6

Decadence

Consuming Decadence: Advertising and the Art Poster

Visual Cultures of Decadence

The art poster was a new and controversial kind of advertisement that began to appear on urban streets and hoardings in Britain in the later 1880s and 1890s. Partaking of both art and capitalism, the art poster infused an aesthetic sensibility into the use of images to sell objects and events within a vastly expanding consumer culture. Some artistic posters transformed paintings directly into advertisements—as in the case of “Bubbles,” when J. E. Millais’s 1886 painting of a boy blowing bubbles became a famed chromolithograph for Pears’ Soap. Other art posters, however, took an approach to commodities that was more provocative and mysteriously avant-garde, with human figures stylized in stripped-down renderings that challenged realist conventions. Aesthetic confusion surrounded art posters from their earliest days: they were mass-produced, disposable, and advertised commodities like cocoa and the circus, but they also starred in major art exhibitions in London and Paris and were attacked for their “decadent,” avant-garde styles. Scholars of the fin-de-siècle countercultural art movement known as decadence have not studied these images, which is unsurprising, given that advertising posters would seem to embody the mainstream middle-class commercial culture that decadence opposed. Yet this chapter will argue that the poster arts in the 1890s were a major vehicle for decadent visual style, as well as a proving ground for decadent philosophy. The new techniques of late-Victorian visual advertising mirrored a decadent understanding of the subject engaged in radical acts of self-making through aesthetic, consumerist choice.

Decadence has usually been understood as a literary phenomenon. The foundational study establishing its stylistic and thematic qualities was Désiré Nisard’s 1834 critique of Latin poetry from the late Roman empire. Nisard aligned Roman decline with a decadent poetics of perverse sensuality, erudite allusiveness, and elaborate language.1 Twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholars have continued to focus on literary works as the major vehicles for decadent aesthetics, looking to a constellation of European writers that includes Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, and Joris-Karl Huysmans.2 In Huysmans’ 1884 novel À Rebours, known as the “breviary” of decadence, the book’s extravagant literary style reflects the protagonist’s subversive values, as he shuts himself away in a château to engage in taboo forms of experimentation and sensation-seeking. In the present day, most studies of decadence have focused on poetry and a few artful fictions, taking linguistic virtuosity as the foremost sign of a radical aesthetic counterculture.3

Yet in the 1880s and 1890s, as this chapter will argue, decadence connoted a broader set of practices and rhetorics beyond the linguistic. For progressive or experimental artists, a visual culture of decadence looked toward techniques of visual modernism—foregoing explicit narrative or moral messaging in favor of arresting color or shape, flattened picture planes, and an anti-humanist aesthetic making human figures into the bearers of pattern or form.4 This visual style challenged Victorian norms by refusing to affirm middle-class moral values. For this reason, decadence came to coincide with the poster arts, as posters used these techniques to catch the eye in the busy, urban visual field. The “art for art’s sake” movement of the 1860s and 1870s was appropriated by advertisers to sell products to passersby on the street. While the Aesthetic movement before decadence had already embraced commodity culture by cultivating a popular vogue for home décor, the decadent poster arts took commodification to an extreme, merging together artwork and advertisement.

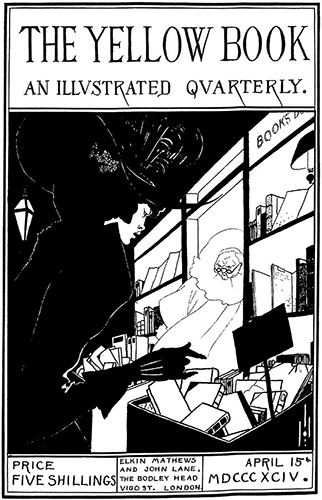

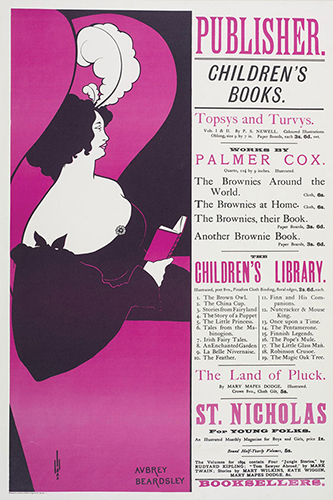

The visual aspect of decadence has its canonical representative in Aubrey Beardsley, the art editor of The Yellow Book, whose subversive, unusual style came to epitomize late-Victorian avant-gardism for a scandalized public. Beardsley has typically been construed through the lens of a high-art sensibility: today he is most well-known for illustrations to esoteric literary works like Malory’s Morte d’Arthur and Wilde’s Salomé.5 Discussions of Beardsley’s work as a decadent illustrator rarely disclose his identity as a poster artist, perhaps reflecting the way that the poster arts fall between the gaps of our current disciplines.6 Yet in his own time, it was Beardsley’s posters that brought him most visibly into the public gaze, along with his designs for a variety of periodicals. Beardsley’s early death at the age of twenty-five did not prevent his style from becoming a shorthand for decadent vision in the Victorian popular imagination, and indeed it remains such today. While Beardsley has been normalized as a key contributor to the decadent canon, alongside poets and novel-writers, this chapter will work to defamiliarize his presence by emphasizing his exceptionality. Beardsley was not a painter, nor a member of the Royal Academy; he was a graphic designer, an unabashedly commercial artist, working in the Victorian new media of color lithography and photomechanical reproductions. He used advertising posters to make statements about art and aesthetics: in fact, he made the art poster itself into a kind of manifesto, glorying in the shock value of merging experimental art with blatant mercantilism. Decadence appears differently when we observe that its representative visual artist produced works aimed for the street and the marketplace, engaging directly with the world of middle-class commercial culture that the movement was ostensibly rejecting. Beardsley used a mass-market visual aesthetic to propose a new idea of art’s relation to commerce, making avant-gardism itself into a commodity.

These connections between decadence and advertising will seem unlikely, given our usual sense of the art movement as an elite high culture opposed to middle-class values. Richard Dellamora writes that decadent critique is “always radical in its opposition to the organization of modern urban, industrial, and commercial society.”7 In À Rebours, Des Esseintes scorns “these merchant minds, exclusively preoccupied with the business of swindling and money-making.”8 He mocks the bourgeois taste for nature-based aesthetics, preferring instead his own refined, idiosyncratic aesthetics generated out of rare art objects and obscure literary works. Decadence showed multiple investments in high culture, with its array of aristocratic characters and collections of precious objects. Yet the fetishization of wasted aristocrats occurred in works produced mostly by middle-class artists and writers speaking to a middle-class audience.9 Aristocracy itself became a fantastical signifier of a certain kind of exclusivity. We can observe a now-familiar paradigm in which elitist aesthetes invited a coterie of discriminating minds—opposed to the Philistine rabble—whose enlightened choices signaled forms of special belonging and affiliation. From counterculture to hipsterism, the avant-garde enters commodity culture by promising a unique, edgy self-making through the consumption of special objects and artworks. Decadence stands as one of the earliest versions of this recognizable social and artistic formation, imbricating countercultural artmaking into the middle-class world it sets itself against.10 The advertising poster reveals this paradigm at its most stark, marketing an elite commodity or cultural event while creating an unusual aesthetic spectatorial experience with a striking visual design. Irony, the characteristic stance of the decadent, emerges from these paradoxical conditions, situating the artist both within and above a degraded, unredeemable world.

The art poster connoted decadence in its experimental visual styles, but it also came to signify decadence as a metaphysical symbol in the 1890s. For a decadent artist like Aubrey Beardsley, as well as for decadent theorists like Huysmans and Arthur Symons, the new art poster came to stand as a perverse visual emblem of modern life, epitomizing modernity’s bankrupt value system and its soulless dependence on commercial trade. Their admiration for the poster thus bespoke a gleeful nihilism as they reveled in its weird colors, grotesque bodies, and urban milieu, a visual aesthetic that was artificial, anti-picturesque and anti-Romantic—resoundingly “against nature,” to translate the title of Huysmans’ novel. In fact, Huysmans published an admiring essay about Jules Chéret, the French inaugurator of the art poster.11 The poster’s very ephemerality resonated with the decadent’s conviction that Western culture was on the wane, and soon to expire. On the opposing side, conservative critics also used the language and metaphors of decadence to attack art posters as the perfect symbol of a high-capitalist world in which everyday life had been completely commodified. “Decadence” and its imagery was wielded by critics hostile to the new developments in both consumer culture and aesthetic culture. Some saw cultural decline writ large in the advent of massive, multicolored posters blanketing city walls and hoardings; their arrival seemed to portend a dark future.

Decadent rhetoric surrounding the poster arts echoed a problematic quality in decadent writing more broadly, which is that the qualities of praise and insult, good and bad, moral and immoral, beautiful and ugly, all became hopelessly intermingled. Both supporters and detractors—of posters, or of decadent arts—often invoked the same tropes and images, though with reversed values. In fact, the decadent movement is distinctive for being defined as much by its critics as by its actual practitioners: some of the most acute characterizations of decadence came from hostile voices, from Nisard’s 1834 attack on late Latin poetry, to Nietzsche’s evisceration of Wagner in The Case of Wagner (1888), to Max Nordau’s infamous screed Degeneration (1892).12 Even while “decadent” began as a disparaging term wielded by conservative critics against modern and ancient art, it became a rallying cry for those who wanted to identify with a defiant avant-garde. Decadence’s occupation of an ambiguous territory between admiration and censure reflects its instability as both a term and an idea. Its etymology, from the Latin de + cadere, means to fall down or fall away from: the word encodes a sense of comparison across time, such that a society, a body, or an artform falls away from a preceding, superior state.13 Richard Gilman argues that decadence lacks a coherent identity because it only exists in relation to other things, a negative term introduced to name an opposite, complement, or nemesis.14 For some critics, decadence’s subversive mode of negative critique links it to more modern philosophical movements such as deconstruction and postmodernism.15 These unstable aspects of decadence define the vexed late-Victorian reception of art posters, controversial symbols that were alternately hailed for bringing beauty to the streets or attacked as a garish urban menace. Contradictory accounts of the poster, both for and against, each drew upon a familiar repertoire of decadent imagery.

Posters participated in the spectacular realm of late-century consumerism, as studied by scholars of early cinema and the “dream worlds” of Parisian shopping.16 Walter Benjamin, in The Arcades Project, titles one section “Exhibitions, Advertising, Grandville,” linking advertising to the fantastical, surreal commodity worlds of the great expositions and the caricatures of J. J. Grandville.17 For Benjamin, advertising operates within a culture of display that renders the object “evanescent” and “otherworldly,” investing it with “mythic qualities.”18 Advertising itself enjoys a dubious reputation among scholars today—as Mica Nava writes, it is usually seen as “the iconographic signifier of multinational capitalism, and therefore in some ethical sense, beyond redemption.”19 It is not my aim to try to redeem advertising, but rather to explore its sophisticated mechanisms. I follow Nava in observing that advertising is not a distinct field with its own formal features, but rather a mixture of many visual codes, both high and low; in fact, advertising imagery cannot “easily be distinguished at a formal level from … other cultural representations.”20 (Nava pushes against a more traditional account that would draw a sharp distinction between high art and commercial advertising—as voiced in Clement Greenberg’s classic essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939).)21 Joan Gibbons argues more pointedly that art and advertising are not in fact separated by “intrinsic properties”: “advertising can be said to function aesthetically, if the aesthetic is taken in the Kantian sense of a sort of playground for the emotions, imagination and intellect.” And, likewise, artworks too participate in networks of markets and ownership, bringing them closer to the realms of advertising than is usually acknowledged.22

The chapter will explore how advertisements emerged as part of what Raymond Williams calls a “magic system,” drawing on the same elements of wish, desire, and self-making that were key to the avant-gardism of the 1890s.23 In fact, Victorian advertisements embraced modes or qualities that we usually assign to the aesthetic: by appealing to ideas of freedom, choice, privacy, autonomy, gratification, and self-making, advertisements evinced qualities resonant with those of a Kantian art for art’s sake, catering to individual perception and judgment over and against more social or collective values. Theorists of advertising like Williams and Michael Schudson argue that the nature of capitalism itself creates the conditions for the dreamworlds of advertising: the capitalist system proposes personal, private, individual solutions to social problems, as opposed to collectivist or socialist ideas.24 Modern advertisements therefore cater to the world of the private individual, limning the exquisite identity of the citizen-as-consumer. For spectators in the 1890s, the poster became the most visible symbol of a world transformed by capital. Some interpreters saw the poster as the epitome of an atomistic, commercialized, anti-community ethos, signifying decadence in the way it celebrated individual aesthetic choice at the expense of the larger social whole. Art and advertising thus radically converged, drawing on the same fin-de-siècle philosophies of self, thought, taste, and desire.

Poster History: The Language of the Walls

The modern advertising poster was large in scale, featured a dominant image, and was plastered on a municipal façade or hoarding. It was a new participant in the crowded late-Victorian urban landscape. Public notices, or “bills,” had been appearing on posts marking pedestrian pathways in London since the seventeenth century. A “poster” originally described the person who pasted up bills, but sometime after 1860 the word came to denote the bill itself.25 In the early nineteenth century, taxes on newspapers and print advertisements worked to drive advertising outside and into public spaces. Most early bills consisted only of words, though this did not prevent them from contributing to a general visual mayhem on city streets. Outdoor advertising expanded greatly between the years 1830 and 1850, with billposting, lettering on blank walls, stenciling on sidewalks, sandwich men, and advertising wagons plastered with bills.26 Some enterprising advertisers created giant vans molded into the shape of their chosen commodity—a trend famously denounced by Thomas Carlyle in Past and Present (1843), who describes “a huge lath-and-plaster Hat, seven-feet high, upon wheels” that perfectly emblematizes the modern worship of commerce and puffery. Carlyle concludes of the phenomenon: “The Quack has become God.”27 (These advertising vans snarled London traffic to such an extent that they were outlawed in 1853.)28 Charles Dickens depicts the visual excess attending early-Victorian outdoor advertising in “Bill-sticking,” an 1851 article in Household Words, which features an unwitting London flâneur humorously stalked by advertising slogans across street, park, pavement, and every imaginable urban surface.29

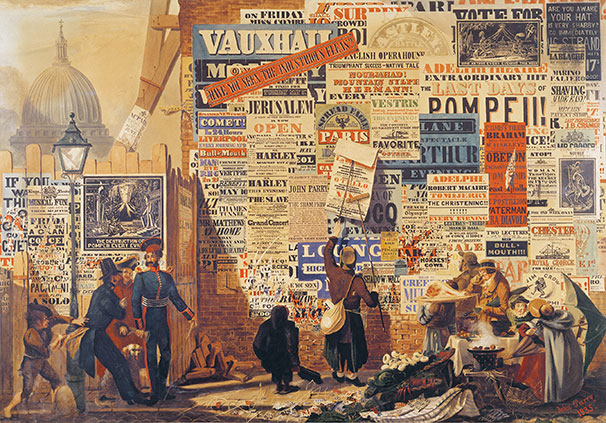

John Orlando Parry’s painting The Poster Man (1835) (Fig. 6.1) captures the visual riot of early-nineteenth-century billposting. Juxtaposing the wall signs with street-sellers below, the painting suggests that the bills create a visual version of a street call. Instead of an audible cry, the posters instead offer large letters and demanding typefaces, a visual version of a shout for attention. Thomas Richards interprets this painting by way of Henry Mayhew’s taxonomy of street-sellers, concluding that early-Victorian advertising still adhered to a conventionalized, old-fashioned “repertoire of representation that had been fixed in early modern Europe.”30 Yet the painting also portrays a new direction in Victorian commercial culture, as an older, oral, personalized salesmanship gives way to a newer, technologized, and depersonalized pitch through the medium of print—a pitch that depends on striking visual effects. The pickpocket lurking in the painting’s lower-left also insinuates a link between the modern advertisement and theft and hucksterism: the earliest touted commodities were quack pills and medications.

Fig. 6.1 John Orlando Parry (1810–79), The Poster Man, also known as A London Street Scene, oil on canvas, 1835. Private Collection/Bridgeman Images.

Parry’s busy street scene is resolutely crammed with words, rather than images. Only late in the century did the image-driven poster come to dominate the urban streetscape. The pictorial advertisement had already appeared on hoardings as early as the eighteenth century, but it typically promoted working-class, mass entertainments like the theater and the circus.31 (In Parry’s painting, a pictorial poster advertises a lurid re-enactment of the explosion at Pompeii.) Image-driven advertisements initially connoted a debased working-class culture, likely owing to the use of pictorial signboards to communicate with illiterate viewers. Before the late-century advent of art posters, more established, conservative newspapers did not use eye-catching pictures in their pages, and theaters specializing in serious drama refused to place images on their posters, using only letterpress announcements.32 These illicit associations with working-class culture explain why an 1863 critic reacts with outrage to the new trend of pictorial advertising. Railing against “spasmodic typography,” and “sensation type headings,” the critic also attacks the nefarious use of images to promote wares: “The most respectable provincial journals will allow engravings of tea-caddies … and Worcester sauce bottles, to be inserted in prominent positions in the very midst of the regular old-fashioned advertisements. It is very sad,” and enough to drive “any old compositor … to retire from his profession.”33 For this critic, the very use of pictures as an advertising technique is aligned with other suspicious, newfangled art movements like sensationalism and spasmodic poetry.

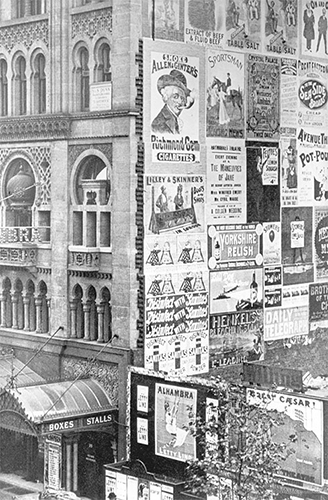

Yet despite the misgivings of elite cultural institutions and critics, visual advertising with more pictures began to invade Britain’s public spaces and forums in the later nineteenth century. The pages of illustrated magazines and journals were transformed by pictorial advertisements, while posters appeared on omnibuses, in train sheds, shops, factories, theaters, underground stations, and on special advertising posts erected for the purpose (Fig. 6.2). Susan Sontag writes of how the poster “implies the creation of urban, public space as an arena of signs: the image- and word-choked façades and surfaces of the great modern cities.”34 Technical innovations in color lithography allowed for the ever-increasing size and complexity of poster images. The lithographic technique—which had been invented by German playwright Alois Senefelder in the 1790s—could produce delicate tones and colors from an image prepared directly on the stone.35 (“Lithography” literally means “drawing on stone.”) Color lithography fueled the production of all kinds of Victorian ephemera, including music-sheet covers, illustrated trade cards, and souvenir brochures. By the mid-1860s, artists were producing small posters for the more affluent London theaters.36 John Ruskin querulously complained about the success of the pictorial poster in Fors Clavigera, writing in Florence in 1872: “[T]he fresco-painting of the bill-sticker is likely … to become the principal fine art of modern Europe: here, at all events, it is now the principal source of street effect. Giotto’s time is past … but the bill-poster succeeds.”37 By 1900, pictorial advertising had transformed the appearance of all the major urban centers in Europe and America.

Fig. 6.2 Posters in the modern cityscape. Francis Frith & Co., Alhambra Theatre, London. Photograph, 1899. Copyright The Francis Frith Collection.

Posters were an inherently public imagery, defining the modern street and the urban landscape. Yet they also served as portals into the private realm of consumption and the consumer lifestyle. I analyze them as key contributors to the media world of the parlor studied in this book. Advertisers often used the same image as both magazine art and poster art: the same Pears’ Soap ad might appear at life-size in a London street and at hand-size in the Illustrated London News. This fluidity was observed by Victorian commentators, who themselves consolidated all business-driven imagery under the term “poster.” In the numerous volumes devoted to poster arts published in the 1890s, posters included everything from catalogue covers to wall-sized advertisements.38 Magazines or newspapers also published pictorial advertisements that were meant to be clipped out and put up on the wall—as in the case of “Bubbles,” whose famous image decorated parlor walls well into the twentieth century. Many pictorial posters promoted home goods and domestic values, tracing a path from the city wall into the home. Visual advertising worked to mediate between public and private, inside and outside, the parlor and the street.

George William Joy’s painting The Bayswater Omnibus (1895) (Fig. 6.3) plays on the ambiguity of inside/outside defining the modern advertisement. The painting depicts a claustrophobic scene of passengers seated on an omnibus, juxtaposed with advertising posters directly over their heads. The close-up quarters take us into an interior, positioning us from the viewpoint of fellow passengers seated across the way, and squeezing us into the small compartment. But it is also an exterior, a public venue, an assembly of strangers traveling by up-to-date transport. The omnibus represented an exemplary middle-class space, as its fare excluded the poorest, while the richest could choose a private cab. The painting offers a visual meditation on new publics and new forms of publicity, inviting us to compare the bus passengers with the advertisements over their heads. Posters promoting a female celebrity and the “Bubbles” soap child are juxtaposed with a female passenger in an elaborate striped dress carrying a large bouquet, herself a spectacle. A modern woman, she travels alone on the omnibus without chaperone or family. The advertising posters conjure up the internal realms of wish, desire, and consumerism, even while adorning a new public space that is an ambiguous kind of enclosed chamber. The painting ultimately portrays the modern subject as defined by a porousness between interiors and exteriors, body and mind woven into the fabric of a new public culture of the advertising image.

Fig. 6.3 George William Joy, The Bayswater Omnibus, oil on canvas, 1895. © Museum of London.

The Street as Art Gallery

Advertisers arrived at a key innovation in the late 1880s when they began to purchase paintings to convert into advertising posters. So-called “artistic advertising” drew on the pre-eminence of members of the Royal Academy, imbuing advertisements with the aura of fine art. Making advertisements out of paintings lent prestige and éclat to the visual presentation. The most well-known instance of artistic advertising—and likely the most famous of all Victorian advertisements—is “Bubbles,” in which a boy blows bubbles as a promotion for Pears’ Soap. The ad began as a painting by John Everett Millais, titled A Child’s World; it was displayed in 1886 at the Grosvenor Gallery in London. The painting drew upon a longstanding vanitas motif to hint that childhood itself is but a fleeting bubble. Millais’s painting was purchased by William Ingram of the Illustrated London News to appear as a color plate in the 1887 Christmas supplement. There it was seen by Thomas Barratt, the managing director of Pears’ Soap, who would become renowned as a pioneer of modern publicity techniques. Barratt purchased the painting directly from Ingram, in part owing to the lack of copyright laws.39 He added a transparent bar of soap to the lower-left corner of the painting, making a new image now called “Bubbles” (Fig. 6.4). Not only was Millais at the height of his prestige as a painter, but the print also used over twenty-five lithographic stones to craft its delicate coloring. The popularity of this image cannot be underestimated: it was printed more than 1 million times, and its likeness hung ubiquitously in British living rooms well into the twentieth century.40 Though the poster today might seem like sentimental kitsch, at the time spectators were struck by its cutting-edge qualities; Millais had been a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and the image offered a luxuriant display of Millais’s famed skills in rendering texture and form. Artistic advertising blurred together high and low art in a way that opened the door to posters proposing more radical visual experiments.

Fig. 6.4 “Bubbles,” Pears’ Soap advertisement, adapted from a painting by John Everett Millais, chromolithograph, 1888 or 1889. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

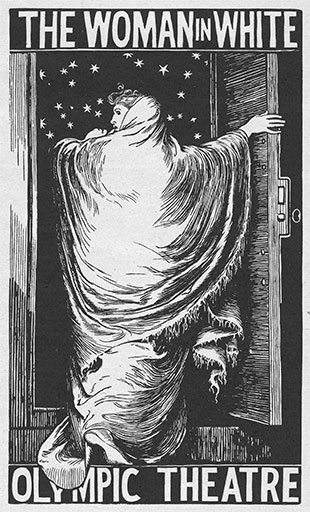

While the blending of art and advertising was a distinct phenomenon of the late 1880s and 1890s, the image widely acclaimed as the first British art poster was something of a historical outlier: it was designed in 1871 by painter Frederick Walker to advertise a theatrical melodrama, Wilkie Collins’s adaptation of his sensation novel, The Woman in White (Fig. 6.5). The image differed from the art posters collected and admired in the 1890s in that it was a woodcut, not a color lithograph, and therefore belonged to the medium of an earlier era. Nevertheless, the poster epitomized the visual tactics of a new kind of art-infused advertisement. Already in the 1890s this image was canonized: the Athenaeum called it in 1894 “the first high-art poster the world ever knew.”41 The poster was unusual not only for the high status of the artist—Walker was a member of the Royal Academy—but also for its remarkably large, life size. Walker’s woman, her finger pressed to her lips, beckons the viewer into the story’s world to witness the suspenseful events that will unfold. Though both the novel and the melodrama portray the woman in white as a hapless victim, here she appears as a compelling, enticing guide. The poster plays upon confusions of inside and outside, private and public: we see the image from the street, but the scene is staged as an interior view, as we climb the stairs behind the woman and look through a doorway out to the starry sky. The woman’s dress juts out over the edge of the poster label, heightening the illusion that she is stepping outside. The scene immediately captures our attention with its spatial play; yet it also resists any immediate legibility. We observe the symbols of secrecy without learning any secrets. The poster offers a meta-commentary on the act of spectatorship itself, as theater-going becomes its own kind of alluring entertainment, inviting us to consume the pleasurable illusion within, or beyond.

Fig. 6.5 Frederick Walker, poster advertising The Woman in White at the Olympic Theatre. Woodcut engraved by William Harcourt Hooper, 1871. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, Open Access Collection.

Walker described this poster as a “dashing attempt in black and white”—a reference not only to Collins’s Woman in White but also to James McNeill Whistler, who had popularized the language of color as a way to describe visual experiments in quasi-abstraction.42 Whistler’s portraits of women wearing white in the 1860s had tied him inseparably to this color and to this female imagery. When Whistler retitled his painting The White Girl (1862) as Symphony in White No. 1, he incensed critics for elevating pattern and form over the humanism of his female subject (Fig. 6.6).43 Walker’s account of his poster as “a dashing attempt in black and white,” then, aligned his image with Whistler’s formalist painterly experiments, showing how the art poster occupied an ambiguous territory between purpose-driven mass culture and the more opaque, challenging techniques of early visual modernism. Walker’s mysterious poster cultivated an air of inscrutability, but it also engaged in a playful narrativity, hinting at familiar yet taboo stories about women sneaking out to forbidden trysts. Likewise, Whistler’s painting too, for all of its modernist credentials, offered symbolic objects insinuating a familiar narrative: the red-haired model holds a broken flower and stands on a wolf-skin rug with toothy jaws, hinting at a story of temptation and fallenness. No wonder that this painting, exhibited in 1862, was assumed by many critics to illustrate Wilkie Collins’s novel, despite the artist’s protestations to the contrary.44 In Chapter 4, I discussed how Collins’s Woman in White participated in a broader visual culture of sensation; it is deeply appropriate that the novel’s world of spectacularized and commodified female figures had an afterlife in realms of both visual modernism and early pictorial advertising.

Fig. 6.6 James McNeill Whistler, The White Girl, oil on canvas, 1862. Retitled in 1867, Symphony in White, No. 1. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

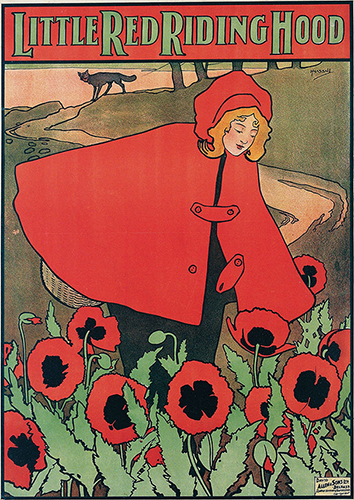

Walker’s Woman in White design was widely acknowledged across Europe as inaugurating the age of the art poster. Walter Benjamin singles out the image in The Arcades Project as the haunting sign of an incipient modern visual culture. For Benjamin, Britain’s first mass-market art poster appeared suddenly on walls around London in a way that was as mysterious and sensational as the story it advertised.45 The poster’s remarkable visual come-on made it the perfect emblem for the rise of a new commercial medium, one that used striking aesthetic and imagistic techniques to market commodities, often arranged around a female figure. Walker’s poster shares similarities with the famous color lithographs of the French artist Jules Chéret, known as the “father of the pictorial poster” or “Maître de l’Affiche.”46 Chéret worked in London in the 1860s, mastering the techniques of color lithography. He returned to Paris in 1866, transporting giant printing machines across the Channel to begin mass-producing posters on a large scale. With products ranging from beverages to actresses to lamp oil, Chéret’s artistic posters employed a successful formula featuring a life-size woman floating with delight amid the scene of her chosen commodity. Chéret’s style was imitated in England by artists like Dudley Hardy, with his cheery Gaiety Girl, advertising a popular musical comedy at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1893 (Fig. 6.7). All of these posters, from Walker’s to Chéret’s and Hardy’s, use an alluring, life-size female figure engaged in a stylized form of indirection, suggesting possibilities beyond the mere functional use of a commodity. Chéret’s poster for Saxoléine lamp oil (Fig. 6.8) depicts a woman with a lamp, but its real subject is an erotic luminosity: the woman’s floating hair and clothes suggest that she is being buffeted by the swirling winds of modernity, causing her delirious happiness. The poster’s world of color, pleasure, and illumination transcends the mundane lighting act at its center.

Fig. 6.7 Dudley Hardy, “A Gaiety Girl,” poster advertising a musical comedy by Sidney Jones, color lithograph, 1895. Heritage Image Partnership Ltd./Alamy Stock Photo.

Fig. 6.8 Jules Chéret, poster advertising Saxoléine (paraffin lamp oil), color lithograph, 1896. Artokoloro Quint Lox Limited/Alamy Stock Photo.

The rampant blanketing of Victorian cities with arresting, life-sized images produced a radical remaking of the urban landscape, a development that stirred much controversy. When the street became a de facto art gallery, critics used poster styles as a shorthand for debating traditional versus more experimental values. Posters had to demand attention in a busy visual field with speed and efficiency. Their striking visual form was a consequence of their competitive, message-bearing function. Even though some posters adopted the conventional realist styles of genre paintings, critics still often generalized about posters as being lurid, sensational, garish, and immoral. In the New Review in 1893, five different authors weighed in on “The Advertisement Nuisance,” objecting to the way that all posters, not just artistic ones, had “invaded” and “disfigured” the “loveliest spots of English scenery.”47 The critics harnessed an anti-decadent rhetoric to attack the artifice of posters’ “flaming letters” and “grotesque and sensational designs” in contrast to the more traditional, picturesque beauty of rural England.48 Many critics described posters en masse as artificial and anti-realist; posters were positioned against more mainstream, nature-based, and picturesque styles.49 Charles Baudelaire had made artifice into a canonical decadent value in “The Painter of Modern Life”, when he ridiculed nature-based Romantic aesthetics as animalistic and ugly, praising instead cosmetics and human invention. The artifice of the art poster made it come to stand for anything commercial and manmade, as opposed to the more picturesque productions of nature.

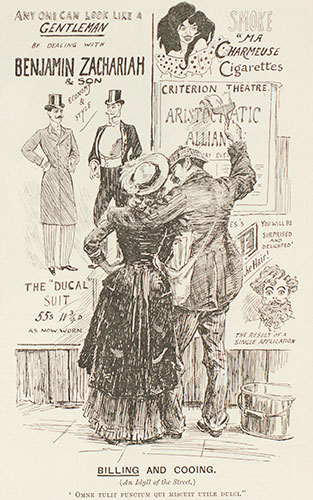

Artifice, for many mainstream critics, also suggested ties to the insincere, immoral, and corrupt. (Oscar Wilde takes a subversively favorable view of the insincere arts in his classic decadent manifesto “The Decay of Lying” (1891), when he makes a plea for artforms both beautiful and unreal.) An 1894 Punch cartoon, “Billing and Cooing” (Fig. 6.9), links decadent style to the immoral untruths of advertisements. The cartoon indicts a wall filled with comically fraudulent poster ads, including one clearly modeled on the style of Aubrey Beardsley. The cartoon juxtaposes a bill-sticker’s seduction scene against the wall filled with posters, noting in Latin that it is useful to mix business with pleasure—referring both to the bill-sticker’s flirtation and to the advertisements’ promises of false pleasures. The posters variously offer to make the spectator more gentlemanly, more luxuriantly hairy, or more French, as suggested by a louche Beardsley-style woman smoking “ma charmeuse cigarettes.”50 In fact, advertising posters for British audiences often intimated Frenchness due to the influence of Jules Chéret and his lithographic innovations. The art poster came to Britain from France, as did decadent art and poetry, and all of these connoted stereotypical French qualities of immorality and sexuality. The decadent poster appears in the cartoon among other duplicitous visual come-ons as the emblem of a larger, corrupt advertising system.

Fig. 6.9 “Billing and Cooing.” Punch, May 26, 1894.

These elements also opened the door, however, for posters to serve as the gateway to an elite late-Victorian counterculture. As connoisseurs embraced posters as collectible aesthetic objects, a host of institutional forms sprang up to anoint posters as high art, including London exhibitions in 1894 and 1896, books about posters aimed at connoisseurs, and a periodical, The Poster, which addressed itself to collectors from 1898 to 1901. Perceived by some as art commodities, posters were stolen off of hoardings and sold by dealers. Their radically divided reception history highlights the poster’s ambiguous status in the cultural realm, as it embodied both mass market reproducibility and the fine art qualities of uniqueness, singularity, and experimental style. Oscar Wilde shows himself an aesthete-in-the-know when, writing in The Speaker in 1891, he celebrates the beauty of French poster kiosks: “The kiosk is a delightful object, and, when illuminated at night from within, as lovely as a fantastic Chinese lantern, especially when the transparent advertisements are from the clever pencil of M. Chéret.”51 For discerning critics, the art poster came to embody a form of art for art’s sake—adorning the modern cityscape with dazzling visuals that exceeded the poster’s mundane advertising purpose. The poster lived beyond its stated business message, as affirmed by the poster collectors who were stealing them off the walls to make them into high art. Here, too, the Frenchness of art posters added luster for more elite audiences, signifying a desirable urban cosmopolitanism. Like decadent arts and poetry, posters too were the product of a fin-de-siècle cross-Channel cultural movement.

The British art poster also played a role in the ongoing late-Victorian debate about the politics of urban life, both promising and terrifying. On the one hand, some critics saw art posters as the vehicle for aesthetic democratization and mass education, resonating with the century’s Reform Bills. An 1881 article in The Magazine of Art thus imagines “The Streets as Art-Galleries,” arguing that posters could serve as the working-man’s avenue to aesthetic enfranchisement. “[T]o reach the people,” the critic declares, “art must step out of the picture gallery, out of the museum, out of the school-room, … and go into the streets.”52 This progressive idea predicted that the urban façade could be transformed into a democratized, artistic salon for all British people.

On the other hand, however, some critics understood the advertising poster, with its garish, sensationalist visual techniques, as the pre-eminent sign of an urban menace sited especially in working-class neighborhoods. In a Punch cartoon of 1888, titled “Horrible London or, the Pandemonium of Posters,” the devil posts bills depicting the Jack the Ripper murders. The accompanying poem blames posters for corrupting susceptible working-class viewers: “These mural monstrosities, reeking of crime,/ Flaring horridly forth amidst squalor and grime,/ Must have an effect which will tell in good time/ Upon legions of dull-witted toilers.”53 The poem conflates the posters’ visual style with its sensationalistic content—which seems a humorous exaggeration, given that most posters advertised things like soap and digestion pills. Yet this imagery channeled a powerful late-century anxiety around potential working-class unrest and violence.54 The poem sweepingly designates all posters as “flaring” “mural monstrosities”: for some conservative critics, visually striking posters became the symbol of a broader advertising culture that promised inevitable cultural decline, an incipient and threatening decadence.

Aubrey Beardsley’s Japanee-Rossetti Girl

The visual culture of decadence was defined by Aubrey Beardsley in the 1890s. Though scholars have typically studied him through the lens of a fine-art sensibility, focusing on his illustrations for esoteric literary works, he was in fact a commercial artist who produced drawings and illustrations for hire—a “black-and-white” artist, in Victorian parlance.55 Critics often derided his works as cartoons or caricatures. He was known as much for editing the art in the avant-garde periodical The Yellow Book as he was for a scandalous theater poster that dominated the streets of London in 1894. Beardsley produced purpose-driven art for book covers, catalogue covers, title pages, and magazine covers, as well as poster advertisements for booksellers and the theater. His graphic designs became notorious for their weird, grotesque figures and striking, flattened style, relentlessly parodied across the pages of Punch. Max Beerbohm described the Beardsley media phenomenon in 1898:

Look at her arm! Beardsley didn’t know how to draw. The public itself could draw better than that. Nevertheless, the public took great interest in all Beardsley’s work, as it does in the work of any new artist who either edifies or shocks it.56

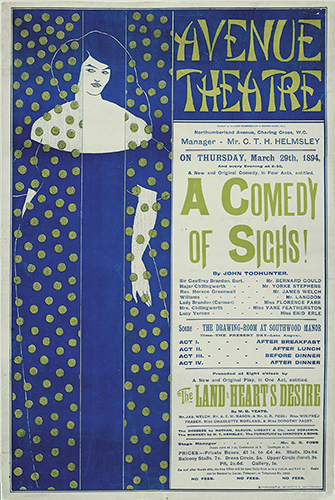

Beardsley’s public reputation exploded in 1894 with his poster design for the newly opened Avenue Theatre in London (Fig. 6.10). The poster was commissioned by Florence Farr, the theater’s manager and an Ibsenite actress who wanted to convey a sense of cutting-edge dramatic works. First used to advertise John Todhunter’s burlesque romantic farce A Comedy of Sighs, the poster also promoted W. B. Yeats’s The Land of Heart’s Desire, as well as George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man. Beardsley’s unusual design features a woman standing behind a gauzy curtain covered in polka dots. Different blocks of color serve as both foreground and background, giving the image a shifting dynamism between flatness and three-dimensionality. The woman looks askance, sultry and crooked, creating an atmosphere of dark eroticism. Orientalized letters spell out “Avenue Theatre,” even though the plays had no Asian content—invoking the avant-garde associations of japonisme and its techniques of visual flatness.57 These elements all address the cultured passerby who might identify with experimental arts, whether in posters or in progressive theater productions.

Fig. 6.10 Aubrey Beardsley, poster for the Avenue Theatre, color lithograph, 1894. Heritage Image Partnership Ltd./Alamy Stock Photo.

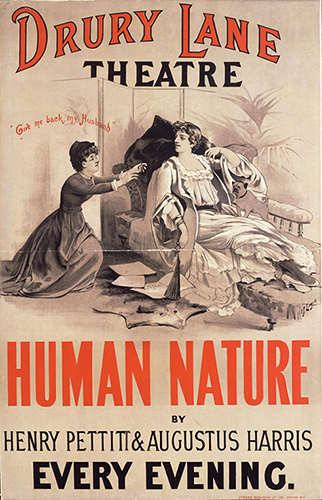

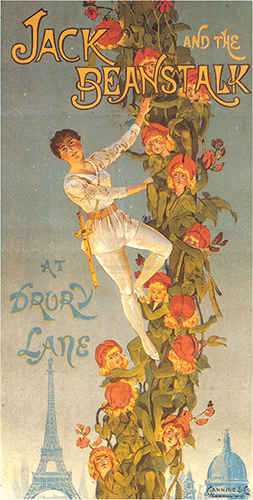

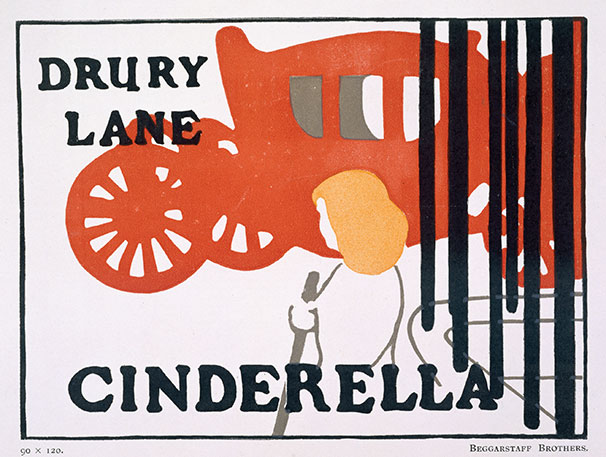

The experimental qualities of Beardsley’s poster come into focus when we compare it with a more conventionally styled theater poster. An advertisement for the 1885 Drury Lane melodrama Human Nature adheres to formula in depicting a moment of crisis: the scheming seductress sprawls on a chaise lounge while the beleaguered wife pleads with outstretched hands, “Give me back my husband!” (Fig. 6.11). The evil woman reclines amid voluptuous ruffles, complemented by damning details of bearskin rug and scattered pictorial magazines. The image presents a quasi-legible narrative using a realist visual style. (Then, too, I would argue that this poster is itself a complex object that attracts on multiple levels, affirming a moral judgment against the seductress even while making the pitch using the spectacle of her luxurious body.) This type of theater poster, choosing a narrative moment to represent in tableau, can be read into the long history of cinema, as I discuss in this book’s conclusion: the image oscillates between pictorial stillness and narrative sequence, a model that would come to define early visual storytelling in film. While the Drury Lane poster works in a more traditional visual style, it, too, participated in a dynamic and innovative visual culture of advertising.

Fig. 6.11 Poster advertising Human Nature at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, color lithograph, 1885. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The comparison, however, reveals Beardsley’s radical visual choices. The Avenue Theatre poster dramatically flattens the poster plane and avoids any distinct narrative intelligibility. Both posters center on an eroticized female figure, but Beardsley refuses to frame his femme fatale so as to distance the viewer from her dark qualities. We appreciate the figure’s striking pattern without any narrative cues to conventional Victorian stories about sexual morality or female performance. Here too, style matches subject, as the poster shifts between flatness and depth to mirror the atmosphere of erotic ambiguity.

The Avenue Theatre poster made a dramatic impression on the world of design. It had, writes one historian, “a revolutionary effect on both sides of the Atlantic.” Reproductions quickly appeared in France, Germany, Belgium, Russia, and Austria.58 It was featured in the first English poster exhibition in 1894.59 The poster’s unusual style made it one of the first to attract widespread coverage in the British press. Charles Hiatt wrote of it in 1895,

Nothing so compelling, so irresistible, had ever been posted on the hoardings of the metropolis before. Some gazed at it with awe, as if it were the final achievement of modern art; others jeered at it as a palpable piece of buffoonery: everyone, however, … was forced to stop and look at it. Hence, … it was a most excellent advertisement.60

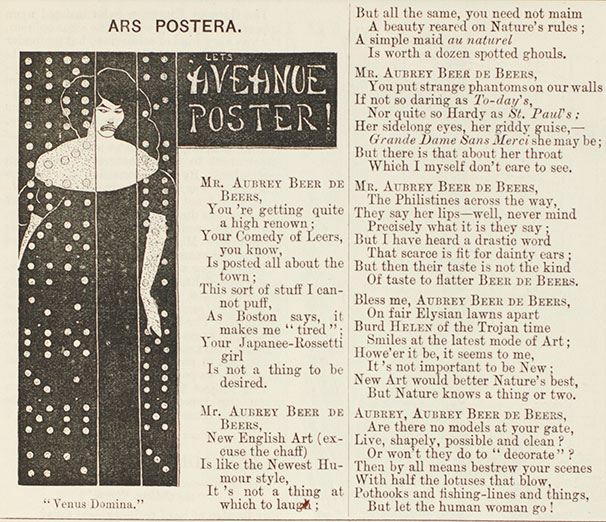

Hiatt was writing for the poster-collector audience, and takes a favorable tone, but the mainstream press was largely negative. The Pelican called the female figure “bilious, lackadaisical, backboneless, anaemic, ‘utter’ and generally disagreeable.”61 Punch created a parody image titled “Let’s Ave-a-Nue Poster,” along with a fifty-line poem, “Ars Postera,” which addressed itself to “Mr. Aubrey Beer de Beers”: “[A]ll the same, you need not maim/ A beauty reared on Nature’s rules;/ A simple maid au naturel/ Is worth a dozen spotted ghouls.”62 The cartoon reproduces a fairly accurate imitation of Beardsley’s female figure, but adds extra spots of blemish to her skin and paints her lips with stereotypically Africanized features (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12 “Ars Postera.” Punch, April 21, 1894.

The Avenue Theatre poster is a key object for thinking about what visual decadence looked like, and how it was constructed. The image itself produced non-normative cues toward embodiment, race, and sexuality, which were then observed and exaggerated by hostile critics. When Beardsley portrayed a woman standing behind a polka-dotted curtain, veiling her skin in spots, he deliberately invited likeness to a diseased body, hinting at syphilis and sexual promiscuity.63 This imagery resonated with literary accounts of decadence that extolled it as a kind of beautiful disease.64 For the decadent artist, the diseased body was beautiful and ironically desirable. The spots, too, participated in a larger proto-modernist project recognizable from Whistler, turning female subjects into bearers of unusual patterns and forms. (As the Punch poem exhorted Beardsley, “[L]et the human woman go!”) The poster also invoked the specter of race with its gratuitous Japanese lettering, orientalizing the erotic figure at its center. If decadence insistently analogized culture to a biological organism in decay, then a key symbol for that waning was the degenerating body, associated by nineteenth-century thinkers with both disease and race. The decadent image drew on racist stereotypes about foreign bodies to create a perverse avant-garde aesthetic—one that the Punch parody adopted and inflated, with a female figure now explicitly Africanized and primitivized. The operation of the racist type within Beardsley’s poster is not predictable or stable, as the image wields the exotic allure of otherness rather than disavowing it. The Punch poem also invokes Africanness with the appellation “Aubrey Beer de Beers,” which alludes to the de Beers diamond mines in South Africa, opened in 1888. According to this logic, Beardsley himself bears the racial taint of his grotesque productions. Decadence ultimately emerged in an echo-chamber between the poster and its critics, with both decadent and anti-decadent imagery conjuring a diseased, racialized, sexualized body.65

The overheated responses to Beardsley’s poster underline its role in a larger culture war surrounding avant-garde art styles. Punch alluded to that battle when it mocked the Avenue Theatre figure as a “Japanee-Rossetti girl.” Critics in the 1890s insistently portrayed Beardsley as the stylistic inheritor of Rossetti, often using conspicuously racialized language.66 M. H. Spielmann, in an important 1895 article on English posters, finds in Beardsley’s work “distorted echoes of Chinese or Annamite execution and Rossettian feeling, seen with a squinting eye, imagined with a Mephistophelian brain, and executed with a vampire hand.”67 Spielmann’s denominations are strange indeed, given that Rossetti’s style of voluptuous three-dimensionality looks nothing like Beardsley’s anemic elongations. Yet both artists were linked in the critical mind for refusing to produce works that conveyed clear narratives in realistic settings. Rossetti had gained notoriety in the 1870s for painting women in colorful, fleshly sensuality unframed by discernible moral narratives.68 His paintings canonized art for art’s sake as a style premised on visual pleasure, erotics, and physical desire. Rossetti’s Lady Lilith (1866–8), a pre-eminent example, portrays a voluptuous woman combing out her long red hair, baring one fleshly shoulder. The painting merges erotic feminine allure with the formal seductions of color, shape, and texture (Fig. 6.13). Critics had attacked Rossetti’s experimentalism by invoking bodies that were unnatural, unhealthy, and overly sexualized; a similar rhetoric now appeared in Beardsley criticism, which was additionally freighted with hyper-racialized imagery and a more insistent language of disease and decay. Indeed, the racial otherness invoked by Beardsley’s poster and its critics spanned a bewildering number of exoticized locales, from Africa, to Japan, to China, and the “Annamite” mountains of Indochina. These tropes of pronounced foreignness spoke both to Britain’s heightened imperial activities in the 1880s and 1890s and also to the move from aestheticism to decadence: both art movements proposed countercultural values via challenging styles and embodied figures, but Beardsley’s decadence reflected a dark attitude deliberately embracing disease and the raced body as a site of aesthetic challenge.

Fig. 6.13 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Lady Lilith, oil on canvas, 1866–8. Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE. Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial Collection/Bridgeman Images.

The shift in medium from Rossetti’s painting to Beardsley’s poster also implied a new kind of cultural politics, moving from the rare, unique artwork to the mass-produced advertisement, and signaling the arrival of a new media culture in the 1890s—one in which artworks incorporated the taint of mass culture into their aesthetic shock value. Whereas Rossetti had produced a resolutely private art, abandoning public exhibitions in the face of hostile reviews and selling directly to patrons, Beardsley ushered in a new phase in experimental art’s relation to media culture, producing a challenging art accessible to any passerby on the street. Yet we can also observe a continuity in the way that aestheticism was never completely removed from a public or commercial world, despite Rossetti’s reclusiveness. Though aestheticism is often seen as a solipsistic art philosophy emphasizing individual impressions, scholars have also noted how the movement became a fashionable vogue in the 1870s and 1880s, popularized by new public organs that ranged from elite journals and exclusive galleries to a bourgeois collecting craze for home décor.69 Beardsley’s poster art, then, can be seen as an extension of the public trajectory of aestheticism, taking a new art style even further into the everyday world of bourgeois commodity culture. This continuity, however, does not mitigate the shock value surrounding Beardsley’s unambiguous and very direct step into commercialism. When Punch titles its parody poem “Ars Postera,” the parody reflects a home truth: Beardsley’s radical poster does stand as a kind of manifesto, an ars poetica for a new, commercialized avant-gardism.

Hostile critics attacked the art poster’s new visual tactics as versions of the mysterious techniques of art for art’s sake. George Hyde’s 1897 comic poem, “A Poster,” included the following directions: “Paint a frantic,/ Frenzied antic,/ In any crazy shade;/ Then add some lines/ In mad designs—/ And now your poster’s made! … Oh! never fear/ Because it’s queer,/ For, on the other hand, / Your work’s in vain/ Should it contain/ A thing they understand.”70 The poster’s crazy colors and “mad designs” reflected a larger philosophical problem, as the image lacked an immediate, discernible message. Hyde’s poem is typical of numerous fin-de-siècle attacks on unusual and mysterious poster styles, suggesting the way that art for art’s sake gave rise to a powerful marketing technique.

These dynamics are conveyed, with a feminist twist, in Evelyn Sharp’s short story “A New Poster,” which appeared in The Yellow Book in 1895. Guests at a dinner table discuss a “new poster” that has been making a splash, “one of the new things, a scarlet background with a black lady in one corner and a black tree with large roots in another corner, and some black stars scattered about elsewhere.” The guests marvel at the fact that the poster seems so disconnected from the object it advertises—in this case, a fountain pen. The suave decadent artist (and, secretly, the poster’s creator) replies to their skepticism, “I suppose you would have a penholder and a fountain with no background at all? That would be quite obvious of course.”71 In the ensuing tale, the decadent poster artist—who seems to have been modeled on Beardsley—is revealed to be a mercenary fellow bent on seducing a lady for her fortune. The story recalls other fin-de-siècle feminist critiques of decadence as a bastion of male privilege and exclusiveness. But it also rehearses the widespread attacks on British art posters, portraying them as sinister and even fraudulent.72

When aesthetic formalism becomes a poster style, the commodity disappears: the advertisement offers a pleasure beyond use-value, catering to a discerning spectator whose aesthetic judgment of the poster blurs together with the knowing purchase of the commodity. The striking design elements of posters worked to limn a realm of taste and pleasure for a new implied spectator, one whose qualities, as I’ll now pursue, intersected profoundly with late-century philosophies of self and self-making.

Art Poster as Decadent Symbol: The Mobile and Degenerate Art

Advertising posters became incendiary objects in the urban landscape, combining aesthetics and commercialism such that they came to symbolize cutting-edge developments in both spheres. For this reason, late-Victorian critics often characterized posters by invoking notably decadent themes and images, whether conservative critics warning of cultural decay, or progressive critics embracing visions of a new world. Arthur Symons, one of the major arbiters of decadence in Britain, writes an important 1898 essay on Aubrey Beardsley that takes the advertising poster as one of its central images. For Symons, Beardsley’s style is best analogized to a new kind of mass culture, both adept and troubling:

[T]here has come into existence a new, very modern … kind of art, which has expressed itself largely in the “Courrier Français,” the “Gil Blas Illustré,” and the posters.… [Like] the quite new art of the poster …, [this is] art meant for the street, for people who are walking fast. It comes into competition with the newspapers, with the music-halls; half-contemptuously, it popularises itself; and … finds itself forced to seek for sharp, sudden, arresting means of expression. Instead of seeking pure beauty, … it takes, wilfully and for effect, that beauty which is … nearest to ugliness in the grotesque, nearest to triviality in a certain elegant daintiness, nearest also to brutality and the spectacular vices.… [I]n its direct assault on the nerves, it pushes naughtiness to obscenity, deforms observation into caricature.73

Symons’s ironic approach typifies the double-mindedness of decadence, with comparisons that both praise and malign. He personifies Beardsley’s daring style as an artist slumming it in dangerous, low-class neighborhoods, an extreme sensation-seeking enabled by the traversal of class boundaries. The poster itself embodies this traversal, an impure artform blending high culture and street life. Beardsley’s art, like that of other urban mass arts, takes on the stereotypically negative qualities associated with working-class people and neighborhoods, including “brutality and the spectacular vices.” The poster arts are inherently tainted by the street and the gutter. Beardsley wields the dark qualities of street-art “half-contemptuously,” a key descriptor showing how the decadent artist knowingly participates in an immoral, amoral visual world defined by modern capitalism and commerce.

While Symons is equivocal in his comments on Beardsley, diagnosing an uneasy alliance between new artforms and the vice-ridden street, Beardsley himself showed no such misgivings. In his short essay “The Art of the Hoarding,” published in The New Review in 1894, Beardsley gleefully and unapologetically celebrates the rise of the poster as the quintessential art of modernity. “Advertisement is an absolute necessity of modern life, and if it can be made beautiful as well as obvious, so much the better for the makers of soap and the public who are likely to wash.” Even while he makes a strong aesthetic claim for the poster arts, Beardsley also disdains merchant soap-makers and their unwashed public. “[M]ay not our hoardings claim kinship with the galleries, … (and, recollect, no gate money, no catalogue)?” He repeats the trope of the “streets as art galleries” common to many poster enthusiasts, but his ironic tone places him somewhat above the masses whom his art is supposed to elevate. With an eerie prescience, Beardsley foresees a proto-postmodern cityscape dominated by pictorial advertisements: “London will soon be resplendent with advertisements, and against a leaden sky skysigns will trace their formal arabesque. Beauty has laid siege to the city, and telegraph wires shall no longer be the sole joy of our aesthetic perceptions.”74 Of course, telegraph wires were never the “sole joy” of any Victorian aesthetic program. Beardsley perversely embraces media elements like advertising posters that other critics had condemned as an urban blight. His decadent vision takes a nihilistic pleasure in celebrating the triumph of a soulless commercialism, ushered in under the sign of advertising beauty.

Joris-Karl Huysmans, author of the breviary of decadence, also wrote to praise the posters of Jules Chéret using typically decadent terms. In “Chéret,” an influential essay appearing in a book of art criticism (Certains) in 1889, Huysmans singles out posters featuring pantomimes, circus dancers, and the erotic La Parisienne—the ecstatic woman who recurs across Chéret’s poster oeuvre. Huysmans summarizes the aesthetic: “M. Chéret conveys primarily a sense of joy, but joy as it can only be understood through abjection, a frantic and mocking joy, ice-cold as in the pantomime, a joy whose excess causes exhaustion, almost approaching pain.”75 Joy and pain, pleasure and abjection: Huysmans’s juxtapositions are typically decadent. Chéret’s figures, he says, are “neurotic,” “anxious,” and “almost satanic”—this last describing a pantomime clown bursting with a “demented, almost explosive joy.”76 He suggests that La Parisenne is a prostitute, a “woman of the people,” flirtatious, accessible, and eminently false.77 Despite the poster’s place in commercial culture, Huysmans celebrates it as a beautiful disease—an embrace that is itself shocking for the poster’s mercantile associations.

Beardsley and Huysmans gesture toward an idea of the art poster as a profound philosophical symbol. That understanding is explored, with polemical and eloquent acuity, by Maurice Talmeyr in his influential 1896 essay “L’Age d’Affiche” (“The Age of the Poster”).78 This essay, though widely quoted and discussed in both the nineteenth century and today, has never been analyzed as a key document of decadence.79 Yet Talmeyr’s resonant imagery gains its fire from recognizably decadent tropes—tropes that make the art poster into the pre-eminent emblem of a degraded modernity. In fact, he borrows imagery from Huysmans, even though Talmeyr writes to condemn rather than eulogize. (The two men were correspondents and longtime friends.)80 Talmeyr’s essay takes its place among other fiery denunciations of decadence—by Nisard, Nietzsche, and Nordau—whose perceptive intensity serves to etch the aesthetic in acid negatives. His attack grants the art poster such a weird, occult power that, when the American journal The Poster prints an English translation of the essay in 1911, it is edited and extracted to make it seem as though Talmeyr is actually a poster enthusiast.81 Again, this double-voiced discourse is a hallmark of decadent aesthetics, as the poster’s artful triumph occurs upon the stage of a broader cultural desolation.

For Talmeyr, advertising posters are the sign of an absolute ephemerality. Exposed to the elements, vandalized, covered over before they’ve even had time to dry: posters symbolize “the rapid, shaken and multiform life that carries us away.” In an older world, life was stable, slower-moving, made up of “peaceful properties” that changed little by little over the centuries.

Now you go to bed at night in a sleeping-car in Paris, and you have your hot chocolate the next morning in Marseille; you take off again … and learn, on returning, that you are ruined! You were a millionaire, but in millions that did not exist, and all you have left is your wardrobe, which you even forgot to pay for. (207)

Of this speeded-up, pleasurable, hollow roller-coaster of modern life “the poster is the continuous reflection, the incessant reverberation.” The poster

renders, by its indefinable colors, its perverse tones, its strangeness, all that this life holds and gives, in its brevity, disastrous see-saws, intense vanities, ephemeral frenzies, unhealthy efforts towards the sun and triumph … [T]he present life is … feverish and jagged, shimmering, multicolored, and is summed up in the poster. (208)

Talmeyr’s essay fulminates against the modern world created by commerce and technology—rapid trains and speculative finance, but also the phonograph, telephone, even the cinematograph. All of these are linked by a poetics of evanescence, epitomized by the poster’s flimsy paper medium.

The past, by contrast, takes on the solidity of stone. Talmeyr contrasts the admirable longevity of castles and cathedrals—“stone poems”—versus the modern poster, “the chateau of paper, the cathedral of sensuality,” whose pages have triumphed over stone (208–9). Even certain modern buildings are attacked as “monstrous and sumptuous posters,” from the Eiffel Tower to exhibition pavilions—each displaying “the same fantastical violence, the same effects of sportive and multicolored nightmares” (209). While church architecture is obsolete, “the true architecture today, the one that grows from palpitating ambient life, is the poster, the swarming of colors under which the stone monument disappears like ruins under teeming nature” (209). Talmeyr repeatedly mourns the lost concreteness of old stone monuments, sounding the familiar decadent theme of a culture falling away and degenerating over time. Cultural objects take on organic qualities, as churches and castles melt away under the eroding effects of the posters that cover them. Talmeyr again wields familiar decadent descriptors in labeling posters as “morbid, perverse, pestilential, malarial,” “unhealthy”: “a mobile and degenerate art” (215, 208, 210). The waning of culture happens like a disease; posters are therefore a diseased artform, a sign of decadent times. The poster serves as a master-metaphor for decadent contemporary values, embodying them both physically and metaphysically.

Talmeyr’s denunciations of modernity will sound familiar from other conservative nineteenth-century European prose writers—in England, John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle—who used scathing irony to hymn a lost medieval past while castigating modern advancements. Yet “The Age of the Poster” offers a distinctive fin-de-siècle slant with its focus on consumerism, modern pleasures, and a corrupt visual beauty. Talmeyr, a conservative Catholic, takes the advertising poster to define an age that has abandoned the patriarchal traditions of Church and crown:

[The poster] does not say to us: “Pray, obey, sacrifice yourself, adore God, fear the master, respect the king …” It whispers to us: “Amuse yourself, preen yourself, feed yourself, go to the theater, to the ball, to the concert, dance, read novels, drink good beer, buy good bouillon, smoke good cigars, eat good chocolate, go to your carnival, keep yourself fresh, handsome, strong, cheerful, please women, take care of yourself, comb yourself, purge yourself, perfume yourself, look after your underwear, your clothes, your teeth, your hands, and take lozenges if you catch cold!” (208–9)

The list produces a hilarious, caustic vision of the modern subject as constructed by the imperatives of advertisements. Consumer life is absurdly superficial, with its demeaning fixation on bodily processes; the content of advertisements presents a devastating picture of how modern people occupy their time and interests. Talmeyr pulls back to summarize the poster’s underlying metaphysics:

Born of individualism, … of appetites, egotisms, demands, caprices, sensuality, of the need for pleasure, … of intellectual nullity, futility, the acute cult of the self, of bored contempt for all that is not oneself, all this [the poster] must logically reproduce and render. (211)

The modern subject of the advertising poster, as Talmeyr analyzes him, is the epitome of a decadent: bored, pleasure-seeking, selfish, absolutely individualistic, paying allegiance to no greater social whole. Talmeyr’s imagery of aesthetico-political fragmentation is reminiscent of Paul Bourget’s famous account of Baudelaire’s “decadent style” as “one in which the unity of the book breaks down to make place for the independence of the page, in which the page breaks down to make place for the independence of the sentence and in which the sentence breaks down to make place for the independence of the word.”82 Both Bourget and Talmeyr imagine a decadent artform whose style organically encodes an atomistic politics of individualism, such that the art itself seems alive, interchangeable with its makers and consumers. For Bourget this political art is desirable for its aesthetic individualism, its challenge to hierarchy and conformity. But for Talmeyr, the art poster signals the rise of anarchy and the oncoming collapse of all traditional social bonds.

For all of Talmeyr’s polemicism and fire, his study of posters chimes with conclusions drawn by more modern critics of advertisements. Like Michael Schudson, Talmeyr too perceives advertising as limning a fantasy world created by the markets that is oriented strictly around individualistic desire and private pleasures.83 Unlike Schudson, Talmeyr chooses to embody this fact in the decadent image of the prostitute, as incarnated by Jules Chéret’s breezy and alluring chérettes.

The insolent poster … is equipped for war, decked out for the street, done up for the promenade or the theater, and her very nudity, when she is naked, is a contrived, painted, whitened nudity, a cosmetic nudity. She is … a creature who is there to “do business.” (213)

Talmeyr’s point goes beyond a mere hostility to sex and loose women.84 If the poster is beautiful and eye-catching for the sake of a sale, then it exists without any higher moral, religious, or institutional purpose. The poster participates in capitalism’s broader amorality, exploiting human desire in order to make money. Art posters are intrinsically immoral, in their painted, artificial fashion, because they attract individuals by way of the eye and visual pleasure. Talmeyr acknowledges the dispiriting truth that a conservative, moral, subdued poster will inevitably be an aesthetic failure (210). The decadent figure of the prostitute, then, serves to make a larger comment about aesthetics: the gorgeous artistry of posters signals the triumph of the market, alongside the death of noble or worthwhile beliefs.

If Talmeyr’s essay reads as decadent, it’s because he makes many of the same cultural observations as those penned by canonical decadents, like Huysmans in À Rebours. Decadent philosophy, too, acknowledges the death of higher powers, the loss of Christianity and other forms of collectivity, and the turning to a grim-yet-gleeful individualism. Decadent self-making occurs in the midst of cultural fragmentation and collapse. Among hints of nihilism and nothingness, the only value to be found is in individual human experience—sensory perception, “fever,” exciting modernity dissolving into ephemerality. Indeed, the profound ephemerality that Talmeyr ascribes to posters resonates with the Heraclitean flux of Walter Pater’s aestheticism, defining modern experience as nothing more than the flow of intense impressions. Talmeyr’s posters flame up and die just like Pater’s sensations, constantly erupting and dissolving in perception. Beauty is a key motif in Talmeyr’s essay, describing posters’ shimmering and multicolored effects as techniques to stimulate the spectator’s amoral desires. Art-for-art’s-sake, the avant-garde European philosophy celebrating visual form and erotic beauty over moral tales or traditional norms, is a crucial aspect of the poster’s inherent amorality. It is striking that, even while Talmeyr writes to denigrate the art poster in the extreme, he still also repeatedly grants its beauty and aesthetic power. His aesthetic sense expresses itself in his essay’s own indelible phrasing and imagery, using the poster as a symbol to diagnose the essential condition of modernity:

Triumphant, exultant, brushed, posted, torn up in a few hours, and continually sapping our heart and soul by its vibrant futility, the poster really is the art, and almost the only art, of this age of fever and laughter, of struggle, of ruin, of electricity and oblivion. (216)

Modern capitalism has destroyed traditions and invited oblivion, but it has also opened the door to beauty, electricity, and fleeting pleasures—an opinion that seems to have been scripted by a decadent writer, balancing on the knife-edge between beauty and decay.

Philosophies of the Decadent Commodity

The story of decadence changes when we observe its surprising imbrication with commercial culture via the art poster. The more familiar account sees decadent artists as pitched against bourgeois modern life and its superficial material rewards. Matei Calinescu writes of how decadent artists in France were

conscious promoters of an aesthetic modernity that was, in spite of all its ambiguities, radically opposed to the other, essentially bourgeois, modernity, with its promises of indefinite progress, democracy, generalized sharing of the “comforts of civilization,” etc. Such promises appeared to these “decadent” artists as so many demagogical diversions from the terrible reality of increasing spiritual alienation and dehumanization. To protest precisely such tactics, the “decadents” cultivated the consciousness of their own alienation, both aesthetic and moral, and, in the face of the false and complacent humanism of the day’s demagogues, resorted to something approaching the aggressive strategies of antihumanism.85

Calinescu’s characterization underlines a contradiction inherent in the notion of a decadent media culture. If decadent artists opposed all the commercial successes of an advanced bourgeois society, then surely advertising would be among the worst offenders in creating a “false and complacent humanism” surrounding the new consumer paradise. This decadent attitude is on full view in Huysmans’s novel À Rebours, where the protagonist Des Esseintes retires to the solitude of his château in order to escape the despicable, trade-obsessed lifestyle of the petit bourgeois.86

Yet the surface opposition between the two kinds of aesthetic and functionalist codes only disguises some of the ways that decadent philosophy could coincide—at times profoundly—with a new middle-class identity organized around consumerist choice and leisure time. The decadent world was filled with beautiful and strange objects, as the exquisite self was externalized into the carefully decorated interior. This process of materialization signified a kind of commodity aesthetics set amid the expansion of consumer culture in the West. “Decadence” in the contemporary lexicon still connotes an excess of materiality, a survival from European culture’s self-diagnosis in the 1890s, when the advances of technological and imperial modernity resulted in a perceived over-civilization embodied by a surplus of goods. It is no coincidence that Marxist critics after the 1890s accused the Western world of decadence in a sense that took material luxury as the sign of incipient ruin.87 Max Nordau, the influential German-Jewish theorist of Degeneration (1892; English trans. 1895), saw the end of the West writ large in the inter-linked phenomena of decadent art and modern consumerism. In his elaborately rancorous account, Nordau assails a degenerate aesthetic culture for its faddish addiction to objects, attacking “[t]he present rage for collecting, the piling up, in dwellings, of aimless bric-à-brac, which does not become any more useful or beautiful by being fondly called bibelots.” Nordau diagnoses aesthetes with a shopping addiction, “an irresistible desire among the degenerate to accumulate useless trifles.” He names the disease with a neologism coined by another scientist: “‘onio-mania,’ or ‘buying craze.’”88

Nordau’s anxious vision of decadent consumption was echoed in America by Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), an attack on Gilded Age excess. Veblen scornfully describes how “conspicuous consumption” and “conspicuous leisure” have led to cultural decay, especially by sapping gentlemen of their masculine strength. The “successful, aggressive male” has given way to the man of leisure, a recognizably decadent figure whose greatest task is to cultivate his “aesthetic faculty,” especially in discriminating diverse “consumable goods.” Veblen’s scathing, deadpan humor comes through in his list of commodities the man of leisure is now called upon to judge; these include “manly beverages and trinkets,” as well as “weapons, games, dancers, and the narcotics.”89 Modern life has brought about a devastating emasculation by privileging consumption; a gentleman’s class status will now be maintained by his connoisseurship of “manly trinkets.” Though Veblen’s study has gained a theoretical import beyond its moment of composition, the text can also be read as a key document of the decadent moment, linking aestheticized consumption to cultural degeneration.

Both Nordau and Veblen invoke the archetype of the decadent male who surrounds himself with useless goods, a connoisseur and collector addicted to the material world. They produce a darkly negative version of the same character lionized as anti-hero by Huysmans and Wilde. Immersed in aesthetic culture, the collector forms his identity via the objects with which he surrounds himself. Of course, the exquisite artifacts of the decadent lifestyle—exotic items not available in any local store—make for a striking contrast with the actual products sold in the new consumer culture, such as soap, cocoa, face cream, and cure-all pills. Yet the object-logic of decadence mirrors that of the emergent advertising culture in the idea that commodities could offer a radically new mode of self-creation, departing from traditional sources of identity in birth and social class. The consumer world of the late nineteenth century was itself moving toward a more decadent model; as many critics have noted, middle-class values of thrift and diligence were giving way to a more hedonistic embrace of the material world.90 In a new development since mid-century, people were no longer to be identified by what they produced, but by what they consumed. Judith Williamson’s classic study of modern advertising resonates with these nineteenth-century developments. She writes of how advertisements invoke an almost existentialist creed in their utopian promise of identity creation.

In buying products with certain “images” we create ourselves, our personality, our qualities, even our past and future. This is a very existentialist concept … We are both product and consumer; we consume, buy the product, yet we are the product. Thus our lives become our own creations, through buying.91

Williamson’s vision of existentialist self-making through advertisements corresponds aptly with the dark glee of decadence, viewing the self as a work of art in the face of modern cultural decay. Even while decadent artists often chose to celebrate aristocratic traditions and forms, then, their liberated vision of artificial self-creation was fundamentally middle-class, a version of the self-made man familiar from Victorian treatises like Samuel Smiles’s Self Help. Though decadence set itself against the rosy celebrations of progress tied to bourgeois self-improvement, its portraits of perverse self-development were a dark mirror of the same mainstream ideologies it set out to critique.

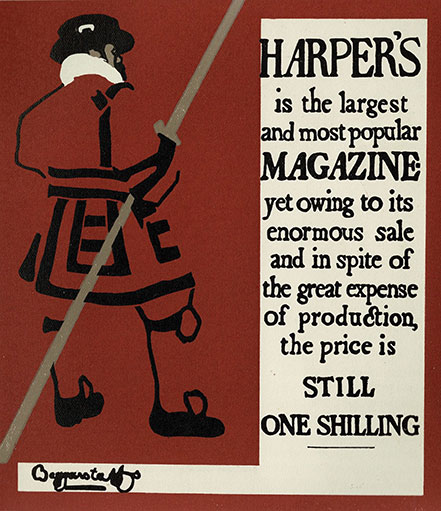

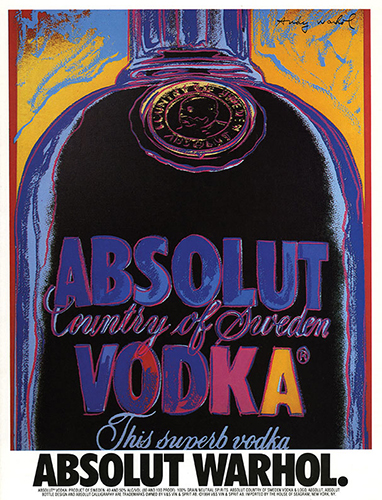

Decadence also approached advertising ideology by making itself a commodity in the 1890s, with its own marketing plan, branding, and fashionable popularity. The very “yellow” of The Yellow Book was the distinguishing marker of a sensationalist product that enjoyed brisk sales. Richard Le Gallienne’s satirical 1896 essay “The Boom in Yellow”—working very much in the mode of decadent irony—ridicules decadence’s fashionable pretensions, describing a “boom” that has created a fad for all kinds of yellow objects. Le Gallienne explicitly links The Yellow Book’s commercial appeal to the new tactics of advertising posters:

Bill-posters are beginning to discover the attractive qualities of the colour. Who can ever forget meeting for the first time upon a hoarding Mr. Dudley Hardy’s wonderful Yellow Girl, the pretty advance-guard of To-Day? But I suppose the honour of the discovery of the colour for advertising purposes rests with Mr. Colman [the mustard magnate]; though its recent boom comes from the publishers, and particularly from the Bodley Head. The Yellow Book with any other colour would hardly have sold as well.92