1

Character

Flat, Zany, Grotesque: Caricature and the Politics of Character

Early-Victorian Caricature and Personhood

Caricature has always struggled to find aesthetic credibility due to its association with debased cultural modes like mass art, ephemerality, topicality, simplification, exaggeration, and comedy. In this chapter, however, I look to caricature as an important cultural and political site for the imagining of persons during Britain’s Reform era. The agitation for Reform legislation coincided with the moment when caricature first gained broader circulation in mass-printed periodicals, engravings, and comic sketch-books in the late 1820s and 1830s. While eighteenth-century prints were elaborate and expensive, early-Victorian illustrated magazines and newspapers sold caricatures for pennies apiece.1 I argue that caricatures—by artists like George Cruikshank, Robert Seymour, and Hablot “Phiz” Browne—presented an implicitly politicized version of character that differs from our usual sense of the nineteenth-century concept. Unlike the realist novel, with its psychologically deep characters, these ephemeral images undercut any classical stability of self, producing an idea of character that was comic, provisional, grotesque, and improper. Caricature’s characters emerged in the 1830s after the Reform Bill failed to lift up working-class people and fueled the populist sentiments that would swell the ranks of Chartism in the 1840s. Producing savagely comic assaults on authority, these images targeted “great men” and their acolytes, epitomizing a deflating version of character in which grotesque, deformed bodies incarnated harsh political truths.

There’s a particular logic to opening a book about nineteenth-century visual culture with the 1830s and its environs. It was in this decade that transforming technological developments enabled the first cheap illustrated magazines and affordable caricatures. And the Reform Act introduced an influential vision of democracy: it ushered in new aesthetic and political ideals that would become definitive across the century. The democratic ideals of Reform, however, differed from the political reality, which entailed massive inequality and disenfranchisement for most British people. Caricatures in the 1830s gave frenetic visual expression to the frustration inspired by these conditions.

Historians have designated the late eighteenth century as caricature’s Golden Age, celebrating the densely worked, lavish images by Rowlandson, Gillray, and Isaac Cruikshank.2 This chapter instead looks to the smaller, more accessible and inexpensive caricatures of the late 1820s and 1830s, cheap and ephemeral, epitomized by “the flying sheet” read by travelers on the new railway lines.3 Quick consumption defined the visual/verbal “sketches” and “scraps” appearing in new popular magazines and newspapers. These periodicals printed the earliest comics, whose name derives from the “Gallery of Comicalities” that appeared in sporting newspapers of the late 1820s. In The Art of Caricature (1981), Edward Lucie-Smith writes that caricature’s popularity emerged from the unique nature of print itself: “Print is, after all, a very special mode of communication. It speaks to us privately, as individuals, yet cheapness of material and rapidity of production make it available to almost everyone.”4 Unlike the more elite caricatures of the eighteenth century’s Golden Age, the new caricatures of the 1830s opened onto a very different chapter in the history of the medium, one geared toward a more populist and lower-middle-class ethos.

The chapter analyzes caricature as a specific aesthetic strategy, one that constructs character from the outside, from surface details, traits, movements, and behaviors, rather than by plumbing internal depths. The account invokes the etymological roots of “character,” which lie in notions of carving, or engraving, as conveyed by the Greek word for a stamping tool. Caricature invites us to think about character’s visual qualities, which are not typically foregrounded in literary discussions of a novelistic character whose focus is inherently linguistic. Thus John Frow’s Character and Person (2014) focuses especially on the rise of fictional character in the eighteenth century and “that impossible illusion of inwardness that gives novelistic characters their ‘peculiar affective force.’”5 Literary history has privileged the rise of the Romantic subject, starting in the late eighteenth century and culminating in Jane Austen’s novelistic realism or in William Wordsworth’s deep poetic self in nature.6 Yet many different kinds of character flourished in the nineteenth century, only some of which featured in the classic realist novel or Romantic poem. In seeing caricature as an art form in its own right, I eschew a negative comparison to character-as-inwardness, instead exploring a form of character defined by surfaces, one engaged in a performative grotesque, a satire of norms, and a comic exaggeration that valued visibility and, often, political critique.

Caricature has accrued negative connotations for its tendency to reduce the body to its most recognizable signs: identity becomes encapsulated in cartoonish, exaggerated externals.7 Popular racist stock types of the 1830s included the Jewish used-clothes seller and the newly freed Caribbean slave. The Victorian visual typing of peoples participated in a dark lineage, leading to eugenics, scientific racism, and violent genocidal attacks on those deemed “other.”8 Visual typing in caricature accompanied the mechanization of print: “stereotype” and “cliché” were both coined in the early nineteenth century to describe printing processes, suggesting the way that mass print itself created an idea of too-familiar, iterative characters.9 Yet while caricature participated in these developments, it also moved in an opposite direction, celebrating eccentric individualism, deviance, and the transgression of norms rendered in a grotesque style.10 These twin opposing strands also inhere in notions of character itself, which drives on the one hand toward essence and representativeness, and, on the other, toward distinctiveness and individuation.11 The chapter studies the 1830s as an especially fraught moment in the history of both caricature and character. The character sketch, a defining visual-verbal form of this moment, captured the instabilities: popular comic taxonomies limned the types of urban characters, even as character itself was destabilized by economic and industrial disruptions.

Caricatures of the 1830s dwelled especially on the new male professional types that hovered ambiguously between proletarianism and respectability, entertaining a new idea that social class was performative rather than organic and innate. Under these conditions, the lower-middle-class man emerged as a key protagonist of modernity. Numerous caricatures featured “the cockney,” the urban mischief-man whose subversive masculinity hovered at the borderlands of class, respectability, and propriety. These comic images combined often crude racism and misogyny with anti-authoritarian, carnivalesque humor. Cockney male figures expressed a wild, mock-violent energy that gave voice to some of the volatile frustration felt by working- and lower-middle-class men both before and after the Reform Bill of 1832. The cockney type was popularized by likely the single most influential visual-verbal item of the early-Victorian cultural world, Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1821), with its renowned illustrations by George and Robert Cruikshank. Life in London spawned two decades of popular culture obsessed with sports, roguishness, urban comedy, and the bachelor lifestyle. Egan’s ensuing sporting newspapers introduced the first Gallery of Comicalities in 1827, establishing the roots of modern-day comics. An important contributor to this raucous visual culture was the young Charles Dickens, whose early works emerged directly from extant caricature types and themes. In the sports-themed Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836–7), Dickens mocks the “great man” theory of character while celebrating the urban male rogue, Sam Weller. Dickens’s characters reappeared in pirated form across visual and print cultures of the 1830s, their comic male types resonating with audience desires and resentments. In the character dynamism of post-Reform London in the 1830s, grotesque, ingenious physicality gave expression to fundamental instabilities of social class and economic precarity.

Whereas the grand caricatures of the late eighteenth century satirized kings and politicians, early-Victorian caricatures featured ordinary everymen, carousing in pubs or in the streets—a seemingly safer and less political vision.12 Yet politics still inhered in these more humble depictions, even when they avoided explicit legislative matters. Political energies came through in depictions of plucky pickpockets, despicable fat men in power, and jovial celebrations of “Nobody,” a recurring caricature character. The political overtones, moreover, were complicated and at times unsavory. Early-Victorian caricature marketed itself to men: its imagery expressed the explosive energies of populism, taking the viewpoint of the aggrieved white male. Some of the images make for a discomfiting viewing experience today, with their cheerfully violent, racist, and misogynist overtones. These comic assaults on authority and celebrations of the little guy were consumed across classes, appealing as much to repressed bourgeois gentlemen as they did to disgruntled working-class laborers. The “energy” of caricature was both political and visual: character was rendered in lines that were wobbly, weird, distorted, and unfinished, deliberately avoiding polish and refinement. Caricatures reflected the way that older forms of identity were being destabilized by new labor conditions in the urban landscape.

My analysis opens onto some larger conclusions about alternative models of personhood depicted in a minor aesthetic mode: unlike the art forms of bourgeois individualism, dependent on evocations of depth and roundedness, caricature used satire and aggressive mockery to raise questions about who is allowed to be gifted with personhood, and when. The caricature account of character in the 1830s ultimately pointed toward a new idea of social identity, one unfixed from an older, hermetic class system, in which the (male) self emerged as performative, flexible, and supremely adaptable.

The Political Grotesque: Bodies of the People

Caricature’s signature style is the grotesque. Philip Thomson notes how grotesquerie works by juxtaposing disparate elements, especially the comic with the horrific—as in Jonathan Swift’s plan, in A Modest Proposal, to solve Ireland’s poverty problem by cannibalizing babies. The resulting defamiliarization, Thomson suggests, produces effects of both aggression and alienation: by pushing viewers beyond their expectations, the grotesque results in feelings of disturbance and even disgust.13 Caricature’s linguistic origins themselves encode an idea of violence, as the Italian verb caricare signifies “to load or charge, as a firearm”—implying that an exaggerated, comic drawing might serve as a kind of weaponry.14 These belligerent aspects made caricature a fitting medium to express political and social forces, scripted across grotesque bodies.15

This charged mode of comic drawing gave expression to the political ferment roiling the 1830s, an especially unstable and dynamic phase in the modernizing transformation of Britain. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened in 1830, and by 1840 nearly 1,500 miles of track had been built across the United Kingdom. On the one hand, this was a moment of progressive reforms—a Whig government ushered in the Reform Act of 1832, enfranchising more of the male middle classes; the Factory Act of 1833 limited child labor, while slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1833. On the other hand, though, working-class unrest escalated during the decade, responding to the massive capitalization of industry and factory work. The New Poor Law of 1834 forced those receiving charitable assistance into workhouses, a development vilified in progressive quarters. In 1838, activists drew up the People’s Charter demanding universal suffrage, inaugurating the first organized working-class labor movement in history.16 The instability in Britain’s political, social, and economic life during this decade found its expression in caricatures whose comic violence responded to the government’s inability to effect meaningful social change for the country’s working and lower-middle classes.

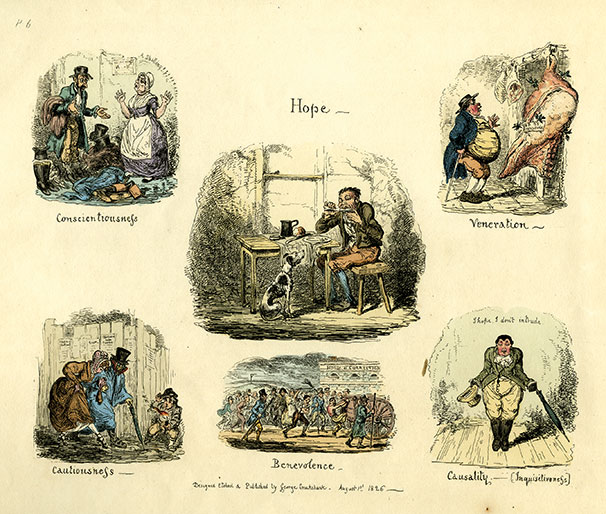

These political energies animate many of the images produced by caricaturist George Cruikshank. He had started his career in the 1810s with expensive, elaborate, and often scurrilous caricatures appearing in single broadsheet format. By the mid-1820s, however, he had shifted his output to suit the new mass market, producing more affordable and simpler images, cuts in weekly newspapers or “scraps” in cheap sketch-books and everyday books. A grotesque iconography of politicized bodies appears in Cruikshank’s sketch-book, Phrenological Illustrations (1826). Each page contains five to seven different small cartoons illustrating different phrenological Faculties (Fig. 1.1). These “scraps” find humor in subversive, deflating puns and distorted, misshapen bodies. In “Hope,” a thin man in a destitute interior gnaws on a bone while a thin dog looks on, hopefully. In “Veneration,” a grotesquely fat man in an alderman’s hat salivates in worshipful contemplation of a giant beef haunch. Many of the scenes have explicitly urban settings and referents—“Covetiveness” shows a street urchin lifting a handkerchief out of a clueless gentleman’s pocket, while “Language” shows brawny working-class women arguing on a dock amid a crowd of sailors. Phrenology’s scientific confidence gets punctured by the rebus-like format of the cartoons, whose puns deconstruct the totality of each Faculty. Meanwhile, the familiar types of the fat politician and the underfed working-class man speak to the broader political concerns of the 1830s, attacking those in power while offering a mocking, ambivalent sympathy to those in the underclass.17 Cruikshank’s scraps offer us a clue as to how to read the politics of 1830s caricatures. Even when politicians or Reform are not explicitly mentioned—as in an image of a pickpocket stealing a gentleman’s handkerchief—these images still invoke certain stark political realities. Both the desperately poor and the venally wealthy appear in grotesque bodies, implying that modern economic conditions are deforming of character both high and low.

Fig. 1.1 George Cruikshank, “Hope.” Phrenological Illustrations, 1826. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

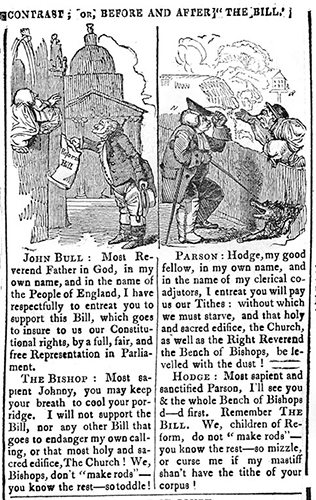

Some caricatures expressed a political grotesque more directly. An 1832 image from the “Gallery of Comicalities,” appearing in Bell’s Life in London, mocks the Church’s refusal to support the Reform Bill. In “Contrast; Or, Before and After ‘the Bill’” (Fig. 1.2), the caricature juxtaposes two panes. First, a Bishop rejects John Bull’s appeal for support of the Bill: “We, bishops, don’t ‘make rods,’—you know the rest—so toddle!” In the second pane, the positions are reversed and now a parson petitions a common man for tithes. “Hodge” replies:

I’ll see you & the whole Bench of Bishops d—d first. Remember THE BILL. We, children of Reform, do not ‘make rods’—you know the rest—so mizzle, or curse me if my mastiff shan’t have the tithe of your corpus!

Fig. 1.2 “Contrast; or, Before and After ‘the Bill.’” Detail from annual collection of the year’s “Gallery of Comicalities.” Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 1832. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

An excited dog in the corner gapes with toothy jaws, awaiting his opportunity to bite the parson. The cartoon presents a typically intense condensation of punning and visual play. The Bishop, big-bodied and puffy-faced, manifests the gross embodiment of privilege, his religious “corpus” become “corps.” The church tithe is literalized into the humiliating bite of a dog, whose eager jaws threaten violent yet humorous retribution. The dog in this cartoon is not incidental; animals appear frequently in early-Victorian caricatures, signifying a cynical materialism. While the Church is supposed to be a holy and disinterested institution, its demand for tithes here amounts to nothing more than the avaricious bite of a hungry dog. John Bull’s body is also stout and clownish: everyman characters in caricature are often rendered grotesquely, even while they appear in sympathetic or admirable guises. There are no true heroes in this carnivalesque world. The everyman is as malformed as anyone else, implying a more generalized theory of humanity as animalistic, self-serving, and absurd. Still, though, the political grotesque expresses moral opinions by featuring a reliable cast of villains who fatten themselves on the land while common people suffer or starve.

Caricature’s political grotesque resonates with the carnivalesque rituals analyzed by Mikhail Bakhtin in Rabelais and His World (1968). Bakhtin looks to Renaissance folk festivals in which peasants dressed up in outrageous, bawdy costumes, creating an atmosphere of transgressive equality within a radically unequal and divided society. He argues that the distinctive style of this riotous carnival is the grotesque. He contrasts the classical body—pure, bounded, idealized, isolated—with the grotesque body, which is fleshy, multiple, protuberant, mobile. For Bakhtin, the classical body serves as the ideological foundation of the bourgeois self—“the private, egotistic ‘economic man,’”—whereas the grotesque body signifies a teeming “all-people’s character,” “the collective ancestral body of all the people.”18 Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (1986), elaborate on Bakhtin’s theory, noting how the grotesque body

has its discursive norms too: impurity (both in the sense of dirt and mixed categories), heterogeneity, masking, protuberant distension, disproportion, exorbitancy, clamour, decentred or eccentric arrangements, a focus upon gaps, orifices and symbolic filth (what Mary Douglas calls “matter out of place”), physical needs and pleasures of the ‘lower bodily stratum,’ materiality and parody.

Stallybrass and White contrast these qualities with those of the classical body, defined by regimentation, control, normalization and centering.19 For Bakhtin, as for Stallybrass and White, the grotesque is the quintessential style of the people, channeling ancient folk traditions that challenge social hierarchies and the status quo.

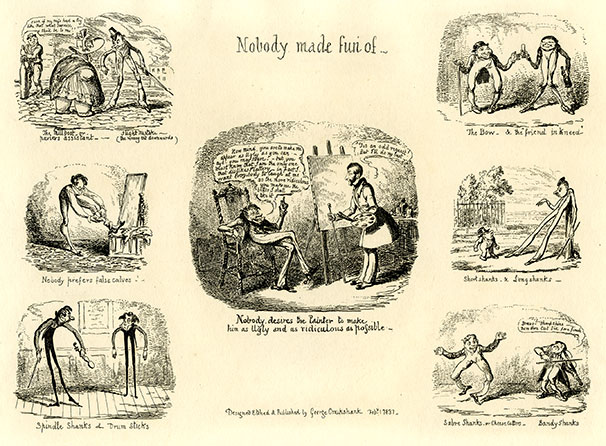

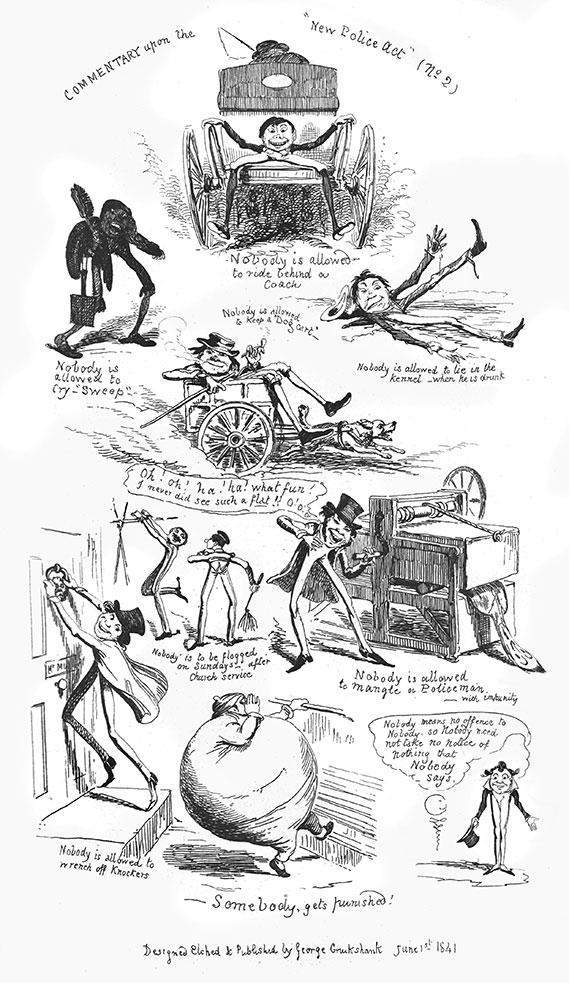

A grotesque body that incarnated populist 1830s politics was “Nobody,” a stock character-type with medieval roots.20 Nobody sported a cheerful head atop elongated legs, torso weirdly missing. He appeared in caricatures across Europe as a mock-hero, long-suffering, foolish, innocent, often a scapegoat. In Britain he was also aligned with “Everybody” (cf. C. J. Grant, Every Body’s Album & Caricature Magazine, 1834–5); both of these character types embodied the humble man with no power or resources. Nobody’s antagonist was “Somebody,” all stomach and no legs, an arrogant persecutor of the lowly. It will be immediately apparent how these figures encoded a nascent class politics, as the human body was politicized in its parts. Legs (“shanks”) were laboring, supporting, while torsos or stomachs were controlling, consuming. George Cruikshank published a sequence of scraps in 1831, “Nobody Made Fun Of,” gently mocking Nobodies with captions such as “Spindle Shanks & Drum Sticks,” or “The Friend in Kneed” (Fig. 1.3). The legs of these figures are absurdly long, with their heads propped surreally on top. While Nobody belongs to a longstanding folk tradition, Cruikshank recasts him within a new urban scene: these male figures clearly occupy the Dickensian milieu, with their lower-middle-class costumes and behaviors—playing music on a fiddle, dancing, toasting drinks in a pub. In the central scrap Nobody sits for his portrait; an ornamented chair rises ridiculously above his low, torso-less body, as the cartoon mocks his pretensions to respectability. Cruikshank emphasizes Nobody’s antinomian politics in a series of 1841 scraps commenting on the New Police Acts (Fig. 1.4). Each scrap, captioned with the phrase “Nobody is allowed to …,” depicts Nobody getting up to childlike mischief, from spinning a hoop to playing Punch. The phrasing playfully imagines an upside-down world in which laws grant Nobody more freedoms—rather than the grim reality, in which new police laws will inevitably coerce and constrain. In this scrap fantasy world, “Somebody gets punished”—a grotesque, all-stomach Somebody—while, triumphantly, “Nobody is allowed to mangle a Policeman—with impunity.” The scrap depicts Nobody joyously running a flattened policeman through a laundry press.21

Fig. 1.3 George Cruikshank, “Nobody Made Fun Of.” Scraps and Sketches, 1831. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 1.4 George Cruikshank, “Commentary on the ‘New Police Act’ (No. 2).” George Cruikshank’s Omnibus, 1841. Courtesy University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center.

Populist characters like Nobody incarnate a Bakhtinian grotesque. They embody a dispersed identity, multiple and many-bodied, as opposed to a more elite, bourgeois individualism. These values in caricature reflect other satirical, early-Victorian attacks on the Great Man theory of character and history, as seen in, for instance, the subtitle to Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847–8), a “novel without a hero.” Caricature’s long-legged Nobody functions as part of a broader class critique of character, implicitly questioning who is allowed to be individuated, named, and gifted with a rounded identity.

Punch: The London Charivari

Carnivalesque caricature in the 1830s described a moment of transition, as ancient folk customs were being repurposed for new, modern rituals. Caricature culture often meditated on the ongoing shift from the country to the city, from folk festivals to city street parades, and from village identity to working-class urban identity. This transition is reflected in the title of the nineteenth century’s most famous caricature magazine, Punch, or the London Charivari (founded in 1841, price 3d). The magazine in its earliest incarnations wedded folk tradition to urban modernity, adopting a puppet as its mascot—another grotesque comic figure whose flattened personhood served to satirize cultural and political norms.

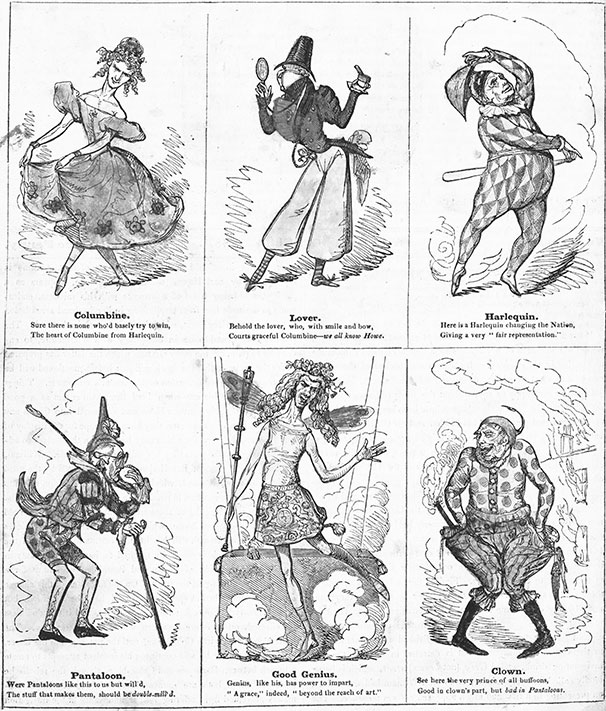

“Punch” was a belligerent glove puppet with roots in the Italian commedia dell’arte (Pulcinello) who appeared in eighteenth-century rural fairs with his put-upon wife, Judy. Around 1785 Punch began to perform regularly in London street shows, and in 1841 he became the emcee and “house personality” of the successful caricature magazine.22 The figure of “Mr. Punch” thus traced an overlapping arc from folk fair favorite to city street performer to print culture icon. All three of these aspects are visible in the title page of Punch’s first number, July 17, 1841, depicting an urban audience gathered before a puppet show and highlighting the folk puppet tradition (Fig. 1.5). (Among the crowd in the foreground, a child pickpocket rummages in a gentleman’s pocket, rehearsing a popular caricature theme.) Early numbers of Punch stressed Mr. Punch’s puppet qualities, exaggerating his hook-nosed features and hunchbacked shape—in fact, his deformed puppet body often appeared to be all legs and no torso, a version of the old folk figure of Nobody (Fig. 1.6).23 The early caricature version of Punch was, like his puppet-show forebear, pugilistic, combative, an outsider and commentator beholden to no one, a champion of working-class politics against “Somebodies.” This print version echoed the contents of the original London street puppet show: an 1828 transcription of the show depicts Punch beating his dog and his child; beating and then killing his wife, Judy; also killing the doctor, the clown Scaramouch, and the hangman Jack Ketch. The show concludes with Punch’s triumphant murder of the devil.24 Comic violence takes on a political edge as the riotous puppet shatters the forces of constraint, order, and governmentality—an energy reflected in Punch’s early incarnations as a radical humor magazine in the 1840s.

Fig. 1.5 Title page of Punch’s first number. July 17, 1841. Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo.

Fig. 1.6 “Punch’s Information for the People—No. 2.” Punch, August 14, 1841. Mr. Punch resembles the torso-less Nobody.

A carnivalesque, country–city humor was also signaled by the magazine’s noteworthy subtitle, “the London Charivari.” This subtitle was taken from the influential French caricature magazine Le Charivari, which had been publishing the political satires of Daumier and Grandville since 1832.25 Both the French and English magazine titles alluded to the folk practice of “charivari,” also known as “shivaree” or “rough music.” Like the folk festivals studied by Bakhtin, charivari similarly involved an upside-down populist disruption—in this case, villagers banging kettles and pans and dressing up in mocking costumes in order to punish disruptive members of the community, meting out a form of popular justice. Charivari often featured a procession or costumed pageant, what E. P. Thompson describes as a form of “street theatre” in mock-imitation of the official ceremonies of church and state.26 When Punch names itself “the London charivari,” it announces its intention to hold city authorities to account with a kind of populist, self-anointed, comic noise-making.

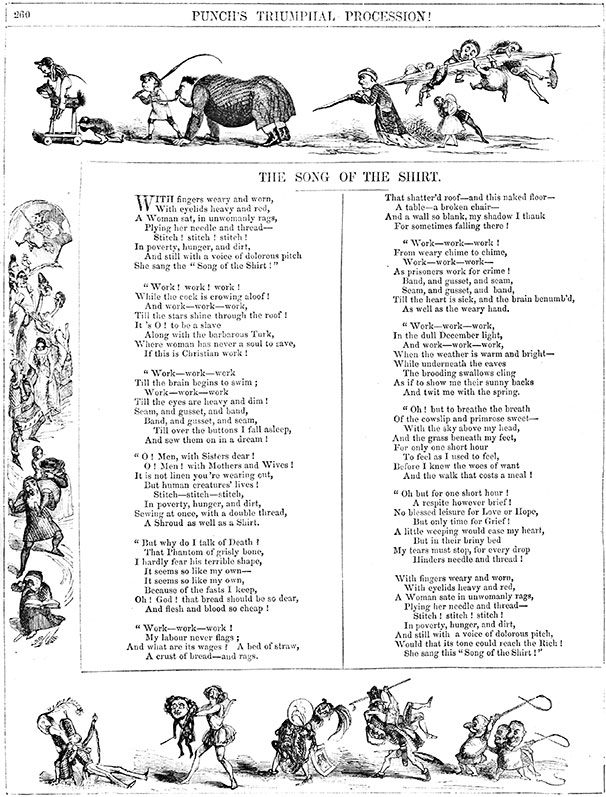

Processional “rough music” is a visual iconography that recurs throughout early Punch numbers, as the puppet Punch leads a grotesque menagerie of weird, merry creatures in a parade around the page’s margins. In fact, the urban charivari transforms our understanding of one of the magazine’s most resonant early pieces, its publication of Thomas Hood’s 1843 poem “The Song of the Shirt.” While Hood has been canonized today as a working-class poet writing on dark and serious themes, he was known during his own lifetime as a writer of politically tinged comedy. This fact explains why his famous protest lyric first appeared in a Victorian humor magazine. The seamstress’s dolorous lament mourns the deadening effects of her “Work! Work! Work!” and epitomizes the fiery, radical politics of Punch’s early years. “Stitch—stitch—stitch,/In poverty, hunger, and dirt,/Sewing at once, with a double thread,/A Shroud as well as a Shirt.”27 Yet for all of the poem’s dismal subject matter, its margins swarm with a pageant of grotesque comic characters, labeled “Punch’s Triumphal Procession!” (Fig. 1.7). The puppet Punch leads a fantastical pageant of both humans and animals, many of them clothed in circus or jester costumes, offering an array of bizarre bodily features and odd distortions of scale. None of these characters is a seamstress, despite the female figure’s popularity at the time. The figures are not named, delineated characters, but weird, flat personages; some of them oscillate between hook-nosed puppet and human character. The poem in its printed, visual context presents a grotesque, mocking aspect, as the seamstress’s repetitive labor and grim dehumanization are framed by a gleeful gallows humor. The charivari parades of early Punch numbers reflect the magazine’s transitional form, bringing a premodern village spectacle into the abstracted print culture of urban modernity.

Fig. 1.7 Thomas Hood, “The Song of the Shirt.” Punch, December 16, 1843.

The antinomian qualities of Mr. Punch—along with his fellow Nobodies and caricature everymen—invite approbation of the kind expressed by Bakhtin, Stallybrass, and White. A grotesque aesthetic “of the people” seems satisfyingly anti-hierarchical and egalitarian. Yet early-Victorian caricature reflected a complicated politics true to the prejudices of its moment. E. P. Thompson sounds a note of caution: even while the charivari ritual did constitute an unalienated, community-based form of popular justice, it also entailed more disturbing, violent aspects, enforcing social norms upon community members who differed or strayed. In particular, charivari was often performed by young men to govern or scapegoat village women who deviated from patriarchal marriage norms, whether by dominating over their husbands in arguments, committing adultery, or remarrying as widows.28 Just because the law “belongs to the people,” Thompson warns, “it is not thereby made necessarily more ‘nice’ and tolerant, more cosy and folksy. It is only as nice and as tolerant as the prejudices and norms of the folk allow.”29 Charivari’s legacies thus range from the mild—stringing a newlywed car bumper with pots and pans—to the malevolent, in the folk-justice spectacles of American lynchings and Ku Klux Klan parades.30 Film scholar Duncan Reekie similarly warns scholars not to “mythologise the utopian power of popular culture without acknowledging the history of popular racism, sectarianism, misogyny, homophobia, mob violence and persecution which also lies in the carnival tradition.”31 A complicated politics characterizes 1830s caricature, with its working-class sympathies and prejudices, its carnivalesque attacks on authority, especially political authority, its jingoism and masculinism, and its barely submerged aggression, grotesquerie, and violence.

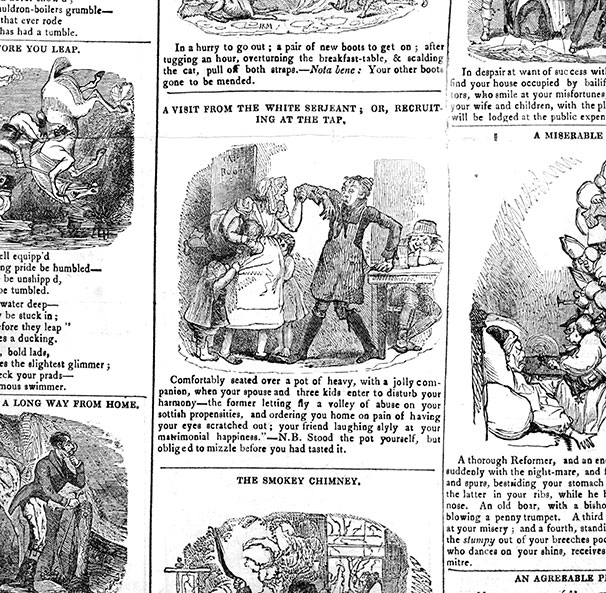

These dynamics define the humor of the “Gallery of Comicalities,” the origin of modern-day comics, which first appeared in the newspaper Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle in 1827. Amid four closely typed pages of text, the Gallery of Comicalities appeared in a box on the front page in the upper-right corner, reproducing a picture with a funny caption and an accompanying poem. These early cartoons lionized the everyman’s fight against Conservative politicians, the Church, and scientific authority—even while they featured numerous domestic scenes mocking the shrewish wife and the henpecked husband. Despite women’s relative powerlessness in the early nineteenth century, they often appeared in caricatures as figures for the straitlaced norms of civilization, demanding that their husbands return home from the pub or the street. In one cartoon from 1832, a wizened harridan yanks her husband out of the pub, their three children clinging to her skirts (Fig. 1.8). The caption describes how “you” are seated over a pot of ale with a friend when “your spouse” unleashes

a volley of abuse on your sottish propensities, and ordering you home on pain of having your eyes scratched out; your friend laughing slyly at your matrimonial happiness.—N.B. Stood the pot yourself, but obliged to mizzle before you had tasted it.

Fig. 1.8 “A Visit from the White Serjeant.” Detail from annual collection of the year’s “Gallery of Comicalities.” Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 1832. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

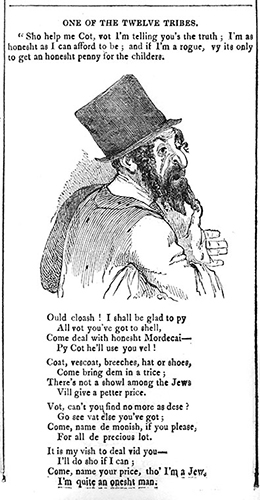

The cartoon elevates the homosocial bond with the male friend over the tedious obligation to the wife and the domestic sphere. The misogyny of these cartoons also accompanied a broader rigidity of type, one which targeted women and scapegoated racial types such as Jews, Afro-Britons, and the Irish. “The Portfolio of Lavater the Second,” offering a comic taxonomy of urban types, features a grotesque Jewish clothes-seller (Fig. 1.9), who announces in the accompanying poem, “Come deal with honesht Mordecai--/ Py Got [By God] he’ll use you vel!” The image limns the stereotypical Jewish male type, with exaggerated nose, unkempt hair, and battered hat. Working-class and lower-middle-class visual culture in the 1830s proposed an anti-authoritarianism that often bristled with racist and masculinist overtones.

Fig. 1.9 “One of the Twelve Tribes.” Detail from Portfolio of Lavater the Second. Annual collection of the year’s “Gallery of Comicalities.” Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 1832. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The caricatures in Bell’s Life shared a rebellious, defiant attitude with those in the early numbers of Punch. But the latter publication by mid-century had transitioned away from working-class culture, arriving at its more familiar incarnation as a “Whiggish,” middle-class organ. This transition was tracked by the cartoon puppet icon himself: whereas the early Mr. Punch was a folk anti-hero transplanted into an urban context, still very much a puppet defined by unrestrained violence and hostility to all authority, the character eventually developed into a more protean impresario, satirical, yet gentlemanly.32 His hunchback became less pronounced, his costumes more respectable and less clown-like.33 Mr. Punch’s transformation mirrored the magazine’s shift toward an increasingly bourgeois outlook, matched by a visual style that was less grotesque and more polished, with more volumetric, realistic figures. These visual changes throw into relief caricature’s grotesque style, whose countercultural attitude and politics were responding to the instabilities of the 1830s moment.

Blood Sports: Urban Character and Cockney Masculinity

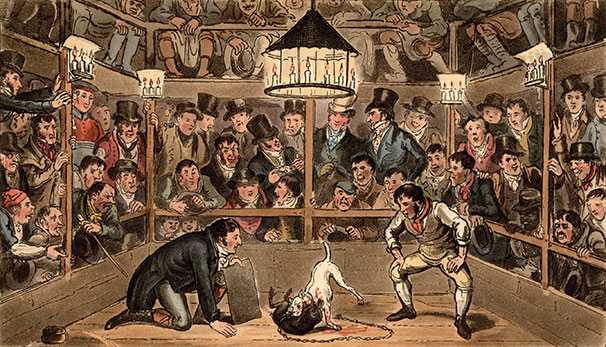

Early-Victorian caricature obsessively portrayed the figure of the cockney, a roguish, fiercely externalized, and mobile male character whose transgressions defied heteronormative family values and a politics of respectability. The cockney was a provincial Londoner whose naïve yet pretentious city-slicker ways invited both identification and mockery. This cheeky, countercultural urban character rambled around town and country, getting into scrapes and embarrassing accidents. The most influential visual prototype for the rogue London adventurer appeared in Pierce Egan’s 1821 Life in London, featuring the antics of the aristocratic rakes Tom and Jerry. Illustrations by George and Robert Cruikshank depicted these “flash” characters wandering through London, flitting from elegant salons to London’s sleazier destinations, including dog-fighting pits, gin-shops, and debtors’ prisons. While the portrayal of urban rambles was not itself original, Life in London was novel for its emphasis on visuality, making urban experience into a spectacle. The book’s tremendously popular illustrations also appeared on the cusp of technological transformations, allowing for a long cockney reach in popular visual-verbal culture into the 1830s.

Life in London insistently externalizes character as a visual mode. The book obsesses over the theme of character, whose advantages are praised on almost every page: “ONLY in London are the finishing touches of character to be obtained.”34 Yet unlike the realist novel, where characters are transformed by life-changing obstacles, Life in London features protagonists who don’t change at all over the course of the book. Tom and Jerry are young men of fashion who attain character by interacting with the city’s diverse others, forming the outrageous (male) self as both unique and superficial. Reaping character is a quintessentially visual process, the result of “SEEING LIFE” via the city excursion, itself a kind of witnessing or survey (52). In Cruikshank’s illustration of Tom and Jerry gambling at the dog-fighting pit (Fig. 1.10), grotesque faces of every social class mingle together in a jeering, teeming male humanity. Characters present diverse hats and costumes, each face registering its own distinct response to the violent spectacle. This scene, the letterpress tells us, offers “a fine opportunity of witnessing the difference of the human character” (259). Where character in the realist novel depends on a personal, deeply felt, empathetic bildung—one that often aligns a protagonist’s geographical movement with personal development—Life in London proposes a different currency, awarding character through accumulating views of different entertaining persons and scenes.35

Fig. 1.10 George Cruikshank, “Tom & Jerry Sporting their Blunt on the Phenomenon Monkey, Jacco Macacco, at the Westminster Pit.” Pierce Egan, Life in London, 1821. World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

Although the protagonists of Life in London were aristocrats, the book and its pictures extended a stunningly influential reach across the popular, visual, theatrical, and print cultures of the 1820s and 1830s. This fact is unexpected, given Egan’s politics: his Tory leanings express themselves in scenes of privileged men using their cosmopolitan powers to access the city’s most forbidding corners, from elite drawing-rooms to dangerous slums. Egan dedicated the book to George IV, celebrating a “Regency manhood in which the poor featured merely as a comic diversion,” as John Marriott concludes.36 Nevertheless, Life in London captivated audiences across classes, in part owing to its subversive scenes of social mixing. In one chapter, the protagonists travel between “Almack’s” and “All-Max,” such that the high-flown dance club deliberately mirrors the downscale East-End dive. The punning reflection implies a radical equality between high life and low. Life in London originally sold for 21 shillings, a price well beyond the means of most working-class people.37 But the material reached a much wider audience through W. T. Moncrieff’s smash 1821 melodrama, advertised as a “Classic, Comic, Operatic, Didactic, Aristophanic, Localic, Analytic, Panoramic, Camera-Obscura-ic, Extravaganza Burletta of Fun, Frolic, Fashion, and Flash in three acts.”38 Moncrieff explained in 1825 how he had created the melodrama by taking “the matchless series of [Cruikshank] plates” and putting “them into dramatic motion, running a connecting story through the whole.”39 Moving pictures animated the book into popular theater; the melodrama’s subtitle captured many of the mass visual spectacles and mock-infotainments of the 1820s. Life in London’s radical inclusiveness allowed it to spawn imitations popular with working-class and lower-middle-class audiences in the following two decades. The book’s flat yet vivid idea of character also coincided with the “flash” ambiguity of a mobile, rogue, urban masculinity, a compelling cross-class ideal that would become aligned with populist politics in the 1830s.

Masculinity itself functioned as a glue or connector across classes in early-Victorian visual culture, especially in uniting different identities under the umbrella of “sports.” Life itself is a kind of “sport” or “chase” for the merry wanderers of Life in London, a bawdy-tinged metaphor that speaks to Egan’s own background as a sports journalist in London.40 The author of Boxiana (first volume published in 1813) was known to patronize socially mixed sporting and drinking clubs, where he moved among pugilists, gamblers, and aristocrats, including the future George IV. John Marriott describes these clubs as “the vestiges of a pre-industrial culture of blood sports shared by plebian and upper-class [male] interests” before the advent of nineteenth-century “social segregation” and “rational recreation.”41 Blood sports were a pre-industrial survival, but they also loomed surprisingly large in the early-Victorian cultural world. The sports obsession of caricatures shows how older sporting practices were being reappropriated within industrial modernity, creating leisure enclaves for men of diverse identities and affiliations.

Alliances between men of different classes under a sporting motif also defined the identity of the cockney. Gregory Dart argues that the cockney character was crucial to metropolitan Romantic culture, emerging as a response to changes in urban life and labor. Dart explores the complicated political calculus that made Egan’s Life in London the template for what he calls a “Tory cockney fantasy”: even while the book was focused around aristocratic men, it presented a fantastical vision of “freedom and mobility” that potentially transcended the bounds of social class.42 For Dart, Egan’s city offered the glimmering hope of an egalitarian and classless cockney identity, one that spoke especially to a new class of male urban professionals, a lower-middle-class group consisting of shopkeepers, small businessmen, and white-collar apprentices, clerks, and assistants—“the social amphibians of their age,” Dart calls them, hovering uneasily between plebian and respectable culture (113). The Reform Act of 1832 heightened the sense of vagueness surrounding this social class, as it granted voting rights to men occupying property worth £10 or more—including some, but excluding others. (After the Act, the formerly disenfranchised Charles Dickens was able to start voting in 1834, when he took chambers in Holborn, London, at an annual rent of £35.)43 Ultimately, the Reform Bill failed to enfranchise or empower working-class men and most lower-middle-class men, a failure that expressed itself in the violent comic energies of caricatures expressing a populist sentiment.

Bonds between men of different classes were also forged by a shared misogyny. Life in London’s aristocratic libertine culture overlapped with a new misogyny among working men whose lives were being transformed by industrialization, as described by Anna Clark in The Struggle for the Breeches (1995). Clark writes of how male artisans, disrupted by new industrial practices and no longer masters of their own workshops, created “trade solidarity through a bachelor journeyman culture of drinking rituals and combinations.” This “bachelor orientation could easily be warped into misogyny and violence against women, directed both against rival female workers and against wives who complained of time and money spent with workmates in the pub.”44 The cockney figure, rambling through London or stumbling through hunting mishaps in the country, put a comic face on what were actually profound and at times disturbing changes in the British class structure. As Dart notes, “cockneyism … was never the preserve of a specific rank or class” (8). Its fashionable, “flash” male rogues, whether cheeky aristocrats or (as I’ll soon discuss) subversive servants, all opposed the respectable values of heteronormative marriage and family. These figures embodied a modish, counterculture masculine identity that traveled across various kinds of mass visual culture. While Dart hails cockneyism for its optimistic and even utopian overtones, his high-culture canon omits caricatures and sporting sketches, which add a darker note.45 Caricature’s violent comic energy emanated from the political failures and frustrations of the 1830s, rather than any futuristic possibilities. Its populism gave explosive voice to a sense of disempowerment and a lack of faith in society’s institutions.

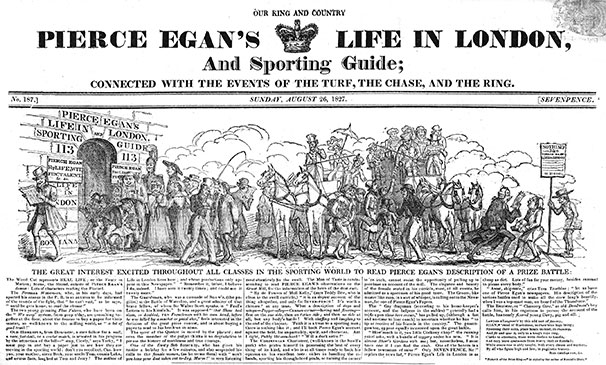

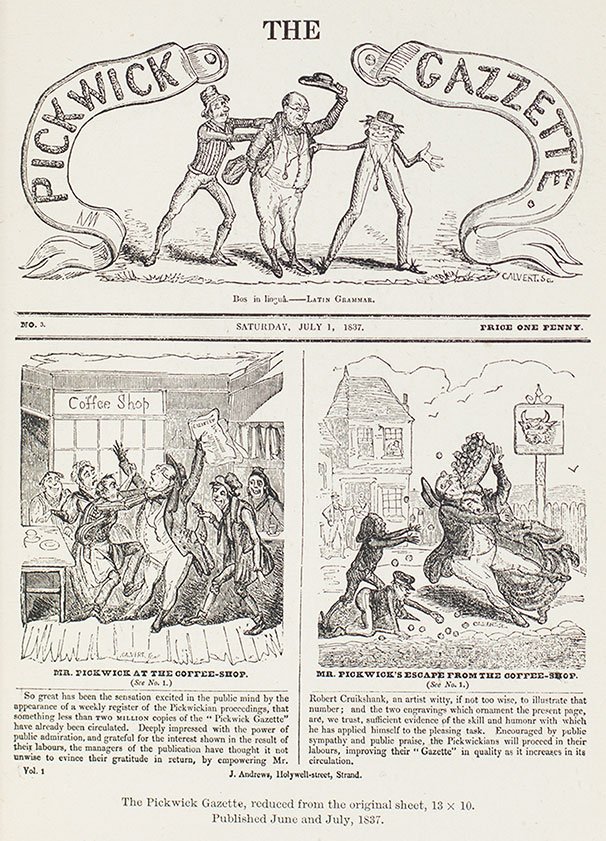

This analysis explains why the male-oriented sporting theme was so predominant in print and visual culture of the 1820s and 1830s, leading directly into the earliest caricature newspapers. In fact, one can trace a stunning line of influence from Egan’s Life in London to a wide array of pop-culture phenomena in the following decades. Egan parlayed the success of the book (and melodrama) into a weekly Sunday sporting newspaper, Pierce Egan’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (1824, price 8½d, reduced to 7d in 1827). The paper’s subtitle, “Connected with the Events of the Turf, the Chase, and the Ring,” situated the reader firmly in the world of masculine sporting pursuits.46 Egan’s newspaper was imitated, and in 1827 absorbed, by Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (1822, price 7d, reduced to 5d in 1835), whose circulation numbers ranged from 16,000 to as many as 22,000 copies per week, consumed by “the poorest classes.”47 It was Bell’s Life in London that created the Gallery of Comicalities in 1827, seeing circulation numbers shoot up with the insertion of a comic picture into the newspaper’s centerfold, a key origin for the earliest comics. Bell’s Life was also a publisher of twelve of Charles Dickens’s early sketches in 1835 and 1836, later collected into Sketches by Boz: not coincidentally, these sketches adopted the rogue-in-the-city sensibility typical of the sporting caricature newspaper. George Cruikshank, an original illustrator of Life in London, also became a key figure in Bell’s Life, since the first images in the Gallery of Comicalities pirated and reprinted Cruikshank’s scrap cartoons. After Cruikshank complained about the pirating, Bell’s went on to commission caricatures from Cruikshank’s rivals, including Robert Seymour and John Leech. These were the seeds of Seymour’s cockney sporting sketches, which would eventually serve as the template for Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers—itself, as I’ll explore, an extravaganza of cockney sporting humor. John Leech would go on to work as one of the major illustrators for Punch magazine, whose iconic puppet maestro excelled in pugilism. These seemingly disparate print and visual cultures were tied together by a sporting theme, targeting men with an inclusive fantasy identity based in bachelor adventures in the city.

The transmutation of Egan’s Life in London from aristocratic rambles into lower-middle-class misadventures—from elite culture to pop culture—is epitomized by Charles Dickens’s comic cockney sketch “Making a Night of It,” which was published in Bell’s Life in 1835. The sketch reiterates the story of Life in London, as two rowdy young men decide to go out on the town. Unlike Tom and Jerry, however, the two protagonists—“Potter and Smithers”—are not wealthy gentlemen but city clerks. “Their incomes were limited, but their friendship was unbounded.”48 After a wild and drunken night, the two men awake in jail, accused of several assaults and deeply in debt. The fantasy proposed by Life in London, of limitless wandering and adventures, here turns nightmarish, as the clerks are too poor to sustain their boozy exploits, which have turned criminal. Never again, Boz tells us, will the two be “detected in ‘making a night of it.’” Fittingly, the 1835 cartoon that appeared in the Bell’s Gallery of Comicalities in the same issue as Dickens’s sketch depicts “Grouse Hunting; or Cockneys Out of Their Element,” in which a group of bedraggled city men and their exhausted dogs complain about the ardors of country life. When a reviewer in 1836 called Dickens’s Sketches by Boz a “caricature of cockney life,” the critic was describing Dickens’s imbrication within a larger, popular urban visual-verbal culture.49 (I develop this point below in a discussion of The Pickwick Papers.) The shift from Tom and Jerry to Potter and Smithers, or to the cockney out of his element, describes in miniature the rise of “the mass” as both subject and audience in the 1830s, a shift framing the lower-middle class as the subjects of modernity.

David Kunzle suggests that Egan’s and Bell’s newspapers, with their canny innovations in comic illustrations, inaugurated the era of “the mass press.”50 His claim might be controversial among newspaper historians, who usually choose a later date because stamp taxes in the 1820s depressed newspaper circulation.51 When the Whig government reduced the stamp duty from 4d to 1d in 1836, the number of cheap publications soared; it was only in the 1850s, after the abolition of all “taxes on knowledge,” that newspaper circulation could rise into the millions. Still, though, with circulation numbers in the tens of thousands, Bell and Egan created an unprecedented demand through their use of comic pictures, attached to a cockney sensibility. These newspapers were distinctive for uniting comedy with news and politics, before comic publications split off from the news—a split registered in the early 1840s by the divide between The Illustrated London News and Punch. Sports, print, and comic pictures enabled allegiances between men across classes, as reflected in the elaborate illustrated masthead for Pierce Egan’s Life in London and Sporting Guide for August 26, 1827, titled “Real Life” (Fig. 1.11). The image details a panoramic street pageant of character types who make up the newspaper’s imagined audience, from working-class flue-flakers and dustmen up to “The Man of Taste” and the “Corinthian Charioteer.” Egan’s caption trumpets his newspaper’s unifying action: “THE GREAT INTEREST EXCITED THROUGHOUT ALL CLASSES IN THE SPORTING WORLD TO READ PIERCE EGAN’S DESCRIPTION OF A PRIZE BATTLE.” The letterpress beneath offers sycophantic comments from each character type, low to high, raving about the newspaper’s latest issue. While the image and its captions express Egan’s familiar tongue-in-cheek humor—acknowledging the absurdity of a grand pageant assembled in honor of a cheap sports newspaper—the image also reveals some of the high political stakes undergirding sporting representations, whose diversions also importantly reflected the fraught relations between men of different social classes, bound in an uneasy unity. The diverse audience for Egan’s sporting newspaper were the men who formed the body politic, to the exclusion of Victorian women.

Fig. 1.11 “Real Life.” Masthead, Pierce Egan’s Life in London and Sporting Guide. August 26, 1827. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Egan’s panoramic image drives home a salient truth about caricature and mass culture in the 1830s: there was no female counterpart to the male cockney, roaming the streets and getting into mischief. A woman of indeterminate class on city streets would have immediately signified as a prostitute. (Think of Nancy, the victimized prostitute in Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1838), who masterfully traverses London streets; no other kind of occupation could be imagined for such a mobile, urban female character at this time.) Caricature’s masculine orientation in the 1830s is especially striking given mass culture’s usual associations with femininity, a development I explore in Chapter 4, thinking about sensation in the 1860s. In this early moment, however, a masculinist mass culture emerged from specific economic and industrial transformations, which brought about new occupations for men and a political debate surrounding male enfranchisement. Women were relegated to the private sphere, where they appeared in caricatures as floozies or harpies, upholders of the family and traditional norms, and definitively not the protagonists of modernity.

Physiognomy and the New City Types

Caricatures showed an obsessive fascination with class transgressors in the new industrial economy. New urban types, occupations, and identities called for lively visual scrutiny. A comic accounting took place in one of the defining visual-verbal genres of the 1830s and 1840s: the urban typology, or “social zoology.” (In France, hundreds of different illustrated pocket-sized books, devoted to urban character types, were called physiologies.) Visual character typologies quickly assessed personhood by means of facial features, costume, and occupational status.52 Often invoking metaphors from natural history, these satirical taxonomies offered themselves as entertaining, pseudo-scientific guides to London’s chaotic culture of strangers. Cockneys, gents, idlers, and clerks—lower-middle-class male types—featured prominently in these pages, in both word and (especially) image. Caricatures limned the fine gradations that would place these ambiguous new types within social hierarchies. But they also reflected the way that social class itself was changing, loosening itself from the certainties of birth, and undermining any definitive grounds for the taxonomical assessment of character and personhood.

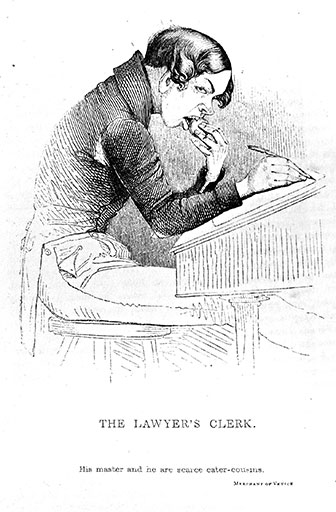

Pictorial taxonomies of urban types had their roots in the emblematic Cries of London, early-modern prints outlining working-class London types, as well as in the literary genre of the “character” popularized by Addison and Steele in the eighteenth century.53 The pictures presented portraits of occupational types that were both generic and idiosyncratic, and included figures like “the Beadle” and “the Stage Coachman.” Unlike previous kinds of character types, the incarnations of the 1830s were distinctive for invoking quasi-scientific models—influenced by the French physiologies—and for mining them with a deadpan humor. These new taxonomies devoted particular attention to the rising characters on the urban scene. Kenny Meadows’s Heads of the People, Or, Portraits of the English (1840) portrays characters from lord to factory child, but focuses especially on characters teetering on the edge of respectability, like the cockney and the lawyer’s clerk.54 (Other characters include the medical student, the lodging-house keeper, the pawnbroker, and the artist.) The portrait of the cockney paints him in a ridiculous floppy hat and high-necked travel costume, braved for his escapades in the countryside. The lawyer’s clerk is hunched over his desk, with a misshapen face and ill-fitting coat; his fingers are jointed like those of a puppet, reflecting his mechanical career (Fig. 1.12). The letterpress describes him as “a Lawyer’s Clerk, in the seedy-coated, napless-hatted, sadly shod sense of that word.”55 While the image makes the character grotesque, the letterpress sympathetically describes the clerk’s exploitation by his master. The portrait takes the ambivalent attitude of 1830s caricature, both populist and mocking, bringing a body deformed by labor into comic visibility.

Fig. 1.12 Kenny Meadows, “The Lawyer’s Clerk.” Heads of the People, Or, Portraits of the English, 1840. Courtesy University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center.

The book’s title, Heads of the People, puns on “the people” as both character types and a democratic unity, connoting popular, inexpensive print culture. Humorous violence also inheres in the idea of “heads” removed to appear in print; any joking references to “the people” in the 1830s carried hints of the French Revolution and the populist energies swirling around Reform. Again, as in the parade-themed masthead of Egan’s sporting newspaper, the tongue-in-cheek visual panorama gestures toward a political totality, invoking a national body summed up as “the English.” (The book’s introduction laughingly describes this group as “the numerous family of John Bull.”)56 In the frontispiece, the artist himself appears as a phrenologist, measuring the skull of a cretinous baby for a portrait before a crowd of onlookers (Fig. 1.13). The artist’s sprawling legs mimic the pose of the petulant baby. His funny, dandified clothes mark him as yet another mischievous male character of ambiguous class status; he makes pictures for pay while adopting the questionable authority of the phrenologist. The book’s cockney sensibility permeates its understanding of character, both satirical and sympathetic, authoritative and subversive, attacking social wrongs while maintaining a sense of social structure.

Fig. 1.13 Kenny Meadows, Frontispiece (The Artist as Phrenologist). Heads of the People, Or, Portraits of the English, 1840. Courtesy University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center.

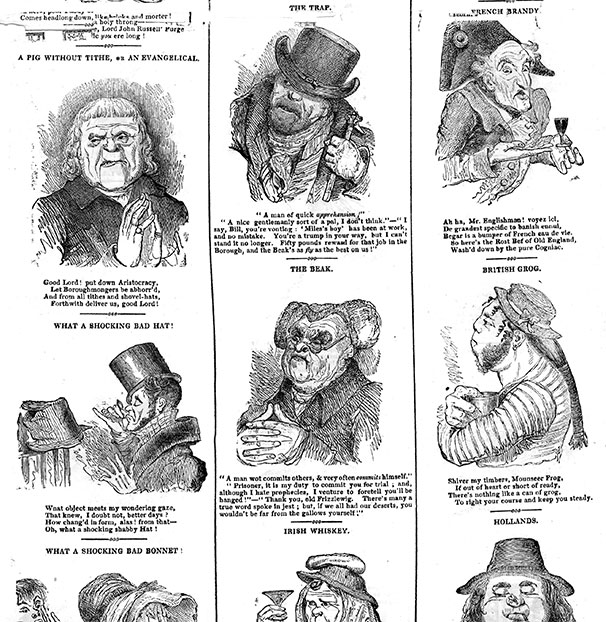

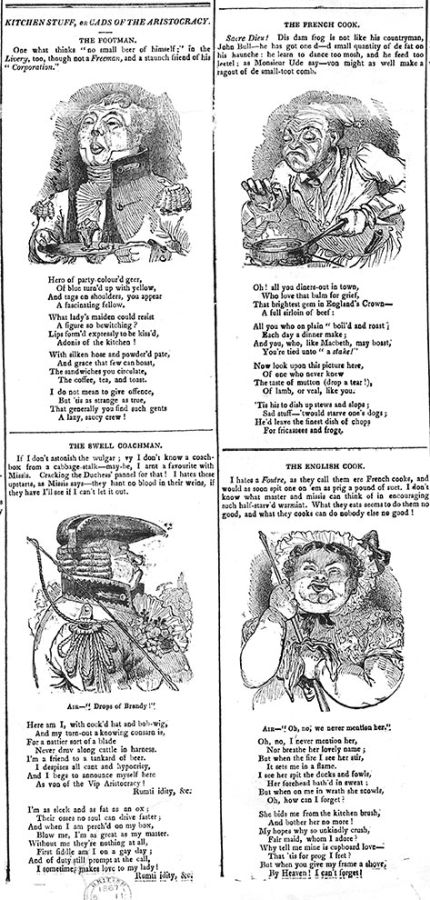

Comic urban taxonomies also appeared regularly in the Gallery of Comicalities in Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. The paper adapted Pierce Egan’s rogue-in-London sensibility, presenting news of current events, police reports, and sporting coverage, especially racing and boxing. The raucous, masculinist energies of Egan’s brand of popular culture infused the urban taxonomy genre that appeared in the newspaper’s comics. Bell’s Life ran serialized character portraits under titles such as “Craniology,” “London Particulars,” “Corporation Worthies,” “Parish Worthies,” and “Amateurs.” Kenny Meadows produced images for Bell’s Life under the titles “Studies from Lavater” and “Lavater the Second,” a mock-grand appropriation of the esteemed physiognomical tradition. Character types again ranged from high to low. In “The Beak,” a judge is rendered with monstrous features, including a bulbous wig, tiny spectacles, beaky nose, and sneering grin (Fig. 1.14). Loose pen strokes endow the figure with dynamic, evil energy, power quivering in his jowls. The accompanying text addresses “old Frizzlewig”: “if we all had our desserts, you wouldn’t be far from the gallows yourself.” While this caricature targets a highly placed official abusing his power, many of the other images mock servants or lower-middle-class merchants who are guilty of putting on airs. “The Footman” has a snub nose and fancy costume, looking supercilious while holding a tea tray; the accompanying poem dubs him an “Adonis of the kitchen.” “The French Cook” has a frog-like face and, unsurprisingly, prepares only frogs for his master (Fig. 1.15). The cartoons ridicule the pretensions of these figures, putting them in their place. “Studies from Lavater” mocks everyone equally, high and low, but its attacks on servant-type characters show a lingering investment in hierarchy and tradition.

Fig. 1.14 “The Beak.” Detail from “Sketches of Physiognomy by Lavater the Second.” Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, January 2, 1831. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 1.15 “Kitchen Stuff, or, Cads of the Aristocracy.” Detail from “Portfolio of Lavater the Second.” Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, December 24, 1832. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Caricatures of character types in the 1830s functioned as a subset of the character sketch, a genre crossing both visual and verbal media during the decade.57 Literature scholars have studied character sketches in this moment owing to the outsized influence of Charles Dickens’s early works, especially his Sketches by Boz.58 Amanpal Garcha writes that short literary forms like descriptive sketches became popular in the 1830s because they were “incomplete, fragmented, and hurried, like modern time itself.”59 Yet this familiar, Baudelairean trope captures only one aspect of the sketch genre. In fact, the sketch began as a visual form—as a preparatory version of a painting—and always retained these roots. As Brian Maidment writes of the urban sketch, “The visual is ‘illustrated’ by the verbal, and it is the image that draws the reader to the text and not the other way round.”60 When caricatures presented a gallery of faces in the 1830s, they underlined the character sketch’s relentless visuality, its emphasis on picturing, empiricism, boundedness, telescopism, concentration, abbreviation, theatricality, and grotesquerie. Character might be wholly captured and conveyed in the sketch, as quick strokes rendered a sense of completeness. The urban setting was crucial here: the character sketch or urban taxonomy tilted toward the visual because readers needed to learn to identify character quickly, using surface-based cues like physiognomy or costume.

These social taxonomies today seem reductive and essentialist, with their fixed and externalized concept of personhood. We no longer index character according to facial features; physiognomy has long been debunked as a pseudoscience. Yet modern sociology does hold that people understand the social world according to various shorthand taxonomies, especially those of social class and occupation. We come to know characters both in life and in representation via certain established matrices, economical avenues toward knowing others.61 Pierre Bourdieu writes that social class is usefully predictive as a “scientific taxonomy,” a shortcut to identity based on observations of a group’s shared “occupational conditions within a three-dimensional space.”62 For John Frow, realism in novels emerges from these shared taxonomies: realism “is grounded in a notion of the correspondence of novelistic character with an objectively given social taxonomy.”63 Frow points to Balzac’s famous “Avant-propos” to the Comedie Humaine (1842), in which Balzac analogizes his novels to natural-historical accounts of zoological species. Frow doesn’t observe the origins of Balzac’s analogy in the 1830s French physiologies, but his analysis highlights how notions of character have always mediated between typicality and idiosyncrasy, between generality and individualism.64 These opposing aspects inhere in the contradictory etymologies of “character,” which variously conjures traits, essence, the true nature or defining quality of a thing—hence the connection to “characteristic,” as in eighteenth-century “Characteristic Writing.” The gist of character can be both representative and unique. Deidre Lynch suggests that characters are “devices for thinking about typicality,” particularizing a mid-eighteenth-century usage aligning character with typography, print technologies, and the “uniform legibility of information.”65 This kind of character manifested in circulating items like coins and caricatures. Lynch argues that these modes of character faded by the early nineteenth century, but the examples in later caricatures suggest that the type-based, surface model of character persisted onwards into modernity. Caricatures of social taxonomies epitomize a foundational crux at the heart of character’s conception, producing both typicality and eccentricity, driving toward both legibility and illegibility. Idiosyncratic types threatened to devolve into grotesque, inimitable individuality, encompassing urban forces of the unreadable and the anonymous.

In fact, 1830s taxonomies of character emerged alongside a sense of breakdown in character, a transformation that was disruptive and profound. Instability is a defining note, for instance, in the Bell’s Life comic character portraits titled “London Particulars.” The portraits depend on the “particularity” inherent to the caricature genre, grounded in details of real bodies and observed costumes. (Characters include “the Flying Stationer” and “the Hearth-Stone Merchant.”) Yet the series title also puns on the “London particular,” a famously dense and impenetrable urban fog.66 The pun epitomizes caricature’s ambiguous swerves between knowingness and anonymity, recognizable type and unknown personhood, all the mysteries defining contemporary urban observation.

It’s no coincidence, then, that the cockney emerged as a riotously popular type at the same time that social taxonomies were becoming widespread: caricatures were drawn to characters who, by definition, were hard to place. Popular early-Victorian character types reflected an attraction to rogues and waifs, cockneys, sportsmen, gents, idlers, nobodies, urchins, and criminals—characters who transgressed social boundaries, even while participating in the creation of newer, finer hierarchies on the urban scene. Many of these figures were lower-middle-class men. Albert Smith’s “social zoologies” series featured The Natural History of the Gent (1847) and The Natural History of the Idler Upon Town (1848). The gent, like the cockney, was a ubiquitous caricatured city type, the lower-middle-class man with social aspirations. He was typically “without dependents,” writes Jo Briggs, “in [a] skilled job that paid well enough to leave a little spare cash for small luxuries, cheap ready-made clothes, and low-brow entertainments.”67 Gents imitated aristocratic gentlemen in their dress and leisure pursuits. Smith’s Natural History of the Gent pictures the type in absurd costumes and behaviors; one illustration shows gents smoking at a billiards table, attired in ridiculous checked pants (Fig. 1.16). As the letterpress notes, these gents puff the smoke from “cheap cigars” “into every bonnet they meet,” standing “with a whip in their hands, as though they had just got off their horse,” even though “in reality they have no horse.”68 The gent pretends to be a high-class gentleman, but his bad manners and poor imitation give him away. As Briggs concludes, “[B]y reproducing the styles and mannerisms of the middle and upper classes, the gent drew attention to the performative aspects of class.”69 The whole premise of the gent threatened to undermine social distinction, as poor men imitated the rich. Even while caricatures mockingly put these men back into their place, establishing social order and hierarchy, the images also reveled in their transgressions. Gents, cockneys, and idlers became mock-heroic city types, new subjects of sympathy and identification.

Fig. 1.16 Gents playing billiards. Illustration from Albert Smith, The Natural History of the Gent, 1847. Courtesy Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives.

The idler was another caricatured male type of the 1830s who transgressed boundaries and invited both scorn and celebration. Whereas the eighteenth-century Idler was a leisured, wealthy essayistic persona, the nineteenth-century lounger was no longer an aristocrat. (Boz, the roving narrator of Dickens’s Sketches by Boz, calls himself an “amateur vagrant.”) The idler connoted the cockneyism of Egan’s Life in London—always male, and defined by urban wandering and subversive leisure rather than virtuous labor. The idler occupied a special role within the world of urban taxonomy, since his was the peripatetic eye that classed the types around him. Walter Benjamin notes how the flâneur produced a natural history of types: “The physiologies were the first booty taken from the marketplace by the flâneur—who, so to speak, went botanizing on the asphalt.”70 Benjamin’s ironic tone echoes the mocking scientific language defining 1830s urban taxonomies. Albert Smith’s The Natural History of the Idler Upon Town (1848) highlights the idler’s superficial, sham qualities; he loiters on elegant shopping streets in the fashionable season, yet, when found at home, his underclothes are humorously threadbare.71 To lounge or to be idle, to wander the city streets without a known destination, was to behave in a way inimical to the new capitalist demands on human labor and productivity.72 The idler was an outsider who perceived social difference; he was attentive to norms, types, deviance, and criminality. Baudelaire’s admiring sketch of the flâneur in “The Painter of Modern Life” offers a canonical portrait of the figure, but Baudelaire’s 1863 essay actually came in the wake of a defining genre of the 1830s, which comprehended urban life via comic taxonomies, especially those featuring new, ambiguous male types.

While caricatures or comic sketches published in sporting newspapers might seem like lightweight pieces of popular culture, we are beginning to see how cockney comedy spoke to some of the deep transformations in Britain’s social and economic world. On the one hand, these pieces assigned character from the outside: personhood was a materialist production of body, occupation, costume, and neighborhood, locating one precisely inside the social system. Caricature taxonomies were invested in hierarchy, typing, and social order, the conservative policing of boundaries and behaviors. Yet these acts of visual and ideological petrification occurred in the midst of radical social transformation. Sharrona Pearl describes the paradox by which the cues to hierarchy proliferated, even as the hierarchies themselves became permeable: “Within the socially mobile structure, subtle signs of hierarchy, from street labels to social clubs, from seating arrangements to visiting protocols, rigidly marked the [class] distinctions even as they seemed to become more penetrable.”73 Social taxonomies reflected the new uncertainties swirling around social class, as identity was no longer ingrained from birth within an organic and unchanging social totality, but became unanchored and malleable, defined now by more fungible qualities like education, manners, and cultural capital. Class might be adopted and performed. Caricatures visually captured this new, flexible idea of character in their stylistic treatment of human bodies: figures vibrate with the energy of personality, flattened into type, yet grotesquely expressive. The “Studies from Lavater” pigeonhole different character types, but the humorous images—with faces bulging or leering, bodies corpulent or stringy—perform a visual satire of human knowability, detailing a class-based personhood both definitive and elusive.

The darker side to cheerful comic taxonomies appeared in grotesque bodies, deformed by exploitative labor conditions, crushed by grinding poverty, or swollen with ill-gotten gains. Urban typologies were produced against the background of working-class unrest in England and France, with France’s 1830 revolution and England’s pre- and post-1832 working-class activism. Portrayals of character in Britain, visual or verbal, took place amid new Police Acts, Poor Laws, and Reform Acts, all problematically circumscribing who was included in the social body, and how. These political energies cast a Gothic darkness over popular culture of the decade, destabilizing the forms of urban character. (Hence the decade’s embrace of criminal male anti-heroes: Dick Turpin, Jack Sheppard, and the pickpocket crew of Oliver Twist.)74 Caricaturists like Cruikshank, Seymour, and Phiz were artisans of the grotesque, as were the writers like Dickens, Carlyle, or Edgar Allan Poe. While the social zoologies tradition has been aligned with the rise of realism and the focus on the everyday, caricature taxonomies pushed toward another strain, a counter-visuality giving expression to energies that were misshapen and savagely comic.75 Contemporary economic and political forces, deforming of body, mind, and spirit, produced bodies all too legible, and also fantastically excessive, grotesque, ridiculous—driven at times beyond legibility. The darkest aspect of caricature’s grotesque bodies invited a nihilism of the type anatomized by Poe in “The Man of the Crowd”—in which taxonomy breaks down in the face of an illegible man who cannot be classified. How can character be stable in a precarious world of exploitation, vicious competition, and body-breaking labor? Early-Victorian social zoologies produced a de-natured nature, a new, discomfiting truth of the body beyond the proper bounds of science, respectability, or comforting categorization—even while still deploying all of these qualities, laughingly, to create visual taxonomic forms. Caricature’s contributions in this genre emphasized both the construction of type and its implicit deconstruction, undermining classifications even while reproducing them en masse.

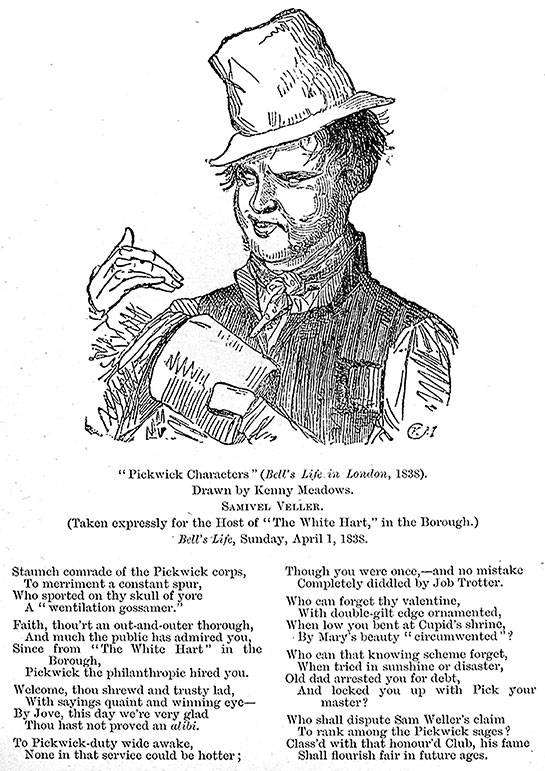

Pickwick’s Caricatures: Comedy, Violence, Servitude

If the 1830s were a defining moment in the history of visual culture and popular culture, then a key contributor to this realm was the young Charles Dickens. Dickens operated within a larger, rambunctious, visual-verbal print culture notable for extensive intertextuality and intervisuality. His three earliest works in fact emerged from extant caricature themes: the comic urban taxonomy in Sketches by Boz, the sporting sketch in The Pickwick Papers, and the den of thieves in Oliver Twist. The popularity of these literary works in turn inspired a busy afterlife in the popular visual realm. Dickens adapted caricature forms with a readymade audience, and imitators in turn capitalized on his innovations in both images and words, unleashing character across different formats. This discussion will focus on The Pickwick Papers, one of the most influential pop-culture items of the 1830s, and instigator of a kind of viral mass culture familiar to us today. Scholars have discussed how Dickens’s innovations in serialization contributed to The Pickwick Papers’s runaway success. Less noted, though, is the fact that the book’s most popular character, the ebullient servant Sam Weller, is another incarnation of the cockney, the masculinist rogue-about-town with deep caricature roots. Sam Weller exceeds Dickens and literary contexts: he embodies the astonishing porousness between popular visual, verbal, and theatrical forms in the 1830s, while once again signifying the political and masculinist elements of cockney caricature humor.

Reviewers in the 1830s often described the young Dickens as a visual writer, comparing him favorably to famous visual artists. “The Soul of Hogarth has migrated into the Body of Mr. Dickens,” announced one Pickwick reader. A reviewer of Sketches by Boz called him “the CRUIKSHANK of writers.”76 Gerard Curtis tracks Dickens’s transformation across the 1830s from caricature artist (“Boz”) to respected literary author (“Charles Dickens”)—as reflected in portraits of Dickens, which began as caricature outline sketches and arrived at a grand 1839 painting by Maclise.77 Dickens’s rise involved a shift from image to word, as the pre-eminence of caricatures gave way to the dominance of the literary text. In fact, Jane R. Cohen argues that Dickens himself was responsible for reversing the equation during his lifetime, inaugurating the supremacy of author over artist.78 This reversal suggests that Dickens’s earliest works should be read differently than his later works, with a more visual understanding of their narratives, effects, and characters.

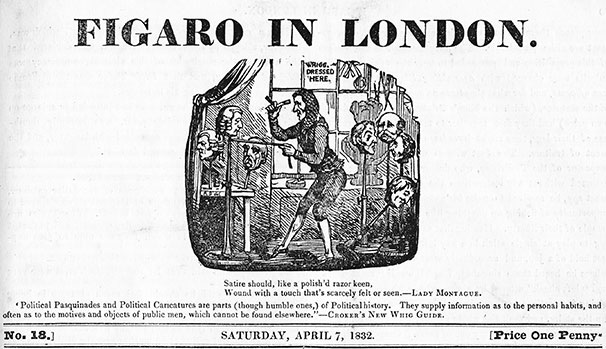

Pickwick in fact emerged from a popular visual culture in which images drove the market. Publishers profited by taking a set of extant pictures and then commissioning a subordinate, posterior letterpress. The Pickwick Papers had its source in exactly these circumstances: Chapman and Hall hired the young Dickens to provide the letterpress for a series of sporting sketches by caricaturist Robert Seymour. Pickwick has usually been read within literary studies as Dickens’s “first novel,” but a turn to the visual situates the work as a verbal-visual production whose character types came from the caricature world. In fact, when returned to its original visual contexts, Pickwick seems less like a shaped, literary form and more like a series of sketches, serialized episodes framed around externalized, comic characters. Pickwick expresses the pop-culture sensibility of the 1830s in its visual modes of character, its unruly serialized forms, its picaresque and grotesque tendencies, and its cockney, bachelor sensibility. My analysis focuses on the important caricature models provided by Robert Seymour, both in his sporting sketches and his political cartoons for the caricature magazine Figaro in London. These images testify to Pickwick’s striking intervisuality, as it adapted and elaborated on existing cockney humor. Seymour’s subversive antecedents inform Pickwick’s volatile overtones, reflecting the moment’s uneasy populism.79 Though the novel has most often been read as a conservative allegory of bourgeois benevolence—a hymn to the peaceful coexistence between masters and their men—Seymour’s cockney content suggests that the novel should be read, alongside the caricatures of the moment, as a document of Reform and its failures.80

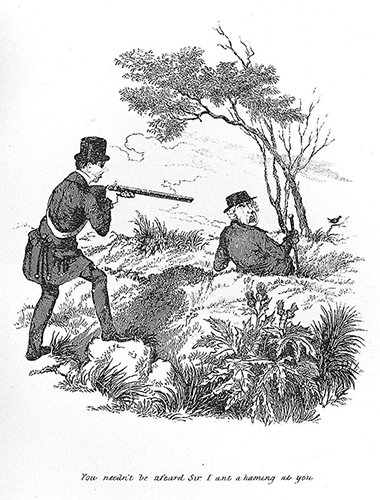

Pickwick’s portrayal of urban men bumbling their way through the countryside emerged from Seymour’s popular sporting sketches. These cartoons, first issued between 1834 and 1836 as loose-leaf prints for 3d each, depicted all the familiar tropes of cockney sportsmen that Pickwick would reproduce—clumsy horseback riders, impolitic men skirmishing with landladies, trespassers fleeing from aristocratic property owners, hunters accidentally shooting each other in the face. In one pastoral caricature, a gentleman observing a bird on a branch is rudely interrupted by a cockney aiming a gun at his head (Fig. 1.17). “You needn’t be afeard Sir I ant a haming at you,” reads the caption. Comic, violent possibilities abound in the city man’s incompetence with his weapon. While lampooning the careless cockney, the cartoon is also ambiguous in portraying the startled gentleman as monstrous-looking: it implies that there might be something satisfying in accidentally discharging a gun into a rich man’s face. Seymour’s sketches, with their inept trespassing hunters and shooters, depict comic versions of more troubling incursions. Men with guns are overrunning the grounds of landowners, threatening life, limb, and property. These insurrections occur in an upside-down carnival world, giving expression to violent populist energies whose humor arises from transgressed boundaries, especially those of property and geography.

Fig. 1.17 Robert Seymour, “You needn’t be afeard Sir I ant a haming at you.” Seymour’s Humorous Sketches; Comprising Eighty-Six Caricature Etchings Illustrated in Prose and Verse by Alfred Crowquill. [1866], 1888. Originally published as loose-leaf etchings, 1834–6.

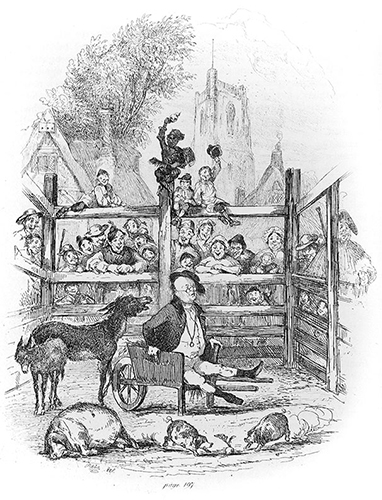

Similar political undertones infuse the mock violence of Pickwick’s hunting-themed humor. These undertones inflect both the visual and verbal elements of the book’s sporting episodes. (Though Seymour started as Pickwick’s illustrator, his untimely death in 1836 led to his replacement by Hablot “Phiz” Browne, who continued in Seymour’s comic vein.) Cockney ambiguities abound in Phiz’s illustration of “Mr. Pickwick in the Pound” (Fig. 1.18). Pickwick, having drunk himself unconscious at a hunting party, awakes to find himself dumped in the village animal pound by the outraged landowner on whose land he was trespassing. In Phiz’s picture, Pickwick perches awkwardly in a wheelbarrow while a village donkey brays at him, pigs fight over an apple, and the villagers look on with hilarity. This scene visually reproduces the well-known Cruikshank illustration, from Life in London, depicting Tom and Jerry at the Westminster dog pits (Fig. 1.10). In both images, animals sport in the foreground, while spectating faces behind are framed by a wooden scaffold. Cruikshank’s version divides the humans from the animals, but also implies that the audience—gambling, bloodthirsty, and mixed-class—shares animalistic qualities with the fighting monkey and dog. Phiz’s version trumps expectations by placing a bewildered man in the pit: Pickwick grubs with animals in the muck, transgressing the boundaries of respectability.

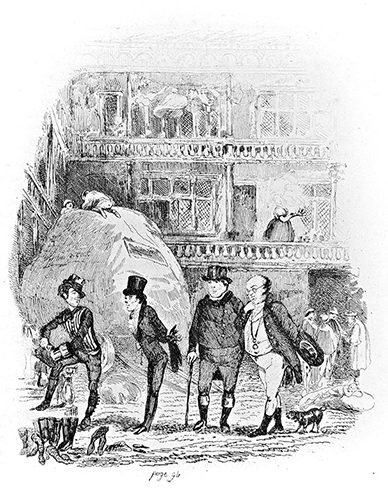

Fig. 1.18 “Phiz” (Hablot K. Browne), “Mr. Pickwick in the Pound.” The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, 1836. Courtesy Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives.