Fauna, Fodder, Fuel, and Furniture

Of all the forestry techniques available to woodlot owners, perhaps no other method is more underused than coppicing. Coppicing is a reproduction method whereby a tree is cut back periodically to stimulate new growth through dormant buds on the “stool,” or stump. In turn, these buds develop into shoots capable of growing firewood and a host of other products in just a few years, instead of decades.

Bogget. A craftsperson who uses green wood, primarily from coppice harvests, to produce rustic goods.

BTU. British thermal unit. A unit of energy equal to 1,055 joules. Commonly used to express the stored energy of firewood.

Coppicing. A method of reproducing trees through dormant harvesting that encourages continual growth of multiple stems for a variety of wood products.

Face cord. A stack of firewood measuring 8 feet long, 4 feet high, and 16 inches deep. In other words, one-third of a full cord.

Faggot. A bundle of sticks lashed together and traditionally used to produce a small, hot cooking fire. Modern uses include erosion control and streambank stabilization, where the faggot bundles act as a barrier to keep soil in its place.

Full cord. A stack of firewood measuring 8 feet long, 4 feet high, and 4 feet deep.

Layering . A method of vegetative reproduction in which branches root once in contact with the ground.

Maiden. A tree that has never been coppiced.

Mast. Fruit or nuts produced by trees.

Pleachers. Partially severed saplings grown at an angle to form hedges.

Pollarding. Aggressive pruning of a tree’s upper branches to encourage dense head growth. Historically used for producing animal fodder and living fences.

Rhizosphere. The narrow region of soil that is directly influenced by root secretions and soil microorganisms, including fungi.

Shredding. (Also called “snedding.”) Removing the lateral branches from a main stem for kindling or animal forage.

Standard. A single-stemmed crop tree, usually reserved for mast or lumber.

Stool. A living stump from which new coppice stems will grow.

Sucker. A vegetative sprout originating from rootstock.

Teller. An acceptable growing stock in the sapling or pole stage capable of becoming a desirable standard.

Underwood. Coppice trees in the understory.

Coppicing as a forest management technique dates back to the Neolithic period, when coppice wood was used for a variety of purposes, ranging from bean poles and lath to firewood and fenceposts. In fact, the economic importance of coppice firewood was so significant that Henry VIII required fences to be built to protect coppice forests throughout England. However, over the last century, Britain has lost more than 90 percent of its coppiced woodlots because of land conversion, abandonment, and modern forestry techniques that favor longer rotations and a focus on industrial lumber production instead of utilitarian products for use around a smallholding.

In North America, coppicing has been a rather limited practice, not because of ecological limitations but simply because the vastness of early North American forests didn’t necessitate efficiency in growing trees, only in harvesting trees. This stands in contrast to Britain, where prehistoric settlement, larger populations, and a smaller land base forced rural communities to develop more efficient land-use methods, including coppice forests.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in coppice forestry throughout Western Europe. The British Forestry Commission is currently promoting the restoration and rejuvenation of forgotten coppice forests. In fact, this renewed interest in coppice systems has led to the development of a new research area known as short rotation forestry (SRF) and generally refers to wood that is between 8 and 20 years old. The renaissance has come about in part because of demand for the wide variety of products that coppice forestry produces and in part because of the role that coppice forestry plays in the rural economy related to nontimber products such as baskets, bean poles, fuel wood, and charcoal.

While the historical dependence on coppice systems is limited in North America, their potential for application is great, particularly at the homestead level. Central to making this transition will be a change in the way we view forests: not as simply vertical lumber yards or, conversely, as preserves where resources are left unmanaged. Somewhere between these competing paradigms is a more utilitarian view that sees coppice forests as a way to fill your woodshed, toolshed, and larder.

Certainly, the most obvious advantage of coppicing is rapid growth, thanks to the already established rootstock. This regenerative advantage eliminates the need for a tree to allocate significant resources to germination and root development and instead focuses the tree’s energy on developing rapid vertical growth in the form of shoots. In many cases, this means that you can harvest a tree in half as much time as an equivalent tree grown from seed.

Because coppice forests depend on healthy root systems, sound management of these forests also prevents erosion in the surrounding landscape, thanks largely to the stability afforded through a healthy rhizosphere capable of developing into a well-anchored mat of latticed roots.

As a forester, I’m often asked how long it will take for a tree to grow to a specific size. If I know something about the site, I can make an educated guess. However, more often than not, there are too many factors at play to make any sort of reasonable estimate, since both environmental and genetic factors influence growth rates. Environmental factors include climatic conditions as well as soil quality. Primary genetic attributes include vigor, disease resistance, photosynthetic efficiency, and, of course, species. Almost without exception, some species will grow faster than others, even in a less suitable environment. Willows, for example, will almost always outpace oaks in terms of growth rate, while beech trees in a northern hardwood forest are notorious for outcompeting maples and birches, creating thick single-species stands.

Because of this natural variation, it is important to avoid broad generalizations regarding yield. However, despite the many variables, coppice systems offer two clear benefits over trees grown from seed. The first benefit is reduced establishment time, meaning that you need not wait for a seed to germinate, establish, and develop a full root system. The second benefit is that since coppice trees form multiple stems, instead of a single stem, you have the opportunity to grow significantly more wood.

The following example illustrates how coppice firewood production stacks up against trees of seed origin. All of the trees in this case study came from the same site, so as to minimize variability.

First, I cut down a 40-year-old American beech tree with a single stem, likely established from seed. The tree measured 8 inches diameter at breast height (DBH) and yielded one face cord. As a point of comparison, I then harvested coppice-grown trees (with three to four stems each) to see what it would take to equal the same wood volume. The harvest included two 15-year-old coppiced gray birch and one 18-year-old coppiced American beech — all of which produced one face cord. In other words, equal wood production in less than half the time.

While this isn’t a perfect comparison (gray birch has fewer BTUs than beech, and this 40-year-old teenager of a beech was just entering its most productive growing years), the example stands as a testament to the production benefits associated with coppicing.

Depending on the conditions of your woodlot, you’ll be either establishing new coppice stools from maidens or tending a long-forgotten coppice stand that may or may not have been created intentionally. Either way, the methods outlined in this section will serve as your blueprint for improving the health and productivity of your coppice woodlot.

To begin, it’s important to choose trees that are well established (4-inch base diameter minimum), since the diameter of the stool being coppiced is proportional to the number of shoots that can be produced. In other words, larger stumps have the potential to produce more wood. At this point, being able to refer to your woodlot inventory will be important (see chapter 1). The information you collected about the species, size, and health of the trees will help you make informed management decisions.

The shoots that eventually develop in a coppice system usually originate as dormant buds located under the bark at the base or side of the stump. Shoots can also be adventitious buds that sprout from callus tissue that forms between the bark and the cambium (the layer of active cell growth just under the bark) at the cut surface. Generally, dormant buds forming at the base or side of the stump are healthier and more vigorous

While coppicing can be done any time of the year, your best results are achieved when the trees are dormant: between late fall and early spring, prior to leaf-out. Select trees with poor form that have little value as saw logs or other forest products. Quality, defect-free single stems should be considered for use as standards (see here).

A low stump encourages the establishment of new shoots at or below ground level; this promotes the development of roots and increases the tree’s stability. The ideal new coppice stool should only be 2 to 3 inches above the ground and should slope slightly to shed water. If possible, cut the stumps at a south-facing angle, to minimize the potential for rot. It is also worth noting that some studies have shown that higher stumps produce more shoots initially, but the trade-offs of decreased vigor over time and lack of stability suggest that lower stumps are still more preferable.

If you’re harvesting a previously coppiced stump, make the same angled cut just above the point at which the stool splits into multiple stems. It is important that the cuts be clean, with no separation of bark from wood. In order to achieve this clean cut, make sure your saw is sharp and fell the tree at knee height, then trim the base at the appropriate angle. This method not only ensures a clean cut but also leaves you with a firewood-length trim piece.

If you live in an area that is prone to animal browse, I recommend placing branches around the stool as a deterrent. Another approach is to develop a coppice system using species that are less palatable to browsers. Beech and birch, for example, are less likely to be browsed than maple and oak.

The size of your woodlot will determine the appropriate method for deterring browsers. On smaller sites, fencing the entire area to protect new growth may make sense. At a larger scale, fencing may be cost prohibitive. In that case, you may want to consider harvesting larger areas as a means of deterring wildlife (because most wild animals prefer to forage in small gaps in the forest or along the edges of a large open area).

A British Forestry Commission study determined that harvests larger than 1 hectare (2.47 acres) were more effective at deterring wildlife browsing than smaller group-selection arrangements (essentially miniature clear-cuts). If browsing threatens the establishment and growth of your coppice woodlot, consider hunting or trapping as a means of controlling the damage (and filling the soup pot at the same time).

In early spring you’ll begin to see numerous sprouts emerge from the stump, forming a J-shaped leader. After leaf fall, clip off the smaller, less vigorous sprouts. On average, leave four to six sprouts per stool.

Since not all tree species are well adapted to coppice reproduction, it’s important to select species that have a proven record of efficiency and productivity. The following chart outlines those species that are most suitable for coppice production, along with their potential uses. Often, trees of various species that are within the same genus can possess similar wood qualities and uses. These interchangeable species are identified by the abbreviation “spp.”

The amount of time it takes to produce your first firewood crop will vary depending on species, site, stool size, and desired firewood diameter. I’ve established my coppice forest in such a way that I’ll be able to harvest in 8- to 12-year cycles. For my more productive trees, this will yield firewood that’s 3 to 4 inches in diameter — small enough to avoid splitting. The beauty of coppice production is that if you maintain trees in a juvenile stage, they will never die of old age.

If you’re establishing a coppice woodlot primarily for firewood production, realize that in many cases there’s an inverse relationship between rate of growth and the energy potential of coppice species. If we were to rank four common species in terms of estimated growth rates, and compare those growth rates to their energy potential, we’d see that as a general rule, slower-growing trees have more BTUs. It is important to be aware of this time/energy trade-off whether you’re trying to decide which species to coppice or purchasing firewood and faced with the question of which species will yield the most heat per dollar.

The long history of coppicing in European forests has provided a surplus of data regarding species’ ability to coppice over the long term and optimal coppicing diameters unique to European species and growing conditions. Because coppicing has been so limited in North America, relatively few studies have focused on coppicing species native to the continent. One exception would be a seminal 1967 U.S. Forest Service study, which revealed important differences between sugar maple and red maple in terms of sprouting capacity and size. In sugar maple, for example, sprouting capacity was found to be greatest in smaller trees and became limited by the time a tree reaches the 12- to 14-inch DBH class. In red maple, sprouting was found to increase up to the 10-inch DBH class but remained a steady sprouter through the 20-inch-diameter class. This sort of species-level data can be extremely useful in guiding your coppice strategy.

In the event that species-level coppice data doesn’t exist for the trees in your woodlot, there are several considerations that hold true for most species. First, avoid very young trees and old growth. Sapling-stage trees may lack the necessary root structure and carbohydrate storage capacity to successfully coppice. You should also avoid mature trees, particularly those with thick bark at the base. One of the primary functions of bark is to protect the tree’s cambium; however, as the bark thickens, it becomes more difficult for the dormant buds to stump-sprout.

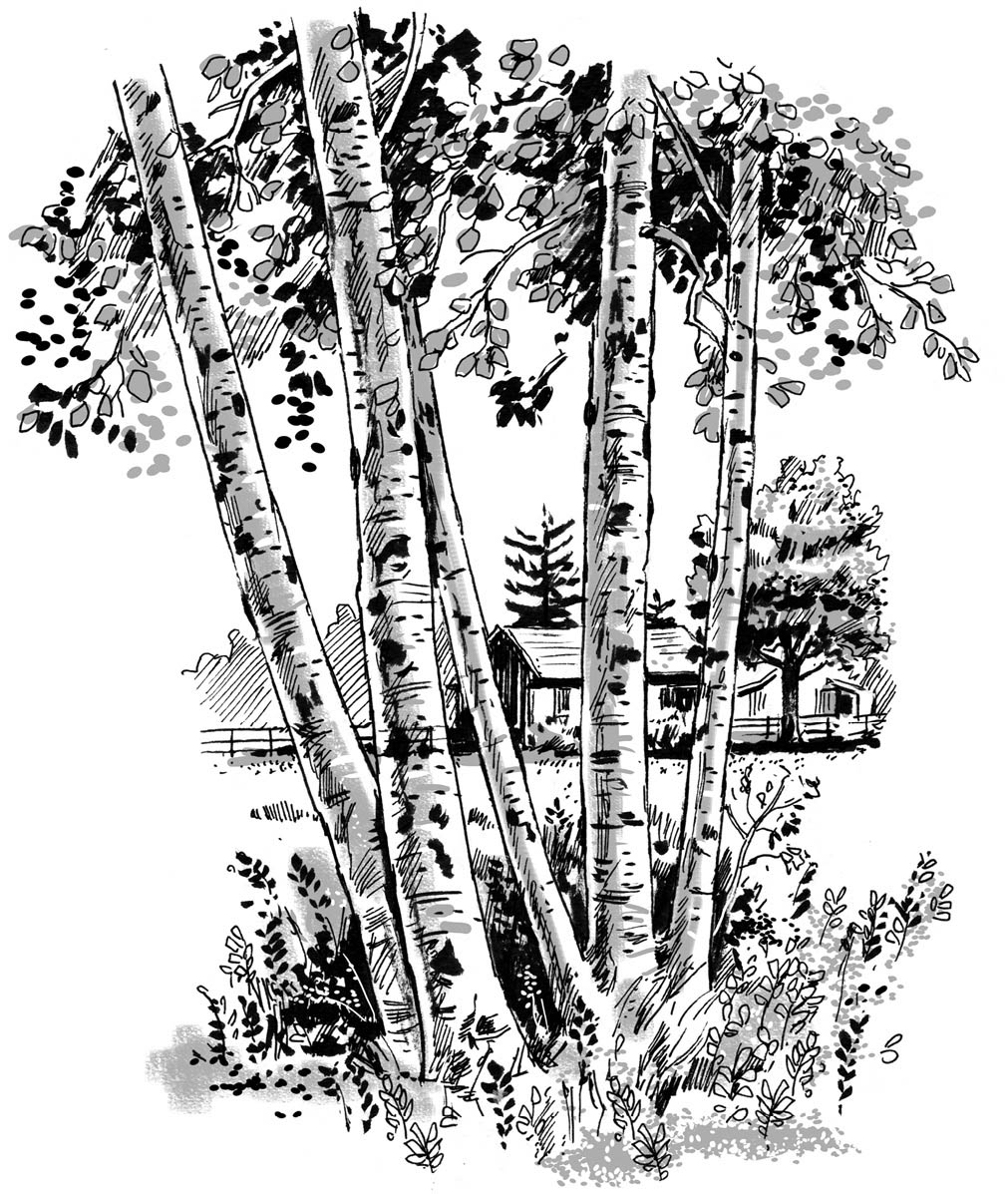

This group of birches is actually two trees. In this case, I opted to coppice the three-stemmed clump on the right.

Here is the birch stool 10 weeks after coppicing. You’ll want to retain the most vigorous sprouts, removing less vigorous sprouts as soon as the tree goes dormant.

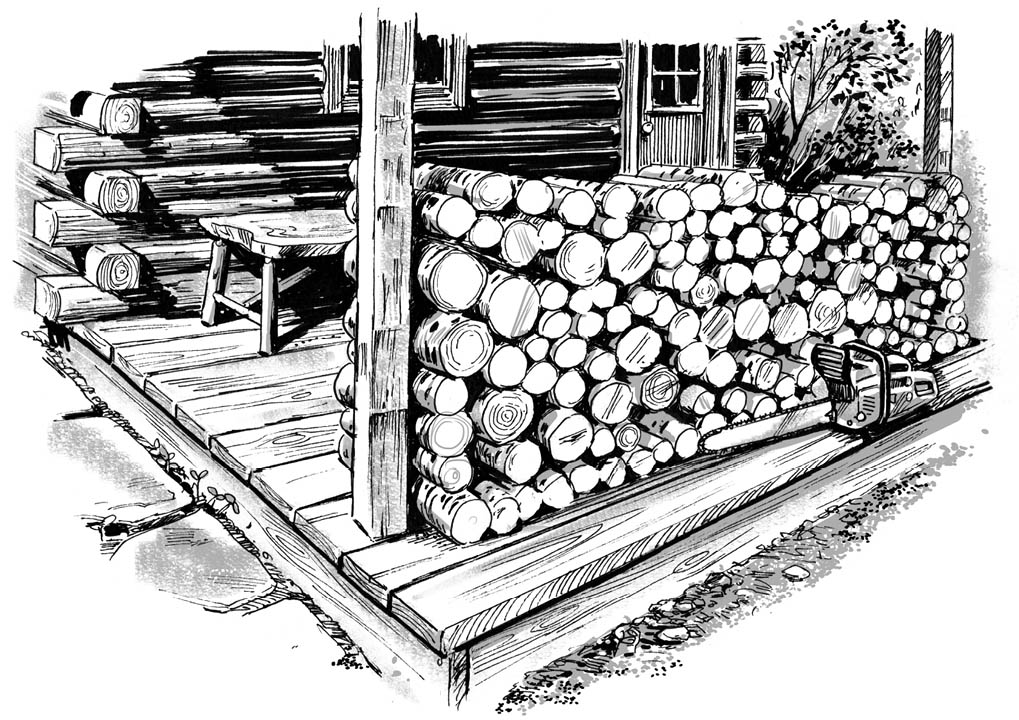

Two 15-year-old coppiced gray birches and one 18-year-old coppiced American beech add up to a face cord on my porch.

So far, we’ve primarily discussed stump coppicing as a means of producing vegetative sprouts. However, it is important to note that two other vegetative reproduction strategies exist: layering and root suckering.

Layering is a relatively common reproduction method, particularly in spruce forests. When a lower branch or bough comes in contact with the forest floor, the tree is able to set roots off the dormant branch bud and is thereby capable of independent growth after separating from the parent tree. Because the limbs of spruce trees grow in whorls, this can lead to the forest developing in a concentric pattern from one successive generation to the next. The trees that develop through layering are typically single stemmed and are genetic clones of the parent tree. One common homestead application of layering is the construction of hedges, or living fences, as described in chapter 5.

Root suckering is a process whereby dormant buds of shallow roots send up a single leader, which, as in the other asexual reproduction methods, is a clone of the parent tree. Relatively few species root sucker, though two notables are American beech and aspen species. One distinct advantage of root suckering over traditional stump sprouting is the relatively even spacing that results, since the sprouts follow the root mat instead of originating from a single coppice stool.

Essentially the same management practices can be used to encourage both root suckering and stump sprouting. Suckering is encouraged by cutting the parent tree during dormancy. The tree’s survival response is to use the stored energy in the roots to grow root suckers and stump sprouts at the same time. For species that do actively sucker, prescribed fires can encourage suckering vigor. However, harvesting parent trees during dormancy still appears to be the best method of encouraging root suckering. In one study, an aspen stand cut in winter produced four times as many root suckers as one cut during summer. In light of this, you should plan your harvest schedule carefully.

Every woodlot needs tending, especially those that have been neglected for quite some time. The time you spend in the woods maintaining your coppiced trees can be combined with other tending operations that will allow you to rejuvenate your woodlot and achieve a broader range of goals, like timber production or wildlife habitat improvement. Among the most important aspects of managing your woodlot are tending activities that focus on improving the quality of the trees and your woodlot by ensuring that your acceptable growing stock (AGS) has the light and growing space it needs.

Think of tending as the maintenance program for your forest, which can be timed to coincide with other activities like cutting firewood, thinning coppice sprouts, or harvesting fruit in your woodland orchard. These tending operations include release treatments, thinning, and pruning.

The goal of a release treatment is to free relatively young trees (seedlings and saplings) from competing vegetation. The treatments include weeding out competing seedlings (usually by mowing); taking down competing trees of the same size (selecting healthy, well-formed, well-spaced trees to leave behind); and removing larger, overtopping trees to allow more light for the saplings below.

Thinning is similar to a release treatment; however, it’s targeted at trees past the sapling stage. The goal of thinning is to give each crop tree the room it needs to grow, with the goal of improving the overall quality of the stand. Two thinning methods commonly employed in woodlot management are low thinning and free thinning.

Low thinning aims to mimic natural thinning processes that result in larger trees shading out smaller ones, leading to the establishment of distinct crown classes, which create a multilayered forest. To do this, remove suppressed and intermediate trees that likely wouldn’t be able to compete with more vigorous surrounding trees. In essence, low thinning aims to speed up natural forest succession by removing trees that are unlikely to survive but are still occupying valuable growing space.

Free thinning focuses on the development of evenly spaced, selected trees known as alpha stems, which are usually retained until maturity as crop trees. Any other trees that threaten the alpha stems are removed to eliminate competition. Unlike low thinning, which is focused on removing competition in the lower canopy, free thinning promotes the removal of both lower canopy trees and larger crown trees to create ample growing space around individual crop trees.

The creation of clear, knot-free wood is the most common reason for pruning. Unpruned branches create knots, which not only compromise the strength of the wood but also create uneven grain that can be difficult to work. Once a branch is pruned and the wound has healed, the tree will begin growing new layers of wood that are clear and free of knot disturbance. As a general rule, the sooner you prune a branch, the better. Smaller branches create smaller wounds, which serve as less of an entry point for insects and diseases.

Some species, such as most pines, are self-pruning. This simply means that the lower branches die in the shade created by the crown above. After several years, these branches shed naturally. However, if they can be pruned while they’re still alive, the tree will heal faster and will have a smaller knot.

The defect that results from a dead branch becoming encased in living wood is known as a black knot and generally represents a fairly serious structural flaw should that wood be used as lumber. This is because the live wood growing around the dead branch (stem wood) can’t bind as well as cells of a living branch that’s encased with living wood. As wood dries, the moisture differential between the dead knot and the surrounding wood often results in the black knot loosening and eventually falling out. This obviously compromises the strength of the wood.

“Red knots,” which are named for being red-tinged in conifer species, represent live branches that have become encased in stem wood. This interface of live cells between the branch and stem wood bond so strongly that these knots rarely fall out of lumber and, structurally, are only second to clear, knot-free wood.

While you may not always have the chance to remove live branches, you should still prune your crop trees regularly. Research has shown that pruning can in some cases reduce the prevalence of disease in forests by increasing air circulation and providing fewer hosts (in the form of dead branches) for forest pests. In the western United States, pruning can be an important technique for managing wildfires, simply by removing dead branches that act as ladder fuels.

Finally, if you’re fortunate enough to have fruit trees on your homestead, pruning is an import aspect of encouraging bountiful fruit production. Specific pruning techniques are examined in chapter 6, and pruning tools are discussed in chapter 2.

The star pattern on this log represents a branch whorl that was pruned, allowing clear, knot-free wood to grow on the outer rings.

To promote greater biodiversity than what exists in traditional, even-aged coppice systems and to produce a wider range of goods for the homestead, consider coppicing with standards — trees with a single, upright clear stem. This is a hybrid system that combines the production of young coppice trees alongside standards that are grown from seed and allowed to mature into mast producers and eventually timber.

The primary benefit of coppicing with standards is that the woodlot is able to produce goods both annually and over longer periods of time. Historically, American forestry practices have focused on creating quality timber, a goal that in many cases isn’t realized within a human life span. The discipline and commitment to the future this requires are certainly admirable qualities, especially given our penchant for instant gratification in modern society. However, a forest or woodlot need not simply be a gift to the future. It’s hard to imagine a scenario as rewarding as harvesting firewood, fruit, nuts, and craft materials annually in a woodlot among standards that may one day become the wood for your grandchild’s home. It is this vision that has led to exploration of alternative hybrid methods.

Intentional development of coppice with standards dates back at least 1,000 years in the British Isles. In most cases, the standards were planted from the mast of well-formed dominant trees. Oaks and beeches were most commonly planted as standards and were usually grown in a semigeometric pattern to ensure efficient use of space and access to sunlight. Because of the importance of efficiently managed woodlots to the self-sufficiency of Britain, the government historically enforced a rule that required 8 to 20 standards per acre.

In this kind of system, standards occupy the forest overstory, and the understory is managed for coppice products. These two distinct crops can coexist easily, as long as the understory continues to receive adequate sunlight. Maintaining sufficient levels of light on the forest floor is achieved through both the pruning of standards and their occasional removal. At the homestead scale, you have the benefit of being able to remove and use a single standard; at a commercial scale, the inefficiency associated with removing a single tree is usually cost prohibitive.

To be clear, methods like coppicing with standards and the other intensive approaches to woodlot management described in this book should be conducted not simply for the goods they supply but also as a labor of love. Removing a single standard or handling smaller coppiced firewood represents a commitment to working the land, which is rewarded in products but also through the development of your woodland eye and a newfound appreciation for your homestead woodlot.

In time, your vision will sharpen and you’ll notice details that were once lost among the brambles. You won’t be able to help yourself from noticing which trees leaf out first or where in the woodlot the deer bed at night, or maybe you’ll finally see one of those spring peepers that up to this point you had only heard. You may also find that your homestead woodlot becomes the larder where you run to pick mushrooms or hang buckets each spring to gather sap for boiling into syrup. In your relationship with your woodlot, you’re the steward. And like all other meaningful relationships, this one takes time to develop.

Before you begin clearing your existing woodlot just so you have space to plant standards, consider what’s already there; you may be surprised to learn that potential standards already exist. As you review your woodlot inventory, note the large-diameter trees categorized as AGS. Potentially, these trees may represent standards if they are large and of good form, or future standards known as tellers if they have the potential to become standards over time. Importantly, the standards and tellers you select should be climax species, capable of becoming strong, healthy veterans.

This forest demonstrates coppicing with standards. The multistemmed trees were all grown from coppice stools and the medium-size, single-stemmed trees are tellers that will eventually grow into standards capable of producing valuable lumber.

If you have a large number of trees, or multiple species capable of achieving standard status, it will be important to carefully consider your long-term goals. Unlike coppicing and other understory activities focused on annual cropping or short rotations, the standards represent a long-term investment. What might you like to use the standards for in the future? Building a timber frame barn? Making cabinets or other furniture? Growing a cash crop to pay for your child’s college tuition? Or maybe the anxiety of the future is too much to consider — maybe you’d prefer to have standards that could be sold someday but in the meantime are simply a source of nuts or syrup (which can be produced from a surprising number of species).

The successional stage of your woodlot will determine how you treat the tellers or standards. In a very young forest, it may be difficult to tell who the future stars are — those that are capable of achieving standard status. However, once trees reach the pole stage, natural thinning will have reduced some of the competition, thereby making the identification of tellers more obvious. Think of these trees as being in their most formative teenage years; this is the point at which their future success will be determined. As with human teenagers, the tendency is to try to give the budding tellers all the resources they need to thrive.

In the case of trees, the resource most often in demand is freedom, manifested as ample growing space. However, freedom for a tree can be as dangerous as freedom for a teenager. The tendency for tellers and aspiring standards is to respond to increased growing space by developing more branches. If the primary use of your standards is some purpose besides eventual lumber production, this may not be an issue. If, however, your goal is to ultimately harvest tall, straight timbers for a barn or clear lumber for kitchen counters, training these trees to grow upward instead of outward is key.

To train your tellers and standards to reach for the sky requires a bit of persuasion in the form of healthy competition. When you’ve identified a tree that’s a good teller or potential standard, examine the other trees around it. Are there trees close by that are at approximately the same crown level? These intermediate and codominant trees are competition for your crop trees, but they’re also providing a competitive atmosphere that keeps your chosen teller growing upward.

However, too much competition can be detrimental to tree health. As a general rule, if neighboring trees are touching the crown of your crop tree, cut them down! Retention of surrounding trees is fine as long as enough light is present to allow coppicing in the understory.

One of the advantages of converting an abandoned woodlot to a coppice with standards is that a lack of management has likely encouraged upward over outward growth. If you’re lucky, you may discover that you have young standards or aspiring tellers that are ready to be released.

The process of releasing a tree from surrounding competition should be gradual; trees suddenly exposed to intense light may exhibit shock in the form of epicormic branching (dormant buds that sprout in random and often undesirable locations, such as the lower trunk) or leaf scorch. To avoid shocking your trees, consider removing competition over the course of one or two years.

Other important considerations in cultivating healthy standards include maintaining soil quality and preventing basal injuries.

In healthy forest soils, approximately half of the soil volume is air and water space. These physical qualities ensure adequate infiltration and percolation of nutrients and allow roots to grow both vertically and laterally. Working in your woodlot poses a potential threat to soil quality through compaction. Minimize compaction from equipment (such as tractors and forecarts) by following best management practices (BMPs). BMPs include:

As discussed in chapter 1, injuries to the base of a tree are generally associated with either fire damage or logging operations. Basal injuries to coppice trees rarely represent a health issue, since the trees are usually harvested before decay becomes a problem. However, basal injuries on tellers and standards represent a more serious issue, since these trees are typically grown for 60 years or more. This long life span also means greater risk of fungal and bacterial infections entering through a basal scar. One way to avoid this kind of injury is to leave high stumps from the competing trees you cut down around your valuable standards. These surrounding stumps become “bumpers” that protect your standards when logs are skidded through the forest.

In time, your released tellers and thinned standards will respond to improved growing conditions by developing a healthy crown and regular seed crops, at least in theory. At some point you will likely experience mortality of some tellers and standards. One common threat to standards is windthrow. In an unthinned forest, tree canopies are in contact with one another, offering a community support network. When competition is reduced to allow your standard to thrive, not only does it lose the support of the surrounding trees, but it also feels the effects of wind that, under prior conditions, would have been blocked by neighboring trees.

Once a tree is uprooted by windthrow, you have a limited number of options. In most cases, the practical solution is to harvest the tree for lumber, firewood, or some other homestead use. In some cases, the roots of windthrown trees may remain intact, creating a horizontal trunk capable of producing numerous epicormic branches that can be used for any of the small-diameter coppice applications described in this book. An additional use for these windthrown standards is to use them as mushroom cultivation sites (this technique is described in chapter 7).

Collectively, your woodlot objectives and the successional stage of your woods will determine your options for creating wildlife habitat. Birds and mammals are the two main types of fauna you will be concerned with.

Generally, birds are considered an asset in coppice-with-standard systems. Among the most notable benefits of birds is their role as seed dispersers. Using wildlife to disperse seeds is a natural regeneration method that saves the time and labor associated with planting by hand. As birds consume fruits, the seed coats experience abrasion that aids in germination. One way to encourage seed dispersal by birds is to retain both snags and living trees in semi-cleared areas. These trees serve as roosts that increase the probability of seed dispersal and can accelerate natural forest succession.

Larger birds, such as wild turkeys, appear to play an important role in promoting the establishment of seed-borne trees, which may become standards in future woodlot rotations. As turkeys scratch at the forest floor looking for insects, fungi, and worms, they inadvertently create an important microenvironment for germination. The scratching action mixes organic material with mineral soil, which is necessary for many seeds to germinate.

Contrary to popular belief, woodpeckers do not generally attack healthy trees. Because they’re actually in search of beetles, termites, and ants, they’re most likely to peck at dying trees. Knowing this, you may wish to provide habitat to local woodpeckers if attracting them is one of your woodlot goals.

One simple method is to girdle a large but poorly formed tree in your woodlot. Girdling is done by chopping or cutting through the cambium of your targeted tree with an axe or chainsaw. If you opt to girdle with a chainsaw, use a series of three circumferential cuts approximately one inch apart, since the kerf of a chainsaw cut is narrower than that of an axe. Most trees will try to respond to this injury; therefore, make sure you remove a thick kerf of cambium so that the tree cannot heal. Cutting off the transport of nutrients eventually kills the tree and allows beetles, termites, and ants to move in. In an act of efficiency, woodpeckers will excavate cavities as they search for food. These cavities will be large enough to allow the establishment of nests.

Be careful, however, not to confuse the common red-headed woodpecker with its cousin, the sapsucker. Despite their name, sapsuckers do not actually suck sap; instead they bore a shallow hole in the tree that allows sap to flow to the surface, thereby attracting insects. Sapsuckers commonly establish forest routes where they move from tree to tree, boring small holes, and then return along the same route to pick off insects.

One way to differentiate sapsucker damage from beetle or insect damage is that sapsuckers will bore their 1⁄4-inch to 3⁄8-inch holes in straight, parallel rows, not randomly. Because sapsuckers go after live trees, you may wish to protect your trees, particularly if you have desirable standards or future crop trees. While chemical repellants exist, wrapping burlap around the attack zone seems to be an effective deterrent.

It’s also worth noting that different successional stages of your coppiced woodlot will attract different bird species. In a study that examined the abundance of breeding migratory birds in an English mixed coppice woodland, it was determined that white-throated sparrows were most abundant one to three years after coppicing, but other species, such as the blackcap chickadee, were most abundant six to eight years after the coppice harvest.

Game birds such as partridge, grouse, and woodcock thrive in the early successional forest created through coppicing. After two years of growth, coppice sprouts offer enough protection that these birds often seek coppice stools as camouflaged protection sites. Occasionally, game birds will use coppice stools as nesting sites; because of this, coppice shoots should not be harvested during spring.

Girdling can provide habitat for woodpeckers and cavity nesters while creating growing space for neighboring trees.

Not surprisingly, small mammals are greatly influenced by the coppicing cycle. Generally, the size of the animals is proportional to the successional stage; first to move in are mice, chipmunks, and squirrels, followed by rabbits and deer. While game species may be an attractive woodlot addition for hunters, the damage caused by these animals can be significant. The dense growth created in coppice systems provides protection, which discourages migration. The combination of protective habitat and an ample supply of young, succulent shoots can lead to significant damage to your woodlot.

Beyond hunting or trapping, one of the most effective means of discouraging browsing is by entering your coppice woodlot as frequently as possible. The presence of humans, hunter or not, still remains one of the greatest deterrents to animals. If excessive browse continues to affect regeneration in your woodlot, you can opt for either a physical barrier, such as a tree-saver tube or netting that covers young growth, or a spray repellent that reduces palatability.

Another use for coppice systems is to grow fodder for livestock. In this section, “fodder” primarily refers to buds, early shoots, fruits, leaves, and young branches, which are both abundant in the woodlot and of nutritional value.

Choosing livestock to match your fodder options is an important aspect of developing a homestead that requires minimal external inputs. In the case of my high-elevation, high-latitude homestead, I’ve selected breeds that are not simply grazers but also browsers. Fodder can be either collected or browsed.

Collecting fodder can be done more efficiently if it is combined with other woodland goals. For example, thinning red maple coppice stools makes for a tasty treat for my highland cattle and utilizes sprouts that ordinarily would be cut and left to decompose in the woodlot.

Craig Milewski is a fish and wildlife professor, voluntary simplifier, hunter, backyard lumberjack, and bow maker. Craig grew up in rural North Dakota and spent his early years with farmers, foresters, and fishermen. This lot of outdoorsmen gave Craig an early appreciation for rural skills and nature’s bounty.

Belying his modest demeanor are Craig’s accomplishments as a primitive hunter. Craig doesn’t hunt with guns or even compound bows. Instead, he prefers to use his woodlot as his woodshop for crafting handmade bows, with the goal of returning to that same woodlot for a hunt. For Craig, this nested relationship begins by combing his woods for clear, straight ash trees.

The trees need to be only about 4 inches in diameter, meaning that in many cases Craig is able to use coppiced stems. When selecting a tree, he looks for a straight section without knots or twisted grain. Once he’s located a suitable tree, Craig uses his bow saw to cut out a 5-foot-long section, then uses a froe to split the log into a 2-inch-thick stave.

“Even the straightest of trees have a natural curve to the grain.”

Even the straightest of trees have a natural curve to the grain. By holding the stave upright and resting the bottom on his foot, Craig gently pushes on the center of the stave. As he pushes, the stave rotates to reveal the natural curve of the bow. From this point forward, Craig primarily removes wood on the “inside” of the bow. Removing wood on the “outside” would compromise the structural integrity. The two primary tools he uses to remove the wood are a drawshave and a farrier’s rasp. The drawshave is fast but poses the risk of run-off, where the blade cuts too sharply into the grain, compromising the overall strength.

Next, Craig marks out the handle and begins to bend the bow, noting areas of unequal thickness, which result in unequal tension. To make sure both ends of the bow bend equally, Craig makes long passes with a drawshave to even out the thickness, a process known as tillering. Once Craig is satisfied with the overall shape of the bow, he uses a round rat-tail file to carve the nocks, the grooves in which the bowstring rests at each end. The string is made from sinew, or stretched tendons from a previous year’s deer hunt. Craig uses linseed oil as a preservative on the bow. The final step, of course, will be returning to the woodlot to harvest a deer, hopefully just a few yards away from where the bow originated as a coppice sprout.

Another technique that makes for efficient small-scale fodder collection is shredding (also known as “snedding”). Shredding is the removal of side branches on a tree. This process is usually carried out in late summer, when the leaves contain their highest nutrient levels. The shredded branches can then be fed directly to livestock (most commonly goats and cattle) or saved and piled as a winter fodder source. Oaks are commonly used as shredding material because of their leaf retention and high nutrient content.

Traditionally, shredding was done to the entire stem of sapling and pole-size trees. This dramatic physiological change shocks the tree into releasing dormant buds capable of growing into new branches over a single season. One variation of this method would simply be less-aggressive pruning, intended to create clear wood or improve the form of a crop tree. It is important that any potential forage be researched to determine if it has toxic qualities. Black cherry, for example, contains a compound known as prussic acid, which can be harmful to livestock.

Pollarding is similar to establishing a coppice stool, only higher, so that the new growth is safe from grazers. When a tree has been pollarded over multiple generations, it will develop bare, scaffold limbs, with “knobs” at the end of each branch. These knobs are what produce abundant new, leafy growth. As with shredding, the goal is to produce tender sprouts and leaves suitable for animal fodder. The term “pollard hay” refers to the young growth, which is traditionally cut at two- to six-year intervals and either fed to livestock green or stacked in silage mounds for winter feeding.

Unfortunately, pollarding is often done carelessly with a machete or billhook (see here), resulting in unnecessary damage. By taking your time and following a few basic steps, you’ll preserve the health of the tree and be able to produce an abundant crop. Perhaps the most important precaution is to make sure the sprouts are removed at the base of the knob, which makes it easier for the tree to heal the wound. It’s also important to start the pollarding process when the tree is young so that you don’t have to cut limbs larger than 1 inch in diameter.

Over time, the knobs will develop, creating more dormant buds capable of producing large amounts of pollard hay. Finally, make sure that you select trees for pollarding that are vigorous and take well to pollarding; sycamores, beeches, oaks, and chestnuts are all good candidates.

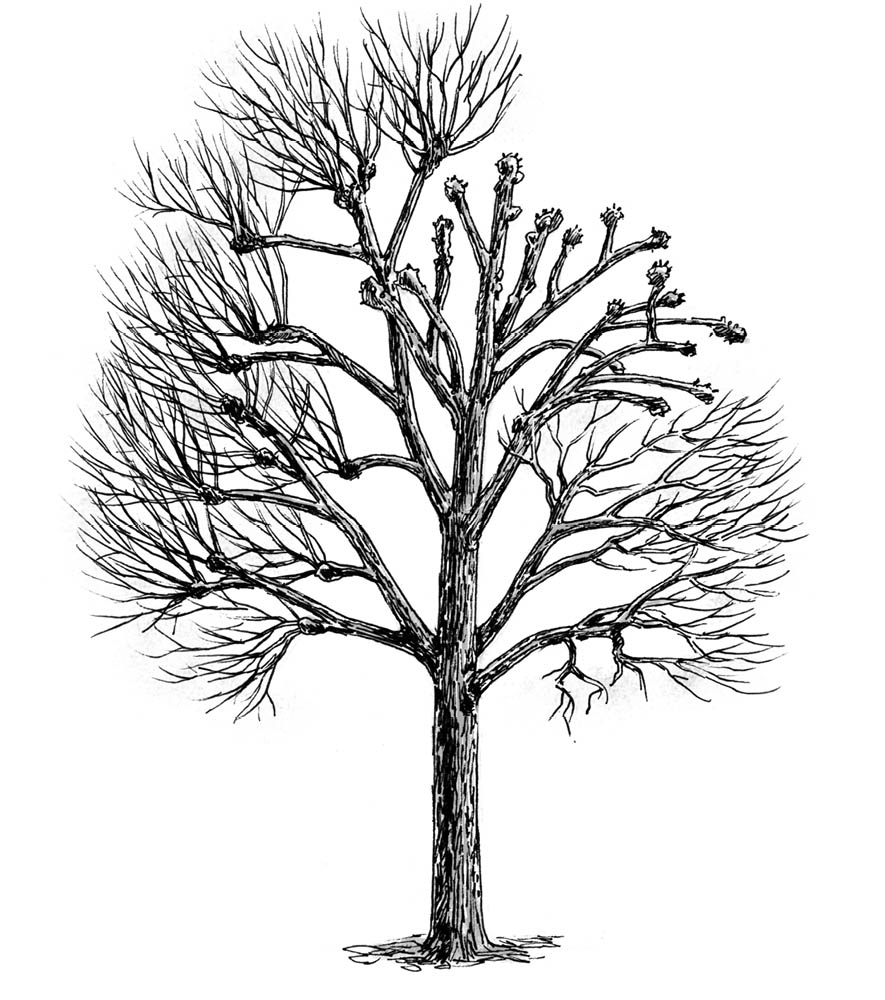

This tree illustrates the various developmental stages seen with pollarding. The lower right portion shows the crown prior to pollarding, and the upper right portion is after several subsequent pollarding treatments. The left side of the crown shows previously pollarded branches with new growth.

Rather than collecting the fodder yourself, allowing animals to browse offers the temping advantage of letting your livestock do the work. That temptation comes with a cautionary tale. You have to consider two factors — animal species and browsing duration — and integrate both as part of your grazing plan. The one exception, of course, would be if your goal is to eliminate vegetation in a specific grazing area. Assuming your goal is not to eliminate all vegetation from an area, then short, light browsing is best. Depending on the type of livestock and the size of your browsing area, this may be just a few hours or perhaps as long as a couple of days.

Young green leaflets that emerge in early spring are a treat to livestock that have overwintered on hay.

You will also find that different tree species have different levels of palatability. If you’re trying to get your animals to consume a species they’re less than fond of, you may need to move to a collection system in which the browse is mixed with more palatable feed. Over time, you’ll be able to increase the ratio of browsing material until the animals develop a palate for browsing a specific type of fodder. I successfully transitioned my cattle and sheep to a feed mixture of 75 percent hay, 25 percent conifer browse by combining the two. I’m now able to toss a wagonload of conifer boughs over the fence and create an instant feeding frenzy. Before I introduced this fodder in their hay ration, they wouldn’t touch it.

The way that animals browse will dictate whether you collect forage or allow browsing. My Highland cattle, for example, will consume woody stems up to 3⁄8 inch in diameter. On the other hand, my blackface sheep are much more delicate, carefully removing the leaves without damaging the stem. This delicate browsing is, essentially, natural shredding.

Some livestock breeds simply won’t browse, no matter how hard you try. The selection of livestock breeds on my homestead was highly intentional; it involved selecting the breeds and individuals from within herds best suited for a combination of grazing and browsing. In my case, this has meant raising Scottish Highland cattle, Scottish Blackface sheep, Mulefoot hogs, and Bourbon Red turkeys. Your specific location and available browse will inform which breeds are best suited for your homestead.

Finally, it’s important to note that browsing alone is not entirely sufficient for any livestock. On more than one occasion, I’ve heard livestock folks overpromise the virtues of browsing, leading one to believe that livestock could live on sticks alone. Instead, I would encourage you to view browsing as a symbiotic function that your livestock can play a role in: controlling vegetation while benefiting from nutrient-dense supplemental fodder. For more information on creating silvopastures, including browsing and grazing techniques, see chapter 3.

While European cave paintings drawn with charcoal indicate that charcoal dates back at least 30,000 years, it is not known whether the cave painters intentionally produced charcoal as a fuel source or simply found it as a by-product of wood fires. However, we do know that 4,000 years ago, charcoal became an essential and deliberate part of the economy, because it was used to smelt tin and copper to make bronze. The shift from smelting copper to making bronze required temperatures almost 572°F (300°C) hotter, but led to the development of essential tools such as the more durable bronze axe, which was used in both war and woodlot. These higher bronze-forging temperatures could be achieved only through the use of energy-dense charcoal.

By 1000 BCE, Europe had cleared much of its land for agriculture, using wood by-products for charcoal production. However, as the wood supply dwindled, the need for charcoal in bronze production, and eventually iron, led to the creation of coppice woodlots, specifically designed to yield high-quality charcoal. This is considered by many to be the most influential fuel in history.

Although virtually any wood species can be used to make charcoal, the most common species in coppice arrangements are alder, oak, and maple. (Hickory makes famously great charcoal but doesn’t coppice very well.) For most people, charcoal is a by-product of other forest activities, and the wood that is used to fire your charcoal oven should be your “worst” firewood or, better yet, scraps left from other projects.

Charcoal can be used for a number of other applications besides barbeque. Both commercial and more primitive water filtration systems rely on the same basic charcoal-based technology to remove sediments, volatile organic compounds, and odors from water. One common method for remote off-grid homesteads employs a gravity-fed charcoal filtration system in which water percolates through a filter filled with ground charcoal, much like a drip coffeemaker.

Using the same process as the lump charcoal procedure described above, you can create charcoal pencils from the twigs, seedlings, and saplings removed as part of your regular tending operations. Load the pencils vertically in a 1-gallon paint can, fitting about 200 pencils per can.

The charcoal-cooking process results in usable by-products as well, beginning with the char-ash left at the bottom of the crucible. This ash can be used as a soil amendment to make acid soils more alkaline. If you choose to make charcoal out of softwood, the result will be a less energy-dense coal; however, you’ll find the bottom of your crucible lined with a thick tar, roughly the consistency of caulking. This cement has historically been used for a variety of adhesive needs but is useful on the modern homestead as a patching material that sticks to virtually anything, including wood, metal, and cloth.

Charcoal is nearly pure carbon. “Cooking” wood in a low-oxygen environment releases water, hydrogen, methane, and even tar (in the case of softwoods). What’s left after the cooking process are lumps of coal that weigh about 25 percent as much as the original material that was placed in the crucible but are more energy-dense than the original “raw” wood.

Making charcoal from coppiced firewood can be done in an afternoon with easily salvaged materials. The quality of the charcoal produced is superior to store-bought briquettes that are made of compressed sawdust and burn quickly.

I hope by this point you’re starting to see your forest less like a specialty store and more like a well-stocked general store. As you work in your woodlot, note the possibilities not only for fauna, fodder, and fuel but also for furniture. Admittedly, seeing this future furniture will require a bit of imagination.

I’ll use my own homestead as an example. Since a good portion of my woodlot was an abandoned Christmas tree farm, the two primary species were white pine and balsam fir, with small patches of red maple and gray birch. Unfortunately, much of the white pine had been infected by the white pine weevil, a parasitic beetle that deforms the tree by killing the terminal leader at the top. (Multistemmed tops are common in many tree species following damage to the terminal leader; mine just happened to be pine.) The tree responds to the death of this leader by allowing the branches in the whorl below to compete for the role of new dominant leader. These competing whorl mates form a bushy tree that has limited value as timber. Since I wanted to encourage species such as red maple and gray birch that are able to coppice sprout, I removed the weeviled pines and converted the inverted tops to stools, chairs, and table bases.

Treat your woodland homestead like a home improvement store; look for burls for bowl making, curved branches for door pulls, and multileader treetops that can be inverted to make table bases and stools.

You could also employ your coppicing knowledge to grow multilegged stools and tables by coppicing taller stumps and selecting the three or four leaders that look most promising as stool or table legs. Obviously, this process takes much longer (20 years or more) than simply selecting a tree from your woodlot that has already developed this utilitarian form, but it is worth mentioning for those interested in managing for a unique, long-term coppice crop.

If you’re looking for more instant gratification, consider coppicing willow for bentwood furniture. Small-diameter willow can be coppiced on an annual or biennial basis. It can also be harvested as a by-product when thinning the sprouts on a coppice stool that’s being grown as a longer-rotation crop.

Coppicing willow allows you to sustainably harvest wood to make your own rustic furniture, such as this bench, in as little as two years.