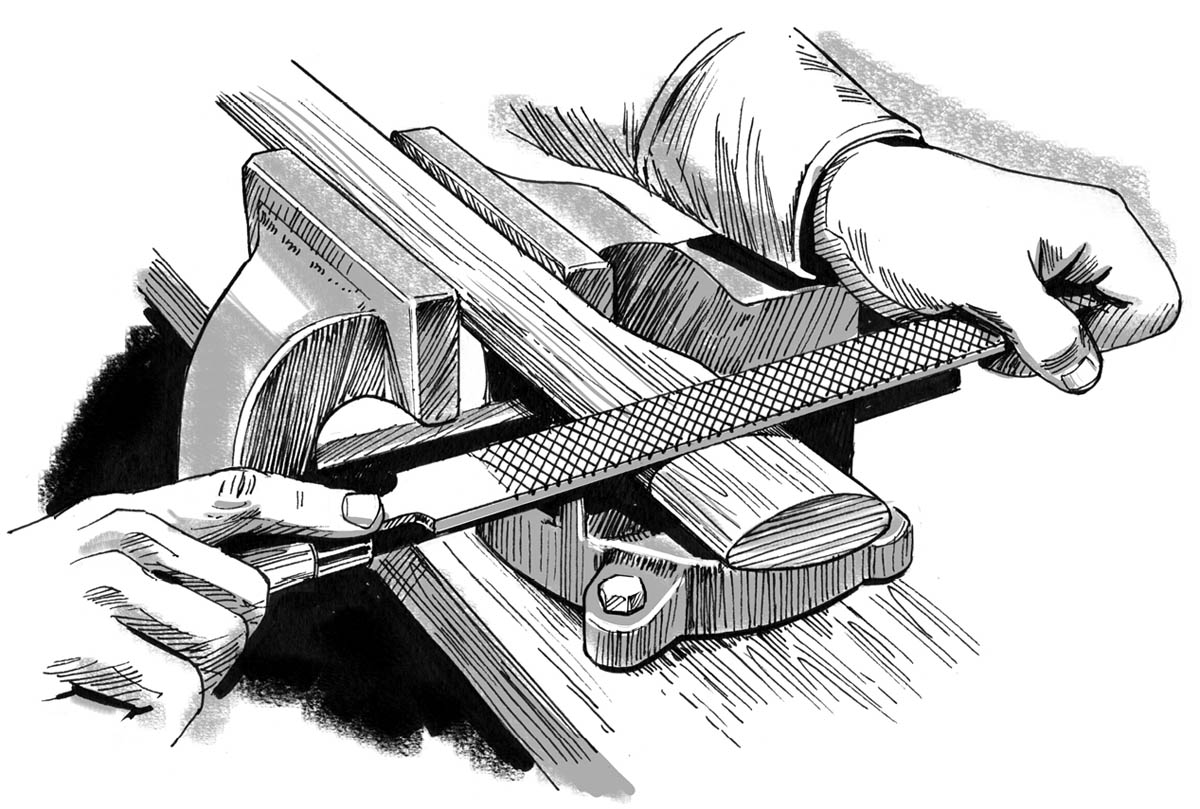

Essentials for the Homestead Woodlot

Now that you’ve inventoried your homestead woodlot and begun to sharpen your woodland eye, it’s time to start learning the tools and techniques that will make your land more productive, sustainable, and enjoyable. Because homestead woodlots vary in size from a fraction of an acre to several dozen acres, we’ll examine tools and techniques for a variety of projects and properties at different scales. We’ll begin by turning our eye to the past, to learn about woodland hand tools and techniques that have been largely forgotten but are useful to homesteaders because they are simple, are readily available, and have stood the test of time.

No other tool has shaped the American landscape as drastically or indelibly as the axe. What began as a stone lashed with sinew to a wooden handle during the Neolithic period eventually evolved, over a 10,000-year period, into the modern steel axe. The first metal axes were cast of copper, which could be filed to a sharper edge than most stones but unfortunately was too soft for all but the most delicate of tasks. Around 3000 BCE, copper was combined with tin to form bronze, which was both a durable and workable material. The early bronze axes were both utilitarian and war implements that remained largely unchanged for nearly a thousand years. Around 1300 BCE, iron ore mining led to the proliferation of inexpensive iron axes, which the Romans eventually improved on by adding carbon to create steel.

As steel became the chosen material for virtually any durable good, European axe makers began saving steel for just the bit, or cutting edge, of the axe and used cheaper iron for the cheeks and poll (the back) of the axe. Prior to the mid-19th century, European blacksmiths produced two types of axes: broadaxes for making square timbers (also called “cants”) and lighter-weight general-purpose axes that were used for a variety of farm and woodlot chores.

When European settlers arrived in the virgin forests of eastern North America, they quickly discovered that the smaller, lighter-weight European axes that were used on small-diameter coppiced trees weren’t up to the task of felling large timber. These early settlers made two modifications that resulted in the modern felling axe.

A heavier poll. First, the settlers added substantial weight to the poll of the axe. This additional weight meant that the woodsman didn’t have to swing as hard and could instead let the weight of the axe do the work. More weight behind the handle also meant better balance, which made for truer swings.

A shorter bit. The settlers also shortened the bit, or cutting edge. Early European axes had a wide cutting edge, which made for an effective battle weapon but didn’t allow for concentrated penetration when it came to chopping wood.

Felling axes also developed regional identities as blacksmiths and lumberjacks named their axes after the places they were made; Connecticut, Michigan, Maine, and Pennsylvania were all popular patterns. As they replaced the blacksmith, modern forges began to produce hundreds of patterns for different uses and enough pattern choices to satisfy lumberjacks from coast to coast. In fact, by the early 19th century, more than 300 patterns existed for felling axes alone.

A variation of the single-bit felling axe was the double-bit axe, sometimes referred to as a “reversible.” These axes first appeared in Pennsylvania around 1850 and were commonly used in the Northeast by 1860. The debate continues as to whether a single-bit or double-bit axe is superior. Single-bit aficionados point to the fact that this axe benefits from a heavy poll, which allows the axe to penetrate deep into the wood. Those who prefer the double-bit axe point to its utilitarian benefit: one bit can be kept stoutly sharpened for cutting knots and dirty wood, while the other can be finely honed for cutting clear and clean wood. In the end, it’s likely a matter of personal preference, with the single-bit axe being a more efficient tool and the double-bit axe having greater versatility.

Axes come in a variety of shapes and sizes to suit a range of tasks and users. The smallest member of the axe family is the trusty hatchet. Its small size makes it easy to stow and carry, while the short handle affords control. However, since the size of the axe is roughly proportional to the size of the job, you’ll find the hatchet most appropriate for light chores like splitting kindling. A step up from the hatchet is a “boy’s axe,” which typically has a mid-length handle (about 28 inches) and a 2- to 21⁄2-pound head, making it ideal for a variety of woodlot chores. The full-size felling axe typically has a long handle (31 to 36 inches) and a heavy head (31⁄2 to 6 pounds) but is capable of handling larger jobs on the woodland homestead.

Seeking out old axes and restoring them is well worth your time. It is estimated that from 1850 to 1950 more than 10 million felling axes were produced by more than 100 different axe manufacturers. During this period, manufacturers had easy access to quality steel, and competition among forges meant that the quality of axes produced remains unprecedented to this day. Relatively few high-quality felling axes are still made, but barns and basements continue to be great places to find a quality vintage axe just begging for a second chance.

Finding a vintage axe to restore is easy if you know what to look for. First, don’t get hung up on the state of the handle. In most cases, the old handle will be brittle, cracked, or rotted near the eye. Instead, focus your search on finding a salvageable axe head. Consider how you’ll use this axe: Will it be for felling large trees? Maintaining trails? Or splitting firewood rather than chopping wood (cutting diagonally across the grain)? If your goal is to have an axe for splitting, even the most chipped and abused axe can be resurrected as a trusty splitter. If, however, you want a chopping axe with a keen edge, find an axe with a gentler past and perform the all-important five-point axe inspection.

Size. A standard felling axe weighs 31⁄2 pounds. A longer, thinner-bitted axe will slice through wood more easily, while a short, chunky axe is better suited for splitting, where you’re not actually cutting the wood but simply “popping” the wood apart along the grain.

Markings. Virtually all quality vintage axe manufacturers included their name or logo on the cheek of the axe. Some of the more notable axe makers were Plumb, Kelly-True Temper, Mann, Collins, and Council. All of these companies used quality steel in their axes. In some cases the markings can be difficult to locate, though a bit of steel wool will usually reveal a clear enough stamp to identify the maker. As you search barn sales and basements for vintage axes, keep an eye out for the rare and highly coveted Kelly-True Temper Black Raven. This axe was sought not only for its superior steel quality but also for the intricate black raven stamp on the side. In good condition, this axe can fetch several hundred dollars.

Bit condition. The bit of the axe is where the work is done, so it is important that the bit is relatively free of chips. A chipped bit will create resistance, known as drag, when you try to chop. Therefore, it becomes necessary to grind the bit until the chip is gone. The problem is that grinding the axe creates a shorter, stouter bit that doesn’t cut very well. You’ll also want to inspect the toe of the axe; it should carry the same arc as the rest of the bit. If it’s rounded off, that’s a telltale sign that the axe has been used for cutting roots or maybe even sharpening rocks. This is problematic because an overly rounded bit coming in contact with a round log increases the odds of the axe glancing, or deflecting in an unsafe direction as the two rounded surfaces make contact.

Eye condition. The eye is the only point of contact between the handle and the head of the axe. An eye that is even slightly out of plumb means that the axe will never swing true, creating just enough deviation in the swing that the axe will likely glance, and potentially score a date with your shin. There are two potential causes for an untrue eye. The first is a defect in the manufacturing process. When an axe is made, the eye is generally cut using a punch. If the punch is not perfectly aligned, an off-center eye will result. The second is a result of misusing the axe as a sledgehammer. Because the steel on the sides of the eye needs to be thin to achieve a narrow profile, it is particularly susceptible to bending and warping. This deformation often prevents the handle from fitting properly. It’s best to avoid any axe that shows an off-center or deformed eye.

Poll condition. The poll is located directly behind the eye of the axe and is commonly “mushroomed” as a result of the axe being used as a sledgehammer. In cases of minimal damage, the burred edges can be lightly ground. In other cases, hairline cracks may extend from the eye into the poll or the eye may be deformed, as described in the preceding paragraph. As a general rule, axes with severe mushrooming and cracks should be avoided.

An axe drift is used to remove the handle from the eye. If you don’t have a metal drift, make one by cutting a short section out of the broken handle.

If your old haft, or handle, shows any signs of deterioration (cracks, a loose head, or a rotted eye), you should begin your restoration by fitting a new handle that you can safely clamp in a vise when you need to sharpen the head of the axe later on. “Hanging an axe,” as woodsmen often call the process of fitting a handle, is as much of a skill as swinging or sharpening an axe; it requires both patience and practice.

Before you hang a new haft, you’ll likely have to remove the old one. A common temptation is to toss the head in the fire to burn out the eye. Do not do this. Doing so will change the temper of your axe, in most cases making it more brittle and prone to cracking. Instead, saw off the old haft and remove it from the top down. This can be accomplished one of two ways:

Once you’ve removed the old haft, it’s time to select a replacement. Three considerations should guide your selection of a new handle: straightness, grain orientation, and growth-ring width.

Straightness. Handles are generally sawn out of hickory or ash logs and then turned on a lathe. Depending on where the tree grew and how the log was sawn, the handle may twist or bow. With the exception of broadaxes, which have intentionally curved handles, you’ll want to examine your replacement handle for trueness. By holding the eye of the handle just below your eye, visualize an imaginary line from end to end. Does the handle hold true to that line, or does it bow either left or right, or twist? Only accept an axe handle that is straight and true. Using a twisted or curved handle can cause the axe to glance, causing injury.

Grain orientation. The end of the axe handle is known as the doe’s foot and will tell you which way the grain runs. Ideally, the grain should run parallel to the bit of the axe. Handles in which the grain runs perpendicular to the bit are inherently weak and snap under percussion.

Growth-ring width and quality. Tight, narrow rings indicate slower growing wood, which makes for a stronger handle. You should also pay attention to the color of the wood: Is one side of the handle dark wood and the other side light wood? The dark wood represents heartwood, which is dense but brittle. The lighter wood is the more recently grown sapwood, which is strong and flexible. Try to select an axe handle that is made entirely of sapwood. A handle that is made of both sapwood and heartwood is more likely to fracture.

Taking the time to select a haft with proper grain orientation will reward you with years of service. The grain should always run parallel to the bit of the axe.

The expression “to get the hang of it” originated with lumberjacks who were referring to a proper union between haft and head. If a haft fit poorly, the jack would often proclaim, “I just can’t get the hang of it,” meaning “I just can’t get it right.”

By beginning your axe restoration with a new handle, you now have a dependable point from which you clamp, hold, and work on your axe. To preserve your new handle, clamp it in a bench vise using a shop rag. The middle third of the handle is the straightest part, giving you the best clamping location.

You’ll want to begin by removing the surface rust, which can be done by hand with a sanding block but is much more effective using either a belt sander or an orbital sander. If your axe looks more like a relic from a shipwreck than a trusty tool, consider starting with 80-grit sandpaper. Start lightly, keeping an eye out for manufacturing marks. If you find any, lightly sand these areas by hand using steel wool.

After removing the surface rust, you’ll have a better idea what you’re dealing with. Deeply pitted axes may prove unserviceable, though in most cases these axes may be resurrected by using a more aggressive grit of sandpaper and additional elbow grease. Cleaning up the cheeks of the axe is important because this is the part of the axe that is in greatest contact with the kerf (or cut surface) of the log. Any pitting or remaining rust will serve as an abrasive, making the axe stick.

Once you’ve removed the majority of the rust with 80-grit sandpaper, move to 120-grit sandpaper. As you continue to clean the axe, maintain light pressure and make sure you don’t allow the sander to catch the bit. Also, if you’re using an orbital sander, make sure it’s continually moving; you don’t want to create “hills” or “valleys” in the surface of the axe. With a belt sander, this is easier to avoid since you have a large, flat plane that you’re essentially laying on the cheek of the axe.

Once you’ve cleaned up the surface of the axe, you can then restore the back, or poll, to its original form. If the axe was ever used as a hammer, the poll will likely be in need of some light grinding to remove burrs and mushroomed edges. With the axe laid flat in the vise, make long, smooth strokes to clean up the mushroomed poll. You may also find that the top edge of the axe needs light grinding as well; this is often the result of using a hammer, instead of a wood or rubber mallet, to drive out an old handle. Take your time and remove as little metal as possible.

Ask two woodsmen how to sharpen an axe, and you’re liable to get three answers. Some swear by a filed edge, while others believe in only using a whetstone. Still others use bench grinders or belt sanders. My experience is that the condition of the bit and the quality of the steel are the two factors that ultimately determine which tool I use for sharpening.

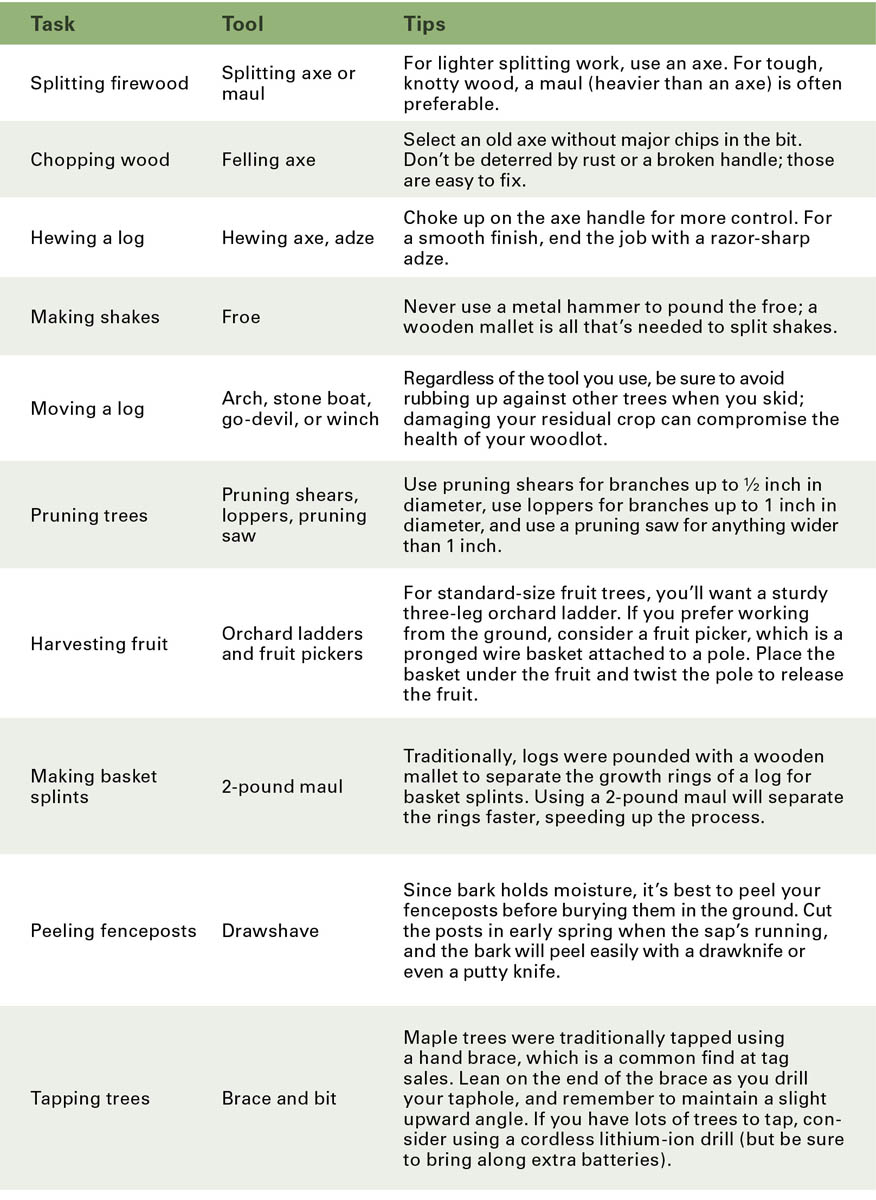

If the bit of your axe is in poor condition, with chips, gouges, and other imperfections, I would strongly recommend using the belt grinder method outlined in this section. Do not use an angle grinder for sharpening the edge of your axe. The wheel of an angle grinder is too small to create a smooth, even bit. Instead, you’ll end up with a bit that is thick in some places and thin in others. What’s more, the heat created by grinders can result in hot spots that ruin the temper of the axe. A more effective tool for sharpening dull and damaged axes is a narrow-gauge (11⁄8" × 21") belt sander.

To begin, use 180-grit sandpaper belts. Before you even plug the sander in, practice drawing the sander back and forth, following the radius of the axe. The sander should point toward the poll of the axe as you do this, and be angled upward at approximately 20 to 25 degrees.

“Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.”

— Abraham Lincoln

Once you’re comfortable with the motion, you can begin grinding by using light strokes. Be sure to count the number of strokes so that you maintain an even bit angle on both sides. Check the bit regularly to make sure it’s not too hot. If it’s too hot to touch, you’re either going too fast or applying too much pressure.

As you flip the axe from side to side, use a small piece of hardwood to drive off the metal burr that forms as the bit of the axe is thinned to an apex. If you don’t drive the burr off, you’ll end up with a brittle wire edge that will break off. Once you’ve removed the major imperfections in the axe, switch to 220-grit sandpaper belts. When the bit is free of nicks and imperfections, you’re ready to hone the axe using a whetstone.

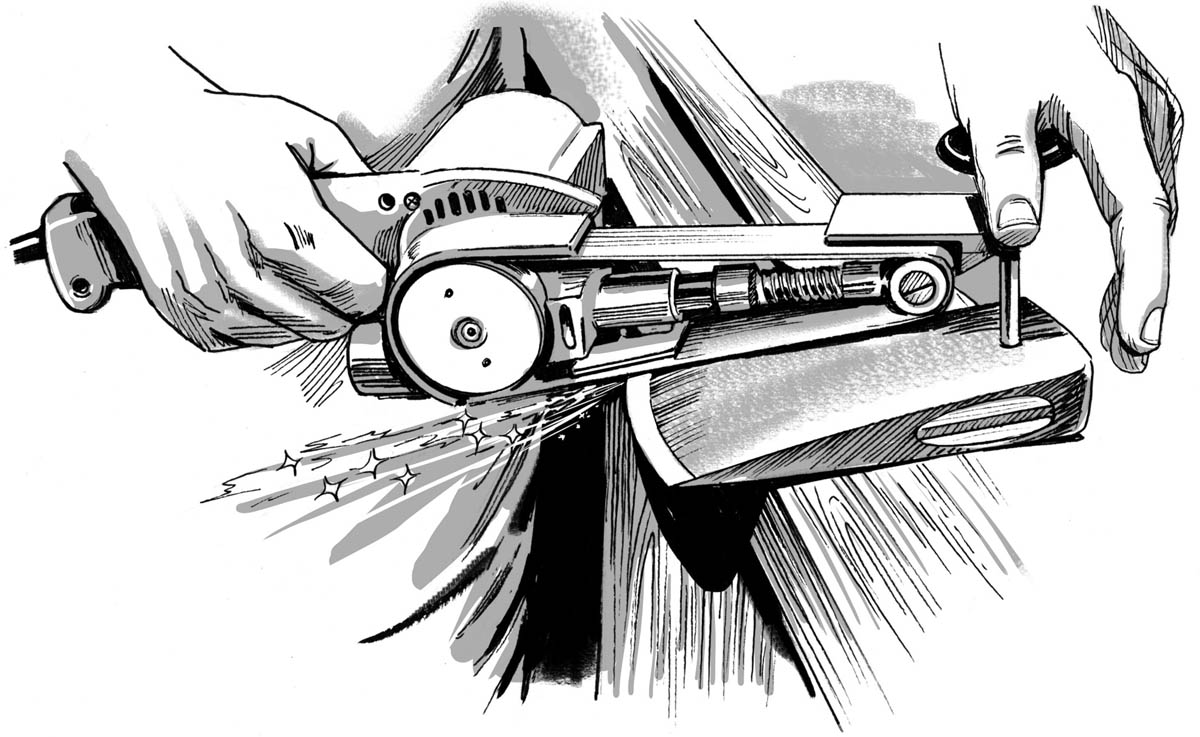

An alternative to the belt sander method is the single-cut bastard file, which I prefer for axes with soft steel or only minor dings. The file can be used freehand or with a jig. The jig maintains a constant 20-degree angle at all times. (See here.)

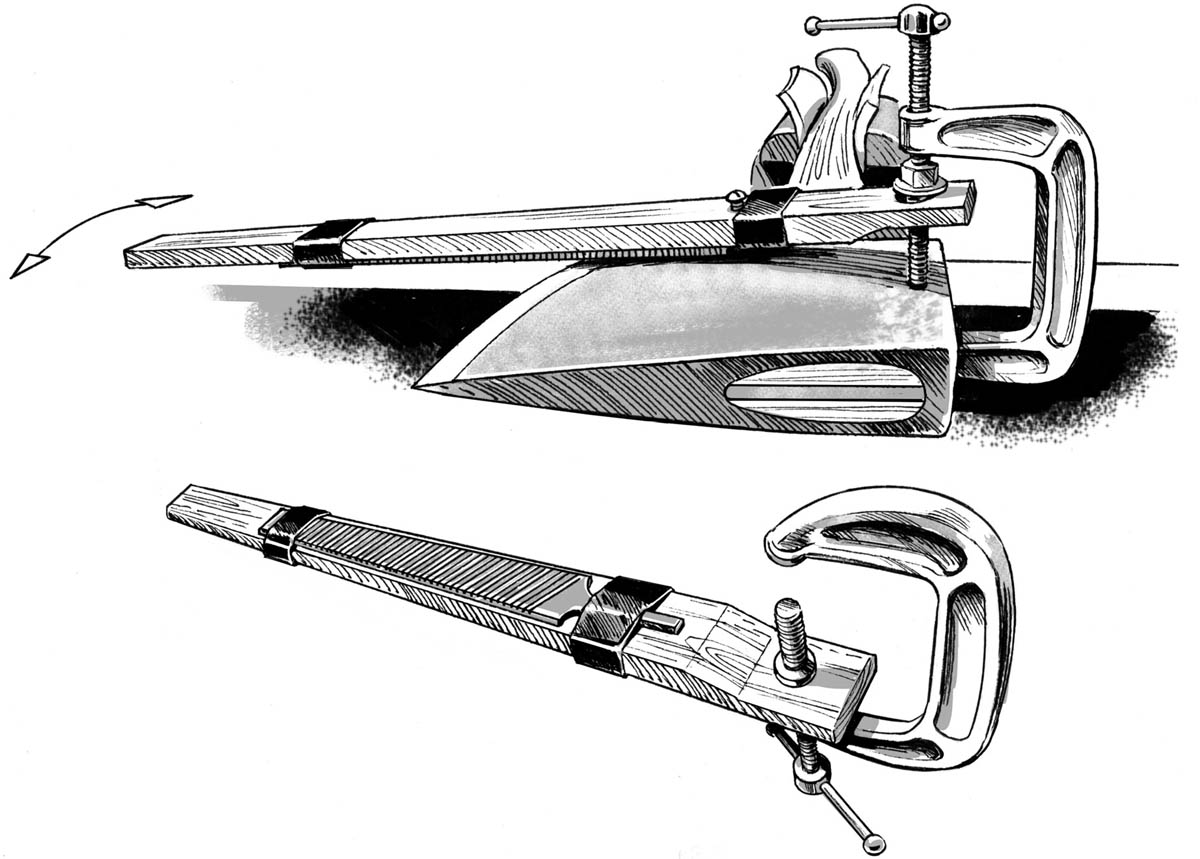

The last step in sharpening the axe is to use a whetstone on the cutting edge. This final cutting edge is about 10 degrees stouter than the grinding or filing angle. You can use either a hard Arkansas stone or a long-lasting but expensive diamond stone. As with grinding and filing, it is important to maintain a constant angle; for that reason I prefer long, even strokes over small circular strokes. Be sure to do an equal number of strokes on each side and, as in the grinding process, drive off the burr with a piece of clean hardwood.

A sharp axe will be able to shave the hair on your arm or cleanly slice a sheet of paper. Sharpening an axe with finesse takes time and patience, but the investment pays dividends in the woodlot.

Narrow belt grinder. If done properly, using a belt grinder is the fastest and most accurate way to sharpen an axe. Be sure to mark the center of the arc on the poll of the axe and use a punch to create a small divot. This will create a reference point for sharpening in the future. Remember to count the number of strokes on each side in order to maintain a balanced edge.

Bastard file jig. This simple jig is made from a C-clamp, part of an old yardstick, and a bastard file. The angle can be measured using a compass, and can be adjusted by adding or subtracting metal washers on the C-clamp. A 20-degree angle is ideal for chopping most wood.

Whetstone. Honing the axe is the final step in sharpening. Use long, even strokes from heel to toe. For a more durable final edge, you can increase the honing angle up to 30 degrees.

To early homesteaders, the axe was not just a symbol of freedom; it was a 5-pound ticket to self-sufficiency. Proficiency with an axe meant being able to fell timber to build a home, chop wood for the hearth, and clear land for pastures. And while your axe ambitions may not be as driven by necessity as they were for early homesteaders, there is value in knowing how to swing this basic yet endlessly useful tool. We’ll cover the two most common chopping methods used for felling and bucking on your woodlot.

Referred to today as the standing block chop or vertical chop, this technique predates the advent of the felling crosscut saw, which was developed in the 1880s. However implicit, it is worth noting that felling a tree with an axe is inherently dangerous. Later in this chapter, we’ll review felling with a chainsaw, which offers greater efficiency and control. Despite the advantages of the chainsaw, the axe has earned its role in the woodlot as an invaluable tool.

To fell a tree with an axe requires lessons in physics and geometry. First, the physics: Your axe handle is a giant lever connected to a blade. The longer the swing of the stroke, the greater the power delivered to the trunk of the tree. However, power without proper presentation of the axe bit will result in a dull and unimpressive thud. Therefore, axemanship is as much about presenting the axe at the proper angle as it is about developing power. When you begin chopping, focus on accuracy and precision; power can be developed in time.

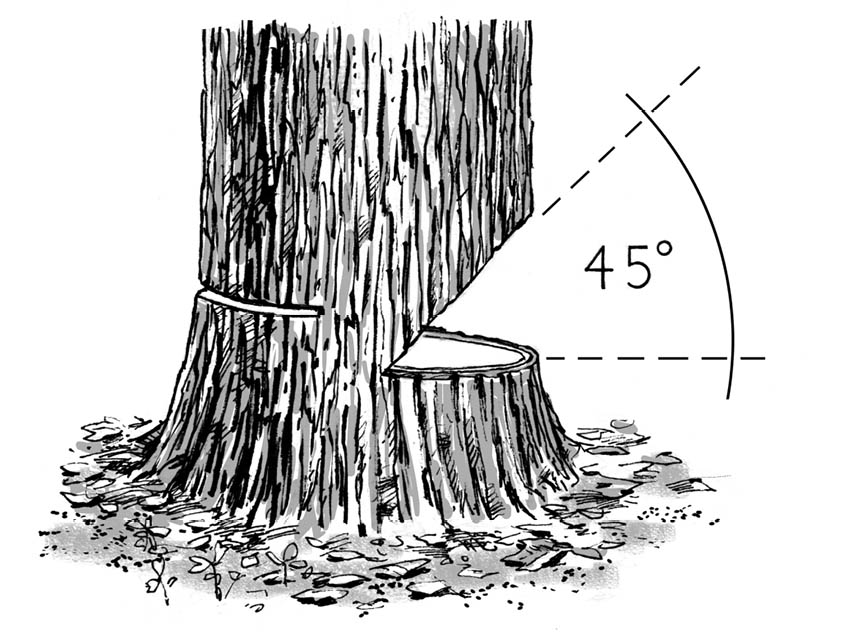

The shortest distance through a log is perpendicular to the grain. Unfortunately, unlike a saw, an axe doesn’t tear grain; instead, it slices the grain at an angle. So, while a shallow angle would result in cutting the shortest distance, it wouldn’t be efficient since each hit would achieve only minimal penetration. In contrast, if you chop at too wide an angle, you have to cut a greater distance, reducing your overall efficiency. For most species of wood, you should create an upward 45-degree angle and a downward 45-degree angle, resulting in a 90-degree face that is approximately equal to the diameter of the tree in width.

When felling a tree, make sure you’re wearing a hard hat, as well as eye, foot, and shin protection. (See here for more information.)

Begin all felling by identifying hazards, tree lean, and your escape route. (The section on chainsaw felling beginning here gives details on determining each of these.)

Mark out your opening face on the front of the tree. Your bottom hit will be at knuckle height when you stand beside the tree, arms hanging at your side; the location of the top hit should be equal to the diameter of the tree measured from the bottom hit.

If you are right-handed, take a wide stance with your left foot in front, about 18 inches from the tree. Then bring the axe back in line with your right foot. (Reverse this for lefties.) For your bottom hit, allow your top hand to slide down the axe handle as you strike the tree. The striking angle should be 45 degrees.

For your top hit, bring the axe up and away from your body at a 45-degree angle. Allow your top hand to slide down the handle as you strike your top mark.

Work in a clockwise direction, spanning the axe so that you cut both your near and far wood on larger trees. The V angle formed by the cut should close just shy of the midpoint of the tree.

Move to the backside of the tree, working the same diameter scarf and same pattern approximately 1 inch above the front cut. Be careful not to cut through the hinge, as this allows the tree to fall in a controlled manner.

Once your tree is on the ground, you’ll have a mess of limbs to contend with. The temptation is to cut into the V of the branches, swinging the axe toward the base of the tree. This method causes the axe to dive into the knot rather than cleanly slicing the branch even with the trunk of the tree. Instead, swing from the base toward the top of the tree. Work side to side, limbing the branches while you safely stand on the opposite side of the tree. Make sure that the path of the axe is clear of any branches or other obstructions that could deflect the axe. For larger limbs use a 45-degree V notch to chop through the branch.

When limbing with an axe, stand on the opposite side of the log to protect your shins from a glancing blow of the axe.

To "buck" a log means to cut it into shorter, more manageable lengths. Historically, lumberjacks would stand atop the tree and swing the axe between their feet to sever the log. As you can imagine, this underhand chop method led to a plethora of lumberjacks earning the nickname “Stumpy.” For most woodlot bucking needs, it’s safer and more efficient to have both feet firmly planted on the ground. (See Bucking Like a Beaver.)

You can use a felling axe for bucking; however, it is important to exercise caution since you’ll be swinging the axe closer to the ground. Striking rocks on the ground can not only damage your axe but also send chips toward your face. Safety glasses are recommended.

Unlike the felling axe, the broadaxe, or hewing axe, remained relatively unchanged after its arrival in the New World. The purpose of the broadaxe is to square timbers by slabbing off the rounded edges of the log, a process known as hewing. In reality, the broadaxe is a large chisel. Most broadaxes carry a single-bevel bit that’s filed to a razor edge. In order to give the hewer control, broadaxes typically have a short handle, no longer than 24 inches.

Once you’ve selected a straight and relatively knot-free log, you’ll want to roll it on to a set of bunks or shorter logs placed perpendicular to the hewing log. These bunks act like sawhorses, giving you a slightly elevated and stable surface to work from. The bunk logs can either be notched with an axe to cradle the log, or held down with a pair of log dogs (giant staples) that are pounded into the hewing log and the bunk log, preventing it from moving. Alternatively, long (8- to 12- inch) lag screws can be set in the end of the hewing log and screwed to the bunk log below.

Once your log is mounted, begin by marking out a square on each end of the log and snapping a line covered in charcoal ash along the length of the log. If you’re working alone, you can tie the string to a nail that you tap in to the corner of your square and pull taut while lining up the string with the corner at the opposite end. An alternative method uses a straight board to connect the lines of the square. This line serves as a depth gauge for a series of shallow notches, or juggles, cut approximately 1 foot apart. Once the juggles are cut, the hewer uses the broadaxe to remove large, dinner-plate-size slabs from the side of the log. This same process is repeated on the opposite side.

If the hewn timbers are for a barn, they can be left rough. If the timbers are to be used in a house, they can be further refined using an adze. The adze looks a bit like a hoe, with a long, square-headed handle and straight cutting edge that’s beveled toward the handle. By standing atop the hewn log and swinging the adze toward yourself, you’ll be able to slice paper-thin sheets of wood that leave the timber perfectly smooth. To protect your feet in this process, rock back on your heels so that the adze runs under your foot, and not into your toes! Finally, it’s worth mentioning that the square eye of the adze is intentional. Since the head is held on only by the force of the swing, the handle can be removed for sharpening, a task that would be nearly impossible with the handle fixed in place.

The depth lines for hewing were traditionally made using a string dipped in wood ash; consider using a chalk line or a straight board and a lumber crayon to connect the depth lines.

If you’re hewing a long log, you’ll have enough room to work safely with a partner, if you work at opposite ends. While one person cuts juggles on the top, the other person can hew the side.

Begin by standing on the opposite side of the log from where you plan to chop. If the log is larger than 10 inches in diameter, it will be most efficient to chop halfway through, and then switch to the other side. If you are on a hill, start on the downhill side and finish on the uphill side in case the log rolls. Make sure your feet are firmly planted and well outside of the axe’s path.

As in felling a tree, the most efficient chopping angle is 45 degrees, and the face of the scarf should be equal to the diameter of the tree, assuming you’ll be chopping from both sides. On smaller logs you can buck from one side; simply make the notch wider so that it doesn’t “vee out,” or close, before cutting all the way through the log.

Bring the axe directly over your head, dominant hand on top. Do not drop the axe behind your head; this creates fatigue, not additional power. As you swing the axe, throw it out to create a larger arc.

As with felling, use a clockwise pattern to remove chips. If you find that you’ve veed out before cutting entirely through the log, simply move your kerf to one side, giving yourself a fresh chopping face.

As you near the bottom of the log, use shorter, less-powerful swings to avoid contacting the ground.

While the early broadaxe was essential for forming square timbers used in post-and-beam construction, the froe played an equally important role, providing shakes for the roof and siding of early American homes. Froes can usually be found fairly inexpensively at barn sales, or you can fashion your own froe out of an old leaf spring or farrier’s rasp. Froes are different lengths for different purposes. Those that are used for making shakes and small log cleaving (splitting) have a single-bevel blade that’s 10 to 12 inches long. The eye of the handle is slightly tapered so that the froe’s head doesn’t fall off. Here’s how to split your first shakes:

While the mighty axe rightly receives credit for felling most of the timber of the 18th and 19th centuries, it was the peavey that took the work out of moving these logs, on both land and water. This important tool, consisting of a long handle with a metal spike and levered hook on the end, was the creation of blacksmith and inventor Joseph Peavey. Peavey was an industrious Mainer with a penchant for problem solving. Among Peavey’s inventions were the spill-proof inkwell, the wooden screw vise, the hay press, and the impressive Peavey hoist, which was known for yanking even the most stubborn oak stumps.

As the story goes, Joseph Peavey developed the namesake tool after watching several river drivers try to free a logjam on the Stillwater Branch of the Penobscot River in the spring of 1857. By modifying a cant hook so that it had a sharp point and a fixed-swing dog (hook), the peavey gave lumbermen a more efficient way to skid, deck, turn, and pry logs.

As fine an example of practical engineering as the peavey is (virtually unchanged for nearly 160 years), there’s still room for a couple of modifications that will yield greater efficiency on the landing and in the woodlot:

Add spikes. More spikes mean more contact with the log, ultimately making each stroke more efficient. By welding a second spike (often made out of an old railroad spike or a bolt) below the primary point, you’re able to develop an efficient rhythm, yielding more push per stroke.

Bend the point. By bending the point, you’ll create an angle that requires you to bend your body less and offers more contact with the log.

Make it a razorback. This modification, a series of points welded to the back of the peavey, has its roots in competitive lumberjack sports. The multiple points allow you to roll logs along the ground or up a log deck with ease.

Peaveys take the work out of moving logs. Note the addition of the razorback spikes to the peavey on the left; these create multiple push points and increase efficiency.

At some point you’ll find yourself in the woods with a hung tree (a felled tree that is suspended by one or more surrounding trees), but without a peavey to help lever the tree down. This method allows you to roll the hung tree using a homemade lever so that it falls to the ground. It goes without saying, but extreme caution is needed with this method.

Begin by sizing up the hung tree and determining which way it needs to roll.

Search out a strong 4-inch-diameter pole, 4 to 6 feet long. Make sure you cut this pole from a sturdy hardwood tree, because you’ll be using it as a lever.

Use the attack corner of your chainsaw (see Anatomy of a Chainsaw) to bore into the log about 1 foot above the hinge.

Now bore in the opposite direction so that you have a square hole to insert your pole into.

If the hinge is still connected, release pressure by slowly cutting the hinge fiber on the side opposite the direction of roll.

Leave the hinge wood connected on the near side to reduce the chances of kickback.

Push the tree away using the pole. Let go of the pole and continue down your escape route as soon as the tree begins to move on its own.

Bow saws can be used around the homestead in place of chainsaws for bucking firewood, cutting kindling, and clearing trails. Early bow saws were used by carpenters in post-and-beam construction. Later, the wooden bow saw was replaced by a metal bow saw that earned its spot in the woods cutting small-diameter pulpwood. These bow saws of the early and mid-20th century carried a 42-inch blade and measured 48 inches, including the handle. This meant that the bow saw was not only a handy felling and bucking tool but also the perfect measuring stick for cutting 4-foot pulpwood.

If you’d like to buck firewood for your homestead using a bow saw, choose a longer saw, such as the 48-inch version used by early lumberjacks. While these large bow saws are no longer commercially manufactured, they are fairly common at flea markets and barn sales. However, to be serviceable, the saw should have been stored without blade tension. A worn-out bow saw won’t have the proper tension and will likely result in a curved, dished cut.

When bucking with the bow saw, make sure you have a sturdy sawhorse or stanchion. The height of the wood you’re sawing should be about 36 inches. To saw, place your dominant hand on the lower handle and your top hand approximately 4 inches in front of the curve at the rear of the bow saw frame. If you’re using a sharp blade, you won’t have to apply much pressure at all. Rather, your job as sawyer is to keep the saw frame over the blade, and make long, full strokes. A 20-degree angle is about right for most sawyers; this allows you to stand comfortably without being hunched over. You may also find that rolling the saw slightly forward on the push stroke yields more efficient cutting. On the pull stroke, make sure the teeth are fully engaged so that you’re cutting in both directions.

Bow saws are also useful for maintaining trails and cutting coppice wood around the homestead. One advantage of using a bow saw instead of an axe when cutting saplings is that you’re left with clean, level stumps. With an axe, the remaining stumps are pointed, thereby posing a significant safety hazard. For basic trail maintenance and coppice harvest, opt for a smaller bow saw in the 16- to 18-inch range. These saws are inexpensive and endlessly useful.

The weight of the log hanging off the end will open the kerf, making it easier to saw the farther you cut. Think of it as a reward for your labor.

Perhaps no other tool is as valuable to the modern homesteader as the chainsaw. The chainsaw allows you to cut your own wood for building both human and animal shelter, efficiently harvest firewood, create pastures and silvopastures, cut fenceposts, build trails and woods roads, clean up after storms, and manage the ever-encroaching forest along pasture fencelines. The modern chainsaw represents a vastly improved product over earlier saws, which were dirty and extremely dangerous. Once you learn to safely operate a modern chainsaw, you’ll have the confidence to tackle trees, both big and small.

Developed in Germany by Andreas Stihl in 1926, the chainsaw has since evolved to be a safer, cleaner-burning, and more efficient tool. Among the safety features found on all quality modern chainsaws are an inertia chain brake, which stops the chain when it kicks back; a muffler with a spark arrestor; a rear hand guard; a chain catcher or catch pin; an antivibration handle system; and a throttle trigger interlock.

Collectively, these features reduce the risk of injury; however, understanding how a chainsaw works will help you avoid accidents. Essentially, you can think of the teeth of your chainsaw as consisting of alternate chisels that are able to efficiently cut wood when they’re both sharp and at the proper depth. The depth of your cutter teeth is determined by the raker. To maintain the chain, you’ll want to follow the manufacturer’s instructions regarding tooth length and angle, as well as raker depth. Aggressively filing the rakers in an attempt to cut bigger chips (by allowing the teeth to cut deeper) also increases the chances of kickback, where the chainsaw bar is rapidly pushed back toward the operator. You can reduce the chances of kickback by understanding the reaction forces of your chainsaw: push, pull, attack, and kickback.

You’ll note that the kickback position is the top corner of the bar. You should never attempt to saw directly with this corner of the bar. The lower corner, just below the kickback position, is the “attack corner,” used for boring into the wood. Learning to safely bore with your saw is important because it will allow you to plunge-cut as part of the felling process.

Before you ever think about firing up your chainsaw, you should invest in personal protective equipment (PPE). This includes head/face/ear protection, gloves, chainsaw chaps, and steel-toe boots.

An integrated forestry helmet combines an approved hard hat with face and ear protection, eliminating the need to buy and keep track of individual components. The cost of a hospital visit can be 100 times more than the cost of a pair of chaps. Without a doubt, this is a solid investment, since the most common chainsaw injury is a cut to the lower left leg and thigh. You’ll also want to wear steel-toe boots, preferably boots that are impregnated with ballistic nylon, since foot and lower leg injuries are fairly common as well. Finally, invest in a pair of quality gloves that fit well, offer good grip, and allow you to operate the on/off/choke switches without needing to be removed.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) goes from head to toe: note the helmet with face and ear protection, leather gloves, chainsaw chaps, and steel-toe boots.

Before you start your saw, you should conduct a preliminary check. Adhering to the following tips will reduce the chance of injury, increase your efficiency as a woodcutter, and make your time in the woodlot more enjoyable:

Ask any old-time woodsman how to fell a tree and you’ll likely hear him describe some iteration of the conventional 45-degree notch. Without a doubt, variations of this notch have been successfully used — and not so successfully used. The persistence of the conventional notch can largely be attributed to the use of the crosscut saws in the 19th century, in which the flat undercut was bisected by a 45-degree scarf using an axe. When loggers migrated from crosscut saws to chainsaws in the first half of the 20th century, the conventional notch continued to be used. However, the conventional notch suffers from two flaws.

The conventional chainsaw notch evolved from the days when trees were exclusively felled with axes and crosscut saws. Felling with a chainsaw allows us to improve upon the conventional method by employing a bore cut and a wider notch.

A narrow notch. The first problem is that its face, or notch width, is too narrow. As the tree falls, the direction of the fall is controlled only until the notch closes. Once the notch is closed, the hinge breaks off, leaving the tree to spin or split. For trees that are perfectly plumb, it isn’t so much of a problem for the tree to fall the remaining 45 degrees without the hinge. However, for a tree that has even a small amount of side lean, the tree can spin off the stump, heading in an unintended and dangerous direction.

A dangerous back cut. The second danger with the conventional felling approach is that the back cut is typically a single cut starting at the back of the tree and sawing toward the hinge. In many cases, the sawyer continues sawing until the tree begins to fall. Being in proximity to a falling tree with a running chainsaw can be dangerous — especially if, during the excitement of felling the tree, the sawyer cuts too far on the hinge and has to scramble to escape an ever-accelerating and uncontrolled tree. If the tree doesn’t fall under this scenario, there’s a good chance the saw is pinched in the back cut. At this point, not only do you have to contend with freeing your saw, you also have a partially cut tree that poses a significant safety issue.

Developed by Swedish foresters in the 1960s and brought to North America in the 1980s, a new notch, and an entirely new approach to timber harvesting, allowed the logger greater control and safety. The open-faced notch technique (cutting a notch with an angle of 70 to 90 degrees) offers greater control as the tree falls.

The following five-step felling plan offers a safe and systematic way to fell trees in your woodlot. While felling techniques could fill an entire book, this section is meant to serve as a primer on the topic.

While it is easy to assume your woodlot is a safe environment, a number of seemingly benign elements can pose a real risk to the sawyer.

Find the widowmakers. Do you see any dead or hanging limbs, either on the tree you’re felling or in the crowns of adjacent trees? These hazards are appropriately named widowmakers. Think about how these branches and limbs are likely to fall, and make sure your felling plan keeps you a safe distance away.

Remove obstructions. After you’ve surveyed the overhead hazards, examine the forest floor. Are there saplings in the path of the tree? If so, it’s easier and safer to remove them before you’ve felled your target tree. You’ll also want to make sure that the area around the tree is clear of other obstructions, including vines, undergrowth, fallen logs, and roots or holes that could be trip points.

Look for cracks and decay. Now that you’ve examined the canopy and ground for hazards, take a look at the trunk (or bole) of the tree. Does it show signs of decay? How about a split? These are important clues that speak to the soundness of the tree. If you suspect decay, you can drill or bore into the wood to determine if the tree is sound enough to safely fell. If your boring experiment only yields punky sawdust, select another tree to fell. In the event of cracks or splits, it’s important to note where they begin and end. If the crack extends into the base of the tree, it is best to leave it for wildlife and move on to a different tree.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the hazards don’t end as soon as the tree hits the ground. It is fairly common for still-swaying branches and limbs from neighboring trees to fall after your targeted tree is on the ground. Take the time to look up, note hazards, and wait for the surrounding crowns to settle down.

Front, back, and side lean all influence the ease with which, and the direction in which, the tree will fall. To determine the lean, don’t just look at the trunk of the tree. Stand far enough back that you can see the entire tree. In many cases, the trunk will sweep one direction, but the crown will go the other direction, which can either balance out the tree’s lean or persuade it the other direction, based on the size of the crown. When sawyers talk about “side lean,” they’ll often reference the “good” or “bad” side of the tree. The good side leans away from the sawyer; the bad side leans toward the sawyer. Given a choice, you should always work from the good side of the tree when making the back cut. Front lean means that the tree wants to fall forward; in this case it’s important to leave a strong hinge. For trees with back lean, it’s important to set large enough wedges so that the tree can be tipped. If a single wedge doesn’t offer enough height, stacking multiple wedges will often create the necessary mechanical advantage.

Few considerations are as important as picking a good escape route for the sawyer. Studies have shown that nearly 90 percent of felling injuries occur within 5 feet of the stump. This alarming statistic highlights the importance of choosing and clearing the best route possible. Your escape route should be 45 degrees back and away from the felling direction. Never use an escape route that is directly opposite the direction of fall, since the tree may kick backward. Remember to work on the good side of the tree, and make sure that you take the time to clear brush and any potential tripping points in your way.

While most trees offer two potential escape routes, you should always decide which route you’re going to take, and stick to it so that you never have to enter the danger zone. As a general rule, you should use the escape route opposite the direction of side lean.

Your notch is important for determining the felling direction, as well as for controlling the descent of the tree. Remember that the back of your notch becomes the front of your hinge. The width of the hinge should be 80 percent of the tree’s diameter. This means that if you’re cutting a 15-inch tree, the width of the hinge would measure 12 inches, side to side. Knowing this allows you to cut your notch at the proper depth.

The open-face notch should be 70 to 90 degrees. This angle means that the tree will fall all the way to the ground with an intact hinge, eliminating the potential for the hinge breaking and the tree kicking back, as is common with the conventional 45-degree notch.

You’ll begin the notch by sighting your felling direction. Most chainsaws have a built-in sighting line on the case that allows you to line up the saw with your intended target. With the saw pointing toward your target point on the ground, begin cutting at a downward angle of approximately 60 degrees. This cut should continue until you reach 80 percent of the tree’s width. You can now make an upward 30-degree cut that bisects the 60-degree cut. This will result in a perfect 90-degree wedge. Either of these angles can be shortened, but the final notch should be 70 to 90 degrees. It is also important that the two cuts meet; a bypass of no more than 3⁄8 inch is acceptable. The risk of a bypass cut is that either the tree may split (called a “barber chair”) or the hinge may break prematurely.

The 70- to 90-degree open-faced notch offers greater control in felling than the conventional notch does, because the hinge is less likely to break prematurely.

For your chainsaw to operate efficiently, the bar and chain must be continually lubricated. Until recently, virtually all bar and chain oil was petroleum based. Given that this oil is left behind on the stumps, limbs, and forest floor, it makes sense to consider using a plant-based, biodegradable bar and chain oil. In fact, many community watersheds require the use of plant-based oils to protect water quality. Most of these biolubricants use canola oil along with a tackifier that helps the oil stick to the bar, including additives that prevent the formation of sticky resins in your saw’s clutch.

If a tree is small or has no lean, wedging is unnecessary; simply cut your open-faced notch on the front, and cut straight in from the back.

On larger trees or trees with lean, you should employ the bore cut and set wedges about an inch above the center of the notch. It is extremely important that you use the “attack” corner (bottom corner) of the bar for the bore cut. Begin your bore cut at the apex of the tree, leading with the attack corner and pushing into the tree, parallel with the hinge. If your bar is longer than the diameter of the tree, it will saw through the far side (which should be the “bad” side of the tree). Bring the saw forward to adjust the thickness of the hinge. The hinge thickness should be 10 percent of the tree’s diameter. Assuming the same 15-inch-diameter tree, your hinge should be 1 1⁄2 inches. Maintain even hinge thickness across the width of the hinge. Once the hinge has been set, begin sawing away from the hinge. However, do not allow the saw to completely sever the back of the tree; leave a strap that is 5 to 10 percent of the tree’s diameter. This strap is important, because it prevents your saw from getting pinched and also preserves an opening, or kerf, for inserting the all-important plastic felling wedge.

With the saw safely removed, and your escape route clear, insert a wedge (or multiple wedges on larger trees) and pound it with the poll of your axe until it’s firmly set.

At this point, take the time to look down your felling lane to ensure it’s clear of people, dogs, or other woodland creatures. Once clear, cut the remaining strap 1⁄2 inch below the back cut. At this point, the lift provided by the wedges should provide enough upward force that the tree falls; in that case you should set your chain brake and walk (don’t run) 15 feet down your escape route. If the tree doesn’t fall after you cut the strap, use the poll of your axe to pound the wedges until the tree begins to fall. If you pound your wedges all the way in but the tree still won’t fall, stack multiple wedges (two, and then three if necessary) to create the needed lift.

For folks used to using the conventional “notch and drop” method, the reaction to the open-faced notch with the bore-cut hinge is always the same: “That felt so much more controlled.” This control means that not only are you safer working in your woodlot but you’ll also have a healthier woodlot. Hung trees and trees that break off the stump midfall often result in what foresters call “residual stand damage.” This damage may be bark scraped from a neighboring tree or crushed saplings as a result of imprecise felling with a conventional notch.

Some of the most useful lessons of tree felling come after the tree has hit the ground. You should examine where the tree hit in relation to your intended target. Were you right on, or did you miss? Was your notch properly sighted? Was your hinge too thick or thin? Being aware of these details and learning to refine your technique will make your woodlot woodcutting more efficient and enjoyable.

The bore cut is made by using the “attack corner” of the bar (see here) to bore into the tree. Make sure your hinge thickness is even and approximately 10% of the diameter of the tree, and that the back strap is 5–10% of the tree’s diameter. The more lean the tree has, the thicker the back strap should be.

On smaller trees, or those with little to no lean, one wedge is usually sufficient for felling. On larger trees you may need to use two or more wedges.

Cut the back strap about 1 to 2 inches below the bore cut. This lower cut allows the wood fibers to tear vertically, contributing to a slower, more controlled descent.

It’s essential to determine the height of the tree before you fell it, so that you know exactly where the top will land. To do this, you could dig around in your geometry memory bank to find the Pythagorean theorem. Or, if the ground is reasonably level, you could use the following simple trick:

Voilà! The distance from where you’re standing to the base of the tree is equal to the height of the tree. If you’ve calibrated your pace as described in chapter 1, simply pace the distance back to the tree and convert to feet.

Limbing, sometimes referred to as “chasing,” requires just as much skill as felling and is just as potentially dangerous. Two errors stand out as being particularly common when limbing a tree. The first is an error in judgment that occurs when the sawyer lets down his or her guard after the tree is “safely” on the ground. The problem is that in most cases unsuspecting sawyers simply trade vertical uncertainty for horizontal uncertainty, whereby the enormous potential energy of bound limbs presents a dangerous surprise. The second error is the temptation to go “just a bit higher” with the chainsaw in order to reach limbs that may still be above shoulder height. The combination of the chainsaw being outside the control zone (above the shoulder) and the limbs being under pressure can have disastrous results. However, don’t despair; by learning a few basic tricks of the trade, you’ll be able to negotiate the trickiest of limbs.

Before you begin limbing, consider the following hazards:

Limbing is the art of controlled pressure release. Understanding how pressure changes while you’re sawing in the kerf of a limb is essential to safe removal. If a tree is leaning with side pressure, you can use a limb-lock method that slowly releases the pressure. You accomplish this slow release by cutting about halfway through the branch on the compression side and then cutting the second half on the tension side several inches down the branch.

Spring poles can be particularly dangerous when the pressure is released too quickly and the branch flies into the face of the sawyer. The other danger is that the branch kicks the chainsaw back toward the sawyer’s upper body. To avoid this, release the pressure slowly by making a series of shallow cuts at the apex of the spring pole.

“Chop your own wood, and it will warm you twice.”

— Henry Ford

When bucking a tree with a chainsaw, as with limbing, compression and tension points will dictate how and where you buck the log. Complicating the bucking process is the likelihood that you’re probably looking to cut logs or other products from the tree, thereby needing to incorporate additional factors in the bucking process. These factors include minimizing the amount of sweep or curvature in each log; bucking out defects, including wounds that may indicate decay; and working within log specification guidelines that dictate minimum and maximum diameters over a given length (e.g., selecting logs for a log cabin).

Bucking on hilly terrain poses the danger of rolling logs. Therefore, you should make sure to always buck the tree from the uphill side and have an escape route. As a general rule, you’ll want to limb and then buck, starting at the butt of the tree and working toward the top. If the tree has compression on the top — meaning that your chainsaw would pinch if you cut directly down — use a notch-and-undercut method (see illustration below) to release the pressure. If, however, the compression point is on the bottom, as is often the case for suspended tops, use a bypass cut, where you begin on the bottom by cutting one-third to one-half of the diameter, and then cut the top with a 2- to 3-inch offset. This offset gives the energy a place to go, while safely allowing the log to sever.

To avoid pinching your saw while bucking, use a bypass cut: saw partially through the top, and then finish on the bottom. If you feel your saw beginning to pinch, stop and cut from the other direction.

Splitting blocks serve several important purposes. First, by splitting on a wooden block, you’re preserving your axe by avoiding rocks. Second, splitting on a block is safer since it gives the axe a known landing spot well away from your feet. Third, a splitting block can save you from having to bend over as far. Your back will thank you!

Begin by selecting a block that is a minimum of 15 inches in diameter and 12 to 16 inches high. The knottier, the better; the knots will prevent it from splitting prematurely. Any species will work, but I prefer elm or sugar maple.

Find an old tire that’s just slightly larger than the diameter of your block. Drill four 1-inch holes in one sidewall, evenly spaced (this will allow water to drain). Use four 3-inch lag bolts with fender washers to screw the sidewall of the tire to the top of the block.

You now have the perfect splitting block that will hold your wood securely as you split it. No more standing up fallen pieces or chasing runaway firewood!

If you’re splitting small-diameter wood, you can pack the pieces inside the tire; they will support one another while you are splitting.

Beside your tire-topped splitting block, you may want to have a second block without a tire for large or odd-shaped pieces. I also recommend putting a slight angle (about 10 degrees) on this second block so that you’re able to match an uneven piece of firewood with the angle of the block.

Because processing your own firewood is such a labor-intensive activity, it makes sense to plan out all the steps in advance to minimize the number of times you have to handle the wood. In constructing your plan, think about where the wood is harvested, what tools you have at your disposal, and options for getting the wood to the woodshed. (The instructions in this section refer to splitting wood by hand; don’t disgrace the wood by using a power splitter.) No doubt, the victorious feeling of splitting a stubborn log with only an axe makes it a fair fight and will always trump the monotony of pulling the hydraulic lever of a power splitter.

In some cases, it may make more sense to split near the felling site, since pieces of firewood are easier to load and move than large rounds are. Processing wood at the felling site reduces the damage to residual trees that often results from skidding tree-length logs. Finally, the detritus from the process (nutrient-rich sawdust, bark, and branches) is left in the woods and returns to the soil.

Splitting is different from chopping: with splitting, you’re bisecting the wood along the grain, instead of diagonally cutting it. Therefore, to effectively split wood, you’ll need an axe that works less like a knife and more like a wedge. Your first option is to convert an old felling axe into a splitting axe. Since you’re looking for a fat wedge to pop the wood apart, seek out a well-worn felling axe with a short face from being ground and abused. Use a flat file at a 40-degree angle on each side to create a blunt wedge. If the axe has been out of service for a while, make sure the handle isn’t cracked or loose.

Another option for wood splitting is a maul. The advantage of the maul is its mass, which allows you to power through the log with each blow. Mauls can range in weight from 6 to 16 pounds. But remember: what you gain in mass isn’t free. You’ll still need to lift the maul, which can be tiring. I prefer lighter mauls that allow me to work longer without getting tired. There are also several new hybrid mauls that incorporate the thin cheek of an axe with the thick poll of a traditional maul.

You’re not working on the railroad, so don’t roundhouse over your shoulder. Instead, raise the axe directly over your head. By keeping the axe in a perfect line with the center of your body, you’ll develop greater accuracy and precision.

Space your legs wide enough so that they’re free and clear of the axe should you miss. Also make sure you’re wearing steel-toe boots.

As you line up with the log, make sure you’re far enough away that you don’t “wood,” or strike the handle of the axe on the log. This happens when your arms and body are outstretched more during the actual swing than during the swing lineup.

Although standing farther back from the log can help avoid this, consider adding a handle saver — a rubber ring placed on the shoulder of the handle. The ring works as a shock absorber in the event of a missed hit. You can purchase a commercially made handle saver, or you can make your own out of a 3-inch section of rubber radiator hose.

As you bring the axe down, aim for the near edge of the log. It’s always easier to start a split at the edge than in the center.

If the log shows no sign of splitting after a couple of blows, rotate it 90 degrees and try from that side. If you still can’t manage to pop open the log, consider “slabbing” the log by removing inch-thick slabs. Once the slabs are removed, you can resume your regular splitting pattern.

The final option for splitting wood by hand is to use a sledgehammer and metal wedges. This method is particularly useful for splitting knotty logs with uneven grain. If you opt for this method, make sure your wedge is placed beside the knot, not directly in it. If the knot is at one end of the log, split it from the opposite end. Also, it’s best to start at the edge of the log and set additional wedges (if necessary) as you work toward the center. You may choose to use your axe or maul since much of the tension in the wood is released once the initial split is made. Some folks argue that splitting gnarly logs is too time consuming; however, remember that the reason the log is so tough is that the wood had dense, uneven grain. It is this dense grain that is richest in energy. In my own cabin, these pieces are coveted as “all-nighters” capable of pumping out consistent heat well into the morning.

When splitting wood, bring the axe directly overhead (instead of over your shoulder) to increase your precision.

Aim for the near edge of the block (not the center) to make splitting easier. Note the wide foot stance that allows the axe to travel between the legs in the event of a glancing blow.

While it’s hard to deny the value of a cord of wood for keeping you warm, cordwood can also be used as a simple and efficient alternative building material. Cordwood building is simple; debarked firewood-length logs (8 to 24 inches long) are stacked with an insulated mortar to create a wind- and watertight wall.

It’s imperative that the wood be completely dry before you begin, so start this process at least one year in advance of construction. Softwoods are generally preferred over hardwoods (which are prone to greater expansion/contraction); cedar is among the most desirable woods since it’s rot resistant. You can use either rounds or split wood; just make sure all pieces are cut to the same length.

Once your wood is dry and you’ve built a solid foundation above grade, you’re ready to mix your mortar. Like cooks, most cordwood builders have their own recipe, but this one is the most common: 9 parts sand to 3 parts sawdust to 3 parts builder’s lime (not agricultural) to 2 parts Portland cement by volume.

With the mortar mixed to the consistency of thick mud, you’re ready to begin building, or “laying up” the wall. Start with a layer of mortar at the base (about 2 inches thick), and press the cordwood until firmly bedded. The logs shouldn’t touch one another, and mortar should fill all the air gaps.

With your first course in place, you can begin continue building the wall layer by layer. Make sure the wall doesn’t bow in or out, and that the areas around door and window frames are completely chinked with mortar. Before the mortar dries you’ll want to smooth, or “point,” both the inside and outside of the wall using a butter knife with a slightly upturned blade. Use the knife to both smooth and compress the mortar, adding to both the strength and appearance.

It can take up to three weeks for the mortar to completely dry. It’s best if it dries slowly, and you can control the rate by misting the wall daily with water. (For more information on cordwood construction, see Resources.) See here for completed cordwood house.

Point the mortar between logs with a small trowel or a butter knife that has an upturned blade. Individual logs should not touch; they should be separated by a thick layer of mortar.

Sooner or later, you’ll find that you have a log you need to bring out of the woods to process, whether it’s a maple log that will be milled into a new kitchen counter or log-length firewood that you’d like to process closer to the woodshed. Skidding, or “twitching,” is the process of dragging logs. This section outlines the advantages and limits of four distinct skidding methods, starting with people power and ending with tractor skidding.

If your homestead woodlot is small, consider skipping the gym membership and skidding logs by hand. If you’re mostly cutting coppice wood or other small-diameter material, this is likely the best approach. The people-powered log-moving and skidding tools include pickaroons, timber carriers, chainsaw winches, and the hand-pulled skidding arch.

Also known as the hookaroon, the pickaroon consists of a 3- to 5-inch tapered hook mounted perpendicularly on an axe handle. You can stick the pickaroon in the top of a small log and drag it, or drive it into the end of a log to lift and drag at the same time. This is a handy tool for firewood operations, but it is largely ineffective for logs over 6 inches in diameter.

A pickaroon is ideal for dragging firewood. To release the log, lower it to the ground and push back on the handle.

A timber carrier is a two-person skidding device consisting of a 4-foot handle with a pair of swing dogs (hooks) in the center. The swing dogs work like a grapple, diving deeper into the log as more pressure is applied.

Using a timber carrier requires not only a strong partner but also good communication; make sure your partner knows when you’re getting ready to lift, drag, and stop.

When working in tight areas, the chainsaw winch can be a great way to skid trees short distances or to free a stuck tree from the surrounding crowns. The winch mounts on the bar studs of the chainsaw and is generally better suited to large, commercial-grade saws. To double the pulling capacity of the winch, consider using a snatch block (a pulley block with a side plate that opens to allow a cable to be inserted).

A chainsaw winch is ideal for moving logs in remote locations and tight operating spaces. It can also be used for other applications such as freeing stuck vehicles and hoisting logs in cabin building.

The hand-pulled skidding arch lifts one end (or in some cases both ends) of the log, making it possible for one person to move a log that weighs as much as 1,500 pounds. Pneumatic all-terrain vehicle (ATV) tires allow the arch to easily roll over the roughest of ground. If you opt for a hand-pulled skidding arch, make sure you have friends to help take turns with it; the work is rewarding but extremely tiring.

Given their popularity, all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) often offer a practical solution for removing logs from the woodlot. If you don’t already own an ATV and are considering purchasing one for logging, you’re better off selecting a large 4×4 model (500+ cc) since hauling and skidding logs requires a substantial amount of power. Also, because of the heavy hitch load, it may be necessary to add additional weight to the front of the ATV. Finally, make sure you use extreme caution when skidding with an ATV, particularly on uneven or hilly terrain. If you’re unsure about whether a load is too heavy, err on the side of caution and make an extra trip.

The three most common ways of skidding or hauling wood with an ATV are skidding pans or skidding cones, skidding arches, and forwarding or utility trailers.

Skidding pans are easy to make at home using an inverted car hood or a scrap piece of sheet metal. They offer an effective way to reduce drag on the front of the log; the curved front also allows the pan to glide over roots and rocks. The log is generally fastened to the pan by a chain and binder, and then chained to the hitch plate on the rear of the ATV.

Similar to the skidding pan is the skidding cone, which goes over the nose of the log, with a choker chain passing around the log and through the point of the cone, then to the ATV hitch.

Skidding cones prevent the end of the log from digging in, therby reducing soil disturbance and allowing for larger logs to moved with less horsepower.

Your next option to use with an ATV is a skidding arch. Currently, there are over two dozen commercially produced ATV arches. They vary greatly in terms of capacity, maneuverability, and choking/hitching setup. Some of the major considerations are described in the following paragraphs.

When pulling smaller logs with a skidding arch, you may be able to balance the load by hooking in the middle of the log. For larger logs, it’s a good idea to let the butt end drag; it will serve as a friction brake on hilly terrain.

Self-loading versus manual. Self-loading arches are designed to lift the load as the ATV operator drives forward. This works well either with smaller logs or larger ATVs. The primary benefit of self-loading systems is speed. Manual arches use a hand-crank winch to lift the log off the ground. This reduces the initial drag but takes more time to hitch up.

Choker chain versus log tongs. A choker chain is usually about 5 feet long with a slip, or choker hook, at one end and a needling pin at the other end to help feed the chain under the log. The advantage of the choker chain is that it allows you to bundle small logs in a single hitch. Log tongs offer the advantage of being able to grab and go. However, log tongs sometimes have difficulty holding hard or frozen wood.

Two- versus four-wheeled arch. Most arches are two-wheeled, meaning that unless a log is short and perfectly balanced in the center, the rear of the log will still drag on the ground. There are several four-wheeled carts on the market that allow for both ends of the log to be lifted, thereby reducing ground disturbance. The disadvantage of the four-wheeled cart is limited maneuverability, particularly when backing up to the log.

If the logs you’re hauling with your ATV are small, or if it makes more sense to process the firewood while in your woodlot, consider making or purchasing a durable utility trailer. In addition to hauling wood, a multipurpose utility trailer will find unlimited employment around the homestead.

The go-devil was likely developed by early homesteaders in Appalachia, though various iterations of this simple design can be found worldwide. The go-devil works much like skidding pan and skidding cone discussed previously. Lifting the nose of the log off the ground and onto a set of skids helps reduce friction and keep the log clean. A go-devil is suitable for either a single horse or single ox. Because it uses a chain instead of fixed shafts, the go-devil can be maneuvered in tighter spaces. Here’s how to make your own go-devil:

The nose of the go-devil is trimmed to act as a skidding cone that rides over obstacles and keeps the log clean.

For many people, animal power represents an attractive addition to the homestead, and with good reason. The thought of trading noisy machines for the jingle of trace chains, or dirty exhaust for nutrient-rich manure, seems almost too good to be true.

However, before you buy a team of Belgians or a yoke of Devons on a whim, you should evaluate both your time and your resources. Unlike tractors and ATVs, draft animals involve daily commitment with regard to their care and weekly, if not daily, commitment with regard to their training. The bond that develops out of close interaction pays dividends in the field and woodlot. A properly trained draft animal will respond equally well to verbal commands and driveline or goad (prod) commands. In the woodlot, where your hands are likely to be occupied with choker chains and other logging tools, being able to communicate verbally is essential. It makes working in the woods both more efficient and safer, as you need to be aware of hazards to both you and your draft animal.

If you’re serious about integrating draft animals into your woodland homestead, start by spending some time around folks who use draft animals. Horses are the most popular draft animals, followed by oxen. Other draft animals suited to small-scale woodlot tasks include miniature mules and goats.

Horses and oxen are generally run as teams; however, both can be run singly. Most of the work on my woodland homestead is done is with a 14.2-hand Haflinger horse who’s able to skid a 12' × 14" log with ease. I move smaller coppice firewood by bundling multiple stems, making the operation more efficient. Using a single horse means not only a lower feed bill but also access to tight locations. It isn’t uncommon for us to skid logs between trees that are less than 3 feet apart without causing damage to the trees on either side. Ground skidding is done with a singletree in winter and a “go-devil” when the ground is soft or muddy.

Logging with draft animals is the ultimate challenge in multitasking. You must be aware not only of the regular hazards associated with logging but also of a host of other potential hazards related to your animal. Here are some basic tips to help keep you and your animal safe while working in the woods:

While the decision to incorporate draft animals into your woodland homestead should not be made lightly, the rewards come in the form of personal enjoyment and a healthier woodlot. The hooves of draft animals cause much less soil compaction than the tires of tractors or ATVs. And whereas engine-powered machines may leak fuel or hydraulic fluid, animals leave behind only organic fertilizer, free of charge!

If the thought of using draft-animal power is appealing but you’re not ready for the commitment of adopting a set of hooves, consider hiring a horse logger to work your property. Depending on your skills, the logger may be willing to take you on as an assistant, bucking or decking logs, and just maybe you’ll get to try your hand at driving. Being around draft animals on your property will give you a good idea if draft animals are right for you and your homestead.

If you already own a compact tractor, you’re well on your way to skidding wood. Your options vary from inexpensive and low-tech to spendy and high-tech.

The most basic way to skid wood with a tractor is to simply bundle, or “choke,” it with a chain that’s connected to the drawbar of the tractor. As with other skidding methods, this basic approach can be improved by using a skidding pan, skidding cone, or go-devil. Not only will this keep your logs cleaner but it will reduce drag and soil disturbance along your skid trail.

If your tractor is outfitted with a three-point hitch, you have several options that will make skidding easier and more efficient. The most basic approach is to attach a grab hook to your drawbar, hitch the skid chain to the drawbar, and raise the drawbar. Depending on your tractor, you may find that your drawbar doesn’t provide enough lift. A second option is to either purchase or fabricate a three-point-hitch skidding plate. This serves two purposes: first, by using the top link of the hitch, you’re able to pull logs higher off the ground, and second, the lower portion of the plate prevents the log from riding under the tractor.

The tractor skidding methods described so far work well on level ground. If your woodlot is hilly, you’ll want to be extremely careful and consider using a logging winch, which will allow you to pull the log to you (up to 200 feet) instead of driving over hilly or uneven ground to get to the log. While logging winches are expensive, they’re worth their weight in gold. Because they are so powerful, one danger is that as you go to winch the log in, the front of the tractor could raise off the ground or even flip. Always err on the side of smaller loads. As one experienced old-timer told me, “I always chain the front of my tractor to a nearby tree when winching. . . . It’s cheap insurance.”

The three-point-hitch tractor winch is also useful for winching hung trees or freeing yourself from a mud hole. The blade on tractor winches can also be used to push logs into a pile (decking) or to smooth out ruts in a trail. Winches are available for tractors from 17 horsepower up; just make sure your tractor and winch are appropriately sized for the wood you want to skid.

For many woodland homesteaders, the entry point to milling their own wood begins with a trip to the lumberyard, followed by sticker shock that’s akin to being hit over the head with a two-by-four. However, the decision to begin milling your own wood can represent a significant investment of both time and money, despite the potential savings. To help guide you through this process, consider the following points.

The scale of your homestead woodlot and the length of your building project list will help you decide if purchasing a mill is in your long-term interest. If the scope and scale of your home-grown lumber ambitions is limited to, say, a chicken coop and a new woodshed, you may want to consider hiring a portable sawmill operator to mill your wood on-site. While you’ll still have the satisfaction of harvesting your own wood, you’ll avoid the overhead, maintenance, and depreciation associated with sawmill ownership. Portable sawmill operators generally work on either a per-hour rate or a board-foot rate. These rates will vary greatly based on local competition, distance traveled, wood species, site access, and volume of wood to be sawn. Other operators work on what’s known as halves, meaning that they’ll mill your wood in exchange for half of the milled lumber. If you have a surplus of logs, this barter system may just be the ticket to getting your wood milled on the cheap.

If your lumber needs are modest and you’re interested in doing the work yourself, you may want to consider a portable chainsaw mill. These mills are a small fraction of the cost of a portable band saw mill and can be used with your existing saw, assuming it’s at least 60 cc. Smaller saws don’t have the power to run a ripping chain, which is necessary for sawing in line with the grain. Also be aware that the kerf, or width of the saw blade, is significantly thicker on a chainsaw, meaning that you’ll end up with more sawdust and fewer boards. It’s worth mentioning, though, that the chainsaw mill is the most portable of all sawmills. I once helped build a remote cabin in southeastern Alaska where all of the wood was milled using the appropriately named Alaskan chainsaw mill. Given that the building site was a 10-mile hike from the nearest road, trailering a portable band saw mill was out of the question. The chainsaw mill, which we strapped to our backpack in two pieces, was just the ticket.

Consider a portable chainsaw mill if your project is particularly small, or if it’s located in a remote area where the logs can’t be extracted for milling.

If you’ve decided that your woodlot ambitions are best met by purchasing a portable band saw mill or circular mill, you’ll be met with a wide range of options and price points. There are several portable circular sawmills on the market; however, most are band saws that use inexpensive, narrow-kerf band blades. The power plants for band saw mills range from 6 to more than 70 horsepower and vary in terms of their production potential from 200 to 1,500 board feet per hour.

You’ll also want to decide if a trailer-style portable mill is preferable to a ground-based unit that’s usually brought to the sawing site in the back of a pickup truck and then set up near your log pile. A trailer-mount portable sawmill is faster and easier to set up, but it poses the disadvantage of having to lift or roll the logs onto an elevated deck instead of working at ground level. One final advantage to ground units is that they allow multiple sections of tract to be bolted together for sawing long timbers, which is helpful in post-and-beam construction as well as making long, two-sided cabin logs.

Attending a local agricultural fair is a great way to see portable sawmills in action and learn more about the relative advantages and disadvantages of each model. One important consideration will be the size of the wood you’d like to saw, which should be matched to the capacity of your sawmill. Inevitably, many sawmill owners try to make do with a smaller sawmill — a decision they regret as soon as they realize the tree they just felled is too big for their new mill.

A trailer-mounted portable sawmill offers the benefit of fast, on-site setup, but loading the logs can be more of a challenge than with a ground-mounted sawmill.