3

Illustration

Orients of the Self: Bible Illustration and the Victorian World Picture

Machine-Made Aura

The illustrated book was a classic, distinctive, and multiform kind of Victorian new media. Books had been illustrated before the nineteenth century, but these were usually expensive, luxury items for the ruling classes. Only in the mid-nineteenth century did new technology enable the mass printing of illustrated books—as well as newspapers and magazines—at prices that many more people could afford. “Illustration” is an aesthetic keyword strongly associated with the nineteenth century. In later years, twentieth-century critics would look askance at illustration’s promiscuous mixing of word and image; this fusion contravened the modernist dogma of pure medium. Literary books for adults today largely appear without illustrations; picture-books for adults seem like an outmoded print phenomenon of the past. Yet Victorian illustration was a complicated and long-reaching media effect that entailed more than merely interleaving books with pictures. In this chapter, I argue that illustrations engaged in imaginative acts of world-building and world-making: they concretized visions of space, place, and self whose after-effects are still with us, albeit in slightly different forms.

My account of illustration pushes against usual understandings of the term. For literature scholars, an illustration usually suggests an image with a lesser relationship to a text. Words occupy a position of primacy, especially in works of literature, while images function as an afterthought, a belated attempt at concretization subordinated to the textual original.1 This approach offers many revelations within the literary sphere, but it also constrains our notion of Victorian illustration, which extended far beyond literature: many kinds of books and magazines contained images, of which literature was merely a subset.

Art historians, meanwhile, have approached the subject with a fine-art sensibility, focusing on avant-garde illustrators like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais.2 These Pre-Raphaelite painters are famous for elevating illustrations to the level of autonomous artworks, creating images that are distinct from the text and equally artistic, with all the hermetic formal perfection ascribable to high art. Fine-art criticism has studied a small canon of illustrators who crafted images for Fine Art Books, Victorian precursors to modern-day, opulent coffee-table art books. Scholars who study illustration as a fine art implicitly distinguish their subjects from more patently commercial printing productions, which used illustrations as a marketing tool to sell books.3 Accordingly, these accounts rarely consider more prolific, mass-cultural objects or illustrators. Artists such as Gustave Doré, the most popular and influential illustrator of the later nineteenth century, are strikingly under-studied.

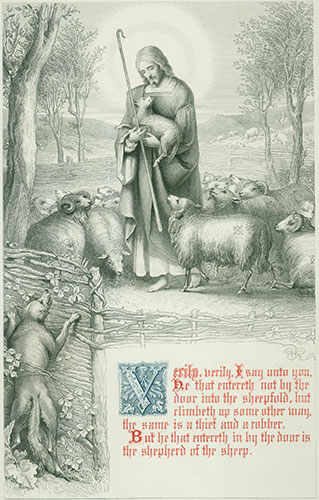

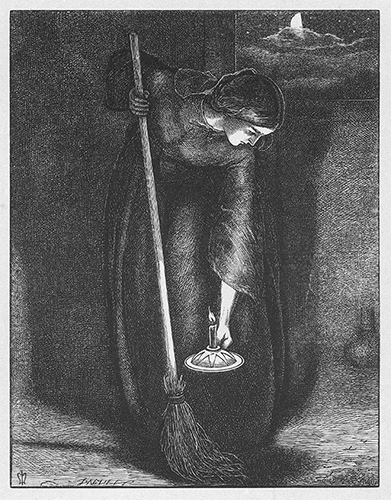

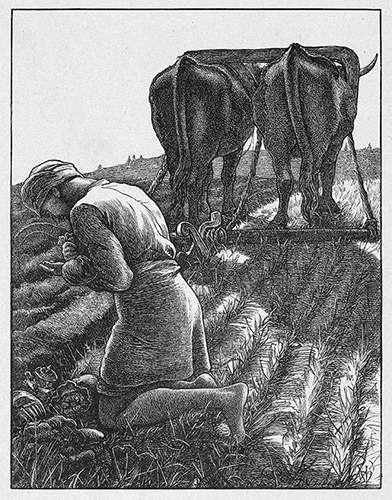

Rather than seeing illustration as elucidating a text, or glimmering in its own autonomous artistic sphere, I analyze it as a major interactive, world-building activity of the nineteenth century, permeating many different kinds of books, not just literary or Fine Art productions. A different understanding of illustration comes to the fore in my choice of object, the Victorian Bible. Any respectable middle-class Victorian home would have contained an illustrated Bible, often a deluxe “family” edition filled with illustrations, notes, and all manner of extra materials. The illustrated Bible was likely the single most popular illustrated book of the nineteenth century. It was a central object in the Victorian parlor, with elaborate rituals for its reading and study; as such, it is an exemplary piece of visual culture, defining the way that many middle-class Victorians consumed illustrations. Pictures in a Bible signify differently from pictures in a novel: instead of interpreting a suspense-driven product, an illustrated Bible—where readers already know the story and the outcome—finds suspense and desire in the images themselves, in the choices for world-formation and imaginative projection. The appeal of the book lies in the way that it visually constructs and animates the world of ancient Jews and Christians. Bible illustration thus models the way that pictures, accompanying words, opened out into unknown places and times, crafting solidities and defining worlds out of increasingly fraught religious materials.

The illustrated Bible shaped worlds with a porous sensitivity to other modes of Victorian knowing and seeing. It was a heterogeneous object, a series of layers or palimpsests, intertextual and intervisual with other mass-cultural forms. Illustrated Bibles generated commentaries on Victorian notions of science, history, geography, empiricism, and materiality: they fashioned a Victorian “world picture,” in Martin Heidegger’s resonant phrase. “World picture” translates the term Weltbild, a philosophical concept that Heidegger used to describe the pre-structured human comprehension of the world-as-picture, as something to be framed, surveyed, used, and acted upon. For Heidegger, “the fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as picture.”4 Heidegger’s “world” is a defamiliarized place, understood not as the natural unfolding of space and time but as an artificial schema, connoting art-making, constructedness, and the action of human perception on the scene. There is no innocent world apart from the frames and preconceived notions that we impose upon it. Though Heidegger’s essay largely theorizes the rise of modern science, its terminology of “conquest” and “mastery” also evokes a political dynamic inflecting Western eyes.5 Envisioning the world-as-picture also implicitly accommodates modern imperialism, encouraging humans to strive to conquer and control the world’s various territories. As the chapter pursues, the Bible is a crucial site for analyzing political constructions of the Victorian world picture, standing as it does at the locus of past and present, East and West, British and foreign, Protestant and Jewish.

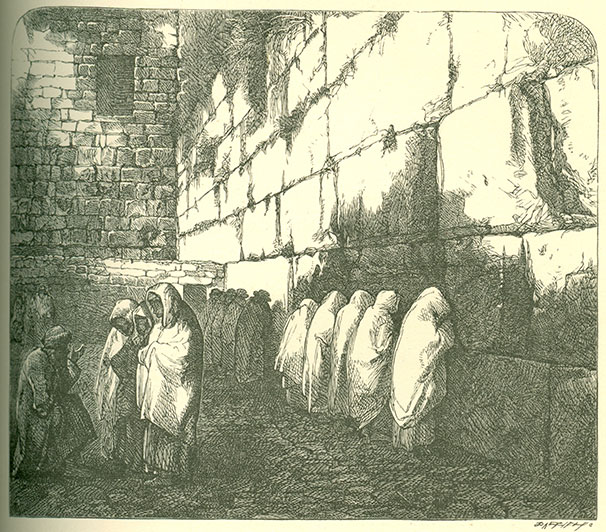

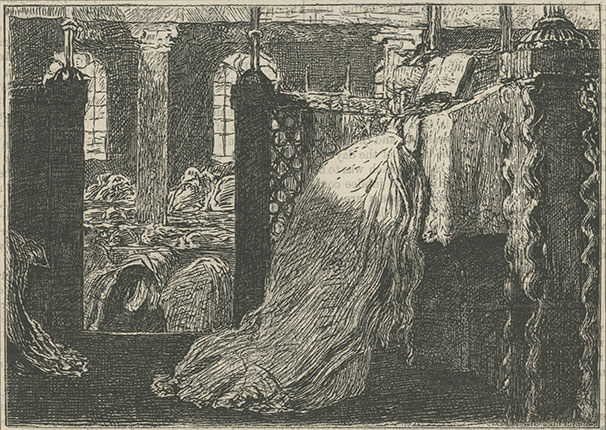

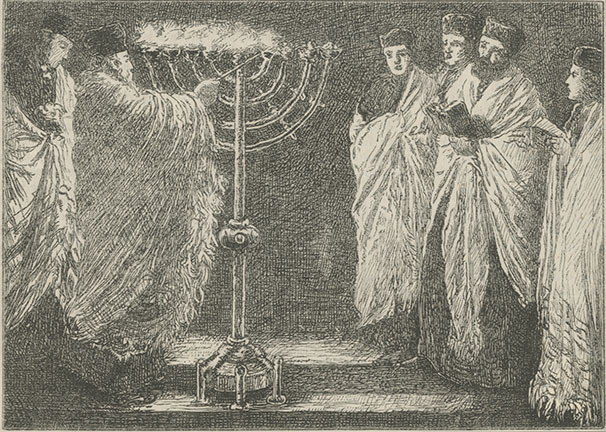

Bible illustrations offer a revealing entrée into an ever-shifting Victorian world picture. They played a key part in making the Bible “English,” even while raising larger questions about Christianity’s foreign roots. Many of the Bible’s exotically decorated scenes appear to operate in a classic orientalist mode as described by Edward Said, in which the West projects a fantastical otherness onto a luxurious, sensuous East. Yet the illustrated Bible challenges this conception of the Victorian world picture, since the Christian imagery demanded a problematic alignment of self with other. The resulting illustrations create what I call “orients of the self”: they depict destabilizing scenes hovering somewhere between East and West, ancient and modern, Jewish and gentile, patriarchal and democratic, and magical and rational.

Though religious illustration was central to the Victorian household, this imagery has received only limited scholarly attention. Colleen McDannell explores some of the reasons for the critical neglect of Christianity’s material aspects, suggesting that scholars typically adhere to a commonplace distinction between “the sacred and the profane, spirit and matter, piety and commerce.”6 From this perspective, a marketed commodity—like a profusely illustrated Bible—would seem out of place in the disembodied realm of true religion. Twentieth-century theorists of religion like Emile Durkheim, writing in Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912), produced an influential narrative of the West’s increasing modernization and secularization, in which the realm of the sacred—transcendental, awe-inspiring, and guarded by elder initiates—was walled off from the world of the profane and the workaday, populated by women, children, and working-class people.7 These values are still evident in scholarship on Victorian religious discourse, which has tended to focus on the controversies that roiled elite intellectual circles—Darwinism, the “Higher Criticism” investigating the Bible as a historical document, and the Tractarian and neo-Catholic movements—while omitting other forms and practices of religion.8 Yet Victorian religion consisted of more than heated doctrinal battles waged in pamphlets and treatises. It was also the lived faith of everyday people, as seen in its material traces.

Acknowledging that the illustrated Bible is a commodity might seem to deflate its sacred value. But if we presume that a commercial purpose taints any religious object, then, as Colleen McDannell argues, “we will miss the subtle ways that people create and maintain spiritual ideals through the exchange of goods and the construction of spaces.”9 McDannell’s point seems especially pertinent to the study of illustrated Bibles, which might be cynically perceived to empty out religious feeling in favor of crass commercialism, with sensuous renderings of melodrama, violence, slavery, and other sensational biblical subjects. Yet these aspects of the illustrated Bible performed important political and religious functions, as the chapter argues, scripting a modern liberal epic by which British Protestant readers could identify with the tribulations of ancient Jews. In other words, the illustrated Bible’s commercial and religious contents were deeply entwined. Embodied violence was a fundamental part of Victorian Christianity; it also sold well. The chapter’s conclusion looks at ways that this sometimes disturbing embodiment continues today, in ongoing spectacles of modern Christianity. I track how the spiritual and the sacred express themselves in visual and embodied forms, especially those courting magic, theatricality, and spectacle. It is no coincidence that Gustave Doré, the most popular Victorian Bible illustrator, had an outsized influence on modern cinema.

Contemporary scholarship on the Victorian Bible emphasizes its fragility: in the wake of historical and scientific research, especially that of the German Higher Criticism, Victorian intellectuals were forced to confront the Bible’s instability as a religious document. The foundational scriptures were revealed to be not set in stone, but a murky, ambiguous set of signs, open to interpretation and reinterpretation.10 In some ways this multiform sensibility underlies the project of Bible illustration, in which each new book offered a different version of biblical truth. Having said this, illustrated Bibles proved surprisingly impervious to the challenges posed by new Bible scholarship. In fact, Bibles often marketed themselves by promising more accurate, more detailed illustrations of the history and customs of the Holy Land—a scientific and empiricist worldview that was seen as the perfect counterpart to the spiritual truth of Christianity. The modern-day sense of science opposing religion did not apply in the case of most Victorian Bibles, which presented the two modes as complementary rather than competing.

New historical approaches strengthened the Bible’s “reality effect,” making its places and times feel more real for its readers. George Eliot’s famous realist manifesto, in chapter 17 of Adam Bede (1859), makes its claim by attacking the false, beautiful types of religious illustration, the Madonnas and angels that seem inauthentic and unreal when compared with more homely peasant figures. As Eliot’s manifesto suggests, religious illustration itself was a proving ground of the real. (I discuss this manifesto at length in Chapter 2.) “Realism” is an auxiliary keyword in the chapter, befitting a concept of illustration that emphasizes its moves toward visualization, realization, materialization, and embodiment.

The chapter begins by delving into the meanings of “illustration,” especially as they pertained to the Victorian illustrated book. I then move to the specific history of the illustrated Bible, focusing in particular on Cassell’s Family Bible (1859–63), the best-selling Bible of mid-century.11 The copious illustrations of Cassell’s Bible marshaled all the latest scientific and geographic research into the Holy Land to produce a phantasmagoric, fantastical spiritual realm, blending together clashing systems of knowledge in the manner of a Foucaultian heterotopia. The visual culture of the Holy Land showed the influence of spectacular archaeological discoveries in the Middle East, leading to anachronistic yet compelling origin stories that superimposed religious history onto the history of Western nation-states. The Bible’s numerous political stories of nation-building among ancient Jews became available for identification and appropriation by British Protestant readers, especially in the illustrated Bible of Gustave Doré: these images depicted righteous, violent heroes emerging triumphant against larger armies in visual narratives I identify as a liberal epic. From rousing battle scenes I turn to the intimate, domestic realism of John Everett Millais’s illustrations to The Parables of Our Lord (1863), which controversially updated the parables to modern Scotland, with strange and disconcerting results. A late section considers the visual culture surrounding ancient and modern Jewishness, which epitomized the problems of self and other haunting the Victorian Bible. The conclusion ponders “the persistence of illustration” in the long influence of Victorian Bibles upon our modern mediascape, from televangelical empires to American theme parks recreating “The Holy Land Experience.”

This chapter brings together two terms usually associated with Walter Benjamin: mechanically reproduced artworks and “aura,” the burnished, spiritual quality he attached to the singular, original work of art. Benjamin predicted that the phenomenon of aura would diminish with the rise of mechanical reproduction, as the singular artwork would be replaced by a flood of cheaper, more accessible copies.12 This chapter moves in a different direction: I propose that mass culture, kitsch, and other disreputable media forms are not incompatible with values of authenticity, belief, or aura. Even while illustrated Bibles fabricated new worlds that were intellectually impossible, those worlds were compelling creations, deeply realized and powerfully animated, inviting authentic experience from their readers, and demanding our scholarly attention.

Theorizing Illustration: Enlightening, Expanding, Remaking

The earliest meanings of “illustration” were, fittingly, spiritual. Rooted in an idea of luster, or light, the word connoted religious illumination or enlightenment, “filled with light,” in usages dating back to the fourteenth century (OED). “The person that receyueth suche illustracyon or lyght, is all quiete and restfull: bothe in soule & body” (OED, 1526). The word also described an emanating light, as in a 1631 sermon of John Donne’s in which a devout priest’s fingertips exude “such an illustration, such an irradiation, such a coruscation” that the priest’s fingers can serve as candles in the night.13 Illustration also connoted elevation to fame, or, especially in the eighteenth century, the act of making something clear or evident to the mind. To illustrate something was to shed metaphorical light on it. This usage featured notably in eighteenth-century Bible titles, as in the 1771 Complete Family Bible, whose subtitle boasted: With a Complete Illustration of All the Difficult Passages; Wherein All the Objections of the Infidels are Obviated, the Obscure Passages Elucidated, and Every Seeming Difficulty Explained; Together with Notes Historical and Critical.14 The metaphoric usage of illustration, comparing thinking to seeing, reflected eighteenth-century philosophies that modeled the mind as a gallery of pictures. In Enlightenment thought, illustration stood for a figurative kind of vision characterized by properties of reason and clarity.

Only in the early nineteenth century did illustration take on a distinctive pictorial sense, referring to the visual embellishment of a text. An early pictorial usage appears in the title of Westall’s Illustrations to the Works of Walter Scott (1817) (OED)—an unsurprising example, given Scott’s role in establishing many of the commercial practices associated with modern authorship.15 As an adjective, the word “illustrated” first described text accompanied by pictures in 1831, with reference to a magazine article (OED). The Illustrated London News—the first pictorial newspaper in the world, as I discuss in Chapter 2—was founded in 1842, at which early date its title would have presented readers with a striking neologism. That “illustrated” books and newspapers only entered the English lexicon in the 1830s highlights the profoundly Victorian provenance of illustration, a newly popular way of seeing, reading, and consuming culture made possible by advances in reproductive print technologies.

While books in the 1830s were still luxury commodities for most people, by the end of the century lower costs and the broader industrialization of culture had given rise to a mass reading public. Richard Altick, in The Common Reader, outlines some of the familiar generative circumstances, such as an expanded railway, growing urban populations with concentrated book markets, and a better-educated populace with more disposable income and leisure time.16 Illustrations added an alluring element to book printing, and became newly affordable as sequential technologies allowed for ever-larger print runs at greater speed and lower cost across the nineteenth century.17 Plate technology was key, because it determined how many copies could be struck before the plate’s image was deformed by the constant pressure of the printing machine. Copper, steel, and then boxwood offered increasingly durable plate technologies as the century progressed. Relatively soft copper plates, in use since the eighteenth century, could produce 120 copies from a single plate, while a steel plate could generate 1,200 copies.18 Steel engravings adorned new Victorian media such as the illustrated annuals of the 1830s and 1840s, elegant productions made by and for women that included Heath’s Book of Beauty or The Keepsake. These costly items, bound in silk or leather, featured delicate, steel-engraved reproductions of paintings accompanied by woman-authored poetry.19 They quickly became outmoded with the rise of wood engraving, whose productions were made more swiftly and cheaply.20 The “golden age” of Victorian illustration—known as “the sixties,” but stretching from approximately 1855 to 1875—emerged out of the unique attributes of wood engraving, whose robust technology enabled greater circulation numbers even while an element of hand workmanship bestowed the stamp of fine art.21 Unlike its predecessors, wood engraving allowed for pictures and text to be mingled on the same page, creating close entwinings of word and image. In the 1880s, wood engraving was again superseded by photographic technology in “process blocks,” and the hand of the engraver became unnecessary as the image could be reproduced directly onto the metal printing plate. Once photographic technologies came widely into book production, to put it slightly reductively, illustrated book-making at the fin-de-siècle divided into cheap, mass-circulated items versus the hand-made, expensive, and collectible volumes produced by Morris’s Kelmscott Press and other “revivalist” operations.

The books and magazines of illustration’s golden age flourished under the emergence of a new kind of entrepreneurial editor, a businessman who oversaw collaborations between myriad artists and engravers to create a single book or magazine issue. Charles Knight, John Cassell, and the Dalziel Brothers combined business savvy with artistic leanings to produce a range of illustrated publications. Not coincidentally, despite the secular nature of most of their works, all three coordinated the production of large-scale illustrated Bibles. The Dalziel Brothers not only commissioned and organized books but also engraved their own images, adding their name to numerous titles, such as The Dalziels’ Bible Gallery. The artistic effect of this business arrangement, as Lorraine Janzen Kooistra points out, was to create books with very heterogeneous styles, a hodgepodge or hybrid of old and new, conventional and experimental.22

The rise of illustrated books and periodicals was a financial boon for many Victorian artists. In the realms of both fine art and religion, pure forms of art or devotion might seem sullied by acknowledging the pecuniary motives of practitioners or makers. Yet many canonical Victorian artists, some of them known as avant-garde innovators, supported themselves financially by illustrating commodified, mass-marketed books and magazines. Illustration’s reputation as a degrading kind of hackwork, especially for mass-circulated pictorial magazines, persisted late into the twentieth century. Fine-art collectors regularly defaced periodicals with Pre-Raphaelite illustrations, cutting out the pictures to mount and frame them separately.23 These collectors were expressing a sentiment with Victorian roots: nineteenth-century critics with allegiances to an elite high culture often disparaged illustration as low or vulgar. A sonnet by Wordsworth in 1846 titled “Illustrated Books and Newspapers” expresses a typical attitude of aesthetic disdain:

Now prose and verse sunk into disrepute

Must lacquey a dumb Art that best can suit

The taste of this once-intellectual Land.

A backward movement surely have we here,

From manhood,—back to childhood; for the age—

Back towards caverned life’s first rude career.

Avaunt this vile abuse of pictured page!

Must eyes be all in all, the tongue and ear

Nothing? Heaven keep us from a lower stage!24

Wordsworth, who had once been the eloquent spokesman for the common language of the rural poor, here takes on the role of crotchety cultural conservative, deploring the recent popularity of mass illustrated publications. “Tongue and ear” stand for a lofty literature and high culture, sunk now by attachment to a crude, primitive, and sensual visuality. Wordsworth’s implicit gendering of a masculine word versus a feminized image can be traced all the way back to Lessing’s Laocoön (1766): the portrayal of images as suspiciously sensuous, in contrast to poetry’s more respectable transcendence, has its roots in Enlightenment discourses elevating the mind over the body.25 The inaugural 1842 issue of the Illustrated London News echoes Wordsworth’s gendered imagery when it declares: “Art … has, in fact, become the bride of literature.”26 Of course, for the ILN, the wedding of the two media is a positive development rather than a regression back to the era of cavemen.

Despite the disapproval of some cultural critics, illustrated books and magazines became dominant media in the nineteenth century. Illustration might serve the purposes of visual pleasure, beauty, or entertainment; readers enjoyed the illustrated book’s visual acts of concretization, revivification, and animation. Book historian Richard Maxwell reformulates Walter Pater’s famous dictum to suggest that all the arts in Victorian Britain at some point “yearned to achieve the condition of illustration,” whether paintings, music, prints, or realist novels.27 An eros of illustration inspired bookmakers to reprint and remake the same texts repeatedly, with different pictures, bindings, fonts, and formats. In the case of the Bible, the same stories, verses, and parables were retold and reimagined over and over again, in myriad different visual versions. These illustrations invite a scholarly approach that expands beyond the typical questions of fidelity to a controlling text, as each illustrated version offered a new remaking of an envisioned world.

Even while new technology enabled illustration’s increasing popularity, that popularity was also linked, paradoxically, to the allure of medievalism and other pre-industrial forms of culture. Victorian book artists deliberately copied the styles of medieval illuminated manuscripts, emulating the hand-made codex format. Examples ranged from the elaborate pictorial capital letters opening Thackeray’s chapters of Vanity Fair (1847–8) to the faux architectural elements of Phiz’s covers for Dickens serials.28 The transition from illuminated manuscripts to mass-produced books was mediated by illustrated books that imitated medieval styles. It is easy to condemn these machine-made books for their blatant inauthenticity. Walter Benjamin uses a scathing irony to describe similar incongruous juxtapositions in The Arcades Project, pointing out the absurdity of Victorian iron-ribbed buildings adorned with Gothic ornaments, or modern, glass-plated exhibition halls housing hand-crafted neo-antiquities. Yet the nineteenth century’s unlikely amalgamations can also be read as expressions of profound desires, combining a genuine yearning for a lost history with a playful celebration of the triumph of mass dissemination. The industrialization of culture is often scripted as an artistic disaster, signaling the end of authentic, hand-made materiality in exchange for a flood of cheap, poorly made wares; but this reductive account (for all of its kernel of truth) misses the vibrancy and vitality of some forms of mass culture, which offered broad audiences a host of eccentric or unlikely pleasures.

Despite the fakery entailed by the illustrated book’s implicit medievalism, that backwards look also had a serious and suggestive religious aspect, harkening back to a pre-Reformation Catholicism, with its overawing, mystical visual element. Catholicism’s iconophilic visuality traditionally expressed itself in the imposing architecture of cathedrals, in niche sculptures and in carved ornaments, all consumed as part of the mass experience of cathedral worship. Moving from an actual cathedral to the illustrated book’s “pocket cathedral,” in William Morris’s suggestive phrase, highlights the way that mass visual culture adopted elements from Catholic traditions—using images as a central part of cultural literacy—while producing a devotional experience that was miniaturized, individualized, made portable, and brought into the home. In effect, the illustrated book can be seen as a Protestant version of Catholic styles. On the one hand, the Victorian suspicion of illustrations in some quarters can be traced to a lingering Protestant iconophobia, or to an even older Old Testament prohibition against the worship of idols. At the same time, however, the massive popularity of religious illustration shows how the wild Victorian enthusiasm for visual culture trumped most scruples regarding the use of pictures for sacred purposes.

While religious illustration might seem a distinct wing of Victorian publication, in fact this media emerged as part of a larger process of nineteenth-century literary canon formation. Dalziels’ Bible Gallery (1881) or the Doré Bible Gallery (1879) were grand illustrated books whose antecedents can be traced all the way back to John Boydell’s “Shakespeare Gallery” of the 1790s. Boydell was the engraver-entrepreneur who launched the first multimedia illustration project: he decided that a profit could be made by staging a work of illustration over multiple media platforms.29 His versions of Shakespeare’s plays included a folio of engravings, a set of elaborate illustrated books, and a public gallery displaying the original paintings in a fashionable London neighborhood. Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery quickly gained imitators in the 1790s in Macklin’s Gallery of the Poets and Fuseli’s Milton Gallery. Milton’s Paradise Lost, which made the book of Genesis into an epic poem, blurred the line between the Bible and great literature, making Milton’s work ripe for profitable illustration. The printseller Thomas Macklin commissioned a lavish illustrated Bible (1800) using many of the same artists who illustrated his Gallery of the Poets, again showing the entwining of the religious with the secular. The process of British literary canon-building inevitably came to include a “Gallery,” linking visual and verbal collections and transforming the illustrated book into a metaphoric, quasi-architectural space for public display.

The commodification of religious illustration in the 1790s worked to align the Bible with writers such as Shakespeare and Milton. Just as Shakespeare was transformed from a popular playwright into a great British author, so too the Bible was adopted for British nationalism and construed as a great national work of literature, worthy of illustrated editions. (Of course, transforming the Bible into a foundational work of English literature would also prove problematic, given its Semitic origins—an issue that comes to the fore within the illustrations, as I discuss below.) The idea of a canon itself entails an overlap of the secular and the sacred, originating out of the Catholic tradition to describe a set of holy books. Literary canon-building continued to occur during the nineteenth century via the process of illustration, as Victorian publishers looked to capitalize on the rising popularity of touchstone texts. At mid-century, wood-engraved gift books interlaced the religious with the secular in anthologies such as Lays of the Holy Land (1858) and English Sacred Poetry of the Olden Time (1864), which included poetry by Milton, Byron, Scott, and other luminaries. Even while the illustrated religious book was a special kind of commodity, then, uniting the sacred with the sensuous, it also partook of the sacralization of other kinds of non-religious British writings deemed worthy of picturing.

Victorian Bibles: Commodity, History, Palimpsest, Collage

Victorian Bibles were manufactured as part of a booming commercial practice. By 1861, nearly 4 million Bibles were being published per year in Great Britain.30 London’s massive book emporia stocked tens of thousands of Bibles, prayer books, and other religious print items. The Illustrated London News advertised bookstores such as John Field’s “Great Bible Warehouse,” near Piccadilly Circus, boasting an inventory of 50,000 religious publications.31 The mass production of Bibles accompanied a missionary zeal to spread the word, among both Britain’s working classes and peoples of the colonies. The British and Foreign Bible Society, founded in 1804, used modern media advancements to produce increasingly cheap Bibles, aligning Bible distribution with new transportation networks, especially the railway.32 Perhaps ironically, the Victorian Bible existed on the cutting edge of modernity, and was even deemed worthy of a display at the Great Exhibition—among reaping machines and other technological wonders—as proof of the “Industry of all Nations.” A bookcase hosted by the British and Foreign Bible Society displayed copies of the Bible translated into 165 languages, concretizing some of the Exhibition’s imperial designs by showing how this English product was ready to infiltrate foreign markets and convert foreign minds.33

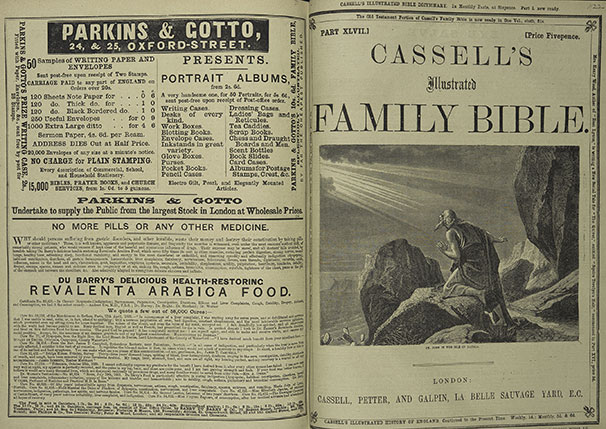

The cheapest Bibles, produced by charitable societies and intended for impoverished readers at home and abroad, usually eschewed illustrations in order to keep prices down.34 These differed from the more deluxe illustrated “Family Bibles” that occupied a central place in the middle-class Victorian home.35 Family Bibles originated in the eighteenth century, when only printers licensed by the Crown were allowed to publish the authorized (King James) versions of the Bible; to evade these legal restrictions, unlicensed printers created Bibles with notes, illustrations, and all manner of extra materials—additions that, in the nineteenth century, became almost encyclopedic, resulting in Bibles that “functioned more like religious furniture than biblical texts,” in the words of Colleen McDannell.36 Victorian illustrated family Bibles were often sold in serial parts, available on different kinds of paper and at different price points, resulting in a mass accessibility across many financial strata. Publisher John Cassell issued his Bible, as he did many of his publications, in five forms: weekly numbers, monthly parts, quarterly sections, half-yearly divisions, and annual volumes. Cheap weekly numbers or monthly parts were sold “up and down the country, from house to house, by colporteurs,” for much of the nineteenth century.37 Families could customize their Bibles in different bindings and covers; they could also use the blank family register page to record occasions such as births, marriages, and deaths (Fig. 3.1). The illustrated Bible was a religious text interwoven into the secular world, caught up with the incidents of family life, with the décor of a parlor room, with privatized acts of reading, both silent and aloud. That the Bible was sold in serial parts aligned it with novels, popular magazines and other new forms of accessible reading materials. Parts wrappers for Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible—still intact in a copy held in the British Library—are covered with advertisements, revealing how the Bible functioned within a secular commodity culture. Advertised products range from hand-books to writing paper to “Delicious, Health-Restoring Revalenta Arabica Food” (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.1 “Family Register.” The Imperial Illustrated Bible, c. 1858. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.c.7.

Fig. 3.2 Parts wrappers. Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible, c. 1859–63. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.a.2.

Innovations in Bible illustration began in the 1830s with Charles Knight’s Pictorial Bible (1836–8). Knight wanted to create a popular edition that would appeal to the same working-class audience he catered to with the illustrated Penny Magazine and the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. The Bible contained around thirty illustrations, following a pattern established in the 1790s, with prints engraved after paintings by Old Master artists like Raphael and Rubens. Knight’s innovation was to add modern illustrations, simple wood engravings, depicting the lands, customs, costumes, and plant life of the Bible.38 These additions were taken to an extreme with John Cassell’s vast mid-century illustrated Bible, discussed below, which greatly expanded the numbers and types of engravings. Unlike Knight’s Bible, Cassell’s eschewed derivative Old Master scenes in favor of original compositions created by a range of different artists, adding to a sense of his Bible’s heterogeneous contents. A final contrast is offered by the “Doré Bible,” also published by Cassell (1866) and discussed below; all of the pictured scenes are illustrated by a single artist, Gustave Doré, lending a sense of cohesion to what was to become the best-selling Bible of the later nineteenth century. It bears repeating that these “big” Bibles reflect the entrepreneurial spirit of the age, as they were all produced by businessmen rather than religious figures.

Reviewers of illustrated Bibles often took a condescending tone toward the pictorial content. A critic of Cassell’s Bible in 1861 disdains the “half-taught adult” who needs pictures to stimulate his fancy, as opposed to “the highly cultivated reader,” for whom illustrations are more a hindrance than a help.39 John Ruskin goes so far as to declare, “I do not know anything more humiliating to a man of common sense, than to open what is called an ‘Illustrated Bible’ of modern days.”40 (Always reacting to media modernity, Ruskin makes cantankerous comments about most of the artifacts studied in this book, from photographs to advertising posters; illustrated Bibles are not an exception.) Here Ruskin writes to attack the mediocre quality of the Bible’s engravings, many of which seemed crude and poorly finished. Yet despite elite commentators’ hostile notion of illustrated Bibles as bastions for the uneducated, the vehemence of their comments gives a sense of the illustrated Bible’s popularity and allure, even for educated people. The tremendous sales numbers for the Knight, Cassell, and Doré Bibles testify to just this fact.

Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible (1859– 63) was the best-selling illustrated Bible of the mid-nineteenth century.41 The presiding genius behind its production, John Cassell, had a career whose events represent in miniature some of the great media developments of his age.42 Cassell began humbly in Manchester as an itinerant Methodist preacher who marketed tea and coffee to working-class people as alternatives to alcohol. The roots of his publishing empire began when he printed his own bottle labels, soon followed by printed advertisements and a temperance journal. Expanding into newspaper publishing allowed Cassell to promote religious freedoms, working-class politics, and, not least of all, his own commodities. Targeting newly literate working-class readers, he produced popular educational hand-books on subjects such as railway etiquette and letter-writing. He agitated against the stamp, paper, and advertising taxes in the 1850s, even providing testimony on the issue to the Select Committee of the House of Commons. A turning point came with the Great Exhibition of 1851, when he created an inexpensive yet vast illustrated record of the event. The Illustrated Exhibitor, a Tribute to the World’s Industrial Jubilee, was jam-packed with woodcut engravings and heavily advertised; it came out in weekly numbers at 2d, in monthly parts at 8d, and eventually filled four volumes. The first number sold out in a day, and Cassell claimed to sell 100,000 copies by the end of the first month.43 This venture enlightened Cassell as to the commercial value of illustration, and from 1851 onward pictures played a key part in his book and newspaper publications.44 Among the highlights, he published what was likely the first illustrated edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Britain (1852), with illustrations by George Cruikshank. Cassell’s indefatigable advertising campaigns made his name into an integral part of the mid-century visual mediascape: “On hoardings, in magazine advertisements, in posters at railway bookstalls, the magic word CASSELL’S was kept ceaselessly before the reading public,” as Richard Altick reports in The Common Reader.45

Cassell published his Illustrated Family Bible from 1859 to 1863, with more than a thousand engravings. The publication cost about £100,000 to produce and sold 300,000 copies a week in penny numbers. Despite the Bible’s basis in an ancient, non-Western history, it was advertised—using language familiar from the Great Exhibition—as a technological wonder and epitome of modern progress. Cassell billed his Bible as “The Greatest Enterprise of the Age!,” an appropriate slogan for a showman with a circus-like sense of publicity.46 (Cassell’s biographer notes that he was always one to yoke “religious motive to the chariot of commerce.”)47 Advertisements touted reviews calling Cassell’s Bible a “truly national work” whose “mechanical execution” makes it “one of the marvels of this marvellous age.” The Bible’s vast number of illustrations, sold affordably, made the book into a modern feat of engineering—thereby denoting it as English, and Victorian, rather than “oriental” or ancient. The illustrations were described as key to the Bible’s proselytizing efficacy: Cassell reported success among Native Americans when he received a subscription from ten members of the Creek tribe. “[T]he missionary stated that the Indians, both heathen and Christian, were delighted with the pictures.”48 Advertisements proclaimed the Bible’s missionary qualities, noting its immense sales “in America, and throughout our Colonies … whilst Missionaries availed themselves of its graphic Illustrations to enforce the truth upon their native hearers.”49 The potency of illustrations merged together with the power of the Bible, working to conquer and Christianize the world. Advertising rhetoric ultimately presented Cassell’s Bible as a powerful, unified object, especially in its illustrations: whole, modern, and nationalist.

Yet the Bible’s reality, when one actually peruses it, is something quite different. The volume in fact demonstrates a wild heterogeneity, a disorienting mishmash of notes, commentaries, and disparate illustrations—contents advertised by Cassell as depicting

the Mountains, Valleys, and Plains, the Lakes and Rivers, the Cities, Towns, and Villages in “the lands of the Bible;” their Plants, Animals, and Minerals; the Manners, Customs, and Arts of their People; their Ruins, Monuments, Coins, Medals, Inscriptions, and other remains of Antiquity;—all accurately drawn, and faithfully engraved, expressly to elucidate the Sacred Writings.50

Imitating eighteenth- and nineteenth-century travelogues, the Bible sounds like a Victorian tourist destination, one with a distinctive set of places, peoples, customs, flora and fauna. New railways had opened up tourism to the Middle East just a few years previously, creating a new desire in readers for a more accurate representation of the Holy Lands, a kind of science of biblical illustration.

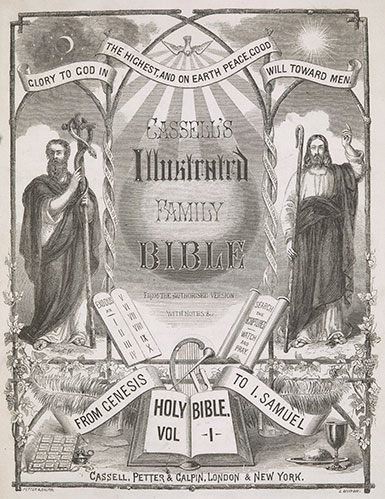

The Family Bible creates a journey to a place that is also a journey to a time. The Bible is inherently a palimpsest of history, a layering of times: even the move from the Old Testament to the New enacts this overlay, as the Old prophesies the New and the New fulfills the Old—uniting “the different portions of the Sacred History in their connection and harmony,” as the Bible’s preface declares.51 Spaces and times are a visual jumble in the Bible’s collage-like page layout, which combines text, illustrations, and commentary in different mingled spaces. Palimpsest and collage make up the Bible’s striking frontispiece (Fig. 3.3), whose doubled iconography has the Old Testament mirrored by the New: Moses on the left, Jesus on the right; ten commandments echoed by scriptures, night by day, oil lamp by bread and blood. The Bible’s dual temporalities are superimposed by that of the Victorian present day, as framing rays of light mimic the beams of a showman’s lamp or circus tent. This visual fanfare perfectly befits the opening of a crowd-pleasing nineteenth-century spectacle. Faux architectural elements in this frontispiece introduce the idea of the book-as-world, paper imitating an entryway both spiritual and sensuous.

Fig. 3.3 Frontispiece, Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible, c. 1859–63. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.a.2.

Cassell’s Bible conjoins disparate kinds of knowledge in the manner of Michel Foucault’s heterotopia, an “effect of the proximity of extremes, or … the sudden vicinity of things that have no relation to each other; the mere act of enumeration that heaps them all together has a power of enchantment all its own.”52 Foucault designates the museum and the library as quintessential nineteenth-century heterotopias of time, existing as places both within and beyond history, collecting unto themselves diverse histories, objects from many cultures and styles (182). Heterotopias are distinguished by their boundedness, their portals of opening and closure, their mixture of not merely diverse elements but diverse ways of knowing, juxtaposing incompatible parts and discontinuous temporalities. A ship, a cemetery, a Victorian boy’s school, a garden: these self-contained communities or institutions are profoundly symbolic, standing for “the world” at large. “The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and the whole world at the same time” (182). Even while heterotopias contribute to culture in normative ways and uphold modern societies, they also offer utopian alternative realities, creating “a different real space as perfect, as meticulous, as well-arranged as ours is disorganized, badly arranged, and muddled” (184). Foucault’s heterotopia is a gorgeous discombobulation that perfectly describes some of the nineteenth century’s ambitious projects of visual eclecticism.53 The Great Exhibition itself is a supreme example of a Victorian heterotopia, a hodgepodge presented under the guise of a beautiful order. If the nineteenth century is famous for its projects of classification and discipline—as Foucault himself has shown—the era also produced visual projects that were wildly incongruous and multifaceted, pushing at the boundaries of order itself.

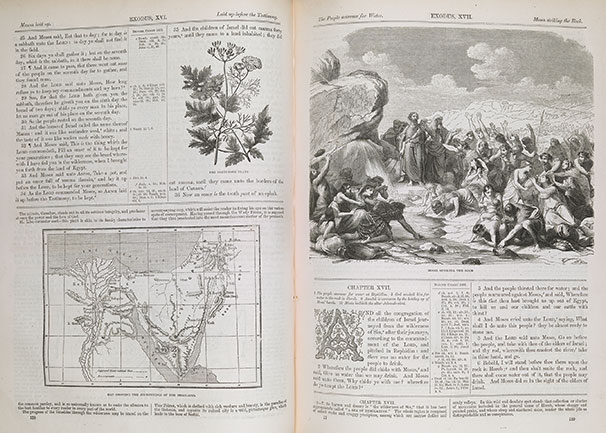

Cassell’s Bible is a visual, spatial heterotopia, as well as a temporal one. A page spread devoted to the Israelites wandering in the desert (Fig. 3.4) offers a fantasia on the theme of wandering, described across diverse modes of knowledge. A map shows “the Journeyings of the Israelites during the Forty-Years’ Sojourn in the Wilderness”; it is styled with the familiar objectivity and precision of Victorian topography. Small print beneath the map describes the region as a travel destination, “the paradise of the Bedouin, … a wild, picturesque glen” (1:128), using canned phrases from travelogue prose. Another box offers an illustration of “The Coriander Plant,” whose seed Cassell’s text compares to Manna; the plant is shown in standard natural-history format, clearly delineating flowers and leaves. An opposing illustration depicts the dramatic narrative of “Moses Striking the Rock,” in which the patriarch bestows water upon a thirsty and beseeching people in the midst of a rocky desert. The jumble of bodies, naked arms thrown up in attitudes of supplication and relief, conveys a drama of hunger and physical satiation that strikingly contrasts the measured, scientific illustrations on the opposing page. Tiny script at the page’s bottom offers the symbolic interpretation of the scene, by which “the wilderness of Sin,” a veritable “SEA OF DESOLATION,” is superimposed upon the actual Holy Land geography of mountainous “Horeb,” “a wild and desolate spot” (1:129). The visual collage of the page stitches together topography, travelogue, biblical text, natural history, dramatic pictorial narrative, and explicative commentary, all united under the allegorical poetics of a desperate journey. The spatial collage is matched by a suturing of temporal disjunctions, by which forty years of wandering becomes a single, coherent, seamless passage of time, coterminous with the contemporary moment of Victorian map-making and natural history.

Fig. 3.4 Exodus XVII (“Moses Striking the Rock.”) Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible, c. 1859–63. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.a.2.

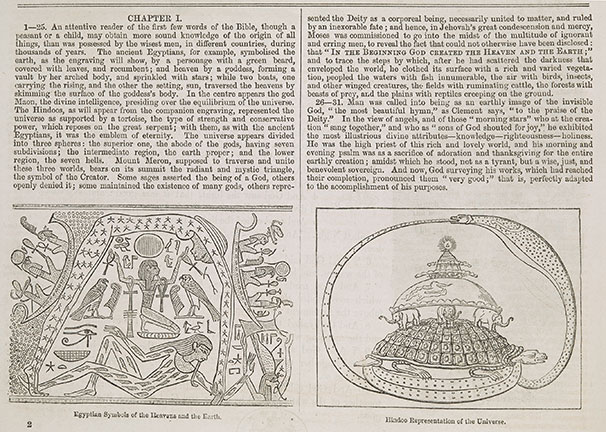

Cassell’s Bible contains a heterotopian array of knowledges, many of them extending beyond the Christian tradition. Accompanying the Genesis story, illustrations depict Egyptian symbols of heaven and earth and a Hindu picture of the universe, featuring a giant turtle (1:2) (Fig. 3.5). The commentaries offer a similar expansive miscellany, invoking modern science: on the rainbow appearing after the Flood, a note informs that “the rainbow is produced by the refraction of the sun’s rays falling on drops of rain.” The same note also observes that Homer and Virgil saw the rainbow as a “divine token or portent” (1:16). The practice of comparative mythology—Egyptian, Hindu, pagan, and Christian—would seem to deconstruct the foundations of Christian faith, implying the nullification of all faiths. The use of modern science to explain biblical phenomena seems similarly problematic. Instead, though, Cassell’s Bible offers a utopian belief in the mixture itself, a confident sense that attacking the project of faith on many fronts amplifies, rather than dismantles, the different ways of knowing, seeing, and believing.

Fig. 3.5 Genesis, with illustrations of “Egyptian Symbols of the Heavens and the Earth,” and “Hindoo Representation of the Universe.” Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible, 1859–63. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.a.2.

A Bible inherently encodes a utopian sense of history, with its scenes of paradise and promised lands, its offer of salvation, its visions of resurrection and redemption. (These promises have their negative echo in the temptations, sins, falls, plagues, judgments, and other, darker temporal shifts.) The heterotopia of Cassell’s Bible provides an ebullient vision by which Christian faith, ethnographic knowledge of other faiths, and scientific progress can coexist on the same pages and in the same visual realms. The politics of this Bible accord with those of the heterotopias outlined by Foucault, as it invokes a range of contradictory authorities, from patriarchs to prophets, from poets to modern scientists and geographers, each potentially undermining the other, yet together emerging as strongly authoritative. Cassell’s Bible is ultimately a deeply normative object, strengthening the Victorian Protestant project even while it juxtaposes modes of knowing that threaten to annihilate one another.

This analysis presents a surprising take on the nineteenth century’s famous historicism, whose rational and empiricist drives would seem to oppose qualities of the spiritual, metaphysical, and mythical. Victorian religious historicism has typically been understood through the Higher Criticism, which read the Bible as a historical document and looked to Jesus as a political leader rather than a holy figure. In Cassell’s Bible, however, history works not so much to deconstruct as to create, building the reality of the biblical world for modern readers. Illustrations serve as scientific proof, and also work toward reanimation, revivification, bringing the past alive into the present. These performances help the reader, as one American Bible advertiser puts it, to “separate himself from his ordinary associations” and return to the ancient world of the Bible “by a kind of mental transmigration.” Indeed, the Bible reader’s task is to

set himself down in the midst of oriental scenery.… In a word, he must surround himself with, and transfuse himself into, all the forms, habitudes, and usages of oriental life. In this way only can he catch the sources of their imagery, or enter into full communion with the genius of the sacred penmen.54

Even while Bible illustrations performed immersive acts of solidification and concretization, these historical renderings all went toward fabricating an illusion. Illustration thus emerged in a contradictory sense as an anti-real real, a reasoning into emotion, an authentic simulacrum. The Bible advertisement implies that illustrations create the possibility of time travel and even racial transformation, as the reader becomes “oriental” in his communion with the Bible’s authors. I want to delve now into some of the unexpected possibilities offered to the Western Bible reader by these strange transmigrations.

Heterotopias of Time: Archaeology, the Fragment, the Nation-State

“A truly national work”: so one reviewer hailed Cassell’s Bible, praising the way that its low cost enabled a broad, nation-wide distribution.55 Yet the resonant phrase also evoked the Bible’s function as a shining object of British patrimony, proof of national cohesion and British cultural superiority. Illustrations played a key part in making the Bible British, telescoping the modern West onto the ancient East. A British ethnographic eye reimagined the customs of ancient peoples using modern exemplary subjects such as Egyptians and Jews. The illustrated Bible created a real world that was also illusory, melding together times and spaces into a single, unified—and fantastical, or miraculous—world. A whole ethnography of the Bible moved seamlessly from present to past and back again via the illusion of illustration.

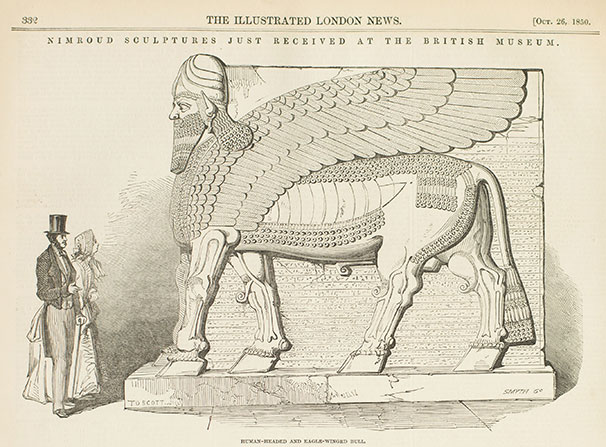

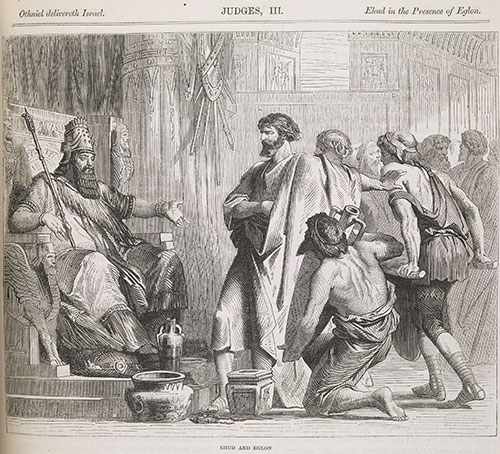

The world picture created by nineteenth-century Bible illustrations reflected dramatic developments in British archaeology. Scholars have focused on the impact of Austen Henry Layard’s stunning Assyrian discoveries in the 1850s. Layard’s excavation of the ruins at Nineveh, in modern-day Iraq, gained a huge following back in Britain, especially after he audaciously secured the Assyrian pieces for the British Museum. Layard narrated his exploits in travelogues described by one scholar as “the archaeological best-sellers of the Victorian age,” and the arrival of the Assyrian sculptures at the British Museum was widely covered in the popular press (Fig. 3.6).56 Despite the fact that biblical events took place in ancient Egypt and Persia, Bible illustrators enthusiastically adopted Assyrian patterns as the ahistorical and inaccurate backgrounds for various dramatic scenes.57 Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible portrays numerous Old Testament scenes with the distinctive Assyrian human-headed bull holding up a wall or ornament. In “Ehud and Eglon,” the tyrannical Moabite king Eglon is portrayed with a beard mimicking that of an Assyrian sculpture; his throne is decorated with a winged bull (Fig. 3.7). Steven Holloway argues that Bible illustrators turned to the Assyrian objects because Layard’s acquisitions inspired a “popular nationalistic identification with ‘ancient Assyria’”—a claim worth pausing over for its sheer incongruity.58 The Bible itself was one crucial adhesive force joining together these two very different times and places.

Fig. 3.6 “Nimroud Sculptures Just Received at the British Museum.” Illustrated London News, October 26, 1850.

Fig. 3.7 “Ehud and Eglon.” Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible, c. 1859–63. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.a.2.

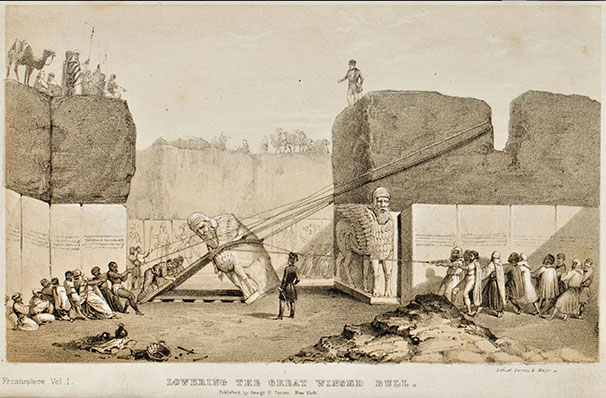

Many Victorian writers, Layard included, celebrated his discoveries for offering proof of the Bible’s veracity. The Mayor of London, awarding the archaeologist the “Freedom of the City of London” in 1854, praised him for securing “the long lost Remains of Eastern Antiquity … in so perfect a state as to demonstrate the Accuracy of Sacred History.”59 Layard similarly marveled in his acceptance speech that his finds could serve as “records” that “confirm, almost word for word, the very text of Scripture.”60 Layard’s words are not quite true, as the Assyrian discoveries provided ammunition to both conservatives and rationalists in their fight over the literal truth of the Bible.61 Yet for Layard, as for many Victorian commentators, “Sacred History” became the glue linking “Eastern Antiquity” to modern Protestant Britain. Décor and architecture played a decisive role in Bible illustrations because the oriental designs, mimicking artifacts displayed in the British Museum, affirmed a smooth timeline of development from past to present, creating a narrative of a single Christianity, ancient to modern. Layard himself was a key mediating figure in this process: the intrepid archaeologist beat out imperial rivals like France and Turkey to bring home foreign treasures for triumphant display (Fig. 3.8). These objects lost their foreignness once safely installed in the British Museum, entering into a new constellation—a heterotopia of time that was outside of times yet also deeply embedded in time. Biblical history, moving from wandering to salvation, was superimposed upon British national history, as epitomized by the British conquest of the material world evident in the British Museum. These two superimposed histories, meanwhile, ignored the reality of Assyrian history as a unique and separate entity. In the scriptural reception of Assyrian relics, ancient “Christian” history was fused with modern British museum-making, creating an imaginary timeline of origins of the type that Benedict Anderson aligns with the rise of modern nation-building.

Fig. 3.8 Austen Henry Layard, Frontispiece. Nineveh and Its Remains. Vol. 1, 1849. Courtesy Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives.

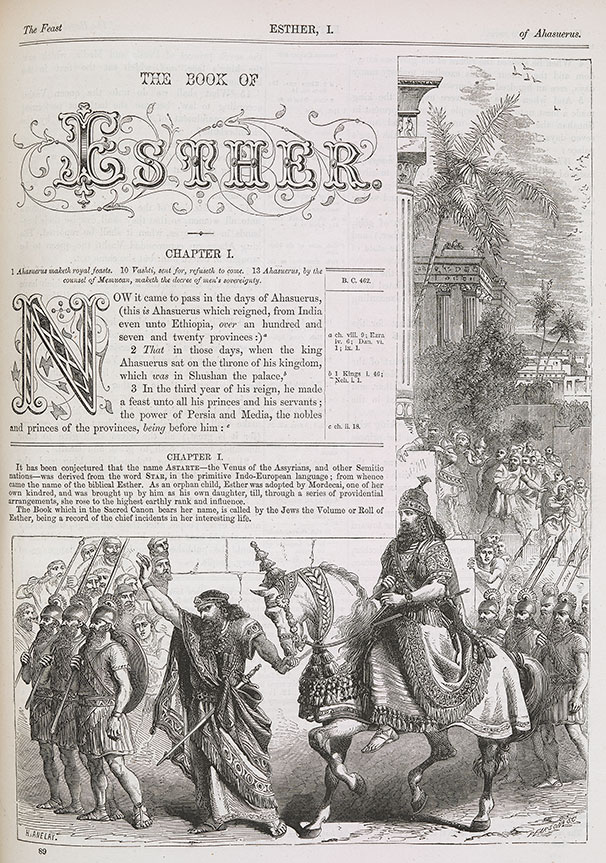

The Assyrian imagery in Cassell’s Bible itself, meanwhile, courts ambiguity in its very ubiquity. On the one hand, it often adorns settings for the tyrannical enemies of the Jews—as when the Moabite King Eglon sits upon a winged-bull throne, his patriarchal beard marbled in the distinctive Assyrian style (Fig. 3.7). King Eglon’s hard, sculptural qualities serve as a symbolic shorthand for the cruel tendencies ascribed to oppressive, non-Jewish leaders in the Old Testament. The decadent, ornamented Assyrian patterns spoke perfectly to Victorian assumptions about the enemies of Judeo-Christianity, both past and present. Yet Assyrian patterns also appeared in scenes featuring Jewish protagonists, as when Mordecai, the hero of the Book of Esther, is portrayed wearing the Assyrian royal regalia, riding a horse similarly adorned (Fig. 3.9).62 The orientalized, exotic excess of Assyrian ornament connoted Jewishness as part of a broader, and vaguer, ancient “East.” Given that these scenes feature the heroes of the Old Testament, the link between Assyria and the foreign is necessarily complicated—an idea captured by Holloway when he observes that Victorian Britain appropriated ancient Assyria for nationalistic purposes. I will return below to the vexed question of Jews and biblical otherness, but for now it is enough to point out that Assyrian patterns did not safely demarcate a divide between the believers and infidels of biblical history.

Fig. 3.9 Mordecai in Assyrian-Styled Robes. “The Book of Esther.” Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible, c. 1859–63. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board. L.15.a.2.

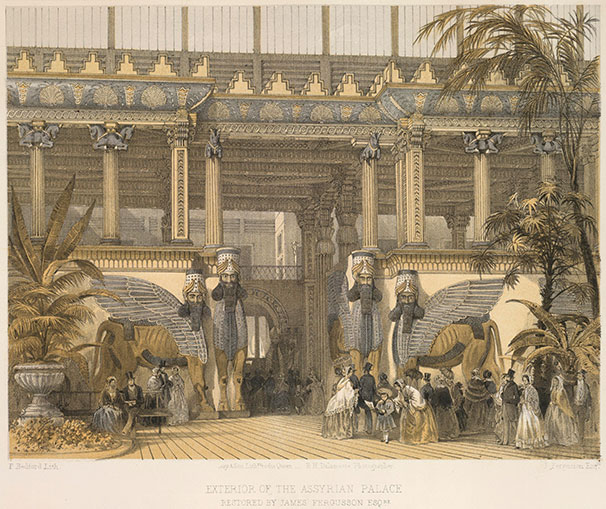

Ancient sculptural pieces influenced mid-Victorian Bible illustrations, connoting an aesthetic of the fragment. The visual fragment is a fitting echo to the biblical text, which is itself also an assemblage of alien, disjointed parts sutured into a post-historical whole. Yet scattered ancient fragments, verbal and visual, did not inspire Bible illustrators to ponder the ends of empires, like melancholy Romantic poets. Instead, Victorian scholars and illustrators reassembled the ancient fragments into new imaginative wholes, creating chimeras of fake coherence by fusing together disparate parts. Illustrators used sculptural pieces to reimagine entire rooms, halls, and palaces; their aesthetic owes much to the popular large-scale reconstructions of ancient cultures on view in the British Museum and in the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, opened in 1854. Frederick N. Bohrer writes of how Assyrian mania in mid-century Britain inspired not only winged-bull jewelry for men and women but also a “Nineveh Court” at Sydenham’s Crystal Palace (Fig. 3.10).63 The post-Exhibition Palace, sometimes seen as a precursor to the modern amusement park, offered a pastiche of history in a series of three-dimensional, walk-through galleries, reconstructing—from appropriated fragments and replicas—the architecture and ornament of ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, Byzantium, and Assyria, among others. The two-dimensional spaces of the illustrated Bible are contiguous with the ancient rooms assembled at Sydenham’s pleasure-grounds. These simulations of history might connote postmodern pastiche, but they are offered without irony as both pleasurable and educational, the classic mixture defining Victorian infotainment. The pleasures of “history,” conceived of as a grouping of commodities and costumes set amid exotic, imaginative spaces, aligns the world-building projects of the illustrated Bible with more modern phantasmagorias: like modern-day Las Vegas, offering miniaturized replicas of Paris and Venice, the Bible and the amusement park limn the world as a picture, a series of historical styles ripe for appropriation in commodified space and time.

Fig. 3.10 “Exterior of the Assyrian Palace.” Lithograph. Matthew Digby Wyatt, Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham, 1854. Courtesy University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center.

Assyrian patterns were only the most popular of a number of exotic, “oriental” visual styles in Bible illustrations—a mishmash of décor that also included Turkish, Ottoman, and Egyptian designs. These visual appropriations would seem to operate in the classic orientalist mode described by Edward Said, creating a “closed field, a theatrical stage affixed to Europe,” populated by “monsters, devils, heroes; terrors, pleasures, desires.”64 Though the orientalist biblical visual style might seem overwrought, fanciful, and slightly ridiculous to our eyes, this style was in fact received by Victorian critics as realistic. They perceived the archaeological as real because it was researched, historical, and scientific.65 (By contrast, as I discuss below, critics assailed John Everett Millais for setting his Bible parables in modern-day Scotland, even though to our eyes these images seem more “real” and everyday.) While Said posited orientalism as a series of fantasies whose ultimate purpose was to divide Western and Eastern peoples—while enabling Western empires to conquer Eastern territories—that political account does not quite capture the complexity of Bible illustrations, which appropriated “oriental” imagery for British nationalism and Protestant Christianity. The art critic W. M. Rossetti captures the knottiness of the issue when he asks, “Is our Madonna to be a Jewess, our biblical costume oriental, our scenery that of the Holy Land?”66 Rossetti’s emphasis on the word “our” aptly captures the dilemma of Bible illustrators, who had to domesticate an alien imagery for an audience demanding an authenticity of both history and faith.

In The Holy Land in English Culture, Eitan Bar-Yosef argues that Edward Said’s account of orientalism is inadequate to describe the complex attitudes of Victorian British people toward Palestine. In fact, says Bar-Yosef, “due to its geographical location, historical heritage, and, most significantly, its scriptural aura, Palestine—the Holy Land, the land of the Bible—offers an exceptionally forceful challenge to the binary logic which Said traces in Orientalism.”67 For Said, Western imperial projects in the East were always accompanied by an omnivorous scholarly and literary culture scripting Eastern otherness.68 Yet Bar-Yosef points out some of the ways that Orientalism fails to encompass Victorian encounters with Palestine. Said’s insistently secularist bent ignores the ways that devout Christian authors identified with Jerusalem rather than making it other; and Said’s resolute focus on high culture and top-down modes of authority does not acknowledge more mass-cultural forms and more diffuse models of power. While Bar-Yosef’s study does not specifically examine Victorian illustrated Bibles, his notion of a “vernacular Orientalism” seems useful for describing the ambivalences surrounding mass-cultural Christian encounters with an Eastern, yet spiritualized, Palestine.69

Bar-Yosef ultimately aligns his study with those who “point to the vulnerability, rather than the authority, of the imperial ethos.” He cites scholars like Jonathan Rose and Bernard Porter, who argue that working-class and middle-class British people were surprisingly ignorant of Britain’s actual imperial projects and possessions.70 And he argues convincingly that the nineteenth-century scholars and writers exploring Palestine largely did so not to aid in capturing the territory, but rather to strengthen their own internal Protestant commitments—to define their own Englishness, in other words, rather than to dominate a foreign other.71 While I agree with Bar-Yosef that the metaphorical Holy Land in English culture was more predominant than the actual, geographical place—and while I also adopt his critique of Said’s Orientalism for its rigid oppositions—I think he misses how the “Orientalization of self,” with all its confusions of binaries and unexpected alignments of self with other, might also have accommodated a strong imperial mandate, one turning Christianity outwards toward a generalized global mission.72 Just as Cassell’s Bible united seemingly contradictory bodies of knowledge to emerge with a triumphant and confident Christian vision, so too—as I now want to explore—the equivocal orients of Britishness could serve to legitimate an idea of the heroic Christian soldier abroad.

Sublime Sword: The Bible as Liberal Epic

The most popular illustrated Bible of the later nineteenth century was that of Gustave Doré, the prolific and tremendously influential French illustrator.73 Doré’s lavish Bible, originally published in Paris in 1865, was brought out by John Cassell in a costly 1866 English edition featuring 228 plates. It was sold in parts for 4 shillings each and in a complete volume from £8 to £15, depending on the paper quality and binding type.74 Doré’s Bible is not a heterotopia in quite the way that Cassell’s Illustrated Family Bible was—it contains none of the eclectic mishmash of scientific notes and commentary. Instead, Doré’s images were marketed as a fine art “gallery,” unified by their production by a single artist. Doré augmented his fine-art status in England by displaying paintings on religious themes at Cassell’s London premises, which led to the 1868 creation of the Doré Gallery in Bond Street. Yet Doré’s images were also popularized by widespread print circulation and book publication in cheaper, “gallery” editions.75 The Doré Gallery became a popular London tourist destination and only closed in 1914.76 That Doré’s publisher in England was John Cassell is entirely appropriate, given Cassell’s reputation as the consummate showman and master of religious art-as-entertainment. In fact, Cassell published many of Doré’s illustrated literary works, including those by Dante, Milton, and Tennyson. (We might note, too, how Dante and Milton were important intermediaries in the Victorian commodification of religious imagery, since their works transformed Christian material into quasi-secularized artistic narratives, paving the way for adaptation into forms of popular entertainment, especially in illustrations.) While Doré’s fine-art Bible seems a far cry from Cassell’s mid-century scientific and heterotopic miscellany, I want to explore now how it performs similar cultural work, telescoping and assimilating a fragmented, foreign Judeo-Christian history into a visually coherent, though slightly different, Victorian world picture.77

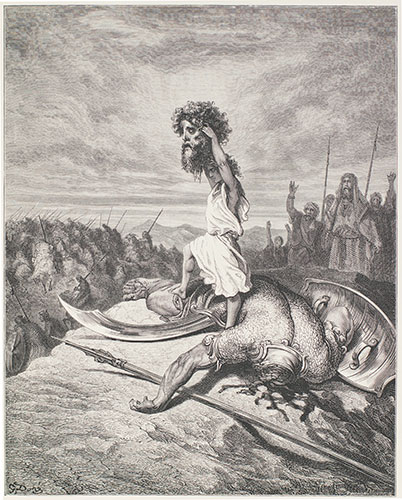

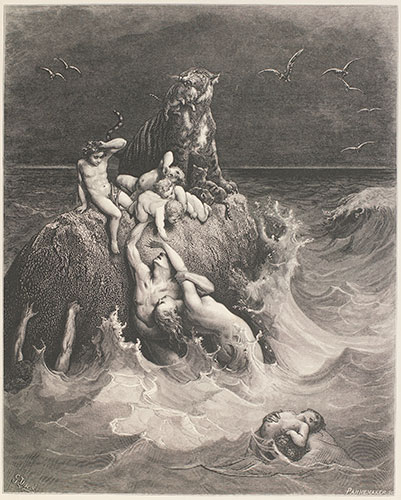

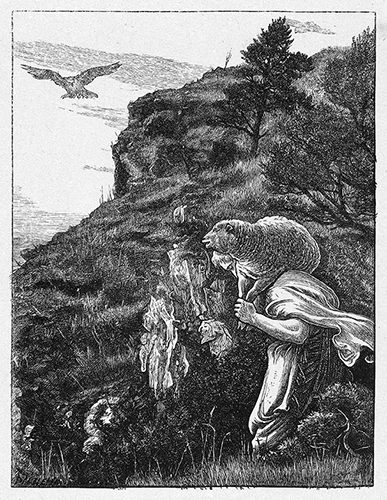

Doré’s illustrations appear to adhere to a familiar orientalist conception, as his Bible dwells upon Christianity’s most sensuous and violent episodes. Critics noted his fondness for decapitated heads; also featured were scenes of enslavement, murder, and naked drownings (Figs. 3.11 and 3.12). Doré devoted a large number of scenes to the Passion of Christ, lingering on the drama of a nude male body mangled and put on display in a gruesome chiaroscuro spectacle. The Bible’s alien otherness, its “oriental” settings and exotic peoples, offered an excuse to depict all the physical, corporeal taboos forbidden to contemporary Victorian viewers. No doubt Doré’s French Catholicism shaped his enthusiasm for the body, blood, and flesh of biblical characters. Interestingly, his illustrations found a much more eager audience in Protestant Britain and America than in France—perhaps due to the way that his images packaged adventurous content in respectable, Christian form.78 Catholic-inflected, corporealized illustrations gained a Protestant aspect when they appeared in the form of a Bible, a book mediating the individual’s (or family’s) direct relation to God. Moreover, Doré decorated these scenes with architectural elements borrowed from across the “oriental” spectrum, using books he found in the Louvre, and enhancing his Bible’s foreign, exotic atmosphere. Doré’s Bible united the otherness of the Catholic with that of the Orient, offering middle-class British readers scenes that courted both desire and transgression.

Fig. 3.11 Gustave Doré, “David Slays Goliath.” The Holy Bible, 1866.

Fig. 3.12 Gustave Doré, “The Deluge.” The Holy Bible, 1866.

Yet the Bible’s markers of difference, both Catholic and Eastern, appeared alongside more confusing interminglings of self and other. Many of the figures are neoclassical or Westernized, rather than Semitic or racialized—invoking a long tradition in Western art history, from the Renaissance onward, of portraying Bible figures as muscular Caucasians. Doré’s illustrations also contributed to a surprisingly British visual tradition in their inheritance from John Martin, the Romantic painter of sublime and apocalyptic scenes. Martin’s paintings circulated widely in print form across Europe, and British critics regularly described Doré as Martin’s inheritor, despite Doré’s French birth.79 In paintings such as The Deluge (1834) and The Great Day of His Wrath (1853) (Fig. 3.13), Martin had created massive canvases where the acts of God and Nature rained down rocks, lava, storm, and destruction, dwarfing any human features and figures. Similarly, as The Eclectic Review noted in 1867, Doré’s interest lay in “the huge magnificences of nature—whether size, and dimension, or mystery—or the overwhelming conflict of the elements.”80 Both Martin and Doré portrayed small human actors overwhelmed by the forces of God, nature, or enemy armies. Some art historians have seen Martin’s Bible paintings as implicit responses to Britain’s emergent industrialism, in terms suggestive for our understanding of Doré: Martin’s paintings portray large-scale social transformations inflicting massive change upon a landscape and a people.81 Modernity itself might be imagined as the rush of oncoming forces, encompassing social upheavals, industrial and scientific innovations, mobs, overthrows.82 Both Martin and Doré depict a recognizably British aesthetic of the apocalyptic, biblical sublime, as they look back to ancient biblical history while also channeling very modern transformations.

Fig. 3.13 John Martin (1789–1854), The Great Day of His Wrath. Oil on canvas, 1851–3. © Tate, London 2019.

Doré’s Bible illustrations combined ancient and modern elements with the wild incongruity typical of Victorian historicism. On the one hand, critics called his style medieval and grotesque, comparable to the monstrous carvings of medieval cathedrals.83 Yet Doré also embraced modern techniques of mechanical reproduction: Lorraine Janzen Kooistra notes that he employed a veritable “army of engravers” who used “mechanized grids” to mass-produce illustrated books at a rate worthy of a Victorian factory.84 These production methods mirrored Doré’s innovative visual style of “tonal facsimile,” which emphasized tones over lines to create graduated shades of black and white.85 Scholars have taken this new style to intimate the shift away from hand-drawn, linear engravings—like those of Cassell’s earlier Bible—toward late-century, mechanized methods that were more “tonal, photographic, and mimetic.”86 Doré’s combination of the biblical and the Victorian, the medieval and the modern, the illusionistic and the sublime, perfectly captures the paradoxical nature of Victorian new media, building on earlier or more archaic forms to make its advances.

Doré’s grotesque style and brutal subject-matter sits somewhat uneasily with the Bible’s central place in the Victorian veneration of the family. Religious historian Frances Knight observes that, for all of the Bible’s family-friendly connotations, in fact the most popular stories for illustrations across the nineteenth century were also the most violent—“Cain and Abel, the Flood, Abraham and Isaac; the Massacre of the Innocents, the Woman taken in Adultery, the Crucifixion.”87 These scenes starkly contrast the family register page at the Bible’s front, usually depicting vignettes of family life—marriage, death, and a happy couple ascending to heaven. While the family aspects of Victorian Bibles seemed to cater to their often female purchasers, in fact the dominant keynote of Bible illustrations moved in the opposite direction, toward epic themes of male-oriented nation-building and bloodshed, featuring prophets, heroes, kings, soldiers, and martyrs.88 Doré’s illustrations, in particular, accentuate the Bible’s masculinist, epic themes. From the Old Testament, he features a patriarchal god presiding over male contests for power or revenge; from the New Testament, he emphasizes forms of suffering, often gory ones, dramatizing embodiment and apocalypse via extremes of dark and light.

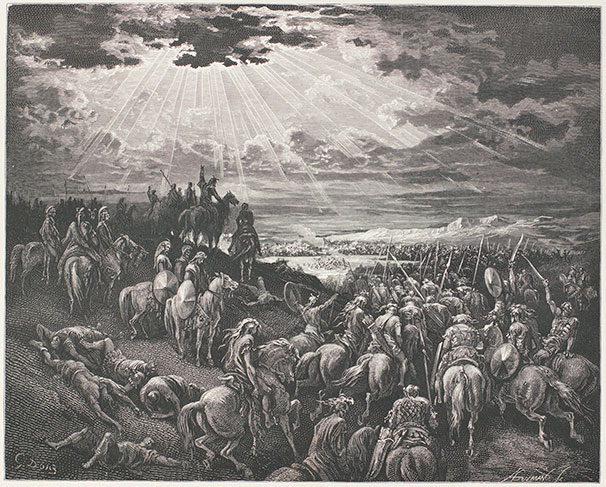

The biblical epic visual tradition, traced from John Martin’s paintings to Doré’s book illustrations, recasts the Bible in the form of what Edward Adams has called a liberal epic.89 Adams defines his term via secular sources—mostly late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century war historians like Gibbon and Macaulay—but his notion of liberal epic seems particularly apt to describe Doré’s wartorn Bible illustrations. “Liberal epic” limns a post-Enlightenment intellectual tradition that excoriates violence even while celebrating the individualistic male heroes who conquer in the name of liberty. In the Bible’s Old Testament, these scenes depict Jewish tribes escaping Egyptian slavery and seeking a homeland, often while fighting the large forces of enemy kings. In the New Testament, scenes celebrate the defiance of Christian heroes overthrowing the tyranny of a pagan Roman empire. The visual trope of these epic battles spotlights a lone figure on a hilltop or mountainside, calling down God’s wrath upon a vast multitude of faceless enemies. Doré’s illustration of “The Egyptians Drowned in the Red Sea” centers on the distant figure of Moses, elevated above the fray with arms upstretched and haloed in light, while in the foreground crashing waves envelop the masses of Pharaoh’s army. In “Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still” (Fig. 3.14), Joshua reigns as the image’s highest figure, one arm raised, bathed in streaks of holy light, while the chaos of battle rages among myriad figures below him. The composition of biblical epic foregrounds a heroic figure set against an invading mob, merging the natural sublime into a kind of political sublime, as rushing waters are replaced by rushing bodies. The visual layout of these scenes uses the Bible to reflect a deep Victorian political ideology, showing how, despite liberalism’s moves towards pacifism, humanism, and civilizing diplomacy, the era also celebrated the heroic, self-determining individual through scenes of thrilling violent triumph, legitimated through a larger ethical system predicated on the disavowal of war and violence. (It’s worth noting that these values differ from those of the Bible itself, especially the Old Testament, where warfare appears as a fitting method for asserting religious righteousness.)

Fig. 3.14 Gustave Doré, “Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still.” The Holy Bible, 1866.

Doré’s Bible is an especially potent vehicle for liberal epic because of its book-sized scale, bringing vast martial scenes into the intimate sphere of the Victorian drawing room. His illustrations shift between bodily close-ups and distant panning landscape shots, telescoping between near and far, in the same way that the illustrated book itself oscillates between miniaturization and vast expansion. These shifts in scale can be seen to allegorize a political relationship between the one and the many: Adams cites Lyotard in describing liberalism’s alignment between individuals and nations, by which “humanity [is] the hero of liberty” and “the State receives its legitimacy not from itself but from the people.”90 Doré’s hero, perched aloft on the mountaintop, represents self-determination at both the individual and national levels. Even Doré’s familiar signature chiaroscuro might be read politically, as the extremes of light and shadow render the drama of the one versus the many, with darkness and shadows implying untold numbers of enemies, signifying the obscure multitudes of a political sublime.

Scenes of biblical epic describe acts of violent nation-building that are also critiques of imperial tyranny, as they celebrate pious rebels who throw off the yokes of larger, oppressive imperial forces. That these scenes were rousing for a British audience might seem a strange reversal, given that Britain itself was a major imperial superpower in the nineteenth century. Yet the odd identification can be explained via the tortuous logics of empire: Britons did not envision their own imperial project as one of forceful domination so much as the result of a few men’s heroic efforts, where hordes of unbelievers were brought to heel by a small number of British men with “character.” Appropriately enough, Doré’s Bible itself became a visual template in the later nineteenth century for framing stories of British imperial heroes and martyrs. As Sue Zemka has written, after General Gordon died in his 1885 attempt to retake the Sudanese city of Khartoum from Islamic rebels, he achieved Christian deification in the English press; his arrival at Khartoum appeared in the Pictorial Records of the English in Egypt (1885) in the iconographic format of Doré’s “Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem,” with the noble Gordon riding his horse toward certain doom while surrounded by restive Khartoum natives.91

The telos of liberal epic, for Edward Adams, is the modern first-person shooter video game, in which “[t]he player becomes the hero-killer, generally in a war to save humanity from some grandiose threat of conquest.”92 When Adams jumps from nineteenth-century verbal sources to the twenty-first-century video game, he elides the Victorian visual modes that also contributed to the trajectory he outlines. Ever-greater illusionistic depictions of graphic violence escalated into the twentieth century, until war itself became an “unreal simulacrum.”93 Doré’s Bible illustrations stage a crucial moment in this trajectory, combining visual mimeticism with a spiritual subject-matter that remains resolutely anti-realist—embracing the sublime, the supernatural, the apocalyptic, and the grotesque.

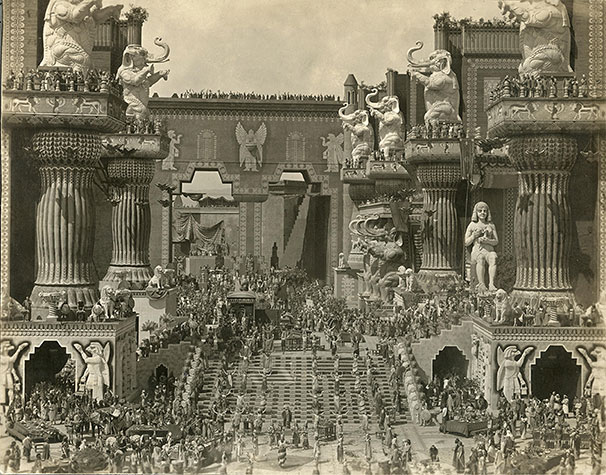

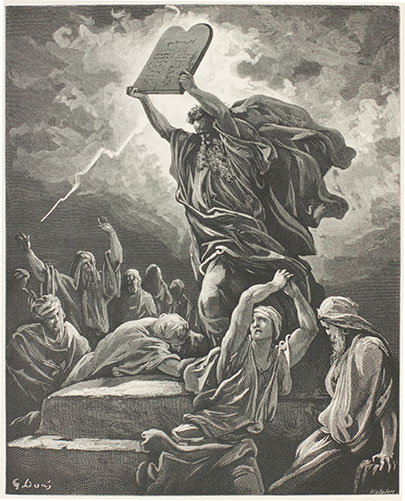

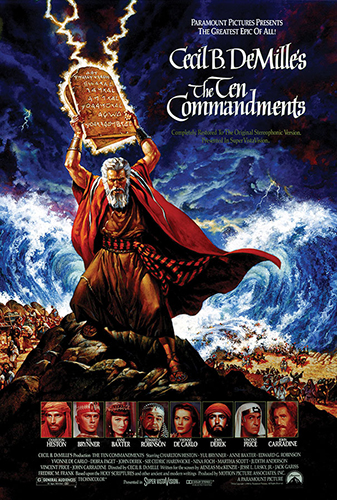

These elements help to explain Doré’s influence on early cinema, and even on modern Hollywood. Scholars have traced a direct line from Doré’s Bible to the epic biblical films of D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, especially DeMille’s Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956 versions).94 Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) famously envisions Babylon as an opulent, ornamented, and orientalized setting inspired by Doré’s elaborate pages (Fig. 3.15). The movie poster advertising Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956) models itself directly on Doré’s image of “Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law”—once again portraying the righteous patriarch atop a mountain, raining down retribution on an undeserving people (Figs. 3.16 and 3.17). Doré’s searing chiaroscuro translates well into the film poster, as a bolt of lightning visually anoints Moses as the direct representative of God.

Fig. 3.15 Film still of Babylon from Intolerance (1916) dir. D. W. Griffith. History and Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo.

Fig. 3.16 Gustave Dore, “Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law.” The Holy Bible, 1866.

Fig. 3.17 Movie poster, The Ten Commandments (1956), dir. Cecil B. DeMille. Everett Collection, Inc./Alamy Stock Photo.