IT WAS ONLY YESTERDAY, or so it seems, that you brought that precious little bundle home-only yesterday that you gazed at those teeny-tiny feet, changed that first diaper, smoothed lotion on that silky newborn skin, witnessed that first toothless grin, and watched in amazement as those numbers on the scale crept up at each baby weigh-in. Fast-forward one year (my, how time flies!) and those tiny feet are now a whole lot bigger, sometimes look a little funny (what’s up with that tiptoeing?), and are in need of some walking shoes. That toothless grin has turned into a mouthful of teeth that have to be cared for. That silky skin, part of a body always on the go, is exposed to a plethora of skin-chafing elements. And diaper contents are a little more mysterious these days (is that blue poop?), even as diaper changes become ever more challenging. But as much as your little one has grown (all too fast), he or she still has plenty of growing left to do... leaving you with a growing list of questions about everything from head to toe-and in between.

Whether it’s a mass of ringlets or a fine coating of down, every toddler’s hair needs some daily care, if only to remove lunch from it. Here’s what you need to know:

Shampoo only as needed. Since oil glands on the scalp, like oil glands elsewhere on the body, don’t become fully functional until puberty, daily shampoos are rarely necessary–except for toddlers who tend to get a lot of food, sand, or dirt in their hair, or those who have particularly oily scalps. Many toddlers-especially those with African hair, or those with very dry hair or scalps-are best off with just a weekly shampoo (they may benefit from a little oil rub every now and then, too). Others require a shampoo every other day or even every third day-though more frequent shampooing is often needed in hot weather, when hair gets sweaty and sticky faster. Be sure to rinse well-a soapy residue can become a magnet for grime.

Shampoo only as needed. Since oil glands on the scalp, like oil glands elsewhere on the body, don’t become fully functional until puberty, daily shampoos are rarely necessary–except for toddlers who tend to get a lot of food, sand, or dirt in their hair, or those who have particularly oily scalps. Many toddlers-especially those with African hair, or those with very dry hair or scalps-are best off with just a weekly shampoo (they may benefit from a little oil rub every now and then, too). Others require a shampoo every other day or even every third day-though more frequent shampooing is often needed in hot weather, when hair gets sweaty and sticky faster. Be sure to rinse well-a soapy residue can become a magnet for grime.

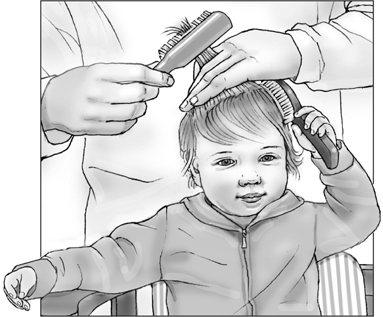

Choose the right tools. Think gentle when you select brushes and combs. A brush should be flat, rather than curved, and have bristles with rounded ends. If your child has tight, curly hair, the bristles should be long, firm, and widely spaced. A comb-very useful for detangling, and a must-have for children with extra-thick, frizzy, or African hair-should have widely spaced, nonscratchy teeth.

Choose the right tools. Think gentle when you select brushes and combs. A brush should be flat, rather than curved, and have bristles with rounded ends. If your child has tight, curly hair, the bristles should be long, firm, and widely spaced. A comb-very useful for detangling, and a must-have for children with extra-thick, frizzy, or African hair-should have widely spaced, nonscratchy teeth.

Brush up. Brushing helps to bring oil to the surface of the scalp, and that can be especially helpful if your toddler’s scalp or hair is dry. It can also remove much of the food and dirt that works itself into toddler hair. But use a light touch when brushing or combing your toddler’s hair, avoiding tugging or yanking. See the question that follows for detangling tips.

Brush up. Brushing helps to bring oil to the surface of the scalp, and that can be especially helpful if your toddler’s scalp or hair is dry. It can also remove much of the food and dirt that works itself into toddler hair. But use a light touch when brushing or combing your toddler’s hair, avoiding tugging or yanking. See the question that follows for detangling tips.

Don’t share when it comes to hair. As far as hair care implements are concerned, sharing isn’t a virtue. Each member of the family should have his or her own comb and brush, and, to prevent transmission of head lice or other problems, should keep these styling tools to themselves. Combs and brushes should occasionally be washed in suds made with a dash of shampoo and warm water.

Don’t share when it comes to hair. As far as hair care implements are concerned, sharing isn’t a virtue. Each member of the family should have his or her own comb and brush, and, to prevent transmission of head lice or other problems, should keep these styling tools to themselves. Combs and brushes should occasionally be washed in suds made with a dash of shampoo and warm water.

“My daughter puts up a fight whenever I try to brush her hair. But when I don’t brush it, the tangles just get worse and worse.”

Getting the brush-off when you try to brush your toddler’s hair? Few toddlers like to sit still for styling, or even for the most cursory comb-out-and some start screaming and struggling the moment they spy a hairbrush headed their way.

Even though many 1-year-olds don’t have a whole lot of hair to contend with, the hair they do have is often fine, delicate, and sometimes fragile–making the daily chore of brushing even more challenging. Multiply the hairs (some tots have a headful), and multiply the challenges.

To take the trauma (for both of you) out of detangling:

Open a salon. Set up your toddler on a chair or high chair in front of a mirror and play “hair salon.” While you’re primping your client, allow her to primp one of her own: Supply her with a favorite long-haired doll or stuffed animal and a hairbrush to style with.

Take two to untangle. Your toddler will be less likely to resist hair brushing if she’s participating in it. When she gets tired of brushing her doll’s hair, let her brush her own. You take the left side, and let her take the right. Then switch sides so you can go over what she’s done. Or simply take turns ("Now it’s my turn to brush”). Just be sure you get last licks. If you’re brave enough, you can even let her tackle your hair with a comb or brush (but be ready to do some major detangling afterward).

Tackle tangles gently. A toddler’s scalp-like all of her skin-is tender, especially if it isn’t protected by much in the way of hair. So have an extra-gentle touch. Use a wide-tooth comb (fine-tooth ones can tug and tear) or a brush that has bristles with rounded tips. To reduce pulling, hold the hair at the roots while you work on the ends. For longer hair, try a spray-on detangler to help untangle between shampoos.

Curtail tangling. Sometimes the easiest way to deal with a problem is to get rid of it. If your toddler’s tresses are on the long side, consider a short, low-maintenance haircut-it’ll make untangling a breeze. Or try braiding (but don’t pull too tightly-it can cause hair loss) or putting it up in pigtails. Hair that’s worn loose isn’t just vulnerable to tangles, but to sticky globs of food, mud, paint, and more-all of which can dry into major roadblocks for the comb and brush.

Allowing your toddler to brush her hair while you work on the tangles may make the job easier.

No matter what your child’s hairstyle, combing out tangles before each shampoo will make combing out after the shampoo less of a trial. So will smoothing suds through the hair (instead of vigorously working hair up into a snarl when lathering), and using a tangle-reducing conditioner (or a shampoo-conditioner combo) that’s designed for babies and toddlers.

Take bows (or barrettes) when it’s over. Do her hair up with pretty accessories (let her choose them) as the reward for sitting through the brushing. And don’t forget to reward your toddler’s “client” the same way. Do be sure, however, that your tot can’t take off any small (and potentially chokeable) accessories from her hair on her own. For safety’s sake, remove small barrettes or bows from your toddler’s hair before putting her to bed, and store them safely out of her reach.

“To say washing our son’s hair is a struggle is an understatement. Is there any way to make it less of a hassle?”

Hair washing can be hair-raising when you’re trying to suds up and rinse a toddler. But you can minimize the struggles if you keep these shampoo-surviving techniques in mind:

Keep your cool. If you anticipate a struggle, you’re sure to get one-so approach hair washing calmly. You may get the struggle anyway, but the more unflappable you are, the less flap you’ll get.

Keep your cool. If you anticipate a struggle, you’re sure to get one-so approach hair washing calmly. You may get the struggle anyway, but the more unflappable you are, the less flap you’ll get.

Keep it streamlined. Have everything at the ready when you begin (water at the perfect temperature, shampoo and a towel nearby) so that neither of you needs to endure the shampooing ordeal any longer than necessary. To reduce the number of hair-washing steps, use a one-step conditioning shampoo instead of shampoo plus separate conditioner. Or spray on a no-rinse detangler after you’ve rinsed out the shampoo.

Keep it streamlined. Have everything at the ready when you begin (water at the perfect temperature, shampoo and a towel nearby) so that neither of you needs to endure the shampooing ordeal any longer than necessary. To reduce the number of hair-washing steps, use a one-step conditioning shampoo instead of shampoo plus separate conditioner. Or spray on a no-rinse detangler after you’ve rinsed out the shampoo.

Keep it short. The shorter the hair, the shorter the shampoo. If your toddler’s hair is long or hard to deal with, consider an easy-care cut.

Keep it short. The shorter the hair, the shorter the shampoo. If your toddler’s hair is long or hard to deal with, consider an easy-care cut.

Keep it gentle. Always choose a shampoo that won’t irritate skin or eyes (most baby and toddler shampoos are gentle, but sensitivities vary from child to child).

Keep it gentle. Always choose a shampoo that won’t irritate skin or eyes (most baby and toddler shampoos are gentle, but sensitivities vary from child to child).

Keep it fun. To minimize the struggles, maximize the fun. Choose foaming shampoo with appealing natural aromas (always offer a sniff) or a brand with favorite characters on the bottle to keep your tot diverted.

Keep it fun. To minimize the struggles, maximize the fun. Choose foaming shampoo with appealing natural aromas (always offer a sniff) or a brand with favorite characters on the bottle to keep your tot diverted.

Stay tangle-free. There’ll be less tangling if you “pat” the shampoo through the wet hair gently, rather than fiercely working up a lather. Working out tangles before you hit the bath will also facilitate a smoother post-shampoo comb-out.

Stay tangle-free. There’ll be less tangling if you “pat” the shampoo through the wet hair gently, rather than fiercely working up a lather. Working out tangles before you hit the bath will also facilitate a smoother post-shampoo comb-out.

Keep those eyes covered. Even a “no-tears” shampoo (even plain water, for that matter) can produce tears if it gets into your toddler’s eyes. Protect his peepers by having him hold a washcloth across his forehead to protect his eyes. Or use a shampoo visor or child-size swimming goggles to keep his eyes dry.

Keep those eyes covered. Even a “no-tears” shampoo (even plain water, for that matter) can produce tears if it gets into your toddler’s eyes. Protect his peepers by having him hold a washcloth across his forehead to protect his eyes. Or use a shampoo visor or child-size swimming goggles to keep his eyes dry.

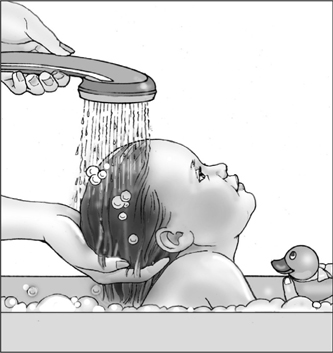

Control the rinse. A handheld spray nozzle offers more control, and less risk of a misdirection mishap. If you don’t have one, use a child’s plastic watering can or cup. After shampooing, your toddler can play with it in the tub.

Control the rinse. A handheld spray nozzle offers more control, and less risk of a misdirection mishap. If you don’t have one, use a child’s plastic watering can or cup. After shampooing, your toddler can play with it in the tub.

Give him a turn. Your toddler may feel less victimized if he’s allowed to shampoo a waterproof doll or other water-friendly toy.

Give him a turn. Your toddler may feel less victimized if he’s allowed to shampoo a waterproof doll or other water-friendly toy.

Let him watch. Mount an unbreakable mirror in the tub so shampooing can become a spectator sport. Making “suds sculptures” with your toddler’s hair can also be diverting.

Let him watch. Mount an unbreakable mirror in the tub so shampooing can become a spectator sport. Making “suds sculptures” with your toddler’s hair can also be diverting.

When rinsing out shampoo, lean your toddler’s head back so the soap deostn’ get into his or her eyes.

From the moment they pop open in the all-too-early morning until the moment they finally, reluctantly, close at night, your toddler’s eyes are busy soaking up-and learning about-the world around him or her. To protect your little one’s precious peepers for a lifetime of sight, start now with:

Regular checkups. It’s important to catch vision or eye problems early, so be sure your toddler’s eyes are checked at all regular checkups, and call between checkups if you have any vision or eye concerns at all (Do his eyes appear crossed? Does she seem to have a hard time recognizing small objects from across the room?). If the doctor turns up anything out of the ordinary, your little one may be referred to an eye specialist, or ophthalmologist, for evaluation. In general, children who were born prematurely are more vulnerable to vision problems, so they may need more frequent eye exams. Check with the doctor.

Regular checkups. It’s important to catch vision or eye problems early, so be sure your toddler’s eyes are checked at all regular checkups, and call between checkups if you have any vision or eye concerns at all (Do his eyes appear crossed? Does she seem to have a hard time recognizing small objects from across the room?). If the doctor turns up anything out of the ordinary, your little one may be referred to an eye specialist, or ophthalmologist, for evaluation. In general, children who were born prematurely are more vulnerable to vision problems, so they may need more frequent eye exams. Check with the doctor.

Protection from the sun. Even if you’ve applied sunscreen to vulnerable skin, your little one’s still not sun-ready. Those adorable eyes need to be protected from the sun, too. Get your toddler used to wearing a wide-brimmed hat when outdoors in strong midday sun. Sunglasses can also be a good option, and wearing them is a great habit to get into early, though it may be difficult to get your toddler to keep them on (you’ll have a better shot at it if you wear a pair, too-toddlers love to copy their parents). When buying sunglasses, be sure to choose ones with UV-blocking lenses, which block 99 percent of both UVA and UVB light. Unlabeled or toy sunglasses may be cheap, but they’re probably worse than no sunglasses at all, since they can provide a false sense of protection. Keep sunglasses from sliding off during play by attaching them with a specially designed child’s glasses band (see the illustration, page 30).

Protection from the sun. Even if you’ve applied sunscreen to vulnerable skin, your little one’s still not sun-ready. Those adorable eyes need to be protected from the sun, too. Get your toddler used to wearing a wide-brimmed hat when outdoors in strong midday sun. Sunglasses can also be a good option, and wearing them is a great habit to get into early, though it may be difficult to get your toddler to keep them on (you’ll have a better shot at it if you wear a pair, too-toddlers love to copy their parents). When buying sunglasses, be sure to choose ones with UV-blocking lenses, which block 99 percent of both UVA and UVB light. Unlabeled or toy sunglasses may be cheap, but they’re probably worse than no sunglasses at all, since they can provide a false sense of protection. Keep sunglasses from sliding off during play by attaching them with a specially designed child’s glasses band (see the illustration, page 30).

Protection from injury. Sure, your toddler’s always prone to bumps and bruises-but eyes can also be injured at play. Never allow your child to play with toys that have sharp points or rods, with sticks, or with pencils and pens, except under close supervision (never allow these items in a moving car); cushion sharp corners on furniture (especially tables that are eye-level for your toddler); teach your toddler never to run with toys in hand; keep all toxic substances (such as cleaning supplies, dishwasher detergent, and lawn care products, many of which can cause eye damage on contact) out of your toddler’s reach; and keep your child away when the lawn is being mowed or snow or leaves are being blown.

Protection from injury. Sure, your toddler’s always prone to bumps and bruises-but eyes can also be injured at play. Never allow your child to play with toys that have sharp points or rods, with sticks, or with pencils and pens, except under close supervision (never allow these items in a moving car); cushion sharp corners on furniture (especially tables that are eye-level for your toddler); teach your toddler never to run with toys in hand; keep all toxic substances (such as cleaning supplies, dishwasher detergent, and lawn care products, many of which can cause eye damage on contact) out of your toddler’s reach; and keep your child away when the lawn is being mowed or snow or leaves are being blown.

Protection from television. While (contrary to your mother’s warnings) no amount of TV watching will actually damage a child’s eyes, prolonged viewing can cause temporary eye-strain. If you let your toddler watch TV, keep the viewing to no more than 30 minutes a day to minimize the strain on those beautiful little eyes. For more reasons to skip TV entirely or limit viewing to a lot less than those 30 minutes, see page 281.

Protection from television. While (contrary to your mother’s warnings) no amount of TV watching will actually damage a child’s eyes, prolonged viewing can cause temporary eye-strain. If you let your toddler watch TV, keep the viewing to no more than 30 minutes a day to minimize the strain on those beautiful little eyes. For more reasons to skip TV entirely or limit viewing to a lot less than those 30 minutes, see page 281.

For information on eye injuries and infections, see page 448.

“My toddler has been blinking a lot lately. She doesn’t seem to be in any discomfort, but should I have her eyes checked out?”

Most toddlers go through a brief blinking phase at some point. Often, it starts when a tot notices that opening and shutting her eyes quickly makes for an interesting visual perspective. Sometimes, it’s a copycat behavior—picked up (like so many other habits) from siblings or day care peers. Either way, when it’s not accompanied by other symptoms, blinking is nothing to worry about—generally, the behavior runs its course within a month or two, as it loses its fascination. Nagging or otherwise calling attention to your little one’s blinking will only give it longer-lasting appeal.

If the blinking is virtually nonstop or seems to bother your child, or if she’s blinking and doing a lot of eye rubbing that’s not related to sleepiness, check with the doctor. Occasionally, blinking is a sign of a tic. These repetitive muscle twitches are common in children, generally benign, but worth mentioning at the next checkup. If you think your toddler is blinking because there’s something wrong with her eye, see the box on the facing page.

Like eye color and shape, vision problems are also often passed down from Mom and Dad—so if you wear glasses or contacts, you’ll want to watch your toddler even more closely for signs that he or she isn’t seeing clearly (see facing page for symptoms to look out for). While abnormal sight is often difficult to spot in a toddler (who not only can’t complain about having a vision problem, but has no way of knowing it’s a problem in the first place), early diagnosis and treatment can keep a condition from getting worse. Here are the vision problems that occur most commonly among toddlers:

Nearsightedness (myopia). More common in children who have a nearsighted parent or parents, myopia is the inability to see objects clearly when they’re more than a short distance away. Though some children become nearsighted in the second or third year of life, the condition more often develops later. Signs and symptoms include squinting, holding books and other objects very close, and having difficulty identifying distant objects. If your child is nearsighted, he or she will need glasses (see page 29).

Cross-eyes: When one eye (or both) wanders inward. You may only notice this in photos.

Farsightedness (hyperopia). All babies and young children tend to be somewhat farsighted (unable to see objects clearly when they’re very close), but in most, vision normalizes by age 5. Kids who remain farsighted usually have a family history of the condition. Signs and symptoms are difficult to detect in younger children (since they all have some trouble with up-close vision). Glasses aren’t necessary unless farsightedness is extreme, interfering with play and other activities.

Astigmatism. Astigmatism causes vision that is blurred or wavy (it’s sort of like looking in a fun-house mirror). Children who are either nearsighted or farsighted are the most likely to have astigmatism, which is usually present at birth. Like nearsightedness, the signs and symptoms of astigmatism are squinting, holding books and objects close to the face, and sitting close to the TV. Glasses can usually correct astigmatism.

Walleyes: When one eye (or both) wanders outward.

Cross-eyes (strabismus). Strabismus is when the eyes can’t focus in unison, and it’s more common in children with a family history of the condition and in those who are farsighted. Infants often appear cross-eyed for the first few months of life for a variety of reasons (including that cute newborn puffiness), and sometimes their eyes seem not to work as a coordinated pair. But by the middle of the first year, the eyes should be able to move right and left and up and down in tandem, and focus together all of the time. In about 4 percent of children, however, the lack of eye coordination persists. The wandering eye (or eyes) may drift inward toward the nose (cross-eye), or outward (walleye), or up or down—some of the time or all the time. The condition may be subtle, and in some cases it’s only noticeable in photos. If your toddler rubs or covers one eye frequently, tilts his or her head to try to coordinate vision, or is reluctant to play games that require judging distances (such as catching a rolling ball), mention it to the doctor. Treatment may include medicated eye drops to blur vision in the stronger eye or placing a patch over it (for short periods each day) to force the use of the weaker one, glasses to equalize vision, and sometimes, exercises to strengthen the eye muscles.

Lazy eye (amblyopia). Lazy eye is when vision is lost in one eye because it’s being chronically underused (or not used). The condition is the most common cause of vision loss in children and can go unnoticed by both child and parent. It can happen in one of three ways:

Cross-eyes (strabismus). In this case, a toddler’s eyes don’t move or focus in unison because of a slight muscle imbalance. To avoid seeing double, he or she subconsciously opts to use only one eye. The brain eventually loses the ability to recognize images sent from the unused (or seldom used) eye.

Cross-eyes (strabismus). In this case, a toddler’s eyes don’t move or focus in unison because of a slight muscle imbalance. To avoid seeing double, he or she subconsciously opts to use only one eye. The brain eventually loses the ability to recognize images sent from the unused (or seldom used) eye.

Farsightedness (or astigmatism) in one eye. The toddler uses only the eye with the clearer picture. The brain eventually stops accepting signals from the unused eye.

Farsightedness (or astigmatism) in one eye. The toddler uses only the eye with the clearer picture. The brain eventually stops accepting signals from the unused eye.

A condition that blocks vision (such as ptosis; see below), if it just affects one eye.

A condition that blocks vision (such as ptosis; see below), if it just affects one eye.

At this age, lazy eye—no matter what’s triggering it—is nearly always correctable, usually with an eye patch, eye drops, and/or glasses. By the time a child has reached school age, however, it may be too late to correct the condition, because the brain has already decided that it isn’t ever going to pay attention to the images produced by the affected eye. That’s why it’s so important to get a vision screening for your toddler if you even suspect lazy eye or another vision problem.

Droopy eyelids (ptosis). Some children are born with ptosis (which is often inherited), while others develop it later. Signs and symptoms include an enlarged, heavy, or drooping eyelid, though occasionally both eyelids are affected. In some cases, the lid totally covers the eye, inhibiting vision, or it distorts the cornea, causing astigmatism. Ptosis requires evaluation and treatment by an ophthalmologist to prevent the development of lazy eye (when the child and the child’s brain learn to depend on the eye with the normal lid and ignore the images from the droopy-lidded eye). When the problem is weak eyelid muscles, surgery (usually performed when the child is 3 or 4) can strengthen them and give the lid a normal appearance.

“We just got word that our 20-month-old needs glasses. He’s so active, it’s hard to imagine him wearing them.”

While it might be hard to imagine those baby blues, browns, or greens covered up by glasses—or those glasses staying put on a toddler who never does—corrective lenses will make a remarkable difference in how your little one sees the world, and can have a major impact on all developmental fronts. And the logistics aren’t as tricky as you might think, either. In fact, getting used to glasses as a 1-year-old is generally easier than acclimating to them later.

Given your toddler’s on-the-go, likely collision-prone lifestyle, you’re best off with lenses made of regular plastic or of polycarbonate (a lightweight, strong, and shatterproof plastic, which reduces the risk of accidental eye injury). When selecting glasses, consider, too, how they’ll stay in place. For infants and young tots, elastic straps are usually substituted for the earpieces. They hold the glasses in place and will allow your little one to lie on his side, roll around, and otherwise act his age without knocking the glasses off. Another age-appropriate option is comfort cables (also called cable temples), which secure glasses with earpieces that curl around the ears rather than pressing against the head (see illustration on the following page). Flexible hinges are also a good idea, since they tolerate more abuse (which they’ll get).

Be patient but persistent while your toddler adjusts to wearing glasses. If the glasses are whipped right off, try again a little later. But don’t allow too much wiggle room. Your toddler needs to understand that wearing the glasses isn’t optional or negotiable. And while it’s likely to be several years before you’ll be able to count on him to care responsibly for his glasses, it’s never too early to begin the training process. Teach your toddler how to take off the glasses with two hands, without touching the lenses, and show him how they should stay in their case when they’re not being worn.

On infants and young toddlers, glasses are generally kept in place by an elastic strap (left) that subs for the ear pieces. Some toddlers do well with comfort cables, which curve around the ears (right).

They come in all shapes and sizes (though they’re uniformly cute)—and like that pair of peepers, your toddler’s two standard-issue ears must last a lifetime. Though genetics and other factors can also play a part, how well those ears will function over that lifetime depends a lot on the care they get in the early years of life. To keep your toddler’s ears in the best working order possible:

Be alert to signs of hearing loss (see box, facing page) and report any concerns to your child’s doctor. It’s likely your toddler was tested for hearing issues as a newborn, but many problems aren’t present at birth—they develop over time. That’s why a parent’s observations are extremely important, too, and can often detect an as yet undiagnosed hearing deficit. Formal hearing tests at the doctor’s office usually begin at age 4 (unless a hearing problem is suspected earlier).

Be alert to signs of hearing loss (see box, facing page) and report any concerns to your child’s doctor. It’s likely your toddler was tested for hearing issues as a newborn, but many problems aren’t present at birth—they develop over time. That’s why a parent’s observations are extremely important, too, and can often detect an as yet undiagnosed hearing deficit. Formal hearing tests at the doctor’s office usually begin at age 4 (unless a hearing problem is suspected earlier).

At bath time, clean the outside crevices of your toddler’s ears with a damp, soft cloth or cotton swab, and check ears carefully for foreign objects (toddlers are known to stick items into their ears). Do not probe the inside of the ear with a finger, a cotton swab, or—as the expression goes—anything smaller than your elbow. Probing, even in the name of cleaner ears, could puncture the eardrum and/or push wax farther into the ear (where it can encourage infection or interfere with hearing).

At bath time, clean the outside crevices of your toddler’s ears with a damp, soft cloth or cotton swab, and check ears carefully for foreign objects (toddlers are known to stick items into their ears). Do not probe the inside of the ear with a finger, a cotton swab, or—as the expression goes—anything smaller than your elbow. Probing, even in the name of cleaner ears, could puncture the eardrum and/or push wax farther into the ear (where it can encourage infection or interfere with hearing).

Wax, though icky to look at, isn’t usually something that needs removing. Secreted by glands in the ears, that gooey gunk actually serves an important purpose—helping to protect the sensitive ear canals by trapping potentially harmful dirt and debris that would otherwise find its way in, then working its way out, taking that trash with it. It is possible, however, to have too much of this good thing—excessive amounts of earwax can occasionally build up in the ear canal. If you’re concerned about a waxy buildup that you’ve noticed in your toddler’s ears, check with the doctor, who may remove it, recommend drops to help loosen it up, or suggest you ignore it. Never try to remove wax yourself, even with a cotton swab. Not only could you push the goo up farther into the ear canal, but there’s a very real risk of puncturing your toddler’s eardrum (yes, with a cotton swab). As for wax that’s hanging around the outer ear, wipe it away gently with a wet washcloth.

Wax, though icky to look at, isn’t usually something that needs removing. Secreted by glands in the ears, that gooey gunk actually serves an important purpose—helping to protect the sensitive ear canals by trapping potentially harmful dirt and debris that would otherwise find its way in, then working its way out, taking that trash with it. It is possible, however, to have too much of this good thing—excessive amounts of earwax can occasionally build up in the ear canal. If you’re concerned about a waxy buildup that you’ve noticed in your toddler’s ears, check with the doctor, who may remove it, recommend drops to help loosen it up, or suggest you ignore it. Never try to remove wax yourself, even with a cotton swab. Not only could you push the goo up farther into the ear canal, but there’s a very real risk of puncturing your toddler’s eardrum (yes, with a cotton swab). As for wax that’s hanging around the outer ear, wipe it away gently with a wet washcloth.

If you suspect an ear infection (see page 382), check with the doctor.

If you suspect an ear infection (see page 382), check with the doctor.

“I’d like to pierce my daughter’s ears. Is she too young?”

Technically, a girl’s never too young—or too old—to join the pierced ear club. Still, whether you’re eager to pierce for cultural or family tradition reasons, for the fashion statement, or for the gender announcement (as in, “I’m a girl, people!”), there are some issues to consider before letting the piercing gun near your little one’s lobes:

The possibility of infection. Infections are common in the first few months after a piercing (for people of any age), and because your toddler probably won’t have the words to tell you that her ear is itchy, sore, or tender, an infection can get out of hand pretty quickly—and before you’re even aware of it.

The possibility of infection. Infections are common in the first few months after a piercing (for people of any age), and because your toddler probably won’t have the words to tell you that her ear is itchy, sore, or tender, an infection can get out of hand pretty quickly—and before you’re even aware of it.

The danger of small parts. Your toddler could manage to take off her earrings to play with (look at this neat toy!), or they could accidentally fall off and wind up in her hands. The potential problem? She could stick herself with a stud or swallow (or choke on) one or more of the parts.

The danger of small parts. Your toddler could manage to take off her earrings to play with (look at this neat toy!), or they could accidentally fall off and wind up in her hands. The potential problem? She could stick herself with a stud or swallow (or choke on) one or more of the parts.

The possibility of allergy. Some people are allergic to the metals in earrings, though it’s often possible to avoid this problem by using only 14k gold or surgical steel earrings and posts.

The possibility of allergy. Some people are allergic to the metals in earrings, though it’s often possible to avoid this problem by using only 14k gold or surgical steel earrings and posts.

In some toddlers, scarring. If your little one tends to get lumpy scars (a.k.a. keloids), she may be prone to them after piercing, too.

In some toddlers, scarring. If your little one tends to get lumpy scars (a.k.a. keloids), she may be prone to them after piercing, too.

For these reasons, most doctors recommend holding off on piercing until a child is at least 4, and preferably closer to 8 years old (about the age she can take care of her pierced ears herself). Still, it’s a perfectly safe procedure for young children—as long as it’s done under sterile conditions by someone who is qualified (your daughter’s doctor may be able to pierce them in the office) and—here’s the biggie—if you can get your toddler to sit still long enough to get them done. Keep in mind, too, that piercing hurts (remember that day at the mall?).

If you choose to pierce now, be extra careful to follow the normal post-piercing protocol: Clean her lobes daily by dabbing them with a cotton ball saturated with rubbing alcohol or the solution given to you by the piercing place and rotate the earrings each morning and evening (to keep them from sticking to the holes), using clean fingers. If you notice any signs of infection (redness, swelling, pus or crusting, tenderness, or bleeding) call your child’s doctor.

One last caveat: Save dangling and hoop earrings until your tot is grown up—they can be pulled by other children (or by your child herself), possibly tearing the earlobe. If your little one starts trying to remove her earrings or play with them, stop inserting the earrings and let the holes close up. You can always have her ears repierced when she’s a little older and more responsible.

The second year is a busy, busy time in a child’s mouth. By the time they turn 2- to 2½-years old, most tots will sport a full set of 20 primary teeth. Though these baby teeth aren’t for keeps, they’ll take your child through the next 5 to 10 years—in fact, the last of them won’t be replaced by permanent teeth until somewhere between ages 12 and 13. And since each tooth is vulnerable to decay from the moment it breaks through the gum (in fact, decay is most common in the first 6 months after a tooth erupts), it’s definitely important to make good dental hygiene a priority early on.

So, if you haven’t already done so, get your toddler into the habit of brushing—and being brushed—regularly each morning (after breakfast) and evening (after any bedtime snack). Here’s how:

Select a toothbrush designed for young children, with a small head and soft, rounded bristles. To make tooth-brushing more palatable for your tot, choose a brush that’s decorated with favorite characters or with lights that flash and/or music that plays for 2 minutes (the recommended amount of time to spend brushing). Keep in mind, however, that bells, whistles, and a hefty price tag don’t make a toothbrush inherently more effective. The secret to a thorough tooth cleaning is in the brushing technique, not the brush.

Select a toothbrush designed for young children, with a small head and soft, rounded bristles. To make tooth-brushing more palatable for your tot, choose a brush that’s decorated with favorite characters or with lights that flash and/or music that plays for 2 minutes (the recommended amount of time to spend brushing). Keep in mind, however, that bells, whistles, and a hefty price tag don’t make a toothbrush inherently more effective. The secret to a thorough tooth cleaning is in the brushing technique, not the brush.

Be the designated brusher. Until your child is up to the challenge of thorough brushing (which can happen anytime between ages 5 and 10, depending on the child), you’ll be in charge of brushing. Working one tooth at a time, use a gentle back and forth motion across the chewing and inner surfaces (finish one side first before going on to the other so you don’t lose track). Switch to a circular motion along the sides and the outer gum lines (with the brush at a 45-degree angle). Lightly brush the gums where teeth haven’t yet erupted, or wipe them with a gauze pad, baby finger brush, or washcloth, and also do a gentle once-over on the tongue (where a lot of bacteria can hang out). If your toddler resists brushing altogether or your help with brushing (and most will), see the next question.

Be the designated brusher. Until your child is up to the challenge of thorough brushing (which can happen anytime between ages 5 and 10, depending on the child), you’ll be in charge of brushing. Working one tooth at a time, use a gentle back and forth motion across the chewing and inner surfaces (finish one side first before going on to the other so you don’t lose track). Switch to a circular motion along the sides and the outer gum lines (with the brush at a 45-degree angle). Lightly brush the gums where teeth haven’t yet erupted, or wipe them with a gauze pad, baby finger brush, or washcloth, and also do a gentle once-over on the tongue (where a lot of bacteria can hang out). If your toddler resists brushing altogether or your help with brushing (and most will), see the next question.

Start teaching your little one how to rinse after brushing (most toddlers master the rinse and spit around age 2). As always, it’s easiest to teach through example: Show him or her how you lean over the sink and say “ptooey.” Rinsing is important not only because it removes the toothpaste before it’s swallowed, but it also eliminates bits of loosened food that would otherwise resettle on the teeth.

Start teaching your little one how to rinse after brushing (most toddlers master the rinse and spit around age 2). As always, it’s easiest to teach through example: Show him or her how you lean over the sink and say “ptooey.” Rinsing is important not only because it removes the toothpaste before it’s swallowed, but it also eliminates bits of loosened food that would otherwise resettle on the teeth.

Consider skipping the toothpaste until your toddler can be relied on to rinse and spit. Though it can definitely make brushing more appealing (a major plus, for sure), it doesn’t necessarily make it more effective. If you use toothpaste earlier on, choose an infant/toddler formula that’s fluoride-free to avoid ingesting too much fluoride (overdosing can lead to teeth that are permanently stained). Once rinsing and spitting are mastered, you can begin to put a pea-size or smaller amount of fluoridated toothpaste on the brush, but watch out for toothpaste eaters. Some kids will gobble the stuff when you’re not looking.

Consider skipping the toothpaste until your toddler can be relied on to rinse and spit. Though it can definitely make brushing more appealing (a major plus, for sure), it doesn’t necessarily make it more effective. If you use toothpaste earlier on, choose an infant/toddler formula that’s fluoride-free to avoid ingesting too much fluoride (overdosing can lead to teeth that are permanently stained). Once rinsing and spitting are mastered, you can begin to put a pea-size or smaller amount of fluoridated toothpaste on the brush, but watch out for toothpaste eaters. Some kids will gobble the stuff when you’re not looking.

Once any two teeth have grown in side by side—even if they’re not exactly touching—it’s time to start flossing. Yes, really, flossing. Flossing is as essential to good dental health as brushing and rinsing—and a really important habit for your tot to get into. Once again, you’ll be on floss duty until your child’s much older, at least 7 or 8. Which is easier said than done, both because it’s difficult to maneuver large adult hands around such a tiny toddler mouth, and because most tots will not sit long enough to be fully flossed. Realistically, unless you have an unusually cooperative toddler, you probably won’t get through the entire mouth every day, and that’s okay—it’s more about getting into the habit than it is about getting the job done. Focus first on molars—if there are any—and work your way back to front. Gently does it.

Once any two teeth have grown in side by side—even if they’re not exactly touching—it’s time to start flossing. Yes, really, flossing. Flossing is as essential to good dental health as brushing and rinsing—and a really important habit for your tot to get into. Once again, you’ll be on floss duty until your child’s much older, at least 7 or 8. Which is easier said than done, both because it’s difficult to maneuver large adult hands around such a tiny toddler mouth, and because most tots will not sit long enough to be fully flossed. Realistically, unless you have an unusually cooperative toddler, you probably won’t get through the entire mouth every day, and that’s okay—it’s more about getting into the habit than it is about getting the job done. Focus first on molars—if there are any—and work your way back to front. Gently does it.

Won’t be near a toothbrush for a while and your little one’s just eaten a cookie or another sugary treat? A quick swipe with a xylitol toothwipe (available at drugstores and online, and easily stashed in your bag) can remove plaque from your toddler’s teeth while safely fighting cavity-causing bacteria.

Won’t be near a toothbrush for a while and your little one’s just eaten a cookie or another sugary treat? A quick swipe with a xylitol toothwipe (available at drugstores and online, and easily stashed in your bag) can remove plaque from your toddler’s teeth while safely fighting cavity-causing bacteria.

Don’t forget to explain. No, toddlers aren’t always motivated by messaging, but it’s good to build the benefits of good oral hygiene into the conversation anyway. When you’re brushing and flossing, remind him or her that keeping those teeth clean helps them stay strong and healthy, so they won’t get “boo-boos.” Also point out that strong teeth will let him or her eat yummy food. When your little one drinks milk or eats cheese or yogurt, reinforce: “Healthy foods make your teeth healthy, too!”

Don’t forget to explain. No, toddlers aren’t always motivated by messaging, but it’s good to build the benefits of good oral hygiene into the conversation anyway. When you’re brushing and flossing, remind him or her that keeping those teeth clean helps them stay strong and healthy, so they won’t get “boo-boos.” Also point out that strong teeth will let him or her eat yummy food. When your little one drinks milk or eats cheese or yogurt, reinforce: “Healthy foods make your teeth healthy, too!”

“My toddler clamps his mouth shut when I try to brush his teeth. I’m tempted to give up trying.”

The tussle of the toothbrush is just another skirmish in your toddler’s stubborn struggle for autonomy—in this case, autonomy over his mouth (which, he’s discovered, is a cinch to control). Since surrender on his side is unlikely, and surrender on yours isn’t smart—after all, even baby teeth need to be protected from cavities—a little creative compromise is called for:

Brush in style. Let your toddler choose two or three colorful child-size toothbrushes at the store (be sure the bristles are soft and of good quality). Then let him select the one he wants to use at brushing time. This helps defuse the control issue (even though he can’t decide whether or not to brush, he can decide what to brush with) and may distract him enough so that he’ll forget to protest.

Approaching your tot from behind and tilting his or her head back slightly may give you the best visibility and maneuverability for toothbrushing. Or you can sit on the floor, seat your child in your lap, and have him or her lean back against you.

Strike the right position. It’ll be easier to maneuver around your toddler’s mouth if you’re positioned right. Cradle his head in one arm while you brush with the other, or for even more control (and a better view of what you’re doing), have him lie on the floor with his head in your lap. Or sit on the floor with him on your lap, his head leaned against you (see illustration on the previous page).

Let him do it himself. Though you’re the brushing boss, you’ll get more cooperation if you double-team. First, give your toddler his own brush to do some preliminary brushing. Or, if you find he cooperates better with the promise of a reward ahead, reverse the order: you start, he finishes. Don’t worry about his technique or the condition of his toothbrush (the bristles will soon become flattened and misshapen from being chewed on)—just let him get the job done the best way he knows how. Praise his efforts, even if the toothbrush doesn’t really make its mark. As he becomes a more skilled (and thorough) brusher, you may be able to let him take over the morning brushing completely, while you continue to help out at bedtime. But don’t expect really proficient, independent brushing for many years to come.

Letting your toddler “brush the teeth” of a stuffed animal or doll (using a toothbrush reserved for play) or even brush yours may make him more amenable to having the brush wielded on him.

Then do it yourself. After you’ve told your toddler what a great job he’s done on his teeth, take your turn—using a different brush. Letting him hold the toothbrush along with you will let him maintain some control over the process, as will giving him a complete brush-by-brush as you go (“These two teeth look nice and clean, let’s try the next two”). Injecting a little levity may also loosen your toddler up a bit. Pretend to go for the wrong body part: “It’s time to brush your tummy!” Or try the old favorite: “I see a giraffe (or an elephant, or a turtle) in there—let’s see if I can get it out with the toothbrush.”

Check each other. When the brushing’s done, it’s time to check your work and his. Challenge him to open his mouth as wide as he can so you can inspect his teeth for lingering bits of food (an older toddler may enjoy checking his teeth in the mirror, too). You can also have him check after you’ve brushed your own teeth, or after other family members have brushed theirs. Dub him the official tooth checker.

“Our 15-month-old seems to be getting molars now. He’s a lot more miserable with them than he was with his other teeth.”

He’s miserable for good reason. Because of their large size and double edge, first molars (which usually make their appearance sometime between 13 and 19 months) are at least twice as hard to cut as incisors—and for many children that means at least twice as much ouch.

To soothe your toddler’s pain, turn to some of the same standbys that helped him through earlier teething episodes, like rubbing his gums with a clean finger or letting him chomp on a refrigerator-chilled teething ring. Chilled applesauce or frozen banana may also soothe those sore gums, as may a cup of icy cold water (don’t leave ice in it, though). Other old teething relief favorites should be shelved now that your tot has teeth (a chilled carrot, for instance, because he’s capable of biting off a chokable chunk, or teething biscuits, because their high carbohydrate content could lead to tooth decay if they’re mouthed all day long). A topical teething soother (like Orajel) can numb gums briefly (usually for about a half hour), but probably shouldn’t be applied more than four times a day—which means it won’t provide around-the-clock relief. Your child’s doctor might also recommend ibuprofen or acetaminophen when the pain is at its worst, probably at bedtime, and especially if teething pain interferes with your little one’s eating and sleeping.

Speaking of sleeping, often a toddler who’s cutting molars may start waking during the night (or may wake up more frequently). While you’ll want to provide comfort, keep in mind that this kind of waking can become chronic—continuing long after the pain has left the building—so try to minimize those midnight comfort runs.

While teething can definitely trigger crankiness, lack of appetite, even a slightly elevated temperature, report any symptoms of illness that warrant a call to the doctor. They could be completely unrelated to teething and may need treatment.

“I’m guessing our daughter is going to need braces because there is so much space between her teeth.”

Often, the front primary teeth debut with big gaps between them—and that could actually be a good thing as far as a perfect smile is concerned. That’s because the front adult teeth are bigger than baby teeth, and they’ll need the extra space when they eventually move in. Those primary front teeth are also apt to shift closer together as adjacent baby teeth erupt, pushing their way into place. The comforting bottom (and top) line: There’s no direct correlation between irregularly spaced baby teeth and a smile that needs fixing later.

“Do I need to take my 1-year-old to a dentist? I can’t imagine he’ll ever sit still in the chair.”

Your toddler definitely doesn’t need a full set of chompers to qualify for the dentist’s chair. In fact, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) recommends a first dental checkup by the age of 1, and sooner if you suspect there’s a cavity or another problem. But while getting off to an early start with dental care is always a smart idea, realistically, that first checkup may not take place at a dentist’s office. First, because not all dentists—even pediatric dentists—will see 1-year-olds (you may have a hard time locating one in your area who does). Second, while all 1-year-olds need their baby teeth checked, not every 1-year-old needs the specialized care of a dentist just yet. No sign of cavities or other problems? No pressing need to book that first dentist’s appointment. The pediatrician can also perform basic dental exams and is probably already doing this at regular well-child appointments—checking for problems that require a referral to a dentist, and counseling you about keeping your little one’s teeth healthy.

Why is it so important that a dentist or doctor is on tap for tooth duty this early on? Besides getting your toddler into the dental hygiene habit early, professional attention to those tiny teeth can prevent or identify decay (which could lead to premature loss of baby teeth) and diagnose mouth irregularities that may interfere with speech development. The dentist or doctor can also be an excellent backup authority when it comes to convincing your toddler to cooperate with brushing, or to give up the bottle, thumb, or pacifier. Plus, either one can answer the questions you may have on teething, brushing and flossing (you can even ask for a demo), fluoride intake, and all those sucking habits.

Opting out of the dentist for now? Definitely make sure your toddler sees a dentist by his third birthday, if not before (the sooner the going-to-the-dentist habit is established, the better). Most first visits are basic—more like an introductory icebreaker than a full-fledged dental visit. The dentist will count your little one’s pearly whites, examine his jaw, bite, and gums, and do a gentle tooth cleaning.

See the box on the previous page for tips on preparing your toddler for the dentist.

Keeping a baby’s skin baby soft and protected is child’s play (a little after-bath lotion and judicious care in the diaper area and an infant is cuddle-ready). Keeping a toddler’s skin soft and protected, however, can be, well, a little rougher. Toddlers are constantly on the go, indoors and out (meaning more exposure to skin-chafing elements) and they have a knack for getting dirty (both dirt and dirt cleaning can irritate tender skin), giving their skin a tough time. And because the sebaceous glands, which will eventually lubricate and protect the skin, don’t kick in until the hormones start flowing just before puberty, young skin is especially prone to dryness and irritation. To keep your toddler’s skin clean but as soft and touchable as a baby’s, treat it with care. Look for very gentle soaps or cleansers that promise not to irritate your little one’s sensitive skin (hands off your body wash, bubble bath, or soap bars unless they’re super mild). Also avoid antibacterial soaps because they can be unnecessarily irritating (and also aren’t necessary). Use even the gentlest of soaps sparingly, soaping up only as needed (where dirt is most obvious, and around the diaper area). And when it comes to toddler skin care, less is more. There’s no need to smooth on lotions or creams (unless your little one has very dry skin; see page 44).

“My son has always loved his bath, and he isn’t afraid of water at all. So I can’t understand why he’s suddenly refusing to get into the tub.”

As you’ve probably already noticed, refusals of every kind are big in the second year. A toddler may refuse to eat, refuse to wear a coat, refuse to go outside, refuse to come back in—simply for refusal’s sake, without apparent rhyme or reason. The truth is, however, there is a reason—a very good one: his struggle for independence. Here’s how to get your toddler back in the tub—or, at least, help you find other ways to clean up his act:

Bring on the toys. Like the fleet of plastic boats. And the funnels and cups. And the bath books. And colorful soaps. And any other waterproof diversion you can come up with. Let the toys and fun—and not the washing—be the focus of the tub experience. Instead of announcing bath time with, “Time to get in the tub,” announce it with, “Look at all these boats you can play with!” or “Let’s paint tiger stripes on you with this funny soap!”

Schedule a change. If bath time comes at an unexpected hour, rather than at the accustomed battle time, it’s possible that your toddler’s surprise may ease his opposition. Admittedly, a change in schedule may mean that your child won’t be getting clean when he’s his dirtiest (if bath has been switched to mid-morning instead of after dinner, for instance), but in the short run that’s better than not getting clean at all. Until he becomes more amenable to bathing, and bath time can return to a more sensible time slot, a quick session with a washcloth on the more glaringly grimy areas can get him passably clean before he gets into his pajamas.

Try a little togetherness. The rub-a-dub-dub may be more appealing if there’s more than one in the tub. Mommy or daddy make perfect tub buddies (don a bathing suit if you’d rather not bathe in the buff with your toddler). An older sibling or a friend on a playdate makes an ideal bath mate, too (prior parental permission suggested). Or try a washable doll—he can wash his baby while you wash yours.

Hit the showers. If it’s the tub that’s triggering the rebellion, let your toddler accompany you in the shower instead. Adjusting the water-flow rate to gentle will help make the overhead stream less threatening, as may holding your toddler until he feels confident enough to stand under the shower on his own. A rousing round of “It’s raining, it’s pouring” can provide a playful note. As with tub water, shower water should be warm, rather than hot, for toddlers.

Keep it short and sweet. Since you’re still the one in charge, and because your toddler will need to get clean every once in a while (whether he likes it or not), you may just have to pull rank. A quick in and out of the tub or a fast sponge bath may still prompt protests from your bath balker, but if you keep it short and sweet, and move on to another diversion as soon as the deed is done, you’ll end up with a clean toddler no worse for the wear. Keep your cool, too (no taking the bait when your little fish puts up a fight). And remember—this too shall pass.

“Our toddler’s hands get unbelievably dirty during a morning of play. But she won’t let us wash them before she eats.”

No matter what the season, it’s what all the toddlers are wearing: blackened knees, filthy forearms, grimy elbows, sticky faces, and dirt-encrusted fingernails.

But though most of the dirt a toddler attracts during a morning’s play can stay put until her nighttime tubbing, the dirt on her hands should be removed before she eats—particularly since she’ll be using them to feed herself. Making sure her hands are scrubbed before every meal won’t only keep dirt out of her food (and her mouth)—it’ll get her in the healthy, hygienic hand-washing habit.

Easier said than done? Not if you arm yourself with these hand-washing tips:

Put hand washing in her hands. The more control toddlers have over an activity, the less likely they are to resist it. Turn the soap and water over to her, and much of her resistance may go down the drain with the dirt. Don’t make a fuss about the splashy mess she’ll inevitably make—it can be mopped up afterward. Do adjust the water temperature for her, though, to avoid burns. (As a safety precaution, keep your home water heater set below 120°F.) Check her handiwork when she’s finished—if her hands don’t look much cleaner than when she started, have her try again. Or let her wash your hands while you wash hers.

Make hand washing fun. Because a two-second hand wash won’t do the trick (in terms of both dirt and germs), your tot will need a solid 20 seconds of rub-a-dub-dubbing to get clean. Sounds like an eternity (to a toddler)—unless you also make it fun. Sing “Happy Birthday” or the ABC song twice through while washing up, use a kid’s foaming or colorful soap to keep things interesting, or go for naturally scented—coconut or lavender, for instance—to keep things sweet (and don’t forget to ask for a whiff after she’s washed up).

Put hand washing within her reach. One of the most frustrating parts of hand washing for a toddler is the stretch—literally. Providing your toddler with easy access to the bathroom sink (via a steady step stool) and placing accessories (soap and towel) within reach can help her feel more in control of the process.

Switch to liquid soap. Bar soap is not only slippery and difficult for little fingers to lather, but it collects almost as much dirt as your toddler’s hands. So stick with the liquid or foaming kinds of soap.

Wipe it away. When you’re away from home, disposable wipes may be the easiest and most sanitary way of giving hands a quick wash, and even a fairly young toddler can use them. Encourage her to make the wipes as “dirty” as she can, so that more of the grime will come off her.

If you do use antibacterial hand gel when you’re out and about with your toddler (after a trip to the petting zoo, for instance, or after touching the supermarket cart handle), keep in mind that while such gels or rinses do a decent job of sanitizing the hands, they won’t get the dirt off. So use a wipe first to scrub off the grime, and then, if you choose, use a child-safe hand sanitizer (one that’s free of alcohol and strong chemicals).

“My son’s skin always seems so dry. What can I do to protect it?”

Many toddlers go through dry skin spells—and some continue to be a little rough around the edges throughout early childhood. Fortunately, there are ways to replenish the moisture that life-on-the-go can steal from tender skin, softening things up in no time:

Be soap-savvy. If your toddler has very dry, extra-sensitive, or rash-prone skin, choose a cleanser that’s fragrance free or even soapless (like Cetaphil).

Be soap-savvy. If your toddler has very dry, extra-sensitive, or rash-prone skin, choose a cleanser that’s fragrance free or even soapless (like Cetaphil).

Cut back on bath time. Thirty minutes in the tub may seem like a dream for your toddler (so much splashing, so little time!), but too much soaking in water can remove the skin’s natural oils along with the dirt. Limiting baths to 10 minutes will allow enough playtime, without paying the price in dry skin.

Cut back on bath time. Thirty minutes in the tub may seem like a dream for your toddler (so much splashing, so little time!), but too much soaking in water can remove the skin’s natural oils along with the dirt. Limiting baths to 10 minutes will allow enough playtime, without paying the price in dry skin.

Don’t rub-a-dub-dub in (or after) the tub. Be gentle when sudsing up and rinsing your toddler’s skin—no scrubbing with the washcloth. Always pat skin dry instead of rubbing it when your little fish is out of the water.

Don’t rub-a-dub-dub in (or after) the tub. Be gentle when sudsing up and rinsing your toddler’s skin—no scrubbing with the washcloth. Always pat skin dry instead of rubbing it when your little fish is out of the water.

Moisturize. Top off every bath (while your little one’s skin is still slightly moist) with a generous layer of moisturizer. Reapply as needed, especially when the weather’s really cold or your toddler’s skin is really parched. The best moisturizers for a toddler’s skin contain both water (to replenish moisture) and oil (to seal it in). Extra-sensitive or extra-dry skin will be soothed best by a moisturizer that has few chemical additives and is free of fragrances. Eucerin, Aquaphor, Moisturel, Neutrogena, Cetaphil, Aveeno, and Lubriderm are all top pediatrician and dermatologist picks—though keep in mind the only reaction that matters is your child’s skin. Sometimes, even “baby,” “hypoallergenic,” or “all-natural” products can trigger irritation or a rash—which means it’s time to pull a moisturizer switch (choose one with a different formulation).

Moisturize. Top off every bath (while your little one’s skin is still slightly moist) with a generous layer of moisturizer. Reapply as needed, especially when the weather’s really cold or your toddler’s skin is really parched. The best moisturizers for a toddler’s skin contain both water (to replenish moisture) and oil (to seal it in). Extra-sensitive or extra-dry skin will be soothed best by a moisturizer that has few chemical additives and is free of fragrances. Eucerin, Aquaphor, Moisturel, Neutrogena, Cetaphil, Aveeno, and Lubriderm are all top pediatrician and dermatologist picks—though keep in mind the only reaction that matters is your child’s skin. Sometimes, even “baby,” “hypoallergenic,” or “all-natural” products can trigger irritation or a rash—which means it’s time to pull a moisturizer switch (choose one with a different formulation).

Keep those fluids coming. Inadequate fluid intake can lead to dry skin (that moisture comes from the inside out), so make sure your little guy gets his fill. Be especially aware of fluid intake if your toddler has just been weaned and is still working out the kinks of drinking from a cup, if it’s hot out, or if he’s been sick.

Keep those fluids coming. Inadequate fluid intake can lead to dry skin (that moisture comes from the inside out), so make sure your little guy gets his fill. Be especially aware of fluid intake if your toddler has just been weaned and is still working out the kinks of drinking from a cup, if it’s hot out, or if he’s been sick.

Feed healthy fats. Getting enough of the right kinds of fats can lubricate your little one from the inside out, too. Think avocados, canola, flax, and olive oil, almond or cashew butter (if there’s no nut allergy, and spread very thinly). A generally healthy diet also helps promote healthy skin.

Feed healthy fats. Getting enough of the right kinds of fats can lubricate your little one from the inside out, too. Think avocados, canola, flax, and olive oil, almond or cashew butter (if there’s no nut allergy, and spread very thinly). A generally healthy diet also helps promote healthy skin.

Avoid overheating in cold weather. When the mercury dips outside, it’s always tempting to send the mercury rising inside. But dry, overheated air leads to overdry skin, particularly for toddlers. So keep the temperature inside your home comfortable, but not overly warm. Keep your toddler cozy in sweats or sweaters during the day and warm sleepers at night.

Avoid overheating in cold weather. When the mercury dips outside, it’s always tempting to send the mercury rising inside. But dry, overheated air leads to overdry skin, particularly for toddlers. So keep the temperature inside your home comfortable, but not overly warm. Keep your toddler cozy in sweats or sweaters during the day and warm sleepers at night.

“What can I do about my son’s red, chapped cheeks?”

On an average day, a variety of substances (ranging from saliva and mucus to jelly and tomato sauce) manage to find their way onto a toddler’s face, where they’re promptly smeared from cheek to cheek, causing redness and irritation—especially in winter, when skin is already extra dry. Frequent face washings (to remove these substances) often compound the chafing.

If your toddler’s cheeks turn apple red with the first frost and stay that way until the tulips come up, some special attention is needed. To minimize facial chapping:

Gently wipe your child’s face with warm water immediately after meals to remove any traces of food, then pat dry promptly. If you notice that a particular food or beverage is especially irritating to the skin (common offenders are those that are high in acid, such as citrus fruits and juices, strawberries, and tomatoes or tomato sauce), avoid serving it to your toddler until the chafing has cleared.

Gently wipe your child’s face with warm water immediately after meals to remove any traces of food, then pat dry promptly. If you notice that a particular food or beverage is especially irritating to the skin (common offenders are those that are high in acid, such as citrus fruits and juices, strawberries, and tomatoes or tomato sauce), avoid serving it to your toddler until the chafing has cleared.

No rubbing. When washing those chubby cheeks, be extra gentle. And always pat dry. Don’t use scratchy cloths or rough paper towels or napkins.

No rubbing. When washing those chubby cheeks, be extra gentle. And always pat dry. Don’t use scratchy cloths or rough paper towels or napkins.

Avoid using soap on your toddler’s face. When more than water is called for, use a soapless cleanser.

Avoid using soap on your toddler’s face. When more than water is called for, use a soapless cleanser.

Pat his face dry with a soft cloth whenever he’s been drooling (try to catch him before he wipes the drool all over his cheeks). Gently wipe that snotty nose frequently for the same reason.

Pat his face dry with a soft cloth whenever he’s been drooling (try to catch him before he wipes the drool all over his cheeks). Gently wipe that snotty nose frequently for the same reason.

Soothe chapped skin with a mild moisturizer. Spreading moisturizer on cheeks, chin, and nose before going out in cold weather may also be protective, especially for a teething toddler who is drooling a lot or a toddler with a runny nose. For tough cases, you may have to opt for an ointment (like Aquaphor), which acts as a barrier while it moisturizes.

Soothe chapped skin with a mild moisturizer. Spreading moisturizer on cheeks, chin, and nose before going out in cold weather may also be protective, especially for a teething toddler who is drooling a lot or a toddler with a runny nose. For tough cases, you may have to opt for an ointment (like Aquaphor), which acts as a barrier while it moisturizes.

“I noticed a red rash inside my toddler’s elbow, and she’s scratching it a lot. Could it be an allergic reaction to something, like soap—or could it be eczema?”

Actually, it could be both. Eczema is the blanket name that technically covers the two most common skin conditions in children: atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis. While both cause rashes—and either could be triggered by an allergic reaction—atopic dermatitis is often chronic, while contact dermatitis usually comes and goes. Initially, they’re not easy to tell apart (though the doctor may be able to clue you in). Here’s the breakdown on the causes, symptoms, and treatments for both types of eczema:

Atopic dermatitis. When most people (including doctors) talk about “eczema,” this is the condition they’re typically referring to. Most common in children with a history (or family history) of allergies, hay fever, or asthma, eczema has been aptly described as “an itch that rashes.” Once the itch begins, scratching or rubbing the area triggers the rash. In a toddler, the rash usually consists of red small bumps that often weep (or ooze) and crust over when scratched. The rash usually starts on the face and cheeks, spreading to the trunk of the body, the wrists, and body folds (inside groin and elbow creases). This type of eczema is often (though not always) outgrown by age 2 to 3.

What triggers the itch? For most kids, it could be any of the following triggers: dry skin, heat or cold exposure, perspiration, wool and/or synthetic clothing, friction, soaps, detergents, and fabric softeners (though these could trigger contact dermatitis as well; see the next column). Eating certain foods (most often eggs, milk, wheat, peanuts, soy, fish, and shellfish) can also cause a reaction.

Treatment usually includes topical steroid (hydrocortisone) creams or ointments for inflammation and oral antihistamines for itching (especially to help a child sleep). The pediatrician will prescribe or recommend the medication that’s right for your toddler. On the home front, it’s important to:

Clip your toddler’s nails to prevent scratching.

Clip your toddler’s nails to prevent scratching.

Limit baths to no more than 10 to 15 minutes, and use an extra-mild or soapless cleanser (Dove or Cetaphil, for example) only as needed.

Limit baths to no more than 10 to 15 minutes, and use an extra-mild or soapless cleanser (Dove or Cetaphil, for example) only as needed.

Limit dips in chlorinated pools and salt water (fresh water is okay).

Limit dips in chlorinated pools and salt water (fresh water is okay).

Apply plenty of rich hypoallergenic moisturizer after baths, when the skin is damp.

Apply plenty of rich hypoallergenic moisturizer after baths, when the skin is damp.

Minimize exposure to extremes in temperature, indoors and out.

Minimize exposure to extremes in temperature, indoors and out.

Use a humidifier as needed to prevent dry air indoors (but don’t overdo the humidity, since too much moisture in the air promotes the growth of mold and mildew, common allergy and asthma triggers).

Use a humidifier as needed to prevent dry air indoors (but don’t overdo the humidity, since too much moisture in the air promotes the growth of mold and mildew, common allergy and asthma triggers).

Dress your child in cotton (rather than wool or synthetics), and avoid scratchy, potentially irritating clothing.

Dress your child in cotton (rather than wool or synthetics), and avoid scratchy, potentially irritating clothing.

Contact dermatitis. A contact dermatitis rash occurs when skin repeatedly comes in contact with an irritating substance (such as citrus, bubble bath, soaps, detergents, foods, medicines, even a toddler’s own saliva or urine—as with diaper rash). The rash, which appears as mild redness and/or small bumps (sometimes with accompanying swelling), is often more localized than atopic dermatitis and usually clears when the irritant is removed (if it doesn’t, you may have a case of atopic dermatitis on your hands) and the rash is treated with hydrocortisone creams or ointments. The rash can also crop up when skin comes in contact with an allergen (like nickel jewelry or snaps on clothes, dyes in clothes, plants like poison ivy, or some medications).

“Our toddler’s skin seems so rash prone. Just when his diaper rash seems under control, another rash pops up somewhere else. How can I tell one rash from another and what can I do about them?”

Rashes come and go on toddler skin, but in some toddlers, they seem to come more than they go. Most of the time, a dry patch or a crop of elevated bumps on your tot’s skin is nothing more than annoying (especially if it’s ruining your toddler’s close-ups), and sometimes it’s just a reaction to a fragrance or another chemical in a soap or shampoo. But once in a while it’s an indication of a skin condition that needs some attention. If your toddler’s skin is scaly, itchy, blistered, or oozing, check with the doctor to find out what is causing it and how to treat it. The most common skin rashes in toddlers include:

Ringworm (a.k.a. tinea). This mildly contagious fungal infection (don’t worry, no worms are actually involved) shows up as round, red, raised, itchy, and scaly patches that can be as small as a dime or can grow up to an inch or more in diameter. Ringworm can be spread by direct person-to-person contact (one toddler who’s been scratching touches another—and bingo) or by sharing towels, brushes and combs, clothes, and anything else that touches skin, as well as through surfaces in warm moist areas (like swimming pools). Your little one can also catch ringworm from a pet (clues that your pet has ringworm and needs treatment: scaly, hairless patches, lots of scratching). Ringworm can turn up anywhere on the body, including the face and scalp (where it can be mistakenly identified as a stubborn case of cradle cap) and can be spread from one part of the body to another by scratching. Since it can be confused with other types of rashes, including eczema and seborrhea, proper diagnosis is key. Ringworm on the body can be easily treated with an antifungal cream, but on the scalp it may require an oral antifungal medication, as well as an antifungal shampoo.

Diaper rash. Stating the obvious, diaper rash is a rash or irritation anywhere in the diaper area. See page 58 for more.

Impetigo. Impetigo is a bacterial infection of the skin that occurs when bacteria, such as streptococci or staphylococci, enter the skin through a break, such as a scratch, bite, or irritation. It can also affect eczema-damaged skin. Either blisters or honeycomb-like crusts form, then weep and ooze yellowish fluid. Impetigo can spread quickly to other areas of the skin, making medical treatment necessary in many cases (topical antibiotics and gentle washing for very mild cases or oral antibiotics for a rash that is more widespread)—the doctor will determine which medication is needed after examining the rash. Keeping skin wounds clean with soap and water, and then applying an antibiotic ointment, prevents impetigo.

Prickly heat. Known mainly as heat rash on the sandbox circuit, prickly heat occurs most commonly in babies, but toddlers, children, and even adults can develop the rash as well. Prickly heat, which results when sweat glands clog up, looks like tiny pink pimples on a reddened area of skin that may blister and then dry up. The rash occurs most often around the neck and shoulders, but it can also appear on the back and face, or anywhere skin rubs against skin or clothing constricts. Since the rash is caused by overheating or overdressing, be sure not to overdress your toddler, and keep indoor spaces comfortably cool.

“I know I’m supposed to put sunscreen on my toddler, but that is way easier said than done. She fights it every time.”

Toddlers, as you’ve definitely noticed, fight a whole lot of things that are good for them (say, vegetables)—and even some things that are essential for them (among them car seats, doctor visits, and sunscreen). As always, your best plan of action is distraction. When it’s time to slather up, break out a favorite toy for your toddler to clutch or break into a silly (just-for-sunscreen) song. Try some fast talk, too (“Let’s get this sunscreen on fast so we can go play in the playground!”), lots of good humor, and a positive, upbeat attitude (approach looking for a battle and you’re bound to get one). Being a model of sunscreen smarts will also help (apply your sunscreen, then apply your toddler’s). As your toddler’s comprehension grows, so can an explanation (“Sunscreen keeps the sun from burning our skin”). Most of all, make sunscreen (just like the car seat and the doctor visits) a non-negotiable issue—no sunscreen, no go. The more wiggle room you give now (you skip it because you’re running late, or because she’s having a tantrum), the more struggles you’ll get in the future.