This chapter profiles the history, folklore, and science of 135 medicinal plants. Why these 135?

• They’re available. The selected herbs are generally Western in origin, from the Middle Eastern, European, and Native American healing traditions. Some Asian herbs have also been included. However, plants unique to Chinese herbalism have been omitted, despite their medical effectiveness, because they’re not widely available in the United States.

• They’re useful. All of the selected herbs have practical applications for everyday health concerns.

• They’re reasonably safe. The selected herbs rarely cause serious side effects when used as recommended. Each profile provides detailed information on dosage, precautions, and potential hazards. (See Chapter 2 for a general discussion of herb safety.)

• They’re often found in kitchen spice racks. Centuries ago, all of the herbs and spices used in cooking today were prized mainly for their use in food preservation and healing. Few people realize that they have valuable pharmacies in their kitchens.

• They’re fascinating. The Pied Piper was as much an herbalist as a musician (Valerian). The makers of Bayer were originally skeptical of aspirin (Meadowsweet). A 19th-century battle over abortion popularized a modern remedy for menstrual cramps (Black Haw). And cowboys who drank sarsaparilla were less interested in refreshment than in preventing venereal diseases (Sarsaparilla).

• They’re popular. Every year, the American Botanical Council, the leading medicinal herb organization, ranks medicinal herbs by popularity based on sales. This book includes all bestselling herbs.

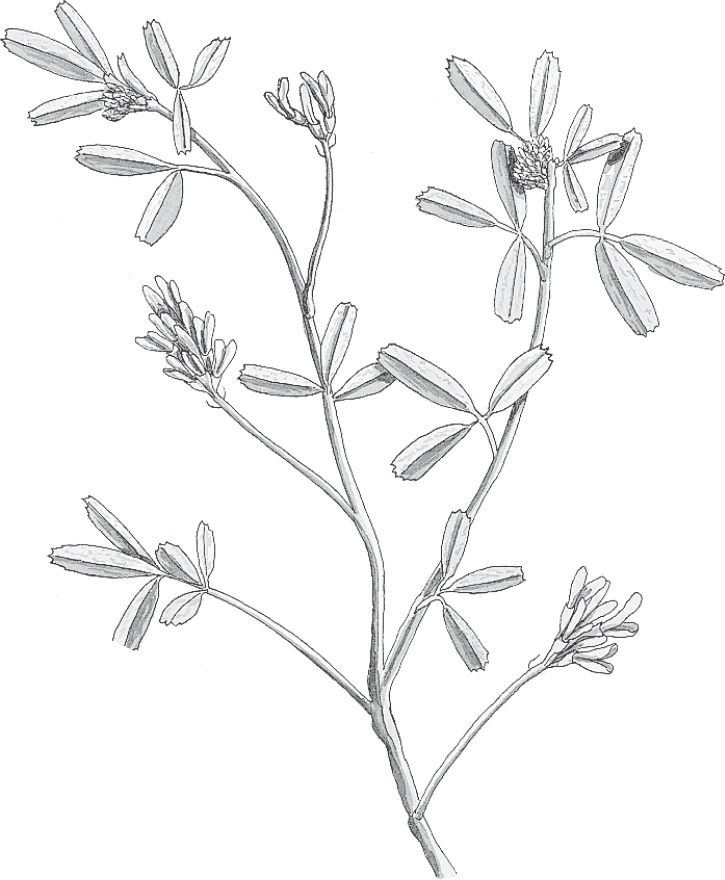

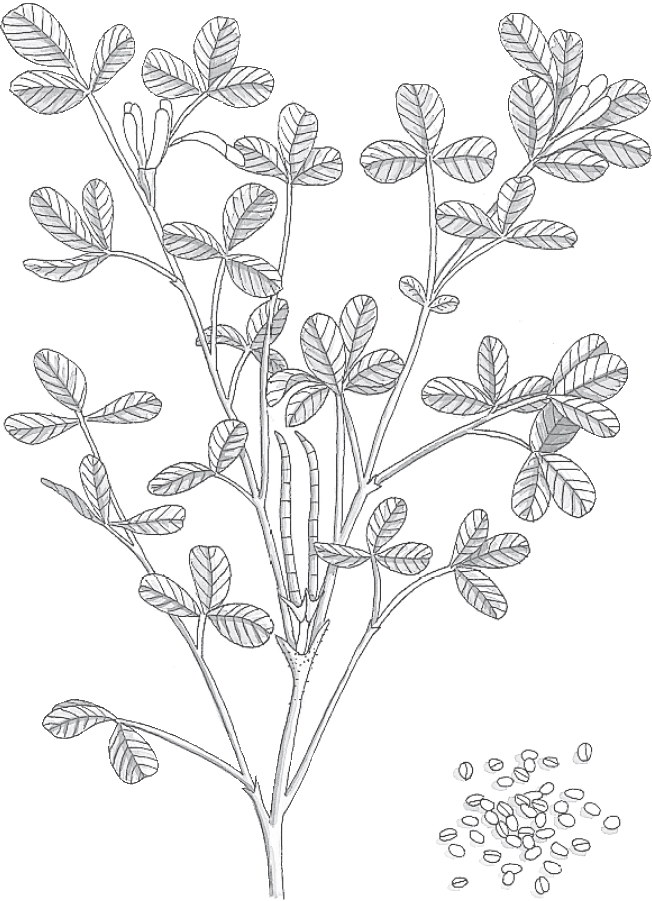

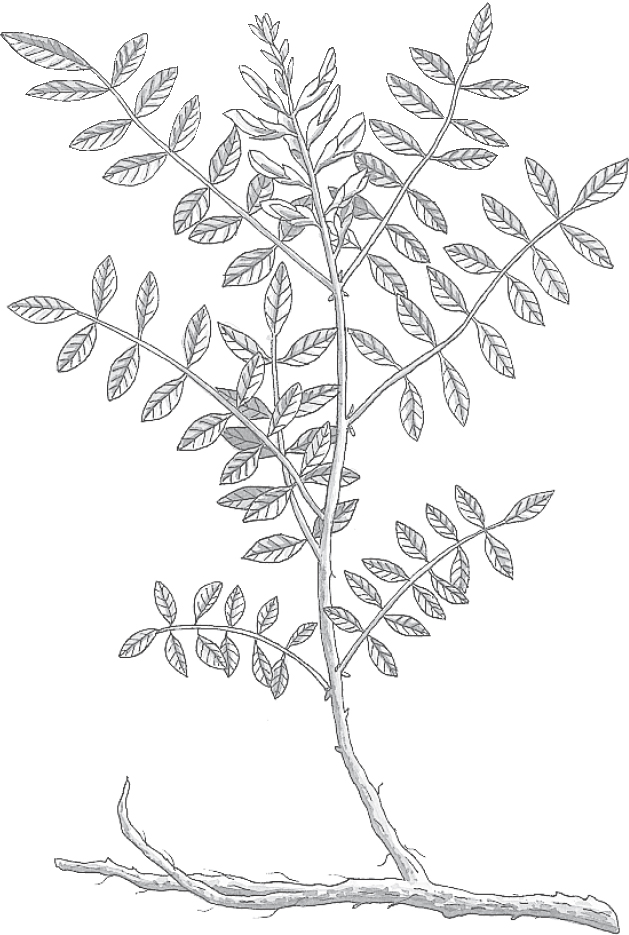

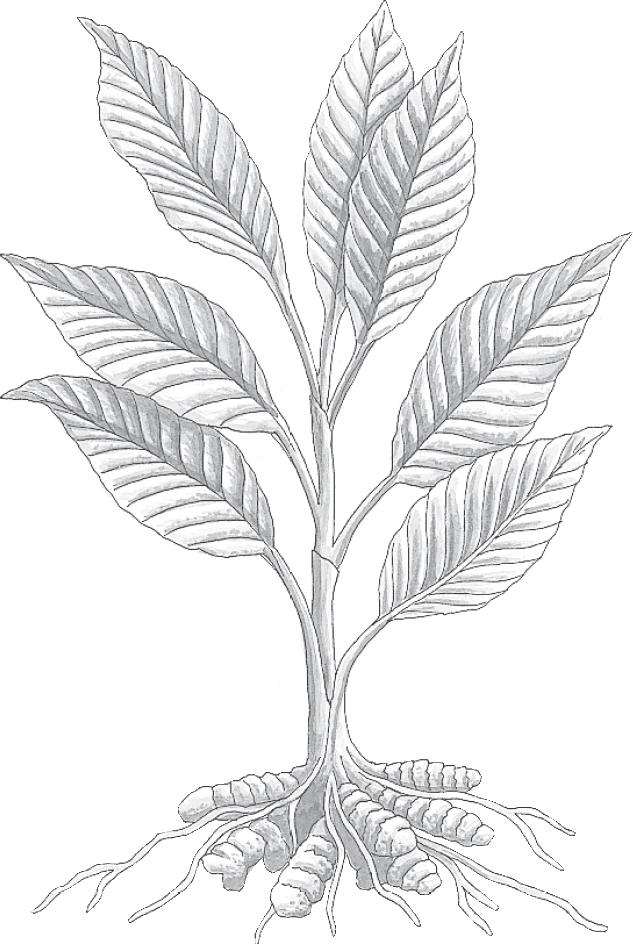

Family: Leguminosae; other members include beans and peas

Genus and species: Medicago sativa

Also known as: Chilean clover, buffalo grass, and lucerne (in Britain)

Parts used: Seeds, sprouts, and leaves

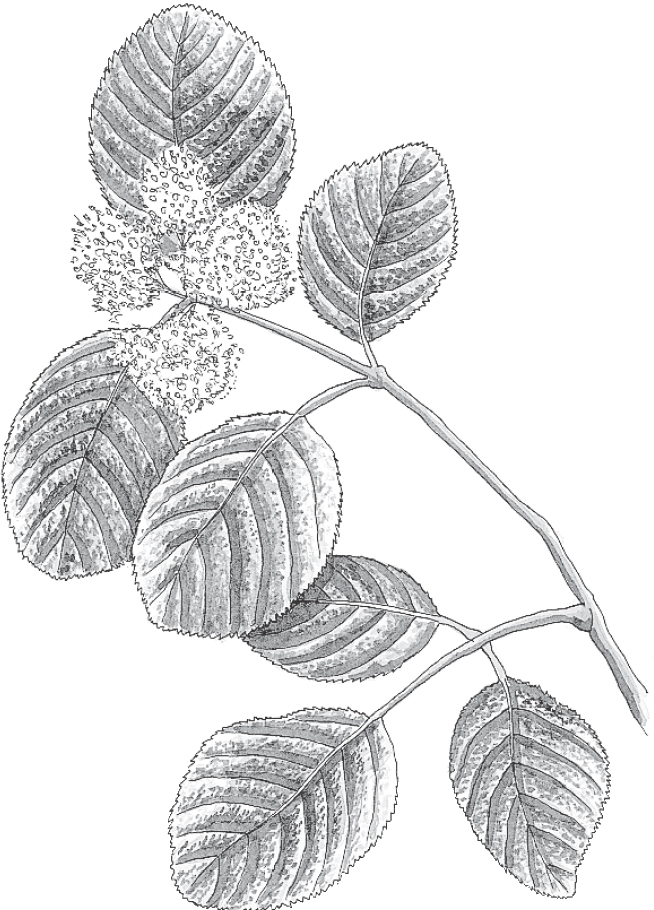

Alfalfa is the world’s oldest forage crop. Farmers have prized it since before the dawn of history. Since the 1970s, alfalfa sprouts have become a popular salad vegetable. But the seeds contain the real healing power. They reduce cholesterol, which helps prevent heart disease and most strokes.

What’s good for cattle is also good for people, or so the ancient Chinese thought. Their animals ate alfalfa so enthusiastically that the Chinese began cooking the herb’s tender young leaves as a vegetable. Soon, traditional Chinese physicians were using the plant to stimulate appetite and treat digestive problems, particularly ulcers.

Ancient India’s traditional Ayurvedic physicians also used alfalfa to treat ulcers, and also prescribed it for arthritis and fluid retention (edema).

The ancient Arabs fed their horses alfalfa, believing that it made the animals swift and strong. They called it al-fac-facah, or “father of all foods,” which the Spanish changed to alfalfa.

Spain introduced alfalfa into the Americas, where it became a popular forage crop, particularly in the Great Plains. Like the ancient Chinese, the pioneers believed that what was good for their cattle was good for them. They used alfalfa to treat arthritis, boils, cancer, scurvy, and urinary and bowel problems. Pioneer women used it to produce menstruation.

After the Civil War, alfalfa fell out of favor as a healing herb. It wasn’t until the 1970s that it returned to popularity via the salad bowl.

Most of alfalfa’s traditional therapeutic uses have long been disproved. But scientists have discovered an alfalfa benefit our ancestors never dreamed of. This herb helps prevent heart disease, stroke, and cancer, the nation’s top three killers.

HEART DISEASE AND STROKE. Animal studies show that alfalfa leaves and seeds reduce blood cholesterol levels. High cholesterol raises risk for heart attack and most strokes. (Alfalfa sprouts produce a similar, but less pronounced benefit.) Scandinavian researchers gave alfalfa seeds (1.5 ounces three times a day) to 15 people with high cholesterol. After 8 weeks, their cholesterol level fell significantly.

CANCER. One study suggests that alfalfa helps neutralize cancer-causing substances in the intestine. Another, published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, shows that the herb binds carcinogens in the colon and helps speed their elimination.

WOMEN’S HEALTH. Alfalfa seeds contain two compounds, stachydrine and homostachydrine, that promote menstruation. They may also trigger miscarriage. Pregnant women should not eat alfalfa seeds. But women should not consider this herb a reliable contraceptive.

BAD BREATH. Alfalfa is rich in the green plant pigment chlorophyll, the active ingredient in most commercial breath fresheners. Sip an alfalfa infusion if you’re concerned about bad breath.

In laboratory studies, alfalfa helps fight disease-causing fungi. One day, it may be used to treat fungal infections.

Some herbalists still espouse the age-old view that alfalfa treats ulcers, but scientific research has found no support for this.

Herbalists also recommend alfalfa for bowel problems and as a diuretic to treat fluid retention. Unfortunately, these traditional uses have not held up under scientific scrutiny either.

Although some supplement manufacturers promote alfalfa tablets as a treatment for asthma and hay fever, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association shows that these claims have no merit. Alfalfa contains neither bronchodilators, which arrest an asthma attack, nor antihistamines, which relieve hay fever.

While alfalfa sprouts dress up salads, it’s the leaves and seeds that are used in herbal healing. Alfalfa leaf and seed tablets and capsules are available in most health food stores and supplements shops. Take them according to package directions.

When using the bulk herb, prepare medicinal infusions with 1 to 2 teaspoons of dried leaves and/or bruised seeds per cup of boiling water and steep for 10 to 20 minutes. Enjoy up to 3 cups a day to help reduce cholesterol in addition to cholesterol-lowering drugs your doctor prescribes. Alfalfa has a hay-like aroma and tastes like chamomile, with a slightly bitter aftertaste.

Wash alfalfa sprouts carefully. They may become contaminated with E. coli or Salmonella bacteria and cause food poisoning.

Do not consume more than recommended amounts of alfalfa seeds. They contain the potentially toxic amino acid canavanine. According to a report in Lancet, over time, eating large quantities of seeds may cause the reversible blood disorder pancytopenia. This condition impairs infection-fighting white blood cells and platelets, necessary for clotting.

The canavanine in alfalfa seeds has also been linked to systemic lupus erythematosus, a potentially serious auto-immune disease. Alfalfa seeds have reactivated the disease in people who were in remission, according to the New England Journal of Medicine. Another study shows that the seeds induce lupus in monkeys. If you have lupus or have ever had pancytopenia, do not use alfalfa.

Pregnant and nursing women should not use alfalfa, except sprouts in salads.

Do not give alfalfa to children under 2. In older children, adjust the recommended dose based on the child’s weight. Give a 50-pound child one-third of the dose a 150-pound adult would take.

If you’re over 65, start with a low dose, and increase only if necessary.

Inform health professionals of the herbs you use. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Alfalfa may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If any develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional.

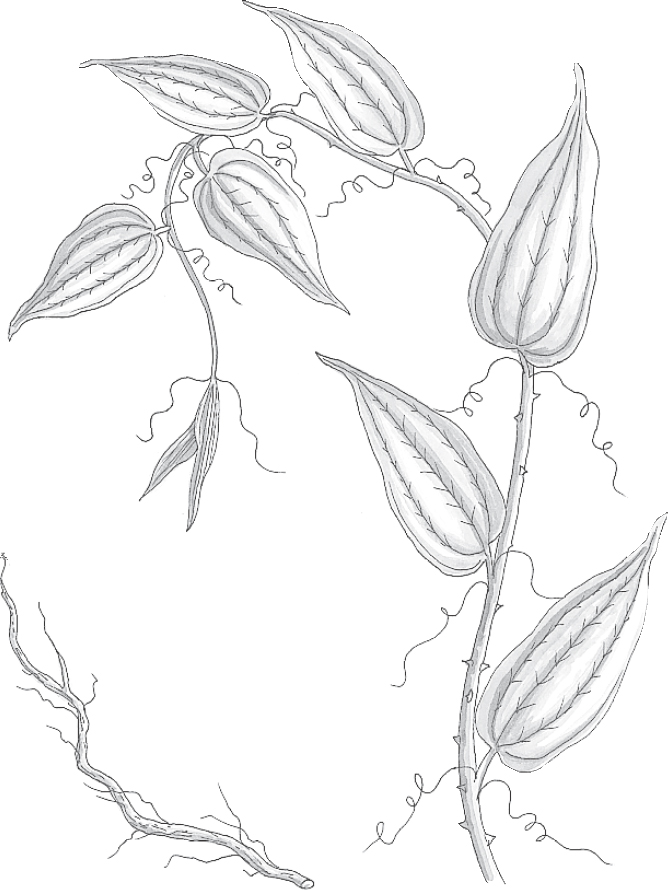

Alfalfa grows throughout most of the United States. The plant is a deep-rooting, bushy perennial that grows to 3 feet, resembling tall clover. The leaves are divided into three leaflets. Depending on location, the herb’s lavender, blue, or yellow flowers bloom from May through October.

Alfalfa grows best in loamy soil. It tolerates clay but not sand, which lacks sufficient nutrients. Prepare the soil with manure and rock phosphate. Sow seeds in autumn in rows 18 inches apart. Young plants require regular watering, but once established, they become fairly drought tolerant.

Harvest when plants bloom by cutting them back to within 3 inches of the ground, then hang them to dry. When dry, pick off the leaves.

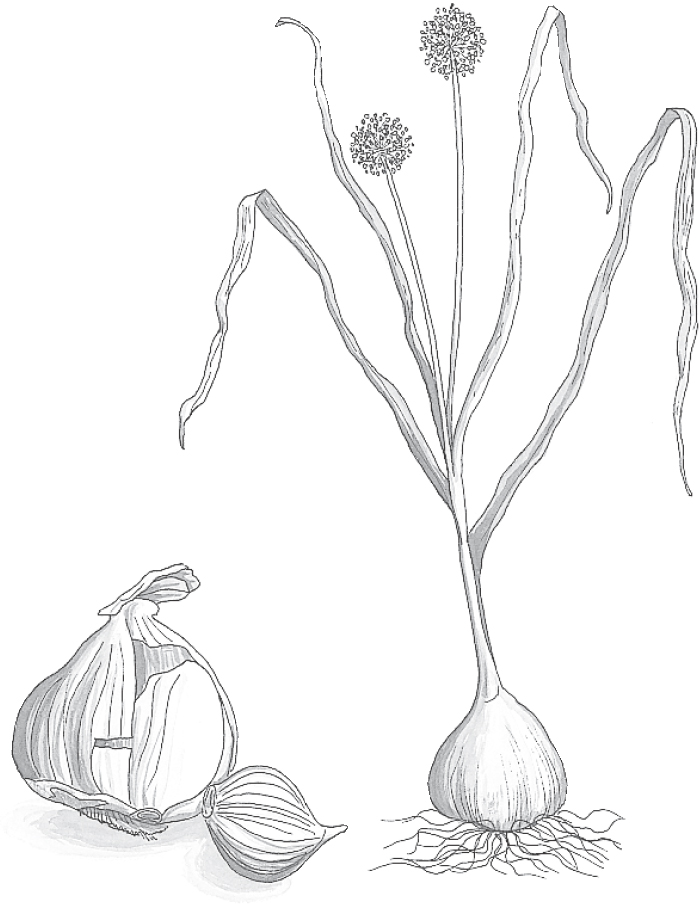

Family: Liliaceae; other members include lily, tulip, garlic, and onion

Genus and species: Aloe vera and an estimated 500 other species

Also known as: Cape, Barbados, Socotrine, and Zanzibar aloe

Parts used: Leaf gel, juice, or latex

Every kitchen windowsill should house a potted aloe. That’s where minor burns, scalds, and cuts occur. It’s easy to snip one of the plant’s thick, fleshy leaves and scoop the inner gel onto the injury. Aloe gel dries into a natural bandage. It also promotes wound healing and helps prevent infection.

In addition, aloe latex, extracted from cells on the leaf’s inner skin, is a powerful laxative—so potent that many authorities discourage ingesting it.

Our word aloe comes from the Arabic alloeh, meaning “bitter and shiny,” an apt description of the plant’s wound-healing leaf gel. Drawings of aloe have been found in Egyptian temples dating to 3000 BC. The Bible mentions aloe several times, for example, “I have perfumed my bed with myrrh, aloes, and cinnamon” (Proverbs 7:17).

Egyptian prescriptions from 1500 BC recommend aloe for infections and skin problems and as a laxative, uses supported by modern science.

Aloe is one of the few non-narcotic plants to cause a war. When Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 BC, he heard of a plant with amazing wound-healing powers on an island off Somalia. Intent on healing his soldiers’ wounds—and on denying this healer to his enemies—Alexander sent an army to seize the island and the plant, which turned out to be aloe.

The Greek physician Dioscorides recommended aloe externally for wounds, hemorrhoids, ulcers, and hair loss. The Roman naturalist Pliny prescribed it for internal use as a laxative.

Arab traders carried aloe from Spain to Asia around the 6th century, introducing it to India’s traditional Ayurvedic physicians, who used it to treat skin problems, intestinal worms, and menstrual discomforts. Chinese healers used it similarly.

More recently, American pioneers relied on aloe gel to treat wounds, burns, and hemorrhoids.

Contemporary herbalists—and scientists—agree with Dioscorides’ 2,000-year-old observation that applied topically, aloe treats wounds.

WOUNDS (burns, scalds, scrapes, and sunburn). Aloe contains compounds—bradykinase, salicylic acid, and magnesium lactate—that reduce the pain, inflammation, swelling, and redness of wounds. Scientific evidence of aloe’s wound-healing power was first documented in 1935, when an American medical journal reported accelerated healing of X-ray burns with aloe gel scooped from the plant’s cut leaves. Since then, dozens of studies have supported the herb’s ability to stimulate healing of first- and second-degree burns. Asian researchers analyzed many studies of aloe for wound healing. Compared with standard care, the wounds of those using aloe healed significantly faster—up to 8 days faster.

Aloe works best for superficial wounds. In a study published in the Journal of Dermatology and Surgical Oncology, the herb sped the healing of pimples by 3 days compared with standard medical treatment. For deep wounds, however, aloe slows healing. That’s what researchers found in a study of aloe treatment of cesarean section incisions. Their study, published in Obstetrics and Gynecology, showed that incisions not treated with aloe gel healed in 53 days, but those treated with aloe took 83 days. Use aloe gel on superficial wounds, but don’t use it on deep wounds requiring stitches.

INFECTIONS. In addition to wound healing, aloe gel also helps prevent wound infections. Several studies have shown aloe to kill many different bacteria and fungi that can infect wounds, including E. coli, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Salmonella, Shigella, and Candida. It also boosts the immune system, which helps the body fight infection.

ACNE AND POISON PLANTS. Beyond wounds, aloe also helps heal other minor skin afflictions, including acne and rashes caused by poison ivy, oak, and sumac.

PSORIASIS. Affecting some 7 million Americans, this autoimmune skin condition causes eruptions of red, raised skin patches usually topped with scaly tissue. At Malmo University Hospital in Sweden, researchers gave 60 people with psoriasis either a medically inactive placebo cream or one containing 0.5 percent aloe gel. The participants applied the creams three times a day, 5 days a week, for 16 weeks. Among those using the placebo cream, 7 percent experienced substantial clearing of their skin patches. But in the aloe group, that figure was 83 percent.

GENERAL SKIN CARE. To make her more alluring, Cleopatra’s servants massaged aloe gel into her skin. The herb remains a popular ingredient in skin-care products. But if you’re after beautiful skin, do what the legendary beauty did: Use the fresh leaf gel. The “stabilized” (preserved) gel found in commercial skin-care products and shampoos may not provide the fresh herb’s benefits. If you enjoy aloe fragrance in shampoos and skin lotions, that’s fine. Just don’t expect them to turn you into Cleopatra.

DIABETES. Several animal studies show that aloe juice reduces blood sugar (glucose) levels in experimental animals. Thai researchers gave 72 diabetics either a placebo or aloe juice (1 teaspoon twice daily). After 6 weeks, the aloe group’s blood sugar fell significantly.

GUM DISEASE. Indian researchers gave 345 young adults with gum disease (gingivitis) either a placebo, a drug used to treat it (chlorhexidine), or a mouthwash containing aloe vera juice. After a month the drug and herb worked significantly better than the placebo, and aloe was as effective as the drug.

Aloe juice and aloe-based beverages are widely available in health food stores. Their labels claim that they soothe the digestive tract. Anecdotal reports suggest possible benefits for inflammatory bowel disease (colitis and Crohn’s disease), but there is no rigorous research to support this.

Laboratory studies show that aloe kills the fungus that causes vaginal yeast infections (Candida albicans), and some herbalists recommend using it to treat the infection itself. But just because it kills the fungus in test tubes doesn’t mean that it treats the infection in the body. No scientific studies support this use, and an FDA advisory panel found insufficient evidence to recommend aloe as a yeast treatment.

In laboratory tests, a compound in aloe called aloe-emodin has shown promise against leukemia. But National Cancer Institute scientists say that experimental preparations are still too toxic to give to people with leukemia.

Finally, folk herbalists have recommended topical aloe to treat skin cancer. This has never been studied scientifically.

To help soothe and heal burns, scalds, scrapes, and sunburn and to help prevent superficial wound infections, first clean the wound with soap and water. Then select a lower (older) aloe leaf and cut off several inches. Slice it lengthwise, scoop the gel onto the wound, and let it dry. As for the injured leaf, it quickly closes its own wound. Its remaining gel can be used another time.

To enjoy the cosmetic benefits of aloe, apply the leaf gel to freshly washed skin. Stop if it causes irritation.

Aloe gel is safe for external use by anyone who does not develop an allergic reaction.

If a wound treated with aloe does not heal significantly within two weeks or if it gets worse, consult a doctor.

Commercial aloe juice may have a mild laxative effect, but stay away from laxatives containing aloe latex. The latex contains laxative compounds (anthraquinones) with powerful purgative action that may cause cramping, diarrhea, and severe intestinal cramps. Other laxative herbs—senna, rhubarb, buckthorn, and cascara sagrada—also contain anthraquinones, but work more gently.

Despite recommendations not to use aloe as a laxative, some supplement companies sell aloe laxative tablets on the strength of approval by Commission E, the expert panel that evaluates herbal medicines for the German counterpart of the FDA. If you try aloe as a laxative, never exceed the dose on the label, and if you develop intestinal cramps, reduce your dose or stop taking it. If you’re looking for a natural laxative, start with an effective but gentler herb, psyllium.

Women who are pregnant or trying to conceive should not take aloe latex, as its cathartic nature may stimulate uterine contractions and trigger miscarriage. Nor should the latex be used by nursing mothers. It enters mother’s milk and may cause stomach cramps and violent catharsis in infants.

Aloe latex’s cathartic power may also aggravate ulcers, hemorrhoids, diverticulosis, diverticulitis, colitis, Crohn’s disease, or irritable bowel syndrome. Anyone with a gastrointestinal illness should not use aloe latex as a laxative.

In general, aloe latex is not recommended for internal use in children or adults.

Inform health professionals of the herbs you use. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Aloe may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If any develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

Got a brown thumb? Then aloe is your perfect houseplant. All it requires is a little water. Aloe prefers sun, but it tolerates shade and doesn’t mind poor soil. The only conditions this hardy succulent cannot tolerate are poor drainage and cold. Bring potted aloe indoors before the temperature falls below 40°F.

Aloe periodically produces offshoots, which you may remove and replant when they are a few inches tall. Simply uproot or unpot the plant, work the soil gently to separate the offshoot, and return the mother plant to its bed or pot.

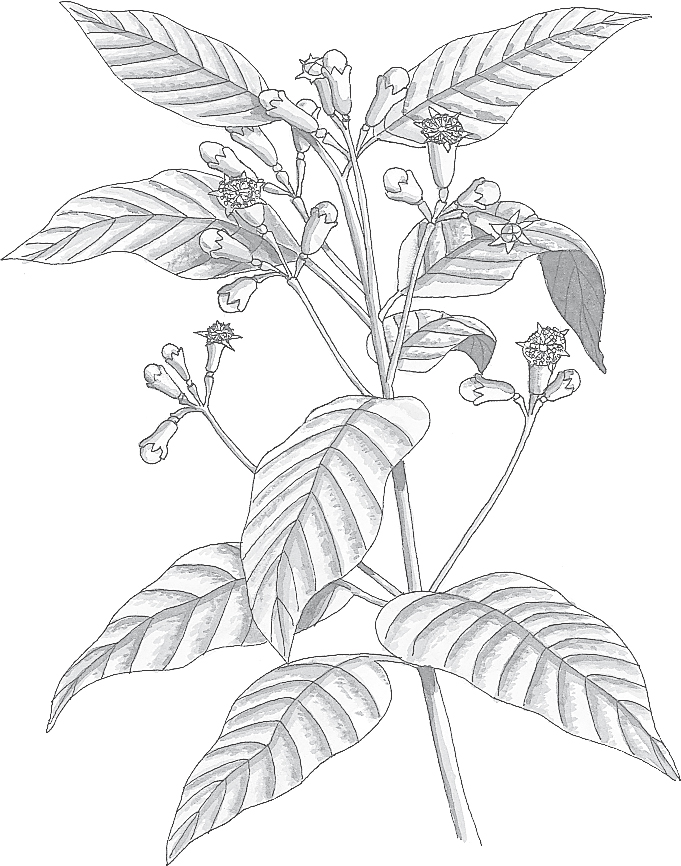

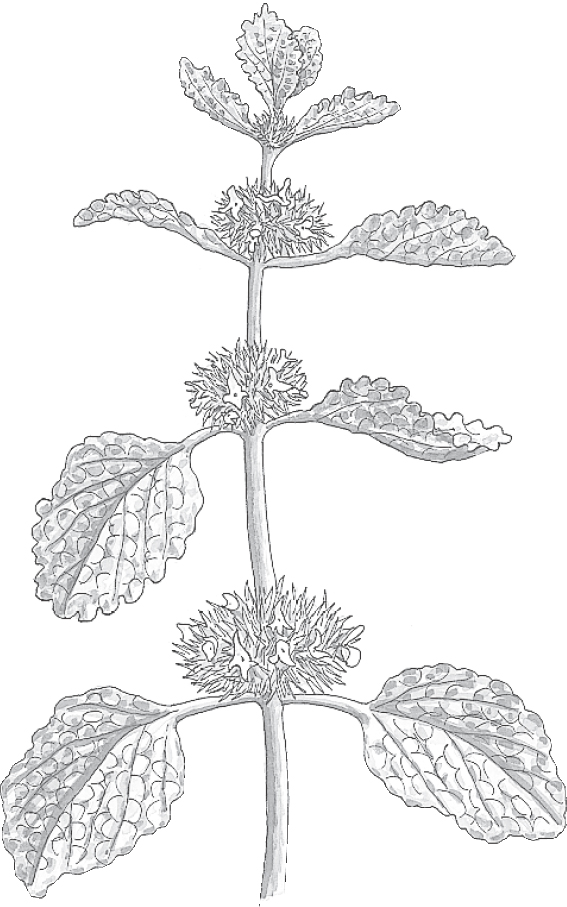

Family: Acanthaceae; other members include acanthus

Genus and species: Andrographis paniculata

Also known as: Kalmegh, Kan Jang

Parts used: Mostly leaves, sometimes root

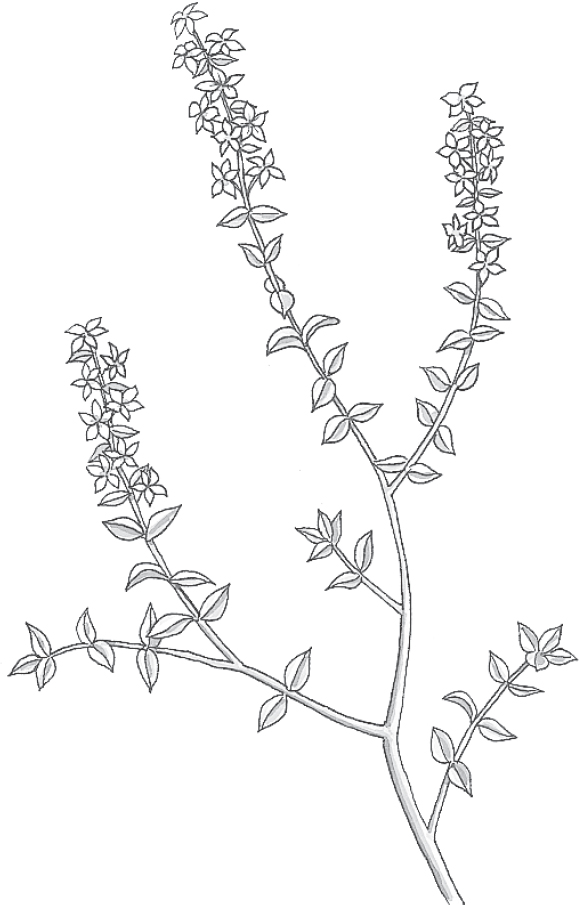

Many healing herbs taste bitter. But andrographis, an annual native to India, is so bitter that centuries ago, Indians named it kalmegh, Bengali for “king of the bitters.”

Like many bitter herbs, India’s traditional Ayurvedic physicians prescribed andrographis to promote digestion, increase appetite, and treat stomach distress. In addition, they recommended the herb to treat fever, snakebites, and jaundice (liver disease). Traditional Chinese physicians considered andrographis a “cold” herb and used it to treat conditions involving excessive heat, for example, fever.

IMMUNE STIMULATION. Andrographis boosts the ability of white blood cells to gobble up invading germs, including E. coli, the bacteria that cause urinary tract infections, and Shigella, which causes infectious diarrhea (dysentery).

COLDS, FLU, AND SINUS INFECTION. Andrographis also improves the body’s ability to fight the viruses that cause colds and flu. Swedish researchers gave either a placebo or the herb to 179 adults with cold symptoms: sore throat, nasal congestion, runny nose, watery eyes, and cough. After 3 days, the andrographis group showed highly significant benefit, especially in relief of sore throat. A dozen other studies around the world agree that treatment with andrographis results in shorter, milder colds in both adults and children, without significant side effects.

Russian researchers gave a placebo or andrographis to 540 people with flu symptoms (cold symptoms plus fever and muscle aches). Their conclusion: The herb “contributes to quicker recovery and reduces risk of post-influenza complications,” for example, bronchitis. Andrographis caused no significant side effects.

Finally, Thai researchers analyzed many cold and flu studies of andrographis. They concluded that the research “supports the usefulness of andrographis in reducing the severity of upper respiratory tract infections.”

FEVER, PAIN, AND INFLAMMATION. At a dose of 6 grams, the herb reduces fever, validating this use by traditional Chinese physicians. In one Chinese study, the herb reduced fevers in 70 of 84 subjects within 48 hours. In another, Thai researchers gave either a placebo or andrographis (6 grams/day) to 152 people with fever and sore throat caused by tonsillitis. After one week, the herb group reported significantly greater relief, results similar to that produced by acetaminophen (Tylenol).

URINARY TRACT INFECTION. Thai researchers gave either andrographis (1,000 milligrams/day) or antibiotics to women with UTI. The herb was as effective as the pharmaceuticals.

LIVER PROTECTION. When people ingest liver-toxic chemicals or develop hepatitis, the organ overproduces several enzymes. In animal studies, andrographis helps return liver enzyme to normal, especially when the cause of the damage was alcohol, certain carcinogens, or parasites. Andrographis protects the liver as well as the milk thistle extract, silymarin.

An Armenian study showed andrographis beneficial for sinus infection.

One animal study shows that pretreatment with andrographis reduced deaths from cobra venom, possibly validating the traditional Indian practice of using the herb to treat snakebite.

Animal studies suggest that andrographis lowers blood sugar, which might help control diabetes.

Pilot studies suggest that andrographis might combat malaria.

The herb also appears to reduce blood clotting, including the internal blood clots that cause heart attack and most strokes. If confirmed, someday andrographis might help prevent these conditions.

For immune stimulation in adults, try 2 to 3 grams/day of liquid extract (1 to 2 teaspoons). To treat colds and flu, the dose is 6 grams/day (4 teaspoons). But liquid extracts are too bitter to be palatable. Most andrographis products are sold as capsules. Follow package directions.

Andrographis is considered nontoxic, however, at doses several times higher than recommended, stomach distress, loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting are possible.

Andrographis impairs blood clotting. If you have a clotting disorder or are taking anticoagulant medication (including aspirin), talk to your doctor before using andrographis. Stop using it 2 weeks before elective surgery.

At high doses, andrographis suppresses the fertility of both male and female laboratory animals. The one human trial showed sperm suppression. Couples hoping to conceive should avoid it.

Pregnant and nursing women should not use andrographis.

Do not give andrographis to children under 2. In older children, adjust the recommended dose based on the child’s weight. Give a 50-pound child one-third of the dose a 150-pound adult dose.

If you’re over 65, start with a low dose, and increase only if necessary.

If you use this herb, inform your health professionals. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Andrographis may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If unusual symptoms develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

Andrographis is not grown in the United States.

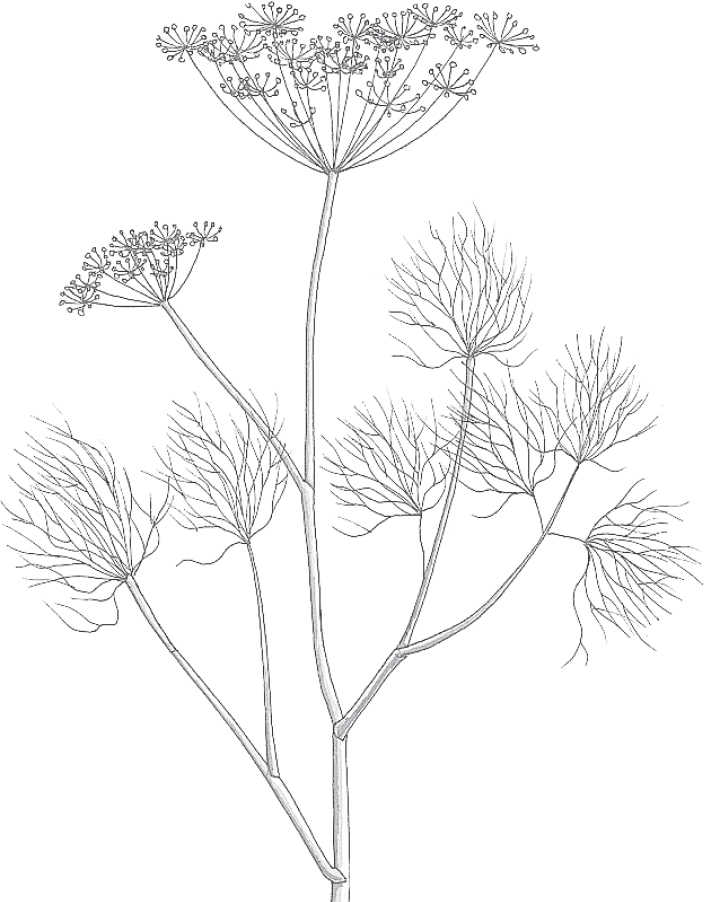

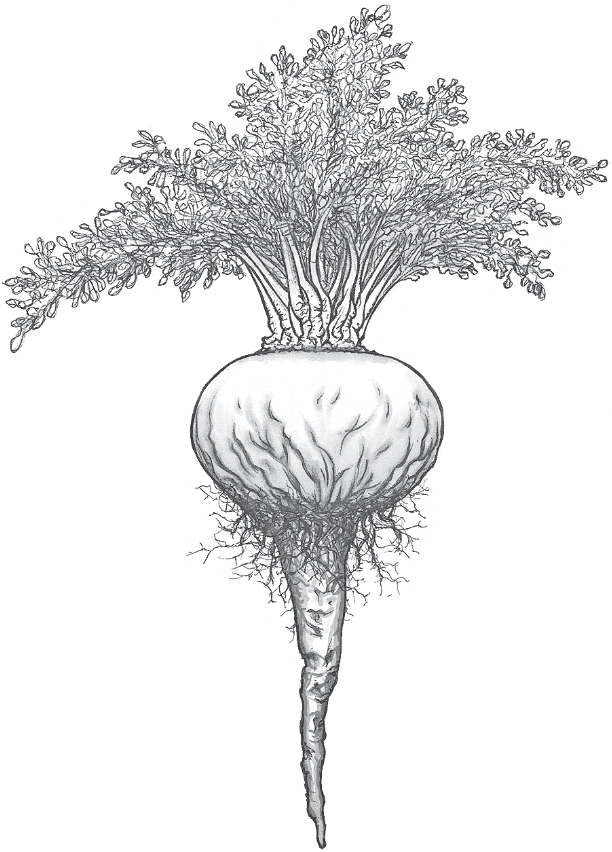

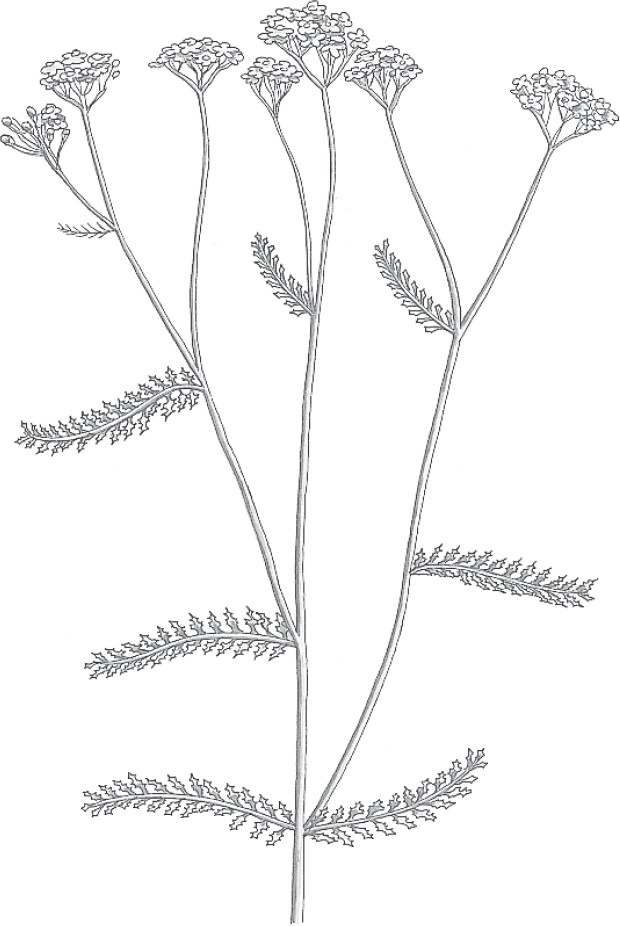

Family: Umbelliferae (carrot, parsley, celery, fennel, dill)

Genus and species: Angelica archangelica (European), A. atropurpurea (American), A. sinensis (Chinese), and other species

Also known as: Wild celery and masterwort; in China, dang gui or dong quai

Parts used: Roots, leaves, and seeds

Tall, striking, and attractive, angelica has played a role in magic and medicine for thousands of years. But the species used in Western and Chinese herbal medicine differ. So, too, are the opinions of the herb’s medicinal value.

In the West, European angelica has always been a minor healing herb. But in Asia, Chinese angelica, usually called dang gui, has long been considered a major boon for gynecological complaints. This claim is controversial, but Western researchers may have been too quick to dismiss Chinese angelica as worthless.

In Asia, Chinese angelica has been used since the dawn of history. It has always been considered the premier tonic for menstrual problems, menopausal complaints, and other women’s health concerns. Traditional Chinese practitioners and Indian Ayurvedic physicians continue to prescribe it for gynecological conditions, arthritis, abdominal pain, colds, and flu.

During the Middle Ages, European peasants considered European angelica magical. They fashioned angelica leaves into necklaces to protect their children from illness and witchcraft. Angelica was reputed to be the only herb witches never used. Its presence in women’s gardens or cupboards was considered a persuasive defense against charges of witchcraft.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the juice from crushed angelica roots was combined with other herbs to make “Carmelite water.” This medieval drink was said to cure headache, promote relaxation and long life, and protect against poisons and witches’ spells.

In 1665, Europe was decimated by bubonic plague. Legend has it that a monk dreamed he met an angel, who gave him an herb to cure the scourge. The monk named the herb angelica, in honor of the messenger in his dream. The name stuck, and the Royal College of Physicians in London incorporated angelica water into England’s official plague remedy, the King’s Excellent Plague Recipe.

History provides no clear verdict on the effectiveness of the “excellent recipe,” but the old monk’s dream may have been prophetic. Bubonic plague is a bacterial disease, and modern science has discovered that compounds in angelica have antibacterial action.

European angelica has hollow stems. Air can pass through them. Under the Doctrine of Signatures—the medieval belief that an herb’s physical appearance reveals its healing benefits—hollow-stemmed plants were considered beneficial for respiratory problems, and during the 17th century, angelica was a popular treatment for colds, flu, and asthma.

When European colonists arrived in North America, they found Native Americans using American angelica as they did—to treat respiratory ailments, particularly tuberculosis. Eventually, the colonists began using large doses to induce abortion.

Nineteenth-century American Eclectic physicians, forerunners of today’s naturopaths, recommended angelica for heartburn, indigestion, bronchitis, malaria, and typhoid.

Contrary to legend, angelica does not deliver humanity from epidemic disease, but the Chinese herb has caused a good deal of controversy. Some studies show benefit for menopausal discomforts, while others do not. Meanwhile, most traditional uses for European angelica look iffy.

Contemporary herbalists recommend angelica mostly for digestive problems and to help clear mucus. These uses may have some validity.

MENOPAUSAL COMPLAINTS. Israeli researchers gave 55 women complaining of hot flashes either a placebo or a combination of dang gui and chamomile (75 milligrams dang gui and 30 milligrams chamomile, five times a day). After 12 weeks, the herb group reported significantly greater relief.

Researchers at the National College of Naturopathic Medicine in Portland, Oregon, and Bastyr University, the naturopathic medical school in Kenmore, Washington, gave thirteen menopausal women either medically inactive placebos or a Chinese herbal formula containing dang gui, licorice root, hawthorn leaf, burdock root, and wild yam root. After 3 months, the women who took the herbal formula reported significantly greater relief.

However, Kaiser Permanente researchers in Oakland, California, gave dang gui to 71 menopausal women for 3 months. They reported no benefit. Experts in Chinese herbal medicine have criticized the Kaiser Permanente study because it used only dang gui. In Chinese herbal medicine, the herb is never used alone.

While the jury is still out on dang gui for menopausal complaints, formulas containing the herb appear to soothe hot flashes.

HEART DISEASE AND STROKE. Angelica species contain compounds, coumarins, with anticoagulant (blood-thinning) action. Blood thinners are used to prevent the internal blood clots that trigger heart attacks and most strokes. Chinese studies show that dang gui extract administered by injection helps dissolve the clots that cause stroke.

RESPIRATORY AILMENTS. Score one for the Doctrine of Signatures. German researchers have determined that angelica relaxes the windpipe, suggesting that it may have some value in treating colds, flu, bronchitis, and asthma.

DIGESTIVE COMPLAINTS. The same German investigators found that angelica relaxes the intestines. This lends some credence to the herb’s traditional use in treating digestive complaints.

ARTHRITIS. Japanese researchers report that angelica has anti-inflammatory effects, so there may be something to its traditional Asian use for treating joint pain.

A Chinese pilot study suggests that dang gui may increase red blood cell production, hinting that it may someday prove beneficial in treating anemia.

The Chinese have also found that dang gui improves liver function in people with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis. Their research is preliminary, however, and no specific recommendations can be made at this time about using angelica for liver problems.

A Chinese pilot study suggest that dang gui may help treat ulcerative colitis.

If you’d like to use Chinese angelica to treat gynecological problems, consult a practitioner of Chinese herbal medicine for a multi-herb formula.

Commission E, the expert panel that evaluates herbal medicines for the German counterpart of the FDA, endorses European angelica as a treatment for appetite loss, abdominal distress, and flatulence.

For an infusion, use 1 teaspoon of powdered seeds or leaves per cup of boiling water. Steep for 10 to 20 minutes and strain if you wish.

For a decoction, use 1 teaspoon of powdered root per cup of water. Bring to a boil and simmer for 2 minutes. Remove from the heat, let stand for 15 minutes, and strain if you wish. Drink up to 2 cups a day. Angelica decoctions taste bitter. Add sweetener.

With a homemade tincture, use ½ to 1 teaspoon up to twice a day.

When using commercial preparations, follow the package directions.

Angelica has never been shown to stimulate uterine contractions, but given its traditional use to induce menstruation and abortions, women who are pregnant or trying to conceive should avoid it.

Angelica contains compounds known as psoralens. Exposure to sunlight may cause a rash in those who ingest psoralens (photosensitivity). Psoralens may also promote tumor growth, leading the authors of a report in the journal Science to advise against taking angelica internally.

On the other hand, an animal study showed that the angelica constituent alpha-angelica lactone has an anticancer effect. Angelica’s role in human cancer, if any, remains unclear. People with cancer histories probably should not use it until the controversy has been settled.

Fresh angelica roots are poisonous. Drying eliminates the hazard. Dry roots thoroughly before using them.

Unless you are a confident field botanist, do not collect angelica in the wild. It’s easy to confuse with water hemlock (Cicuta maculata), which is extremely poisonous.

For adults who are not pregnant or nursing and have no history of cancer, heart attack, or photosensitivity, angelica is considered reasonably safe in amounts typically recommended.

Do not give angelica to children under 2. In older children, adjust the recommended dose based on the child’s weight. Give a 50-pound child one-third of the dose a 150-pound adult would take.

If you’re over 65, start with a low dose, and increase only if necessary.

Inform health professionals of the herbs you use. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Angelica may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If any develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

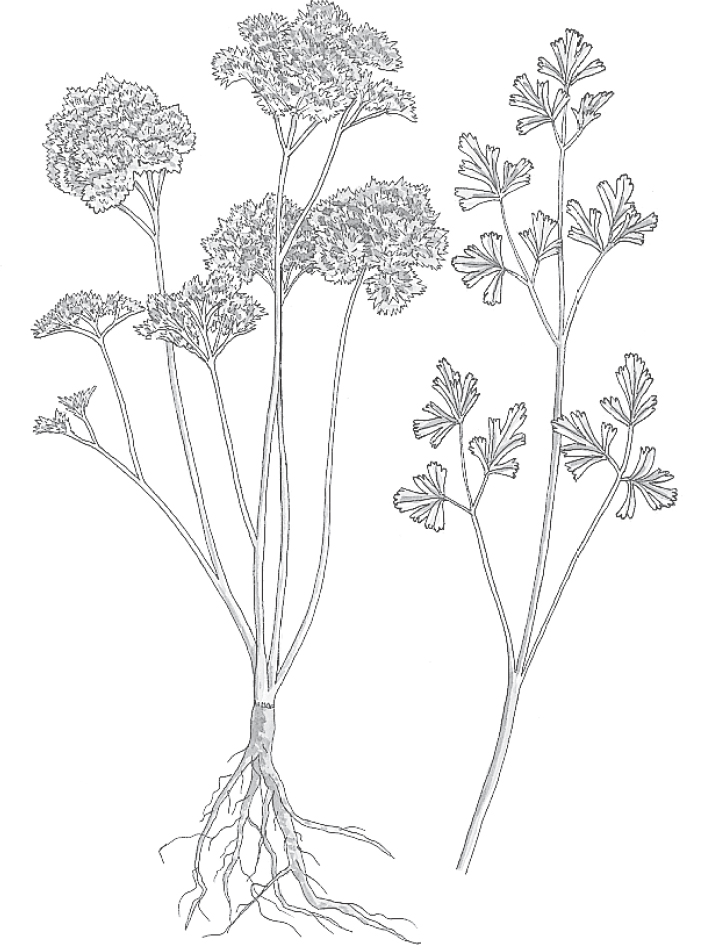

Angelica often blooms around May 8, the feast day of St. Michael the Archangel, which is the source of European angelica’s species name, archangelica. The plant grows to 8 feet and resembles celery—hence its common name, wild celery. It’s a biennial that dies after producing seeds.

Angelica grows from seeds or root divisions. Seed viability is relatively brief, only about 6 months, but refrigeration extends it up to a year. Germination may take a month. Sow angelica in the fall or spring ½ inch deep in well-prepared beds. Space plants 2 feet apart in all directions.

Angelica thrives in rich, moist, well-drained, slightly acidic soil. It prefers partial shade. Leaves may be harvested in the fall of the first year and roots during the spring or fall of the second year.

Angelica is not usually considered a culinary herb, but fresh leaves provide a zesty accent to soups and salads. Leaves have a fragrant aroma and a warm, vaguely sweet taste reminiscent of juniper, followed by a bitter aftertaste. You can eat steamed stems with butter. Chopped stems add flavor to roast pork.

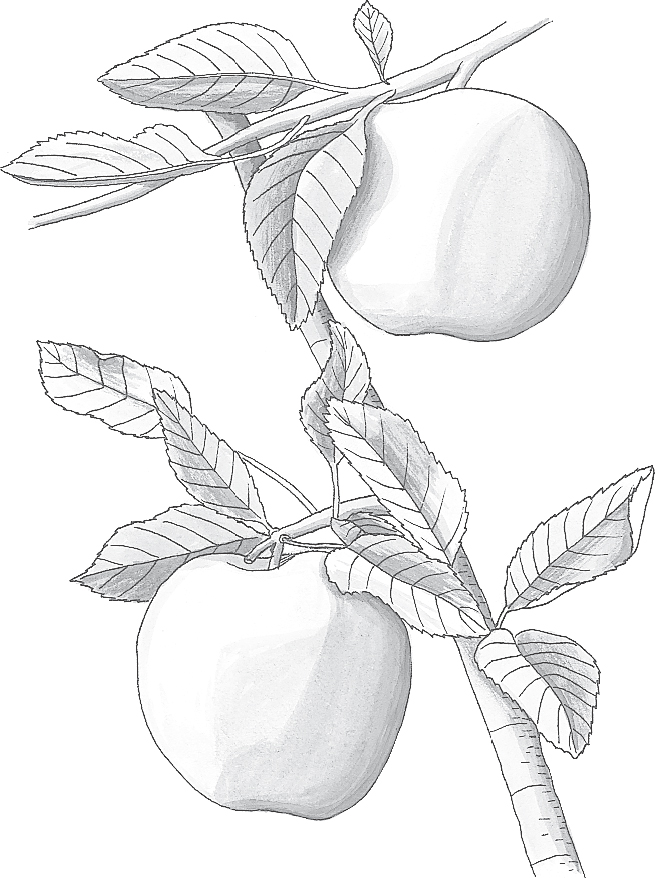

Family: Rosaceae; other members include rose, peach, almond, and strawberry

Genus and species: Malus sylvestris or Pyrus malus

Also known as: No other common names

Parts used: Fruits

An apple a day keeps the doctor away. The old rhyme is truer than ever, particularly if the doctor is a gastroenterologist, oncologist, or cardiologist. Apples help prevent and treat both diarrhea and constipation and may also help prevent America’s top three killers: cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

Few herbalists consider the apple an herb, but the tasty fruit has a long tradition as a healer. So much of what ancient herbalists believed about this delectable fruit has been scientifically supported that it’s time to return the apple to the herbal-medicine roster.

The Bible never identifies the Garden of Eden’s “forbidden fruit,” but since ancient times, people have believed that it was an apple. Legend has it that a piece got stuck in Adam’s throat, hence our “Adam’s apple.”

The “apple of discord” started the Trojan War. A poisoned apple induced Snow White’s coma. William Tell shot an apple off his young son’s head. And let’s salute early America’s apple eccentric, John Chapman, Johnny Appleseed. This pioneer spent most of his life wandering around Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana sowing apple seeds—and becoming legendary.

The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans loved apples and developed dozens of varieties, but it was ancient India’s Ayurvedic physicians who first prescribed them to relieve diarrhea. Applesauce is still a popular home remedy for diarrhea.

Traditional Chinese physicians have used apple bark for centuries to treat diabetes, another use that’s supported by modern science.

The medieval German abbess/herbalist Hildegard of Bingen prescribed raw apples as a tonic for healthy people and cooked apples as the first treatment for any sickness.

In medieval England, people said, “Eating an apple before going to bed/Makes the doctor beg his bread.” You know what this evolved into.

Seventeenth-century English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper recommended apples “for hot and bilious stomachs . . . inflammations of the breast and lungs . . . [and] asthma.” He also suggested boiled apples in milk as a treatment for gunpowder burns.

The Americas had no native apples, but the Pilgrims brought seeds, and the fruit quickly became, well, as American as apple pie. Apples, apple bark, and apple cider soon became mainstays of American folk medicine.

Speaking of apple pie, when the poor baked pies, they used only a bottom crust. Richer bakers could afford to add a top crust—hence our description of the wealthy as “upper crust.”

A century ago, American Eclectic physicians, forerunners of today’s naturopaths, had several recommendations for apples: raw for constipation, baked or stewed for minor fevers, a bark decoction for intermittent fever (malaria), and apple cider for fever.

Modern science has discovered that Johnny Appleseed’s favorite fruit has tremendous value in healing thanks to its pulp, which is high in pectin, a soluble fiber.

DIARRHEA. Pectin helps relieve diarrhea because intestinal bacteria transform it into a soothing, protective coating for the irritated intestinal lining. In addition, pectin adds bulk to the stool, which helps resolve diarrhea.

Infectious diarrhea is caused by bacteria. One study found that apple pectin is effective against several types of bacteria that cause diarrhea: Salmonella, Staphylococcus, and E. coli. In fact, pectin is the “pectate” in the over-the-counter diarrhea preparation Kaopectate.

CONSTIPATION. Physicians recommend diets high in fiber to add bulk to stool. Pectin is a type of fiber that helps resolve constipation by adding bulk and stimulating bowel contractions.

HEART DISEASE AND STROKE. A high-fiber diet helps reduce cholesterol, a key risk factor for heart disease and most strokes. With fiber in the gut, the cholesterol we eat remains in the intestine until elimination. If you have a pectin-rich, high-fiber baked apple for dessert after eating meat and dairy, you enjoy some protection from their cholesterol.

In a long-term study of 805 Dutch men, those who ate the most apples experienced the fewest heart attacks. The scientists concluded that in addition to pectin, compounds in apples called flavonoids played an important protective role. Flavonoids are antioxidants that help prevent the cell damage at the root of the arterial narrowing that triggers heart attack.

CANCER. The American Cancer Society recommends a high-fiber diet to help prevent several cancers, particularly colon cancer. A study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute shows that pectin binds cancer-causing compounds in the colon, speeding their elimination.

The antioxidant flavonoids in apples also help prevent the cell damage that causes many cancers.

DIABETES. Physicians also recommend a high-fiber diet to control diabetes. A report in Annals of Internal Medicine showed that apple pectin helps reduce blood sugar (glucose) in diabetics.

HEAVY METAL EXPOSURE. European studies suggest that apple pectin helps eliminate lead, mercury, and other toxic heavy metals from the body.

WOUNDS. Although pectin is the apple’s major medicinal component, the fruit’s leaves contain an antibiotic called phloretin. If you cut yourself out in the orchard, press apple leaves against the wound as you seek soap and water.

A few studies, including one published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, hint that pectin may help prevent cancer from spreading (metastasizing).

For first-aid for minor wounds, crush some apple leaves and apply them to the cut or scrape until you can wash and bandage it.

Eat the whole fresh fruit to enjoy a wide range of healthful benefits. Green apples tend to be tart, but they usually have more “snap.” Red apples are usually sweeter but may have a mealy texture. Wash apples with soap and water before eating to eliminate any pesticide residue.

James A. Duke, Ph.D., retired USDA herbal medicine authority (and poet), sums up apple safety this way:

An apple a day keeps the doctor away,

Or at least that’s what some people say.

But one man, we read,

Ate a cupful of seed,

And this man died.

Poisoned by cyanide.

Strange but true: Apple seeds contain cyanide, the powerful poison. About ½ cup of seeds can be deadly for the average adult, but considerably less is fatal for children and the elderly. Many parents are familiar with the stomachaches that young children develop when they eat apple cores. The few seeds in the typical core pose little risk of serious poisoning. But to be prudent, teach children not to eat apple seeds.

Archeological evidence shows that humans have enjoyed apples since 6500 BC. Prehistoric apples resembled today’s crab apples—small, dry, and mealy. But as agriculture developed, apples became one of the world’s first hybridized orchard fruits.

Today, about 300 apple varieties grow in the 50 states. Special varieties have been developed for just about all growing conditions in North America. Consult a nursery for the varieties best suited to your locale.

Full-size apple trees grow to about 40 feet and spread over 1,600 square feet (40 by 40). Genetic dwarf apple varieties produce delicious, full-size fruits but grow to only 6 to 12 feet and spread over less than 150 square feet (12 by 12).

Plant the rootstock in a sunny location and water regularly. Prune at planting, then annually. Different apple varieties have different fertilizer requirements and different pest problems. Consult a nursery.

Family: Asteraceae; other members include daisy

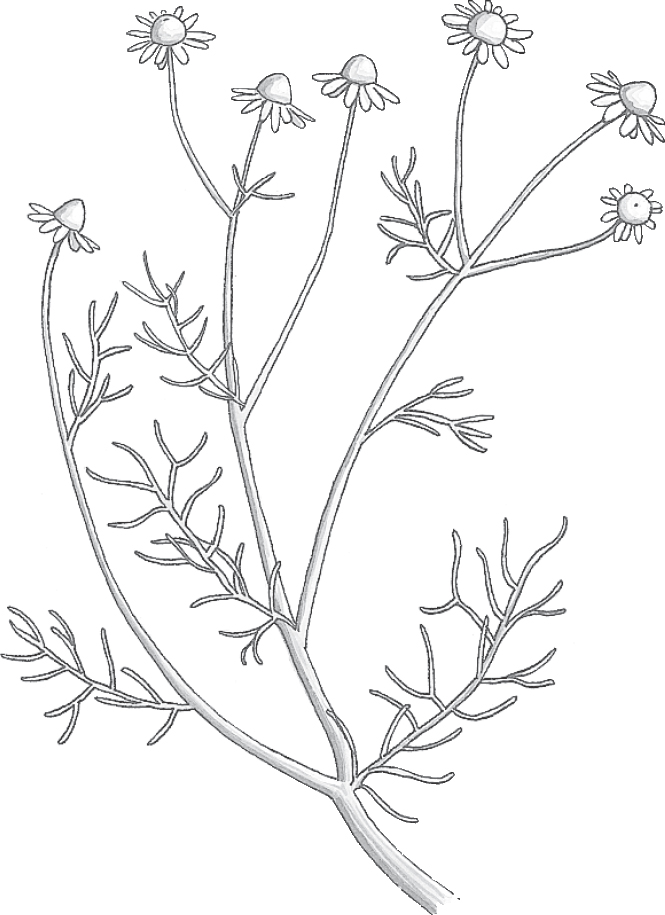

Genus and species: Arnica montana

Also known as: Mountain daisy, wolf’s bane, leopard’s bane

Parts used: Dried flower heads

Arnica is homeopathic first-aid for wounds, injuries, and muscle soreness. But mainstream physicians scoff at homeopathy in general and homeopathic arnica in particular. The studies go both ways, some showing benefit, others showing none. But the weight of the evidence tilts in favor of this mountain flower.

For centuries, European herbalists used arnica in salves and ointments as a topical treatment for injuries, bruising, and pain. They also prescribed teas and tinctures for a variety of conditions, including paralysis, menstrual problems, and typhoid.

The German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Geothe drank arnica tea to ease his chest pain (from angina). But he used a very low dose because he knew that large doses could be toxic. Even modest amounts cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Larger amounts suppress respiration, causing coma and death. As a result, America’s 19th century Eclectic physicians limited this herb to external uses to treat wounds, bruising, pain, and inflammation.

Arnica is most widely prescribed by homeopaths. Homeopathy, developed in the 1830s by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843), is controversial because its microdose medicines are so dilute that pharmacologists insist they could not possibly have any effect. Nonetheless, for reasons science cannot currently explain, many homeopathic herbal treatments, including arnica, have shown benefits in rigorous studies.

Recent studies of arnica are confusing. Some show benefit. Others do not. And results showing benefit are often barely statistically significant. Meanwhile, results showing no benefit often barely miss statistical significance of benefit. So the scientific cases for and against arnica are not very compelling. Nonetheless, the majority of studies show benefit, and in homeopathic doses, this herb is safe and inexpensive.

SURGICAL PAIN AND BRUISING. Homeopaths typically prescribe arnica for pain caused by injuries. As a result, most arnica research has focused on pain, with the herb ingested in homeopathic micro-doses or applied topically in ointments.

German researchers gave 88 people having bunion surgery either a standard drug for pain and inflammation (diclofenac, Voltaren) or homeopathic arnica (10 tiny pills three times a day). Four days after surgery, the two treatments were equally effective for bruising, swelling, and wound tenderness. Diclofenac was more effective for pain. But those taking arnica got back on their feet more quickly and comfortably. The researchers concluded: “After foot operations, arnica can be used instead of diclofenac.”

Welsh scientists gave 190 adults having tonsillectomies either a placebo or homeopathic arnica (two tiny pills six times the day after surgery, then two tiny pills a day for the next week). The arnica group reported significantly less pain.

German researchers gave 60 people having surgery to remove varicose veins either a placebo or arnica (5 tiny pills three times a day for 2 weeks). The arnica group reported significantly less bruising and pain.

Plastic surgeons in Farmington, Connecticut, gave 29 people having face-lifts either a placebo or arnica for 10 days after surgery. The arnica group experienced less bruising.

Swiss researchers gave 204 people with osteoarthritis of the hands either a standard ointment containing ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) or an arnica ointment. After 21 days, both groups reported the same relief.

MUSCLE SORENESS. Norwegian researchers tested arnica in runners in two Oslo Marathons (1990 and 1995). A total of 82 runners were given either a placebo or arnica (five tiny pills starting the evening before the races then morning and evening of race day and for 3 days after). The arnica group reported less muscle soreness.

An Australian study of 20 runners concurred, showing that arnica ointment reduced delayed-onset muscle soreness.

OSTEOARTHRITIS. Swiss researchers gave 204 people with arthritis of the fingers either ibuprofen gel or arnica tincture mixed with skin lotion. Three weeks later, both participants and their doctors rated the herb as slightly more effective with fewer side effects.

Commission E, the German counterpart of the FDA, approves arnica ointments for muscle aches, inflammation, and insect bites and stings.

Animal studies suggest that arnica may stimulate the immune system.

When using arnica ointments or homeopathic pills, follow package directions. Or consult a homeopath.

Do not ingest arnica plant material. It’s poisonous, causing nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal distress, and in high doses, coma, cardiac arrest, and death. If you grow arnica, keep the plant away from young children, and warn older children not to ingest it.

Ingest this herb only in homeopathic doses, which are too low to cause problems. Consult a homeopath for appropriate dosages for children and those over 65.

Pregnant and nursing women should not ingest arnica. Use of topical ointments is fine.

If you use this herb, inform your health professionals. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Arnica may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If unusual symptoms develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

Arnica is native to cool mountainous regions of Europe and Russia. It also grows at higher elevations in the northwest United States. Arnica is a perennial that grows to 12 inches and produces bright yellow, daisy-like flowers, hence its common name, mountain daisy. Sow seed in the spring in a mix of loam, peat moss, and sand. Arnica likes acid pH, full sun, moisture, and high altitude. The flowers smell unpleasant, but the odor subsides as they dry. Pulverize dried flowers and make a tincture. Mix some tincture with hand lotion or skin cream for a topical ointment.

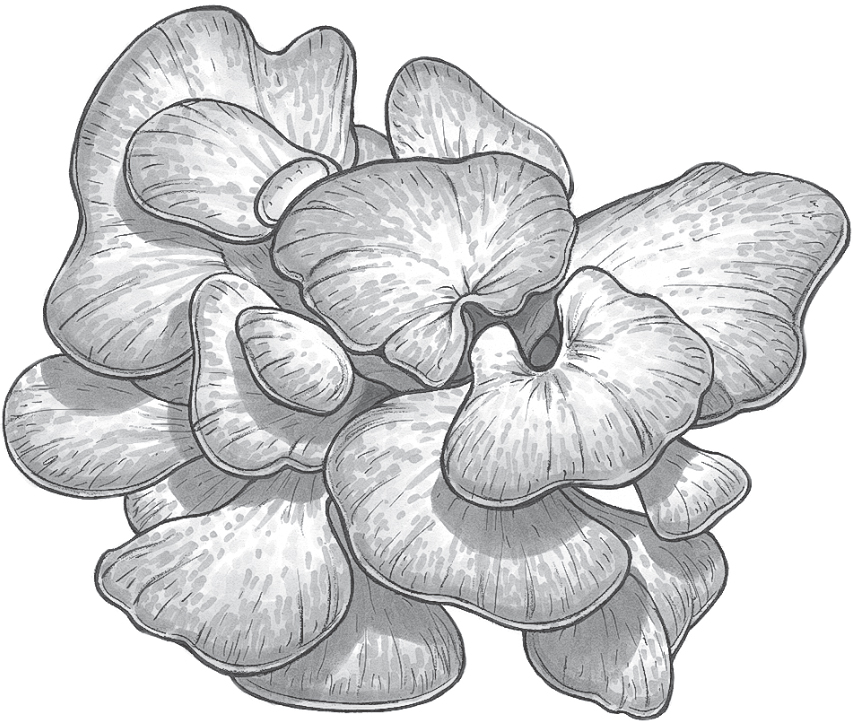

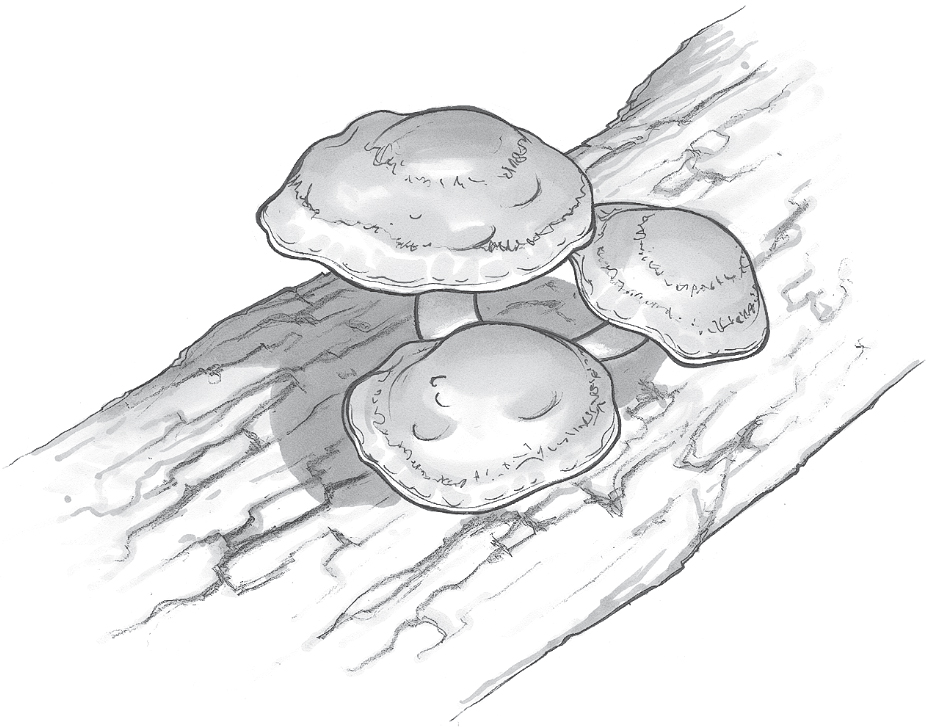

Family: Compositae or Asteraceae; other members include thistle

Genus and species: Cynarae scolymus

Also known as: Garden artichoke, globe artichoke

Parts used: The flower and lower portions of the barbed scales that enclose it

What’s the best herb for preventing and treating liver problems? If you’re familiar with herbal medicine, you know it’s milk thistle. But artichoke, a close botanical relative of milk thistle, is almost as beneficial. Its species name, scolymus, derives from the Greek for thistle. In traditional European herbal medicine, the two plants were used almost interchangeably. In addition, artichoke also soothes the stomach, lowers cholesterol, and treats irritable bowel syndrome.

Around 300 B.C, the ancient Greek naturalist, Theophrastus, described a plant native to Sicily. He called it scolymus, now artichoke’s species name: “The head [flower bud] is most pleasant, being boiled.” Theophrastus’ scolymus was wild artichoke, or cardoon (Cynara cardunculus). Ancient farmers cultivated it and bred it, selecting for larger flower buds. By the Middle Ages, they had produced today’s globe artichokes—which continued to be called cardoons (or car-done, cardoni, carduni or cardi) until the 19th century.

Around the ancient Mediterranean, herbalists used artichoke/cardoon as both a food and medicine. As a food, it was considered a delicacy. As a medicine, the flower and the plant’s juice were used to promote digestion and treat upset stomach and liver problems (jaundice).

One type of artichoke, blessed thistle, was so popular in 17th-century England that in his Complete Herbal (1652), the noted English herbalist, Nicholas Culpeper, wrote: “I shall spare the labour of writing a description as almost everyone may describe them from their own knowledge.” Culpeper called blessed thistle “an excellent remedy” for jaundice and gallbladder problems and recommended it for plague, boils, and “the bites of mad dogs and venomous beasts.” He also said it “cures the French pox,” that is, syphilis.

In France, for centuries artichoke juice has been a traditional liver tonic.

America’s 19th century Eclectic physicians recommended artichoke for liver disease, gout, and muscle aches (rheumatism). They also considered artichoke juice an aphrodisiac.

LIVER PROBLEMS. Like milk thistle, artichoke has considerable antioxidant action that spurs regeneration of liver cells. Several studies show that in animals treated with liver-toxic chemicals, artichoke minimizes liver damage and increases survival.

INDIGESTION. German researchers gave 244 adults with chronic indigestion either a placebo or artichoke extract (640 mg twice a day). After 6 weeks, the artichoke group reported significantly greater relief and improved quality of life. In a similar study, British scientist reported the same findings.

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS). This common condition causes chronic digestive problems: abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, and diarrhea or constipation. Because artichoke helps treat indigestion, British researchers thought it might also alleviate IBS. They gave 208 adult IBS sufferers either a placebo or artichoke extract (320 or 640 milligrams/day). Two months later, the artichoke group reported 41 percent greater relief.

CHOLESTEROL. Several studies show that artichoke lowers cholesterol. In one trial, German researchers gave people with high cholesterol either a placebo or artichoke extract (450 milligrams/day). After 6 weeks, the placebo group’s total cholesterol fell 9 percent, but in the artichoke group, it dropped twice as much, 19 percent. For every 1 percent decrease in total cholesterol, heart attack risk drops 2 percent. So thanks to artichoke, participants’ risk of heart attack decreased 38 percent. The researchers called their findings “clear evidence for recommending artichoke” as a treatment for high cholesterol.

Italian scientists gave 92 adults with high cholesterol either a placebo or artichoke leaf extract (250 milligrams/day). After 8 weeks, the placebo group showed no increase in HDL (good cholesterol), but among the artichoke takers, HDL increased significantly.

ATHEROSCLEROSIS. Often called hardening of the arteries, atherosclerosis involves the development of cholesterol-rich deposits on artery walls that limit blood circulation and raise risk of heart disease and stroke. An Italian study shows that artichoke juice (1 cup a day) helps prevent atherosclerosis.

ANTIMICROBIAL. Artichoke inhibits the activity of several bacteria and fungi.

DIGESTIVE SUPPORT. Commission E, the German counterpart of the FDA, notes that artichoke increases bile flow, which helps digest fats. The Commission approves fresh artichoke, its leaf extract, and juice for indigestion.

Pilot studies suggest that artichoke may have some pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory action.

The herb may also reduce blood sugar and help manage diabetes.

And one study shows that when male laboratory animals are exposed to chemicals that damage testicular tissue, artichoke treatment minimizes the damage.

Some folk medical traditions recommend artichokes for hangover. British researchers gave 15 adults either artichoke extract (three standard capsules) or a placebo immediately after drinking sufficient alcohol to cause intoxication and hangover. One week later, the treatments were switched (a cross-over trial). The artichoke group took the placebo and vice versa. There were no differences in hangover duration or discomfort between the artichoke and placebo groups. Artichoke does not reduce hangover.

Artichoke extract is available at health food stores or on the Internet. But why buy extract when artichokes themselves are cheaper? Steam the delicious vegetable for 30 to 45 minutes. Pull off the outer scales. Dip the inner scales in butter, yogurt, or mustard and eat the fleshy base. When you get down to the flower, remove the immature scales and central hairs, and eat the heart.

Frequent contact with artichoke may cause allergic reactions, notably skin irritation or hives.

Commission E warns that people with gallstones or obstructed bile ducts should consult a physician before using artichoke medicinally.

Don’t confuse this plant with Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthis tuberosus), a species of sunflower.

Artichoke is a perennial that grows to 6 feet and 4 feet wide. Flower buds (heads) appear in July in the Southern United States, or in August in the Northern United States and Canada.

Growing requires 100 frost-free days a year. Soil should be rich with compost and manure and well drained. Artichokes like slightly acid soil (pH 6.0). Seeds can be started indoors in early spring and transplanted after the last frost. Watering encourages large artichokes.

Replace some older plants each year. Take suckers or side roots from your healthiest plants to propagate.

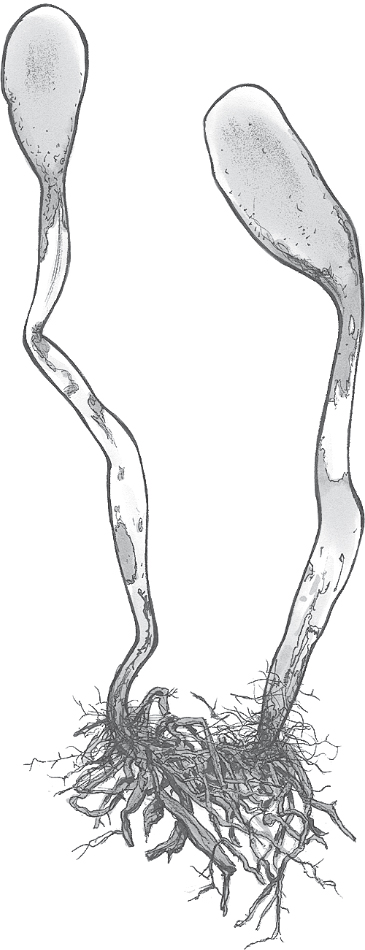

Family: Solanaceae; other members include tomato, potato, and bell peppers

Genus and species: Withania somnifera

Also known as: Withania, Indian ginseng, winter cherry, dunal

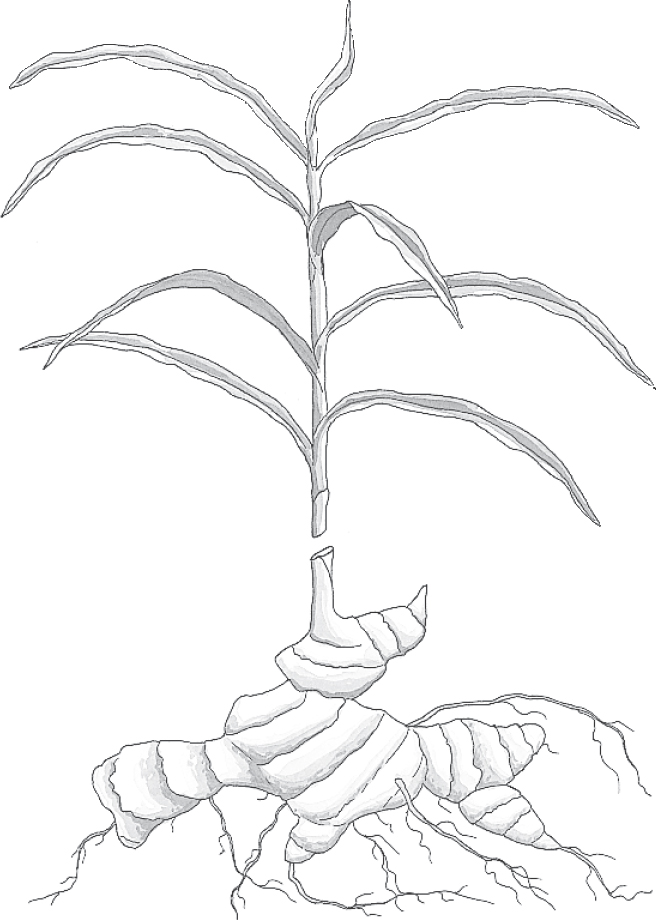

Parts used: Root

Ashwagandha (ash-wah-GAHN-da) derives from two Sanskrit words—ashwa meaning horse, and gandha for essence, that is, the herb makes users as strong as horses. That’s an exaggeration, but recent studies show that it does improve muscle strength.

Ashwagandha is not related to ginseng but it’s often called “Indian ginseng” because its effects are similar to the Chinese herb. It’s an “adaptogen” that strengthens the whole body, treating fatigue, weakness, debility, and many age-related conditions.

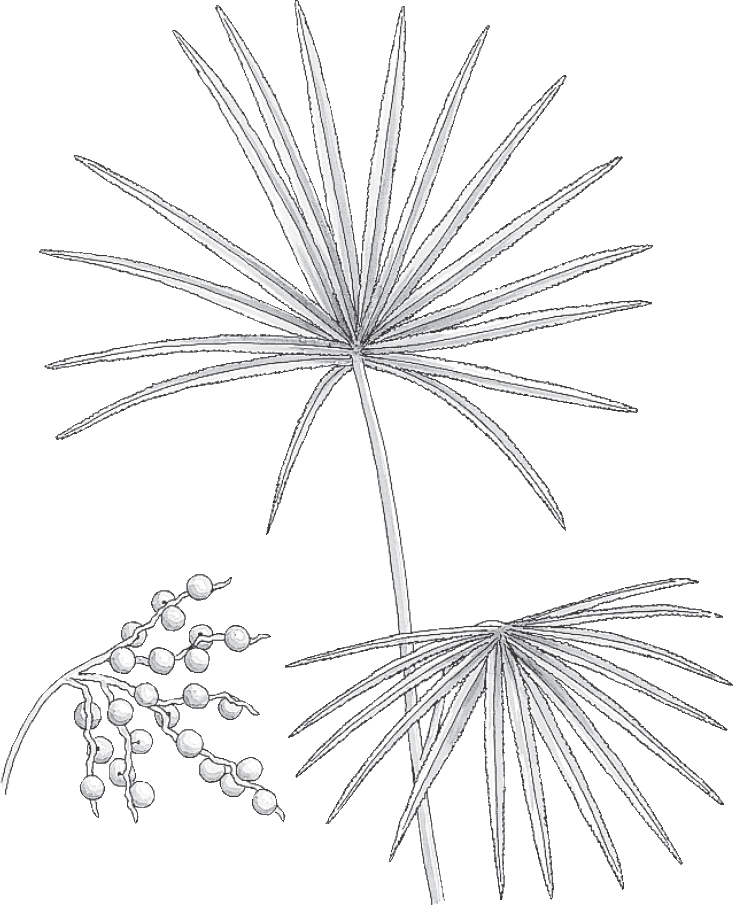

Ashwagandha is a small evergreen shrub native to India. It also grows in the Middle East and East Africa. Its small, smooth, round, fleshy fruit contains many seeds and turns reddish-orange when ripe, hence the name winter cherry.

Ashwagandha has been revered in India’s traditional Ayurvedic medicine for 3,000 years. It’s discussed in several ancient Ayurvedic medical texts, including the Charaka, which recommends it as a whole-body tonic, particularly for those suffering from debility and for enhancing reproductive function and longevity. Ayurvedic physicians prescribe it to treat arthritis, muscle aches, inflammations, conditions associated with aging, and insomnia, hence its species name somnifera.

Like ginseng and rhodiola, Chinese and Ayurvedic physicians consider ashwagandha a “tonic” or adaptogen, meaning whole body strengthener. The term adaptogen was coined in 1947 by Russian scientist, N. V. Lazarev, who was interested in drugs that helped the body overcome physical and emotional stress. His student Israel I. Brekhman popularized the term and showed that the most powerful adaptogens are not drugs, but herbs. Lazarev and Brekhman believed that adaptogens should:

• Counteract the adverse effects of stress.

• Increase energy.

• Increase the body’s resistance to a broad range of adverse influences.

• Have a normalizing effect, improving many conditions while aggravating none.

• Cause minimal side effects.

Since Brekhman’s death in 1994, the term adaptogen has been generalized to include herbs that don’t necessarily boost energy or counteract stress, but have a number of benefits including enhanced immune function, antioxidant action, and physiological normalization.

Unfortunately, in America, “tonics” are suspect. Many 19th century patent medicines sold as “rejuvenating tonics” contained mostly alcohol and/or opium. In addition, most Americans believe that individual drugs treat just one problem, maybe two. We’re not used to the idea that one drug—or herb—can produce a broad range of physical and mental health benefits. But animal studies show that ashwagandha produces several: immune stimulation, heart protection, improved stamina, and greater resistance to the physiological damage caused by stress.

Human trials agree.

STRESS AND ANXIETY PROTECTION. Indian scientists gave 130 adults either a placebo or ashwagandha (500 milligrams/day). After a year, the herb group showed significantly less anxiety and improved well-being.

Researchers at SUNY Upstate Medical Center in New York analyzed five studies of ashwagandha as a treatment for stress/anxiety. In all five, a total of 400 participants showed significant benefit, reduced stress and anxiety. And ashwagandha caused fewer side effects than pharmaceutical tranquilizers.

BLOOD PRESSURE. Indian scientists gave 20 young adult men either a placebo or ashwagandha (1,000 milligrams/day). After 2 weeks, the groups switched treatments. When taking the herb, participants’ blood pressure declined significantly. Blood levels of the stress hormone, cortisol, also fell.

CHOLESTEROL. Indian researchers gave ashwagandha daily to diabetics with high cholesterol. After a month, their cholesterol levels dropped significantly.

DIABETES. In the cholesterol study just mentioned, the diabetics’ blood sugar levels also declined. The decrease “was comparable to that produced by oral diabetes medication.”

FATIGUE. Malaysian researchers gave either a placebo or ashwagandha (2,000 milligrams four times a day) to 100 women suffering fatigue from cancer chemotherapy. After 6 months, the placebo group reported slightly less fatigue, but those taking ashwagandha reported much less—plus better appetite, less insomnia, pain, and constipation and greater well-being and quality of life.

REACTION TIME. Indian researchers gave 20 men, age 20 to 35, either a placebo or ashwagandha (1,000 milligrams/day). After 2 weeks, they registered significantly speedier reaction times.

STRENGTH. Indian scientists gave ashwagandha (750 to 1,250 milligrams root extract/day) to 18 young adults. After a month, their handgrip strength and stamina increased significantly. Other Indian researchers conducted a similar study in children (2,000 milligrams/day). Two months later, they also registered significantly increased grip strength.

INFERTILITY. Indian researchers gave ashwagandha (5 grams of powdered root/day) to 180 infertile men and 50 with normal fertility. After 3 months, the control group showed no fertility changes, but those taking the herb showed improvements: higher sperm counts and improved sperm motility with fewer deformed sperm.

ADAPTOGEN. After taking ashwagandha for a year, Indian men showed reduced cholesterol, more red blood cells, and enhanced sexual function.

Ashwagandha appears to have some antidepressant action. It may also protect against seizures and loss of cognitive function due to toxic chemicals.

The recommended dose is 1 to 6 grams/day (2 to 12 teaspoons) in capsules or tea. In tincture or liquid extract, use 2 to 4 milliliters 3 times/day.

Very high doses of ashwagandha may cause stomach upset, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, dulling of reflexes, and loss of motor abilities.

Large doses may trigger abortion. Pregnant and nursing women should not use ashwagandha.

Do not give ashwagandha to children under 2. In older children, adjust the recommended dose based on the child’s weight. Give a 50-pound child one-third of the dose a 150-pound adult would take.

If you’re over 65, start with a low dose, and increase only if necessary.

If you use this herb, inform your health professionals. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Ashwagandha may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If unusual symptoms develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

Ashwagandha grows primarily in dry, subtropical areas of India to an elevation of about 5,000 feet. It also grows from Pakistan to Egypt, and in Spain, Morocco, the Canary Islands, and South Africa. In the United States, it can be grown in the South and Southwest. The plant is an erect shrub that in the wild grows to 3 feet, but cultivated plants grow larger.

Keep seeds moist but not too wet. They germinate within 2 weeks at 70°F. This herb prefers full sun and sandy soil. Harvest the fruit in the fall. Dry the bright yellow seeds for planting the following spring. Harvest the medicinal root in the fall after the first frost. Roots are either dried whole or cut into pieces and dried.

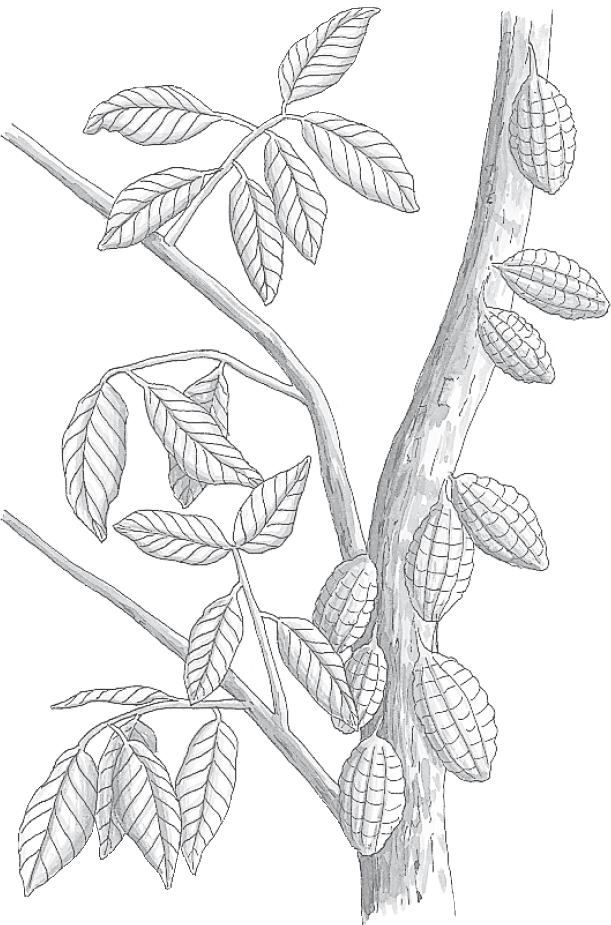

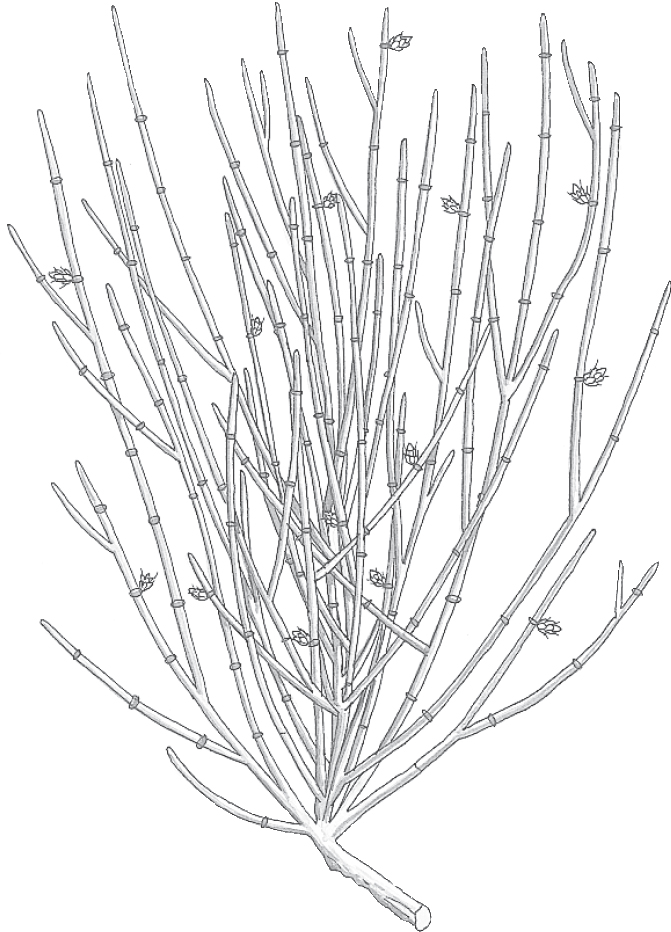

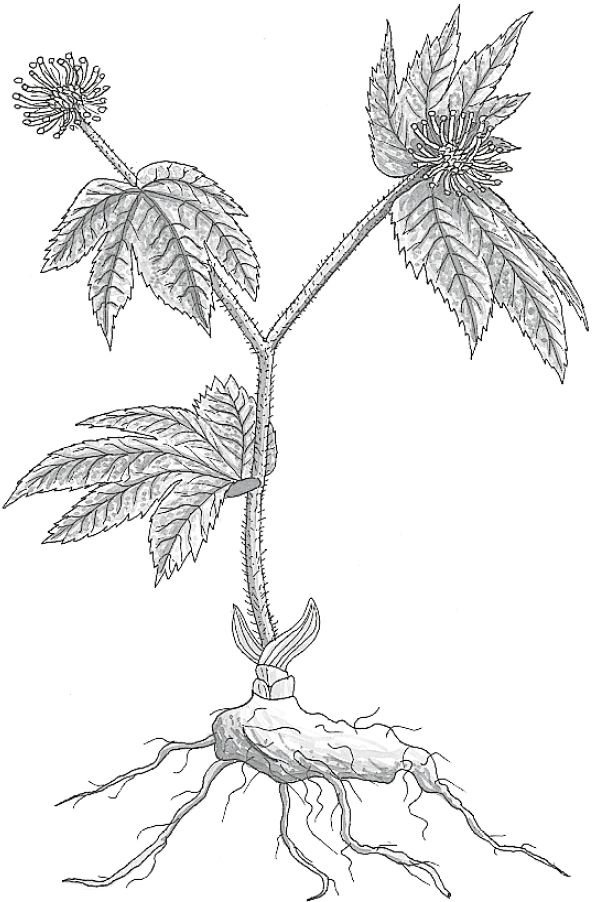

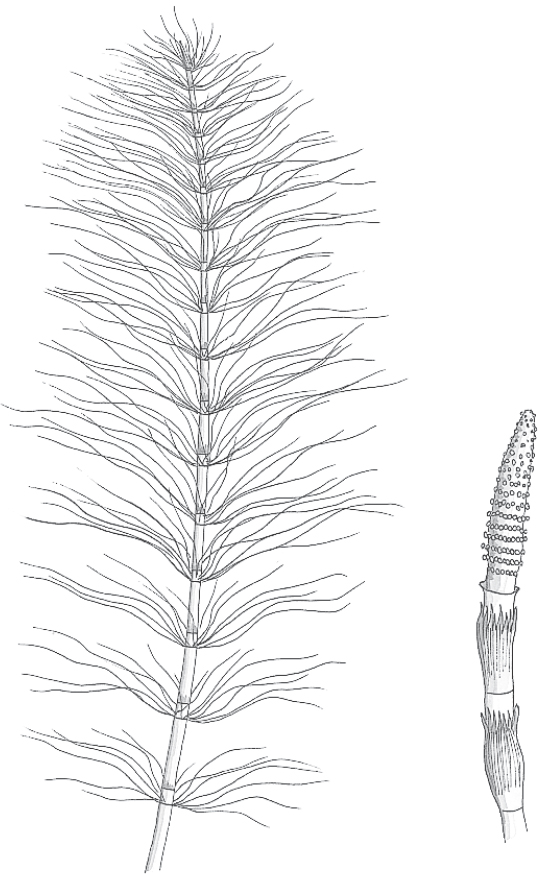

Family: Leguminosae; other members include beans and peas

Genus and species: Astragalus membranaceus

Also known as: Huang qi, yellow leader, and milk vetch

Parts used: Roots

The Chinese refer to astragalus as huang qi, meaning “strengthener of qi.” Qi (or chi) is the Chinese term for life force, vitality, stamina, disease resistance, and the ability to cope with stress. As a strengthener of qi, astragalus is powerful medicine.

Chinese herbalists have prescribed astragalus for 2,000 years. Today practitioners of Chinese medicine believe the herb strengthens all body systems and is particularly effective for treating illnesses that cause fatigue. They consider it similar to ginseng, and they prescribe it for diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure.

Western scientists have begun to study astragalus only recently, so there are still more questions than answers about the herb’s effects. However, research to date confirms traditional Chinese claims.

ENHANCED IMMUNITY. The first Western study of astragalus took place in 1983 at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The herb improved immune function in 19 cancer patients who were being treated with immune-suppressing chemotherapy drugs.

Since then, several studies—animal and human—have shown that astragalus, administered either orally or by injection, improves immune function. In one animal study, astragalus improved the germ-devouring ability of macrophages, infection-fighting white blood cells. In another, astragalus boosted the infection-fighting ability of T-cells, another type of white blood cell.

In a Chinese study, doctors administered astragalus extract (injections of 8 grams/day) to 10 people with viral heart infections and depressed immune systems. Their immune function improved significantly.

In another Chinese study, 235 women with various chronic viral infections, among them herpes, were treated with immune-boosting interferon and/or astragalus. The herb by itself did not provide much benefit. But astragalus plus interferon produced the greatest antiviral benefit.

HEART DISEASE. Chinese researchers gave astragalus to 92 people with angina, a form of heart disease. The herb reduced chest pain in 83 percent. In another Chinese study, compared with heart attack sufferers who did not take the herb, those treated with astragalus showed significantly improved heart function.

LIVER DAMAGE. Chinese researchers gave 208 people with chronic hepatitis B, average age 38, either a placebo or an herbal formula that was primarily astragalus (dose not specified, three times a day). After 2 months, the herb users showed significantly improved liver function.

CHRONIC FATIGUE. Korean scientists gave a placebo or a combination of astragalus and Chinese sage (3 to 6 grams/day). A month later, the placebo group showed scant change but the herb takers showed significantly less fatigue.

HAY FEVER. Croatian researchers catalogued the allergy symptoms of 41 hay fever sufferers, then gave them either a placebo or astragalus (160 milligrams twice daily). After six weeks the herb group showed significantly less sneezing, itchy eyes, and runny nose—with no side effects.

Chinese studies suggest that astragalus improves sperm motility, reduces blood pressure, and enhances immune function in people infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

In China, growers peel and dry carrot-like astragalus roots. They cut roots into long slices that resemble popsicle sticks. When using dried roots, finely chop four or five and simmer them in 4 cups of boiling water for 1 hour. Drink 1 cup in the morning and 1 cup in the evening. Astragalus tastes mildly sweet, but you may prefer it blended with other beverage herbs.

Astragalus is also available in a variety of commercial preparations, including tinctures, capsules, and tablets. Follow package directions.

When used as recommended, astragalus is generally considered safe. One laboratory test, however, found that a strong decoction caused chromosome mutations, a hint that the herb might be carcinogenic. Traditional Chinese herbalists recommend using astragalus for only a few weeks during an illness, and not routinely. This would be prudent advice if mutagenicity is confirmed.

Chinese practitioners advise against taking astragalus for acute infections; instead, they recommend reserving it to strengthen the body after it has begun to heal.

Pregnant and nursing women should not use astragalus.

Do not give astragalus to children under 2. In older children, adjust the recommended dose based on the child’s weight. Give a 50-pound child one-third of the dose a 150-pound adult would take.

If you’re over 65, start with a low dose, and increase only if necessary.

Inform health professionals of the herbs you use. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Astragalus may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If any develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

Astragalus is a perennial plant native to northern China and Mongolia that produces small yellow flowers. Its thick root has a tough fibrous skin with a yellowish interior, which is the medicinal part. The root has a sweetish, licorice-like taste. Astragalus is not grown in the United States.

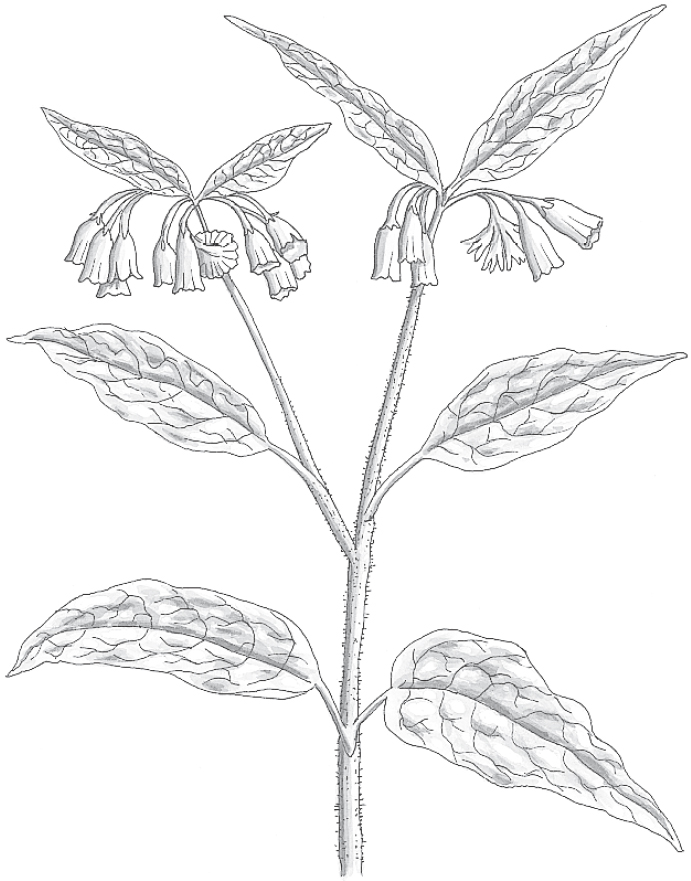

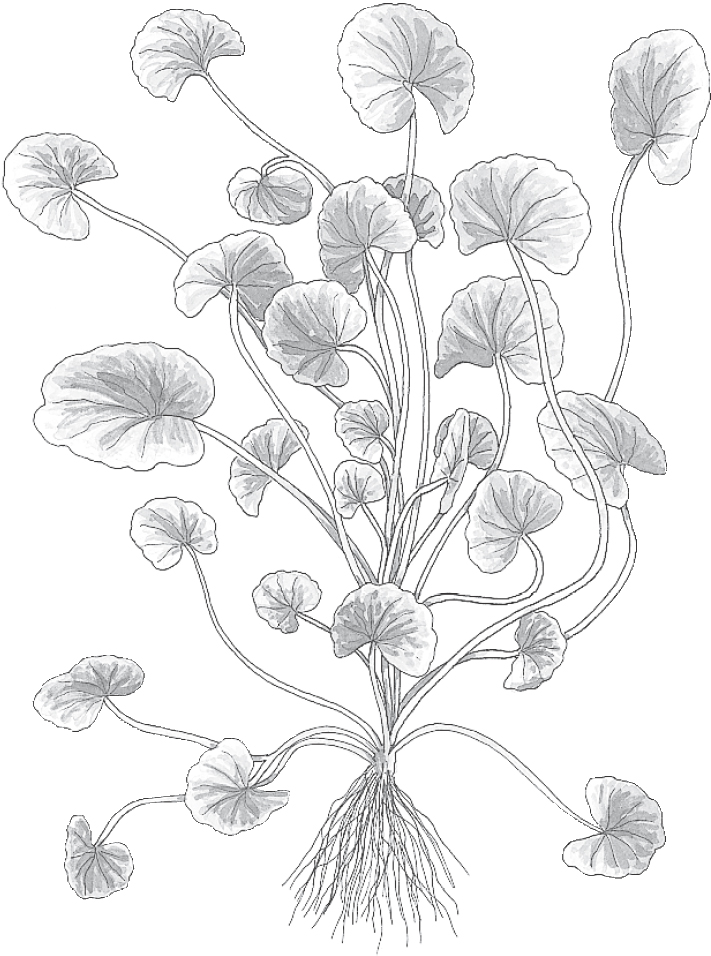

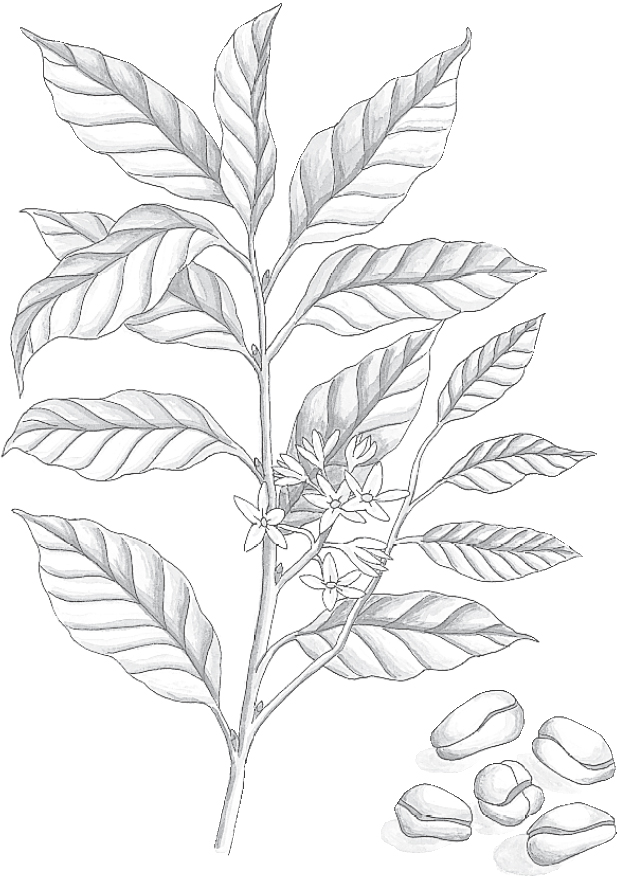

Family: Scrophulariaceae; other members include snapdragon

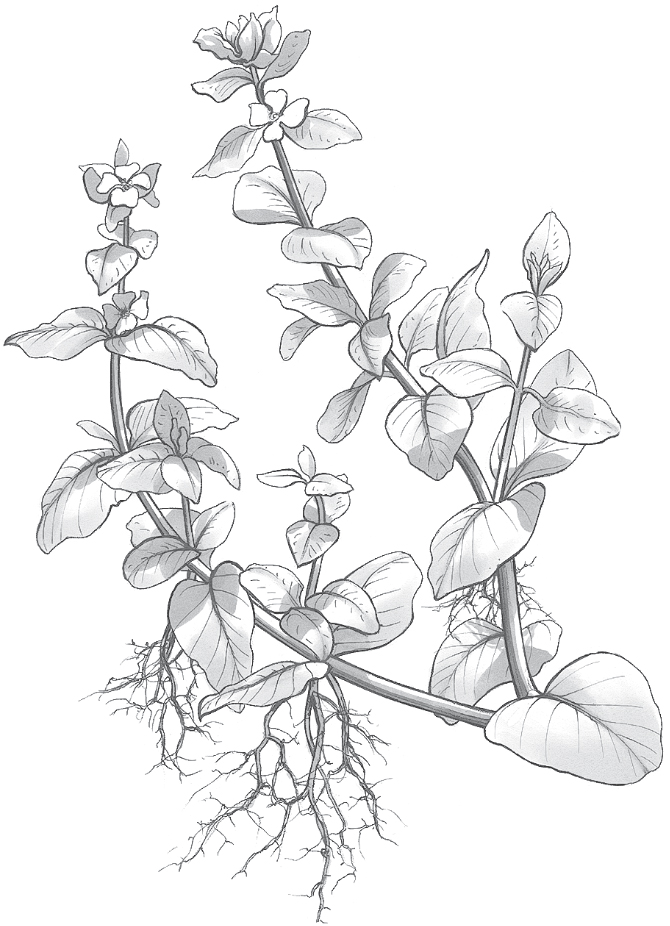

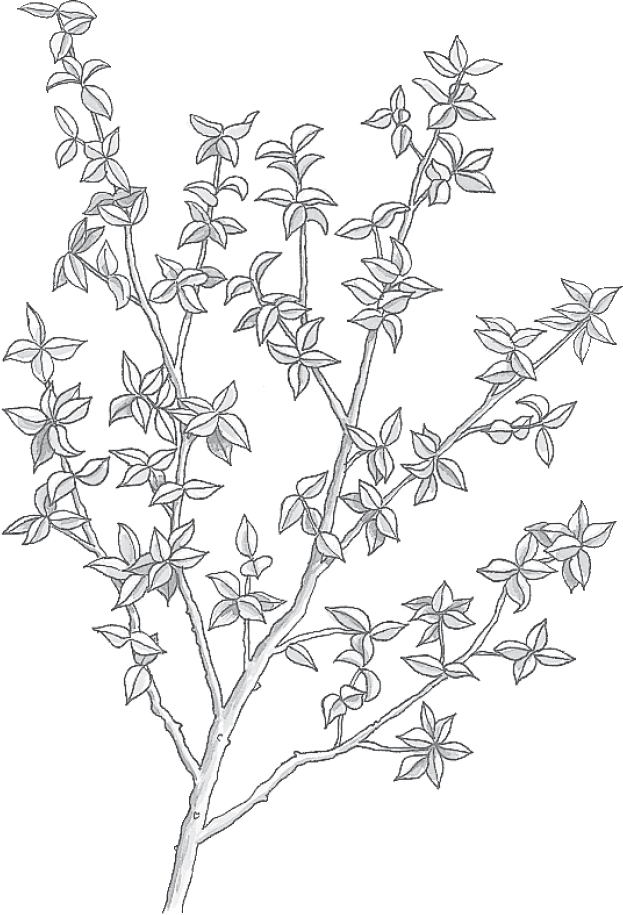

Genus and species: Bacopa monnieri

Also known as: Brahmi, water hyssop

Parts used: Whole plant

Bacopa is an age-old Ayurvedic remedy for the nervous system. Another Ayurvedic herb, gotu kola has been used similarly. As a result, both of these herbs share the Sanskrit name, brahmi, meaning “expands consciousness.” To avoid mixing up the two plants, most herbalists have stopped using the term, brahmi, and refer to these herbs as bacopa and gotu kola.

Over the centuries, India’s traditional Ayurvedic physicians have prescribed bacopa to aid learning, memory, and concentration. It was also recommended to treat anxiety, seizures, and mental illness. Modern research has shown that bacopa offers so many health benefits that Indian researchers consider it an “adaptogen” like ginseng, ashwagandha, or rhodiola—an herb that enhances total well-being.

LEARNING, MEMORY, CONCENTRATION. Contemporary research has confirmed bacopa’s brain-boosting power. The herb contains compounds, bacosides, that improve nerve impulse transmission. As early as 1966, a study showed that bacopa increases learning-related neurotransmitter levels in the brain. Since then many animal studies and clinical trials have shown that it’s a brain booster.

In several studies, Australian and Indian researchers gave middle-aged adults standard cognitive function tests, and then either a placebo or bacopa (300 milligrams/day). In one study, after 5 weeks, the herb improved learning and other measures of mental acuity. In another, after 12 weeks, the bacopa group showed significant improvement in learning and memory consolidation.

Australian scientists analyzed six rigorous studies of bacopa for memory enhancement. Bacopa did not produce miracles, but it aided recall.

Researchers at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland gave standard tests of memory and learning to 48 elderly men, average age 74. Then participants took either a placebo or bacopa (300 milligrams/day). Three months later, retesting showed no change in the placebo group, but significantly improved results in those who used bacopa.

Another Indian report shows that 3 to 9 months of daily bacopa improve children’s IQs.

To improve cognitive function, herbalists generally say it takes several weeks of daily bacopa use. But in good news for students cramming for exams, an Australian report suggests that even one dose may help. Researchers gave 24 adults, ages 18 to 56, cognitive function tests and then a placebo or one dose of bacopa (320 milligrams). Re-testing showed that bacopa improved ability to do math in one’s head. So, students, one dose of bacopa doesn’t guarantee an A, but it may help.

ATTENTION DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD). Indian psychiatrists gave 36 children with ADHD either a placebo or bacopa (50 milligrams twice a day). After 12 weeks, the herb group showed improvement in memory and learning.

ANXIETY. In one Indian study, 35 people suffering severe anxiety took large doses of bacopa (12 grams/day). After 2 weeks, they were significantly less anxious.

Oregon and Australian scientists gave 48 elderly folks a placebo or bacopa (300 milligrams). After 12 weeks, the placebo takers showed increased anxiety, but the bacopa group showed less.

ANTIOXIDANT. How do the bacosides in bacopa boost brain power? They have antioxidant action. Antioxidants prevent or reverse the cell damage caused by highly reactive oxygen ions (free radicals). Antioxidants usually reduce risk of heart disease and cancer without affecting mental acuity. But for reasons that remain unclear, bacosides appear to focus their antioxidant action on the parts of the brain involved in reasoning and memory, the frontal cortex and hippocampus.

LIVER PROTECTION. The antioxidants in bacopa protect the liver from drug-induced damage.

HYPOTHYROIDISM. Bacopa also stimulates production of thyroid hormone, suggesting value in treating hypothyroidism.

INFLAMMATION. Bacopa has anti-inflammatory action. One study suggests it’s as effective as the standard nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), indomethacin (Indocin), but without the stomach upset common with NSAIDs.

Traditional Ayurvedic physicians used bacopa to treat epileptic seizures. Animal studies show it has anticonvulsant action—but only at very high doses.

In animal studies, bacopa opens the airway into the lungs (bronchodilator). As a result it may help treat bronchitis and asthma.

Pilot studies suggest that bacopa relaxes the digestive tract and may prove beneficial for indigestion and irritable bowel syndrome. Bacopa also appears to suppress Helicobacter pylori, the bacteria that causes ulcers.

Finally, in laboratory studies, the herb has been shown to inhibit growth of some cancers.

The traditional adult dose is 5 to 10 grams of powdered herb/day in divided doses; or 5 to 12 milliliters/day of fluid extract; or 200 to 400 milligrams/day of bacopa extracts standardized to 20 percent bacosides. Follow package directions.

At recommended doses, bacopa causes no known side effects. But at unusually high doses, it becomes a sedative.

Pregnant and nursing women should not use bacopa.

Do not give bacopa to children under 2. In older children, adjust the recommended dose based on the child’s weight. Give a 50-pound child one-third of the dose a 150-pound adult would take.

If you’re over 65, start with a low dose, and increase only if necessary.

Inform health professionals of the herbs you use. Problematic herb-drug interactions are possible.

Bacopa may cause allergic reactions or other unexpected side effects. If any develop, reduce your dose or stop taking it. For more on herb safety, see Chapter 2.

If symptoms get worse or persist longer than 2 weeks, consult a health professional promptly.

Bacopa is a hardy, creeping, succulent-like, perennial ground cover with small oblong leaves and white or purple flowers. It likes marshy soil and can be grown in temperate or warmer areas at elevations to 4,500 feet with adequate water. Water frequently.

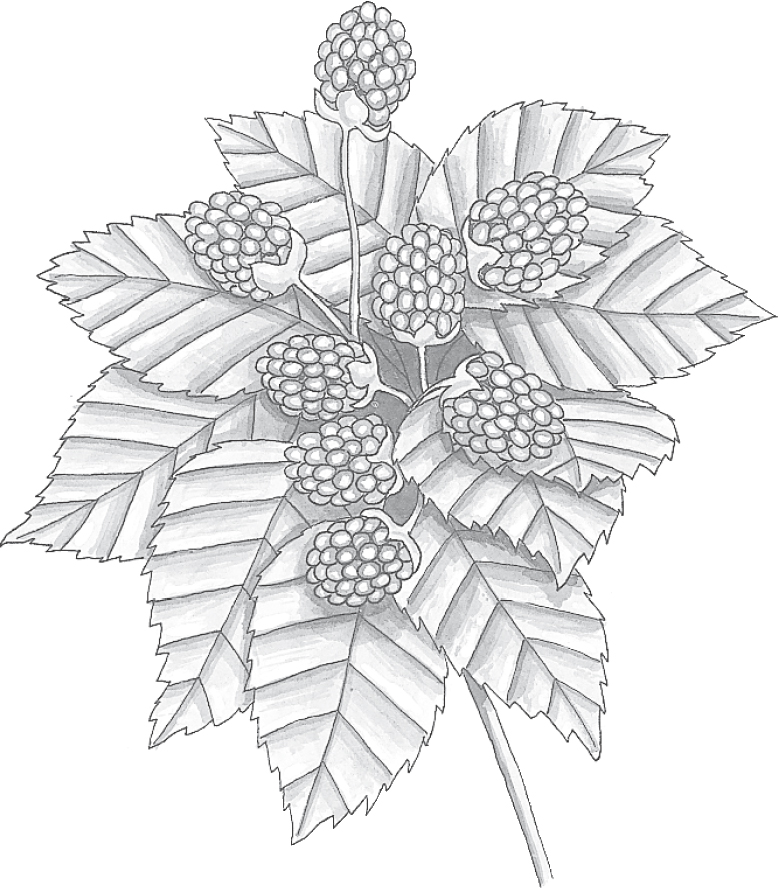

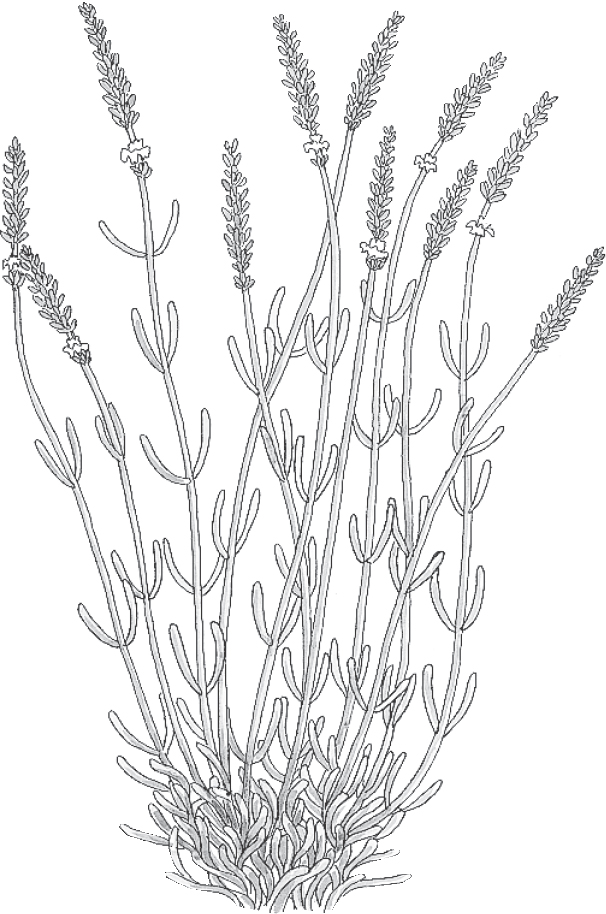

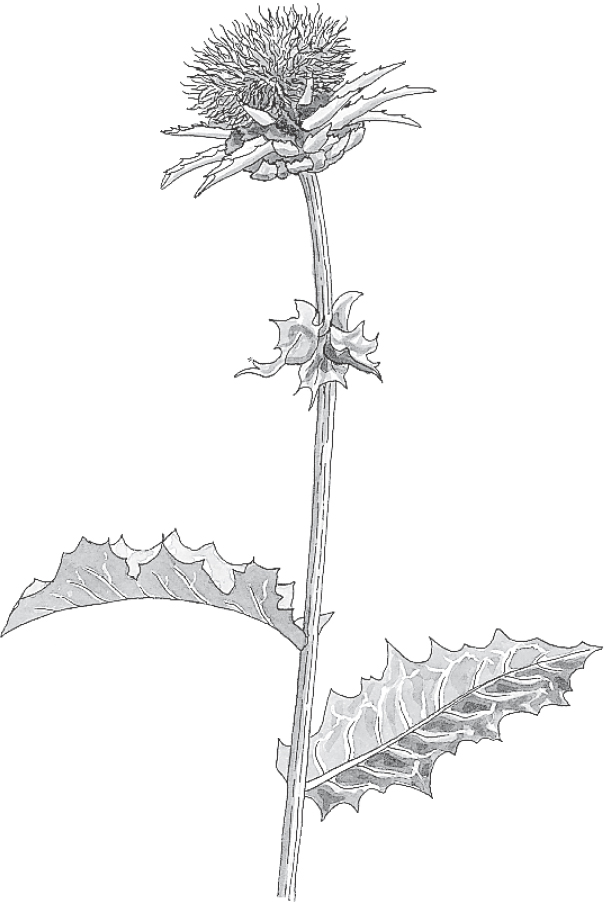

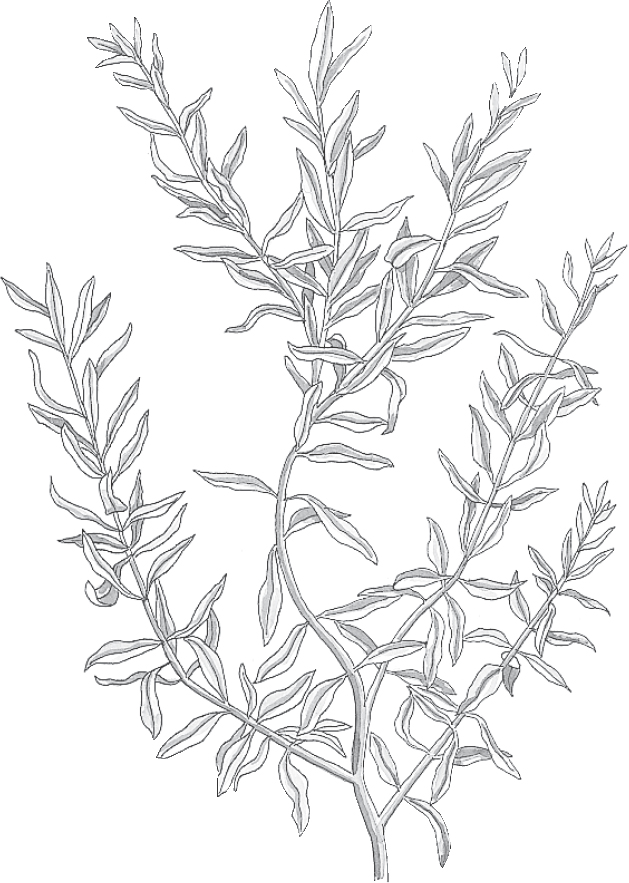

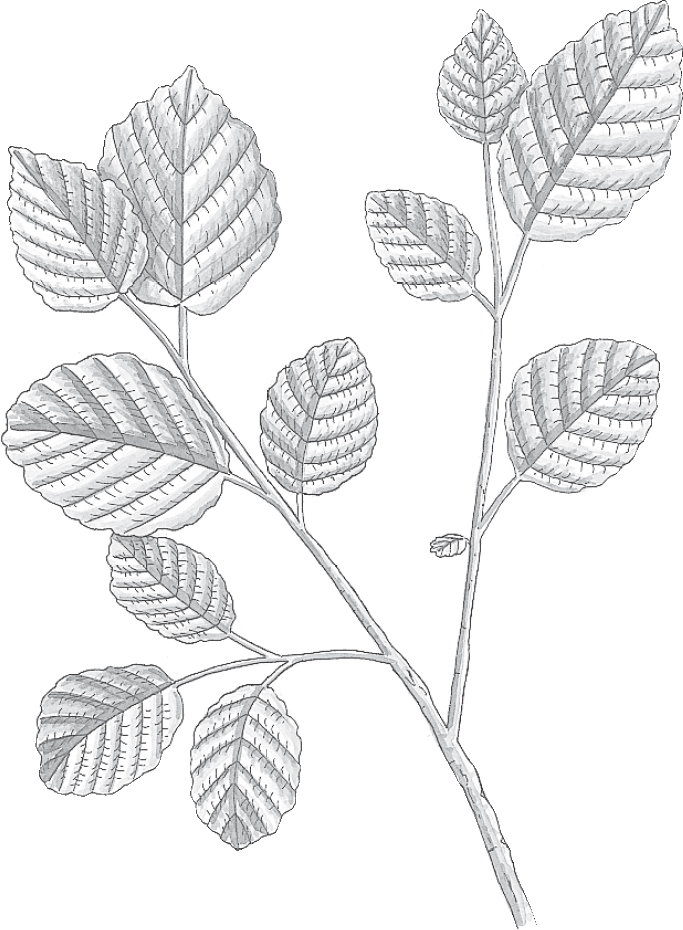

Family: Berbericlaceae; other members include May apple, mandrake, and blue cohosh

Genus and species: Berberis vulgaris; Oregon grape: B. aquifolium or Mahonia aquifolium

Also known as: Berberry, berberis, and jaundice berry

Part used: Root

Who says herbs can’t compete with pharmaceutical drugs? In one study, berberine, the active constituent in barberry, proved more potent against bacteria than chloramphenicol, a powerful pharmaceutical antibiotic.

But there’s a lot more to this herb than infection treatment. Barberry, and its close relative, Oregon grape, may also stimulate the immune system, reduce blood pressure, and even shrink some tumors.

Barberry has been a prominent herbal healer for more than 2,500 years. The ancient Egyptians used it to prevent plague, probably effectively considering the herb’s antibiotic action. India’s traditional Ayurvedic healers prescribed barberry for dysentery, another use that’s been scientifically confirmed.

During the early Middle Ages, European herbalists were guided by the Doctrine of Signatures, the belief that a plant’s physical appearance revealed its therapeutic benefits. Barberry has yellow flowers, and its roots produce a yellow dye. These features were linked to the yellowing of the skin and eyes of jaundice, a symptom of liver disease. As a result, barberry was widely used to treat liver and gallbladder ailments, earning the name jaundice berry.

Traditional Russian healers recommended it for skin inflammations, high blood pressure, and abnormal uterine bleeding.

When colonists introduced barberry into North America, the Native Americans recognized it as a relative of the native Oregon grape, a holly-like plant that they considered a powerful healer. Many tribes adopted barberry and used it to treat dysentery, mouth ulcers, sore throat, wound infections, and intestinal complaints.

The 19th-century American Eclectic physicians, forerunners of today’s naturopaths, prescribed barberry as a purgative and treatment for jaundice, dysentery, eye infections, cholera, fevers, and “impurities of the blood,” a euphemism for syphilis.

Barberry was also an ingredient in the popular but highly controversial Hoxsey Cancer Formula, an alternative cancer therapy marketed from the 1930s to the 1950s by ex-coal miner Harry Hoxsey.

Most contemporary herbalists limit their recommendations to gargling barberry decoction for a sore throat and drinking infusions for diarrhea and constipation. Actually, it’s useful for much more.

INFECTIONS. The berberine in barberry has remarkable infection-fighting properties. Studies around the world show that it kills microorganisms that cause wound infections (Staphylococcus and Streptococcus), diarrhea (Salmonella and Shigella), dysentery (Entamoeba histolytica), cholera (Vibrio cholerae), giardiasis (Giardia lamblia), urinary tract infections (Escherichia coli), and vaginal yeast infections (Candida albicans).

ENHANCED IMMUNITY. In addition to antibiotic action, berberine also stimulates the immune system. It activates macrophages (literally, “big eaters”), the white blood cells that devour harmful microorganisms.

LIVER DAMAGE. Score one for the Doctrine of Signatures and “jaundice berry.” Pakistani researchers gave laboratory animals large doses of acetaminophen to produce liver damage, signified by increased blood levels of liver enzymes. Then some animals were treated with barberry. Their enzymes declined, showing significant normalization of liver function. The researchers concluded, “This study provides a scientific basis for the traditional use of barberry in liver disorders.”

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE. Barberry contains compounds that enlarge (dilate) blood vessels. This lends support to the herb’s traditional Russian use as a treatment for high blood pressure.

CHOLESTEROL. A Chinese analysis of 11 studies involving 874 participants showed that berberine (1 to 1.5 grams/day for 8 to 16 weeks) significantly reduced cholesterol.

DIABETES. Chinese scientists in Shanghai gave diabetics either a standard medication (metformin) or berberine (500 milligrams three times a day). After 3 months, the herb lowered blood sugar as much as the drug.

HEART DISEASE. High cholesterol, high blood sugar, and high blood pressure are all major risk factors for heart disease. Because berberine diminishes them all, it also reduces risk of heart disease.

PSORIASIS. German researchers confirmed barberry’s traditional use in treating skin problems in a 4-week study involving 82 people with psoriasis, which produces red, raised, scaly skin eruptions. Each participant was given two ointments marked “left” and “right,” one with barberry extract, the other without. Participants applied each ointment to one side of their bodies. The barberry ointment produced significantly greater shrinkage of skin eruptions.

PINKEYE (CONJUNCTIVITIS). In Germany, doctors prescribe a berberine preparation, Ophthiole, to treat sensitive eyes, inflamed lids, and pinkeye. Unfortunately, the product is not available in the United States. To try it, apply a compress of barberry infusion.

Perhaps Harry Hoxsey was right. Animal studies suggest that barberry helps shrink some tumors. Pilot studies also hint that the herb has anti-inflammatory activity, suggesting possible value in treating arthritis.