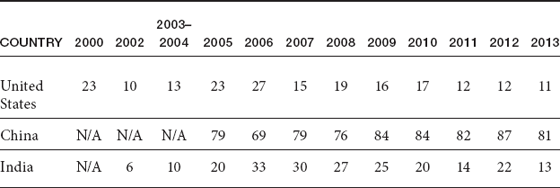

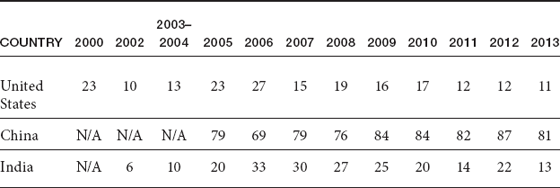

The importance of public perception cannot be ignored when it comes to foreign policy matters. Historically, Pakistan’s importance for the United States has been structured on a need-based arrangement, and that pattern led to deep distrust within the Pakistani public perception of the United States. China, conversely, has fared considerably well. In Pakistan, Beijing has cultivated an image of a time-tested all-weather friend, despite the lack of cultural affinities and common values, whereas Washington’s perception is of a hegemonic partner, as reflected in the public opinion survey conducted by Pew Research Center (table 9.1). The U.S. image is undeviating in its negative perception from 2001 to 2013. An overwhelming 70 percent of Pakistanis perceive the United States as an “enemy,” whereas, a large majority (87 percent in 2012) of Pakistanis consider China as a partner and friend.51 As illustrated in table 9.1, U.S. favorability numbers are even lower than those of India.

TABLE 9.1 FAVORABILITY PERCEPTION FIGURES IN PERCENTAGE (2000–2013)

Given the widespread skepticism and public discontent, the aforementioned numbers are not surprising but a mere reflection of the overall mood in Pakistan with regards to the United States. The more surprising statistics are the U.S. grant figures in comparison to those of China. For fiscal years 2004–2009, the average annual grant assistance to Pakistan by China was $9 million in comparison to $268 million by the United States (table 9.2).52 Regardless of the exponential difference in assistance, China still enjoys a more advantageous position in Pakistan. Since 2004, public opinion of the United States has been significantly affected by its drone strikes in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. China, in contrast, is perceived as a noninterfering and nonthreatening neighbor. Pakistan’s overemphasized focus on China’s mutual respect and noninterference policy (a component of Panchsheel) has also played an important role in the high favorability figures. Comments made in a speech by former prime minister Yusuf Raza Gilani stand as a good example: “One thing that is certain is that … Pakistan and China focus on and protect each other’s core interests. Pakistan always respects the sovereignty and core interest of China, and China does the same.”53

Recent years have seen a further decline in the U.S. perception, particularly after the incremental increase of drone strikes in 2008; the May 2, 2011, raid to kill bin Laden; and the Salala incident of November 2011. Furthermore, the U.S. war against Al Qaeda and its affiliates in Afghanistan is adjudged by the Pakistani public as a societal security54 concern that could be translated into a crusade against Islam and the Muslim world. However surprisingly, China is not viewed as a threat to Islam or the Muslim world, despite its iron fist policies in the Muslim-majority province of Xinjiang. China’s use of force within its territory is perceived as legitimate and permissible.

TABLE 9.2 INTERNATIONAL AID TO PAKISTAN (2001—2010)

| DONORS |

COMMITTED ($ MILLIONS) |

DISBURSED ($ MILLIONS) |

| United States |

4,238 |

3,283 |

| Japan |

1,711 |

982 |

| China |

3,290 |

857 |

| United Kingdom |

1,676 |

1,177 |

| Germany |

748 |

721 |

| United Arab Emirates |

454 |

103 |

| Saudi Arabia |

824 |

319 |

FOR CHINA, A CONTEST FOR SUPREMACY?

The Sino-Indian rivalry that was initiated in 1958–1959 is at present not more than a border dispute.55 However, China is a rising global power, which brings us to our second question: Is the alliance with Pakistan a result of Beijing’s pragmatic expression of containing India to foster regional supremacy? The dominant actors in this puzzle are Pakistan, China, the United States, and India, and one can argue that in the twenty-first century, South Asia not only is the epicenter of the traditional Indo-Pakistan rivalry but also is crucial for U.S.–China relations. China’s perception of its security is an important factor to be considered. The notion of security in this context is twofold; the traditional military–political understanding of security; and economic security, which Barry Buzan refers to as concerns in regard to access to the resources that are necessary to sustain state power.56 Hence for China, Pakistan delivers on two fronts, as a counterweight against India and as a gateway for influencing and reaching out to other Islamic countries—the Middle East in particular as a major resource area. Despite its communist past and a glorious secular history along with a religious policy aimed at curving clergy power, China has maintained its alliance with Pakistan.

China’s primary security objective with Pakistan remains the containment of India, and more recently the aim has also been to prevent sanctuaries for Uyghur separatists and to curtail Islamic extremists. Uyghur separatist groups have emerged because of Chinese colonization of Xinjiang. The Chinese Communist Party has been vigilant in squashing groups that have engaged in separatism.57 The East Turkestan Islamic Movement58 has links outside China, which forces China to be dependent on other countries to dismantle such a group. That Uyghur separatists receive sanctuary and training in Pakistan has been a source of tension between the two states. Pakistan has responded by clamping down on Uyghur training camps and has extradited Uyghurs to China. At the same time, Pakistani authorities have taken strict measures with regards to Chinese citizens. The Red Mosque operation59 stands as an exemplar for the measures taken by the Pakistani establishment for the appeasement of Beijing. Pakistan has fully backed China in its handling of the 2009 Uyghur ethnic riots in Xinjiang, which left 200 people dead and 1,600 injured.60 However, continued Uyghur attacks in China have left Beijing dissatisfied by Pakistani efforts to combat terrorism.61 Considering the new security threats to the region, Pakistan attempts to deliver to the utmost to protect China interests and support Beijing’s decisions on the international stage.

A TRADE CORRIDOR FOR GREATER AFGHAN–PAKISTANI INTEGRATION WITH CHINA

When Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping succeeded Mao, he introduced a pragmatic foreign policy focused on economic ends and means. Deng Xiaoping’s foreign policy enabled China’s rise through a profit-centric approach and avoided structural pitfalls that a major power faces. Beijing revisited its policies and laid down a new domestic and international modus operandi. According to the new approach, Beijing’s foreign policy was grounded in the economic interest of China, with a diminished appetite for unilateralism, and heavy emphasis was placed on regional and global multilateralism with the aim of improving ties with key global trade partners in compliance with its Five Principles approach. This is what many analysts would call the marriage of Panchsheel with the Beijing Consensus—in other words, a Chinese soft power strategy.

China’s relations with Pakistan have been formed on economic aid, military transactions, and commerce in goods and commodities. A recent example of Chinese commitment to Pakistan’s economic development is the China-Pak Economic Corridor (CPEC). According to this deal, the Chinese government and finance companies will invest $45.6 billion over the course of 6 years for energy and infrastructure projects in Pakistan.62 Likewise in 2008, the two countries signed a comprehensive trade agreement granting unprecedented market access to each other. The bilateral trade figures have exponentially increased over the years, estimated at $7 billion per annum and expected to reach $15 billion by 2015. Since Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms and more specifically the rise of economic globalization, Beijing’s vision for Pakistan is more focused on economic robustness, along with its military vigor. This is perhaps more evident in the infrastructure project, including major highways, gold and copper mines, and power plants, with an estimated ten thousand Chinese workers employed in Pakistan. In 2005, Pakistan and China signed a precedent-setting Treaty of Friendship and Co-operation, pledging that “neither party will join any alliance or bloc which infringes upon the sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of either China or Pakistan.” A careful examination of the terminology used in this treaty reminds us of Cold War parlance, where the contractual parties were committing to supporting each other against aggression.

Beijing’s policy of handling Muslim countries translates into China’s capacity to export its soft power to gain access to resources. With the withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan, Beijing’s interest in the Afghanistan–Pakistan region has become strategically important, due to its increased needs for oil, gas, and minerals. China’s interest in Afghanistan’s untapped reserves is geographically linked with Pakistan, because of the transportation routes. Although the Wakhan corridor connects Afghanistan to China, because of the lack of infrastructure, the Pakistan option is deemed the only conduit to act as a trade and energy corridor that can help China gain access to resources and overtake India’s interest in the region. China’s investment in the Aynak copper mine is a good case in point.63

For the past few decades, China has been constructing a series of ports around the Indian Ocean. The Gwadar port in Baluchistan is another important piece in Beijing’s economic expansion and transition to being a global power. The Gwadar port is aimed at securing an alternative passage in case of Indian embargo.64 Gwadar’s strategic location provides China with access to the Indian Ocean, where it can station a naval presence capable of providing security. Gwadar also provides China with the capacity to monitor Indian naval activities. And most important, the port provides future commercial interest, especially in the field of energy. In accordance with CPEC, the Gwadar port will be linked to Northwest China.

More than 100 years ago, a French Canadian engineer proposed to use snow shoes in Gilgit to secure a passage to China.65 His proposition was turned down by the British resident in Kashmir, saying it was impracticable and useless because trade and threats were absent. Today the same route is being financed by the Chinese government as an economic corridor, which could be used to import oil, gas, minerals, and goods. The development of the Gwadar port was considered by many as the beginning of a long-term planned corridor that would make Chinese energy imports safer by avoiding the Malacca Strait—which could be blocked by the United States and its allies.66 This also dampens India’s investment in its naval strength and renders it unable to block or intercept the Chinese ships navigating in the Indian Ocean.

CONCLUSION

The trajectory of the Sino-Pakistan relations has remained on course, unwavering and determined since its formative days in the 1950s. The watershed moment for this alliance was the Sino-Indian War of 1962, consequently positioning China on its “all-weather friendship” path to Pakistan. Since then, this relationship, along with the greater South Asian region, has seen many changes, but the strength of this alliance has remained consistent, thus making the Sino-Pakistan alliance unique, even though the two states have never signed any formal alliance or defense pact. In this chapter, we have emphasized the security aspect of this relationship over the course of sixty-plus years. At the turn of the present decade, this relationship was once again confronted with important regional issues: for example, the scaling down of U.S. military aid; the upsurge in militant nonstate actors; and the attacks in Kashgar (Xinjiang Province) coordinated by militants trained in Pakistan. Thus, the options and alternatives are there for both China and Pakistan.

China has increasingly invested in Pakistan, and a retreat of U.S. involvement in the region pushes China to engage more intensively in Pakistan for multiple reasons. First, China acutely needs oil and commodities, which have traditionally come from the Middle East via the Indian Ocean, to arrive through alternative routes, thus deeming China more control in relation to India. Therefore, insecurity in Pakistan and the region would surely postpone the layout of infrastructure (such as the Sino-Pakistan corridor) required to transport the much needed resources. Second, insecurity also creates a challenge for economic development in Afghanistan and Pakistan, particularly when China has invested billions of dollars in both countries. Third, by engaging in Pakistan, China enhances its power against India and the United States. Finally, instability in Pakistan would mean trouble along the border in Xinjiang. Considering this rationale and calculating the costs and benefits, China does need Pakistan as much as Pakistan needs China. Nevertheless, this situation can change if the circumstances around the alliance are transformed—primarily if the attacks in Xinjiang persist by militants trained in Pakistan. Political instability and Pakistan’s failure to crack down on militant training camps from its tribal belt could lead to a radical shift in its relations with China.

The future course of the Pakistan–China alliance is contingent on what China’s national interest and strategic goals are in the region. For Pakistan, this decade has been one of unforeseeable events. The question is, Could this be the juncture in history where the paths of these “time-tested partners” diverge? The key to this challenge is subject to the course of action adopted by Pakistan. This alliance could be seriously harmed if Uyghur militants continue to launch attacks in Xinjiang. Another prospect that can affect this alliance is Pakistan–India rapprochement. Over the years, we have seen changes in relations between China and India, China and the United States, and Pakistan and the United States relations, but the Pakistan–India rivalry has remained consistent. The probability of Indo-Pakistani rivalry termination is weak, but it is impossible to ignore the prospect of it in the future. The intriguing question would be, Where and how would the Sino-Pakistan alliance position itself without “the India nexus”? Would the tour de force of this alliance wane in that situation, or could it give rise to a much stronger regional alliance? To give an idealistic perspective, one would argue that a nonantagonistic atmosphere in South Asia could lead to regional alliance, between China, Pakistan, and India—creating a very different situation than the current realpolitik environment.

Alliances in the international arena are configured and structured on the interests and motives of the states involved. Although the interests and motives may somewhat vary, the goals and strategies are invariably structured on a cost–benefit analysis, with the maximum possibility of favorable outcomes in their desired goals and objectives. The Sino-Pakistan alliance was structured on a common goal, the containment or encirclement of India, but the interests and motives for both were different. The motivation for Pakistan is rooted in its insecurities vis-à-vis India, and China seeks to maintain its strategic position of being the dominant economic and military power in the region. The India threat factor plays the role of an explanatory variable in this relationship. We would like to conclude by quoting a strategy postulated by Deng Xiaoping, which has Machiavellian undertones and sheds light on Beijing’s grand design:

Observe calmly;

Secure our [Chinese] position;

Cope with affairs calmly;

Hide our [Chinese] capacities and bide our time;

Be good at maintaining a low profile;

And never claim leadership;

Make some contribution.67

This is realpolitik par excellence, and it resembles the Chinese game wei qi (a game of encirclement). Pakistan in this equation is one of the strategic pieces for China in its game to contain or encircle India and gain regional or ultimately global supremacy. The turn of this decade will prove the mettle of this alliance and Pakistan’s strategic importance for China.

Cordial feelings are mutual on both sides of the border and have remained strong since its inception at the Bandung Conference in 1955. But whereas in the beginning security concerns were on the forefront for both China and Pakistan, China’s national interests and objectives diverged after the 1979 economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping. Pakistan to this day continues to be perturbed by its perpetually constructed security dilemma, whereas China has adopted a pragmatic course focused on economic development and prosperity. However, despite the divergence in national objectives, this relationship has thus far maintained the initial essence of mutual trust and cooperation. Recent affirmations from Beijing have further validated this sentiment, particularly at a time when Pakistan’s credibility and reputation were at its lowest ebb, following the May 2, 2011, raid by the United States and killing of Osama bin Laden in the vicinity of Pakistan’s elite military academy. Beijing’s sympathetic reaction to this sensitive affair was a testament to its sixty years of unwavering support for Pakistan.

NOTES