Significant Times

for Magick

F olk magick practitioners, who studied the cause and effect of energetic workings for generations, discovered that particular hours and days were best for performing certain esoteric rites. These times include the phases of the moon, various astronomical events, and solar occasions. Additionally, our forebearers celebrated important life events and used them as an opportunity for blessing loved ones.

Some readers might be wondering about the reason for discussing these traditions, and whether these customs have any relevance in the present day. For the ancestors, each magickal act had a purpose, such as calling for good health and prosperity during a particular moon phase or holding a feast on a sacred day. Helpful beings were summoned and negative influences were banished. This is still necessary in current times. Of course, we also dance, create art, and celebrate holidays because it’s fun. These observances can create a bond between humankind and deities, ancestors, or nature. The rituals can also assist in building a community.

Yet common magick practitioners have another good reason for holiday gatherings: enacting rites for the purpose of priordination. Celebrating during certain times is a way to “pay it forward” using magickal power. Every dance performed, each artistic object that is created, the satisfaction of a delightful feast, and the laughter and joy of an audience watching a folkplay recharge the energetic battery and refill the magickal pool. These forces can be drawn upon later in times of need or difficulty. The reserves of energy sustain each individual and create a support network amongst a family, tribe, ethnic group, or people with a common purpose.

We might not be able to climb a mountain on Lughnassadh or cut fresh greenery in the woodlands on Beltane. However, many rites and workings can be replicated with whatever is available or by using facsimiles. This utilizes the principles of sympathetic magick. Visiting a farmer’s market and buying gourds and squash for Hallowe’en is as legitimate of a celebration as selecting the perfect jack-o’-lantern from the pumpkin patch. Bonfires can be replaced with candles. Blossoms from the florist or sprigs of holly from a greenhouse can replace the May basket or Yuletide greenery. Taking a hike on a nature trail on Beltane replicates a woodland jaunt. Groups can gather to enjoy the spirit of the rite, thinking about the past and ancestral customs as well as reveling in the moment together.

Solitaries can read about group ceremonies in books or watch videos online. A celebrant might create a harvest feast for one or share their bounty at a shelter or care facility. Those with an artistic flair can draw symbolic pictures or create an item that represents the holiday. Solitary magick users can create beautiful rituals for one person and connect to deities and nature. Local, regional, and national events for Pagans can replicate age-old traditions during the holidays, and sometimes, unique celebrations are invented and new friends are made.

Liminality

When we enact rituals during special times, such as a solar holiday or particular moon phase, it causes the magick to be especially potent. A liminal period is an ending of one era or phase and the beginning of another, and thus carries the significance of both time periods. An example is twilight, when daytime is ended but night has not completely begun. Liminal times combined with places that are between two locations might have a dual or triplicate nature, taking on the qualities or characteristics of both, all, or neither of the circumstances. Liminal periods have their own particular fluid energy. Folkloric practitioners call liminality betwixt and between, thresholds, straddling the hedge, the borderland, an edge, or a cusp. A metaphor of traditional witchcraft is “jumping the stile,” a stone boundary wall, which connotes a demarcation that ends one situation and begins another.

The esoteric significance of liminal times and events is ambiguity. These natural states are seen as being in fluctuation. Liminal periods are optimal for performing magick because they have fewer limitations and restrictions between what is and what could be. When a rite is undertaken at these borderline times and places, it uses the powers of each feature and of all qualities, which amplifies the forces exponentially. For example, if a ceremony is enacted on Hallowe’en, it takes advantage of the end of high season of summer and beginning of winter as well as the end of the harvest and the beginning of a fallow period, when days are becoming shorter and nights becoming longer. This creates an incredibly powerful experience.

Quarters and Cross-Quarters

The “big eight” holidays celebrated by modern neo-Pagans were often called quarter days, also known as cross-quarters in England and Scotland in the past. These dates align with agricultural holidays as well as Catholic saint’s days.38 In old Welsh, a cross-quarter was sometimes called a Ysbrednos, or a spirit night, due to a belief that energetic beings were more active at these times. Quarter days mark the borders between seasons, while cross-quarters or spirit nights have profound magickal energies because the boundaries between endings and beginnings are blurred. These holidays, as well as the phases of the moon, are optimal times to perform rites and workings, to reconnect with the cycle of the seasons, and to celebrate life.

I have been asked if it is crucial to celebrate a holiday on the actual date of an equinox or solstice, or if it is essential to perform a rite at the exact moment the moon enters a different phase. While it is not absolutely necessary to use the precise hour and planetary sign to execute a magickal rite or to enact a ritual on the date of a holiday, it surely can help. Timing can influence a working. Specific dates and times, such as the sun being situated in a particular constellation or the moon in its waxing phase, can increase or decrease certain forces or encourage certain conditions.

Days are named for deities and thus may carry the aspects of that god-form. For example, Tuesday was named for the Norse god Tyr, who was known for strength and prowess as a warrior. He is associated with the Roman god Mars and the Welsh war god Nuada, and thus Tuesday may carry those martial qualities. Rites performed on this day will have an added potency.

It is easier to do abundance magick during a period associated with harvest, to initiate a project in the spring, and to perform a banishing rite during the winter or the dark of the moon. Anything that decreases resistance, overcomes inertia, and optimizes probability is beneficial in magick.

Magickal energies are strongest when it’s closest to the actual time of the height of power, or zenith. Doing a ritual after the designated day is more effective than performing a rite beforehand. The day after the vernal equinox contains new springtime energies, while the day before the equinox still carries the old, tired winter energies. Because we must work, attend school, and/or care for our kinfolk, we sometimes must wait to celebrate a holiday until the weekend. When the summer solstice falls on a Tuesday, it’s better to hold your celebration on the following Saturday rather than the preceding weekend. The energy zenith might occur at 2:00 a.m. on Tuesday, June 21, but the time leading up to that hour contains the waning energy of the previous season. The same holds true for moon phases; observing the day after the moon turns full takes advantage of the full lunar energies.

Almanacs can help when determining the exact hour of a planetary occurrence and the location of the moon and sun in the zodiac. This also has an influence on magickal powers. Some signs of the zodiac are viewed as more fertile. For example, Taurus and Cancer are seen as more fruitful than Gemini and Leo. (No, the zodiac did not originate in the British Isles. However, common magick users still find it helpful.)

It is possible to set up a spell or rite beforehand, leave it to “charge” or gain power, then resume the ceremony afterward. A person who works nights can set a crystal on a western windowsill to absorb energy under the light of the setting full moon, perform a brief ritual, leave to complete their shift, and return to find the crystal full of moonlit power. Common magick, by its very nature, can be flexible. Adaptations may cause the loss of a portion of energy … but a little power is better than none. However, there are some events that will not happen twice in our lifetime, like a full solar eclipse during Lammas or an alignment of all the planets with Earth. If we miss these once-in-a-lifetime events, well, it’s over.

Not every nature spirituality tradition goes by the calendar, as our ancestors surely didn’t. Instead, they used intuition about optimal times for magick or calculated time by a particular natural event to mark the seasons. This was done in place of observing days based on positions of the sun. Folk magick users might consider the first frost to mark the first day of autumn and spring’s onset as the day a certain flower blooms. Others mark the seasons on the first full moon after the solstice or equinox. Still others go by the time that the sun enters a particular constellation. And some common magick workers still go by the old Julian calendar, celebrating the solar holidays from seven to eleven days after their current calendar dates. In that case, Hallowe’en is observed on or around November 7.

The Moon

Sailors are aware that the tides of the ocean and large lakes are affected by the gravitational pull of the moon. Lunar transitions also influence certain types of rites. The point when the moon “turns,” the minute and hour when the lunar phase changes from waxing to full to waning, are considered liminal times. Common magick practitioners use the moon phases as an influence for our spells and divination. Each moon phase lasts for approximately a week.

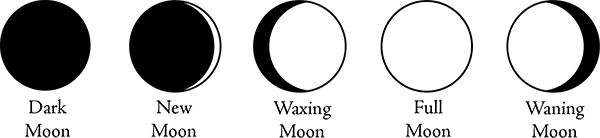

Here is how to recognize the moon phases and when they are visible in the Northern Hemisphere:

Dark of the moon. Probably not visible in the sky. Rises and sets with the sun, or rises at dawn and sets at sunset. A very brief period before the new moon. Time for banishing.

New moon. Resembles a thin crescent or U shape. Rises and sets with the sun. Time to initiate new projects.

Waxing moon. Also known as first quarter. Resembles a D. Rises at noon and sets at midnight. Time for working on projects.

Full moon. Rises at sunset, sets at dawn. Time for asking for boons, celebrating, performing magickal rites, and the culmination of endeavors.

Waning moon. Also known as third quarter. Resembles a C. Rises at midnight and sets at noon. Time for banishing or removing undesirable conditions.

Dark of the Moon

The dark of the moon occurs for only a short time, between one-and-a-half to three days. This is the last visible crescent of the waning moon or a time when the moon is not visible in the sky at all. The dark of the moon, or the phase just prior to the new moon, is the best time to end something that no longer serves us, such as a relationship, or to permanently banish a condition. The color associated with the dark of the moon is black.

New Moon

The new moon is a time of beginnings, optimal for initiating new projects and starting new relationships. Magickally, it is time to do rites to ensure a project will be successful or to optimize changes. The color of the new moon is silver or pale blue.

Waxing Moon

Waxing moons are perfect for continuing projects that have already been initiated. Almanacs suggest planting above-ground crops during the waxing moon, during periods when the moon is in a fertile zodiac sign, or aligning with constellations representing watery, fruitful energies, such as Cancer. Magickally, it is a good time to do rituals for increase in material things, to bring about positivity in personal relationships, and to count blessings and thank deities. The associated color of the waxing moon is white.

Full Moon

A large body of folklore is devoted to occurrences at full moons. Madness used to be called “lunacy,” and the werewolves of folktales transmogrify during the bright moon. The behavior of animals and plants seems to be affected by a full moon. In modern times, the full moon is considered a time of fruition and completion. Full moons are equated with mother goddesses and pregnancy.

Some believe that magickal workings are best performed when the moon is full and that participants should ask for a boon from the gods at these occasions. Other practitioners believe the full moon should be reserved exclusively for celebrations or used to give thanks. Full moons are great for rites that involve the revealing of secrets, cleansing magickal tools, and charging talismans and amulets. They are also a good time for working on projects. Divination seems to be especially accurate when done beneath a full moon. Magickal tools can be charged in the moonlight, absorbing the lunar energies. Many shamanic practitioners host full moon drumming circles. Folk magick users set cups of water out at moonrise to capture the essence of the moon, taking the cup indoors before dawn. The water can be later used in spell work. Colors associated with the full moon are silver, pale blue, and bright white. The full moon is also associated with pink in spring and yellow in autumn.

The planting moon is a bright full moon in springtime, while the harvest moon and hunter’s moon are when the moon is full and bright during autumn months, making it easier for farmers and hunters to see and to complete their tasks after sundown. Seeing the full moon through the leaves of an oak tree means good luck. People can wish on the full moon, asking that the same moon that shines on them also shine benevolently onto their loved ones.

At the full moon in springtime and during the harvest, young ladies work this divinatory incantation: “Luna, every woman’s friend, now to me your good descend. Let me in this night visions see, emblems of my destiny.” The young woman would then fall asleep and dream images that foretold the following conditions. Flowers could mean trouble or a job; a ring meant marriage; a storm meant getting the bad things out of the way and having a good future; bread equated plentitude while cake meant prosperity; a shovel meant death; diamonds, jewelry, or money signified wealth; a flock of birds symbolized having many children; geese meant marrying more than once; a willow tree represented treachery; and keys meant property and power.

Full Moon Names

Nature spirituality traditionalists of both British and Native American cultures had names for each full moon that designated specific times or events that usually occur during that month. These are:

January: moon after Yule, cold moon, snow moon, old moon, ice moon

February: wolf moon, cold moon, hunger moon, storm moon

March: worm moon, egg moon, sap moon, chaste moon, moon of sprouting grass, plowing moon, hare moon

April: Lenten moon, pink moon, milk moon, hare moon, fish moon, paschal moon

May: flower moon, mead moon, rose moon, planting moon, merry moon

June: hay moon, lovers’ moon, strawberry moon

July: grain moon, buck moon, thunder moon, hay moon

August: fruit moon, grain moon, sturgeon moon, green corn moon, barley moon

September: corn moon, barley moon

October: hunter’s moon, blood moon, harvest moon

November: beaver moon, oak moon, fog moon

December: Yule moon, cold moon

Waning Moon

Banishing rites take place during the waning moon. The waning phase is good for “cleaning up” and for finishing projects. Almanacs suggest planting root crops during the waning moon as well as harvesting during dry or barren zodiac signs, such as Virgo or Gemini. The waning moon is a good time to cleanse the home and one’s magickal tools. Colors associated with the waning moon are white, blue, and gray.

More Moon Lore

• A gibbous moon is at more than a quarter, yet less than full.

• Blue moons are the second of two full moons that occur during one month or zodiac period, while black moons are the second new moon in one month.

• A black moon can also be a February with no full moon, which occurs roughly every three years.

• The second full or new moon in a month can add strength to rites of creation and banishment, possibly because of participants’ beliefs rather than any actual power of a moon phase.

• A super moon is a full moon that is close to the earth and appears very large in the sky.

• A red moon could mean a bloody year, either in terms of slaughtering many animals or a terrible war.

• Rain on the harvest moon is a bad omen.

• A bright full moon that is close to the earth foretells blessings.

• Witches and fairies were said to dance in the moonlight.

Lunar Deities

British Isles moon deities include the Roman Luna as well as Diana and her daughter Aradia; the Greek Hecate; the Greco-Roman Selene; the Welsh goddesses Arianrhod, Rhiannon, and Nimuë or Vivienne, who represent the waxing and full moons, and Cerridwen, who represents the waning moon; the Irish Áine, who is said to light up the night; and the Gaulish and Breton horse goddess Epona, said to ride at night. Those common magick users who work within Norse traditions honor the moon god, Máni, who may be the precursor of the folktales about the man in the moon.

Natural Liminal Times

Other liminal periods are related to the position of the sun, stars, and moon, relative to the earth. These include dawn, the time when the morning star first appears in the sky, the time when the evening star rises, dusk (also called twilight, the gloaming, shotsele, and owl light), sunset, and, of course, midnight. Midnight does not necessarily occur at 12:00 a.m.—it occurs at the exact midpoint between the sun slipping under the horizon and the first rays of dawn. True midnight can be calculated with the help of an almanac that shows the exact times of sunset and sunrise. Midnight is also called bull’s noon, the fairy hour, the small hour, dead of night, and the bewitching hour.

Nighttime is special for esoteric beings, who seem to be most active in the darkness. The Celts reckoned time by the setting of the sun, which was viewed as the start of a new day. Moonrise and moonset are liminal periods, as are a meteor shower, the appearance of a comet, and a display of the northern lights, also called aurora borealis or the merry dancers. Wishing upon the first star seen in the darkening sky is said to manifest our desires. All of these cosmic occasions are optimal for performing magick appropriate to the time, such as cleansing rites and the inception or completion of a project.

Solar and lunar eclipses also hold significance in nature spirituality. Often, the moon will turn red just prior to a total eclipse because of particles in the atmosphere. This is called a blood moon and can also be used for magickal rites. The change in energy during an eclipse can affect animals, humans, and the weather. Birds stop singing, nocturnal creatures emerge, and there are an abundance of natural portents and signs. Eclipses foretold an alteration of personal fortune or meant that an era was coming to an end. The magick of a lunar eclipse is an abrupt ending and beginning. In the old days, bad rulers could be deposed during an eclipse. An eclipse of the moon could be used to remove a baneful female ruler, while an eclipse of the sun could be used to banish an unjust king. A solar eclipse is a good time to make a sacrifice of something precious to us in order to completely end a condition that no longer serves us and to begin a new phase of life. Banishing rituals are quite effective during an eclipse.

Conjunctions are when heavenly bodies appear to line up in the sky. Two planets in conjunction mean that their powers are doubled or aligned. The conjunction of the sun, moon, and earth can lend the energies of all three heavenly bodies. The magickal significance of a conjunction depends on the symbolism corresponding to the planets; for example, Venus often represents love, while Jupiter symbolizes stability. Therefore, if Venus and Jupiter appear to align, it can augur stability in love or be an opportune time to do a working to bring about that condition. Venus and Mars together in the sky foretells harmony between the genders.

Omens such meteor showers and comets were used to foretell events. Comets were and are a strong omen related to drastic change. Halley’s Comet passing the earth in 1066 CE was said to have presaged the Norman Conquest. The Christian legend of the star in the east could have been this comet, which also passed the earth in 11 BCE. It also may have been a supernova or a conjunction of two or more bright stars or planets. The Perseid, Orionid, and Draconid meteor showers are used for wishing on falling stars.

The Stars

Liminal times can also be based on the positions of constellations and planets in relation to the earth and sun. Celtic people studied the science of astronomy,39 or the location of planets, stars, the sun, and the moon relative to the earth during particular times of the year. Pliny the Elder of Rome noted that the Druids used astronomy and other natural sciences.40 Qualifications for becoming an astronomer are outlined in Brehon Law.41 This shows us that our predecessors considered the positions of the planets to be useful. Many of the ancient stone megaliths located in Britain, including passage tombs and standing stones, have astronomical significance. Tomb doorways and the architectural design of various sacred sites align with the sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset during a certain event such as a solstice.

Common magick users sometimes formed a type of star chart out of a flat piece of metal, used to predict the onset of the seasons and times related to agriculture. Usually made of copper or tin, these “star plates” had holes punched in them to represent particular constellations. The practitioner would hold the metal plate up to measure against a natural feature, like a tree or rock formation, or a man-made structure, like a dolmen, at certain times of the year. When the stars of the constellation shined through the holes in the plate, the tribe would know that it was time to plant, harvest, or gather firewood for winter.

Speaking of astronomy, the Celts of Britain recognized some different groupings of stars than the constellations we’ve accepted today.42 Some of these celestial designs are based on Welsh myth and legend, especially the body of literature found in the Mabinogion and the King Arthur tales. The name Arthur is associated with bears, so the Great Bear and Little Bear constellations have that symbolism. These two formations are what we now call the Big and Little Dipper. Lyra, the constellation of the harp, was called Telyn Arthan, or Arthur’s Harp. The Milky Way was Caer Gwydion, named after the deity that represented communication and astronomy. The northern circle was named Caer Arianrhod for the goddess of the stars and beauty.

Life Events

Common magick practitioners recognize that life stages such as birth, coming of age, learning a profession, marriage, elderhood, and death also constitute liminal periods. One period of being comes to an end while another begins. This is all part of an endless cycle. Yet these events are also very personal for each individual and their loved ones. Rituals are performed to educate, prepare, and help the person adjust to the change, as well as to give well-wishes, aid, and comfort. Magickal rites can be enacted at these powerful times of change, which carry the “betwixt and between” energy of conclusion and initiation. Blessings and rites of protection are the most common. Suggestions for these appear in chapter ten.

The Celts used certain omens to forecast potential occurrences during a person’s life; for example, seeing a dog on one’s naming day might mean the individual would be loyal. Augury was often performed before the birth of a baby or during a rite of passage to predict how things might go for that person in the future. A person born during the “chime hours” from midnight until dawn was said to be able to view the spirit world.

Solar Holidays

Those who practice folkloric magico-religions celebrate holidays and do magickal workings related to solar events, which mark the four seasons. These dates are usually considered as the beginning of each season: winter around December 21, spring on or near March 21, summer circa June 21, and fall around September 21. However, it must be noted that Celtic people often reckoned the beginning of the summer high season as May Day and the beginning of the winter high season as Hallowe’en. While Wiccans call the quarter days, or onset of each season, the “Lower Holidays” or “Lesser Sabbats,” many common magick users recognize these days as the “big four” in magickal significance. The sun also enters different zodiac signs and constellations during these times, such as Libra around the autumnal equinox.

There are also sacred days that fall at the midpoint between these occasions. These are called cross-quarters, half-quarters, quarter days, or off-quarters. These include the days of April 30–May 1, August 1, October 31–November 1, and February 1 or 2. They are the center between the beginning and ending of each season, about six weeks after the season has turned. These days are considered liminal times and carry a special magickal significance.

Modern-day Pagans often celebrate these eight seasonal holidays, which they call Sabbats or the “Wheel of the Year.” In the Cymraeg language, they are called Ysbrednos, or spirit nights. In old Irish Gaelic, raitheanna, quarters and cross-quarters, are headed by raithe, the beginning day of each period. For common magick users, these days and nights are sacred. They are considered as liminal times optimal for performing certain rites related to weather patterns and to the agricultural cycle. Some of us believe the holiday starts at sundown the night before the quarter or cross-quarter.

The solar holidays are based on the position of the earth relative to the sun. The summer solstice is the longest day and shortest night of the year, and the winter solstice is the shortest day and longest night. Sol means sun, while stice refers to stillness and stasis; thus, solstice is when the sun was perceived to stand still. The vernal (or spring) equinox and the autumnal (or fall) equinox mark dates that are equally balanced between night and day, darkness and light. Equi refers to equality, while nox is a word for night; hence an equinox is an equally long night and day.

When Catholicism became widely practiced in Britain, many of the old-line Pagan solar holidays were syncretized with saint’s days, and customs were attributed to the particular saint. For instance, St. Michael’s Day in late September was celebrated with harvest feasts and agricultural games. Sometimes a new day was used for older activities, and some magico-religious traditions were moved to the new day. For example, many merry May Day festivities were transferred to Whitsunday, a Catholic observation.

Some of these days were not observed by certain British-based cultures at all. For example, harvests lasted for several weeks, with hard work all day and feasting and partying every weekend. Rather than recognizing Lammas and Mabon, the harvest season began when vegetables and grains were ripe and ended at Hallowe’en time, or when the crop was all picked. For most of my life, I never did anything for February 2, Imbolc, because not many Welsh folkloric practitioners celebrate this holiday. However, it’s a really big deal in the Irish traditions. I only began participating in Imbolc rites when I encountered neo-Pagans. Other days are majorly important to us, like the calendar new year and the opening day of hunting season.

The next chapter will go over some celebrations, rites, and workings for the solar holidays.

38. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “quarter days,” accessed April 2, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Quarter-Day.

39. A. Gaspani, Astronomy in the Celtic Culture, Osservatorio Astronomico di Brerea, accessed April 2, 2020, http://www.brera.mi.astro.it/~adriano.gaspani/celtcab.txt.

40. J. A. MacCulloch, The Religion of the Ancient Celts (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1911; Project Gutenberg, 2005), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/14672/14672-h/14672-h.htm.

41. Laurence Ginnell, The Brehon Laws: A Legal Handbook (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1894; Internet Archive, 2009), https://archive.org/details/brehonlawsalega00ginngoog/page/n5/mode/2up.

42. Bryn Jones, “Names of Astronomical Objects Connected with Wales,” A History of Astronomy in Wales, last modified March 3, 2009, http://www.jonesbryn.plus.com/wastronhist/namesobjects.html.