BETWEEN HIS MEETING with Churchill in September 1944 and his death in April 1945, Roosevelt underwent no change in his attitude toward the bomb. But in the laboratories of the Manhattan Project, particularly the Met Lab, scientists became increasingly concerned during late 1944 and early 1945 about the implications of their work. To their earlier anxiety about military control was now added the dawning fear that they might succeed in making a weapon of mass destruction. This was especially true of Leo Szilard. The big question in his mind shifted from “Can an atomic bomb be made?” to “What will happen once it is?”

This question increasingly consumed Szilard’s thinking as his workload decreased. With a chain-reacting pile achieved and plutonium production underway at Hanford, the Met Lab had essentially completed its task. The focus of effort had shifted to Los Alamos. This gave Szilard more time to reflect, and the more he reflected the less enamored he became of the bomb. Sitting in his room—the space practically bare except for an old traveling bag which served as a closet—at the Quadrangle Club of the University of Chicago or strolling the green expanse of the Midway south of the university on evenings and weekends, he turned his far-reaching mind to a host of questions: Should Russia be told about the bomb? If Germany was defeated before the bomb was ready—as seemed increasingly likely—should it be used against Japan? Could international control be achieved, and if so, what form should it take?

Szilard first addressed these questions in January 1944, when he sent Vannevar Bush a memorandum emphasizing for the first time not the urgency of beating Nazi Germany to the bomb but what it would mean to the world once the bomb was made. “If peace is organized before it has penetrated the public’s mind that the potentialities of atomic bombs are a reality,” he wrote, “it will be impossible to have a peace that is based on reality.” And yet he acknowledged a stark dilemma: “It will hardly be possible to get political action along that line unless high efficiency atomic bombs have actually been used in this war and the fact of their destructive power has deeply penetrated the mind of the public.” 1

Other Met Lab scientists also began contemplating the bomb’s implications. The most sophisticated and far-reaching study was conducted by a group that included Fermi. The report, formally titled “Prospectus on Nucleonics,” and known as the Jeffries Report after its chairman, physicist Zay Jeffries, called for a general statement to the American public revealing the existence of the Manhattan Project, the destructive potential of the bomb, and the fact that it would inevitably affect relations between nations in the future. The report owed its inspiration to Compton, who had asked Met Lab scientists for their ideas the year before. From then on, with Compton’s encouragement, the group devoted serious thought to postwar problems. 2

The Jeffries Report, submitted to Compton in November 1944, reflected a broad spectrum of scientific opinion. The quality and quantity of viewpoints—the report was sixty-five typewritten pages in length—showed that the implications of the new weapon had been discussed in considerable detail. Its assessment was presented in the form of a warning, coupled with a set of recommendations. A world armed with atomic bombs was analogous to two people armed with machine guns locked in a room, the report said. Since the person who shoots first kills his rival, it is likely that one of them will do so to remove the fear of being attacked. The prospect of this kind of preventive warfare would become a grim reality—as America’s war against the specter of a nuclear-armed Iraq under Saddam Hussein half a century later attested—unless mutual understanding were achieved and the production of atomic bombs were either prevented entirely or limited to a carefully controlled pool for checking any potential disturbance of the peace. The report also noted that “it would be surprising if the Russians are not also diligently engaged in such work.” A peace based on uncontrolled and perhaps clandestine development of nuclear weapons was little more than an armistice and was bound to end, sooner or later, in catastrophe. A central authority for the control of atomic energy was necessary if the world was to avoid disaster. Compton submitted the Jeffries Report to Groves, who chose not to pass it along to policy makers. 3

Bohr decided to make one last approach to policy makers himself. In early April 1945, he prepared a detailed memorandum on the bomb’s postwar implications for Roosevelt. The memo included many farsighted proposals later adopted by the U.S. government for the international control of atomic energy: technical inspection, an international inspection agency, and a distinction between “safe” and “dangerous” activities in the realm of nuclear research. Bohr believed humanity’s survival in the long run required far-sighted statesmanship in the short run. 4 Bohr asked British Ambassador Lord Halifax and Felix Frankfurter to get it to the president. Halifax and Frankfurter discussed Bohr’s request on a stroll through Rock Creek Park on the afternoon of April twelfth. It was a beautiful spring day in Washington, the sun bright and warm and the leaves and grass emerald green. Suddenly church bells began to toll until the air filled with their sound. Halifax and Frankfurter saw people hurrying to speak to others. Roosevelt had died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Warm Springs, Georgia. With that, Szilard’s initiative was halted.

Several weeks before, Szilard had also prepared a memorandum for FDR. Remarkably perceptive, the memo addressed a number of central problems: the escalation of nuclear weapons technology from atomic to thermonuclear bombs, the vulnerability of an urbanized nation like the United States to nuclear attack, and challenges involving control of raw materials and on-site inspections. Szilard predicted that America faced a fundamental choice: negotiate an accord with the Soviets or compete with them in an atomic arms race after the war. 5 The great danger of such a race was “the possibility of the outbreak of a preventive war. Such a war might be the outcome of the fear that the other country might strike first, and no amount of good will on the part of both nations might be sufficient to prevent the outbreak of a war if such an explosive situation were allowed to develop.” Only international control could avert this danger. The U.S. government was about to arrive at decisions, he warned, that would control the course of events after the war. Those decisions ought to be based on careful estimates of future possibilities, not simply “on the present evidence relating to atomic bombs.” 6

Szilard had discussed his memo with Lawrence. They met at the Chicago rail station, Lawrence reading and commenting on the memo as he waited to change trains. 7 Lawrence encouraged Szilard to forward the memo to the president through First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who agreed to see him. With a White House appointment thus set, Szilard went to Compton’s office armed with his memorandum. He was nervous as Compton slowly read the memo, expecting to be scolded for again going outside official channels. To Szilard’s astonishment, Compton cheered him on, saying, “I hope that you will get the President to read this.” “Elated by finding no resistance where I expected resistance,” Szilard recalled, “I went back to my office. I hadn’t been in my office for five minutes when there was a knock on the door and Compton’s assistant came in, telling me that he had just: heard over the radio that President Roosevelt had died.” 8

FDR’s death shocked Szilard and the entire nation. Vice President Harry S Truman now assumed the burdens of commander in chief in a war that—especially against Japan—was growing fierce and pitiless. Between February and March 1945, three Marine divisions had slugged their way across Iwo Jima, a western Pacific island of volcanic ash, rock, and stinking sulfur fumes. The island’s 21,000 Japanese defenders meant to make its conquest so costly that Americans would recoil from invading their homeland. The battle for Iwo Jima became a nightmare of relentless attacks and swarms of flies feeding on dead flesh. One Marine despaired, “They send you to a place and you get shot to hell and maybe they pull you back. But then they send you right up again and then you get murdered. God, you stay there until you get killed or until you can’t stand it any more.” 9 Five weeks of fighting on Iwo Jima cost the Marine Corps nearly 7,000 dead and 22,000 wounded out of 60,000 committed—the highest casualty rate in Marine Corps history. Its three divisions had to be rebuilt with teenage replacements. The Japanese on Iwo Jima perished almost to a man, having inflicted more casualties in killed and wounded than they suffered for the first time in the war.

Things would be even worse during the Battle of Okinawa between April and June, when Americans encountered the most savage Japanese resistance of the war. Kamikaze suicide bombers slammed into navy ships offshore, turning destroyers into flaming junk heaps manned by bloody remnants of their crews. The kamikaze attacks were alien and terrifying; they confirmed for Americans the extent of Japanese doggedness and desperation even as the United States ground down Japan’s war machine. The navy suffered 10,000 casualties, half of them killed. Fighting on the island was a slaughter. Before it was over, more than 100,000 Japanese soldiers and another 100,000 native Okinawans had perished. The U.S. army lost 40,000 men, a fourth of them killed in action. Thousands of Americans and Japanese were being killed on the beaches and in the jungles of the Pacific every week.

In the skies over Japan, giant American B-29 bombers were running massive raids against cities, wiping them off the map, one after another, like the wrath of God. The results were devastating and appalling. Twenty-two million Japanese—30 percent of the country’s entire population—were rendered homeless by fire raids that razed 178 square miles of densely populated urban areas. The fire raids inflicted 2,200,000 civilian casualties, including approximately 900,000 killed. The number of Japan’s civilians killed exceeded its combat casualties of approximately 780,000.

Nothing illustrated the escalating violence of the Pacific War—and the declining restraint of its combatants—more vividly than the B-29 fire raid against Tokyo in March 1945. At the start of the war, Roosevelt had entreated all combatants to refrain from bombing civilians and recalled with pride that “the United States consistently has taken the lead in urging that this inhuman practice be prohibited.” 10 Now America launched a thousand-plane bombing raid deliberately designed to burn Japan’s capital city—and its civilian inhabitants who lived there, crowded in wood-and-paper houses—to ashes.

Shortly after midnight on March tenth, residents of Tokyo peered out of their air-raid shelters and saw an eerie sight above the city. Reflecting spectral colors from searchlights, hundreds of B-29s descended slowly, their bomb bays filled with six-pound incendiary bomblets that spewed burning gelatinized gasoline that stuck to its targets and was inextinguishable. The bomblets were intended to set the city afire and they did, splashing a flaming dew across wooden roofs and spreading fire everywhere. Wind whipped scattered fires into furnaces of flame, a thermal hurricane that jumped streets, firebreaks, and canals at dizzying speed. It acted like an enormous bellows, superheating the air to eighteen hundred degrees Fahrenheit. B-29s in later attack waves spotted the growing cauldron while still far out at sea. As they flew over the boiling city, they bounced violently as thermal updrafts from the vast and intense conflagration below knocked them about like paper airplanes. At six thousand feet the heat was so intense that crews had to don oxygen masks to breathe. Even at this altitude, American airmen could smell the soot and the burning flesh and vomited. A bombadier who flew above Tokyo that night remembered it as “the most terrifying thing I’ve ever known.” 11

Fire was not the only danger to Japanese civilians below. Superheated vapors rushing ahead of the flames killed or knocked victims unconscious even before the fires reached them. Death came in many agonizing ways: oxygen deficiency, carbon-monoxide poisoning, radiant heat, direct flames, and crushing stampedes. Canals and ponds through the city offered no relief; luckless bathers were boiled alive or drowned as frantic crowds pushed them down in the superheated water. When the raid was over, sixteen square miles had been burned out, one million people were homeless, and upward of 100,000 had perished. Only a few sounds could be heard across the smoking moonscape of vast desolation the next morning: the groaning of victims with burned lungs, the desperate calls for missing loved ones.

In an eerie—almost unbelievable—irony, on the same night as the massive B-29 fire raid on Tokyo, a high-altitude Japanese balloon dangling two small incendiary bombs, after drifting across the Pacific Ocean on the jet stream, flukishly fell on the Hanford nuclear reservation in remote south central Washington state. Ropes dangling from the balloon became entangled in the electrical line feeding power to the building housing a nuclear pile. The pile had to be shut down at once, though the power was restored a few hours later. It was this plant that was producing the plutonium that would devastate Nagasaki.

The Manhattan Project, like the war itself, was nearing its climax in the spring of 1945. The project had proceeded with Roosevelt’s steadfast support, and although the responsibility was now Truman’s, the new president was constrained by the choices of his prestigious predecessor. FDR had refused to broach the subject of international control with Stalin and had indicated his intention to use the bomb to help win the war. Such policies molded the outlook of his successor, who was uninformed, unprepared, and unsure of himself. Truman had met with FDR only twice between his inauguration as vice president on January twentieth and Roosevelt’s death on April twelfth—both times on trivial matters. He was unaware of the agreement FDR and Churchill had reached at Hyde Park. Nor did Truman’s experience as chairman of the Senate Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program prepare him to deal with the Manhattan Project, because the secret had been withheld from him. In a subtle but important respect, the new president was at the mercy of decisions already made and events rapidly unfolding. 12

To compensate for his inexperience, his ignorance, and his anxiety to do well the job suddenly thrust upon him, Truman relied heavily on his inherited advisers, particularly Secretary of War Henry Stimson and James F. Byrnes, a close confidante of Truman who had been his mentor in the Senate, a Supreme Court justice, and war mobilization director under Roosevelt. The race for the atomic bomb was consuming an increasing amount of Stimson’s time by April 1945, even as the war in the Pacific grew fierce and the weight of his seventy-seven years left him in need of rest every afternoon; and as he became more deeply involved with atomic matters, he began to ponder and reflect.

Stimson inclined toward the bomb’s wartime use and to hold the secret of the bomb as a reward to induce Stalin’s cooperation. Although he knew the Soviets were spying on the project, he did not believe they had acquired any crucial information; and while he was troubled about the possible effect of continuing to keep them officially uninformed about the enterprise, he believed that it was essential, as he wrote in his diary at the end of 1944, “not to take them into our confidence until we were sure to get a real quid pro quo from our frankness.” Stimson had no illusions about the possibility of keeping such a secret permanently, but he did not think “it was yet time to share it with Russia.” 13 Stimson did not intend to threaten the Soviet Union with the new weapon, but he expected that once its power was demonstrated, the Soviets would be more cooperative about postwar issues. 14

At the end of Truman’s first Cabinet meeting, hastily convened after he was sworn in on April twelfth, Stimson stayed behind. He would spell out the details later, he said, but before departing he wanted to inform the new president of “a new explosive of almost unbelievable destructive power.” 15 Two weeks later, on April twenty-fifth, Stimson and Groves briefed Truman on the details of the Manhattan Project. They told him scientists would soon complete “the most terrible weapon ever known in human history,” one of which “could destroy a whole city.” They were confident the weapon would bring the bloody war to a rapid conclusion, thereby justifying the years of effort, the vast expenditures, and the judgment of officials responsible for the project. A serious and thoughtful man, Stimson also reflected on the bomb’s larger meaning in an accompanying memo. The world, “in its present state of moral advancement compared with its technical development[,] would be eventually at the mercy of such a weapon,” he warned the new president, adding: “Modern civilization might be completely destroyed.” Stimson asserted that “a certain moral responsibility” flowed from U.S. leadership in this field that the nation could not shirk “without very serious responsibility for any disaster to civilization which it would further.” 16

To address this serious challenge, Stimson proposed the establishment of a committee to consider the proper use of the bomb once it was finished and the postwar problems related to its development. Truman agreed, and the Interim Committee, as the advisory group came to be known, was created on May 1, 1945. * Stimson sought to keep the Interim Committee small enough to conduct meaningful discussions but varied enough in its membership to represent diverse viewpoints. More than a year after Bohr had urged policy makers to begin looking ahead, machinery was finally established to consider the most momentous and dangerous development of the war. Stimson’s charge to the committee asked for advice about how, but not whether, the bomb should be used against Japan. That the bomb would be used once it was ready seems to have been a foregone conclusion.

A Scientific Advisory Panel to the Interim Committee was also created, composed of Compton, Lawrence, Oppenheimer, and Fermi, the first three chosen because they were directors of the Chicago, Berkeley, and Los Alamos laboratories; Fermi, because of his unrivaled knowledge of nuclear physics. The Scientific Advisory Panel reflected policy makers’ desire for expert advice, but it was also an attempt to preempt discontent among scientists if decisions were made about how to use the bomb without consulting those who had made it.

Somewhat like Szilard, Oppenheimer, after much soul-searching, had concluded that the bomb he and others at Los Alamos were making had to be used because that was the only way to awaken the world to the necessity of abolishing war altogether. No demonstration—even if it was possible under wartime conditions, which he doubted—could take the place of actual combat use, with its horrible and sobering results. Moreover, Oppenheimer thought it would be very difficult if not impossible to get political action on international control unless the bomb’s immensely destructive power deeply penetrated the popular mind. “My own view,” he asserted later, “is that the development of atomic weapons can make the problem more hopeful because it intensifies the urgency of our hopes—in frank words, because we are scared.” 17 He hoped that a military demonstration of the bomb would compel a general recognition that pre-atomic age calculations had to give way to new realities.

Oppenheimer privately worried to Szilard, however, that Washington officials had inadequately pondered these sobering new realities. Oppenheimer’s worry intensified Szilard’s own fears. Referring to the prospects of a “superbomb” infinitely more powerful even than an atomic bomb, he asked Oppenheimer “what men like Stimson and Wallace would think if they were fully advised of the turn which the technical development can be expected to take within a few years.”

Using the bomb did not necessarily mean using it on a civilian target. Szilard knew, however, that he faced an uphill battle persuading Oppenheimer to oppose dropping the bomb on a Japanese city. “I expect that you who have been so strenuously working at [Los Alamos] on getting these devices ready will naturally lean towards wanting that they should be used,” he told him. 18 In this, Szilard was perceptive. Work on the atomic bomb had begun in the spring of 1939 out of fear that the Nazis were building one of their own, but the surrender of Germany in the spring of 1945 brought the resignation of only two scientists at Los Alamos. If others thought of leaving—or debating use of the bomb—a meeting that Oppenheimer called a few days after Germany’s surrender stopped them in their tracks. Oppenheimer told them they should finish their task and leave the politics to policy makers in Washington. “He was very uncompromising and very sharp,” remembered one who attended the meeting. “He indicated that he would not tolerate that kind of discussion and he implicitly invited those who felt that way to get out.” 19 No one else left.

The project had long ago assumed a momentum and a life of its own. It had become a monumental scientific and engineering endeavor, involving prodigious effort and expense and labor. It was now a hurtling train moving forward—like the Pacific War itself—with awesome, almost unstoppable force. Most scientists were too involved in their work and too committed to achieving their goal to stop and reflect. “Most people just didn’t think too much about what would happen,” recalled a physicist on the Hill that spring—“No, that was somebody else’s problem.” 20 What had begun as a fearful race with Nazi Germany had become an end in itself. “I don’t think there was any time where we worked harder at the speed-up than in the period after the German surrender and the actual combat use of the bomb,” Oppenheimer recalled after the war. 21

Ethical and moral concerns had been eclipsed by their emotional and psychological investment and the intensity they brought to problem solving. The physics existed; it simply waited to be revealed. They believed the bomb was going to be built by someone, and they wanted it to be them. The intensity of collaborative work with extraordinarily gifted people also had enormous appeal. That camaraderie, shared in the exploration of an arcane and forbidden realm, provided a rare sense of intimacy, a sense of transcendence that combined strong creative satisfaction with feelings of individual power—how many people could resist that? And like most Americans in 1945, they found it hard to empathize with the fate of a people whose soldiers had committed atrocities against Americans and who were so physically and culturally different. There was not a single Asian American among the Manhattan Project staff, and it was easy for the scientists to think of the Japanese as “the other.” There was some private debate about the morality of dropping the bomb on a city, but most felt it was no worse than the fire raids then devastating Japan and that it was justified if it ended the war. In addition, most scientists believed—or wanted to believe—that once this horrible weapon was used, there could never be another war. This made the idea of using the bomb to kill large numbers of civilians emotionally easier for those who were building it.

Szilard was determined to do all he could to prevent this. On May twenty-eighth, he and two fellow scientists that he persuaded to come along traveled to South Carolina to see James Byrnes, who was now secretary of state designate. Szilard was directed there by the president’s appointments secretary after an unsuccessful attempt to speak personally with Truman. Szilard and his two companions traveled by train to Spartanburg, a small town nestled in the piney foothills of western South Carolina, and walked from the red brick railroad station to Byrnes’s house nearby.

The meeting between Szilard and Byrnes echoed the one between Bohr and Churchill the year before. It was a tense, unsatisfactory exchange between different men with different assumptions and perspectives. A purse-lipped man with a wiry frame, beaklike nose, and sharp eyes that peered at others with steely geniality, Byrnes was a savvy politician thoroughly schooled in the practicalities of power. He had grown up in the 1880s, when the southern up-country still had a tough frontier ethos. Byrnes was brought up to believe that when you fought, you fought with everything you had. He had little patience, or sympathy, for the moral arguments of a physicist with a foreign accent, though he concealed his lack of interest beneath the mask of amiability that politicians always have on call. 22

Szilard gave the secretary of state designate a copy of the memo he had prepared for Roosevelt shortly before the president’s death. Even before Byrnes got halfway through the memo, Szilard started to warn him against dropping the bomb on Japan as a way to impress Russia. Byrnes replied that demonstrating the bomb would make Russia more manageable in Europe. “You come from Hungary,” he said—“you would not want Russia to stay in Hungary indefinitely.” 23 But Szilard did not share Byrnes’s assumption that the bomb would make Russia more manageable and he countered that the “interests of peace might best be served and an arms race avoided by not using the bomb against Japan, keeping it secret, and letting the Russians think that our work on it had not succeeded.” 24 Byrnes was appalled and incredulous. The nation had spent more than $2 billion on the bomb’s development, he said—Congress would demand to see results. As he had told FDR shortly before the president’s death, the administration might well avoid embarrassment during the war if the bomb remained in doubt, but afterward, “If the project proves a failure, it will then be subjected to relentless investigation and criticism.” 25

Szilard left Spartanburg acutely frustrated. How could he communicate with politicians insensitive to the bomb’s revolutionary power and implications? “I thought to myself,” he later wrote, “how much better off the world might be had I been born in America and become influential in American politics, and had Byrnes been born in Hungary and studied physics. In all probability there would have been no atomic bomb, and no danger of an arms race between America and Russia.” Szilard was convinced that Byrnes, and by implication President Truman, were inclined toward a shortsighted policy that would make a postwar atomic arms race inevitable. 26

On the way back to Chicago, Szilard stopped in Washington to see Oppenheimer, who was in the capital for an upcoming meeting of the Interim Committee. Szilard told Oppenheimer about his unsuccessful meeting with Byrnes and stressed how important it was to persuade policy makers to inform the Russians about the bomb before it was used against Japan. “Don’t you think if we tell the Russians what we intend to do and then use the bomb in Japan, the Russians will understand it?” Oppenheimer asked. “They’ll understand it only too well,” Szilard answered. 27

Three days after the Spartanburg meeting, on May 31, 1945, the Interim Committee and its Scientific Advisory Panel met in Stimson’s Pentagon office to work out a recommendation for President Truman on the use of the atomic bomb. Nazi Germany had surrendered only three weeks earlier. Fighting for Okinawa had entered its bloodiest phase. Japan’s militarists seemed unwavering in their determination to fight to the finish. It would be another seven weeks before the first atomic bomb would be tested.

In preparation for the meeting, Arthur Compton drafted a memorandum for the other participants. In it, he stressed that the use of the atomic bomb on Japan was “more a political than a military question because it introduces the question of mass slaughter, really for the first time in history. Essentially, the question of the use to be made of the new weapon carries much more serious implications than the introduction of poison gas.” He called the question of the bomb’s use “first in point of urgency.” “This whole question,” Compton wrote skeptically, “may well have received the broad study it demands. I merely mention it as one of the urgent problems that have bothered our men because of its many ramifications and humanitarian implications.” 28

Those gathered in Stimson’s office that morning shared two unstated assumptions: that the atomic bomb would have a decisive impact on Japan’s leaders; and that the American public, if they knew of its existence, would demand that it be used to save the lives of American servicemen. The expenditure of billions of dollars; mounting U.S. casualties in the face of tenacious Japanese resistance; the bomb’s expected salutary effect on postwar relations with the Soviet Union—all these factors bolstered a predisposition toward use. “Throughout the morning’s discussion,” Compton later wrote, “it seemed to be a foregone conclusion that the bomb would be used. It was regarding only the details of strategy and tactics that differing views were expressed.” 29

NINE PHYSICISTS

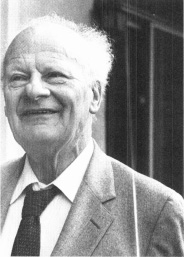

Leo Szilard (1898–1964), Hungarian-born American physicist who helped initiate the Manhattan Project in 1939 yet vigorously opposed dropping the atomic bomb on Japan’s cities in the summer of 1945. After the war, he became an ardent promoter of international control of nuclear weapons. (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Enrico Fermi (1901–1954), Italian-born American physicist who conducted early neutron experiments and directed the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in December 1942. He reluctantly supported use of the atomic bomb against Japan and development of the superbomb after the war. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Segrè Collection)

I. I. Rabi (1898–1988), American physicist who consulted at Los Alamos during the war, where he acted as an adviser and consultant to his close friend, Robert Oppenheimer. He served in many government advisory posts after the war and vigorously defended Oppenheimer against charges of being a security risk. (© AP/Wide World Photos)

Niels Bohr (1885–1962), Danish theoretical physicist whose concern about the terrifying prospects for humanity posed by atomic weapons led him to lobby British prime minister Winston Churchill and American president Franklin Roosevelt during the war in favor of international control. He was unsuccessful. (National Archives and Records Administration, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Edward Teller (1908–2003), Hungarian-born American physicist who helped convince the U.S. government to build an atomic bomb and later pushed for development of the superbomb. A staunch anticommunist, he sought American nuclear superiority over the Soviet Union during the Cold War. (© CORBIS)

Ernest Lawrence (1901–1958), American experimental physicist who invented the first high-energy particle accelerator, the cyclotron, and founded the Berkeley and Livermore National Laboratories. An early advocate of government support for atomic research in 1941, he opposed development of the superbomb immediately after the war but later changed his mind. (Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Arthur Compton (1892–1962), American physicist who chaired the governmental advisory committee in 1941 that assessed fission’s military potential. He later directed the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, where scientists researched plutonium and the nuclear chain reaction. He abandoned weapons work after the war. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, W. F Meggers Gallery of Nobel Laureates)

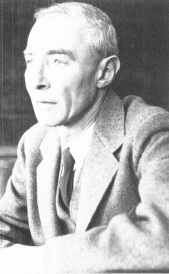

Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967), American theoretical physicist who led development of the atomic bomb as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1943–1945. After the war, he sought to resolve the political and moral problems arising from nuclear weapons but fell victim to an anticommunist witch-hunt. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Hans Bethe (1906–2005), German-born American physicist who led the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos during the war and reluctantly participated in development of the superbomb after the war. He later became a leading critic of the nuclear arms race and the policy of nuclear superiority championed by Edward Teller. (© CORBIS)

THE NETWORK

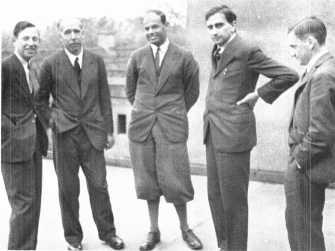

Niels Bohr (second from left) stood at the center of a close-knit network of European and American physicists in the 1920s and 1930s. Here he meets with younger colleagues, including Edward Teller (second from right) and Otto Frisch (far right). (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Wheeler Collection)

Robert Oppenheimer (wearing hat) and I. I. Rabi (holding sheet), two American postgraduates in Zurich, summer 1930, with Wolfgang Pauli (far right). In Europe, Oppenheimer and Rabi learned the latest physics, witnessed the rise of Nazism, and watched war clouds gather over the Continent. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

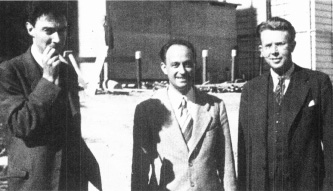

Robert Oppenheimer and Ernest Lawrence summering at Oppenheimer’s New Mexico ranch, 1931. They were very different, but they complemented each other professionally and liked each other personally—until political differences after the war sundered their friendship. (Molly B. Lawrence, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, and Ernest Lawrence at the Rad Lab, Berkeley, in the summer of 1937. Fermi was visiting America from Italy, which he would leave the following year to escape Fascist persecution of his Jewish wife and children. (Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection)

Participants at the Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics, January 1937. The annual conference attracted talented physicists from both sides of the Atlantic. Those attending in 1937 included Hans Bethe (front row, fourth from left), I. I. Rabi (above Bethe’s left shoulder), Niels Bohr (front row, second from right, wearing scarf), and Edward Teller (partially obscured, standing directly behind Bethe, two rows up). (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gamow and Physics Today Collections)

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

Leslie Groves (1896–1970), U.S. army general who directed the Manhattan Project during the war. He oversaw all aspects of the project: scientific, production, security, and planning for use of the bomb. Under his direction, project plants were built at Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico. (© CORBIS)

A weekend hiking excursion in the Jemez Mountains near Los Alamos, winter 1944–1945. Such outings offered one of the few opportunities for scientists such as Enrico Fermi and Hans Bethe (first and second on left) to relieve the stress of working on the bomb. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Segrè Collection)

Niels Bohr on the ski hill above Los Alamos, January 1945. Bohr used such occasions to listen to other physicists’ anxieties about the bomb and to share his own views about the bomb’s revolutionary implications. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Segrè Collection)

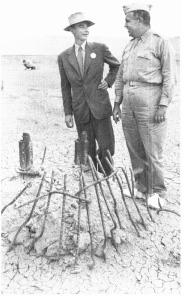

Robert Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves at the Trinity Site near Alamogordo, New Mexico, two months after the July 16, 1945, test. Intense heat generated by the world’s first atomic explosion vaporized the hundred-foot steel tower holding the bomb, gouged an enormous crater in the ground, and fused the surrounding sand into jadelike crystals. (© Bettmann/CORBIS)

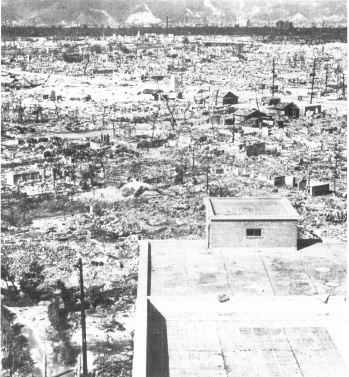

Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb attack on August 6, 1945. The explosion caused widespread destruction, vividly illustrated by this photograph taken shortly after the attack. Civilians outnumbered soldiers in Hiroshima more than six to one. Over 75,000 inhabitants of the city perished that day, and tens of thousands more afterward due to burns, radiation, and other sicknesses. (© Bettmann/CORBIS)

AFTER THE WAR

Robert Oppenheimer’s signature porkpie hat on the cover of the May 1948 issue of Physics Today eloquently conveyed his fame after the war. Until his downfall in 1954, Oppenheimer remained America’s most celebrated and influential physicist. (Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection)

Ernest Lawrence and Robert Oppenheimer together at Berkeley, 1946. Growing political differences between them after the war—over the superbomb in particular—eroded their storied friendship, which had been weakened when Oppenheimer left Berkeley for Princeton in 1947 and ended as a result of Oppenheimer’s security hearing in 1954. (© AP/Wide World Photos)

Edward Teller and Enrico Fermi together at the University of Chicago, 1951. By this time, the superbomb had become Teller’s fixation. But he failed to convince his good friend Fermi to support a crash program to develop the thermonuclear weapon. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

As his lobbying for the superbomb and his testimony against Oppenheimer estranged him from many other physicists in the 1950s, Edward Teller increasingly sought the friendship and support of political conservatives and military officers (such as General Joseph Garvin, pictured here). (National Archives and Records Administration, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

TWILIGHT YEARS

Enrico Fermi boating off the island of Elba, 1954. This photograph, taken during Fermi’s last visit to his homeland a few months before his death, shows the ravages that undiagnosed stomach cancer had begun to take on the previously vigorous Fermi. Physicists mourned his premature death later that year. (Amaldi Archives, Dipartimento di Fisica, Università “La Sapienza,” Rome, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

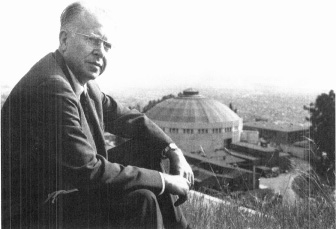

Ernest Lawrence sitting on a hill above the Berkeley campus and the dome of the sprawling Rad Lab, surveying the extraordinary empire he had built, 1958. The ulcerative colitis that had plagued this energetic and driven man finally killed him later that year. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection)

Niels Bohr receiving the prestigious Atoms for Peace Award from President Eisenhower, with Arthur Compton (second from left) and Lewis Strauss (far left) looking on, 1957. Strauss had orchestrated the vendetta that brought down Bohr’s good friend Robert Oppenheimer three years earlier. Bohr and Compton both died in 1962. (Niels Bohr Archive, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Leo Szilard with former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a few years before his death from a heart attack in 1964. Until the end, Szilard remained what he had always been: a dreamer, a gadfly, and the moral conscience of his generation of physicists. (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

A chastened and reflective Robert Oppenheimer after the revocation of his security clearance, late 1950s. His story was a personal tragedy—and the tragedy of his generation of physicists, who opened Pandora’s box and ushered nuclear weapons into the world. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection)

I. I. Rahi at the fortieth anniversary commemoration of the founding of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1983. At the commemoration, Rabi spoke with conscious and courageous irony of “how well we meant.” He died in 1988. (Photograph by Sam Treiman, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection)

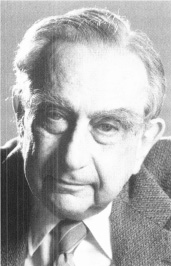

Edward Teller in his eighties, in a photograph taken in his office at the Hoover Institution in Stanford, California, where he continued in interviews to voice the argument for nuclear weapons well into his nineties. (© Roger Ressmeyer/CORBIS)

An insecure pessimist, Edward Teller found refuge from his anxieties at the piano, where he played sonatas by Mozart and Beethoven. (Photo by Fred Rothwarf, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Hans Bethe in his nineties, the grand old man of American physics until his death in the early twenty-first century and sharp critic of the nuclear arms race. Bethe and Teller became two lions contesting the legacy of their momentous creation. (AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Segrè Collection)

Although Stimson sought to create an atmosphere in which everyone felt free to discuss any problem related to atomic energy,

he opened the meeting by reminding Compton, Lawrence, Oppenheimer, and Fermi that he and Army Chief of Staff Marshall were

the ones responsible for making recommendations on military matters to the president. Stimson was anxious, however, to impress

upon them “that we were looking at this like statesmen and not like merely soldiers anxious to win the war at any cost.”

30

To corroborate his point, Stimson read from handwritten notes he had prepared for the meeting:

Its size and character

We don’t think it mere new weapon

Revolutionary Discovery of Relation of man to universe

Great History Landmark like

Gravitation

Copernican Theory

But,

Bids fair [to be] infinitely greater, in respect to its Effect

—on the ordinary affairs of man’s life.

May destroy or perfect International Civilization

May [be] Frankenstein or means for World Peace

31

Compton then gave a terrifying seminar on the future of nuclear weapons. He explained that the atomic bombs nearing completion were only the first step along the road of nuclear weapons technology. In the not too distant future, Compton soberly observed, loomed the awesome prospect of a “superbomb” perhaps a thousand times more destructive. Oppenheimer then explained how unimaginably destructive a superbomb would be: an atomic bomb was expected to have an explosive force of 2,000 to 20,000 tons of TNT; a superbomb might produce an explosive force of 10,000,000 to 100,000,000 tons of TNT. If an atomic bomb could effectively destroy a city, those present could only wonder in fright at what an explosive force of this magnitude would destroy.

The implication to Lawrence was inescapable: the United States would be in mortal danger if and when another country acquired such a bomb. Lawrence urged staying ahead of the rest of the world by expanding the weapons lab at Los Alamos and stockpiling atomic bombs. Compton agreed. Oppenheimer did not, fearing an arms race as soon as the Soviet Union took up the challenge.

The committee then took up the issue of international control. Byrnes asked how long it would take for the Soviet Union to catch up. 32 Groves estimated at least twenty years. The scientists disagreed, estimating Russia could build a bomb in four to six years. * Oppenheimer put the point vividly. “Our monopoly is like a cake of ice melting in the sun,” he said. 33 Drawing on his talks with Bohr at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer urged that Washington contact Moscow promptly about joining in a system of international control without giving them details of the progress achieved. Marshall agreed, saying it might be desirable to invite Russian scientists to witness the first atomic bomb test scheduled for July in New Mexico. Byrnes strenuously objected. He said Stalin would ask to be brought into the project—and that was unacceptable. Byrnes believed the bomb’s diplomatic utility would be diminished if Stalin was informed of the weapon prior to its use. He favored seeking international control while maintaining U.S. atomic superiority. Such a strong statement by a man of Byrnes’s influence and prestige was not to be dismissed lightly. No one challenged him—nor expressed die contradiction between these objectives. 34

Everyone except Marshall then adjourned to a dining room across the hall for lunch. The conferees sat around four tables. Discussion centered on whether or not to use the bomb against Japan—the only time this crucial and fundamental question would ever be formally addressed. Given the bomb’s momentous implications, and in light of all the subsequent controversy about its use, it is striking how virtually no one in the inner circle of decision making seriously contemplated not dropping it. To a degree that later generations would find remarkable, the advent of the nuclear age was heralded by little formal deliberation. Events were in the saddle, and they rode men hard.

The talk was brief, lasting ten minutes. Lawrence repeated a suggestion he had made that morning for a nonmilitary demonstration. A political naif, he thought the weapon would not actually be used. “The bomb will never be dropped on people,” he had assured the chairman of Berkeley’s physics department. “As soon as we get it, we’ll use it only to dictate terms of peace.” 35 Compton asked whether it was possible to give the Japanese an opportunity to witness the weapon’s tremendous power before it was dropped on them. Stimson invited comments. The reaction was negative: the weapon might be a dud; a failure would strengthen Japan’s morale; if the Japanese received a prior warning, they might take steps to block it; fanatical militarists would be unimpressed by a demonstration; the Japanese might move American prisoners of war into the test area.

Oppenheimer then reported an estimate prepared at Los Alamos of the number of deaths that would be caused if an atomic bomb were exploded over a city. (The estimate—twenty thousand—was based on the erroneous assumption that a city’s inhabitants would seek shelter before the bomb went off.) A participant soberly noted that this number would be no greater than the number killed in the Tokyo fire raid—far less, in fact. The outcome, Compton later wrote, was that “no one could suggest a way in which [a demonstration] could be made so convincing that it would be likely to stop the war.” 36

Returning to Stimson’s office after lunch, the participants took up the bomb’s probable impact on Japan’s will to fight. Someone again observed that its destructive effect might not differ much from the B-29 fire raids incinerating Japan’s cities. Oppenheimer predicted that the visual effect of the bomb would be “tremendous” and for the first time mentioned radiation, but he did not mention the possibility of lingering illness.

Stimson expressed the conclusion, on which there was general agreement, that the Japanese should not be given any warning. He said the bomb should not be dropped on a civilian area, but an attempt should be made to make a profound psychological impression on as many Japanese as possible. The preferred target would be a war plant closely surrounded by workers’ homes. None of those present, however, noted the contradiction in their logic: a bomb powerful enough to destroy an entire city would surely kill thousands—probably tens of thousands—of civilians if dropped anywhere near workers’ homes. Compton, Lawrence, Oppenheimer, and Fermi perhaps understood this contradiction best because they knew best how destructive the bomb would be, but at no time did they point it out. Perhaps it was because the four of them felt such views would find little sympathy at such a meeting. Perhaps it was because they themselves were too invested in the project. Or perhaps it was because they did not want to admit to themselves what the human costs of their creation’s use would be. * But the dilemma that policy makers and scientists preferred not to face was all too real. And it remained on Compton’s mind. “What shall I tell Szilard?” he asked Oppenheimer as the session broke up. Oppenheimer gave no answer. 37 Stimson informed Truman of the committee’s recommendation on June sixth. The decision to use the bomb was inherent in the decision made years before to build it. The momentum of that process was rapidly building toward an all but inevitable climax.

Compton returned to Chicago knowing that he faced a growing gulf between the views of the Interim Committee and the Met Lab scientists under his direction. He reported to his restless constituents on the afternoon of June second, immediately after his arrival from Washington. Constrained by the secrecy rule that the Interim Committee had imposed on its science advisers, Compton did not disclose that a recommendation had been made to drop the bomb on Japan without warning. Instead, he told his audience that the Science Advisory Panel would meet again in mid-June in Los Alamos.

Szilard sat in the audience glumly listening to Compton. His respect for policy makers had hit a new low after his meeting with Byrnes in Spartanburg. Szilard also lacked confidence in the Scientific Advisory Panel. He believed that Oppenheimer would not oppose dropping the bomb after laboring so long and hard to make it; that Fermi would state his views privately but would not speak up; and that Compton would not risk incurring the displeasure of the Washington Establishment. And he faced the renewed wrath of Groves, who had learned about his unauthorized trip to Spartanburg.

Groves demanded an explanation from Szilard’s Met Lab boss—a military officer who had taken Szilard’s approach of going through outside channels might well find himself court-martialed or transferred to some snowy base in Greenland. The usually even-tempered Compton exploded in an answering letter to Groves. “I believe the reason for their action is that with regard to the Project their responsibility to the nation is prior to and broader than their responsibility to the Army, and they felt that a situation had developed in which they could not perform their duty to the nation working through me or through the Army.” Compton made it clear to Groves that he shared their uneasy feelings:

The scientists who were responsible for initiating and developing this project have felt that its control has been taken from them, that they are uninformed with regard to plans for its use and its development, and that they have had little assurance that serious consideration of its broader implications is being given by those in a position to guide national policy. The scientists will be held responsible, both by the public and by their own consciences, for having faced the world with the existence of the new powers. The fact that the control has been taken out of their hands makes it necessary for them to plead the need for careful consideration and wise action to someone with authority to act. There is no other way in which they can meet their responsibility to society.

After pointing out that time and again their efforts to get their concerns to those with authority to act had been bottled up in channels, Compton asked, “To whom then were the scientists to go in order to obtain an effective consideration of their views on the use and further development of the Project?” He pointedly added that the Jeffries Report, which he had passed to Groves, had not reached policy makers. The gentle Compton even permitted himself an attack on outgoing Secretary of State Edward Stettinius for failing to explain the atomic dilemma to the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco on April twenty-fifth. “His appreciation was so limited as possibly to serve as a hazard to the country’s welfare,” Compton charged. He placed the blame for this squarely on Groves, who had briefed Stettinius about the bomb before the UN conference. 38

To meet both Groves’s demand that scientists adhere to the chain of command and the Met Lab scientists’ concern that policy makers consider their opinions about the use of the bomb, Compton organized a committee to study and report on the bomb’s implications. Compton promised to deliver their findings personally in Washington. 39 Chaired by Nobel laureate and Nazi refugee James Franck, the committee produced a perceptive study. Franck was a highly principled physicist who had openly criticized the Nazis—a rare and courageous gesture—before being driven out of Germany. In 1934 he went to Copenhagen to join his friend Bohr; later, he moved on to America—first to Johns Hopkins University and then to the University of Chicago, which became his home. Other physicists considered Franck a saint and a martyr. Mournful looking, retiring, and unpretentious, Franck fretted about the consequences of weapons work and had taken charge of the Met Lab’s chemistry section in 1942 only after securing a promise from Compton that he would be heard at a high level when the time came to decide how the bomb would be used.

The Franck Report took as its fundamental premise the fact that “the manner in which this new weapon is introduced to the world will determine in large part the future course of events.” It warned that the bomb opened the way to “total mutual destruction” of all nations. It predicted the almost limitless destructive power of nuclear weapons and the elusive security that any attempt at monopoly would bring. 40 And it stressed the widening gap between technological progress and traditional conceptions of war:

Nuclear bombs cannot possibly remain a “secret weapon” at the exclusive disposal of this country for more than a few years. The scientific facts on which their construction is based are well known to scientists of other countries. Unless an effective international control of nuclear explosives is instituted, a race for nuclear armaments is certain to ensue following the first revelation of our possession of nuclear weapons to the world….

We believe that these considerations make the use of nuclear bombs for an early unannounced attack against Japan inadvisable. If the United States were to be the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction upon mankind, she would sacrifice public support throughout the world, precipitate the race for armaments, and prejudice the possibility of reaching an international agreement on the future control of such weapons.

The Franck Report argued against using the bomb, even “if one takes the pessimistic point of view and discounts the possibility of an effective international control over nuclear weapons at the present time.” In this case, the report concluded, “the advisability of an early use of nuclear bombs against Japan becomes even more doubtful—quite independently of any humanitarian considerations. If an international agreement is not concluded immediately after the first demonstration, this will mean a flying start toward an unlimited armaments race.” The report rested its argument against dropping the bomb on Japan on the ground that announcing its existence to the world in this way would make international control virtually impossible. The report urged instead a demonstration of the bomb over an uninhabited area before a group of international observers. “A demonstration of the new weapon might best be made before the eyes of representatives of all the United Nations on the desert or a barren island. This may sound fantastic, but in nuclear weapons we have something entirely new in order of magnitude of destructive power, and if we want to capitalize fully on the advantage their possession gives us, we must use new and imaginative methods.” The scientists hoped to shock the world into international cooperation. 41

Compton kept his word by accompanying Franck to Washington to discuss a preliminary draft of the report with Vice President Wallace at a breakfast meeting arranged by Compton on April twenty-first. 42 They also tried to see Secretary of War Stimson at the Pentagon on June twelfth, but the secretary did not make himself available. Compton left the Franck Report for Stimson with a covering note that faulted it for failing to consider what Compton thought was the most important issue at hand. “While it calls attention to difficulties that might result from the use of the bomb,” wrote Compton, it “does not mention the probable net saving of many lives, * nor that if the bomb were not used in the present war the world would have no adequate warning as to what was to be expected if war should break out again.” 43

Unlike Franck, who hoped to avert an atomic attack, Compton hoped such an attack would be the last terrible act of World War II and serve notice that there must be no World War III. This grandson of pacifist Mennonites knew all too well the destruction and human agony the bomb would cause; he had been living with this realization for four years. “But I wanted the war to end,” Compton later wrote. “I wanted life to become normal again. I saw a chance for an enduring peace that would be demanded by the very destructiveness of these weapons. I hoped that by use of the bombs many fine young men I knew might be released at once from the demands of war and thus be given a chance to live and not to die.” 44 Compton was especially haunted by the semester he had spent at the University of Cambridge in the fall of 1919. Among his students that fall were many who had been crippled and blinded during the Great War. He often saw crutches leaning against chairs in the lecture halls. It was a sadly poignant sight—they were so young. What had sunk most deeply into Compton’s soul was not the sight of legless young men but the awareness that so many others who should have been there lay buried in the mud of Flanders’ fields.

Compton took the Franck Report along with him to a meeting of the Scientific Advisory Panel in Los Alamos on June sixteenth. The panel was meeting in Oppenheimer’s office that day when Stimson’s assistant George Harrison phoned and said they, not the Interim Committee, should consider the Franck Report and examine the possibility of devising a nonmilitary demonstration that would be sufficiently convincing to effect Japan’s surrender. Harrison’s call charging the panel to reconsider use of the bomb against Japan in the light of the Franck Report created a tense and soul-searching atmosphere. Compton later described the harsh dilemma that he and his three colleagues felt at that moment:

We were keenly aware of our responsibility as the scientific advisers to the Interim Committee. Among our colleagues were the scientists who supported Franck in suggesting a nonmilitary demonstration only. We thought of the fighting men who were set for an invasion which would be so very costly in both American and Japanese lives. We were determined to find, if we could, some effective way of demonstrating the power of an atomic bomb without loss of life that would impress Japan’s warlords. If only this could be done!

The difficulties of making a purely technical demonstration that would carry its impact effectively into Japan’s controlling councils were indeed great. We had to count on every possible effort to distort even obvious facts. Experience with the determination of Japan’s fighting men made it evident that the war would not be stopped unless these men themselves were convinced of its futility. 45

The possible failure of a demonstration bomb also worried them, as did the specter of a bloody invasion of Japan if the bomb failed to end the war. But, of course, they had more than just the war in mind. In their opinion, the weapon’s postwar influence depended on a widespread recognition of new realities—the new weapon required a new attitude toward war. If Japan did not accept this view, the war might continue; if the Soviet Union ignored it, the peace would be lost. They concluded that combat use of the bomb would make a deep impression on both countries, convincing those who needed to be convinced to end the war, and persuading those who needed to be persuaded that postwar cooperation was imperative. Compelled initially by fear of German progress, and now terrified by the consequences of their own success, these men of sensibility, culture, and peace were driven to recommend policies that they would have found abhorrent in other circumstances.

There was not unanimous agreement, however. Lawrence again pressed for a demonstration, or at least an explicit warning, before the bomb was dropped on Japan. Fermi also resisted. This was highly unusual. Fermi disliked expressing political opinions. Now, he boldly argued not for a demonstration, but for no drop at all. Nations will always fight wars, he said, therefore scientists could not responsibly place atomic bombs in national arsenals. It took Compton and Oppenheimer until 5:00 the following morning to “talk him down,” Oppenheimer later noted. 46 In the end, Fermi gave in, Compton and Oppenheimer’s logic prevailing: it was better to have the bomb used once so that people everywhere learned just how awful it was. *

Oppenheimer reported to Washington the panel’s conclusion that it could “propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war” and that there was “no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” “Our hearts were heavy as we turned in this report to the Interim Committee,” Compton later wrote. “We were glad and proud to have had a part in making the power of the atom available for the use of man. What a tragedy it was that this power should become available first in time of war and that it must first be used for human destruction.” 47

Oppenheimer would later regret publicly the lack of farsightedness and political courage that the Scientific Advisory Panel demonstrated at this crucial weekend meeting in June. His feeling of failure may have been compounded by the realization that if he, Compton, Lawrence, and Fermi had endorsed the recommendation of the Franck Report that weekend, their endorsement might have forced a high-level reconsideration of use-without-warning. But then no one in Washington, either, spent a fraction of the time and thought reviewing the arguments of the Franck Report that its drafters put into formulating them. The remarkably prescient report made little impression on policy makers who saw their first responsibility as ending the war victoriously.

Compton, Lawrence, Oppenheimer, and Fermi also had made ending the war, rather than the bomb’s impact after the war, their controlling consideration. This was not surprising. To have acted otherwise, at the time and under the circumstances, would have required political vision and courage that the atomic scientists, at this juncture, did not possess. This was clear when, having made their recommendation to Stimson, they added: “With regard to these general aspects of the use of atomic energy, it is clear that we, as scientific men, have no proprietary rights. It is true that we are among the few citizens who have had occasion to give thoughtful consideration to these problems during the past few years. We have, however, no claim to special competence in solving political, social, and military problems which are presented by the advent of atomic power.” 48 To some extent, they were just being polite. But to another, their recusal was evidence that despite increasing awareness, they subscribed to the axiom—common in their day—that scientists should not offer political judgments. Their attitude would change dramatically in subsequent years.

Bohr, however, felt no reluctance about speaking out. After the May thirty-first Interim Committee meeting, Oppenheimer went over to the British Embassy, where Bohr was staying. “I met Bohr and tried to comfort him,” Oppenheimer remembered later, “but he was too wise and too worldly to be comforted…. He [was] quite uncertain about what, if anything, would happen.” 49 Tellingly, Oppenheimer added this about Bohr (and himself) years later: “He was for statesmen; he used the word over and over again. He was not for committees and the Interim Committee was a committee.” 50

Bohr felt that time was running out. Before leaving the United States to return to his liberated Denmark, Bohr asked Frankfurter to arrange one last meeting for him with Stimson. On June eighteenth, Stimson’s assistant Harvey Bundy sent the following in a message to his boss: “Do you want to try and work in a meeting with Professor Bohr, the Dane, before you get away this week?” Stimson scrawled no in the margin of the message. 51 Bohr gave up and a few days later sailed for Europe.

* * *

Szilard sensed that things were moving fast now, and that he must act quickly if he hoped to avert what he considered a tragedy. Appalled at the firebombing of civilians, he felt frightened by the gathering force of events. In early July he decided to draft a petition to President Truman arguing against use of the atomic bomb on moral grounds. 52

The sense of urgency and responsibility that Szilard felt came through forcefully in his covering letter to colleagues:

Enclosed is the text of a petition which will be submitted to the President of the United States. As you will see, this petition is based on purely moral considerations.

However small the chance might be that our petition may influence the course of events, I personally feel that it would be a matter of importance if a large number of scientists who have worked in this field went clearly and unmistakably on record as to their opposition on moral grounds to the use of these bombs in the present phase of the war.

Many of us are inclined to say that individual Germans share the guilt for the acts which Germany committed during this war because they did not raise their voices in protest against those acts. Their defense that their protest would have been of no avail hardly seems acceptable even though these Germans could have had protests without running risks to life and liberty. We are in a position to raise our voices without incurring any such risks even though we might incur the displeasure of some of those who are at present in charge of controlling the work on “atomic power.”

The fact that the people of the United States are unaware of the choice which faces us increases our responsibility in this matter since those who have worked on “atomic power” represent a sample of the population and they alone are in a position to form an opinion and declare their stand…. 53

In the petition Szilard argued that the United States bore special moral responsibility for being the first nation to develop the bomb:

The development of atomic power will provide the nations with new means of destruction. The atomic bombs at our disposal represent only the first step in this direction, and there is almost no limit to the destructive power which will become available in the course of their future development. Thus a nation which sets the precedent of using these newly liberated forces of nature for purposes of destruction may have to bear the responsibility of opening the door to an era of devastation on an unimaginable scale.

If after this war a situation is allowed to develop in the world which permits rival powers to be in uncontrolled possession of these new means of destruction, the cities of the United States as well as the cities of other nations will be in continuous danger of sudden annihilation. All the resources of the United States, moral and material, may have to be mobilized to prevent the advent of such a world situation. Its prevention is at present the solemn responsibility of the United States—singled out by virtue of her lead in the field of atomic power.

The added material strength which this lead gives to the United States brings with it the obligation of restraint and if we were to violate this obligation our moral position would be weakened in the eyes of the world and in our own eyes. It would then be more difficult for us to live up to our responsibility of bringing the unloosened forces of destruction under control.

Szilard opposed the atomic bombing of Japan on the moral ground that it would open “the door to an era of devastation on an unimaginable scale.” 54

Sixty-seven Met Lab scientists signed Szilard’s petition. The scientists who did not told Szilard that more lives would be saved by using the atomic bomb than by continuing the bloody war without it. Thousands of American—to say nothing of Japanese—soldiers were being killed each week, and they felt they would be guilty of permitting this slaughter to continue if they did not urge use of the bomb to end the war. Still others felt that patriotism demanded the bomb’s use. “Are we to go on shedding American blood when we have available the means to speedy victory?” one note angrily demanded. “No! If we can save even a handful of American lives, then let us use this weapon—now! These sentiments, we feel, represent more truly those of the majority of Americans and particularly those who have sons in the foxholes and warships of the Pacific.” 55

Szilard also sent a copy of his petition to friends at Los Alamos. “I hardly need to emphasize that such a petition does not represent the most effective action that can be taken in order to influence the course of events,” he wrote to Oppenheimer and other scientists on the Hill. “But I have no doubt in my own mind that from a point of view of the standing of the scientists in the eyes of the general public one or two years from now it is a good thing that a minority of scientists should have gone on record in favor of giving greater weight to moral arguments.” 56

Szilard urged Teller to both sign the petition and gather signatures for it. Before deciding what to do, Teller went to see Oppenheimer, who answered him in a polite and convincing way by questioning Szilard’s political judgment. “What does he know about Japanese psychology?” Oppenheimer told Teller. “How can he judge the way to end the war? The people in Washington are very wise, they know all the facts. Szilard knows nothing. Don’t do anything.” 57 Teller complied, and wrote Szilard a letter to that effect:

Dear Szilard:

Since our discussion I have spent some time thinking about your objections to an immediate military use of the weapon we may produce. I decided to do nothing. I should like to tell you my reasons.

First of all let me say that I have no hope of clearing my conscience. The things we are working on are so terrible that no amount of protesting or fiddling with politics will save our souls.

This much is true: I have not worked on the project for a very selfish reason and I have gotten much more trouble than pleasure out of it. I worked because the problems interested me and I should have felt it a great restraint not to go ahead. I can not claim that I simply worked to do my duty. A sense of duty could keep me out of such work. It could not get me into the present kind of activity against my inclinations. If you should succeed in convincing me that your moral objections are valid, I should quit working. I hardly think that I should start protesting.

But I am not really convinced of your objections. I do not feel that there is any chance to outlaw any one weapon. If we have a slim chance of survival, it lies in the possibility to get rid of wars. The more decisive a weapon is the more surely it will be used in any real conflict and no agreements will help.

Our only hope is in getting the facts of our results before the people. This might help to convince everybody that the next war would be fatal. For this purpose actual combat-use might even be the best thing.

And this brings me to the main point. The accident that we worked out this dreadful thing should not give us the responsibility of having a voice in how it is to be used. This responsibility must in the end be shifted to the people as a whole and that can be done only by making the facts known. This is the only cause for which I feel entitled in doing something: the necessity of lifting the secrecy at least as far as the broad issues of our work are concerned. My understanding is that this will be done as soon as the military situation permits it.

All this may seem to you quite wrong. I should be glad if you showed this letter to Eugene [Wigner] and to [James] Franck who seem to agree with you rather than with me. I should like to have the advice of all of you whether you think it is a crime to continue to work. But I feel that I should do the wrong thing if I tried to say how to tie the little toe of the ghost to the bottle from which we just helped it escape.

With best regards.

Yours,

E. Teller

58

Teller did not mention Oppenheimer’s opposition to the petition in his letter to Szilard because he knew that Oppenheimer would see the letter before it was sent. 59 In later years, Teller looked back on his refusal to sign Szilard’s petition—and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—as mistakes. In 1962 he wrote:

I am convinced that the tragic surprise bombing was not necessary. We could have exploded the bomb at a very high altitude over Tokyo in the evening. Triggered at such a high altitude, the bomb would have created a sudden, frightening daylight over the city But it would have killed no one. After the bomb had been demonstrated—after we were sure it was not a dud—we could have told the Japanese what it was and what would happen if another atomic bomb were detonated at low altitude.

After the Tokyo demonstration, we could have delivered an ultimatum for Japanese surrender. The ultimatum, I believe, would have been met, and the atomic bomb could have been used more humanely but just as effectively to bring a quick end to the war. But to my knowledge, such an unannounced, high altitude demonstration over Tokyo at night was never proposed. 60

And in 1987 he wrote:

I eventually felt strongly that action without prior warning or demonstration was a mistake. I also came to the conclusion that, although the opinions of scientists on political matters should not be given special weight, neither should scientists stay out of public debates just because they are scientists. In fact, when political decisions involve scientific and technical matters, they have an obligation to speak out.

I failed my first test at Los Alamos, but subsequently I have stood by that conviction. 61

“Could we have avoided the tragedy of Hiroshima?” he wondered. “Could we have started the atomic age with clean hands?” 62 The questions would haunt him to the end of his life. 63

I. I. Rabi did not share Teller’s opinion. When Rabi arrived on the Hill in mid-July, he told Oppenheimer that the war was almost over, that the Japanese were as good as defeated, but that it was wishful thinking to expect Truman not to use the bomb. Rabi, who had an office in Washington and understood the mood of the capital, could sense the determination—even the zeal—there to end the war quickly and decisively. Rabi’s view was equally jaundiced about cowing Japan with a demonstration. He saw no way to shake them with such a gambit. Who would evaluate such a demonstration—the emperor? “This is absurd,” he told Oppenheimer. It would be empty “fireworks.” Only the destruction of a city would be “incontrovertible.” 64

Oppenheimer was under intense pressure from Groves to prevent political debate over the bomb on the Hill. Oppenheimer’s job, the general repeatedly told him, was to finish the “gadget”—nothing else. Early on, Oppenheimer had fought compartmentalization by telling Groves that scientists would work more effectively if they were permitted unfettered discussion among themselves. Groves had acceded to Oppenheimer’s request, but he had extracted a promise in return: Oppenheimer would limit discussions strictly to scientific matters. Groves used the bargain he struck with Oppenheimer in the spring of 1943 to restrict debate about use of the bomb in the summer of 1945.

Although Oppenheimer stopped Szilard’s petition, no one at Los Alamos was more concerned than he was about the role atomic bombs would play after the war. But Oppenheimer did not think that scientists could do much about postwar problems while the war was still going on. Better informed than any other scientist on the Hill about the state of play in Washington, Oppenheimer perhaps also realized that scientists, at the end of the day, had no real voice in the decision to use the bomb. He also probably knew that those who did have a voice had no need for the opinions of those at Los Alamos or the Met Lab.

An incident earlier in the year suggested Oppenheimer was right. As Allied forces raced toward the heart of Germany, U.S. Army Intelligence discovered that the Nazis had no atomic bombs. Soon after this was learned, the sensational news swept like wildfire through the Manhattan Project laboratories, where it was eagerly discussed. “Isn’t it wonderful that the Germans have no atom bomb?” a physicist said to an army liaison officer at one of the labs. “Now we won’t have to use ours.” The officer, schooled in the ways of the military and of Washington, looked at him for a long moment, rolled his eyes, shook his head, and said, “Of course you understand that if we have such a weapon we are going to use it.” His reply shocked the naive physicist. 65

Truman never saw Szilard’s petition. Szilard gave it to Compton on July nineteenth, and asked him to keep the signers’ names secret from Groves. Compton did so, sealing it in a manila envelope addressed “To The President of the United States.” Also included in the envelope was a poll of 150 Met Lab scientists who had been asked to choose among five possible courses of action. By far the largest number, 46 percent, voted to “give a military demonstration in Japan, to be followed by a renewed opportunity to surrender before full use of the weapon is employed.” The phrase “military demonstration in Japan” was later interpreted by officials in Washington to mean an attack without warning, but many of the polled scientists subsequently contended that they meant just the opposite: the phrase “before full use of the weapon is employed” meant that they first wanted a demonstration that would not kill a large number of civilians. 66

After checking with Groves, Compton sent the package to Groves’s deputy, Colonel Kenneth Nichols, on July twenty-fourth, noting that “since the matter presented in the petition is of immediate concern, the petitioners desire the transmission occur as promptly as possible.” 67 When Nichols received the package on July twenty-fifth, he sent it by special military courier to Groves in Washington, urging “that these papers be forwarded to the President of the United States with proper comments.” 68 Groves delayed sending the package to Secretary Stimson’s office until August first—after Truman had left Washington for the Potsdam Conference and a telex from Tinian Island in the western Pacific had assured him that the atomic bomb was ready for combat use against Japan. 69