4

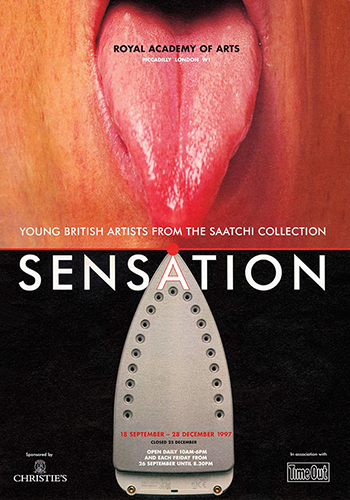

Sensation

Cartomania: Sensation, Celebrity, and the Photographed Woman

The sensation phenomenon exploded onto Britain’s cultural scene in the early 1860s with remarkable excitement and vehement critical pronouncement. From “sensation drama” in the theaters to “sensation art” and “sensation novels,” numerous media were accused by Victorian critics of embracing lurid themes to stimulate an eager audience. Scholars today have mostly studied sensation as a literary phenomenon, analyzing its novels for their social climbers, bigamists, murderesses, and other outrageous characters and plotlines. Yet sensationalism in the 1860s was not limited to the literary sphere, and critics claimed to detect its nefarious influence in any person or event drawing a crowd—tightrope walkers, trapeze artists, criminals, even paintings and photographs. In this chapter, I expand our understanding of sensation by looking to its visual cultures, especially to a new type of photography that amplified sensation’s interests in the spectacularized female body.

The chapter focuses on cartes de visite, a form of mass portrait photography that became tremendously popular in the early 1860s, coinciding with sensation’s moment. Known as “cartomania,” the craze inspired Victorians to collect millions of small photographic portraits of both friends and celebrities. The idea of a “mania” seems appropriate to the sensation moment, connoting a fast-moving trend poised on the cutting edge of modernity—and fated for quick obsolescence. Some 300 to 400 million cartes were sold in England every year from 1861 to 1867, before their popularity began to wane in favor of other photographic products.1 Scandalous public women appeared across a range of media in London in the early 1860s, but that array was multiplied in the carte de visite, especially in best-selling photographs of indecent or criminal women. Actresses, opera divas, prostitutes, even Queen Victoria: sensation’s visual cultures emerged from a new kind of female celebrity centered on image, eroticism, and a faddish temporality.

Both sensation novels and cartes de visite were denounced by critics for similar sins—for appealing across class lines, for implicitly challenging social hierarchies, and for depicting immodest, powerful women. By analyzing how sensationalism proliferated across genres—especially, and including, visual genres—this chapter aims to change how we define the phenomenon. Victorian critics saw sensational objects as electrifying the consumer’s body with a visceral immediacy; they often imagined a lone female reader closeted in her boudoir, devouring an illicit novel with unseemly abandon. Contemporary accounts have at times echoed Victorian critics in highlighting sensation’s body effects, seeing its objects as literally stimulating the reader’s sensorium.2 Yet the chapter will show how “sensation” described artifacts that were constructed, mediated, and commodified—they pertained to a nascent mass culture, and hence were an inherently social phenomenon. Sensation in fact produced its body effects via a series of mediations, as critics and consumers generated the atmosphere of breathless fashionability and scandal that drove the market for these items. As such, the medium of portrait photography perfectly captured sensation’s dialectical investments in both brute embodiment and a framing sociality. Women on view in cartes de visite became sensations in one of the word’s other senses—as best-selling celebrities, hot properties marketed in legitimate capitalist enterprises. These female spectacles invited physiological response, as a woman’s body could be bought and sold and handled in card format. Yet this stimulation of the nerves took place via a technology of embodiment, a series of mediations that began with the ability to produce paper photographs in millions of copies.

Nineteenth-century photography also appears differently when it is read as sensational. These images have typically been read as part of the century’s broader empiricist drive, as photography produced a vast visual archive of faces and bodies, especially those belonging to Britain’s others, whether the urban poor or the subjects of empire. For many scholars, the ostensible realism of the photograph merely served to affirm stereotyped notions of otherness, buttressing imperial ideologies. Critics have therefore insistently looked past the image’s suspect qualities of materialization or embodiment, directing us instead to observe a photograph’s qualities of staging, artifice, omission, and illusion.3 Geoffrey Batchen, in his account of the carte de visite, goes one step further, undercutting the photograph’s illusion of presence by seeing it as a precursor to postmodern forms of visual abstraction and dematerialization. Batchen argues that the carte’s bourgeois repetitiveness avoids any humanistic depth or singularity, embracing that which is “impure, a copy of what is already a copy and nothing more … [The carte-de-visite sitter] is all surface and no depth.”4 While contemporary theories are convincing in their critiques of Victorian norms, philosophies, and politics of the image, they differ significantly from the historical reception of cartes de visite in the 1860s, when audiences responded to the flood of mechanized portraiture by focusing intently on the bodies that photography captured in realistic, graphic detail. The mass photographic portrait was indeed characterized by the illusionism and simulation described by contemporary scholars; but—fittingly, for the sensational moment—it also offered a new kind of embodied medium to its Victorian viewers, a powerful and unprecedented verisimilitude defined by its haptic qualities.

In creating “sensation,” cultural critics were appropriating a term from the nineteenth century’s new nerve science. Human beings, no longer creatures of reason and divine good, were being rewritten as irrational animals whose reflexive nervous sensations might short-circuit the brain entirely.5 When critics accused objects of courting sensation, then, they were applying a scientific term in the cultural realm, responding to the threat of a thrilling new mass culture that seemed to target the body for basely commercial purposes—a paradigm still familiar today, as I discuss in the chapter’s conclusion. Sensation’s implicit links to nerve science suggest that touch was the movement’s master-sense. Yet my account, focused on photography as a sensational medium, argues that mass culture in the 1860s targeted both touch and vision simultaneously, coupling the two senses. While photography scholars today have trained us to treat the medium’s transcriptions of reality with skepticism, Victorian critics often took a contrasting view, fixating upon photography’s primal touch of light to an exposed surface. The mythical purity of that exposure, for many Victorian viewers, imparted to a photographed body an inexorable materiality, no matter how mediated the image itself might have been. Photography’s new, haptic visuality inaugurated an eroticized celebrity culture organized around pictures of women’s bodies, a connection that has come to be definitive in our own contemporary media culture.

The carte de visite’s innovations extended beyond an unprecedented portrait verisimilitude. The mass portrait photograph also signaled the triumph of photographic reproduction on paper, a technological advance that showed the medium’s importance, in the words of Richard Menke, “not just for recording or representing reality but for disseminating it.” Menke speaks of Fox Talbot’s earliest experiments, as the photographic researcher came to realize that the new technology could potentially circulate images on an immense scale. Paper photography’s truly distinctive feature, distinguishing it from previous forms, was its iterability. From this perspective, as Menke notes, the paper photograph moved away from singular, unique media like paintings or daguerreotypes and toward the realm of the printed book.6 The carte de visite therefore belonged to a broader print culture, across word and image, that was defined by its unprecedented capacity to reproduce and circulate in vast numbers. The carte’s iterability invited a strongly politicized discourse: the portrait photograph oscillated between promoting individual celebrity and fostering a formulaic, mass experience. Sensational cartes encouraged the reproduction of identity (especially female identity) for an audience whose individual experiences were shaped by a mass visual culture, whether through perusing photographic shop windows or leafing through home albums. Sensation itself, I argue, depended on a dialectic between forces of celebrity—conferring an idea of the extraordinary, the unique, the exceptional, and the individual—versus forces of massification, in reproduction, repetition, democracy, universality, and interchangeability. Both of these forces, it should be noted, served as a challenge to traditional class hierarchies. This dialectic was especially apt for a decade that witnessed the mass enfranchisement of working-class men, and it figures in both sensation photographs and sensation novels, as the chapter will pursue.

Though sensation emerged as part of a new, broadly circulating mass culture, it was not completely cordoned off from realms of high culture. As befits a cultural phenomenon embraced by the Victorian middle classes, sensation was defined by its mixed, hybrid qualities, blending genres high and low. The carte photograph drew on conventions of eighteenth-century painted portraiture, and it often triangulated the diverse media of painting, photography, and theater. Sensation theater and sensation novels both crafted dramatic scenes in the form of shapely pictures, investing visual pleasure into the spectacular moment. Not surprisingly, these theatrical pictures often framed women’s bodies, arranging them in striking tableaux. Sensational novels and photographs confounded critics with their mixed-class associations: reviewers of sensation novels couldn’t agree on whether or not they constituted high art, and commentators on mass photography confronted portraits of actresses and criminals alongside those of bishops, Prime Ministers, and the Queen. The political and social-class transgressions of sensational objects expressed themselves as contraventions in the aesthetic realm, mixing genres and intermingling different types of media, new and old.

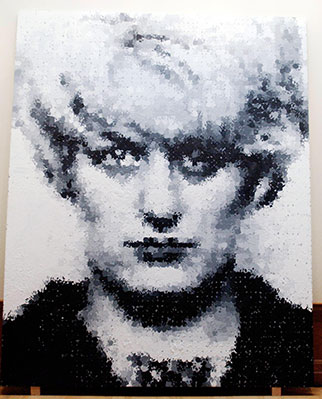

The chapter moves through a brief history of carte portraiture and its rhetorics of democratization before turning to the most sensational figures in the carte, those of improper or illicit women—prostitutes, actresses, and female criminals. I show how Eliza Lynn Linton’s notorious, conservative rant against “The Girl of the Period” (1868) reacted to the new, fashionable (photographic) visibility of the demi-monde, which, to Linton’s despair, the modern English girl was attempting to imitate. Cartes promoted a new kind of female celebrity, in which women became famous owing to a fashion or a provocative style rather than through a more traditional route such as aristocratic birth or class status. Actresses and opera divas personified this troubling new visibility, and actress cartes in particular brought together the media of theater, painting, and photography in combining old and new portrait traditions. Queen Victoria, the dour matron herself, makes a surprising appearance within sensation’s visual field as the female subject whose carte portraits were the most popular and highly visible, and whose example linked her to other, controversial kinds of female celebrity. I also examine the carte portrait depicting Sarah Forbes Bonetta, an African child adopted as a god-daughter by Queen Victoria, in order to investigate sensation’s inherent relationship to race, skin, and spectacles of human difference. The themes raised by carte photographs of women—issues of embodiment, visual display, and female self-determination—inflected the plots of sensation novels, especially Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White and M. E. Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret. The photographic medium served as a lightning rod for questions of female conformism and female display: these questions rehearsed the larger, vexed political problem of the exceptional individual’s relation to the mass. While conservative critics lashed out when a woman made a sensation, became famous, or came to be deemed “extraordinary,” a voracious celebrity culture—which had its major instantiation here—encouraged and rewarded women for performing ambiguous feats of self-making via the image.

Making Sensation

What was sensation? Victorian critics saw sensational arts as producing a body effect, an agitated physiological response modeled by characters or actors and then mimicked by breathless readers or spectators. Sensation novels “preach[ed] to the nerves,” in H. L. Mansel’s memorable 1863 formulation. More than a century later, D. A. Miller similarly sees the genre “address[ing] itself primarily to the sympathetic nervous system, where it grounds its characteristic adrenalin effects: accelerated heart rate and respiration, increased blood pressure, the pallor resulting from vasoconstriction, etc.”7 Miller’s account echoes the nineteenth-century view, distinguishing the sensation novel for its stimulating biological effects on a lone perceiver’s body. Yet this physiological conception misses the way that sensation emerged out of an inherently group-oriented mass culture, marketed and packaged by both critics and consumers. Sensation’s fashionable, crowd-driven aspect is apparent in the commodities it inspired, such as those spun off from Wilkie Collins’s blockbuster sensation novel The Woman in White, which included toiletries, bonnets, songs, even a quadrille (Fig. 4.1).

Fig. 4.1 The Woman in White Waltz, by C. H. R. Marriott, lithograph cover of sheet music. London: Boosey & Sons Musical Library, [1861]. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. h.842.a.(34).

Sensation’s objects belonged to a consumer culture that mediated between the individual and the group, relying, writes Lynn M. Voskuil, “on the arousal of individualized desire in a large body of potential buyers.”8 While sensation’s body effects appeared to be individualistic, involuntary, erotic, even masturbatory in their targeted pleasures, their apparent naturalness was belied by the fact that they occurred among large audiences witnessing formulaic plot structures and familiar character types. This clichéd quality was especially true of the sensation dramas that first ignited the sensation craze in Britain. As Voskuil notes, for all of sensation’s ostensible spontaneity, theater audiences knew beforehand how they were supposed to react to these kinds of plays.9

Sensation had some of its roots in America, where the term first became a buzzword. A Punch ditty of 1861 riffs on the sensational qualities of America, “that land of fast life and fast laws—/Laws not faster made than they’re broken.” This world of accelerated novelty is multifarious enough to include “[t]he last horrid murder down South,/The last monster mile-panorama;/Last new sermon, or wash for the mouth;/New acrobat, planet or drama.”10 Sensation encompassed any event or spectacle that drew a crowd, from murders to mouthwash, from panoramas to slavery. Punch gets comic mileage out of this incongruity, but Kimberly Snyder Manganelli argues that British sensation novels had their antecedents in American novels about slavery, a connection worth remembering as the chapter studies the spectacularized female bodies consumed on the British scandal circuit of the early 1860s.11 The specter of race haunts all of these circulated bodies, as I pursue below.

While the British origins of sensational arts are multiple and diverse, the first cultural artifacts to be labeled as “sensation” took place on the stage. Sensation dramas featured stunning effects and breath-taking illusions, from crashing waterfalls to moonlit caves. These special effects were manufactured by ingenious stage technology, tying sensation dramas to other kinds of techno-enhanced illusionism considered in this book. (In Chapter 5, for example, I discuss how picturesque dioramas likewise used innovative stage technologies to fabricate their illusions of “nature.”) A sensation scene onstage usually dramatized a climactic narrative moment with an arresting, time-stopping tableau. Dion Boucicault’s sensation drama The Octoroon (1859) culminates in a thrilling slave auction scene, in which the sympathetic, mixed-race heroine Zoë is sold at market.12 A reviewer in 1861 highlighted the scene’s spectacular visual qualities: “The slave auction forms the grand sensation scene of the drama, … and forms a most exciting tableau.”13 The Octoroon’s tableau is a quintessential sensation scene, featuring a light-skinned woman of ambiguous race, origins, and identity offered on a pedestal for sale, as well as for audience delectation. The climactic tableau points to the way that picturing itself was crucial to sensation, not only for the commodification implied in mass spectacle, but also for the characteristic mixing of media. Elements of both painting and photography informed the theatrical tableau, infusing visual pleasure into the dramatic moment.

Sensation novels, taking their label from sensation dramas, produced scandal-mongering plotlines often taken from journalism covering criminal trials and divorce-court proceedings. Earning the moniker “newspaper novels,” these books drew upon media events and modern tabloidism to become their own form of titillating media.14 For all of their Gothic twists, sensation novels were crucially sited in the modern Victorian drawing room, amid English characters and everyday life.

The man who shook our hand with a hearty English grasp half an hour ago—the woman whose beauty and grace were the charm of last night, …—how exciting to think that under these pleasing outsides may be concealed some demon in human shape, a Count Fosco or a Lady Audley!15

So writes Henry Mansel in 1863, in his famously scathing review. As Mansel’s words imply, sensation also depended on its opposite, the veneer of normality under which seething, subterranean forces raged. Tim Dolin writes of the social pressures that produced the sensation aesthetic, as the nineteenth century’s “cataclysmic social change” was “internalised and made secret”: the “deceptive blandness” of Victorian exteriors disguised “a violent suppression of difference, an effect of commodification, rationalisation, and standardisation in capitalism, consent in politics and class relations, Puritanism in religion, and respectability in everyday life.”16 As we will see, cartes de visite entailed a similar combination of the conventional and the extraordinary, as the repetitive uniformity of cartes poses and settings mirrored the formulaic quality of everyday middle-class life, even while certain cartes gained their allure by depicting transgressive celebrities.

Sensation emerged out of a nascent mass culture that is familiar today, a world of hype, puffery, gossip, tabloidism, and celebrity. Critics liked to stress the word’s double meaning as both a corporeal stimulus and a broader cultural vogue. “Nothing will stimulate the jaded appetites of the English populace, except what has been called a sensation,” opined a critic in 1863. His discussion goes on to attack sensation novels as part of a degraded exhibitionary culture catering to the basest human desires.17 In the vast critical commentary on sensation in the early 1860s, these objects were seen to capture the zeitgeist. Critics and satirists hurled the fashionable insult at anything that cultivated novelty. They produced their own echo chamber in periodical articles and poems by invoking a reliable set of recurring persons and things that qualified for the inflammatory label. Inevitable points of reference included the tightrope-walker Blondin and trapeze artist Leotard; Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, especially its “Chamber of Horrors”; novels such as The Woman in White and Lady Audley’s Secret; the sensation dramas of Boucicault, especially The Colleen Bawn; the cartes de visite craze, in which photographs of known and unknown persons mingled promiscuously in albums and shop windows; also Julia Pastrana, a bearded woman whose mummified corpse was exhibited in London in 1862; Constance Kent, the teenage girl accused of murdering her four-year-old brother; and “Anonyma,” a nickname for Catherine Walters, a well-dressed courtesan who attracted great crowds when she rode her horse in Hyde Park. (All of these appear, for example, in the comic poem “Sensation! A Satire,” of 1864.)18 Not coincidentally, many of these sensational objects feature women of doubtful backgrounds or boundary-crossing identities, publicly displayed in prurient or eroticized contexts.

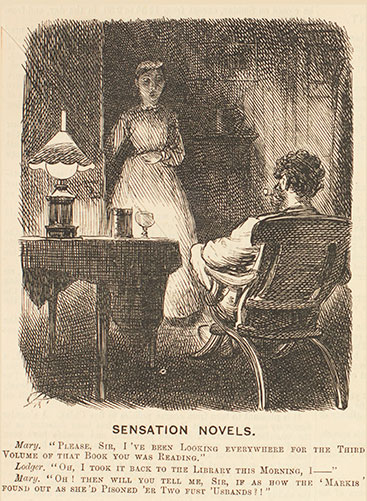

Many scholars have focused on sensation’s obsession with women’s behavior, especially women behaving badly.19 Sensation novels portrayed women violating norms of both class and sex, usually at the same time. In an 1868 Punch cartoon titled “Sensation Novels,” a maid startles “a Lodger” in his private rooms to ask how the final volume of a sensation novel turns out—“how the ‘Markis’ found out as she’d pisoned ’er two fust ’Usbands?!” (Fig. 4.2).20 The joke turns on the maid reading the same literature as her master, which leads her to invade his private chambers at night in a manner both unseemly and risqué. In the cartoon’s clever innuendo, the fictional wife’s crime of poisoning—presumably to climb up the ladders of wealth and rank—is analogous to the maid’s impertinent interruption. The cartoon’s visual format itself imitates a sensation scene, as the maid hovers like a ghostly, white figure at her master’s door. Maids inevitably recurred as key characters in sensation mania, inspiring both anxiety and desire; the uppity or emboldened female house servant perfectly typified domesticity gone awry.21 Yet even while sensation novels often demonized powerful, scheming women, they also granted them attractive qualities of intelligence, dominance, and sex appeal, offering an ambiguous twist on the contentious Victorian “Woman Question.”

Fig. 4.2 “Sensation Novels.” Punch, March 28, 1868.

The larger politics of sensation are similarly complicated. Some scholars have seen sensationalism as a conservative, negative response to the progressive shift in the 1860s that culminated in the 1867 Reform Bill.22 Most sensation novels conclude by vanquishing the villainous boundary breakers and class crossers, ensuring a safe return to social order. Other scholars, however, have noted how sensation novels jubilantly blurred class and identity boundaries, a confusion expressed formally in the novel’s mixing of literary genres with popular or working-class modes.23 All of these contradictory accounts seem valid, pointing to sensation’s indeterminacy as a series of mixed cultural objects in many senses. A similar aesthetic and political confusion also surrounded the carte de visite, as I’ll now pursue: the new portrait photograph adapted eighteenth-century modes of aristocratic, painted portraiture to the everyday world of the modern bourgeois subject. If class boundaries in the 1860s were being destabilized in the political world by the enfranchisement of working men, a similar unhinging was occurring in the cultural world among the objects of entertainment, both novelistic and photographic.

Cartes de visite and Mass Portrait Photography

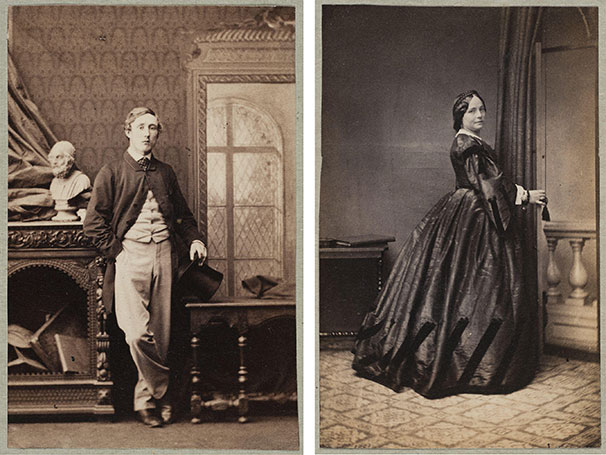

A confluence of technological and economic changes propelled the carte de visite to cultural dominance in the early 1860s. Before the carte, the most popular kind of photograph had been the daguerreotype, an expensive, one-of-a-kind image, printed on luminous reflective metal and contained in a decorative case (Fig. 4.3). In the 1850s, a new wet-collodion process using glass negatives enabled photographs to be made in multiple copies and printed on albumenized paper. Additionally, the innovation of a special multi-lens camera allowed for eight images to be created in a single sitting, reducing the cost and time needed to make the portrait photograph (Fig. 4.4). By 1860, as photographic historian William C. Darrah notes, all of the necessary photographic equipment—papers, lenses, chemicals, studio props—were being manufactured on a large scale, leading to photography’s massive commercialization and standardization.24 These shifts led to the explosive growth in cartes de visite. The carte itself was a small photo, usually a portrait, mounted on a card of approximately two-and-a-half by four inches (Fig. 4.5). Unlike the daguerreotype, which was precious and unique, the carte de visite was cheap, easily reproduced, and existed in multiple copies. Despite its name, the carte was rarely used as a visiting card; instead it was collected, traded, and displayed in drawing-room albums. Portable and highly collectible, the carte epitomized a new kind of reproducibility and circulatability in the nineteenth century.25

Fig. 4.3 Daguerreotype of Mary Lang Bailey (American), c. 1850. William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Fig. 4.4 André A.-E. Disdéri, Uncut sheet of eight carte-de-visite photographs of an actress, c. 1860. Collection of Jack and Beverly Wilgus.

Fig. 4.5 Two cartes de visite by an unknown artist from the V & A museum collection, albumen sheet, c. 1860–70. Museum numbers E.1740:1-1995 and E.1691:3-1995. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

For many critics in the 1860s, the carte de visite’s most salient aspect was its democratization of portraiture, which had previously been a privilege of the wealthy. The Photographic News writes in 1861:

Photographic portraiture … has … swept away many of the illiberal distinctions of rank and wealth, so that the poor man who possesses but a few shillings can command as perfect a lifelike portrait of his wife or child as Sir Thomas Lawrence painted for the most distinguished sovereigns of Europe.26

Some critics found this leveling in the visual sphere to be amusing but also problematic, as women and men appeared in poses and props above their wonted station. An 1863 essay mocks “Mrs. Jones” and “Miss Brown” for posing themselves in front of grand, aristocratic backdrops with “park-like pleasure-ground” and “lake-like prospect,” even though their “belongings and surroundings don’t warrant more than a little back-garden big enough to grow a few crocuses.”27 Cartes borrowed from the tradition of painted portraits, typically using luxurious furnishings and painted backdrops opening out onto imaginary properties. The carte de visite thus raised anxieties about the fakery of social class: gentility itself might ultimately turn out to be a combination of costumes and stage properties that could be easily simulated. Anxieties about the carte’s duplicity resonate with the recurring plotlines in sensation fiction where criminals counterfeit the appearance of respectability, or commoners impersonate more genteel characters. While sensation was seen as a phenomenon spreading from the bottom up, as it were, a disease caught from maidservants, cartes were imagined to move in the other direction, from aristocratic portraits of royalty down to working-class people in front of painted backdrops. But both kinds of cultural objects produced a class confusion surrounding persons and things.

The carte de visite often entailed an act of self-portraiture. Victorians had cartes made of themselves and then distributed them to friends, to be collected in albums and pored over during visiting hours. Geoffrey Batchen suggests that this vast, formulaic self-picturing has led modern art historians to disparage the carte de visite. Cartes, he writes, perhaps “too obediently embody the sensibilities, economic ambitions, and political self-understandings of the middle class”; in this sense, says Batchen, they might be said to represent “capitalism incarnate.”28 Walter Benjamin, too, in his “Short History of Photography” (1931), mocks the carte de visite for its “absurdly draped or laced figures,” photographs stuffed into a “thick photograph album” displayed on drawing-room pedestal tables in “the most chill part of the house.” He acknowledges his own appearance in one such album among a series of formulaic children, dressed “as drawing-room Tyroleans, yodelling and waving hats against a background of painted snow peaks”—as, for Benjamin, the whole phenomenon bespeaks “a sharp decline in taste” within the history of photography.29 While Benjamin’s gentle mockery is tempered by a sense of nostalgia, he ultimately agrees with Batchen’s assessment in denigrating cartes for capitalizing on a narcissistic kind of bourgeois self-love.

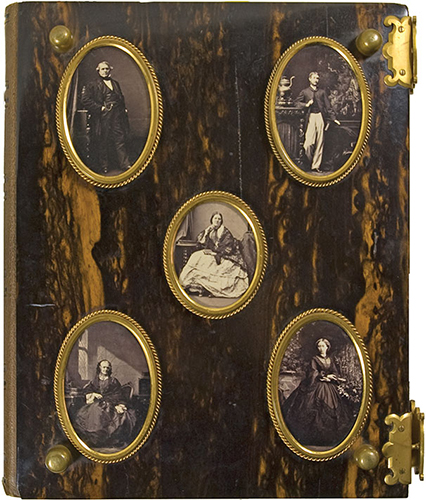

Yet cartes were notable for more than mere self-delineation. Victorian commentators focused on the carte de visite’s depiction of celebrities beyond the intimate circle of family and friends. “Cartomania” named the craze for collecting cartes of people one didn’t know, famous or notorious public figures constellating the world of gossip and conversation. The photo album on the drawing-room table served as a conversation piece for its collection of celebrity images, mediating between the parlor and the public sphere (Fig. 4.6). A critic in The Saturday Review described the parlor photo album as “at once a mild form of hero-worship and an illustrated book of genealogy. It does duty for a living hagiology, and it will supersede the first leaf of the Family Bible.”30 In fact, the ubiquitous illustrated Bible was itself becoming a commercial and worldly art production, as I argue in Chapter 3; but the comparison of photo album to family Bible neatly and ironically characterizes the way that cartes de visite portraits of public figures were creating a new kind of commercialized celebrity, a form of secularized star worship that had previously been reserved for notables in the religious sphere.

Fig. 4.6 Album cover with five portraits by Camille Silvy, c.1860. Gold-toned albumen prints mounted in oval brass frames. Wilson Centre for Photography.

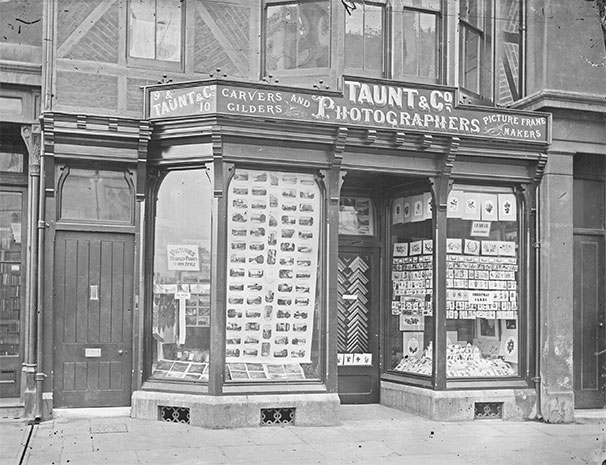

The mass-produced portrait found its perfect display venue in the photographic shop window, which attracted crowds eager to see cartes of politicians, priests, actresses, and courtesans (Fig. 4.7).31 Critics observed how these so-called “street portrait galleries” were admirably democratic; here, as one writes, “social equality is carried to its utmost limit.”32 Commentators dwelled especially on the way that shop windows or parlor albums juxtaposed cartes of incongruous celebrities. Descriptions of these odd mixtures are a humorous cliché and staple of cultural commentary in the early 1860s. Catholic bishops might appear cheek-by-jowl with Evangelical preachers, or respected politicans alongside actresses and criminals. The Daily Telegraph describes the photographic shop window as an outrageous side-by-side exhibition of “portraits of bishops, barristers, duchesses, Ritualistic clergymen, forgers, favourite comedians, and the personages of the Tichbourne drama … [alongside] tenth-rate actresses and fifth-rate ballet girls in an extreme state of dishabille.”33 In the cartes de visite album, writes the Saturday Review, “the ballet and the pulpit, the senate and the prize-ring, the haut-monde and the demi-monde are alike laid under contribution for portraits.”34 The rigidly divided and stratified Victorian social world became an alarming jumble in the photographic shop window or album, as both offered visions of a radically heterogeneous and mixed society.

Fig. 4.7 Henry W. Taunt, “Henry Taunt’s shop in Oxford,” c. 1874–94. Historic England Archive.

Critical fixation on the trope of unlikely carte juxtapositions amplified a progressive political rhetoric that had accrued to photography from its earliest beginnings. A comic song circulating in London in 1839 proposed that photography offered a radical, even revolutionary challenge to the precincts of British high art: “O Mister Daguerre! Sure you’re not aware/Of half the impressions you’re making,/By the sun’s potent rays you’ll set Thames in a blaze,/While the National Gallery’s breaking.”35 Even though photographs in 1839 did not yet easily circulate or reproduce, they were already seen to harbor the potential to ignite what Allan Sekula calls “an incendiary leveling of the existing cultural order.”36 Photography invited rhetorics of universality and democratization with its realistic, undiscriminating mode of representation and its increasing accessibility across the century—especially when compared with paintings, which remained mostly singular, expensive, and elite. No wonder, then, that critics used progressive political language to describe cartes de visite, especially in a decade leading up to the 1867 Reform Bill and the mass enfranchisement of working-class men. Carte photographs, arranged in an album or shop window, served as a useful platform for imagining a more leveled and horizontal social world—even if photography did not in any literal sense give rise to a more equal society.37

In fact, despite the persistent tendency of Victorian critics to portray cartes displays as a hectic visual mishmash, the reality was not the classless free-for-all that they described. As William C. Darrah notes, the carte’s early history was “marked by the patronage of royalty and nobility and the well-to-do, which bestowed respectability upon the inexpensive, mass-produced photographic portrait.”38 Aristocratic patronage of cartes subsequently waned as they became popular with bourgeois and working-class sitters. Juliet Hacking concludes that the history of photography in carte portraiture cannot therefore be seen as merely “a function of the rise of the bourgeoisie and of a teleological march towards democracy”—despite Victorian rhetoric to the contrary.39 Indeed, the carte album itself gave lie to the notion of equalization with its conventional arrangement of portraits: albums usually opened with cartes of royal figures and other celebrities before proceeding to portraits of friends and family.40 The carte album offered its owner the opportunity to lay out, in a specific, systematic format, the hierarchical shape of the collector’s known world. These facts suggest that the language of democratization surrounding the carte should be treated warily, even while—as we’ll now see—carte portraiture did allow certain new kinds of faces to enter the public sphere as part of a nascent mass media explosion.

The Girl of the Period

For many critics, the punchline in jokes about cartes displays often paired famous men with notorious women—prostitutes, actresses, murderesses, and other transgressors of Victorian female gender codes. In describing the “startling combinations” enabled by the carte album or shop window, critics allegorized social mixing through insinuations of women’s sexual sin or impropriety.41 Carte displays became especially sensational when they placed images of respectable gentlemen next to those of improper women. The 1864 poem “SENSATION! A SATIRE” complains of “A sweet republic, where ’tis all the same—/Virtue or vice, or good, or doubtful fame./ … Coarse ‘Skittles’ hangs beside a Spurgeon ‘carte,’/With stare, unblushing, makes the decent start./These are thy freaks, SENSATION!”42 Spurgeon was a noted British Baptist preacher, while “Skittles” was the nickname of Catherine Walters, a famous and successful courtesan known for her keen fashion sense and her affairs with powerful British men. Walters’s scandalous image was invoked ubiquitously in the early 1860s, in discussions of both cartes de visite and sensation novels—sometimes at the same time. As one reviewer of novels writes in 1863:

It is an unsatisfactory sign of the time when the photograph of an impudent courtezan [sic] is to be found among those of statesmen and bishops, and sells better than any of them; … [and] when a novelist in search of a sensation finds what he needs in this direction.43

The courtesan’s photograph, mixing boldly with those of statesmen and bishops, implies a kind of social leveling whose impertinent boundary-crossing is itself a kind of sexual congress.

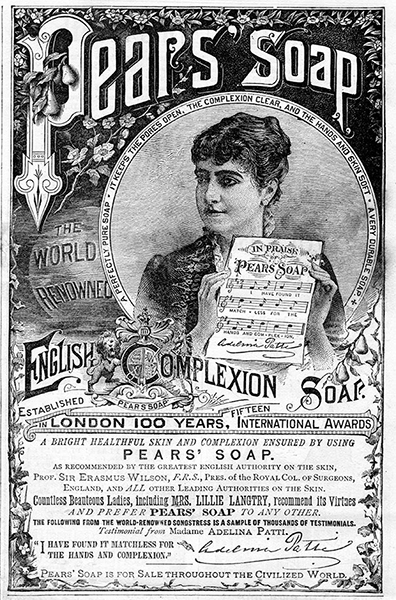

Despite Walters’s unseemly profession, she was also a marketing sensation, known for showing off her horse-riding prowess on fashionable Rotten Row in London’s Hyde Park, where she earned the suggestive nicknames of “Anonyma” and the “Pretty Horsebreaker.” Aristocratic ladies copied the tight-fitting cut of her riding habit and crowds gathered to watch her riding in the park, especially during the summers of 1861 and 1862.44 She seemed to hover somewhere between high fashion and ignominy. Her photographic portrait became, for her critics, a prime example of her brazen sins, making her the ultimate symbol of a degraded image culture.45 Certain conservative critics even accused Skittles’ photographers of making pornography:

[U]nfortunately the sensational taste which has of late invaded our literature and bids fair to degrade our stage, has also reached the photographer’s atelier. … [Photographs] which, if they had been exhibited in Wych-street, would … have been instantly confiscated by the police, are here displayed with a shamefacedness only too characteristic of the subjects which they portray.… One female aspirant of equestrian fame, … has allowed herself to be photographed in a costume which Lady Godiva would not have coveted.46

Wych-street, notorious for dens of pornography, here becomes a byword for the ambiance of illicit visuality hovering over the entire carte format. The carte’s combination of cheapness, miniaturization, and easy dissemination ensured that it would be conducive to pornographic imagery. Yet cartes of Walters in circulation today are surprisingly tame, showing a woman posed in costumes that are form-fitting but not too salacious (Fig. 4.8). The overheated descriptions of her picture seem to have been more rhetorical than literal. Walters’s recurring role in both sensation and photographic commentary speaks to more than just Victorian prudery: the courtesan or improper woman, shamelessly on view and up for sale, becomes a perfect metaphor for the rise of commercialism itself, when all that matters is buying and selling—a cash nexus that implies the disintegration of more traditional channels of power.

Fig. 4.8 Sergei Levitsky, carte de visite of Catherine or Clara Walters, alias “Skittles,” c. 1859–64. Courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library.

The ubiquity of Catherine Walters’s carte de visite likely inspired Eliza Lynn Linton’s notorious 1868 rant against “The Girl of the Period,” a caricature of outrageous female behavior that is a key document of the sensation moment. Linton assails the modern English girl for styling herself after a high-paid courtesan, scorning the role of wife and mother for the more selfish pleasures of money, clothes, and fast living. The Girl of the Period is a “loud and rampant modernization”; “[n]othing is too extraordinary and nothing too exaggerated for her vitiated taste.”47 Linton mourns the disappearance of the Anglo-Saxon girl of “innate purity and dignity … neither bold in bearing nor masculine in mind; a girl who, when she married, would be her husband’s friend and companion, but never his rival” (1). Instead, the Girl of the Period embraces “slang, bold talk and general fastness” and “the love of pleasure and indifference to duty,” displaying “dissatisfaction with the monotony of ordinary life” (5). While the essay does not mention cartes explicitly, it expresses anxieties about fashion, sexuality, image, and imitation that all seem apposite to the moment of mass photography:

The Girl of the Period envies the queens of the demi-monde far more than she abhors them. She sees them gorgeously attired and sumptuously appointed …. They have all that for which her soul is hungering; and she never stops to reflect at what a price they have bought their gains, and what fearful moral penalties they pay for their sensuous pleasures. She sees only the coarse gilding on the base token, and shuts her eyes to the hideous figure in the midst and the foul legend written round the edge. (5)

Linton’s metaphor of coinage, in which the modern girl desires the gold token without acknowledging its debased, graven female figure, perfectly captures the idea of a circulating image that is both potent and “foul.” Linton fittingly goes on to assail the modern girl’s imitation of prostitutes using metaphors of mechanical reproduction: “She thinks she is piquante and exciting when she thus makes herself the bad copy of a worse original” (9). And “after all her efforts, she is only a poor copy of the real thing; and the real thing is far more amusing than the copy, because it is real” (7). In other words, Walters’s photographic fame becomes a metaphor for the way that her example transforms good English girls into copies of her fiendish self. The demi-monde is reproducing itself to create a terrifying, artificial image culture, a world of female copies. While Linton attacks the superficiality of a type of modern female dandyism, her essay shows how women’s participation in a new image culture also posed profound threats to Victorian gender norms. The courtesan represented a freedom from patriarchal family structures; as Judith Walkowitz points out in her history of Victorian prostitution, sex work itself entailed surprisingly feminist overtones in allowing women a measure of economic freedom and self-determination in a society with a restricted female labor market.48 That a courtesan becomes one of the most-discussed figures in the carte de visite, then, points to more than mere squeamishness about sex. Walters becomes the sign of a new, problematic kind of female self-making.

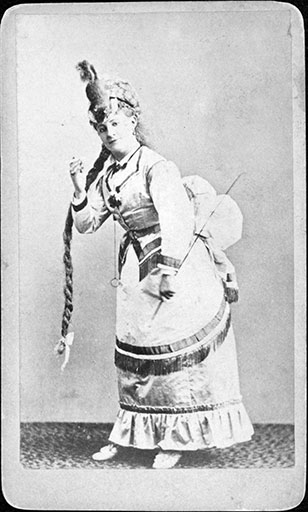

The brilliant snarkiness of Linton’s essay propelled it into its own hugely popular phenomenon, spawning “Girl of the Period” periodicals, parasols, waltzes, satirical lithographs and—coming full circle—cartes de visite. While some of these commodities adopted Linton’s anti-feminist attitude wholesale, others took a more light-hearted or even sympathetic approach.49 Photographs of the Girl of the Period (Fig. 4.9) depict Lydia Thompson, a successful burlesque performer, in the familiar costume with its mock-feminist accoutrements of monocle, cigarette, long braid, ridiculous squirrel-skin hat, and leather riding crop—making this figure a prototype of the New Woman, with her athleticism, smoking, and unusual fashion choices signifying a defiant femininity. The riding crop, in particular, aligns the Girl of the Period with other powerful horsewomen of the 1860s, including Catherine Walters.50

Fig. 4.9 Carte de visite of Lydia Thompson as “The Girl of the Period,” c. 1868. Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library.

No surprise, then, that versions of Walters—as the prototypical dominant, erotic, and spectacularized woman—appear in the sensation fiction of the early 1860s. Walters’s story parallels that of Lady Audley in M. E. Braddon’s 1862 sensation novel Lady Audley’s Secret. Both women are seen as having illicit power over respectable, wealthy men: Walters uses her sexual wiles to procure male patrons and even gets one to run away with her to America, while Lucy Graham entices kindly Lord Audley to fall in love with her and marry her so that she can become a “Lady.” Of course, as we learn in the novel, she’s also a bigamist, already married to another, less lordly man. Lady Audley uses her beauty to impersonate a high-class woman; the novel emphasizes her persona as a visual one by lavishing attention on her painted portrait, done in a garish, Pre-Raphaelite style. The painting itself becomes a plot point when it enables her first husband to recognize her true identity. While the life-sized, technicolor painted portrait seems very different from a hand-sized, black-and-white photographic carte de visite, both images present a scandalous female visibility in the form of full-length portraiture.51 Lady Audley’s portrait in fact approaches the carte de visite by virtue of its own mediation: it is not a painting but an ekphrastic reproduction, an image rendered in words that circulates via mass print in novel form. The visual culture of sensation presents mediated female spectacles which gain a fearsome power through both sexual display and a dominant mass visibility.

The notorious Catherine Walters also haunts the margins of M. E. Braddon’s sensation novel Aurora Floyd (1863). The novel stars a powerful horsewoman who defies standards of femininity in her preference for tomboyish, horsey pursuits—which include a cross-class marriage with a groom. Braddon generates sympathy for a heroine who dangerously courts female showmanship, a tendency inherited from her actress mother:

Aurora was her mother’s own daughter, and had the taint of the play-acting and horse-riding, the spangles and the sawdust, strong in her nature. The truth of the matter is, that before Miss Floyd emerged from the nursery she evinced a very decided tendency to become what is called ”fast.”52

“Fast” girls, precursors to Linton’s Girl of the Period, combine an unfeminine love of speed with a desire for thrills, a combination inevitably fraught with sexual innuendo. I discuss further below how actresses featured as key figures in sensational cartes de visite; for now, it is enough to note that Aurora’s performative nature, her staged sexuality mingling “the spangles and the sawdust,” aligns her with other scandalous horsewomen on view in the early 1860s. In the novel’s most infamous scene, Aurora punishes a servant who has kicked her beloved dog by brutally horsewhipping him—a scene that identifies her literally with the “Pretty Horsebreaker,” the courtesan who tames men using her sexual dominance.53

While the female body on display might have suggested a muted woman, disempowered and objectified as a visual commodity, these erotic female spectacles instead pointed in the opposite direction, intimating to Victorian viewers a wild sexual license and cultural dominance. A woman on view might claim an aggressive and illicit power over her spectators: she was, in a sense, both purchaser and purchased. Sensation’s powerful erotic woman operated within an ostensibly heterosexual paradigm—exerting her power over intimidated or ensnared men—but this female figure also spoke alluringly to a female audience. Indeed, the spread of sensationalism was often portrayed as a taboo erotic transaction between women. Reviewers of sensation novels often worried about the effects of the indecent literature on female readers:

[W]hat the mamma reads the daughter also will read, so that the romantic poison, if poison it be, finds its way all through the household, as well as into the mistress’s boudoir; for Miss tells her maid, who tells the housemaid, who tells the cook—and all pant over the forbidden page by stealth.54

If sensation novels were figured as a contagious disease infecting readers, then women were seen to be especially susceptible, prone to the degenerate copying of the immoral female behavior depicted inside the novels. Likewise, cartes photographs also circulated within the province of women: not only were they featured in the feminized parlor album, but also, as Juliet Hacking notes, the majority of cartes patrons and sitters were female.55 When Catherine Walters reigns in cartes iconography, then, we can understand why Eliza Lynn Linton worries about her influence on other women—an influence whose media effects intimated illicit homoerotic bonds between women.

Ghost, Copy, Self: The Woman in White

The themes of female visibility, portraiture, and copyism discussed in this chapter come to the fore in Collins’s sensation novel The Woman in White. The novel’s meditations on these subjects are not focused around the medium of photography, and cartes de visite make no appearance in the novel. Yet the novel organizes itself around a series of repetitive female portraits, as it investigates the paradoxes surrounding female character and female exceptionality. These explorations focalize the novel’s larger political interest in the conundrum of the individual’s relation to the mass, a problem, as I’ll show, that the rhetorics of mass portrait photography also circled, without clear resolution.

The Woman in White announces its visual interests in the occupation of its protagonist, Walter Hartright, who serves as a drawing-master in a grand house. The novel portrays humble Walter’s rise to become the house’s owner, while the aristocrats scheming against him receive their just downfalls—a trajectory bespeaking strongly middle-class values. At a low point in the novel, when the main characters are forced to assume a working-class disguise, Walter becomes an anonymous engraver for cheap illustrated newspapers. William R. McKelvy argues that Walter’s engraving work proves the novel’s democratic sensibility, as it shows “an aggressive faith in the industrial arts.”56 Yet the novel’s depictions of new visual media are not clearly democratic. Walter’s furtive work in graphic design, published anonymously, opposes the novel’s broader investment in a good name, reputation, lineage, and class propriety. By the end, he has escaped his demeaning engraving work to ascend as the fitting proprietor of Limmeridge House.57 His high-art, aesthetic sensibility suits him for this genteel role, as evidenced by his identity as a drawing master well-versed in the singular arts of painting and watercolor.58 Meanwhile, photography is the province of the villainous aristocrat and aesthete Mr. Fairlie, who makes photographic reproductions of his beloved art collections in a narcissistic act of self-promotion. If anything, the novel shows how the newer reproductive arts might work hand-in-hand with older, more singular kinds of artworks to promote hierarchy and social order. These conservative investments reflect the way that sensation itself, in both novels and photographs, existed uneasily alongside the language of “democratization” that critics applied to it—as a greater accessibility to mass arts emerged in what was still a highly unequal, hierarchical, and undemocratic society. The Woman in White gains affective energy from this conflict between hierarchy and democratization, mining the conflict in order to generate a sensational story, in particular through its use of the female portrait.

Collins’s novel offers a vexed politics of vision in its numerous portraits of women. A watercolor portrait of Laura launches Walter’s retrospective narration: this image is just one of a surfeit of female portraits, an excess that highlights the novel’s difficulty in characterizing women. Female characters are repeatedly transformed into image, often in scenes of sensational, spectacular display. The framing and flattening of women into pictures enables the persistent doubling, exchange, even interchangeability among certain female characters. When Walter first beholds the woman in white on a nighttime road to London, he describes the scene as a visual spectacle:

There, in the middle of the broad bright high-road—there, as if it had that moment sprung out of the earth or dropped from the heaven—stood the figure of a solitary Woman, dressed from head to foot in white garments, her face bent in grave inquiry on mine, her hand pointing to the dark cloud over London, as I faced her.59

The sudden appearance of the ghostly figure is theatrical but also pictorial, a moment of splendid visual pause, almost a tableau vivant, as the whiteness of the woman’s clothes leaps out against London’s dark cloud. Walter’s narration nervously reflects the aura of illicit sexuality looming over the event, as he is solicited by an unknown woman on a public road at midnight.

This initial encounter is the first in a series of striking pictorial tableaux aligning women with an image culture that is both sensational and repetitive. When Walter realizes that Laura Fairlie is the spitting image of his mysterious stranger loosed from the asylum, the realization comes in the form of another picture, as Laura stands poised on the evening terrace:

There stood Miss Fairlie, a white figure, alone in the moonlight; in her attitude, in the turn of her head, in her complexion, in the shape of her face, the living image, at that distance and under those circumstances, of the woman in white!

The dramatic white spotlight of moon creates a sense of sculptural pause, setting Laura off as a “living image” against the dark evening. Laura’s existence as a living image, a copy of the woman in white, resonates problematically throughout the book: as the plot twists inexorably exchange Laura for Anne, resulting in Laura’s dispossession of her fortune and her sense of self, their interchangeability seems highly dependent upon the way that they have both appeared in the novel as a series of pictures. If sensation novels are known for inspiring hair-raising thrills in both characters and readers, these exciting moments of female pictorialism suggest that nervous response is inspired by a radical female visibility, encapsulated in the image. The female portrait presents an eroticized white body that triangulates desire between reader and spectating character.

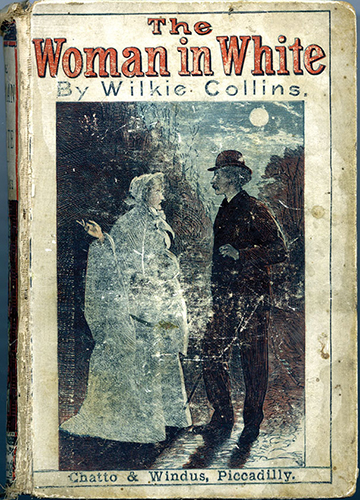

Whiteness itself in the novel becomes a sign of female interchangeability and, unexpectedly, sexual immorality. White alludes to innocence, virginity, Englishness, and skin (or what the novel repeatedly refers to as a “fair complexion.”) But it is also an improper color for a woman to wear outdoors, intensifying the sensations inspired by the female apparitions. White clothes were considered especially appropriate for young women and girls, connoting interiors and domesticity.60 All the more shocking, then, when Anne Catherick appears on the night road in the novel’s dramatic early scene wearing the white uniform of an asylum inmate. Her clothes signify a domesticity that is startlingly transported outdoors, turned inside out; whiteness heightens the effect of a transgressive female public visibility that iterates across the novel. Collins’s publishers cannily chose Walter’s nighttime confrontation with the white-clad Anne for the book’s cover illustration in numerous editions (Fig. 4.10). Sensation engages in a Victorian marketing campaign that packages an erotic whiteness for ready consumption, linking interchangeable women with the mass production of commodities, including books. No wonder that The Woman in White inspired commodities targeted at the boudoir, such as toiletries, perfumes, and, of course, white dressing gowns.61

Fig. 4.10 Illustrated cover for The Woman in White “yellowback” edition, published by Chatto & Windus, 1889. Courtesy of the collection of Andrew Gasson.

The novel’s parade of female “living images” suggests a problematic relationship between appearance and identity. When Laura starts to lose her identity, eventually to be transformed into Anne, the novel threatens to suggest that image is everything—at least, when it comes to Laura’s type of femininity. Sensation’s vexed engagement with “The Woman Question” manifests in the novel’s contradictory attitudes toward female empowerment. Collins’s novel promotes a familiar Victorian female type in Laura, demure, modest, self-effacing to a fault, and so weak that she almost begins to believe that she is another person. She offers a striking contrast to her sister, Marian, whose unique look combines darker skin and a masculine moustache with a strong female personality. Though Marian represents a more unusual, heroic feminine type, the novel ultimately relegates her to the role of spinster, while elevating Laura as Walter’s romantic love interest and feminine ideal. The Woman in White thus takes an ambivalent stance about the extent to which women should be original, unique, and nonconformist. The same issue is inherently raised by mass photography, especially as it enabled women like Catherine Walters to make their names.

Observing the trouble with female conformity in Collins’s novel helps us to understand the dialectical relations defining the sensational photograph, as the pictured woman wavered between mere copy and extraordinary individual. To be “extraordinary,” in our contemporary lexicon, connotes a marvelous originality. But for Victorian commentators, writing within a culture that prized female obedience to gender norms, to be extraordinary was to invite negative attention and even public censure. The extraordinary, like sensation itself, bordered on the freakish and the weird. Thus Linton’s Girl of the Period is distinguished by her “vitiated taste” for the “extraordinary,” while Robert Audley declares Lady Audley’s portrait to be “an extraordinary picture.”62 Walter Hartright regards the white-clad Anne Catherick as an “extraordinary apparition”: the word “extraordinary” appears in The Woman in White more than fifty times. The extraordinary shares similarities with the famous, as both concepts, though valued today, possessed darker meanings for nineteenth-century critics. Fame is not that different from infamy when it comes to the Victorian woman appearing in public, opening herself up to comment, visibility, and exposure.

To be extraordinary is to stand out from the crowd, to be original, different or unusual. When Catherine Walters becomes the epitome of daring style, however, she also becomes someone whom other women copied. The doubtful qualities obtaining to the “extraordinary” seem appropriate to the ambiguities of a decade when people were debating mass enfranchisement, questioning the rights of the one versus the many, and wondering about the benefits of being an original versus being a follower. John Stuart Mill defends individual liberties against the “tyranny of the majority” in 1859, right on the cusp of the sensation phenomenon. Eliza Lynn Linton courts contradiction when she attacks the Girl of the Period both for being attracted to the “extraordinary” and for servile copyism of the demi-monde.

A similar confusion governed the production of mass photography: everyone was doing it, yet certain persons became famous and collectible in the carte—one of the nineteenth century’s typical, yet paradoxical, combinations of exceptionalism and democratization. On the one hand, carte culture fueled a Victorian cult of the original self. The realism of photographic portraiture, one critic observed, reproduced “the very lines that Nature has engraven on our faces” such “that no two are alike.”63 Many rhapsodized on the ability of the best carte portraits to “show the soul of the original [sitter]—that individuality or selfhood, which differences him from all other beings, past, present, or future.”64 An 1863 article on the carte de visite was aptly titled “The Philosophy of Yourself.”65 The collectible portrait photograph would seem to define par excellence the visual culture of liberalism, enshrining the singular face.

Yet these hymns to individualism emerged against the backdrop of photography’s vast industrialization and its acutely conventional, middle-class visual style. Geoffrey Batchen concludes that cartes photography “is all about the semiotics of typology and the sublimation of the individual to the mass.”66 This assessment seems rather sweeping, given the celebrity culture surrounding the carte. Batchen’s art-historical sensibility perhaps leads him too quickly to dismiss the distinctive qualities attributable to a mass-produced item. After all, carte portraits would have been quite particular and diverse to the people who collected them. Though the similarity of pose and costume today might make these images blur together, Victorian viewers would have recognized the persons being photographed, whether celebrities or friends, creating a specific and unique viewing experience—just as, today, the mind-numbing repetitiveness of modern social media does not prevent our lingering over its platforms to observe the minutiae of small differences among our “friends.” Rather than seeing cartes photography as formulaic, flat, and perfectly interchangeable, as Batchen does, my analysis sees the carte de visite as part of a larger sensational dialectic invested in both extraordinary individuals and a democratized mass. The celebrity carte pushed these contradictions to an extreme, as a person gained a singular name and a distinctive image through the reproduction and sale of thousands of exactly the same picture. Wilkie Collins’s novel The Woman in White helps to explain why women’s photographs, in particular, focalized this dialectic: the constraints of Victorian female gender roles made female conformity into both a desirable mandate and a fraught cage, states of being that the novel dramatizes via the divergent femininity modeled by its two female protagonists—one a formulaic beauty and the other an extraordinary heroine.

The Actress, the Diva, the New Public Face

The power bestowed by the carte de visite heralded a new kind of celebrity, one based on image, notoriety, and a fleeting kind of fame familiar to us from today’s tabloid culture. “No man, or woman either, knows but that some accident may elevate them to the position of the hero of the hour, and send up the value of their countenances to a degree they never dreamed of,” writes one 1862 critic of the carte de visite.67 Unlike the English class system or political system, the carte system of value depended only upon a fame of the hour. By this free-market standard, a courtesan might be “worth” just as much as a bishop. In the sensation economy of the carte, image was everything—especially the erotic or sexualized image of morally questionable women. A carte’s value was assigned only by its exchange value on the capitalist market, equalizing and standardizing all figures within the image and format.

The types of female fame available in the carte are catalogued, humorously, by Jane Carlyle in an 1865 letter to her husband as she marvels at her own appearance in a photographic shop window: “[F]or being neither a ‘distinguished authoress,’ nor a ‘celebrated murderess,’ nor an actress, nor a ‘Skittles’ (the four classes of women promoted to the shop-windows) it can only be as Mrs Carlyle that they offer me for sale!”68 Carlyle’s comment is funny because it reproduces the logic of interchangeability implied by the carte format: as photography lines up female bodies in a row, in similar dimensions and poses, a woman writer might become transposable with a courtesan or a female murderer. As Carlyle implies, any female fame might carry the taint of scandal because a woman’s image for sale, combining femininity and commercialism, would inevitably connote prostitution for many Victorians. Yet despite the disreputable tinge to female public visibility, Carlyle’s bemused pride suggests that celebrity itself was not completely unwelcome.

That photography captured portraits of many respectable, highly placed individuals in the Victorian world highlights its status as a mixed medium: the carte de visite traced its roots back to venerable painted portraits of the eighteenth century, even while offering a more intimate, modern view in mass-produced format. Photographic historian Christopher Pinney suggests that carte portraits have antecedents in eighteenth-century “swagger portraits,” images that elevated “public display” over “the more private values of personality and domesticity.”69 Associated with continental European painters such as Batoni, Van Dyck, and Winterhalter, the “swagger” genre emphasized the sitters’ “glamour and theatricality.”70 Unlike Rembrandt’s portraits, which probed the depths of sitters’ souls, these portraits instead offered a brilliant exteriority:

We are in the realm of theatre—elaborately coded fictions. The silks, satins and taffetas worn by these men and women, the ermine, braid that artists painted with such finesse and brio, are not clothes so much as costumes: signals of rank.71

Batoni’s portrait of Princess Ludovisi (c. 1758) abounds with rich textures of velvet, lace, fur, and sparkling gems, attesting to the performed rank of the sitter (Fig. 4.11). These signs also blend with the trappings of high art—marble bust, neoclassical pillar, harpsichord, lyre, and poet’s wreath. The symbolic items testify to the princess’s artistic accomplishments, while also affirming the portrait’s own aesthetic aura.

Fig. 4.11 A “swagger portrait”: Pompeo Batoni, Portrait of Princess Giacinta Orsini Buoncampagni Ludovisi, oil on canvas, c. 1758. The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo.

The swagger portrait served as the recognizable template for the cartes de visite of aristocratic ladies such as those taken by Camille Silvy, often considered the greatest cartes photographer.72 Known in the 1860s as the major portraitist of the British upper classes, Silvy’s cartes depicted women in exquisite gowns, posed in rooms lavishly decorated with furniture, tapestries, and art objects. His “Beauties of England” series (1862–3) offered cartes of women at the height of Victorian society, posed with rich accoutrements and elaborate painted backdrops in visual codes that reached directly back to the eighteenth century. Silvy’s carte de visite of the Duchess of Wellington imitates a painted swagger portrait, directing the eye to the impressive, textured folds of her dress and the fine lacework of her shawl (Fig. 4.12). The photo conspicuously rehearses the visual formula of Batoni’s Princess Ludovisi portrait, positioning the woman amid neoclassical sculpted pillars and vases, and setting her before a landscape scene stretching off into the distance. Silvy’s photograph, however, perhaps unwittingly highlights the artifice of Batoni’s formula: the “landscape” opening out beside the photographed woman is a painting, rather than a window, and the neoclassical vase and pillar above her shoulder appear to be cardboard cutouts. Batoni’s painting itself assembles a neat arrangement of faux visual signifiers that likely did not coexist in life: the landscape backdrop is not a realistic window view so much as a symbol of the princess’s privileged relation to property. The clear artifice of the painted portrait tradition likely explains why Silvy’s carte, with its patently false cardboard props, still conveys an aura of gentility and aesthetic conviction—an aura that only flickers upon close scrutiny of the image.

Fig. 4.12 Camille Silvy, Carte de visite of the Duchess of Wellington, 1860. The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography.

While the painted portrait consolidated its auratic status in the nineteenth century, eighteenth-century portraits were not themselves uniform signifiers of privilege and gentility. In fact, some of the century’s most famous portraits depicted women with more daring or lower-class backgrounds. British actresses, in particular, used portraits to wage publicity campaigns to further their careers. Joshua Reynolds’s famous portrait, Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse (1784) (Fig. 4.13), gained tremendous renown and played a definitive role in transforming Sarah Siddons into what Judith Pascoe calls “the most public woman of the day.”73 Reynolds’s painting was still ubiquitous in the Victorian visual lexicon almost a century later, as seen when a carte de visite critic alludes to it—in this case, mocking a photographer for forcing a working-class female sitter “to take upon herself a Siddonian mien, as though just uttering the words, ‘Give me the daggers!’”74 Siddons’s portrait here signifies an uncontested high culture, but the original painting itself was more mixed and ambiguous: it invoked the high arts of ancient tragedy and Shakespearean drama while limning an actress who performed live theater on a London stage. The scandalous sight of the actress’s displayed body is contained by the painting’s exalted historical framework, expressed in the woman’s grand gesture.75 Scholars have documented how Siddons used portraiture to elevate her status to that of great tragedienne, laying claim to a respectability that was always under threat given the long-standing ties of actresses to prostitution.76 Shearer West writes that eighteenth-century actresses were subjected to what she calls a “body connoisseurship,” “a kind of scrutiny of the body which could displace or confuse lustful voyeurism with cultivated admiration.”77 The actress portrait therefore epitomized the actress’s uneasy oscillation between lofty idealization and ignoble embodiment. Siddons sat for more portraits than any other actress of her age, using painting as a key instrument to fashion a nascent form of modern celebrity.78

Fig. 4.13 Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse, 1784. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, CA, USA. © The Huntington Library, Art Collections & Botanical Gardens/Bridgeman Images.

The eighteenth-century swagger portraits or actress portraits, with their performative, exaggerated styles, found their inheritors in the photographic celebrity carte, especially those depicting female actresses and opera singers. These cartes epitomized sensational photographs, with their fleeting popularity and frank complicity with female theatrical display. While a singular, painted portrait might seem starkly different from a mass-produced, ephemeral photograph, both were engaged in the theatrical task of portraying a public face, creating the familiar, recognizable façade of the body. And, like their painterly forebears, actress cartes also used mixed effects from both high and low culture to create the female portrait. Sensation’s transgressions in the social and sexual realms also expressed themselves aesthetically, contravening the expected bounds of form and artistry. (Aesthetic confusion similarly governed the reception of sensation novels—as when reviewers of Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White were flummoxed by the novel’s combination of melodramatic elements with an innovative and intricate plot structure. The novel thus served as a controversial site for debating what constituted high art versus mere entertainment.)79 Sensational objects were both titillating and aesthetic, artforms themselves unmoored from traditional understandings of value.

These confusions are evident in the theater cartes of Camille Silvy, who first made his reputation in England by photographing actresses and opera singers.80 His carte de visite portraits of the opera star Adelina Patti in the early 1860s sold more than 20,000 copies.81 An arresting 1861 photograph of Patti cultivates aspects of both gentility and sensation (Fig. 4.14). She wears an elaborate dress like those seen in cartes of aristocratic ladies, but she also appears among stage props that include a fake tree, a painted backdrop of a forest, and a taxidermied dog. Her open mouth and flirtatious pose pretend to catch her onstage, mid-aria, yet the scene has clearly been staged in the photographer’s studio. Silvy’s 1860 carte of Rosa Csillag as Orfeo similarly offers both high-art and sensational cues (Fig. 4.15). Csillag bears all of the familiar tokens of Orpheus, mythical master of music, with her lyre, toga, and crowning laurel. The mis-en-scène presents ruined arches and broken pillars—ruins that speak less of classical Greece than of neoclassical Old Master paintings, as well as a Romantic aesthetic privileging the fragment. Yet these high-art signifiers gain a frisson in the figure of Orpheus herself, a woman performing a man’s role, combining masculine toga with revealing tights and ballerina’s slippers.

Fig. 4.14 Camille Silvy, Carte de visite of Adelina Patti as Harriet in Friedrich von Flotow’s opera Martha, 1861. Bequeathed by Guy Little. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Fig. 4.15 Camille Silvy, Carte de visite of Rosa Csillag as Orfeo, albumen print, 184 × 117 mm, 1860. Private collection, Paris.

Both of these cartes point to the special role played by actresses in creating new forms of Victorian celebrity. To a much greater extent than in the eighteenth century, when Sarah Siddons reigned as the Tragic Muse, the Victorian world celebrated a passive, domestic, middle-class feminine ideal—one that the female performer contravened, despite her attempts to present herself as modest and familial. The actress’s “public existence seemed to preclude private respectability,” writes theater historian Tracy C. Davis: actresses challenged patriarchal norms in ways that resulted in their “social ostracism and vilification.”82 Victorian prejudices that linked acting to prostitution, Davis notes, went beyond the mere fact that both traded on the female body, offered in public for money. More fundamentally, both careers allowed women a rare economic self-sufficiency: “[N]o other occupations could be so financially rewarding for single, independent Victorian women of outgoing character, fine build, and attractive features.”83 The actress onstage could command the gaze of an audience and hold it spellbound with her words. It is no coincidence that sensation narratives featured women with backgrounds in stage acting, while also favoring villainesses who were adept at nefarious forms of role-playing. The actress carte, then, like that of the powerful courtesan, also participated in a kind of female self-making, one that played upon the availability and visibility of the female body to create a brand and a career.

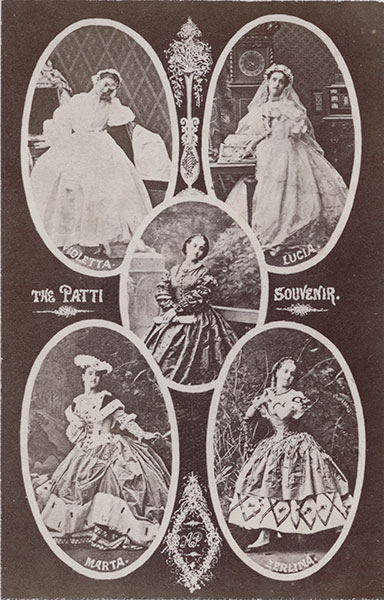

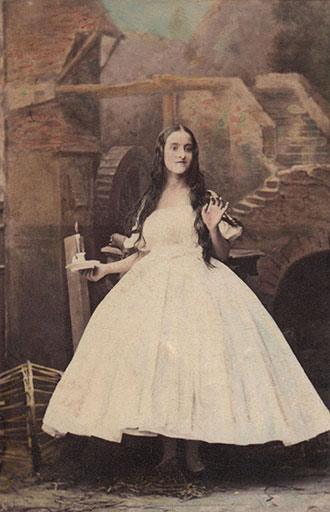

While photographic portraits as a genre always entail a kind of performance, cartes of Victorian actresses literalized and amplified that fact, with details of costume and pose creating a fantastical, desirable, and collectible persona. A single actress often appeared across a variety of cartes, staged in a phantasmagoric, mutable array of costumes, props, and settings. The opera singer Patti was featured in a carte series by Silvy documenting the six roles she performed at the Covent Garden Italian Opera in 1861, when she made her triumphant London debut at age nineteen. A carte “souvenir” offered a medley of those images, set off in oval frames, showing Patti as Lucia, Zerlina, and other leading operatic ladies (Fig. 4.16). These cartes are highly staged, ornamented, and narratively expressive. Critics used the language of high art and musicality to review Patti’s performances, but her portrayal in actress cartes shows how her performance was contiguous with other sensational female phenomena, reflecting the opera’s mixture of musicianship and eroticism.84 In one of her famous 1861 roles, captured by Silvy, Patti played Violetta in Verdi’s 1853 opera La Traviata—a work whose title literally translates as “the fallen woman” and whose story features a beautiful young courtesan who dies of tuberculosis. (By the early 1860s, a “traviata” was a slang term for a prostitute—a term applied, predictably, to Catherine Walters in the poem “Sensation! A Satire.”)85 Perhaps owing to the racy subject-matter, Patti’s Violetta in Silvy’s carte de visite appears perfectly chaste, costumed in a modest, high-necked white gown amid a domestic interior. By contrast, her portrayal as Amina, in Bellini’s La Sonnambula, is more daring: Silvy’s carte depicts her in the opera’s climactic scene, as the white-clad Amina—suspected of immorality after having been discovered in a Lord’s bedroom—unwittingly proves her virtue by sleepwalking over a treacherous, derelict bridge in front of gathered townspeople (Fig. 4.17). This carte seems especially apropos of the sensation moment, with its girl costumed in an ankle-baring white dressing gown, carrying a suspenseful candle, standing before a painted backdrop depicting the old mill wheel and the crumbling bridge. As in Wilkie Collins’s Woman in White, the imperiled heroine thrills with a risqué appearance in a white nightgown, outdoors, in public, at night.86

Fig. 4.16 Ashford Brothers & Co., “The Patti Souvenir.” Carte-de-visite medley of photographs of the opera singer Adelina Patti taken by Camille Silvy, c. 1861. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Fig. 4.17 Camille Silvy, Hand-tinted carte de visite of Adelina Patti as Amina in Bellini’s La Sonnambula (The Sleepwalker), c. 1861. The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography.

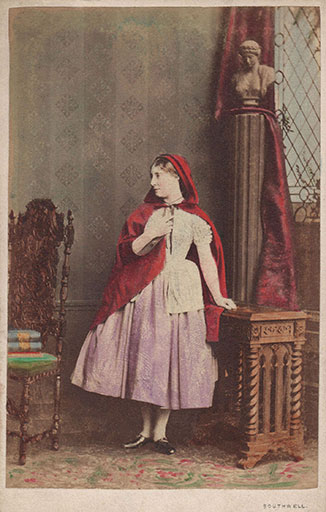

Despite Patti’s high-art status as an opera diva, her cartes de visite adhere to the formula for actress cartes of all types, combining alluring costumes with scenes of high narrative suggestiveness. A similar formula governs the image in a carte depicting Lydia Thompson as the heroine in a version of The Colleen Bawn, the most sensational of the 1860s sensation dramas (Fig. 4.18). Thompson is costumed in Eily O’Connor’s iconic red cloak, its color apparent in the carte’s hand-tinted version. (The red cloak predictably became a fashionable commodity in the wake of the play’s success.)87 Yet despite the carte’s sensational subject-matter, the image is surprisingly artful in portraying the actress amid the conventional portrait furniture of neoclassical pillar, rich drapery, even a classical bust. These respectable tokens are especially incongruous given that Thompson was starring in a burlesque adaptation of Boucicault’s play, in what was an even less reputable version of an already suspiciously “low” genre.88 There is little to distinguish Thompson’s carte from those of Patti in her operatic roles, with the exception of the length of the woman’s skirt. All of these images suggest that the actress herself had something in common with the photographic carte, as both hovered ambiguously between sensation and respectability, commerce and art, the body and the pose.

Fig. 4.18 Hand-tinted carte de visite of Lydia Thompson as Eily O’Connor in The Colleen Bawn Settled at Last, c. 1862. The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography.