In the films subsequent to Damnation the basics of the Tarr style do not change, but a certain evolution can be detected in several details. This chapter will discuss this evolutionary process.

The constants are rather obvious. All the films are black and white. Average shot length (ASL) does not go under two minutes, for any of the films, but in two cases it increases by 84 per cent as compared to Damnation. The environment is characterised always by some combination of desolation and poverty (in Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies the same East European environment as in Damnation; in The Man from London and in The Turin Horse a contemporary Mediterranean and nineteenth-century rural environment, respectively). Expressionist lighting, strong black-and-white contrasts and deep-focus staging – in short, film noir visual style – is the dominant visual effect in all of the films. Sounds, noises and music are almost equally important factors of the aesthetic composition of the visual style. On this basis certain aspects become more emphasised in individual films, while others are less salient or even eliminated.

There is even less change in the themes represented. All the stories continue to be based on the situation of entrapment, but from Damnation on these stories will strictly and consistently adhere to a circular structure and be detached from all historical and geographical concreteness. It appears then that stylistic elements change and develop independently of the thematic layer of the films. As shown in this chapter, a certain internal evolution can be traced in the films of this period which, I claim, results in an increasing degree of emotional expressivity in the films. Tarr seems to seek an ever more powerful way to express a feeling of general desperation over the impossibility of changing the situation of human helplessness.

The tendency of increasing average shot length continues with Satantango, but there is not such a dramatic leap between Damnation and Satantango as there is between Almanac of Fall and Damnation. While the increase in the latter case was 108 per cent, between Damnation and Satantango it is only 22 per cent. What is interesting, however, is that within the film itself there is a constant increase in average shot length too. Given that this is a seven-hour-long film broken into three parts, it may be interesting to see how this important stylistic parameter behaves across the parts. What we find is that the first part has slightly shorter shots on average (133) than the second part (137), and the third part has considerably longer shots (166) on average than the second part. This increase in shot length cannot be attributed to dramaturgical factors, since there are no more actions in the first part than in the third part. It is a purely stylistic process, which correlates with a narrative process in the film. As I will show in the next chapter, the narrative structure of Satantango becomes increasingly linear toward the end. Increased continuity and increased linearity together emphasise an unstoppable movement towards an unavoidable collapse.

Camerawork and staging

What we can see on the other hand is that the increase in the shot length did not go together with the same camera style as in Damnation. Rather than intensifying camera movements, Tarr used some extreme long shots that are conspicuously static. The static character of many of these long shots is emphasised through the use of off-screen sound. Characters in these shots talk to other characters off-screen, the camera not letting the off-screen person on-screen during the conversation. In the second shot of the film the on-screen person even turns his back to the camera, so that the viewer cannot really see either one of the two characters having a conversation. At other instances the camera shows characters disappearing in the distance from a stationary position. This is a stylistic solution that does not occur in earlier Tarr films, and especially not in Damnation, where the camera was almost always in motion. However, the idea behind it is the same as that behind the solution so characteristic of Damnation: the movement of the camera is independent from the action that takes place on-screen. Whether the camera is constantly moving or stationary, it is not the movements of the characters that determine its behaviour. In Damnation Tarr used only the dynamic version of this pattern; in Satantango he used both the dynamic and the static versions.

The introduction of static camerawork laid bare the modernist, even avant-garde, stylistic inspirations of this film. The origins of this stylistic pattern can be traced back to the early Bresson films, which inspired Godard, but especially Fassbinder, whose early films abound in long static camera shots and the use of off-screen space. We can also think of the experimental/underground films of Michael Snow. Although both versions of the independent style were widely used during the modernist era – Godard, for example, used both equally – after modernism’s decline the static version became scarce. Only a few directors, such as Abbas Kiarostami and Kitano Takeshi, as well as some other East Asian art filmmakers, continued to use it consistently. However, the other version of this pattern became mainstream during the 1980s, mainly due to its suspense effect. A moving camera that does not follow a character always suggests some unexpected event or scene to be disclosed. Even if no unexpected event occurs, the suspense is always there. That is the reason thrillers and horror films often use this tool. And it became increasingly fashionable as the use of Steadicam and CGI became widespread, since both can produce movements and trajectories that were unimaginable before. Furthermore, the ever-moving camera became a Hollywood mainstream device in the 1990s, although in this case, of course, most of the time it remains close to the characters. Considering all this, one can say that a freely and constantly moving camera has become a widespread stylistic device in a wide range of cinema, from mainstream Hollywood to sophisticated European art films. So, while with Almanac of Fall in 1985 Tarr adopted the artistic version of an increasingly popular mainstream device of world cinema, and in 1987 he spectacularly enriched it with the long-take style, in Satantango, with the long-take static shots, he complemented his stylistic arsenal with the non-mainstream, modernist solution of independent camerawork.

Along with a large number of long tracking and long static shots, there can be found some very traditional devices too, such as quick shot/reverse-shot exchanges in dialogue scenes (such as in the first conversation scene with Futaki and Schmidt, and the interrogation scene at the police station), simple action-following camera movements in many scenes, Jancsóian camera movement and character movement choreographies (such as in the last police station scene). Hence the more balanced stylistic texture in Satantango as compared to Damnation. It even can be said that Tarr uses the same principle of variation regarding different long-take solutions in this film as he does with other solutions across his oeuvre. We can find a large variety of tracking shots and static shots, in all of which the predominant effect is the Godardian and Tarkovskian independence of the camera movements.

A good example is the scene when Futaki packs his belongings to leave the settlement forever. This is a shot that lasts 4 minutes and 32 seconds. It starts by showing Futaki’s empty room. After a while (8 seconds) Futaki comes into the picture without the camera moving. We see him packing, and several times when he leaves the frame the camera does not follow him, just as in the previous example. After 3 minutes and 35 seconds the camera suddenly starts a slow lateral tracking movement to the right, independent of Futaki’s movements, almost leaving him entirely out of the frame. Then Futaki also starts his move to the right, and leaves the room through a back door on the right-hand side. However, the camera does not stop its tracking movement; it keeps on moving to the right for another 49 seconds, showing the empty room again. This is a combined variation of static and moving camerawork, but no matter what, the camerawork is relatively independent from the character’s movement and action.

Another version can be found in the last police station scene. This is a fifteen-minute scene consisting of two shots, each seven and a half minutes long. Both shots consist of two main parts: a static and a circular tracking portion. The distribution of the static and dynamic portions is almost symmetrical. The scene starts with the static portion of the first shot in a given position, which is also where the scene ends in the second shot in the same static position. Between the two static portions both shots contain a circular movement, clockwise in the first shot and counterclockwise in the second. Both circular movements are introduced by a short panning sequence, which seems to follow the characters’ movements, but shortly after this the camera starts a monotonous circular movement unrelated to what the characters do. The only thing that breaks this symmetry is a 1-minute-23-second-long static portion at the end of the first shot. In this scene one can clearly observe to what extent Tarr’s camerawork is structured by systematic variation of stylistic options. This is more visible in Damnation, because there Tarr uses fewer options, but it is still present in Satantango, only with a larger variety of options.

The same can be said with regard to shots in which characters make straight movements, like walking on roads. We have four main methods of representing such movements in this film, and examples abound of all of them. The camera may follow characters from behind (as in the two street-walking scenes featuring Irimiás and Petrina), it may accompany them from the front (as in the scene where the villagers leave their settlement), it may remain stationary, letting the characters disappear into the distance (as in the scene when Irimiás, Petrina and Sanyi walk away on a dirt road, or when Futaki walks away from the train station) or it may show characters approaching its stationary position (as in the scene where Irimiás, Petrina and Sanyika walk in the woods). At one point, one type of shot is even followed by another type. At the end of the first chapter, Futaki and Schmidt are walking away from the stationary camera, and in the first shot of the second chapter the camera follows Irimiás and Petrina walking toward the police station. A fifth version of this shot will be introduced in Werckmeister Harmonies.

This variety of stylistic solutions results in a different sort of mise-en-scène, partly because Tarr makes less use of the immobile-character-frozen-in-his-environment style he experimented with in Damnation. Not that characters do not sometimes remain sitting or standing in one place for a long time, but in most of these cases the camera is stationary too, and does not make movements which would treat characters like objects of the environment. (The main exception is the scene with the characters sleeping and the camera panning around them.) The main examples are the waiting scene at the police station with Irimiás and Petrina, and the first pub scene with Halics.

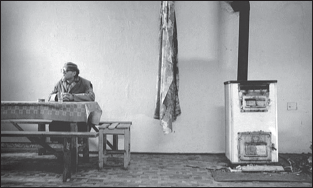

The latter example is particularly interesting. This is a three-and-a-half-minute scene, a very nice long shot composition, in which the human character is part of the symmetrical structure of the graphical composition of the image (figure 24).

Although it may seem that this character has been and will be sitting in this nice picture forever, after three minutes he suddenly leaves the frame for some thirty seconds, during which time we hear him talking off-screen, and then comes back to sit down in the same place for another minute. The camera does not follow him, just shows his empty place for thirty seconds. Although the composition would suggest something like the character’s being ‘rooted’ into the environment, finally it is the character who moves out of the frame, rather than the camera passing by the character and leaving him where he is. This is just the opposite of Damnation’s often used and conspicuous mise-en-scène technique. But this solution is sometimes combined with camera movements in such a way that both the immobility and movement of the camera remain independent from the action on-screen.

Figure 24

As concerns depth of field, Satantango’s staging style is very similar to that of Damnation. There are even fewer flat surface pictures or passages than in the previous film. Two shots of this kind are, however, taken over from Damnation, in a much shorter form: one is the tracking sequence in close-up of the stack of glasses in the pub, and the other is Damnation’s emblematic tracking shot of the wall with openings in which different people stand. There is, however, a great difference between these two tracking shots. In the case of Damnation, the shot does not have any action represented in it, nor is it very specifically embedded in the narrative. In Satantango it represents a particular episode of the plot. Therefore, in the openings in front of which the camera passes along, the action is placed in the background, so there is a rhythmic alteration of the focus between the foreground (the texture of the wall) and the action inside the room. In Damnation everything is composed in the foreground. The tracking starts on a flat surface and ends on a similar flat surface. In Satantango the camera comes out of the room where the action takes place to the exterior of the building, and at the end it re-enters the building, into the space where the action will continue after the camera has moved along the exterior wall. So, this camera movement is less self-contained and isolated from the rest of the narrative than the preceding one in Damnation, and is more motivated by the narrative content of the scene, but, at the same time, with that little modification, it fits into a consistent pattern of the Tarr style. Here again, Tarr starts exploiting the possibilities hidden in a given pattern by making little changes to this pattern.

Environment

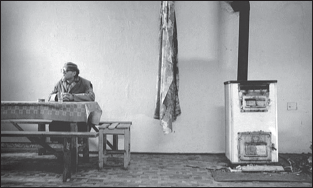

The environment represented in Satantango is similar to that of Damnation, except that it is mainly rural. In this case Tarr did not have to draw together the location of the plot from a dozen pieces found all over the country. He found most of the locations of the settlement as they were in the Hungarian Plain. The extreme poverty and desolation of the apartments, the houses and the yards is very much in line with Damnation’s conception, only everything is in a much worse condition than in Damnation. When we see Futaki’s apartment it is almost impossible to believe that someone is actually living there (figures 25a & b).

Just as in Damnation the settlement that is the main location for the plot does not have any well-known structures. While in Damnation the houses and the streets have a look somewhere between a small town and a village, in Satantango we have a cross between a village and a totally unstructured habitat. There are no roads, only paths, within the settlement, the buildings do not suggest from the outside that people are living there, and there are no community spaces – no church, no shops, no official buildings – in the settlement except for the pub, which in turn has no connection to other buildings; rather it stands alone at some unspecified location.

Just like in Damnation, it is almost always raining outside, and when it is not raining, there is a very strong wind. These will remain the meteorological constants of the Tarr style for the rest of Tarr’s filmmaking career. All of his films in this period are set in the most desolate and unpleasant period of the year, lasting from late autumn to early spring, with bare trees, grey skies and no snow, just wind and cold rain.1 The rain has no symbolic or allegorical meaning in Tarr’s films. It is an expressive element that contributes to the feeling of hopeless misery. Rain is what creates dirt and mud and makes everything disintegrate. And mud is what traps someone where he or she is. Strong wind takes the place of the rain in the last two Tarr films, but in the case of The Turin Horse the wind is not entirely without symbolic meaning, a point to which I will return later on.

Figures 25a–b

Characters

The social place of the characters in Satantango is at least one class lower than that of the characters in Damnation. The social milieu in this film is one of absolute hopeless misery. Damnation’s most spectacular new stylistic device of contrasting moral, psychological, physical and social degradation with poetic and philosophical dialogue, which is also present in this film, could be even more striking than in Damnation, but this is not the case. Tarr uses this tool in a very focused manner, rather than as a general, overall method. While in Damnation all of the main characters at some point had some very abstract, philosophical or poetic lines, in Satantango these kind of lines are spoken mainly by two characters: Irimiás and the captain at the police station. Even though the passages are most of the time surprisingly abstract and poetic, in both cases they are almost completely motivated by the narrative. The same device still has its original stylistic value, but it fits more into the narrative world, which is why the tension between the environment and the dialogue of this kind is, after all, not as striking as in Damnation. There is one important exception to this rule. Around the end of the film Irimiás dictates a letter to the police captain, which we expect to be part of his mission as an undercover agent. When he starts the letter with ‘Dear Mr. Captain…’ the viewer expects to hear some concrete information or report. Instead, the letter continues as follows:

Eternity lasts forever because it doesn’t compare to the ephemeral, the changeable, the temporary. The intensity of light penetrating darkness seems to weaken. There is discontinuance, interruptions, holes, then finally the black nothing. Then there are myriads of stars in an unreachable distance with a tiny spark in the middle, the Ego. Our deeds can be rewarded or punished in eternity, and only there, because everything has a place, far away from reality, where it fits into its place, where it has always been, where it is going to be, where it is now. At its only authentic place.2

This text is totally outside the narrative context, even if one supposes that it is the introduction to Irimiás’s report on the settlers the clerks read and re-edit in a later scene. This text is as radical as the checkroom attendant’s monologues or Karrer’s monologue. All of these texts come from someplace else, a place very different to the place where the speakers are. While in Damnation the main role of these texts is to poke a hole, as it were, in the desolation of the physical universe in order to let some sublime spirituality get through, if only for a second, in Satantango these kind of texts serve also to disgrace this spirituality. The person who says them is a demonic conman who uses his intellectual power only to dupe and abuse everyone.

There is another feature of character representation that is novel in Satantango. Except for one character (the bartender), Damnation’s roles were all played by professional actors, some of whom are well-known stars in Hungarian cinema, some of them less known. In Satantango, out of the nineteen roles of the film ten are played by non-professional actors, and the narrator’s voice is also that of a non-actor. We have to deal here with a new variation. While in the earliest Tarr films non-professional actors improvised their own dialogue, in The Prefab People and in Almanac of Fall professional actors improvised their dialogue, and in Damnation professional actors spoke written literary dialogue, in Satantango mainly non-professional actors speak written, literary dialogue. In this regard also we can note a certain permutation of specific technical elements. In Tarr’s works one can find all the possible variations as regards the professional/non-professional actor and improvisation/literary dialogue elements. All of the variations occur at least twice throughout his oeuvre, which means that Tarr considered all of them valid and viable solutions. This can be summarised in the following table:

One can clearly note the tendency towards the second half of Tarr’s oeuvre to apply the classical combination of professional actors and written dialogues. Improvised dialogues always have some reality effect, even if the dialogue is spoken by professional actors. With Damnation, Tarr went to the opposite extreme: he increased the artificial, poetic, unnatural effect in dialogue. In fact, what happens in Satantango is that Tarr introduces yet another way of maintaining the unnatural, artificial effect of the dialogue. On the one hand, in some scenes, just like in Damnation, Tarr adds abstract content and poetic style to the dialogue. On the other, he makes even the most banal dialogue sound unnatural simply by having non-professional actors speak it. This solution is not without antecedents, even in Tarr’s career. In the beginning of Macbeth the three witches are played by non-professional actors, three well-known theatre and film directors. Since this is not a dominant part of the film, it does not have a salient effect on the style – not to mention that for non-native speakers this fact probably remains imperceptible. (That is why I added parentheses in the above table.) But it is important to note that Tarr, already in 1982, gave this solution a little try.

The most important antecedent of this device is in a Hungarian film from the same year, 1983, made by a friend of Tarr, Gábor Bódy, who tragically passed away in 1985. In his film Dog’s Night Song, Bódy not only cast some of the roles with non-professional actors, but he played the main role himself. The reason why this case was particularly memorable is that Bódy had a way of speaking that was clearly disturbing. His diction was so far away from anything that was permitted by the norms of professional acting that critiques did not even tackle this question, and implicitly attributed this choice to Bódy’s well-known avant-garde inclinations, and to the act of authorial self-reflexivity.3 Bódy, however, had a very precise agenda with that choice. The role he plays is that of a fake priest who deceives people with his charismatic personality. In fact he is an agent of an international secret sect. The question is why he insisted on using his own voice, in spite of his clearly unprofessional diction, which had some speech defects, and risking making his film an object of ridicule. He could have easily dubbed his own voice with a professional actor’s, and his personal appearance would still have had the authorial self-reflection effect. The answer to this is that the strangeness and ‘unprofessionalism’ of his voice calls attention to the fact that someone is awkwardly acting here in a role that was not meant to be played by him. The tone of his voice alone simply says: something stinks here. Using his own voice is a disturbing provocation that prompts everybody to ask why he would do this, for which question obviously nobody could have the correct answer.4

In Satantango the most conspicuous non-professional intonation is that of Irimiás, played by Mihály Víg. Not only has he no formal training in acting, but he has a clearly audible and distinguishable speech defect. Irimiás’s is a similar character to Bódy’s fake priest. He deceives people by playing the role of the saviour, but he is only an undercover police agent. His awkward intonation, together with his speech defect, draws the viewer’s attention to the fact that something is wrong here: he is acting badly, still the others believe him. Everything he says sounds incredibly fake, just because of his intonation, and that is what is the most telling with regard to the other characters’ relation to him.

Tarr denies any conscious allusion to Bódy’s film in his choice of Víg for that role.5 Nor do we have any explicit written or recorded document supporting the hypothesis of a conscious connection. The parallel remains striking, nonetheless. This is the sort of artistic impact that is hard to give a clear and unambiguous explanation for. This solution is clearly not a ‘norm’, not a ‘tradition’, not even a ‘convention’, not least because of the ten years that passed between the two films. A psychoanalytic explanation could quickly come to our rescue, and would easily explain the relationship between the two films; alas, it would hardly rest on historical facts, and will have to remain a light hypothesis forever, as it is very unlikely that we would ever have access to Tarr’s unconscious thoughts of 1991. We can also choose not to bother too much with this fact, since technical solutions or even meanings in culture just spread a bit like diseases, and for an artist it is not necessary to be aware of their origins to be able to use them creatively. But in this particular case we do not even need some kind of contagion theory to explain an impact where direct causal connection cannot be established, because some connection in fact can be established, and the thing to be explained should be the process by which this connection led Tarr to use this solution. We have to find a more fact-based hypothesis than a psychoanalytical one as to why Tarr did this. We need a hypothesis that not only rests on the striking similarity, but fits into the evolutionary pattern of Tarr’s career too, and goes beyond Tarr’s own explanation, which is that this similarity is due to pure coincidence. There are too many cinematographic and biographical links to accept this as a coincidence. My claim is that Tarr made an avant-garde gesture that was in currency ten years earlier, and the reason why he did it was that he considered his films as in a way continuing this avant-garde movement.

Tarr’s taste for Hungarian avant-garde art can be clearly detected in some traces in his films and biographical data. For many years in the early 1970s, Tarr was close to Hungary’s most virulent underground or avant-garde theatre groups, the Orfeo theatre and the Halász theatre. These groups not only covered theatrical activities, but represented a whole way of life and attracted all kinds of avant-garde artists, and many young people like Tarr, who just wanted to be around them. Tarr was immersed in that culture without actively taking part in their creative activities. Damnation and Satantango abound in hidden and direct references to Hungarian avant-garde art of the 1970s and 1980s. I mentioned the most salient example that can be found in Damnation (direct citation of an avant-garde film of the 1970s) in the previous chapter. In Satantango, avant-garde references are even more hidden but unmistakable for someone who knows this subculture. More than one-third, precisely seven, of the main characters of Satantango come from this particular subculture, only one of whom is a professional actor, Miklós Székely B., playing Futaki. Other than Mihály Víg, we find the following avant-garde artists in the film: Schmidt is played by a well-known avant-garde painter and musician of the 1970s and 1980s, László feLugossy; Halics is played by someone close to this circle at this time, Alfréd Járai; Petrina is played by an avant-garde filmmaker of the early 1980s, Dr Putyi Horváth; Gyula Pauer, well known for his ‘pseudo art’ of the 1970s and 1980s, also has a supporting role in Satantango; and finally, the captain of the police is played by a famous writer, close friend and collaborator of Gábor Bódy, Péter Dobay. This is more than coincidence. As for the concrete similarity between Satantango and Bódy’s film, we should note that Tarr knew Bódy and his film well, and they respected each other’s work in spite of the fact that at that time they did not belong to the same artistic current: Bódy was a sort of avant-garde icon at the beginning of the 1980s, while Tarr was slowly moving away from the opposite camp to where he was considered to belong, the semi-documentary practice. However, Tarr was the one in this camp whom Bódy respected the most, and he called the early version of The Outsider an ‘experimental film’, which certainly counted as a compliment from Bódy at that time.6 In these films (Damnation and Satantango) Tarr consistently pays tribute to the avant-garde spirit of a historical period which he himself did not play a role in forming; yet its influence is detectable in his films ten years later. And because this influence is really detectable, the references are more than just paying tribute. Tarr shares the impulse with the avant-garde of the 1970s and early 1980s to consciously corrupt a professional filmmaking practice by moving stylistic elements out of their usual contexts and using extreme or absurd effects to make the work more expressive. This is the same avant-garde spirit that ten or fifteen years earlier informed Gábor Bódy’s films, as well as the artistic creations of the artists who appear in his films. The idea to make a professional film look non-professional was an avant-garde idea of the early 1980s in Hungarian cinema practised most consistently by Bódy. Tarr used this conspicuously amateurish acting as one stylistic element among others, but it was an important ingredient of his film, given his intention to demarcate it from the rest of Hungarian cinema, much as the same solution was important to Bódy’s intentions ten years before. So, even if it might be true that Tarr did not specifically have Bódy in mind when making that choice, the fact that his attitude and way of thinking was informed by the avant-garde make this choice more than a coincidence. To explain it, it is enough to know that this solution had an avant-garde currency ten years earlier, and that Tarr consistently wanted to make explicit his relationship to this period. In his own way Tarr kept alive (or revived) this avant-garde. Finally one must remark that Bódy’s film and Krasznahorkai’s novel were born in the same historical period, in the first couple of years of the 1980s, which makes both works’ main character – the ideological, quasi-religious conman, who is in reality the agent of a secret organisation, and whose fakeness is nevertheless apparent and ridiculous – a topical character of the period.

Werckmeister Harmonies

This film also represents some less conspicuous stylistic changes as compared to Tarr’s previous works, which are important nevertheless. The first change to remark on is a quantitative one. As mentioned earlier, the average shot length of this film is longer by 51 per cent than that of Satantango. This is the second biggest increase of average shot length in Tarr’s career. The longest take in the film is the first one, which is 9 minutes and 36 seconds long, and no take is shorter than 45 seconds. This quantitative increase of shot length alone, however, would not entail any significant stylistic change. What it means is that after the success of Satantango Tarr has become more self-confident in exploring more possibilities of the stylistic patterns of the long take.

What is remarkable in this film is a change in the historical model of long-take style. Instead of further developing the Godard-Tarkovsky kind of independent camerawork, Tarr shifted to the Antonioni-Jancsó model of accompanying complicated character movements. In this film we find no long camera movements travelling around spaces or among characters independently of the characters’ movements. Nor do we find long static shots in which the characters just walk in and out without the camera turning to follow their movements. Every movement of the camera is motivated by character motion, and even if sometimes a character goes out of sight for a moment, the camera catches up quickly with his or her trajectory.

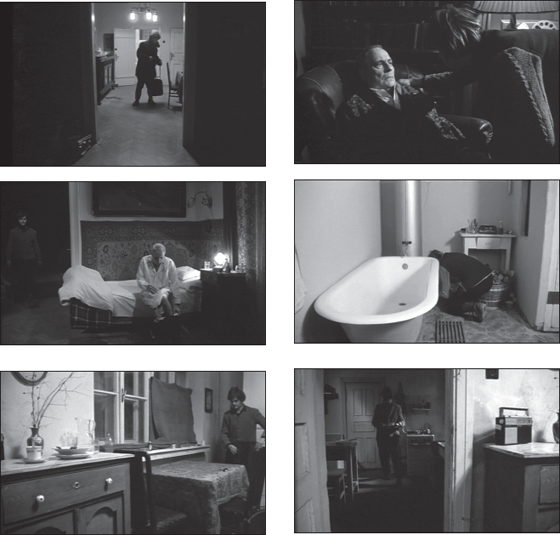

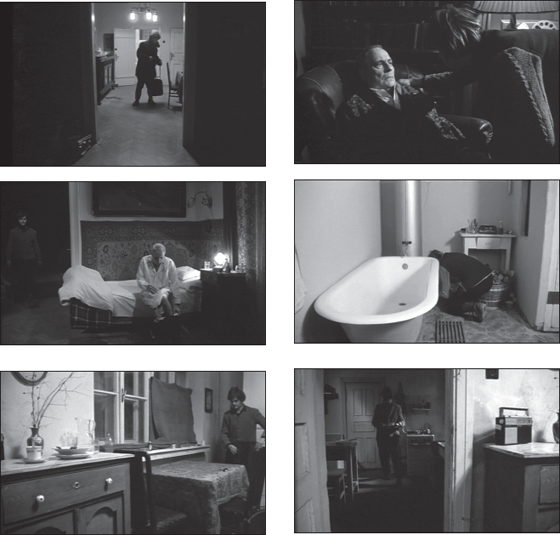

Extended long takes that follow characters result in even more complicated camera movement choreography than that found in Satantango or in Damnation. This is especially true when the characters move through different spaces. In the film’s third shot we follow Valuska’s movement for seven minutes as he enters Mr. Eszter’s house, helps him to bed, and then makes some arrangements in the apartment before leaving. Topographically this is a simple circle, as the apartment’s arrangement is such that proceeding from one room to another finally makes a circle. But the different closing ins and backing ups, stops, turns and pans needed to follow Valuska make this choreography very complex. This complexity, however, is quite easy to follow. This is due to the fact that the shot is composed as if it were a sequence of seven static shots (figures 26a–g). Whenever Valuska has to do something in the apartment the camera stops on a well-composed image. These stops can last as long as a minute. During these stops the camera does not move, or moves just a very small amount when Valuska moves away from the camera or even leaves the frame. Between these stops the transitions include turns, back ups and closing ins. All this provides the camera movement with a certain rhythmic ‘breathing’ that prevents a too-mechanical following technique that would pass unnoticed and could have been easily replaced by simple editing. The camera movement is fundamentally subordinated to the character’s movement, yet it is autonomous enough to provide through its own tempo and micro-movements an emotional accent to the scene.

Figures 26a–f

Figure 26g

Two more scenes are composed in this manner. One is the hospital scene, and the other is the night scene at the main square. In both of them we can find relatively autonomous camerawork, which is nevertheless fundamentally motivated by character movements. This hospital scene is a single eight-minute-long take with a constant forward movement. In it, the mob proceeds from ward to ward, systematically destroying the whole institution. The characters run in and out of the picture and the camera moves forward down the corridor much slower than them, following them into the wards and the corridor. The camera movement is entirely motivated by the characters’ movements, only it follows them at a different speed. Interestingly, in the last part of the shot, where the mob stops the destruction and starts leaving the hospital, they do it at the same speed as the camera has moved all along. So, one could say that the speed of the camera movement in the first part of the scene is anticipatory, as it were, as regards the characters’ movement in the second part of the scene – as if the camera just ‘knew’ that finally they would slow down. The other example is the second main square scene, where Valuska is wandering around among the mob. The camera follows his trajectory in such a way that it ‘loses’ him from time to time, moving forward, and ‘meets’ him again. The basic movement pattern is motivated by Valuska’s movement, but the camera still has a considerable autonomy.

This latter scene is interesting from yet another point of view. As mentioned earlier, in Satantango Tarr did not use camera movements travelling around in spaces among or in front of ‘frozen’ characters, which was the characteristic camera movement in Damnation. This kind of camera movement returns in Werckmeister Harmonies with an important variation, inasmuch as this pattern is not combined with the total independence of the camera. There are two scenes in which the camera moves around at length among immobile characters. Both take place in the main square of the small town where the whale is on display. The mob gathers in that square, doing nothing but just standing in little groups. The first is a five-minute shot; the second is a three-minute shot. In both, the camera wanders around among the characters, who barely move and sometimes even seem frozen. The big difference between these two shots on the one hand and Damnation’s similar shots on the other is that here the camera does not move independently but follows Valuska walking around among the people in the square. The two shots can even each be considered further variations in their own right. In the first shot the camera remains strictly attached to Valuska’s movements all the way. In the second, which is in the night scene, the camera is periodically detached from Valuska’s track, losing and joining him several times.

Figure 27

Once again, we can detect in this the variation principle, by which a stylistic solution from one film returns in another in a slightly different context and combination. Some combinations remain ephemeral; some become so successful as to crystallise into a pattern. This is what happened in this film with a special variation of camera movement that follows moving characters. In Satantango different variations of this movement can be found, but the main solution is that the camera proceeds either in front of the characters or follows them from behind. These are not particularly innovative solutions; they may become memorable owing to their other characteristics, such as their length or their other visual or acoustic elements, for example the strong wind blowing waste from behind in the scene where Irimiás and Petrina are walking toward the police station. In Werckmeister Harmonies Tarr introduced another variation on following walking characters at length. In a scene we can see Mr. Eszter and Valuska walking on the street side by side, and the camera follows them, showing their profiles in medium close-up (figure 27).

This scene lasts two minutes and thirty seconds, within the shot. During this two and a half minutes the two characters talk only for thirty seconds; during the rest of the time they remain silent. All we can hear for two minutes is the rhythmic sound of their coordinated steps on the pavement. This solution – in this shot, of that length, with this rhythmic design – was made emblematic by another director, Gus Van Sant, who replicated the same combination of stylistic parameters in his film Gerry, in which he pays tribute to Béla Tarr.

Deep-focus compositions have been an important characteristic of the Tarr style ever since Damnation. Contrast, even tension, between foreground and background was systematically used by Tarr to increase the dramatic power of the images. This can be detected also in staging style. One can discern a clear shift in Tarr’s films from horizontal staging toward in-depth staging. We need only compare ensemble pictures typical for almost all Tarr films from Almanac of Fall (figure 28) and Satantango (figure 29).

Figure 28

In this picture the characters are lined up in a row around Hédi in the middle. Even though two characters stand behind Hédi, they are close to her and there is no background anyway, so basically, the composition is horizontal, as if the five characters were standing in a straight line. This composition is radicalised in Damnation by a lateral tracking shot passing along the lined-up characters (see previous chapter, figures 22a–g). A similar ensemble picture in Satantango by contrast looks like figure 29. The characters line up in a curve. This picture is made with a wide-angle lens – which can be seen in the distortion of the two front most characters – so as to provide a great depth of field. In Werckmeister Harmonies extreme deep space compositions occur very often, and are emphasised by lighting effects (figure 30).

Figure 29

Figure 30

Sometimes Tarr not only stages deep-focus compositions which are static with characters moving in and out of the frame, but he enhances the dramatic tension through the revealing camera movement. A good example is the scene in which Valuska brings Aunt Tünde’s luggage to Mr. Eszter’s home. Not only is there a tension between the foreground with the luggage, but the camera makes a revealing movement to increase this tension (figures 31a–c). In fact this is a three-stage movement. In the first stage we can see Mr. Eszter in the background. After a while the camera makes a slight movement to the right to reveal Valuska’s presence in the room. But this movement is just an indication; Tarr does not show Valuska’s entire figure – it is just enough for the viewer to see that he is still there, and did not leave the room when he left the frame. The main camera movement is the last one, as the camera is suddenly lowered to reveal the presence of the luggage, thus creating a high tension between the object in the foreground and stunned Mr. Eszter in the background. This is not really a revealing movement, since we know that the luggage is there, although we have not seen it before this change of camera position. This is a very classical visual emphasis to increase dramatic tension.

Figures 31a–c

Figures 32a & b

The second example can be found at the end of the hospital ravaging scene. In this case the camera movement truly reveals something stunning: an old man’s naked body in the background. The revealing gesture is closely related to the above-mentioned characteristic of the camera movement of this scene. As already described, the camera moves slower than the mob. Most of the time the camera enters a ward only when the destruction of the furniture and beating up of the patients are already underway or are finished in that particular ward and are to be continued in the next one. Arriving in the last ward, the camera slowly moves around in it; meanwhile two characters cross the scene, and stop at an opening covered with a shower curtain. With a coordinated brutal gesture they strip down the curtain and freeze. That is when the camera arrives there slowly and turns to reveal what they see in the background (figures 32a & b). The dramatic tension is not carried solely by the depth-of-space composition; the revealing gesture of the camera movement increases this effect considerably.

Werckmeister Harmonies represents a classical turn in the evolution of the Tarr style. A lot of effects relating this style to modernism or even to the avant-garde disappear: juxtaposition or mixing contrasting elements, independent camera movement, references to or citations from avant-garde art, sharp contrast between the characters’ social position and their poetic or philosophical dialogue. After Satantango the linear chronology of the narrative returns, and the narration is focused on one character.

The Man from London

This film is based stylistically on the changes carried out in Werckmeister Harmonies. There is no return to the modernist solutions of Satantango or Damnation. On the contrary, if there is any stylistic development in this film, it is toward a more purist, crystallised form of the Tarr style.

In Werckmeister Harmonies strong black-and-white contrast compositions were dominant, but in The Man from London, with geometric minimalism added, these compositions become really classical, having strong film historical associations. Even if Tarr is reluctant to admit conscious references to film history, Bresson, Fassbinder, Carné and some film noir directors obviously come to mind. There are also shots in which the minimalist aesthetic of the composition dominates any other effect of the image (figures 33 & 34). There are even compositions where the complicated structure of mirrored images of Almanac of Fall returns in a more minimalist form (figure 35).

Figures 33 & 34

Strong lighting effects all over the film evoke the expressionist and film noir visual aesthetic in its most elaborate form (figure 36). More than in any previous film, black-and-white contrast creates a strong graphical effect, rendering some compositions painterly rather than realistic (figure 37).

Figures 35 & 36

The Man from London is Tarr’s first film in which the environment carries no traces of contemporary East European landscape. This is immediately clear for an East European viewer, maybe less obvious for a West European viewer, and probably unnoticeable for a non-European viewer. Differences are very small between this film’s constructed environment and that of Werckmeister Harmonies. Both are located in a traditional half-urban, rather old-fashioned small-town world of deserted streets with houses with run-down exteriors and poorly furnished interiors. Furniture items are rather eclectic, ranging from cheap shabby articles to items of modern technology. For example in The Man from London most of the props date from the early to mid-twentieth century, but the cashier machine in the fur shop and the freezer in the shop where Henriette works indicate the late 1990s or even the early 2000s. Compared to these items the rest look to indicate poverty rather than a different historical period.

Figures 37 & 38

This is the first film in Tarr’s career where the representation of the environment conveys positive feelings, at least to some extent. There are long shots of the town where the beauty of the location overshadows the general shabbiness of the individual buildings (figure 38).

One can even find direct reference to the history of photography. In the scene where Maloin and his daughter have a drink before they go out to the fur shop we can see two dancing characters, one of whom holds a chair in his hands above his head, the other of whom balances a snooker ball on his forehead (figure 39). This scene was inspired by a photograph by the French photographer Robert Doisneau, while the idea of the woman playing the accordion came from another Doisneau picture.

Figure 39

All of this suggests that in The Man from London Tarr, while maintaining the main aspects of the Tarr style, connects it to various cinematic or extra-cinematic historical visual models. This is what we might call the classicisation of the Tarr style. While Damnation is full of aesthetic distance and avant-garde references, Satantango is full of irony, Werckmeister Harmonies lacks aesthetic distance in the avant-garde sense almost entirely and includes minimal irony (basically limited to the scene of the hotel porter’s lunch and the police commander’s drunken babble), cultural references in The Man from London are changed from avant-garde to classical modernism (Bresson, Fassbinder, film noir), and the only scene in which there is some aesthetic distance is the bar dance with the snooker ball and the chair.

There are some other minor but important stylistic changes too. The most spectacular change is the radical reduction of dialogue. Not only is there no tension any more between the characters’ low social status and the poetic text they recite, but most characters do not even say a word in the film. Most importantly, the protagonist, Maloin, has very few dialogue scenes, and even in dialogue situations he prefers to keep silent. Verbal communication is extremely reduced in this film as compared to the previous Tarr films. This is even more striking if one takes into account that in more than one scene personal conflicts could be normally resolved if Maloin explained his situation or gave some more information. Lack of communication becomes in several instances the cause of conflicts and even of tragedies. When Maloin visits Brown in the shack, to bring him food, the result of this visit is a tragedy, as Brown thinks that Maloin came to give him up to the police. This is explicit in the novel, and implicit in the film. Tarr arranged this scene so that nobody would really know what happened until later, when Maloin tells the investigator that he killed Brown. Only when the investigator specifies that this was in self-defence can we construct the most likely chain of events. It is only then that the viewer may conclude that if the two of them had talked, Brown would not have had to die. In no other Tarr film is lack of communication the cause of a tragedy. Misunderstanding and violent and deceptive communication can often be found in the earlier Tarr films. Silence and a communication gap are something new.

The Turin Horse

The fact that this film was announced by its author as the last Béla Tarr film must turn the critic’s attention to, among other things, the question of whether or not this film is different from the previous ones, whether it is a conclusion in any way, or a repetition or closure. In other words, since it stands out as an intended closure of a series of works, does this fact show in one way or another?

In different aspects of the style we can see different characteristics. As for the spatial aspect, this film goes back to the first-period Tarr films: a strictly circumscribed narrow space that the characters almost never leave. Apartments became psychological traps for characters in at least three early films: Family Nest, The Prefab People and Almanac of Fall. In The Turin Horse the characters are physically trapped in a house, which they can leave only for short periods, and even then they cannot go further than a few hundred metres. The conflict in this film is due not to communication problems, as in the early Tarr films, but to the mere fact that they cannot leave the property because of the weather conditions and the illness of the horse. So, for the first time, the physical situation is not an occasion to develop the main theme of the trap of personal conflicts, but becomes the main issue as a result of natural forces.

The trap situation known from the early Tarr films is coupled in this film with a new expression of an important element of every Tarr film: the dialogue. Until The Man from London Tarr moved between two extreme approaches: entirely improvised dialogue and abstract or poetic written dialogue. In The Man from London Tarr does not take either approach; instead, he incorporates a hitherto unusual value: a radical reduction in dialogue. This is the film in which the characters say only very short and concise sentences, and much of the dramatic tension and conflict of the film is a result of what they do not say, or of the fact that they do not say anything.

This value is developed to an extreme in The Turin Horse. The characters’ verbal exchanges are reduced to simple words or short sentences that they utter very seldom, and which refer to the immediate context, such as orders to do this or that, or are simple remarks about the immediate environment. With one exception there are no long tirades, no discussions, no verbal developments of states of mind, no reactions to what others do.7 The two last films brought a new phenomenon into the series of Tarr films, which were hitherto rather talkative. The gradual suppression of dialogue contributes to a certain dramatic tension created by the increased visual expressivity of the images.

Not unrelated to this effect is the considerable increase in the importance of music and other noises in this film. Repetitive music, the constant roar of the wind and several other sounds accompany the images, creating a more lugubrious atmosphere than in any preceding Tarr film. Clearly, this music/noise ‘symphony’ takes the place of dialogue in The Turin Horse, which is a very different effect to the verbal minimalism we find in the late Bresson films or in early Jancsó films. Far from being a minimalist reduction, the lack of dialogue is a means of increasing emotional expressivity, ceding space to musical compositions. In fact, that is the form the evolution of expressivity took in the Tarr style. Visually, we find no more expressionist compositions than in The Man from London; on the contrary, lighting is most of the time rather balanced, especially in outdoor takes. Also, there are only a very few abstract compositions, and the black-and-white contrast does not shape the space as in Werckmeister Harmonies or in The Man from London. Lighting becomes a central effect only in the last couple of minutes of the film, when, according to the story, all light is gone, and the scenes take place in almost complete darkness. This is where the viewer can experience the incredible sophistication of Tarr’s lighting technique. There is no complete darkness preventing us from seeing anything; there is just enough light to make the characters look like light-grey shadows in the grey darkness.

In this film Tarr, remarkably, returned to static camerawork and reached the longest average shot length of his career. He almost entirely got rid of independent camera movements, the camera mostly following the characters’ trajectories, many times turning around them. Most of the time the characters stay in a small indoor space, which is the only room of a house. There are no complex structures as in Werckmeister Harmonies, no long distances between multiple locations as in Satantango, not even multiple rooms as in Almanac of Fall. This is why increasing shot length was a real technical challenge in this film. This explains the extended use of Steadicam, which allows small and fine movements even in narrow spaces, and over short distances.

Evolutionary processes in the Tarr style

Length of take

One can rarely find consistent stylistic tendencies overarching the whole active period of a filmmaker’s career. Usually we can distinguish between different ‘periods’ having constant features, which either disappear or reappear or alternate. Very often different periods have no relationship to one another at all, making the career stylistically eclectic. Very few directors work in such a way that they chisel some stylistic parameters throughout a whole career, experimenting with them by trying them out in different combinations. Ozu, Dreyer and probably Eisenstein come to mind in this respect. There are a certain number of preeminent stylistic parameters that each Tarr film is based upon, using different values and in different combinations. Examples include the long take, mobile camerawork, unconventional use of dialogue, and depth of space. These parameters determine considerably all of Tarr’s films, obviously together with other changing parameters, like visual expressivity, sound design and acting style, the changes in which are not always preeminent in all the films.

Chart 1. Average shot lengths in Tarr’s films (excluding Macbeth)

One of the parameters, the length of take, shows a remarkable pattern in Tarr’s career. As shown in chart 1 opposite, we can identify a constant and almost monotonous increase in shot lengths in Tarr’s films. Discounting Macbeth, which is a film made of two takes, but was not a movie release, each film has a higher ASL than the previous one. Only in two cases do we find an ASL equal to that of the previous film: The Outsider has basically the same rate as Family Nest, and The Man from London has the same rate as Werckmeister Harmonies. But there are no drop-offs: the constant increase in length of take is the rule in Béla Tarr’s career. It is also remarkable that the same tendency can be discovered within Satantango, which is a film made over two years and with a length of five normal-length feature films. The takes in part three are 30 per cent longer than in part one, on average.

The nature of this increase tells us that Tarr is not simply a director who likes long takes and does not vary the length of his takes according to the needs of a particular narrative. If this were the case, either ASL would be about the same everywhere or there would be an irregular variation in the curve. What we see instead is a constant and considerable increase over 34 years. And not a slight increase either: the shots in The Turin Horse are almost eight times longer on average than those in Family Nest. The only question is to what extent ASL increases from one film to another, not whether it does.

This chart does not visualise well the incredible shift between Almanac of Fall and Damnation with respect to shot length. Analysis of the rate at which average shot length changed from one film to another provides an interesting perspective on the problem of the periods in Tarr’s career. The change rate of average shot length from one film to another spectacularly demonstrates a huge jump after Almanac of Fall (chart 2).

Chart 2. Rate of increase of ASL

The first thing that we can say is that there are no negative values; that is, there is no decrease in ASL in consecutive films. The other thing to remark on is the spectacular change with Damnation. In this film the increase in ASL surpassed 200 per cent as compared to the previous film, after which the increase continued at about the same rate as before, only at a much higher level.

This steady tendency of increasing shot length looks like a conscious and independent factor of Tarr’s films in the sense that it does not depend on any other feature of the film. Whatever other parameters change or remain the same from one film to another, ASL will be bigger than in the previous films, and Damnation was with no doubt a turning point.

Tarr definitely did not have a plan according to which, in each subsequent film, takes should be longer than in the previous one, nor has he been aware that this pattern exists. But increasing shot length is what he has been doing, with remarkable consistency. In a way this was a conscious process, in the sense that throughout his filmmaking career the problem of shot length has remained prevalent, and each film was in a way a new experiment in exploiting the possibilities of the length of takes. This is the most important medium for Tarr for communicating an atmosphere or a feeling in his films, and its constant increase shows that it is this communication process that Tarr wants to make more effective in each subsequent film.

To understand what is communicated through this process, it is essential to see whether there is any other stylistic process that changes together with the increase of the length of the takes. This is how we can get closer to the unique combination of stylistic features which supports a unique artistic expression on the one hand, and explains the trajectory of the evolution of the Tarr oeuvre on the other.

Indeed, we can find two other important features that change together with the length of takes throughout Tarr’s career. One is the rate of moving camera in the films, and the other is the expressiveness of the visual compositions.

Moving camera

As discussed earlier, long-take styles may come with either predominantly static or predominantly dynamic camerawork. In the Tarr style one can find all the four basic models of the long-take style. We find static long-take compositions especially in Almanac of Fall, Satantango and The Turin Horse. In the other films extreme static long takes are not typical. Camera movements are mostly of the complicated character-following Jancsó type, but especially in the films preceding The Man from London, independent camera movements are very frequent. Both the alienating Godard kind and the immersing Tarkovsky kind occur in Tarr’s films. This flexibility is made possible by the use of the Steadicam in the 1990s, starting from Satantango. The Steadicam makes it possible to follow a character’s movements through different height levels and different spaces, to turn around the character, to change angles without the limitations of the traditional dolly. Movements can be less geometrical, and the distance between the camera and the characters can be very flexible. The liberty of Jancsó’s camerawork was made possible mainly by the minimalism of the set: bare and empty spaces with very few physical limitations. This is why the scenes in a Jancsó film very rarely take place in closed places like a room. With the help of the Steadicam Tarr could achieve the same flexibility in his camerawork, even in small, closed spaces.

Moving camera has been a natural element in Tarr’s films from all periods. Extended camera movements appeared with the spectacular increase in length of takes. One can observe a similar tendency in the use of moving camera to that in the use of long takes, as illustrated by chart 3. On the vertical axis we find the percentage of moving camera in a given film. One thing we can say is that in the beginning of Tarr’s career the rate of moving camera did not exceed 30 per cent. It was even around 2 per cent in Family Nest. In other words in the case of this film the camera is static 98 per cent of the time, and in the case of The Outsider, 70 per cent of the time. This rate is exactly the inverse 28 years later: in The Man from London, the camera is moving more than 70 per cent of the time, a rate that no Tarr film had reached before. Another thing we can say is that the use of a moving camera constantly increases, a pattern broken only by a marginally higher percentage of static camerawork in Satantango, which led to this result. And in this respect too, we can note a jump between Almanac of Fall and Damnation.

Chart 3. The rate of moving camera in the Tarr films

One could say that long takes and moving camera go together, so the longer the takes, the more mobile the camera in general. In fact, there is a clear tendency for long-take-style films to also use more camera motion, but this is not a rule. We find many examples to the contrary, and we do not even have to cite well-known underground films like those of Andy Warhol. For example, Taiwanese director Edward Yang’s almost three-hour-long Yi Yi (2000) abounds in seventy- to ninety-second-long, absolutely static shots. On the other hand, we find very many films with excessively short takes, and, at the same time, with a high moving-camera rate. For example, in a mainstream Hollywood movie, made approximately at the same time as The Man from London, Spike Lee’s The Inside Man (2006), we find an average shot length of around five seconds, that is, forty times shorter than in Tarr’s film, but the film still has exactly the same rate (70 per cent) of moving camera. Moving camera is clearly not linked to long takes. And even if the opposite is true less frequently, long takes may well be coupled with static camerawork. And Tarr’s career is the best proof of this. In his last film, which has the highest average shot length in his career, the rate of moving camera, which has increased constantly during the past thirty years, suddenly drops back to the level of 1980, that is, to around 30 per cent. This film is as static in its camerawork as films made at the very beginning of his career and consists of longer takes on average than any of the previous Tarr films. We will see that Tarr returns in his last film to the beginning of his career in other respects too. Long takes and moving camera are clearly independent stylistic patterns. And we see that both parameters have a tendency to increase over the years in Tarr’s films, and both of them increase suddenly a great deal between Almanac of Fall and Damnation.

Expressivity

The third relatively consistent tendency in Tarr’s films is the growth of expressivity of the visual compositions, which obviously cannot be linked to the increase in ASL or the rate of moving camera. Expressivity is not something that can be quantified, but it is not a merely subjective aesthetic effect either. Expressivity in film history has been a recognisable stylistic norm since the 1920s. German expressionism, Eisenstein, Orson Welles and finally film noir have shaped the basic forms films have used ever since to create a fearful, emotionally saturated, grim, mysterious or dangerously unrealistic atmosphere. We can detect a tendency in Tarr’s work not only towards the increased use of expressive visual effects but also towards incorporating compositions reminiscent of historical examples of visual expressivity.

Expressive visual stylisation appeared for the first time in Tarr’s oeuvre in Almanac of Fall. Unnatural, colourful lighting and extreme camera angles carry this effect in this film (see chapter 2, figures 7c & d, and figures 8–10). As mentioned earlier, this kind of excessive expressivity was fashionable for a certain period at the turn of the 1980s, but not so much by the end of the decade. Tarr retained the expressive quality of his images but returned to a more traditional form of cinematic expressionism: the strong black-and-white contrast compositions, and strong lighting effects. Many of the more memorable shots of Damnation are composed this way (see chapter 3, figures 15a–c, 18a–c and 21c). Deep-focus compositions were not more prevalent in Damnation than in Almanac of Fall or even than in The Outsider. In Satantango, by contrast, deep-focus staging is much more prevalent (figure 40), and at some instances it is coupled with strong black-and-white contrast and wet surfaces, which moved the Tarr style toward classical film noir stylisation.

Figure 40

It is, however, in Werckmeister Harmonies where this combination becomes the main stylistic effect of the form. This film abounds in sharp black-and-white contrast, high-tension deep-focus compositions (figures 30 and 31c). In many images in this film, lighting becomes the most important compositional tool. In The Man from London this tendency is maintained and complemented by some utterly abstract or painterly images (figures 33 & 37) or by compositions reminiscent of film historical references (figure 36). Not only does the expressivity of the visual aspect of Tarr films increase, but together with this increase the self-conscious film historical positioning of this visual world appears.

Conclusion

The longitudinal comparative and quantitative analysis of the formal aspects of Béla Tarr’s films provides us with some interesting insights regarding the course these films have traced during the past thirty-five years. We can safely assert that in many respects there are two stylistic periods in Tarr’s career. However, the main elements of the ‘second period’ Tarr style are present in the early films with different prevalence, in different combinations and with different values. The only feature that was missing from the first three films and was added by Almanac of Fall was visual expressivity. This feature is combined with the most characteristic feature of the early films: improvised acting style and dialogue. This latter disappeared entirely from the later films, and visual expressivity became prominent. We found two quantifiable parallel tendencies of increasing devices: average shot length and camera mobility. These tendencies are remarkably consistent throughout the whole corpus. Together with visual expressivity we have three dominant features of constantly growing prominence in Béla Tarr’s films until the last film, where two of them suddenly drop back to the level of the early films. This fact can only be seen as the manifestation of some wish by the author to create a kind of stylistic synthesis in his last film. But until this last film these factors increased together. As argued earlier, none of these characteristics could be viewed as a necessary consequence of any other, which is clearly shown by the fact that in the last film they are separated. This means that not only do we have a particular stylistic combination of three important visual and temporal elements, but all of the three elements become increasingly important in Tarr’s career, a fact that needs to be explained. Why has Tarr continuously increased the values of these parameters in his films, until The Man from London, while freely applying or abandoning others, like independent camera movement, improvised and poetic dialogues, and colour film stock?

This question cannot be answered on a stylistic level. If there are no strict rules or conventions for a given form, there are no stylistic reasons for a given stylistic combination either. Justification of a given set of stylistic features can be provided either through a historical explanation or through reference to the aesthetic or psychological effect it has on viewers. Historical explanations consist of listing the cultural traditions an author can be associated with, the explanation being that a given author uses a set of solutions because those solutions are like cultural traditions for him or her. But this kind of explanation is relevant only inasmuch as one can show that not knowing the given cultural tradition, one could not enjoy a film the same way a ‘native speaker’ could. But if, on the contrary, the style can have the same effect on an alien to the given tradition, the historical explanation loses its aesthetic relevance (which does not mean that it is irrelevant biographically, historically or otherwise). For example, the time Tarkovsky dedicates to showing natural sceneries can be explained with reference to the relationship the Russian Orthodox tradition has to the icons, which, according to this tradition, are the sacred manifestations of the holy universe.8 This is doubtless correct, but anyone enjoying a Tarkovsky film would come to the conclusion that the beauty of the images, and the camera’s unusually long contemplation of them, provides the sensation of ‘seeing through’ the physical aspect of the objects or the natural scene toward some transcendental existence. On the other hand, if someone does not enjoy these long, slow, actionless, meditative images, knowing about their traditional background will not help a bit. Conversely, in other cases, it is necessary to learn about a cultural tradition in order to be able to appreciate its products. For example, much of Indian cinema is very difficult for a Western viewer to approach and to appreciate because of the vast differences between the way those films express the same human situations and feelings. Even theorists inspired by cognitive science, such as Patrick Hogan, admit that knowledge of ‘rasa theory, the theory of aesthetic emotion initially developed in ancient Sanskrit texts’ is necessary to understand and to tune ourselves in to the wavelength of Indian cinema.9 In these cases aesthetic and even some psychological effects are dependent on the knowledge and conceptual understanding of a cultural tradition. This is why culturalist and cognitivist explanations of works of art should treat each other as complementary rather than mutually exclusive.

As noted earlier, there is nothing ‘Hungarian’ in Béla Tarr, and no Hungarian cultural or cinematic tradition would help in appreciating or understanding his particular stylistic universe. (Complete ignorance of historical and geographical facts may obviously lead to serious misunderstandings, but misunderstanding will not influence appreciation, as some commentaries of foreign critics, academics and everyday viewers show.) The fact that in Hungarian post-war cinema Miklós Jancsó created a powerful long-take abstract cinematic style tells us nothing about why Tarr developed his own long-take abstract cinematic style. It tells us nothing because, firstly, many other international directors also developed some kind of long-take abstract cinematic style in the period Jancsó did; and secondly, in the cinema of Béla Tarr one can find many other influences too. So, tradition doesn’t explain anything; on the contrary, Hungarian art-film tradition had been anything but like the Tarr style when the latter appeared. On the other hand, as mentioned in the introduction, the combination of the main ingredients of the Tarr style has become itself an initiator of a fashion in 1990s Hungarian cinema (black and white, grim atmosphere, long takes). Consequently, the only way the Tarr style can be explained is through the effect is has on the viewer. To this end, we have to enter into the narrative universe of the Tarr films.

Notes