Every Saturday morning, for as long as I can remember, my parents have gone up the street to the local newsagent to buy a ticket for the Big One, Australia’s multi-million-dollar national lottery draw. They also get themselves a few ‘scratchies’ – little cards which offer instant cash prizes if the silver boxes you scratch off are matching. When I lived in lottery-obsessed Spain, on almost every street corner there was a blind man or woman selling tickets, and the nation stopped on 22 December to hear the winning numbers for El Gordo, the Fat One, the biggest lottery on the planet. Such rituals have occurred all over the world since the invention of public lotteries in the Netherlands in the fifteenth century, where they became grand civic occasions to raise funds for building mental asylums and old-age homes.1 We have long lived in hope that the ancient goddess Fortuna will spin her Wheel of Fortune in our favour and deliver not love, friendship or job satisfaction, but something possibly more alluring: money.

Why do we care so much about it? Clearly because it can be used to satisfy our basic needs – food, clothing, shelter – in an age when few of us are self-sufficient or live off the grid of modern society. But money is also attractive because of a unique quality: it is frozen desire.2 It possesses a versatile ability to transform itself into our myriad wants and cravings. Money can be used for anything from purchasing an antique hunting gun to buying sex from a prostitute, from having a tummy tuck to investing in private education for our children. The dreams of every lottery-ticket holder are built on the belief that wish fulfilment is a financial affair.

Despite being universally coveted, money has often had a bad reputation. Aristotle was convinced that the pursuit of money was not a route to the good life, a point he illustrated with the fable of King Midas of Phrygia, who was granted his wish of having everything he touched turn to gold. In one version of the story he starves after trying to eat and drink. In another he touches his daughter and she turns into a statue. Greed for wealth can indeed have a deadly effect on our relationships. Every major faith warns against excessive riches. ‘It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God,’ declares the Bible – although this does not prevent popes from living in palaces or property tycoons being devout believers. In Dante’s Divine Comedy, written in the fourteenth century, the usurers were cast deep into Hell alongside the sodomites. Many think today’s banking bosses deserve a similar fate. While the lust for money has always been present, almost every culture has given birth to sects and movements which have rejected the material values associated with money, and extolled the virtues of living more simply and sharing wealth more equally.

These persistent doubts about money explain why we are unsurprised to read news articles about lottery winners whose lives have been wrecked by their good fortune. There are stories of marriages falling apart, vicious inheritance battles, friends suddenly having dollar signs in their eyes, drug addiction. A life of promised luxury often turns out to be stressful, boring or lonely. And we admire those winners who give all their windfall away to charity or who endeavour to maintain their old habits and values, like the British woman who kept up her job selling household products door-to-door despite having become a millionaire. ‘People think I’m crazy to still do my job, but the truth is I love it,’ she said. ‘It’s all about people. Money doesn’t make you happy, people do.’3

The contrasting views of money as a source of personal fulfilment or as a road to misery and sin raise questions about what kind of relationship we should have with it. How much money do we really need to live wisely and well? How does it shape the way we work, our ethical priorities and our sense of who we are? How can we feel more in control of money, and less dependent on it? Unravelling these issues calls for exploring two mirror-image aspects of the history of money: how consumerism became the dominant ideology of our age, and whether we can thrive on frugality by becoming experts at simple living. Our starting point is the origins of one of the most overrated inventions of Western civilisation: shopping.

For the first time in history, shopping has become a form of leisure. In Britain it ranks just behind television as one of the top leisure pursuits. But if indulging in a little retail therapy sounds like a harmless activity, consider that almost one in ten Westerners are addicted to shopping – when they are feeling down or stressed, they go on shopping sprees at their favourite store to help boost their spirits or self-esteem.4 Although we may not enjoy wandering around shopping malls on a Saturday afternoon, most people desire the comforts, conveniences and aesthetics of consumerism. Even if we already own a television, we might be tempted to upgrade to a widescreen TV. We treat ourselves to the latest miniature iGadget. A promotion at work? Maybe it’s time for a new car. Because, as the ads say, we’re worth it. Each year ends with a shopping orgy that would have impressed the gluttonous Romans. We call it Christmas, a commercial festival that gets the average adult spending around £500 on presents and entertainment, while the average child under four receives gifts costing over £120.5

In a consumer society, the most obvious way to express who we are is through what we buy: I shop, therefore I am. Why do so many people – from a range of income groups – own more than a dozen different handbags, sweaters or pairs of shoes? Why might we spend a thousand pounds on a leather sofa when we could buy a perfectly comfortable and sturdy one second-hand for under a tenth of the price? Why do we buy a new shirt rather than repair the old one, and pay so much for haircuts? Though few people openly admit to it, most of us want to be seen as fashionable, and care what others think about our looks, homes and what car we drive. Across social classes, people forge their identities through their purchases. We want to fit in with the crowd, but also sometimes stand out from it, in both cases judging ourselves through the eyes of others. If we felt that nobody could see us, our consumer spending would plummet and we would spend much more time slouching around in our Sunday morning tracksuits. Many people claim their purchases reflect purely individual tastes and that they are not influenced by what is in vogue. But such personal preferences – whether for glossy high heels or a zen-like living space – are often remarkably similar to prevalent fashions. It becomes quite clear when you notice – as I did – that you have the same Habitat sofa as three of your friends. And all of it costs money, even if we avoid the most exclusive brands or pride ourselves on getting bargains.

This consumer culture is a recent development. The idea of shopping as a leisure activity or therapy cure would have made little sense in pre-industrial Europe. Naturally, people bought what they needed for daily life, but shopping itself was not considered a route to personal fulfilment or self-realisation. In fact, until the middle of the eighteenth century the word ‘consumer’ was a pejorative term meaning a waster or squanderer, just as ‘consumption’ was a disease which wasted away the body.6 It is only since the early twentieth century, writes William Leach, a historian of shopping, that we have become ‘a society preoccupied with consumption, with comfort and bodily wellbeing, with luxury, spending and acquisition, with more goods this year than last, more next year than this’.7 The result is that we confuse the good life with a life of goods. There may be no greater cause of life dissatisfaction amongst the affluent citizens of the Western world. How this happened is one of the most important episodes in the history of our relationship with money.

The rise of shopping can be traced to new attitudes to wealth that emerged in the early modern period, between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.8 Prior to this time, the vast majority of people were far more preoccupied with avoiding poverty than getting rich, and those who sought to accumulate wealth were often viewed with suspicion or hostility. Gradually, however, acquiring wealth became a widespread personal ambition. In 1720 Daniel Defoe visited Norfolk and found every man ‘busy on the main affair of life, that is to say getting money’.9

One reason for this cultural change may have been the appearance of the Protestant ethic in the sixteenth century, which taught that going into business was a perfectly godly career move. More important was a seismic shift in economic thought in the seventeenth century, when economic and philosophical writers increasingly claimed that human beings naturally seek to maximise their material self-interest, and that by doing so society in general would benefit – the economic pie would get larger for everyone.10 A century later these ideas, central to the capitalist ethic, became the building blocks of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

This new model of economic man, which was supported and spread by interested parties such as merchants, socially legitimised the pursuit of riches and was the engine of a consumer society. As credit became more readily available and the bank accounts of the elite burgher class grew, they had the disposable incomes to buy more and more luxury goods. Shopping as we know it was born. By around 1700 the traditional town markets were giving way to a flood of shops – individual retail outlets with their own premises, which were open most of the week rather than only operating at intervals like the markets. You could walk into a store in London or Paris and be spellbound by the elaborate display of exotic teas from China, sumptuous upholstered furniture and looking glasses with bone handles. Wander around the streets near the Plaza Mayor in Madrid, and you would find fine cloths being sold on the Calle Nueva and jewellery merchants running along the Calle Mayor. Travel to Venice and you could head straight for the opulent shops of the Marzaria, a narrow lane between Piazza San Marco and the Rialto, which is still home to ostentatious retailers like Gucci and MaxMara.

The consumer revolution was even open to craftworkers, tradesmen and farmers, who might be able to afford small luxuries like pottery, needles, gloves and linen. They started imitating the incipient bourgeoisie by dividing their homes in two. Half was filled with ‘front-stage’ goods including pewter jugs and soft furniture to impress visitors, while ‘back-stage’ goods were used for everyday living. Today some people retain this practice by having a separate sitting room used only for guests or special occasions.

The result of these changes, writes the historian Keith Thomas, was a new culture of ‘limitless desire’ in which being a consumer was increasingly considered a way of life. More than this, social status was undergoing a fundamental shift. Honour and reputation were no longer primarily based on having noble blood or being a fine swordsman. Instead, status became fused with the display of wealth. Being conspicuous with your consumption – parading around in your fashionable hat or using special crockery for visitors – was developing into a way of feeling good about yourself.11 Important though these changes were, by the end of the eighteenth century consumerism was still not nearly as culturally dominant as it is in our own time. To understand how it became so, we must explore the next phase in the history of shopping: the rise of department stores.

On 9 September 1869, Aristide Boucicaut, the son of a Norman hatter, stood at the junctions of the sixth and seventh arrondissements in Paris. Unnoticed by most passers-by, he bent down and laid the foundation stone of what would soon be hailed as the greatest department store in the world, the Bon Marché. In that single act, he launched a new era in which consumerism became such a powerful social force that it radically altered our conception of the good life.

The invention of the department store in the nineteenth century transformed shopping. Through the use of sophisticated marketing techniques that had been absent in the pre-industrial period, shopping became the all-embracing wrap-around entertainment experience that we know today. With its panoply of products in a single immense building, the department store created a fantasy land away from the filthy streets, where the virgin culture of limitless desire could run rampant. Bon Marché was the largest and most fantastic of them all. It was bigger than Macy’s or Wanamaker’s in the United States, and dwarfed British efforts such as Whiteleys and Harrods. When Émile Zola decided to write a novel about this extraordinary new form of retailing to represent what he ironically called ‘the poetry of modern activity’, he based the story on Bon Marché.

Boucicaut, the founder of the store, was born in 1810. After working his way up the ladder in several Parisian retail outlets, in 1863 he became owner of an inconspicuous Left-Bank shop named Bon Marché – which roughly translates as ‘the good deal’. But he soon realised that his growing operation needed new premises, so in 1869 he commissioned a grand building whose colossal structure was masterminded by an upcoming young engineer, Gustave Eiffel, who two decades later would design a landmark tower for Paris to mark the 1889 Universal Exposition.

What made Bon Marché such a phenomenal success and one of the most innovative capitalist enterprises in Western history? Like other department stores in the nineteenth century, its ambition was to democratise luxury – to use the advantages of bulk purchasing and mass manufacturing to keep prices affordable so that consumer items which had previously only been available to the elite could be bought by the expanding middle classes. Boucicaut’s genius was using clever salesmanship and marketing to make shopping not just convenient, but a form of pleasure.

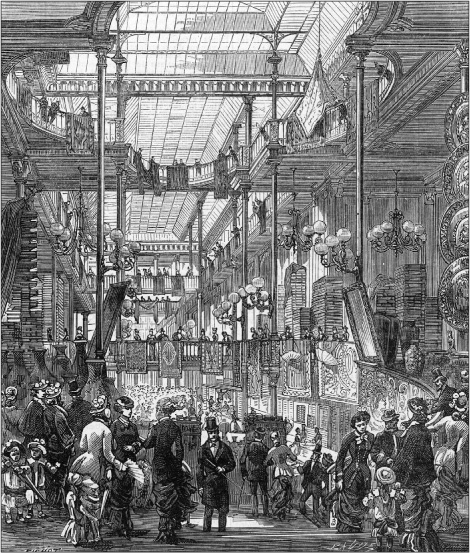

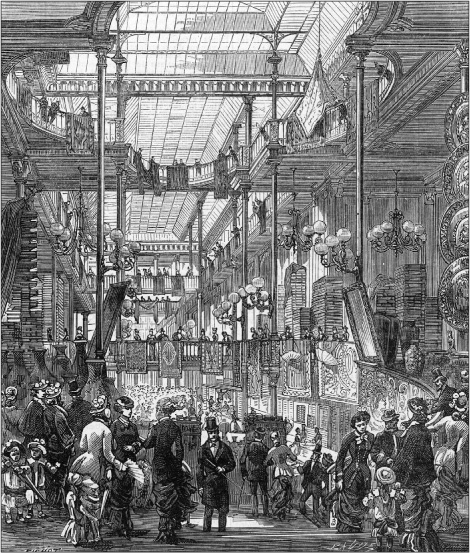

According to Michael Miller, the historian of Bon Marché, the store was ‘part opera, part theatre, part museum’.12 The shopping experience began with the architecture. Visitors were stunned by Eiffel’s ornate iron columns and vast panels of glass. There were sweeping staircases leading up to balconies where you could become a spectator watching the stage set below. Under superb lighting, sumptuous merchandise was displayed for all the world to see. Oriental silks cascaded from the walls, Turkish rugs were draped over the bannisters. Shoppers were lured into the store with bargain counters just inside the door. By squeezing them through narrow passageways, Boucicaut created the illusion of frenzied crowds clambering for his goods. Tens of thousands came for the famous White Sale in early February, when white sheets, towels, curtains and flowers filled every display. Combined with the summer fashion sale in April and the furniture sale each September, Bon Marché created a new calendar for Parisians, just as the revolutionary government had done in 1793 by giving the months new names such as Brumaire, Germinal and Thermidor. If you’ve ever been to a January clearance sale, you can thank Monsieur Boucicaut for the privilege.

Bon Marché was not just a shop. It was a leisure complex. There was a reading room where you could peruse the latest journals and newspapers, a Grand Hall containing free art exhibitions, classical music performances where up to seven thousand people could come to see the city’s opera stars, and a huge restaurant bustling with liveried waiters. People made a day trip out of visiting the store, buying, eating, drinking and meeting friends. For many bourgeois women, Bon Marché became the centre of their social lives, an escape from the confines of the domestic household. Shopping had never been so easy or enjoyable. Unlike small local shops in Paris where you were expected to haggle over the price, Bon Marché had fixed prices and you could wander its magnificent halls without being accosted by sales assistants. To help people absorb the opulence, there was a guided tour of the premises each afternoon at three. And to ram home the message that Bon Marché was as much a public monument as Notre Dame or the Louvre, the management gave away printed maps of France on which Paris was represented by a picture of the store.

Bon Marché may have been described as a ‘bewitching palace’ by its customers, but it was also a hard-nosed business. It succeeded in the ultimate objective of the consumer age, which was to manufacture new kinds of desire – to get people to buy things they had never imagined they needed. In doing so it set new standards for bourgeois respectability. Browse through the store’s mail order catalogue and you would discover that women should have not just one coat but a whole range for different occasions – one for visiting friends, one for travel, a coat for the theatre and still another for attending a ball. A respectable home should have a variety of forks for every purpose: eating meat, fish, oysters, olives and strawberries. And don’t forget special spoons for soup, dessert, sugar, salt and mustard. Your house should have an abundance of bedsheets, patterned curtains, and a separate dining room where you placed a fine set of dishes on a table cloth accompanied by matching linen serviettes. New outfits would be required for seaside holidays and playing tennis. Children should have a little sailor suit at hand for days out. The catalogues and other forms of advertising spread these fashions and tastes amongst white-collar workers and throughout the provinces, with a consequent homogenising effect on French society. Bon Marché – which still exists today, although somewhat less grand – not only reflected bourgeois consumer culture, but helped to create it. Soon it had imitators across the globe eager to create their own empires of desire.13

We are direct descendants of all those customers who poured through the doors of Bon Marché in the nineteenth century. Our shopping malls, with their retail outlets and eateries, cinemas and children’s play areas, are faithful to the Bon Marché tradition, in which shopping and lifestyle are merged into one. This fusion has utterly transformed the art of living, in three different ways: by promoting consumer values, by deepening status anxiety, and by robbing us of personal freedom.

We must recognise, first, that our consumerist habits are much less of our own choosing than we like to imagine. ‘The culture of consumer capitalism may have been among the most nonconsensual public cultures ever created,’ argues the social historian William Leach.14 He and other historians of shopping have shown how corporate retailers, from Bon Marché to Coca-Cola, have gradually forged this culture over the past hundred and fifty years. One of their main tools for doing so has been advertising. Those early Bon Marché catalogues have since metamorphosed into an incessant barrage of enticing images to make us spend our money. Whether on television, in magazines, on billboards or online, we are subject to constant assault. See enough images of a beautiful couple relaxing in a spacious home with stylish Scandinavian furniture, sleek laptops, minimalist light fittings and wearing earthy organic clothes, and we eventually come to believe that this world is valuable and what we should aspire to. We want to become like them. John Berger described this power of consumer advertising a generation ago in Ways of Seeing:

The main staircase of Bon Marché, around 1880. The department store was ‘part opera, part theatre, part museum’.

Publicity is not merely an assembly of competing images: it is a language in itself which is always being used to make the same general proposal. Within publicity, choices are offered between this cream and that cream, that car and this car, but publicity as a system only makes a single proposal. It proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more. This more, it proposes, will make us in some way richer – even though we will be poorer by having spent our money.15

We also become spiritually poorer. Consumerism encourages us to define freedom as a choice between brands. It asks us to express who we are through the language of products, while at the same time shaping our ideals of what it is important to own. The good life becomes a matter of satisfying consumer desires to the detriment of alternatives like spending time with our families, enjoying our work or living ethically. Our values become material values. This is a historical legacy that few of us have escaped and none of us can ignore. Whenever we purchase anything beyond our essential needs, we should ask how we have come to acquire this desire. Can we honestly say that it is a free choice, or should we admit that the marketeers at Nike, Gap, L’Oreal or Ford have something to do with it? And if the latter is true, are we satisfied to accept the vision of the good life they have manufactured for us?

The rise of shopping has also produced a second difficulty, that of ‘status anxiety’, a term popularised by the writer Alain de Botton. Since at least the eighteenth century our sense of self-worth and standing in society has become intimately tied to what we earn and how we spend it. Money has been endowed with an ethical quality, he writes, so ‘a prosperous way of life signals worthiness, while ownership of a rusted old car or a threadbare home may prompt suppositions of moral deficiency’.16 If we fail to display financial success, to wear the right clothes or drive the right car, we feel diminished in the eyes of the world, a lesser person. And that matters to most of us.

In an effort to avoid status anxiety and enjoy the comforts and pleasures of a consumer lifestyle, we embark on a quest to accumulate material possessions and luxury experiences, just as Aristide Boucicaut would have advised us to do. But psychology research over the past two decades has shown that this is an unlikely path to human fulfilment for all but those at the lowest income levels. The happiness gurus tell us that once national income reaches £12,500 a head, further rises in income do not contribute to higher life satisfaction.17 In other words, buying more consumer products does not increase our level of personal wellbeing in the long term: after treating ourselves to a sports car it will immediately spike up but then settle down to its earlier level. This is a pattern familiar to drug addicts. Purchasing a new car, or a holiday home in the South of France, or a Dolce & Gabbana suit, just doesn’t make that much difference to most people’s wellbeing.

Part of the problem is that as we get wealthier, money begins to warp the relationship between our wants and needs. We come to believe we ‘need’ a winter holiday in the sun or a kitchen extension, and are rarely satisfied with what we’ve got. That’s why an astonishing 40 per cent of Britons with incomes over £50,000 a year – that is, in the top 5 per cent of earners – feel that they cannot afford to buy everything they really need.18 We then find ourselves working harder and harder to earn the money to satisfy our consumer desires, and ratchet up our levels of personal debt in the process, but in return fail to receive the benefits we had imagined. This may leave us with a discontented yearning for even more luxuries, keeping us on a treadmill that ultimately breeds anxiety and depression. Adam Smith recognised the dangers of consumerism in the eighteenth century. The pleasures of wealth, he said, produce ‘a few trifling conveniences to the body’ but leave people just as exposed ‘to anxiety, to fear, and to sorrow; to diseases, to danger, and to death’.19 Nike might tell us to just do it, but when it comes to shopping we would be wise to ask, why do it?

Even if you have an unusually steely mind that is immune to the influence of the advertising industry and the dilemmas of status anxiety, the history of shopping has left us with a third problem which has a devastating potential to drain away our personal liberty. It was identified in the 1850s by the naturalist Henry David Thoreau. ‘The cost of a thing,’ he wrote, ‘is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.’20 In Thoreau’s view, the cost of that new leather jacket you bought was not the price written on the tag – it was the three days of your labouring time needed to purchase it. Buying a sofa might cost twenty days, and a car three hundred. We pay not with our wallets but with the precious days of our lives.

Perhaps you love your job so much that you don’t mind working extra hard to meet the financial demands of your shopping wish list. But only a minority can honestly make this claim: most people say they would rather work less if they could. When we buy ourselves the latest iPod, go for a big night out or take on a hefty mortgage, we should instinctively calculate the number of hours or days we will have to work in order to pay the bill. The figures can be alarming. Consumer culture is asking us to exchange days of our lives as the price of membership. But is each of our Faustian shopping bargains really worth it?

The answer is a clear ‘no’, according to Thoreau. He believed that the path to a fulfilling and adventurous life lay not in shopping till you drop, but in discovering the pleasures of an unmaterialistic lifestyle that offers an abundance of free time. As we shall see, he was a prime mover in efforts to create an alternative to the addictions of consumerism, and helped turn simple living into an art form.

If we think we are affluent, we’re wrong. That’s according to anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, who in the 1970s argued that the truly affluent societies were hunter-gatherer communities. Our desire for consumer products compels us to spend most of our waking hours working to pay for them, leaving us with little free time for family, friends and idle pleasures. But Aborigines in Northern Australia and !Kung indigenous people in Botswana worked only three to five hours a day to support themselves, and, Sahlins points out, ‘rather than a continuous travail, the food quest is intermittent, leisure abundant, and there is a greater amount of sleep in the daytime per capita per year than in any other condition of society’.21

This may have been an excessively rosy depiction of what in reality was a difficult and precarious existence, where food was often far from abundant and famine never far from the mind. There is nothing enviable about poverty. Nevertheless, Sahlins’ point is still pertinent: once we have met our subsistence needs, we might be better off if we lived more simply and on less money. This is especially relevant in an age when working hours are on the increase and many people feel their jobs are robbing time from other parts of their lives. Our current predicament is odd, since the Victorians believed that working hours would progressively diminish as productivity rose, so that the great dilemma for future generations – for us – would be how to occupy our leisure time. As the economist John Maynard Keynes put it in an optimistic essay written in 1930, ‘Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren’, the primary challenge facing mankind in the future would be ‘how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely, agreeably and well’.

If only he had been right. It is certainly true that from around 1900 until the 1980s working hours did fall in both Europe and North America. But in the past two decades this trend has reversed. In 1997 the US surpassed Japan as the country with the longest working hours in the industrialised world, with an average of forty-seven hours a week.22 Across Western Europe working hours are going up, particularly in the UK. The typical full-time employee in the EU works forty hours a week, whereas for the UK the figure is forty-four hours, and UK employees are more likely than the Swedes, French or Danes to be working over fifty hours a week.23 These figures also fail to register the way work follows us home much more than in the past: Keynes had no idea that we might spend our weekends constantly checking our phones for an urgent work message. Although Westerners are now working far fewer hours than in the nineteenth century, and also compared with factory labourers in developing countries, surveys consistently show that many feel they are working too hard and too much. This is in part because they have noticed their own working hours rising over a relatively short time period, but also because of heightened stress levels, as employees are expected to get more and more done within increasingly tight deadlines. One-third of Canadians, for instance, describe themselves as workaholics.24

A simpler, less costly lifestyle may be the most effective form of liberation from our culture of overwork, as well as from the dilemmas of status anxiety and our addiction to shopping. But if we want to wean ourselves off consumerism and train ourselves up as experts at simple living, how might we go about it? What inspiration can we draw from the past, so that simplicity is not a matter of scrimping frugality but rather a way of making our lives more beautiful and purposeful?

Simple living has a venerable history in nearly every major civilisation. Socrates believed that money corrupted our minds and morals, and that we should seek lives of material moderation rather than douse ourselves with perfumes or recline in the company of courtesans. When the shoeless sage was asked about his frugal lifestyle, he replied that he loved visiting the market ‘to go and see all the things I am happy without’. His pupil, the Cynic philosopher Diogenes – son of a wealthy banker – held similar views, living off alms and making his home in an old wine barrel. Jesus continually warned against the ‘deceitfulness of riches’, and devout Christians soon decided that the fastest route to Heaven was imitating his simple life. Many followed the example of St Anthony, who in the third century gave away the family estate and headed out into the Egyptian desert where he lived for decades as a hermit, creating a vogue for desert monasticism.

Undoubtedly some have approached simplicity as a quaint affectation: Marie Antoinette constructed a toy village at Versailles where she could temporarily escape lavish court life by dressing in peasant garb and milking perfumed cows next to a picturesque watermill. Such pretence has been more than matched by hard-core simple livers like Mahatma Gandhi, who spent decades in rural communes practising self-sufficiency, making his own clothes and growing vegetables, while simultaneously attempting to overthrow the British Empire. In nineteenth-century Paris, bohemian painters and writers like Henri Murger – author of an autobiographical novel which was the basis for Puccini’s opera La Bohème – valued artistic freedom over having a sensible and steady job, living off cheap coffee and conversation while their stomachs growled with hunger.25 For all these individuals simple living was a personal choice driven by a desire to subordinate the material to the ideal – whether that ideal was based on ethics, religion, politics or art. They all believed that embracing something other than money could lead to a more meaningful and fulfilling existence.

The last place one might expect to find a strong tradition of simple living is in the home of material excess and worship of Mammon, the United States. Yet it has been a site of radical experiments in simplicity for over 400 years. The search for alternatives to consumer capitalism, and ideas for adopting a simpler life, lie within this hidden history.

Colonial America was a refuge for religious radicals fleeing persecution in Europe and intent on establishing a holy life in the New World. Best known were the pious Puritans who preached simplicity and wouldn’t permit the playing of music, games of chance or other immoral activities in their homes. But the real radicals were the Quakers – officially the Religious Society of Friends – a Protestant sect whose followers began settling in the Delaware Valley in the seventeenth century. As well as being pacifists and social activists, they believed that wealth and material possessions were a distraction from developing a personal relationship with God. The early Quakers were fanatical about what they called ‘plainness’. It was easy to spot them: they wore unadorned dark clothes without pockets, buckles, lace or embroidery. Sumptuary guidelines issued in 1695 decreed that ‘none Wear long lapp’d Sleeves or Coats gathered at the Sides, or Superfluous Buttons, or Broad Ribbons about their Hats, or long curled Periwigs … and other useless and superfluous Things’.26 Plainness was also sought in speech. They refused to address people by their honorific titles, and used the familiar ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ instead of the more respectful ‘you’. They even objected to the names of the months and days of the week because they referred to Roman or Norse gods such as Mars (March) and Thor (Thursday). So January became ‘First Month’, February ‘Second Month’, while Sunday was ‘First Day’, Monday ‘Second Day’, and so on.

Plain and simple dress at a Quaker meeting around 1640. Religious guidelines forbade the wearing of fancy clothing with lace, ribbons or buckles. Quakers today follow the spirit of this tradition by avoiding clothes which display corporate designer labels.

The worship of simplicity did not last long. As with the Puritans, many Quakers found the temptations of the land of plenty too much, and started up successful businesses and indulged in proscribed luxuries. One of their most eminent members was William Penn – founder of Pennsylvania – who converted to Quakerism at the age of twenty-two. Although declaring, ‘I need no wealth but sufficiency’, he managed to live like an aristocratic for the next fifty years, until his death in 1718. Penn didn’t have just one wig, he had four. He also owned a stately home with formal gardens and thoroughbred horses, which was staffed by five gardeners, twenty slaves and a French vineyard manager. This was hardly a good example for orthodox Quakers, who rejected not only material wealth but also the institution of slavery.

In the 1740s a group of determined Friends led a movement to restore Quakerism to its spiritual and ethical roots in plainness and piety. Its leading figure was a farmer’s son named John Woolman. Today largely forgotten, he has been described as ‘the noblest exemplar of simple living ever produced in America’.27 Woolman did not have a brilliant intellect or fine oratory skills. The power of his message came from the fact that he was a humble and humane man who lived by his beliefs. He did far more than wear the traditional undyed clothes and hat of the first Quaker settlers. After setting himself up as a tailor and cloth merchant in 1743 to gain a subsistence living, he was soon faced by a dilemma: his business was too successful – he felt he was making too much money. In a move not likely to be recommended in any business school today, he set himself the task of reducing his profits, for instance by trying to persuade his customers to buy fewer and cheaper items. But that didn’t work. So to further diminish his income, he abandoned retailing altogether, and supported his family with a little tailoring and tending an apple orchard.28

Woolman was a man of principle. On his travels, whenever receiving hospitality from a slaveholder, he insisted on paying the slaves directly in pieces of silver for providing the comforts he enjoyed during his visit. Slavery, he said, was motivated by ‘the love of ease and gain’ and no luxuries could exist without others having to suffer to create them.29 In an early example of ethical shopping and fair trade, Woolman boycotted cotton goods because they were produced by enslaved workers; today he would surely refuse to buy cheap clothes made in Asian sweatshops. After years as a pioneering campaigner against slavery, in 1771 he learned of the poverty being caused by the enclosure of common lands in England, and decided to travel there as a missionary. But upon boarding the ship he was so disturbed by the excessively ornate woodwork in his cabin that he spent the next six weeks sleeping in the steerage with the sailors, sharing ‘their exposure, their soaking clothes, their miserable accommodations, their wet garments often trodden underfoot.’30 After arriving in London, he felt compelled to visit Yorkshire, where he had heard social conditions were harshest. Yet once he discovered the cruelty inflicted on the horses used for the stagecoach trip, Woolman, characteristically, decided to walk – a distance of over 200 miles. Not long after the exhausting journey he contracted smallpox. The disease soon killed him. He was buried in York, wrapped in cheap flannel in a plain ash coffin.

Today John Woolman appears as somewhat eccentric, even foolhardy for his cause. But his story is instructive. It certainly shows that simple living is far from the easiest option in life. If you’re not ready to sacrifice a few luxuries and creature comforts like travel in horse-drawn carriages, then simplicity is probably not for you. It also helps to be driven by something larger than self-interest, as Woolman was by his religious ethics. Is there some framework of belief – such as social justice or low-carbon living – that can act as a beacon guiding our actions and keeping us from temptation? Perhaps the greatest lesson emerges from one historian’s conclusion that Woolman ‘simplified his life in order to enjoy the luxury of doing good’.31 For Woolman, luxury was not sleeping on a soft mattress but having the time and energy to engage in social work, such as the struggle against slavery. That was his route to personal fulfilment. Simple living is not about abandoning luxury, but discovering it in new places.

Nineteenth-century America witnessed a flowering of utopian experiments in simple living. Many had socialist roots, such as the short-lived community at New Harmony in Indiana, established in 1825 by Robert Owen, a Welsh social reformer and founder of the British cooperative movement.32 Others were inspired by the Transcendentalist philosophy of the poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, who preached material simplicity as a path to spiritual truth, self-discovery and union with nature. While the Quakers lived out their ideals in a religious community full of rules and regulations, the Transcendentalists were much more apostles of individualism. The most famous of them, who remains an icon for simple livers across the world today, was a rather prickly character with a liking for bad puns and civil disobedience, Henry David Thoreau.

After completing his studies at Harvard in 1837, Thoreau rejected traditional career paths like business or the Church, working instead as a teacher, carpenter, mason, gardener and surveyor. He despised the growing commercialism in New England, and was incensed when in an attempt to buy a blank notepad for his poetic thoughts, all he could find was a lined ledger for financial bookkeeping. Money was colonising the American mind. Thoreau’s response was to become an advocate of ‘simplicity, simplicity, simplicity’. His big break came in 1845, when Emerson offered him use of some land at Walden Pond, near the town of Concord, Massachusetts, where he could put his ideals to the test.

For two years Thoreau lived alone in a ten by fifteen foot woodland cabin he built himself for a cost of only $28.12 – less than what he paid for a year’s rent at Harvard. It contained little more than a bed, a desk, a few chairs and some favourite books. ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,’ he recorded in Walden.‘I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.’ As part of his experiment in self-sufficiency, he grew beans, potatoes, peas and sweetcorn, which provided for most of his meals. Selling the surplus earned him enough money to buy staples like rye, Indian meal and salt, from which he made unleavened bread. Occasionally he caught fish for his dinner and once roasted a mischievous woodchuck that had ravaged his bean field.

Despite the long frozen winters and sparse surroundings, Thoreau relished the experience and spent his time writing, reading and observing nature. Each day began with an invigorating and restorative plunge into the pond, often followed by an entranced immersion in the surrounding wildlife:

Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in revery, amidst pines and hickories and sumachs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness, while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house … I grew in those seasons like corn in the night.

Out of these quiet mornings and attempts at self-sufficiency grew his philosophy of simplicity. ‘I am convinced, both by faith and experience, that to maintain oneself on this earth is not a hardship but a pastime, if we will live simply and wisely,’ he wrote. ‘A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.’ While the Quakers preached austerity and abstinence, Thoreau’s innovation was to show how simple living could be uplifting and enrapturing in its beauty.

Thoreau’s adventure now appears a utopian dream: we can’t all just go off and build a hut in the wilderness (especially on a friend’s land). But Thoreau never thought that simple living meant abandoning civilisation. In fact, his cabin was only a mile from Concord, and as he openly admits in Walden, he went there every few days to hear the local gossip and read the papers. Thoreau was a pragmatist who believed we could learn to turn our backs on the money economy while staying within the company of everyday society. Our real task was to avoid the lures of consumerism and indulge in low-cost pleasures like watching the sunset, talking to interesting people, reading the classics, and thinking.

The most vital lesson from Thoreau concerns work. He should be remembered as one of North America’s supreme masters of idling. His sojourn at Walden Pond was less a spiritual quest than an effort to learn to live on as little money as possible so as to minimise his labouring hours and maximise his leisure time. And in this he succeeded. After returning to live in Concord, he worked as a part-time surveyor, which left him ample hours for nature walks, writing and reading. He claimed that in six weeks he could earn enough to live on for an entire year. Today, the inheritors of his legacy are not so much those who live alone in the wilderness but town and city dwellers who have been disciplined enough to cut back their expenses so that they only need to work three or four days a week. Like Thoreau, they have discovered that simplicity is a route to gaining what in the overworked West has become one of the most valuable forms of affluence and wealth: time itself.

The history of simple living in the United States does not end with Thoreau. There were the hippy communes of the 1960s, followed by the rise of an ecologically conscious anti-consumerist movement in the 1970s drawing its inspiration from cult books such as E. F. Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful (1973), which argued that our aim should be ‘to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption’. Many of its adherents became advocates of ‘voluntary simplicity’, a philosophy which promotes conscientious rather than conspicuous consumption, and a life that is ‘outwardly simple, inwardly rich’.33 But as we sit here in the twenty-first century, we need to ask what steps we could take in order to lead such an existence. Can we really live deep and suck all the marrow from life without having to constantly take out our wallets?

The most practical starting point is to follow Thoreau and cut back on everyday consumer spending. If he were alive today, I am quite sure he would buy most of his clothes secondhand from charity shops. I can see him burrowing around for kitchen utensils in flea markets, yard sales, and at car boot sales, that peculiarly British gathering where people sell their used household goods – anything from baby clothes to bicycles – at knock-down prices out of their cars. He would grow most of his vegetables on his allotment, support the local farmers’ market and rarely eat out in restaurants, preferring to entertain around his kitchen table. His home would have a rustic beauty, containing furniture made with his own hands from reclaimed wood plucked out of nearby skips. What he couldn’t make himself would be found on websites like Freecycle, where people give away belongings they no longer want. I imagine he would be living on a canal boat or in a tenant-run housing cooperative rather than in a large home in a fashionable suburb, eager to avoid the burdens of a big mortgage. Thoreau would probably have a solar-powered laptop, and use free Open Source software like OpenOffice, rather than pay Microsoft for the privilege of typing his words. He would get around by bike and public transport, having long since sold the car his parents bought him as a graduation present. His holidays would be a walking trip in a national park accessible by train, rather than a beach vacation in Sri Lanka. He would vow never to work more than twenty-four hours a week. And the main financial question of his life would not be, ‘How much money would I like to earn?’ but rather, ‘What is the minimum I need to live on?’34

It is understandable that in a culture geared towards enjoying consumer luxuries, and where social standing is so closely related to displays of wealth, many people are reluctant to embrace a more thrifty way of life. We want our children to wear new, pristine clothes, suspecting that those from a charity store are a bit shabby and smelly. We want our friends or colleagues to admire our tasteful homes, and are pleased when somebody comments on our stylish haircut. For most of us, status anxiety is a shadow obscuring the possibilities for simple living. We can hardly help but want to keep up with the Joneses, whether they are neighbours, workmates, old school pals or some idealised family invented by the advertising industry or TV that lurks in the back of our minds. The bohemian writer Quentin Crisp, who spent most of his life living in a rented bedsit, had a solution: ‘Never keep up with the Joneses. Drag them down to your level. It’s cheaper.’ But the reality is that we probably can’t bring them down to our level. So what can we do? Compare ourselves to people other than the Joneses.

One of the most powerful freedoms we possess is to choose who we compare ourselves to for our sense of social worth. To give a personal example, when my partner and I announced we were having twins, some of our better-off friends said, ‘Oh, you’ll have to move since your house is so small.’ But friends in our neighbourhood said, ‘Well, it’s lucky you live in such a big house!’ Whose perspective were we going to adopt? We had a choice of who would be our peer group and we opted to take our inspiration from friends who thrived with their families in homes no larger than our own. Nobody dictates who each of us selects as our peers. We are even at liberty to imagine they include the ghosts of simple livers from the past like Thoreau, Woolman or Gandhi. I doubt they would worry if you served them a meal on plates that didn’t match.

Simple living is about more than cutting down your daily expenses or rethinking your points of social comparison, however. It is also about community life. Human flourishing is difficult to achieve alone. One of the damaging results of consumerist ideology is that it has encouraged an extreme culture of possessive individualism where we are primarily interested in our own pleasures and looking after Number One. That is why Monopoly is the most popular board game in the West: the sole aim is to accumulate personal wealth and property.35 Fifty-five per cent of Americans under thirty think they will end up being rich. ‘And if you’re going to be rich,’ writes Bill McKibben, ‘what do you need anyone else for?’36 This obsession with self-interest has blinded us to the role that community can play in creating the social bonds that do so much for our sense of wellbeing. We should remember what Aristotle told us – that we are social animals, as gregarious as bees. The problem is that a confederacy of forces including suburbanisation, long work hours, television and the consumer drive itself have eroded civic life across the Western world. We barely know our neighbours, shop in faceless hypermarkets and no longer have time for singing in the local choir. Given the failure of consumer materialism to boost our levels of personal wellbeing, it would be a wise move to reclaim community life.

What many people fail to notice is that doing so can be remarkably cheap. In fact, it can save you money, since you no longer need to derive so much existential sustenance from pricey shopping expeditions. Some community activities I’m thinking of are in part designed to help save money, such as joining babysitting circles, car-sharing clubs or time-bartering networks like Local Exchange Trading Schemes. Others just happen to be low cost, like playing music with friends in your living room, meeting people from different cultures down at your allotment, and volunteering at the nearby hospice or as a leader of a Girl Guide troupe. We become surrounded by a web of human relationships that sustain us at least as much as a weekend away in a plush hotel. It is curious that Thoreau did not stress the importance of community for sucking all the marrow from life. Perhaps this was because he did not feel its absence, living near a small town where he knew so many of the inhabitants when he walked down the main street. But if he could observe our isolated, hyper-individualist lives today, I believe he would recommend a healthy dose of community immersion, which offers the prospects of deep living without requiring regular trips to the hole in the wall.

So we can scale down luxury spending, avoid comparison with the Joneses and rediscover our community roots. But there is one final lesson from the history of money for the art of simple living: to expand the free, moneyless spaces in our lives. Imagine drawing a picture of all those things that make your life fulfilling, purposeful and pleasurable. It might include friendships, family relationships, being in love, the best parts of your job, visiting museums, craftwork, political activism, playing sport and music, volunteering, travel, and people watching. There is a good chance that the most valuable of these cost very little or are even free: it does not cost much to put on a puppet show with your kids or walk along a river with your closest friend. The humorist Art Buchwald said it well: ‘The best things in life aren’t things.’ What Thoreau and other simplicity lovers would suggest is that we should aim, year on year, to enlarge these areas of free and simple living on the map of our lives. Let them take up the space once occupied by expensive foreign holidays or boutique items for our wardrobes.

Reducing the role of money in our lives, and shaking off dependency on it, does not mean that we will be deprived of luxuries. The word ‘luxury’ comes from the Latin for ‘abundance’. We have been taught to think of it in material terms – fine wines, fast cars, first-class travel. But we can also have an abundance of intimate relationships, meaningful work, dedication to causes, uncontrollable laughter and quiet time to be with ourselves. There are no shops which sell such luxuries, nor can they be bought with the winnings from a lottery ticket. Yet these are the luxuries which, ultimately, matter the most to us and constitute our hidden wealth.