End of a bolide: A meteor breaks up with a flare and a bang.

During every clear night, needle-like streaks of light are seen cutting across the sky. One, two—a dozen or more-may be seen in an hour. Often called “shooting stars,” the objects that make these trails are actually bits of stone and iron from outer space, called meteors or meteoroids. They race into our atmosphere with such speed—up to 44 miles per second—that friction with the air heats them to incandescence. Most turn to vapor and dust long before they reach the ground.

End of a bolide: A meteor breaks up with a flare and a bang.

Unusually slow, bright meteors are called “fireballs.” Frequently their trail remains visible for some time. Fireballs that explode are “bolides.”

Most meteors are no bigger than rice grains, and they become incandescent 50 to 75 miles up. Larger ones break up during their fiery trip through our atmosphere, and fragments of these hit the Earth. Once in few centuries a really big one hits, such as the meteor that made Meteor Crater in Arizona.

Some meteor trails are short, and some are long—20° or more. Most are white, blue, or yellow. Fireballs and bolides are very bright. Their streak is thicker, lacking the usual thin, needle-like appearance. Sometimes their path is crooked or broken, and several explosions may mark their course.

Meteoritic material entering Earth’s atmosphere daily may total several tons. The number of meteors actually reaching the ground may be in the billions, but these are so small that their total weight is estimated at only one ton.

Fragments of meteors found on the ground are called “meteorites.” They usually have peculiar shapes and are heavy for their size. Most consist mainly of iron, some are predominantly stone, and still others consist of both. Cobalt and nickel, too, may be present.

Meteorites look fused, or melted, on the outside. Hence they are easily confused with bits of slag. Observers who want to be able to identify meteorites should study specimens on display in planetariums and museums.

Usually more meteors are seen near midnight and in early morning, because then our part of Earth is facing forward in our journey around the Sun and we are heading into the meteor swarms.

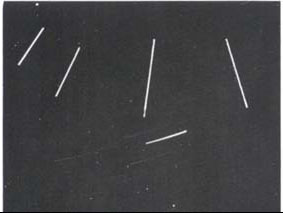

Intruder among the stars: A brilliant meteor was caught on this 40-minute exposure of the Cassiopeia region. A clock drive kept the camera trained on the star field. (Walter Palmstörfer, Pettenbach, Oberösterreich, Austria)

In group observing for meteors, each person has his own section of the sky to patrol. Binoculars are not necessary but help; wide-field ones are best.

Meteor trails make interesting photographs (see here). Also, amateurs with a short-wave radio receiver can “listen” to meteors. The set is tuned to a very weak distant station, preferably above 15 megacycles. The volume is kept very low. When a meteor in the upper atmosphere ionizes a patch of air, creating a momentary “reflector” for signals, the volume of the station’s signal rises sharply. Doppler changes in pitch may occur. On a good morning, several hundred meteors may be heard.

METEOR SHOWERS In certain parts of the sky, over periods of days or weeks, “showers” of meteors can be seen. In an hour 150 may be observed. Showers occur whenever Earth, in its journey around the Sun, encounters a vast swarm of meteors—perhaps remains of a comet. A shower appears to radiate from one point in the sky, and is likely to recur there about the same time each year. Showers are named after the constellations from which they seem to radiate.

Iron meteorite: This specimen, about 8 inches long, weighs 33 pounds. Hollows in its surface were left by portions removed by friction and heating during passage through atmosphere. (American Mus. of Nat. Hist.)

THINGS TO DO (1) Observe showers, alone or with groups. (2) Count meteors seen in an hour. If a shower, count the number per minute. (3) On a star chart, plot points of beginning and end of meteor trails. (4) If a meteor falls in your vicinity, try to find it. Watch your local newspaper for report. Find persons who saw the meteor fall and attempt to trace it. Cooperate with a nearby observatory, if any.

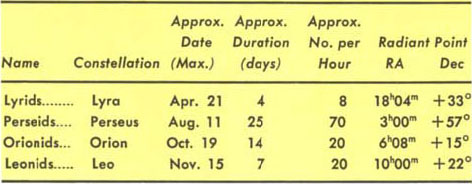

PROMINENT METEOR SHOWERS

Listed here are a few prominent “trustworthy” showers. Many more are listed in textbooks and handbooks.

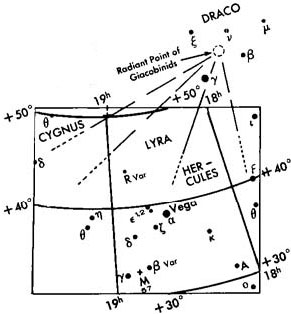

Giacobinid meteor shower, 1946: In this time exposure, a rotating shutter in the camera broke up the meteor trails but not the star trails. In drawing of same field, meteor trails are extended to the radiant point. (Peter M. Millman)