How we love to marvel at the senses. The miracle of touch: premature babies who receive regular massages gain weight 50 per cent faster than those who do not. The wonders of smell: the exquisite scent of violets soon fades because it contains ionone, which short-circuits our sense of smell – but a minute or two later the fragrance will return. Or the intrigue of synaesthesia, a neurological condition which creates connections between the senses: for Rimsky-Korsakov the key of C major was white, while for Duke Ellington, a D evoked dark-blue burlap.1

These are the kinds of examples you might find in a book on the science of sense perception, which focuses on the physical and biological aspects of the senses. But our sense experiences are also a product of culture and history. The society we live in teaches us how to use our eyes, ears and other sense organs, shaping our journeys through the doors of perception. Different cultures make sense of the world in their own ways. If you were visiting the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal and met a native Ongee woman, instead of saying, ‘How are you?’, she would greet you with, ‘How is your nose?’ If she wished to refer to herself in the middle of the conversation, she would point to her nose. This is because smell is the most important sense for the Ongee, and odour is considered to be the vital force which holds the universe together.2 In Western culture, by contrast, vision has the place of prominence, which is why so many of our common expressions are based on sight: I see what you mean, that’s my perspective, the mind’s eye, your worldview, what you see is what you get, great to see you. It is unlikely that a hearty ‘Great to smell you!’ would go down well with your new work colleague.

The history of the senses reveals a disquieting truth: many of us live in a state of acute sensory deprivation, a hidden form of poverty that pervades the Western world. Unless we happen to be keen-eared musicians or fine-nosed perfumers, there is a good chance we are failing to cultivate the full range of our sensory faculties. Can you really say that all your senses are highly attuned, that you regularly nourish them and give them the attention they deserve? As you eat your breakfast or walk to work, how alert are you to all the sounds, tastes, textures and scents around you?

Failing to nurture our senses not only detracts from our appreciation of the subtleties and beauties of everyday experience, but also strips away layers of meaning from our lives. Yet curing ourselves of sensory deprivation is not, as you might expect, about indulging in luxuries like dining on truffles or locking ourselves in a dark room and listening to a Beethoven symphony at full volume, exhilarating though this may be. It is much more about gaining a deeper understanding of how our various senses have come to shape, filter and even distort our interactions with the world – and also how culture has moulded our sensory experiences.

What can the past tell us about our ways of sensing? First, we need to challenge the ancient myth that we have five senses, liberating ourselves from its strictures and recognising that we possess several additional senses. Then we must discover how vision has become so dominant amongst the traditional senses during the past 500 years, especially how the eye has exerted tyranny over the ear and nose. At that point we will be ready to seek inspiration from two of the most sensually perceptive individuals in history – one a foundling who was locked away alone in a dark dungeon for most of his youth, the other a brilliant writer who was both deaf and blind. They hold the keys to unlocking the latent power of our sensory selves.

If you share the common belief that there are five senses – sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste – it is time to think again. The five senses are a myth, a historical invention that has been leading us astray for over 2,000 years, leaving us with an excessively narrow conception of what we can sense of the world. How did the five senses become accepted knowledge, who deserves the blame and why does it matter?

In ancient Greece, where the senses first became a subject of sustained discussion, there was no consensus on what they were or how many we had. Plato believed our senses included not only sight, hearing and smell, but also perception of temperature, fear and desire, while taste did not even make it onto his list. In the first century, Philo of Alexandria argued that there were seven senses, one of which was speech, an idea that seems odd to us now, since we think about the senses as passive recipients of data. Yet in the classical era the senses had a more active role and were considered almost as media of communication. The eye, for instance, was thought to send out rays which touched the object it was perceiving, much as words emanate from our mouths.

It is Aristotle who bears responsibility for the doctrine of the five senses. Reflecting the Greeks’ obsession with order and symmetry, he claimed there must be a perfect correlation between the elements and the senses. Since there were five elements – earth, air, water, fire and the mysterious quintessence or ‘fifth essence’ known as ether – there must also be five senses. So he rejected Plato’s suggestions of fear and desire, and condensed the various sensations of temperature, wetness and hardness into the single sense of touch. Adding this to sight, hearing, smell and taste gave him the magic number he wanted. The immense intellectual authority of Aristotle meant that this rather arbitrary theory that there were five physical senses became the standard during the Middle Ages, and has remained so culturally powerful that schoolchildren are still taught it today.3

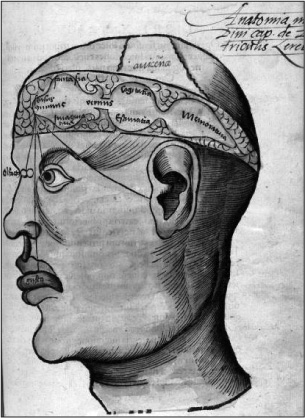

Yet during the Middle Ages a new and more expansive conception of the senses also become popular – one which almost no schoolchild will have ever heard about. This was the belief that in addition to the five ‘outer senses’ identified by Aristotle, there were five ‘inner senses’. These inner senses are now forgotten, but for hundreds of years, until the seventeenth century, they were considered scientific fact. Their most famous proponent was Avicenna, an eleventh-century Persian physician and philosopher, who drew on the theories of the ancient Roman anatomist Claudius Galen to argue that an essential part of our sensory apparatus could be found in the ventricles, three fluid-filled cavities in our heads.

The front ventricle was thought to house the vital sensus communis, the ‘common sense’, an organ which acted like a processing plant, organising the information from the outer senses such as sight and taste, which flowed into it via the nerves. The common sense was needed, for example, to distinguish the perception of whiteness from sweetness. Although this was all anatomical nonsense and we might chuckle at the idea of a ‘common sense’ today, even advanced Renaissance thinkers such as Leonardo da Vinci were firm believers in it. ‘The common sense,’ he wrote, ‘is that which judges of things offered up to it by the other senses.’ Just behind the common sense, within the front ventricle, sat a second inner sense called imagination, where images received from outside were stored. The middle ventricle contained an organ usually known as fantasy, which enabled us to visualise things we had never before seen, such as a golden mountain or a unicorn. Alongside it was instinct, a faculty which, according to Avicenna, would prompt us to run away if we saw a wolf, while the rear ventricle contained the inner sense of memory.

When the English scholar Robert Burton discussed the inner senses in his 1621 treatise The Anatomy of Melancholy, he was particularly keen to warn his readers about the dangers of fantasy. Although it could stimulate poets and painters, during sleep ‘this faculty is free, and many times conceives strange, stupend, absurd shapes.’ In melancholic people, he added, this inner sense ‘is most powerful and strong, producing many monstrous and prodigious things’.4

The three ventricles of the brain and the location of the inner senses, from the Margarita philosophica (1503), an illustrated encyclopaedia widely used as a university textbook in sixteenth-century Germany. It shows how the outer senses of hearing, vision, taste and smell all meet in the common sense – the sensus comunis – in the front ventricle.

The doctrine of the inner senses did not last beyond the Enlightenment. It was first undermined by scientific discoveries in the sixteenth century which showed there was no direct connection whatsoever between the ventricles and any of the sensory nerves. It became even more unfashionable a century later, when Descartes’ distinction between mind and body suggested that thinking could take place purely in the mind, without any sensory inputs. This was a conclusion he reached by means of his famous method of doubt, arguing that an evil demon could be mischievously creating all his sensory experiences – rendering them illusions – but that the one and only thing he knew for certain was that he, René Descartes, was thinking. The result, cogito ergo sum, drove a sharp wedge between mental states and our sensory worlds.5

We should not, however, be too dismissive of the idea of the inner senses. Current neurological research shows that particular parts of the brain, or neural relationships within it, are responsible for capacities such as memory and imagination, so medieval physicians were perhaps not so mistaken after all. And most of us have experienced those uncanny moments, celebrated by Proust, when an unexpected smell or taste suddenly evokes a long-lost memory, perhaps of a childhood holiday or our grandmother’s kitchen. This kind of intimate connection between our outer and inner worlds would hardly have surprised Avicenna. Most importantly, recognising that for centuries people were convinced we had around ten senses is a reminder that our own conception of the five senses might be too constricted, and that there may be more sensory possibilities than we had previously imagined. It’s just common sense.

In fact, the current scientific consensus is that we possess up to ten senses, which work closely together to create our perceptual experiences – a ‘sense’ being defined as a physical mechanism by which information from the outside world enters our central nervous system. In addition to the traditional Aristotelian five, some five further senses have been identified over the past century. Thermoception is a sense physiologically distinct from touch which enables us to detect temperature differences – just as Plato suggested. Now close your eyes and slowly move the tip of one finger to touch your nose. If you happen to miss your nose, then your proprioception is askew. Sometimes also known as kinaesthesia, proprioception is the awareness of your body parts in relation to one another, and the sensation of their movement through space. Ask someone to pinch you, and you will have encountered nociception, your sense of pain. Practise juggling while standing on one leg and you will be cultivating equilibrioception, your sense of balance – the main organ for it, the vestibular labyrinthine system, can be found in our inner ears. Finally, human beings possibly have a weak sense of direction, magnetoreception. In the ethmoid bone just between our eyes and behind our nose is a tiny crystal of magnetite, which is like a compass that orients us within the earth’s magnetic field. Animals such as homing pigeons, bats, bees, migratory salmon and dolphins also possess this magnetic mineral. Nobody really knows how it works, but if you are the kind of person who never seems to get lost as you are wandering around a new city, it could be that your sense of magnetoreception is in optimal working order.6

Aristotle may have had one of the biggest brains in ancient Greece, but his idea of the five senses was certainly not one of his best. Giving up this myth is a sensory liberation and the beginning of a new adventure in human experience. We might begin, for example, by cultivating our sense of balance. One of the reasons I do yoga – badly – is to improve my balance on the tennis court, as I have a tendency to lose my footing when hitting ground strokes. We could also work on developing our kinaesthetic sense, useful for anybody who spends long hours at a computer. It is common for many people to end up hunched over their keyboard because their shoulders gradually creep forward as they type. But if you become kinaesthetically aware of the position of your shoulders in relation to your upper body and hips, it is possible to notice the creep as it happens, so you can correct your posture. If you seek a more dramatic way to nurture your new senses, you could follow the example of Lawrence of Arabia, who apparently made a habit of testing the limits of his sense of pain by seeing how long he could hold on to a burning match before it turned to ash in his fingertips. But before taking this all too far, we need to explore the regrettable episode of how sight came to dominate the other senses in Western culture.

Over the past 500 years the way we perceive the world has undergone a radical transformation. While sight is generally considered our biologically dominant sense – the visual cortex is the largest sensory centre in the brain – it has taken on an exaggerated importance in our lives. We have extended the influence of vision further than nature ever intended, and our other senses, especially hearing and smell, have faded into the background, undergoing what cultural historians refer to as ‘sensory decline’.7 There was a time when there was greater equality between the senses, when people were more aware of what they heard and smelled. But now we are less likely to hear the birdsong as we hurry to work, and gulp down our coffee without paying attention to the wafting aromas – a scent crime the Ongee would never commit. The eye has become a sensory tyrant that distracts us from cultivating the rest of our faculties. According to David Howes, a prominent anthropologist of the senses, we must liberate ourselves from ‘the hegemony which sight has for so long exercised over our own culture’s social, intellectual, and aesthetic life’.8

While some people are born with a particular sensitivity to sound or smell, there is overwhelming evidence that we live in a primarily visual culture. Supermarkets sell us tomatoes which look red and juicy but are often tasteless. Advertising relies more on images – on television, billboards, websites – than on other sensory inputs. We exhibit our wealth and status visually, having an elegant home or driving a stylish car. We typically judge people as attractive by their looks: their facial features, the shape of their body, the clothes they wear. That is why we say ‘love at first sight’, rather than, say, ‘love at first sniff’ – even though we are often aware of someone’s perfume or body odour. Teenage girls aspire to be supermodels, admired for their appearance rather than their minds. The main way we learn and gain knowledge is not by listening or doing but by reading and looking – the visual world of books, whiteboards and computer screens. No holiday is complete without a set of photos that can be recalled instantly on our phone, originally an audio device that has now been enhanced with visual features. Talk to someone who is blind and you become conscious of how the English language is pervaded by visual idioms – a sight for sore eyes, look before you leap, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. ‘Seeing is believing,’ we say, not realising that the original expression from the seventeenth century was ‘seeing is believing, but feeling’s the truth’.9 Feelings are now out of fashion, and all that matters is what the eye can see. We have come to inhabit a world of surface appearances.

Could we really alter our approach to perception and become more attuned to neglected senses like hearing and smell, which have been eroded by our visual culture? Could we regain the sensory curiosity we once had as children – constantly tasting, sniffing, touching? This is where history can play a role. We need to return to a time before sight came to monopolise our senses in the eighteenth century, when our heightened awareness of sound and scent gave more depth and complexity to everyday life. If we wish to develop a more balanced approach to the senses, we must understand how the eye came to exert its rule over the ear and nose.

When we think of classical civilisations, we may conjure up images of philosophers in togas, bloody battles and exploited slaves. But what did the ancient world smell like? We would undoubtedly be struck by the pervasive use of perfumes. While today we dab on a little perfume or cologne for a night out, a wealthy Athenian man might have applied several different scents: marjoram to his hair, sweet mint to his arms and thyme to his neck. Accompany him to a fashionable dinner party, and you could be adorned with a wreath of roses, then wafted with scent from perfumed doves fluttering above your head. When King Antiochus Epiphanes of Syria held public games in the second century BC, everyone who entered the stadium was anointed with scents such as saffron, cinnamon and spikenard, and upon leaving they received crowns of frankincense and myrrh. The Romans scented not only their food and homes, but also their domestic animals, and Nero’s palace was strewn with rose petals. Incense and other fragrances were used extensively in religious rituals and were believed to unite humans with the gods. Scent was not just a matter of individual taste, but a feature of public life.

The appreciation of scent was extended in the Middle Ages by the Crusaders, who brought back exotic spices and perfumes from the East to Europe. The spice box became an essential feature of the medieval kitchen, and food was prepared not simply to stimulate the taste buds but to provide olfactory delights. Hampton Court Palace, home to Henry VIII, contained a spicery, a special room where spices were ground into powder. For centuries, the international spice trade connecting Asia, Africa and Europe was fuelled by the desire not just for commercial profits, but to satisfy our increasingly refined senses.10

The widespread use of spices, perfumes and pomanders – scented cases often worn around the neck – which prevailed in Europe until the eighteenth century, helped to create a highly scented culture with a sophisticated approach to smell which now eludes us. When Parisians went for walks, they were just as likely to notice the smells as what they saw along the way, due to what one historian calls ‘a collective hypersensitivity to odours of all sorts’.11 Metaphysical poets such as John Donne were as much infatuated with the scent of their lovers as with their visual beauty: ‘As the sweet sweat of roses in a still, / As that which from chafed musk cat’s pores doth trill, / As the almighty balm of th’ early east, / Such as the sweat drops of my mistress’ breast.’

Fragrance was not, however, simply a sensory indulgence. It was also a necessity, a tool to block out the foul odours and pestilential smells that constantly assaulted the nostrils. Consider this description of an eighteenth-century city from Patrick Süskind’s novel Perfume (1985):

… there reigned in the cities a stench barely conceivable to us modern men and women. The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of mouldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlours stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets … People stank of sweat and unwashed clothes; from their mouths came the stench of rotting teeth, from their bellies that of onions, and from their bodies, if they were no longer very young, came the stench of rancid cheese and sour milk and tumorous disease. The rivers stank, the marketplaces stank, the churches stank, it stank beneath the bridges and in the palaces.

Today, in our deodorised society, we can hardly imagine the fetid stench of the past. But equally we cannot easily imagine the obsession with perfumes and other fine scents. We have lost the acute alertness to smell that our ancestors once possessed. Since the rise of personal hygiene and public health in the nineteenth century, we no longer consider scent to be a matter of great importance – smell has been downgraded in our ranking of the senses. While we should be pleased we no longer have stinking chamber pots under our beds, the scent vacuum that has emerged in the West is a loss for the art of living. As the cultural anthropologist Edward Hall has pointed out, ‘The extensive use of deodorants and suppression of odour in public places results in a land of olfactory blandness and sameness that would be difficult to duplicate anywhere else in the world. This blandness makes for undifferentiated spaces and deprives us of richness and variety in our lives.’12 History calls on us to rediscover our former sensitivity to smell and to become more alive to the scent-scape that surrounds us.

The decline of smell cannot alone explain why sight in particular has become so dominant today, ruling over the other non-visual senses. We must now turn to four further historical developments that altered the balance of the senses towards the eye, the first of which was the gradual shift from aural to visual culture that took place from the fifteenth century.

A major finding of twentieth-century anthropology was the vibrancy of the spoken word in many preliterate societies. Storytelling was often at the centre of community life, and knowledge – whether concerning religion, hunting or childcare – was transmitted verbally. In West Africa, this oral tradition remains embodied in the griot, a kind of walking cultural encyclopaedia who relates local history and folklore in poetry and song, and who may also be an adept satirist as well as a musician. In medieval English and Celtic society, this role belonged to bards, professional poets whose songs and tales were depositories of family and martial history in an era pre-dating the extensive use of writing. Few outside the aristocracy and clergy knew how to read or write. In the Middle Ages people didn’t read the Bible, they heard the word of God spoken out loud. They didn’t keep address books or diaries, nor did they learn their trade from training manuals. Speech was the pre-eminent medium of human knowledge, and memory the art which supported it.13

Then came Johannes Gutenberg. His invention of the movable type printing press in the 1430s was the most momentous event in the history of the senses. According to the cultural critic Marshall McLuhan, it created a ‘twist for the kaleidoscope of the entire sensorium’, sparking a communications revolution in which ‘the eye speeded up and the voice quieted down’.14 The printing press made the process of acquiring knowledge not only more readily available, but also more private and visual. Information and ideas were increasingly conveyed on the page, and oral traditions slowly began to unravel. The bard went out of business and the book took his place. As the publishing industry and public education expanded in later centuries, and we became buried under a proliferation of books, newspapers and magazines, the typographic culture instigated by Gutenberg gradually took over our lives. Our pre-modern forebears would be shocked at how many hours most of us spend each day reading or writing, and staring at letters, numbers and images on electronic displays. If there is a single factor explaining our increasing bias towards vision, the printing press is it.

A second force distorting the senses in favour of the eye was the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There had always been distrust of the senses within Christian thought. In the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas argued that ‘man is kept away from a close approach to God’ by pleasures of the flesh and the senses.15 The ideals of chastity and virginity unequivocally denied the sense of touch. The rise of flagellation in the thirteenth century, in which physical pain was self-inflicted on the body in imitation of the suffering of Christ, was a punishment of the senses – even if the devout occasionally whipped themselves into a state approaching sexual ecstasy. But radical Protestant reformers took a more systematic approach to the repression of the senses. They banned the burning of incense in their churches, which was part of a broader assault on scent. In The Anatomy of Abuses, published in 1583, the English Puritan Phillip Stubbes warned women that the time would come when ‘instead of pomanders, musks, civets, balmes, sweet odours and perfumes, they shall have stench and horrour in the nethermost hel’. Stimulating the taste buds was also subject to disapproval: food should be simple, and lavish feasting treated with suspicion. The eye was usually spared criticism in this puritanical drive towards sensory austerity, since it allowed people to view the grandeur of God’s creation.16

Vision was given a substantive boost in the eighteenth century. During the Enlightenment, argues the historian of the senses Constance Classen, ‘sight became allied with the growing field of science’.17 The microscope was the visual tool at the centre of emerging fields like biology, the telescope made possible the discoveries of astronomy, and chemical experiments recorded what was observed when gases mixed together. The empirical truths of the universe were seen, rather than heard or detected with other senses. Scientific knowledge was deposited in visual aids such as maps, charts and diagrams. Seeing was transformed into believing, vision into understanding. The Enlightenment was a visual age, in which a shining light helped us to better see the structures of reality. Scientific method naturally lent itself to the use of the eye, and the increasing importance of science in public culture served to deepen the inequality between the senses.

A fourth force, which also emerged in the eighteenth century, was the visual display of wealth and property amongst the European bourgeoisie. Bourgeois culture privileged the eye. The purpose of wearing a fine coat, riding in an elaborate carriage or living in a grand home was not simply to enjoy them for their own sakes, but to enable others to visually admire them. This nexus between the eye, wealth and social status was evident in the development of landscape painting. Consider Gainsborough’s well-known work Mr and Mrs Andrews (1750), which hangs in London’s National Gallery. Its most interesting feature is not the superb brushwork of the cloud formations, but the fact that the lucky couple clearly wish for all the world to see their vast rural estate stretching into the distance behind them. ‘Among the pleasures their portrait gave to Mr and Mrs Andrews,’ writes the art critic John Berger, ‘was the pleasure of seeing themselves depicted as landowners and this pleasure was enhanced by the ability of oil paint to render their land in all its substantiality.’18 Can you smell the money? No, but you certainly can see it.

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr and Mrs Andrews (1750). The couple’s property in rural Suffolk extends as far as the eye can see, a vision not just of naturalistic beauty but of material prosperity.

The legacies of the past are not always easy to detect in daily life. Have we really become as addicted to vision as the history of the senses seems to suggest? Anybody who avidly listens to podcasts on their morning commute or who cannot resist the smell of bacon or is taking a course in aromatherapy would probably say their ears and noses are in perfectly good shape, and that they have not succumbed to the tyranny of the eye. Yet have a look at the typical suburban garden.

Gardening is one of the most popular pastimes in many Western countries: Britain has more than 20 million devotees. While some people treat their gardens as mini wildlife sanctuaries or vegetable plots, the majority approach gardening as an exercise in visual aesthetics. What matters more than anything else is how the garden appears to the eye. Does the mixed border have a pleasing combination of colours, heights and shapes? Are there enough plants with ‘winter interest’, which remain attractive throughout the year? Is the lawn a neat and pristine carpet? Is there space for cheerful window boxes full of bright and vibrant annuals, or for an area of colourful bedding plants? How about a double-flowered camellia in the front bed, and a striking deep purple clematis, ‘Polish Spirit’, climbing up behind? When I worked as a gardener, it became obvious to me that the primary objective of contemporary garden design is to create a visually pleasing picture.

Most gardeners do not realise, however, that before 1700 visual beauty in gardening was not nearly as important as it is today. Take, for instance, the history of rose cultivation. Until modern times, roses were mainly grown for their scent, not their appearance. In his Natural History, written in the first century, Pliny the Elder provides a detailed discussion of which climates produce roses with the finest perfumes, and how to pick a rose to preserve its scent. Roses were featured in medieval and Renaissance gardens especially for their fragrance, explaining why Shakespeare declared, ‘a rose by any other name would smell as sweet’ – rather than ‘would look as lovely’. In one of the most popular gardening books of the seventeenth century, top prize goes to the damask rose for possessing the ‘most excellent sweet pleasant scent’. But parallel to the general demise of odour in the West, fragrance faded as a desired attribute of the rose from around the eighteenth century. New cultivars were increasingly bred for their size and colour, with little attention given to scent. In the 1890s a historian of gardening was moved to write, ‘a rosery of today would astonish the possessors of gardens in the Middle Ages, and the varied forms and colours would bewilder them, yet in some of our finest-looking roses they would miss, what to them was the essential characteristic of a rose, its sweet scent!’19 The deodorised roses that fill so many gardens today are a symbol of the stranglehold that the eye has on the rest of our senses.

A similar story can be told about the evolution of garden design. The earliest gardens were created not just for pleasure and beauty, but to convey symbolic meanings – to stimulate the mind through allegory and metaphor. Enter an ancient Persian ‘paradise garden’ and you would have to cross water channels, which represented the four rivers of heaven. Once inside you would find a profusion of fruit trees, symbolic of the fruits of the earth created by God. Chinese gardens were also full of allegorical meanings. One hundred years before the birth of Christ, the Han Emperor Wei designed a parkland containing artificial lakes and islands to represent an old myth about the dwelling places of immortal beings. In medieval Europe plants were frequently grown for their symbolism, which was often based on biblical tradition or ancient folklore. A lily alluded to the purity of the Virgin Mary, a violet to humility and patience. Rosemary was a symbol of remembrance, while myrtle and roses represented love. This tradition was later revived, but only briefly, by the Victorian language of flowers.20

Just as roses lost their fragrance, so the symbolism was bred out of garden design in favour of visual enjoyment. It began with the rise of formal geometric planting and topiary in the French Renaissance, which reflected a classical enthusiasm for visual order and symmetry. The craze for landscape gardening led by Capability Brown in the eighteenth century gave precedence to creating fine pastoral vistas. The most significant shift, however, was the growing popularity of the English cottage garden in the nineteenth century, which transformed the private garden into a visual canvas to be covered with harmonious colours. The high priestess of this movement was Gertrude Jekyll, who remains one of the most influential garden designers of the last 200 years. ‘The purpose of a garden is to give happiness and repose of mind,’ she wrote, ‘through the representation of the best kind of pictorial beauty of flower and foliage.’ The colours at a gardener’s disposal should be treated like an ‘artist’s palette’, and design was in essence an exercise in colour composition. Jekyll, who had always wanted to be a painter, treated the garden like an impressionist watercolour, where the principal concern was to convey delicate visual images.21

It is true that some contemporary gardeners are becoming more interested in the sensory stimuli of scent and texture, and there are occasional experiments in symbolic design, such as Charles Jencks’ ‘Garden of Cosmic Speculation’ in Scotland, based on the structure of DNA. But gardening today remains largely frozen in the pictorial mode of the nineteenth century. An excessive focus on satisfying the eye has drained away the sensory complexity, multi-layered meanings and self-expression that permeated the gardens of the past, and replaced them with the ‘colourful show’ celebrated in gardening magazines. ‘In our century,’ concludes a historian of plant symbolism, ‘flowers have been trivialized.’22

We now occupy a hyper-visual society. Sight has increasingly become the default filter for our sensory experiences, and our perceptions of sound and scent may be more dulled than at any other moment in Western history. Neither has taste been able to compete with sight, even though we have become more adventurous eaters over the past half-century, experimenting with such things as tabbouleh and Sichuan prawns. The result is not only that most of us fail to develop the sensory sophistication at our biological disposal, but that we are becoming accustomed to the superficial realities of surface impressions. We will enjoy a film for its 3-D special effects even if the story and acting are lousy, or admire a politician who comes across well on television even if their policies lack substance.23

Yet there is a way out of our sensory deprivation, a means of replenishing the full spectrum of sensation. We need to step into the shoes of people who have developed such extreme levels of sensory awareness that they have had a more nuanced experience of everyday life. Let’s turn to two individuals who can provide us with the inspiration to cultivate our neglected senses, and to expand human consciousness itself.

On the afternoon of Monday, 26 May 1828, a shoemaker in the German town of Nuremberg noticed a bewildered youth dressed in peasant clothes wandering helplessly around the streets. He could mutter only a few incoherent words, and was found to be carrying a letter stating that he had been born in 1812 and was the son of a deceased cavalry officer. He was able to write nothing more than his name: Kaspar Hauser.

After spending several weeks detained as a vagrant in the local gaol, he was taken in by Dr Georg Friedrich Daumer, a professor and philosopher, who slowly taught him to speak. Kaspar eventually revealed his incredible story: for as long as he could remember, he had been locked up in a dark cell two metres long and one metre wide. He was given bread and water daily by a man he never saw, slept on a bed of straw, and his sole possession was a carved wooden horse. Who was this strange foundling, only four foot nine and with an unusual talent for drawing, who seemed to have come from nowhere? Could he possibly be the heir to the royal throne of Baden, who had been kidnapped and imprisoned by unscrupulous rivals to prevent his accession? The mysteries surrounding the teenager deepened in 1829, when he was attacked by an unknown assailant. In 1833 he was assaulted once more – he claimed by a stranger – receiving a stab wound in the left breast. Within a few days he was dead. Some thought he was the victim of political intrigue. Others that he had accidentally taken his own life. The riddle of Kaspar Hauser has never been solved.

For all the uncertainties, what we do know is that he had extraordinary sensory abilities. These were meticulously recorded by a respected jurist, Anselm von Feuerbach, who had taken a personal interest in his case. Feuerbach noticed ‘the almost preternatural acuteness and intensity of his sensual perceptions’, which may have developed through being imprisoned in darkness for so many years and having to make the most out of the few stimuli available to him. Careful experiments and observation revealed that Kaspar had remarkable eyesight and could virtually see in the dark. At twilight, when most people could pick out only a few stars, he could already see hundreds in their various constellations; at sixty paces he could distinguish individual berries in a cluster of elderberries, and tell them apart from adjacent blackcurrants. His hearing was equally highly attuned, and he was easily able to recognise people from the sounds of their footsteps. His sensitivity to smell became famous. He could tell apart apple, pear and plum trees at a great distance simply by the smell of their leaves. But scent was also a cause of considerable distress. ‘The most delicate and delightful odours of flowers, for instance the rose, were perceived by him as insupportable stenches, which painfully affected his nerves,’ recorded Feuerbach. He could even smell dead bodies under the ground, which would make him break out in a violent sweat. Having lived in the constant temperature of the dungeon, he was hypersensitive to heat and cold: the first time he touched snow, he screamed out in pain.

Most extraordinary of all was Kaspar’s perception of magnetic fields. When the north pole of a magnet was pointed at him, he felt drawn towards it, as if a current of air was coming from him. The south pole, he said, blew upon him. When two incredulous professors conducted several experiments designed to deceive him, they found that Kaspar indeed possessed a definite and powerful magnetic sense – one of the ‘extra’ senses that, as noted earlier, has been identified by contemporary scientists.24

What can we learn from the sensory biography of Kaspar Hauser? Certainly that environment can alter our sensory skills, sharpening them to unexpectedly high levels. His sensitivity to smell was similar to that which has been found in many feral children, suggesting, according to Constance Classen, ‘that this sense may be by nature of great importance to humans and that it loses its importance only when suppressed by culture’.25 So if we made a regular effort, we too might be able to smell the leaves of a fruit tree, or learn to distinguish the subtly different scents among varieties of apple. It is also noticeable how quickly Kaspar’s superhuman sensitivity faded. Within a few months of escaping the dungeon he was so accustomed to being in natural and artificial light that his night vision began to disappear, and while he could still walk in the dark he could no longer read or discern tiny objects in darkness. His palate adjusted rapidly: initially averse to almost any food besides bread – his staple diet for years – he quickly came to eat most meats. He also complained that his keen hearing deteriorated after immersion in society. Culture and context, it seems, are playing a constant game with the senses, shifting the balance between them, encouraging them sometimes to bloom but at other times to fade. The opportunity before us is to take part in the game, searching for ways to help expand our sensory faculties.

Along with Kaspar Hauser, there is one other sensory icon we should never forget: Helen Keller. Born into a prosperous family in northern Alabama in 1880, Helen had a normal childhood until she was nineteen months old, when she suffered from a terrible illness – probably meningitis – which left her deaf and blind. Over the following years she developed into a headstrong and aggressive child. She would lock unsuspecting family members in their rooms and then hide the key, and throw violent tantrums when she didn’t get her own way or was frustrated at her inability to express herself. But when Helen was seven years old, her life changed entirely. Her father sought the advice of Dr Alexander Graham Bell – not only the inventor of the telephone but a renowned expert in deafness – who suggested employing a teacher from the Perkins Institution for the Blind in Boston. A few months later, Anne Mansfield Sullivan arrived to live with the family in Alabama.

Annie’s method of teaching Helen to communicate was to ‘speak’ into her hand, using a series of hand signs that represented the letters of the alphabet, a kind of fingered Morse code. At first Helen was unable to make any connection when the word d-o-l-l was spelled into one hand as she held her doll in the other. But there soon occurred one of the most life-changing moments in sensory history, when Annie thrust her pupil’s hand under a spout of water. As Helen recorded in her autobiography:

As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten – a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that ‘w-a-t-e-r’ meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. The living world awakened in my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!

Helen had learned that everything had a name, and that the manual alphabet was the key to knowledge. ‘As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life.’26 Within a few hours she had added thirty more words to her vocabulary. Soon she was reading Braille, and only three months after the water revelation, Helen wrote her first letter. Although shrouded in a dark, soundless world, Helen’s intellect flowered. In 1900 she entered Radcliffe College, and four years later was the first deaf-blind person ever to graduate from an institution of higher learning. Following university, Helen established herself as a writer and lecturer, a passionate advocate for the deaf and blind, and a socialist activist. Her fame spread and she met the great and the good of her age – from Mark Twain to President Kennedy – usually with Annie Sullivan by her side, translating into her hand. Her autobiography, The Story of My Life, sold millions and was made into the Oscar-winning The Miracle Worker, a film produced during her lifetime which she was never able to see.

Helen’s life is often remembered as an uplifting tale of personal triumph over extreme physical adversity. But it is just as much an inspiration for how to develop our sensory selves. Like Kaspar Hauser, Helen had extremely sharp sensory abilities. But unlike him, she revelled in the pleasures of her senses, and could express her perceptual experiences with a poetic beauty. Her writings take us into the most sublime and complex sensory world imaginable. Helen possessed what she called ‘a seeing hand’:

Ideas make the world we live in, and impressions furnish ideas. My world is built of touch-sensations, devoid of physical colour and sound; but without colour and sound it breathes and throbs with life … The coolness of a water-lily rounding into bloom is different from the coolness of an evening wind in summer, and different again from the coolness of the rain that soaks into the hearts of growing things and gives them life and body. The velvet of the rose is not that of a ripe peach or of a baby’s dimpled cheek. The hardness of the rock is to the hardness of wood what a man’s deep bass is to a woman’s voice when it is low. What I call beauty I find in certain combinations of all these qualities, and is largely derived from the flow of curved and straight lines which is over all things … Remember that you, dependent on your sight, do not realize how many things are tangible.27

Helen listened to classical music through its vibrations and could tell the age and sex of strangers through the resonance of their walk on the floorboards. One day, when wandering through a favourite wood, she felt an unexpected rush of air coming from one side, and knew that nearby trees she loved must have been recently felled. She could recognise all her friends instantly by their smell. She even claimed to comprehend colour through the power of analogy: ‘I understand how scarlet can differ from crimson because I know that the smell of an orange is not the smell of a grape-fruit.’ Yet she recognised the limits of her knowledge, for she could never sense a room or a sculpture in its entirety, and was always piecing together the small portions of the world her fingers could touch at any one moment.

What is Helen Keller’s message for the art of living? ‘I have walked with people whose eyes are full of light, but who see nothing in wood, sea, or sky, nothing in city streets, nothing in books. What a witless masquerade is this seeing! … When they look at things, they put their hands in their pockets. No doubt that is one reason why their knowledge is often so vague, inaccurate, and useless.’ Our task, it seems, is to take our hands out of our pockets, and cultivate all our senses. That is how we might both nourish our minds and, ultimately, deepen our experience of life.28

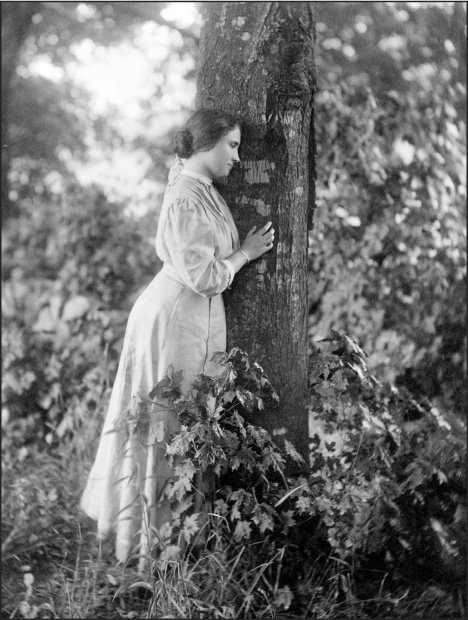

Helen Keller in sensory communion with nature, around 1907.

The senses can be a challenging dimension of everyday life. Some people feel they are victims of sensory assault – a constant bombardment of images and cacophonous noise compels them to seek calm and silence, to tune out of their senses. Others lead such busy lives that they have no time to appreciate the sensory universe. Yet if we had Helen Keller as a constant companion throughout each day, we would surely recognise that the senses are a gift, and be encouraged to make cultivating them a personal priority. How should we go about tuning in rather than tuning out?

I once asked an unsighted friend to design a sensory tourist trail of Oxford. The starting point, she said, would have to be the chapel of New College in Oxford University, where there is a sculpture of Lazarus by Jacob Epstein. I asked her why. ‘Touch him,’ she said, ‘he has the most beautiful knees in the world.’ From here, a trip to the Covered Market to lose oneself amongst the swirling medieval scents of smoked fish, butchers’ sawdust, wild mushrooms and cobblers’ shoe leather, followed by a blindfolded walk along the towpath of the Thames. Again I was intrigued. ‘It’s not just about feeling the cool breeze off the river or hearing the flapping wings of the Canada Geese,’ she explained. ‘There’s an edginess walking along the towpath, a sense that you could almost topple in at any moment if you lose your footing. It keeps you on your toes, in a state of complete awareness.’ The tour would end at the Ashmolean Museum. ‘I once had an art historian show me his favourite portrait painting there,’ she told me. ‘I asked him to describe it and he started telling me about brushwork and composition and all sorts of rubbish. And I said to him – but how has the artist made the face look human? He didn’t have an answer to that, because he had never really looked at his favourite painting.’ If my friend were the tour guide, visitors would be asked to describe paintings to her, so they learned to see them with fresh eyes.

We might each think of ourselves as sensory travellers, embarking on tours of our local landscape to discover its hidden depths and beauties. Could you create a sensory itinerary for exploring your neighbourhood, or even your own home? Or we might simply decide to focus our awareness on the smell and texture of the food we eat each evening, looking for exactly the right words to describe our culinary experiences. What does the skin of a ripe plum smell like, and what does it feel like in our mouths? We might equally endeavour to hone our non-traditional senses, for instance by doing yoga or the Alexander Technique to develop our kinaesthetic sense of bodily movement and balance. We should also appreciate our senses as a potential source of consolation. I once overcame a broken heart by taking a walking trip along the Welsh coast, each day concentrating on a difference sense – smell, sound, sight. It was not just a distraction from my personal pain, but a more positive immersion in the present, almost a meditative act.

The senses are one of the most precious ways we have to learn about the world, and about ourselves. Most of us have hardly begun to harness their latent power. Turning on our senses is a forgotten freedom we all possess, and can add new dimensions of meaning and experience to our lives. It is time we opened ourselves to all the delights, surprises, curiosities and memories that lie in wait for us.