Chapter 9

The Price Is Right! Pricing Your Pieces

IN THIS CHAPTER

Understanding pricing formulas

Understanding pricing formulas

Making sure your prices make sense

Making sure your prices make sense

Assessing the value of vintage items

Assessing the value of vintage items

Pricing items to move during sales

Pricing items to move during sales

Years ago, a close friend developed a keen business idea: the million-dollar hot dog. The million-dollar hot dog would be just like any other hot dog, except that it would cost a million dollars. Yes, demand for the million-dollar hot dog may be low. But as our friend rightly pointed out, “You really only ever need to sell one!”

Too many Etsy sellers err on the other end of the spectrum. They underestimate the worth of their items, and so they underprice them. But this poses its own set of problems. For one thing, you lose out on profits. For another, it can create the impression that your items are of low quality.

The trick is to strike a balance. You want to price your pieces high enough to cover your costs and turn a healthy profit. But you need to price them low enough that you can sell a reasonable volume of goods. Finding that sweet spot is the focus of this chapter.

Formula One: Pricing Formulas

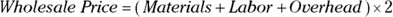

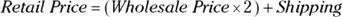

Not all creative types share a general distaste for math, but lots of us do. Unfortunately, if you hope to run a profitable Etsy shop, you need to get comfortable with doing a little arithmetic, especially when it comes to pricing your pieces. But don’t freak out! We’re not talking calculus here, or even trigonometry. All you have to learn are two very simple formulas:

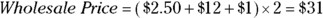

Calculating the cost of materials

When calculating your cost for materials, include the price of every little component in your piece. For example, suppose you sell handmade puppy plush toys for babies. Your material cost for each pup may include the cost of fabric, a label, rickrack, stuffing, and thread.

What matters here is the cost of what you used to produce one piece. For example, suppose you spent $125 on materials to produce 50 plush pups. To calculate the price of materials per piece, you divide $125 by 50, for a total of $2.50 per piece.

Figuring labor costs

What if, while perusing the want ads in your local newspaper, you happened upon this listing:

Wanted: Skilled professional to expertly fabricate product by hand. Must also run every aspect of business, including sourcing supplies, maintaining and marketing shop, interacting with customers, and ensuring that items sold are artfully packaged and shipped to buyers. Pay: $0.

Odds are, that’s a job you’d pass up. And yet, many Etsy sellers pay themselves exactly nada to run their shops. Don’t fall into this trap! Like anyone, you deserve to be compensated for your work. Your pricing formula must include the cost of your labor.

To calculate your labor costs, first set an hourly rate for your time. Be sure to pay yourself a fair wage — one that accounts for the skill required to craft your piece. Also think about how much you want or need to earn for your time. If you’re just starting out, you may opt for a lower hourly rate. You can give always yourself periodic raises as your skills improve.

Another approach to figuring your hourly rate is to work backward. That is, figure out how much you need to be able to “bill” for each day and divide that by the number of hours you intend to work. So say you need to earn $160 a day and you plan to work eight hours a day. You simply divide $160 by 8 for an hourly rate of $20. We aren’t saying you should charge $20 an hour! This is just an easy round number that works well for this example.

Armed with your hourly rate, you’re ready to work out your labor costs. These costs must take into account the time it takes to design a piece, shop for supplies for the piece, construct the piece, photograph the piece, create the item listing for the piece (including composing the item title and description), correspond with the buyer, and package and ship the item.

As with materials costs (described in the previous section), you can amortize some of your labor costs — that is, you can spread them out. For example, if it took you four hours to develop the design for a piece, but you plan to make 50 of them, you can amortize those four hours over the 50 finished pieces. Similarly, you likely shop for supplies for several pieces at one time, meaning that you can spread the time you spend shopping across all the projects that you plan to craft using those supplies.

Let’s use those plush toy pups as an example. Suppose you spend four hours designing your toy and another hour shopping for enough supplies to construct 50 units. Assuming that your hourly rate is $20, your labor cost is $100 — or, spread out over 50 toys, $2 per toy. Suppose further that each toy takes 30 minutes to make, photograph, and package ($10 in labor). (Yes, we know, 30 minutes is on the low end. Humor us. It makes the math easier.) Your labor cost per toy is then $12.

Adding up overhead

Your overhead may encompass tools and equipment used in the manufacture of your products, office supplies, packaging supplies, utilities (for example, your internet connection, electricity used to power your sewing machine, and so on), and Etsy fees. (Note: These costs don’t include shipping. You generally calculate these costs separately and pass them along to the buyer. More on shipping costs in a moment.)

As with labor costs, you need to amortize your overhead costs — totaling them up and then spreading them out over all the items you make. As a simple example, if you calculate your monthly overhead at $50, and you produce 50 pieces a month as with those plush pups, your overhead is $1 per piece.

Of course, this calculation gets tricky when your overhead involves purchases of items like tools and equipment used in the manufacture of your products. In those cases, you want to amortize the items over their life span. For example, maybe you’ve bought a $250 sewing machine that you plan to use for five years. In that time, you anticipate that you’ll sew 500 pieces. Your overhead for the machine is then 50¢ per piece.

Understanding the “times 2”

At the start of “Formula One: Pricing Formulas,” earlier in this chapter, we provide the wholesale pricing formula, which calls for adding together your costs for materials, labor, and overhead and then multiplying the sum by 2. What’s up with that?

That “times 2” covers a host of things. It’s your profit. It’s what you invest back in your business. If your sewing machine breaks, the “times 2” is what you use to buy a new one. If you decide to expand your product line, that “times 2” is where you find the capital you need to grow. Or you may just use your “times 2” to build a nice nest egg for your business or a fund to fall back on if times get tough.

You may feel uncomfortable with all this two-timing, thinking that your labor costs are your “profit.” Don’t. Yes, you may be paying yourself to make your products, but if your business grows, that may not always be the case. Multiplying your costs by 2 enables you to ensure that your business is profitable, regardless of how it’s structured.

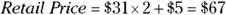

Pricing for wholesale and retail

As the proprietor of your own small manufacturing business, you need to establish two prices for your goods: the wholesale price and the retail price. The wholesale price is for customers who buy large quantities of your item to resell it. That customer then sells your piece to someone else at the retail price, which is usually (though not always) double the wholesale price.

We know what you’re thinking: “I’m going to sell my stuff only through my Etsy shop, so I’ll just charge everyone my wholesale price.” Right? Wrong! Even if you plan to sell your items exclusively through Etsy, you need to establish both a wholesale price and a retail price, and you need to sell your pieces on Etsy at the retail rate. Why? Two reasons. First, even if you have no plans to expand beyond your Etsy shop, you don’t want to cheat yourself of the chance to offer wholesale prices to bulk buyers if the opportunity arises. And second, you’ll almost certainly want to run the occasional sale in your Etsy shop. Pricing your goods for retail gives you some leeway to discount them as needed and still turn a profit. (More on running sales in a minute.)

Adjusting for free shipping and handling

Anymore, thanks to big-box businesses (think: Amazon), most online shoppers pretty much expect free shipping — including shoppers on Etsy. In fact, according to Etsy, shoppers on the site are 20 percent more likely to complete a purchase if shipping and handling are free.

To facilitate this, Etsy enables shop owners (read: you) to offer a free shipping guarantee. This guarantee automatically applies free shipping and handling to buyers in the U.S. when they spend $35 or more in your shop. Note: As an added bonus, Etsy’s search algorithms prioritize items that ship for free, making it easier for buyers to find them.

Ugh. Does all this mean you have to eat your shipping and handling costs anytime people avail themselves of your free shipping guarantee? Negatory. It just means you need to factor these costs into the price for each item you list. So, if shipping and handling an item will set you back $5, you need to up that item’s listing price by that same amount. (For help editing a listing, including changing its price, see Chapter 12.)

Putting it all together

To help you get comfortable with pricing your pieces, we run through an example using the puppy plush toys mentioned earlier. To recap, the cost of materials for each toy is $2.50; your total labor rate is $12 per item; and your overhead for each piece is $1. Oh, and say shipping sets you back $5. Your pricing equation, then, looks something like this:

Price-a-Roni: Evaluating Your Prices

The pricing formulas in the preceding section are a great way to determine your wholesale and retail prices. But they simply compute the price you need to charge for your piece to turn a healthy profit — not what the market may actually bear. To calculate that, you need to do a little research.

Assessing your competition’s pricing

To identify the price point that your market will bear, start by scoping out your competition, both on and off Etsy. If their prices are roughly in line with yours, you’re probably in good shape. If they’re significantly higher or lower, put yourself in your prospective buyer’s shoes and ask these questions:

- Would I buy my product or a competitor’s product? Why?

- Is my product made of better materials than my competitors’ products?

- Did crafting my product require more skill than my competitors’ products?

- Is my product different or special in any way?

- What do I think my product is worth?

Your answers to these questions will help you determine whether you need to adjust your price upward or downward. For example, if your product is better made than your competitor’s, you may be able to adjust your price upward. Ditto if it required more skill to build. Of course, if the opposite is true, you may need to lower your price.

Studying your target market

In gauging your price, you also need to consider your target market. Who, in your estimation, will buy your piece? How much disposable income does that person have? If your target market consists of 20-something hipsters, chances are they’re not quite as flush as, say, the 40-something set, so you may need to keep your prices lower. On the flip side, if that 40-something set is the market you’re after, you may be able to command a higher price.

As an aside, offering products at different price points is a great way to increase your customer base. For example, say you specialize in ceramics. In that case, you may make ceramic mugs to sell at a lower price point; simple, medium-sized bowls to sell at a slightly higher price point; and ornate platters to sell at a premium price point. This structure enables you to reach a larger range of potential buyers, which could help you increase your overall sales. As a bonus, this strategy is also a great way to nose out your niche in the market, because it quickly reveals which products your buyers respond to best.

Figuring out how to lower your prices

If your research has revealed that your prices will likely give your market sticker shock, you may need to lower them. The best way to do this is to lower your own costs. Ask yourself:

- Can I purchase my materials more cheaply from a different supplier?

- Can I spend less time making each piece?

- Can I redesign my product to require less in the way of supplies or labor — say, omitting the decorative rickrack piping on my plush pup?

After you manage to lower your costs, apply the formulas we talk about earlier in the chapter to determine the new price.

You may be able to increase sales by bundling your items — selling multiple items together, as a package deal.

Knowing when to raise your prices

In some circumstances, you need to lower your price. But other times you can charge — wait for it — more. People perceive some products to be more valuable than others — even if, from a practical standpoint, they’re not.

Consider how some painters command stratospheric prices for their paintings. It’s not because their raw materials were substantially more expensive — paint and canvas cost pretty much the same for everybody. And it’s not that their paintings took longer to create. No, these paintings are insanely expensive because the public perceives them to be valuable.

When pricing your items, try taking advantage of this notion of perceived value and position your pieces as premium products. Maybe you employ exceptional materials in crafting your piece. Or maybe you use a unique technique that makes your piece especially durable. Buyers will also perceive your work as more valuable if you’ve developed a reputation as an artist by showing your pieces at galleries or gaining publicity in some other way.

Sometimes just tagging your piece with a higher price can make buyers perceive it as more valuable. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should offer some useless doodad at an outrageous price. (Remember the million-dollar hot dog we mention earlier in this chapter?) People will see right through that ploy. But if you offer an item that’s beautifully crafted and truly special, you may be able to capitalize on this perception phenomenon.

If demand for an item you sell is so high that you simply can’t keep up, it may be an indication that you’ve priced it too low. On the flip side, when items don’t sell, many shop owners assume it’s because they’re priced too high. However, it may also be the case that your price is too low. Before you start slashing prices in your store, try raising them. You may be pleasantly surprised by the result!

Something Old: Pricing Vintage Items

If your Etsy shop specializes in the sale of vintage goodies rather than handmade items, you can forget about everything we’ve discussed so far in this chapter. No “formula” exists for pricing these types of items. Instead, you must rely on your knowledge of the piece. Specifically, you want to be armed with the following information:

- What is the piece? Obviously, you want to know what, exactly, you have for sale.

- How old is the piece? Older pieces tend to be more valuable than newer ones — especially if they are in good condition.

- What company manufactured the piece? Certain manufacturers are held in higher esteem than others. That’s why a Tiffany lamp is a lot more valuable than one made by another company and can command a much higher price.

- What condition is the piece in? Clearly, an item in good condition can command a higher price than one that appears to have passed through a farm thresher.

- How desirable is the piece? Items that are rare or highly collectible generate much more interest than run-of-the-mill pieces.

- How much did it set you back? Assuming you bought the item (instead of, say, unearthing it in your Aunt Mildred’s attic), take into account how much you paid for it, as well as any costs you incurred to find it, research it, clean it up, fix any broken bits, and so on.

If you’re still not sure where to start, try scoping out the competition. Search Etsy (or even eBay) to see whether any other sellers have listed something similar, and if so, for how much. Assuming your piece is in the same basic condition, you can price your item accordingly. No current listings? In that case, try using a tool like Etsy Sold. It’s a Google Chrome browser extension that reveals the selling price of items that have already sold on Etsy.

How Low Can You Go? Pricing for Sales

Many businesses use any excuse to run a sale (“It’s Arbor Day! Take 20 Percent Off!”) in an attempt to draw in loads of customers and move more merchandise. Although this may be an effective strategy for mass-market stores, it’s not the best model for your Etsy shop. Running frequent sales not only devalues your work but also trains your customers to buy from you only when you’re running some type of promotion.

That’s not to say, however, that you should never run a sale. For example, you may run a once-a-year sale to celebrate your store’s anniversary, or a twice-a-year sale to move seasonal inventory. Another idea is to create a permanent “sale” section in your Etsy shop for discontinued, seasonal, or experimental pieces. Or you can generate coupon codes for potential or valuable customers. (Etsy makes generating coupon codes easy, as you see in Chapter 14.)

When you do run a sale, you want to ensure that you still turn a profit on your items — or at least break even. Fortunately, you can easily do so if you use the formula outlined earlier in this chapter to price your goods and list them at the retail price. You can then discount them and still make money.

Underestimating the value of your work doesn’t just hurt you; it hurts everyone who’s trying to earn a living selling handmade goods. Deflated prices are bad all the way around!

Underestimating the value of your work doesn’t just hurt you; it hurts everyone who’s trying to earn a living selling handmade goods. Deflated prices are bad all the way around! If you’re collaborating with others, you want to make sure that you include the cost of their labor as well!

If you’re collaborating with others, you want to make sure that you include the cost of their labor as well!