WHAT’S YOUR BIGGEST TODDLER FEEDING CHALLENGE? Pokiness? Pickiness? An allegiance to beige foods—preferably those that don’t comingle—or a suspicion of anything (naturally) green? New texture intolerance? A sweet tooth, or a fried fetish? All of the above? If so, that’s not surprising. Even babies who used to open up wide for whatever was spooned their way often start taking the path of most mealtime resistance (resistance, that is, to anything their parents want them to eat) once they’ve entered their second year. Should you wave the white napkin of surrender, and give up on the idea that your toddler will ever eat a varied, balanced, healthy diet (or even one out of three)? Absolutely not—and here’s why. As finicky as your toddler’s eating habits may seem now, they’re actually more malleable than they’ll probably ever be again (not to mention, your 1-year-old can’t reach the ice cream stash yet or drive to Burger King). Offer up healthy foods now, and your little one will be more likely to reach for them later. Advocate eating for the right reasons (hunger, instead of boredom, for instance) and in the right setting (at the table, not on the sofa in front of the TV), and you’re more likely to raise a child who eats right. Serve up surprises along with those standards (a side of curried cauliflower with that mac-and-cheese, a slice of ripe mango with those chicken fingers), and you may be surprised to see your toddler’s tastes expand beyond the bland and blander (or the sweet and sweeter, or the salty and saltier).

Your toddler’s eating habits are a work in progress (though sometimes, it may be hard to see the progress–especially after the second cereal-only week in a row). They’re busy forming, but they’re far from formed. Which means you’ve got the opportunity of a lifetime to help your toddler form a lifetime of healthy eating habits, ones that can actually help shape a longer, healthier life (new science keeps backing up the old adage: You are what you eat). And there’s no better time to start instilling those habits than now.

To get your little one’s eating habits off to the healthiest start possible, start with these healthy feeding basics:

Bites count (but don’t have to be counted). Given that tiny tummy, that tender appetite, and probably limited tastes, there are just so many bites your toddler can take. In fact, toddlers run on surprisingly few bites a day—and that’s completely normal. That’s why it’s smart to focus—as much as you possibly can—on quality, not quantity. Serve your little one foods that pack nutrients into every bite, however small or few the bites may end up being: whole grain bread instead of white, whole wheat waffles instead of toaster pastries, baked sweet potato wedges instead of fries. Try to limit the number of bites wasted on foods that don’t give back nutrition-wise (a.k.a. junk food).

You pick, your toddler chooses. Let’s face it. If toddlers were in charge (especially older ones), all meals would feature frosting, and broccoli would never find its way into the shopping cart. Fortunately, they’re not in charge—or at least they shouldn’t be. Don’t forget—though it’s easy to when your little one screams for ice cream or clamors for cupcakes—who’s actually running the food department: You. As the adult, you get to pick which foods make it home, and which foods don’t. You also get to pick when foods are appropriate (steamed carrots and hummus before dinner) and when they’re not (cookies for breakfast). After you’ve picked, it’s fine for your toddler to choose from the selection of healthy foods you’ve provided (and remember, it’ll be a lot easier to say “no” to chocolate marshmallow cereal when there isn’t any in the cabinet).

Appetite rules. Toddler eating patterns... well, let’s just say that there’s no predicting them. One day, your toddler plows through two bowls of cereal, a banana, and a yogurt for breakfast, snubs snack, and manages barely a nibble at lunch and dinner. The next day, breakfast is a bust, lunch is lackluster, but a pile of pasta and cheese is demolished at supper. The third day, snacks attack, while meals take a low profile.

The best strategy for you, the feeder? Go with the appetite flow. Serve up a predictable schedule of three meals, supplemented by well-timed snacks, and let your toddler’s appetite dictate how much (or how little) is eaten at each. No pressure to eat more, no recriminations for eating less, no sweat over leftovers or mainly skipped meals. Remember, healthy kids eat as much as they need. Take a look at the big picture—your toddler’s diet over a week, for instance—and you’ll probably see that all those ups and downs in appetite balance out.

Snacks are essential. A toddler’s teeny tank fills up quickly, which means it needs frequent refills, too. That’s where snacks come in. For little ones, snacks provide a steady supply of much-needed fuel for that on-the-go lifestyle, while covering any nutritional gaps barely touched meals leave behind. As long as they’re healthy (think of them as mini-meals—scaled down, but still nutritiously substantial versions of those three squares), they’re just another opportunity for your little one to eat well.

Liquids drown solids. As recent graduates of liquid-only diets, it’s not surprising that most toddlers are big fans of fluids. The problem is, when the fluid of choice is filling (as in juice) and the method of beverage delivery is easy-to-use and readily available (as in the bottle or the sippy cup), a toddler’s appetite for solids can be drowned by too many liquids. To encourage healthy eating, discourage excess drinking. Limit milk intake to 16 ounces a day, juice to no more than 4 to 6 ounces.

Carbohydrates are a complex issue. Bagels, bread, crackers, spaghetti, cereal—even the most finicky toddler usually enjoys at least one member of the carbohydrate family, and some seem to be carb-only consumers. But since all carbs are not created equal, nutritionally speaking, it pays to be picky—and to pick mainly complex carbs when feeding your toddler. Complex carbs provide a wide range of the naturally occurring nutrients, nutrients that are stripped away during the refining process (the process that makes whole grains white)—and nutrients that fuel your little one’s growth and development. Whole grains and other complex carbs (see page 91 for examples) are also digested more slowly than refined ones are, which means that they’ll provide a more steady supply of the energy your toddler needs—while helping prevent those blood sugar crashes that can send a little one’s sunny mood south in a hurry. What’s more, a diet that favors complex carbs over refined ones—especially if it’s started early in life, when those taste buds are being formed—is less likely to lead to obesity and type 2 diabetes. That’s because complex carbs regulate blood sugar best, limiting the amount of circulating sugar that can be converted to fat.

Healthy foods come in colorful packages. So, your little one may not know red from blue, or green from orange yet. But here’s something you should know about color: It can clue you in to nutrition. When a food comes by a vibrant color naturally (red raspberries, not berry-flavored fruit snacks), it’s a sure sign that it’s packed with nutrients your fast-growing toddler needs. Think of all the natural colors of the rainbow when you shop: red tomatoes and strawberries; orange carrots, yams, and melon; blue blueberries (and if you can find them, other blue produce, like blue potatoes); yellow corn and mangoes; green kiwis and broccoli. And the color connection isn’t exclusive to the produce aisle. Whether you’re picking out bread, rice, or cereal, you’ll make a healthier choice if you look for deeper colors (white bread, rice, cereal, and pasta pale in nutritive value next to the darker, whole-grain varieties).

Sugar’s not so sweet. Of course, little ones are sweet on sugar—usually from that very first lick of frosting or crumb of cake. But here’s the scoop on sugar, in case you haven’t heard: It’s full of calories, but empty of nutrients. Foods high in sugar are fine for a once-in-a-while treat, but not-so-fine as a steady diet. Since they’re a waste of precious tummy space (space that’s limited in a toddler), filling up on sugary treats means your little one won’t have room—or appetite—left for healthy foods that offer something to grow on. Worse still, sugary foods are linked to tooth decay (even in those cute little baby teeth) and obesity (in childhood and beyond), and even to other health problems in the future (like heart disease). Plus, once little ones get a taste for the sweet life, it’s hard to get them unhooked (that sugar craving can be tough to kick, as you may know from personal experience). The best sugar strategy? Limit the amount your toddler eats right from the start. Help nurture a taste for foods that are sweet, but not sugar-sweetened (like fruit, sweet potatoes, carrots) and for foods that introduce other tastes altogether (the tanginess of yogurt, the garlicky goodness of hummus, the creaminess of avocado, the spiciness of salsa).

Salt’s hard to lick. If there’s one ingredient as common in the American diet as sugar, it’s salt—in copious quantities. Scan nutrition labels on packaged foods (it’s listed as “sodium”) and you’ll uncover it in obvious places (those salty-tasting potato chips) and in not-so-obvious places (that sweet-tasting cereal). Too much salt, like too much sugar, is a recipe for future health problems. A high-sodium diet is linked to high blood pressure (which is in turn linked to heart disease) and obesity (because salty foods are often also fattening foods). And like a taste for sugar, a taste for salt is hard to lick once it’s acquired (which may be why you can’t imagine life unsalted)—another compelling reason to limit the salt your toddler consumes now. Consider this: Most kids eat about twice the sodium they should.

The best foods remember where they came from. The closer foods stick to their roots, the more natural goodness—and naturally occurring nutrients—they can offer your toddler. That’s why whole wheat bread beats white bread; fresh fruit juice trumps “fruit drink;” real cheese triumphs over the processed kind; an artificially flavored (and colored) blueberry yogurt can’t stand up to one that’s blended with real blueberries. So, whenever you can, choose foods with that fresh-from-the-farm pedigree: fresh (or fresh-frozen) fruits and vegetables, unrefined breads and cereals, unprocessed meat. Prepare those healthy foods in the healthiest way possible, too (steam or roast veggies to preserve vitamins and nutrients, bake chicken instead of frying).

Healthy eating habits begin at home. Where did you form your eating habits? Sure, there were friends’ houses involved (especially once you got to sleepover age), school lunches, ice cream trucks, movie snack bars, maybe camp, possibly college cafeterias. But chances are, when you break it down, most of what you learned about eating you learned at home. So make your home a place where healthy eating lives—and a lifetime of healthy eating habits start. Don’t forget what’s in it for you, either. A family that eats healthy together stays healthy together.

Ever tried to keep track of your toddler’s food intake (so, let’s see: that’s 2½ bites of French toast, 3 blueberries, and a spoonful of yogurt... half a cheese stick and a banana slice... ¼ cup of Cheerios, counting the ones that ended up crushed into the car seat... the majority of a meatball, 10 elbow macaroni, and ¼ cup tomato sauce, most of it used as face paint)? It definitely isn’t easy—and fortunately, it definitely isn’t necessary.

So put away the scorecards, the calculators, the measuring spoons and cups—and stop struggling to add up those nibbles, licks, crumbs, and scraps (which add up faster than you’d think, anyway). The Second Year Daily Dozen outlined below aren’t dietary guidelines to stick to strictly, but a general guide to the types of foods (and food groups) your toddler should be sampling. Instead of trying to keep that running tab of food intake or serving up pressure (in the form of bribes, pleas, or punishment) in an attempt to meet daily quotas, aim to offer a variety of healthy foods for your little one to eat—or not eat—based on appetite. Keep in mind, too, that toddlers need to eat a lot less than their parents usually think—which means those tiny appetites are typically right on target.

Calories. The AAP recommends that toddlers get about 1,000 calories per day. But now that you know that, forget it. You don’t have to count calories to tell if your toddler is getting enough—or too many. Instead, simply keep track of his or her weight at checkup times. If it’s staying on approximately the same curve—allowing for a jump or dip as a thin toddler fills out or a chubby one slims down—caloric intake is on target. Remember, too, that healthy toddlers (ones who aren’t pressured to eat more or eat less) are pretty good at self-regulating their caloric intake. They’ll eat as much as they need in order to grow.

Protein. Little bodies need protein to grow big—but in surprisingly small amounts. In fact, two 8-ounce glasses of milk provide just about all the protein a toddler needs in a day (approximately 16 grams). Anything else—that spoonful of yogurt, that half a fish stick, those three bites of cheese—is just gravy. That said, it’s a good idea to start your tot on a wide variety of protein foods, not only for the nutritional perks (different types of protein foods offer up different nutrients), but for the taste experience. Mix it up as much as you can: dairy products (besides milk, look to yogurt and cheese, including ricotta and cottage cheese), eggs, fish, chicken and turkey, lean meat, beans, edamame, tofu, and whole grains (especially the protein-packed quinoa). Peanut butter and other nut butters (like almond butter) count, too, but be sure to use creamy (not crunchy), spread thinly, and avoid altogether if there are allergy concerns.

Calcium. Your always-busy toddler is busy behind the scenes, too—busy building strong and healthy bones, muscles, and teeth. Essential to that construction project: calcium, and plenty of it. In the second year, your child will need about 500 milligrams of calcium per day—no challenge if you have a milk-lover on your hands (there’s 300 milligrams of calcium in every 8 ounces of the white stuff), and actually not even much of a challenge if you don’t. Other dairy products, such as yogurt and cheese, can also help your toddler bone up on calcium (if you’re counting, yogurt cashes in as much calcium as milk, cup for cup; about 1 ounce of cheese does the same). Nondairy sources can contribute, too—including calcium-fortified juice, tofu and many soy products, and some dark green veggies (admittedly a long shot for little ones, but you never know).

Vitamin C foods. This vital vitamin boosts the immune system, helps heal those scrapes and bruises, and strengthens muscles and blood vessels, putting it high on your toddler’s must-have list. Since the body can’t store vitamin C, you’ll have to serve up a fresh supply daily (yesterday’s berry fest can’t be applied today). Happily, most little ones don’t need any coaxing when it comes to vitamin C. This multitasking vitamin can be found in a multitude of toddler-pleasing fruits and veggies, among them citrus fruits (including the standard OJ), berries, melon, mango, kiwi, broccoli, leafy greens, bell pepper, tomatoes, tomato juice and tomato sauce, and sweet potato. Just one or two servings will C your toddler through the day.

Green leafy and yellow vegetables and yellow fruits. These vitamin A-listers boast a long list of body-building benefits (they’re important for vision, bone and tooth development, immune system maintenance, healthy skin and hair, and much more). Even if green’s not your toddler’s color (broccoli, cooked greens), he or she will find plenty on the yellow/orange A-list to pick from: apricots, cantaloupe, mango, papaya, yellow peach, carrot, winter squash, sweet potato, pumpkin, tomato and tomato sauce, red bell pepper. Aim for one to two servings per day (keeping in mind that many vitamin A-rich foods are also packing C—there’s no need to double up).

Other fruits and vegetables. Round out your tot’s nutritional profile with one or two servings of these other fruits and veggies, which pack vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and fiber: apple, pear, banana, cherries, berries, grapes (cut in half), pineapple, cooked raisins, avocado, green beans, beets, eggplant, turnip, mushrooms, zucchini, okra, green peas, corn.

Whole grains and other complex carbohydrates. Most toddlers are carb cravers, but not all carbs make the nutritional cut. Skip the simple carbs (white bread, white rice, and refined cereals lack naturally occurring nutrients and fiber your little one needs) and go for the whole grain. Aim for about 4 to 6 toddler servings a day (sounds like a lot? A single slice of whole-grain bread offers up 4 toddler servings). Choose from whole-grain bread, pita, bagels, tortillas and wraps, muffins, and crackers; brown rice, quinoa, barley, and bulgur; whole wheat pasta; whole-grain cereal, pancakes, and waffles; lentils, chickpeas, pinto, kidney, navy, or other beans. Keep in mind that wheat isn’t the only grain that comes whole—look, too, for whole corn, whole oats, whole rye, whole barley, and more. How do you know you’re getting those grains whole? Check out the ingredients list—it has to specify “whole” to be whole.

Iron-rich foods. A lot of little ones don’t get enough iron, especially once they’ve moved on from enriched baby cereal and formula. Since this mineral is needed to manufacture red blood cells—and red blood cells are needed to deliver oxygen to every part of the body—it’s important to keep an eye on your toddler’s iron intake (shortfalls can lead to iron-deficiency anemia). Pump up your tot’s diet with good sources of iron, including lean beef, pork, poultry, salmon, eggs, beans, tofu, prunes, cooked raisins, leafy greens, oatmeal, and whole-grain breads, pasta, and cereals. Not sure about your tot’s intake? Check with the doctor.

High-fat foods. No need to be fat-phobic when it comes to your toddler (even if you’re wisely trying to prevent obesity later in life)—just fat-selective. The right amount of the right kind of fat is vital to the development of your toddler’s fast-growing brain and quickly-developing nervous system. Sticking with whole milk until your toddler turns 2 (unless the doctor has advised otherwise) will provide much of that needed fat. When adding other fats, think heart healthy (arteries start clogging early in this fast-food-fed nation): olive and canola oil, avocados, smooth, thinly spread nut butter (if there’s no allergy risk). Stay away from saturated fats (most often found in fast food, junk food, and processed food), particularly trans fats.

Fluids. Your toddler needs no more than 4 to 6 cups of fluid a day (around 2 cups of milk, 4 to 6 ounces of juice, and 2 to 3 cups of water will do the trick)—but no need to count ounces (and what with all those spills and leftovers, it’s tough to keep track). Since it’s a matter of fluid in, fluid out, just keep an eye on those diapers: A toddler who’s getting enough fluid will produce plenty of clear urine; one who isn’t will have dark, scant urine. You’ll need to step up fluid intake to prevent dehydration in hot weather, and also when your little one is down with a cold or fever, has diarrhea, or is vomiting. Water is the most obvious source of fluids—and a great one for your toddler to get a taste (or, non-taste) for—but keep in mind that there’s water, water everywhere, including in fruits and veggies (they’re mostly water), milk, soup, and juice.

Omega-3 fatty acids. Part of the family of essential fatty acids, omega-3’s (such as DHA, EPA, and ALA) should be an essential part of your family’s—and your toddler’s—diet. That’s because omega-3’s are vital for your tot’s normal growth and development, are beneficial for his or her vision and healthy brain development, can help stabilize mood and behavior, and are heart healthy. You’ll find omega-3 fatty acids in plant foods like walnuts, flaxseeds (grind them up and hide them in your tot’s oatmeal), tofu, edamame, and canola oil, and also in fatty fish, especially salmon. If you’re still breastfeeding, remember that breastmilk is a great source of omega-3’s. You’ll also find it in DHA-enriched foods like yogurt, cereal, eggs, nut butters, and even ice cream.

Vitamin supplements. What happens when breakfast (oatmeal with pears) ends up on the floor, lunch (yogurt and cut-up fruit) ends up mashed in your tot’s hair, and dinner (a well-balanced meal of mac-and-cheese with hidden salmon flakes and mashed cauliflower) never leaves the plate? You end up with a toddler who’s missed out on his or her share of daily nutrients. It’s typical, as toddlers are notoriously eccentric and erratic when it comes to eating, and nothing to be concerned about. Your child will probably make up the shortfall another day or tap into his or her stores from the healthy eating he or she did yesterday or last week. But there are some nutrients (vitamin C comes to mind) that can’t be stored and that need to be replenished daily, and others (like vitamin D) that are in short supply in food. Add to that the standard-issue parental worry that can leave nagging doubts in your head about whether your little one’s nutritional intake is up to snuff. Enter a vitamin supplement—a kind of nutritional insurance that can put your mind at ease. But since giving a daily vitamin to toddlers is not an official recommendation (the AAP doesn’t take a position on the subject), it’s up to you, along with the doctor, to decide whether or not to invest in that insurance. If you do opt to add a vitamin supplement to your toddler’s diet (ask your pediatrician for a brand recommendation), use a liquid preparation until your toddler’s molars are in, then switch to chewables when your child can be depended upon to chew a tablet thoroughly. Store them well out of your toddler’s reach, and never refer to them as “candy.” Their colors and shapes, aroma and taste can be extremely enticing, which is good, since it makes them attractive and palatable to children, and bad, since it can make them too tempting. Most of all, remember that vitamin supplements should never be viewed as a replacement for nutritious foods. The body absorbs nutrients from foods much more effectively than it absorbs nutrients from supplements. So if you constantly find yourself relying on a multivitamin to counteract the chips your child clamors for or to make up for the fact that produce always seems to be passed up, you probably should rethink your strategy.

“I’m still nursing my daughter, and neither one of us is ready to give it up. Is there any reason to wean?”

Actually, if you’re still both on board with the breast, there’s absolutely no reason to jump ship. In fact, the AAP has an official policy to that effect: Breastfeeding should continue, ideally, for at least a year—and then for as long as mom and child want to keep it up. For some nursing teams, a year (or even less) is enough, while others are still going strong through the second year and beyond.

So wean when the time’s right for both of you (if the time is right for her but not for you, see the next question). Just keep an eye—as you keep up those cuddly nursing sessions—on solids intake (once that first birthday is celebrated, a busy toddler needs more protein, vitamins, and other nutrients than breast milk alone can provide) and appetite (toddlers who drink too much from breast or bottle can drown their appetite, so if your little one seldom seems hungry for solids, nurse after meals instead of before). Supplementing with cow’s milk may also be a smart move—even as you continue to breastfeed—since it offers up essential vitamin D. Also, try to brush your toddler’s teeth after nighttime breastfeeds and consider nipping middle-of-the-night feeds altogether (some dentists link these to baby-bottle mouth, though it’s clearly less common among nursing toddlers than those who sip from a bottle or a sippy spout).

“My son seems ready to stop nursing—he struggles and pushes away from my breast when I try. But I’m so not ready.”

Breastfeeding can be one of life’s most satisfying experiences, but it definitely takes two willing participants. Before you decide your toddler is no longer willing, though, you may want to take a closer look. Sometimes, a baby or toddler will go on a temporary nursing strike because of a stuffy nose, an achy ear, a painful bout of teething. If it’s clear, however, that he’s had enough of this good thing—if he seems just as happy (or happier) with a cup of milk, a meal, and his freedom from laptop feedings—it’s time to move on, Mom. So follow his lead, as understandably hard as it may be for you to make the break. If you can convince him to continue just long enough to make the break less painful for your breasts, try to wean gradually. If not, just add that to the long—but well worthwhile—list of sacrifices you’ll be making over your mommy career.

Either way, try not to take his rejection of your breast as a rejection of you—it isn’t. It’s a rejection of dependence—and that’s a normal developmental step some kids take sooner, some take later, but all take eventually. It’s also probably a rejection of being stuck in your lap for hours a day when he’d rather be on the go.

Best to get your cuddles when you can, most likely on his terms from now on. Make your lap available, but not required seating. And remember, there are plenty of other ways to stay close with your toddler, now and later, that won’t threaten his newfound autonomy.

“I know I’m supposed to start weaning my son from the bottle now that he’s a year old, but I can’t imagine he’s ready.”

Timing may not be everything when it comes to weaning—but it’s a lot. And if there ever was an ideal time to wean your toddler from the bottle, you’re looking at it now, for all sorts of reasons, including:

You’ve got flexibility. Okay, it’s relative. Your toddler’s not the putty in your hands he was six months ago. But he’s also not the independence-fighting insurgent he’s scheduled to become six months or a year from now. Once he really gets the hang of kicking and screaming (peaceful protests aren’t so much a toddler’s thing), getting your little one to cooperate in just putting his shoes on—never mind in major lifestyle changes, like giving up the bottle—may become a much bigger challenge.

You’ve got flexibility. Okay, it’s relative. Your toddler’s not the putty in your hands he was six months ago. But he’s also not the independence-fighting insurgent he’s scheduled to become six months or a year from now. Once he really gets the hang of kicking and screaming (peaceful protests aren’t so much a toddler’s thing), getting your little one to cooperate in just putting his shoes on—never mind in major lifestyle changes, like giving up the bottle—may become a much bigger challenge.

You’ve got milk. Those formula days are over, and there’s a new beverage in town. What better time to retire that old beverage conveyer, the bottle?

You’ve got milk. Those formula days are over, and there’s a new beverage in town. What better time to retire that old beverage conveyer, the bottle?

You’ve got solids. Back in those baby-bottle days, your little one got fed by drinking (breast milk or formula or both). But solids are the new liquid for toddlers—and they’ve taken on much more nutritional significance. Bottle drinkers tend to take in too many calories from milk and juice, leaving them little appetite for the solid food they need to help them grow and help them gain eating experience. Those who manage to find room for the solid calories on top of the liquid ones can end up gaining too much weight. More good reasons to make the break from the bottle now.

You’ve got solids. Back in those baby-bottle days, your little one got fed by drinking (breast milk or formula or both). But solids are the new liquid for toddlers—and they’ve taken on much more nutritional significance. Bottle drinkers tend to take in too many calories from milk and juice, leaving them little appetite for the solid food they need to help them grow and help them gain eating experience. Those who manage to find room for the solid calories on top of the liquid ones can end up gaining too much weight. More good reasons to make the break from the bottle now.

You’ve got teeth to consider. So-called “baby-bottle mouth” (bottle-induced tooth decay) can affect any child with teeth, but the more teeth, the greater the potential for those serious dental problems. The issue isn’t just the fluid in the bottle (unless that fluid is water), but the mechanism of bottle-feeding. Instead of sipping and swallowing—as a child does with a regular cup—a bottle (and to a certain extent a sippy cup) allows liquids to pool in the mouth before they’re swallowed. Unless they’re brushed away, the sugars in the liquids (lactose in milk and fructose in juice) are broken down by bacteria in the mouth. During the process an acid is formed, which feasts on protective tooth enamel, causing decay.

You’ve got teeth to consider. So-called “baby-bottle mouth” (bottle-induced tooth decay) can affect any child with teeth, but the more teeth, the greater the potential for those serious dental problems. The issue isn’t just the fluid in the bottle (unless that fluid is water), but the mechanism of bottle-feeding. Instead of sipping and swallowing—as a child does with a regular cup—a bottle (and to a certain extent a sippy cup) allows liquids to pool in the mouth before they’re swallowed. Unless they’re brushed away, the sugars in the liquids (lactose in milk and fructose in juice) are broken down by bacteria in the mouth. During the process an acid is formed, which feasts on protective tooth enamel, causing decay.

And health issues, too. Toddlers who keep nipping from a bottle, especially when they’re lying flat on their backs, run a higher risk of ear infection.

And health issues, too. Toddlers who keep nipping from a bottle, especially when they’re lying flat on their backs, run a higher risk of ear infection.

You’ve got support. The AAP and the AAPD both recommend weaning children from the bottle at 12 months.

You’ve got support. The AAP and the AAPD both recommend weaning children from the bottle at 12 months.

That pile of reasons for weaning now, however, may not stack up against other considerations you’re facing—like a big change or stress in your child’s life (a new home, a new babysitter) or in yours (a new job or a job search, a sick parent, financial issues). The time that’s right for you and your toddler is always the best time. No matter when in the second year you get around to weaning, amen to the expression “Better late than never”!

“I know it’s time to get my toddler on a cup, but whenever I hand her one, she pushes it away and points to her bottle—and I give up, again.”

Having trouble getting your little one to join the cup club? That’s probably because membership wasn’t her idea. A toddler usually has no problem trying new things—that is, as long as the new things aren’t offered up by others (namely, parents). Grabbing a handful of green grass and shoving it into her mouth? Fine. Having a spoonful of green broccoli waved her way? Not so fine. Going for dad’s cup of coffee when he’s not looking? Just the ticket. Having dad hand her a cup of her own, and encouraging a sip? Not a chance.

Of course, you know your toddler will take a cup eventually. The trick will be getting her to sign up for the cup club sooner than later, so she can leave bottles to the babies. Here’s how:

Stop passing the cup. For a few days, don’t even bring up the cup. This will allow for a fresh start to what’s become a stale campaign. Stash the cups you’ve been trying to foist on her out of sight, so you don’t resurrect any conflicts.

Stop passing the cup. For a few days, don’t even bring up the cup. This will allow for a fresh start to what’s become a stale campaign. Stash the cups you’ve been trying to foist on her out of sight, so you don’t resurrect any conflicts.

But pass the glass. If she makes a grab for your juice glass or your water bottle, by all means let her have a supervised sip. Just because she doesn’t want to drink what dad puts in front of her doesn’t mean she doesn’t want to be just like dad. Some kids like to bypass the baby stuff and move right on to adult drinking equipment (anything breakable or spillable will need adult supervision).

But pass the glass. If she makes a grab for your juice glass or your water bottle, by all means let her have a supervised sip. Just because she doesn’t want to drink what dad puts in front of her doesn’t mean she doesn’t want to be just like dad. Some kids like to bypass the baby stuff and move right on to adult drinking equipment (anything breakable or spillable will need adult supervision).

Go shopping... together. It goes without saying that taking your toddler to the store is something you do only when you need to. Well, you need to. Letting her pick out a new cup or two will help give her that sense of control she craves. Show her two at a time, and allow her to select her favorites (if you can, get a couple of different styles, maybe one with handles, one without, one with a straw, one that has a spout)—and don’t underestimate the power of cute characters or magical gimmicks, like cups that change colors.

Go shopping... together. It goes without saying that taking your toddler to the store is something you do only when you need to. Well, you need to. Letting her pick out a new cup or two will help give her that sense of control she craves. Show her two at a time, and allow her to select her favorites (if you can, get a couple of different styles, maybe one with handles, one without, one with a straw, one that has a spout)—and don’t underestimate the power of cute characters or magical gimmicks, like cups that change colors.

Have a cup playdate. Getting to know the cup may help her get to love it, or at least, try sipping from it. Show her how she can use it to feed her dolls or serve you “tea.” Seeing you sip from it, by the way, may ignite a typically territorial reaction in your toddler—before you know it, she may be clamoring to drink from “my cup!”

Have a cup playdate. Getting to know the cup may help her get to love it, or at least, try sipping from it. Show her how she can use it to feed her dolls or serve you “tea.” Seeing you sip from it, by the way, may ignite a typically territorial reaction in your toddler—before you know it, she may be clamoring to drink from “my cup!”

Make it available, not an issue. Remember, she’s more likely to sip from the cup if it’s her idea than if it’s yours. So instead of trying to coerce or cajole a sip before the breast or bottle (good luck with that plan), casually make it available at meals. The less attention you pay to the cup, the more likely she is to pick it up and surprise you with a sip.

Make it available, not an issue. Remember, she’s more likely to sip from the cup if it’s her idea than if it’s yours. So instead of trying to coerce or cajole a sip before the breast or bottle (good luck with that plan), casually make it available at meals. The less attention you pay to the cup, the more likely she is to pick it up and surprise you with a sip.

Pull a switch. You’ve been filling it up with milk? Switch to watered-down juice. Or try something completely different—something she likely never encountered in a bottle—like a sipable fruit-and-milk smoothie.

Pull a switch. You’ve been filling it up with milk? Switch to watered-down juice. Or try something completely different—something she likely never encountered in a bottle—like a sipable fruit-and-milk smoothie.

Let the weaning begin. The immediate objective is trying the cup, but don’t lose sight of the ultimate goal: Giving up the bottle. Just don’t let your toddler in on your plan. As she starts getting on friendlier terms with the cup, gradually cut back on the fluids she’s taking from the bottle (just keep an eye on her fluid intake, to make sure she’s getting enough). Whatever you do, try not to associate joining the cup club with revoking her membership in the bottle club. Otherwise, she’ll reject the former and cling to the latter.

Let the weaning begin. The immediate objective is trying the cup, but don’t lose sight of the ultimate goal: Giving up the bottle. Just don’t let your toddler in on your plan. As she starts getting on friendlier terms with the cup, gradually cut back on the fluids she’s taking from the bottle (just keep an eye on her fluid intake, to make sure she’s getting enough). Whatever you do, try not to associate joining the cup club with revoking her membership in the bottle club. Otherwise, she’ll reject the former and cling to the latter.

Drinking without dribbling will take lots of practice. Diaper-only practice sessions minimize mess.

Cover all bases. Drinking from a cup will be a messy business until your toddler becomes a pro (unless you’re using a spill-proof sippy cup—and for experience’s sake, you shouldn’t always do so). Prepare for messes, but keep your cool when they happen... and they will.

Cover all bases. Drinking from a cup will be a messy business until your toddler becomes a pro (unless you’re using a spill-proof sippy cup—and for experience’s sake, you shouldn’t always do so). Prepare for messes, but keep your cool when they happen... and they will.

“I just never got around to weaning my daughter from the bottle. Since she seemed so happy with it, I kept putting it off. Now that she’s almost 2 and is so stubborn about everything, I don’t know how I’ll ever get her off it.”

Weaning from a bottle at any age can be challenging, and weaning at the infamously inflexible age of 2, as you’ve guessed, considerably more so. But with a lot of patience and determination, a little friendly persuasion, and a minimum of pressure, it can be accomplished. Here’s how:

Try the weaning tips on page 96. They can work just as well for an older toddler as a younger one.

Try the weaning tips on page 96. They can work just as well for an older toddler as a younger one.

Bottle water. A water-only policy will almost certainly make the bottle less appealing. It’ll also protect her teeth while she’s kicking the bottle habit.

Bottle water. A water-only policy will almost certainly make the bottle less appealing. It’ll also protect her teeth while she’s kicking the bottle habit.

Hand over the choice. If there’s one thing you’ve learned about your toddler over the past year, it’s that she’s a control freak—most toddlers are. So instead of forcing the issue (you know where that’s going to get you), put the choice in her hands next time she asks for a bottle... literally. Offer up a bottle of water in one hand, a cup of her favorite beverage in the other, and let her choose. After she realizes she can’t hold both at the same time (she’ll probably try that first), she may decide that having her favorite drink beats having her favorite container. Even if she doesn’t take the cup the first time, or the second, keep on trying—eventually, she’s likely to reach for it. Of course, the success of this strategy—like most strategies involving your toddler—depends on you not caving. Stand firm on water-only in the bottle, even if she whines to have her choice refilled with milk or juice.

Hand over the choice. If there’s one thing you’ve learned about your toddler over the past year, it’s that she’s a control freak—most toddlers are. So instead of forcing the issue (you know where that’s going to get you), put the choice in her hands next time she asks for a bottle... literally. Offer up a bottle of water in one hand, a cup of her favorite beverage in the other, and let her choose. After she realizes she can’t hold both at the same time (she’ll probably try that first), she may decide that having her favorite drink beats having her favorite container. Even if she doesn’t take the cup the first time, or the second, keep on trying—eventually, she’s likely to reach for it. Of course, the success of this strategy—like most strategies involving your toddler—depends on you not caving. Stand firm on water-only in the bottle, even if she whines to have her choice refilled with milk or juice.

Offer incentives. Here’s the good part about belated bottle weaning—your older, wiser toddler can now understand the concept of a rewards program (I-do-this, I-get-that). Incentives work well, especially for one-time developmental achievements (though they can clearly be overused—as in, you start using them every time you want your toddler to comply with anything). Let your toddler know that there’s something special in store for her if she gives up her bottle: a new book, stickers, a toy, a trip to the zoo—nothing over the top, but just enough to convince her that quitting is worth her while.

Offer incentives. Here’s the good part about belated bottle weaning—your older, wiser toddler can now understand the concept of a rewards program (I-do-this, I-get-that). Incentives work well, especially for one-time developmental achievements (though they can clearly be overused—as in, you start using them every time you want your toddler to comply with anything). Let your toddler know that there’s something special in store for her if she gives up her bottle: a new book, stickers, a toy, a trip to the zoo—nothing over the top, but just enough to convince her that quitting is worth her while.

Play up the perks. She knows the benefits of sticking with her bottle. Now it’s time to try selling the benefits of giving it up—namely, being a big girl, and all the privileges that go along with that status. Entice her with a few big-girl perks: sitting in a grown-up chair instead of a high chair for meals, using a big-girl spoon instead of her baby spoon, and so on.

Play up the perks. She knows the benefits of sticking with her bottle. Now it’s time to try selling the benefits of giving it up—namely, being a big girl, and all the privileges that go along with that status. Entice her with a few big-girl perks: sitting in a grown-up chair instead of a high chair for meals, using a big-girl spoon instead of her baby spoon, and so on.

Use the tooth defense. Explain that drinking from a bottle can give her teeth boo-boos, and that drinking from a cup will make her teeth strong, happy, and healthy.

Use the tooth defense. Explain that drinking from a bottle can give her teeth boo-boos, and that drinking from a cup will make her teeth strong, happy, and healthy.

Call the authorities. Your little one may be just about big enough to be impressed (possibly even influenced) by the powers that be, at least the nonparental powers that be. That definitely goes for doctors and dentists. So make an appointment with the doctor or dentist and have them explain why drinking from a bottle can hurt her teeth.

Call the authorities. Your little one may be just about big enough to be impressed (possibly even influenced) by the powers that be, at least the nonparental powers that be. That definitely goes for doctors and dentists. So make an appointment with the doctor or dentist and have them explain why drinking from a bottle can hurt her teeth.

Cheer her on. Breaking a habit is hard to do—as you probably know from your own experience. What makes it harder? Anything that steps up stress (like pressure from your parents—which, of course, also steps up rebellion). What makes it easier? Lots and lots of positive reinforcement. So, keep pressure to a minimum (and definitely don’t threaten or belittle your little one because she’s having a tough time giving up the bottle), and offer her the support, understanding, and extra attention she may need while she weans. Once she’s reached this major milestone, provide both the reward she’s earned and the cheers she deserves.

Cheer her on. Breaking a habit is hard to do—as you probably know from your own experience. What makes it harder? Anything that steps up stress (like pressure from your parents—which, of course, also steps up rebellion). What makes it easier? Lots and lots of positive reinforcement. So, keep pressure to a minimum (and definitely don’t threaten or belittle your little one because she’s having a tough time giving up the bottle), and offer her the support, understanding, and extra attention she may need while she weans. Once she’s reached this major milestone, provide both the reward she’s earned and the cheers she deserves.

“We’ve been trying to switch our son over to cow’s milk, but he won’t touch it. I’m afraid he won’t get enough calcium without it.”

Milk may be the most popular source of calcium in a healthy diet—especially among the playground pack—but it’s certainly not the only one. An 8-ounce glass of milk contains about 300 milligrams of calcium, but so does about 1 ounce of cheese or 1 cup of yogurt (opt for whole-milk dairy products to ensure adequate fat intake, unless the doctor has recommended otherwise). Calcium-fortified juices count, too—though since juice intake should be limited, you won’t be able to fill your tot’s calcium requirements on juice alone.

Sometimes, it’s just a matter of time before a tot develops a taste for milk—so definitely don’t give up, and absolutely keep offering (but not pushing) sips. If you haven’t already, you can try mixing milk half and half with familiar formula or breastmilk, gradually transitioning to all milk as your little one becomes accustomed to the new flavor. Or sneak milk into fruit smoothies, soup, and cereal (make hot cereal with milk instead of water).

While you’re smart to keep an eye on your little one’s calcium intake, there’s another vital bone-boosting nutrient he might be missing if he’s not a milk drinker: vitamin D. Check in with his doctor to see if a supplement’s a good idea to fill in any gaps.

“I just weaned my toddler from the breast to cow’s milk, and all of a sudden she’s having some symptoms—a little diarrhea, a little runny nose, some wheezing—that make me wonder if she could have a cow’s milk allergy.”

Milk and toddlers usually go together like... well, like milk and cookies. But it’s not always a match made in high-chair heaven. For 2 percent of little ones, a milk allergy stands between them and childhood’s favorite cookie chaser. The symptoms include some that your toddler has shown (diarrhea, wheezing, a runny nose), as well as an uncomfortable host of others she hopefully escaped (such as eczema, constipation, irritability, poor appetite, and fatigue). They usually kick in as soon as milk is served up (in the first year if cow’s milk formula was given, or once a breastfed or soy milk formula-fed 12-month-old takes that first sip of whole milk). To find out for sure whether your toddler is among that milk-allergic minority, check with the doctor for an official diagnosis.

Happily, milk allergies are often short-lived—and most kids can move on to milk by the end of the third year, just in time for those classic after-preschool snacks. Until then, she’ll probably have to stick with the less conventional—but nearly as nutritious—soy milk, that is, if she doesn’t turn out to have a soy allergy, too (almond milk and coconut milk, in case you’re wondering, are not nutritionally equivalent to cow’s milk, and goat’s milk is likely to trigger an allergic reaction, too). Cow’s milk cheese, yogurt, ice cream, and other dairy products will also have to stay off the menu until she’s outgrown the allergy, though there are soy equivalents of all of these, too. Meanwhile, discuss with the doctor how she can make up for the nutrients she’s missing in milk, most notably calcium and vitamin D. Check in with the doctor, too, about her fat and protein intake, since most tots get a hefty share of these nutrients from whole milk.

“Our daughter was the world’s best eater when she was a baby. But now she barely eats anything. What’s going on?”

Is your 1-year-old clamping shut instead of opening wide? That’s not surprising, and it isn’t unusual, either. Here’s why:

An identity crisis—the crisis being, she’s just realized she has an identity. It’s no coincidence that toddlers start to put their foot down (at mealtime, bedtime, really any time) just about the same time they start standing on two feet. Derailing that “choo choo train” delivery of cereal that’s trying to access the “tunnel” is one of many ways she’ll be establishing her autonomy—and she’s right on schedule.

An identity crisis—the crisis being, she’s just realized she has an identity. It’s no coincidence that toddlers start to put their foot down (at mealtime, bedtime, really any time) just about the same time they start standing on two feet. Derailing that “choo choo train” delivery of cereal that’s trying to access the “tunnel” is one of many ways she’ll be establishing her autonomy—and she’s right on schedule.

A normal weight slowdown. My, how your little one has grown in the first year—more than tripling her birth weight by the time you served up her first birthday cake. Problem is, if she kept growing at such a rapid rate, she’d weigh as much as a fifth grader when she turned 2. Fortunately, her body opts to put the brakes on her appetite instead, slowing down weight gain before it reaches Humpty Dumpty proportions.

A normal weight slowdown. My, how your little one has grown in the first year—more than tripling her birth weight by the time you served up her first birthday cake. Problem is, if she kept growing at such a rapid rate, she’d weigh as much as a fifth grader when she turned 2. Fortunately, her body opts to put the brakes on her appetite instead, slowing down weight gain before it reaches Humpty Dumpty proportions.

Life on the run. Who has time to pencil a meal into a schedule as busy as your toddler’s? There’s walking to practice, climbs to attempt, trouble to get into. Plus, eating is something that’s done sitting down, at least when parents have their way—a real downer for someone who’s just learned to stand up.

Life on the run. Who has time to pencil a meal into a schedule as busy as your toddler’s? There’s walking to practice, climbs to attempt, trouble to get into. Plus, eating is something that’s done sitting down, at least when parents have their way—a real downer for someone who’s just learned to stand up.

An improved memory. A baby feeds like there’s no tomorrow—or no next feeding. But a toddler is able to reason, “They feed me several times a day around here. If I don’t eat now, I can eat later.” If she’s otherwise occupied (and when isn’t she?), she may see no need to break for a meal.

An improved memory. A baby feeds like there’s no tomorrow—or no next feeding. But a toddler is able to reason, “They feed me several times a day around here. If I don’t eat now, I can eat later.” If she’s otherwise occupied (and when isn’t she?), she may see no need to break for a meal.

In other words, your little hunger striker is just being a textbook toddler—taking her developmental cues from Mother Nature (and not her own mother, or father). If that doesn’t reassure you enough, consider this: Study after study has shown that healthy toddlers who aren’t pushed or prodded to eat consume all the food they need to grow on. What’s more, they’re less likely to develop eating issues or weight issues later on.

Still not quite convinced that your toddler’s appetite slump is normal? Here’s something else you should know. Toddlers need to eat a lot less than their parents usually think. Case in point: a toddler-appropriate serving of sweet potato? Only about two to three 1-inch cubes (see box, page 93). So get in the habit of thinking spoonfuls, not cupfuls. Too much food on a plate can easily overwhelm a petite appetite. If she’s hungry at meal’s end, she can order up seconds.

Need even more reassurance? Check with the doctor, especially if symptoms of illness are accompanying an appetite slowdown.

Is your toddler picky, picky, picky too? See page 109 for tips on finessing the finicky eater.

“One day my son will eat nonstop, the next day he’ll eat next to nothing. Is that normal?”

Left to his own appetite—and it’s best if he is, as long as he’s thriving—the typical toddler’s food intake will vary from meal to meal, day to day, week to week, month to month. Maybe he’ll consistently eat one big meal a day and pick at the others. Maybe he’ll graze his way through every meal. Or nibble one day, gobble another. His appetite may speed up when he’s going through a growth spurt, or slow down when he’s teething or otherwise out-of-sorts. Scrutinize each meal, or even each day’s worth of meals, and you’re bound to see a lopsided nutritional equation. Check out the big eating picture (instead of the leftovers on his plate last night), and you’ll almost certainly see that his food intake balances out over time.

So instead of trying to micromanage your toddler’s eating habits (you’ll meet with limited success), try letting him be the master of his own appetite. Offer small portions of healthy food at regular intervals, and let him decide if he’s hungry and when he’s full—no matter how much he’s eaten, or not eaten, whether he’s plowed through a third portion or hasn’t made it halfway through the first. There are two bonuses to this approach. First, you won’t be driving yourself (or your toddler) crazy at mealtimes by counting uneaten peas or prodding for “one more bite.” Second, and most important, you’ll be raising a child (and eventually, an adult) who has healthy attitudes toward eating (“I eat when I’m hungry, I stop when I’m full”).

“I wasn’t exactly expecting neat eating at this age. But my toddler throws and smears more food than he actually eats.”

For toddlers, enjoying food means smearing it, tossing it, mashing it, and squishing it (the tot equivalent to a wine taster’s sniffing and swishing... and come to think of it, both involve spitting, too). Sure, you don’t want to spoil your toddler’s food fun—and yes, you’ve heard that toddlers learn about their environments through tactile experimentation and feeling the food between their fingers—but must you wave the white paper towel of surrender in the name of your toddler’s good time at the table? Let the food fly—and spill, and crust—where it may? Well, not exactly. You can try these mess-minimizing mealtime tactics:

Rationing. Serve up a mess of food to your toddler, and he’s sure to serve up a mess to you. Instead, place just a few bites in front of your child at a time. Add a few more as those are consumed, if they’re consumed.

Rationing. Serve up a mess of food to your toddler, and he’s sure to serve up a mess to you. Instead, place just a few bites in front of your child at a time. Add a few more as those are consumed, if they’re consumed.

Occupation. To keep those chubby hands busy, give your toddler props. Literally. Hand over the spoon, if you haven’t already. Not only will your toddler love running the eating show, the challenge of bringing food to his mouth with this novel gadget may also distract him from overturning the cereal bowl onto the cat’s head. A little high-chair chat may divert, too, while passing on valuable social skills. If conversation doesn’t cut it, substitute an acceptable game for the objectionable one: “You take a bite of your cheese and then I’ll take a bite of mine.”

Occupation. To keep those chubby hands busy, give your toddler props. Literally. Hand over the spoon, if you haven’t already. Not only will your toddler love running the eating show, the challenge of bringing food to his mouth with this novel gadget may also distract him from overturning the cereal bowl onto the cat’s head. A little high-chair chat may divert, too, while passing on valuable social skills. If conversation doesn’t cut it, substitute an acceptable game for the objectionable one: “You take a bite of your cheese and then I’ll take a bite of mine.”

Suction. Forget sliced bread (it’s only going to land on the jelly side when it’s tossed to the floor)—there is no better invention, at least as far as parents of little ones are concerned, than a bowl that attaches to a table or high-chair tray with suction. It can’t promise no fuss or no muss—but it can promise no bowl of macaroni flung across the kitchen like a Frisbee.

Suction. Forget sliced bread (it’s only going to land on the jelly side when it’s tossed to the floor)—there is no better invention, at least as far as parents of little ones are concerned, than a bowl that attaches to a table or high-chair tray with suction. It can’t promise no fuss or no muss—but it can promise no bowl of macaroni flung across the kitchen like a Frisbee.

Stick-to-it-ness. Try to serve foods that don’t just stick to his ribs, but to the bowl, plate, and spoon. Mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, cottage cheese, chunky applesauce, pureed peaches, slightly mashed bananas, oatmeal, or egg salad.

Stick-to-it-ness. Try to serve foods that don’t just stick to his ribs, but to the bowl, plate, and spoon. Mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, cottage cheese, chunky applesauce, pureed peaches, slightly mashed bananas, oatmeal, or egg salad.

Protection. Besides the obvious—paper towels or dish towels and wipes (and lots of them)—you can cut down on cleanup by spreading plastic or newspaper under the high chair and seating your toddler as far from nonwashable furniture as possible. Preferred mealtime dress code: an over-the-shoulder bib or diaper only.

Protection. Besides the obvious—paper towels or dish towels and wipes (and lots of them)—you can cut down on cleanup by spreading plastic or newspaper under the high chair and seating your toddler as far from nonwashable furniture as possible. Preferred mealtime dress code: an over-the-shoulder bib or diaper only.

Reinforcement. When your little mess-maker makes a little less mess at mealtime, reward him with a reinforcing round of applause. On the flip side, when he flips the French toast over the side of the table or pours milk down his T-shirt, skip the eye roll or exasperated groan. The more attention paid to mess-making, the more mess he’ll make.

Reinforcement. When your little mess-maker makes a little less mess at mealtime, reward him with a reinforcing round of applause. On the flip side, when he flips the French toast over the side of the table or pours milk down his T-shirt, skip the eye roll or exasperated groan. The more attention paid to mess-making, the more mess he’ll make.

A three-strikes-and-you’re-out policy. Or two strikes, or four, or whatever you feel you can stick to. Let your toddler know—calmly, firmly—that when the mess leads to mealtime mayhem, the meal will be called. After the requisite number of “No playing with your food” warnings, follow through—and take the meal away.

A three-strikes-and-you’re-out policy. Or two strikes, or four, or whatever you feel you can stick to. Let your toddler know—calmly, firmly—that when the mess leads to mealtime mayhem, the meal will be called. After the requisite number of “No playing with your food” warnings, follow through—and take the meal away.

“I know I’m supposed to let my daughter feed herself. But I really hate the mess she makes, so I always end up taking the spoon from her.”

If a toddler with a spoon can be considered armed and dangerous, this could be your year of living dangerously. Disarming her—and wielding the spoon yourself—will definitely cut down on the mess, but it’ll also cut down on the opportunities she has to self-feed (something she’ll have to learn eventually anyway, unless you plan on following her around with a fork and knife for the next 20 years). Feeding herself feeds her independence, social skills, and healthy attitudes about food (she won’t ever force herself to eat when she’s not hungry, but you might).

No, she won’t be giving Miss Manners a run for her table etiquette anytime soon. And you’ll still need to continue the search for the most absorbent paper towels and the best shammy cloths that infomercials have to offer. But there’s no better way to instill a future of good eating habits than by putting up with some messy ones now. Toddler, feed thyself.

“My toddler has started blowing his food. It’s cute, but annoying—and messy. And the problem is, I can’t help cracking up.”

Nothing brings out the ham in a toddler like an audience—and nothing brings out the oatmeal, junior carrots, and yogurt like one, either. At 6 and 7 months of age, your little guy probably started making razzing sounds (and may even have picked them up from you, when you blew juicy razzes on his adorable belly after the bath). Innocent enough, at first. But it wasn’t long before he realized that a razzing sound combined with squishy or liquidy food creates the ultimate sight-and-sound show. This realization, of course, is reinforced every time you react, whether by giggling, jumping three feet in the air (as a mouthful of soggy cereal goes splat onto your freshly blow-dried hair or dry-cleaned suit), or even going ballistic (negative attention, every toddler knows, is better than no attention at all). Clearly, it’s time for some stage managing:

Give him new props. Certain foods, he’s probably learned, blow better than others. So beat him at his own game. When possible, substitute slivers of soft melon or a cube of well-cooked sweet potato over strained fruits and veggies. Think easy to gum, but not easy to blow: cubes of soft French toast, pasta shapes, tidbits of cheese, fish fingers. Serve the gooey stuff—like yogurt—as a dip, instead of as the headliner.

Don’t let him blow you away. This is the hard part, but try not to flinch... or chuckle... or smirk... or blow a gasket when he blows food your way, or any way. No reaction, no satisfaction. If he’s not getting the buzz he’s looking for, he’ll get bored by his own tricks.

Bring down the curtain. He needs to know that if he keeps blowing, he’s blown it. With a poker-straight face, give him a simple, firm warning, “No blowing food. We eat food.” If the blowing continues, repeat, “No blowing,” and add, “If you blow food, I am going to take the food away.” The third time he razzes (but be consistent, whether it’s two, or three, or four warnings), remove the meal promptly. Even if he doesn’t understand at first, he’ll make the connection—and get the message—soon.

“Help! My son won’t eat any food that’s touching another kind of food.”

Of course he won’t. He’s a toddler—and most toddlers have plenty of funky food fixations. For this particular fetish, keep your purist happy by dividing to conquer. Use a divided dish and fill each compartment with a different food. Or serve each food in its own separate bowl. And don’t worry that you’re catering to your toddler’s compulsion. If you matter-of-factly comply, this very common fetish will eventually run its quirky course. On the other hand, if you scold, dish up snarky comments, or roll your eyes, it may very well get worse.

“My toddler has a fit if the cracker or cookie I give her has a piece broken off. What’s her problem?”

Most toddlers like things just so—consistently just so. A predictably intact cookie brings a little one comfort, the same kind of comfort that comes from knowing that cereal will always come in the blue bowl every morning, and that she’ll always be wrapped in the bunny towel after every bath. Sounds a little compulsive, but it’s just one more of the many ways that a toddler tries to control her environment.

When the age of reason dawns (probably sometime after her third birthday), your child will begin to accept the way the cookie crumbles—and that broken cookies taste exactly like unbroken ones. In the meantime, humor her when you can (if you have an unbroken cookie on hand), and offer a sympathetic reality check when you don’t (“See, all the cookies in the box are broken—let’s just pick the one you like most”). And when she breaks her own cookie, think of that as a teachable moment (actions have consequences—she’s broken her cookie, she lives with it... or eats it).

“My daughter is such a picky eater. She’ll never try anything new, just the same-old-same-old—and sometimes she won’t even eat that. I’m so frustrated!”

Picky, picky, picky? Most toddlers are. Some are predictably picky (only Cheerios, banana slices, and pasta-no-sauce need apply). Others, selectively so (one day, cauliflower makes the cut, the next day, it’s snubbed). Control (“I’m the boss of me, you’re not”) certainly factors into fussiness, as it does into most stereotypical toddler behaviors. So does the need for comforting consistency, without any unsettling surprises (like discovering blueberries in the Cheerios instead of the accustomed banana). But there’s another reason why some little ones won’t venture out of the familiarly bland, and it’s a product of physiology, not psychology: Their taste buds are hypersensitive to new flavors, especially strong ones. So when your toddler turns up her button nose at broccoli, it may actually be because it tastes really bad to her. New textures may also be literally hard to swallow.

So what’s the parent of a fussy eater to do? Continue pushing and prodding a varied-diet agenda? Or give in to her menu of monotony (and sometimes, not even that)? Actually, neither. Instead:

Start small. Sometimes size matters. A mountain of food (no matter what food) can overwhelm a little eater—causing her to give up before she’s started. Keeping first portions small (see the box on page 93) will make them easier to negotiate. You can always offer seconds if the first little pile is polished off.

Serve up a side of new. Of course she’s having the usual, and that’s fine. But that doesn’t mean you can’t offer up a side of something new and unexpected (on a separate plate, so it doesn’t mess with the macaroni): a slice of avocado, a spoonful of tomato sauce, a cube of mango. Or bridge the gap between the familiar and the unfamiliar—drizzle some of her standard cheese sauce on a floret of steamed broccoli or cauliflower, a small meatball, or a few flakes of fish (on a separate plate, so there’s no mingling with her precious pasta).

Try family style. Eating as a family comes with lots of benefits, long and short term. But here’s one you might not have thought of: Family-style eating may encourage your picky toddler to eat more adventurously (as in, “I’ll have what she’s having”). Pass around a bowl of pasta with veggies and pesto or a plate of teriyaki salmon and brown rice, and you may be surprised to see your tot reach for a taste. When you can’t sit down together for a full meal, try to have a healthy snack while your little one digs in—and don’t forget to share.

Hire a junior chef. Older toddlers love to pitch in, and studies show that kids who do some mealtime prep are more enthusiastic about trying the fruits (and veggies) of their labor. Start at the market, by letting your picky tot pick between pasta shapes, choose a tomato, plop green beans into a bag. And then it’s on to the kitchen—yes, the kitchen. While your first instinct may be to shoo your toddler from the kitchen (the stove’s too hot, the knives are sharp, and you just want a little peace when meal prepping), inviting her to “help” you instead can be just the (meal) ticket for a picky eater. So let your toddler sprinkle cheese onto the pasta, stir the pancake or muffin batter, toss the blueberries into the oatmeal, or pat the salad dry. Her role as junior chef may not open up a world of eating experiences right away, but chances are she’ll be more willing to try something she helped make.

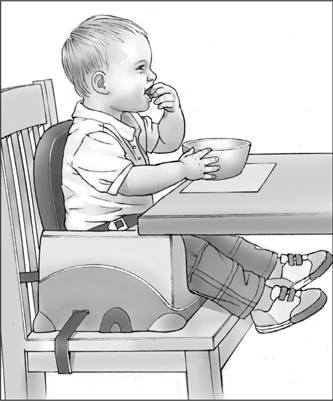

Take no captives. Sometimes it’s not the meal itself that a toddler finds objectionable, but the confinement (in a high chair, for instance). See page 117 for less-confining seating options. Allow the freedom of self-feeding, too, for best eating results.

Make the name part of the game. Just as you’d be more tempted to order “a mélange of baby spring greens tossed in a mustard vinaigrette” than a “house salad,” your toddler may be more tempted to eat egg salad if it’s called “egg sand” and scooped up with “shovel” crackers, a peanut-butter-and-banana sandwich if it’s called a “pb&b,” a fried egg if it’s sunk into the center of a piece of toast and called “egg in a hole,” a miniature meat loaf if it’s called a “meat muffin.” For other strategies for making food fun, see box, page 114.

Leave pressure off the menu. Skip the pushing, prodding, coaxing, bribing, and cajoling—ditch even those time-honored “here-comes-the-choo-choo-into-the-tunnel” games. Let your little one eat as much, or as little, as she’s hungry for—and when she’s had enough, let her call it quits. Letting her appetite call the shots will help her develop healthy attitudes about eating, instead of setting the table for future food issues. Plus, when was the last time putting pressure on your toddler convinced her to do something she didn’t want to do?

Let the picky pick, to a point. As long as there are only healthy options to choose from, let your picky eater at it. Encourage her to eat outside the box (of frozen waffles) and to try what everybody else is having, but don’t insist. On the other hand, make her stick with what she picks (you don’t want to fall into the short-order cook trap—if it’s grilled cheese she’s selected, it’s grilled cheese she eats). And when picking’s just not possible—you’re at a friend’s house, and it’s omelets for brunch—end of story. Let her know: “You can have the omelet and some bread, or you can leave the table and go play.” After all, in the real world, you don’t always get to pick.

Let the poky poke, to a point. Many toddlers are slow eaters, particularly once they’ve started feeding themselves. Each pea must be popped in the mouth individually, strands of spaghetti sucked up one at a time. So give your toddler all the time she needs to complete the meal, even if it means starting breakfast 10 minutes sooner so you can get to day care on time. When eating dissolves into playing, however (the peas are being plopped into the orange juice instead of popped into the mouth, the spaghetti strands are being strung from the high chair like garlands), end the meal promptly. Limiting distractions will help keep your toddler on task, so turn off the TV at mealtime, and if she wants to bring a toy to the table, let her know it’ll have to watch her eat.

Feed when hunger strikes. It may sound obvious, but kids who aren’t hungry at mealtime don’t eat well. Some toddlers get out of bed in the morning ravenous, ready to dive into their bowl of cereal; others need some time to wake up and work up an appetite. Some can wait for a late family dinner hour; others have long lost their appetites by the time everyone’s home and ready to eat. Try to tune in to your toddler’s individual hunger pattern, then set mealtimes a little before each hunger period. And once you’ve set the mealtimes, try to stick with them; for most toddlers, regular and predictable mealtimes, with food served in the same place at the same time, works best. Another obvious appetite saboteur: too many snacks, or snacks that are too filling or served up too close to a meal. Ditto too many filling drinks.

“My toddler won’t eat anything that resembles a vegetable, especially if it’s green. I know that’s age-appropriate, but how’s he supposed to get the nutrients he needs?”

It’s not easy being green—especially if that something green is sitting on a toddler’s plate. It’ll be pushed to the side, hurled across the room, or fed to the dog... but eaten? Not likely. That little-kid cliché holds true for most little ones, at least during the picky second year. And it’s not surprising. Many green vegetables have strong flavors that can easily offend timid taste buds. Some have challenging textures or smells. Some, all three. Fortunately, not all veggies are green, and none of them have cornered the market on a particular nutrient. Here’s how to get your toddler to eat his vegetables, or at least the nutritional equivalent of them:

Be a little sneaky (but not too sneaky). Vegetables don’t have to be recognizable to be nutritious, and it’s fine to sneak some into the foods your little one loves. Add chopped or pureed vegetables or tiny peas to the macaroni and cheese (cauliflower is especially hard to spot in an otherwise white dish). Toss little bits of cooked broccoli or red pepper into the spaghetti sauce. Stir a small amount of grated carrot into pancake or muffin batter, meatloaf, or burgers. Bake some pumpkin bread. Pour some V-8 (some kids love the taste). But don’t get in the habit of trying to disguise all the vegetables you serve—or try to serve—your toddler. First, because all that sneaking around will have to stop somewhere: Do you really want to be performing disappearing vegetable acts when your child’s in middle school? Second, because it’s not going to be effective forever (it won’t be long before your little one smartens up to vegetable deception). But most important, because the ultimate goal should be a child who chooses to eat well—who reaches willingly (maybe even happily) for that stalk of broccoli, that asparagus spear, that mushroom slice—not one who’s tricked into eating well.

Vary those veggies. So you keep offering up broccoli, and you keep getting turned down. Don’t give up—you never know when you’ll hit broccoli bingo—but do offer up vegetable variety: chunks of soft-cooked butternut or kabocha squash, beets, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, parsnips, bell peppers (in red, yellow, orange). And never assume that because your toddler has rejected one veggie he’ll turn down another. Here’s another assumption you should never make: that he won’t like a veggie or other food just because you don’t.

Sauce them up. Just because your toddler doesn’t like veggies straight up, it doesn’t mean he won’t like them sauced. Try cauliflower in a mild coconut curry sauce. Broccoli in a stir-fry. Feature veggies in stews and soups (minestrone is a toddler favorite, but you can also add extra minced carrot to chicken noodle). Dipping, because it’s interactive, elevates veggies of all kinds to fun finger food. And for those pint-size cheese lovers, melting a little shredded cheese on any veggie can turn it into a tempting treat.

Eat your vegetables. Toddlers model all kinds of behaviors, including those they spy at the dinner table. If you dive enthusiastically into that bowl of green beans and carrots or take seconds on the salad, your little one’s more likely to.

Grow your own. There’s no better way to get a little one interested in vegetables than to grow some together (talk about ownership!). Next best, visit those who do grow their own, at the farmer’s market or a produce stand. Out of season, or out of area? Visit the produce aisle, and enlist your toddler in produce selection, and later on, in produce prep.

Switch colors. Your toddler still isn’t going for the green? It’s by no means required eating. In fact, the very same nutrients found in green vegetables can also be found in those more toddler-friendly colors, orange and yellow (think carrots, sweet potatoes, winter squash). What’s more, fruit covers all those nutritional bases just as well as any vegetable, especially fruit that’s vibrant in color (mango, papaya, cantaloupe, apricots, peaches, and berries). Add fruit to yogurt, to cereal, to smoothies—it’s also yummy to dip with.

“All of a sudden, my daughter has started rejecting her favorite dishes. What gives?”

Is yesterday’s favorite food suddenly on today’s blacklist? That’s a toddler for you. Just when you think you’ve finally found a food you can count on your toddler eating, she stops eating it.

Sometimes it’s just trademark negativity or an effort to gain control (“You can’t make me eat my favorite food!”), sometimes it’s a whim, sometimes it’s a bout of teething or an oncoming cold, and sometimes it’s just boredom that turns a toddler off an old favorite food. Whatever the reason for rejection, keep these dos and don’ts in mind:

Don’t stress. Your toddler won’t starve—she’ll just eat something else. Healthy toddlers who aren’t pushed to eat always eat what they need. And making a big deal about the rejection only reinforces what she probably already senses: that the best way to push your buttons is to push away what’s put in front of her. Instead, keep your cool when she suddenly spurns her beloved waffle.

Do give it a break. Matter-of-factly take the rejected food away, and don’t serve it up—or bring it up—for at least a week, unless it’s asked for. In the meantime, offer nutritionally similar foods—if it’s frozen waffles that have gotten the cold shoulder, serve pancakes. If it’s yogurt, try cottage cheese. If it’s apples, go bananas. Even toddlers get bored with the same old foods, after all.

Do bring it back with a twist. When you return the rejected food to the menu, serve it with a different spin. Cereal for lunch instead of for breakfast. A pb&j rolled up and cut into pinwheels instead of standard squares (or for something completely different, try using a whole wheat tortilla in place of the expected bread—or banana instead of the jelly). Melon scooped into tiny balls instead of chunked. Chicken topped with tomato sauce and cheese instead of cut up into nuggets. Grilled cheese made with mozzarella instead of American (and maybe served with a marinara dip).

Don’t miss an opportunity. If you think about it, rejection of a favorite food is the perfect chance to offer up some new foods. So take the opportunity to add an item or two to your little one’s repertoire.

Do try it yourself. Toddlers are notoriously possessive. Helping yourself to that rejected yogurt or bowl of cereal may inspire your toddler to dig in.

Don’t write off rejected foods. What’s off the menu today may be back on tomorrow, so don’t give up (yet) on the six boxes of waffles you’ve stockpiled in the freezer. In fact, if the favorite food strike is being triggered by teething discomfort or a soon-to-appear cold, it may be back in favor once your little one’s back to her usual self.

“Our son won’t sit still for a meal. He tries to stand up, squirm, and twist in his high chair—and he usually wants to come out before he’s eaten very much.”

In his baby days, your little guy did much of his exploring via his mouth—making eating an exciting experience. As a toddler, he prefers to explore on foot—making eating an exasperating waste of time, at least from where he sits (and twists, and squirms). And yet, food breaks are necessary to fuel his other activities. To help him refuel in spite of himself: