CHAPTER FIVE

the universal and the particular

There’s a joke about the Finnish couple in which the wife complains to her husband that he never expresses his affection. He responds with consternation: “I told you I loved you when I married you. Why must I tell you again?”

We live in an age that does not approve of cultural stereotypes, and yet I think many of us would agree that each nation has its own signature behaviors. The English queue up in orderly fashion at the drop of a hat; Italians, less so. Berliners obeyed “Keep Off the Grass” signs under machine-gun fire during the revolution of 1919; Romans look upon a red traffic light as more a suggestion than a command.

Evolution wove our strongly social impulses into the essence of who we are as a species, but natural selection is not the whole story. There are also individual and cultural variations. For social insects, the behaviors that make the hive, the ant hill, or the termite mound an extended organism are genetically determined. For human beings, while behavior is genetically constrained, it is also personalized by all our own sometimes maddening quirks and complexities.

The tandem influence of inheritance and individuality is why each of us experiences loneliness in a way that is unique, idiosyncratic, and grounded in the particulars of our life history and our own immediate situation. At the same time, however, loneliness also subsumes structural elements that are universal. Lying somewhere between the individual and the universal, there is also a role for distinctive cultural influences.

Culture—whether determined by a family, a town, an ethnic community, or national identity—plays a role in shaping what we aspire to in our relationships, and thus what will ultimately satisfy us. In Finland, cultural norms dictate that a person won’t feel odd or left out if he is not married. In Italy it is quite the opposite. But in spite of the importance assigned to marriage within the culture, fewer Italians than people of other nationalities identified their spouse as the one from whom they would expect help in an emergency.1

Friendship is another domain influenced by national identity. Germans and Austrians report having the smallest number of friends, followed by the British and Italians, with Americans reporting the highest number.2 Then again, it may be that Americans simply define the concept of friend in a broader and more casual way than do people from other cultures.

Conflicts between cultural norms and our own desires can further complicate and sometimes camouflage our experience of loneliness. Web culture may suggest that being able to list a thousand “friends” on my personal page is what I should want; a different culture suggests that knowing everybody at the trade show and getting invited to the best hospitality suite with the open bar and the huge cocktail shrimp should be a major objective. Our media culture seems to have convinced millions that becoming “famous” via YouTube or reality TV, even if it involves personal humiliation, will make them happy. But then, all too often, people who have done everything right according to the cultural dictates they accept can still be left asking “Why am I so miserable?” They may be unable to articulate, or even to entertain, the thought that, despite their culturally endorsed achievements, they lack the meaningful connections that would assuage their sense of personal isolation.

A Man Apart

One gentleman from our study of older Chicago residents, Mr. Diamantides, seems like a poster child for the power of positive thinking as well as a certain kind of social savvy. When you ask how he is, his response is an emphatic “I’m wonderful. How are you?” Dapper and energetic, a sharp dresser, Mr. Diamantides has worked in retail all his life. “I connect well with people,” he says. “It’s easy for me—I’m Greek!” He even completed a year and a half of college studying psychology, “just so I could understand people.” When he talks about social connection, he peppers his description of his life with phrases like “I’m just lucky”; “I’m blessed”; “Attitude is everything.” He is also proud to say that he knows a great many movers and shakers. “I have a wealthy clientele…but my customers treat me well because I really like them. I make people feel important. I make them feel special.”

In childhood Mr. Diamantides suffered no particular traumas, though the stigma of being “from the wrong side of the tracks” and maybe “not quite legit” stayed with him. “We were a little shady,” he explains. “In those days, if my cousin showed up with some hot watches, you’d say ‘Let me take a look,’ no questions asked.” But his parents, as he put it, were “really good to me.”

Mr. Diamantides says that he has maintained his religious faith, but he does not attend church regularly. He was married once, briefly, but for more than twenty years he has lived alone. He has no children, but he has a large extended family—lots of cousins, nieces, and nephews: “In the family, even if you’re wrong, you’re right. It’s a tremendous support system.” All the same, he says he enjoys his solitude. “I’m in a people business, so when I come home, I’m thrilled just to be able to do what I want.”

When asked to describe his loneliest moment, he mentioned the time when he was in his forties and both parents died: “I felt like an orphan.” But when asked to describe his warmest moment of social connection, he was stumped: “I’ve had too many…it’s hard to choose one.” When pressed, he mentioned that once a longtime customer left him a thousand dollars in his will, and that a neighbor he hardly knew left him ten thousand, when all he had done was to take the neighbor to the doctor once or twice. Then Mr. Diamantides remembered the real emotional high. Some years back he and another man had gone in together to buy one “founder’s” share in a start-up—they each put up ten thousand dollars—but there was nothing in writing. Years went by. They lost touch with each other. And then Mr. Diamantides received a check in the mail for five thousand—a long-awaited return on the investment. “My cousin told me, you know, there’s nothing on paper…keep it! But no way. I got on the phone and I tracked this guy down. Took me weeks. I even had to call California. He nearly died when he heard it was me. And we split the money! I felt like a million. He was so surprised. I floated for days. It was the best feeling I ever had.”

In conversation, Mr. Diamantides is so convincing in his claim that everything is great in his life that it is easy to assume he is “low in loneliness.” You might peg him as an interesting anomaly, a man with no immediate family, no close friends, who doesn’t “get out much,” who nonetheless feels immensely satisfied with his social world. But when we looked below the surface we found quite a different story. Mr. Diamantides completed the UCLA Loneliness Scale for us. He also allowed us to test his sleep quality, blood pressure, morning levels of the stress hormone cortisol, and other factors. What the psychological test showed, and what the physiological data confirmed, was that Mr. Diamantides had one of the highest loneliness scores of all the people we had ever studied.

The clues to this apparent contradiction are scattered throughout his self-report. For instance, it is hard to discount all the people with whom Mr. Diamantides had fallen out. The cousin who said the wrong thing, the brother with whom he argued about money. “I can’t forgive and forget,” he told us. “I’m not hostile or bitter…you’re just never in my heart again the same way.” It turns out that Mr. Diamantides had been conned in certain financial dealings by his wife, and he decided that he would never allow himself to be so vulnerable again, so he essentially closed himself off to other people. Unfortunately, he has remained in that same emotional isolation for years.

For all the large number of individuals that Mr. Diamantides sees during the day, there is no one that he considers a friend. Not even within the closely knit extended family that was such a “great support system”—he rarely if ever speaks to or sees any of his relatives. And as for his greatest experiences of warmth and connection, they all involve money.

The point is that people can misuse their powers of cognition in their attempts to self-regulate the pain of feeling like an outsider. They can create a false persona—a practice commonly known as self-deception—that frames their life the way they want it to appear. By working very hard at it, sometimes they can convince themselves that “It’s so because I say it’s so.” But the physiological and psychological effects of loneliness take their toll nevertheless.

Aspects of the Self

The role of subjective meaning in our sense of social connection is not all that different from the role of individualized, personal meaning in other aspects of our lives. You could have a designer come in and fill your bedroom, office, or den with expensive mementos, trophies, plaques, and photos apparently inscribed just for you by Elvis Presley and Vladimir Putin. Your visitors might be very impressed. But if all that stuff came from a prop shop, most likely when you walk into that room it still would not feel entirely right. You might be able to muster up some momentary ego gratification, but there would be no enduring sense of warmth and satisfaction, because those mementos and trophies would have no real meaning. In the same way, you can have all the “right” friends in terms of social prestige, in-group cachet, or business connections, or a spouse who is rich, brilliant, and fabulous looking, but if there is no deep, emotional resonance—specifically for you—then none of these relationships will satisfy the hunger for connection or ease the pain of feeling isolated.

Of course, in our daily experience, we don’t think about cultural constraints on our subjective experience of isolation any more than we think about its formal structure. Whether loneliness has two dimensions or twelve is the kind of thing only psychological scientists worry about. Nevertheless, knowing the universal structure of the experience can be useful, especially if we are trying to do some renovations.

If I ask you to imagine a room, you are likely to come up with a certain memory, a certain color, a smell, a view out the window, or perhaps the furniture or the pictures on the wall. But it is also true that, when we are objective, quantitative, and attentive to what is common about any room, we recognize that any room we can imagine will have three fundamental dimensions: length, width, and height. You experience the room as one big rush of sensations—a Gestalt—but these three facets contribute to and constrain your experience of it. If you want to try to redesign this room to make it more pleasant or functional, you will have to take these three fundamental dimensions into account.

In the same way, if we want to make ourselves happier and healthier by enhancing our social satisfaction, it pays to understand the universals, one of which is “the self” itself.

The psychologists Wendi Gardner and Marilynn Brewer did a study to examine the ways in which people might describe themselves when asked the question “Who are you?”3 They determined that self-descriptions can be categorized into three basic clusters:

- A personal, or intimate, self. This is the “you” of your individual characteristics, without reference to anyone else. This dimension includes your height and weight, intelligence, athletic or musical ability, taste in music and literature, and other personal preferences, such as liking Tabasco over tapioca.

- A social or relational self. This is who you are in relation to the people closest to you—your spouse, kids, friends, and neighbors. When you go to the PTA meeting you are little Zach’s mom or dad. When you go to your spouse’s office party, you are “the spouse of…” This is the part of you that would not exist without the other people in your life.

- A collective self. This is the you that is the member of a certain ethnic group, has a certain national identity, belongs to certain professional or other associations, and roots for certain sports teams. Similar to the relational self, this part of the self would not exist without other people. What makes this self distinct is that these are broader social identities, linked to larger social groups, that may be less obviously a part of your day-to-day experience.

People see themselves in these three dimensions because these are the same three basic spheres within which humans have always operated. From our earliest evolutionary ancestry, human beings have been unique individuals with specific physical characteristics, personality traits, and likes and dislikes, but we’ve also always shared close bonds with mates and offspring, and we’ve always lived in larger social groupings, from extended families to tribes to nation states. The “self” behaves a little differently in each setting. When you define yourself as part of a group (the collective self), for instance, you may be more inclined to agree with other group members, even on beliefs that may seem irrational (“Of course the Cubs will win the World Series this year!”), than when you are thinking of yourself as a unique individual.

Brewer and Gardner demonstrated exactly this effect by priming college students to think of themselves in a collective context—namely as members of their particular college community—then measuring how long it took the students to agree or disagree with something another student from their college said. As expected, those students who had undergone this priming were faster to agree, and slower to disagree, with their group members than were those who had not been set up to think of themselves as part of a group.

When you think of your self at the level of your unique personal identity, it is only human to compare yourself with others and feel a twinge of hurt or jealousy if someone outperforms you at something important. When the person who bests you is a friend or family member, the defeat can be even more painful than when you lose to a stranger.4 However, when your focus is on your family or community identity, it is easier to celebrate the triumphs of someone close to you as if these victories were your own. When Serena Williams defines herself as Venus Williams’s sister, it makes it easier for Serena to enjoy a Venus championship. With the focus on family identity or family pride, each of these highly competitive tennis stars becomes part of the same unit, and as such, one sister’s successes can be success for the other as well.

Three Degrees of Connection

In our research group, we compiled a vast amount of survey data documenting the structure underlying the ways people think about their connections to others. We subjected the data to factor analysis, a statistical sorting technique designed to uncover simple patterns in the relationships among variables. If you used factor analysis to analyze the features of a thousand rooms, the statistics would cluster to show that the essential factors that make a room a room are length, width, and height. Every room has them; there is no room without them. Other qualities such as “tacky” or “stuffy” or “green” would appear as variables standing outside the essential dimensions, one-offs that don’t say anything universal about the nature of rooms.

By using this same quantitative sorting technique we found that the universal structure of loneliness aligned very nicely with the three dimensions of Brewer and Gardner’s three-part construct of the self. For the self, the essential dimensions are personal, relational, and collective, onto which we can map the three corresponding categories of social connection: intimate connectedness, relational connectedness, and collective connectedness.5 Humans have a need to be affirmed up close and personal, we have a need for a wider circle of friends and family, and we have a need to feel that we belong to certain collectives, whether it is the University of Michigan alumni association, the Welsh Fusiliers, the plumbers’ union, or the Low Riders Motorcycle Club.

Not surprisingly, the three dimensions of the universal structure of loneliness are highly correlated. If you are happy in one (marriage, say), you tend to be happy in the others. Until, perhaps, perturbations in your environment throw you for a loop. Your husband suddenly dies, or you move to a new and alien community. A bereaved wife may have great friends, and these friends may do everything they can for her, but most often their support does not completely remove the deep pain of the loss of a life partner. When events knock one of the three legs of the stool out from under you—intimate, relational, or collective—the safe and comforting feeling of stability falls away, and even someone who has always felt intensely connected can begin to feel lonely.

However, we have also found that there is no absolute, one-to-one correlation between any of these objective, environmental indicators of social isolation and subjective experience. Marital status is one of the best predictors of intimate connectedness—that is, married people tend to be less lonely than single people—but not everyone finds marriage to be self-affirming. The nun, the explorer, the artist, or the hard-driving executive who does not marry may find meaning elsewhere. And we all know that close family connections can be a mixed blessing. The same is true for people who have more friends than they can keep up with. Believe it or not, for some people, the phone constantly ringing with invitations to fabulous soirees can become a source of stress. And while some of us are joiners, others are very private and need very little in the way of connection through group membership. On each of the three levels, the issue is not the quantity but the quality of relationships, as determined by our own subjective needs and preferences.

A former professor who described herself as “not a joiner” told me that she never appreciated her need for collective connection until she retired. It was only when she went back to live on her family’s farm in the Midwest that she realized just how much being a part of her scholarly department and her prestigious university had meant to her. But once she had gone back home, she found new ways of filling the need:

I belong to a very different group of people out here, people whose roots go back to pioneer days and who are steeped in the history of the area. Out here I don’t have real friends yet (though the family connections are rewarding), but that wider kind of connection helps keep me from feeling too lonely, partly because it’s just plain comfortable to feel like an insider, someone who belongs.

Similarly, many of us tend to ignore the collective aspect of social connection much of the time, then find ourselves surprisingly caught up in a group identity when a national emergency occurs, or when there is some insult to the dignity of a class of persons with which we identify. The attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, aroused the collective identity of Americans, just as the caricatures of Mohammed published in Denmark aroused the collective identity of even many Westernized Muslims. One person may watch a parade for immigrant rights and feel great: Look how diverse we are, yet we are all one city! Another person may watch the same event and feel threatened: This is not my town anymore…who are these people? We make meaning of such events—beautiful diversity, cheap labor, the end of the world as we know it—depending on many other factors in our lives and attitudes. And just as each of us represents the idiosyncratic within the universal, nothing says that your or my “idiosyncratic” is always going to be the same throughout our lifetime.

Over the past four decades, research by the psychologist Walter Mischel has demonstrated that, contrary to the idea of genetic determinism, people do not behave according to rigidly fixed traits that manifest themselves consistently across all situations.6 It is not that there is no consistency, but that the consistency is situational and temporal. You may feel lonely every time you enter into a certain situation (the lunchroom in high school), even if, at the same period in your life, you feel socially satisfied very consistently in another context (band camp). Your susceptibility to loneliness may remain stable across time, but the situations that cause you to feel most acutely lonely in childhood or adolescence will most likely be different from the situations that induce acute loneliness when you are a young parent or an older adult.

Loneliness and Depression

An even greater challenge to sorting out the exact dimensions of loneliness is that it rarely travels alone. Much of the early research in psychology and psychiatry was conducted in clinical settings with individuals who were suffering from a number of maladies, often severe. The most common pairing was intense manifestations of both loneliness and depression.7 Perhaps not surprisingly, then, the two constructs—loneliness and depression—were often lumped together.8 “I feel lonely,” for example, is a question on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.9

Nonetheless, factor analysis tells us that loneliness and depression are, in fact, two distinct dimensions of experience.10 Diagnostically, too, we know that depression is different, in part because it does not trigger the same constellation of responses that loneliness does. Loneliness prompts a desire to affiliate, but it also triggers feelings of threat and dread. As the experience grows more intense, the feeling of threat prompts a tendency to be critical of others. Loneliness reflects how you feel about your relationships. Depression reflects how you feel, period.

Although both are aversive, uncomfortable states, loneliness and depression are in many ways opposites. Loneliness, like hunger, is a warning to do something to alter an uncomfortable and possibly dangerous condition. Depression makes us apathetic. Whereas loneliness urges us to move forward, depression holds us back. But where depression and loneliness converge is in a diminished sense of personal control, which leads to passive coping. This induced passivity is one of the reasons that, despite the pain and urgency that loneliness imposes, it does not always lead to effective action. Loss of executive control leads to lack of persistence, and frustration leads to what the psychologist Martin Seligman has termed “learned helplessness.”

Within the struggle to self-regulate, loneliness and depression are at their core a closely linked push and pull. The most primitive organisms operate entirely on the basis of paired opposites, essentially a gear for forward and another for reverse. This facilitates a simple, two-part decision—approach or withdraw—repeated endlessly as the organisms confront every stimulus. They approach to eat or to mate, and they withdraw to avoid negative sensations, which usually mean danger. Biological systems all the way up to and including human beings continue to operate on the basis of similar pairings.

Given the evidence that loneliness is an alarm signal, embedded in the genes, and that it serves a survival function, there may well be an equally adaptive social role for its opposite, depression. Imagine one of our long-ago ancestors, a young man in a hunter-gatherer community on the plains of Africa. Motivated by a feeling of social isolation, he makes an approach—he tries to court a woman, or he tries to join a hunting party or a political alliance—but, for whatever reason, he is rebuffed. Merely persisting and blundering ahead would be a waste of energy, most likely counterproductive, and maybe even dangerous. During this initial period of rejection, a mildly depressed mood (as well as the lack of persistence associated with loneliness) might be useful. By tempering the impulse to approach and affiliate, depressive feelings might encourage our awkward ancestor, his executive control now diminished by his sense of social exclusion, to back off long enough to analyze his situation: “Maybe I came on too strong?” “Maybe I should offer a gift to soften them up.”11 At the same time, the passivity of the depressed mood (and the passive coping that loneliness ultimately induces) would conserve his energy and resources.12 Within a social hierarchy, when we have attempted an advance and failed, it can be to our advantage not merely to step back and rethink but to signal submissiveness.13 In that delicate context, depressed affect could serve as the human equivalent of a dog rolling over on his back and showing his vulnerable belly. The real pain of depressive feelings might also be a means of social manipulation—a cue, similar to crying, that says “I need help” and solicits attention and care from those around us.14 All in all, this inducement to lie low and to signal to others that we are not a threat might serve to minimize risk in social interactions during a time when we perceive that our social value is low, especially in relation to the intensity of our social wants.15

This kind of “go forward/back up” system may have worked long ago without so many of the negative consequences that we see today. In a world less socially complicated, with perhaps less mental anguish than modern humans now generate, the playing out of the sequence “approach/blunder/withdraw” followed by “regroup/resume normal activity” most likely occurred within a fairly brief time and without the need for the same cognitive sophistication required in today’s complex social environment. Extrapolating from primate behavior, we can reasonably assume that social conflicts, like most threats during the early development of our species, led to fairly quick resolution—for good or ill. The limited cognitive powers of the earliest hunter-gatherers, and the harshness of their environment, would not have allowed them the luxury of long bouts of passive melancholy, ambivalence, and soul searching. Over many millennia, however, with increasing intellectual and psychosocial complexity, a simple sequence of “go/stop/go again” has evolved into a vicious cycle of ambivalence, isolation, and paralysis by analysis—the standoff in which loneliness and depressive feelings lock into a negative feedback loop, each intensifying the effects and the persistence of the other.

This is the situation in which we left our friend from Chapter One, Katie Bishop, sitting in front of the television, eating ice cream directly from the carton. If she were a character in a date movie, she might run down to Starbucks the next morning and spill her latte on the perfect someone, finding romance, companionship, and a wide social network of zany new friends. But then again, in real life, she might feel so low that she simply pulls the pillow over her head and hides under the covers until noon.

When we begin to look for the specific physiological pathways that lead from social isolation to increased illness and shortened life expectancy, we have to consider the possibility that loneliness and depression are both manifestations of some other overarching problem. We also have to take into account a long list of other variables that might show up in the same kinds of circumstances, any one of which might account for the effects we see. How can we determine whether it is actually loneliness, or one of these associated factors, that is driving the plot as the story unfolds?

There are three standard ways to identify associations and investigate causal relationships. The first is a cross-sectional study: You cast a wide net to gather many different types of people, and then you measure a variety of variables at a single point in time. The second is a longitudinal study, which means identifying a certain population and then following its members over a long period, making repeated measurements of certain variables as their lives play out from day to day. The third is random assignment and experimental manipulation.

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies can provide a wealth of useful data. The longitudinal approach also controls for a number of additional factors that cannot be dealt with satisfactorily in a cross-sectional study. For instance, whether an adult had a secure or insecure attachment with his mother in infancy may not be something that can be measured reliably now. However, each participant in a longitudinal study serves as her own control—the study follows the same person, after all, and her past remains the same. In a longitudinal study, then, in which the focus is on changes in loneliness and related variables over time, we separate and evaluate the effects of these changes from those that do not change across time, such as infant attachment style. Still, neither of these approaches can tell us definitely that we have found direct cause and effect. Even if we can demonstrate a strong association between loneliness and certain other factors in a longitudinal design, and even if we have ruled out all known alternative accounts, it does not mean that we have shown convincingly enough to overcome the skepticism of good science that one factor causes another. This is when experimental manipulation becomes particularly useful. To sort out the constellation of variables surrounding loneliness, and to determine what is the most likely cause of what, my colleagues and I used all three approaches.

Manipulating the Mind

For our cross-sectional analysis, we went back to the large population of Ohio State students that had supplied volunteers for our dichotic listening test. We refined our sample down to 135 participants, 44 of them high in loneliness, 46 average, and 45 low in loneliness, with each subset equally divided between men and women.16 During one day and night at the General Clinical Research Center of the OSU Hospital, we subjected these students to such a wide array of psychological tests that we might have been packing them off for a mission to Mars. This allowed us to develop a precise statistical profile of other personality factors as they appear in association with varying degrees of loneliness. In other words, this study population gave us a clear picture of the full psychological drama accompanying loneliness as it occurs in the day-to-day lives of a great many people observed during a specific period of time. The cluster of characteristics we found were the ones we had anticipated: depressed affect, shyness, low self-esteem, anxiety, hostility, pessimism, low agreeableness, neuroticism, introversion, and fear of negative evaluation.17

Given the complexity of that implicit drama, the next challenge was to see if we could demonstrate through a controlled experiment that loneliness played a leading rather than just a supporting role. A controlled experiment means studying people in a situation in which you can hold certain variables constant while you manipulate some other variable. Such an experiment also requires that the participants be randomly assigned to different levels of the manipulation taking place.

To manipulate levels of perceived loneliness, we enlisted David Spiegel, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, to hypnotize our experimental subjects. Using precisely worded scripts, we guided our hypnotized student volunteers to re-experience moments in their lives that summoned up either profound feelings of loneliness or profound feelings of social connectedness. With some individuals we induced loneliness in their first hypnotic state and social connectedness in their second; with the others the order was reversed. Before and after each hypnosis we administered the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale to ensure that the hypnosis had induced the desired emotional state.18

Earlier, Spiegel had done a classic experiment with Harvard’s Steven Kosslyn to demonstrate that hypnotic suggestion was not merely an extreme case of suggestion, coercion, and compliance. This earlier study focused on color perception: Hypnotized participants would be shown an image while they were told either that it was in color or that it was in black-and-white; the hypnotic suggestion sometimes matched the actual image and sometimes did not. PET scans administered during the hypnosis showed that the subjects’ brains were physically registering color or black-and-white according to the hypnotic suggestion, even when it was contrary to fact. In terms of the brain’s response, then, the induced experience was as real as real can get.19

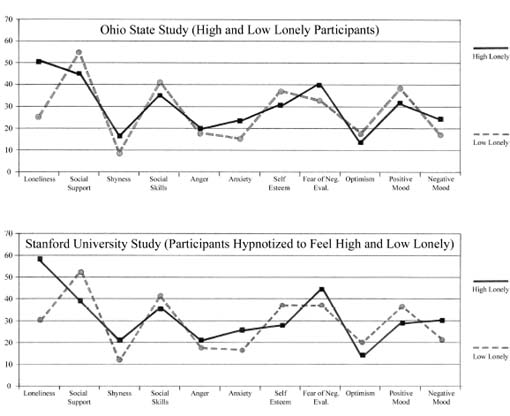

With each of the Stanford students, after the hypnotic induction had produced feelings of loneliness or social connectedness, we administered the same psychological tests that we had administered earlier to our OSU students. As displayed in Figure 5, the results were a match. Examining the graphs side by side was like watching CSI when the forensic experts match up fingerprints.

In the top panel of the figure, the two jagged lines compare the test results for the OSU students in the top twenty percent in terms of loneliness (the solid line) and the OSU students in the bottom twenty percent in terms of loneliness (the dashed line). The students high in loneliness, compared to those low in loneliness, reported lower levels of social support, higher levels of shyness, poorer social skills, higher anger, higher anxiety, lower self-esteem, higher fear of negative evaluation, lower optimism, lower positive mood, and higher negative mood.

In the bottom panel, the two jagged lines compare the test results for individual Stanford students when they had been hypnotically induced to feel high in loneliness, and when these same individual students were induced to feel low in loneliness. Their test results for the eleven other characteristics being measured—mood, optimism, social skills, and so on—followed very much the same pattern.

Merely by manipulating feelings of loneliness and social connectedness, we had managed to produce corresponding appearances by, with corresponding levels of intensity from, all the other players in the drama. Loneliness, then, definitely had a starring role.

Moreover, we had demonstrated yet again that lonely individuals are not a breed apart. Any of us can succumb to loneliness, and along with it, all the other characteristics that travel as its entourage.

The surveys of the Ohio State students as well as the manipulations by way of hypnosis showed the effect of loneliness on thoughts, moods, self-regulation, even personal characteristics such as shyness and self-esteem—in the moment. But what about chronic loneliness? Leaving participants in an unpleasant and unhealthful state over time would be exceedingly unethical, so we could not induce persistent feelings of social isolation through manipulation. Longitudinal research is an ethical alternative, which is why we initiated our longitudinal study of middle-aged and older adults from the greater Chicago area.

FIGURE 5. Top panel: comparison of characteristics of very lonely individuals with those of not at all lonely individuals. Bottom panel: comparison of characteristics of individuals induced to feel lonely with those of the same individuals induced to feel nonlonely.

Restoring the Whole

To accomplish a precise measurement of the effects associated with chronic loneliness and changes in loneliness over time, we identified a subset of individuals from our Chicago study population who were truly a representative sample, the kind that news organizations use in order to predict elections on the basis of survey data. We used a quota sampling strategy at both the household and individual levels to achieve an approximately equal distribution of participants of African-American, Latino, and other European ancestry, as well as an equal number of men and women in each group, all between the ages of fifty and sixty-seven years.

We asked each participant to complete the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale as well as a measure of depression commonly used in epidemiology research. Our Ohio State University volunteers had completed similar scales, and when we conducted a factor analysis of all the items, those from the UCLA scale fell into clusters aligned with the three loneliness factors (intimate, relational, and collective connectedness). The items from the depression scale fell into their own separate structure. When we repeated these analyses using the responses from our sample of middle-aged and older adults in Chicago, the items from the loneliness and depression scales clustered in such a way as to confirm once again that loneliness and depressed affect, while correlated, are distinct phenomena.20 Analysis of the longitudinal data from our middle-aged and older adults showed that a person’s degree of loneliness in the first year of the study predicted changes in that person’s depressive symptoms during the next two years.21 The lonelier that people were at the beginning, the more depressive affect they experienced in the following years, even after we statistically controlled for their depressive feelings in the first year. We also found that a person’s level of depressive symptoms in the first year of the study predicted changes in that person’s loneliness during the next two years. Those who felt depressed withdrew from others and became lonelier over time. So here too was the stop-and-go mechanism of loneliness and depressive symptoms we had postulated, working in opposition to create a pernicious cycle of learned helplessness and passive coping.

Most important, these studies probing cause and effect suggested a way to get beyond the Catch-22 embedded in our experience of isolation. If the self-defeating symptoms of loneliness can be externally induced by hypnotic manipulation of memories and feelings, and if they can change over time as a result of real—but also perceived—changes in one’s social environment, then with increased awareness and effort, there should be a way for lonely people to learn to manipulate those same perceptions, cognitions, and emotions themselves.

But before we examine that possibility, there is one more mystery to pin down. All the evidence points to loneliness as a ringleader that brought at least eleven other, associated emotional states to the scene of the crime, that crime being a sometimes life-threatening assault on physical health as well as emotional well-being. So loneliness was on the scene and exerting a lot of influence—but how can we be sure that loneliness itself was the actual “perp”? How can we be sure that the serious declines in health and well-being we observed over time were triggered by something so intangible as a subjective sense of social isolation? If loneliness has the power to actually cause illness, what is its modus operandi?