Kathleen P. Long

Art, anatomy, and archeology come together in the sixteenth century to create a conception of the human body that is radically different from that presented in medieval medical works. This conception of the human body is idealizing, based as it is on classical sculptural representations of the gods, and it will come to dominate early modern, and arguably modern, medical notions of the normal, healthy body. Thus, well before the modern era, the stage is set for a narrowly normalizing view of how the human body should look. This normalizing view also focuses primarily on an idealized masculine body, with the feminine version presented as an afterthought. For example, in Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basel, 1543), the female body is only represented in a discussion of reproductive organs, with only a torso view of that body. Relative to all other parts of the body, the masculine form is the norm. This way of conceptualizing medicine has in fact predominated to the present day; it is only recently that medical studies have focused on women’s bodies other than the reproductive organs. In the early modern period, illustrated alchemical treatises offered an alternative to the masculine, strongly idealizing, norm presented in medical manuals. Feminine and feminized masculine bodies are frequently represented, and even forms deemed monstrous, such as the hermaphroditic double-headed rebis, are presented as central to the alchemical process. Those crippled by injury or illness, for example a diseased king, are often also presented as images of the alchemical process. Whereas the diseased or radically different body had only a limited place in medical illustrations of the sixteenth century, these bodies are omnipresent in alchemical works. In this study, Michael Maier’s alchemical emblem book, the Atalanta fugiens, because of the striking nature of its visual images and their relation to the work of Vesalius, will serve as an example of the alchemical corpus. This corpus offers an alternative to the predominantly normalizing and masculinizing images of the human body found in the most widely disseminated treatises on anatomy.

Lawrence M. Principe and William R. Newman opened a debate in their article “Some Problems with the Historiography of Alchemy” (2001)1 concerning the validity of reading alchemical symbolism as anything other than a straightforward code for the materials and the processes of alchemical practice. This insistence on the “chemical” meaning of alchemical imagery and language was a corrective to anachronistic psychoanalytic readings of alchemical treatises, but in some sense Principe and Newman may have overcorrected. Hereward Tilton takes on their arguments in his book on Michael Maier, contending that the larger cultural context in which these works were created should also enter into consideration. I would agree with Tilton that alchemical symbolism can be read in a number of ways and as having a number of meanings,2 some inherently a part of various aspects of the alchemical process, and some “accidental” (that is to say, clearly not referring to the alchemical process itself). I will be reading the Atalanta in a wider context, partly because alchemical symbolism was echoed in the wider context of court poetry and political polemic3 and partly because this symbolism was itself drawn from that wider context. While it is hard to know whether alchemical imagery deliberately provided a critique of other cultural productions (such as anatomical treatises) or whether the reuse of these productions was merely fortuitous, the truth is that alchemy provides a repository of images and ideas that often serve as alternatives to those arising from more officially sanctioned milieus (the University, in the case of anatomical treatises, as well as religious and political notions of acceptable gender roles).

In this reading of the Atalanta, I diverge from some previous readings of the work, most particularly that of Sally G. Allen and Joanna Hubbs, who read Maier’s images and commentary, and by extension all alchemical works, as relentlessly masculinist:

Alchemical symbolism, rich in both mythological and biological allusion, presents the image of the opus as the wresting of an embryo from the womb of the earth, embodied in women, a birth from a man-made alembic. This recurrent symbolism in alchemical works suggests an obsession with reversing, or perhaps even arresting, the feminine hegemony over the process of biological creation.4

I have also pointed out the frequent effacement of the feminine in some alchemical works, particularly those of Paracelsus.5 But I would also strongly agree with Didier Kahn, who presents alchemy as a complex web of practices that change over time and according to the varied contexts in which they arise.6 The central role given to the figure of the rebis, or alchemical hermaphrodite, at least following the publication of the Rosarium philosophorum (1550)7 on (if not from much earlier), can only render the notion of an all-encompassing masculinist ideology in alchemy problematic at best. Particularly significant is the fact that the hermaphrodite, which represents the stage of conjunction (of Sol and Luna, mercury and sulphur) of the masculine and feminine principles or elements, retains two distinct gender identities in one body.

I would further argue that, while the various images of feminized masculinity, of the union of the sexes, and the exhortations to the (supposedly male) alchemist to do “women’s work” can be read as appropriations of women’s role in procreation, they are also queer in the sense of constantly shifting gender roles and effacing gender boundaries. A pregnant man is not a simple masculinist effacement of the feminine. And, in fact, the repressed feminine returns constantly in the Atalanta, not only as the Earth nursing the Philosopher’s Stone or as a woman working, but as the sister of the conjunction, as Luna who fights the dragon alongside Sol, as Aphrodite joining with Hermes to create the rebis. In emblem 42, the alchemical philosopher follows Nature (represented as a woman) rather than mastering her.

The fact is that alchemy was such a vast range of practices, both in geographical and what we would call today “disciplinary” scope, that its images and commentaries were often inflected to suit particular contexts. So, while the penultimate image of the Rosarium philosophorum is the Father, Son, and Holy Mother (presumably the Virgin Mary),8 in keeping with the emphasis on the conjunction of masculine and feminine that pervades the treatise, the insistently masculine De Lapide Philosophico Libellus ends with the Father, Son, and the male Guide (presented as a sort of angel or Holy Spirit).9 There is no feminine figure in Lambsprinck’s work, while the feminine is a constant presence in the Rosarium; this contrast is merely a sample of the vast range of alchemical imagery.

Furthermore, consideration of alchemical works in the context of other scientific images and discourses reveals some pronounced differences in emphasis. A quick survey of some of the best-known medical treatises of the period reveals that the female body is represented only when the reproductive organs are in question; for the rest of the body, the male serves as the example for both sexes.10 It is intriguing that, while images of the male body come to dominate anatomical works in the second half of the sixteenth century, and the first half of the seventeenth, images of the female body and the feminized male body invade the alchemical realm. These bodies are presented alongside others that are strikingly different from the Vesalian male norm: the hydropic man, the figure of Saturn as an amputee from Maier’s Symbola Aureae Mensae,11 the double-headed hermaphroditic rebis. The alchemical corpus becomes a significant repository for images of various bodily differences, and a means of contemplating the various potential significances of those differences.

By means of scrutiny of some of these images, I hope to nuance some current arguments concerning the advent of an idealizing form of normalcy, for which I discern roots in early modern medical manuals. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the new science of statistics is put to use defining the normal human body, and eventually enforcing an idealizing norm. At the same time, alchemy falls by the wayside, considered an outdated mode of scientific inquiry. In recent criticism, the critique of enforcement of idealizing norms relative to the human body has been focused primarily on modern practices. As Lennard Davis points out in his essay on “Constructing Normalcy,” the modern notion of the “average man” – a notion that both fueled and was fueled by the mania for statistics – evolved into an idealizing notion of normalcy. The eugenicist Sir Francis Galton (1822–1911) transformed the interpretation of statistics from perceiving the average as normal to promoting above-average traits as normal:

In an “error curve” the extremes of the curve are the most mistaken in accuracy. But if one is looking at human traits, then the extremes, particularly what Galton saw as positive extremes – tallness, high intelligence, ambitiousness, strength, fertility – would have to be seen as errors. Rather than “errors,” Galton wanted to think of the extremes as distributions of a trait.

Davis describes revisions Galton made to his system in order to privilege these traits (height, intelligence, ambitiousness, strength, fertility), which he deemed superior. He goes on to discuss the implications of these revisions:

What these revisions by Galton signify is an attempt to redefine the concept of the “ideal” in relation to the general population. First, the application of the idea of a norm to the human body creates the idea of deviance or a “deviant” body. Second, the idea of a norm pushes the normal variation of the body through a stricter template guiding the way the body “should” be. Third, the revision of the “normal curve of distribution” into quartiles, ranked in order, and so on, creates a new kind of “ideal.” This statistical ideal is unlike the classical ideal which contains no imperative to be the ideal. The new ideal of ranked order is powered by the imperative of the norm, and then is supplemented by the notion of progress, human perfectibility, and the elimination of deviance, to create a dominating, hegemonic vision of what the human body should be.12

This vision is put into action first by the eugenicists, who wish first to eliminate those who deviate from the norm, both the “feeble bodied” and the “feeble minded,” by means of sterilization, incarceration, and even by means of what they call euthanasia, practiced massively by the Nazis in the 1930’s against the first victims of the Holocaust, the disabled.

While Davis is correct in observing particular modern means of marginalizing physical difference, his idealization of the past does not hold up under scrutiny of that past. Early modern anatomical treatises can be considered possible precursors for our own understanding of the norm, and some alchemical works can be seen as alternatives to normalizing depictions of the human body. As Davis suggests, there are political and social implications to our Enlightenment ancestors’ choice of statistic-driven ways of representing the body over other possibilities. In this regard, the argument in this essay differs from that of William R. Newman, in his book, Promethean Ambitions.13 While alchemical belief in the perfectibility of nature and of human nature may have played a role in the rise of idealizations of the norm, how that perfectibility manifests itself in alchemical treatises is radically different from the notion of perfection represented in medical manuals.

In Western Europe, the practice of annual dissections of a human cadaver began sometime in the course of the fourteenth century.14 Some of these exercises were deemed illicit, and students prosecuted for sacrilege; others were permitted by university statutes, for example those of Montpellier in 1340. By the end of the fifteenth century, the annual dissection was a regular practice in medical faculties, and there is some evidence that it became quite widespread. Leonardo da Vinci began performing a number of dissections and making anatomical drawings based on them around 1487. His representations, while often mechanistic, are relatively realistic. But these images were not widely available.15

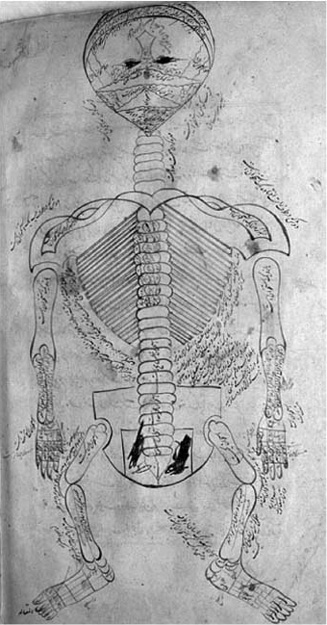

Before the advent of what we would consider to be relatively accurate anatomical representations, medieval medicine was dominated by schematic drawings of the internal workings of the body, known as the “Five-Figure” series (because they consisted of five figures, representing the muscles, the skeletal system, the veins, the arteries, and the nervous system). These figures were often joined by a sixth, an image of a pregnant woman. These seem to have arrived in Europe via Persian manuscripts, but resemble images from Chinese and Indian medical treatises. These images are based on other images, rather than on direct observation of the human body. They are quite schematic, and not useful for surgeons in particular who might need a more accurate understanding of the human body.16

One might think that once dissection of the human body had become a fairly regular feature of medical training, representations of the body would have more closely resembled actual, even ordinary, human bodies.17 What happens is more complex, and related to the discovery of classical sculptures representing gods from the Greek and Roman pantheon. The most widely disseminated anatomical images in early modern Europe were those from Vesalius’s treatise, De humani corporis fabrica. These images dominated early modern medical treatises for at least a century, republished and imitated in other works such as Caspar Bauhin’s treatise on human anatomy, cleverly titled De corporis humani fabrica, thus avoiding accusations of overt plagiarism while capitalizing on the popularity of Vesalius’s work.18 Bauhin’s version was published in 1590 in much smaller format and on cheaper paper, and thus was suitable for use by medical students. Vesalius’s original edition was a prohibitively expensive book, more intended for rich patrons than for medical students, and thus not as widely available as the works of his imitators. Bauhin’s work itself was anthologized with treatises by other authors, and so was disseminated throughout Europe;19 and his work is only one example of the many medical treatises appropriating the images in Vesalius’s work. As we shall see, these images were also disseminated and imitated in a far wider range of texts than merely medical treatises.20

Fig. 3.1 The Skeletal System: An Image from a Five-Figure Series, from Mansur ibn Ilyas, Tasrih-I badan-I insan (Anatomy of the Human Body). Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

But where did these images come from? In an attempt to market his work, Vesalius hired artists to create the images, among them Johannes Stephanus of Calcar, a student of Titian’s.21 Stephanus imitated classical sculpture, such as the Belvedere Torso, in his depiction of the human body. The Apollo Belvedere, a Hellenistic or Roman copy of a fourth century B.C.E. bronze sculpture, rediscovered in the late fifteenth century,22 was also a popular model for anatomical illustrations, as the “Flayed Man” from Juan Valverde de Amusco’s Anatomia del corpo humano,23 itself imitated in other treatises, demonstrates. The Apollo Belvedere’s posture and musculature are also echoed in the famous Vesalius/Stephanus image of the “Muscle Man.” Valverde de Amusco’s work also appropriated this and other Vesalian images.

The Vesalian “Muscle Man” is in fact echoed fairly widely in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Theodor de Bry used it extensively in his America series, an illustrated edition of every single account he could gather of the discovery, exploration, and conquest of the Western Hemisphere by Western Europeans. His idealizing portrait of a Virginian (that is, Native American) king echoes the proportions and the posture of the “Muscle Man,” while adding some more mannerist-style musculature (see figure 6 in Sean Teuton’s essay). This image is from the first part of the series, published in 1590, also known as the Admiranda narratio, and based on Thomas Hariot’s accounts of the English encounters with the natives of Virginia.24 The fact that de Bry intended to present the more welcoming Virginians as ideal in body as well as behavior, particularly compared to their cannibalistic Brazilian counterparts, who are portrayed as having shorter limbs and longer torsos, as well as rounder heads, indicates that this classicizing representation of the body was seen as an ideal (see Teuton, figure 7).25 In some other, similar, images, the Virginians are even overtly compared to predecessors of the early modern Europeans, particularly the Picts, who tattooed themselves much as some Native Americans did.

Fig. 3.2 Apollo Belvedere, Hendrik Goltzius, copy by Herman Adolfz, from Antique Statues in Rome, ca. 1592, dated 1617. Courtesy of the Bryn Mawr College Collections.

Fig. 3.3 The Flayed Man, from Juan Valverde de Amusco, Anatomia del corpo humano (Rome: Salamanca and Lafrery, 1560), plate 1, vol. 2. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Fig. 3.4 “The Muscle Man” (“Tertia musculorum tabula”) from Andreas Vesalius, De corporis humani fabrica (Basel: I Oporini, 1543). Courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Not surprisingly, given that the de Bry family imitated Vesalius both in their medical illustrations for Bauhin’s anatomical treatises and in their America project, they also imitated the De humani corporis fabrica in alchemical illustrations. Probably the best-known example of an illustrated alchemical treatise is Michael Maier’s Atalanta fugiens (Fleeing Atalanta), first published at Oppenheim in 1617 by the de Bry family and illustrated by engravings done by a de Bry son-in-law, Matthäus Merian. Maier himself, born in 1568, was no marginal figure, but was the court physician to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, a noted patron of alchemy and of the arts.26 The fact that Maier was court physician recalls that alchemy was more than the search for ways to turn lead into gold. It was also known as “chemical medicine,” and this branch of the art consisted of seeking out medicines, made out of chemical compounds, herbs, and other ingredients, to restore the body’s equilibrium and thus its health. For Maier, alchemy also had a spiritual significance, based on the belief that contemplation of certain ideas or images would improve the individual’s understanding of the universe and of his or her place in it. This alchemical regime, playing as it does with gender and other corporeal norms, often seems to present an alternative to the predominant regimes organized by Church and State, most particularly the theological as well as legal privileging of the masculine over the feminine. These three branches of alchemy, the search to create higher forms of materials from lower ones, to find medicines to cure the body of illness, and to improve one’s understanding through contemplation of complex ideas and images, were intertwined in many alchemical works of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries., although the Atalanta fugiens seems to privilege the philosophical.

The Atalanta is an odd work for modern readers unfamiliar with alchemical emblem-books, consisting of a series of 50 emblems representing stages of the alchemical process as symbolic figures, with a motto, an epigram, and a long explanatory discussion, all in Latin but also translated into German. The further complication of this work is that all 50 epigrams are set to music (fugues, to be precise, in keeping with the title of the work). The reader was apparently expected to sing the epigram while contemplating the emblem; this means that the viewing of the emblem was supposed to be more than a casual glance. This methodology resembles some early modern meditative practices more than it does modern scientific methods of experimentation, thus suggesting the possibility not only of transformation of materials external to the practitioner, but also the inducing of a state of mind within the practitioner. That being said, I would not want to follow a Jungian approach to the texts; rather, I would hope to reinstate these works in their original context, that is to say, a period when meditation was becoming a significant part of religious practice (one need only think of the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola). As strange as all this is, this work was popular enough to be published in 1617 and again in 1618, and yet again in 1687 and 1708.27 In this reading of Maier, I depart from Allen and Hubbs by placing Maier in the context of the scientific and theological discourses of his time. By means of his repeated invocation of the four elements, which are omnipresent in the Atalanta, as well as the precise way in which this invocation is presented, Maier demonstrates a connection to Hippocratic, as well as Aristotelian traditions, in which fire, air, water, earth correspond to hot, dry, wet, and cold, as well as the humors of yellow bile, blood, phlegm, and black bile.28 In this context, the balance of the four elements, with air and fire representing the masculine and earth and water the feminine, is crucial rather than the mastery and effacement of some elements by others. The constant rebalancing of the elements throughout the process explains the repetitive nature of the imagery in many alchemical treatises. For example, in the Atalanta, the stage of conjunction is evoked repeatedly in the images of the marriage of brother and sister (emblem IV), of Sol and Luna (emblem XXXIV), of Mercury and Venus (emblem XXXVIII), as well as in the image of the alchemical rebis (emblems XXXIII and XXXVIII). It should also be noted that the elements are often presented as ambiguous or mixed in nature; thus, the masculine Wind is presented as a pregnant Man, the feminine Water is presented as a hydropic man, rather than a woman, and the rebis, associated with Fire, is hermaphroditic.

The bodies themselves also call for some contemplation, disrupting as they do, and did in the sixteenth century, our expectations of bodily normalcy as evoked by the images in Vesalius’s treatise. In this, we can see the idealized body, represented in much of what Renaissance artists knew of classical sculpture, becoming the norm that Lennard Davis discerns in modern culture. But alchemy represents bodies that are somehow strange, and it could be argued that alchemical illustrations normalize strangeness by offering it for contemplation, as part of the alchemical process. So, Vesalius’s Muscle Man becomes the Wind, the first emblem in the Atalanta. His hair and his hands designate him as the airy element, even as he seems to dissolve into that element, and the child in his belly indicates his centrality to the generative process. The positioning of his feet, the aspect of this figure that most resembles the Apollo Belvedere, suggests the possibility of flight or lightness, as the heels of both feet are lifted slightly off of the ground. The arms, also echoing the placement of the arms in the Apollo Belvedere, end in gusts of wind, represented by spiraling clouds. The classical sculpture, with its emphasis on lightness and movement, serves as the perfect model for an image of the Wind as a semi-divine, elemental force in the production of the Philosopher’s Stone.

Fig. 3.5 “The Wind Carries it in His Belly,” Emblem 1, from Michael Maier, Atalanta fugiens (Oppenheim: Gallery, 1617; reprinted, Frankfurt, 1687). Courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

The motto that accompanies the emblem, “The wind carried it in its belly,” is a line from the earliest extant alchemical treatise, the Emerald Table (or Tabula Smaragdina), probably dating from around the fourth century AD. This work describes the Philosopher’s Stone, the goal of every alchemical process, as the child of the Sun and the Moon, borne by the Wind and nourished by the Earth.29 All aspects of nature are necessary to the production of the stone, just as an understanding of the various mathematical disciplines – arithmetic, music (considered a mathematical discipline in early modern Europe), geometry, and astronomy – perfects the philosopher’s understanding of the world. At any rate, this is the lesson Maier offers in his commentary on the image.

In his depiction of the Wind, Matthäus Merian has only departed slightly from the classical ideal, but the pregnant man, a popular concept in early modern culture,30 twists the Vesalian model in a new direction. The Wind leads logically to the nurturing Earth, as the Atalanta evokes the Aristotelian elemental foundations of the alchemical process: earth, air, water, and fire. This Earth is not at all classical in form; the contrast with the Wind is striking. Her form oscillates between emphasis on the human body as a world, and the world as a human body: note that one arm is human, and seemingly independent from the globe of the body; the other arm arises from the globe itself. Her feet are more solidly on the ground, and the composition in the foreground of the engraving emphasizes downward movement or grounding. Nonetheless, traces of the depiction of the Wind remain in the background, in the form of clouds and upwardly sweeping mountains. The third emblem introduces the elements of water and fire, with the fire and smoke sweeping upwards, and echoing the Wind in the first emblem with its billowing clouds, while the water pours downwards, thus echoing the movement in the second emblem. While, by the time of the Renaissance, earth and water came to be associated with the feminine and fire with the masculine, all of these elements needed to be in balance, according to Hippocratic medicine, newly revived in the sixteenth century.31 It is significant that all of the elements, including Earth, are crucial to the alchemical process, which does not consist of a shedding of the lower elements, earth and water, themselves linked to the feminine in most other philosophical discussions of the time. These emblems also suggest that the Philosopher’s work should reflect the functioning of nature, not dominate or eliminate it.

Fig. 3.6 “The Earth is its Nurse,” Emblem 2, from Michael Maier, Atalanta fugiens. Courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

The emblems of the Atalanta also reflect a play with categories or boundaries, particularly those involving the human body. While the first emblem underscores the dissolution of the human body into its surroundings (or, conversely, the coalescence of the wind into a human form), the boundaries dissolved in the second emblem are between the human and the animal, as wolves and goats nurture human babies (or divine, as in the tales of Romulus and Remus, and of Zeus/Jupiter, himself nurtured by a goat), and between the human microcosm and the natural macrocosm. The effacement and reestablishment of boundaries is a common theme in alchemical treatises, and so these works offer images of incest (brother/sister in the Atalanta, to symbolize Sol and Luna, Apollo and Diana, gold and silver; and mother/son in the Rosarium philosophorum), and of effeminacy, as in the case of the hydropic man (emblem XIII; see Teuton, figure 2), whose bloated body resembles that of a pregnant woman. This emblem also adds the element of water to the air/earth mix, as the hydropic man is both washed – that is bathed in water or dissolved in it, just as a chemical substance would be – and purged of his own disease, represented by excess fluid. This sort of paradox of adding and removal of elements is not uncommon in the alchemical process. The elements, earth, water, air, and fire, all dominate the emblems and are represented as the very bases of existence as well as the catalysts necessary for the alchemical process. The elements themselves are still gendered, with the earth represented as female (emblem II), water represented by an effeminate man (emblem XIII), air as masculine (emblem I), and fire most closely associated with the hermaphroditic rebis (emblem XXXIII). Thus, representations of the effacement and redrawing of boundaries in this treatise often involve an interplay between the masculine and the feminine.

Most striking among these representations of the human body is the rebis, a central figure in the alchemical process, representing the stage of conjunction of sulphur (Venus) and mercury, considered opposing elements but also the bases of existence in alchemical treatises of the early modern period. This conjunction of opposites leads to the production of the Philosopher’s Stone, which symbolizes physical and spiritual perfection. The rebis is always represented with two heads, one male (generally with short hair) and one female (generally with long hair). Merian is careful to represent his rebis as hermaphroditic, that is, as having two sets of genitalia, one male and one female. This representation, in keeping with commentaries on the stage of conjunction in a number of alchemical treatises, suggests that while the elements are fused, they also retain their individual properties. This contrasts with the Ovidian myth of the hermaphrodite, in which the female Salmacis is subsumed into the male Hermaphroditus, who is weakened by her presence but retains his essential, and essentially masculine, identity.32 Ovid’s version is in line with the Aristotelian notions of gender, which present the female as a defective or lacking male.33

Fig. 3.7 The Hermaphrodite in the Stage of Putrefaction or Dissolution, Emblem 33 of the Atalanta fugiens, Michael Maier. Courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

The alchemical rebis defies this vision of gender, by offering two distinct forms in one body. If the feminine aspect were merely a defective or lacking version of the masculine aspect, it would disappear into the masculine form, as Salmacis does into Hermaphroditus. The fact that the feminine aspect remains evident in the rebis, underscored both by the presence of female genitalia and one female breast, as well as by long hair, suggests that this figure is the union of two truly distinct forms, which retain that distinction even when joined. In this interplay between distinction and effacement of difference, most frequently resulting in a union of opposites that nonetheless allows those opposites to retain their distinct identities, Maier extends the representation of gender roles to a broader array of questions suggested by the imagery of the Atalanta, such as codependence of species (emblem II) and the problematic power and vulnerability of the king (emblems XXIV, XXVIII, XXXI, and XLVIII). The symbolic significance of the hermaphroditic rebis becomes quite capacious, as the ambiguity of the figure requires interpretation. In alchemical tradition, this hermaphroditic body is the ideal form. The Philosopher’s Stone is often described as a hermaphrodite, as is the original God that created the universe.

I would like to argue that this anomalous body offers a potent political message, one echoed by Montaigne in a somewhat different context, his brief essay “On a Monstrous Child,” the thirtieth essay in the second volume. After describing how this child, with a parasitic twin complete except for its head joined to him at the abdomen, is shown by relatives to anyone who will pay, he gives an interpretation: “This double body and its different parts, joined with one single head, could well provide a favorable prognostication to the King, that he might maintain under the union created by his laws these diverse parts and pieces of our state.”34 Montaigne is not overly optimistic about this possibility, but his vision of the union of disparate parts is not so distant from the alchemical notion of conjunction, where difference is joined together, but not assimilated into a uniform whole. He also argues, echoing St. Augustine’s discussion of monsters in The City of God: “That which we call monsters are not such to God, who sees in the immensity of his creation the infinity of forms that he has included.”35 While Montaigne’s “Monstrous Child” is the physical reverse of the alchemical rebis, being two bodies with one head, the lessons evoked by the two bear some resemblance.

What Montaigne’s text makes clear is that, well before Hobbes, the body as metaphor for the body politic is not only current,36 but already being turned in different directions by the use of unusual, disabled, or diseased bodies as metaphors for dysfunctional states. This problematic view of the body is evoked by Théodore Agrippa d’Aubigné in his epic on the Wars of Religion in France, Les Tragiques. He compares a France torn by civil war to a giant body afflicted by humoral imbalances and hydropsy.37 While d’Aubigné more conventionally compares the dysfunctional state to a diseased body, Montaigne suggests that the unusual body of the “monstrous child” sends a different message: that of the potential harmony of the disparate factions in France at the end of the sixteenth century. In this context, the hermaphroditic rebis suggests a larger political arena for alchemical modes of thinking.

The lessons of Montaigne’s monstrous child and of the alchemical rebis also bear some resemblance to those offered by Alice Dreger relative to conjoined twins. Western belief in the overriding importance of individuality may seem to drive the urge to surgically separate conjoined twins, as Dreger argues, but this urge also arises from the social importance of conforming to idealizing norms of corporeality, from a drive to efface individuals who are too different, too individual, as Davis has suggested in his essay on “Constructing Normalcy,” cited above. This drive to create an individual who conforms to our view of bodily norms causes surgeons to impose often dangerous procedures on their conjoined twin patients, as well as on other individuals with “extraordinary bodies.” Today, as in the early modern period, we still have difficulty accepting certain forms of difference. Yet conjoined twins often seem quite happy as they are. They almost always have two distinct personalities, with very different interests and impulses. This was true, for example, of Chang and Eng, the famous “Siamese twins” from the nineteenth century. Still, they learn from birth to compromise and to function as one, in order to survive, but ideally they do so without sacrificing their individuality, as present-day conjoined activists Abigail and Brittany Hensel do: “How do conjoined twins cope with their attachments? Like the rest of us who live in commitment with others, they work out explicit and tacit agreements about day-to-day living.”38 Yet, Dreger adds, “conjoinment does not automatically negate individual development and expression, any more than other forms of profound human relations do. Indeed, differing personalities and tastes are the rule among conjoined twins with two conscious heads.” The implications of this dual identity in one body, first suggested by Montaigne, are significant: in the relations we form and that are necessary to our existence, physical, familial, social, or political, it is possible to function as a unit without sacrificing difference. But this can only happen in a social and political context that embraces difference, rather than attempting to eliminate it, whether by means of eugenics or other means of limiting the lives or reshaping the bodies or minds of those who do not match up to our expectations. Pronounced bodily differences are a test of our capacity to accept difference; we are still in the process of working out how to include individuals with these differences in our societies. As Montaigne suggests, our capacity to embrace and comprehend physical difference has implications for a larger social arena, as a reader aware of Inquisition modes of torturing heretics would recognize when gazing on Maier’s emblem of a rebis being calcinated by means of “mort à petit feu,” or death by slow fire, a form of torture used both on heretics and recalcitrant natives of the Western hemisphere in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Alchemy, now rehabilitated as a proto-chemistry, a discipline without which chemistry might never have existed, by scholars such as Allen Debus,39 William Newman, and Lawrence Principe, was mocked and discredited by Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment thinkers, particularly academics, and particularly those in the discipline of medicine. One need only read the opening pages of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to see how far it had fallen out of grace even in the realm of popular culture by the early nineteenth century. Victor Frankenstein learns from his professors that his study of Cornelius Agrippa, Albertus Magnus, and Paracelsus, the greatest of alchemists, has been an utter waste of time: “Every minute … every instant that you have wasted on those books is utterly and entirely lost.”40 Alchemy was regarded as a monstrous practice. Yet it had been one of the few pursuits open to women, who were excluded from university studies and thus from the academic practices of science, as well as from the medical profession, and, increasingly, from midwifery. From the scholarship of Jayne Archer and Penny Bayer,41 as well as many others, we know that quite a few women practiced alchemy both as a science, performing early versions of chemistry experiments, and as a philosophy, discussing what it meant for their place in the world. Thus, alchemy became a space for difference in a number of ways. Relative to women practitioners, it grants them a field in which to pursue scientific and philosophical inquiries, at a time when they remain shut out of official academic and scholarly circles, and as they are being excluded from domains of inquiry and practice formerly permitted to them, such as management of childbirth and other reproductive issues.

As has been mentioned above, alchemy had been for many centuries considered both a science and a philosophy of life, a process of perfecting nature and the self. While some alchemical treatises give precise “recipes” to follow for various chemical experiments, many, Michael Maier’s Atalanta fugiens among them, were more like meditative exercises linked to the alchemical symbolism used in more practical manuals. What then, were individuals meditating on? One of the fundamental principles of alchemy is that both masculine and feminine elements are necessary for the perfection of any aspect of nature or man; another, that perfection arises out of imperfection and irreducible difference, not out of elimination of that imperfection or that difference. The constant representation of odd bodies in alchemical treatises – and Michael Maier’s other treatises, as well as the works of other alchemists, foreground corporeal difference repeatedly – goes against the grain of idealizing and masculinizing representations of the body in medical works. It should be recognized that this privileging of radical bodily difference, including monstrosity (in the sense of cross-species hybrids), disability (in the sense of bodies that depart from an idealizing norm), and transgenderism all associate the feminine with the “monstrous” in alchemical lore. The difference from mainstream medical treatises is that the feminine and the monstrous are not judged to be inferior or defective, but valued as part of an ongoing process of perfection. Nonetheless, when alchemy is rejected as an outmoded and fantastical enterprise, not to be considered a science, the association of the monstrous and the feminine becomes grounds for denigration of the latter, rather than for reconsideration of what monstrosity might mean.

As Lennard Davis points out, the rationalizing impulses of the Enlightenment provided the context for the development of the science of statistics, and the perfection of means for measuring and categorizing human bodies. How differently things might have turned out if alchemy, more imaginative, visual, and creative than many of the scientific disciplines devised by the Enlightenment, more inclusive of women as practitioners, and more open to diverse bodily forms, had not been discredited by the moderns. The eighteenth century saw the first clear elaborations of the concept of human rights in Europe, but the evolution of this concept in the West has often led to the exclusion from these rights of groups who don’t fit into an idealized norm: women, openly gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgendered individuals, minorities, and the disabled. A number of modern medical practices, such as eugenics, forced sterilization, institutionalization, selective abortion, and aesthetic surgery, seem to have favored uniformity and elimination of differences; they go hand in hand with political and social systems that have privileged relatively narrow subgroups of people who fit a particular aesthetic ideal – one inspired at least in part by classical statuary such as the Apollo Belvedere. Alchemy offered the possibility of an exercise in familiarizing the strange, of embracing, rather than eliminating, difference. Let us embrace this aspect of alchemical thought as we face new challenges and an increasingly global culture.

1 Lawrence M. Principe and William R. Newman, “Some Problems with the Historiography of Alchemy,” in Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe, William R. Newman and Anthony Grafton, eds. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), pp. 385–431.

2 Hereward Tilton, The Quest for the Phoenix: Spiritual Alchemy and Rosicrucianism in the Work of Count Michael Maier (1569–1622). Christoph Markschies and Gerhard Mueller, eds. Arbeiten zur Kirchesgeschichte 88 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003), p. 14.

3 Kathleen P. Long, “Lyric Hermaphrodites,” in Hermaphrodites in Renaissance Europe (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), p. 163.

4 Sally G. Allen and Joanna Hubbs, “Outrunning Atalanta: Feminine Destiny in Alchemical Transmutation,” Signs 6/2 (1980): 213.

5 Long, Hermaphrodites, pp. 119–23.

6 Didier Kahn, Alchimie et paracelsisme en France (1567–1625) (Geneva: Droz, 2007), p. 7: “Définir l’alchimie n’est pas chose aisée. Cette discipline mouvante a toujours su s’adapter à tous les contextes, se fondre dans le milieu ambiant, se mêler aux doctrines ou aux sciences les plus proches. Il est en fin de compte plus facile de dire ce qu’elle n’est pas.” (“It is not an easy thing to define alchemy. This mutable discipline has always known how to adapt itself to every context, to melt into the surrounding environment, to mix with the doctrines and forms of knowledge closest to it. It is, finally, easier to say what it is not.”)

7 Joachim Telle, ed., Rosarium Philosophorum: Ein Alchemisches Florilegium des Spätmittelalters, Faksimile des illustrierten Erstausgabe Frankfurt 1550 (Weinheim: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft, 1992).

8 Z3v (p. 182 in the facsimile edition of the Rosarium).

9 Lambsprinck, De Lapide Philosophico Libellis (Frankfurt: Luca Jennis, 1625), emblem 15.

10 This is true for Jacopo Berengario da Carpi’s Isagogae breves, perlucidae ac uberrimae in anatomiam humani corporis (Bologna: Benedictus Hector, 1523); for Charles Estienne’s De dissection partium corporis humani libri tres (Paris: Simon Colinaeus, 1545); for Juan Valverde de Amusco’s Anatomia de corpo humano (Rome: Ant. Salamanca and Antonio Lafrery, 1560); and for Andreas Vesalius’s own De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basel: Joannes Oporinus, 1543). The images from all of these treatises are easily available for scrutiny at the National Library of Medicine website, Historical Anatomies Online: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/browse.html

11 Symbola Aureae Mensae Duodecim Nationum (Frankfurt: Luca Jennis, 1617).

12 Lennard Davis, “Constructing Normalcy: The Bell Curve, the Novel, and the Invention of the Disabled Body in the Nineteenth Century,” The Disability Studies Reader (New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 8.

13 William R. Newman, Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004).

14 Nancy G. Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990), p. 86.

15 Siraisi, p. 97.

16 Siraisi, pp. 92–3.

17 Siraisi, p. 94.

18 Caspar Bauhin, De corporis humani fabrica… (Basel: Sebastianum Henricpetri, 1590). This and later versions of Bauhin’s anatomical treatise were illustrated with imitations of Vesalius’s work, done by Theodor de Bry.

19 For example, in the Mikrokosmographia: a description of the body of man: together with the controversies and figures thereto belonging / collected and translated out of all the best authors of anatomy, especially out of Gaspar Bauhinus and Andreáas Laurentius, Helkiah Crooke, ed. (London: printed by R.C. and are to be sold by Iohn Clarke.., 1651).

20 For a brief overview of anatomical treatises in the sixteenth century, see Andrew Wear, “Early Modern Europe, 1500–1700,” in The Western Medical Tradition, 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 280–81. For another take on Renaissance anatomy, see Jonathan Sawday, “The Renaissance Body,” in The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 16–38. See also Katharine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2006).

21 A recent article by Patricia Simons and Monique Kornell, “Annibal Caro’s After-Dinner Speech (1536) and the Question of Titian as Vesalius’s Illustrator,” Renaissance Quarterly, 61/4 (2008): 1069–97, summarizes much of the scholarship on the subject, as well as putting to rest the question of Titian’s involvement in the project. The fact that Titian’s name has even been invoked relative to the De humani corporis… underscores the symbiotic nature of art and anatomy in this period.

22 Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969), p. 103.

23 Juan Valverde de Amusco, Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano… (Rome: Salamanca and Lafrery, 1556). Republished as Anatomia del corpo humano (Rome: Salamanca and Lafrery, 1560). Images from this text are available on the website run by the National Library of Medicine: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/valverde_bio.html

24 Theodor de Bry, ed. and illus., Admiranda narration, fida tamen, de commodis et incolarum ritibus Virginiae…Anglico scripta sermone à Thoma Hariot… (Frankfurt: J. Wechel, 1590).

25 Theodor de Bry, ed. and illus., America tertia pars memorabilem provinciae Brasiliae historiam continens… (Frankfurt: M. Becker, 1605).

26 For more background on Maier, see Hereward Tilton, cited above, and Bruce T. Moran, The alchemical world of the German court: occult philosophy and chemical medicine in the circle of Moritz of Hessen (1572–1632) (Stuttgart: F. Steiner, 1991).

27 See H.M.E. de Jong, Michael Maier’s Atalanta fugiens: Sources of an Alchemical Book of Emblems (York Beach, ME: Nicolas-Hays, Inc., 2002; reprinted from the Leiden edition, Brill, 1969), p. 5.

28 Vivian Nutton, “Medicine in the Greek World, 800–50 BC,” in Lawrence I. Conrad, et. al. The Western Medical Tradition: 800 B.C. to A.D. 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 23–5.

29 De Jong, p. 55.

30 See, for example, Sherry Velasco, Male Delivery: Reproduction, Effeminacy, and Pregnant Men in Early Modern Spain (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2006).

31 The revival of Hippocrates is linked to representations of gender by Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park in their article, “The Hermaphrodite and the Orders of Nature: Sexual Ambiguity in Early Modern France,” Gay and Lesbian Quarterly 1 (1995): 419–38.

32 Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso), Metamorphoses, ed. William S. Anderson (Leipzig: Teubner, 1985) bk. 4, l.383.

33 Aristotle, Generation of Animals, in The Complete Works of Aristotle, Jonathan Barnes, ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series, 1984) vol. 1, p. 1113 (716b 5).

34 Michel de Montaigne, Essais, Pierre Villey, ed. (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1978) vol. 1, p. 713: “Ce double corps et ces membres divers, se rapportans à une seule teste, pourroient bien fournir de favorable prognostique au Roy de maintenir sous l’union de ses loix ces pars et pieces diverses de nostre estat.”

35 “Ce que nous appellons monstres, ne le sont pas à Dieu, qui voit en l’immensité de son ouvrage l’infinité des formes qu’il y a comprinses.”

36 For a critique of Hobbes’s corporeal metaphors, see Moira Gatens, Imaginary Bodies: Ethics, Power, and Corporeality (London: Routledge, 1996), pp. 21–8.

37 “Ce vieil corps tout infect, plein de sa discrasie,/ Hydropique…” (“This old body, completely infected and full of humoral imbalances, hydropic…”), ll. 146–7, from “Misères,” in Les Tragiques, from the Oeuvres, H. Weber, ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1969), p. 24.

38 Alice Dreger, One of Us: Conjoined Twins and the Future of Normal (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), pp. 38–41.

39 Allen Debus, The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (New York: Science History Publications). This book was enormously influential in its redirection of modern understanding of the place of alchemy in the history of science. See also Chemistry, alchemy and the new philosophy, 1550–1700: studies in the history of science and medicine (New York: Variorum Reprints, 1987). For Lawrence Principe, see The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and his Alchemical Quest (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998). William Newman’s Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature is a superb study of the relationship between early modern alchemy and modern scientific endeavors. A readable and cogent introduction to alchemy and early modern science is Bruce Moran’s Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005). In terms of the larger social importance of alchemy, Tara Nummedal’s recent study, Alchemy and Authority in the Holy Roman Empire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007) is the most comprehensive study to date.

40 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: W.W. Norton, 1995), p. 26.

41 See the essays in this volume, as well as Penny Bayer’s essays, “Jeanne du Port, alchemist daughter of Joseph du Chesne,” Rosenholmeren: Notiitser og Meddelelser fra Renaessancestudier ved Aarhus Universitet, 6/7, (October 1999): 1–4, “Lady Margaret Clifford’s Alchemical Receipt Book and the John Dee Circle,” Ambix (November 2005): 271–84, and “From Kitchen Hearth to Learned Paracelsianism: Women’s Alchemical Activities in the Renaissance,”, in “Mystical Metal of Gold”: Essays on Alchemy and Renaissance Culture, Stanton J. Linden, ed. (Brooklyn, NY: AMS Press, 2007), among other pieces. See also Jayne Archer, “Women and Alchemy in Early Modern England,” unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2000.