2

Realism

Realism’s War Pictures: Reality Effects in the Illustrated Newspaper

Crimea: Modern War, Media War

The Illustrated London News, founded in 1842, was the first pictorial newspaper in the world.1 New wood-engraving technology allowed picture and letterpress to be printed on the same page, resulting in a major transformation in the way that the news was visually conveyed. Illustrated newspapers were disposable paper items that came and went with each renewed news cycle, and would therefore seem to court obsolescence and oblivion. In this chapter, however, I look to the Victorian illustrated newspaper as a crucial and influential visual paradigm for rendering the reality of “the world” as readers understood it—a paradigm that hovered uneasily between art and fact in an era before mass photojournalism. In particular, the illustrated newspaper served as a crucial site for the development of realism as an aesthetic practice. While most studies of nineteenth-century realism have focused on novels, paintings, or photographs, realism was in fact a multimedia style formed across a range of visual and verbal genres. Nineteenth-century audiences would have experienced realism within a vastly expanded cultural field, especially in the era’s new visual media—not just in photographs, but also in engravings, lithographs, and illustrated newspapers, not to mention the more large-scale illusionism practiced by panoramas and world exhibitions.

The chapter studies realism as a series of modes operating at the nexus of theory and history. While these modes recur across history in Western representational artifacts, they took distinct forms in the nineteenth century, influenced by the particulars of new technologies, newly invented media, and new norms of objectivity. They also emerged, as Franco Moretti and George Levine have argued, out of the great social transformations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with the ascendance of the middle classes and the relative decline of aristocratic power.2 They appeared in both verbal and visual arts. And they emerged in mid-century visual journalism in response to a specific historical crisis—the Crimean War (1853–6)—whose traumas necessitated new representational techniques. I designate these realist modes as the descriptive, the authentic, the everyday, and the plausible. Consolidating ideas from previous scholars, I track how each mode is interrelated and yet at times contradictory: these modes sometimes overlap or occur simultaneously, suggesting that they are not completely distinct. The descriptive mode produces a close, indexical account of details and surfaces, often a rigorous mapping of a scene or landscape. The authentic mode testifies to the sincere truth of an eyewitness, usually foregrounding the felt experiences of an on-the-spot reporter. The everyday mode focuses upon mundane, routine temporalities, featuring ordinary kinds of characters, especially those belonging to the working class. And the plausible mode affirms what an audience already expects of the real, basing its sense of reasonableness in known types and conventions.3

The chapter studies these effects, first, in the visual journalism reporting on the Crimean War, dubbed by scholars the first “media war” for its unprecedented newspaper coverage. Artists and reporters invented a new visual vocabulary to convey the war’s dark realities, especially in the unwarranted suffering of working-class soldiers doomed by an incompetent British leadership. The chapter then tracks these reality effects into George Eliot’s novel Adam Bede (1859), published just a few years after the war, and famous for its manifesto demanding a turn toward realist subjects, characters, and practices. While Eliot’s high-flown pastoral novel might seem distant from newspaper accounts of Crimean battlefields, the book in fact retells the newspaper narrative of the war in miniature, using the same realist techniques as those found in the new visual journalism. It is no coincidence that the decade witnessing Britain’s first dedicated war reportage also saw the first use of “realism” as a term of literary criticism: the mid-century realist aesthetic emerged from transforming representational norms across media and genres.4

The Crimean War was a global conflict whose unfolding provoked new representational modes and possibilities. A war will always be a test case for realism: it pushes artists, writers, and reporters to the extreme limits of representation, compelling us to think about what is allowed to be shown, and what it is possible to show. The Crimean conflict has been called both the first “modern war” and the first “media war”: new technologies such as the telegraph and the steamship allowed British audiences to see, for the first time, a war playing out almost in real time.5 This was the first war to be documented by independent war correspondents, on-the-spot sketch artists, photographers, and illustrated newspapers at home. During previous wars—the Napoleonic were the most recent in British memory—news had come in from soldiers’ letters, which took months to arrive. Now, special correspondents sent reports and drawings from the front that London newspapers published within two weeks. The war vastly expanded the audience for the ILN, which marketed its copy with sensational news accounts, especially news of the war’s mismanagement.6 Some of the newspaper’s war images depicted scenes unprecedented in a collective visual culture—damaged male bodies, piles of corpses, amputees. Many of these images functioned under realist codes that did not, as the chapter pursues, correspond perfectly with facts on the ground. Although the newspaper operated within a realm of fact ostensibly distinct from the realm of art, its pictures created ephemeral reality effects that served to link this visual reporting to more aesthetic, fictional realms.7

The war started over Russia’s aggressive moves into territory then occupied by the waning Ottoman empire. In response, Britain and France created an unlikely coalition with Turkey to repel the Russian invaders. Britain was especially motivated to protect its trade route to India, and the Russian stronghold of the Crimea became the major theater of battle. Russia was eventually defeated and forced to withdraw its forces from the Black Sea, but not without the allies suffering horrendous casualties. The war became a media sensation owing to the shocking revelations of incompetence by British military officials. This was the war that saw the notorious “Charge of the Light Brigade,” when the British cavalry made a foolhardy assault against Russian guns with calamitous results. Tennyson memorialized the battle in his famous poem: “Theirs not to reason why,/Theirs but to do and die.” More disastrous, however, was the failure of British leaders to effectively clothe and feed the army during a harsh Russian winter: heavy casualties from disease and starvation far exceeded deaths in battle, with as many as 80 percent of the 21,000 British and Irish casualties attributable to causes outside of combat.8 These atrocious conditions inspired the appearance of Florence Nightingale, who pioneered modern nursing practices in Crimean hospitals.

The chapter moves through a series of templates for Victorian war pictures, exploring some of the recurring spaces, subjects, and character types portrayed in the illustrated newspaper. They include the map, the panorama, “the Valley of Death,” scenes in the trenches, the war reporter, the battle’s aftermath, the amputee, and the nurse. Realism became an especially apt visual mode for Crimean journalism in representing the war’s many failures. British audiences were forced to confront narratives of shame and defeat following the mistakes made by leaders who didn’t know how to win battles, orchestrate supply lines, or care for the wounded. John Peck suggests that the scathing journalistic accounts written by W. H. Russell in The Times unfolded along the lines of a realist novel, revealing hard truths to a previously ignorant British audience.9 The war’s narrative in the newspapers took on a strongly moral tone in their critiques of aristocratic leaders, aligning these journalistic accounts with two of British realism’s defining traits, namely, its middle-class character and its emphasis on true vision as a moral imperative.

These traits differ from those of realist art in nineteenth-century France, and a comparison is instructive. French artists penned realist manifestoes in militant, uncompromising terms, reacting against the conservative strictures of the académie. “In reality nothing is shocking; in the sun, rags are as good as imperial vestments,” Louis Duranty announced in his periodical, Le Réalisme.10 Flaubert’s realist novel Madame Bovary (1857) incited a trial for its outrage to public morals; although Flaubert was acquitted, the judgment nevertheless accused the novel of producing “a vulgar and often shocking realism.”11 While French realists rebelled against authority with a willful turn to the taboo, British realists eschewed revolutionary fervor or a desire to shock. The mid-century British theorists of realism—John Ruskin, in Modern Painters (1843–59), George Henry Lewes, in “Realism in Art” (1858), and George Eliot, in Adam Bede (1859)—were not self-defined rebels protesting conservative art styles. These authors outlined aesthetic values that were inclusive to their audience, aiming to embrace rather than offend, and invoking Victorian middle-class values of care and moral good. If British realists turned viewers’ eyes toward unsightly truths, they did so in the name of a unifying social justice rather than out of a desire to transgress and potentially alienate audiences. Realism’s claims in Britain often implicitly based themselves in an idea of community, in middle-class moral narratives celebrating family, country, and spiritual goodness, evincing an educated sensibility based in science and fact.12 This was the realist optimism that inflected British newspaper accounts of the Crimean War, as we will see, even when events on the ground pointed in more nihilistic directions.

While French painters organized into a distinctive “Realist” movement, one that was debated and defended in the press, Britain had no analogous movement in the visual arts. Scholars seeking to understand British realism as a visual phenomenon have mostly focused on photography.13 British paintings did evince a range of reality effects, but these artworks were not understood by contemporaries to be making a radical turn toward “the real,” any more than they are studied as such today.14 (To note just one complicated example: Pre-Raphaelite painters used techniques of startling verisimilitude to portray subjects that were medieval, mythical, or fantastical.)15 The chapter thus makes an intervention in accounts of British nineteenth-century art by arguing for a key site of visual realism beyond painting and photography. Newspaper illustrations themselves did not invite realist manifestoes or declarations of intent by their makers. Yet the chapter will trace striking similarities between their journalistic visual strategies and those outlined by the British theorists of aesthetic realism, especially George Eliot, who conspicuously turned to visual models when announcing to the world what novels should aim to do.

Though a newspaper might seem like a distant medium from a classic realist novel, the chapter will show how both kinds of representational objects participated in a world-building enabled by similar kinds of reality effects.16 The chapter develops its multimedia account of realism by looking to Eliot’s Adam Bede, not only for its famous realist manifesto, but also for its engagement in novelistic modes of the descriptive, the authentic, the everyday, and the conventional. Adam Bede is set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars; the international warfare between empires becomes a fitting analogy for the smaller tragedies of the domestic, rural, and provincial. That Eliot chooses a Dutch painting as the ultimate symbol for a new realist art highlights the way that visuality itself worked to construct the realist project across genres: novelistic realism manifests as a gaze that combined objectivity with morality, with at times contradictory results. British realism across media entailed the superimposition of moral values onto a fact-based vision, recuperating grim scenes of working-class suffering into community-building imagery for a sympathetic, middle-class audience.

The chapter’s conclusion looks to one key afterlife of realism in war representation. I examine a popular BBC Three television documentary series, Our War (2011), to explore how a modern documentary continues to deploy familiar realist techniques. Even while the chapter notices likenesses across a range of dissimilar representational forms, however, it does not assert an imprecise equality between them. Each medium moves according to its own distinct generic rules and conventions. Moreover, while the analysis shifts from the factual realm of newspapers and documentaries to the fictional realms of novels and art, I don’t subscribe to a postmodern idea that understands all representation as text, endlessly referring to itself, and gaining no ontological purchase on a concrete reality. An external world does exist, with a different ontological status than that of fiction or art. The historical event is real: truths and facts are real. Yet the chapter will suggest that once the event enters into the realm of representation, the techniques used to narrate it share qualities with those of the realms of art.17 Those techniques, values, or clusters of metaphors themselves have a history, reinvented with each new medium. Traditional disciplinary scholarship has often insisted on generic differences as definitive; this chapter instead looks across media to track reality effects at a crucial moment in aesthetic, cultural, and technological history.

Representations of war make for a compelling case study in seeking to understand how realism works. The extremity of wartime experience, its stripping-away of civilized custom and accepted moral codes, its political complications and rhetorical usages, lend an intense, freighted charge to any realistic depiction. It is no wonder, then, that questions of how to represent war touch so closely upon questions of representation itself. This analysis ultimately thinks about realism as an aesthetic idea beyond high art, as a series of philosophical propositions rendered aesthetically, a vision both troubling and necessary in the journalistic portrayal of war.

Reading the Illustrated Newspaper

The aesthetic, fictionalizing realms of novels and paintings today seem distinct from the more objective, fact-based realms of journalistic media. That sense of divide, however, might feel increasingly thin in the current media landscape of partisan television channels and “fake news.” Likewise, tracing the divide between art and journalism in the nineteenth century is a similarly complicated task, especially in the earlier part of the century, when the norms of newspaper journalism were still inchoate. Readers did not yet presume, when the Illustrated London News began publication in 1842, that newspapers were organized around points of hard fact. The medium had been transforming itself since the early nineteenth century, moving from patchy news coverage, small print runs, expensive cost, and infrequent publication to a more genuinely mass phenomenon with broader news coverage, larger circulation, cheaper prices, and daily publication. Censorship and government control at the turn of the nineteenth century had given way to the ideal of a free press, subject to market forces.18 The full-time profession of “journalist” only emerged in the 1830s. Before this time, as Matthew Rubery writes, “there had been only a loose connection between journalists and the news.”19 Victorian newspapers continued an eighteenth-century tradition of expressing strong political opinions in editorial columns. But the invention of the electric telegraph in 1836 and Isaac Pitman’s perfection of shorthand in the 1840s led to a new reportorial investment in qualities of immediacy, transcription, and the eyewitness account.20 Anthony Smith argues that a universalized system of shorthand, in particular, transformed reporting into a kind of observational science, promising readers “the complete recovery of some semblance of reality.”21 The shift in values toward journalism as an objective kind of witnessing led to the first independent foreign correspondents being sent abroad to report back to English newspapers. The Crimean War was the first to be covered by “special correspondents” sent to document the battle. Journalists at mid-century numbered with scientists and ethnographers as new occupational identities whose professionalization depended on innovative forms of detached observation. These identities, however, did not yet cohere under a distinct ethos of objectivity.

The nineteenth-century newspaper also approached the precincts of art with the inclusion of illustrations. Although photographic technologies transformed publishing practices throughout the century, newspapers did not mass-reproduce actual photographs until early in the twentieth century. Newspapers like the ILN employed “special artists” who traveled to battlefields or other newsworthy locales and took pencil sketches on the spot. The artists then worked them up to more finished versions after the fact, sometimes washed with watercolors. The drawings were then sent from the Crimea to London on steam packet boats that also transported the British army’s mail. ILN staff artists transferred the drawings onto wood-engraving blocks, where they were engraved by a team working at maximum speed.22 With its hand-drawn, hand-engraved images, the illustrated newspaper occupied a nebulous borderland between journalism and art. That nebulosity is evident in Charles Baudelaire’s designation of Constantin Guys as “The Painter of Modern Life” (1859–63)—celebrating Guys for sketches he published while working as a war reporter for the ILN. Baudelaire’s essay, one of the nineteenth century’s most famous aesthetic manifestoes, bases its claims on images published in an illustrated newspaper. The confusion speaks to the way that early visual journalism did not yet connote the ideas of strict objectivity or even anti-aesthetics that distinguishes journalistic professionalism today. Early illustrated newspapers sometimes drew on photographs as models, offering a finely grained visual field and an unfiltered mass of details signifying an indexical relation to the subject pictured. More often, though, the illustrative sketch was selective and subjective in style, with personalized and often conventional choices by both artist and engraver about the image’s contents.23

The illustrated newspaper combined word and image to convey the presence of the present, the world “burst on the senses” with ever-increasing plausibility effects.24 The pictures in the Victorian illustrated newspaper offered a patchwork of small architectural windows opening onto the constructed topoi of readerly interest—newly built ships, bridges or trains; Parisian fashions; disasters, fires, earthquakes; wars; the Queen’s appearances; paintings at the Royal Academy; urban poverty; rural poverty; foreign ethnographies; local color.25 The newspaper’s heterogeneous yet not quite random version of “the world”—the types and conventions of its worldedness—transformed the unruly developments of the news into a series of pristine engraved views.26 Bolter and Grusin, in Remediation, note how the tricks of perspectival painting extended from the Renaissance to the modern computer screen, making picture space continuous with the spectator’s space and “promis[ing] immediacy through transparency.”27 They trace perspectivalism directly from painting to photography, but the nineteenth century’s plausibility effects also emerged from printing technology, from engravings and lithographs crafting boxes of the real before photography came to the fore as a mass medium. The illustrated newspaper, with its hectic, encyclopedic, spectacular jumble, strikes a resemblance to Walter Benjamin’s phantasmagoria, the entrancing lightshow symbolizing modernity’s spectacles, especially the array of industrialized commodities. In the Arcades Project, Benjamin writes of the urban phantasmagoria as “now a landscape, now a room.”28 The flicker between room and landscape also seems a perfect way to capture the small box of the newspaper picture, offered at hand size to be viewed in a private space, but opening up onto the world with a tantalizing illusion of depth and distance.

These phantasmagoric effects suggest how the illustrated newspaper’s realism was adjacent to its sensationalism. Its pictorial effects were pleasurable and entertaining, as seen in related phenomena like the panorama, diorama, photograph, and other mechanized lights and shadows. One popular London panorama depicted the city itself, intimating the way that the pleasure lay in mere illusionism. Visual effects of depth, surface, texture, light, space, height, and perfect sight—all functioned as attractions that appealed to the body and to the sensorium, especially the eyes. The thrill of the real helped to sell newspapers, pointing to a defining conflict at the heart of the modern newspaper’s existence, in reporting the news as a public good while also functioning as a commodity selling pictures.

The illustrated newspaper’s aesthetic qualities have led some scholars to see the medium as a successor to the history painting, as both are artistic conveyors of visual news—a genealogy that might renovate our sense of history painting as an obsolescent medium of faded grandeur.29 The history painting, for all of its allegorical styles, epic heroes, and bids for permanence, also served as the communicator and disseminator of an era’s contemporary events and political crises. The “history” label downplays the extent to which these massive canvases might have served as news for those who consumed them. A useful comparison is offered by a famous war painting of the seventeenth century, Charles Le Brun’s Franche-Comté Conquered for the Second Time (1674) (Fig. 2.1). The painting appears on the ceiling of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, commissioned by Louis XIV to commemorate the French victory over the Dutch. It celebrates the king as a divinely appointed, heroic individual, mingling with gods and allegories. He wears classical garb, channeling a divine favor that transcends any specific time. The territory he has conquered does not appear in any detailed sense. The painting instead dwells upon the figure and body of the king, a commanding, mythic presence amid a whirl of supplicating or violently subjugating figures.30 The discussion below will highlight the contrasts of a new visual realism invested in qualities of surface detail, of authentic spectatorship by a professionalized, detached observer, of everyday persons and prosaic temporalities, and of newly familiar war types and templates. Yet even while the illustrated newspaper projected an innovative, middle-class realist ethos, it still engaged, like the history painting, in narrating a story about power, violence, and national unity, using aesthetic means.

Fig. 2.1 Charles Le Brun, Franche-Comté Conquered for the Second Time. Ceiling painting at the Palace of Versailles, c. 1674. © Photo Josse/Bridgeman Images.

By the time of the Crimean conflict, the epic mode had come to seem both nostalgically desirable and hopelessly outdated for relating world-historical events. Tennyson published the first part of his Idylls of the King in 1859, allegorizing British social conflicts by looking back to Arthurian legend. But a commentator in Blackwood’s during the Crimean War satirically underscores the way that epic forms were being supplanted by works of a new temporality: “Fancy … the white-haired Nestor, and the sage Ulysses, reading, towards the close of the first year of their sojourn before Troy, the first book of the Iliad, to be continued in parts as a serial.”31 In the new time scale of journalism, historical events and their media coverage radically converged. The Blackwood’s critic humorously deflates lofty epic traditions by invoking the busy modernity of Victorian warfare and commercial print culture. His comment suggests the way that a war’s narrative flow invites aesthetic treatment, even while acknowledging the incongruity between grand historical events and their representation in Victorian new media.

The critic intuits a similar insight to that proposed by Benedict Anderson, who also studies newspapers as media comparable to novels or paintings, especially in their creation of phantasmagoric effects. Anderson argues that the modern nation emerges as a mirage generated by the illusionary world-building of both novels and newspapers. The newspaper’s endlessly renewing temporality of “the now” contributes to a mass ritual, an almost hallucinatory experience of national belonging:

The obsolescence of the newspaper on the morrow of its printing … creates this extraordinary mass ceremony: the almost precisely simultaneous consumption (‘imagining’) of the newspaper-as-fiction. … [This mass ceremony] is performed in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion.32

Though our modern-day sense aligns newspapers with the realms of fact and objectivity, Anderson instead describes “the newspaper-as-fiction,” a printed object that serves, like a talisman, as a source for the human experience of ritual and myth. The imaginary community of the nation emerges from “the lair of the skull,” both fictitious and profound. Anderson argues that both newspapers and novels create their imaginary shared communities using new, stable, measurable coordinates of space and time. But his account ultimately sees the newspaper as a representational artifact holding mythic and even quasi-religious import—not unlike a premodern history painting. In the sections that follow, I will examine the illustrated newspaper’s creation of reality effects that partake of both the concrete and the metaphysical, tying ephemeral or ideological effects to the particulars of the realist image.

Descriptive Realism: Surface and Map in the Valley of Death

Verisimilitude is an optically oriented mode focused on the scrupulous reproduction of details. Svetlana Alpers studies this mode in The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (1983), looking for meaning in the painting’s surface, in “what the eye can take in—however deceptive that might be.”33 Dutch paintings, known for their subtle light effects and minutely rendered surfaces, emerged, Alpers notes, from a new cultural investment in visual objectivity and experimental science. Objects represented within this descriptive mode do not appear framed and positioned so much as transcribed, as though seen through a camera obscura. In fact, as Alpers suggests, this painterly mode in Dutch art anticipates the indexical action of photography, or the “indexical sign” theorized by Charles Peirce (44). The pictured world seems to exist and expand beyond the frame, seen from the perspective of an unspecified observer. Verisimilitude is an effect that accords with the modes of scientific objectivity studied by Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, in which scientists attempted to develop machines that would replace flawed, unsteady hands and eyes.34 Alpers aligns the descriptive mode with maps and a “mapping impulse” in Dutch landscape paintings, as these emphasized qualities of “surface and extent” while diminishing the human presence (139). In literary texts, critics have located verisimilitude effects in moments of verbal description. Roland Barthes observes how a text’s inclusion of a seemingly inconsequential detail—a barometer atop a piano, in Flaubert’s novella Un Coeur Simple—exists for the sole purpose of weaving a fabric of reality. Lacking any symbolic import, the barometer sits amid a jumble of apparently meaningless objects in a bourgeois parlor; its sheer triviality ensures its “reality effect,” creating the surface of believable life and concretizing the novelistic world. As Barthes writes: “Flaubert’s barometer, Michelet’s little door, finally say nothing but this: we are the real.”35

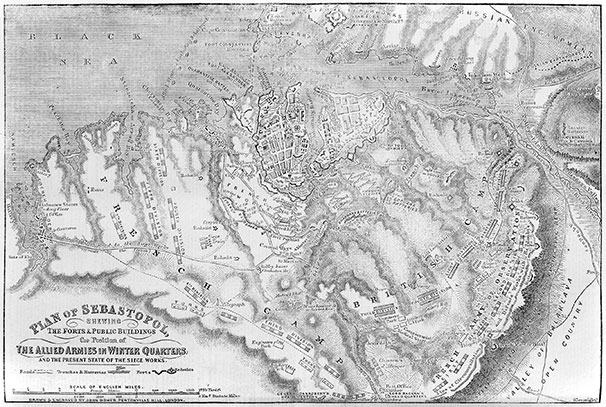

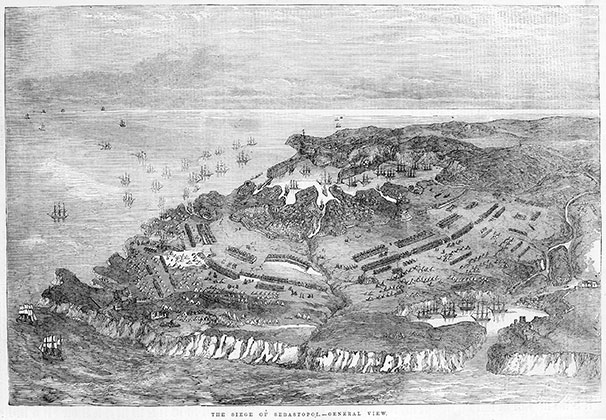

The descriptive mode appeared in the ILN’s portrayals of the Crimean landscape, the territory over which the war was fought. The newspaper published numerous maps of the Crimean peninsula, offering audiences at home a sense of the war’s terrains, boundaries, and sightlines. A map is a spatial analogue to a clock or a calendar, applying rational norms of measurement about which a spatially literate audience might gather and agree.36 A landscape scene rendered with a maplike sensibility presents a bird’s-eye view, a phrase indicating no particular viewer or viewpoint, “but rather,” says Alpers, “the manner in which the surface of the earth has been transformed onto a flat, two-dimensional surface” (141). Even while maps abstracted the ILN reader away from a corporeal real of wartime bodies and sensations, they registered a descriptive realism that conveyed a visual experience of territorial presence and concreteness. A view of the siege of Sebastopol, from November 1854, offers a landscape recognizable as the same one transcribed in a map of February 1855 (Figs. 2.2 and 2.3). The landscape view oscillates uncertainly between two and three dimensions, relinquishing volumetric solidity in favor of a sweeping breadth of surface. Natural features of water and steep cliffsides outline the land’s borders and dwarf the human presence, suggesting a world that expands beyond any individual measure. Only in the image’s center do we make out the tiny, besieged city of Sebastopol. While the scene was distant to the lived world of British audiences, the maps and maplike views invited them to see the Crimea as a realm in which they implicitly participated, as viewers sharing in the same lucid coordinates of space and shape.

Fig. 2.2 “Plan of Sebastopol, Shewing the Forts & Public Buildings, the Position of the Allied Armies in Winter Quarters, and the Present State of the Siege Works.” Illustrated London News, February 14, 1855.

Fig. 2.3 “General View of the Siege of Sebastopol.” Illustrated London News, November 11, 1854.

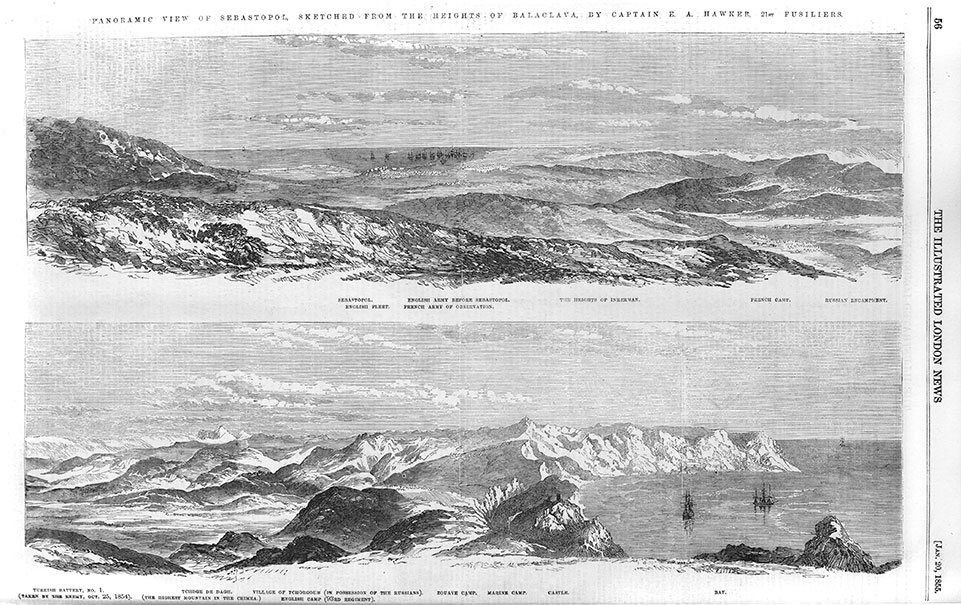

The ILN also pictured Crimean territorial views in the form of panoramas. These were large, sometimes fold-out scenes depicting a tracery of the horizon, labeled with different strategic points: English Fleet, Heights of Inkerman, Russian Encampment, and so on (Fig. 2.4). The panoramic fold-out in the magazine derived its name and concept from the popular London entertainment, first conceived in the 1790s, a massive, 360-degree painting, which spectators perused from a viewing platform in a purpose-built, circular space. Panoramas offered an immersive, engulfing experience, usually (again) a bird’s-eye view of a foreign place. Despite their unwieldy size, panoramas served as a form of early-nineteenth-century reportage: unlike history paintings, which aimed for a stately permanence, panoramas often depicted scenes that were topical and newsworthy, patriotic battles or naval scenes, or a recent revolution in France. Panorama entrepreneurs competed to be the first to depict an event, such as the 1834 burning of the Houses of Parliament. A panorama was a news source; as such, it was a vast form of ephemera, which is one reason why so few of these giant paintings still remain intact. The panorama and the illustrated newspaper were complementary media—in fact, the pictorial newspaper was one nail in the panorama’s coffin. The London entertainment had mostly died out by the end of the 1850s, and the Crimean War was one of the last to be dramatized in panorama form.37 When the ILN announces, in its 1842 inaugural issue, that it intends “to keep continually before the eye of the world a living and moving panorama of all its actions and influences,” the newspaper compares its own parade of pictures to the vast London technology, offering a timely, synthesized, and immersive version of “the world.”38

Fig. 2.4 “Panoramic View of Sebastopol Sketched from the Heights of Balaclava by Captain E. A. Hawker, 21st Fusiliers.” Illustrated London News, January 20, 1855.

The panorama was, like the maplike landscape, another fictive mode of looking that employed verisimilitude effects. It offered the illusion of full presence, a perfect 360-degree vision conveying the mastery of the all-seeing view. The panoramic view is both above and embedded, with a sense of rotation conveying a plenitude of horizontal visual information. The ILN’s full-spread panorama of the Crimean landscape serves as a rather boring war picture. Once again, the human scale is diminished in favor of sweeping landforms, a topographic arrangement of mountain, sea, and hillside. The human presence is barely visible, with tiny ships at sea and miniature encampments locatable only with the aid of the caption underneath. The image superimposes the reader’s gaze upon that of a military leader surveying the scene, presenting a sanitized war theater and an illusory sense of visual mastery.

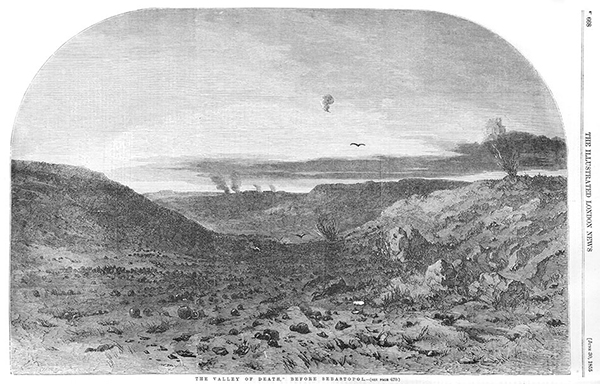

A similar descriptive logic underlies Crimean scenes of the famous “Valley of Death.” The ravine became famous, in Tennyson’s lyric, as the site of a brutal massacre: “All in the valley of Death/Rode the six hundred.” Yet the imagery does not portray a battle. Roger Fenton’s iconic war photograph of the terrain presents a muddy hillside strewn with cannonballs (Fig. 2.5). While Fenton’s photograph sold for an expensive 21 shillings—it emerged in the years before photography became a mass medium—the Valley of Death also appeared in cheaper, more mass-circulated media, such as in the ILN, and in war lithographs by William Simpson. Simpson’s version includes tiny men bearing a wounded soldier on a stretcher, the humans miniaturized against the towering hillsides. The ILN’s version, absent of soldiers, shows only a few scattered bones and a buzzard circling overhead (Fig. 2.6). It is striking that the newspaper allotted a full-page spread to a scene of vast emptiness, land and sky. The biblical title of “the Valley of Death” added a layer of allegorical grandiosity to pictorial content that was in fact new and unprecedented. Rather than portraying warriors clashing in combat, the imagery instead pointed viewers’ attention to the ground, to the vast and depopulated ravines, rocky, scrubby, and barren. The details of hillside and cannonball, minus the heroes, conveyed a descriptive effect of realism, a sense of reality ensured by the scene’s seemingly trivial surfaces. Refusing to center on heroic human actors, these scenes focused the eye on the details of a desolate, noneventful space that extends into a world beyond the frame. If a nihilistic view of war death hovers here in the implication that imperial nations sacrifice soldiers while contending for patches of dry earth and buzzards, that nihilism is dispelled by a faith in the vision itself, whose penetrating realism signifies a triumph of Western analytical perception.

Fig. 2.5 Roger Fenton, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1855. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Fenton Crimean War Photographs.

Fig. 2.6 “‘The Valley of Death’ Before Sebastopol.” Illustrated London News, June 30, 1855.

The verisimilitude effects of scenes in the “Valley of Death” did not necessarily coincide with the war’s reality. In fact, cannonballs flew into a number of Crimean ravines, and each picture potentially captures a different geography. Fenton’s valley of death is not the location of the ill-starred Charge of the Light Brigade hymned in Tennyson’s poem. Errol Morris recently accused Fenton of fakery for moving the cannonballs in his photo; in the original picture, the cannonballs had collected in the ditches along the road, a visual fact confirmed by newspaper imagery of the same scene.39 While the actual Crimean ravines served as the sites of violent butchery, or the mindless destruction wrought by an errant cannonball, the Victorian pictures of the empty ravines offered themselves as descriptive realist geographies signifying a truer truth of warfare, both unadorned and unspeakable, stripped down and existentially true.

Authentic Realism: Eyewitnessing and the Special Correspondent

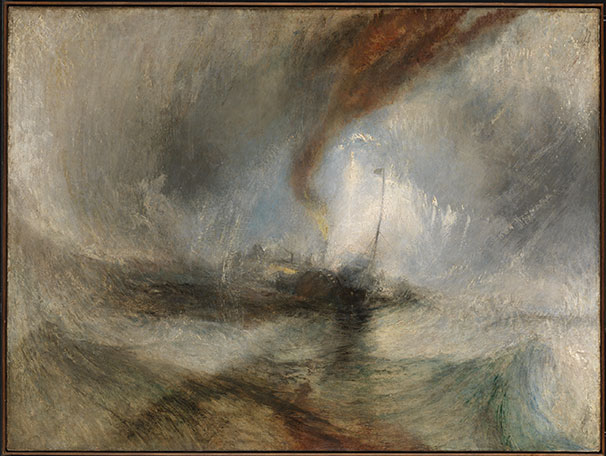

Another key reality effect conveys a sense of authenticity. This mode sacrifices precise details in order to render a subjective, first-person account. It implies a close alignment between the artist’s experiences and the scene portrayed; it often uses techniques of visual distortion or dissolution in order to express a sense of immediacy or “on the spot” experience. A classic example is J. M. W. Turner’s 1842 painting of a ship in a snowstorm, whose full title broadcasts its investment in authenticity: Snow Storm—Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth Making Signals in Shallow Water, and Going by the Lead. The Author was in this Storm on the Night the ‘Ariel’ Left Harwich (Fig. 2.7). An apocryphal account suggests that Turner was lashed to the ship’s mast. The painting conveys a sense of firsthand experience by omitting concrete details, choosing instead a bewildering swirl of grays to evoke the storm’s icy churn. The authenticity effect appears in modern-day films and TV shows that employ a shaky hand-held camera, constraining audience perception.40 In literature, authenticity effects can be found in stream-of-consciousness techniques or in the exuberant, subjective mediations of gonzo journalism. This mode often entails the communication of the maker’s subjective presence, whether as an adventurous artist or ethnographic observer. It became especially important in the nineteenth century with the ascendance of traveling journalists, whose truth-telling depended on communicating an on-the-spot account to readers and viewers back home.

Fig. 2.7 Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), Snow Storm—Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth Making Signals in Shallow Water, and going by the Lead. The Author was in this Storm on the Night the ‘Ariel’ Left Harwich. Oil on canvas, 1842. © Tate, London 2019.

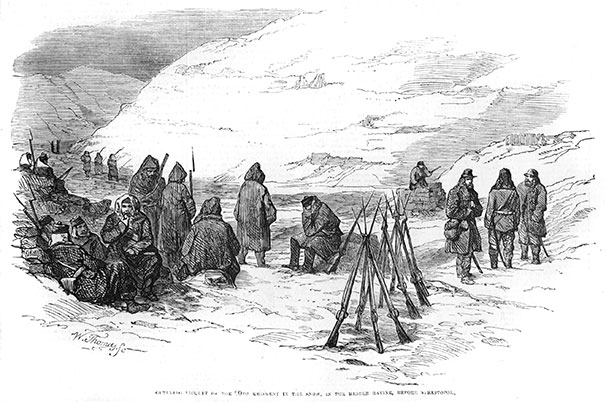

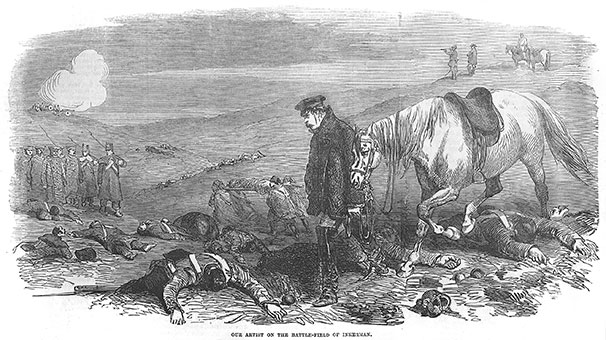

The ILN foregrounded the presence of its “special correspondents” and “special artists” on the Crimean battlefield, highlighting the novelty of this journalistic identity.41 The letterpress in an 1855 article describes how a pictured winter scene is not as detailed as it might have been owing to frost cramping the artist’s fingers. “You may depend on their [these sketches’] exact truthfulness: the want of finish to be found in them may be laid to my scarcely being able to hold a pencil in my hand from excessive cold.”42 The picture’s truthfulness is authenticated by the artist’s corporeal presence, resulting in a less precise rendering. The accompanying illustration uses minimal strokes to portray the huddled soldiers waiting in the snow (Fig. 2.8). One of the newspaper’s defining war images is “Our Artist on the Battlefield of Inkerman” (Fig. 2.9).43 The image is clearly fantastical, since the artist cannot be documenting a scene in which he himself is a participant. Yet a sense of realism inheres in his authenticity as an eyewitness; the word “correspondent” itself connotes subjective eyewitnessing, with its roots in letter-writing. The ILN image implicitly aligns the journalist with the foot soldiers, walking his horse rather than riding it. (This imagery also would have resonated with the gruesome particulars of the Battle of Inkerman, whose hard-won victory was achieved through the efforts and brutal deaths of the Allied soldiers on foot.) The reporter is a kind of warrior for the truth, conveying his vision of the war “on the spot.” His gaze looks to the ground, which is littered with corpses. The phrase “taken on the spot” appeared throughout ILN war coverage: the concept represented a new idea in communications, describing truth as a function of a particular spatio-temporality, in which an eyewitness reproduced a view of a place within a precipitous moment of time.

Fig. 2.8 “Outlying Picquet of the 90th Regiment in the Snow, in the Middle Ravine, Before Sebastopol.” Illustrated London News, March 10, 1855.

Fig. 2.9 “Our Artist on the Battlefield of Inkerman.” Illustrated London News, February 3, 1855.

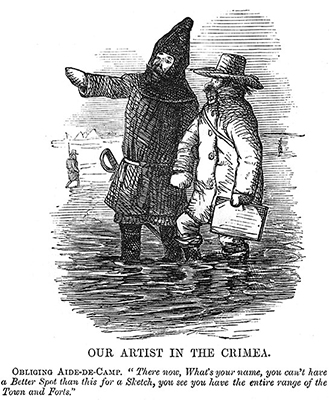

Punch understood the appeal of this kind of authenticating, eyewitness imagery and parodied it in their own version of “Our Artist in the Crimea” (Fig. 2.10).44 Here an “obliging Aide-de-campe” positions the visiting artist knee-deep in water, in the Balaclava harbor. The image mocks the suffering that the journalist has to undergo in the name of on-the-spot reporting—a tradition still very much in place today, as journalists position themselves in the heart of dangerous storms, raindrops hitting the camera, in order to authenticate their account of dangers braved while pursuing the story. The Punch cartoon also has a political undertone, implying that the artist has been moved out of range by military authorities who want to undermine his too-acute vision of the war’s disasters.

Fig. 2.10 “Our Artist in the Crimea.” Punch, January 6, 1855. Courtesy University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center.

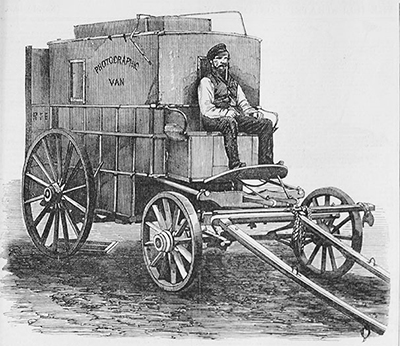

The Crimean War witnessed the invention of a new kind of journalistic identity in the form of the deeply individualistic reporter who travels for truth and takes risks to find it—as embodied by special correspondents like W. H. Russell of The Times, whose fiery attacks on the military establishment helped to bring down the British government. This identity also accrued to the photographer Roger Fenton, even though his occupation was not coded as “journalistic” at the time. Fenton had been sent to the Crimea by the Manchester-based publishers Thomas Agnew and Sons in order to provide photo portraits as the basis for a history painting by Thomas Barker.45 His images became interwoven with journalistic enterprise when some of them were engraved for the Illustrated London News. The newspaper printed an iconic image of the new photographic visual reporter, “Mr. Fenton’s Photographic Van.—From the Crimean Exhibition” (November 10, 1855) (Fig. 2.11). The picture reproduces a Fenton photograph that appeared in a London exhibition of his Crimean work. Fenton developed his Crimean negatives inside a darkroom “van” that had been jerry-rigged from a carriage. The picture portrays the adventurous photographer quite literally as a traveler for the truth, journeying atop his mobile darkroom.46 (Again, factual details mitigate somewhat against this mythic portrayal: the man seen driving the van is in fact Marcus Sparling, Fenton’s assistant, a subordinate whose photographic contributions have largely been lost from the historical record.)47

Fig. 2.11 “Mr. Fenton’s Photographic Van.—From the Crimean Exhibition.” Illustrated London News, November 10, 1855.

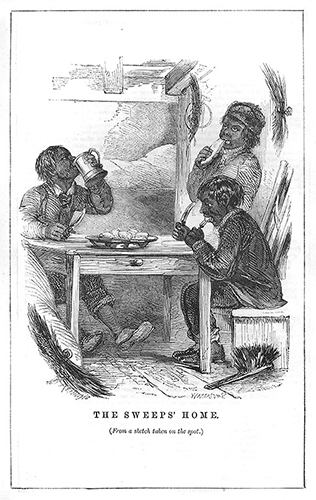

The new reportorial identity of special artist or special correspondent gained its power from the realist effect of authenticity, a truthfulness guaranteed by a journey and the communication of a first-person presence. We can observe a similar identity-formation in Henry Mayhew’s three-volume London Labour and the London Poor (1851), a contemporaneous work of innovative ethnography that also combined words and images. Collecting Mayhew’s newspaper articles from the 1840s, the volumes offered a detailed account of different types of London workers, accompanied by illustrations engraved after daguerreotypes. In the preface, Mayhew highlights the novelty of his project and announces himself as “the traveller in the undiscovered country of the poor.”48 He analogizes his project to that of a daring explorer, implying that his account is authenticated by the journey itself. Tim Barringer argues that Mayhew’s illustrated Londoners shared a similar exoticism with the African natives pictured in the travel narratives of Speke and Livingstone. As Barringer notes, Mayhew’s travel metaphors reflected those of the Victorian adventurer abroad, lending an authentic veneer to what was often a subjective visual account of otherness and difference.49 An engraving of chimney-sweep children at home portrays them with blackened faces, making the chimney sweep into its own racial category (Fig. 2.12).50 For all of Mayhew’s ostensibly scientific language and objective taxonomy, Barringer shows how many of his images are indebted to an urban Gothic imaginary, of the kind found in Dickens’s Oliver Twist. Mayhew’s image of the blackened chimney sweeps affirms its own authenticity with its caption: “The Sweeps’ Home. (From a sketch taken on the spot.)” The eyewitness account “on the spot” testifies to what might seem a strange or even unbelievable sight, in this case the racial darkening of British children in London.

Fig. 2.12 “‘The Sweeps’ Home.’ (from a sketch taken on the spot).” Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, Vol. 2, 1861–2. Courtesy Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives.

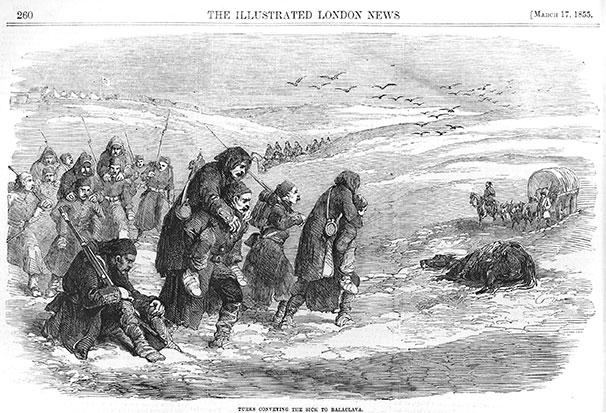

In the evolving figure of the traveling correspondent, then, this authentic, first-person traveler came to be associated with a certain kind of challenging subject-matter, previously unknown, exotic, alluring, and risky to observe. The Crimean War provided many opportunities for this kind of reporting, since it offered the spectacle of a range of diverse peoples, with soldiers who were British, French, Turkish, Russian Croat, Montenegrin, Zouave, and Tartar. One striking ILN illustration, rendered by an on-the-spot observer, presents a powerful scene of suffering and otherness. In “Turks Conveying the Sick to Balaclava” (Fig. 2.13), Turkish soldiers carry wounded men on their backs, while a dead horse lies in the snow and vultures circle overhead.51 The image emphasizes the soldiers’ Turkishness with their hoods and distinctive, mustachioed physiognomies. The letterpress conveys the authentic feelings of the eyewitnessing special artist: “‘It is one of the most heart-rending sights,’ says our Correspondent, ‘to see these unfortunate fellows carried on the shoulders of their poor comrades, who have sometimes to pay dear for their sympathy.’” The letterpress goes on to meditate on the Turkish character more broadly in comparison to the French and English, especially in its greater tolerance for pain and capacity for endurance.52 (As a matter of fact, however, the manual mode of transport was adopted by the British as well as the Turks, since British forces also lacked necessary ambulances.)

Fig. 2.13 “Turks Carrying the Sick to Balaclava.” Illustrated London News, March 17, 1855.

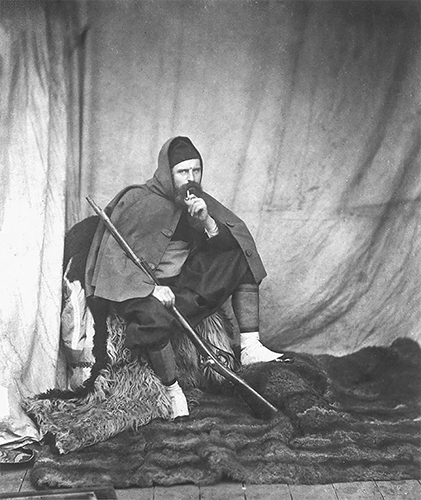

While this imagery in the first instance works to divide the civilized observer from the more primitive ethnographic subject, one implication is that the new traveling correspondent is a liminal figure who takes on some of the dangerous, savage, and alluring qualities of the people he documents. These stereotypical qualities attain even today, in the type of the hardened, masculinist traveling correspondent or photojournalist, whose edgy, on-the-spot adventures testify to the authenticity of his reporting. This idea is encapsulated in the famous self-portrait taken by photographer Roger Fenton in Zouave costume (Fig. 2.14). Fenton took the picture in his London studio after the war, as part of a series of photographs on “Oriental” themes.53 The Zouaves were a French unit of Algerian soldiers famed for their ferocity in battle. They appeared as frequent objects of ethnographic curiosity in the ILN, reflecting the broader British fascination with the racialized, subject peoples who served as the mercenaries of Western empires.54 Although Zouave regiments by 1853 largely consisted of men of French European descent who had served in Algeria, these soldiers still connoted captivating qualities of savagery, primitivism, and racial otherness.55

Fig. 2.14 Roger Fenton, Self-Portrait in Zouave Uniform, 1855. GL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

When Fenton pictures himself as a Zouave, he participates in an enduring Romantic tradition—familiar from Byron’s portrait in Albanian costume—of the artist identifying as exoticized outsider, heightening his identity as a unique, privileged kind of creative person. These associations inform the modern idea of the war correspondent, who risks his life to report from the field. Fenton, of course, made his self-portrait as Zouave in his London studio, far from the Crimean dangers. Nevertheless, his image gains its power by implying a mirroring between the special artist and his exotic subjects. The foreign correspondent is a boundary-crossing person uniquely equipped to translate exotic ethnographies for an audience back home. Truth itself becomes both expedition and trophy, a thing to be observed and claimed at a particular moment in time, by a special kind of person, using his own authentic voice, and conveying his own distinctive vision.

Everyday Realism: War Labor in the Trenches

A third realist mode entails the turn to the common and the everyday as the concerns of representation. While this mode appears to deal with subject-matter rather than style, the two aspects are deeply entwined in the portrayal of the habitual, the ordinary, and the routine, as opposed to the extraordinary, the heroic, or the romantic. The realist mode of the ordinary features the repetition inherent to practices of everyday life, as well as the passing of fleeting, ephemeral moments: both of these time-forms oppose the temporalities of the eternal or permanent associated with more elevated art styles.56 Linda Nochlin, in her study Realism, points to Baudelaire’s famous definition of modernity as “the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent” in her assessment of realist temporality.57 For many scholars, realism’s turn to the common and the everyday coincided with the rise of capitalism, as the new middle classes patronized artworks that portrayed their own rhythms of daily life.58 Yet Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis argues that realism’s modes are transhistorical stylistic choices stretching all the way back to the Bible. He contrasts Homeric realism—portraying elevated characters who are externalized, brightly visible, and unchanging over time—with a biblical realism portraying everyday kinds of characters who are psychologically deep, and who exemplify “the concept of the historically becoming.”59 For Auerbach, the most compelling mimetic style engages in a historicist accounting of character, by which characters change over the course of their lives, and struggle with the conditions of their particular historical moment. Auerbach aligns this historicist realism with the lives of insignificant persons, a tradition beginning with the Christian emphasis on humility and the humble life. I follow Auerbach, then, in distinguishing a historicist realism that implicitly looks to more everyday kinds of persons and practices, and is rendered within the temporal parameters of the routine or the contingent.

In ILN reporting, effects of historicist realism surrounded the unprecedented Crimean imagery of the life of the working-class soldier. Previously, war portraiture had focused exclusively on generals and officers whose names were recorded in the annals of military history. This portraiture continued to be popular; the ILN printed many elaborate portraits of Crimean generals, and many of Fenton’s photographs depicted officers, perched atop the status symbol of the horse. Yet a huge gulf divided aristocratic officers from the men they commanded, soldiers who were recruited from impoverished rural villages, some fleeing the law. The rank-and-file soldier represented the most destitute and uneducated of the British and Irish male poor. Their reputation before the war, in the words of the Times, was that of “savage, murderous, ravaging and destroying creatures.”60 These were the men depicted manning the trenches in newspaper images of the siege of Sebastopol, in winter scenes from 1854–55.

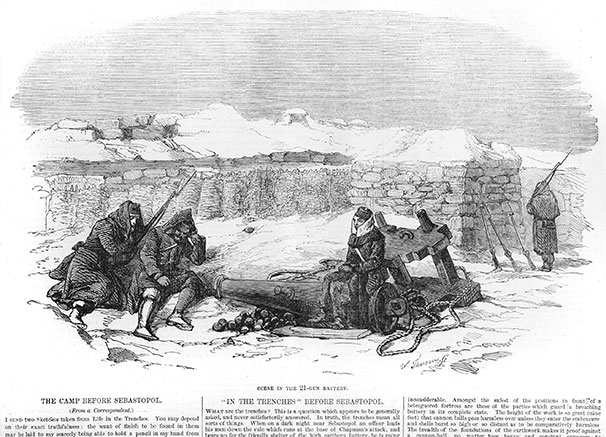

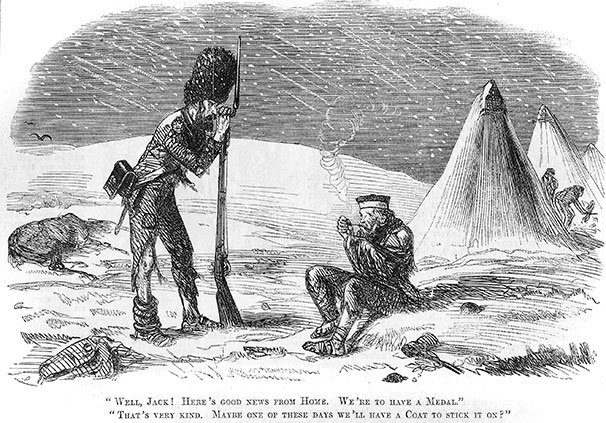

The war’s stark class divide lent trench imagery a volatile political charge. Whereas the elite Crimean war officer enjoyed a luxurious life of horse races, local tourism, balls, and champagne feasts, the rank-and-file soldier executed the manual labor of the war, maintaining the siege line, enduring regular bombardments and the frigid weather.61 When illustrated newspapers moved to portray nameless soldiers in the trenches, this imagery accompanied an often explicit political critique, as the newspapers lauded the lowly soldier in accusations against incompetent military leaders who allowed these men to die. The road from Balaclava harbor to the front line was six miles long; it became almost impassable in the winter, and boatloads of supplies, food, and winter coats lay useless in the harbor with no way to transport them. The ILN scenes “in the trenches” depicted nameless men shivering in snow, huddled behind fortifications, enduring the long winter (Fig. 2.15). Punch published a cartoon in 1855 whose winter war imagery borrowed directly from that of the ILN (Fig. 2.16). Two soldiers converse in a snowy camp; one says, “We’re to have a medal.” The other replies, “That’s very kind. Maybe one of these days we’ll have a coat to stick it on?”62 Centering on the mundane circumstances of working-class men trapped in the cold, these images invoked a historicist realism, portraying a suffering that was both prosaic and infuriating.

Fig. 2.15 “Scene in the 21st Battery.” Illustrated London News, March 10, 1855.

Fig. 2.16 John Leech, “The British Forces and the Crimean War.” Punch, February 17, 1855.

In depicting the temporality of siege labor, trench imagery mostly eschewed the drama of battle scenes. A siege by its very nature entails boredom and waiting around, as soldiers perform the routine work of war maintenance. In the ILN’s “siege supplement” of November 1854, an image captures the mundane quality of the war’s everyday life: men are arranged around a quiet cannon in postures of relaxation and repose, chatting with each other in easy camaraderie, one with his head resting on his hand.63 Fenton’s version of this imagery, titled “A Quiet Day in the Mortar Battery,” portrays two napping soldiers and a lookout at the wall, showing his ungainly backside. Trench imagery engaged the codes of a historical realism by turning our eye to the average soldier as he performed daily routines, many of them undignified and unheroic. Viewers in the 1850s would have been struck by how these images differed from more traditional war pictures depicting singular, peak events. Trench scenes captured the incipient conditions of modern war, portraying soldiers waiting in limbo while exposed to dangers that were invisible, unpredictable, and abruptly violent. War’s temporality under codes of historicist realism becomes contingent and momentary, rather than glorious and epochal.

If the trench came to signify a new site of war realism, its effects were both historicist and also, I would suggest, authentic. The phrase “in the trenches” today gestures beyond wartime, describing any kind of deep presence based on experiential immersion. A person working “in the trenches” gains authentic knowledge guaranteed by firsthand experience, elevated by the intimation of suffering. When the ILN depicted the working-class soldiers fighting in the trenches, it created a new kind of authenticity effect, one that has become familiar to us today. The novelty of the idea in 1855 is clear in the way the ILN puts the phrase “in the trenches” into quotation marks in an article illustrating siege labor. “What are the trenches?” asks the letterpress, explaining to readers at home all of the dangerous yet routine siege actions and movements.64 As the OED notes, new compound phrases with “trench” entered the English language in the 1850s, among them “trench fighting” (1855), “trench life” (1855), and “trench grave” (1854). The ILN’s trench imagery united the everyday with the authentic, demonstrating how multiple reality effects can occur together, making them at times not completely separable or distinct.

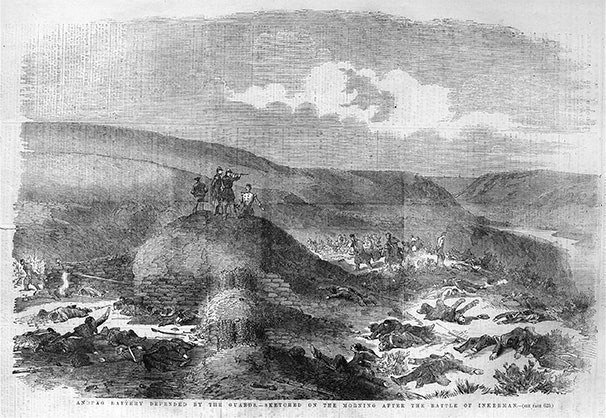

A historicist realism also characterized the ILN’s new imagery of war death. While some Crimean imagery did represent battles in a traditional, heroic mode, with soldiers rushing forth in grand costumes and pennants flying, more haunting and original pictures depicted the battle’s aftermath. The temporality of the posthumous governed grim scenes of battlefields strewn with corpses, both human and equine. The Illustrated Times, one of the ILN competitors, published an aftermath scene depicting a mass grave, with a pile of bodies, both human and horse, waiting to be interred.65 The mere portrayal of a corpse is not in itself inherently realist: Christian art had long portrayed martyrdoms that were typically grand, sacred, and eternal. But Crimean visual journalism handled the corpses in a new way, rendering the postures of death according to more everyday codes (Fig. 2.17). A scene in the ILN depicts “The Morning after the Battle of Inkerman” with corpses littered across the battlefield in various postures of casual carnage.66 Soldiers do not appear in meaningful or sublime poses, as would befit a sacrifice for a glorious cause. Instead, we see bodies draped carelessly across the earth, many of them face-down, like anti-portraits, a blatant sign of the destruction of the individual. These poses would have spoken powerfully to Victorian viewers accustomed to expressive, theatrical gestures. The vision presented is of mundane death, an aggregate of sad facts, rather than an elevated or transcendent event. War death becomes a subset of Baudelaire’s modernity, transitory, fugitive, and contingent, a part of war’s predictable ritual.

Fig. 2.17 “Sandbag Battery Defended by the Guards—Sketched on the Morning after the Battle of Inkerman.” Illustrated London News, December 16, 1854.

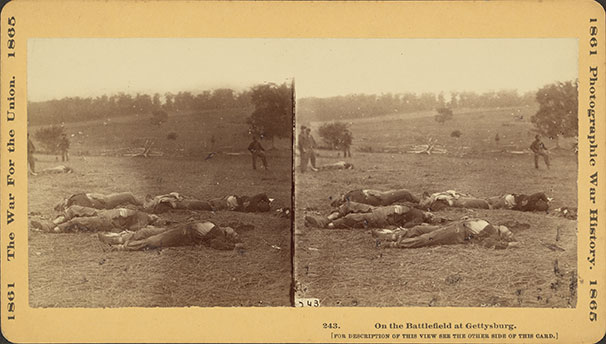

These ILN battlefield scenes produced reality effects with an important afterlife. I would argue that this imagery informed the notorious, corpse-strewn American Civil War photographs taken by Mathew Brady and his team in the early 1860s. Brady’s images became possible in the wake of quick-moving technological innovations: whereas, in 1855, photographs were still expensive and difficult to reproduce—Roger Fenton’s Crimean photographs were elite, precious, and limited-edition—by 1863, photography had become a new mass medium, with cheap cartes de visite and stereoviews circulating in the millions.67 Civil War battlefield scenes, such as a famous 1863 photo of the Gettysburg battlefield (Fig. 2.18), appeared as stereoviews under the seal of Mathew Brady’s huge commercial photography operation, which used corpses to mass-market photographic commodities. These photos subordinate the corpse to the landscape in a remarkably similar manner to the ILN reportage. They produce casual postures of death, in which bodies are scenic parts of a picturesque countryside, rather than centering their own transcendent drama. Photography historian Alan Trachtenberg argues that Brady’s photographs performed a “staged informality” reminiscent of the hand-drawn sketch, as seen in the title of the book where some photographs appeared, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War.68 (Again, a reality effect without the real: Trachtenberg uses the word “staged” to describe the way that some Civil War photographers moved corpses to create their elegant compositions. At times, the corpses were played by living actors.) The hand-drawn sketch would have been a familiar style of visual reportage for American viewers perusing their own illustrated newspapers, such as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly. These American newspapers all imitated the visual formulae developed by the ILN. In fact, Frank Leslie, the impresario of American pictorial journalism, was an Englishman who had managed the ILN’s engravings department before moving to the US in 1848.69 In other words, the famous Civil War battlefield photographs can be seen as modeling their depictions of war death on the Crimean War visual reportage inaugurated in British newspapers. Nameless soldiers featured in scenes of carnage both well composed and casual.

Fig. 2.18 James F. Gibson/Alexander Gardner, On the Battlefield at Gettysburg. Stereoview, 1863. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-18,947.

Neither British nor American photographs were able to depict battles while they occurred in the nineteenth century; photo technology would not be able to capture the instantaneous action of wars until the twentieth century. In the pre-photographic moment of realist reportage, the battlefield’s posthumous temporality—war action finished, stilled now, quiet with corpses—expressed itself in the visual conventions of the landscape sketch, merged with the realist interposition of dead figures. These corpses might be arranged gracefully within the landscape according to picturesque conventions, scattered near and far; but their inanimate, dumb postures violated the norms of portraiture, invoking a new temporality of war death, and a new historicist reality effect, bringing death into the realm of the everyday.

Conventional Realism: Amputees, Nurses, and other War Types

The fourth and final realist mode I consider operates by creating a sense of plausibility based in established convention. Readers or viewers evaluate an artwork’s realism by comparing it with their own expectations of the world. Christopher Prendergast writes that the mimetic sense in literature depends on “stocks of knowledge” shared by writer and reader: realism within the world of the plausible depends on “a circular principle of reciprocity” such that the reader believes the text’s mimetic claims because these affirm readerly expectations.70 The plausible mode of realism might not seem realistic at all, since it bases itself in prejudices and assumptions rather than in observed experience. Yet many critics have argued that a sense of conventionality underlies all the modes of realism. E. H. Gombrich, in Art and Illusion (1960), suggests that visual mimeticism is purely stylistic, as artists evoke reality by recourse to established visual schema that change over time, from Egyptian art to the present day.71 In literary criticism, Lukács argues that characters in nineteenth-century novels seem realistic owing to their “typicality,” for the way they mediate between a particular person and a general type.72 Lukács puts a positive spin on this realist action, since a novel’s masterful blending of individual and type—in Balzac, for example—allows the novel to reveal the stark dialectics of political economy underpinning social life. But other critics have strongly critiqued realism’s dependence on convention, accusing it of bad faith and deceptive practices—from Barthes, to Terry Eagleton, to Fredric Jameson.73 Eagleton, reviewing Auerbach’s Mimesis, censures Auerbach for being optimistically conventional in presuming that representations of everyday life are more real than, say, depictions of kings or manor houses. “Cucumber sandwiches are no less ontologically solid than pie and beans,” Eagleton writes.74 The plausibility effect, in many ways describing the conventionality of conventions, exists at a different ontological level than the other three modes discussed in the chapter. All three are underwritten in some sense by this final realist mode of conventionality or plausibility, destabilizing their relationship to any actual reality.

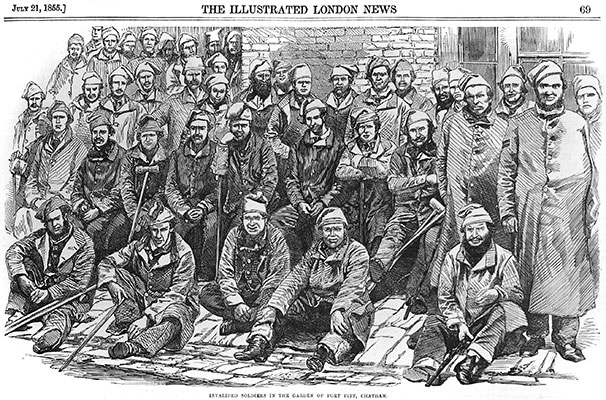

Crimean war reportage introduced a series of types and templates that have since become familiar in war reporting. One new and incendiary type was that of the soldier amputee, a figure mobilized by the newspapers in their attacks on military and government incompetence. Amputees themselves were not new to the British military visual tradition, as mass-circulated images of Admiral Nelson had celebrated the one-armed naval hero of the Napoleonic era. But Nelson’s portraits tended to focus on his impressive spangled uniform, highlighting his heroic public persona. Likewise, British veterans of the Napoleonic Wars appeared as heroic, domesticated figures, symbols of British triumph and national pride rather than shame or defeat. These figures did not call for any new grim vision of war and its victims. By contrast, images of Crimean amputees depicted unknown soldiers from society’s lowest echelons, fighting a losing war. During the spring and summer of 1855, as Britain came to reckon with the consequences of the war’s disastrous winter, the ILN published a series of illustrations engraved from photographs taken by Joseph Cundall and Robert Howlett at British veteran hospitals. In an image from July 1855, rows of grim-faced, stoic men pose with their numerous crutches (Fig. 2.19).75 Two men on the right stand with arms buttoned conspicuously under their coats, implying the limbs in slings underneath. The poses are casual yet dignified; one seated man’s leg is missing. Although the men have been grievously injured, they still maintain a masculine dignity, with their upright bearing and buttoned greatcoats.

Fig. 2.19 “Invalided Soldiers in the Garden of Fort Pitt, Chatham.” Illustrated London News, July 21, 1855.

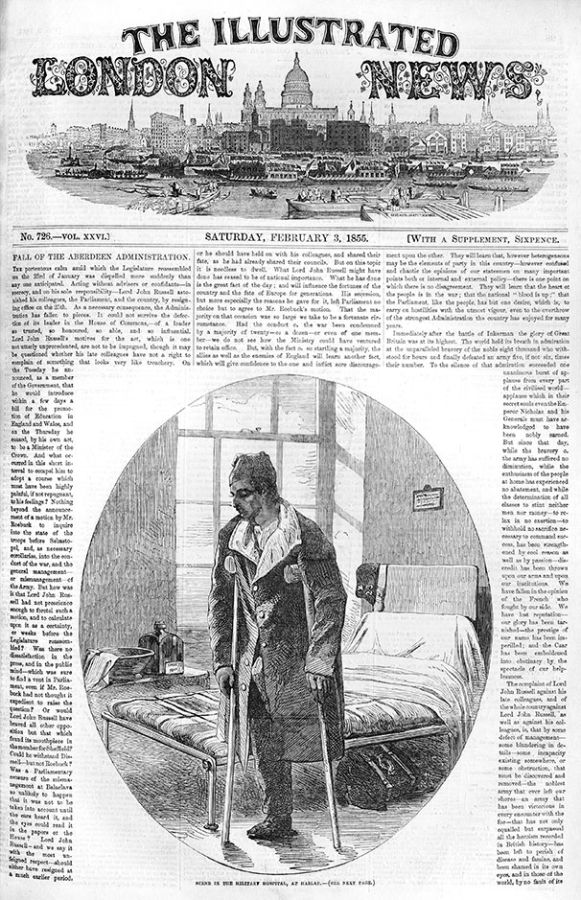

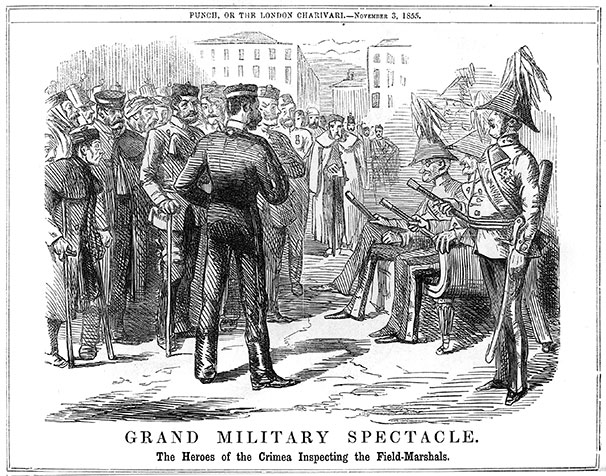

The imagery combines a number of reality effects—verisimilitude, in the engraving from a photograph, recording the discomfiting truth of a soldier’s maimed body; and mundanity, in the choice of humble soldiers as the subjects for a portrait. The amputee also became a new, conventional type in Crimean War imagery, defined by his lowly character, his humble suffering, and his heroic masculinity, affirmed despite his injuries. There was no idea that these veterans might be returned “as good as new” to a British workforce.76 They existed instead as objects of extreme public curiosity, sentimentalized bearers of visual pleasure, even erotic interest, with their taboo wounds tucked discreetly behind folded shirt-sleeves and pant-legs. The ILN used the realist type of the heroic amputee as ammunition in the middle-class periodical’s moral assault on aristocratic privilege. Appearing on the front page of the ILN on February 3, 1855 (Fig. 2.20), a picture of an amputee at a British veteran’s hospital accompanies news of the fall of the Aberdeen government, due to the war’s abysmal failures. The touching, vulnerable, handsome masculinity of the amputee signifies his heroic sacrifice for the nation, superimposing his body onto the body politic, and relocating the sense of national belonging away from inept military leaders. These kinds of politicized images worked to incite professionalizing reforms in the military and civil service after the war. A trenchant Punch cartoon of 1855 generates a gallows humor by inverting the expected types of military heroism. In “Grand Military Spectacle: The Heroes of the Crimea Inspecting the Field Marshals” (Fig. 2.21), wounded soldiers stand in manly, honorable postures—with visible bandages, crutches, and missing limbs—while they survey a crew of seated, sickly looking generals.77 The new realist type of the veteran, with his admirable suffering and still-potent masculinity, appeared in publications like Punch and the ILN to function as a sign of the newspaper’s moral gaze, testifying to its evolving role as a government watchdog in prosecuting a case against incompetent and immoral leadership.78

Fig. 2.20 “Fall of the Aberdeen Administration” and “Scene in the Military Hospital, at Haslar, [UK].” Illustrated London News, February 3, 1855.

Fig. 2.21 “Grand Military Spectacle: The Heroes of the Crimea Inspecting the Field-Marshals.” Punch, November 3, 1855.

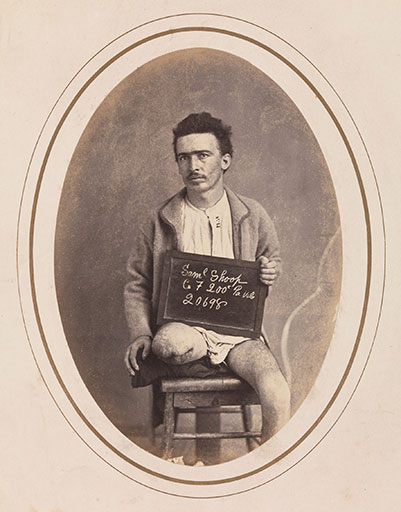

While journalistic images of nameless or working-class wounded men were in many ways unprecedented, these Crimean portraits still adhered to Victorian visual conventions. Their conventionality becomes striking when we turn for comparison to the amputee photographs taken by Reed Bontecou during the American Civil War. Bontecou photographed veterans to help them in pursuing pension claims; the images never circulated in a newspaper, being instead intended for an audience of surgeons and government officials. The photos depict wounded soldiers lifting their sleeves and pant-legs—or even appearing unclothed—in a graphic, undisguised portrayal of wounds and stumps, the body deformed (Fig. 2.22).79 These pictures functioned as documentary proof, depicting humans as specimens; they made no explicit moral claims upon their audience. By comparison, the ILN amputee portraits seem polished and positively staged. The lone soldier portrayed on the ILN’s front page in 1855 appears amid the domestic peace of his hospital bedroom, bed neatly made, inspirational quote pinned to the wall, and greatcoat discreetly covering the absent leg. He stands upright, his head bowed with humility; any gruesome details have been carefully omitted. Because veterans were often portrayed in domestic hospital settings, they signified an especially sentimental form of mid-Victorian masculinity, both courageous and vulnerable, needing of feminine care.80 This soldier appears as a masculine type deeply sympathetic to a British audience.

Fig. 2.22 Reed Bontecou, Private Samuel Shoop, Company F, 200th Pennsylvania Infantry. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 1865. © Stanley B. Burns, MD & The Burns Archive.

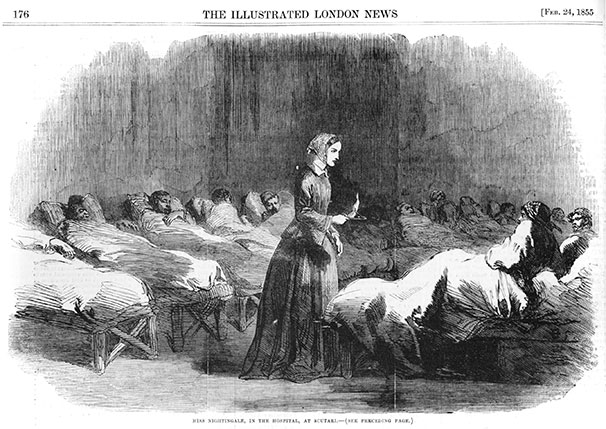

Victorian gender conventions played a key role in familiarizing the new visual vocabulary of the war, for both men and women. An iconic female type originating in the Crimea was that of the nurse, incarnated by Florence Nightingale, “the Lady with the Lamp.” On the one hand, these images were again without precedent: in an era when no respectable woman worked for money or left the home, Nightingale and her cohort created a new profession for women in the public sphere. Yet despite Nightingale’s radical adventures in a Victorian warzone, newspaper illustrations and lithographs framed her according to traditional codes of femininity. Numerous scenes portrayed her as a young beauty ministering to wounded men in their hospital beds in the Crimea (Figs. 2.23 and 2.24). These images are among some of the most patently fictitious of the war: the main hospital at Scutari, where Nightingale worked, was built atop an open sewer, festering with disease, obscenely overcrowded, lacking beds, with one nurse or male orderly for every forty or fifty patients.81 One nurse wrote in her memoir of removing maggots from men’s wounds by the handful.82 Yet the pictorial accounts of Nightingale depict a domestic bedroom scene, unmistakably erotic, as the pretty nurse attends to wounded men in their beds.

Fig. 2.23 “Miss Nightingale, in the Hospital, at Scutari.” Illustrated London News, February 24, 1855.

Fig. 2.24 (After) Joseph Austin Benwell, Florence Nightingale in the Military Hospital at Scutari. Colored lithograph, c. 1856. Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo.

Depictions of both nurses and veterans helped to re-establish gender roles that the war in fact had deeply disrupted. Wounded veterans who might have embodied a defeated, effeminized, or even castrated masculinity were reinscribed as manly heroes. And nurses who were creating a new profession for women were reinscribed as saintly, ministering angels. These war figures exceeded mere conventionality to achieve a realist conventionality, in their taboo, challenging, potentially unsightly associations. Yet their conventionality ultimately worked to reinscribe them within familiar Victorian codes. The iconography surrounding the Lady with the Lamp is especially ironic, given that one of Florence Nightingale’s major contributions was to the field of statistics; she was in fact a master statistician, an innovator in the field, a fact that still surprises in the twenty-first century. Yet the nurse and the veteran became conventional types, shoring up Victorian expectations regarding the masculine and the feminine, and registering a reality effect by conforming to the expectations of newspaper readers at home.

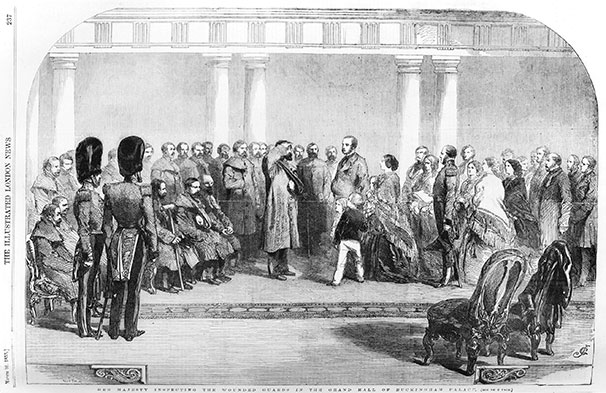

The imagery surrounding Florence Nightingale, I would suggest, made her into a figure for mid-century British realism itself. “The Lady with the Lamp” always appeared appointed with her light-source, shining illumination on the wards of wounded men. She became a conventional type for moral looking, the true sight defining British realism as an aesthetic practice. The beam of light emitted by the Lady’s Lamp figuratively imbued the visual sense with curative powers, a restorative gaze superimposed upon that of the newspapers who disseminated her image. In fact, Crimean War imagery produced a number of conventionalized figures for the sympathetic feminine spectator, emphasizing her virtuous gaze. Queen Victoria was molded by newspapers into this type as she appeared in numerous journalistic images interacting with wounded veterans in England. The Queen personally “inspected” the veterans in public rituals at England’s military hospitals: images of these inspections portrayed her less as a queen and more as a wife and mother, her children usually in attendance with her (Fig. 2.25).83 (Queen Victoria, known for her canny publicity moves, deftly aligned herself with popular middle-class sympathy for the veterans, while distancing herself from the reviled generals—even while she also embodied the old class hierarchies that positioned royalty on top.) The ILN pictures of these inspections make the Queen’s gaze mirror that of the newspaper’s readers: we, too, inspect the troops on the page, looking for the signs of their injury. The Queen functions as a stand-in for the British home audience, proffering a sympathetic look as a form of engaged spectatorship. Realism’s ethical function here is channeled through the moral, visual prerogative of Victorian womanhood.

Fig. 2.25 “Her Majesty Inspecting the Wounded Guards in the Grand Hall of Buckingham Palace.” Illustrated London News, March 10, 1855.

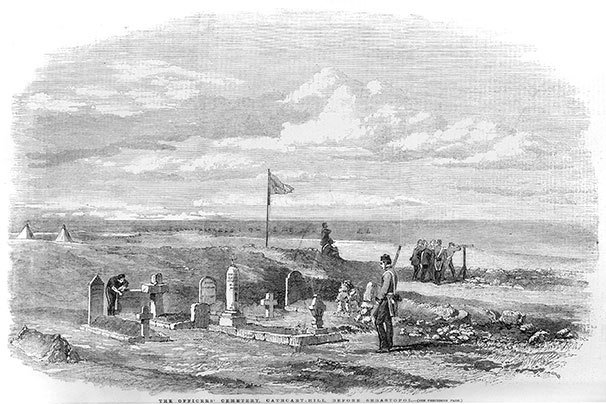

While I have focused on the amputee and the nurse as new, distinctive war types in the 1850s, Crimean reportage innovated or reproduced a range of conventionalized war templates. To mention just one example, the officers’ graveyard on Cathcart hill in the Crimea was always depicted with respectful mourners paying homage, suggesting a form of tasteful grief analogous to modern-day scenes of flag-draped coffins returning home, surrounded by ritualized mourners in uniform (Fig. 2.26). The conventionality of newspaper war scenes expressed a form of political conservatism: even while the newspapers were highly critical of the government, they never criticized the war itself or Britain’s reasons for fighting it. Britain’s imperial project and the dignity of its military adventures remained intact in journalistic critiques. The type of the wounded, suffering, working-class soldier was crucial to Crimean War depictions—as it continues to be today—since it portrayed soldier-protagonists as moral actors rather than brutal killers. The success of this journalistic typing is clear in the outpouring of charitable feeling that the soldiers inspired. Working-class men, who had only recently seemed like dangerous members of Chartist mobs, now became the objects of Victorian philanthropy. When The Times issued a call to readers in October 1854 to support a charitable fund for Crimean soldiers, the paper raised £10,000 over the course of just a few days.84 All of the conventionalism underlying the Crimean newspapers’ realist effects went toward normalizing a war effort—never questioning the class divides between the war’s soldiers and the newspaper’s readers, or the costs of empire, or the waste of life any war entails. War realism worked to bring a new visibility to the suffering of working-class men, even while implicitly justifying the root cause of their harm.

Fig. 2.26 “The Officers’ Cemetery, Cathcart Hill, Before Sebastopol.” Illustrated London News, June 16, 1855.

George Eliot’s Realist War Novel

Visual journalism in the ILN produced its realist effects as part of a broader, multimedia aesthetic that also transformed objects ranging from paintings and novels to newspapers and panoramas. I turn now to study how these effects operated in a text often taken as an exemplary realist novel, George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859). Published just a few years after the war’s end, the novel at first glance seems distant to the worlds of international combat or illustrated journalism, with its pastoral, almost premodern setting in the English countryside. (Surprisingly few novels of the 1850s portrayed the Crimean conflict directly: most of the war’s literary output came in the form of poetry, of which Tennyson’s “Charge” is the most famous example.)85 Yet despite the apparent contrast between Eliot’s pacific English landscape and the wartorn Crimean battlefield, I will show here how both places were represented according to the same, often contradictory realist effects, juxtaposing qualities of the descriptive, the authentic, the plausible, and the mundane. Eliot’s novel evocatively retells the newspapers’ narrative of the Crimean War in miniature, proposing a new, working-class masculine heroism in the face of aristocratic ineptitude and callousness. Many of her techniques and values echo those proposed by the illustrated newspaper, a coherence that testifies to some of realism’s transmedial characteristics in the 1850s. These qualities include the importance of visual modes and metaphors to the realist project; the British investment in humanist ethical frameworks, often figured as a gaze or a look; a turn to the representation of working-class experience; an investigation of taboo, traumatic, or violent subjects offensive to middle-class sensibilities; and an emphasis on ethnography, witnessing, and sincere objectivity. While these elements distinguish a range of nineteenth-century novels, Adam Bede stands as exemplary for its striking, famous manifesto, often anthologized as a definitive statement of the realist aesthetic.