CHARCUTERIE AND FRENCH PORK COOKERY was the first of Jane’s long series of books on food and cooking. Living in France, she became fascinated and delighted by the skill of local charcutiers. A scheme was hatched with a friend to write a book on the local subject, Jane as researcher, the friend Adey as writer. In the end the task of writing it fell to Jane as well, and Charcuterie and French Pork Cookery was published in 1967. It remains the best and only dedicated book written in English on this vast and intricate subject, and deserves a chapter all to itself.

Anyone visiting France soon becomes aware of the importance of charcuterie shops in French daily life. The choice of pork products is almost bewildering, many of them unfamiliar to foreigners, all of them tempting. For Jane, at the beginning of the French part of her and Geoffrey’s life, the whole subject was a treasure trove into which she plunged with characteristic energy and lively curiosity.

The pleasure with which her chosen publisher must have read Jane’s manuscript can only be imagined. The pleasure the published book has given, and will go on giving, may be judged from the extracts which make up this third chapter of The Best of Jane Grigson.

It could be said that European civilization – and Chinese civilization too – has been founded on the pig. Easily domesticated, omnivorous household and village scavenger, clearer of scrub and undergrowth, devourer of forest acorns, yet content with a sty – and delightful when cooked or cured, from his snout to his tail. There has been prejudice against him, but those peoples – certainly not including the French – who have disliked the pig and insist that he is unclean eating, are rationalizing their own descent and past history: they were once nomads, and the one thing you can’t do with a pig is to drive him in herds over vast distances.

The pig as we know him is of mixed descent. An art of charcuterie – the chair cuit, cooked meat, of the pig – could hardly have been developed very far, however much people relied on pig meat, fresh or cured, as the staff of life, with the medieval pig carved on misericords, or painted in the Labours of the Months (pig-killing in November, or pig-fattening with the acorn harvest). He was a lean, ridgy and rangy beast, with bristles down his back. Two thousand years ago the Gauls in France were excellent at curing pork, and Gallic hams were sent to Rome. But what made the pig of the European sty – rather than the pig of the autumn oak forests – really succulent, was a crossing of the European and Chinese pigs in England round about 1760, by the great Leicestershire stock-breeder, Robert Bakewell.

The Chinese porker was small, plump and short-legged. The European pig was skinny and long-legged like a wild boar. The cross between the two resulted in the huge pink beast of prints by James Ward of 160 years ago. Cobbett wrote that the cottager’s pig should be too fat to walk more than 100 yards. Spreading through Europe, this was the creature on which French cooks got to work when the Revolution turned them out of their princely, aristocratic kitchens along the Loire and in the Île de France.

The trade of charcutier goes back at least as far as the time of classical Rome, where a variety of sausages could be bought, as well as the famous hams from Gaul. In such a large town slaughterhouses, butchers’ and cooked meat shops were necessarily well organized to safeguard public health. This system was still being followed – after a fashion – in medieval Paris, although in the later Middle Ages a great increase in cooked meat purveyors put an intolerable strain on such control as there was. From this insalubrious chaos the charcutiers emerged and banded together, by edict of the king in 1476, for the sale of cooked pork only, and raw pork fat. But they did not have the right to slaughter the pigs they needed, which put them at the mercy of the general butchers until the next century. At the beginning of the seventeenth century charcutiers gained the right to sell all cuts of uncooked pork, not just the fat. Now the trade could develop in a logical manner. Incidentally in Lent, when meat sales declined, the charcutier was allowed to sell salted herrings and fish from the sea.

In the larger cities of the eighteenth century the charcutier developed a closer connexion with two other cooked meat sellers – the tripier who bought the insides of all animals from both butcher and charcutier and sold cooked tripe, and the traiteur who bought raw meat of all kinds and sold it cooked in sauces as ragoûts, either to be eaten at home or on his ever-increasing premises. Remember that for many people at all income levels the private kitchen was a poor affair, often nonexistent; everyone sent out to the cooked food shops for ready-made dishes. It was a big trade, jealously guarded, so that the traiteurs considered that their functions as ragoût-makers had been usurped when a soup-maker, Boulanger, who described his dishes as ‘restaurant’ or restorative, began to sell sheep’s feet in sauce, to be consumed on his premises. He was taken to court in 1765 by the traiteurs, but he won, thereby gaining enormous publicity and a fashionable trade. More important still, he had broken through the closed shop organization by which the cooked food purveyors worked.

By the end of the century the guillotine had put many great cooks out of work. They soon saw the opportunities offered by the growing restaurant trade and the old cooked food trades vis-à-vis the more widely distributed prosperity of a new social order. The traiteur began to specialize in grand set pieces which he supplied on a catering basis to nineteenth-century bourgeois homes. The charcutier increased the range and quality of his pork products, and began to sell cooked tripe to his middle-class clients as well. Only the tripier seems to have lost in prestige, supplying poor families and shabby hotels with what Henry James described as ‘a horrible mixture known as gras-double, a light grey, glutinous nauseating mess’.

In the twentieth century all these categories have become blurred at the edges and interdependent. They have also benefited from most stringent food laws. French small-town hoteliers and restaurateurs now delight their clients with delicious preliminaries to the main course, supplied usually from the charcuterie near-by rather than their own kitchens. This is where English hotels outside London are at such a disadvantage. There are no high-class cooked meat and bakery trades in this country. The chef with a small staff cannot send out for saucisses en brioche, quiches lorraines, or a good pâté, leaving him free, as in France, to concentrate on his meat, fish and sauces.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, France, like every other European country, benefited from the development of refrigeration. Nobody needed the huge pig anymore. With cold storage, mild round-the-year ham and bacon curing became possible, which meant that less fat was needed to mitigate harsh-tasting lean meat. At the same time there was a big increase in machine and sedentary occupations, which lessened people’s need for a high fat diet. So the pig grew smaller. Now his weight is watched as carefully as any film star’s.

Probably the English pig is now being taken too far towards leanness, at any rate for the finer points of charcuterie. He has become too much a factory animal: we neglect his ears, his tail, his trotters, his insides, his beautiful fat and his flavour (pig’s ears by the hundred thousand are fed to mink, from one of the Wiltshire bacon factories, which is a bit like feeding caviare to canaries). But with a little care and persistence the housewife can bully out of her butcher what is known as ‘over-weight pig’, and for very little money she can obtain the fat parts, as well as the extremities and the offal – the basis of many of the most delicate and delightful dishes it is possible to make. The skilful and economical housewife can buy a pig’s head for very little; this is what she can make from it – pig’s ears with a piquant sauce, brains in puff pastry, Bath chap, 750 g (1½ lb) of sausage-meat for making pâté, or crépinettes, and some excellent rillons which are more usually made from belly of pork. There is on average 2¼ kg (4½ lb) of boneless meat on a pig’s head. And an excellent clear soup or aspic jelly is to be made from the bones.

So I hope that Charcuterie and French Pork Cookery, in some degree, will contribute to reinstating the pig in its variety in English kitchens, as well as help the holiday maker travelling in the country where the pig is most valued.

WHAT IS A TERRINE, WHAT IS A PÂTÉ?

A meat loaf is a terrine, a pork pie is a pâté. But only from an academic point of view. Nowadays the words pâté and terrine are used interchangeably by French and English alike.

Terrine, with the same origin as our English tureen, means something made of earth, of terra; we use the word to describe a deep, straight-sided oval or oblong dish, and stretch it to include the contents.

Pâté shares a common Romance origin with English words such as patty, pastry, and paste, and with Italian and Spanish words like pasta. Even though derived from the Greek verb, Πασσω, to sprinkle, it early acquired cereal connotations. Sometimes pâtés are hot, sometimes cold. Pastry is kept mainly for hot pâtés (what we call pies), and for the finest cold pork-based pâtés, or game terrines. Flat strips of pork fat are used to preserve moisture and flavour in more humble mixtures.

Many modem English cookery books give excellent recipes for making pâtés. Pâté maison is on the menu in many English restaurants. It is the first thing travellers in France think of buying for a lunchtime picnic. In the midday shade of a walnut tree, or poplars bordering a canal, two or three pâtés are laid out on the cloth, with new crusted bread, good butter, fruit, cheese and wine – not always very good wine perhaps, but very good pâté, and each day’s choice differing in flavour from the one before.

I am not thinking of exotics – the Pithivier lark pâté, for instance, the truffled foie gras pâtés of Perigord, or the superb range of Battendier’s game pâtés in Paris – but of the simple pâtés produced in unique variety in every village in France, above the size of a hamlet.

Our small market town, Montoire, with its 2,708 inhabitants, has four charcuteries. There are three pâtés on sale daily (the number increases dramatically at the great Feasts and on Sundays) in each shop, pâté de foie, páté de campagne and pâté de lapin. But none of them are quite the same, although the four charcutiers are using roughly similar recipes. So there is an immediate choice of twelve. Our own village of 549 inhabitants produces two pâtés – not counting rillettes, and fromage de tête and hure which further extend the picnicker’s choice.

When you go into a strange charcuterie, be brave. Take your time and buy small amounts of all the pâtés. There will not be sulks and sighs à l’anglaise – nor murmurings from the other customers behind. An enterprising greed is the quickest way to any French person’s generosity and kindness. Often persistence is rewarded by kindly hand-outs of saucisson and black olives to small daughters and sons.

All pâtés have a basis in the pig (though with the mouse-like ones it is a tenuous connexion, rather than a solid basis). Hare and game pâtés, for instance, often consist of small pieces or strips of the said creature layered with a pork forcemeat. As they cook slowly, pâtés have a permanent basting from the bards of pork fat which line the dish.

Variety, as I have said, is infinite. By the addition of different alcohols, different combinations of spices and herbs, orange juice and rind, an egg, a little flour, some truffle parings, one recipe can be stretched interestingly over months. You can chop the meat larger or smaller, or mince it. You can layer large pieces with a virtual mousse. You can pour off the fat after cooking and substitute a jelly made from game bones, or flavoured with Madeira, or port, or lemon juice. You can alter the flavour by keeping the pâté for a couple of days (indeed you should do this), or for weeks (run a good layer of lard or butter over the top) not in the deep freeze but just in the cool.

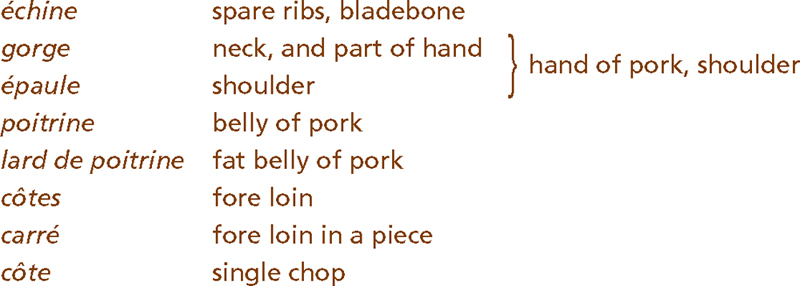

750 g (1½ lb) lean, boned shoulder of pork (épaule)

90 g (3 oz) veal, ham, or lean beef

250 g (½ lb) flair (leaf, flead, body) fat (panne)

250 g (½ lb) back fat (gras dur), cut into strips, or streaky bacon

250 g (½ lb) belly of pork (lard de poitrine)

seasonings – salt, pepper, quatre-épices, nutmeg, mace, crushed juniper berries, thyme, parsley, garlic, etc.

150 ml (¼ pt) dry white wine

60-90 ml (2-3 fl oz) brandy, Calvados, marc or eau-de-vie

250 g (½ lb) onions, chopped

90 g (3 oz) butter or lard

1 level tablespoon flour

1 large egg, beaten

If the butcher won’t cut the back fat into thin slices, and you can’t do it without slicing yourself, cut it as thin as you can safely manage, then beat it out with a wooden mallet. Salt and pepper lightly, leave in the cool. Caul fat, softened in tepid water, is a good substitute.

Chop all the other meat finely. Put it through the mincer if you must, but the Moulinette 68 is better. Mix in the seasonings you have chosen, and the alcohol, and leave to marinade overnight.

Next day cook the onions gently in the butter or lard until they are a golden hash. Do not brown them.

Beat the flour and egg together to a smooth paste, and add with the onions to the meat mixture.

Grease a terrine with lard. Any ovenproof dish will in fact do – there is no need to buy one of those dramatic dishes with dead hare lids, and simulated pastry sides. Provided it holds 1 litre (2 pt), it doesn’t matter what shape it is. If you like, you can divide the mixture between several smaller dishes.

Some people line the terrine next with shortcrust pastry, and cover the meat with a decorated pastry lid. But unless you want that kind of a showpiece (which adds considerably to your labour), a lining of pork fat strips is quite enough.

The seasoning of pâtés is a personal affair, but allow for the fact that foods to be eaten cold need more seasoning than foods to be eaten hot. It’s prudent to try out a small rissole (fried or baked), before irrevocably committing the pâté to the oven. Should you have overdone the seasoning, add more chopped meat, or – in desperate situations – some breadcrumbs.

Fill the terrine absolutely full, and mound over the top – it will shrink in the cooking. Lay a lattice of fat pork strips on top and cover with foil.

Stand the terrine in a larger pan of hot water, which should come about half-way up the side, and bake in a slow oven for 1½-3 hours, according to the depth of the dish: small but deep dishes of pâté take longer than wide, shallow ones. Oven temperature should be about gas 3–4, 170°C (340°F).

The pâté is done when it appears to swim in fat, quite free of the sides of the terrine; you can also test it with a metal knitting or larding needle – if it comes out clean the pâté is cooked.

You can also cook pâtés like steamed puddings, on top of the stove. If you want an addition to the store cupboard, try bottling the pâté in preserving jars like fruit. It needs 2 hours’ cooking. This is widely done in France.

Pâté can be served straight from the cooking dish. If you do this, remove the foil 20 minutes before the end of cooking time so that the top can brown appetizingly. Cool for 1 hour, then weight it gently.

Remember that it will taste better the next day.

For very elegant meals, the pâté is finished with meat jelly. If there is much fat, pour it off, add the jelly in a liquid state, and don’t weight the pâté until the jelly is beginning to set. Be careful to eat the pâté within three days if you have a refrigerator, within two days at most if you haven’t for jelly sours quickly. Flavour finally with Madeira or port.

If the pâté is to be the main dish of a meal, serve a green salad with it, and some small pickled gherkins. In France crusty bread is always served too, but English factory bread is flabby and needs toasting, or, better still, baking in thin slices to a golden brown crispness.

Although bottling is the best way of keeping pâté, it also keeps well under a 1-cm (½-inch) layer of lard, in a cool dry larder. A month is a safe length of time. To do this, allow the pâté to cool for an hour, then weight it not too heavily (a dish with a couple of tins on top, or a foil-covered board). Next day melt plenty of good quality lard and pour it over the pâté, so that it is completely covered to the depth of 1 cm (½ inch). When the lard has set cover it with silver foil, smoothing it on right close to the fat. Then put another piece of foil over the top, as if you were finally covering a jam pot. Store in the fridge if possible.

750 g (1½ lb) pig’s liver, weighed when hard bits are removed

750 g (1½ lb) belly of pork, salted in mild brine for 12 hours or

500 g (1 lb) fresh belly, 250 g (½ lb) green streaky bacon

250 g (½ lb) flair fat

strips of hard back fat to line terrine and cover or a large piece of caul fat

1 large egg

2 tablespoons flour blended with 150 ml (¼ pt) dry white wine seasonings to taste

Follow the recipe on the previous page.

500 g (1 lb) pig’s liver

250 g (½ lb) lean veal (fillet) weighed without bone (rouelle de veau)

250 g (½ lb) cooked ham fat, or very fatty ham

175 g (6 oz) fresh white breadcrumbs soaked in a little milk

2 large eggs

75 ml (½ gill) brandy, or other hard liquor

2 heaped tablespoons of parsley

salt and spices according to taste, including a bay leaf

4 heaped tablespoons onion melted in some lard (do not brown it)

plenty of fat bardes to line the terrine and cover

Mince the meat finely – mix everything together, except bards and bay leaf.

500 g (1 lb) lean shoulder of pork

500 g (1 lb) lean fillet of veal

250 g (½ lb) chicken livers

750 g (1½ lb) hard back fat

45 g (1 ½ oz) spices

30 ml (1 small liqueur glass) cognac or other brandy

60 ml (2 small liqueur glasses) port

5 egg yolks

250 ml (8 fl oz) cream

250 g (½ lb) tongue

250 g (½ lb) ham

125 g (¼ lb) fillet veal

125 g (¼ lb) hard back fat

750 g (1½ lb) puff pastry

All cut in strips and marinaded for 2 hours in some brandy.

Line the terrine with pastry, keeping back enough for the lid. Layer forcemeat, filling, forcemeat, filling, and finally forcemeat. Put on the pastry lid and decorate. Do not stand in a pan of water, but bake in a slow oven for 2–2½ hours, protecting the top when necessary with greaseproof paper.

When the pâté is quite cold, pour in meat jelly flavoured with port. Do this through a funnel by way of vents in the pastry lid. Or remove the lid carefully with a sharp, pointed knife, so that it can be replaced tidily when the jelly has been poured over the filling.

500 g (1 lb) sweetbreads (calves’ or lambs’)

chicken stock and a little lemon juice

375 g (¾ lb) lean pork, weighed without bone, or veal and pork

375 g (¾ lb) hard back pork fat

2 large eggs

1 tablespoon of flour, heaped

125 ml (4 fl oz) double cream

seasoning, salt, pepper and thyme

125 g (¼ lb) mushrooms

60 g (2 oz) butter

enough pastry to line and cover, made of:

250 g (8 oz) flour

150 g (5 oz) butter and lard, or butter

1 level tablespoon icing sugar, pinch salt, cold water

Here is a hot pâté of delicate flavour, whose ingredients are within the range of nearly every supermarket-goer. The result, though, does not betray its origins.

Stand the sweetbreads in cold, salted water for 1 hour. Then simmer them for 20 minutes in chicken stock, sharpened with a little lemon juice. Drain and take off the gristly hard bits and divide them into smallish pieces.

The forcemeat can be made whilst the sweetbreads are cooking. Mince the pork and fat as finely as you can. Add beaten eggs, flour, and cream. If you have an electric blender whirl the mixture in this. Season with salt and pepper, and thyme.

Slice the mushrooms (more than 125 g (¼ lb) does not hurt, and if you can use field mushrooms, or even better Trompettes des Morts [Craterellus Cornucopioides] the flavour will be greatly improved). Fry them lightly in butter. If you have plenty, mix half into the forcemeat after it has been whirled in the blender.

Now assemble the pie. Line a pie dish with pastry, then line the pastry with a thick layer of forcemeat, keeping aside enough to cover. Next put in the sweetbreads and mushrooms, and cover with the last of the forcemeat. Put on a pastry lid, decorate, knock up the edges and brush with egg yolk-and-water glaze. Bake in a moderate oven for 1 hour, protecting the pastry lid with greaseproof paper if necessary.

Elizabeth David’s version, quoted from A Book of Mediterranean Food, is the most popular with our visitors. I do it in the blender, however, putting the liquid from the pan in first then tipping the lightly cooked livers on to the fast whirling blades. Half quantities and a little more butter do very well – however the quantity can be divided amongst several small pots, covered with 1 cm (½ inch) of melted butter, and a foil lid, for eating on different occasions.

‘Take about 500 g (1 lb) of chicken livers or mixed chicken, duck, pigeon or any game liver. Clean well and sauté in butter for 3 or 4 minutes. Remove the livers and to the butter in the pan add 30 ml (a small glass) of sherry and 30 ml (a small glass) of brandy. Mash the livers to a fine paste (they should be pink inside) with plenty of salt, black pepper, a clove of garlic, 60 g (2 oz) of butter, a pinch of mixed spice and a pinch of powdered herbs – thyme, basil and marjoram. Add the liquid from the pan, put the mixture into a small earthenware terrine and place on the ice.

‘Serve with hot toast.’

Here is an old recipe for a hare pâté. Try it if you are having a large party, but it is prudent to bake the mixture in several terrines rather than in the one large stewpan recommended, then you can run a layer of lard over any you do not use at the time, and keep them for several weeks.

‘Chop all the meat of a hare, and of a rabbit, half a leg of mutton, [1 kg] two pounds of fillet of veal or fresh pork, and [1 kg] two pounds of beef suet; season these with pepper and salt, fine spices pounded, chopped parsley, shallots, [125 g] a quarter of a pound of pistachio nuts peeled, about [500 g] a pound of raw ham [use uncooked gammon] cut into dice, [250 g] half a pound of truffles or mushrooms also cut into dice, six yolks of eggs, and [60 ml] one glass of good brandy; garnish a stew-pan all round with slices of lard, put all your preparation close into it, and cover it over with slices of lard [i.e. hard back fat, not the modern lard but the French lard] also, rather thick; stop the pan all round with a coarse paste, and bake it about four hours; let it cool in the same pan, then turn it over gently; scrape the lard quite off, or leave a little of it, and garnish it with any sorts of colours; or to make it more even, and to give it a better form, cover it over with hog’s lard or butter, in order to garnish it with different colours according as your taste shall direct.’

1 rabbit

plenty of strips of hard back fat

plenty of chopped onions – about 250–375 g (½–¾ lb)

2 medium carrots, chopped

plenty of thyme

garlic, spices, salt and pepper, according to taste

I find that this is the most successful hot rabbit recipe, as well as one of the simplest. It is, in effect, a hot pâté or pie – which I have put here as it does not require pastry, as most hot pâtés do.

Joint the rabbit, then cut the joints into suitable serving pieces. Do not bone.

Line the terrine with strips of fat, as if you were going to make an ordinary pâté.

Put in a layer of rabbit, then a good layer of chopped vegetables, thyme, spices and so on, then a few strips of fat – no need to cover the layer completely. Then another layer of rabbit, the rest of the vegetables and spices, then a complete cover of strips of fat. Pour in enough dry white wine or rosé to come about half-way up the meat, and 2 liqueur glasses (60 ml or 2 fl oz) brandy or eau-de-vie de marc.

Fix the lid on with flour-and-water paste, or use a double-layer of foil as a lid, stand the terrine in a shallow pan of hot water and cook in a slow oven for 2 hours.

Serve with boiled potatoes, and a plain green salad to follow.

This recipe sounds disgustingly fatty – but it isn’t. The best flavour is obtained by using a wild rabbit (lapin de la garenne).

Here is one of Elizabeth David’s recipes for a pâté that is on a somewhat larger scale, suitable for a party or for a buffet supper. It will be sufficient for 20–25 people, and is all the better for being made 3 or 4 days in advance.

Quantities are 1 kg (2 lb) each of belly of pork and leg of veal (the pieces sold by some butchers as pie veal will do, as these are usually oddments of good quality trimmed from escalopes and so on), 250 g (½ lb) of back pork fat, and 1 wild duck or pheasant. For the seasoning you need 250 ml (2 teacups or 8 fl oz) of dry white wine,

1 tablespoon of salt, 8–10 juniper berries, 1 large clove of garlic, 10 peppercorns, 2 tablespoons of stock made from the duck carcase with a little extra white wine or Madeira.

Mince the pork and the veal together, or to save time get the butcher to do this for you. Partly roast the duck or pheasant, take all the flesh from the bones, chop fairly small, and mix with the pork and veal. Add 150 g (5 oz) of the fat cut into little pieces, the garlic, juniper berries, and peppercorns all chopped together, and the salt. Pour in the white wine, amalgamate thoroughly, and leave in a cold place while you cook the duck carcase and the trimmings in a little water and wine with seasonings to make the stock. Strain it, reduce to 2 good tablespoons, and add to the mixture (if it is necessary to expedite matters, this part of the preparation can be dispensed with altogether; it is to add a little extra gamey flavour to the pâté).

Turn into a 2-litre (3-pt) terrine; cover the top with a criss-cross pattern of the rest of the pork fat cut into little strips. Cover with foil. Stand in a baking tin containing water, and cook in a low oven, gas 3, 160°C (330°F), for 2 hours. During the last 15 minutes remove the paper, and the top of the pâté will cook to a beautiful golden brown.

One wild duck or pheasant to 2 kg (4 lb) of meat sounds a very small proportion for a game pâté, but will give sufficiently strong flavour for most tastes. Also the seasonings of garlic, pepper, and juniper berries are kept in very moderate proportions when the pâté is for people who may not be accustomed to these rather strong flavours, and with whose tastes one may not be familiar.

chicken, weighing about 2 kg (4 lb) when dressed

625 g (1¼ lb) lean meat (pork, pork and veal, or veal and ham)

500 g (1 lb) hard back pork fat

125 g (¼ lb) streaky bacon

2 eggs

herbs, spices, salt and pepper

pistachio nuts, blanched

125 g (¼ lb) cold pickled tongue

125 g (¼ lb) ham fat or pork fat

truffles

foie gras

liver from the chicken

brandy, Madeira, sherry or eau-de-vie

calf’s foot, or pig’s trotters

veal, ham or pork bones

1 onion stuck with 4 cloves

1 carrot

bouquet garni

375 ml (½ bottle) dry white wine

stock made from chicken bouillon cubes

The derivation of the word galantine is obscure. Snowdrops, rushes with aromatic roots, Chinese galangale (a mild spice of the ginger family), gelatine and the popular fish galantines of the Middle Ages, have all assisted, incongruously, in the speculations. But from a charcuterie point of view, the word takes on interest in the mid-eighteenth century, meaning then ‘a particular way of dressing a pig’. By the turn of the century galantine was used in France in its modern sense to describe a cold dish of chicken, turkey, etc., and veal, boned, stuffed, simmered in a cloth and pressed, making an elegant appearance swathed in and surrounded by its own jelly. Although talking of fish, Chaucer nicely described the emotions a galantine in its jelly might arouse:

Was never pyk walwed in galauntyne

As I in love am walwed and y-wounde.

Such enthusiasm is particularly delightful to the cook, because a galantine is not at all a difficult dish; its preparation is lengthy, but the result is never in question. Like pâtés, it should be prepared at least a day in advance for all the ingredients to settle down together and mature.

In the charcuterie, the galantines look like pale-coloured pâtés, with a geometric patterning of fat, truffles, pistachio nuts, tongue, foie gras, and jelly. From a commercial point of view it is necessary to prepare them in long metal loaf-tins, rather than with boned birds, so that every customer’s slice has its exact share of all the good things. I find these galantines disappointing, very often. Their almost classical intarsia prepares one for a supreme experience, and of course one is let down. Galantine of rabbit or pig’s head is inevitably prepared in this way, but for attractiveness and flavour, poultry, veal and game galantines should be tackled like this.

Choose a mature bird. Battery chicken is useless, as flavour is needed.

Cut the flesh from neck to tail down the back, and by using a very sharp knife to scrape the flesh off the bone, you will not find it difficult to achieve a flat, if locally lumpy, oblong of bird. Do not pierce the skin, though this can be remedied by removing a piece of flesh from, say, the leg and lying it over the small tear. The worst part is the legs. Take your time, and gradually pull the muscles and skin off inside out, as your knife loosens them from the bone. Lay the final result, skin side down, on a clean cloth and distribute extra bits of flesh over the thinly covered parts. But don’t get fussy and niggly with it. Sprinkle on some salt and pepper; leave in the cool.

Put the carcase on to boil in a large pan, together with a calf’s foot or pig’s trotters, a ham bone if you have one, 1 onion stuck with 4 cloves, 1 carrot, bouquet garni, and a mixture of wine and stock. Any other scraps of pork skin, or pork, veal or poultry bones, would not come amiss. You need as good a stock as you can make.

Assemble any attractive bits and pieces that you can manage – the liver of the bird, foie gras, truffles, pistachio nuts, cold tongue, cold ham, ham fat or pork fat – and decide whether you are going to make a formal arrangement, or whether you are going to dice these and mix them right in with a fine forcemeat. This collection of larger pieces is known as a salpicon. Leave them to marinade in some brandy or Madeira or sherry.

Make the forcemeat – as fine as you can – of equal parts of lean and fat meats: pork entirely, with a little bacon, if you like; or lean veal and lean ham and fat pork; or the lean flesh from an extra bird and veal or pork or both, and an equal quantity of fat pork. You need about 1 kg (2 lb) for a 2 kg (4 lb) chicken, correspondingly more for a turkey, less for a partridge or pheasant. Bind with 2 eggs; season with salt, pepper, herbs, spices, according to your preference and the creature concerned.

I don’t advise the use of shop-bought sausage-meat, ever. It’s too stodgy. If you can’t face the tough mincing required, ask the butcher to do it for you.

If you want to include the salpicon, either add it to the forcemeat, stirring it in well, so that you have an evenly marbled mass to lay on the boned chicken, or put two layers of it, attractively arranged, between three layers of forcemeat, on the boned chicken.

If you are omitting the salpicon, lay the forcemeat by itself on the chicken.

The next step is to wrap the back edges up and over the forcemeat, etc., and sew it into a rough chicken-shape. Wrap this tightly in cheesecloth and tie the ends securely.

Meanwhile the stock ingredients have been bubbling away. Let them have 2 hours before adding the bird, which also requires 2 hours once the liquid has returned to the boil. Keep it simmering gently, not galloping.

Take the pan off the heat, but don’t remove the chicken for another hour. You have to squeeze a good deal of liquid out of it, so you don’t want it too hot. On the other hand, don’t squeeze it dry either, and don’t put too heavy a board and weight on it – you want a succulent galantine. Forget about it overnight.

For the jelly, you use the simmering liquid. Strain it and taste. Reduce if necessary, or zip it up with extra seasonings, lemon juice, Madeira, port, sherry. Leave it in a bowl to cool – it will be much easier to remove fat from jelly than from liquid.

If the liquid doesn’t gel, or doesn’t gel firmly enough, add gelatine crystals (15 ml to 600 ml [½ oz to 1 pt]).

If the jelly is murky, clarify it.

Next day unwrap the chicken, very carefully, remove the button thread, and put it on a wire rack over a dish. Melt a little of the jelly until it just runs and brush it over the bird. You can then put some decorations on, once the jelly has reset. Brush on another layer to hold the decorations. When that has set, transfer the chicken to the final serving dish. Arrange round it chopped jelly, holding back some to whip into mayonnaise.

Everyone has their own ideas on decoration. But I would recommend the abstract and simple – tomato flowers and cucumber leaves raise suspicions that the cook has got something to hide. Picot-edged oranges and daisied eggs are for spoiling the fun at nursery teaparties, where chocolate biscuits and sardine sandwiches would be much more welcome, and at wedding receptions, where one begins truly to understand how England acquired her unenviable gastronomic reputation.

Sausage, saucisse, saucisson, derive ultimately from the Latin salsus, salted, probably by way of a Late Latin word salsicia, something prepared by salting. The Romans are, in fact, the first recorded sausage-makers, their intention being – as the derivation suggests – to preserve the smaller parts and scraps of the pig for winter eating. Though unwise to say so in a Frenchman’s hearing, the Italians are still the supreme producers of dried and smoked sausages. They use beef, as well as pork, but not usually donkey as some Frenchmen firmly believe.

For the fresh sausage, France is the country. It is still an honourable form of nourishment and pleasure there, protected by law from the addition of cereals and preservatives, produced in ebullient variety – both regional and individual – by thousands of charcutiers. In other words, the French sausage is freshly made, well-flavoured, and, apart from seasonings, 100 per cent meat. Inevitably you pay more than in England, but the money is better spent. For picnickers the sausage is an ideal alternative to pâtés; cook it in foil in hot wood ashes, or unwrapped on a metal grill. At the weekends, look out for the light puff-pastry sausage rolls, friandises, and on Sundays for the luxurious saucisse en brioche, which can be bought by the piece – though if you want to be sure of it, order on Thursdays, no later.

Although the meat is basically pork, from neck and shoulders and fat belly, a resourceful use of seasonings (spices, onions, sweet peppers, chestnuts, pistachio nuts, spinach, quite large amounts of sage or parsley, champagne, truffles) produces a variety of sausages that an English traveller, going through France for the first time, may find bewildering.

Making a good sausage is a simple affair, though you mightn’t think so from the nasty pink packages sold in grocers’ and butchers’ shops in this country. Even if you haven’t an electric mixer with a sausage-making attachment, you have two alternatives: prepare the mixture and take it in a bowl to your butcher for him to put into skins; or else buy a good-sized piece of caul fat as well as the pork and make crépinettes – little parcels of sausage-meat wrapped in beautiful veined white fat and either fried or grilled – or gayettes, or faggots which closely resemble gayettes. Some cookery books suggest frying the meat in a rissole shape, with perhaps an egg and breadcrumb coating, but crépinettes are a more succulent solution.

First of all, though, sausage-meat. It is so simple to buy the necessary lean and fat pork and put it through the mincer that I cannot see why butchers find it worth their while to sell sausage-meat, with its high proportion of cereal and its poor seasoning.

500 g (1 lb) lean pork from neck or shoulder

250 g (½ lb) hard back fat

1 level tablespoon salt

½ teaspoon quatre-épices, or spices to taste

freshly ground black pepper

plenty of parsley, or sage, or thyme

500 g (1 lb) lean pork from neck or shoulder

500 g (1 lb) hard back fat

1 rounded tablespoon salt

1 teaspoon spices or quatre-épices or cinnamon alone

freshly ground black pepper

plenty of parsley, or sage, or thyme

250 g (½ lb) lean pork from neck or shoulder

250 g (½ lb) veal

250 g (½ lb) hard back fat, or green bacon fat

seasonings to taste

250 g (½ lb) poultry, game

125 g (¼ lb) pork, lean

125 g (¼ lb) veal

250 g (½ lb) hard back fat

seasonings to taste

1 whole egg

1 level tablespoon salt

1 level teaspoon spices

Optional extras:

60 ml (2fl oz) brandy

30–60 g (1–2 oz) breadcrumbs

Put the lean and fat pork through the mincer once, or twice, according to the texture desired. Season.

Prepare as above.

Prepare as on page 175.

Note: if you want to bind these sausage-meats or forcemeats (farces), say for stuffing a bird, or making a pâté, remember these proportions: To 500 g (1 lb) of meat (lean and fat)

500 g (1 lb) pig’s liver

125 g (¼ lb) hard back fat

125 g (¼ lb) lean pork (neck or shoulder)

pieces of caul fat

2 cloves of garlic, crushed

salt, pepper and spices to taste

plenty of parsley, or other herb, chopped

Gayettes, a French equivalent to our West Country faggots, are often to be found in charcuteries and homely restaurants in Provence and the Ardèche, where they make a speciality of gayettes aux épinards (page 177). They look like faggots, very appetizing in their brown hummocky rows. Strictly for hungry picnickers on chilly days, when they taste delicious if you wrap them in a double layer of silver foil and reheat in wood ashes on the edge of the fire. The nonspinach gayettes are often eaten cold, in slices, as an hors d’œuvre. I recommend black olives with them, and plenty of bread and unsalted butter.

Mince the meat, season and wrap in pieces of caul fat – as for crépinettes, but gayettes are more the shape of small round dumplings. Lay them close together in a lard-greased baking dish. The oval, yellow and brown French gratin dishes are ideal.

Melt a little lard and pour over. Bake for 40 minutes in a medium oven. The top will brown nicely, and you can turn them over after 20 minutes, though this is not the conventional thing to do. Like faggots, gayettes are good tempered – you can stretch the cooking time with a slower oven and raise the heat to brown them at the end. Eat cold, sliced, as an hors d’œuvre.

From the charcutier’s point of view, gayettes are a way of using up the pig’s lungs and spleen. If you want to be really economical, you can do the same and ask the butcher for a mixture of liver, lights and spleen, with more liver than anything else. Cut off all the gristly bits when you get home, weigh the result, and add one-third of the weight in sausage-meat (half fat, half lean pork).

Then follow the recipe opposite.

250 g (½ lb) sausage-meat (half lean pork, half back fat)

250 g (½ lb) Swiss chard leaves, or spinach or perpetual beet (poirée)

250 g (½ lb) spinach (épinard)

a few leaves of garden sorrel (oseille)

60 g (2 oz) plain flour

a dash of hard liquor

caul fat

salt and pepper and spices

Wash the beet greens and spinach, shake off as much water as possible, and put in a pan over a low heat with a knob of butter or lard. No extra water should be needed, if you keep the pan covered and shake well from time to time to prevent sticking. Drain well, and chop with the uncooked sorrel. Stir in the flour, then the sausage-meat and seasonings. Finish like gayettes de provence, but eat them hot.

Note: Frozen spinach does quite well, follow instructions on the packet and dry thoroughly. Allow for different quantity.

If you can’t get beet leaves, use all spinach and a stalk of celery chopped finely but not to a mush.

If you can’t get sorrel, use a squeeze or two of lemon juice. Though I should say, go out and buy of a packet of sorrel seed immediately. Once sown, it’s there for ever, welcoming the spring with its clear sharp taste and lasting until the first severe frosts. Invaluable for soups, spinach purées and sauces for veal or fish.

On a row of hooks in the charcuterie, above the small, fresh sausages, the boudins blancs, and the boudins noirs, hang the medium-sized saveloy-type saucissons, for boiling and eating hot or cold. Beside them are ranged the very large keeping sausages (saucissons secs), which the charcutier sometimes makes himself, but which are usually supplied from a factory, as they are to delicatessen shops in this country. They are easy to recognize, meshed in string, wrapped in gold, silver and coloured foils, and cheerfully labelled. Like the fresh sausage, they must be all meat, predominantly pork – if horse-meat, for instance, is used, the label must say so. The more unfamiliar, black-skinned andouilles, or large tripe sausages (page 199), hang with them, slicing to a greyish-brown, beautifully marbled surface.

You can buy these sausages whole, for storing from hooks in your own larder, and in miniature for modern, small-family convenience, but mostly they are sold in slices, by weight. Eat them as they are, with hunks of bread and butter; olives go well too and can be bought at most charcuteries. A good picnic idea is to heat through some garlic sausage (saucisson à l’ail) and a piece of petit salé (cooked, pickled pork) with a large tin of pork and beans French-style (cassoulet, page 179).

In town charcuteries you will often find a variety of regional, national and international saucissons. Forget about the ones you know. Buy 50 g (just under 2 oz) of as many as you can afford – if they are well wrapped, then re-wrapped after the picnic, they will survive days of heat and car-travel in good condition. Often there will be local names, so point and don’t lose heart. French patience is endless in matters of food, even in busy shops. Explain that you would like to make an hors d’œuvre of as many kinds of saucisson as possible, particularly les spécialités de la région. One name that we always remember is gendarme, given to flat, strappy, yellow and brown speckled sausages in the Jura.

Buying saucissons in small quantities, whilst coping simultaneously with decimal weights and currency, one is only dimly aware of the high cost per pound. With an all-meat sausage you expect to pay more, but in the case of saucissons secs there is inevitably a good deal of shrinkage in the processes of drying and maturing, which pushes the price up higher still.

To make these sausages at home, you need skins made from the large intestine. If you have a farmhouse kitchen, with a solid fuel stove and plenty of old hooks attached to the beams, you are well away because the saucissons need to be dried at a temperature of 15°C (60°F), and a steady temperature at that. You can store them in a cooler larder when the drying is completed, but once again they should hang so that air circulates all round them. Avoid a steamy humid atmosphere.

As well as the right physical conditions, you need patience too because this type of sausage needs at least a month in which to mature, whether or not it is smoked; some kinds need six months. They will be covered with white powdery flowers from about the sixth day: ‘cette fleur est constituée par des micro-organismes de la famille des levures, qui préparent le climat idéal pour le développement d’autres microbes qui feront subir à la viande la transformation voulue d’onctuosité et de goût.’ In other words, leave the white organism alone to do its work of maturing the sausage. Don’t worry if the sausage shrinks, it will lose up to 40 per cent of its weight.

500 g (1 lb) haricot beans

a good-sized piece of pork or bacon skin, cut into squares

a knuckle of pork

500 g (1 lb) salt belly of pork

1 large onion stuck with 4 cloves

1 carrot

4 cloves garlic

bouquet garni

500 g (1 lb) boned shoulder of pork

750 g –1 kg (1½ –2 lb) preserved goose (confits d’oie), or duck, or either made up to weight with boned loin or shoulder of mutton

3 large onions, chopped

4 large skinned tomatoes, 3 tablespoons tomato extract

6 cloves of garlic, or according to taste

bouquet garni, salt and ground black pepper

beef stock

goose or duck fat, or lard

500 g (1 lb) Toulouse sausages, or saucisses de Campagne, or a large 500 g (1 lb) boiling sausage of the all-meat cervelas type, or the pork boiling rings sold in delicatessen shops

500 g (1 lb) saucisson à l’ail

plenty of white breadcrumbs to form a top crust

The tastiest form of baked beans is cassoulet, a rich slowly-cooked dish of dried white haricot beans, goose, salt pork, sausages large and small including the Toulouse sausage, small squares of pork skin to make the sauce smooth and bland, and breadcrumbs to form the crusty golden top. Languedoc is the native home of cassoulet, more specifically the small town of Castelnaudary on the Canal du Midi, whose classic version was described by Anatole France as having ‘a taste, which one finds in the paintings of old Venetian masters, in the amber flesh tints of their women’. At Toulouse and Carcassonne cooks add mutton and partridge.

This dish needs careful planning and preparation. It is not cheap. The ideal time to choose for it is when you are able to have a goose: keep the legs to one side, turn them over daily in a mixture of 60 g (2 oz) unadulterated salt and a small pinch of saltpetre. Invite your guests and assemble the other ingredients.

Good beans are worth an effort. Most grocers sell dried white haricot beans vaguely described as Foreign. Better quality and a creamier texture are to be found in Soho, where grocers import beans from France, varieties known as Soissons and Arpajon from the market-gardening centres near Paris where they were first developed. Like geese, dried beans are at their best in the autumn; with time they become drier and harder and harder and drier, so beware the grocer with a slow turnover.

The other main requirement is a deep wide earthenware pot in which all the ingredients are finally amalgamated. Correctly a cassole or toupin, any earthenware or stoneware casserole will do, provided it is deep and wide.

Soak the haricot beans overnight. Drain and put them in an earthenware pot with the other ingredients; cover with water. Bring to the boil, and cook in a gentle oven for 1½ hours, or until the beans are tender but not splitting.

Meanwhile prepare the pork and goose ragoût. Put the chopped onions on to melt to a golden hash in a large frying pan (preferably cast iron). Cut the various meats into eating-sized pieces, or joints, and add them to the onions. Turn up the heat a little so that they can brown, without burning. Pour off any surplus fat, then add the tomatoes skinned and chopped into large chunks, and a little stock, about 150 ml (¼ pt), to make enough sauce for the meat to continue cooking in. Flavour with concentrated tomato extract and seasonings, push the bouquet garni into the middle. Cover the pan, and keep the contents at a gentle bubble until the beans are ready – about 30 minutes.

Add the large saucisson à l’ail and the cervelas to the beans, so that they have 30 minutes’ simmering. If you are using sausages, stiffen them in a little goose fat or lard for 10 minutes.

When the beans are cooked, drain off and keep the liquid; remove the onion, carrot, bouquet garni, and knuckle bone, and slice the salt pork and knuckle meat. Use the bacon skins, or pork skins, to line the deep earthenware pot you intend to use for the final cooking. Put in half the beans, then the pork and goose ragoût, the sliced meats from the bean cooking pot, the small and large sausages, and the rest of the beans. Pour over 150 ml (¼ pt) of the bean liquid, and finish with a 1-cm (½-inch) layer of breadcrumbs dotted with pieces of goose fat or lard.

Cook very slowly, about gas 2, 150°C (300°F), for 1½ hours. The crust will turn a beautiful golden colour, and traditionally you should push it down with a spoon 3–7 times, so that it can re-form with the aid of another sprinkling of breadcrumbs.

The point of this last cooking is to blend all the delicious flavours together gently, without the meat becoming tasteless and stringy. Everything has, after all, already been cooked. If you find that the cassoulet is becoming too dry, add a little more of the bean liquid, but don’t overdo this.

The quantities can be varied; the essentials are beans, sausages, pork and goose (or goose and mutton, or a small roasting duck). Pork and beans alone are very good (see next page, and recipes for Boston baked beans, etc.), but it is the goose or duck that makes the difference.

This is an ideal dish for a winter’s Sunday lunch-party – it pleases everybody from children to grandparents. The cook should be pleased too, because her guests should not be allowed to eat too much beforehand, and can’t eat much afterwards, so her labours are cut to a minimum.

500 g (1 lb) haricot beans

pieces of fresh pork skin

500 g (1 lb) piece of petit salé, uncooked, or brine-pickled pork belly

1 large French sausage of the boiling type, or small smoked sausages

8 cloves of garlic

90 g (3 oz) lard, goose, duck or chicken fat

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

Here is a simple family version of cassoulet. An excellent filler on a cold day, which can be prepared after breakfast – if you omit the sausage, or use small ones – and left to look after itself until 30 minutes before lunch.

Soak the beans overnight.

Next day line the casserole with the fresh pork skin, outside down, and put the piece of pork on top. If you use petit salé, make sure that the salt is washed off first. Pack in the beans around and on top. Just cover with water, and put on a close-fitting lid. Give it 3 hours in a slow oven, gas 2, 150°C (300°F). Add no salt at this stage.

If you use a large sausage, add it 1 hour before the end of cooking time. If you use small sausages, add them 30 minutes before. Taste the cassoulet whilst you do this and add salt, pepper, etc. Make the beurre de Gascogne by blanching the cloves of garlic in salted boiling water for 5–10 minutes. Pound them to a paste adding the 90 g (3 oz) of fat and finally the parsley.

Just before serving, strain off the liquid from the beans and pork, taste again and adjust the seasoning. Mix in the beurre de Gascogne at the last moment before serving.

Note: if you have no pure fat or dripping, use olive oil or butter.

1 good crisp Savoy cabbage

500 g (1 lb) salt belly of pork, or green streaky bacon in a piece

a large piece of pork skin

3 leeks, sliced

6 medium-sized potatoes

12 new carrots, or 4 old ones cut in pieces

4 small onions

a piece of garlic sausage, or boiling sausage (saucisson à I’ail)

green beans and peas, if in season

Toulouse or Country sausages, or dried or smoked sausages

Potée is basically a cabbage soup, in the way that cassoulet is basically beans and pork. But the addition of other vegetables as well as sausages and pickled meat makes it a complete meal in one pot, again like cassoulet. In the south-west of France, this thick soup is called garbure and contains, inevitably, confits d’oie. Country housewives use what they have to hand in their own kitchens and attic store, so the ingredients vary; but here is a suggested list and basic method.

Cut the cabbage into quarters, plunge it into boiling water to blanch for 10 minutes. Leave it to drain.

Put the pork or bacon and pork skin in a pot and cover with water. Don’t add salt. Simmer for 30 minutes.

Add the leeks, potatoes, carrots and onions, and any other root vegetables you want to use. Simmer for 30 minutes. Add the garlic sausage, peas and beans – and the smoked or dried sausages if you are using them. Simmer for 30 minutes.

Meanwhile slice up the blanched cabbage, stiffen the fresh sausages for 10 minutes in lard or butter, and add them to the potée 5 minutes before serving. Remove the piece of salt pork, so that it can be sliced too, then returned to the pot. Taste, and correct seasoning.

One French custom is to add thick slices of wholemeal bread just before serving the soup, but it is usually best to leave people to do this for themselves in case they are watching their weight. A more popular tradition is the addition of a glass of red or white wine to the last few spoonfuls of soup in one’s plate – this is known as a goudale in the Béarn, where much garbure is consumed.

COOKING AND CARVING

With home-cured ham particularly, make absolutely sure that it is still good before you cook it. It should smell unsuspicious and appetizing. Push a larding or metal knitting needle right into the middle of the ham, it should come out clean and sweet.

Soaking

The point of soaking is to remove excess salt, and to restore moisture to the dried-out tissues.

It follows therefore that salt pork and very lightly cured hams (Jambons de Paris) need no soaking.

On the other hand, home-cured hams, which have been subjected to a prolonged curing followed by smoking, need to be left in water overnight. With commercial hams, follow the instructions provided with them. Otherwise make enquiries from the supplier. For mild cures 4–6 hours soaking may well be enough.

Very large hams need longer than small hams cured in the same way.

But don’t worry. You will have a further chance to rectify saltiness in the cooking process.

Cooking utensils

Borrow or buy a ham kettle.

If this is impossible, try to find a pot large enough to hold the ham with plenty of water. In the case of a large ham, a washing copper is a good solution. This also enables you to suspend the ham, by a strong, clean cord, so that the more quickly cooked knuckle end is out of the water.

Cooking

Weigh the salt pork, or soaked ham. Calculate the cooking time. Salt pork and smaller hams, up to 2 kg (4 lb), reckon 30 minutes per 500 g (1 lb), plus an extra 30 minutes. But watch the joint – the last 30 minutes may be unnecessary: if so, take the pot to the side of the stove and leave the joint in the liquid to keep hot. Or glaze it in the oven.

Hams of 2½ kg (5 lb) and over, up to 5 kg (10 lb), 20 minutes per pound, plus 20 minutes. Hams of 5 kg (10 lb) and over, the period of time gets progressively less. (See table)

| Cooking times for large hams | |

| 6 kg (12 lb) | 3 hours 30 minutes |

| 7 kg (14 lb) | 3 hours 45 minutes |

| 8 kg (16 lb) | 4 hours |

| 9 kg (18 lb) | 4 hours 15 minutes |

| 10 kg (20 lb) | 4 hours 30 minutes |

| 11 kg (22 lb) | 4 hours 45 minutes |

| 12 kg (24 lb) | 5 hours |

| 13 kg (26 lb) | 5 hours 15 minutes |

Put the joint or ham into the pot, cover with plenty of cold water and bring slowly to the boil. Count your cooking time from now, and keep the water at a simmer. After 10–15 minutes, taste the water. If it is unpleasantly salty, throw it away and start again, reckoning the cooking time from the second boiling point, less 10–15 minutes.

Finishing – cold ham

When the ham is cooked, leave it to cool for 1–2 hours in the liquid. Then remove it, and take off the skin. Toast plenty of white breadcrumbs and press them into the fat of the ham whilst both are still warm.

(If the ham was cooked boneless, let it cool for 1 hour in the liquid, remove the skin, and press the ham, either with a board and weight, or with a weight into an appropriately-shaped mould. Remove string afterwards, and cloth, if it was cooked in a cloth.) Leave the ham to set in a cool place for 12 hours. This makes it much easier to carve.

Finishing – hot ham

The simplest and most attractive way to finish a hot ham is to glaze it.

Remove the ham from the cooking liquid 30 minutes before the end of cooking time. Peel off the skin, and smear the ham with, for instance, a mixture of brown sugar and French mustard, or brown sugar and mustard powder, moistened with a little of the cooking liquor.

Put it in a moderate oven for the rest of the cooking time.

There are endless variations and complications on this theme. You can invent more for yourself, remembering that the most successful glazes combine sweetness and spiciness. One attractive finish is achieved by scoring the fat of the ham in a lattice pattern, studding the intersections with cloves, and then smearing the glaze on gently. Be careful not to score right through the fat to the lean. The juices from the glazing can be turned into the sauce, with a little extra liquid from the boiling operation, or cream, or a wine like Madeira, Marsala, port, sherry, etc.

Carving

The essential requirement is a very sharp knife, preferably one with a long, thin blade.

Remember that there are right and left hams, if your ham has been cooked on the bone. If the ham is boneless and pressed, you will carve it straight down, so right and left are of no consequence. The knuckle must lie towards the carver – to his left for a right-hand ham, and to his right for a left-hand ham. Cut each slice from alternate sides, as thinly as possible with an even smooth movement of the knife – this prevents a ridgy appearance.

Cook the ham in a bouillon for three-quarters of its cooking time – reckon 20 minutes per 500 g (1 lb) plus 20 minutes, from the time it reaches simmering point. See page 184.

Skin the ham and transfer it to a closer-fitting pot. Pour ½ litre (¾ pt) of Madeira, put on the lid and cook in a moderate oven for 50 minutes or the rest of the cooking time – whichever is the longer.

Transfer the ham again to a shallow dish, sprinkle it with icing sugar, or a brown sugar, spices and French mustard glaze, and put it to melt in a hot oven. See that it doesn’t burn but turns to a succulent golden sheen.

Meanwhile deal with the sauce. Taste the braising liquid – add some stock or Madeira, reduce it or leave it alone, according to your judgement. Thicken it by adding a little knob of beurre manié (1 tablespoon of flour kneaded into ½ tablespoon of butter).

Variations and accompaniments

Use another fortified wine – Marsala, port, sherry, or any heavy wine, instead of Madeira.

Serve with a cream sauce made by reducing the braising liquid and adding 300 ml (½ pt) of double cream. Surround the glazed ham with little piles of vegetables cooked in butter (new carrots, tiny onions, mushrooms, young peas, young green beans). This is jambon à la crème.

Serve jambon à la crème with a purée of spinach, or spinach and sorrel, instead of the little piles of vegetables. Get the spinach as dry as possible and flavour the purée with a little sugar, salt, pepper, cheese, cream as you think fit – spinach varies so much that you have to use your discretion. If you do grow sorrel, add a few leaves for their sharp, spring flavour.

Belgian chicory (witloof or endive de Bruxelles), blanched for 15 minutes in boiling water, then braised in butter in the oven, makes a good accompaniment to jambon au Madère.

Most popular of all, jambon au Madère, or à la crème, served with young green peas and new potatoes in the early summer.

This is the famous and beautiful Eastertide dish of Burgundy. The major requirements are plenty of white wine, the ham, plenty of parsley, and one of those old-fashioned bedroom wash-bowls. I use a leg of pork cured in the York or American style, or a 1½ kg (3 lb) piece of gammon. It goes into a ham kettle with plenty of cold water, which is slowly brought to the boil to draw out excess salt. Pour off the water if it is very salty and start again. When the water is once more at the boil, simmer the ham very gently for 45 minutes.

Remove from the water and cut the meat off the bone in sizeable chunks. Put them into a pan with a large knuckle of veal, chopped into pieces; 2 calf’s feet, boned, and tied together; a few sprigs of chervil and tarragon tied together with a bay leaf, 2 sprigs of thyme and 2 sprigs of parsley; 8 peppercorns tied into a little bag. Skim off fat as it rises, and leave the ham to cook very thoroughly, as it will need to be mashed and flaked with a fork.

However, before you do this, attend to the jelly. Pour off the cooking liquid through a strainer lined with a piece of clean cotton sheeting. Taste it to make sure it is not too salty. Add 1 tablespoon of white wine vinegar, and leave it to set a little.

Meanwhile crush the ham into a bowl.

Before the jelly sets altogether, stir in plenty of chopped parsley – at least 4 tablespoons, and pour over the ham. Leave to set overnight in a cold place. Turn out the jambon persillé, and serve. When it is cut, it will display a beautifully marbled, green and pink appearance. If you like you can keep back some of the parsley jelly, remelt it gently next day and pour over the ham in an even green layer.

250 g (½ lb) lean cooked ham

30 g (1 oz) butter

30 g (1 oz) flour

a generous 125 ml (¼ pt) milk, or single cream

3 egg yolks

3 egg whites

salt, pepper

Mince the ham twice and pound to a smooth mass in a mortar. Make a very thick white sauce with butter, flour and milk or cream, cooking until it comes away from the side of the pan. Use a wooden spoon for stirring. Add the ham and season well.

If you have an electric blender, mince the ham once or chop it roughly. Put it in the blender goblet with the thick white sauce and whirl at top speed. Reheat in the pan, but not to boiling point. The egg yolks should now be added, one by one.

Beat the egg whites until they are stiff, fold lightly into the pan mixture with a metal spoon, and pour into a soufflé dish with an oiled greaseproof collar.

Bake in a moderate oven for 25 minutes. Serve immediately – remember to remove the paper collar – to seated guests.

This soufflé can be cooked in small individual soufflé dishes. They will only take about 10 minutes to cook and the oven should be hotter than for a large soufflé.

This delightfully named hot sandwich, can be served as an hors d’œuvre.

Choose good bread, milk loaf, pain de mie or pain brioché. Cut thin slices, butter them, and make them into sandwiches with a layer of Gruyère cheese and a layer of lean ham on top. Cut into elegant triangles, and fry in half butter, half oil, until they are golden brown, on both sides.

Variation

Fry slices of bread on one side only, butter the unfried side, lay thick slices of ham on top and cover with a paste made of grated Gruyère cheese, French mustard and thick cream – enough to make the mixture spread. Grill gently until gold and bubbly – serve on very hot plates.

The most obvious, visible difference in the French cooking of fresh pork – apart, of course, from the elegant butchery – is the lack of crackling. In the charcuterie, the porc rôti will be a neat boneless cylinder, pale pink from its night in brine, studded with an occasional clove of garlic, and sold by the succulent slice.

The outer layer of fat and skin will have been used in pâtés, sausages and crépinettes. If the charcutier is the butcher as well, you will see nicely-cut oblongs of white fat barding the lean roasts of beef. If you want to buy a fillet of beef for roasting, you can also buy fat to cut into larding strips. The skin, la couenne, is available too, for additional flavour and texture in beef casseroles. Crackling is not unknown in France, but it is served quite separately from roast pork.

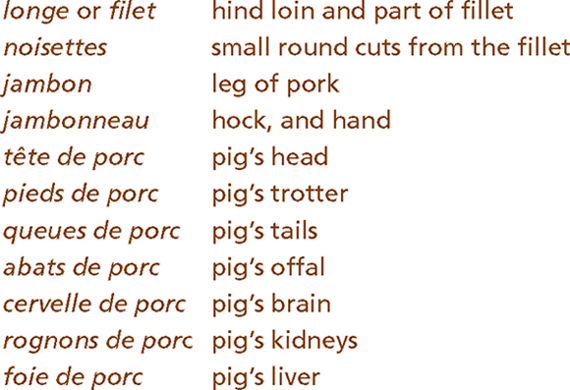

The finest roasting joint of all is the loin, usually divided into two on account of its length. The leg end is known as the filet or longe, and the smaller end as the carré. When the filet is cut into chops it becomes escalopes, or the small round noisettes. When the carré is cut into chops, it becomes côtes and the smaller côtelettes.

The leg, together with the loin, are the parties nobles of the pig, but the leg is most usually turned into ham. The French for both is jambon (though gigot is often used for a fresh roasting leg), and the adjective frais to designate an uncured leg is often omitted. Be careful of this when using a French cookery book, or an English one derived from French sources. Read the recipe very carefully before visiting the butcher, and decide which is most likely – fresh leg of pork, gammon or cooked ham.

The cheaper joints of pork benefit even more than leg and loin from being salted in brine before they are cooked. Boned shoulder of pork (épaule désossée), for instance, spare ribs (échine) and blade bone (palette), and the often despised belly of pork (poitrine), gain in flavour and tenderness for three days in saumure anglaise. They can then be stewed or braised to advantage, or simmered in water and finally glazed. Try combining belly of pork, salted or not, with shin of beef in the casserole; the pork supplies a bland smoothness which greatly improves the flavour and texture of the sauce.

The extremities of the pig can also be eaten fresh (page 195).

ROASTING

Unlike beef or lamb, there is nothing to be gained by undercooking pork. Indeed it is neither desirable nor safe to do so. Pork should be well and gently cooked, whatever the cut and whatever the method of cooking used.

Prepare a joint of pork for roasting by boning, salting, marinading or seasoning. Then weigh it, and reckon 30 minutes’ cooking time for joints up to and including 2 kg (4 lb). Add 20 minutes per 500 g (1 lb) for each 500 g (1 lb) over. Put the joint on a rack in the roasting pan, and set it in a low oven, gas 3, 160°C (325°F). There is no need to add fat or water. Test the joint near the end of the cooking time with a larding or knitting needle. The liquid which oozes out should be colourless. If it is pink the joint is not ready.

Make a sauce from the pan juices after pouring off excess fat, according to taste and recipe.

An hour before the pork is cooked, add small new carrots and tiny onions to the roasting pan. Turn them over from time to time so that they glaze. Serve the vegetables round the meat, garnish with parsley. If small new potatoes are cooked in the pan as well, you have pork à la bonne femme.

Shell and simmer 500 g (1 lb) chestnuts for 20 minutes, blanch 500 g (1 lb) of small onions, and add them with a few rolls of bacon to the pork 45 minutes before the end of cooking time.

An attractive way of serving chestnuts with pork or ham is to cook them to a purée, flavour with pan juices from the pork or crumbs of crisply fried bacon, and serve it in small barquettes or tartelettes of short pastry, baked blind.

Sage is not often associated with pork in France, but if you grow it, here is a way of combining it with pork in the French style (don’t use dried sage):

Make incisions in the joint of pork and insert small sprigs or leaves of sage. Mix 1 tablespoon of salt, 1 tablespoon of thyme, and half a bay leaf crushed, and rub this over the fat and boned sides of the joint. Leave overnight. Rub the seasoned salt in again next morning, before tying up the joint for roasting.

In Provence, plenty of crushed garlic, breadcrumbs and some olive oil are mixed together into a paste, and this is spread over the joint 45 minutes before the end of cooking time. It forms an appetizing golden crust.

The first two methods amount to much the same thing in the case of pork, as the meat is moist enough to require very little additional liquid. What moisture there is, is conserved by covering the pot with a tight-fitting lid, which means that it is a good method for cheaper joints of pork. If you tell the butcher that you wish to braise a joint en casserole, he will probably give you a piece of échine (spare ribs and blade bone joint), or the fillet end of the leg.

Here is a typical way of pot-roasting very popular in small French villages, where not everybody has an oven.

Choose a heavy cast-iron pan, melt some lard in it, or butter and oil, and brown the neatly-tied joint of pork all over, including the two ends. Warm some eau-de-vie de marc, brandy (or vodka) in a small pan, set alight to it and pour over the browned pork.

Add a mirepoix of carrots and onions, some crushed garlic and a large glass of rosé wine – about 150 ml (¼ pt). Grind salt and pepper over, put on the lid and turn the heat down low enough to keep the liquid gently bubbling. Allow 30 minutes per 500 g (1 lb).

Turn the meat over from time to time. Add new potatoes for the last 30 minutes.

Taste the sauce and adjust the flavour and seasoning as you like. Skim off the fat. The French like their jus or gravy to be concentrated and well-flavoured – this means that there can’t be a vast quantity of it, just a spoonful or two for each person.

Some farmers say that if the pork is accompanied by a hash of onions, sautéed in butter and flamed in brandy, it will keep you sober through a day’s hard drinking. Recommended for market-day breakfast.

Use a cast-iron pot which has been enamelled if you can – otherwise the sauce turns a disconcerting blackish colour, due to the wine. It tastes all right, but the appearance may put people off.

375 ml (½ bottle) white Vouvray (drink the other half with the dish)

500 g (1 lb) large Californian prunes (unless you can find prunes from Agen)

salt, pepper, a little flour

2 noisettes or 1 chop per person

1 tablespoon redcurrant jelly

300 ml (½ pt) thick cream

a dash of lemon juice

This bland combination of pork, prunes, cream and the white wine of Vouvray embodies what Henry James described as ‘the good-humoured and succulent Touraine’. The wine is made – as the best white wines are – from grapes which are almost rotting on the vines. As local vignerons say: ‘They piss in your hand’. The first time I made this dish I couldn’t afford the Vouvray, so I improved on the very ordinary white wine in the larder by using Christmas prunes, which had been steeping in a mixture of half marc, a crude eau-de-vie, and half syrup. Delicious, if unorthodox.

Put the prunes to soak overnight in the Vouvray. Next day pour off about 60 ml (2 fl oz) of the liquid, and put the rest of it with the prunes into a slow oven to cook. Three-quarters of an hour is enough, but in fact you can leave them there for up to 1½ hours provided they simmer slowly enough. Cover them so that the juice does not evaporate.

Season and flour the noisettes. Cook them gently in the butter on each side, making sure that the butter doesn’t go brown. Add the 60 ml (2 fl oz) of steeping juice and leave the pork to cook for 40 minutes with a lid on the pan.

Pour on the juice from cooking the prunes. Cook for 3 minutes then remove the pork to a large flat serving dish, and arrange the prunes around the noisettes whilst the sauce in the frying pan boils down to a thinnish syrup. Add the redcurrant jelly, then the cream bit by bit, stirring it in well so that after each addition it is properly amalgamated. Because English cream doesn’t have that slightly sour tang of French cream, I add a dash of lemon at the end before pouring the sauce over the noisettes and prunes. Leave in the oven for 5 minutes. Serve this dish on its own.

These methods involve the small cuts of pork, and are virtually interchangeable according to your circumstances. If you have really good pork chops, grill them. If you are in the least bit dubious, fry or braise them. Either method should be applied gently – unlike fillet steak, pork chops will take about 20 minutes under the grill, or in the sauté pan.

After a long day’s work, or excursion, grilled pork chops are everybody’s solution to the evening meal. With a little forethought, you can improve on everybody else’s solution and enjoy a much better meal.

Season the chops. Put previously cooked potatoes into a pan with milk, to heat through for mashing.

Grill the chops fast for 1 minute, then lower the heat and give them 9 minutes. Turn over, and repeat with 1 minute fast, and 9 minutes slow.

Deal with the potatoes, adding plenty of butter and nutmeg or mace; arrange the chops round them and put the dish into the oven whilst you make the sauce.

Take the rack out of the grill pan, pour in some white (or rosé) wine, bubble it all together on top of the stove. Taste and season.

Be sure to scrape in all the little brown bits. Pour over the chops and serve. Have French mustard on the table.

(Watercress always makes a good appearance with pork chops.)

A delicious way of serving pork chops from Avesnes-sur-Helpe in the very north of France. The method can be adapted for use with other glazing mixtures; but this French rarebit style is the best of all.

Grate a quantity of Gruyère or Emmenthal cheese (60 g [2 oz] is enough for 3 chops), mix it to a thick paste with half-and-half French mustard and cream. It should spread but not run.

Grill the chops on both sides as in the recipe for côtes de porc au vin blanc. When they are done, spread one side of each chop with the Gruyère paste and set under the grill. The mixture will melt, bubble and turn gold.

One of the most appetizing ways of serving pork, the smell is irresistible and draws the whole family into the kitchen.

Pig’s head, like the other extremities, is sold cheaply in this country. It makes an excellent brawn (fromage de tête, hure) or galantine, if suitable attention is paid to its preparation. Anyone can grill a steak or chop; the cheaper cuts require careful and sophisticated cooking.

This does not mean that the methods are difficult or tortuous, but they do require judgement and care over detail. Lack of proper care, above the statutory requirements of hygiene, and insensitivity to flavour make many manufactured meat dishes in England uneatable. This commercial debasement of brawn, black puddings, meat pies and sausages has misled people into feeling that only the expensive parts of a pig are worth eating.

There is little difference between fromage de tête and hure and galantine de porc. Fromage is a mixture of the meat set in jelly, hure is a mixture of the meat enveloped in the skin of the head, galantine is a mixture of the meat with hardly any internal jelly, but a coating of jelly round the outside.

I once commented on the limited variety of prepared and cooked pork on sale in this country to an executive in a large pork factory. He recalled that in the early days of this century the Managing Director always had pig’s trotters to start his important dinner parties, but that nowadays the housewife was ashamed to be seen coming out of the butcher’s shop with a packet of trotters and tail. In France there is usually a tray of them in most charcuteries, breadcrumbed (pieds panés), waiting to be taken home and grilled for an hors d’œuvre. As one is lucky enough to buy them so cheaply in England, I usually serve them in various ways for a main luncheon dish, accompanied by mashed potato. They have often spent 48 hours in brine, but this is not essential, though it certainly improves their flavour.

The most famous of all the French ways of cooking pig’s ears and pig’s trotters, the Sainte-Ménéhould method, gives a crisp texture to gelatinous meat, which has been boiled, by rolling it in breadcrumbs, then grilling or frying. But in Sainte-Ménéhould itself, in the Argonne where pigs once ran in the huge woods of the plateau (scene of much of the Verdun fighting in the First World War), pig’s trotters with a difference can be bought for reheating. Spiced with quatre-épices and rolled, like pieds panés in breadcrumbs, they have been cooked for so long – 48 hours – that they can be eaten bones and all. This gives three textures – crisp, gelatinous and the hard-soft biscuit of the edible bones. An extremely delicious combination. They are served in local hotels quite dry, without sauce, and you eat them with French mustard.

One charcutière told me that it’s the addition of a certain vegetable or herb that causes the bones to soften, as well as the prolonged slow cooking. Local sceptics tartly hint at ‘produits chimiques’.

Andouilles are large, invariably salted and smoked, sold in slices by weight, like salami, and eaten cold. Andouillettes are smaller, the size of a large sausage or a little bigger, occasionally smoked or salted, and eaten hot after a gentle grilling.*

If the charcutier orders his andouilles from Vire in Normandy, the capital of the andouille, they will be hanging up among the other saucissons secs. They are easily distinguishable on account of their black skins and their mottled greyish-brown section, with the pieces of tripe looking like the fossilized coral in Frosterley marble, or else graded by size and drawn into each other, so that the slices look like regular growth rings across a tree-stump. If the charcutier makes his own, they may well be a lot smaller, about the size of a man’s clenched fist and about as knobbly. Their skins are probably more succulent and wrinkled black, and when you go near to choose one your mouth waters with their sharp smell of a white wine marinade.