Conclusion

Cinema in 1896

In February 1896, London’s Marlborough Hall hosted the first exhibition of projected film in Britain. A modest audience of journalists, photographers, and artistic folk sat in the darkened hall while the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph projected moving pictures onto a white cloth screen. The films, flickering in black and white, each lasted around forty seconds and showed snippets of life captured by the French inventors—a Lyons street scene; passengers disembarking from a steamer; a train arriving at a station; a child attempting to capture a goldfish in a bowl; a jovial card party; bathers cavorting in the ocean surf. Anna de Brémont, a journalist in the audience, pronounced the effect “startling and sensational”:

[P]ictures are thrown on a screen through the medium of the ‘Cinématographe’ with a realism that baffles description. People move about, enter and disappear, gesticulate, laugh, smoke, eat, drink and perform the most ordinary actions with a fidelity to life that leads one to doubt the evidence of one’s senses.1

Word of mouth quickly made the new entertainment into a popular sensation.

Images in the Victorian picture-world have sometimes been called “pre-cinema” for their technological and tropological contributions to the history of film.2 Yet I want to conclude first by observing, perhaps perversely, how the world of moving pictures differed from the picture worlds considered in this book. My chapters have studied the printed imagery consumed in the Victorian parlor, mediating between public and private realms. These objects all framed fantasy and desire within the bounds of respectable entertainment, suitable for the parlor’s feminized space. Even the advertising poster, emblazoned shamelessly on London streets, also reproduced its likeness in print advertising consumed in the parlor, and limned the rise of the modern private consuming subject, constituted by domestic commodities.

The earliest films, by contrast, evoked not the parlor but the theater, the music hall, and the fairground. In a darkened room shared with strangers, early film spectators purveyed very public thrills. The world of early film was not domestic, appearing instead within a lively, polymorphous realm of mass entertainment. As Michael Chanan points out, early film profits came from selling admission to an experience rather than from marketing a set of objects.3 A poster advertising “Edison’s Life-Sized Animated Pictures” foregrounds the collective spectatorial experience, with fashionable men and women all looking to the screen (Fig. 7.1). Films were shown in venues high and low, from upscale West-End theaters to down-at-the-heels suburban music halls, and from fairgrounds to travelling peep shows. A typical music-hall program presented six- or seven-minute-long films, alternating with feats of juggling or dance, and accompanied by the patter of a lecturing showman.4 Tom Gunning has called the world of early film a “cinema of attractions,” characterizing the pleasurable shock value in scenes of a woman undressing, an acrobat flying, an object magically appearing, or a train rushing headlong toward the viewer. (Gunning framed the concept to rebuke traditional film histories that privileged post-1914 narrative films over so-called “primitive” cinema.)5 The cinema of attractions, says Gunning, offered “a succession of excitements and frustrations whose order cannot be predicated by narrative logic and whose pleasures are never sure of being prolonged.”6 The fleeting shocks of early film, dependent on instantaneous time-forms, differed from the more lingering pleasures of the picture world, whose printed images allowed for lengthy or repeated perusal, even if their ephemeral forms invited eventual disposal.

Fig. 7.1 “Edison’s Life-Size Animated Pictures, China and Boer Wars.” Poster advertising a cinematic show in Curzon Hall, Birmingham. Color lithograph designed by Albert George Morrow, c. 1902. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Having noted these important distinctions, however, the earliest films did also mediate the Victorian picture world in unexpected ways. While modern-day movies typically unspool as seamless visual narratives, early films presented a flickering instability, evidence of their constitution as a series of pictures. The film medium is not merely an expression of pure kinetic motion; it’s also a sequence of images speeded-up into an illusion of continuity. The oscillation between stilled picture and flowing movement was especially clear in early film technologies such as the hand-cranked Mutoscope, invented in 1894, in which the viewer controlled the speed of the images. Crank too slowly, and the illusion would fail; crank too quickly, and the scene would blur by in an instant.7 Étienne-Jules Marey and Edward Muybridge were chronophotographers who studied motion through the still photography of moving bodies—breaking down time into a series of pictures. The earliest film technologies produced an interplay between action and stillness, picture and sequence.8 While scholars have studied the turn of the twentieth century for the birth of new kinds of motions, speeds, blurs, and animations, early film technologies also expressed the stubborn pictorialism of the modern age, insisting on the pause and stillness of the static image.9

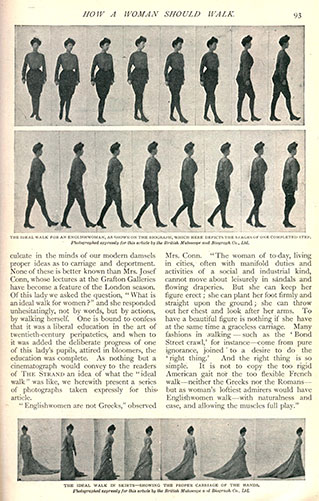

Scholarship on Victorian cinema has contextualized it within a multimedia plenitude, as the 1890s saw the invention of numerous visual gadgets and eye-trickeries. Early films shared continuity with magic shows, magic lantern shows, and mass entertainment illusions.10 The word “cinema” was not used in the 1890s to describe this world; instead, early designations emphasized the medium’s pictorial qualities—in “animated views, animated pictures, moving pictures, pictured scenes, motography, kinematography,” and others.11 The mingling of pictures and film is striking in a 1904 article in The Strand opining on “How a Woman Should Walk.” The article shows the exuberance of the turn-of-the-century illustrated magazine in using photomechanical technology to reproduce multimedia images of women walkers across the centuries.12 Moving from Greek bas-relief sculptures to paintings by Fra Lippo Lippi and Botticelli, proceeding through a Punch cartoon and a Japanese print, the article concludes with an illustration of a woman’s single step “As Shown on the Biograph,” capturing “The Ideal Walk for an Englishwoman” (Fig. 7.2).13 The distinctive film patterning of motion photography here captures a walking woman’s silhouette, streamlined in bloomers. The article integrates the new film technology into a timeline of previous visual media, implicitly proposing the illustrated magazine as an up-to-date accompaniment to the latest developments in fashion, etiquette, and technologized visual culture. The timeline of a woman’s step corresponds with the dizzying progress of media, likening technological change to a liberated vision of an independent woman striding forward in bloomers.

Fig. 7.2 “How a Woman Should Walk.” The Strand Magazine, July 1904.

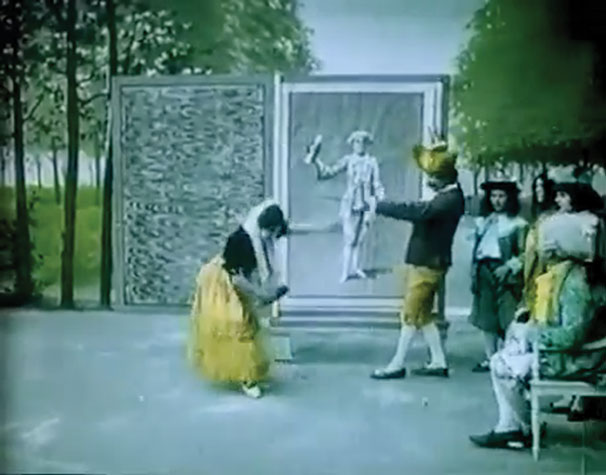

A reciprocity between film and picturing also occurred in early films themselves, in recurring imagery of the nineteenth-century picture world coming magically to life. In A Wonderful Album (Pathé, 1905), a man makes a portrait album grow magically large, then summons the figures into life. His helper tears each page portrait from the album, crumples the paper, and hurls it to the ground; in a puff of smoke, the paper is replaced by the live figure. The animated characters are stock figures of the nineteenth-century imaginary, from courtier and aristocrat to odalisque and Spanish dancer (Fig. 7.3). Like the photographic carte-de-visite album, the desired portraits once again feature prestigious men and erotic women. A cartoon character comes to life in The Enchanted Drawing (Edison, 1900), as a cartoonist interacts with his own creation. The two-dimensional man on the drawing pad grins when the artist bestows upon him a hat and pipe, moving these solid objects from the “real” three-dimensional world into the drawing. Finally, in The Hilarious Posters (Méliès, 1906), a wall of advertising posters comes to life (Fig. 7.4). The figures break out of their frames and engage in general mayhem, grabbing handfuls of the foodstuffs they’re supposed to advertise and throwing them at passersby. Police fail to contain the riot, and the poster characters dance triumphantly out of the frame together. These films realize a fantasy already implicit in various forms of non-cinema picturing, animating a magical world conjured by the sequence of two-dimensional frames or squares.14

Fig. 7.3 L’Album Merveilleux (A Wonderful Album). Pathé, 1905.

Fig. 7.4 Les Affiches en Goguette (The Hilarious Posters). Méliès, 1906.

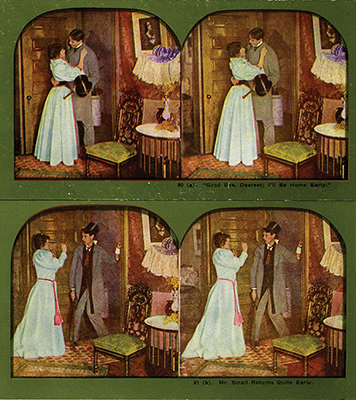

One can trace a surprisingly long-lived tradition of sequential, frame-based visual storytelling back to the eighteenth century and earlier, epitomized by Hogarth’s moralistic progresses.15 The expensive prints, detailing the rise and fall of rake or harlot, appeared in cheap newspaper comic versions in the 1820s. One of the first newspaper comic “strips,” published in Bell’s Comic Annual in 1828, reproduced Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress (1732) as a series of descending squares on a newspaper page, simplified from the lavish originals.16 Square-based visual storytelling implied cause and effect between each frame, one choice leading to the next. The genre proceeded into the stereoscope, where spectators could purchase cards arranged in a narrative series of views, from two, to six, to twelve, or even twenty-four scenes. These comic or melodramatic sets narrated the sequence using captions: in the twelve-card “A Drinker’s Progress,” the middle-class protagonist moves from “First intoxication—bachelors’ carouse” to “Delirium Tremens” to “The Bitter End. Pauper’s Coffin and Lone Watcher,” mourned only by his dog. The actors, props, and elaborate stage sets used to create sequential genre scenes in stereoviews led directly to those used in early comic short films.17 These media of visual storytelling overlapped; at the turn of the twentieth century, spectators could purvey sequenced genre pictorialism in both stereoviews and films. While sequenced visual narratives usually portrayed moralistic stories that policed the behavior of men and women, their pleasures also lay in scenes of debauched excess, picturing intoxication and carnality in ways that broke the disciplining frame. An 1898 two-view stereoscopic sequence depicts a husband promising his wife to return home early; in the second scene, he staggers in unkempt, having returned “quite early”—in the wee morning hours (Fig. 7.5). We are invited to imagine the husband’s naughty behavior between the two frames. Both stereoview and film amplified scenes of carnality with effects that stimulated the body, whether in volumetric illusion or in a fleeting, animated scene.

Fig. 7.5 “‘Good bye, Dearest; I’ll Be Home Early.’” “Mr Small Returns Quite Early.” Two hand-tinted stereographic photographs by T. W. Ingersoll, 1898. Collection of the author.

If the nineteenth-century picture world disseminated a storehouse of mass visual types and tropes, then it is unsurprising that all of the objects studied in this book reappeared in various guises in early films. The cockney rogue-about-town reappeared as the protagonist of the comic strip Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday and star of an 1898 film, an “incorrigible, drunken cockney antihero.”18 Later slapstick comic films featured mock-violent clowns transplanted from the vaudeville stage—eventually incarnated by Charlie Chaplin.19 The illustrated Bible came to life in films of the Passion Plays performed at Oberammergau (in Bavaria) and Horitz (in Bohemia); an 1898 reviewer of a Passion Play film finds himself absorbed in the illusion that “the faces and forms before him are the real people who lived in Palestine 2000 years ago, and with their own eyes witnessed the crucifixion of Christ.”20 Once again, a new visual medium enables the spectator to cross fabulous distances in space and time to achieve a transcendent religious experience. In the arena of news reporting, the illustrated newspaper extended into film with “actualities” (documentary films) shot in warzones like the Boer War and the Spanish–American War.21 The transgressive, photographed woman of the carte-de-visite portrait found her filmic inheritor in the dance films of Loïe Fuller, flickering in the diaphanous fabrics of her famous serpentine dance.22 Following the stereoscope, the dream of virtual travel now extended into the travel film, whose “phantom rides” conveyed the sensation of movement by positioning a camera at the front of a moving train.23 Film, too, revisited the old stations of the picturesque: an 1898 British Biograph film created a phantom ride on the railway passing by Conwy Castle—the Welsh tourist site I studied in Chapter 5 for its multimedia appearance in painting, photography, and stereoscopy (Fig. 7.6). Finally, taking up the work of the advertising poster, the first British film advertisement appeared in 1897: it promoted Dewar’s Scotch Whisky, featuring men in kilts dancing in drunken revelry.

Fig. 7.6 Conway Castle. British Mutoscope and Biograph, 1898. The National Screen and Sound Archive of Wales/Collection Eye Filmmuseum, the Netherlands.

Film is its own distinctive medium. But the long reach of the nineteenth-century picture world expresses itself in both objects and aesthetic ideas, in yearnings for an illusionistic realism, a nostalgic picturesque, a sensational, transgressive female celebrity, a world-building, illustrative Christianity, or a hedonistic, decadent commodity culture. The industrialization of culture that began in the nineteenth century is a process still ongoing today, creating effects both ephemeral and profound.

Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media. Rachel Teukolsky, Oxford University Press (2020). © Rachel Teukolsky.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198859734.001.0001