Inspirational Islanders

These humble, hardworking women and men who lived—and tragically in one case died—during the Occupation aren’t widely known outside Jersey, but they deserve to be.

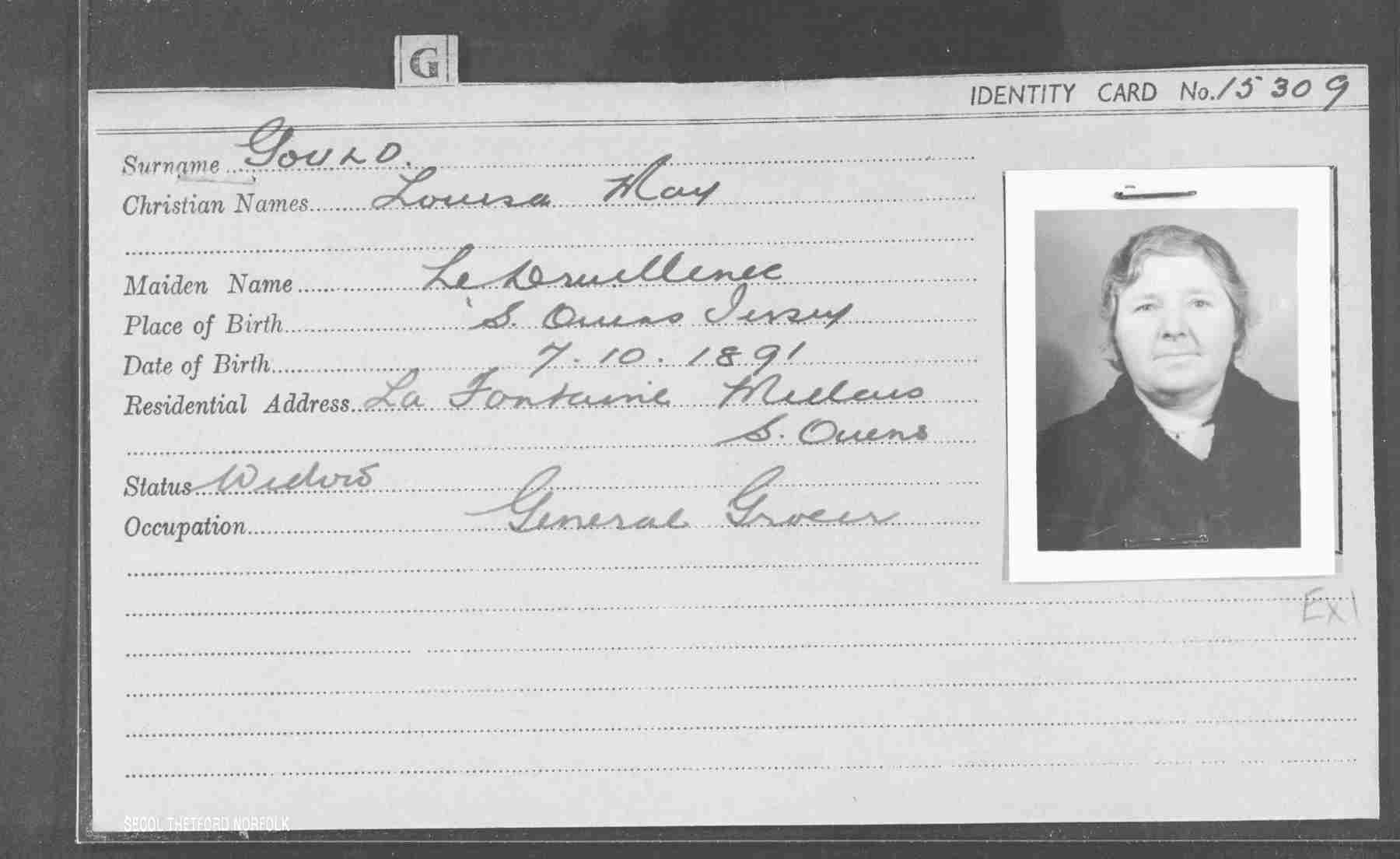

The Shopkeeper

Louisa Gould’s registration card. Image courtesy of Jersey Archive

Louisa Gould from the book club is based on a remarkable Jersey woman. In July 1941, Louisa received a message that her son Edward had been killed in action in the Mediterranean. Three months later, in October 1941, a Soviet plane, piloted by a young man named Feodor Buryi, was shot down in Germany. He was caught and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp, before being transported to Jersey to work.

Feodor was one of many captured Russian soldiers termed Untermenschen (sub-humans) by the Nazi regime and used as slave labor. Many of these soldiers were sent to the Channel Islands and used to build a concentration camp on the island of Alderney—the only one on British territory during World War II. The prisoners were treated with sadistic brutality. Many of the people I interviewed witnessed their beatings and pitiful state.

Feodor was sent to a notoriously brutal work camp called Lager Immelmann at the foot of Jubilee Hill, St. Peter, Jersey. (Most of the camps for workers in Jersey were named after successful German U-boat commanders.) He escaped but was recaptured and as punishment was made to strip naked and push a wheelbarrow loaded with stones until he collapsed. He was then made to stand outside in a freezing water butt all night and beaten. On the basis he was going to die anyway, he attempted another escape.

This time he was given shelter for three months in a hay loft belonging to René Le Mottée until someone from the local community informed their occupiers. Feodor then approached Louisa for help, and with her dead son in mind, she bravely agreed to help him, saying, “I had to do something for another mother’s son.” She treated him with love and respect, bathed his wounds and altered her son’s clothing to fit him. “Bill,” as he became known, stayed with Louisa for 20 months until she was denounced and arrested, along with other members of her family, including her brother, sister and two friends.

Louisa was taken to Ravensbrück concentration camp; her brother Harold Le Druillenec, who had simply listened to Louisa’s wireless, was sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Harold was the only British man to survive the camp. He returned to Jersey after the war, testified at the Nuremberg Trials and became headmaster of St. John’s Primary School before dying in 1985, aged 73.

Louisa never came home to Jersey.

She and her friend Berthe Pitolet, who had been arrested along with her, were taken to Jacques-Cartier Prison in Rennes. When the Allied forces bombed the prison, Berthe saw her opportunity to escape. For whatever reason, Louisa did not follow her friend. And so it was that she was loaded onto a convoy heading east. Ravensbrück was her final destination.

Worn out by forced labor in the camp, she was no longer of any use to her captors and in the last winter of war, was murdered in the gas chamber at Ravensbrück. She acted with unimaginable courage, giving English lessons to other inmates and helping to care for the sick.

I don’t suppose it occurred to Louisa for one moment that she would end up in such a place for her misdemeanor. Why would it? Sheltered from the knowledge of the camps and with all their news censored, she could never have dreamt that such a place of apocalyptic horror awaited her. I don’t suppose any of the islanders who perished in camps did either. Please do read the article further down about the Channel Islanders who died in some of Germany’s most notorious death camps and prisons.

Louisa’s appearance at the Wartime Book Club is fictional, as is my interpretation of why she didn’t escape from the prison when she had the chance. But more than anything, I hope the courage and humanity I have my Louisa displaying in this novel stays close to the spirit of this extraordinary woman.

Louisa’s story is beautifully brought to life in the film Another Mother’s Son, released in 2017.

To the best of my knowledge, Louisa’s informers, or indeed any informers, black marketeers, fraternizers or collaborators based in the Channel Islands during the Occupation, faced no justice after the war. Indeed, many who had been interviewed by British Intelligence were sent to the UK for their own protection.

Not a single Nazi, or member of the SS stationed in Alderney during the war, was arrested or faced a war crime trial.

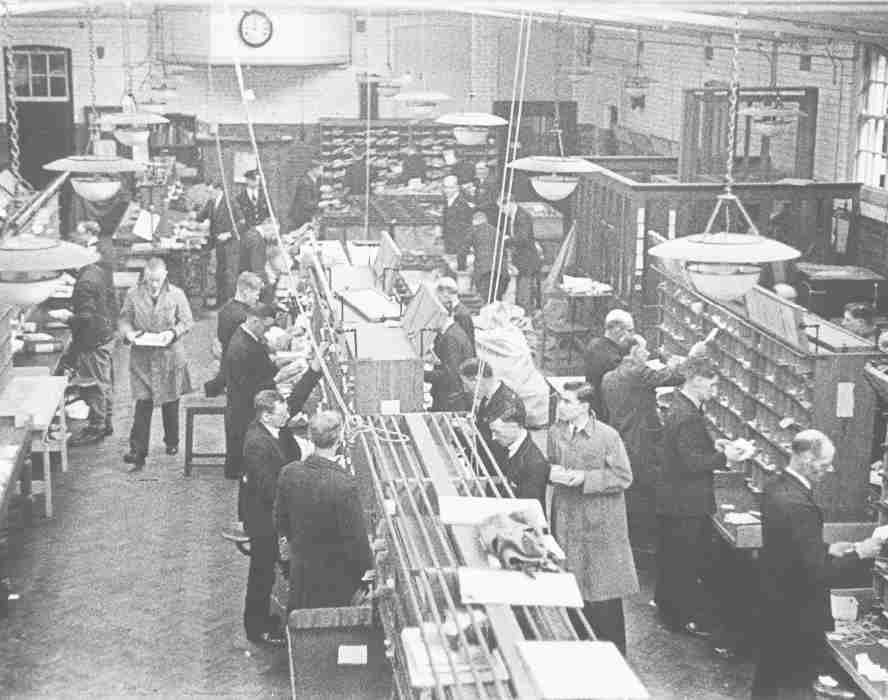

Jersey’s Plucky Posties

Jersey Post Sorting Office, where informers’ letters were intercepted. Photo reproduced courtesy of Dave Vautier.

Bea’s activities in wartime are based on another true story. For the first time in Jersey’s history, the wartime postal workers were hell-bent on not delivering the mail! When it came to delivering hateful informers’ letters like the one below, for many it was a step too far, especially when they knew that those who had been denounced faced arrest and a potential death sentence in a Nazi prison. The posties of His Majesty’s Government embodied the kind of quiet determination and personal bravery that undoubtedly saved countless lives.

A “poison-pen” letter written during the Occupation. Photo: CIOS Jersey.

Dave Vautier, former postman and author of The History and Stories of the Jersey Post Office, told me:

The Post Office consisted of men who fought in the First World War, one gaining the Victoria Cross, and men and women who had faced ordeals of five years of Occupation by a ruthless enemy, and none had fallen by the wayside.

Men who had helped in the Dunkirk retreat, members who had been prisoners of war, three members who had suffered deportation to a prisoner-of-war camp, and several who had faced the wrath of the Secret Field Police by destroying information necessary to carry out their vile practices.

Certain postmen either chucked these informers’ letters straight in the boiler, or they would steam them open. Letters which weren’t destroyed would be held back for three days before they were date-stamped and then delivered. In the meantime, the postman on his rounds would have warned the recipient that a search was imminent, and the radio or other forbidden item would be hastily removed.

The British Post Office paid tribute to them at the end of the war, but many of these unassuming and heroic postal workers—like Eric Hassell, Billy Matson, Harold “Peddler” Palmer and Philip Warder—were never properly recognized.

Jack Thomas Counter (who I’ve based the character of Arthur on) was awarded the Victoria Cross in 1918. He came to live in Jersey in 1929 and worked as a postman until his retirement in 1959. He died in 1970 and his ashes are buried in St. Saviour’s churchyard.

Philip Warder shouldn’t even have been there. He was due to follow his wife to England, but stayed behind to disconnect all the GPO telephone equipment at the last possible moment before the Germans arrived and got stuck there for five years, separated from his wife Trix and their three children. Instead he turned his hand to intercepting poison-pen letters at the Post Office.

“He felt it was his duty to intercept these letters,” his historian grandson Mark Lamerton told me.

My grandfather also worked with Dr. McKinstry to smuggle a transmitter into Les Vaux Sanitorium in order to secretly transmit intelligence to the English. They chose this location because the Germans were terrified of tuberculosis and so were unlikely to visit the sanitorium.

He had planned to escape from Jersey with some other men in September 1944, but was under an obligation to the bailiff and could not go with the others who successfully escaped from the island.

With food strictly rationed, he came up with an ingenious method of transporting fresh meat around the island without it being confiscated by the Germans. He would collect the meat, such as pork, from the farm in a hearse. Luckily for him the German guards at the checkpoints never asked to look inside the coffin.

But of all Philip Warder’s many acts of ingenuity and bravery during the Occupation, it was the interception of informers’ letters, which left the most profound mark.

My grandfather kept these letters for years after the Occupation. He would show them to anyone who showed an interest, as he couldn’t believe this despicable behavior between islanders. He was baffled by people’s spite. Eventually he parted with them and gave them to a local museum.

Post Office worker Philip Warder, whose courage saved lives. Copyright Mark Lamerton

To me this is one of the greatest untold resistance stories. There is something so intriguing about postmen destroying letters instead of delivering them. I loved studying the photo above of the sorting office, to see what sleight of hand might be occurring, what letters were slipped in pockets in order that lives might be saved.

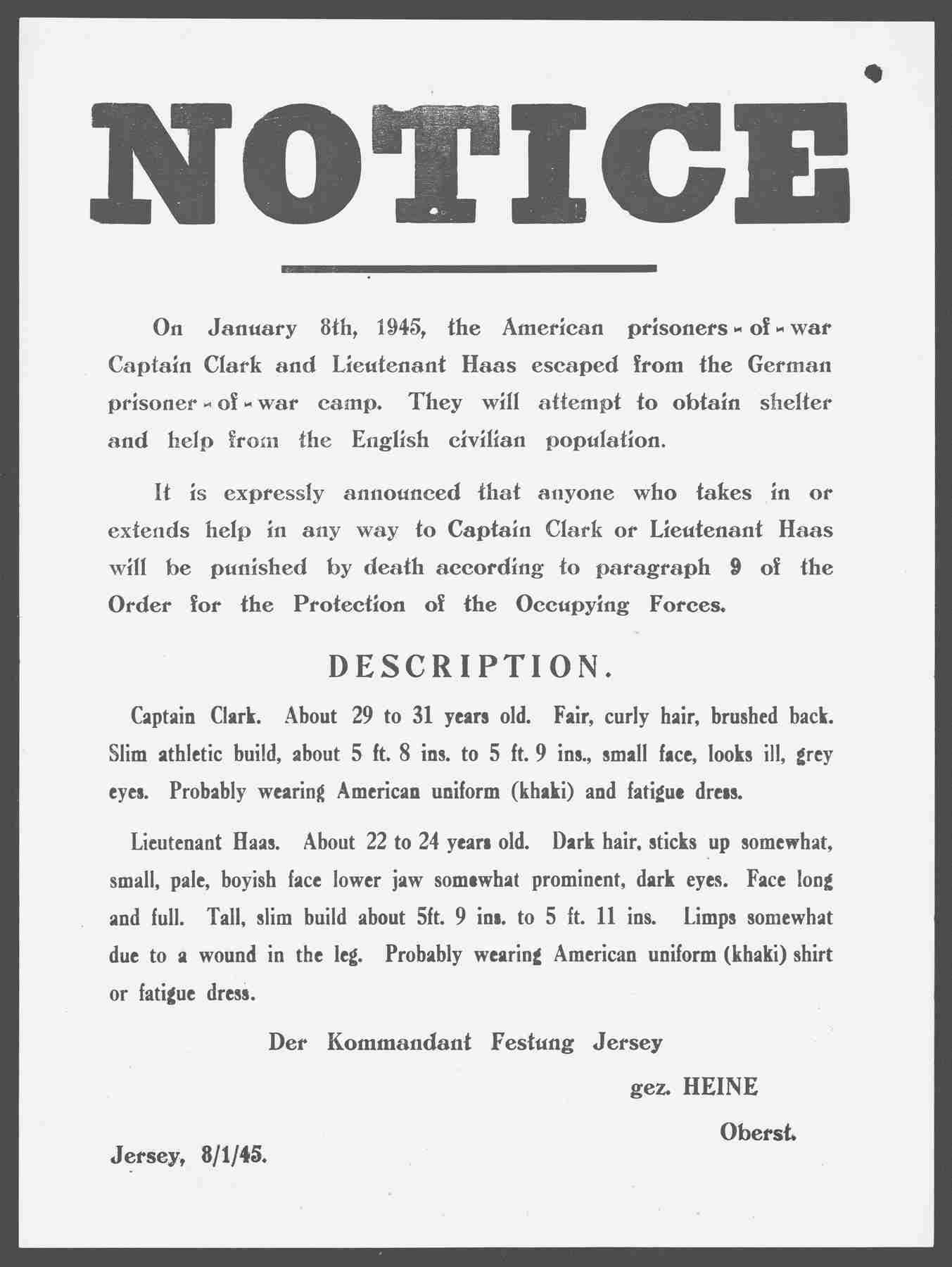

Heroic Americans1

These two aren’t strictly speaking islanders, but as the story of these two daring young men is not only true, but also inspired the character of Red, I felt it would be remiss not to include it here.

It sounds like the plot of blockbuster film The Great Escape. Captain Ed Clark from the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas (Assistant Division Engineer of the 25th Armored Engineers) and Yale-educated First Lt. George C. Haas from New York (Aerial Observer with the 6th Armored Division) were captured in Brittany, in August 1944, and brought to Jersey to avoid falling back into Allied hands.

They were imprisoned in a prisoner-of-war camp at South Hill, St. Helier.

Plans were made to try to escape by digging a tunnel from the toilets, but the plan was scuppered when a guard noticed that George took a considerable time when going to the loo. The guard investigated and signs of tunneling were discovered. As punishment, George was sent to Newgate Prison for 10 days’ solitary confinement only to discover it was easy to chat to other inmates, all locals in for resistance activities. His stay proved useful as he was able to find out detailed plans of the island and a list of loyal islanders to stay with.

“It is amazing how much more generous people become when they are undergoing troubles together,” George later wrote. He returned to the prison camp with a rough map etched on toilet paper tucked under the inner sole of his shoe and a plan forming in his mind.

Just before dawn on 8 January 1945, Ed and George escaped over the 12-foot-high wall and barbed wire using a crutch and a bent iron poker as a ladder. It wasn’t until 10 a.m. that their German captors discovered two dummy body shapes in their beds. The Americans were treated like old friends at two homes on the island before managing to escape on a rowing boat with donated food, water and warm clothing.

Dodging German patrols, the plucky pair battled 60-mile-an-hour winds, waves “like rollercoasters and freezing snowstorms,” before arriving in Countances on the French coast after 15 grueling hours. “The Lord was sitting on both our shoulders,” George later recollected.

Their travels ended in Paris with a return to duty and an eventual return to the United States. George went home, got a job with Pepsi-Cola, married and had three daughters. Ed stayed in the U.S. Army, retiring after 25 years of service. On the fiftieth anniversary of their great escape, George and Ed returned to Jersey to witness the unveiling of a monument in their honor.

Islanders were warned against helping the escaped Americans. Despite the death penalty, two brave families came to their aid. Poster reproduced courtesy of Jersey Archive.

Ed (left) and George (right) returned to the island 50 years after their great escape to witness the unveiling of a plaque in their honor. Courtesy of the JEP Collection at Jersey Archive.

The Single Mum

Henriette Marie Louise Sidané le Chavalier.

There is a curious irony to the story of Henriette Marie Louise Sidané le Chavalier. She was freed from a bad marriage because of the German invasion. As her daughter, 87-year-old Maggie Moisan, admits:

My mum suffered a great deal at my father’s hands. He was a truly horrible man, who ran up debts, drank too much and used my mother as a punchbag.

He would get paid on the Friday and have drunk it all away by Monday, leaving my mother with no housekeeping to raise four daughters. The weekends were just horrible.

I shan’t list all the violent episodes Maggie witnessed growing up, suffice to say the admiration she feels toward her mother is entirely understandable.

It was my job to pick out Dad’s army issue false teeth from the toilet, where he’d cough them out drunk, and clean them for him. Sometimes I used to have horrible thoughts toward him. I loved my mother so much and I hated him for what he did to her.

Henriette’s liberation from her controlling husband came when he joined the army, leaving her to care for Maggie and her sisters Lily and Doreen (her other sister Phyllis had joined the ATS). This hardworking, resilient woman then found herself living under German Occupation, but after the violence she’d already endured, it was perhaps the lesser of two evils.

“My mother blossomed under the Occupation, out from under her husband’s domineering shadow,” Maggie says.

She was no stranger to hard work. Mum had returned to work in the fields growing tomatoes when I was just a couple of days old, simply parking me in a pram nearby, breastfeeding me when I needed it. She had to, she had 30,000 tomato plants to tend to and no work, no pay. After Dad left she got a job at a farm and worked her way through the Occupation. Mum was a typical country woman, always in wooden clogs, called sabots. She smoked cigs and spoke Jèrriais. We lived a rustic, rural way of life, Mum would draw water from an outside well.

Like many women of her generation, Henriette was resourceful.

I never knew her to have a day off. When she wasn’t working the farms, she was haggling, bartering and scouring the countryside, just to put clothes on our backs and food in our tummies.

Despite this, there was never enough food. When I was hungry, I went to the farm where Mum was working and she would squirt milk from the cow’s udder straight into my mouth. Once we were given a piece of soap as a gift at Christmas from school. Me and my friend tried to eat it we were that hungry.

Maggie’s mother also worked as a herbalist, concocting remedies for every ailment from herbs and plants, just as well as there was precious little medicine. “Somehow she managed to cure me of boils, impetigo and whooping cough. She also used to help local women deliver their babies. She had so much feminine knowledge,” Maggie says. “Mind you, that generation never knew anything about the menopause.”

As the Occupation wore on and food became even more scarce, Maggie was devastated when her pet dog Beauty went missing: “The Germans had stolen Beauty and eaten her!”

As if having your pet dog eaten wasn’t enough, Maggie also witnessed the death of one of the Russian slaves.

I was out picking rabbit food for Mum, when I saw this slave worker in rags leaning on this spade. He slumped onto the floor. I saw the OT worker kick him to see if he was dead. Then they just picked him up and slung him on top of the rubbish and drove off. I was only nine. It left a big impression.

On Liberation Day, after completing her jobs, Maggie and her mum walked to St. Helier to soak up the atmosphere.

“Everyone was euphoric, but I saw a huge crowd round a naked woman, chanting ‘Jerrybag’ over and over. I was very frightened to see that.”

Tempering Henriette’s relief that the war was over was the sobering knowledge of her husband’s return.

Mum had managed to pay off all Dad’s debts while he was away. Then, a few months after the Liberation, Dad turned up looking like a spiv in his demob suit and polished shoes and my Mum was still in her rags. “I’m a changed man,” he said. Sadly he was. He was even worse.

Maggie’s beloved mother died in 1967, aged 76, leaving an enormous hole in her daughter’s life. “I always say the mothers were the heroines back then, with what they had to put up with,” she ruminates.

Maggie was a delight to spend time with. Bright, energetic and wise, with a mischievous twinkle in her eye. After an absorbing two hours, I reluctantly took my leave and stepped outside. “Oh it’s raining,” I complained. “That’s not rain, my love,” she laughed. “It’s liquid sunshine.”

The Angry Young Man

There’s something about the cut of this young man’s jib that tells you he is crackling with patriotism. Look at the hint of mischief in that smile, the forbidden Union Jack handkerchief poking out of his breast pocket.

Don Dolbel during the Occupation. Photograph reproduced courtesy of Don Dolbel.

Don Dolbel was 15 when the Occupation began and 19 when it ended. His biggest regret was being too young to join the Royal Navy and fight. He was just two months off being fifteen—back then the legal age to join up—when the Germans invaded and put paid to his ambitions. Instead he got a job working as a baker’s apprentice, and in his spare time boxed to channel his anger. “I boxed professionally all round Jersey,” says Don.

Back then I was light on my feet, King of the Ring. I was young and fizzing over with energy.

The day war broke out I buried a gun and a Union Jack flag beneath the apple tree in our garden. I was what you might call “a bit of a lad” and often got myself into scrapes.

Those scrapes including breaking curfew, throwing tar over the home of a farmer who used to give all his potatoes to the Germans, cycling past a German sentry with a dead pig covered in a white sheet on the back of his trailer and shinning up the flagpole outside German Naval High Command to rip down their swastika, as well as distributing RAF leaflets. Any one of these breaches of German rule would have been enough to get him jailed or deported. You get the sense he was almost goading them into arresting him.

“I remember once walking round with a knife in my pocket determined that I would stab a German if I saw one. I never did. What was I thinking?” he reflects.

For Don, the greatest loss was the theft of his youth, and all the possibility of adventure that promised. On 1 July 1940, his world disintegrated and for a high-spirited man this was too much to accept. At moments in our conversation, that frustration was still palpable and Jimmy’s character came to me as we were talking. Don was 96 years old when I interviewed him and sharp as a tack. The memories were still vivid in his mind.

We saw the slaves, dressed in rags. It was a pitiful sight. One time we saw them shuffling past and my father said, “I’m not very hungry tonight,” and left his plate out for them by the hedge. It was only potatoes and veg but they fell on it. Tomorrow it would be my mother’s turn not to be hungry, and so it went on. We tried to do what we could to help.

Toward the end of the war—the siege—people were starving, I had to sit up all night at the bakehouse I worked in with a hockey stick, in case of someone breaking in. Theft was rife; slaves, foreign workers, Germans, everyone was pinching, we were starving.

To keep up morale we’d listen to Churchill’s voice and the chimes of Big Ben on our secret wireless in the attic. I knew we’d win eventually.

“What got you through it?” I asked.

“Wickedness,” he replied with a wink.

Today, he’s less inclined to get into scrapes, and as well as volunteering, plays his accordion at events, including, to his credit, at the German town of Bad Wurzach, which is twinned with St. Helier. He celebrated his 91st birthday with a tandem parachute jump, so perhaps the maverick’s not left him yet.

Don’s a charming man: dapper, garrulous and full of life, a walking history book some might say.

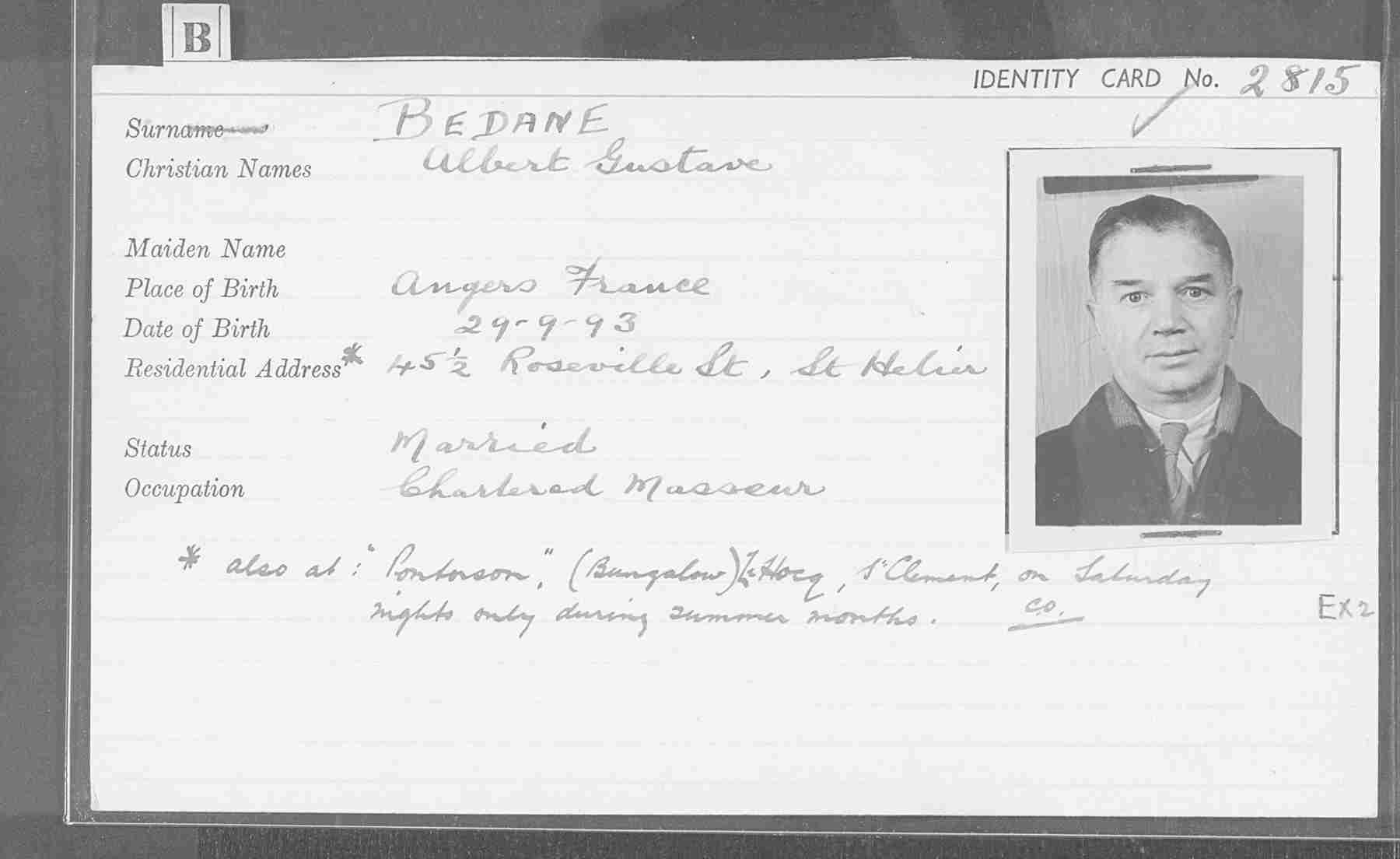

The Savior

Albert Bedane, top, sheltered Mary Richardson, bottom, for over two years in the cellar of his St. Helier home. Images courtesy of Jersey Archive.

During the Occupation, Albert Bedane was a physiotherapist with a secret. Behind the doors of his imposing townhouse in Roseville Street, St. Helier, he was hiding a Jewish Dutch woman called Mary Richardson in his three-room cellar. Given the close proximity of his home to that of the German Secret Field Police, this was a courageous act. If he had been caught, he would have been deported and probably died in a concentration camp.

As the Germans were preparing to deport Mrs. Richardson she managed to escape and hide with Albert for more than two years until the end of the war.

After the war, Albert rarely talked about what he’d done. Today, he is an island hero.

In 2000, Albert Bedane was posthumously recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations” and awarded a medal by Israel’s Yad Vashem for saving Mary’s life.

Jersey Archive has a really excellent Resistance Trail, which tells you about people like Albert and Louisa, as well as many other islanders and places intimately involved in the story of Jersey’s resistance. You can view it online or perhaps try it yourself if you visit Jersey. https://www.jerseyheritage.org/media/Resistance%20Trail/Leaflet.pdf.

Footnote

1 Source: Margaret Ginns, “British and American POWs in Jersey,” in Channel Islands Occupation Review, 1983, and written recollections by George Haas, kept at Jersey Archive.