The art of effective decision making

There is a time when we must firmly choose the course we will follow, or the relentless drift of events will make the decision.

Franklin D Roosevelt

In decision making there is a classic five-step approach that you should find extremely helpful. That does not mean you should follow it blindly in all situations. It is a fairly natural sequence of thought, however, and so even without the formal framework you would tend to follow this mental path. The advantage of making it conscious is that it is easier to be swiftly aware when a step is missing or – more probably – has been performed without understanding or intention.

It is useful to think of the five steps on page 19 as five notes of music. Logically they should be played in strict sequence. But the mind darts about. The notes can be combined in different sequences and mental chords. Thinking is not a tidy process, but it should be done with a sense of order.

Remember that we are not talking here about just big decisions, for there’s a lot more to running a business than making one life-or-death decision. Indeed no decision, no matter how big, is any more than a small fraction of the total outcome. Yes, some decisions are much bigger than others, and some are forks in the road. But it is really more the case that a much larger number of small decisions have a cumulative result. By hindsight we can usually identify those few pivotal decisions, but it is really the stream of smaller decisions over time, made and executed with a craftsman’s skill, that yields great outcomes.

Do you know what you are trying to achieve? You do need to be clear – or as clear as possible – about where you want to get to. Otherwise the whole process of decision making is obscured in a cloud. As the proverb says, If you do not know what port you are heading for, any wind is the right wind.

If you are in doubt about your aim, try writing it down. Leave it for a day or two, if time allows, and then look at it again. You may be able to see at once how it can be sharpened or focused.

The next skill is concerned with collecting and sifting relevant information. Some of it will be immediately apparent, but other data may be missing. It is a good principle not to make decisions in the absence of critically important information that is not immediately to hand, provided that a planned delay is acceptable.

Remember the distinction between available and relevant information. One classic mistake is to look at the broad decision and then turn to the information we have that will help us decide. Some thinkers do not, however, look at the information at their disposal and ask themselves, ‘Is this relevant?’ Instead they wonder, ‘How can I use it?’ They are confusing two kinds of information – as is illustrated on page 20.

Figure 2.1 The classic approach to decision making

Life would be much simpler if you could just use the information at your disposal, rather than that which you really need to make the decision! So often quantities of data are advanced – there are acres of it on the internet – that merely add bulk to, say, a management report without giving its recommendations any additional (metaphorical) weight.

The rapid growth of methods of communication such as faxes, voice mail, e-mail, junk mail and the internet has now contributed to a new disease: Information Overload Syndrome. A recent international survey of 1,300 managers listed the new disease’s symptoms, which included a feeling of inability to cope with the incoming data as it piles up, resulting sometimes in mental stress and even physical illness requiring time off work. The survey found that such overload is a growing problem among managers – almost all of whom expect it to become worse.

Figure 2.2 Information categories

Executives and their juniors say they are caught in a dilemma: everyone tells them that they should have more information so they can make better decisions, but the proliferation of sources makes it impossible to keep abreast of the data.

The growth of information has been relentless. The New York Times contains as much distinct information every day as the average seventeenth-century person encountered in a lifetime. No wonder that half the managers surveyed complained of information overload, partly caused by enormous amounts of unsolicited information. The same proportion also expected the incredible expansion of the internet to intensify the problem year-on-year. To avoid succumbing to Information Overload Syndrome you need all the skills described in this book!

Suppose that the overlap between information required and information available is not sufficient: what do you do? Obviously you set about obtaining more of the information required category. But getting information or – to use a grander description – doing research incurs costs in time and money. Your organisation may not be in the business of making profits, but it certainly has to be businesslike when it comes to containing costs.

What the graph below suggests is that you usually acquire a great deal of relevant information in a relatively short time and, possibly, at a relatively low cost in money. But the line soon curves towards a plateau. You will find yourself spending more and more time to discover less and less relevant information. For example, if you and I sat next to each other at a dinner, I should learn all the really important things about you in the first half hour. The longer we talked, the smaller the increments of knowledge about you would become. After three hours I should be down to discussing relatively fine details.

Figure 2.3 The time/information curve

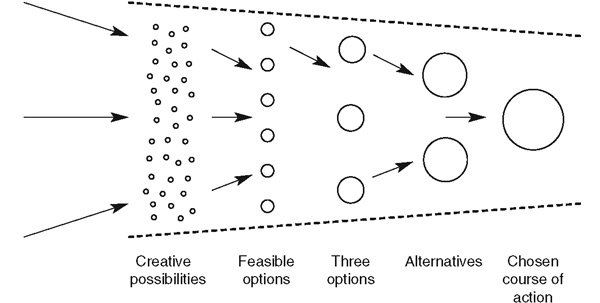

Notice the word options rather than alternatives. An alternative is literally one of two courses open. Decision makers who lack skill tend to jump far too quickly to the either–or alternatives. They do not give enough time and mental energy to generating at least three or four possibilities. As Bismarck used to say to his generals, ‘You can be sure that if the enemy has only two courses of action open to him, he will choose the third.’ Alfred Sloan, the renowned President of General Motors, was even known to adjourn meetings in which he was presented with two alternatives. ‘Please go away and generate more options,’ he would say.

You need to open your mind into wide focus to consider all possibilities, and that is where generating ideas (see Chapter 5) comes in. But then your valuing faculty must come into play in order to identify the feasible options. ‘Feasible’ means capable of being done or carried out or realised. If it is feasible it has some real likelihood of being workable. It can attain the end you have in mind.

In moving along the lobster pot (see the illustration below) from the feasible options (no more than five or six, for the mind finds it difficult to handle more) to three options and then to two (the true alternatives), the principle to bear in mind is that it is easier to falsify something than to verify it.

Suppose you are choosing between five medium-sized estate cars for your family. It is easy to eliminate the unsuitable ones.

As you work on it, for example, you may discover that one of the cars is 9 inches longer than the others, which will cause you a problem given the size of your garage. As for a second car, on studying the specifications you cannot see why it is £1,200 more expensive than the rest – apart from its prestigious name. So you drop that one too, leaving you now with three choices. You will notice another principle coming into play here, which (subject to the information/time curve) does take most of the pain out of decision making. Let me continue with the car example. Because your partner does not like the colours of the Toyota model and, being an artist by profession, feels strongly about it, you are able to eliminate that one. Your alternatives are now the Nissan and the Peugeot.

You have just read this book and so, being persuaded by its argument, you decide to trade some more time for some more information, and test drive the alternative cars. Both feel great and perform really well. You know that either will serve your purpose. It is now a question of money and the availability of the colours your partner likes. One of the dealers offers you a much better price and can deliver the right model in the range. Why hesitate?

Figure 2.4 The lobster pot model

The critical preliminary activity here is to establish the selection criteria. It is worth dividing them into different levels of priority. (See the illustration below.)

Figure 2.5 Decision-making criteria

Unless an option meets the MUST requirements you should discard it. But after the essentials have been satisfied, the list of desirables – highly desirable SHOULDs or pleasant addition MIGHTs – comes into play.

Choosing a car is a relatively simple case, because there is a finite number of models to choose from and a relatively simple list of criteria. In order to help you choose in more complex cases, remember that you can make a decision by:

- listing the advantages and disadvantages;

- examining the consequences of each course;

- testing the proposed course against the yardstick of your aim or objective;

- weighing the risks against the expected gains.

Assessing risk

What makes decisions really difficult is the factor of high risk. You may recall the conflicting advice of the two proverbs Look before you leap and He who hesitates is lost. There is an important skill in calculating risk. Calculation sounds mathematical, and there are plenty of management books with ‘decision making’ in the title that offer various ‘probability theories’ and statistical methods to take the pain out of risk assessment. Sometimes it can help to assign numbers and calculate in that way, but the contribution of mathematics to this field is very limited. Experience plays a much larger part.

One helpful idea is to define the worst downside – what happens in the worst scenario? Can you accept that, or will it sink you? But in high-risk/high-reward situations, although you may know that you will be sunk if it does not all work out, you may still decide to take the high-risk course because the reward is just too important for you to forgo it.

You then have to address your mind to doing all you can to reduce the risk. It is here that experience, practice, consultation with specialists, reconnaissance and mental rehearsals may all be relevant techniques. You are trying to turn the possibility of success into the probability of success, but you will not be able to eliminate risk altogether: in this situation there are too many contingencies.

Assessing consequences

Risk is one aspect of thinking through the consequences of the feasible courses of action.

Consequences come in two forms: manifest and latent. Manifest consequences are ones that, in principle, you can foresee when you make your decision. I say ‘in principle’ because that does not mean to say that you did foresee them. What I mean is that any reasonable person with the knowledge, experience, or skill expected of someone in your position would foresee those consequences. If you try to rob a bank, for example, the manifest consequences are obvious to any reasonable person:

- You might become amazingly rich.

- People, including you, might get hurt.

- You could be sent to prison.

Latent consequences are different in that they are not nearly so probable, or even possible, and a reasonable person might be forgiven for not seeing the knock-on effects that result from the complex chain of events triggered off by a decision. Admittedly, with the aid of computers it becomes a little easier in certain fields to identify latent consequences, but it is seldom possible to insulate yourself against pleasant or unpleasant surprises. We just cannot foresee the future in that way.

The emergence of latent consequences, of course, triggers off another round of decision-making and problem-solving activity. Yet solutions are the seeds of new problems.

Introducing performance-related pay for individuals, for example, solves some motivational problems, but what other problems does it tend to create for teams and organisations, not to mention the individuals concerned?

Fill the quarters of the window in the illustration below with the consequences of a decision to make pay totally performance-related. Review the completed window – remember, you are looking for insights.

I suppose that if we knew all the latent consequences of all our decisions at the time of making them, we should soon decide to stay in bed all day and never make another decision! But that decision in itself would have manifest and latent consequences… All that we can do, as humans and not angels or gods, is to make the best decisions we can, given the information and circumstances, and then make other decisions to deal with the latent consequences as they arise.

Remember that there is a big difference between a wrong decision and a bad decision. A wrong decision is choosing to dig your only oil well in this place rather than that one. It’s an expensive mistake, but the fault lies with the method. A bad decision is launching the space shuttle Challenger on a severely cold morning when the contracting engineers responsible for the seals in the engines have predicted a nearly 100 per cent chance that the seals will fail in such conditions. They did – with a tragic loss of life. Here the method or process of decision making was deliberately ignored or irresponsibly put on one side.

The distinction is important because it separates outcomes, which you cannot fully control because of the part that luck or chance plays, from process, which you can. Wrong decisions are an inevitable aspect of life, both in our personal and professional lives. We redeem them by learning the lessons they teach us, paying the fees that life charges as cheerfully as we can. But bad decisions are predictable pitfalls; they are unforced errors. They are eminently avoidable if you use the proven processes, methods and techniques outlined in this book.

Figure 2.6 The outcomes window

Decision comes from a Latin verb meaning ‘to cut off’. It is related to such cutting words as ‘scissors’ and ‘incision’.

Figure 2.7 The point of no return

What is ‘cut off’ when you make a decision is the preliminary activity of thinking, especially the business of weighing up the pros and cons of the various courses of action. You now move into the action phase. Out with your cheque book – start talking about delivery dates! Things begin to happen.

It is always worth identifying what I have called the Point of No Return (PNR), a term that comes from aviation. At the half-way point in crossing the Atlantic, it is easier for the pilot to continue to Paris in the event of engine trouble than to turn back to New York. The pilot has passed the PNR and he or she is committed.

In its wider sense the PNR is the point at which it costs you more in various coinages to turn back or change your mind than to continue with a decision that you now know to be an imperfect one. In most decisions you do have a little leeway before you are finally committed: you can still change your mind. Often, as in the case study of Conrad Hilton (see page 12), it is your Depth Mind that double-checks your decision. It either whispers, ‘Yes, I am satisfied’ or begins an insidious and insistent campaign to make you at least review your decision, if not change your mind.

There is another reason for seeing implementation as a part in the decision-making process rather than the end of it. Your valuing faculty is bound to come into play at some stage in order to evaluate the decision. Did you get it right? Could you have made the decision more quickly or more gracefully, perhaps at less cost to others? All this data goes into your memory bank and informs the Depth Mind, so that the next time you make a similar decision this information about your past may be available to you in the form of a more educated intuition. This is what constitutes what we call experience.

Remember, your Depth Mind really does work!

In 2006 some researchers at the University of Amsterdam decided to put the Depth Mind theory to the test. The psychologists asked a group of volunteers to pretend they were about to buy one of four cars. The volunteers were given lots of information about the cars, and one model was much better than the others.

Half the volunteers were given time to ponder the merits of each car, while the others were given puzzles to solve to keep their minds busy. Both groups were then asked to pick the car they would buy.

The results showed that those who restricted themselves to conscious thought were less likely to have chosen the best deal.

Those whose surface minds were occupied with the irrelevant puzzles made better choices. In a second experiment, the volunteers were faced with furniture choices at Ikea.

What the experiments show is that your Depth Mind can deal with more facts and figures than your conscious mind. The latter is good at simple choices, such as buying different towels or different sets of oven mitts. But choices made in complex matters, such as between different houses or cars, are better if your Depth Mind is involved.

The principle, I may add, always applies over people decisions, especially the choice of one’s life partner. ‘I have no other but a woman’s reason. I think him so because I think him so,’ says one of Shakespeare’s heroines. In less eloquent language we might say that it is our Depth Mind that can best process all the complex information that comes from another person and transform it into a simple but profound judgement. Who knows how this work is accomplished in the inner hive of the mind?

Take care that the honey does not remain in you in the same state as when you gathered it: bees would have no credit unless they transformed it into something different and better.

Petrach

- Sometimes it is useful for the mind to have a framework for approaching potentially difficult tasks. In decision making there is such a simple framework of five steps or phases. Think of it more as a spiralling process, like this:

- Defining the objective is invariably important in decision making. One useful tip is to write it down, for seeing it in writing often helps you to attain the necessary clarity of mind.

- Collecting relevant information involves both surveying the available information and then taking steps to acquire the missing but relevant information to the matter in hand.

- For generating feasible options, remember the lobster pot model! You should be able to move systematically from a host of possibilities – some of them may be the results of imaginative thinking – to a diminishing set of feasible options, the courses of action that are actually practicable given the resources available.

- In making the decision your chosen success criteria (the product of the valuing function of the mind) come into play. It is useful to grade these yardsticks into the criteria that the proposed course of action MUST, SHOULD and MIGHT meet. You will also need to assess the risks involved: what are the manifest and the possible latent consequences of the decision in view?

- Implementing and evaluating the decision should be seen as part of the overall process. You may hardly notice the actual point of decision, just as passengers on a ship may be asleep when their ship crosses the equator line. The ‘cut off’ point, be it conscious or unconscious, is when thinking ends – your mind is made up – and you move into the action or implementation phase. But you are still evaluating the decision, and up to the Point of No Return (PNR), you can always turn back if the early signs dictate.

- If you have all the required information, the mind goes through the point of decision effortlessly – indeed, do you really have to take a decision? Thus it has been said that ‘a decision is the action an executive must take when he or she has information so incomplete that the answer does not suggest itself’.

Not to decide is to decide.

English proverb